1. Introduction

There are many ways for alien and/or invasive insect species to get into certain area. Sometimes it is their own movement, usually associated with short distances, whereas the long distances dispersal is usually enabled by human activities. Human activities, such as the global trade in goods, have resulted in the passive dispersal of species that were previously restricted to their natural range. Insects act like stowaways, successfully utilizing this strategy in a number of ways. Some species can adapt quickly to new environmental conditions, while others require additional time. Those which adapt easily, in the absence of natural enemies, build their population and reach a large number quite rapidly and become species of economic importance for plant production and/or biodiversity or species of medical importance to humans and animals.

Mosquitoes are insects of public health concern when they occur in large densities and are a nuisance but also when they transmit pathogens. Collecting data on vectors of public health concern is critical to understanding the level of risk that countries face, and defining the actions that need to be taken [

1]. Invasive mosquito species are characterized by their ability to colonize new urban areas. These invasive mosquito species can displace native mosquito species, but the greatest concern is the threat to human and animal health. With significant impacts on socioeconomic development of countries, Europe has always had been both endemic and epidemic autochthonous mosquito-borne diseases (MBD). The concern is increasing as both vectors and pathogens are increasingly introduced through international travel and trade. Some of these diseases are newly emerging or re-emerging after long absence; others are simply spreading continuously. Their emergence is often related to changes in ecosystems, human behavior, and climate. Although the number of autochthonous infections in European countries is still low, predictions show an increasing trend [

2].

Invasive mosquito species may remain undetected for some time as was the case with

Aedes japonicus (Theobald 1901) in Switzerland. The first field survey was conducted after complaints from residents in an area of approximately 1 400 km

2 that was colonized by

Ae. japonicus. This detection led to the conclusion that the species had gone unnoticed for several years. The tiger mosquito

Aedes albopictus Skuse 1894 was present in Albania and Italy for 30 and 17 years, respectively, before the first outbreak of MBD was reported [

2]. In contrast, in France, autochthonous cases of chikungunya and dengue were not detected until four years after the species became established [

3] (Grandadam et al. 2011). This suggests that the favorable factors that promote disease transmission by invasive mosquitoes are now present in Europe [

2]. These factors are related to pathogen introduction, the vectorial capacity of the established mosquito populations, and the frequency of vector-host contacts. Climatic conditions can also have a direct impact on the pathogen but also influence vector reproduction, activity, and survival. Therefore, it is very important to monitor invasive mosquito species in each country in order to be prepared for possible disease outbreaks and to establish appropriate action programs.

The most dangerous invasive mosquito species in Europe is

Ae. albopictus. The importance of this species is reflected in its great vector competence and wide distribution in almost all European countries [

2].

Species that have attracted much attention in both urban and agricultural areas include stinkbugs, which can seriously threaten agricultural production of many crops, fruits, and vegetables. Those species overwinter in urban areas, invading houses, apartments, means of transportation, and many other man-made facilities where they are referred to as nuisance species. Sometimes thousands of specimens can occupy a house and disturb the inhabitants of household. During the summer, stinkbugs feed on a variety of plant hosts, and apart from the urban environments, favorable places for feeding and reproduction are found in crops and plantations of cultivated plants. Among them, two species from the family Pentatomidae stand out: the brown marmorated stink bug,

Halyomorpha halys Stål, and the green vegetable bug,

Nezara viridula L. In most countries, these invasive species were first reported in urban environments and transportation [

4,

5] from where they move to cultivated plants in the field. Their ability to release unpleasant odors is why they are called stink bugs and makes them hated in cities and towns.

2. Aedes albopictus Skuse 1894, Asian tiger mosquito (Diptera, Culicidae)

2.1. Success in dispersal

The species originated in tropical forests of Southeast Asia, and has spread worldwide.

Aedes albopictus was first recorded in Europe in 1979 in Albania [

6]. Although it became established in Albania, there were no reports in Albania or in any other European country until 1990, when it was found in Italy [

7]. Human activities, especially trade of used tires and ‘lucky bamboo’ [

8] and passive dispersal by public and private transport have spread the species worldwide. This has resulted in a widespread global distribution of

Ae. albopictus. It is now listed as one of the top 100 invasive species by the Invasive Species Specialist Group [

9].

The successful invasion of

Ae. albopictus is also the result of a combination of many abiotic and biotic factors, including ecological plasticity, strong competitiveness, globalization, lack of surveillance, and lack of efficient control [

8]. Climate change predictions suggest that

Ae. albopictus will continue to successfully invade areas beyond its current geographical boundaries [

2,

10,

11]. This mosquito has already shown signs of adaptation to temperate climates [

2,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], which could lead to disease transmission and spread in European countries.

2.2. Significance

Asian tiger mosquito is an opportunistic feeder and feeds on a wide range of hosts. It is characterized by its aggressive nuisance behaviour during the day when females are searching for blood of mammals [

13]. The list of blood hosts includes humans, domestic and wild animals, reptiles, birds and amphibians [

14] although it prefers human blood meals [

8]. It has the potential to become a serious health threat as a bridge vector of zoonotic pathogens to humans [

15]. This mosquito species is a competent vector of chikungunya virus, dengue virus, but also other 20 arboviruses, including yellow fever virus, Rift Valley fever virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, West Nile virus and Sindbis virus, as well as the nematode Dirofilaria, all of which are relevant to Europe [

16,

17].

Dengue virus transmission was detected in Serbia in 2015 [

18]. The human case was imported from Cuba but fortunately

Ae. albopictus was not present in the area where the patient was located.

2.3. First record in Serbia

The first detection of

Ae. albopictus was reported on 1

st September 2009 in an ovitrap at the Batrovci border crossing between Croatia and Serbia [

19].

2.4. Monitoring

Monitoring of the Asian tiger mosquitoes was initiated at the Batrovci border crossing in 2009. Since the species was detected, monitoring zones have been expanding each year to include new locations to be monitored. Monitoring was conducted using standard ovitraps (

Figure 1). The substrate for oviposition is tongue-depressor. In the current year (2022) monitoring was conducted in Novi Sad at 40 sites in the city area. At the level of Vojvodina Province, 173 ovitraps were placed, covering the entire territory of the province. Sixteen more ovitraps were placed in Loznica municipality (Macva County).

The exact locations were selected based on the biology and preferences of the species. All three types of habitats were selected: urban, semi-urban and rural. Oviposition sites were rich in vegetation (

Figure 2) and located near human settlements.

In addition, the presence of invasive mosquitoes was recorded through passive monitoring (Mosquito Alert app) when citizens sent photos via reports through the phone application.

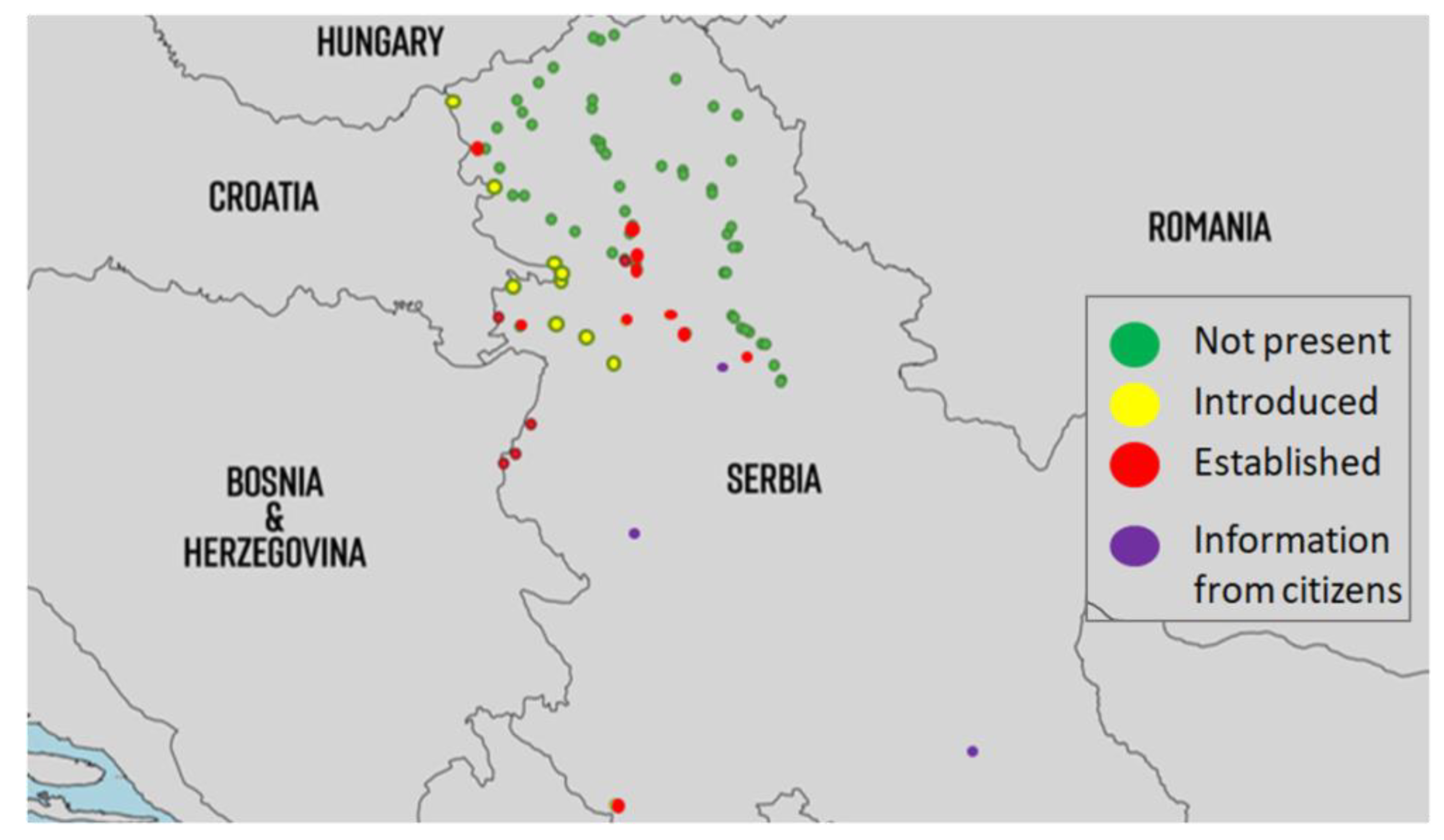

2.5. Distribution

From the first detection until today, the species has been present at this border crossing, as well as at sites along the highway leading from Batrovci to Ruma, while it has been present in Gostun (the border with Montenegro) since 2011. It is assumed that this species was not established in Serbia until 2017, but it has been recorded at the border crossing every year in the summer period, when travel from Western Europe to the East and vice versa is intense. In the first half of 2017, eggs of this species were recorded in Batrovci at the very beginning of the travelling season, from which it can be concluded that the population has settled permanently in Serbia since 2017 (Petrić, unpublished data). The third location where this species has settled is the urban part of Novi Sad, where populations of the Asian tiger mosquito have been continuously recorded in several places since 2018. So far,

Ae.

albopictus has successfully spread to all parts of Novi Sad. The presence of this species is also recorded in many other invaded localities, such as Inđija, Apatin, Kuzmin, Ruma, Sremska Mitrovica, Belgrade, Loznica, Niš, and Valjevo (

Figure 3). All border crossings with Croatia were also positive for the Asian tiger mosquito. The invasion of Serbia by Asian tiger mosquito can be considered very successful.

2.6. Applied control measures

Control of Ae. albopictus is very difficult and complex due to the various breeding sites (catch basins, any type of water containers, or artificial breeding sites) that could be inhabited by this invasive species. Invasive mosquito control has been done by adulticiding and laviciding treatments, conducted at the provincial or municipality level. However, conventional mosquito control measures as the only method to control Ae. albopictus, have low efficiency. The efficient control measures require an integrated mosquito management approach. One of the promising methods is the sterile insect technique. It was carried out for the first time in Serbia in 2022 (Petrić et al., unpublished data).

3. Aedes japonicus (Theobald 1900), Japanese bush mosquito or Asian rock pool mosquito (Diptera, Culicidae)

3.1. Success in dispersal

The Japanese bush mosquito is an Asian species, native to Japan, Korea, South China, Taiwan, and the Russian Federation [

20]. Its first finding in Europe was reported in 2000 from north-western France [

16]. Consequently, the species was found in Belgium in 2002 [

21], in Switzerland and Germany in 2008, Austria and Slovenia in 2011, and the Netherlands and Hungary in 2012 [

22,

23,

24]. In 2013 was reported from Croatia [

25]. Its spread continued to Liechtenstein and Italy in 2015, to Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2017, and to Serbia, Spain and Luxembourg in 2018 [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. The most recent reports of its introduction were from Romania in 2020 [

31] and Czech Republic 2021 [

32]. In Europe, this species become established in Belgium and was detected successively in Switzerland and Germany, where it spread rapidly [

22,

33].

Aedes japonicus has less specific aquatic habitats requirements, compared to

Ae.

albopictus, which may facilitate the further spread of this species [

16]. In its native range,

Ae. japonicus colonizes tree-hole habitats but this has not often been reported for newly established areas in Europe [

34]. Unlike native European mosquito species of genus

Aedes, this species have relatively short flight range [

35].

Aedes japonicus prefers forested habitats and inhabits rock pools and tree holes as natural breeding sites, but also artificial water recipients: containers, used tires, bird baths, toys, vinyl tarpaulins covering swimming pools, catch basins, rain pools, stone vessels, drinking fountains, tin cans, bath tubs, roof gutters, flower vases, plant pots, street gutters, rain water barrels, buckets, pans etc. [

36].

3.2. Significance

This species is also known as Asian tiger mosquito, a very aggressive daily biter. It demonstrated preference to feeding on mammals and humans [

36,

37,

38] but may also use blood of other hosts such as birds, rodents, etc. [

39,

40,

41]. Adults are often found in forested areas [

36] and are active during the day, dusk and dawn [

13]. The species prefers to bite humans outside and occasionally inside houses [

16]. This species has tested positive for West Nile virus in many cases in the United States [

13,

36]. Laboratory experiments have shown that Japanese bush mosquito is a competent vector of West Nile virus [

42]. Laboratory studies have also confirmed that

Ae. japonicus is a competent carrier of Japanese encephalitis virus [

43], La Crosse virus [

40] and moderately effective vector of Saint Louis encephalitis virus [

41], Eastern equine encephalitis virus [

39], Chikungunya virus and Dengue virus [

44] and Rift Valley fever [

45].

3.3. First record in Serbia

The Japanese bush mosquito entered Serbia in 2018. The species was first detected at the Ljuba border crossing with Croatia [

30].

3.4. Monitoring

Species was monitored using the same type of ovitraps and passive monitoring as for the Asian tiger mosquito. These two species were monitored simultaneously with the same traps.

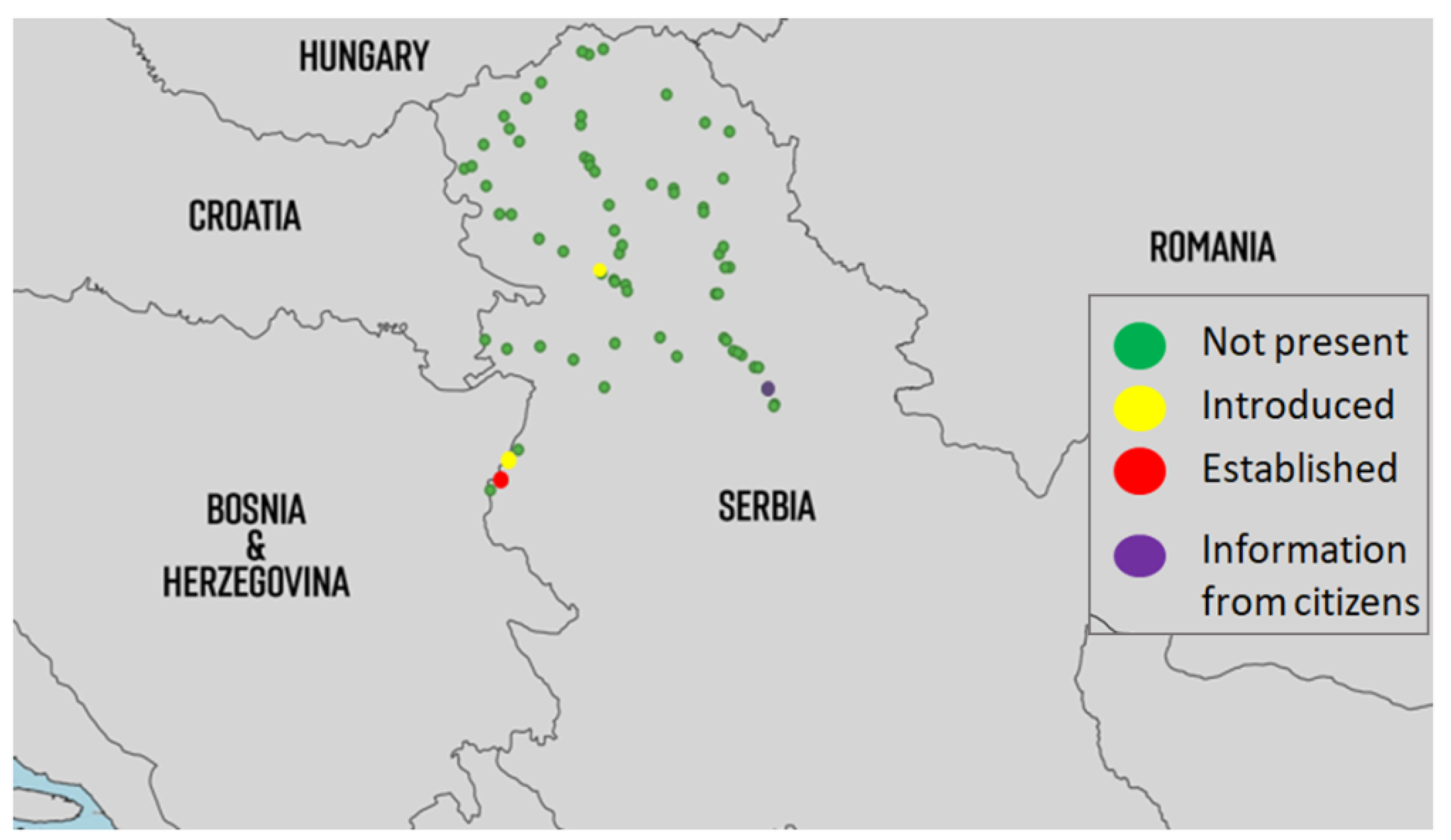

3.5. Distribution

In 2022 this species was detected in four locations (

Figure 4). Its occurrence was detected in Novi Sad (semi-urban environment) and in Loznica municipality in two locations around the city (one urban, one semi-urban). Passive monitoring showed that the species occurred in Opovo (South Banat County). Although ovitraps were set up in Opovo, we have not detected

Ae. japonicus there so far. One possible explanation is that we focused more on the biology and preferences of

Ae. albopictus in our studies and therefore neglected the preferences of the other mosquito species. Based on the report obtained through passive monitoring, we believe that the population of

Ae. japonicus in Serbia may be underestimated. Future monitoring efforts of

Ae. japonicus should be improved by focusing on their preferences.

3.6. Applied control measures

Fortunately, this species is not widespread in our country yet. Considering the similar biology of these two invasive mosquito species (especially breeding sites, mode of introduction, mammophilic preferences), the approach to their prevention and control should consist of a similar strategy. In Serbia, there are no special measures to control the population of Ae. japonicus. Control activities of Ae. japonicus are included in regular domestic mosquito control campaigns.

4. Halyomorpha halys Stål 1855, Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (Hemiptera, Pentatomidae)

4.1. Success in dispersal

The Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (BMSB) is species native to East Asia [

46], that successfully established outside this region, first in the USA in the late 1990s [

47] and later in Europe, in 2004 from Liechtenstein and Switzerland [

4,

48,

49]. Soon after these finds, the species spread and became established in almost all European countries: Germany [

50], France [

51], Italy [

52], Hungary [

53], Austria [

54], Romania [

55], Greece [

56], Spain [

57], Bulgaria [

58], Georgia and Abkhazia [

59], Russia [

60,

61], Slovakia [

62], Slovenia [

63], Croatia [

64], Bosnia and Herzegovina [

65], Albania [

66], Republic of North Macedonia [

5].

The most common route of spread of

H. halys is transport and trade of goods, which is confirmed in many European countries [

4,

5,

67]. The spread and increase of the BMSB population was first observed in large cities along the frequently used motorways. However, their dispersal into surrounding agricultural areas most likely occurs though their active flight, with summer generations flying farther than overwintering adults [

68]. The CLIMEX climate suitability model [

69] has shown that climatic conditions in Europe are suitable and consistent for further spread of BMSM, and that this species will most likely become economically important in almost all inhabited areas.

4.2. Significance

The Brown Marmorated Stink Bug is a highly polyphagous species that feeds on more than 106 ornamental plants in its native range [

70,

71]. Many vegetables, field and even medicinal plants are added to the list of endangered plant species [

71], with major economic losses occurring in plants of the Fabaceae and Rosaceae families. Its harmfulness is reflected in the fact that it feeds on a wide range of hosts, including crop plants, weeds, and ornamentals, providing it with a constant food source and opportunities to maintain populations. In Japan, the species mainly attacks fruits and soybeans, and in China, apples [

72]. In the United States it is damaging to apples, peaches, tomatoes, peppers, squashes, cucumbers, sweet corn, soybeans, and beans [

73]. In Switzerland, economically important damage were recorded in bell pepper crops in 2012 [

74], and major damage were recorded in pears and other fruits in Italy [

75]. In Serbia, damage were observed on hazelnuts, soybeans, cherries, apricots, nectarines, apples and blueberries. Infested fruits are deformed and have white spots, which soon develop into necrotic spots, leading to a rapid decline in the commercial value of the fruit, often resulting in complete destruction. Ornamental plants, which are usually excluded from any type of control program, serve as host plants where population growth is usually undisturbed, and from which specimens spread and infest crop plants. The main urban hosts are Catalpa and newly planted Paulownia trees, which serve as hosts for both adults and nymphs.

In addition, this species is important in urban areas, where adults overwinter in sheltered areas under the bark of woody plants (especially sycamore trees, Konjević, unpublished data), but also in houses, apartments, and other buildings in urban and semi-urban areas, where they escape the adverse effects of low temperatures and frost. Adults are sometimes found in large numbers in weekend houses, restaurants in green areas, and in areas near forests (

Figure 5). With their unpleasant odour released when the specimens are disturbed, the species become very unwelcome guest soon after the appearance.

4.3. First record in Serbia

Halyomorpha halys was first detected in a photo published on social media from the Serbian-Romanian border, and shortly after, adult specimens were collected in two cities, Vršac and Belgrade, in October 2015 [

76]. Thereafter, a rapid spread of the population was observed and the number of host plants increased from urban plants to agricultural crops [

61].

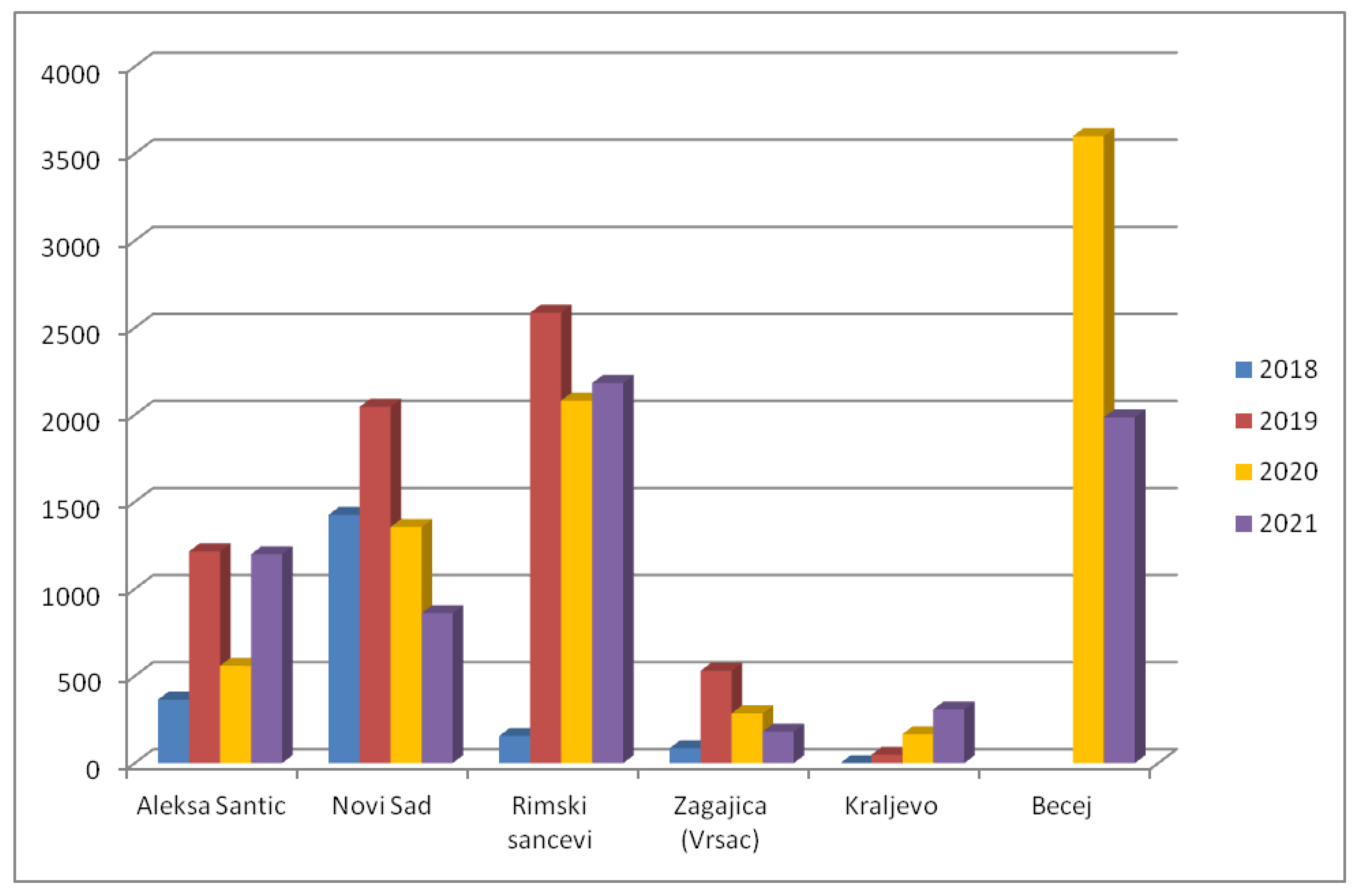

4.4. Monitoring

Monitoring of BMSB was initiated in 2016, and conducted by the pyramid dead-in traps (AgBio Company) using aggregation pheromone (Tréce lures) placed both in urban and agricultural areas. The number of traps per country was increased each year, and in 2022 there were 42 traps set. Traps were checked every week from May to the end of September each year. Since the beginning of trapping, five traps were set it the same place. The results showed the continuous spread of the species throughout the country, and also the expansion of the population at most trapping sites (

Figure 6).

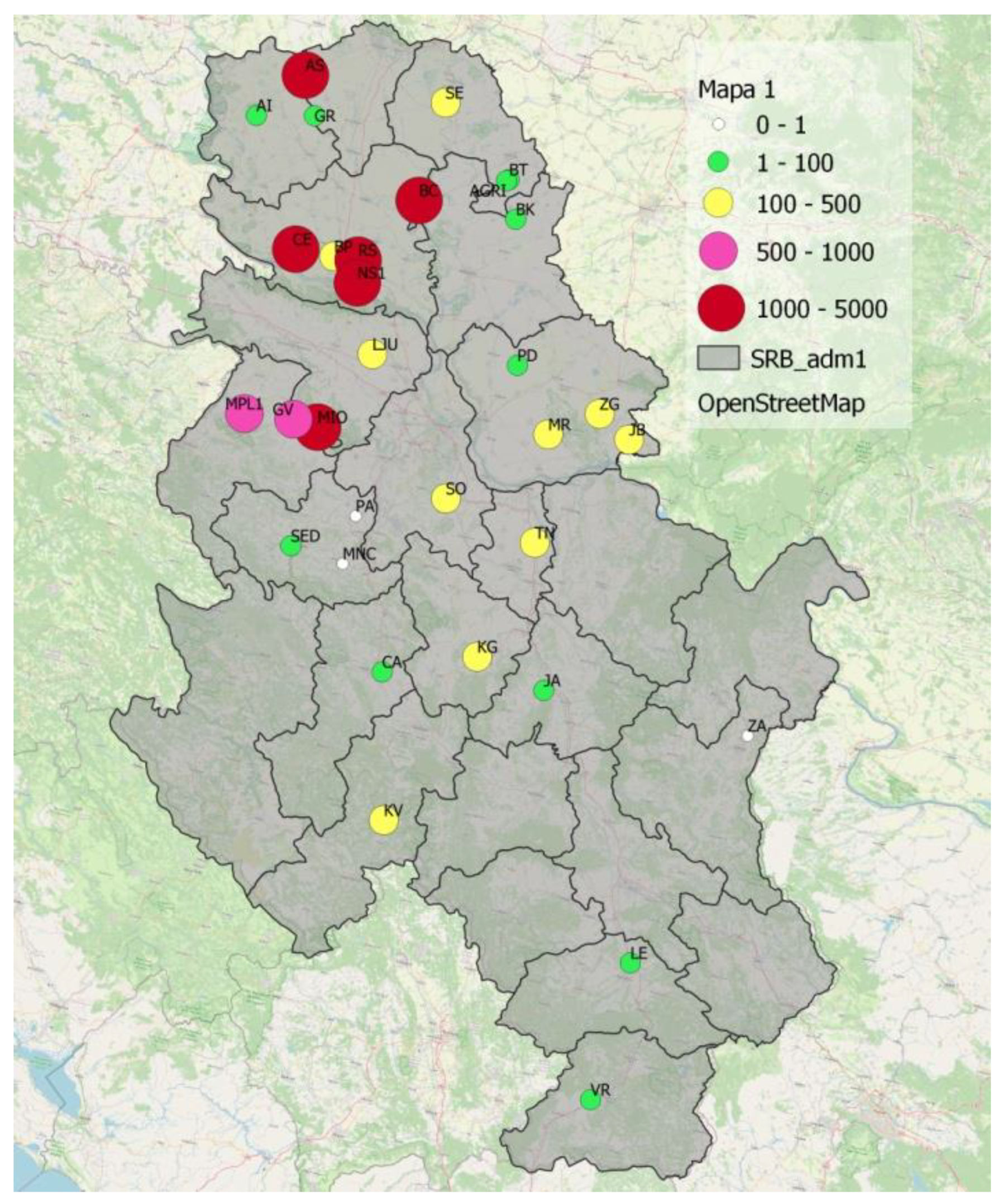

4.5. Distribution

Today, the BMSB is considered as well established species in Serbia, with increasing economic impact on agricultural production. In 2021, a total of 14,361 specimens were collected by traps, which was more than the total number of 11,214 specimens in the previous year. The distribution of specimens is not uniform across the country (

Figure 7), which is due to the different distribution of the favourable host plants and different environmental conditions (e.g. altitude, rainfall, solar radiation).

4.6. Applied control measures

The methods of controlling BMSB in Serbia are still based on the application of broad-spectrum insecticides, primarily a series of pyrethroids, carbamates, and neonicotinoids, which are usually not sufficiently effective. Chemical treatments are carried out by growers who typically respond with an increased number of insecticide applications. The main problem in control is the uneven action of individual growers, which leads to the movement of specimens from untreated to treated fields, which implies the need for new treatments. There is no treatment in urban areas. Current research is focused on native or alien natural enemies on the territory of Serbia that could be effective in biological control.

5. Nezara viridula (Linnaeus, 1758), Southern Green Stink Bug (Hemiptera, Pentatomidae)

5.1. Success in dispersal

This species of uncertain geographic origin, most likely from East Africa and the Mediterranean region [

62], is currently distributed in tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Eurasia, North and South America, and Australia [

62]. Some authors suggested that the species has spread through human activities [

77]. However, adults of

N. viridula are strong fliers and their dispersal is usually rapid. The species exhibit marked polymorphism. Freeman [

78] described four different colour variants, and Yukava & Kiritani listed five more [

79,

80]. According to later authors, polymorphism is defined to be necessary for range expansion and the survival. A cryptic green body in summer and a brown one before winter is a good camouflage strategy.

5.2. Significance

It is also a very unpleasant species whose adults can be numerous in urban areas, and disturb people in resting and residential areas during the winter diapause. Similar to the BMSB it releases an unpleasant odor when disturbed, and can be numerous in houses. In addition to this nuisance factor, the species is a pest of many horticultural and field crops, including more than 30 plant families [

81]. Adults and nymphs feed by sucking plant juices, concentrating primarily on fruits that are deformed and have low market value. Control of

N. viridula, as well as

H. halys, relies on a wide spectrum of insecticides, many of which are harmful to beneficial insects and are restricted for use in residential areas.

5.3. First record in Serbia

The southern green stink bug, also known as the green vegetable stink bug in Serbia, was first detected in Novi Sad and its surroundings in 2008 and 2009 [

82,

83]. There is no indication of the route by which it entered Serbia, other than the assumption that it was introduced by some transport, similar to the BMSB. The first mass occurrence of this species was recorded in September 2011 in several locations around Novi Sad and Sombor [

83]. Since then, it has spread throughout the country, and is now considered one of the most common and numerous species in vegetable crops.

5.4. Monitoring

To date, N. viridula has not been systematically monitored in Serbia. The species is monitored only by visual inspection of its occurrence in various crops and urban areas. It is often found in dead-in traps together with BMSB, but we cannot rely on this number, due to the species-specific pheromone in the mentioned traps. The two species are found in similar places, suggesting similar biology and overwintering preference.

5.5. Distribution

As mentioned above, N. viridula is present and established throughout the country, increasing in regions where more vegetables are grown, such as the northern part of Serbia, Vojvodina, but also in the southern parts, Leskovac and Vranje municipalities, where peppers and tomatoes are the dominant crops. Hidden dark places, where H. halys is abundant, also serve as good shelters for N. viridula. Garden plots and farms, as well as green areas with favourable ornamental plants, are the main reservoirs for specimens, which under suitable conditions are uncontrolled and abundant in such areas. Spread to larger arable areas, where they cause considerable damage, is inevitable under these conditions.

5.6. Applied control measures

As mentioned earlier for BMSB, the control of N. viridula also relies mainly on foliar applications of broad-spectrum synthetic chemicals to reduce pest damage. Having a negative non-target effect, the application of insecticides should be carried out on the basis of monitoring data, which are usually ignored. Therefore, growers still lack effective ways to control N. viridula. The current research focus is on natural enemies and their effectiveness.

6. Conclusions

Changes in land use, particularly urbanization and global warming, could further increase the competitive advantage of

Ae. albopictus and

Ae. japonicus over native mosquitoes through the use of artificial container habitats and further establishment in new areas [

84]. Winter temperatures and annual average temperatures appear to be the most important limiting factors for the spread of invasive mosquitoes in Europe [

85]. At this stage populations are wide spread in Serbia, it is almost impossible to consider their eradication. However, all effective measures offered by integrated mosquito management must be considered to suppress and keep mosquito populations low to prevent future outbreaks.

Stink bug control measures in almost every country rely mainly on insecticides, many of which affect natural enemies and possibly present parasites, which is a limitation for effective control strategies. A promising species selection tool could be the use of an alien parasitoid species that would reduce stink bug populations not only in agricultural areas but also in urban areas. A good example is Italy, where two egg parasitoids have been discovered and tested under natural conditions,

Trissolcus japonicus (Ashmead) and

T. mitsukurii (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) [

86,

87]. Control measures in urban areas, where stink bugs disturb people by their numbers, unpleasant odours, and disoriented flying, are very often neglected or difficult to implement. Therefore, natural enemies should be considered and used as the most effective methods to control these agricultural and urban pests.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work: MK, DP, AIC conducted monitoring of mosquito species and wrote the manuscript, AK conducted research and wrote the manuscript part about stink bugs. MK, DP, AIC made mosquito distribution maps. Map and graphs about stink bugs were done by AK. MK and AK contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Funding

Research was supported by Secretariat for Urbanism and Environment Protection of Vojvodina Province and Loznica Municipality, for monitoring of invasive mosquito species. Stink bugs research was supported by the Plant Protection Directorate of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management of the Republic of Serbia and Agriserbia d.o.o. The study was also supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia (project number 451-03-47/2023-01/200117).

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank to all technicians for field work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- European Centre for Disease Prevention Control, E.C.D.C. The climatic suitability for dengue transmission in continental Europe; ECDC: Stockholm, 2012a. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Guidelines for the surveillance of invasive mosquitoes in Europe, ECDC: Stockholm, 2012b. Available online: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/TER-Mosquitosurveillance-guidelines.pdf.

- Grandadam, M.; Caro, V.; Plumet, S.; Thiberge, J.M.; Souarès, Y.; Failloux, A.B.; Tolou, H.J.; Budelot, M.; Cosserat, D.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; Desprès, P. Chikungunya virus, southeastern France. Emerging infectious diseases 2011, 17, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haye, T.; Wyniger, D.; Gariepy, T. Recent range expansion of brown marmorated stink bug in Europe. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Urban Pests, Zurich, Switzerland (pp. 309-314). Executive Committee of the International Conference on Urban Pests (20-23 July 2014).

- Konjević, A. First records of the brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855)(Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in Republic of North Macedonia. Acta Zoologica Bulgarica 2020, 72, 687–690. [Google Scholar]

- Adhami, J.; Reiter, P. Introduction and establishment of Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus skuse (Diptera: Culicidae) in Albania. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 1998, 14, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sabatini, A.; Raineri, V.; Trovato, G.; Coluzzi, M. Aedes albopictus in Italy and possible diffusion of the species into the Mediterranean area. Parassitologia 1990, 32, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paupy, C.; Delatte, H.; Bagny, L.; Corbel, V.; Fontenille, D. Aedes albopictus, an arbovirus vector: from the darkness to the light. Microbes and infection 2009, 11, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Invasive Species Specialist Group, I.S.S.G. Global Invasive Species Database – Aedes albopictus 2009. Available online: http://www.issg.org/database/species/ecology.asp?si=109&fr=1&sts=sss&lang=EN.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention Control, E.C.D.C. Development of Aedes albopictus risk maps; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, E.A.; Higgs, S. Impact of climate change and other factors on emerging arbovirus diseases. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2009, 103, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer, M.U.; Sinka, M.E.; Duda, K.A.; Mylne, A.Q.; Shearer, F.M.; Barker, C.M.; Moore, C.G.; Carvalho, R.G.; Coelho, G.E.; Van Bortel, W.; Hendrickx, G. The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus. Elife 2015, 4, e08347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turell, M.J.; Dohm, D.J.; Sardelis, M.R.; O’guinn, M.L.; Andreadis, T.G.; Blow, J.A. An update on the potential of North American mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) to transmit West Nile virus. Journal of medical entomology 2005, 42, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eritja, R.; Escosa, R.; Lucientes, J.; Marques, E.; Roiz, D.; Ruiz, S. Worldwide invasion of vector mosquitoes: present European distribution and challenges for Spain. Biological invasions 2005, 7, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, M.Q.; Levine, R.S.; Hawley, W.A.; Lounibos, L.P. Spread of the tiger: global risk of invasion by the mosquito Aedes albopictus. Vector-borne and zoonotic Diseases 2007, 7, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffner, F.; Chouin, S.; Guilloteau, J. First record of Ochlerotatus (Finlaya) japonicus japonicus (Theobald, 1901) in metropolitan France. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 2003, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Medlock, J.M.; Hansford, K.M.; Versteirt, V.; Cull, B.; Kampen, H.; Fontenille, D.; Hendrickx, G.; Zeller, H.; Van Bortel, W.; Schaffner, F. An entomological review of invasive mosquitoes in Europe. Bulletin of entomological research 2015, 105, 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrović, V.; Turkulov, V.; Ilić, S.; Milošević, V.; Petrović, M.; Petrić, D.; Potkonjak, A. First report of imported case of dengue fever in Republic of Serbia. Travel medicine and infectious disease 2016, 1, 60–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petric, D. Monitoring of invasive vector mosquitoes and vectorborne diseases. Report to Administration for Environmental Protection 2009, Novi Sad City, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, K.; Mizusawa, K.; Saugstad, E.S. A revision of the adult and larval mosquitoes of Japan (including the Ryukyu Archipelago and the Ogasawara Islands) and Korea (Diptera: Culicidae). ARMY MEDICAL LAB PACIFIC APO SAN FRANCISCO 1979, 96343. [Google Scholar]

- Versteirt, V.; Schaffner, F.; Garros, C.; Dekoninck, W.; Coosemans, M.; Van Bortel, W. Introduction and establishment of the exotic mosquito species Aedes japonicus japonicus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Belgium. Journal of Medical Entomology 2009, 46, 1464–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffner, F.; Kaufmann, C.; Hegglin, D.; Mathis, A. The invasive mosquito Aedes japonicus in Central Europe. Medical and veterinary entomology 2009, 23, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, B.; Duh, D.; Nowotny, N.; Allerberger, F. First record of the mosquitoes Aedes (Ochlerotatus) japonicus japonicus (Theobald, 1901) in Austria and Slovenia 2011 and for Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse, 1895) in Austria. Entomol Zeitschr 2012, 122, 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez-Justicia, A.; Kampen, H.; Braks, M.; Schaffner, F.; Steeghs, M.; Werner, D.; Zielke, D.; Den Hartog, W.; Brooks, M.; Dik, M.; van de Vossenberg, B. First report of established population of Aedes japonicus japonicus (Theobald, 1901)(Diptera, Culicidae) in the Netherlands. J Eur Mosq Control Assoc 2014, 32, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Klobučar, A.; Lipovac, I.; Žagar, N.; Mitrović-Hamzić, S.; Tešić, V.; Vilibić-Čavlek, T.; Merdić, E. First record and spreading of the invasive mosquito Aedes japonicus japonicus (Theobald, 1901) in Croatia. Medical and veterinary entomology 2019, 33, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, B.; Montarsi, F.; Huemer, H.P.; Indra, A.; Capelli, G.; Allerberger, F.; Nowotny, N. First record of the Asian bush mosquito, Aedes japonicus japonicus, in Italy: invasion from an established Austrian population. Parasites & vectors 2016, 9, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eritja, R.; Ruiz-Arrondo, I.; Delacour-Estrella, S.; Schaffner, F.; Álvarez-Chachero, J.; Bengoa, M.; Puig, M.Á.; Melero-Alcíbar, R.; Oltra, A.; Bartumeus, F. First detection of Aedes japonicus in Spain: an unexpected finding triggered by citizen science. Parasites & vectors 2019, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffner, F.; Ries, C. First evidence and distribution of the invasive alien mosquito Aedes japonicus (Theobald, 1901) in Luxembourg. Bull Soc Nat Luxemb 2019, 121, 169–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kavran, M.; Lučić, D.; Ignjatović-Ćupina, A.; Zgomba, M.; Petrić, D. The first record of Aedes japonicus in Posavina region, Bosnia and Herzegovina. In E-SOVE, European Society for Vector Ecology Conference, Palermo, Italy, 2018 (pp. 22-26).

- Kavran, M.; Ignjatović-Ćupina, A.; Zgomba, M.; Žunić, A.; Bogdanović, S.; Srdić, V.; .. & Petrić, D. Invasive mosquito surveillance and the first record of Aedes japonicus in Serbia. In IXth International EMCA Conference, 2019 (pp. 10-14).

- Horváth, C.; Cazan, C.D.; Mihalca, A.D. Emergence of the invasive Asian bush mosquito, Aedes (Finlaya) japonicus japonicus, in an urban area, Romania. Parasites & vectors 2021, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Vojtíšek, J.; Janssen, N.; Šikutová, S.; Šebesta, O.; Kampen, H.; Rudolf, I. Emergence of the invasive Asian bush mosquito Aedes (Hulecoeteomyia) japonicus (Theobald, 1901) in the Czech Republic. Parasites & Vectors 2022, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, N.; Huber, K.; Pluskota, B.; Kaiser, A. Ochlerotatus japonicus japonicus–a newly established neozoan in Germany and a revised list of the German mosquito fauna. Eur Mosq Bull 2011, 29, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, M.G.; Stanuszek, W.W.; Brouhard, E.A.; Knepper, R.G.; Walker, E.D. Establishment of Aedes japonicus japonicus and its colonization of container habitats in Michigan. Journal of medical entomology 2014, 49, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, D.M.; Campbell, S.; Crans, W.J.; Mogi, M.; Miyagi, I.; Toma, T.; Bullians, M.; Andreadis, T.G.; Berry, R.L.; Pagac, B.; Sardelis, M.R. Aedes (Finlaya) japonicus (Diptera: Culicidae), a newly recognized mosquito in the United States: analyses of genetic variation in the United States and putative source populations. Journal of Medical Entomology 2001, 38, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreadis, T.G.; Anderson, J.F.; Munstermann, L.E.; Wolfe, R.J.; Florin, D.A. Discovery, distribution, and abundance of the newly introduced mosquito Ochlerotatus japonicus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Connecticut, USA. Journal of Medical Entomology 2001, 38, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, K.L. Contributions to the mosquito fauna of Southeast Asia IV: species of the subgroup chrysolineatus of group D, genus Aedes, subgenus Finlaya Theobald. American Entomological Institute 1968.

- Kamimura, K. The distribution and habit of medically important mosquitoes of Japan. Japanese Journal of Sanitary Zoology 1968, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sardelis, M.R.; Dohm, D.J.; Pagac, B.; Andre, R.G.; Turell, M.J. Experimental transmission of eastern equine encephalitis virus by Ochlerotatus j. japonicus (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of Medical Entomology 2002, 39, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardelis, M.R.; Turell, M.J.; Andre, R.G. Laboratory transmission of La Crosse virus by Ochlerotatus j. japonicus (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of Medical Entomology 2002, 39, 635–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardelis, M.R.; Turell, M.J.; Andre, R.G. Experimental transmission of St. Louis encephalitis virus by Ochlerotatus j. japonicus. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 2003, 19, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sardelis, M.R.; Turell, M.J. Ochlerotatus j. japonicus in Frederick County, Maryland: discovery, distribution, and vector competence for West Nile virus. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association-Mosquito News 2001, 17, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Takashima, I.; Rosen, L. Horizontal and vertical transmission of Japanese encephalitis virus by Aedes japonicus (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of medical entomology 1989, 26, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffner, F.; Vazeille, M.; Kaufmann, C.; Failloux, A.B.; Mathis, A. Vector competence of Aedes japonicus for Chikungunya and dengue viruses. Journal of the European Mosquito Control Association 2011, 29, 141–142. [Google Scholar]

- Turell, M.J.; Byrd, B.D.; Harrison, B.A. Potential for Populations of Aedes j. japonicus to Transmit Rift Valley Fever Virus in the USA1. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 2013, 29, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josifov, M.; IM., K. Heteroptera Aus Korea. Ii. Aradidae, Berytidae, Lygaeidae, Pyrrhocoridae, Rhopalidae, Alydidae, Coreidae, Urostylidae, Acanthosomatidae, Sautelleridae, Pentatomidae, Cydnidae, Plataspidae, 1978.

- Hoebeke, E.R.; Carter, M.E. Halyomorpha halys (Stål)(Heteroptera: Pentatomidae): a polyphagous plant pest from Asia newly detected in North America. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 2003, 105, 225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, K. Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855), eine für die europäische fauna neu nachgewiesene wanzenart (Insecta: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae: Cappaeini). Mitteilungen des Thüringer Entomologenverbandes 2009, 16, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Wermelinger BE, A.T.; Wyniger, D.; Forster BE, A.T. First records of an invasive bug in Europe: Halyomorpha halys Stal (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae), a new pest on woody ornamentals and fruit trees? Mitteilungen-Schweizerische Entomologische Gesellschaft 2008, 81, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann RA, L.F. Erster nachweis von Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855)(Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) für deutschland. Heteropteron 2012, 36, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Callot, H.; Brua, C. Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855), la Punaise diabolique, nouvelle espèce pour la faune de France (Heteroptera Pentatomidae). L’Entomologiste 2013, 69, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Maistrello, L.; Dioli, P.; Vaccari, G.; Nannini, R.; Bortolotti, P.; Caruso, S.; Costi, E.; Montermini, A.; Casoli, L.; Bariselli, M. Primi rinvenimenti in Italia della cimice esotica Halyomorpha halys, una nuova minaccia per la frutticoltura. ATTI Giornate fitopatologiche 2014, 1, 283–288. [Google Scholar]

- Vetek, G.; Papp, V.; Haltrich, A.; Rédei, D. First record of the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae), in Hungary, with description of the genitalia of both sexes. Zootaxa 2014, 3780, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabitsch, W.; Friebe, G.J. From the west and from the east? First records of Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855)(Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) in Vorarlberg and Vienna, Austria. Beiträge zur Entomofaunistik 2015, 16, 115–139. [Google Scholar]

- Macavei, L.I.; Băețan, R.; Oltean, I.; Florian, T.; Varga, M.; Costi, E.; Maistrello, L. First detection of Halyomorpha halys Stål, a new invasive species with a high potential of damage on agricultural crops in Romania. Lucrări Ştiinţifice 2015, 58, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Milonas, P.G.; Partsinevelos, G.K. First report of brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys Stål (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in Greece. EPPO Bulletin 2014, 44, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioli, P.; Leo, P.; Maistrello, L. Prime segnalazioni in Spagna e in Sardegna della specie aliena Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) e note sulla sua distribuzione in Europa (Hemiptera, Pentatomidae). Revista gaditana de Entomología 2016, 7, 539–548. [Google Scholar]

- Simov, N. The invasive brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855)(Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) already in Bulgaria. Ecologica Montenegrina 2016, 9, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gapon, D.A. First records of the brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855)(Heteroptera, Pentatomidae) in Russia, Abkhazia, and Georgia. Entomological Review 2016, 96, 1086–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mityushev, I.M. First record of Halymorpha halys detection in Russia. Zashchita i Karantin Rasteniĭ 2016, 48 (in Russian).

- Musolin, D.L.; Konjević, A.; Karpun, N.N.; Protsenko, V.Y.; Ayba, L.Y.; Saulich, A.K. Invasive brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys (Stål)(Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) in Russia, Abkhazia, and Serbia: history of invasion, range expansion, early stages of establishment, and first records of damage to local crops. Arthropod-Plant Interactions 2018, 12, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemala, V.; Kment, P. First record of Halyomorpha halys and mass occurrence of Nezara viridula in Slovakia (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Plant Protection Science 2017, 53, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rot, M.; Devetak, M.; Carlevaris, B.; Žežlina, J.; Žežlina, I. First record of brown marmorated stink bug (Halyomorpha halys Stål, 1855)(Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in Slovenia. Acta entomologica slovenica 2018, 26, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Šapina, I.; Jelaska, L.Š. First report of invasive brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) in Croatia. EPPO Bulletin 2018, 48, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zovko, M.; Ostojić, I.; Jurković, D.; Karić, N. First report of the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Radovi Poljoprivredno Prehrambenog Fakulteta Univerziteta u Sarajevu\Works of the Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences University of Sarajevo 2019, 64, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- EPPO 2019. First reports of Halyomorpha halys in Belgium, Bulgaria and in Malta and update for other European countries. EPPO Reporting Service 06: article 117. a.

- Gariepy, T.D.; Haye, T.; Fraser, H.; Zhang, J. Occurrence, genetic diversity, and potential pathways of entry of Halyomorpha halys in newly invaded areas of Canada and Switzerland. Journal of pest science 2014, 87, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiman, N.G.; Walton, V.M.; Shearer, P.W.; Rondon, S.I.; Lee, J.C. Factors affecting flight capacity of brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). Journal of pest science 2015, 88, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriticos, D.J.; Kean, J.M.; Phillips, C.B.; Senay, S.D.; Acosta, H.; Haye, T. The potential global distribution of the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys, a critical threat to plant biosecurity. Journal of Pest Science 2017, 90, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Studies on the pear bug, Halyomorpha picus. Acta Agric. Bor-Sin 1988, 3, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Chung, B.; Kim, T.; Kwon, J.; Song, W.; Rho, C. Damage of sweet persimmon fruit by the inoculation date and number of stink bugs, Riptortus clavatus, Halyomorpha halys and Plautia stali. Korean Journal of Applied Entomology 2009, 48, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funayama, K. Control effect on the brown-marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae), by combined spraying of pyrethroid and neonicotinoid insecticides in apple orchards in northern Japan. Applied entomology and zoology 2012, 47, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskey, T. Emergence of Brown Marmorated Stink Bug, Halyomorpha halys (Stål), as a Serious Pest of Agriculture 2012. Available online: https://archive.epa.gov/ pesticides/biopesticides/ web/pdf/leskey-epa-nafta-workshop.

- Sauer, C. The Marbled tree bug occurs again on the Deutschschweizer Gemusebau. Die Marmorierte Baumwanze tritt neu im Deutschschweizer Gemüsebau auf.) Extension Gemüsebau, Forschungsanstalt Agroscope Changins-Wädenswil, Gemüsebau Info 2012, 28, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Maistrello, L.; Vaccari, G.; Caruso, S.; Costi, E.; Bortolini, S.; Macavei, L.; Foca, G.; Ulrici, A.; Bortolotti, P.P.; Nannini, R.; Casoli, L. Monitoring of the invasive Halyomorpha halys, a new key pest of fruit orchards in northern Italy. Journal of Pest Science 2017, 90, 1231–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šeat, J. Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855)(Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) a new invasive species in Serbia. Acta entomologica serbica 2015, 20, 167–171. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, K.M.; Gurr, G.M. Review of Nezara viridula (L.) management strategies and potential for IPM in field crops with emphasis on Australia. Crop Protection 2007, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, P. A contribution to the study of the genus Nezara AMYOT and SERVILLE (Hemiptera, Pentatomidae). Trans. R. Entomol. Soc. Lond 1940, 80, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukawa, J.; K Kiritani. Polymorphism in the southern green stink bug. Pacific Insects 1965, 7, 639–642. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, K.; Alam, M.Z. Hereditary basis of adult color polymorphism in the southern green stink bug, Nezara viridula Linné (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Applied Entomology and Zoology 1992, 27, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.W. Ecology and behavior of Nezara viridula. Annual review of entomology 1989, 34, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protić, LJ. New Heteroptera for the fauna of Serbia. Bulletin of the Natural History Museum 2011, 4, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kereši, T.; Sekulić, R.; Protić, L.; Milovac, Ž. Occurrence of Nezara viridula L.(Heteroptera: pentatomidae) in Serbia. Biljni lekar 2012, 40, 296–304, [in Serbian, summary in English]. [Google Scholar]

- Leisnham, P.T.; Juliano, S.A. Impacts of climate, land use, and biological invasion on the ecology of immature Aedes mosquitoes: implications for La Crosse emergence. Ecohealth 2012, 9, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roiz, D.; Neteler, M.; Castellani, C.; Arnoldi, D.; Rizzoli, A. Climatic factors driving invasion of the tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) into new areas of Trentino, northern Italy. PloS one 2011, 6, e14800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaccini, D.; Falagiarda, M.; Tortorici, F.; Martinez-Sañudo, I.; Tirello, P.; Reyes-Domínguez, Y.; Pozzebon, A. An insight into the role of Trissolcus mitsukurii as biological control agent of Halyomorpha halys in Northeastern Italy. Insects 2020, 11, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapponi, L.; Tortorici, F.; Anfora, G.; Bardella, S.; Bariselli, M.; Benvenuto, L.; Bernardinelli, I.; Butturini, A.; Caruso, S.; Colla, R.; Costi, E. Assessing the distribution of exotic egg parasitoids of Halyomorpha halys in Europe with a large-scale monitoring program. Insects 2021, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).