Submitted:

06 June 2023

Posted:

07 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Can the transmission of COVID-19 and other viral agents be explained by a specific climate factor given by high air humidity?

- Does the interaction of climate parameters contribute to the accelerate diffusion of COVID-19?

2.1. Sample and data

2.2. Measures of variables

- COVID-19 confirmed cases: Number of infected individuals from February 08, 2021 to May 03, 2021, based on people that are positive for COVID-19 test.

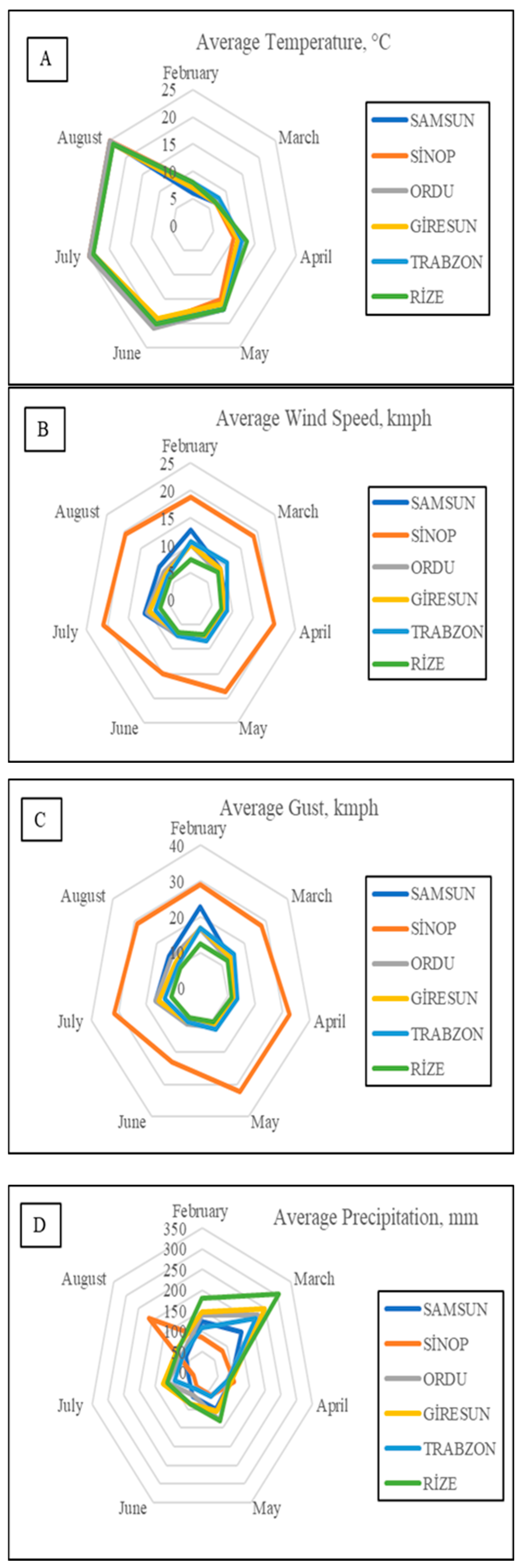

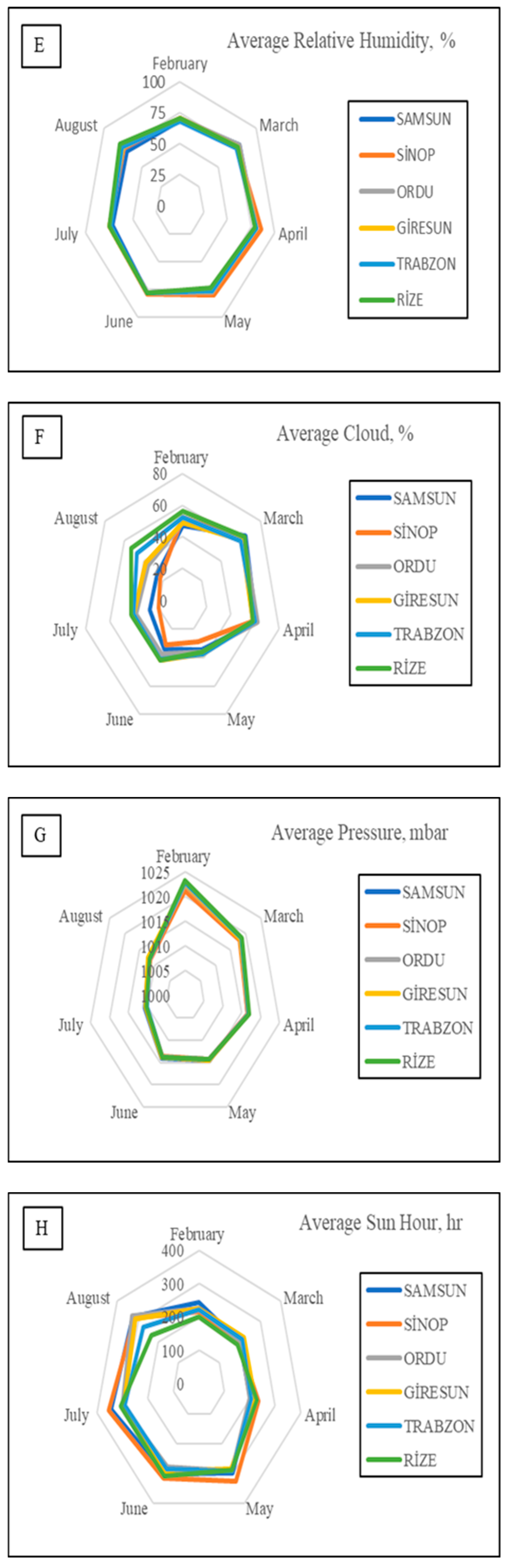

- Meteorological parameters: Average ambient temperature in °C, average wind speed in kmph, average gust in kmph, average precipitation in mm, average relative humidity %, average cloud %, average atmospheric pressure in mbar, and average sun hour from February 08, 2021 to September 03, 2021.

2.3. Data analysis procedure

3. Results

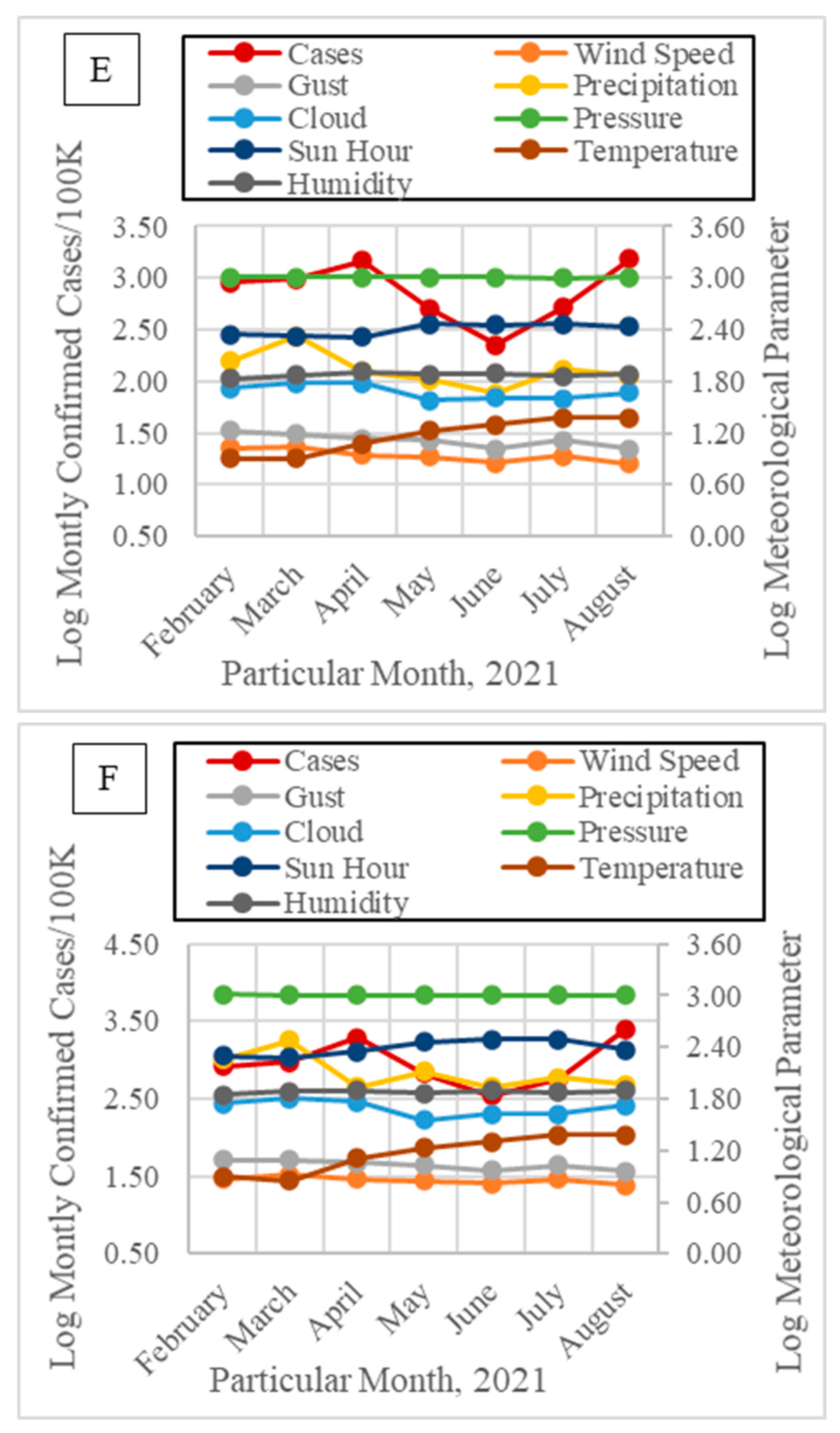

3.1. Overview of the climate in the Turkish Black Sea region

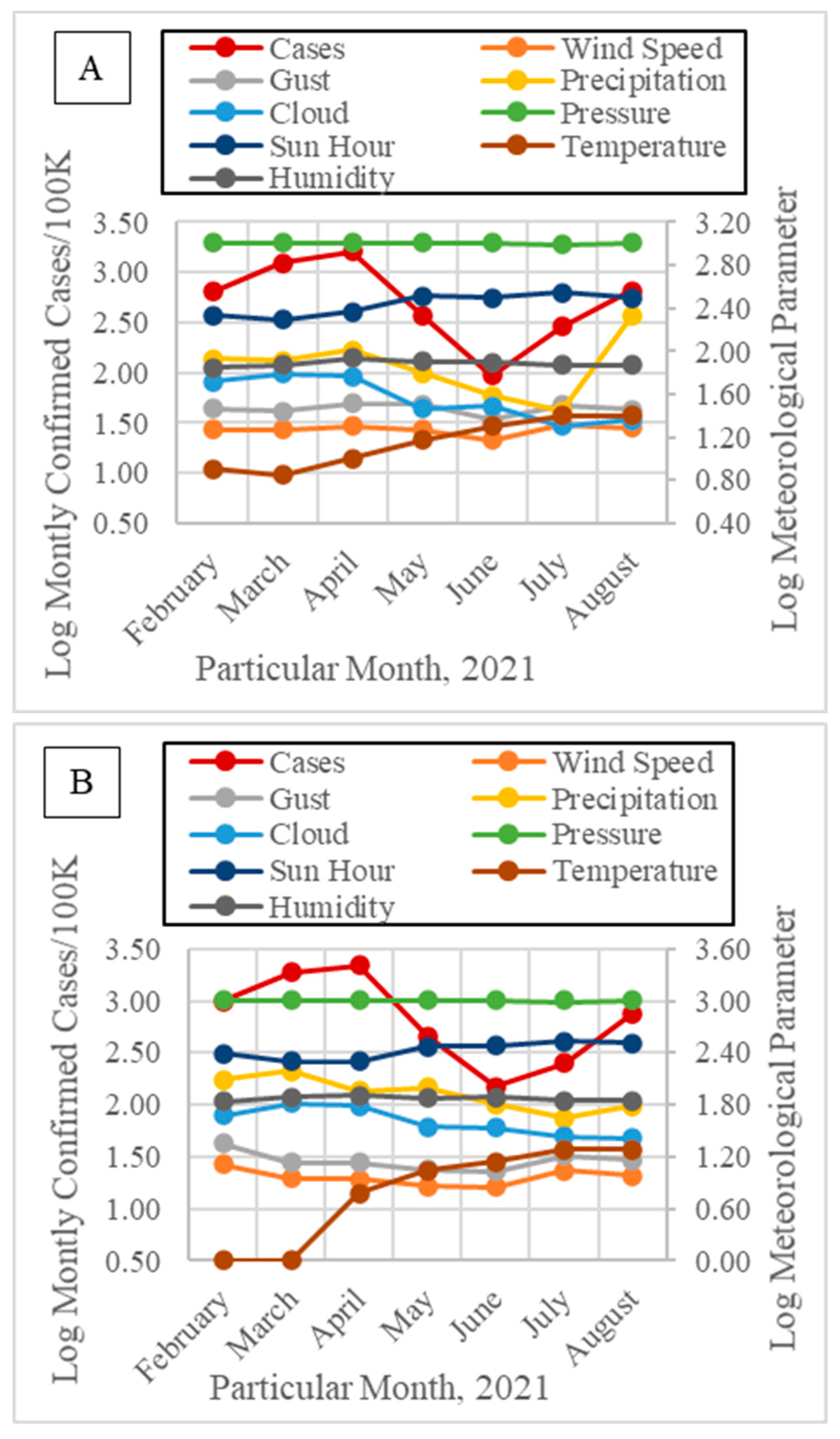

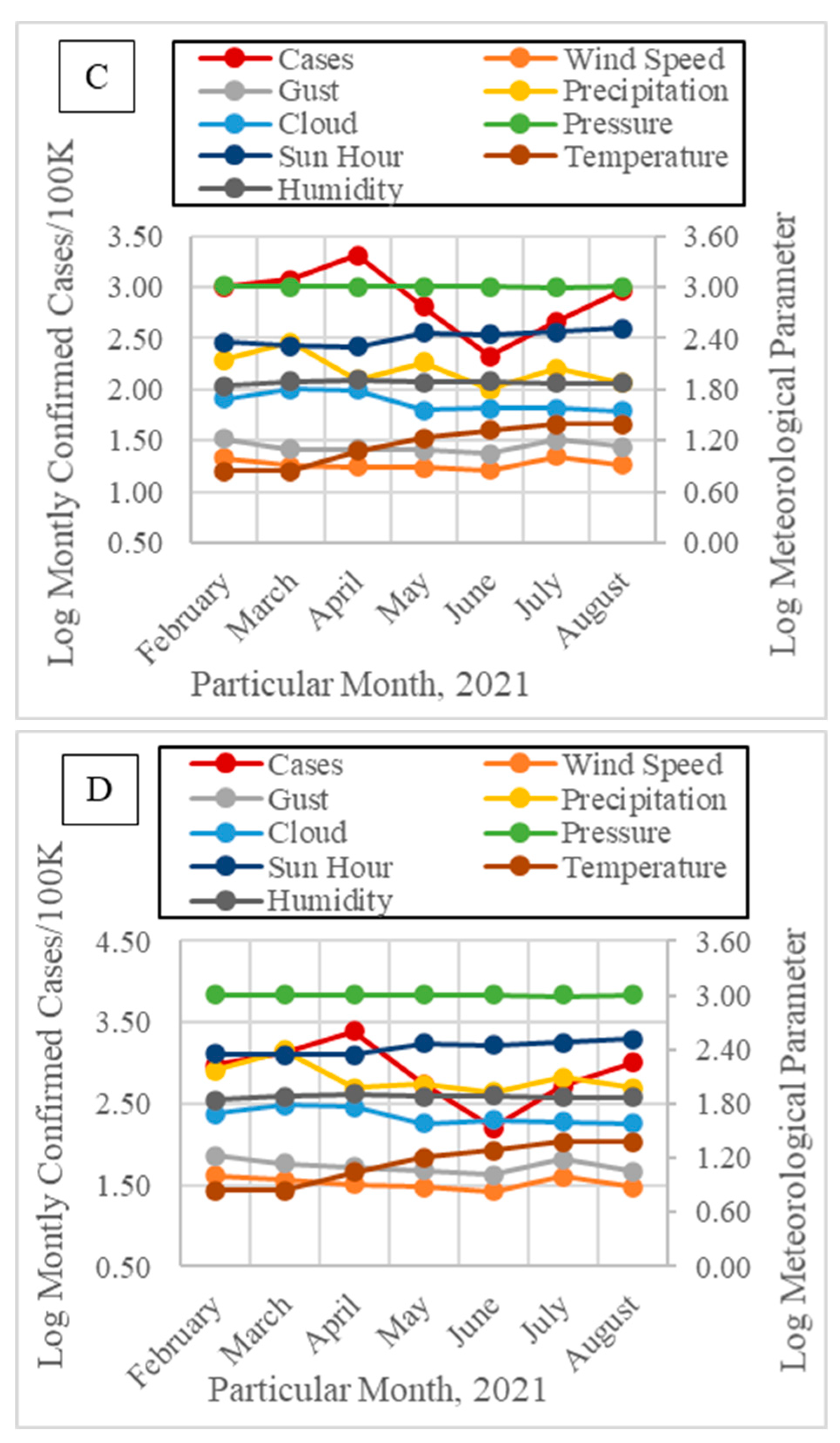

3.2. Relations between COVID-19 confirmed cases and climate factors in the Turkish Black Sea region

4. Discussions

| SAMSUN city | ||||||||

| Kendall’s Correlation Coefficients, rk | ||||||||

| Temperature | Wind Speed | Gust | Precipitation | Relative Humidity | Cloud | Pressure | Sun Hour | |

| Temperature | 1.00 | -0.19 | -0.195 | -0.78* | -0.15 | -0.78* | -0.98** | 0.78* |

| Wind Speed | -0.19 | 1.00 | 1.00** | -0.05 | -0.59 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| Gust | -0.19 | 1.00** | 1.00 | -0.05 | -0.59 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| Precipitation | -0.78* | -0.05 | -0.05 | 1.00 | 0.09 | 0.71* | 0.81* | -0.81* |

| Relative Humidity | -0.15 | -0.59 | -0.59 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.09 | -0.29 |

| Cloud | -0.78* | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.71* | 0.39 | 1.00 | 0.71* | -0.91** |

| Pressure | -0.98** | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.81* | 0.09 | 0.71* | 1.00 | -0.81* |

| Sun Hour | 0.78* | 0.05 | 0.05 | -0.81 | -0.29 | -0.91** | -0.81* | 1.00 |

| Spearman’s Correlation Coefficients, rs | ||||||||

| Temperature | Wind Speed | Gust | Precipitation | Relative Humidity | Cloud | Pressure | Sun Hour | |

| Temperature | 1.00 | -0.13 | -0.13 | -0.92** | -0.11 | -0.88** | -0.99** | 0.88** |

| Wind Speed | -0.13 | 1.00 | 1.00** | -0.04 | -0.74 | -0.11 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| Gust | -0.13 | 1.00** | 1.00 | -0.04 | -0.74 | -0.11 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| Precipitation | -0.92** | -0.04 | -0.04 | 1.00 | 0.14 | 0.86* | 0.93** | -0.89** |

| Relative Humidity | -0.11 | -0.74 | -0.74 | 0.14 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.09 | -0.29 |

| Cloud | -0.88** | -0.11 | -0.11 | 0.86* | 0.39 | 1.00 | ||

| Pressure | -0.99** | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.93** | 0.09 | 0.86* | 1.00 | -0.89** |

| Sun Hour | 0.88** | 0.14 | 0.14 | -0.89** | -0.29 | -0.96** | -0.89** | 1.00 |

| SİNOP city | ||||||||

| Kendall’s Correlation Coefficients, rk | ||||||||

| Temperature | Wind Speed | Gust | Precipitation | Relative Humidity | Cloud | Pressure | Sun Hour | |

| Temperature | 1.00 | 0.25 | 1.00 | -0.19 | -0.15 | -0.78* | -0.88* | 0.78* |

| Wind Speed | 0.25 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.29 | -0.05 | -0.29 | -0.19 | 0.29 |

| Gust | 1.00 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 0.14 | 0.29 | -0.05 | 0.05 | 0.24 |

| Precipitation | -0.19 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 1.00 | -0.09 | 0.24 | 0.33 | -0.24 |

| Relative Humidity | -0.15 | -0.05 | 0.29 | -0.09 | 1.00 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.09 |

| Cloud | -0.78* | -0.29 | -0.05 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.71* | -0.81* |

| Pressure | -0.88** | -0.19 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.71* | 1.00 | -0.71* |

| Sun Hour | 0.78* | 0.29 | 0.24 | -0.24 | -0.24 | 0.09 | -0.81* | 1.00 |

| Spearman’s Correlation Coefficients, rs | ||||||||

| Temperature | Wind Speed | Gust | Precipitation | Relative Humidity | Cloud | Pressure | Sun Hour | |

| Temperature | 1.00 | 0.35 | 1.00 | -0.22 | -0.03 | -0.92** | -0.96** | 0.87* |

| Wind Speed | 0.35 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 0.19 | -0.10 | -0.36 | -0.32 | 0.34 |

| Gust | 1.00 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 0.14 | 0.45 | -0.11 | 0.04 | 0.32 |

| Precipitation | -0.22 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 1.00 | -0.19 | 0.32 | 0.36 | -0.43 |

| Relative Humidity | -0.03 | -0.10 | 0.45 | -0.19 | 1.00 | 0.18 | 1.00 | 0.18 |

| Cloud | -0.92** | -0.36 | -0.11 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 1.00 | 0.86 | -0.93** |

| Pressure | -0.96** | -0.32 | 0.04 | 0.36 | 1.00 | 0.86* | 1.00 | -0.86 |

| Sun Hour | 0.86* | 0.34 | 0.32 | -0.43 | -0.43 | 0.18 | -0.93** | 1.00 |

| ORDU city | ||||||||

| Kendall’s Correlation Coefficients, rk | ||||||||

| Temperature | Wind Speed | Gust | Precipitation | Relative Humidity | Cloud | Pressure | Sun Hour | |

| Temperature | 1.00 | -0.05 | -0.10 | -0.55 | -0.21 | -0.62 | -0.95** | -0.65* |

| Wind Speed | -0.05 | 1.00 | 0.88** | 0.24 | -0.55 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.24 |

| Gust | -0.10 | 0.88** | 1.00 | 0.29 | -0.62 | 1.00 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Precipitation | -0.55 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 1.00 | -0.15 | 0.39 | 0.43 | -0.33 |

| Relative Humidity | -0.21 | -0.55 | -0.62 | -0.15 | 1.00 | 0.31 | 0.15 | -0.55 |

| Cloud | -0.62 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 0.49 | -0.78* |

| Pressure | -0.95** | 0.048 | 0.098 | 0.43 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 1.00 | -0.52 |

| Sun Hour | -0.65* | 0.24 | 0.09 | -0.33 | -0.55 | -0.78* | -0.52 | 1.00 |

| Spearman’s Correlation Coefficients, rs | ||||||||

| Temperature | Wind Speed | Gust | Precipitation | Relative Humidity | Cloud | Pressure | Sun Hour | |

| Temperature | 1.00 | 0.11 | -0.05 | -0.71 | -0.19 | -0.78* | -0.98** | 0.84* |

| Wind Speed | 0.11 | 1.00 | 0.96** | 0.36 | -0.71 | 0.04 | -0.11 | 0.29 |

| Gust | -0.05 | 0.96** | 1.00 | 0.36 | -0.74 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

| Precipitation | -0.71 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 1.00 | -0.22 | 0.52 | 0.64 | -0.36 |

| Relative Humidity | -0.19 | -0.71 | -0.74 | -0.22 | 1.00 | 0.44 | 0.11 | -0.60 |

| Cloud | -0.78* | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 0.69 | -0.90** |

| Pressure | -0.98** | -0.11 | 0.09 | 0.64 | 0.11 | 0.69 | 1.00 | -0.79* |

| Sun Hour | 0.84* | 0.29 | 0.16 | -0.36 | -0.60 | -0.90** | -0.79* | 1.00 |

| GİRESUN city | ||||||||

| Kendall’s Correlation Coefficients, rk | ||||||||

| Temperature | Wind Speed | Gust | Precipitation | Relative Humidity | Cloud | Pressure | Sun Hour | |

| Temperature | 1.00 | -0.41 | -0.45 | -0.35 | -0.11 | -0.62 | -0.95** | 0.65* |

| Wind Speed | -0.41 | 1.00 | 0.98** | 0.59 | -0.51 | 0.30 | 0.39 | -0.09 |

| Gust | -0.45 | 0.98** | 1.00 | 0.62 | -0.45 | 0.29 | 0.43 | -0.14 |

| Precipitation | -0.35 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 1.00 | -0.45 | 0.29 | 0.24 | -0.14 |

| Relative Humidity | -0.11 | -0.51 | -0.45 | -0.45 | 1.00 | 0.21 | 0.05 | -0.45 |

| Cloud | -0.62 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 1.00 | 0.49 | -0.78* |

| Pressure | -0.95** | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.49 | 1.00 | -0.52 |

| Sun Hour | 0.65* | -0.09 | -0.14 | -0.14 | -0.45 | -0.78* | -0.52 | 1.00 |

| Spearman’s Correlation Coefficients, rs | ||||||||

| Temperature | Wind Speed | Gust | Precipitation | Relative Humidity | Cloud | Pressure | Sun Hour | |

| Temperature | 1.00 | -0.43 | -0.47 | -0.49 | -0.08 | -0.76* | -0.98** | 0.84* |

| Wind Speed | -0.43 | 1.00 | 0.99** | 0.78* | -0.59 | 0.42 | 0.40 | -0.25 |

| Gust | -0.47 | 0.99** | 1.00 | 0.79* | -0.55 | 0.41 | 0.43 | -0.29 |

| Precipitation | -0.49 | 0.78* | 0.79* | 1.00 | -0.60 | 0.31 | 0.43 | -0.11 |

| Relative Humidity | -0.08 | -0.59 | -0.55 | -0.60 | 1.00 | 0.31 | 0.02 | -0.51 |

| Cloud | -0.76* | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 0.69 | -0.90* |

| Pressure | -0.98** | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 1.00 | -0.79* |

| Sun Hour | 0.84* | -0.25 | -0.29 | -0.11 | -0.51 | -0.90* | -0.79* | 1.00 |

| TRABZON city | ||||||||

| Kendall’s Correlation Coefficients, rk | ||||||||

| Temperature | Wind Speed | Gust | Precipitation | Relative Humidity | Cloud | Pressure | Sun Hour | |

| Temperature | 1.00 | -0.75* | -0.75* | -0.45 | 0.10 | -0.41 | -0.95* | 0.45 |

| Wind Speed | -0.75* | 1.00 | 0.91** | 0.71* | -0.29 | 0.39 | 0.62 | -0.24 |

| Gust | -0.75* | 0.91** | 1.00 | 0.62 | -0.39 | 0.29 | 0.71* | -0.14 |

| Precipitation | -0.45 | 0.71* | 0.62 | 1.00 | -0.49 | 0.49 | 0.33 | -0.33 |

| Relative Humidity | 0.10 | -0.29 | -0.39 | -0.49 | 1.00 | 0.05 | -0.09 | -0.19 |

| Cloud | -0.41 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.49 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.39 | -0.88** |

| Pressure | -0.95** | 0.62 | 0.71* | 0.33 | -0.09 | 0.39 | 1.00 | -0.43 |

| Sun Hour | 0.45 | -0.24 | -0.14 | -0.33 | -0.19 | -0.88** | -0.43 | 1.00 |

| Spearman’s Correlation Coefficients, rs | ||||||||

| Temperature | Wind Speed | Gust | Precipitation | Relative Humidity | Cloud | Pressure | Sun Hour | |

| Temperature | 1.00 | -0.84* | -0.83* | -0.56 | 0.19 | -0.63 | -0.98** | 0.69 |

| Wind Speed | -0.84* | 1.00 | 0.96** | 0.86* | -0.43 | 0.61 | 0.75 | -0.54 |

| Gust | -0.84* | 0.96** | 1.00 | 0.82* | -0.51 | 0.56 | 0.79* | -0.50 |

| Precipitation | -0.56 | 0.86* | 0.82* | 1.00 | -0.67 | 0.59 | 0.50 | -0.43 |

| Relative Humidity | 0.19 | -0.43 | -0.51 | -0.67 | 1.00 | 0.09 | -0.18 | -0.25 |

| Cloud | -0.63 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.63 | -0.96** |

| Pressure | -0.98** | 0.75 | 0.79* | 0.50 | -0.18 | 0.63 | 1.00 | -0.71 |

| Sun Hour | 0.69 | -0.54 | -0.50 | -0.43 | -0.25 | -0.96** | -0.71 | 1.00 |

| RİZE city | ||||||||

| Kendall’s Correlation Coefficients, rk | ||||||||

| Temperature | Wind Speed | Gust | Precipitation | Relative Humidity | Cloud | Pressure | Sun Hour | |

| Temperature | 1.00 | -0.65* | -0.75* | -0.45 | 0.25 | -0.45 | -0.68* | 0.68* |

| Wind Speed | -0.65* | 1.00 | 0.85** | 0.35 | -0.15 | 0.55 | 0.29 | -0.49 |

| Gust | -0.75* | 0.85** | 1.00 | 0.45 | -0.35 | 0.45 | 0.49 | -0.59 |

| Precipitation | -0.45 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 1.00 | -0.55 | 0.15 | 0.09 | -0.49 |

| Relative Humidity | 0.25 | -0.15 | -0.35 | -0.55 | 1.00 | 0.25 | -0.29 | 0.09 |

| Cloud | -0.45 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 0.19 | -0.68* |

| Pressure | -0.68* | 0.29 | 0.49 | 0.09 | -0.29 | 0.19 | 1.00 | -0.43 |

| Sun Hour | 0.68* | -0.49 | -0.59 | -0.49 | 0.09 | -0.68* | -0.43 | 1.00 |

| Spearman’s Correlation Coefficients, rs | ||||||||

| Temperature | Wind Speed | Gust | Precipitation | Relative Humidity | Cloud | Pressure | Sun Hour | |

| Temperature | 1.00 | -0.74* | -0.84* | -0.56 | 0.30 | -0.66 | -0.78* | 0.79* |

| Wind Speed | -0.74* | 1.00 | 0.90** | 0.44 | -0.16 | 0.68 | 0.39 | -0.65 |

| Gust | -0.84* | 0.90** | 1.00 | 0.61 | -0.46 | 0.66 | 0.60 | -0.74 |

| Precipitation | -0.56 | 0.44 | 0.61 | 1.00 | -0.70 | 0.24 | 0.23 | -0.61 |

| Relative Humidity | 0.30 | -0.16 | -0.46 | -0.70 | 1.00 | 0.29 | -0.32 | 0.09 |

| Cloud | -0.66 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 1.00 | 0.36 | -0.85* |

| Pressure | -0.78* | 0.39 | 0.60 | 0.23 | -0.32 | 0.36 | 1.00 | -0.57 |

| Sun Hour | 0.79* | -0.65 | -0.74 | -0.61 | 0.09 | -0.85* | -0.57 | 1.00 |

5. Conclusions and limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akan, A.P. 2022. Transmission of COVID-19 pandemic (Turkey) associated with short-term exposure of air quality and climatological parameters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. [CrossRef]

- Akan, A.P.; Coccia, M. 2022. Changes of Air Pollution between Countries Because of Lockdowns to Face COVID-19 Pandemic. Applied Sciences 12, no. 24: 12806. [CrossRef]

- Aral, N., Bakır, H., 2022. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Covid-19 in Turkey. Sustain. Cities Soc. 76:103421. [CrossRef]

- Aykaç, N., Etiler, N., 2021. COVID-19 mortality in Istanbul in association with air pollution and socioeconomic status: an ecological study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M. F., Ma, B., Bilal, Komal, B., Bashir, M.A., Tan, D., Bashir, M., 2020. Correlation between climate indicators and COVID-19 pandemic in New York, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 728:138835. [CrossRef]

- Bolaño-Ortiz, T. R., Camargo-Caicedo, Y., Puliafito, S. E., Ruggeri, M.F., Bolaño-Diaz, S., Pascual-Flores, R., Saturno, J., Ibarra-Espinosa, S., Mayol-Bracero, O.L., Torres-Delgado, E., Cereceda-Balic, F., 2020. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 through Latin America and the Caribbean region: A look from its economic conditions, climate and the air pollution indicators. Environ. Res. 191:109938. [CrossRef]

- Benati I.,Coccia M. 2022. Global analysis of timely COVID-19 vaccinations: improving governance to reinforce response policies for pandemic crises. International Journal of Health Governance, vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 240-253. [CrossRef]

- Benati I.,Coccia M. 2022a. Effective Contact Tracing System Minimizes COVID-19 Related Infections and Deaths: Policy Lessons to Reduce the Impact of Future Pandemic Diseases. Journal of Public Administration and Governance, vol. 12, n. 3, pp. 19-33. https://doi.org/.

- Bontempi E., Coccia M., 2021. International trade as critical parameter of COVID-19 spread that outclasses demographic, economic, environmental, and pollution factors, Environmental Research, vol. 201, number 111514. [CrossRef]

- Bontempi E., Coccia M., Vergalli S., Zanoletti A. 2021. Can commercial trade represent the main indicator of the COVID-19 diffusion due to human-to-human interactions? A comparative analysis between Italy, France, and Spain, Environmental Research, vol. 201, Article number 111529. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.C., Lu, J., Xu, Q.F., Guo, Q., Xu, D.Z., Sun, Q.W., Yang, H., Zhao, G.M., Jiang, Q.W., 2007. Influence of meteorological factors and air pollution on the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Public Health. 121:258-265. https://doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2006.09.023.

- Caliskan, B, Özengin N, Cindoruk SS (2020) Air quality level, emission sources and control strategies in Bursa/Turkey. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 11:2182-2189. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2020. Effects of Air Pollution on COVID-19 and Public Health, Research Article-Environmental Economics-Environmental Policy, ResearchSquare,. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-41354/v1.

- Coccia, M., 2020a. An index to quantify environmental risk of exposure to future epidemics of the COVID-19 and similar viral agents: Theory and practice. Environ. Res. 191:110155. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2021. Recurring waves of Covid-19 pandemic with different effects in public health, Journal of Economics Bibliography - J. Econ. Bib. – JEB, vol. 8, n. 1, pp. 28-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1453/jeb.v8i1.2184.

- Coccia, M. 2021a. Pandemic Prevention: Lessons from COVID-19. Encyclopedia, vol. 1, n. 2, pp. 433-444. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M., 2021b. The effects of atmospheric stability with low wind speed and of air pollution on the accelerated transmission dynamics of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 78(1):1-27. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M., 2021c. How do low wind speeds and high levels of air pollution support the spread of COVID-19? Atmos. Pol. Res. 12:437-445. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M., 2021d. Effects of the spread of COVID-19 on public health of polluted cities: results of the first wave for explaining the dejà vu in the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic and epidemics of future vital agents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28:19147–19154. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M., 2021e. Comparative Critical Decisions in Management. In: Farazmand A. (eds), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer Nature, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M., 2021f. The relation between length of lockdown, numbers of infected people and deaths of Covid-19, and economic growth of countries: Lessons learned to cope with future pandemics similar to Covid-19 and to constrain the deterioration of economic system. Sci. Total Environ. 775:145801. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M., 2021g. Pandemic Prevention: Lessons from COVID-19. Encyclopedia. 1:433-444. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2022. Optimal levels of vaccination to reduce COVID-19 infected individuals and deaths: A global analysis. Environmental Research, vol. 204, Part C, March 2022, Article number 112314. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2022a. The Spread of the Novel Coronavirus Disease-2019 in Polluted Cities: Environmental and Demographic Factors to Control for the Prevention of Future Pandemic Diseases. In: Faghih, N., Forouharfar, A. (eds) Socioeconomic Dynamics of the COVID-19 Crisis. Contributions to Economics: 351-369. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M., 2022b. Preparedness of countries to face COVID-19 pandemic crisis: Strategic positioning and factors supporting effective strategies of prevention of pandemic threats. Environ. Res. 203:111678. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2022c. COVID-19 pandemic over 2020 (with lockdowns) and 2021 (with vaccinations): similar effects for seasonality and environmental factors. Environmental Research, vol. 208, n. 112711. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2023. Effects of strict containment policies on COVID-19 pandemic crisis: lessons to cope with next pandemic impacts. Environmental science and pollution research international, 30(1), 2020–2028. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2023a. High potential of technology to face new respiratory viruses: mechanical ventilation devices for effective healthcare to next pandemic emergencies, Technology in Society, vol. 73, May 2023, n. 102233. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2023b. Sources, diffusion and prediction in COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned to face next health emergency[J]. AIMS Public Health, 2023, 10(1): 145-168. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2023012. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Benati I. 2018. Comparative Evaluation Systems, A. Farazmand (ed.), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- COP26, 2021. 26th Conference of Parties, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/conference/glasgow-climate-change-conference-october-november-2021 (accessed: December 2021).

- Coşkun, H., Yıldırım, N., Gündüz, S., 2021. The spread of COVID-19 virus through population density and wind in Turkey cities. Sci. Total Environ. 751:141663. [CrossRef]

- COVID-19, 2021. Information about COVID-19 cases from the Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health. https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/?_Dil=2 (accessed: September 2021).

- Doğan, B., Jebli, M. B., Shahzad, K. Farooq, T. H., Shahzad, U., 2020. Investigating the Effects of Meteorological Parameters on COVID-19: Case Study of New Jersey, United States. Environ. Res. 191:110148. [CrossRef]

- Domingo, J.L., Marquès, M., Rovira, J., 2020. Influence of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on COVID-19 pandemic. A review. Environ. Res.188:109861. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C., Bo, Y., Lin, C., Li, H. B., Zeng, Y., Zhang, Y., Hossain, M. S., Chan, J. W. M., Yeung, D. W., Kwok, K.-on, Wong, S. Y. S., Lau, A. K. H., Lao, X. Q., 2021. Meteorological factors and COVID-19 incidence in 190 countries: An observational study. Sci. Total Environ. 757:143783. [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.E., Rahman, M., 2020. Association between temperature, humidity, and COVID-19 outbreaks in Bangladesh. Environ Sci Policy. 114:253-255. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T., Tran, T. T. A., 2021. Ambient air pollution, meteorology, and COVID-19 infection in Korea. J. Med. Virol. 93:878–885. [CrossRef]

- Iha, Y., Kinjo, T., Parrott, G., Higa, F., Mori, H., Fujita, J., 2016. Comparative epidemiology of influenza A and B viral infection in a subtropical region: a 7-year surveillance in Okinawa, Japan. BMC Infect. Dis.16(1), 650:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Islam, A. R. Md. T., Hasanuzzaman, Md., Azad, Md. A. K., Salam, R., Toshi, F. Z., Khan, Md. S. I., Alam, G. M. M., Ibrahim, S. M., 2021. Effect of meteorological factors on COVID-19 cases in Bangladesh. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23:9139-9162. [CrossRef]

- Kolluru, S. S. R., Patra, A. K., Nazneen, Nagendra, S. M. S., 2021. Association of air pollution and meteorological variables with COVID-19 incidence: Evidence from five megacities in India. Environ. Res. 195:110854. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y., Chang, C., Chang, S., Chen, P., Lin, C., Wang, Y., 2013. Temperature, nitrogen dioxide, circulating respiratory viruses and acute upper respiratory infections among children in Taipei, Taiwan: a population-based study. Environ. Res.120:109–118. [CrossRef]

- Maatoug, A. B., Triki, M. B., Fazel, H., 2021. How do air pollution and meteorological parameters contribute to the spread of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28:44132-44139. [CrossRef]

- Magazzino C., Mele M., Coccia M. 2022. A machine learning algorithm to analyze the effects of vaccination on COVID-19 mortality. Epidemiology and infection, 1–24. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Delgado A., Bontempi E., Coccia M., Kumar M., Farkas K., Domingo, J. L. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogenic microorganisms in the environment, Environmental Research, Volume 201, n. 111606. [CrossRef]

- Olak, A. S., Santos, W. S., Susuki, A. M., Pott-Junior, H., Skalny, A. V., Tinkov, A. A., Aschner, M., Pinese, J. P. P., Urbano, M. R., Paoliello, M. M. B., 2021. Meteorological parameters and cases of COVID-19 in Brazilian cities: an observational study. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Pal, S. K., Masum, M. H., 2021. Effects of meteorological parameters on COVID-19 transmission trends in Bangladesh. Environ. Sustain. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, N.R., Fouladi-Fard, R., Aali, R., Shahryari, A., Rezaali, M., Ghafouri, Y., Ghalhari, M.R., Asadi-Ghalhari, M., Farzinnia, B., Gea, O.C., Fiore, M., 2021. Bidirectional association between COVID-19 and the environment: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 194:110692. [CrossRef]

- Rosario, D.K.A., Mutz, Y.S., Bernardes, P.C., Conte-Junior, C.A., 2020. Relationship between COVID-19 and weather: Case study in a tropical country. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 229:113587. [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M., 2020. Impact of weather on COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Sci. Total Environ. 728:138810. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Piedra, C., Cruz-Cruz, C., Gamiño-Arroyo, A. E., Prado-Galbarro, F. J., 2021. Effects of air pollution and climatology on COVID-19 mortality in Spain. Air Qual. Atmos. Health. 14:1869-1875. [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S.A., Owusu, P.A., 2020. Impact of meteorological factors on COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from top 20 countries with confirmed cases. Environ. Res. 191:110101. [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, S., Shahzad, K., Fareed, Z., Shahzad, U., 2021. A study on the effects of meteorological and climatic factors on the COVID-19 spread in Canada during 2020. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. [CrossRef]

- Schuit, M., Ratnesar-Shumate, S., Yolitz, J., Williams, G., Weaver, W., Green, B., Miller, D., Krause, M., Beck, K., Wood, S., Holland, B., Bohannon, J., Freeburger, D., Hooper, I., Biryukov, J., Altamura, L.A., Wahl, V., Hevey, M., Dabisch, P., 2020. Airborne SARS-COV-2 is rapidly inactivated by simulated sunlight. J. Infect. Dis. 222:564-571. https://doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa334.

- Srivastava, A. 2021. COVID-19 and air pollution and meteorology-an intricate relationship: A review. Chemosphere. 263:128297. [CrossRef]

- Tosepu, R., Gunawan, J., Effendy, D.S., Ahmad, L.O.A.I., Lestari, H., Bahar, H., Asfian, P., 2020. Correlation between weather and covid-19 pandemic in Jakarta, Indonesia. Sci. Total Environ. 725:138436. [CrossRef]

- TUIK, 2021. The population of provinces in 2021. https://cip.tuik.gov.tr/# (accessed: September 2021).

- WHO, World Health Organization, 2021. https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed: 27 September 2021).

- Wu, Y., Jing, W., Liu, J., Ma, Q., Yuan, J., Wang, Y., Du, M., Liu, M., 2020. Effects of temperature and humidity on the daily new cases and new deaths of COVID-19 in 166 countries. Sci. Total Environ. 729: 139051. [CrossRef]

- WWO, World Weather Online, 2021. https://www.worldweatheronline.com (accessed: September 2021).

- Xie, J., Zhu, Y., 2020. Association between ambient temperature and COVID-19 infection in122 cities from China. Sci. Total Environ. 724:138201. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y., Pan, J., Wang, W., Liu, Z., Kan, H., Qui, Y., Meng, X., Wang, W., 2020. Association of particular matter pollution and case fatality rate of COVID-19 in 49 Chinese cities. Sci. Total Environ. 741:140396. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J., Yun, H., Lan, W., Wang, W., Sullivan, S.G., Jia, S., Bittles, A.H., 2006. A climatologic investigation of the SARS-CoV outbreak in Beijing, China. Am. J. Infect. Control. 34(4):234-236. https://doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2005.12.006.

- Zoran, M.A., Savastru, R.S., Savastru, D.M., Tautan, M.N., 2020. Assessing the relationship between surface levels of PM2.5and PM10 particulate matter impact on COVID-19 in Milan, Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 738:139825. [CrossRef]

| Study period | Study region (Country) |

Parameters | Analyses | Results/Suggestions | References |

| February 3, 2020 - July 14, 2020 | Spain | Solar radiation, precipitation, daily temperature, and wind speed | Multilevel Poisson regression | Air pollution can be a key factor in understanding the mortality rate for COVID-19 in Spain. | Sanchez-Piedra et al. 2021 |

| July 1 to October 31, 2020 | Brazil | Atmospheric pressure, temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, solar irradiation, sunlight, dew point temperature, and total precipitation | Pearson's correlation test and Regression tree analysis | The results encourage meteorological information as critical in future risk assessment models. | Olak et al. 2021 |

| March 9 to November 19, 2020 | Saudi Arabia | Wind speed and temperature | Poisson regression | Air pollution could be a significant risk factor for respiratory infections and virus transmission. | Maatoug et al. 2021 |

| February to April 10, 2020 | Canada | Temperature and humidity | The quantile-on-quantile (QQR) approach | Temperature and humidity have a direct negative relationship with COVID-19 infections. | Sarwar et al. 2021 |

| April to May 2020 | Bangladesh | Rainfall, temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed | Spearman's rank correlation | Significant positive associations between relative humidity and COVID-19 cases, while with temperature both positive and negative associations |

Pal and Masum, 2021 |

| February to June 2020 | India | Temperature, relative humidity, wind speed | Pearson correlation | Meteorological parameters may have promoted COVID-19 incidences, especially the confirmed cases. | Kolluru et al. 2021 |

| February 3 to May 5, 2020 | Korea | Temperature, wind speed, humidity, and air pressure |

Generalized Additive Model (GAM) | There was a significant nonlinear relationship between daily temperature, humidity and COVID-19 confirmed cases. | Hoang and Tran, 2021 |

| March 01 to July 07, 2020 | United States | Temperature and humidity | Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall rank correlations | The temperature was found to have a negative correlation, while humidity highlighted a positive correlation with daily new cases of COVID-19 in New Jersey. | Doğan et al. 2020 |

| As of March 27, 2020 | 166 countries excluding China | Temperature and humidity | A log-linear Generalized Additive Model (GAM) | The COVID-19 pandemic may be partially suppressed with temperature and humidity increases | Wu et al. 2020 |

| Kendall's Correlation Coefficients, rk | ||||||

| Provinces of the Black Sea Region, a geographical region of Turkey | ||||||

| Parameters | Samsun | Sinop | Ordu | Giresun | Trabzon | Rize |

| Minimum Temperature | -0.451 | -0.350 | -0.488 | -0.350 | -0.050 | -0.150 |

| Maximum Temperature | -0.333 | -0.350 | -0.451 | -0.350 | -0.143 | -0.150 |

| Average Temperature | -0.390 | -0.390 | -0.451 | -0.350 | -0.050 | -0.195 |

| Average Wind Speed | 0.143 | 0.321 | 0.195 | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.098 |

| Average Gust | 0.143 | 0.321 | 0.195 | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.098 |

| Average Precipitation | 0.429 | 0.619 | 0.429 | 0.143 | 0.333 | 0.195 |

| Average Relative Humidity | 0.098 | 0.098 | 0.150 | 0.150 | 0.000 | 0.293 |

| Average Cloud | 0.524 | 0.429 | 0.390 | 0.293 | 0.488 | 0.390 |

| Average Pressure | 0.714* | 0.333 | 0.429 | 0.333 | 0.048 | 0.143 |

| Average Sun Hour | -0.810* | -0.429 | -0.524 | -0.429 | -0.429 | -0.524 |

| Spearman's Correlation Coefficients, rs | ||||||

| Provinces of the Black Sea Region, a geographical region of Turkey | ||||||

| Parameters | Samsun | Sinop | Ordu | Giresun | Trabzon | Rize |

| Minimum Temperature | -0.673 | -0.491 | -0.703 | -0.491 | -0.910 | -0.182 |

| Maximum Temperature | -0.607 | -0.491 | -0.673 | -0.491 | -0.179 | -0.182 |

| Average Temperature | -0.649 | -0.523 | -0.673 | -0.491 | -0.091 | -0.198 |

| Average Wind Speed | 0.250 | 0.306 | 0.143 | 0.252 | 0.143 | 0.144 |

| Average Gust | 0.250 | 0.321 | 0.558 | 0.214 | 0.107 | 0.900 |

| Average Precipitation | 0.571 | 0.786* | 0.464 | 0.214 | 0.429 | 0.054 |

| Average Relative Humidity | 0.234 | 0.072 | 0.273 | 0.182 | 0.054 | 0.487 |

| Average Cloud | 0.714 | 0.607 | 0.631 | 0.505 | 0.667 | 0.631 |

| Average Pressure | 0.857* | 0.500 | 0.679 | 0.500 | 0.143 | 0.214 |

| Average Sun Hour | -0.893** | -0.571 | -0.679 | -0.536 | -0.643 | -0.679 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).