Submitted:

06 June 2023

Posted:

06 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Minimal Measurable Length

3. The Deformation of Metric Tensor

4. The Deformation of Affine Connection in Riemannian Manifold

-

For curved space,With Eq. (5), the can be suggested as GUP contributed part, which reads

- For flat space,where .

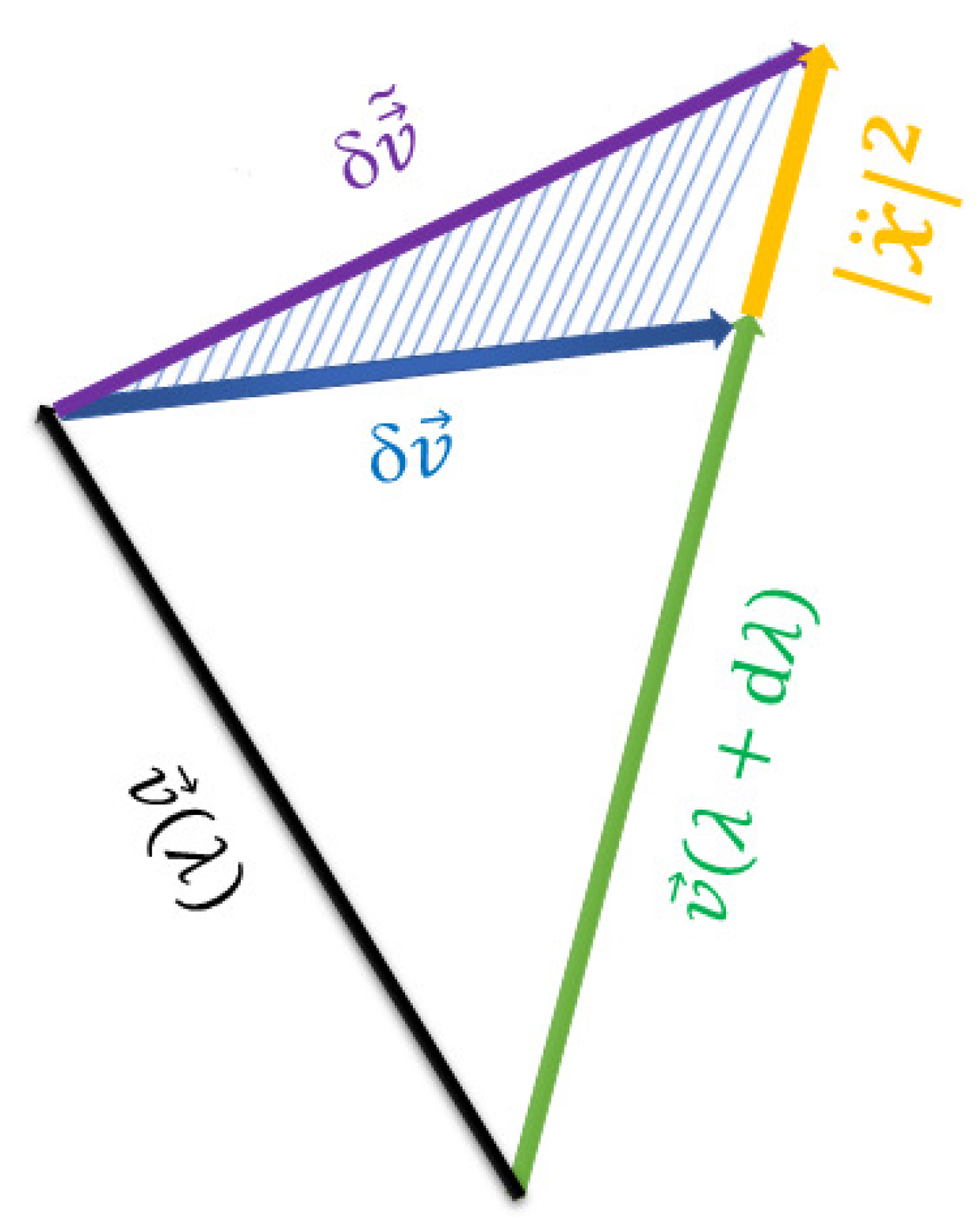

5. Parallel Transport on Riemannian Manifold

6. Symmetry Properties of Deformed Affine Connection

- In any coordinates, the deformed affine connection can be expressed in the deformed metric tensor and its derivatives,where the deformed metric tensor is symmetric, then the deformed affine connection is symmetric, as well.

- The affine connection can be expressed as [34]where and represent different coordinates in curved space, the commutation of the partial derivatives is still satisfied in the deformed affine connection, Eq. (28). This is also valid even when is deformed to encounter the existence of a minimal length uncertainty.

7. Summary and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Appendix A Differential geometry and affine connection

Appendix B The metric tensor compatibility

References

- Isham, C.J. Prima facie questions in quantum gravity. Canonical Gravity: From Classical to Quantum: Proceedings of the 117th WE Heraeus Seminar Held at Bad Honnef, Germany, . Springer, 2005, pp. 1–21. 13–17 September.

- Bosso, P. On the quasi-position representation in theories with a minimal length. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2021, 38, 075021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosso, P.; Obregón, O. Minimal length effects on quantum cosmology and quantum black hole models. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2020, 37, 045003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S.; Lambiase, G.; Scarpetta, G. Generalized uncertainty principle from quantum geometry. arXiv preprint gr-qc/9910017 1999.

- Adler, R.J.; Santiago, D.I. On gravity and the uncertainty principle. Modern Physics Letters A 1999, 14, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardigli, F. Generalized uncertainty principle in quantum gravity from micro-black hole gedanken experiment. Physics Letters B 1999, 452, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempf, A.; Mangano, G.; Mann, R.B. Hilbert space representation of the minimal length uncertainty relation. Physical Review D 1995, 52, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggiore, M. A generalized uncertainty principle in quantum gravity. Physics Letters B 1993, 304, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, K.; Paffuti, G.; Provero, P. Minimum physical length and the generalized uncertainty principle in string theory. Physics Letters B 1990, 234, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolyhazy, F. Gravitation and quantum mechanics of macroscopic objects. Il Nuovo Cimento A (1965-1970) 1966, 42, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, C.A. Possible connection between gravitation and fundamental length. Physical Review 1964, 135, B849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.N. On quantized space-time. Physical Review 1947, 72, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H.S. Quantized space-time. Physical Review 1947, 71, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridakis, E.; Lazkoz, R.; Salzano, V.; Moniz, P.; Capozziello, S.; Jiménez, J.; De Laurentis, M.; Olmo, G. Modified Gravity and Cosmology: An Update by the CANTATA Network; Springer International Publishing, 2021.

- Farag Ali, A.; Das, S.; Vagenas, E.C. The generalized uncertainty principle and quantum gravity phenomenology. The Twelfth Marcel Grossmann Meeting: On Recent Developments in Theoretical and Experimental General Relativity, Astrophysics and Relativistic Field Theories (In 3 Volumes). World Scientific, 2012, pp. 2407–2409.

- Bosso, P. Generalized uncertainty principle and quantum gravity phenomenology; University of Lethbridge (Canada), 2017.

- Garay, L.J. Quantum gravity and minimum length. International Journal of Modern Physics A 1995, 10, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A.; Diab, A. Generalized uncertainty principle: Approaches and applications. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2014, 23, 1430025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempf, A. Uncertainty relation in quantum mechanics with quantum group symmetry. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1994, 35, 4483–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A.N.; Diab, A.M. A review of the generalized uncertainty principle. Reports on Progress in Physics 2015, 78, 126001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A.N.; Diab, A.M.; Shenawy, S.; El Dahab, E.A. Consequences of minimal length discretization on line element, metric tensor, and geodesic equation. Astronomische Nachrichten 2021, 342, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A.N.; Farouk, F.T.; Tarabia, F.S.; Maher, M. Minimal length discretization and properties of modified metric tensor and geodesics, The Sixteenth Marcel Grossmann Meeting. In The Sixteenth Marcel Grossmann Meeting; pp. 4074–4081. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P.; Adhikari, R.; Adya, V.B.; others. GW170817: observation of gravitational waves from a binary neutron star inspiral. Physical review letters 2017, 119, 161101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diab, A.M.; Tawfik, A.N. A possible solution of the cosmological constant problem based on minimal length uncertainty and GW170817 and PLANCK Observations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.03999 2020.

- Sprenger, M.; Nicolini, P.; Bleicher, M. Physics on the smallest scales: an introduction to minimal length phenomenology. European Journal of Physics 2012, 33, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, H. Erratum to: Maximal proper acceleration relative to the vacuum. Lettere al Nuovo Cimento (1971-1985) 1984, 39, 192–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caianiello, E.R.; Feoli, A.; Gasperini, M.; Scarpetta, G. Quantum corrections to the spacetime metric from geometric phase space quantization. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1990, 29, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caianiello, E.R.; Gasperini, M.; Scarpetta, G. Phenomenological consequences of a geometric model with limited proper acceleration. Il Nuovo Cimento B (1971-1996) 1990, 105, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cainiello, E.; Gasperini, M.; Scarpetta, G. Inflation and singularity prevention in a model for extended-object-dominated cosmology. Classical and Quantum Gravity 1991, 8, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, H.E. Maximal proper acceleration and the structure of spacetime. Foundations of Physics Letters 1989, 2, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, H.E. Riemann curvature scalar of spacetime tangent bundle. Foundations of Physics Letters 1992, 5, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, B. A first course in general relativity; Cambridge university press, 2009.

- Emam, M.H. Covariant Physics: From Classical Mechanics to General Relativity and Beyond; Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Neuenschwander, D.E. Tensor calculus for physics; John Hopkins University Press, 2014.

- Sundermeyer, K. Symmetries in fundamental physics; Vol. 176, Springer, 2014.

- Carroll, S.M. An introduction to general relativity: spacetime and geometry. Addison Wesley 2004, 101, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Misner, C.W.; Thorne, K.S.; Wheeler, J.A. Gravitation; Macmillan, 1973.

- Cabral, F.; Lobo, F.S.; Rubiera-Garcia, D. Einstein–Cartan–Dirac gravity with U (1) symmetry breaking. The European Physical Journal C 2019, 79, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Other assumptions, i.e., nonsymmetric energy–momentum tensor or finite torque density, are also possible, e.g., Einstein–Cartan–Sciama–Kibble theory [38] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).