1. Introduction

Almost every country across the world is struggling with the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. It has been more than two years since COVID-19 was identified in China, and no one knows when it will end. The tropics and subtropics, as well as arid and semi-regions, are severely affected by widespread COVID-19[

1,

2,

3]. Remedial measures such as social distancing followed by lockdowns were imposed as a strategy to control the spread of the pandemic [

4].

Initial epidemiological research has indicated that weather influences the rate of SARS-Cov-2 infections. By February 2022, the COVID-19 pandemic, which started in late December 2019, had its fifth peak, with 1.52 million confirmed cases and 30,331 deaths in Pakistan as of March 21, 2022 (

https://covid.gov.pk/stats/pakistan). Beyond person-to-person transmission via direct and indirect contact, studies have shown that meteorological and environmental factors play crucial roles in the transmission and prevention of COVID-19. For example, temperature fluctuations can affect transmission rates by altering the stability of the virus on various surfaces. [

5]. Symptoms of coronavirus infection resemble those of the flu, and transmission is less likely under hot and humid conditions [

6]. Given the similar patterns seen in SARS-Cov-1 infections, health experts speculated that rising summer temperatures would reduce the spread of COVID-19. Investigations from [

7] found a positive correlation between COVID-19 cases and average temperature ranges, whereas a negative correlation was noted between humidity and rainfall. Furthermore, [

8] identified rainfall (precipitation) as a crucial factor affecting the spread of COVID-19. Therefore, it is vital to investigate the potential impact of changes in meteorological factors on the COVID-19 infection rate.

Pakistan is ranked as the fifth most populous country in the world, with a semi-arid and tropical monsoon climate [

8,

9,

10]. A complex relationship existed between meteorological variables and mortality, implying a higher level of COVID-19 exposure. However, studies related to the association between various meteorological parameters and local-level COVID-19 mortality rates in Pakistan are scarce. The association between meteorological factors and COVID-19 mortality has been investigated by researchers like [

12]and [

7]. However, these studies have been limited in several ways: research areas were geographically limited, mainly concentrated in a few cities [

7] or at a national level [

12]. Hence, meteorological and COVID-19 data were only from a few cities, without accounting for detailed insight, that is, provincial, capital, and territorial level variations. Moreover, the authors mainly used simple approaches, such as descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients [

13,

14]. However, these simple approaches do not account for heterogeneity in the datasets, which may question the robustness of the findings [

15]. Additionally, most of these studies performed analyses at the national level [

15] without accounting for sub-national-level variations.

The linear logistic regression (LR) approach has grown into a standard classification approach, competing with other statistical techniques in many innovation-friendly scientific fields [

16]. Researchers such as [

17] used this technique to identify a connection between meteorological indicators and the COVID-19 cases in Pakistan. Logistic regression models, along with the Random Forest technique, were also used by [

18]to perform groundwater potential analysis in China, as groundwater levels tend to vary both seasonally and geographically [

19]. Shahibi et al. [

20] used the LR model to perform landslide susceptibility mapping in the Central Zab Basin in Iran. Moreover, a study conducted by [

21] showed that LR had better performance than other statistical techniques, such as the Support Vector Machine model, in terms of sensitivity to training samples. Hence, due to the promising results, we used LR in our study to know the association between meteorological parameters and COVID-19 cases.

In this study, we proposed to evaluate the relationship between meteorological parameters (temperature, humidity, and rainfall) and COVID-19 cases at a national and sub-national level using the LR approach. This is the first study of its kind in Pakistan, especially at the subnational (provincial, capital, and territories) level. Such an extensive COVID-19 study in Pakistan, especially at the subnational level, is not yet available. Moreover, a data length of 365 days was used to predict the relationship between the meteorological parameters and COVID-19 cases. Such lengthy datasets have proven to be more effective in improving the performance of the models [

22].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

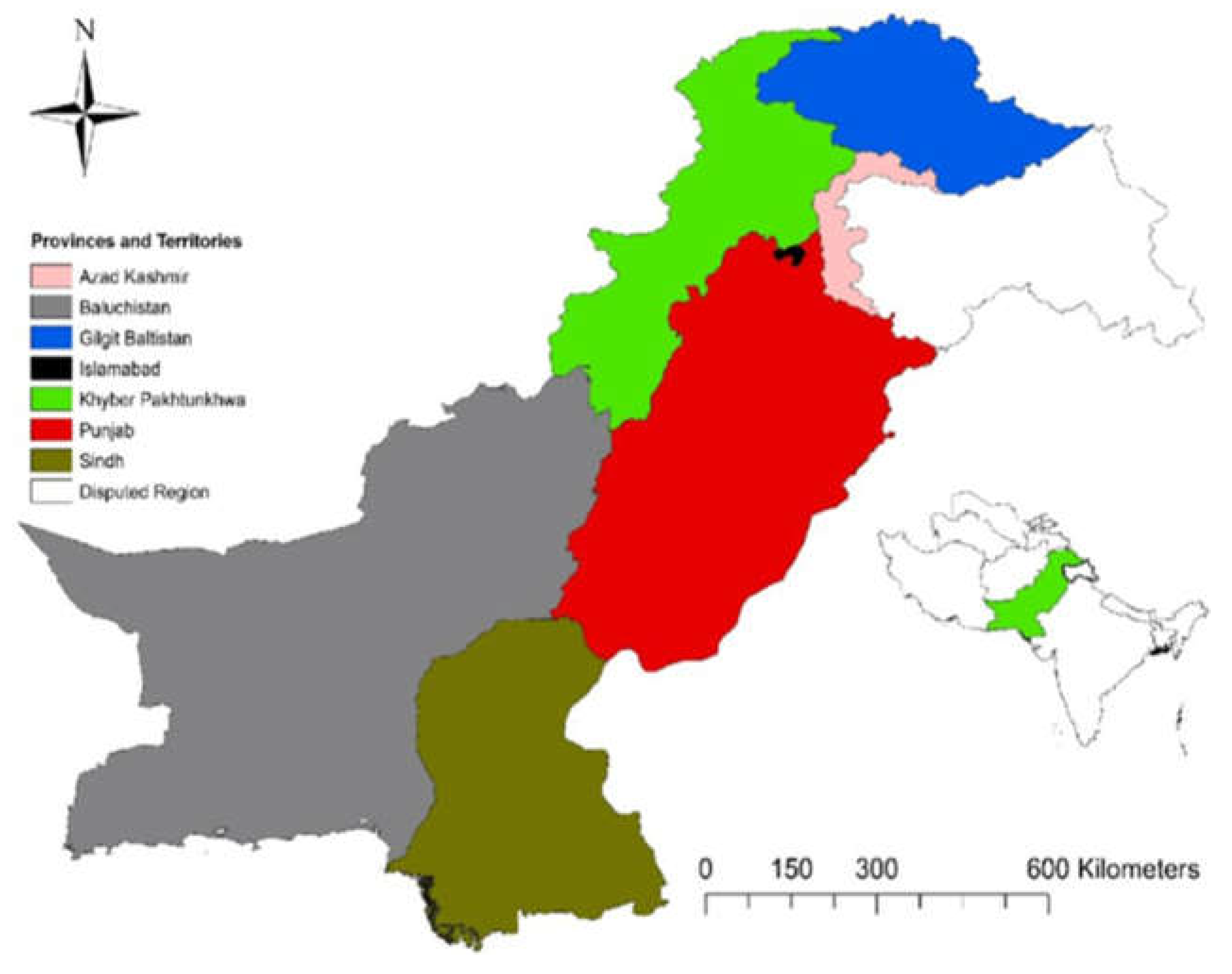

Pakistan lies in South Asia at 30.00°N and 70.00°E. It is ranked as the 5th most populous country in the world, with a population of almost 207 million as per a census conducted in 2017 by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS)(

https://www.pbs.gov.pk/content/population-census). According to the World Bank, it covers an area of 881,913 square kilometres (

https://data.worldbank.org). The sub-national level includes four provinces, namely Sindh, Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), and Balochistan; two territories, Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) and Azad Kashmir (AJK), and the capital, Islamabad (

Figure 1).

2.2. Epidemic Data

We used daily COVID-19 data obtained from the Ministry of National Health Services Regulations and Coordination of the Government of Pakistan (NHSRC) (

https://covid.gov.pk/). We selected daily confirmed and accumulated cases, as well as daily deaths and accumulated death cases of COVID-19 in Pakistan. The daily data were obtained from the beginning of 2021, i.e., the 1st of January 2021 until the 31st of December 2021, for the national as well as for the sub-national level cases.

2.3. Meteorological Data

Data on meteorological factors, including humidity, rainfall, and maximum and minimum temperatures for that year, were obtained from the Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD). The analysis involved employing the statistical software package STATA and the Spearman rank correlation test; additionally, SPSS was utilised to examine the correlation between these meteorological aspects and confirmed COVID-19 cases.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

In this study, we used a mixed-method approach. A linear logistic regression model [

23] was used to validate the association between COVID-19 incidence and climatic factors. In addition to observing the correlation between various climatic factors, associations were also calculated. In the regression analysis, the new cases were used as the prediction variables, whereas the input variables included the effects of maximum temperature, minimum temperature, rainfall, and humidity. The analysis was conducted using the STATA 15. The general equation for the analysis is as follows:

In the above equation, α is the intercept, and β is the coefficient in the case of each input variable. Each β reflects how Y will change with the X, which is associated with the β when all other X variables are kept constant [

24]. Furthermore, a scheme for the association between meteorological parameters and COVID-19 cases in Pakistan is shown in

Figure 2.

3. Results

To determine the relationships among different variables and the prediction of new cases, Pearson’s correlation and regression analyses were conducted on the COVID-19 data. The data were collected for a period of one year, from January 2021 to December 2021. The association of maximum and minimum temperature, rainfall, and humidity with the prediction of new COVID-19 cases was observed in this study, and the findings are presented in the following sections.

3.1. National Level

The model performance for nationally confirmed COVID-19 cases in Pakistan is presented in

Table 1. It is seen that the variables of intercept, minimum and maximum temperature and humidity have a statistically significant impact on the prediction of the new COVID-19 cases. The analysis was run at a 95% confidence interval; therefore, a p-value< 0.05, confirming that the role of the input variable is statistically significant in the prediction of new cases of COVID-19. Studies conducted by [

7] had similar findings to ours, i.e., the temperature is highly associated with the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we could not find any significance between rainfall and COVID-19 daily cases at the national level.

3.2. Sub-National Level

3.2.1. Punjab

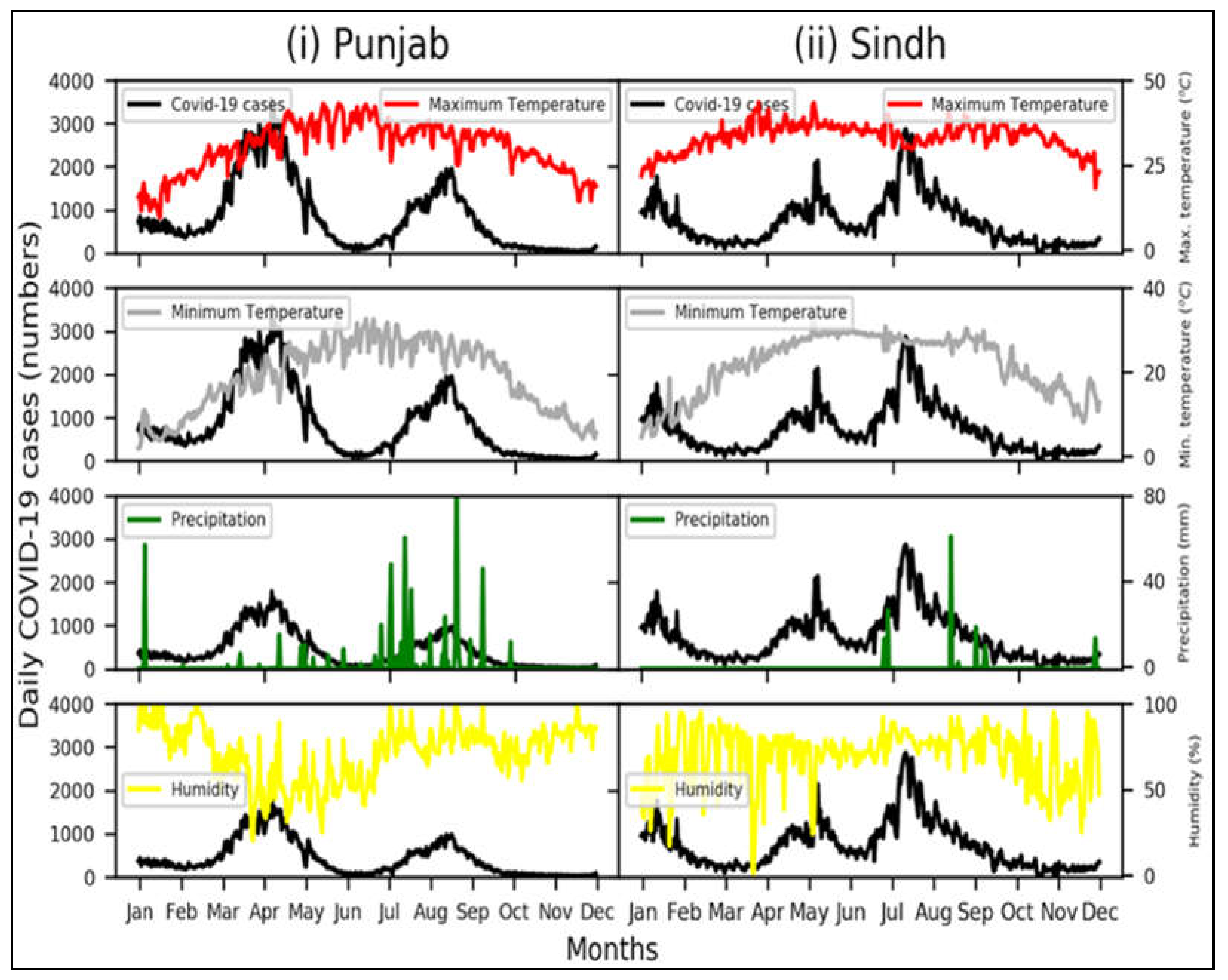

Punjab is the most populous and the largest province of Pakistan and accordingly reported the maximum number of COVID-19 confirmed cases (

Figure 3i). This has witnessed two COVID-19 peaks, first in April and the next in August. Lower daily COVID-19 cases are witnessed for months with a raised temperature, from May to July. Hence, increased temperatures help reduce the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings by [

5]. Ahmed, (2017) [

6] presented that COVID-19 transmission is least in hot environments. Moreover, higher daily COVID-19 cases are seen in August, which receives higher rainfall due to the monsoon season and promotes the spread of the pandemic. It has been observed that the prediction power of the estimated model is 30.68%. It is imperative to mention that even if the prediction power is less, still the analysis results show that these variables of intercept, minimum temperature and rainfall have a statistically significant impact on the prediction of the new COVID-19 cases. The analysis was run at 95% of the confidence interval. The results showed that humidity and rainfall were significant predictive parameters, with p-values of less than 0.05.

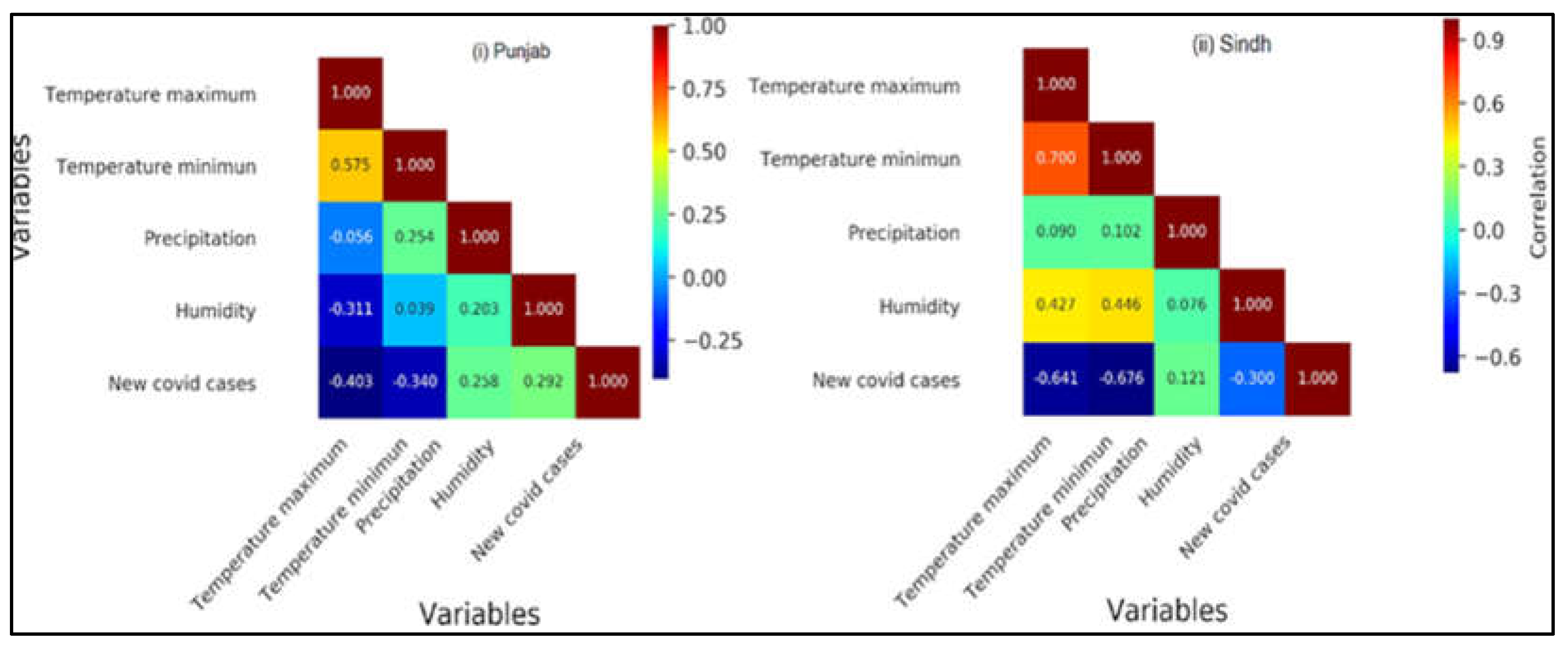

Pearson correlation is an important analysis technique in which the relationships between different variables are determined by checking how they are related directly or indirectly. The results of the analysis presented in

Figure 4i show that the impact of temperature on the new cases is negative. This confirms that a higher temperature lowers the spread of the virus, thereby limiting its spread. Similar findings have also been reported by other researchers. For example, [

25] reported that, with an increase in temperature, the number of new COVID-19 cases decreased. Several other studies on the relationship between meteorological factors and the global spread of COVID-19 have reported a negative correlation between temperature and COVID-19 morbidity and mortality [

6,

26]. An increase in the amount of rainfall and humidity increased the number of new COVID-19 cases. This confirms that the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic was directly associated with rainfall and humidity. Detailed results are presented in

Table 1.

3.2.2. Sindh

In Pakistan, Sindh is the second most populous province, with approximately 47 million people (PBS). Accordingly, it has witnessed the second-highest number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in Pakistan. Unlike Punjab, the COVID-19 confirmed cases have reached two peaks, May 2021 and July 2021 and the last in August 2021 (

Figure 3ii). Lower temperatures were observed in January and February, which could be a reason for the rise in COVID-19 cases, in addition to the intense rainfall in July. Similar to Punjab, higher temperatures were recorded from May to July, resulting in a lower number of COVID-19 cases in Sindh.

Table 1 presents the results of the regression analysis for Sindh. The prediction power of the estimated model is 51.4%, which is quite high compared to the previously reported prediction model for the case of Punjab. The results showed that the p-values for almost all predictive parameters were statistically significant (p< 0.05). This prediction confirms that the proposed model tends to predict new cases of COVID-19 in Sindh with an accuracy of more than 50%. The results of the analysis revealed that the intercept, maximum, and minimum temperature and humidity variables were significant predictors of new COVID-19 cases in Sindh. It is vital to mention that the variable of mortality rate was omitted from the analysis because it does not form any significant relationship with any of the other variables in the analysis because of the extremely small values of mortality. The detailed results of the prediction using the regression analysis are available in

Table 1. The results of the Pearson correlation analysis between the different variables in Sindh are shown in

Figure 4ii. Similar to Punjab, the impact of temperature on new cases of COVID-19 is negative in Sindh. In other words, temperature has a negative impact on the spread of the virus. On the contrary, the amount of rainfall and humidity has a direct relationship with COVID-19 case numbers. It is concluded that an increase in the amount of precipitation and humidity promoted the spread of the virus, which increased the number of new COVID-19 cases in the Sindh province. These findings are in line with the results earlier reported by [

3].

3.2.3. Other provinces, territories and Islamabad

According to the population statistics obtained from PBS, the number of people living in other provinces (KPK and Balochistan), territories (GB and AJK), and Islamabad are far fewer than those in provinces such as Punjab and Sindh. Consequently, as per data obtained from the concerned department, it is revealed that the number of COVID-19 cases is much lower compared to Punjab and Sindh. In KPK, Balochistan, GB, AJK, and Islamabad, our LR models showed that none of the climatic parameters was significant for the spread of COVID-19 (

Table 1). Hence, the low performance of our models could mainly be attributed to the lower number of COVID-19 reported cases there. As per the study conducted by [

24], South America and some Asian countries had relatively lower COVID-19 cases due to the strictest measures. In the regression analysis, no statistically significant association between the variables and COVID-19 cases was observed. Hence, the performance of the regression models was highly controlled by the number of cases for each variable.

4. Discussion

The confirmed cases of COVID-19 in this region are among the top ranks in regions that encounter widespread COVID-19. It is the first study to demonstrate how temperature (minimum and maximum), rainfall, and relative humidity interact to influence COVID-19 spread and mortality at the national and subnational levels in Pakistan. The country has a diverse range of climates owing to its changing topography. Daily meteorological data for parameters such as temperature (minimum and maximum), rainfall, and humidity were compared with COVID-19 incidence cases at both national and sub-national levels in Pakistan.

At the national level, the minimum and maximum temperatures and humidity had a statistically significant association with daily COVID-19 cases. The study conducted by [

11] supports our findings that temperature is highly linked to the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the combined effects of COVID-19 and climate variables have exacerbated human health risks and created synergies [

28,

29]. At the provincial level, lower daily COVID-19 cases were witnessed in Punjab for high-temperature months, from May to July. This indicates that higher temperatures resisted the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. A study by[

5] found that COVID-19 transmission was the least in hot environments. This phenomenon can also be observed in relatively hot countries, i.e., the impact of COVID-19 spread was far less in these regions [

30]. On the contrary, the impact of rainfall and humidity is directly related to the reporting of new COVID-19 cases. As per findings by [

28], rainfall during monsoon could be a reason for higher daily COVID-19 cases in Punjab during August. In Sindh, lower temperatures were seen in January and February which could be a reason for increased COVID-19 cases in addition to heavy rainfall in July. Similar to Punjab, lower COVID-19 daily cases were reported during months with higher temperatures, i.e., May to July. Hence, it was revealed that an increased temperature had a negative impact on the spreading of the virus. Similar findings were reported by [

16] that a high temperature limits the spread of the virus. On the contrary, an increase in the amount of precipitation and humidity promoted the spreading of the virus, which increased the number of newly reported COVID-19 cases. [

32]showed that virus aerosol transmission is suppressed by high humidity. Moreover, high humidity enhances indirect virus transmission by increasing the virus particle's stability inside droplets and on surfaces [

33].

For the remaining two provinces (KPK and Balochistan) and territories, our LR models have shown that none of the climatic parameters was significantly associated with the spread of COVID-19. The number of reported daily COVID-19 cases was far lower in these areas compared to Punjab and Sindh. Hence, the low performance of our models could mainly be attributed to the lower number of COVID-19 reported cases there. Studies conducted by [

34] have shown that the performance of statistical models was considerably lower due to the lack of a sufficient amount of training data needed to capture the COVID-19 case dynamics.

The findings of this study were consistent across all evaluated measures. Furthermore, the presence of a substantial number of asymptomatic positive cases within the community serves as a significant factor that can markedly alter the results concerning the meteorological impact of COVID-19 cases. Additionally, the limitations imposed on daily testing capacity may affect the number of confirmed new cases. Finally, due to its ecological design, this study is constrained in its capacity to establish causal relationships, as the associations observed at an aggregate level may not necessarily correspond to those at an individual level. Our study did not aim to explore other factors influencing the spread and mortality of COVID-19, including social distancing measures, healthcare system organisation, medical resources, public adherence, and personal hygiene. Investigating these areas further could provide a deeper understanding of how COVID-19 cases relate to climatic factors.

5. Conclusions

The study spans a full year following the outbreak of COVID-19, allowing for a clearer observation of the seasonal characteristics of the virus spread. The positive correlation between temperature and COVID-19 cases in this study, coupled with the peak incidence of cases in July, underscores the adaptable and persistent nature of COVID-19. However, climatic factors do not operate as isolated variables, as other contributing factors are interconnected, creating a conducive environment for the spread of COVID-19 and exacerbating its impact. This study provides valuable insights for policymakers regarding the transmission of COVID-19 and its association with meteorological variables for such kind of future outbreaks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, IA. and MA.; methodology, IA, MA, MY.; software, IA, HA, SY and ZT.; validation, MO, IA, MA UAO.; formal analysis, IA and ZT; investigation, MT and IA; resources, MY and UAO; data curation, MT and IA.; writing—original draft preparation, IA, MA.; writing—review and editing, MO, SY, ZT, UAO and MY.; visualization, MA; supervision, MY.; project administration, MA.; funding acquisition, MY and UAO. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

No funding received.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Study was received by the ethical approval (NO:1291/CE/2022) from Mirpur University of Science Technology, Mirpur, 10250, Pakistan.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be available on request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Ministry of National Health Services Regulations and Coordination, Government of Pakistan and Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD) for the provision of the COVID-19 pandemic and meteorological data of Pakistan, respectively.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alqasemi, A.S., et al., Impact of COVID-19 lockdown upon the air quality and surface urban heat island intensity over the United Arab Emirates. Science of The Total Environment, 2021. 767: p. 144330. [CrossRef]

- Gwenzi, W., Dangerous liaisons? As the COVID-19 wave hits Africa with potential for novel transmission dynamics: a perspective. Journal of Public Health, 2022. 30(6): p. 1353-1366. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.M., et al., The effects of regional climatic condition on the spread of COVID-19 at global scale. The Science of the total environment, 2020. 739: p. 140101-140101. [CrossRef]

- Syafarina, I., et al. Evaluation of the Social Restriction and its Effect to the COVID-19 Spread in Indonesia. in 2021 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology (ICoICT). 2021.

- Riddell, S., et al., The effect of temperature on persistence of SARS-CoV-2 on common surfaces. Virology Journal, 2020. 17(1): p. 145. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J., et al., Effect of environmental and socio-economic factors on the spreading of COVID-19 at 70 cities/provinces. Heliyon, 2021. 7(5): p. e06979. [CrossRef]

- Basray, R., et al., Impact of environmental factors on COVID-19 cases and mortalities in major cities of Pakistan. Journal of Biosafety and Biosecurity, 2021. 3(1): p. 10-16. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.N., et al., Climate change impact on water scarcity in the Hub River Basin, Pakistan. Groundwater for Sustainable Development (2024): 101339. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M., et al., Flash Drought Monitoring in Pakistan Using Machine Learning Techniques and Multivariate Drought Indices. Technical Journal 3.ICACEE (2024): 717-729.

- Nguyen, D. T., et al., Projection of climate variables by general circulation and deep learning model for Lahore, Pakistan. Ecological Informatics 75 (2023): 102077. [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, A.B., et al., Predicting COVID-19 based on environmental factors with machine learning. Intelligent Automation and Soft Computing, 2021: p. 305-320. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A., et al., The nexus between meteorological parameters and COVID-19 pandemic: case of Islamabad, Pakistan. Environmental Sustainability, 2021. 4(3): p. 527-531. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q., et al., Impact of wind speed and air pollution on COVID-19 transmission in Pakistan. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 2021. 18(5): p. 1287-1298. [CrossRef]

- Fawad, M., et al., Statistical analysis of COVID-19 infection caused by environmental factors: Evidence from Pakistan. Life Sciences, 2021. 269: p. 119093. [CrossRef]

- Briz-Redón, Á. and Á. Serrano-Aroca, The effect of climate on the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic: A review of findings, and statistical and modelling techniques. Progress in physical geography: Earth and Environment, 2020. 44(5): p. 591-604.

- Irfan, M., et al., Does temperature matter for COVID-19 transmissibility? Evidence across Pakistani provinces. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2021. 28(42): p. 59705-59719. [CrossRef]

- Raza, A., et al., Association between meteorological indicators and COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2021. 28(30): p. 40378-40393. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., et al., GIS-based groundwater potential analysis using novel ensemble weights-of-evidence with logistic regression and functional tree models. Science of the Total Environment, 2018. 634: p. 853-867. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S., et al., Impacts of climate and land-use change on groundwater recharge in the semi-arid lower Ravi River basin, Pakistan. Groundwater for Sustainable Development, 2022. 17: p. 100743. [CrossRef]

- Shahabi, H., M. Hashim, and B.B. Ahmad, Remote sensing and GIS-based landslide susceptibility mapping using frequency ratio, logistic regression, and fuzzy logic methods at the central Zab basin, Iran. Environmental Earth Sciences, 2015. 73(12): p. 8647-8668. [CrossRef]

- Couronné, R., P. Probst, and A.-L. Boulesteix, Random forest versus logistic regression: a large-scale benchmark experiment. BMC bioinformatics, 2018. 19(1): p. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., et al., The increasing rate of global mean sea-level rise during 1993–2014. Nature Climate Change, 2017. 7(7): p. 492-495. [CrossRef]

- Rencher, A.C., A review of “Methods of Multivariate Analysis, ”. 2005, Taylor & Francis.

- Jaccard, J., et al., Multiple regression analyses in clinical child and adolescent psychology. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 2006. 35(3): p. 456-479. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C., et al., Meteorological factors and COVID-19 incidence in 190 countries: an observational study. Science of the Total Environment, 2021. 757: p. 143783. [CrossRef]

- Kodera, S., E.A. Rashed, and A. Hirata, Correlation between COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates in Japan and local population density, temperature, and absolute humidity. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2020. 17(15): p. 5477.

- Cao, Y., et al., Multiple relationships between aerosol and COVID-19: A framework for global studies. Gondwana Research, 2021. 93: p. 243-251. [CrossRef]

- Nundy, S., et al., Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on socio-economic, energy-environment and transport sector globally and sustainable development goal (SDG). Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021. 312: p. 127705.

- Watts, N., et al., The 2020 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises. The Lancet, 2021. 397(10269): p. 129-170. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L., et al., Meteorological impact on the COVID-19 pandemic: A study across eight severely affected regions in South America. Science of the Total Environment, 2020. 744: p. 140881. [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M.H., et al., COVID-19 and the environment: A critical review and research agenda. Science of the Total Environment, 2020. 745: p. 141022. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., A. Hiyoshi, and S. Montgomery, COVID-19 case-fatality rate and demographic and socioeconomic influencers: worldwide spatial regression analysis based on country-level data. BMJ open, 2020. 10(11): p. e043560. [CrossRef]

- Paynter, S., Humidity and respiratory virus transmission in tropical and temperate settings. Epidemiology & Infection, 2015. 143(6): p. 1110-1118. [CrossRef]

- Zeroual, A., et al., Deep learning methods for forecasting COVID-19 time-Series data: A Comparative study. Chaos, solitons, and fractals, 2020. 140: p. 110121-110121. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).