Submitted:

05 June 2023

Posted:

06 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

The economic costs of air pollution and its impact on human health

Sustainable consumption behavior

Materials and Methods

Results discussion

Description of samples

Theoretical modelling

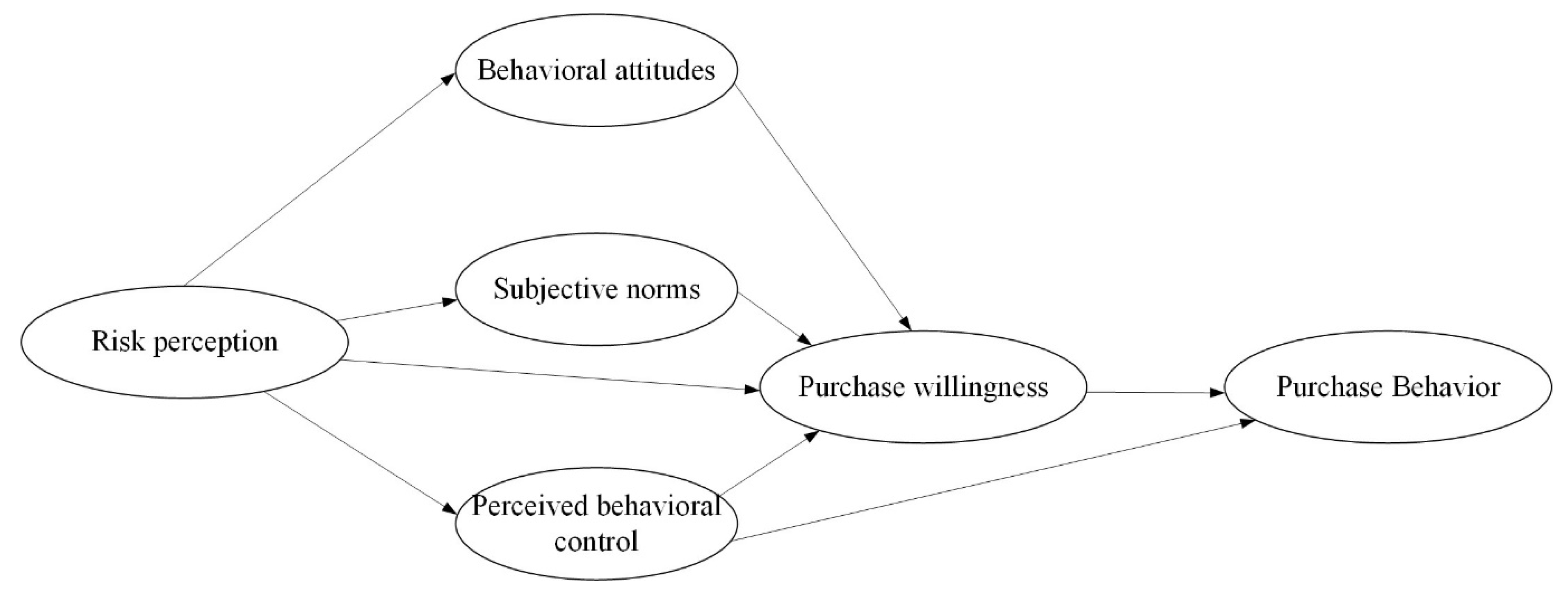

- H1: Perception of health risk has a significant positive effect on purchase willingness;

- H2: Behavioral attitude plays a significant mediating role between risk perception and purchase willingness;

- H3: Subjective norms play a significant mediating role between risk perception and purchase willingness;

- H4: Perception of behavioral control plays a significant mediating role between perception of health risk and purchase willingness;

- H5: Perception of behavioral control plays a significant mediating role between perception of health risk and purchase behavior;

- H6: Purchase willingness has a significant positive effect on purchase behavior;

Model analysis

Heterogeneity analysis

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. 2019 China Ecological Environment Status Bulletin. http://www.cnemc.cn/jcbg/zghjzkgb/202007/P020200716568022848361.pdf.

- Hu, F. & Guo, Y. Health impacts of air pollution in China. Front. Environ. Sci. & Eng. 15, 74. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mackerron, G. & Mourato, S. Life satisfaction and air quality in London. Ecol. Econ. 68, 1441–1453. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. China Mobile Source Environmental Management Annual Report (2020). http://www.mee.gov.cn/hjzl/sthjzk/ydyhjgl/202008/P020200811521365906550.pdf.

- Zou, C. et al. The role of new energy in carbon neutral. PETROLEUM EXPLORATION AND DEVELOPMENT 48, 411–420. 2021.

- Zhang, J. et al. Environmental health in China: progress towards clean air and safe water. The Lancet 375, 1110–1119. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Yu, F. et al. Review on studies of environmental impact on health from air pollution in China. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 93, 2695–2698. 2013.

- Lin, H., Wang, X., Tao, L., Xing, L. & Ma, W. Air pollution and mortality in china. Adv. Exp. Medicine Biol. 1017, 103–121. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y., Chen, R. & Kan, H. Air pollution, disease burden, and health economic loss in china. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol. 1017, 233–242. 2017. [CrossRef]

- González-Díaz, S., Arias-Cruz, A., Macouzet-Sánchez, C. & , A. P.-O. Impact of air pollution in respiratory allergic diseases. Medicina Univ. 18, 212–215. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Air pollution. https://www.who.int/health-topics/air-pollution#tab=tab_1.

- Guan, W. J., Zheng, X. Y., Chung, K. F. & Zhong, N. S. Impact of air pollution on the burden of chronic respiratory diseases in China: time for urgent action. Lancet (London, England) 388, 1939. 1939. [CrossRef]

- Air Pollution Deaths Cost Global Economy US$225 Billion.

- Mu, Q. & Zhang, S.-Q. An evaluation of the economic loss due to the heavy haze during january 2013 in china. Zhongguo Huanjing Kexue/China Environ. Sci. 33, 2087–2094 (2013).

- Caniëls, M. C. J., Lambrechts, W., Platje, J. J., Motylska-Kuz´ma, A. & Fortun´ski, B. 50 Shades of Green: Insights into Personal Values and Worldviews as Drivers of Green Purchasing Intention, Behaviour, and Experience. Sustainability 13, 4140. 2021. [CrossRef]

- He, Z. et al. The impact of motivation, intention, and contextual factors on green purchasing behavior: New energy vehicles as an example. BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT 30, 1249–1269. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bratucu, G. et al. Acquisition of Electric Vehicles A Step towards Green Consumption. Empirical Research among Romanian Students. Sustainability 11, 6639. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Chen, S.-C. & Zhang, L. Promoting sustainable development: A research on residents’ green purchasing behavior from a perspective of the goal-framing theory. Sustain. Dev. 28, 1208–1219. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Awuni, J. A. & Du, J. Sustainable Consumption in Chinese Cities: Green Purchasing Intentions of Young Adults Based on the Theory of Consumption Values: Green Purchasing in Chinese Cities. Sustain. Dev. 24, 124–135. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Axsen, J., Orlebar, C. & Skippon, S. Social influence and consumer preference formation for pro-environmental technology: The case of a UK workplace electric-vehicle study. Ecol. Econ. 95, 96–107. WOS:000326776100010. 2013. [CrossRef]

- De Camillis, C. & Goralczyk, M. Towards stronger measures for sustainable consumption and production policies: proposal of a new fiscal framework based on a life cycle approach. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 18, 263–272. WOS:000313165600024. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Cerri, J., Testa, F. & Rizzi, F. The more I care, the less I will listen to you: How information, environmental concern and ethical production influence consumers’ attitudes and the purchasing of sustainable products. J. Clean. Prod. 175, 343–353. WOS:000423635500032. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Chan, R. Y. K. Determinants of Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. Psychol. & Mark. 18, 389–413. WOS:000167596400004. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M. F. Y. & To, W. M. An extended model of value-attitude-behavior to explain Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. J. Retail. Consumer Serv. 50, 145–153. WOS:000471928200017. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Corraliza, J. A. & Berenguer, J. Environmental values, beliefs, and actions - A situational approach. Environ. Behav. 32, 832–848. 2000. [CrossRef]

- Dagher, G. K. & Itani, O. Factors influencing green purchasing behaviour: Empirical evidence from the Lebanese consumers. J. Consumer Behav. 13, 188–195. WOS:000340382100004. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A., Schlegelmilch, B. B., Sinkovics, R. R. & Bohlen, G. M. Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. J. Bus. Res. 56, 465–480. WOS:000182643500005. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Dobson, A. Environmental citizenship: Towards sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 15, 276–285. WOS:000250932400002. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Doran, R. & Larsen, S. The Relative Importance of Social and Personal Norms in Explaining Intentions to Choose Eco-Friendly Travel Options. Int. J. Tour. Res. 18, 159–166. WOS:000371746000006. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E. & Fischbacher, U. Third-party punishment and social norms. Evol. Hum. Behav. 25, 63–87. WOS:000221036800001. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, C. Managing green complexities: consumers’ strategies and techniques for greener shopping. Int. J. Consumer Stud. 38, 485–492. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Wang, X. & Jiang, B. Structural Equation Models:Methods and Applications (Higher Education Press, 2011).

- Nordlund, A. M. & Garvill, J. Effects of values, problem awareness, and personal norm on willingness to reduce personal car use. J. Environ. Psychol. 23, 339–347. WOS:000186823100001. 2003. [CrossRef]

- ölander, F. & ThØgersen, J. Understanding of consumer behaviour as a prerequisite for environmental protection. J. Consumer Policy 18, 345–385. 1995. [CrossRef]

- Pagiaslis, A. & Krontalis, A. K. Green Consumption Behavior Antecedents: Environmental Concern, Knowledge, and Beliefs. Psychol. & Mark. 31, 335–348. WOS:000334017200003. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Pape, J., Rau, H., Fahy, F. & Davies, A. Developing Policies and Instruments for Sustainable Household Consumption: Irish Experiences and Futures. J. Consumer Policy 34, 25–42. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Sang, Y.-N. & Bekhet, H. A. Modelling electric vehicle usage intentions: an empirical study in Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod.

- 92, 75–83. WOS:000351649900008. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.-F., Chiang, C.-T., Kou, T.-C. & Lee, B. C. Y. Toward Sustainable Livelihoods: Investigating the Drivers of Purchase Behavior for Green Products. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 26, 626–639. WOS:000405389500005. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Aagerup, U. & Nilsson, J. Green consumer behavior: being good or seeming good? J. Prod. & Brand Manag. 25, 274–284. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Arli, D., Tan, L. P., Tjiptono, F. & Yang, L. Exploring consumers’ purchase intention towards green products in an emerging market: The role of consumers’ perceived readiness. Int. J. Consumer Stud. 42, 389–401. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Pawaskar, U. S., Raut, R. D. & Gardas, B. B. Assessment of Consumer Behavior Towards Environmental Responsibility: A Structural Equations Modeling Approach: Analyses the Elements of Environmental Responsibility of Consumer. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 27, 560–571. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Reimers, V., Magnuson, B. & Chao, F. Happiness, altruism and the Prius effect: How do they influence consumer attitudes towards environmentally responsible clothing? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. An Int. J. 21, 115–132. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K. M. & Vaithianathan, S. A fresh look at understanding Green consumer behavior among young urban Indian consumers through the lens of Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 183, 46–55. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.-h., Gao, Q., Wu, Y.-p., Wang, Y. & Zhu, X.-d. What affects green consumer behavior in China? A case study from Qingdao. J. Clean. Prod. 63, 143–151. 2014. [CrossRef]

- De Camillis, C. & Goralczyk, M. Towards stronger measures for sustainable consumption and production policies: proposal of a new fiscal framework based on a life cycle approach. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 18, 263–272. WOS:000313165600024. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Statistical of economic and social development of Kunming in 2019.

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. Bulletin on ecological environment of Kunming in 2019. http://www.km.gov.cn/c/2020-06-04/3567146.shtml.

- Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 236, 280–285. https://science.sciencemag. org/content/236/4799/280.full.pdf. 1987. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211. 1991. [CrossRef]

- Schilirò, D. Economics versus psychology. Risk, uncertainty and the expected utility theory. J. Math. Econ. Finance 1, 77–96. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Stommel, E. Reference-Dependent Preferences: A Theoretical and Experimental Investigation of Individual Reference-Point Formation (Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden, 2013).

- Shi, K. et al. The Risk Perceptions of SARS Socio-psychological Behaviors of Urban People in China. Acta Psychol. Sinica 546–554 (2003).

- Chéron, E. & Zins, M. Electric vehicle purchasing intentions: The concern over battery charge duration. Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Pract. 31, 235–243. 1997. [CrossRef]

| Health Risk Perception | Purchase new energy vehicle | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator Average | Standard deviation | Indicator Average Standard deviation | |||

| Knowledge of air pollution 3.1 | 0.89 | Willingness to purchase 3.08 1.07 | |||

| Air pollution impact level 3.76 | 0.86 | Whether have purchased a new energy vehicle 0.08 0.27 | |||

| Possibility of air pollution occurrence 3.73 | 0.9 | Risk reduction role 3.06 0.98 | |||

|

Severity of consequences Duration |

3.63 3.81 |

0.84 0.85 |

subsidies can reduce the cost of purchasing Family pressure |

a car 3.15 3.26 |

0.95 0.96 |

| Controllability | 2.78 | 0.91 | Friend pressure | 3.22 | 0.94 |

| Equality | 3.11 | 1.04 | Public media pressure | 3.36 | 0.92 |

| Perceptibility | 3.21 | 1.03 | Low battery time | 3.47 | 0.88 |

| Relevance to daily life | 3.83 | 0.96 | Availability of Charging Piles | 3.54 | 0.88 |

| Acceptability | 2.47 | 0.87 | |||

| Adaptability | 2.64 | 0.87 | |||

| Variables | Components 1 | Components 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of air pollution | 0.49 | -0.03 |

| Impacts of air pollution | 0.78 | -0.03 |

| Possibility of air pollution occurrence | 0.78 | -0.01 |

| Severity of consequences | 0.85 | -0.02 |

| Duration | 0.71 | -0.09 |

| Controllability | -0.01 | 0.71 |

| Equality | 0.27 | 0.47 |

| Perceptibility | 0.62 | 0.09 |

| Relevance to daily life | 0.79 | 0.07 |

| Acceptability | -0.54 | 0.35 |

| Adaptability | -0.43 | 0.56 |

| Explanation of variance (%) | 38.78 | 10.39 |

| Path | Non-standardized coefficient | Standard Error | P value | Standardized coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of health risk->risk impacts | 1 | 0.55 | ||

| Perception of health risk->Risk Controllability | -0.22 | 0.14 | 0.11 | -0.09 |

| Perception of health risk->Perception of behavioral control | 1.25 | 0.26 | 0.00*** | 0.67 |

| Perception of health risk->Subjective norms | 0.66 | 0.15 | 0.00*** | 0.55 |

| Perception of health risk->Behavioral attitudes | 0.93 | 0.19 | 0.00*** | 0.36 |

| Perception of health risk->Purchase willingness | 1.41 | 0.58 | 0.02** | 0.5 |

| Perception of behavioral control->Purchase willingness | -0.6 | 0.19 | 0.00*** | -0.39 |

| Subjective norms->Purchase willingness | 0.75 | 0.19 | 0.00*** | 0.31 |

| Behavioral attitudes->Purchase willingness | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.00*** | 0.24 |

| Purchase willingness->Purchase behavior | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00*** | 0.19 |

| Perception of behavioral control->Purchase behavior. | -0.03 | 0.02 | 0.08* | -0.08 |

| Path | Under BSc | BSc and above | Low income | High income |

| Perception of health risk->Risk impacts | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 1.12 |

| Perception of health risk->Risk Controllability | 0.1 | -0.14** | -0.13* | -0.07 |

| Perception of health risk->Perception of behavioral control | 0.51*** | 0.83*** | 0.72*** | 0.36 |

| Perception of health risk->Subjective norms | 0.72*** | 0.54*** | 0.66*** | 0.26 |

| Perception of health risk->Behavioral attitudes | 0.37** | 0.33*** | 0.39*** | 0.26 |

| Perception of health risk->Purchase willingness | 0.63** | 0.61** | 0.76** | 0.09 |

| Perception of behavioral control->Purchase willingness | -0.39** | -0.54*** | -0.52** | -0.13* |

| Subjective norms->Purchase willingness | 0.27 | 0.26*** | 0.19 | 0.40*** |

| Behavioral attitudes->Purchase willingness | 0.13 | 0.30*** | 0.18** | 0.36*** |

| Purchase willingness->Purchase behavior | 0.32*** | 0.12** | 0.11* | 0.25*** |

| Perception of behavioral control->Purchase behavior. | -0.16** | -0.03 | -0.06 | -0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).