1. Introduction

Nearly every physical phenomenon in the world can be explained using either general relativity or quantum mechanics, two fundamental theoretical frameworks. These conceptual frameworks contain the ideas and models that describe matter and its fundamental interactions and are capable of predicting a wide range of empirically observed events. Quantum mechanics (QM) and special theory of relativity (SR) describe interactions between atoms, molecules, elementary particles like electrons, muons, photons, and quarks and their anti-particles at very small scales, of the order of to m, in the physical framework of the standard model of particle physics (SM) and the mathematical disguise of quantum field theory (QFT).

In the context of SM, QM primarily describes interactions involving the electromagnetic, weak nuclear, and strong nuclear forces, three of the four basic forces. The General Relativity (GR) paradigm explains how matter responds to the gravitational force, which is the fourth basic force of nature. When compared to classical physics, including GR and its consequences, QM uses a conceptual framework that is significantly different. The conceptual distinction between classical and quantum physics is largely based on the Heisenberg uncertainty principle (HUP). HUP asserts that, in sharp contrast to classical mechanics, it is impossible to have a particle for which a pair of canonically conjugate quantities, such as position and momentum, are precisely defined to any arbitrary limit even if all other conditions are satisfied.

Despite its many accomplishments, the Standard Model of Particles (SM) and Quantum Field Theory (QM) cannot be viewed as the whole theory of the visible world. This is due to a several weaknesses, especially the inability of these theories to explain how basic particles behave in the presence of gravitational interactions, the last of the four fundamental interactions. This results from interpreting spacetime as an unchanging, flat background, which General Relativity (GR) demonstrates is not the case in the following.

On the other hand, the general theory of relativity (GR), which is the dominant explanation of gravity, postulates that the apparent gravitational force between masses is brought about by the bending of spacetime that these masses have on space. The gravitational field is therefore geometric in character. Flat spacetime appears to be bent by mass and energy into a four-dimensional Riemannian manifold with an affine (linear) link and a symmetric metric tensor. The latter may be calculated in terms of the metric tensor itself since it is torsion-free and metric compatible.

General relativity (GR) has been successfully tested using high-precision astronomical and cosmic data like as the perihelion precession of Mercury’s orbit, gravitational lensing, gravitational red shift of light, the rapid expansion of our universe, and gravitational waves.

In reality, gravitational interactions are the only ones that matter at astronomically large distances and/or matter densities, and when combined with the so-called dark matter and dark energy, they provide an almost complete account of the composition and development of the universe from its inception to its ultimate end.

Even on a curved space-time background, the special theory of relativity appears to be completely consistent with quantum mechanics. However, it appears that there are still lingering discrepancies between QM and classical GR that prevent their reconciliation. Such incompatibilities include, in addition to the well-known renormalizability issue, which may have been resolved in a few Quantum Gravity theories like String Theory and Loop Quantum Gravity. Due to the fuzziness (uncertainty) of position and velocity in quantum mechanics, it is still unknown how to estimate the gravitational field of a quantum particle. Additionally, time has a distinct meaning in quantum mechanics and classical general relativity.

In contrast to QM’s conception of spacetime as a flat, static background, general relativity (GR) sees it as a dynamic object that interacts with matter and energy. On the other hand, GR disregards the probabilityistic nature of the observables described by QM. In order to reproduce QM and GR in their respective disciplines, a new theory must be created. Unfortunately, the simple approach of applying QFT principles to GR doesn’t work as expected based on prior experience. this is due to the fact that no finite measurable result is obtained when perturbatively quantized gravity is subjected to renormalization procedures intended to tame divergences. As a result, it might be assumed that a new approach is essential to tackle QG in a unique way. The phrase "theories of quantum gravity" (QG) designates a range of models and/or theories that have been created to tackle the problem of quantizing gravity. These QG class of theories/models, for instance, include Doubly Special Relativity (DSR), Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG), and String Theory (ST). These are only a handful of the initiatives that have been made to address the problem, all of which have varied degrees of success. There are several long-standing problems with quantum gravity theories and methodologies and a comprehensive overview may be found in Reference [

1].

The so-called Generalised Uncertainty Principle (GUP) is one of many approaches to a consistent theory of Quantum Gravity (QG), particularly those class of models attempting to modify the classical GR using quantum arguments [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The GUP predicts a deformed canonical commutator as a modified Heisenberg uncertainty relation. Surprisingly, GUP can result in certain phenomenological quantum gravity models that can,

a priori, be investigated at low energies [

15,

16].

A fundamental physical minimum length and/or a generalized uncertainty principle (GUP) near the Planck scale are suggested by string theory, loop quantum gravity, doubly special relativity, and black hole thermodynamics, to name a few. For an extensive account, see for example [

17]. Moreover, in [

16,

18], the three primary techniques for a GUP are motivated. Using arguments from Quantum Gravity and String Theory [

8], as well as from other, more specialised quantum mechanical and group theoretical arguments [

19], a GUP recipe has been developed that characterises the minimal length as a minimal uncertainty in position measurements. This recipe is the one we’ll use in the current work.

The general relativity (GR) theory is well described by curved spacetime, in which the dynamical variable is the spacetime curvature; the gravity [

20]. The general theory of relativity assumes that the gravitational field has a geometrical nature. This is a four–dimensional Riemannian manifold having a symmetric metric tensor and an affine (linear) connection. The latter is torsion–free and metric compatible and thus can be determined in terms of the metric tensor, itself. The deformed affine connection can be defined by the deformed metric tensor [

21]. The deformed affine connection

is symmetric under interchange of its lower indices like the classical affine connection.

The present script introduces a minimal length approach, in which the inherent uncertainties emerging in detecting a quantum state are constrained in noncommutative operators as governed by Heisenberg uncertainty principle (HUP), which limits these to simultaneous measurements but obviously doesn’t incorporate the impacts of the gravitational fields. The extended version of HUP known as generalized uncertainty principle (GUP) is also predicted in string theory, loop quantum gravity, doubly special relativity, and various gedanken experiments [

18,

22]. GUP could be seen as an approach emerging from the gravitational impacts on the quantum measurements. The latter are essential components of the underlying quantum theory. In other words, GUP helps explaining the origin of the gravitational field and how a particle behaves in it [

23,

24].

Riemann curvature tensor, Ricci tensor, Ricci scalar, and Einstein tensor are the geometric entities that describe the curvature of space-time manifold. The Riemann tensor is a (1,3) rank tensor and its components represent the change of a vector after the parallel transport of it around a loop.

The possible contraction of the Riemann tensor gives a second rank tensor called Ricci tensor. The contraction of Ricci tensor gives a zero tank tensor (scalar) called Ricci scalar. Based on a combination of Ricci tensor and Ricci scalar, the Einstein tensor has been constructed.

The present script is organized as follows. A short review of minimal measurable length,

Section 2. The deformed line element and deformed affine connection is discussed in

Section 3. The deformation of Riemann manifold based on the deformed affine connection

Section 4. The minimal length deformation of the Ricci curvature tensor and Ricci scalar are derived in

Section 5 and

Section 6, respectively. The construction of the deformed Einstein tensor and its covariant derivative are discussed in

Section 7.

Section 8 is devoted to the summary and conclusion.

2. Minimal measurable length

The loop quantum gravity, doubly–special relativity, and string theory, for instance, predicted an existence of a minimum measurable length. In quantum mechanics, this can be translated to nonvanishing position uncertainty due to the impacts of finite gravitational field on the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, the fundamental theory of quantum mechanics [

25],

where

is the momentum expectation value and

and

represents the length and momentum uncertainties, respectively. The GUP parameter

with

a dimensionless numerical coefficient to be determined from table–top laboratory experiments [

26] or recent cosmological observations [

27,

28] introduces the consequences of gravity to the uncertainty principle, where

G is the gravitational constant,

c is the speed of light,

ℏ is the reduced Planck constant, and

is the Planck length. The commutation relation of position and momentum operators can be given as

The GUP approach, Eq. (

2), has been successfully applied to various physical problems [

29,

30] and quantum mechanical corrections [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

The minimum uncertainty of position

for all values of expectation values of momentum

will be

then the absolute minimum uncertainty of position is at

,

The value of

can be considered as the possible minimal length according to the GUP, which represents the effect of gravitational field on the QM, then the minimal length is emerging as follows

Another approach for the existence of minimal length may be assumed as a fundamental physical quantity obtained from a combination of fundamental physical quantities, gravitational constant (

G) from gravity, reduced Planck constant (

ℏ) from quantum mechanics, and speed of light (

c) from spacial relativity [

36]. The minimal length will be

where

is called Planck length. The minimal length according to that approach is a universal constant like

ℏ,

G, and

c.

The existence of maximal acceleration can be related to the existence of minimal length as a combination of fundamental physical quantities [

37],

According to the GUP definition of minimal length stated in Eq. (

5), the maximal acceleration can be defined as the following,

3. The deformed line element and deformed affine connection

Caianiello suggested that curvature in relativistic eight–dimensional manifold

is conjectured to mimic deformation of the four–dimensional spacetime manifold

; Riemannian manifold [

38,

39,

40,

41]. The eight dimensions

can be expressed as

where

is the four spacetime dimensions,

is the four velocity,

is the classical line element,

,

,

L is the minimal length.

L may be defined according to GUP as a minimal uncertainty of positions

[

25] or one can consider the value of minimal length to be the Planck length

.

With minimal length-induced corrections, the line element on eight–dimensional manifold

[

42,

43] reads,

where

is a result of outer product;

, where

is the classical metric tensor. Substitutes for

and

from Eq.(

9) into Eq.(

10), to get

where

,

is the classical line element,

where

is the acceleration,

,

are dummy indices, and

, then

,

where

. The deformed line element in four dimensions spacetime, as a projection from eight dimensions onto four dimensions, will be

where

is assumed deformed metric tensor, which will be calculated by equating Eqs.(

13), and (

14),

where

,

,

are dummy indices,

, and

are free indices.

The entire contribution of the existence of minimal length according to GUP is summarized in the term

and the definition of minimal length based on the combination of fundamental physical quantities will be

where

.

For flat spacetime,

where

is the classical metric tensor in flat spacetime.

The correction factor of deformed metric tensor can be redefined by the maximal acceleration

, where

[

37], the deformed metric tensor will be

where

.

The symmetry property, and the compatibility of deformed metric tensor is discussed in [

21], where the deformed metric tensor is symmetric and compatible as the classical metric tensor. The deformed affine connection

has been derived in [

21], and found to be

where

is the classical affine connection. The deformed affine connection where proven to be symmetric in its lower indices [

21].

4. Deformed Riemann curvature tensor

In GR, the components of the Riemann curvature tensor

can be constructed from the affine connection [

44,

45,

46],

This expression holds for all connections regardless of their metric compatibility or torsion-freedom property [

44]. Accordingly, the deformed Riemann tensor can be expressed in terms of the deformed affine connections and their derivatives as follows

We can substitute from Eq. (

20) into Eq. (

22) for the deformed affine connection in terms of the classical one,

Thus, we can straightforwardly derive the derivative of the deformed affine connection to be

where

,

are dummy indices,

, and

, as elaborated in

Appendix A. Similarly,

With

, we will replece

by

in equations (

27), and (

28). By substituting into Eq. (

22), the minimal length-induced correction to the Riemann curvature tensor are

Taking common factors , and rearranging, we obtain

In Eq. (

30), the partial derivatives of all metric tensors

, and

can respectively be replaced by metric tensors and affine connections as follows

By using delta tensor to transform the dummy indices, Eq. (

33) could be reexpressed as,

substitute by Eq. (

21) into Eq. (

34) for

,

and take

as a common factor,

and simplify the second term of Eq. (

36),

Equation (

37) generalizes the Riemann curvature tensor by introducing the effect of minimal length. At vanishing

and/or

, the undeformed Riemann curvature tensor

could entirely be retrieved.

The eminent ingredients added by the correction

can be illustrated in an example of a sphere surface (two-dimensional manifold) with radius

. The complementary geometric structure likely reveals supplementary insights to be discovered. The Cartesian coordinates could be expressed by polar coordinates; radius

r, inclination

, and azimuth

as

,

, and

. As shown in Eqs. (

15), (

23)–(), the minimal length induced corrections originated in

are combined in the deformed metric tensor and connection. Therefore, we just need to determine the components of the classical metric tensor

and coefficients of the classical connections

Then, the corresponding coefficients of deformed Riemann curvature tensor are given as

which means that at the poles, where

,

, i.e., finite, as well as at the equator, where

,

, i.e., finite as well. These two examples highlight the significance of the minimal length contributions encoded in

. In the classical limit, i.e., vanishing

and/or

, only finite

signals curved spaces, as this exclusively depends on the inclination. For instance, at the poles, the space is flat! with this correction, this isn’t necessarily the case everywhere. The only exception might be

in units of

. Here, both classical and deformed coefficients

indeed vanish, at

, while their values, at

, are also coincident and positive.

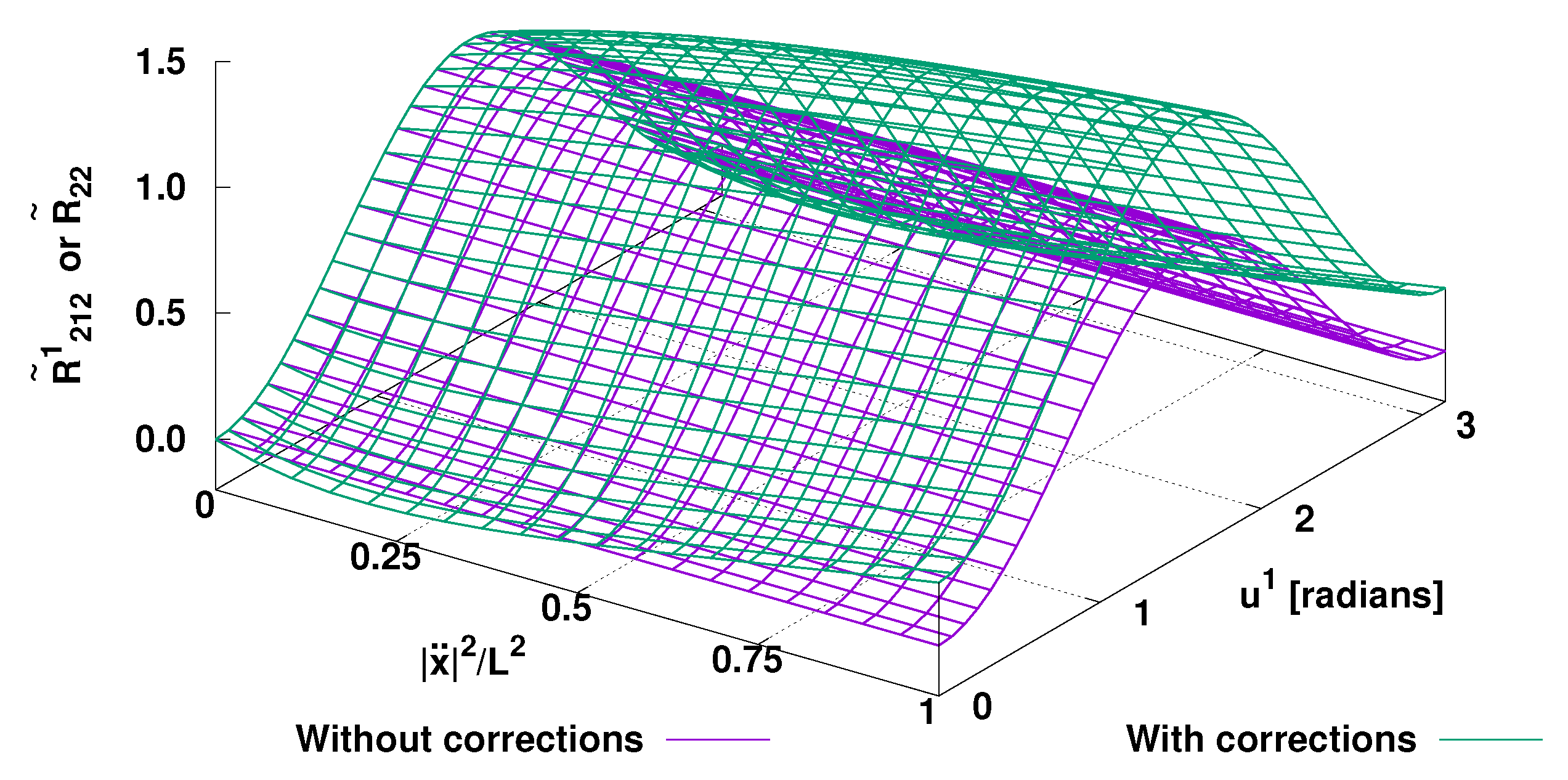

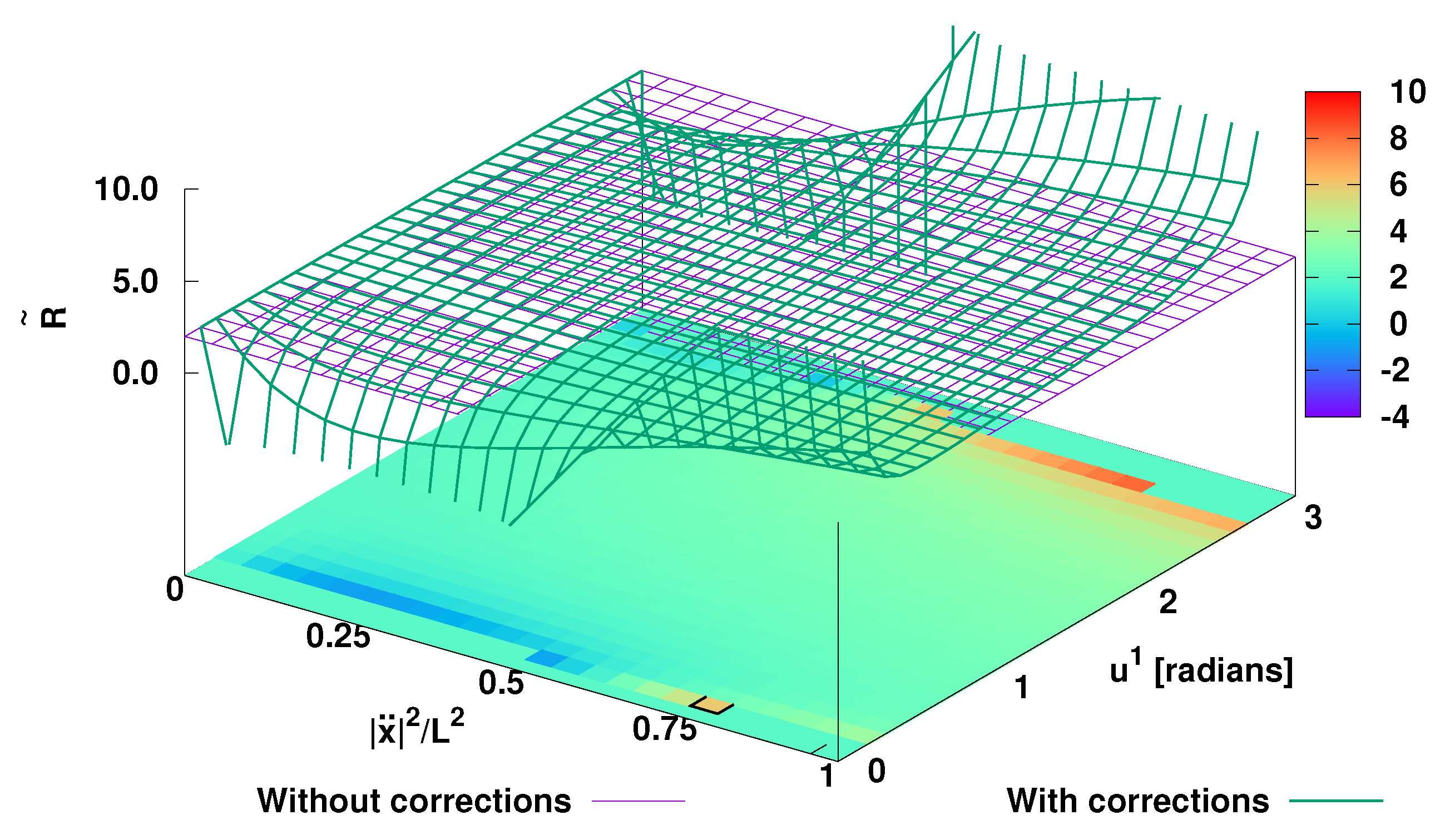

Figure 1 shows the coefficients of Riemann and Ricci curvature tensors in a sphere surface (two-dimensional manifold) with radius

, Eq. (

38). For the sake of simplicity, we assume that the squared spacelike acceleration

is given in units of

. This assures correct dimensions and sets upper bound on

in units of

.

The

Figure 1 depicts the dependence of

and

on both

and

. It is apparent that the minimal length contributions are significant everywhere. It seems that the second term in Eq. (

38), which is the same for Riemann and Ricci tensors, reveal additional geometrical structures and curvatures. Their nature shall be subject of a future study.

7. Deformed Einstein tensor

The Einstein tensor is constructed as

and the deformed Einstein tensor will be

By substituting

,

, and

as given in Eqs. (

41), (

15), and (

44), respectively, into Eq. (

47), we get

where the indices

and

of Ricci scalar have replaced by dummy indices

and

, respectively, and take

as a common factor,

where

, take

and

as common factors,

At , the undeformed is obviously fully retrieved from Eq. (50). At finite , the resulting spacetime curvature seems to have more structures than that of the Einstein’s classical tensor . Accordingly, additional sources of gravity are likely emerging. Their nature shall be characterized elsewhere.

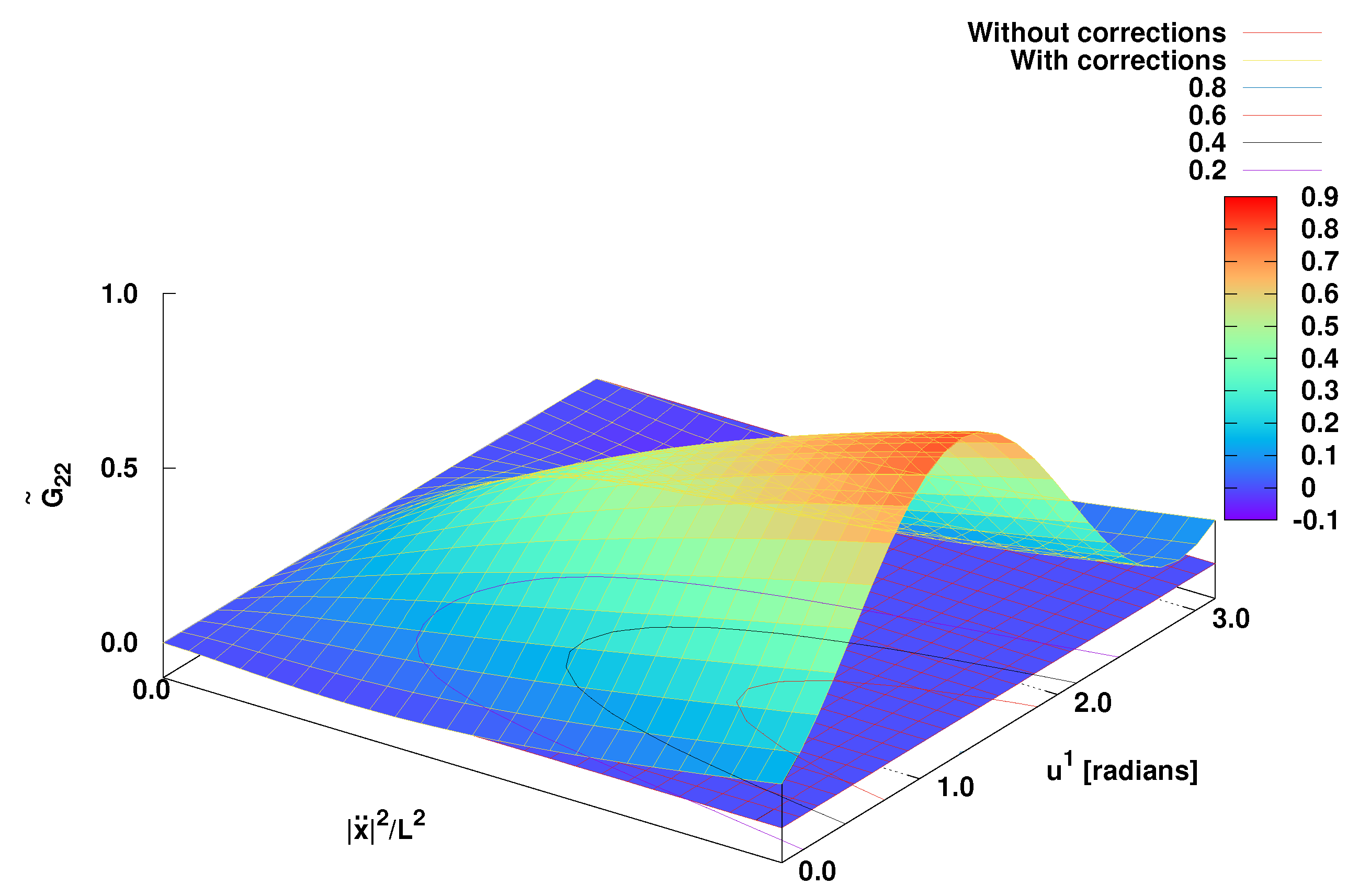

For a sphere surface (two-dimensional manifold) with radius

, Eq. (50) gives

Accordingly, a comparison between

and

is depicted in

Figure 3. a sphere surface with radius

.

In freely falling frames, in which the covariant derivative of tensor is the same for all observers, and the affine connection is vanishing so that the covariant derivative of deformed Einstein tensor Eq. (50) will be

where

in general relativity. In the flat space-time, the covariant derivative is a partial derivative, then Eq. (

54) becomes

where

see

Appendix A. In free falling frame,

, then

where

. Eq. (

59) is valid for flat or curved space-time therefore, the divergence of deformed Einstein tensor is vanishing.

The central assumption of general relativity is that the divergence of vanishes as that of the energy–momentum tensor , that is and . This means that extending the spacetime curvature preserves the central assumption of GR.