Submitted:

05 June 2023

Posted:

05 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

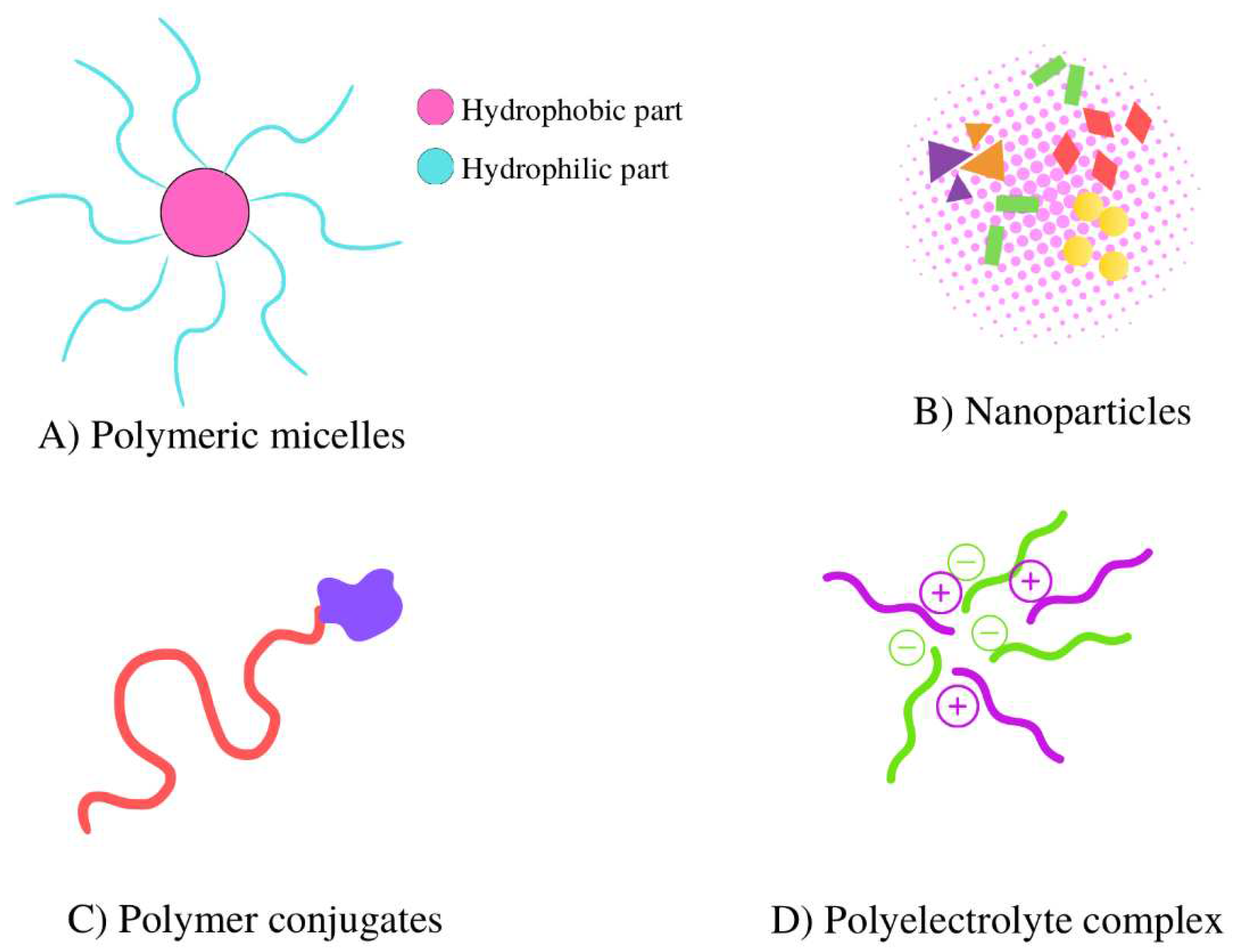

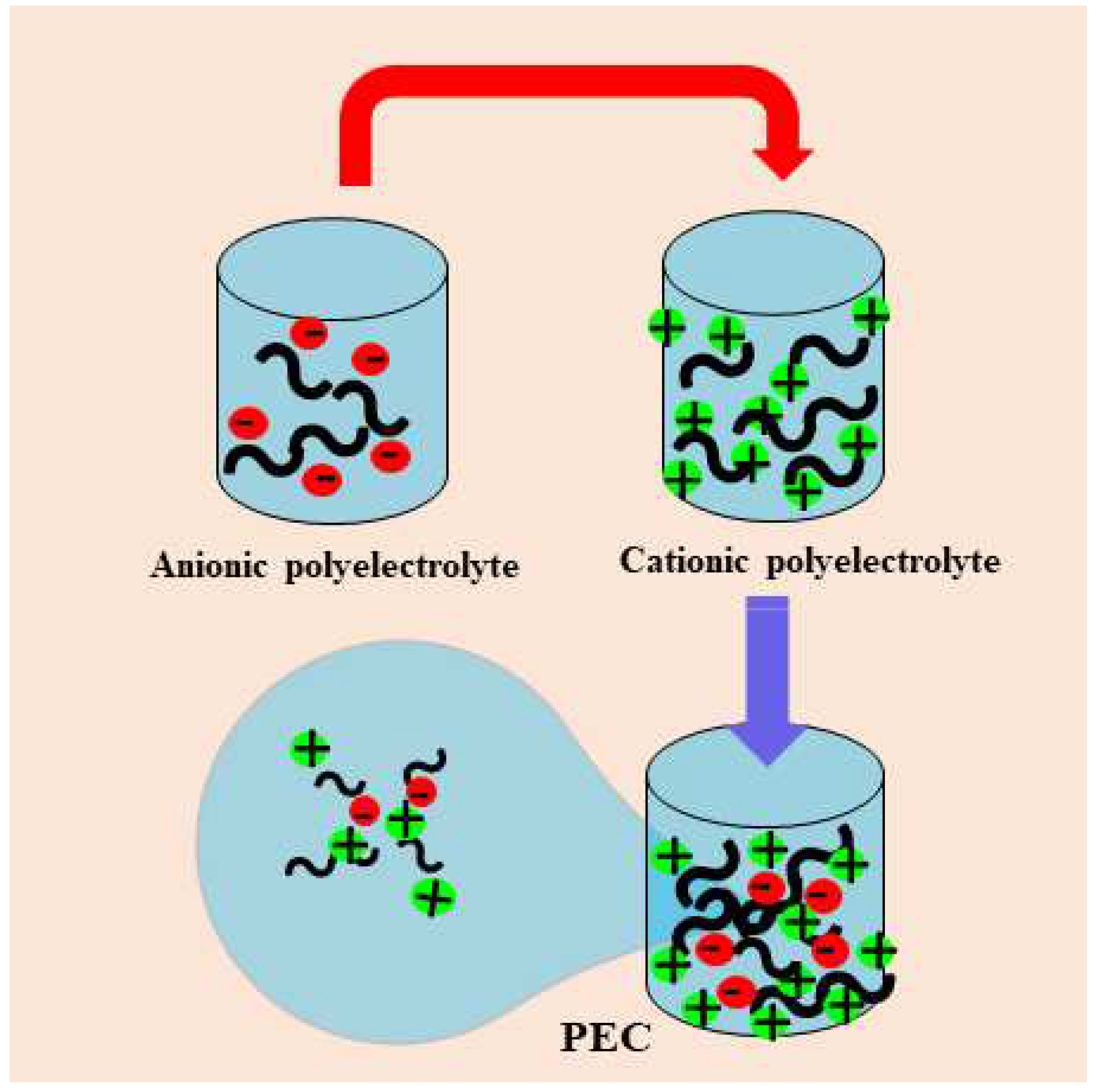

2. Polyelectrolyte complexes: a brief look

2.1. Polyelectrolyte complexes using biopolymers

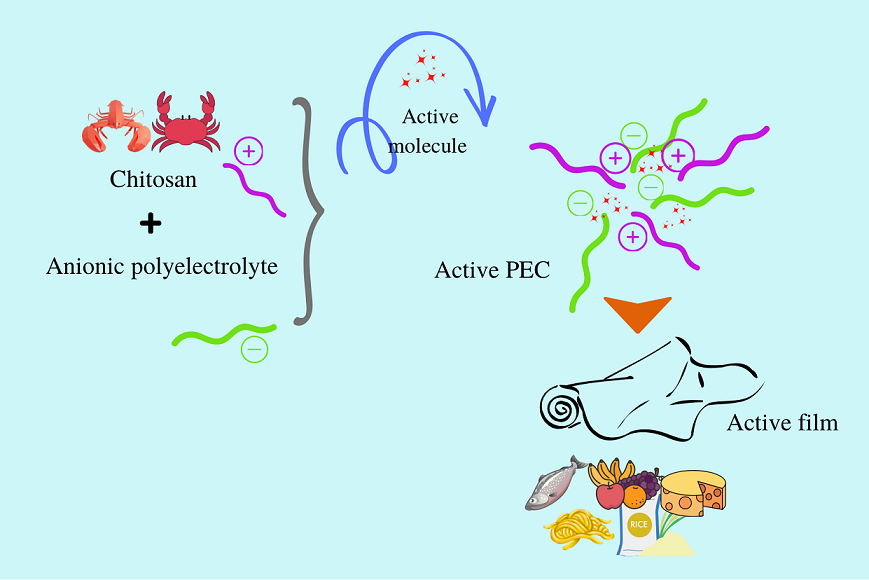

3. Active food packaging

3.1. Food packaging using polyelectrolyte complexes systems chitosan based

4. Overview

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO El estado mundial de la pesca y la acuicultura 2022. Hacia la transformación azul.; Rome, 2022; ISBN 0000000340472.

- Kumari, S.; Rath, P.; Sri Hari Kumar, A.; Tiwari, T.N. Extraction and characterization of chitin and chitosan from fishery waste by chemical method. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2015, 3, 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2015.01.002. [CrossRef]

- Shahid-ul-Islam; Butola, B.S. Recent advances in chitosan polysaccharide and its derivatives in antimicrobial modification of textile materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 905–912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.10.102. [CrossRef]

- Negm, N.A.; Hefni, H.H.H.; Abd-Elaal, A.A.A.; Badr, E.A.; Abou Kana, M.T.H. Advancement on modification of chitosan biopolymer and its potential applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 152, 681–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.196. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xue, C.; Mao, X. Chitosan: Structural modification, biological activity and application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 4532–4546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.09.042. [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Shafi, M.E.; Zabermawi, N.M.; Arif, M.; Batiha, G.E.; Khafaga, A.F.; Abd El-Hakim, Y.M.; Al-Sagheer, A.A. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of chitosan and its derivatives and their applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 2726–2744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.153. [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Meng, X.; Meng, J.; Khan, M.I.H.; Dai, L.; Khan, A.; An, X.; Zhang, J.; Huq, T.; Ni, Y. Chitosan as A Preservative for Fruits and Vegetables: A Review on Chemistry and Antimicrobial Properties. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2019, 4, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.21967/jbb.v4i1.189. [CrossRef]

- Ke, C.L.; Deng, F.S.; Chuang, C.Y.; Lin, C.H. Antimicrobial actions and applications of Chitosan. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13060904. [CrossRef]

- Flórez, M.; Guerra-Rodríguez, E.; Cazón, P.; Vázquez, M. Chitosan for food packaging: Recent advances in active and intelligent films. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124, 107328–107343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.107328. [CrossRef]

- Czajkowska-Kośnik, A.; Szekalska, M.; Winnicka, K. Nanostructured lipid carriers: A potential use for skin drug delivery systems. Pharmacol. Reports 2019, 71, 156–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharep.2018.10.008. [CrossRef]

- Ravindran Girija, A.; Balasubramanian, S.; Bright, R.; Cowin, A.J.; Goswami, N.; Vasilev, K. Ultrasmall Gold Nanocluster Based Antibacterial Nanoaggregates for Infectious Wound Healing. ChemNanoMat 2019, 5, 1176–1181. https://doi.org/10.1002/cnma.201900366. [CrossRef]

- Rengifo, A.F.C.; Santos, S.C.; de Lima, V.R.; Agudelo, A.J.P.; da Silva, L.H.M.; Parize, A.L.; Minatti, E. Aggregation behavior of self-assembled nanoparticles made from carboxymethyl-hexanoyl chitosan and sodium dodecyl sulphate surfactant in water. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 278, 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2018.12.125. [CrossRef]

- Rumyantsev, A.M.; Jackson, N.E.; De Pablo, J.J. Polyelectrolyte Complex Coacervates: Recent Developments and New Frontiers. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2021, 12, 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-042020-113457. [CrossRef]

- Gençdağ, E.; Özdemir, E.E.; Demirci, K.; Görgüç, A.; Yılmaz, F.M. Copigmentation and stabilization of anthocyanins using organic molecules and encapsulation techniques. Curr. Plant Biol. 2022, 29, 100238–100248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpb.2022.100238. [CrossRef]

- Rassas, I.; Braiek, M.; Bonhomme, A.; Bessueille, F.; Rafin, G.; Majdoub, H.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N. Voltammetric glucose biosensor based on glucose oxidase encapsulation in a chitosan-kappa-carrageenan polyelectrolyte complex. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 95, 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2018.10.078. [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Dadmohammadi, Y.; Lee, M.C.; Abbaspourrad, A. Combination of copigmentation and encapsulation strategies for the synergistic stabilization of anthocyanins. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3164–3191. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12772. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Gao, J.; Ye, H.; Ren, G.; Ma, X.; Xie, H.; Fang, S.; Lei, Q.; Fang, W. Development of ovalbumin-pectin nanocomplexes for vitamin D3 encapsulation: Enhanced storage stability and sustained release in simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 106, 105926–105935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105926. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Leon, L. Structural transitions and encapsulation selectivity of thermoresponsive polyelectrolyte complex micelles. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 6438–6448. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9tb01194c. [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Schlenoff, J.B. Driving Forces for Oppositely Charged Polyion Association in Aqueous Solutions: Enthalpic, Entropic, but Not Electrostatic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 980–990. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5b11878. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.D.; Vanjari, Y.H.; Sancheti, K.H.; Patel, H.M.; Belgamwar, V.S.; Surana, S.J.; Pardeshi, C. V. Polyelectrolyte complexes: mechanisms, critical experimental aspects, and applications. Artif. Cells, Nanomedicine Biotechnol. 2016, 44, 1615–1625. https://doi.org/10.3109/21691401.2015.1129624. [CrossRef]

- Shovsky, A.; Varga, I.; Makuška, R.; Claesson, P.M. Formation and stability of water-soluble, molecular polyelectrolyte complexes: Effects of charge density, mixing ratio, and polyelectrolyte concentration. Langmuir 2009, 25, 6113–6121. https://doi.org/10.1021/la804189w. [CrossRef]

- Jha, P.K.; Desai, P.S.; Li, J.; Larson, R.G. pH and salt effects on the associative phase separation of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes. Polymers (Basel). 2014, 6, 1414–1436. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym6051414. [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Pan, W.; Liang, D. Synergistic and antagonistic effect of chain lengths below and above critical value on polyelectrolyte complex. Polymer (Guildf). 2019, 181, 121734–121741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2019.121734. [CrossRef]

- Schatz, C.; Lucas, J.M.; Viton, C.; Domard, A.; Pichot, C.; Delair, T. Formation and properties of positively charged colloids based on polyelectrolyte complexes of biopolymers. Langmuir 2004, 20, 7766–7778. https://doi.org/10.1021/la049460m. [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, V.M. Interfacial tension in polyelectrolyte systems exhibiting associative liquid–liquid phase separation. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 53, 101422–101421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cocis.2021.101422. [CrossRef]

- Dubashynskaya, N. V.; Petrova, V.A.; Romanov, D.P.; Skorik, Y.A. pH-Sensitive Drug Delivery System Based on Chitin Nanowhiskers–Sodium Alginate Polyelectrolyte Complex. Materials (Basel). 2022, 15, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15175860. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, P.; Patil, K.; Dhatrak, P. Polyelectrolyte Complex for Drug Delivery in Biomedical Applications: A Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1183, 12007–12017. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/1183/1/012007. [CrossRef]

- Kwame, B.J.; Kang, J.-H.; Yun, Y.-S.; Choi, S.-H. Facile Processing of Polyelectrolyte Complexes for Immobilization of Heavy Metal Ions in Wastewater. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 2346–2354.

- Chan, K.; Morikawa, K.; Shibata, N.; Zinchenko, A. Adsorptive removal of heavy metal ions, organic dyes, and pharmaceuticals by dna–chitosan hydrogels. Gels 2021, 7, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels7030112. [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, A.R.; Zhang, Z.; Sip, Y.Y.L.; Zhai, L.; Sadmani, A.H.M.A. Removal of heavy metals from water using electrospun polyelectrolyte complex fiber mats. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 37, 101438–101445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101438. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.; Ban, S.; Devkota, S.; Sharma, S.; Joshi, R.; Tiwari, A.P.; Kim, H.Y.; Joshi, M.K. Technological trends in heavy metals removal from industrial wastewater: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105688–105705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2021.105688. [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, T.F.S.; R.S., A.G.; Nascimento, K.N.S.; dos Santos, S.B.; Costa Santos, M. de F.; Montes D’Oca, C.D.R.; dos S. Estevam, C.; Gimenez, I.F.; Almeida, L.E. Supramolecular polyelectrolyte complexes based on cyclodextrin-graftedchitosan and carrageenan for controlled drug release.pdf. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 245, 116592–116604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116592. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, M.; Kishimoto, S.; Nakamura, S.; Sato, Y.; Hattori, H. Polyelectrolyte complexes of natural polymers and their biomedical applications. Polymers (Basel). 2019, 11, 672–683. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11040672. [CrossRef]

- Udoetok, I.A.; Faye, O.; Wilson, L.D. Adsorption of Phosphate Dianions by Hybrid Inorganic-Biopolymer Polyelectrolyte Complexes: Experimental and Computational Studies. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 899–910. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsapm.9b01123. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.E.P.; de Oliveira, M.A.S.; Simas, F.F.; Riegel-Vidotti, I.C. Physical chemical study of zein and arabinogalactans or glucuronomannans polyelectrolyte complexes and their film-forming properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 100, 105394–105404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.105394. [CrossRef]

- Raik, S. V.; Gasilova, E.R.; Dubashynskaya, N. V.; Dobrodumov, A. V.; Skorik, Y.A. Diethylaminoethyl chitosan–hyaluronic acid polyelectrolyte complexes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 146, 1161–1168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.054. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Lu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Cheng, S.; Tian, F.; Xiao, Y.; Li, F. Chitosan/alginate/hyaluronic acid polyelectrolyte composite sponges crosslinked with genipin for wound dressing application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 512–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.04.044. [CrossRef]

- Rosales, T.K.O.; Fabi, J.P. Pectin-based nanoencapsulation strategy to improve the bioavailability of bioactive compounds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 229, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.12.292. [CrossRef]

- Strauch, A.; Rossa, B.; Köhler, F.; Haeussler, S.; Mühlhofer, M.; Rührnößl, F.; Körösy, C.; Bushman, Y.; Conradt, B.; Weinkauf, S.; et al. Jo ur n Pr e of. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 102753–102789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.109909. [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Liu, B.; Zhang, H.; Ryu, S.; Kuss, M.; Shukla, D.; Hu, G.; Shi, W.; Jiang, X.; Lei, Y.; et al. Controllable fabrication of alginate/poly-L-ornithine polyelectrolyte complex hydrogel networks as therapeutic drug and cell carriers. Acta Biomater. 2022, 138, 182–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2021.11.004. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Li, S.; Zhu, W.; Liang, Z.; Zeng, Q. Self-assembly pH-sensitive chitosan/alginate coated polyelectrolyte complexes for oral delivery of insulin. J. Microencapsul. 2019, 36, 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/02652048.2019.1604846. [CrossRef]

- Le, H. Van; Le Cerf, D. Colloidal Polyelectrolyte Complexes from Hyaluronic Acid: Preparation and Biomedical Applications. Small 2022, 18, 2204283–2204308. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202204283. [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Huangfu, X.; Li, Z.; Wu, Z.; Li, D.; Zhang, M. Nanoaggregates of silica with kaolinite and montmorillonite: Sedimentation and transport. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 669, 893–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.099. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Hu, D.; Zhu, F.; Ma, Y.; Yan, D. High-efficiency blue-emission crystalline organic lightemitting diodes sensitized by “hot exciton” fluorescent nanoaggregates. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.add1757. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghzadeh, F.; Motavalizadehkakhky, A.; Mehrzad, J.; Zhiani, R.; Homayouni Tabrizi, M. Folic acid conjugated-chitosan modified nanostructured lipid carriers as promising carriers for delivery of Umbelliprenin to cancer cells: In vivo and in vitro. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 186, 111849–111861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2023.111849. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, E.D.P.; Santos Silva, L.A.; de Araujo, G.R.S.; Montalvão, M.M.; Matos, S.S.; da Cunha Gonsalves, J.K.M.; de Souza Nunes, R.; de Meneses, C.T.; Oliveira Araujo, R.G.; Sarmento, V.H.V.; et al. Chitosan-functionalized nanostructured lipid carriers containing chloroaluminum phthalocyanine for photodynamic therapy of skin cancer. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2022, 179, 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2022.09.009. [CrossRef]

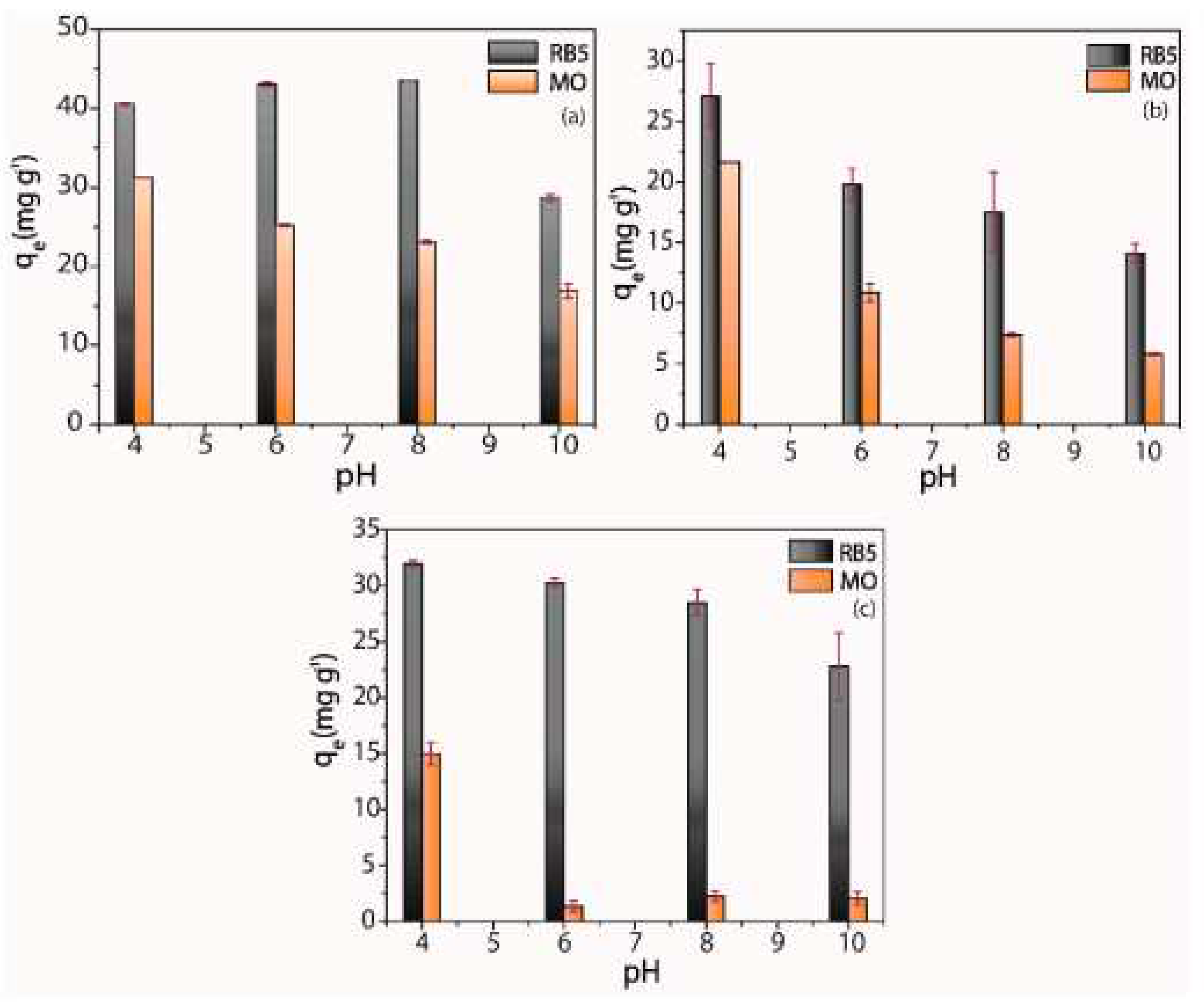

- Freire, T.M.; Fechine, L.M.U.D.; Queiroz, D.C.; Freire, R.M.; Denardin, J.; Ricardo, N.; Rodrigues, T.; Gondim, D.; Junior, I.; Fechine, P. Magnetic Porous Controlled Fe 3 O 4 – Chitosan Nanostructure : An Ecofriendly Adsorbent for Efficient Removal of Azo Dyes. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1194–1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10061194. [CrossRef]

- Albishri, W.S.; Katouah, H.A.; Katouah, H.A. Department of Chemistry , Faculty of Applied Sciences , Umm Al- Herein , sodium magnesium silicate hydroxide / sodium magnesium hydrothermal method . After that , the synthesized nanostructures aqueous media . The synthesized nanostructures and their chit. Aranbian J. Chem. 2023, 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.104804. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Bary, A.S.; Tolan, D.A.; Nassar, M.Y.; Taketsugu, T.; El-Nahas, A.M. Chitosan, magnetite, silicon dioxide, and graphene oxide nanocomposites: Synthesis, characterization, efficiency as cisplatin drug delivery, and DFT calculations. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 621–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.106. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-López, G.; Ventura-Aguilar, R.I.; Correa-Pacheco, Z.N.; Bautista-Baños, S.; Barrera-Necha, L.L. Nanostructured chitosan edible coating loaded with α-pinene for the preservation of the postharvest quality of Capsicum annuum L. and Alternaria alternata control. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 1881–1888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.10.094. [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Yuan, M.M.; Huang, Z.N.; Chen, X.Q.; Jiang, X.Y.; Jiao, F.P.; Zhou, N.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, J.G. Highly-sensitive and selective determination of bisphenol A in milk samples based on self-assembled graphene nanoplatelets-multiwalled carbon nanotube-chitosan nanostructure. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 103, 109848–109858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2019.109848. [CrossRef]

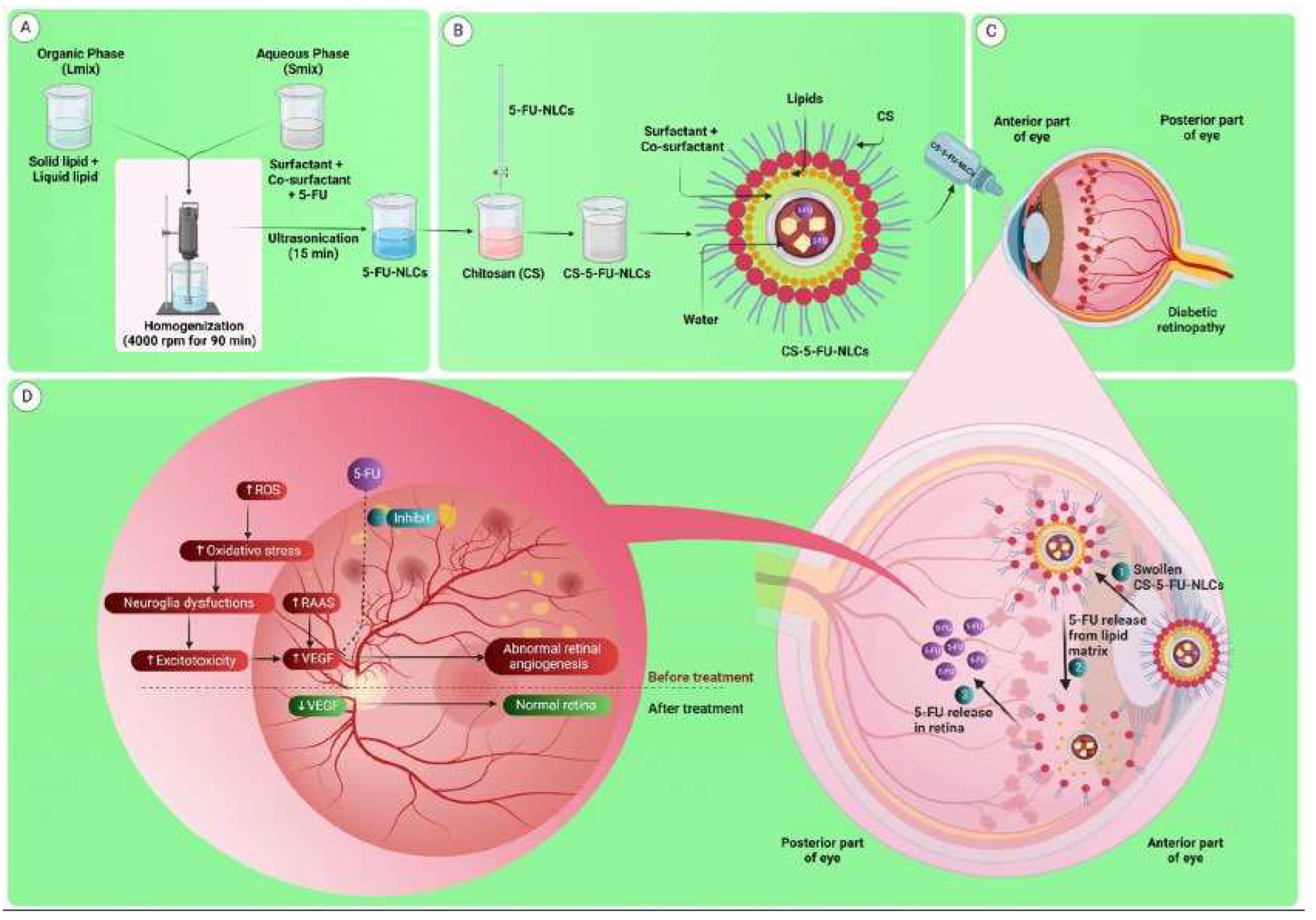

- Sharma, D.S.; Wadhwa, S.; Gulati, M.; Kumar, B.; Chitranshi, N.; Gupta, V.K.; Alrouji, M.; Alhajlah, S.; AlOmeir, O.; Vishwas, S.; et al. Chitosan modified 5-fluorouracil nanostructured lipid carriers for treatment of diabetic retinopathy in rats: A new dimension to an anticancer drug. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 224, 810–830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.10.168. [CrossRef]

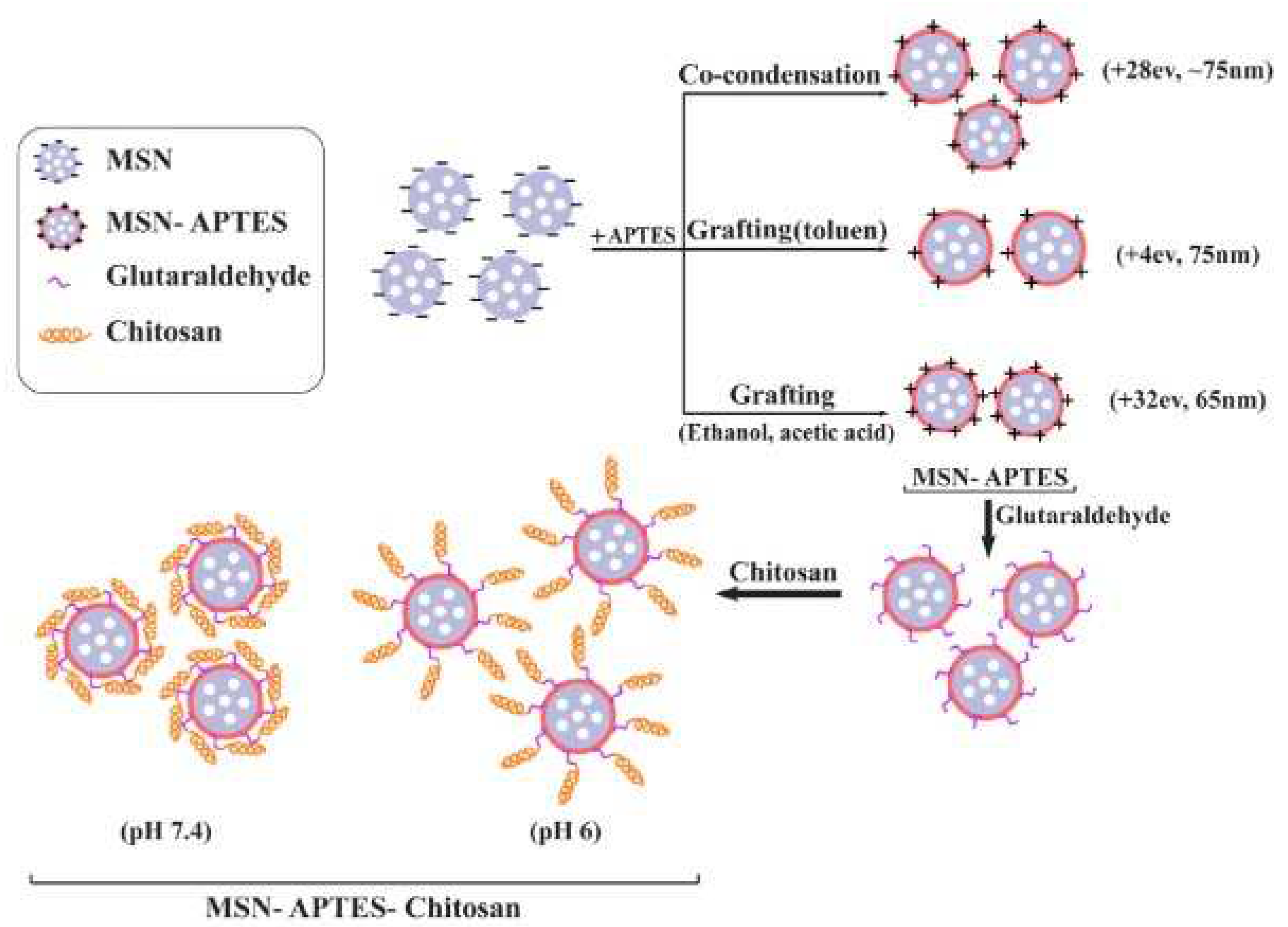

- Shakeran, Z.; Keyhanfar, M.; Varshosaz, J.; Sutherland, D. Biodegradable nanocarriers based on chitosan-modified mesoporous silica.pdf. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 118, 111526–111543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2020.111526. [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Singh, A.; Singh, A.V. Synthesis and characterization of pectin-chitosan conjugate for biomedical application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 153, 533–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.313. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Meng, L.; Li, X. Magnetic polyelectrolyte complex (PEC)-stabilized Fe/Pd bimetallic particles for removal of organic pollutants in aqueous solution. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 096113–096126. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ab336e. [CrossRef]

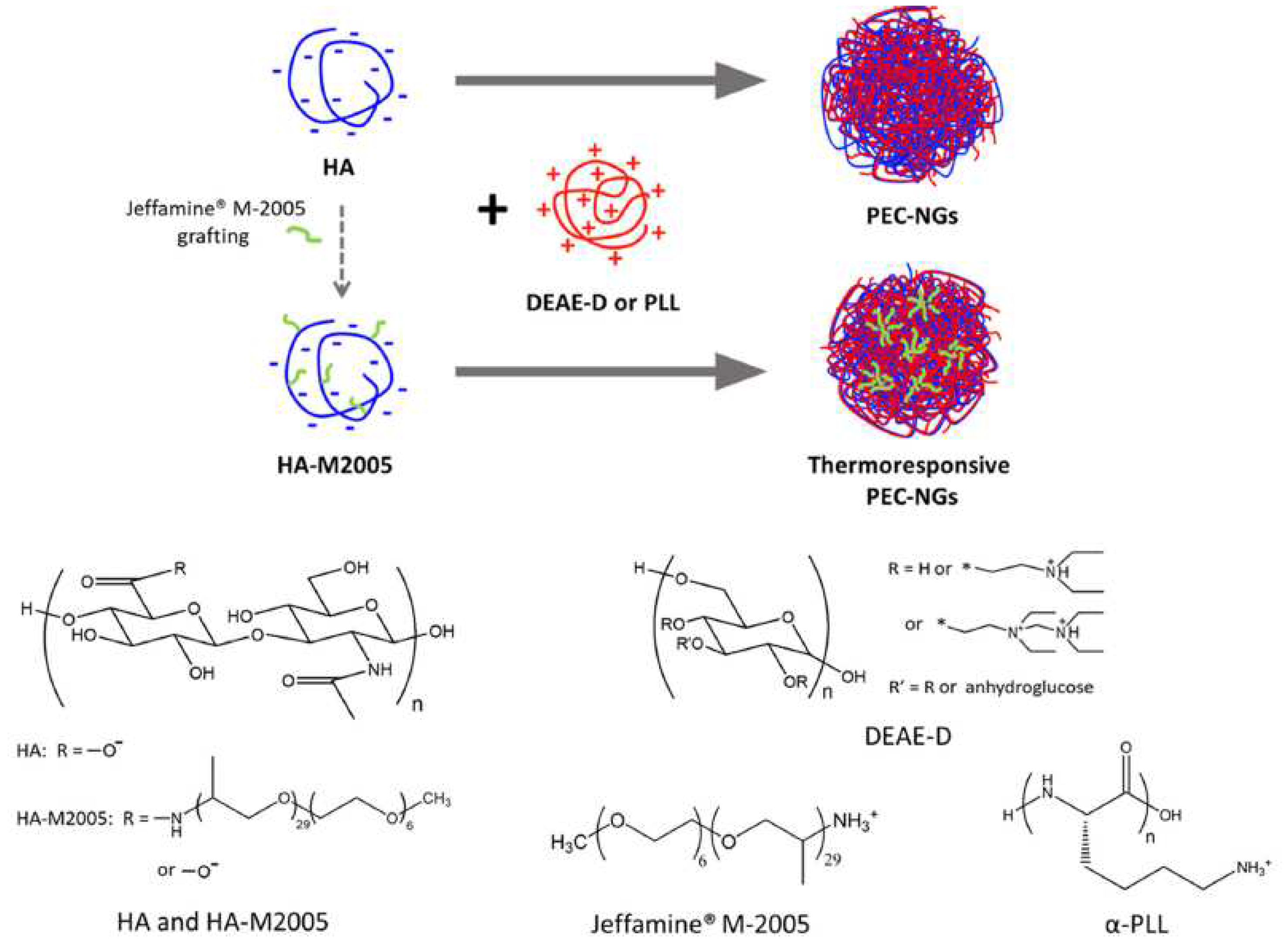

- Le, H. Van; Dulong, V.; Picton, L.; Le Cerf, D. Thermoresponsive nanogels based on polyelectrolyte complexes between polycations and functionalized hyaluronic acid. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 292, 119711–119721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119711. [CrossRef]

- Okagu, O.D.; Jin, J.; Udenigwe, C.C. Impact of succinylation on pea protein-curcumin interaction, polyelectrolyte complexation with chitosan, and gastrointestinal release of curcumin in loaded-biopolymer nano-complexes. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 325, 115248–115260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2020.115248. [CrossRef]

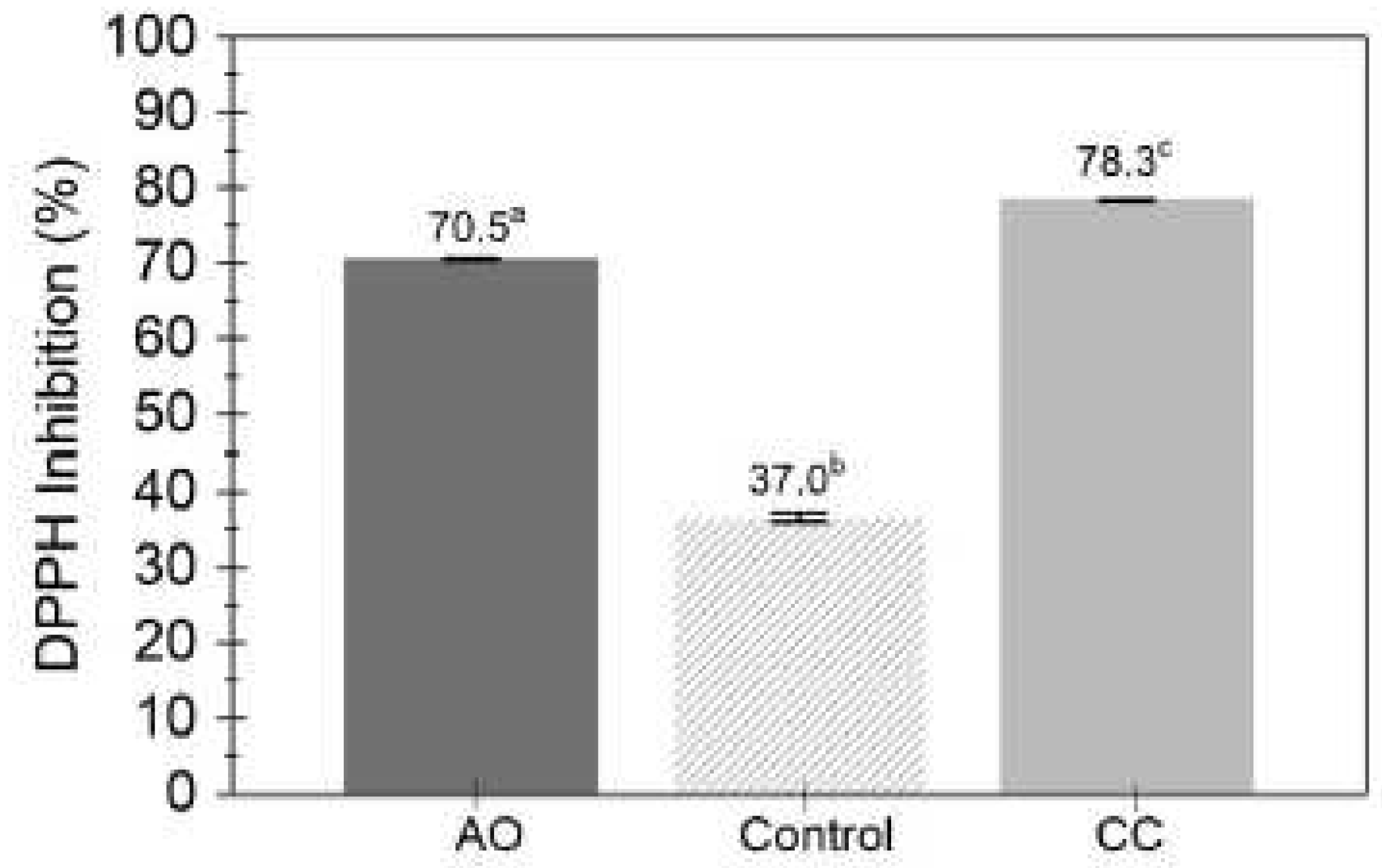

- Teixeira-Costa, B.E.; Silva Pereira, B.C.; Lopes, G.K.; Tristão Andrade, C. Encapsulation and antioxidant activity of assai pulp oil (Euterpe oleracea) in chitosan/alginate polyelectrolyte complexes. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 109, 106097–106105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106097. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Xu, Q. Polyelectrolyte complex from cationized casein and sodium alginate for fragrance controlled release. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2019, 178, 439–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.03.017. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J.A.; Sepúlveda, F.A.; Panadero-Medianero, C.; Murgas, P.; Ahumada, M.; Palza, H.; Matsuhiro, B.; Zapata, P.A. Cytocompatible drug delivery hydrogels based on carboxymethylagarose/chitosan pH-responsive polyelectrolyte complexes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 199, 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.12.093. [CrossRef]

- Vossoughi, A.; Matthew, H.W.T. Encapsulation of mesenchymal stem cells in glycosaminoglycans-chitosan polyelectrolyte microcapsules using electrospraying technique: Investigating capsule morphology and cell viability. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2018, 3, 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1002/btm2.10111. [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S.; Venkatesan, J.; Yuvarajan, S.; Rekha, P.D. Self-assembled polyelectrolyte complexes of chitosan and fucoidan for sustained growth factor release from PRP enhance proliferation and collagen deposition in diabetic mice. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 2838–2855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13346-022-01144-3. [CrossRef]

- Souza, V.G.L.; Mello, I.P.; Khalid, O.; Pires, J.R.A.; Rodrigues, C.; Alves, M.M.; Santos, C.; Fernando, A.L.; Coelhoso, I. Strategies to Improve the Barrier and Mechanical Properties of Pectin Films for Food Packaging: Comparing Nanocomposites with Bilayers. Coatings 2022, 12, 108–128. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12020108. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhu, K.; Ma, Y.; Yu, Z.; Chiou, B.-S.; Jia, M.; Chen, M.; Zhong, F. Collagen films with improved wet state mechanical properties by mineralization. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 139, 108579–108588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108579. [CrossRef]

- Marangoni Júnior, L.; Rodrigues, P.R.; Silva, R.G. da; Vieira, R.P.; Alves, R.M.V. Improving the mechanical properties and thermal stability of sodium alginate/hydrolyzed collagen films through the incorporation of SiO2. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2021.12.012. [CrossRef]

- Ardjoum, N.; Chibani, N.; Shankar, S.; Salmieri, S.; Djidjelli, H.; Lacroix, M. Incorporation of Thymus vulgaris essential oil and ethanolic extract of propolis improved the antibacterial, barrier and mechanical properties of corn starch-based films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 224, 578–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.10.146. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Jeong, D.; Kanmani, P. Study on physical and mechanical properties of the biopolymer/silver based active nanocomposite films with antimicrobial activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 224, 115159–115166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115159. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ge, X.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y. Eugenol embedded zein and poly(lactic acid) film as active food packaging: Formation, characterization, and antimicrobial effects. Food Chem. 2022, 384, 132482–132491.

- Jovanović, J.; Ćirković, J.; Radojković, A.; Mutavdžić, D.; Tanasijević, G.; Joksimović, K.; Bakić, G.; Branković, G.; Branković, Z. Chitosan and pectin-based films and coatings with active components for application in antimicrobial food packaging. Prog. Org. Coatings 2021, 158, 106349–106359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2021.106349. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Qin, Q.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Liao, X. Development of electrospun films enriched with ethyl lauroyl arginate as novel antimicrobial food packaging materials for fresh strawberry preservation. Food Control 2021, 130, 108371–108381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108371. [CrossRef]

- Saedi, S.; Shokri, M.; Kim, J.T.; Shin, G.H. Semi-transparent regenerated cellulose/ZnONP nanocomposite film as a potential antimicrobial food packaging material. J. Food Eng. 2021, 307, 110665–110677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2021.110665. [CrossRef]

- Severo, C.; Anjos, I.; Souza, V.G.L.; Canejo, J.P.; Bronze, M.R.; Fernando, A.L.; Coelhoso, I.; Bettencourt, A.F.; Ribeiro, I.A.C. Development of cranberry extract films for the enhancement of food packaging antimicrobial properties. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 28, 100646–100654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2021.100646. [CrossRef]

- Kowsalya, E.; Mosa Christas, K.; Balashanmugam, P.; Tamil Selvi, A.; Jaquline Chinna Rani, I. Biocompatible silver nanoparticles/poly(vinyl alcohol) electrospun nanofibers for potential antimicrobial food packaging applications. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 21, 100379–100386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2019.100379. [CrossRef]

- Alkan Tas, B.; Sehit, E.; Erdinc Tas, C.; Unal, S.; Cebeci, F.C.; Menceloglu, Y.Z.; Unal, H. Carvacrol loaded halloysite coatings for antimicrobial food packaging applications. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 20, 100300–100305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2019.01.004. [CrossRef]

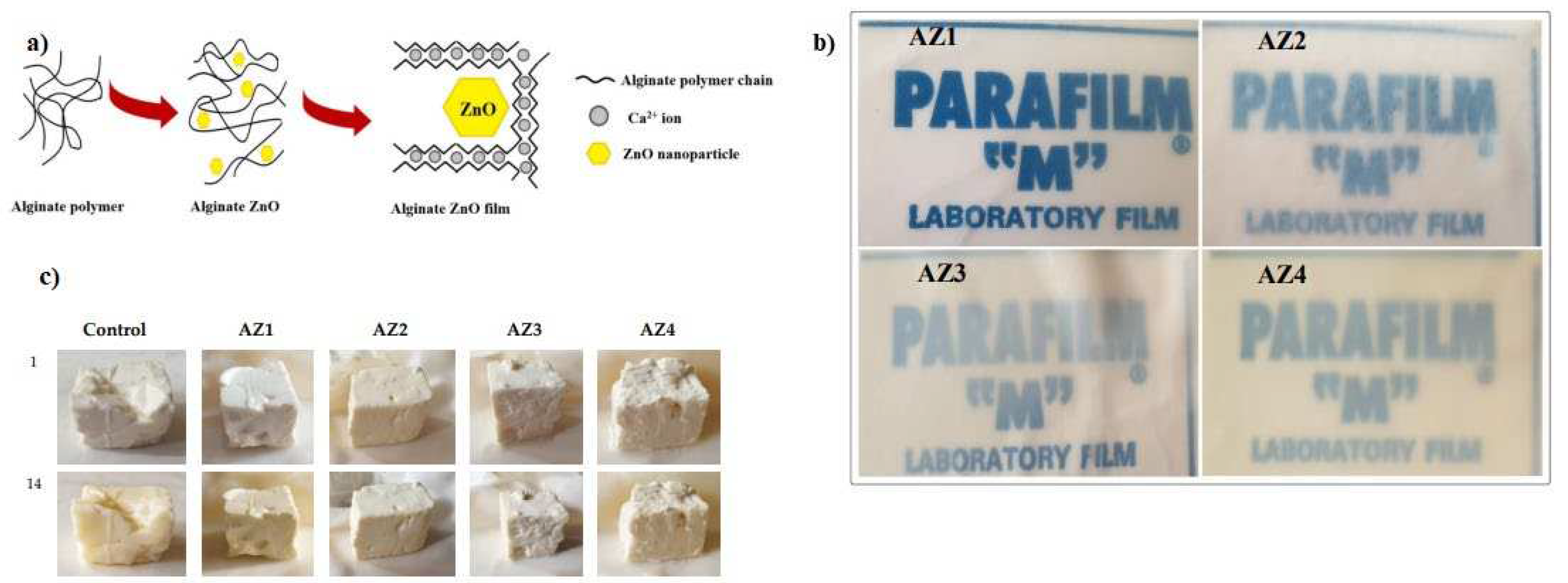

- Motelica, L.; Ficai, D.; Oprea, O.; Ficai, A.; Trusca, R.D.; Andronescu, E.; Holban, A.M. Biodegradable alginate films with zno nanoparticles and citronella essential oil-a novel antimicrobial structure. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1020–1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13071020. [CrossRef]

- Abarca, R.L.; Medina, J.; Alvarado, N.; Ortiz, P.A.; López, B.C. Biodegradable gelatin-based films with nisin and EDTA that inhibit Escherichia coli. PLoS One 2022, 17, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264851. [CrossRef]

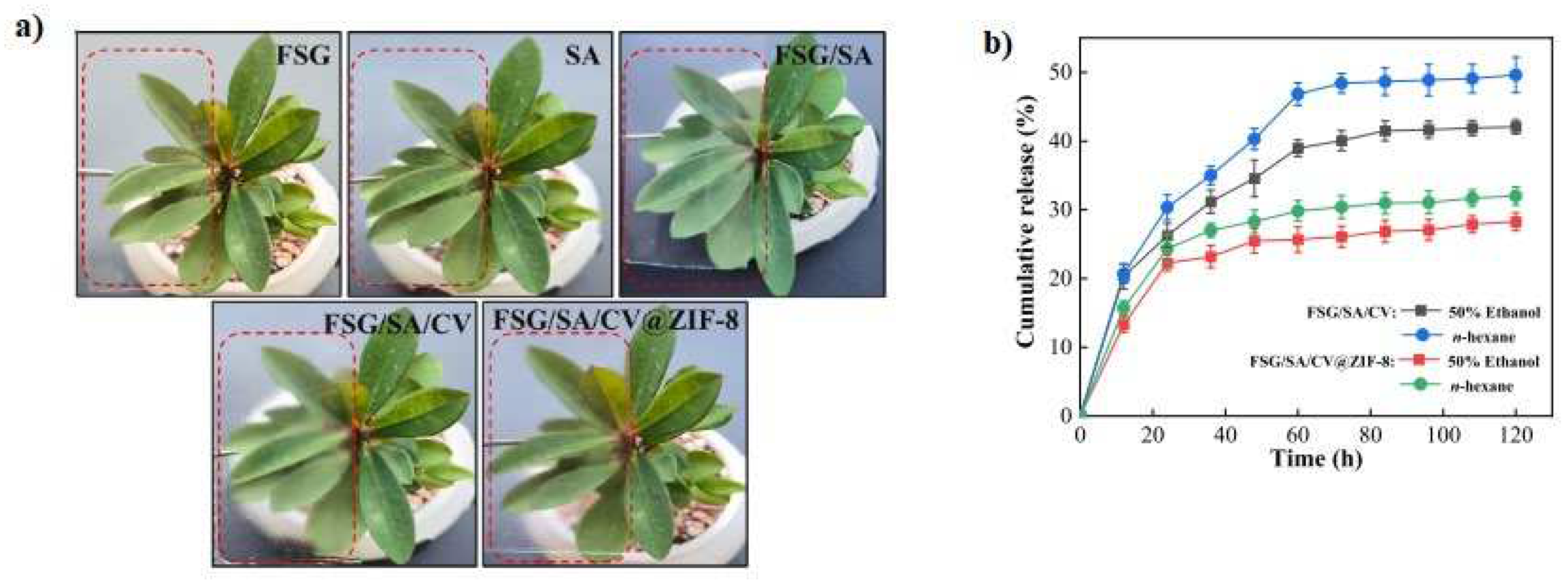

- Li, Y.; Shan, P.; Yu, F.; Li, H.; Peng, L. Fabrication and characterization of waste fish scale-derived gelatin/sodium alginate/carvacrol loaded ZIF-8 nanoparticles composite films with sustained antibacterial activity for active food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 230, 123192–123206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123192. [CrossRef]

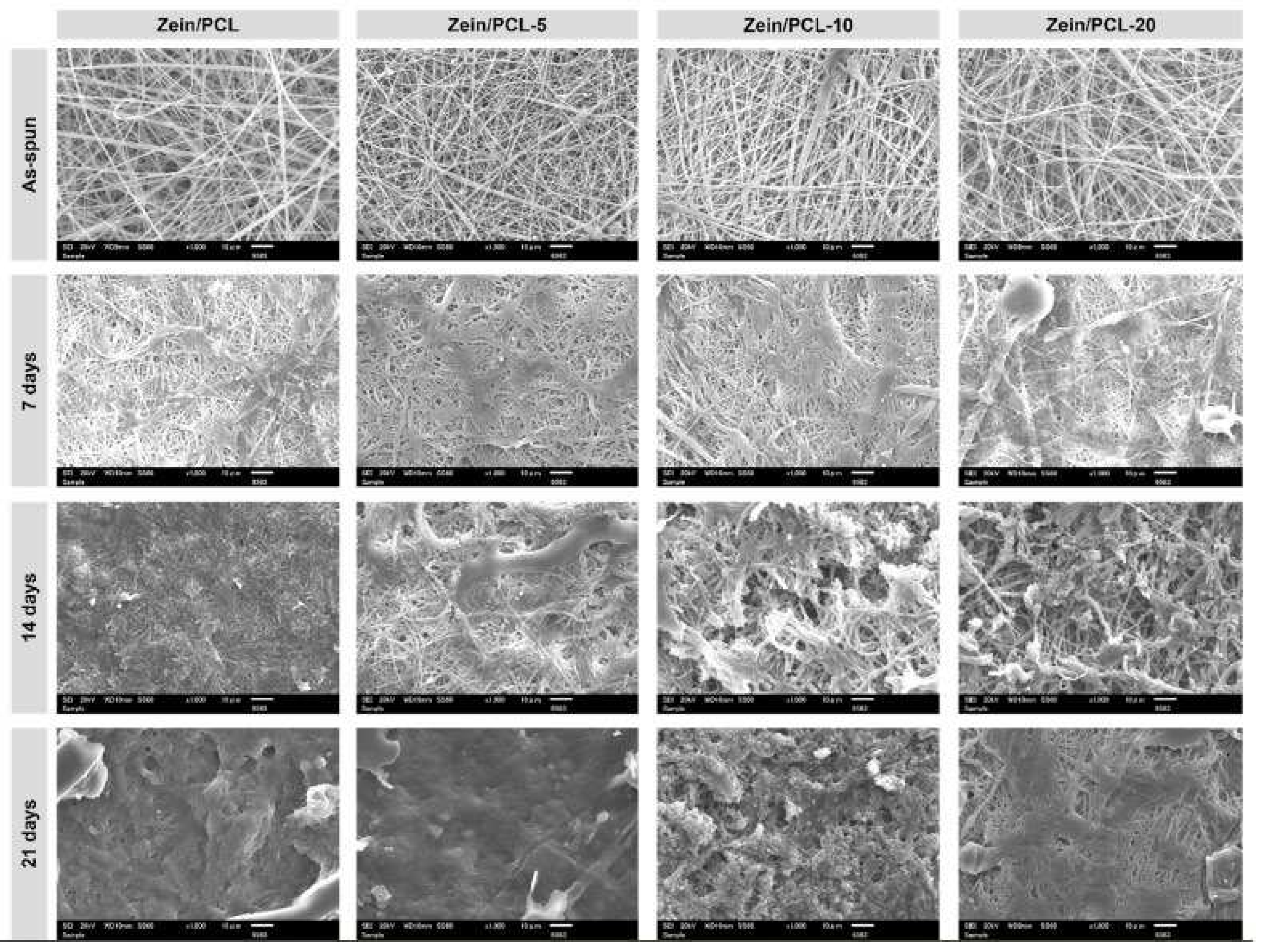

- Ullah, A.; Sun, L.; Wang, F.; Nawaz, H.; Yamashita, K.; Cai, Y.; Anwar, F.; Khan, M.Q.; Mayakrishnan, G.; Kim, I.S. Eco-friendly bioactive β-caryophyllene-halloysite nanotubes loaded.pdf. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 35, 101028–101044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2023.101028. [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Zheng, T.; Yang, C.; Li, G. Enhanced physicochemical and functional properties of collagen films cross-linked with laccase oxidized phenolic acids for active edible food packaging. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133353–133362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133353. [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.A.B.; Nada, A.A.; Al-Moghazy, M. Self-stick membrane based on grafted gum Arabic as active food packaging for cheese using cinnamon extract. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 189, 114–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.08.071. [CrossRef]

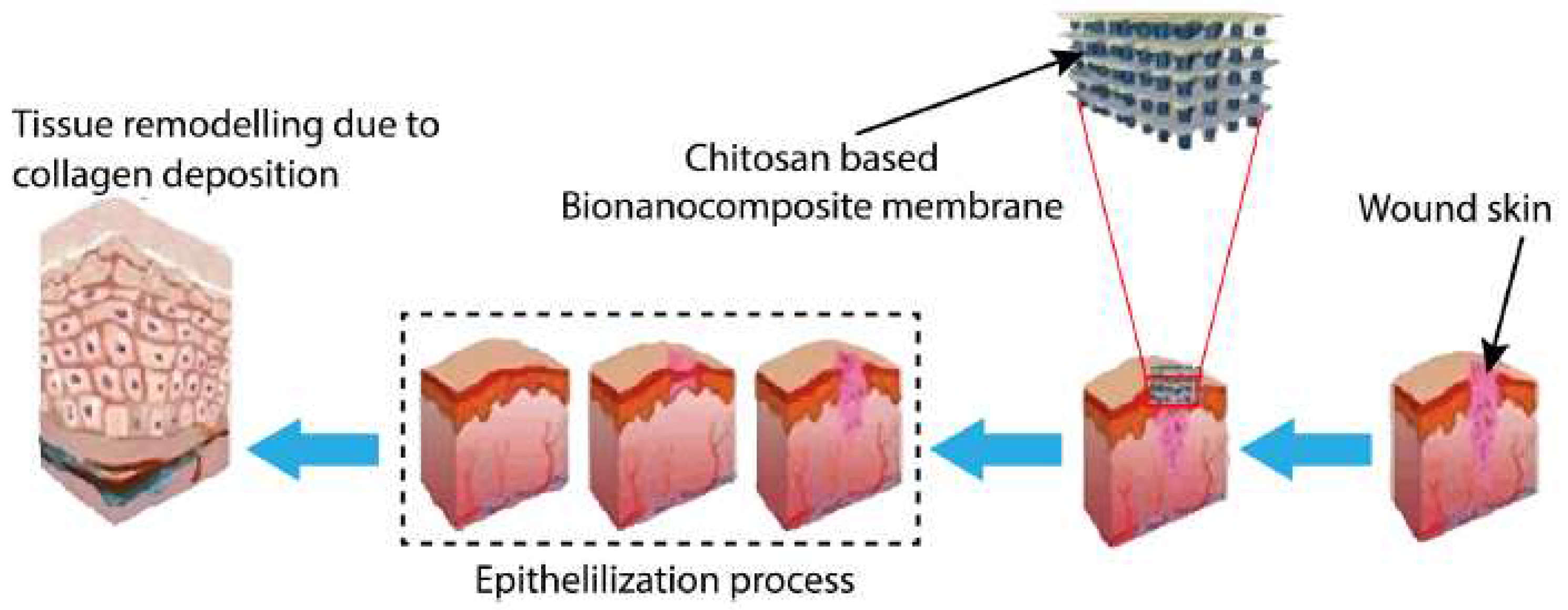

- Hou, B.; Qi, M.; Sun, J.; Ai, M.; Ma, X.; Cai, W.; Zhou, Y.; Ni, L.; Hu, J.; Xu, F.; et al. Preparation, characterization and wound healing effect of vaccarin-chitosan nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 3169–3179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.10.182. [CrossRef]

- Azmana, M.; Mahmood, S.; Hilles, A.R.; Rahman, A.; Arifin, M.A. Bin; Ahmed, S. A review on chitosan and chitosan-based bionanocomposites: Promising material for combatting global issues and its applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 185, 832–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.07.023. [CrossRef]

- Saheed, I.O.; Oh, W. Da; Suah, F.B.M. Chitosan modifications for adsorption of pollutants – A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 408, 124889–124904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124889. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.X.; Li, W.; Xiong, Y.S.; Lu, H.Q.; Li, H.; Li, K. Preparation of quaternary ammonium-functionalized metal–organic framework/chitosan composite aerogel with outstanding scavenging of melanoidin. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 316, 123785–123799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2023.123785. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, K.; Li, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, B. Hydrogen inhibition effect of chitosan and sodium phosphate on ZK60 waste dust in a wet dust removal system: A feasible way to control hydrogen explosion. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2021, 13, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jma.2021.11.017. [CrossRef]

- Neetha, A.S.; Rao, K. V. Broccoli-shaped nano florets-based gastrointestinal diseases detection by copper oxide chitosan. Mater. Today Chem. 2023, 30, 101503–101516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtchem.2023.101503. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira-Santos, R.; Lima, M.; Gomes, L.C.; Mergulhão, F.J. Antimicrobial coatings based on chitosan to prevent implant-associated infections: A systematic review. iScience 2021, 24, 103480–103502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.103480. [CrossRef]

- Aranaz, I.; Alcántara, A.R.; Civera, M.C.; Arias, C.; Elorza, B.; Caballero, A.H.; Acosta, N. Chitosan: An overview of its properties and applications. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13, 3256–3282. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13193256. [CrossRef]

- Kurek, M.; Benbettaieb, N.; Ščetar, M.; Chaudy, E.; Repajić, M.; Klepac, D.; Valić, S.; Debeaufort, F.; Galić, K. Characterization of food packaging films with blackcurrant fruit waste as a source of antioxidant and color sensing intelligent material. Molecules 2021, 26, 2569–2583. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092569. [CrossRef]

- Şen, F.; Uzunsoy, İ.; Baştürk, E.; Kahraman, M.V. Antimicrobial agent-free hybrid cationic starch/sodium alginate polyelectrolyte films for food packaging materials. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 170, 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.04.079. [CrossRef]

- Torres Vargas, O.L.; Galeano Loaiza, Y.V.; González, M.L. Effect of incorporating extracts from natural pigments in alginate/starch films. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 13, 2239–2250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.05.091. [CrossRef]

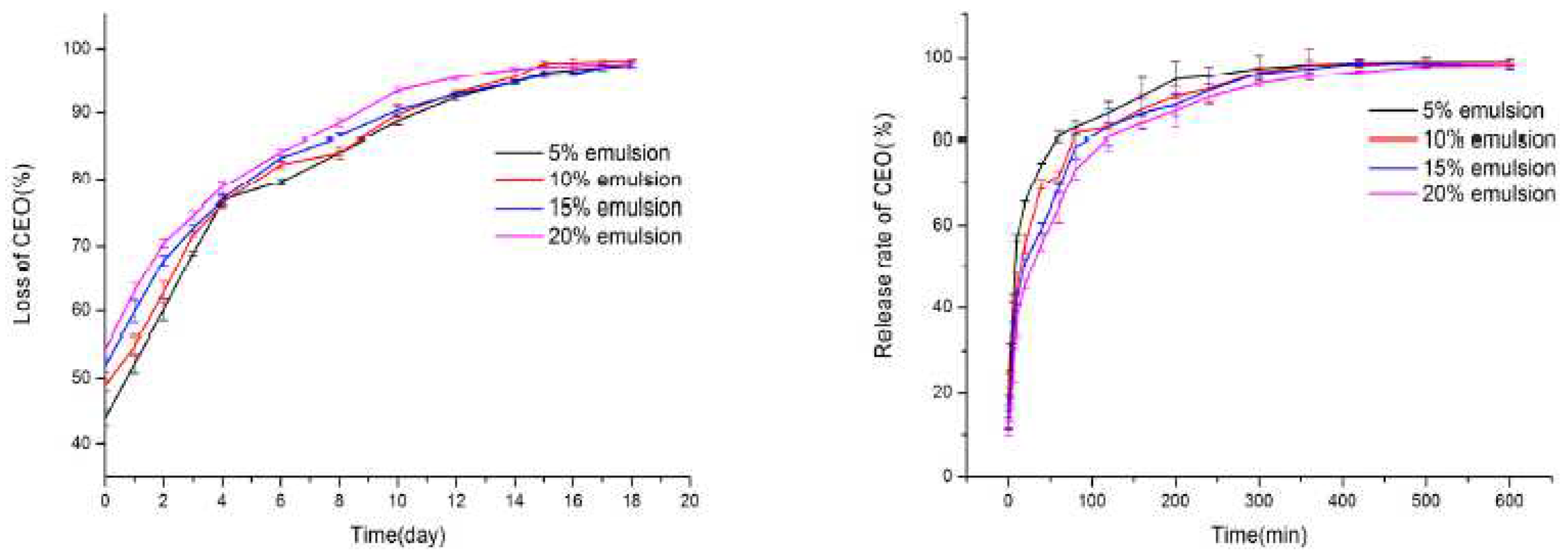

- Xu, T.; Gao, C.C.; Feng, X.; Wu, D.; Meng, L.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X. Characterization of chitosan based polyelectrolyte films incorporated with OSA-modified gum arabic-stabilized cinnamon essential oil emulsions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 362–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.108. [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.; Catchmark, J.M. Improved eco-friendly barrier materials based on crystalline nanocellulose/chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose polyelectrolyte complexes. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 80, 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.02.003. [CrossRef]

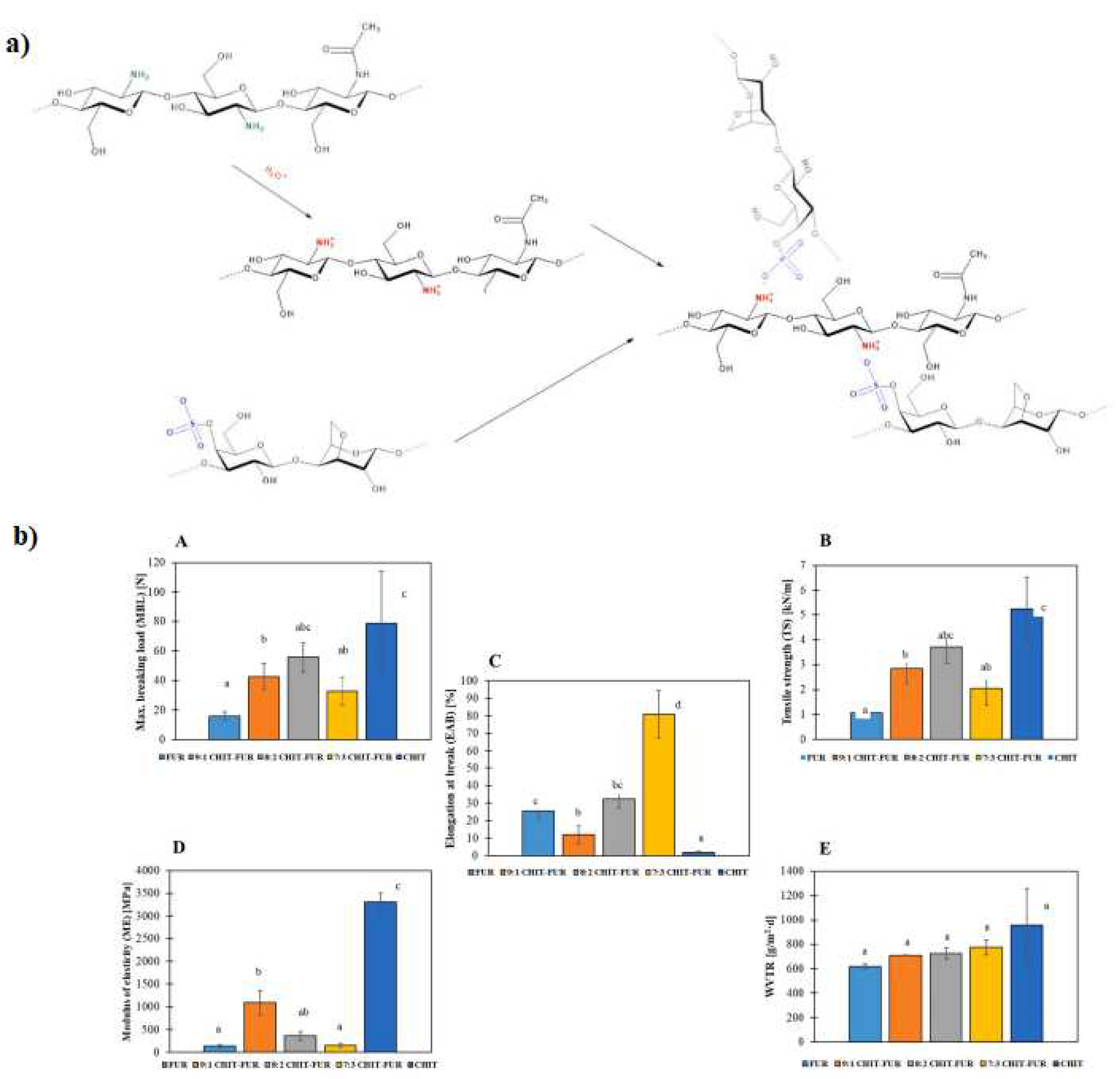

- Jamróz, E.; Janik, M.; Juszczak, L.; Kruk, T.; Kulawik, P.; Szuwarzyński, M.; Kawecka, A.; Khachatryan, K. Composite biopolymer films based on a polyelectrolyte complex of furcellaran and chitosan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 274, 118627–118637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118627. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, D.; Jin, T.Z.; Chen, W.; He, Q.; Zou, Z.; Zhao, H.; Ye, X.; Guo, M. Preparation and characterization of gellan gum-chitosan polyelectrolyte complex films with the incorporation of thyme essential oil nanoemulsion. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 114, 106570–106580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106570. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira-Costa, B.E.; Silva Pereira, B.C.; Lopes, G.K.; Tristão Andrade, C. Encapsulation and antioxidant activity of assai pulp oil (Euterpe oleracea) in chitosan/alginate polyelectrolyte complexes. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 109, 106097–106106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106097. [CrossRef]

- Şen, F.; Kahraman, M.V. Preparation and characterization of hybrid cationic hydroxyethyl cellulose/sodium alginate polyelectrolyte antimicrobial films. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2018, 29, 1895–1901. https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.4298. [CrossRef]

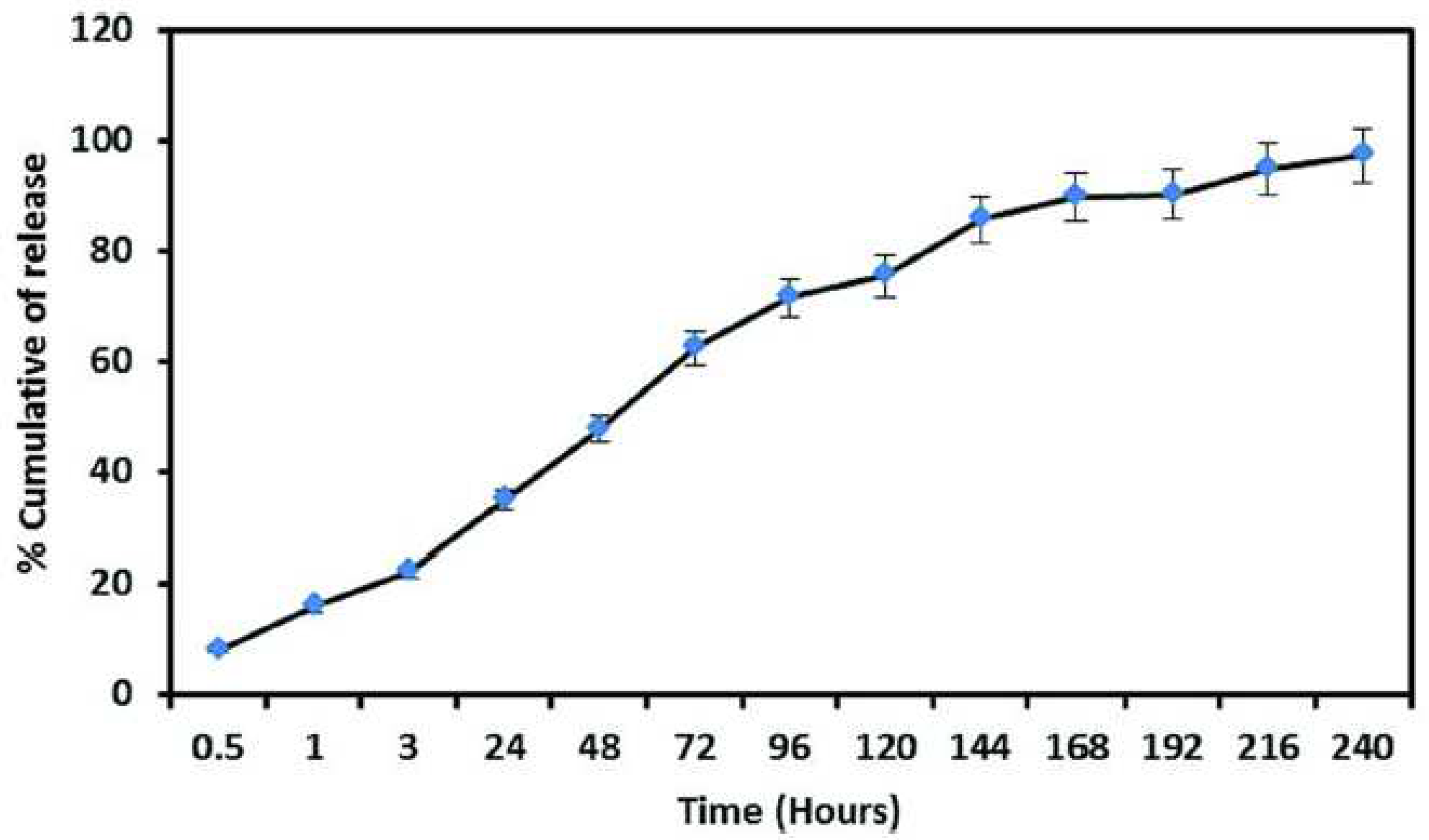

- Riyandari, B.A.; Suherman; Siswanta, D. The physico-mechanical properties and release kinetics of eugenol in chitosan-alginate polyelectrolyte complex films as active food packaging. Indones. J. Chem. 2018, 18, 82–91. https://doi.org/10.22146/ijc.26525. [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.F.; Zhao, S.; Chiou, J. Antibacterial and clusteroluminogenic hypromellose-graft-chitosan-based polyelectrolyte complex films with high functional flexibility for food packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 271, 118447–118456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118447. [CrossRef]

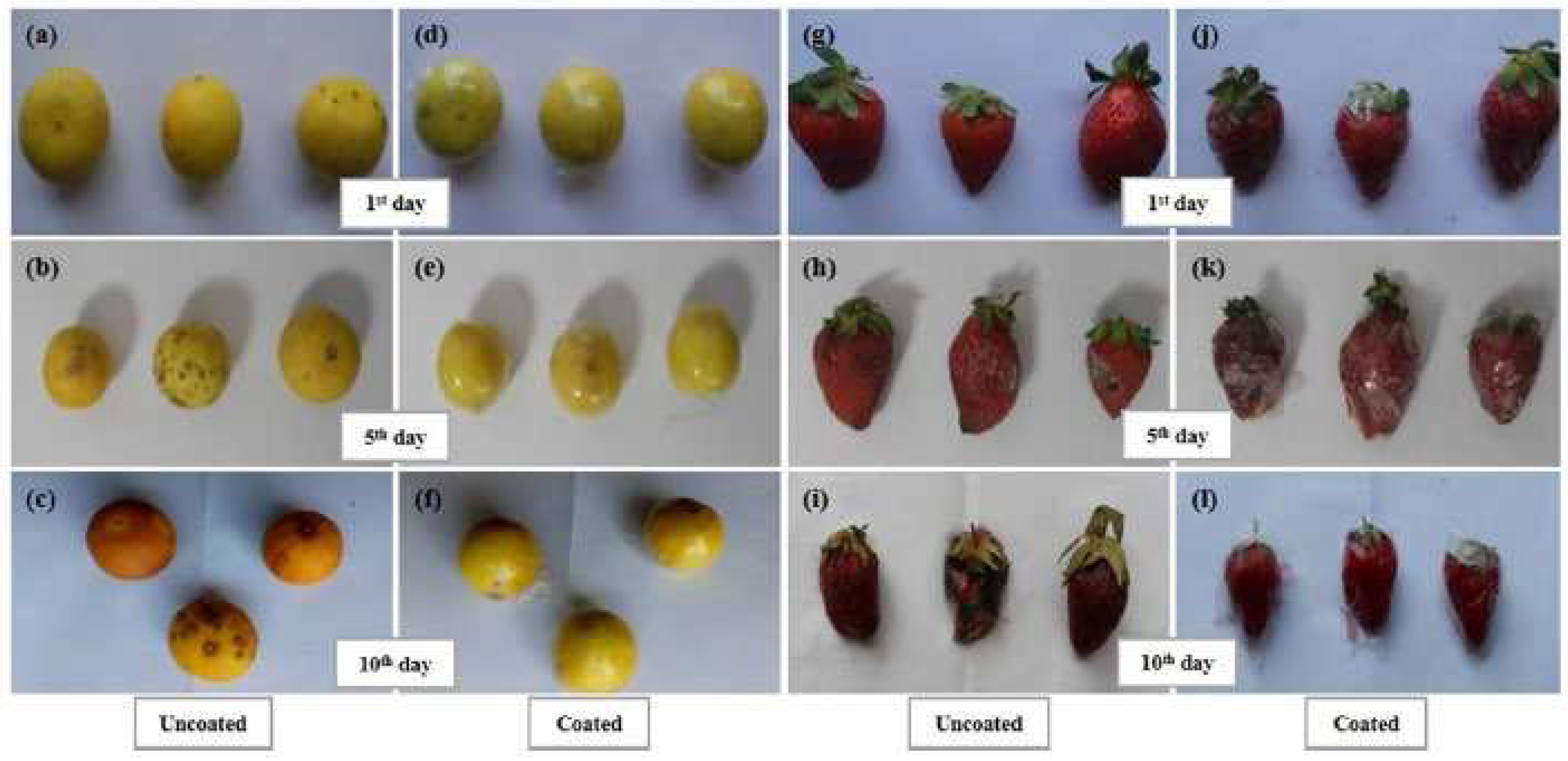

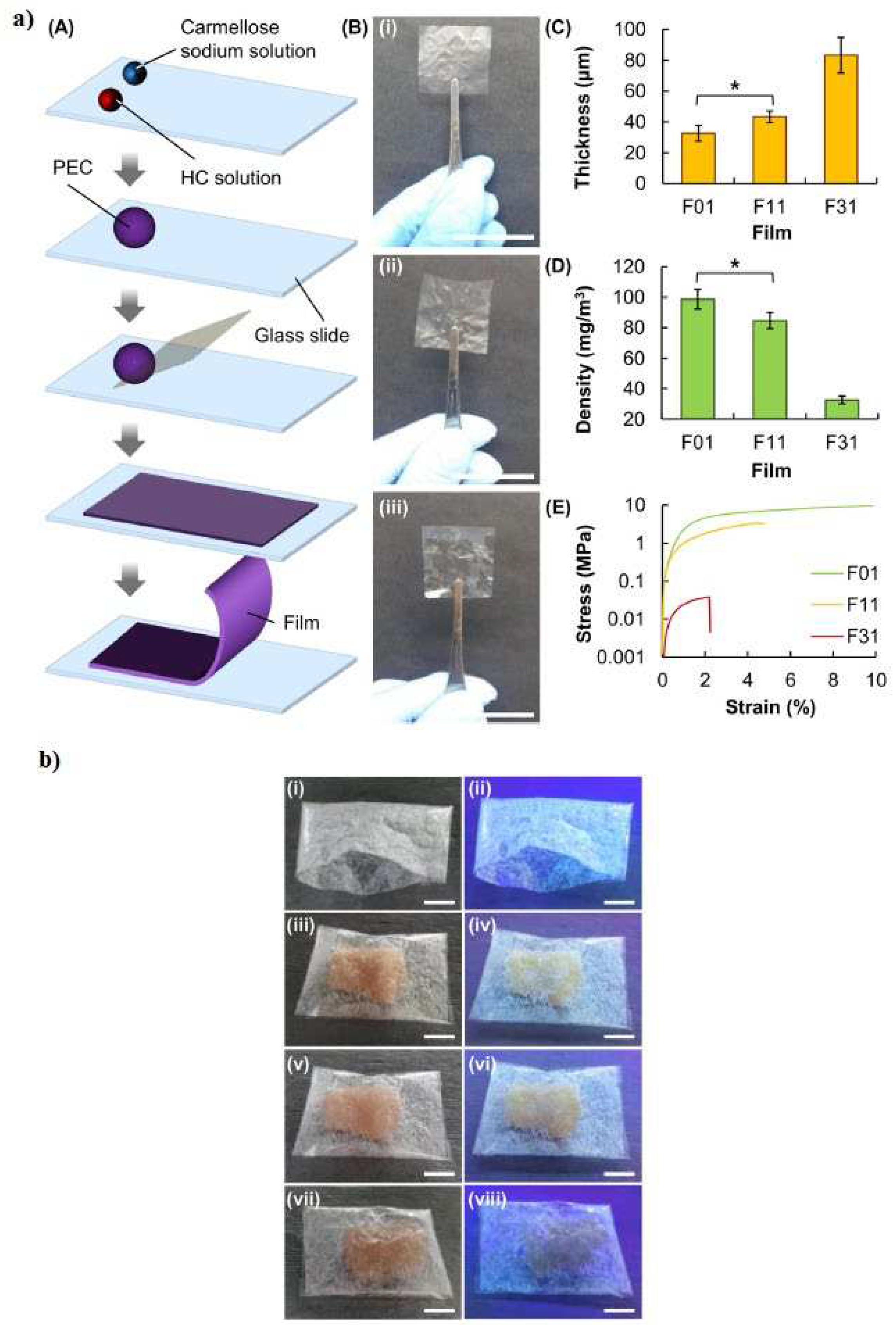

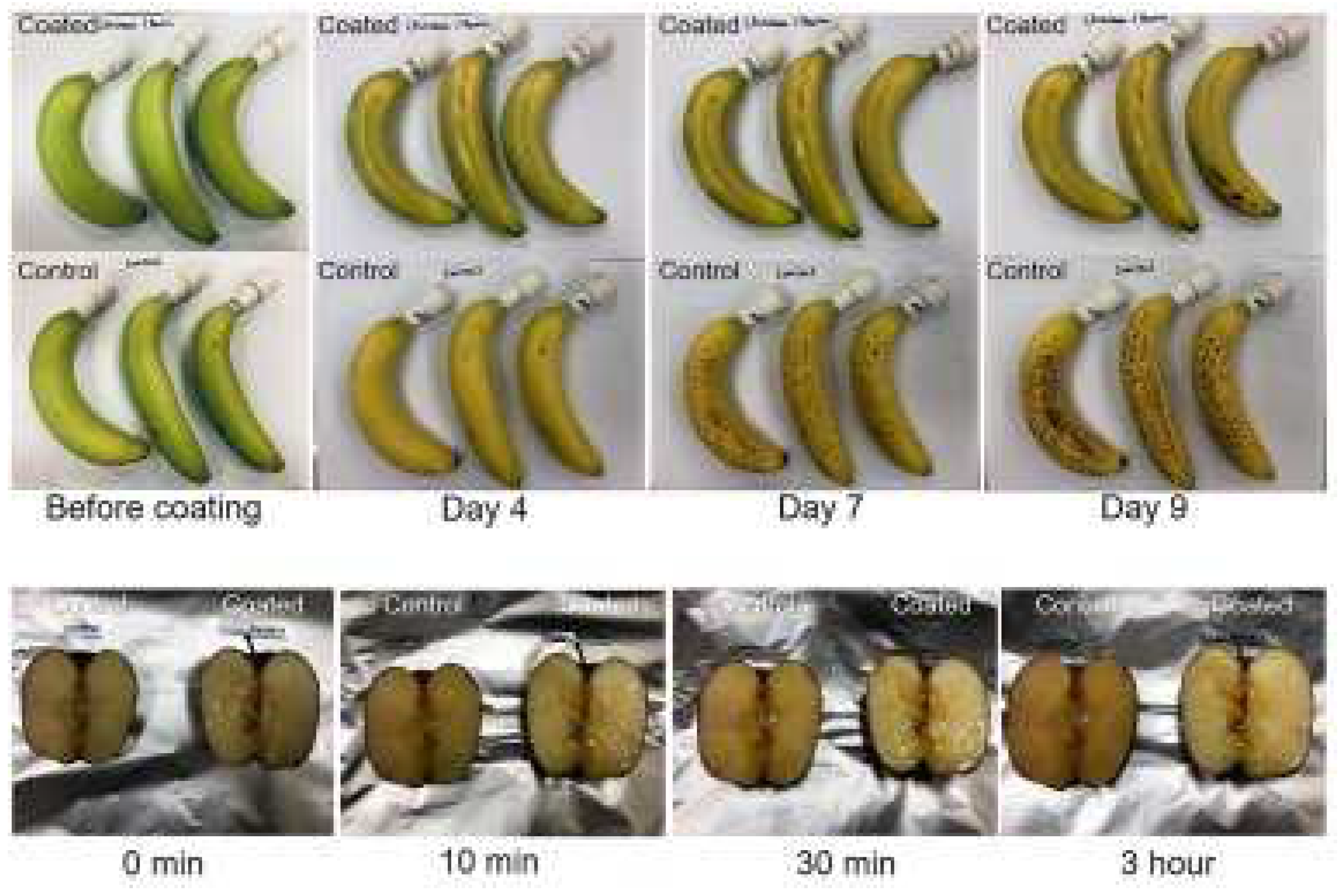

- Chiang, H.C.; Eberle, B.; Carlton, D.; Kolibaba, T.J.; Grunlan, J.C. Edible Polyelectrolyte Complex Nanocoating for Protection of Perishable Produce. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 495–499. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsfoodscitech.1c00097. [CrossRef]

- Ty, Q.; Li, S.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Hu, B.; Li, C. Cinnamon essential oil liposomes modified by sodium alginate-chitosan application chilled pork preservation. Int. J. Food Sci. Tecnol. 2023, 58, 939–953. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijfs.16140. [CrossRef]

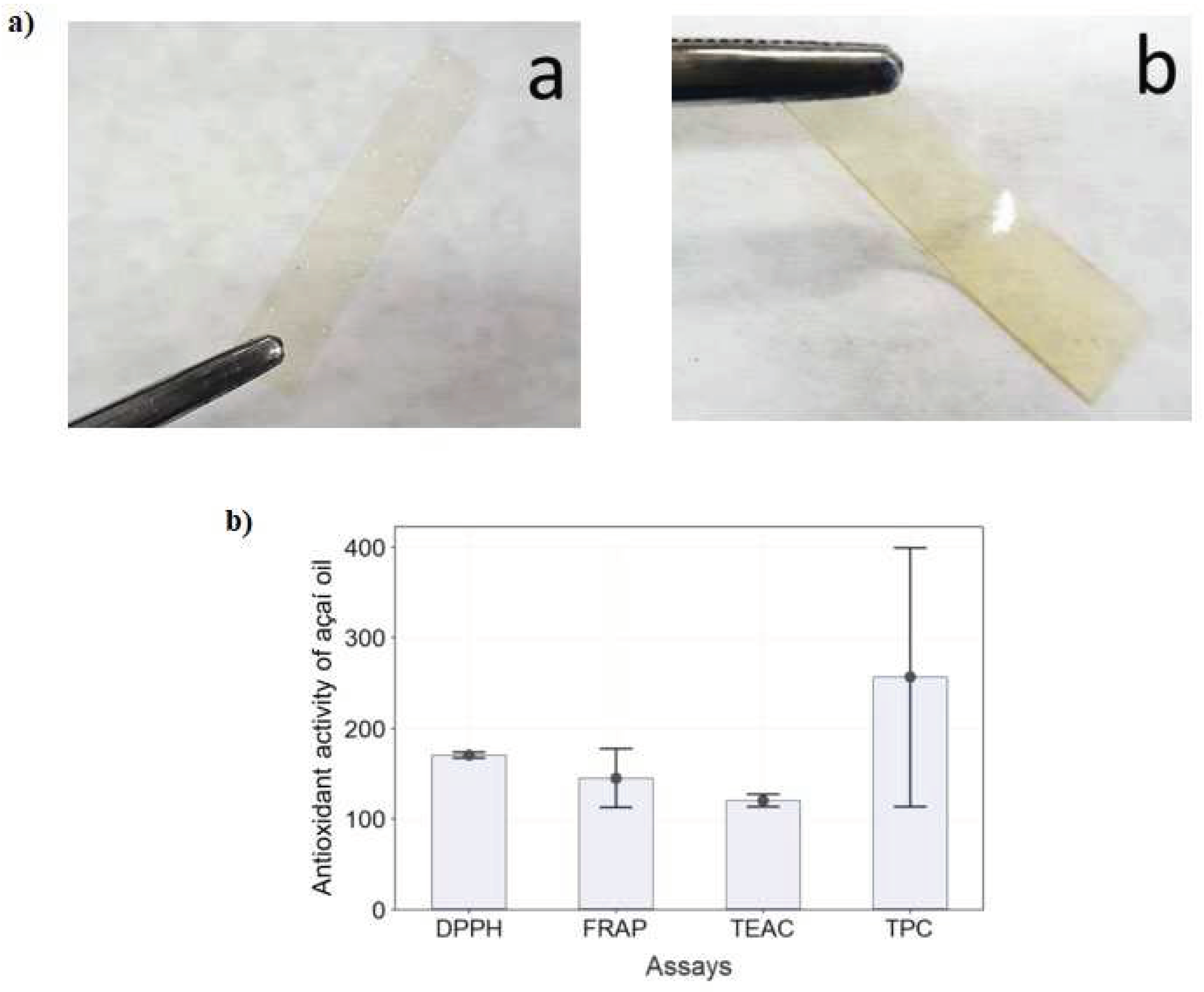

- Teixeira-Costa, B.E.; Ferreira, W.H.; Goycoolea, F.M.; Murray, B.S.; Andrade, C.T. Improved Antioxidant and Mechanical Properties of Food Packaging Films Based on Chitosan/Deep Eutectic Solvent, Containing Açaí-Filled Microcapsules. Molecules 2023, 28, 1507–1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28031507. [CrossRef]

- Goudar, N.; Vanjeri, V.N.; Hiremani, V.D.; Gasti, T.; Khanapure, S.; Masti, S.P.; Chougale, R.B. Ionically Crosslinked Chitosan/Tragacanth Gum Based Polyelectrolyte Complexes for Antimicrobial Biopackaging Applications. J. Polym. Environ. 2022, 30, 2419–2434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-021-02354-5. [CrossRef]

| Polyelectrolyte complex system/encapsulated molecule | Application | Ref. |

| Pea-protein succinylated-Chitosan/curcumin | Delivery of curcumin in a gastrointestinal system | [57] |

| Chitosan-alginate/assai pulp oil | Active food packaging | [58] |

| Casein-sodium alginate/vanillin | Delivery systems in various areas, such as food packaging, textile, cosmetic | [59] |

| Carboxymethylagarose-chitosan/diclofenac sodium | Wound dressing for transdermal drug delivery, tissue engineering. | [60] |

| Glycosaminoglycans-chitosan/mesenchymal stem cells | Applications in bioprinting, modular tissue engineering, or regenerative medicine. | [61] |

| Chitosan-fucoidan/platelet-rich plasma | Use in diabetic wound care. | [62] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).