Submitted:

07 June 2023

Posted:

07 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Extraction

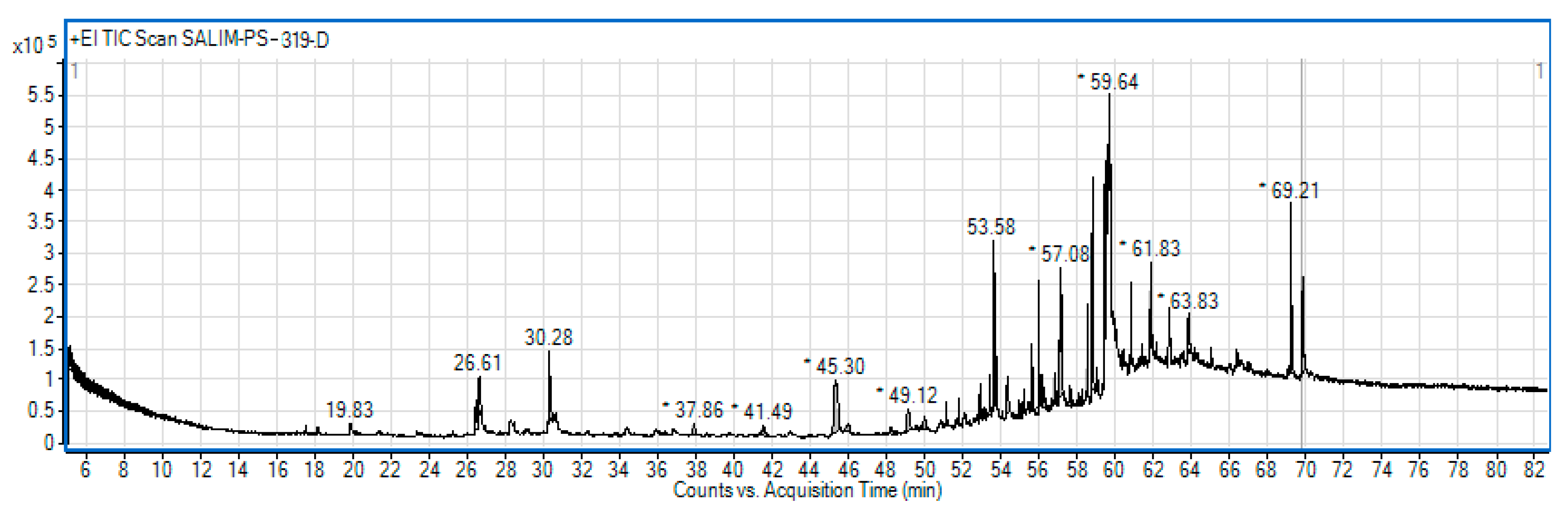

2.2. Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry(GC/MS) Analysis of CNEE

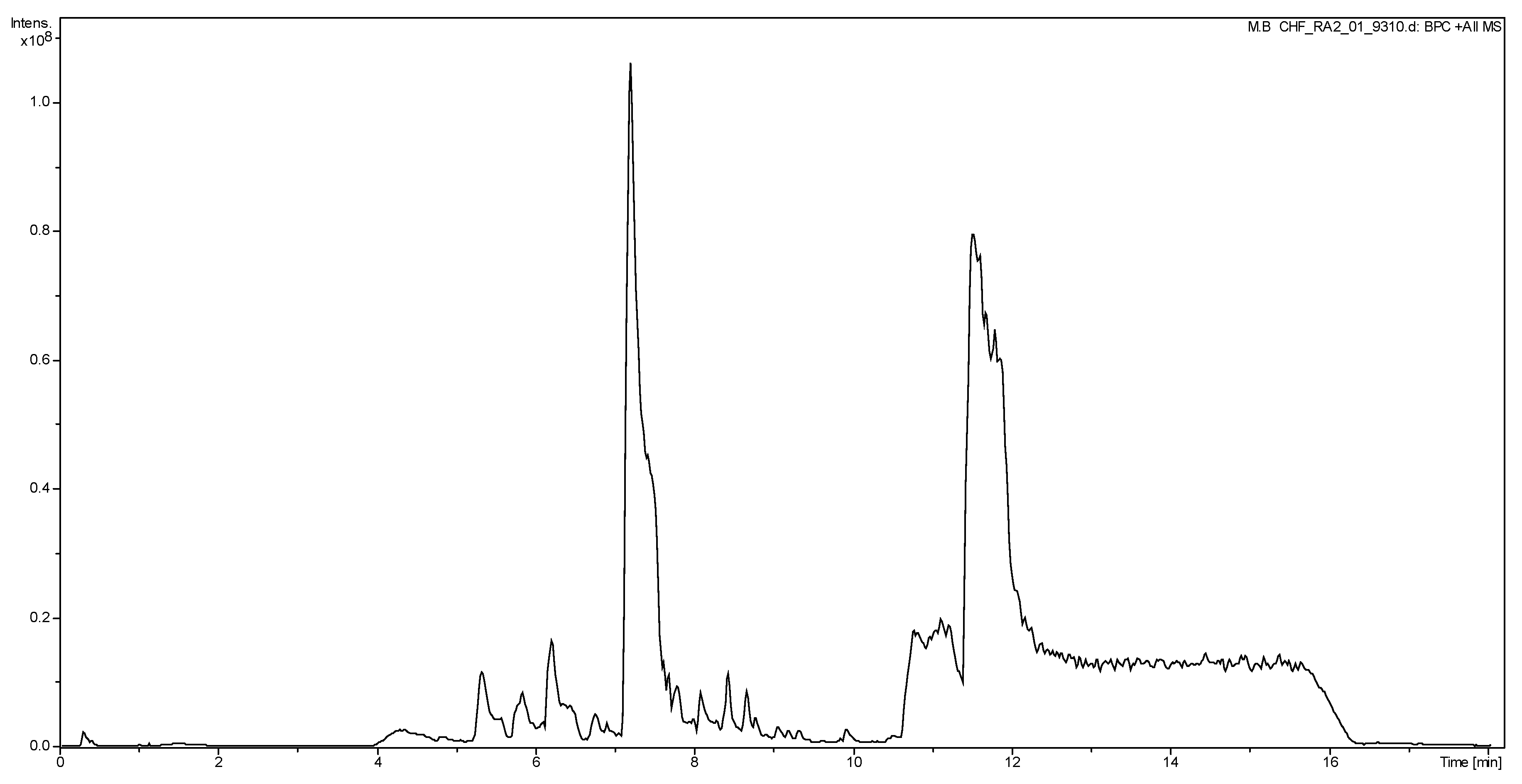

2.3. Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS) Analysis of CNEE

2.4. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles

2.5. Synthesis of Pectin Functionalized Silver Nanoparticles (Pectin-AgNPs)

2.6. Characterization of AgNPs and Pectin-AgNPs

2.7. Antibacterial Activity

2.7.1. Zones of Inhibitions (ZIs)

2.7.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentrations (MBCs)

2.7.3. Time Killing Kinetics

2.7.4. Bacterial Killing Mechanism

2.8. Hepatoprotective Activity

2.8.1. Animals

2.8.2. Clinical Examinations and Body Weight

2.8.3. Biochemical Analysis

2.8.4. Histopathological Examination

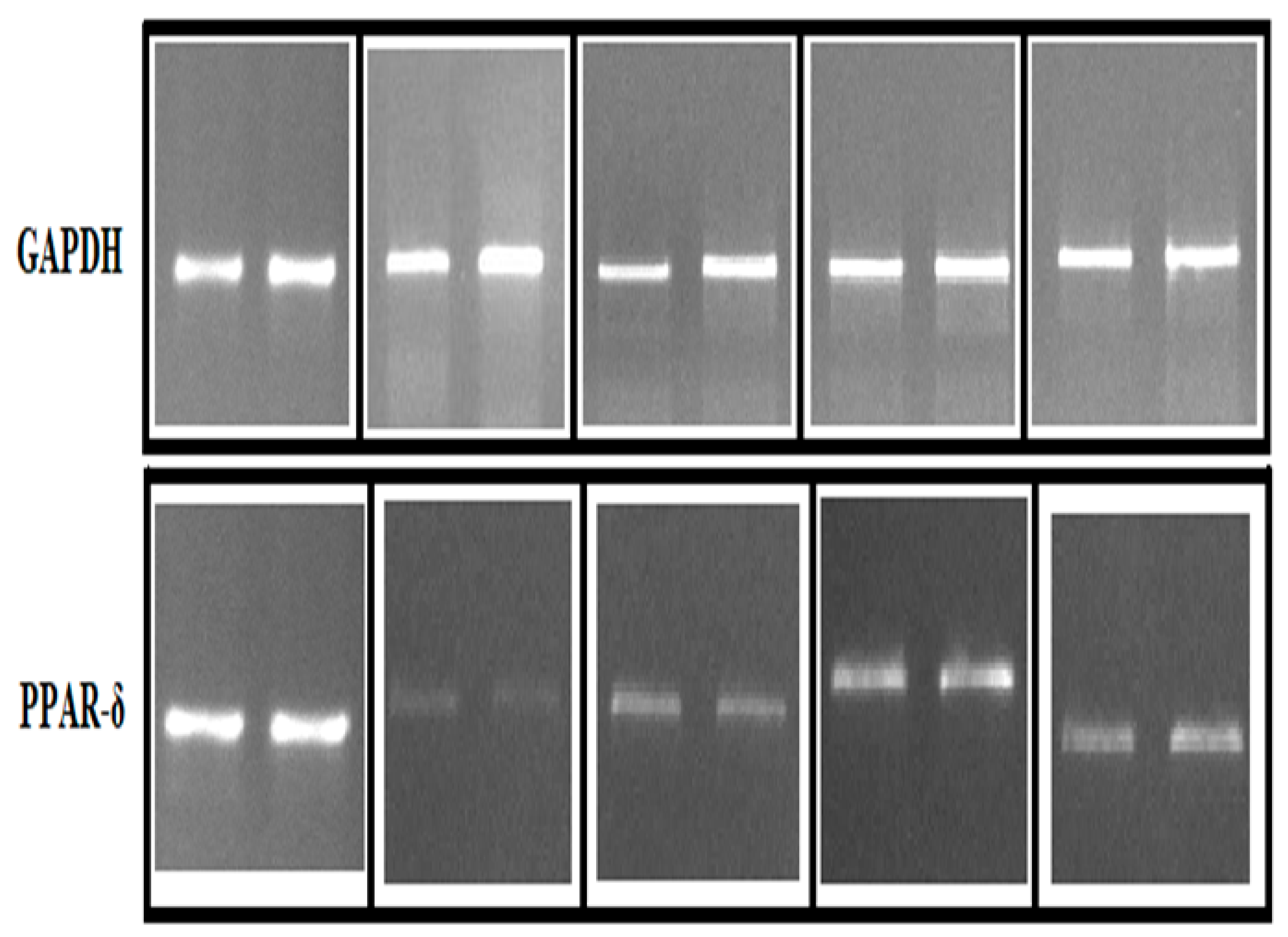

2.8.5. Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) Assay

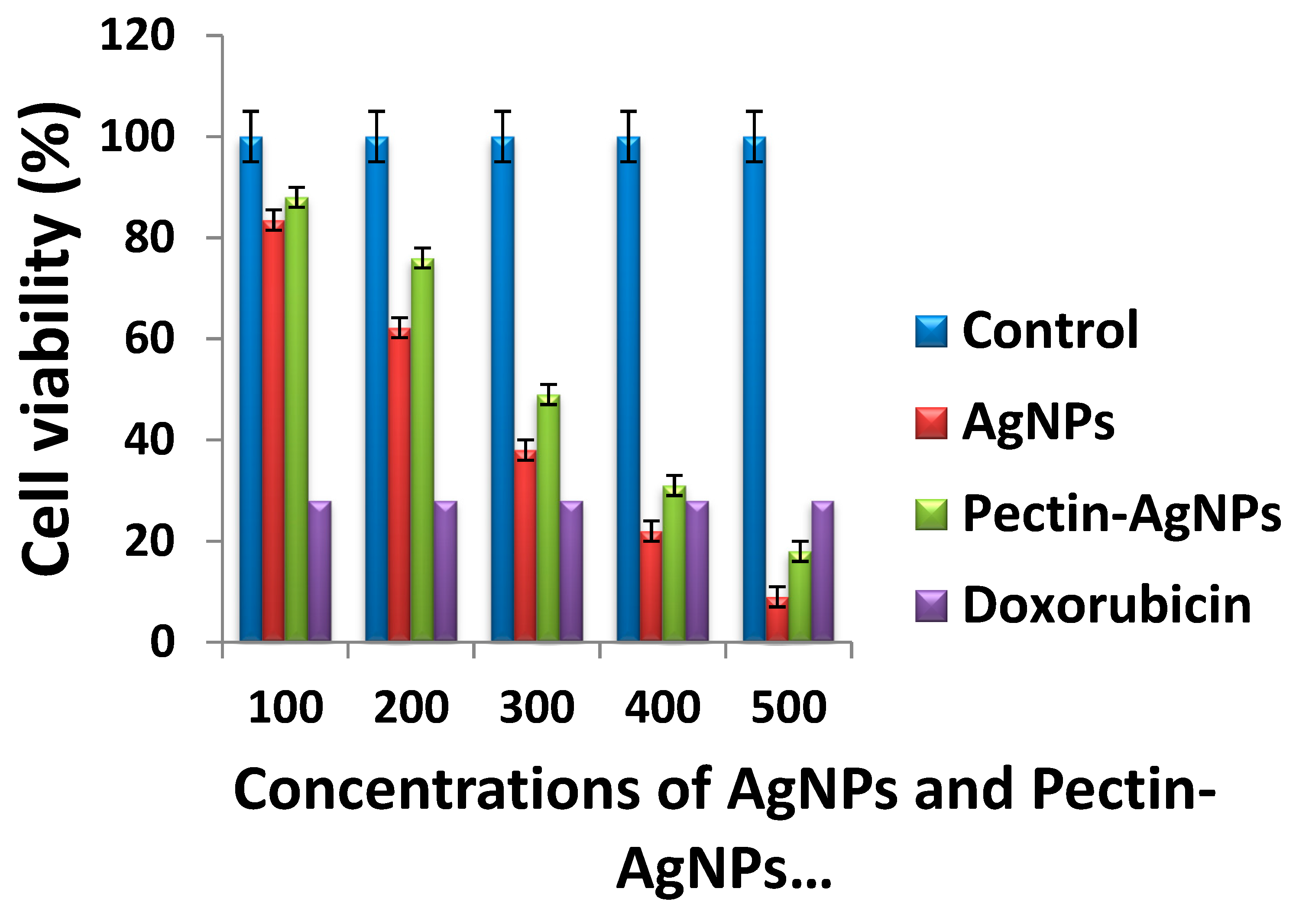

2.9. Cytotoxicity Evaluation

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. GC/MS and LC/MS Analysis of CNEE

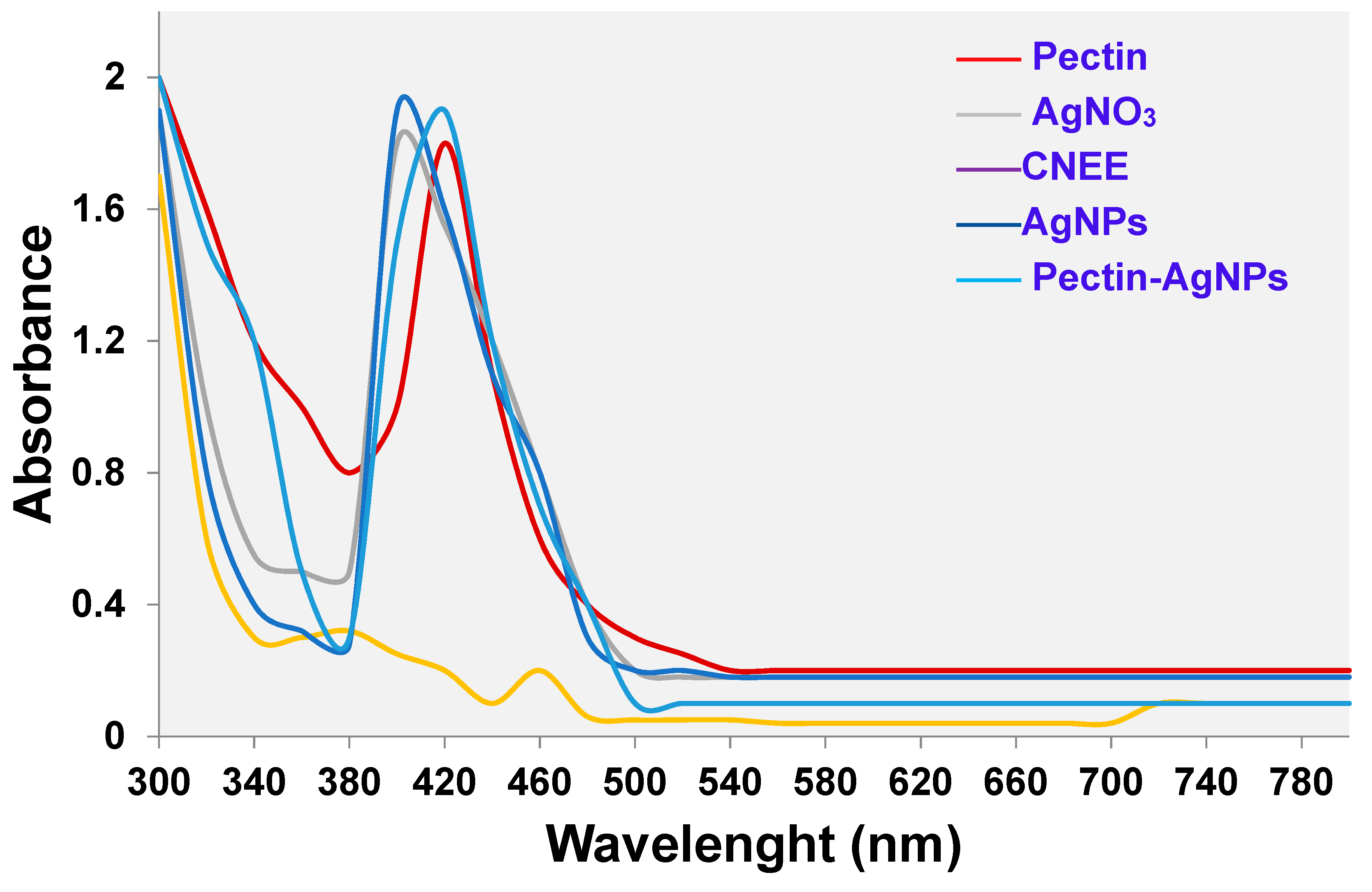

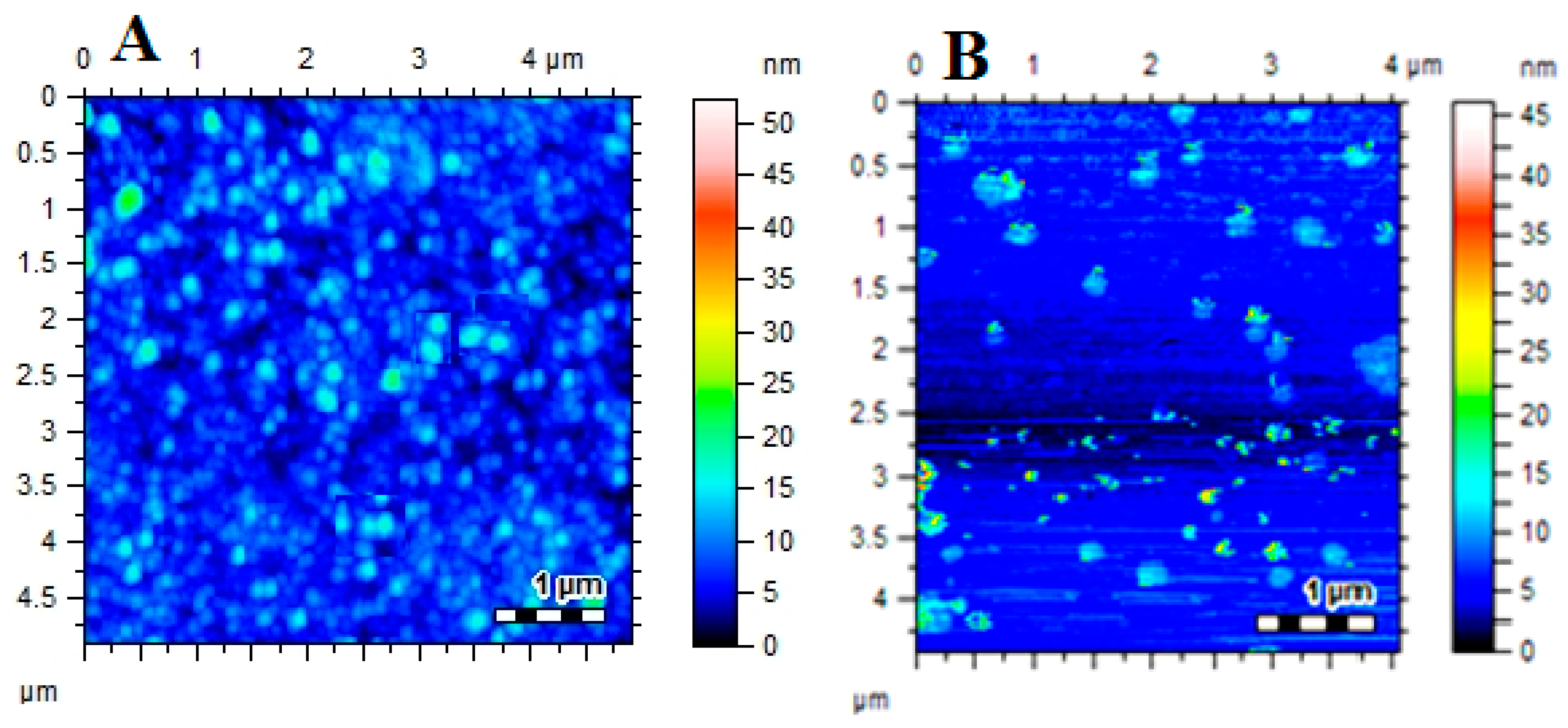

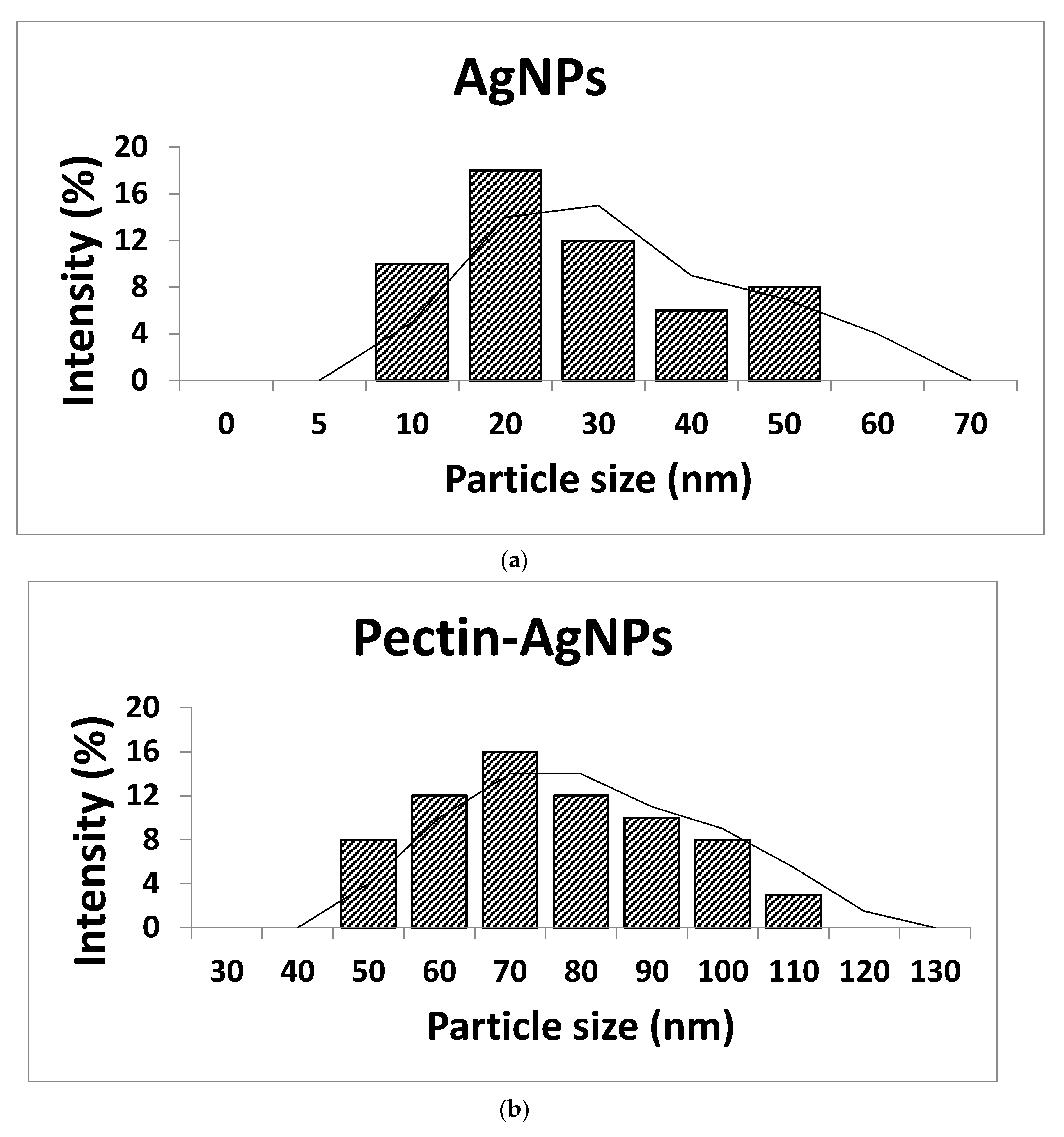

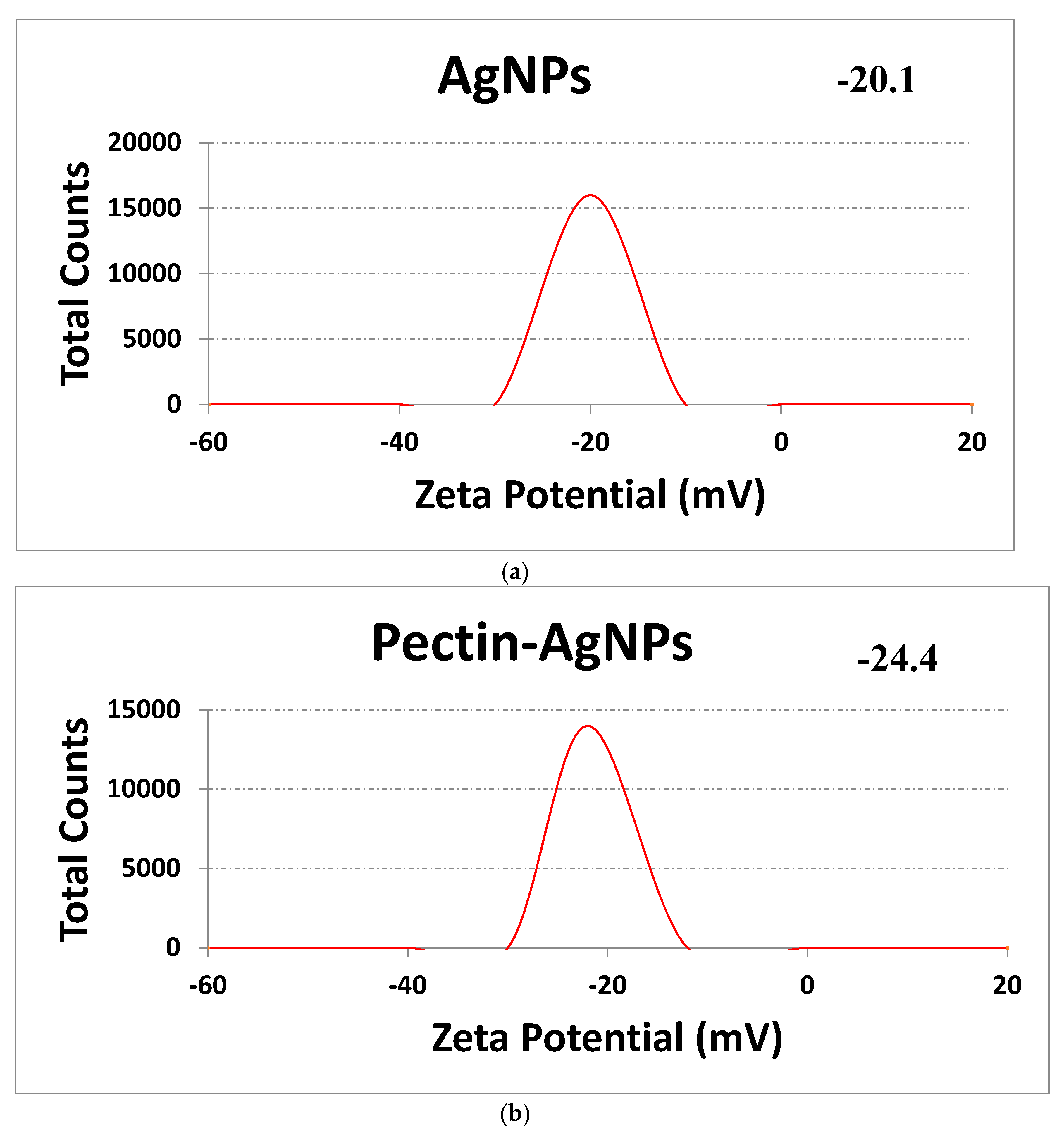

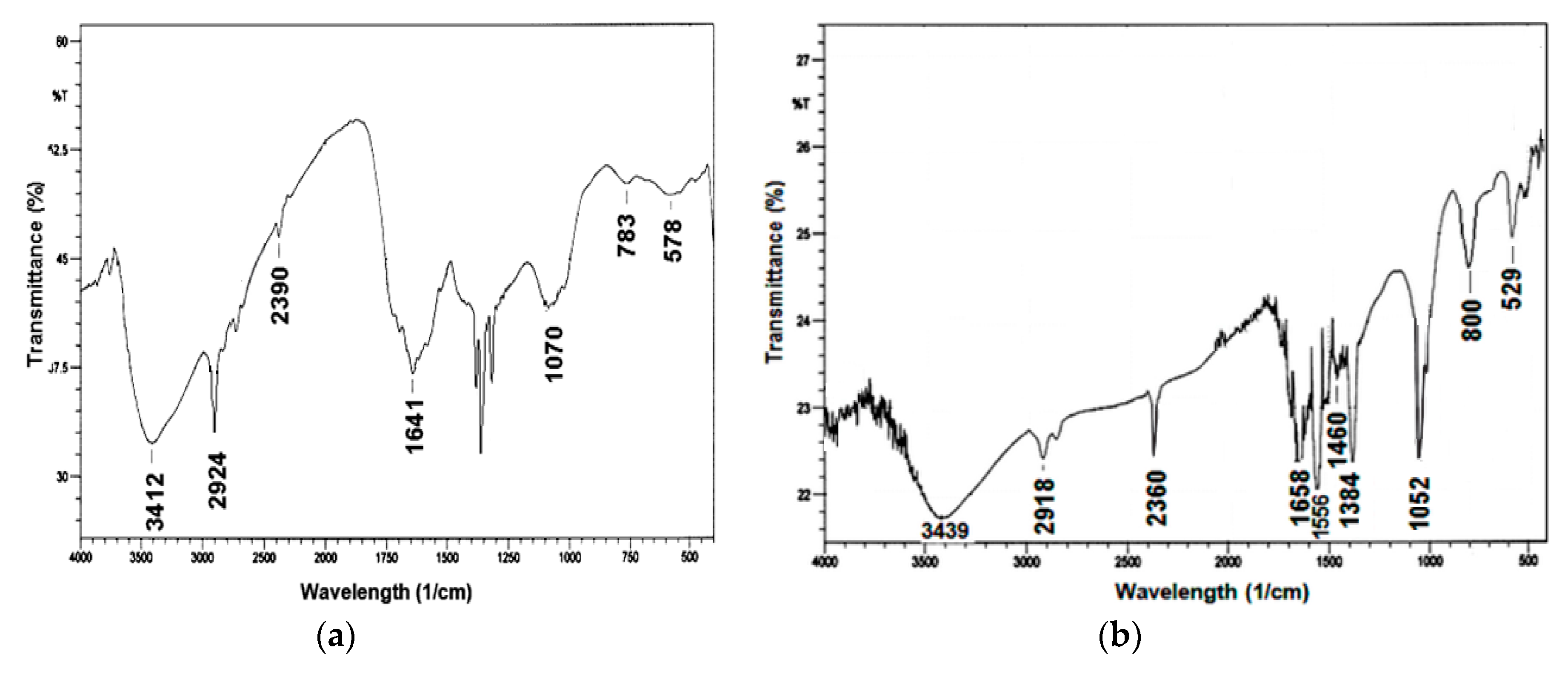

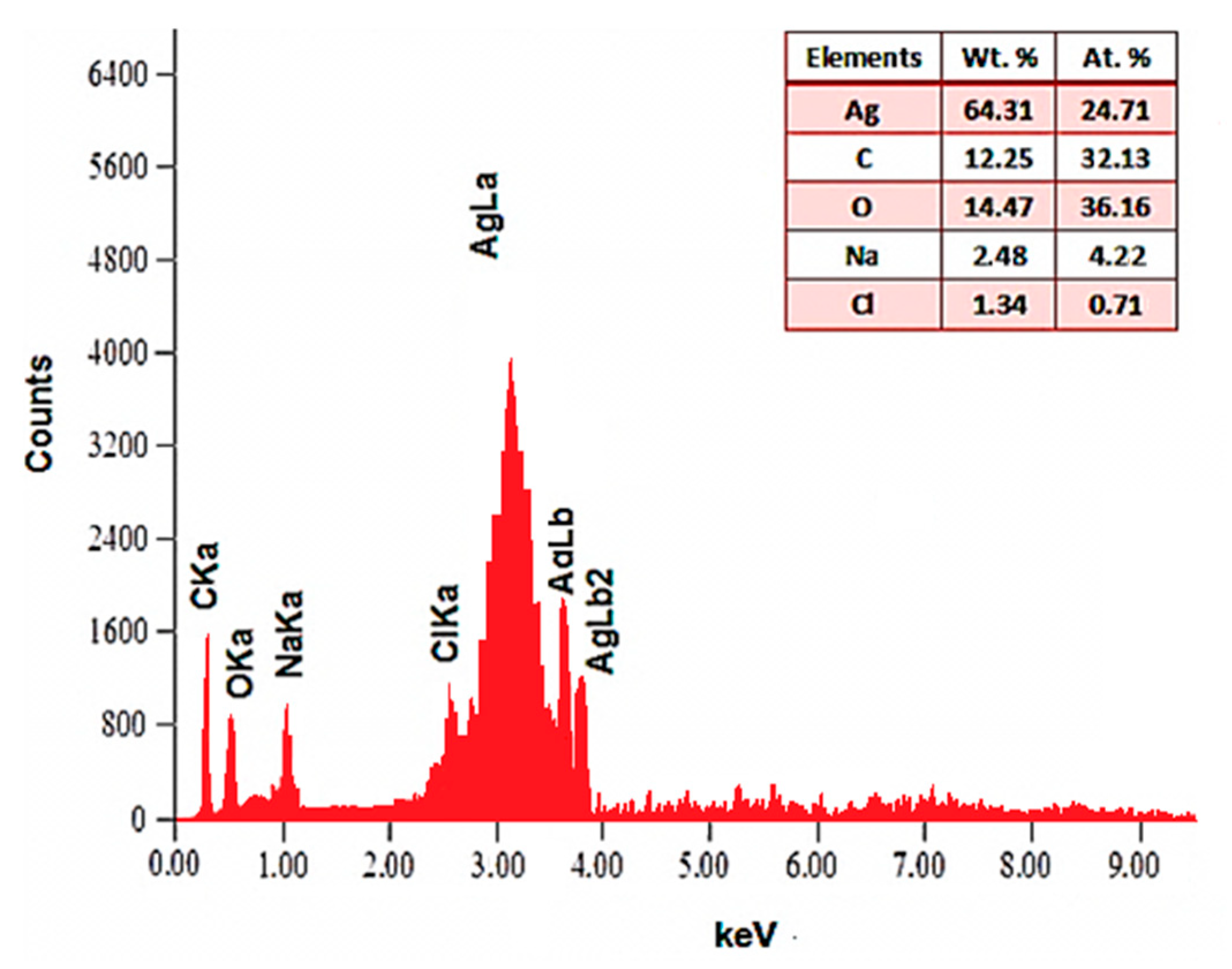

3.2. Synthesis and Characterization of Pectin-AgNPs Nanocomposite

3.3. Antibacterial Activity

3.3.1. Zones of Inhibitions, MICs and MBCs

3.3.2. Time Killing Kinetics

3.3.3. Bacterial Killing Mechanism

3.4. Hepatoprotective Activity

3.4.1. Biochemical Analysis

3.4.2. Histopathological Examination

3.4.3. RT-PCR Assay

3.5. Cytotoxic Activity

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Khawaja Heena, Zahir Erum, Asghar Muhammad Asif, Rafique Kashif, and Asghar Muhammad Arif, Synthesis and Application of Covalently Grafted Magnetic Graphene Oxide Carboxymethyl Cellulose Nanocomposite for the Removal of Atrazine From an Aqueous Phase. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B, 2021: p. 1-20.

- Khawaja Heena, Zahir Erum, Asghar Muhammad Asif, Asghar Muhammad Arif, and Daniel Asher Benjamin, A sustainable nanocomposite, graphene oxide bi-functionalized with chitosan and magnetic nanoparticles for enhanced removal of Sudan dyes. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology, 2021: p. 1-13.

- Asghar Muhammad Asif, Zahir Erum, Shahid Syed Muhammad, Khan Muhammad Naseem, Asghar Muhammad Arif, Iqbal Javed, and Walker Gavin, Iron, copper and silver nanoparticles: Green synthesis using green and black tea leaves extracts and evaluation of antibacterial, antifungal and aflatoxin B1 adsorption activity. Lwt, 2018. 90: p. 98-107.

- Asghar Muhammad Arif, Yousuf Rabia Ismail, Shoaib Muhammad Harris, and Asghar Muhammad Asif, Antibacterial, anticoagulant and cytotoxic evaluation of biocompatible nanocomposite of chitosan loaded green synthesized bioinspired silver nanoparticles. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020. 160: p. 934-943.

- Asghar Muhammad Asif and Asghar Muhammad Arif, Green synthesized and characterized copper nanoparticles using various new plants extracts aggravate microbial cell membrane damage after interaction with lipopolysaccharide. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020. 160: p. 1168-1176.

- Arif Asghar Muhammad, Ismail Yousuf Rabia, Harris Shoaib Muhammad, and Mumtaz Nazish, A Review on Toxicity and Challenges in Transferability of Surface-functionalized Metallic Nanoparticles from Animal Models to Humans. BIO Integration, 2021.

- Khawaja Heena, Zahir Erum, Asghar Muhammad Asif, and Asghar Muhammad Arif, Graphene oxide decorated with cellulose and copper nanoparticle as an efficient adsorbent for the removal of malachite green. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2021. 167: p. 23-34.

- Asghar Muhammad Arif, Yousuf Rabia Ismail, Shoaib Muhammad Harris, Asghar Muhammad Asif, Zehravi Mehrukh, Rehman Ahad Abdul, Imtiaz Muhammad Suleman, and Khan Kamran, Green Synthesis and Characterization of Carboxymethyl Cellulose Fabricated Silver-Based Nanocomposite for Various Therapeutic Applications. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 2021. 16: p. 5371.

- Khawaja Heena, Zahir Erum, Asghar Muhammad Asif, and Asghar Muhammad Arif, Graphene oxide, chitosan and silver nanocomposite as a highly effective antibacterial agent against pathogenic strains. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 2018. 555: p. 246-255.

- Karimi-Maleh Hassan, Ranjbari Sara, Tanhaei Bahareh, Ayati Ali, Orooji Yasin, Alizadeh Marzieh, Karimi Fatemeh, Salmanpour Sadegh, Rouhi Jalal, and Sillanpää Mika, Novel 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide impregnated chitosan hydrogel beads nanostructure as an efficient nanobio-adsorbent for cationic dye removal: Kinetic study. Environmental Research, 2021. 195: p. 110809.

- Makvandi Pooyan, Ghomi Matineh, Padil Vinod VT, Shalchy Faezeh, Ashrafizadeh Milad, Askarinejad Sina, Pourreza Nahid, Zarrabi Ali, Nazarzadeh Zare Ehsan, and Kooti Mohamad, Biofabricated Nanostructures and Their Composites in Regenerative Medicine. ACS Applied Nano Materials, 2020. 3(7): p. 6210-6238.

- Su Dong-lin, Li Pei-jun, Ning Meng, Li Gao-yang, and Shan Yang, Microwave assisted green synthesis of pectin based silver nanoparticles and their antibacterial and antifungal activities. Materials Letters, 2019. 244: p. 35-38.

- Yu Yi-Fan, Li Yue-Qian, Wang Ru-Yue, Liu Xu, Cui Wen-Bo, Chen Xiao-Han, Zhao Cheng-Mu, Qi Feng-Ming, Zhang Zhan-Xin, and Fei Dong-Qing, A new highly oxygenated germacranolide from Carpesium nepalense var. lanatum (CB Clarke) Kitam. Natural product research, 2020: p. 1-8.

- Rusyn Ivan, Arzuaga Xabier, Cattley Russell C, Corton J Christopher, Ferguson Stephen S, Godoy Patricio, Guyton Kathryn Z, Kaplowitz Neil, Khetani Salman R, and Roberts Ruth, Key Characteristics of Human Hepatotoxicants as a Basis for Identification and Characterization of the Causes of Liver Toxicity. Hepatology, 2021.

- Gupta PK, Target Organ Toxicity, in Problem Solving Questions in Toxicology:. 2020, Springer. p. 83-117.

- Jin Yuanyuan, Wang Haixia, Yi Ke, Lv Shixian, Hu Hanze, Li Mingqiang, and Tao Yu, Applications of Nanobiomaterials in the Therapy and Imaging of Acute Liver Failure. Nano-Micro Letters, 2021. 13(1): p. 1-36.

- Recknagel Richard O, Glende Eric A, and Britton Robert S, Free radical damage and lipid peroxidation, in Hepatotoxicology. 2020, CRC press. p. 401-436.

- Pallavicini Piersandro, Arciola CR, Bertoglio Federico, Curtosi S, Dacarro Giacomo, D'Agostino A, Ferrari F, Merli D, Milanese C, and Rossi S, Silver nanoparticles synthesized and coated with pectin: An ideal compromise for anti-bacterial and anti-biofilm action combined with wound-healing properties. Journal of colloid and interface science, 2017. 498: p. 271-281. [CrossRef]

- Shankar Shiv, Tanomrod Nattareya, Rawdkuen Saroat, and Rhim Jong-Whan, Preparation of pectin/silver nanoparticles composite films with UV-light barrier and properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2016. 92: p. 842-849.

- Zhang Hongru, Jacob Joe Antony, Jiang Ziyu, Xu Senlei, Sun Ke, Zhong Zehao, Varadharaju Nithya, and Shanmugam Achiraman, Hepatoprotective effect of silver nanoparticles synthesized using aqueous leaf extract of Rhizophora apiculata. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 2019. 14: p. 3517.

- Shafiq Yousra, Naqvi Syed Baqir Shyum, Rizwani Ghazala H, Asghar Muhammad Arif, Bushra Rabia, Ghayas Sana, Rehman Ahad Abdul, and Asghar Muhammad Asif, A mechanistic study on the inhibition of bacterial growth and inflammation by Nerium oleander extract with comprehensive in vivo safety profile. BMC complementary medicine and therapies, 2021. 21(1): p. 1-19.

- Mumtaz NAZISH, Naqvi SYED BAQIR SHYUM, Asghar MUHAMMAD ARIF, and Asghar MUHAMMAD ASIF, Assessment of antimicrobial activity of Sphaeranthus indicus L. against highly resistant pathogens and its comparison with three different antibiotics. J Dis Glob Health, 2017. 10: p. 67-73.

- Burki Samiullah, Burki Zeba Gul, Jahan Noor, Muhammad Shafi, Mohani Nadeem, Siddiqui Faheem Ahmed, and Owais Farah, GC-MS profiling, FTIR, metal analysis, antibacterial and anticancer potential of Monotheca buxifolia (Falc.) leaves. Pakistan journal of pharmaceutical sciences, 2019. 32.

- Burki Samiullah, Burki Zeba Gul, Shah Zafar Ali, Imran Muhammad, and Khan Muhammad, Phytochemical screening, antioxidant and in vivo neuropharmacological effect of Monotheca buxifolia (Falc.) barks extract. Pakistan journal of pharmaceutical sciences, 2018. 31.

- Asghar Muhammad Arif, Yousuf Rabia Ismail, Shoaib Muhammad Harris, Asghar Muhammad Asif, Ansar Sabah, Zehravi Mehrukh, and Rehman Ahad Abdul, Synergistic Nanocomposites of different antibiotics coupled with green synthesized chitosan-based silver nanoparticles: characterization, antibacterial, in vivo toxicological and biodistribution studies. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 2020. 15: p. 7841.

- Hileuskaya Kseniya, Ladutska Alena, Kulikouskaya Viktoryia, Kraskouski Aliaksandr, Novik Galina, Kozerozhets Irina, Kozlovskiy Artem, and Agabekov Vladimir, ‘Green’approach for obtaining stable pectin-capped silver nanoparticles: Physico-chemical characterization and antibacterial activity. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 2020. 585: p. 124141.

- Eyler RW, Klug ED, and Diephuis Floyd, Determination of degree of substitution of sodium carboxymethylcellulose. Analytical chemistry, 1947. 19(1): p. 24-27. [CrossRef]

- Asghar Muhammad Asif, Asghar Muhammad Arif, Rehman Ahad A, Khan Kamran, Zehravi Mehrukh, Ali Shoukat, and Ahmed Aftab, Synthesis and characterization of graphene oxide nanoparticles and their antimicrobial and adsorption activity against aspergillus and aflatoxins. Lat Am J Pharm, 2019. 38: p. 1036-44.

- Shafiq Yousra, Naqvi Syed Baqir Shyum, Rizwani Ghazala H, Abbas Tanveer, Sharif Huma, Ali Huma, Asghar Muhammad Arif, Bushra Rabia, Zafar Farya, and Abdein Saima, Assessment of killing kinetics assay and bactericidal mechanism of crude methanolic bark extract of Casuarina equisetifolia. Pak J Pharm Sci, 2018. 31(5): p. 2143-8.

- Shafiq Yousra, Asghar Muhammad Arif, Ali Huma, Abedin Saima, Rehman Ahad Abdul, and Anser Humaira, In vitro assessment of antimicrobial potential of Ethanolic and aqueous extract of Phlomis Umbrosa against some highly resistant pathogens. Annals of Jinnah Sindh Medical University, 2020. 6(1): p. 3-9.

- Mumtaz Nazish, Asghar Muhammad Arif, Naqvi Syed Baqir Shyum, Asghar Muhammad Asif, Raza Muhammad Liaquat, and Rehman Ahad Abdul, Time kill assay and bactericidal mechanism of action of ethanolic flowers extract of Sphaeranthus indicus. RADS Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2019. 7(1): p. 27-33.

- Rehman Ahad Abdul, Riaz Azra, Asghar Muhammad Arif, Raza Muhammad Liaquat, Ahmed Shadab, and Khan Kamran, In vivo assessment of anticoagulant and antiplatelet effects of Syzygium cumini leaves extract in rabbits. BMC complementary and alternative medicine, 2019. 19(1): p. 1-8.

- Close Bryony, Banister Keith, Baumans Vera, Bernoth Eva-Maria, Bromage Niall, Bunyan John, Erhardt Wolff, Flecknell Paul, Gregory Neville, and Hackbarth Hansjoachim, Recommendations for euthanasia of experimental animals: Part 1. Laboratory animals, 1996. 30(4): p. 293-316.

- Zakaria ZA, Rofiee MS, Somchit MN, Zuraini A, Sulaiman MR, Teh LK, Salleh MZ, and Long K, Hepatoprotective activity of dried-and fermented-processed virgin coconut oil. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2011. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Burki Samiullah, Burki Zeba Gul, Asghar Muhammad Arif, Ali Imdad, and Zafar Saba, Phytochemical, acute toxicity and renal protective appraisal of Ajuga parviflora hydromethanolic leaf extract against CCl4 induced renal injury in rats. BMC complementary medicine and therapies, 2021. 21(1): p. 1-14.

- Chen Hailong, Wu Rui, Xing Yuan, Du Quanli, Xue Zerun, Xi Yanli, Yang Yujie, Deng Yangni, Han Yuewen, and Li Kaixin, Influence of different inactivation methods on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 RNA copy number. Journal of clinical microbiology, 2020. 58(8): p. e00958-20.

- Javanmard Shaghayegh Haghjooy, Vaseghi Golnaz, Ghasemi Ahmad, Rafiee Laleh, Ferns Gordon A, Esfahani Hajar Naji, and Nedaeinia Reza, Therapeutic inhibition of microRNA-21 (miR-21) using locked-nucleic acid (LNA)-anti-miR and its effects on the biological behaviors of melanoma cancer cells in preclinical studies. Cancer cell international, 2020. 20(1): p. 1-12.

- Keskes Henda, Belhadj Sahla, Jlail Lobna, El Feki Abdelfattah, Damak Mohamed, Sayadi Sami, and Allouche Noureddine, LC-MS–MS and GC-MS analyses of biologically active extracts and fractions from Tunisian Juniperus phoenice leaves. Pharmaceutical Biology, 2017. 55(1): p. 88-95.

- Hajji Mohamed, Jarraya Raoudha, Lassoued Imen, Masmoudi Ons, Damak Mohamed, and Nasri Moncef, GC/MS and LC/MS analysis, and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of various solvent extracts from Mirabilis jalapa tubers. Process Biochemistry, 2010. 45(9): p. 1486-1493.

- Roy Nayan, Mondal Samiran, Laskar Rajibul A, Basu Saswati, Mandal Debabrata, and Begum Naznin Ara, Biogenic synthesis of Au and Ag nanoparticles by Indian propolis and its constituents. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2010. 76(1): p. 317-325.

- Reda May, Ashames Akram, Edis Zehra, Bloukh Samir, Bhandare Richie, and Abu Sara Hamed, Green synthesis of potent antimicrobial silver nanoparticles using different plant extracts and their mixtures. Processes, 2019. 7(8): p. 510.

- Tummalapalli Mythili, Deopura BL, Alam MS, and Gupta Bhuvanesh, Facile and green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using oxidized pectin. Materials science and engineering: C, 2015. 50: p. 31-36.

- Zahran MK, Ahmed Hanan B, and El-Rafie MH, Facile size-regulated synthesis of silver nanoparticles using pectin. Carbohydrate polymers, 2014. 111: p. 971-978. [CrossRef]

- Asghar Muhammad Asif, Zahir Erum, Asghar Muhammad Arif, Iqbal Javed, and Rehman Ahad Abdul, Facile, one-pot biosynthesis and characterization of iron, copper and silver nanoparticles using Syzygium cumini leaf extract: As an effective antimicrobial and aflatoxin B1 adsorption agents. PloS one, 2020. 15(7): p. e0234964.

- Sun Di, Kang Shifei, Liu Chenglu, Lu Qijie, Cui Lifeng, and Hu Bing, Effect of zeta potential and particle size on the stability of SiO2 nanospheres as carrier for ultrasound imaging contrast agents. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci, 2016. 11(10): p. 8520-8529.

- Jyoti Kumari, Baunthiyal Mamta, and Singh Ajeet, Characterization of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Urtica dioica Linn. leaves and their synergistic effects with antibiotics. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences, 2016. 9(3): p. 217-227.

- Asghar Muhammad Arif, Yousuf Rabia Ismail, Shoaib Muhammad Harris, and Asghar Muhammad Asif, Antibacterial, anticoagulant and cytotoxic evaluation of biocompatible nanocomposite of chitosan loaded green synthesized bioinspired silver nanoparticles. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020.

- Cakić Milorad, Glišić Slobodan, Nikolić Goran, Nikolić Goran M, Cakić Katarina, and Cvetinov Miroslav, Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of dextran sulphate stabilized silver nanoparticles. Journal of Molecular Structure, 2016. 1110: p. 156-161.

- Ciriminna Rosaria, Fidalgo Alexandra, Meneguzzo Francesco, Presentato Alessandro, Scurria Antonino, Nuzzo Domenico, Alduina Rosa, Ilharco Laura M, and Pagliaro Mario, Pectin: A long-neglected broad-spectrum antibacterial. ChemMedChem, 2020. 15(23): p. 2228-2235.

- Ighodaro Osasenaga Macdonald and Akinloye Oluseyi Adeboye, Sapium ellipticum (Hochst) Pax leaf extract: antioxidant potential in CCl4-induced oxidative stress model. Bulletin of Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University, 2018. 56(1): p. 54-59.

- Al-Dbass Abeer M, Al-Daihan Sooad K, and Bhat Ramesa Shafi, Agaricus blazei Murill as an efficient hepatoprotective and antioxidant agent against CCl4-induced liver injury in rats. Saudi journal of biological sciences, 2012. 19(3): p. 303-309.

- Tian Zhiqiang, Liu Hong, Su Xiaofang, Fang Zheng, Dong Zhitao, Yu Changchun, and Luo Kunlun, Role of elevated liver transaminase levels in the diagnosis of liver injury after blunt abdominal trauma. Experimental and therapeutic medicine, 2012. 4(2): p. 255-260.

- Suja SR, Latha PG, Pushpangadan P, and Rajasekharan S, Assessment of hepatoprotective and free radical scavenging effects of Rhinacanthus nasuta (Linn.) Kurz in Wistar rats. Journal of Natural Remedies, 2004. 4(1): p. 66-72.

- Neal Jeremy L, Lowe Nancy K, and Corwin Elizabeth J, Serum lactate dehydrogenase profile as a retrospective indicator of uterine preparedness for labor: a prospective, observational study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 2013. 13(1): p. 1-8.

- Kumar Manoj, Ranjan Rakesh, Kumar Amar, Sinha Manoranjan Prasad, Srivastava Rohit, Subarna Sweta, and Kumar Mandal Samir, Hepatoprotective activity of Silver Nanoparticles synthesized using aqueous leaf extract of Punica granatum against induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Nova Biologica Reperta, 2021. 7(4): p. 381-389.

- Zhang Jian-Ping, Wang Guo-Wei, Tian Xin-Hui, Yang Yong-Xun, Liu Qing-Xin, Chen Li-Ping, Li Hui-Liang, and Zhang Wei-Dong, The genus Carpesium: A review of its ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 2015. 163: p. 173-191.

- Vasilenko Yu K, Moskalenko SV, Kaisheva N Sh, Frolova LM, Shcherbak SN, and Mokin Yu N, Extraction of pectins and investigation of their physicochemical and hepatoprotective properties. Pharmaceutical chemistry journal, 1997. 31(6): p. 303-305.

- Galván-Peña Silvia, Carroll Richard G, Newman Carla, Hinchy Elizabeth C, Palsson-McDermott Eva, Robinson Elektra K, Covarrubias Sergio, Nadin Alan, James Andrew M, and Haneklaus Moritz, Malonylation of GAPDH is an inflammatory signal in macrophages. Nature communications, 2019. 10(1): p. 1-11.

- Millet Patrick, Vachharajani Vidula, McPhail Linda, Yoza Barbara, and McCall Charles E, GAPDH binding to TNF-α mRNA contributes to posttranscriptional repression in monocytes: a novel mechanism of communication between inflammation and metabolism. The Journal of Immunology, 2016. 196(6): p. 2541-2551.

- Teja Kavalipurapu Venkata, Ramesh Sindhu, and Priya Vishnu, Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-3 gene expression in inflammation: A molecular study. Journal of conservative dentistry: JCD, 2018. 21(6): p. 592.

- Varga Tamas, Czimmerer Zsolt, and Nagy Laszlo, PPARs are a unique set of fatty acid regulated transcription factors controlling both lipid metabolism and inflammation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease, 2011. 1812(8): p. 1007-1022.

- Burki Samiullah, Burki Zeba Gul, Ahmed Ijaz, Jahan Noor, Owais Farah, Tahir Nasim, and Khan Muhammad, GC/MS assisted phytochemical analysis of Ajuga parviflora leaves extract along with anti-hepatotoxic effect against anti-tubercular drug induced liver toxicity in rat. Pakistan journal of pharmaceutical sciences, 2020. 33.

- Wu Liwei, Guo Chuanyong, and Wu Jianye, Therapeutic potential of PPARγ natural agonists in liver diseases. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine, 2020. 24(5): p. 2736-2748.

| Antimicrobial agents | Zone of Inhibition (mm ± S.D) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis | K. pneumonia | MRSA | V. cholerae | |

| Control | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| CNEE | 6.9 ± 0.41 | 4.1 ± 0.15 | 8.3 ± 0.82 | 7.2 ± 0.26 |

| Pectin | 11.9 ± 1.38 | 13.8 ± 1.24* | 12.4 ± 1.33* | 10.3 ± 0.84 |

| AgNPs | 18.7 ± 2.18* | 17.3 ± 1.04* | 17.6 ± 1.83* | 15.2 ± 1.51* |

| Pectin-AgNPs | 27.2 ± 3.84** | 26.1 ± 2.18** | 24.8 ± 3.71** | 25.2 ± 2.46** |

| Cefoxitin | 13.7 ± 0.86* | 14.8 ± 1.01* | 13.1 ± 0.53* | 12.5 ± 0.64* |

| Isolates | Antimicrobial agents | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNEE | Pectin | AgNPs | Pectin-AgNPs | |||||

| MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |

| B. subtilis | 5500 ± 271.3 | 6500 ± 226.1 | 256 ± 35.2 | 512 ± 81.2 | 128 ± 27.4 | 256 ± 56.2 | 64 ± 10.3 | 128 ± 14.9 |

| K .pneumonia | 7500 ± 364.2 | 8500 ± 421.2 | 512 ± 73.1 | 512 ± 57.5 | 256 ± 21.3 | 256 ± 42.5 | 128 ± 9.2 | 128 ± 16.4 |

| MRSA | 7500 ± 393.5 | 8500 ± 463.8 | 512 ± 84.6 | 512 ± 77.4 | 256 ± 18.2 | 256 ± 61.7 | 128 ± 9.1 | 128 ± 10.5 |

| V. cholera | 8500 ± 336.4 | 9500 ± 392.3 | 512 ± 52.4 | 512 ± 62.8 | 256 ± 31.8 | 256 ± 40.0 | 128 ± 11.5 | 128 ± 13.1 |

| Groups | Doses (mg/kg) |

CCl4 induced hepatotoxicity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDH (IU/dL) |

AST (IU/L) |

ALT (IU/L) |

ALP (IU/L) |

TP (g/dL) |

DB (mg/dL) |

||

| Naïve1 | –– | 210 ± 12.86 | 69.1 ± 1.54 | 62.0 ± 2.16 | 91.36 ± 2.49 | 6.5 ± 0.23 | 0.12 ± 0.05 |

| Positive control | –– | 322.4 ± 25.64 | 228.2 ± 5.22 | 195.0 ± 4.03 | 233.4 ± 6.85 | 3.0 ± 0.28 | 0.79 ± 0.08 |

| CNEE | 125 | 287.5 ± 18.53 | 184.6 ± 8.12 | 172.4 ± 5.75 | 198.2 ± 4.40 | 3.9 ± 0.27 | 0.67 ± 0.12 |

| 250 | 271.4 ± 21.65 | 175.1 ± 6.58 | 160.2 ± 7.52 | 184.0 ± 5.62 | 4.1 ± 0.64 | 0.61 ± 0.16 | |

| Pectin | 0.025 | 291.6 ± 31.57 | 193.4 ± 7.15 | 184.1 ± 6.36 | 212.6 ± 5.84 | 3.5 ± 0.40 | 0.71 ± 0.10 |

| 0.05 | 286.4 ± 28.14 | 182.5 ± 5.67 | 175.8 ± 6.06 | 201.9 ± 4.95 | 3.8 ± 0.51 | 0.68 ± 0.12 | |

| AgNPs | 0.025 | 255.3 ± 21.90* | 156.0 ± 7.03* | 134.0 ± 3.58* | 158.2 ± 3.27* | 4.1 ± 0.72* | 0.45 ± 0.09* |

| 0.05 | 238.7 ± 26.52* | 121.1 ± 8.94* | 110.2 ± 4.04* | 121.5 ± 4.18* | 4.8 ± 0.78* | 0.32 ± 0.08* | |

| Pectin-AgNPs | 0.025 | 231.7 ± 21.76** | 108.0 ± 4.0** | 96.5 ± 6.53** | 96.5 ± 4.55** | 5.5 ± 0.46** | 0.20 ± 0.02** |

| 0.05 | 221.5 ± 18.22** | 76.5 ± 2.0** | 74.2 ± 2.34** | 82.3 ± 2.64** | 7.8 ± 1.03** | 0.15 ± 0.02** | |

| Silymarin | 100 | 235.6 ± 24.64** | 93.5 ± 4.2** | 82.2 ± 2.09** | 98.2 ± 4.02** | 6.1 ± 0.33** | 0.32 ± 0.06* |

| Histopathological findings | Naïve | Positive control | Pectin-AgNPs (0.025 mg/kg) |

Pectin-AgNPs (0.05 mg/kg) |

Standard (Silymarin) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydropic degeneration | ˗ | ++ | ˗ | ˗ | ˗ ˗ |

| Endothelium disruption | ˗ | +++ | + | ˗ | ˗ |

| Lymphocytic infiltration | ˗ | ++ | + | ˗ | ˗ |

| Lymphoid aggregate in portal vein | ˗ | +++ | + | ˗ | ˗ ˗ |

| Cytolysis | ˗ | + | ˗ | ˗ | ˗ ˗ |

| Congestion | ˗ | ++ | + | ˗ | + |

| Glucagon depletion | ˗ | ++ | + | ˗ | ˗ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).