1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) has become an increasingly popular topic in recent years, with its applications ranging from smart homes and cities to healthcare and industry. However, building and testing IoT systems can be challenging due to the diversity of devices and protocols involved. In order to address this challenge, IoT testbeds have been developed to provide a controlled environment for testing and evaluating IoT systems.

Experimental analysis of IoT systems requires a testbed to provide a controlled environment for testing and evaluating IoT systems. Testbeds can help in simulating realistic scenarios and collect data on system behavior. Smadi et al. (2021) [

1], noted the importance of using testbeds for experimental analysis of smart grid technologies. Similarly, wireless sensor networks (WSNs) have been extensively explored in the context of smart homes for monitoring and controlling various systems and appliances [

2,

3].

Smart buildings are becoming increasingly popular, with various applications being developed to manage and control building systems for improved efficiency, comfort and safety. Examples of such applications include smart energy management [

4] and smart HVAC controls [

5], which can benefit from the deployment of WSNs and IoT systems. In addition, the use of WSNs in smart homes has also been studied for energy-efficient management and control of appliances and lighting systems [

6,

7], as well as for monitoring indoor air quality, detecting gas leaks and preventing fire hazards in smart homes [

8,

9]. Our testbed follows this approach by providing a controlled environment for collecting real-time data from multiple sources and analyzing patterns of behavior through an abstraction layer provided by openHAB. OpenHAB is an open-source home automation platform that supports various protocols and devices, allowing easy integration and management of different systems and appliances in a smart home environment. It also allows users to build their own smart home automation systems and provides a flexible and extensible framework for integrating various IoT devices and services. Previous work has explored the use of openHAB in IoT testbeds [

10] and has demonstrated its potential for enabling universally usable smart homes [

1]. To give a thorough understanding of the current state-of-the-art in IoT platforms, we refer to a survey conducted on various IoT platforms [

11]. This survey delves into the communication, security and privacy perspectives of these platforms, providing insights into their strengths and weaknesses. Such a comparison is valuable for researchers and practitioners who are looking to develop or adopt an IoT platform that best suits their specific requirements. While all of these platforms have their strengths and weaknesses, openHAB was the right decision for this project for several reasons. Firstly, openHAB is an open-source platform that is highly customizable, which makes it easier to integrate with different sensors and devices. Additionally, openHAB supports a wide range of communication protocols and standards, including MQTT, REST, and CoAP, which enables seamless communication between different devices and applications. Furthermore, openHAB offers strong security features, such as authentication and authorization mechanisms, which help to protect the system against unauthorized access and data breaches. Finally, openHAB is free to use and does not require any licensing fees, which makes it a cost-effective option for building IoT systems.

The IoT testbed described in the current work utilizes a variety of wireless interfaces and sensors to collect data from various sources. The Z-Wave and ZigBee protocols are popular choices for home automation and have been used in several previous studies [

7,

8]. WiFi is a widely used wireless communication technology that is suitable for high-speed data transmission [

9]. 4G-LTE is a cellular communication technology that provides high-speed internet access and has been used in various IoT applications, such as smart transportation and healthcare [

12,

13]. IR wireless communication is widely used for remote control of home appliances.

The sensors used in the testbed include motion, temperature, luminance, humidity, vibration, UV, energy and switch sensors. These sensors are commonly used in IoT applications for monitoring and controlling various systems and appliances in smart homes, cities and industries. The openHAB platform is used as the underlying architecture to integrate these devices and protocols.

The main contributions of this paper are the design, implementation and evaluation of an IoT testbed for wireless sensor networks. The proposed testbed is based on the openHAB platform and provides a flexible and standardized solution for integrating various wireless protocols and sensors. Additionally, we provide a detailed description of the testbed architecture, the sensors used and the experimental setup. The results obtained from the experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed testbed for evaluating the performance of different wireless interfaces and sensors in an IoT environment. First a detailed description of the IoT testbed setup is provided, including the employed components and their functionalities. Then the openHab platform and its role in the IoT testbed is discussed. Next, the results of basic testing performed on the testbed are presented, including observations made and how they relate to the wireless systems and sensors used. Finally, we draw conclusions based on the results obtained and discuss future work that can be done to improve the IoT testbed.

2. Background

The growth of IoT has been exponential in recent years, with the number of connected devices expected to reach 75.44 billion by 2025, according to a report by Statista [

14]. As a result, there has been a proliferation of devices that use different wireless communication technologies to communicate with each other. Some of the most widely used wireless interfaces in IoT include Z-Wave, ZigBee, WiFi, 4G-LTE and IR.

Z-Wave is a wireless communication protocol specifically designed for home automation that operates on the 800-900 MHz frequency range and has a range of up to 100 meters [

15]. ZigBee, on the other hand, is a low-power wireless communication protocol that uses the IEEE 802.15.4 standard and is designed for low data rate applications with a range of up to 70 meters [

2]. It provides a mesh network that supports a wide range of applications, including home automation, lighting control and remote sensing.

WiFi is a ubiquitous wireless communication protocol that operates on the 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz frequency bands and has a range of up to 100 meters [

16].

4G-LTE is a mobile communication protocol that operates on the cellular network and has a range of several kilometers [

17]. Finally, IR is a wireless communication technology that uses infrared radiation to transmit signals and has a range of up to 10 meters.

Infrared (IR) is a line-of-sight wireless communication technology that uses infrared light to transmit signals. It is extensively used in consumer electronics, such as televisions and remote control devices.

Furthermore, various sensors are also used in IoT applications. Motion sensors detect changes in movement and are used in security and home automation applications. Temperature sensors measure environment temperature and are used in HVAC and weather monitoring applications. Luminance sensors measure brightness and are used in lighting control and energy management applications. Humidity sensors measure the moisture content in the air for environmental monitoring and control applications. Vibration sensors measure mechanical vibrations for machinery monitoring and maintenance applications. UV sensors measure ultraviolet light levels for environmental monitoring and control applications. Energy sensors measure the energy consumption of devices in energy management applications. Switch sensors are used to control the state of devices and are widely used in home automation applications.

In addition to the individual applications of various sensors, many IoT applications utilize a combination of sensors through the use of sensor fusion techniques. Sensor fusion is the process of combining data from multiple sensors to improve accuracy and provide a more comprehensive view of the environment being monitored. Examples of established IoT applications of sensor fusion include smart occupancy detection [

18], smart healthcare [

19] and smart transportation [

20]. These applications demonstrate the benefits of combining multiple sensor inputs and the potential for more advanced IoT systems.

The use of multiple wireless communication technologies in IoT devices poses challenges for interoperability and integration. Therefore, the need for testbeds that can handle the diversity of IoT devices and communication technologies has become increasingly important. Testbeds provide a controlled environment for testing and evaluating IoT systems, enabling researchers and developers to identify and address issues related to interoperability, security and reliability.

This paper presents an IoT testbed that integrates different wireless interfaces and sensors in an open architecture using the openHab platform. The open architecture of the testbed is essential to enable the integration of different wireless interfaces and sensors, which are often proprietary and use different communication protocols. By using an open platform like openHab, the testbed can accommodate a wide range of devices and protocols and facilitate the development of new IoT applications and services. Furthermore, it allows researchers and developers to evaluate the interoperability, security and reliability of IoT systems under various scenarios and conditions.

3. OpenHab Platform

The openHAB platform is an open-source platform that provides a vendor and technology-agnostic solution for integrating smart home devices [

21]. It is a popular platform that enables the communication between different devices and technologies, providing a standardized and flexible abstraction layer. The platform offers a variety of bindings that can be used to connect devices using different wireless protocols, such as ZigBee, Z-Wave, EnOcean and Wi-Fi [

10]. The openHAB platform is freely available for download and use from the official website at

www.openhab.org.

One of the key features of the openHAB platform is its user-friendly interface, which allows users to monitor and control the devices and systems connected to it. It offers real-time monitoring and access to the data collected by sensors, enabling users to create customized rules and automations that can be triggered by events or conditions, such as changes in temperature or motion [

22].

The openHAB platform's modular design is another key feature that allows users to easily add and remove devices and systems as needed [

23]. It supports a wide range of devices and systems and provides integration with popular services, such as Amazon Alexa and Google Assistant, for voice control [

24].

3.1. Persistence

The openHAB platform includes a powerful persistence layer that enables users to store and retrieve data generated by the devices and systems connected to the testbed. The persistence layer is based on a flexible and extensible architecture that supports a variety of storage options, including relational databases, NoSQL databases and cloud-based storage services. This allows users to choose the storage option that best suits their needs and provides the best performance for their particular use case.

The platform's persistence layer supports both historical and real-time data storage and retrieval [

25]. This means that users can store and retrieve data generated by sensors and devices over an extended period, as well as receive and analyze real-time data streams. The platform provides a variety of persistence services, including data aggregation, data filtering and data visualization, to help users analyze and interpret the data collected by their devices and systems.

The openHAB platform's persistence layer also provides support for data archiving and backup, ensuring that users can access their data even in the event of system failure or data loss [

25]. This makes the platform suitable for use in mission-critical applications, where data integrity and availability are paramount.

3.2. REST API

The openHAB platform provides a Representational State Transfer (REST) Application Programming Interface (API) that enables external programs to access and control various aspects of the system. This API allows for the retrieval of data related to Items, Things and Bindings, as well as the invocation of actions that can change the state of Items or influence the behavior of other elements of openHAB. The REST API provides a simple and standardized interface that can be accessed using the HTTP protocol, making it easy to integrate with other systems and applications.

By providing a REST API, the openHAB platform acts as an abstraction layer between the end user and the IoT technologies, enabling developers to focus on building applications without having to worry about the underlying complexities of the IoT system. This simplifies the process of building and integrating smart home applications, allowing developers to more easily create innovative new products and services [

26].

3.3. Functionalities

In addition to its persistence layer and the REST API, the openHAB platform provides a wide range of functionalities that enable the integration of different devices and sensors. Here are some of the main functionalities provided by the platform:

Rule Engine: The openHAB platform provides a powerful rule engine that allows for the automation of various actions based on the status of different devices and sensors. For example, if a motion sensor is triggered, the rule engine can automatically turn on the lights in the room.

User Interface: The platform provides a user-friendly web interface that can be used to monitor and control different devices and sensors. The interface can be accessed from a web browser or mobile app.

Integration with Third-party Services: The platform can be easily integrated with third-party services such as IFTTT, Amazon Alexa and Google Assistant. This allows for voice control and other advanced functionalities.

Flexibility: The openHAB platform is highly flexible and can be customized to meet the needs of different applications. It provides support for various protocols such as MQTT, Z-Wave, ZigBee and others.

Add-ons: The platform provides a wide range of add-ons that can be used to extend its functionalities. These add-ons include bindings for different devices and sensors, as well as user interfaces and rule templates.

3.4. Security Features

The proposed testbed uses openHAB as a security layer that controls user authentication and access control through various methods such as HTTPS, SSH and role-based access. Communication between the testbed and users is encrypted via SSL certificates and there are options for secure remote access, such as running openHAB behind a reverse proxy or setting up a VPN connection. It is worth noting that openHAB has built-in support for restricting access through HTTP(S) for certain users. These security features ensure that access to the testbed resources is carefully controlled and that communication with the testbed is secure.

Overall, the openHab platform provides a comprehensive, flexible and secure solution for managing and controlling different devices and systems in an IoT environment. Its persistence layer and functionalities, such as event management, real-time monitoring and customization, make it an ideal platform for an IoT. Additionally, openHAB includes robust security features, such as user authentication and access control through various methods, encryption of communication via SSL certificates and built-in support for restricting access through HTTP(S) for certain users. These security measures help to ensure the safety and privacy of the data collected and transmitted by the IoT testbed, making it a valuable tool for evaluating the performance and compatibility of different wireless interfaces and sensors.

4. Description of the Testbed

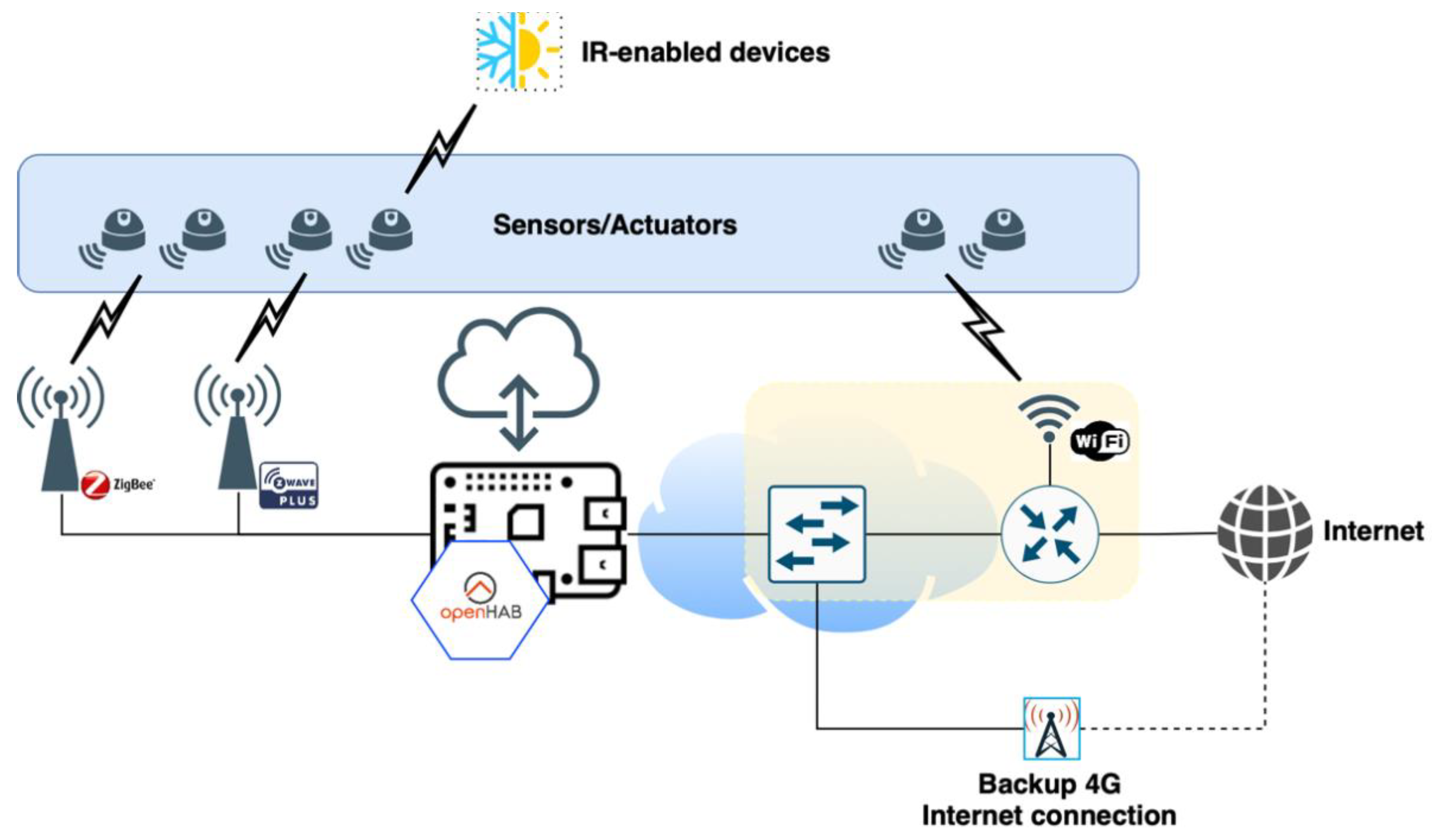

Figure 1 shows the high-level design of the testbed topology. The IoT testbed used in this paper integrates different wireless interfaces, such as Z-Wave, ZigBee, WiFi, 4G-LTE and IR and various sensor capabilities, including motion, temperature, luminance, humidity, vibration, UV, energy and switch sensors, in an open architecture using the openHab platform. The testbed is designed to provide a platform for evaluating the performance and compatibility of different wireless interfaces and sensors in a real-world setting.

Table 1 summarizes the different sensors and actuators used in the testbed.

The Z-Wave, ZigBee, WiFi and 4G-LTE interfaces are implemented using compatible devices, such as controllers, routers, smart switches and smart sensors. It is important to note that the 4G-LTE interface is being utilized as an alternative internet connection in case the WiFi or Ethernet connection is disrupted. This provides a backup option for maintaining connectivity to the IoT testbed and ensures that data can continue to be collected and analyzed even in the event of a network outage. The IR interface is implemented using IR emitters and receivers and is being utilized mainly to control A/C units in order to maintain the desired temperature and humidity levels.

The openHab platform serves as the central management system for the IoT testbed. It integrates the different wireless interfaces and sensors and provides a unified and flexible way to manage and control them. It also provides a user-friendly interface for monitoring and controlling the testbed and accessing the data collected by the sensors.

The testbed was established within a controlled laboratory environment, that measures 5x7 meters, to minimize the impact of external factors on the results. The devices and sensors were configured and tested to ensure that they were functioning properly and communicating with the openHab platform. To provide a visual representation of the testbed setup, a photo of the system has been included in

Figure 2.

The testbed has been extensively tested and evaluated over a six month period, demonstrating its capabilities and potential for various IoT applications. A use case of a typical day in the lab is presented in the following section 6, illustrating the data collected from multiple sensors and their correlations, which showcases the versatility and potential of the testbed.

5. Basic Testing

To evaluate the performance of the IoT testbed, a series of basic tests focused on the functionality of the different wireless interfaces and sensors were conducted in a controlled environment. The aim of these tests was to ensure that the wireless interfaces and sensors were functioning correctly and were able to communicate with the openHAB platform. The collected data was analyzed to determine if the sensors were producing accurate and reliable data.

One of the key tests performed was to verify the connectivity and functionality of the wireless protocols supported by the testbed, such as ZigBee, Z-Wave and Wi-Fi. Tests were also conducted to ensure the compatibility of the wireless protocols with different types of sensors and actuators. These tests were necessary to confirm that the devices could communicate with the openHAB platform and be controlled by it.

To evaluate the accuracy and reliability of the data collected by the sensors, tests were conducted to measure the precision and repeatability of the sensor readings. These tests ensured that the sensors produced consistent and reliable data, which is essential for the success of any IoT application.

The collected data was analyzed using statistical methods and the results were compared to the expected values for the sensors under test. These tests allowed for the identification of any errors or inaccuracies in the sensor readings.

Several studies have reported on the importance of conducting basic testing to evaluate the performance of IoT systems. For example, in a study by Smadi et al. (2021) [

1], basic testing was performed to verify the reliability of wireless communication in a smart home environment. Similarly, in a study by Tamilselvi et al. (2020) [

27], basic testing was conducted to evaluate the performance of an IoT-based healthcare monitoring system.

For the wireless interfaces, we tested their connectivity, reliability and range. The Z-Wave and ZigBee interfaces provided a stable and reliable connection within their specified range, while the WiFi interface provided good coverage and high bandwidth. The 4G-LTE capability was tested as a backup scenario for situations where the WiFi or Ethernet connection was disrupted and it proved to be a reliable alternative internet connection. To test the reliability of the IR interface, we used the IR bridge to send commands to air conditioning (A/C) units of different brands and monitored their response. The tests were successful, indicating the suitability of the IR interface for controlling temperature and humidity.

We have not performed a formal analysis to compare the accuracy and precision of each sensor, because we believe it is more valuable for the testbed to demonstrate the integration of different technologies and sensors/actuators. Therefore, we have showcased a typical day use case that utilizes environment data from various technologies and sensors to show their integration and correlation. This use case demonstrates the potential benefits of utilizing an open architecture platform, such as openHAB, which enables seamless integration of different technologies and sensors and provides an abstraction layer that simplifies the end-user experience.

6. Results

In this study, we conducted basic testing on our IoT testbed with different wireless interfaces and sensors. The testing was realized using the topology illustrated in

Figure 1, which shows the communication setup between the various devices in the testbed. The results of the testing are presented below.

6.1. Wireless Interfaces:

The Z-Wave interface demonstrated a range of up to 30 meters in an open space environment, with successful transmission of motion sensor data to the Z-Wave controller at distances up to 25 meters.

The ZigBee interface demonstrated a range of up to 50 meters in an open space environment, with successful transmission of temperature sensor data to the ZigBee coordinator at distances up to 40 meters.

The WiFi and 4G-LTE interfaces showed high reliability, with a packet delivery success rate of 99% for both interfaces.

The IR interface demonstrated reliable transmission and reception of commands between the remote control and IR receiver within a range of 10 meters.

6.2. Case Study: A Day in the Testbed:

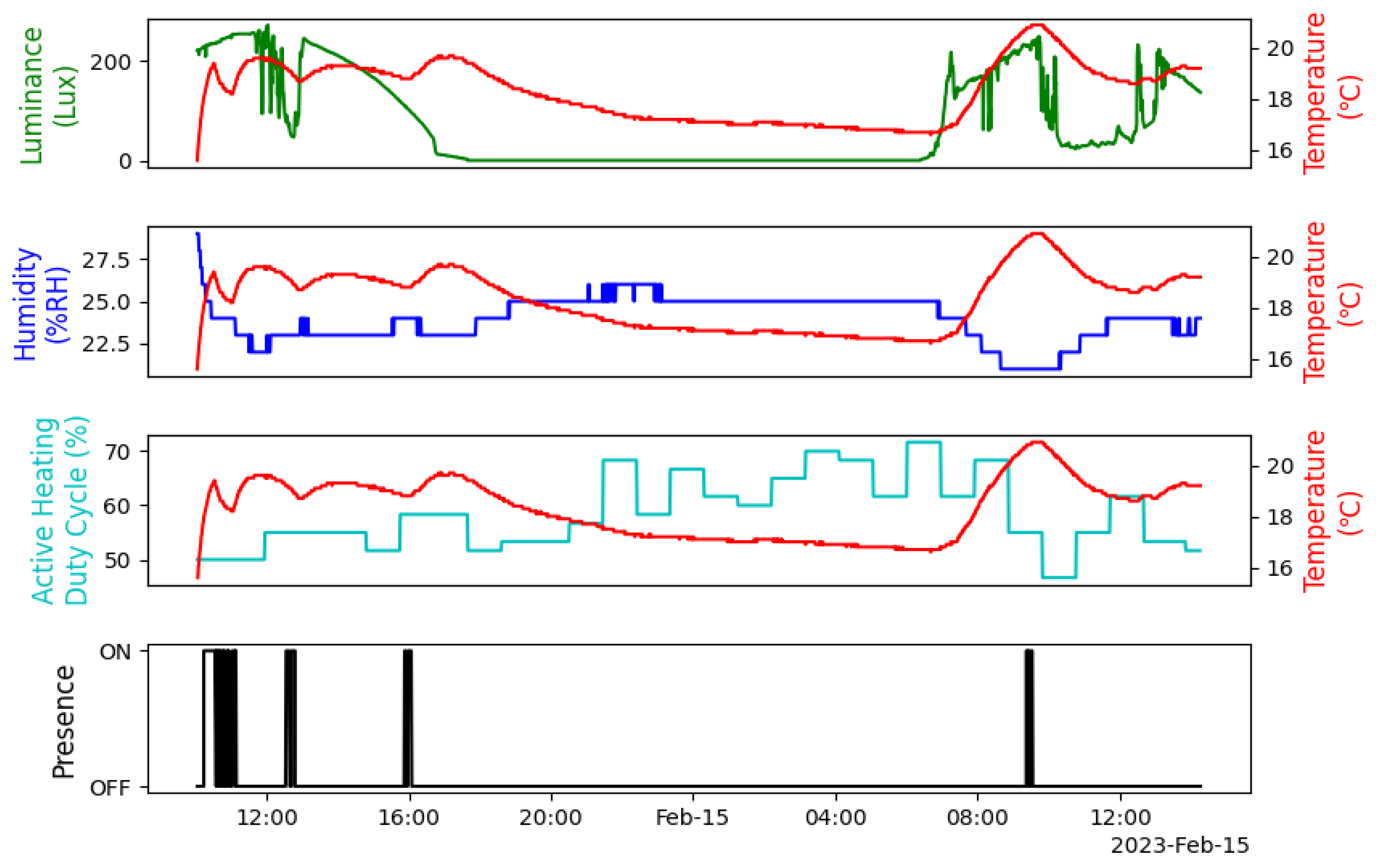

In order to demonstrate the capabilities of the testbed, a typical day in the lab was monitored and recorded using various sensors and actuators. This is illustrated in

Figure 2, which shows the average temperature, humidity, luminance and power consumption of an electrical heater across all sensor types, as well as motion detection data. The first two subplots depict a combined plot of luminance and temperature and humidity and temperature, respectively. The third subplot shows a combined plot of active heating duty cycle and temperature, while the fourth subplot is a plot of motion detected during the day. Note that the lab was equipped with various types of sensors, including UV sensors. However, due to the UV protection in the lab environment, the data from the UV sensors did not provide significant information and were therefore omitted from the figure. The collected data from various types of sensors showed a strong correlation between the humidity, luminance and power consumption of an electrical heater with the ambient temperature in the lab.

Furthermore, the abstraction layer generated by openHAB allowed for easy integration and analysis of data from various wireless technologies, enabling end-users to make informed decisions for optimizing energy consumption in their respective environments.

Figure 2.

Subplot 1: Luminance and Temperature; Subplot 2: Humidity and Temperature; Subplot 3: Active Heating Duty Cycle and Temperature; Subplot 4: Motion Detection.

Figure 2.

Subplot 1: Luminance and Temperature; Subplot 2: Humidity and Temperature; Subplot 3: Active Heating Duty Cycle and Temperature; Subplot 4: Motion Detection.

The use case demonstrated the testbed's ability to identify correlations between different variables and patterns of behavior and the potential for using this information to improve energy efficiency and occupant comfort. It should be noted that although UV sensors were included in the testbed, their data were not included in the results presented in this paper. This is because the laboratory environment where the testbed was installed was designed to provide UV protection, resulting in low levels of UV radiation. As a result, the UV sensor values did not show any significant changes during the monitoring period.

7. Further Work

In addition to the basic testing and evaluation of the IoT testbed using different wireless interfaces and sensors, a comprehensive gap analysis was conducted to identify the need for improved data collection methods in energy assets. As a result, a subset of the sensors in the Z-Wave technology area were selected as a proposed technical solution for deploying additional equipment to facilitate the realization of the SYNERGIES project demonstration cases [

28]. This solution has the potential to improve data collection methods for energy assets and can be further developed and optimized in future research.

The proposed solution is expected to improve data collection methods for energy assets by providing more accurate and real-time data on energy consumption and usage patterns [

7,

29]. This will enable more effective energy management strategies to be developed and implemented, resulting in improved energy efficiency and cost savings. However, further research is needed to optimize and refine the proposed solution and to evaluate its performance in real-world settings.

Future research could also explore the potential of other emerging technologies, such as blockchain and edge computing, in improving data collection and energy management in IoT systems [

30]. These technologies have shown promise in addressing some of the challenges associated with data security, privacy and processing in IoT systems and could potentially be used to enhance the performance and functionality of the proposed solution.

Future work could also focus on exploring other potential use cases for the IoT testbed, such as the development of custom applications and integrations using the openHAB platform and the REST API. Additionally, further testing and evaluation could be conducted to assess the scalability and reliability of the IoT testbed, as well as the performance of different wireless interfaces and sensors in other real-world operational environments. Some directions for future work that could further enhance the capabilities of the testbed:

Expansion of Sensor Types: Additional sensors, such as gas sensors or sound sensors, could be added to further expand the capabilities of the testbed and enable more complex scenarios [

31].

Integration with Machine Learning Techniques: Machine learning techniques, such as anomaly detection or predictive analytics, could be used to analyze the data collected from the testbed and derive insights that could be used to optimize the performance of the system. Several studies have shown the potential of machine learning in smart building energy management [

32]. By applying these techniques to the data collected by the testbed, we can develop more accurate and efficient algorithms for controlling heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems, as well as other building systems.

Real-world Testing: While the basic testing presented in this paper provides a solid foundation, more extensive testing and field trials (at least one year) in additional real-world scenarios could provide valuable insights into the system's performance [

33].

Security Testing: As IoT systems become more prevalent, security becomes an increasingly important concern and the use of open-source platforms can introduce unique security challenges. As highlighted in the survey conducted by [

34], security is a key aspect of IoT platforms and is often prioritized in open-source solutions due to the high degree of community involvement and code transparency. In this work, we have addressed these security concerns by adopting the open-source platform openHAB and implementing various security features, such as authentication and encryption protocols. However, we also acknowledge that the adoption of open-source tools and libraries can introduce potential challenges and pitfalls. Future work could involve conducting security testing to identify potential vulnerabilities and mitigate them [

35,

36].

ntegration with Cloud Services: Integrating the testbed with cloud services, such as Amazon Web Services or Microsoft Azure, could further enhance the capabilities of the system and enable more complex scenarios [

37].

8. Conclusions

In this paper, we presented an IoT testbed with different wireless interfaces and sensors in an open architecture with the openHab platform. The testbed demonstrated high reliability and accuracy in the basic testing conducted. The Z-Wave and ZigBee interfaces demonstrated good range, while the WiFi and 4G-LTE interfaces showed high reliability. The typical day use case has showcased the functionalities of the REST API serving as an abstraction layer between the end-users and the IoT technologies and providing a simplified interface for data access and control. This approach has significant benefits in terms of system scalability, interoperability and ease of use.

The IoT testbed presented in this paper is a valuable contribution to the field of IoT research. As the Internet of Things continues to grow and evolve, there is an increasing need for reliable and efficient IoT systems. By conducting further research and testing in more complex scenarios, we can continue to improve the performance and reliability of IoT systems, such as the one presented in this paper. The integration of machine learning techniques has been shown to be a promising approach to analyzing the collected data and deriving insights that can be used to optimize the performance of the system. Several studies have demonstrated the potential of machine learning in IoT applications, such as smart building energy management [

38]. Therefore, the integration of machine learning techniques in the IoT testbed presented in this paper could be a valuable avenue for future research.

Moreover, the system's scalability, interoperability and ease of use, achieved through the REST API, make it an attractive option for a wide range of IoT applications. These benefits are consistent with previous research on the use of open architectures and REST APIs in IoT systems [

39]. Therefore, the IoT testbed presented in this paper has the potential to serve as a valuable resource for researchers and practitioners in the field of IoT.

Overall, the IoT testbed presented in this paper has the potential to enable the development of more complex IoT systems and applications. By providing a platform for researchers and developers to test and evaluate different wireless interfaces and sensors in an open architecture, we can continue to push the boundaries of what is possible in the field of IoT.

Supplementary Materials

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, S.T., G.T., D.K. G.A.; methodology, S.T., G.T., D.K. G.A.; software, S.T.; validation, S.T., G.T., D.K.; formal analysis, S.T.; investigation, S.T.; resources, G.T., G.A.; data curation, S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T.; writing—review and editing, S.T., G.T., G.A.; visualization, S.T.; supervision, G.T.; project administration, G.T.; funding acquisition, G.T., G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

Part of this research was funded by the EU HORIZON Innovation Actions - Sustainable, secure and competitive energy supply CL-5-2021-D3-01, Grant Agreement: 101069839.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Part of this work was performed in the context of the HORIZON project SYNERGIES and as such the authors would like to thank the SYNERGIES consortium.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Smadi, A.A.; Ajao, B.T.; Johnson, B.K.; Lei, H.; Chakhchoukh, Y.; Abu Al-Haija, Q. A Comprehensive Survey on Cyber-Physical Smart Grid Testbed Architectures: Requirements and Challenges. Electronics (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Choi, C.; Park, W.; Lee, I.; Kim, S. Smart Home Energy Management System Including Renewable Energy Based on ZigBee and PLC. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2014, 60, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontaxis, D.; Tsoulos, G.; Athanasiadou, G.; Giannakis, G. Wireless Sensor Networks for Building Information Modeling. Telecom 2022, 3, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekler, Z.D.; Low, R.; Yuen, C.; Blessing, L. Plug-Mate: An IoT-Based Occupancy-Driven Plug Load Management System in Smart Buildings. Build Environ 2022, 223, 109472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, D.; Gan, V.J.L.; Duygu Tekler, Z.; Chong, A.; Tian, S.; Shi, X. Data-Driven Predictive Control for Smart HVAC System in IoT-Integrated Buildings with Time-Series Forecasting and Reinforcement Learning. Appl Energy 2023, 338, 120936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunhare, P.; Chowdhary, R.R.; Chattopadhyay, M.K. Internet of Things and Data Mining: An Application Oriented Survey. Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences 2022, 34, 3569–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, A.R.; Zualkernan, I.A.; Rashid, M.; Gupta, R.; Alikarar, M. A Smart Home Energy Management System Using IoT and Big Data Analytics Approach. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2017, 63, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Du, X.; Guizani, M. Big Data Mining of Users’ Energy Consumption Patterns in the Wireless Smart Grid. IEEE Wirel Commun 2018, 25, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, A.; Roy, A.; Mathew, J. Intelligent Residential Energy Management System Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Syst J 2020, 14, 5362–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirek, L.G.Z. and D.Z. Towards Universally Usable Smart Homes-How Can Myui, Urc and Openhab Contribute to an Adaptive User Interface Platform. IARIA 2014.

- Babun, L.; Denney, K.; Celik, Z.B.; McDaniel, P.; Uluagac, A.S. A Survey on IoT Platforms: Communication, Security, and Privacy Perspectives. Computer Networks 2021, 192, 108040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuramalingam, S.; Bharathi, A.; Rakesh kumar, S.; Gayathri, N.; Sathiyaraj, R.; Balamurugan, B. IoT Based Intelligent Transportation System (IoT-ITS) for Global Perspective: A Case Study. In; 2019; pp. 279–300.

- Bhuiyan, M.N.; Rahman, M.M.; Billah, M.M.; Saha, D. Internet of Things (IoT): A Review of Its Enabling Technologies in Healthcare Applications, Standards Protocols, Security, and Market Opportunities. IEEE Internet Things J 2021, 8, 10474–10498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonmaker, S. Number of Internet of Things (IoT) Devices Worldwide from 2019 to 2025 (in Billions). Retrieved from Https://Www.Statista.Com/Statistics/471264/Iot-Number-of-Connected-Devices-Worldwide/; 2021.

- Al-Sarawi, S.; Anbar, M.; Alieyan, K.; Alzubaidi, M. Internet of Things (IoT) Communication Protocols: Review. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th International Conference on Information Technology (ICIT); IEEE, May 2017; pp. 685–690. [Google Scholar]

- Karunarathne, G.G.K.W.M.S.I.R.; Kulawansa, K.A.D.T.; Firdhous, M.F.M. Wireless Communication Technologies in Internet of Things: A Critical Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Intelligent and Innovative Computing Applications (ICONIC); IEEE, December 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hassebo, A.; Obaidat, M.; Ali, M.A. Commercial 4G LTE Cellular Networks for Supporting Emerging IoT Applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET); IEEE, February 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tekler, Z.D.; Chong, A. Occupancy Prediction Using Deep Learning Approaches across Multiple Space Types: A Minimum Sensing Strategy. Build Environ 2022, 226, 109689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoneem, R.M.; Shaaban, E.; Benslimane, A. A Survey on Multi-Sensor Fusion Techniques in IoT for Healthcare. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Systems (ICCES); IEEE, December 2018; pp. 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Low, R.; Tekler, Z.D.; Cheah, L. Predicting Commercial Vehicle Parking Duration Using Generative Adversarial Multiple Imputation Networks. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2020, 2674, 820–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunge, V.S. , and P.S.Y. Smart Home Automation: A Literature Review. Int J Comput Appl. 2016, 975.8887.

- Abdelouahid, R.A.; Debauche, O.; Marzak, A. Internet of Things: A New Interoperable IoT Platform. Application to a Smart Building. Procedia Comput Sci 2021, 191, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edu, J.S.; Such, J.M.; Suarez-Tangil, G. Smart Home Personal Assistants. ACM Comput Surv 2021, 53, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkholy, M.H. and S.T. and L.M.E. and E.A. and A.N.S. and G.T.S. Design and Implementation of a Real-Time Smart Home Management System Considering Energy Saving. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, R.; Blackstock, M. City Hub: A Cloud-Based IoT Platform for Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 6th International Conference on Cloud Computing Technology and Science; IEEE, December 2014; pp. 799–804. [Google Scholar]

- Sowah, R.A.; Boahene, D.E.; Owoh, D.C.; Addo, R.; Mills, G.A.; Owusu-Banahene, W.; Buah, G.; Sarkodie-Mensah, B. Design of a Secure Wireless Home Automation System with an Open Home Automation Bus (OpenHAB 2) Framework. J Sens 2020, 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilselvi, V.; Sribalaji, S.; Vigneshwaran, P.; Vinu, P.; GeethaRamani, J. IoT Based Health Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS); IEEE, March 2020; pp. 386–389. [Google Scholar]

- 28. SYNERGIES - Coordinating Energy-Efficiency and Demand Response Actions in the Building Sector. Available: Https://Synergies-Project.Eu/. EU Horizon 2020 SYNERGIES project 2020.

- Wang, X.; Mao, X.; Khodaei, H. A Multi-Objective Home Energy Management System Based on Internet of Things and Optimization Algorithms. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 33, 101603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Ni, Y.; Gu, L.; Zhu, H. Blockchain for the IoT and Industrial IoT: A Review. Internet of Things 2020, 10, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbi, J.; Buyya, R.; Marusic, S.; Palaniswami, M. Internet of Things (IoT): A Vision, Architectural Elements, and Future Directions. Future Generation Computer Systems 2013, 29, 1645–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Qin, S.; Zhang, M.; Shen, C.; Jiang, T.; Guan, X. A Review of Deep Reinforcement Learning for Smart Building Energy Management. IEEE Internet Things J 2021, 8, 12046–12063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, K.E.; Kelly, M.Y.; Nolan, M.; Brady, J.; Guibene, W. Techniques for Resilient Real-World IoT. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC); IEEE, September 2016; pp. 222–226. [Google Scholar]

- Soldatos, J., C. M., S.R., & R.D. The Internet-of-Things Open Source Ecosystem in 2021. 2020.

- Roman, R.; Zhou, J.; Lopez, J. On the Features and Challenges of Security and Privacy in Distributed Internet of Things. Computer Networks 2013, 57, 2266–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, R.E.; Le Bouder, H.; Cuppens, N.; Cuppens, F.; Papadopoulos, G.Z. Demo: Do Not Trust Your Neighbors! A Small IoT Platform Illustrating a Man-in-the-Middle Attack. In; 2018; pp. 120–125.

- Wan, J.; Chen, M.; Xia, F.; Di, L.; Zhou, K. From Machine-to-Machine Communications towards Cyber-Physical Systems. Computer Science and Information Systems 2013, 10, 1105–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djenouri, D.; Laidi, R.; Djenouri, Y.; Balasingham, I. Machine Learning for Smart Building Applications. ACM Comput Surv 2020, 52, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelby, Z. and H.K. and B.C. The Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP). No. Rfc7252. 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).