Submitted:

02 June 2023

Posted:

05 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

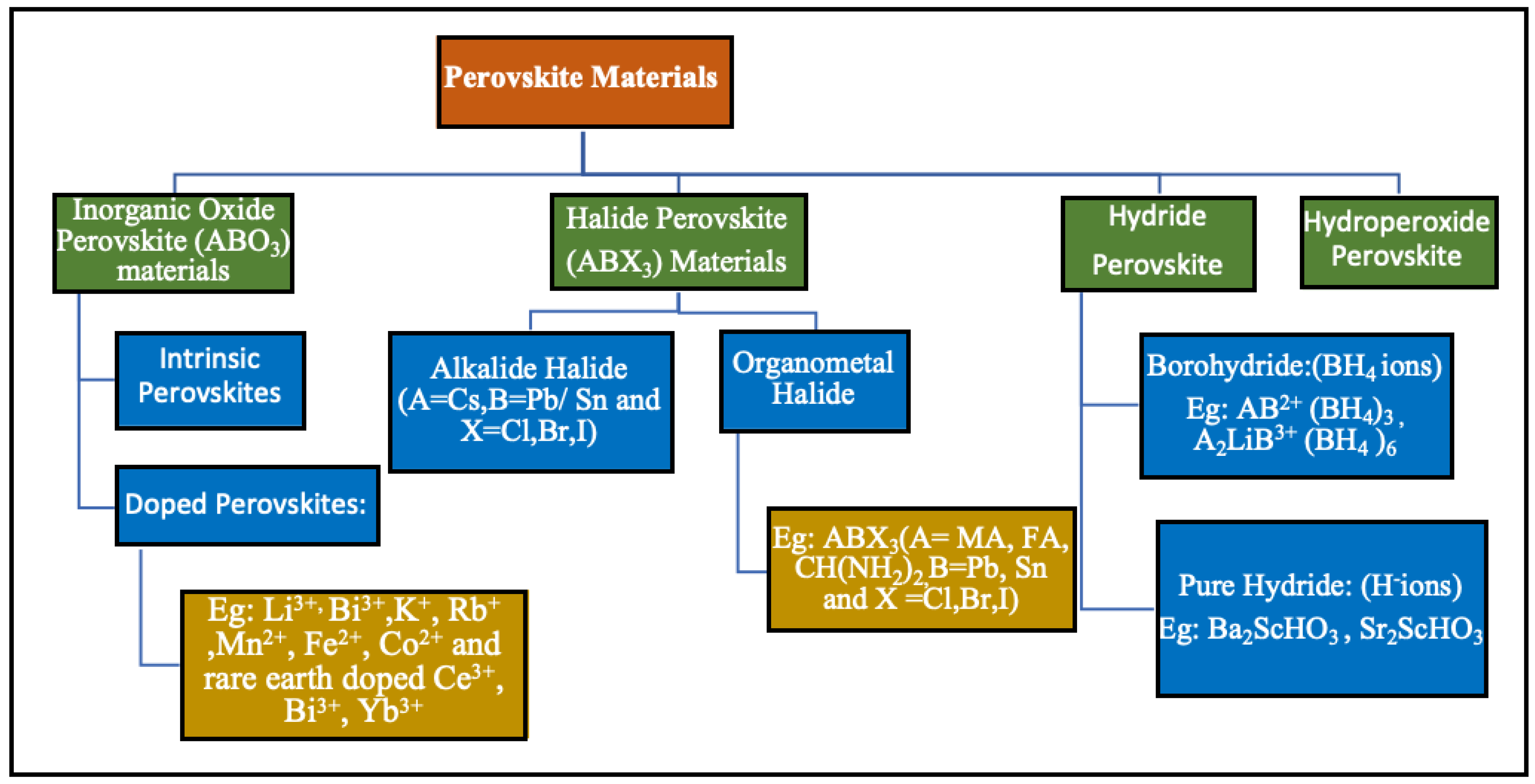

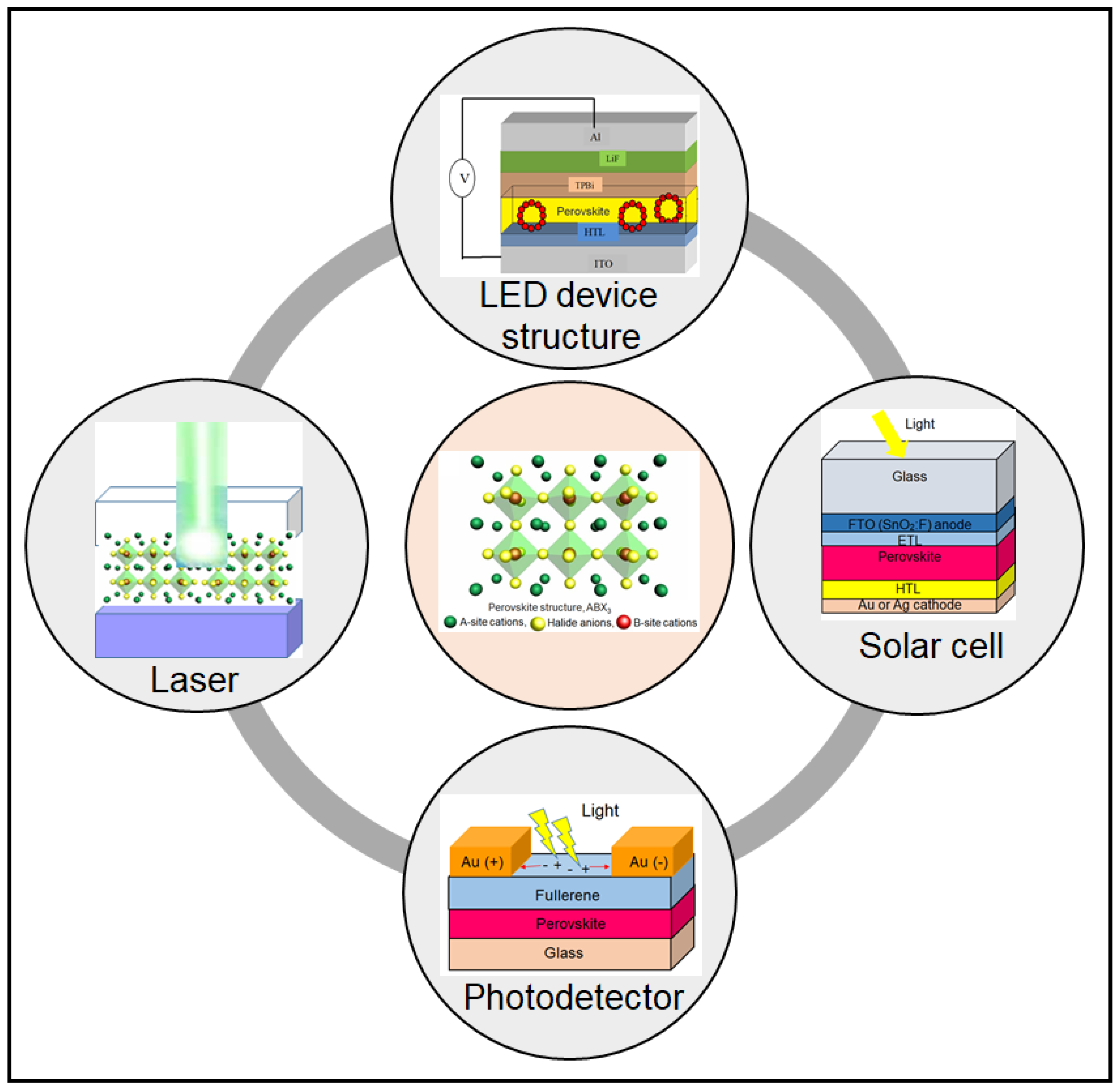

2. Perovskite Materials

3. Evolution of Perovskite for Solar Cells

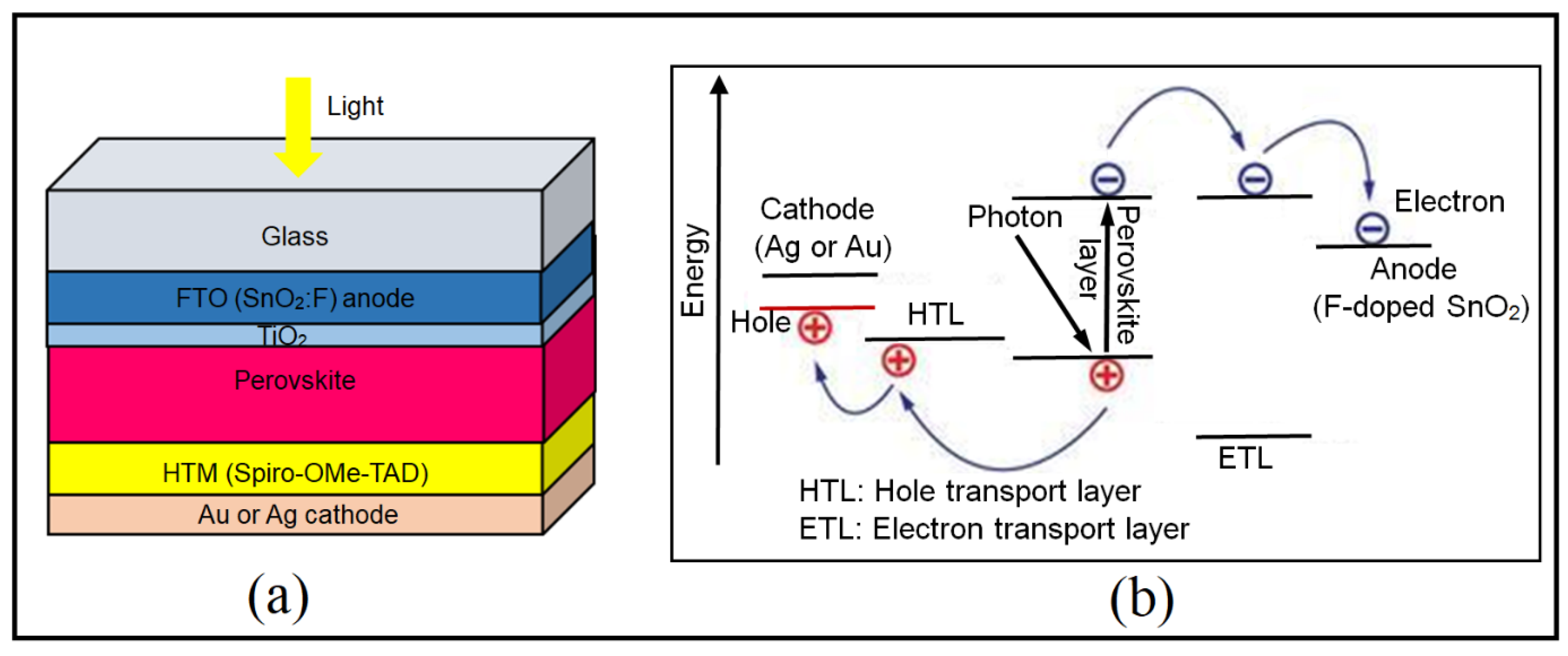

3.1. Inorganic Perovskites Solar Cells

3.2. Hybrid Perovskite Materials Solar Cell

3.3. Materials Requirements for High Performance Solar Cell Devices

4. Perovskite Materials Concern for Solar Cell Applications

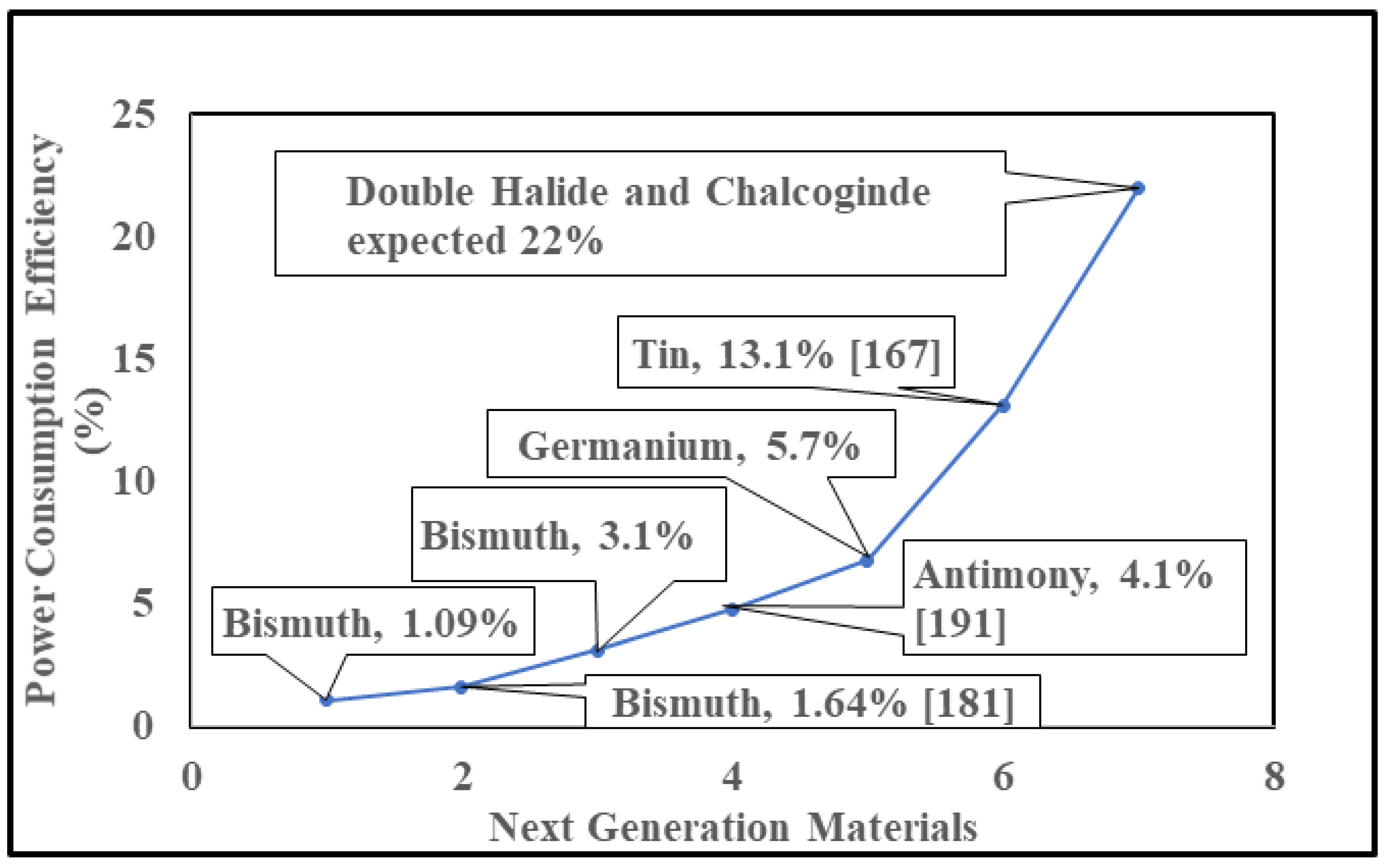

Sn-Based Solar Cells

Bi-Based Solar Cells

Sb-Based Solar Cells

Ge-Based Solar Cells

Double Perovskite Solar Cells

Chalcogenide Perovskites Solar Cells

5. Issues and Challenges in Perovskite Solar Cells

5.1. Perovskite Structural Stability Perspective

5.2. Device Fabrication Issues

5.3. Lifetime and Stability under High Temperature and Humidity

5.4. Alternatives to the Toxic Heavy Metal Lead

Future Perovskite Materials - Machine Learning Approach

5.5. Manufacturing Cost

Panel Cost Analysis

6. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nunez, C. Learn how human use of Fossil Fuel non-renewable energy resources coal, oil, and natural gas-affect climate change. National Geographic, April-2, 2019. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/fossil-fuels.

- United Nations Climate Change Conference, Glasgow, UK from 31 October-13 November 2021. Available online: https://earth5r.org/cop26-the-negotiations-explained/.

- Shockley, W.; Queisser, H.J. Detailed balance limit of efficiency of p-n junction solar cells. Journal of applied physics 1961, 32, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akihiro, K.; Teshima, K.; Shirai, Y.; Miyasaka, T. Organometal halide perovskites as visible-light sensitizers for photovoltaic cells. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2009, 131, 6050–6051. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.A.; Ho-Baillie, A.; and Henry, J.; Snaith, H.J. The emergence of perovskite solar cells. Nature photonics 2014, 8, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaith, H.J. Perovskites: the emergence of a new era for low-cost, high-efficiency solar cells. The journal of physical chemistry letters 2013, 4, 3623–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.-G. Perovskite solar cells: an emerging photovoltaic technology. Materials today 2015, 18, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, B.; Pellet, N.; Moon, S.-J.; Humphry-Baker, R.; Gao, P.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Grätzel, M. Sequential deposition as a route to high-performance perovskite-sensitized solar cells. Nature 2013, 499, 316–319. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Anaya, M.; Lozano, G.; Calvo, M.E.; Johnston, M.B.; Míguez, H.; Snaith, H.J. Highly efficient perovskite solar cells with tunable structural color. Nano letters 2015, 15, 1698–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Huang, T.; Xue, J.; Tong, J.; Zhu, K.; Yang, Y. Prospects for metal halide perovskite-based tandem solar cells. Nature Photonics 2021, 15, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eike, K.; Wagner, P.; Lang, F.; Cruz, A.; Li, B.; Roß, M.; Jošt, M.; Morales-Vilches, A.B.; Topič, M.; Stolterfoht, M.; et al. 27.9% Efficient Monolithic Perovskite/Silicon Tandem Solar Cells on Industry Compatible Bottom Cells. Solar RRL 2021, 2100244. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, E.A. Perovskite: name puzzle and German-Russian odyssey of discovery. Helvetica Chimica Acta 2020, 103, e2000061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschmidt, V.M. Die gesetze der krystallochemie. Naturwissenschaften 1926, 14, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halasyamani, P.S.; Noncentrosymmetric Inorganic Oxide Materials: Synthetic Strategies and Characterization Techniques. In Functional Oxides, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Book Editor(s): O’Hare, D.; Walton, R.I.; Bruce, D.W. 2010, 1-40. Print ISBN:9780470997505.

- Goel, P.; Sundriyal, S.; Shrivastav, V.; Mishra, S.; Dubal, D.P.; Kim, K.-H.; Deep, A. Perovskite materials as superior and powerful platforms for energy conversion and storage applications. Nano Energy 2021, 80, 105552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locock, A.J.; Mitchell, R.H. Perovskite classification: An Excel spreadsheet to determine and depict end-member proportions for the perovskite-and vapnikite-subgroups of the perovskite supergroup. Computers & Geosciences 2018, 113, 106–114. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Ran, C.; Gao, W.; Li, M.; Xia, Y.; Huang, W. Metal Halide Perovskite for next-generation optoelectronics: progresses and prospects. eLight (Springer) 2023, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeva, M.; Gets, D.; Polushkin, A.; Vorobyov, A.; Goltaev, A.; Neplokh, V.; Mozharov, A.; Krasnikov, D.V.; Nasibulin, A.G.; Mukhin, I.; Makarov, S. ITO-free silicon-integrated perovskite electrochemical cell for light-emission and light-detection. Opto-Electron Adv 2023, 6, 220154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Thankappan, A. eds. Perovskite photovoltaics: Basic to advanced concepts and implementation. Academic Press, 2018., 197-229.

- Orrea-Baena, J.-P.; Saliba, M.; Buonassisi, T.; Grätzel, M.; Abate, A.; Tress, W.; Hagfeldt, A. Promises and challenges of perovskite solar cells. Science 2017, 358, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Xing, J.; Quan, L.N.; García de Arquer, F.P.; Gong, X.; Lu, J.; Xie, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, D.; Yan, C.; et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 20 per cent. Nature 2018, 562, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkerman, Q.A.; Manna, L. What defines a halide perovskite? ACS Energy Letters 2020, 5, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefler, S.F.; Trimmel, G.; Rath, T. Progress on lead-free metal halide perovskites for photovoltaic applications: a review. Monatshefte für Chemie-Chemical Monthly 2017, 148, 795–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Xue, Y.Z.B.; Li, L.; Tang, B.; Hu, H. Recent Progress in 2D/3D Multidimensional Metal Halide Perovskites Solar Cells. Frontiers in Materials 2020, 7, 601179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Gong, X. Low-dimensional perovskite materials and their optoelectronics. InfoMat 2021, 3, 1039–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A. Silicon solar cells: evolution, high-efficiency design and efficiency enhancements. Semiconductor science and technology 1993, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J.-H.; Lee, C.-R.; Lee, J.-W.; Park, S.-W.; Park, N.-G. 6.5% efficient perovskite quantum-dot-sensitized solar cell. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 4088–4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-S.; Lee, C.-R.; Im, J.-H.; Lee, K.-B.; Moehl, T.; Marchioro, A.; Moon, S.-J.; Humphry-Baker, R.; Yum, J.-H.; Moser, J.E.; et al. Lead iodide perovskite sensitized all-solid-state submicron thin film mesoscopic solar cell with efficiency exceeding 9%. Scientific reports 2012, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, J.-H.; Im, S.-H.; Noh, J.-H.; Mandal, T.N.; Lim, C.-S.; Chang, J.-A.; Lee, Y.-H.; Kim, H.-S.; Sarkar, A.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Grätzel, M.; et al. Efficient inorganic–organic hybrid heterojunction solar cells containing perovskite compound and polymeric hole conductors. Nature photonics 2013, 7, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.-H.; Im, S.-H.; Heo, J.-H.; Mandal, T.N.; Seok, S.-I. Chemical management for colorful, efficient, and stable inorganic–organic hybrid nanostructured solar cells. Nano letters 2013, 13, 1764–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Saliba, M.; Moore, D.T.; Pathak, S.K.; Hörantner, M.T.; Stergiopoulos, T.; Stranks, S.D.; Eperon, G.E.; Alexander-Webber, J.A.; Abate, A.; Sadhanala, A.; Yao, S.; Chen, Y.; Friend, R.H.; Estroff, L.A.; Wiesner, U.; Snaith, H.J. Ultrasmooth organic–inorganic perovskite thin-film formation and crystallization for efficient planar heterojunction solar cells. Nature communications 2015, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.H.; Park, C.-H.; Matsuishi, K. First-principles study of the Structural and the electronic properties of the Lead-Halide-based inorganic-organic perovskites (CH~ 3NH~ 3) PbX~ 3 and CsPbX~ 3 (X= Cl, Br, I). Journal-Korean Physical Society 2004, 44, 889–893. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, J.M.; Butler, K.T.; Brivio, F.; Hendon, C.H.; van Schilfgaarde, M.; Walsh, A. Atomistic origins of high-performance in hybrid halide perovskite solar cells. Nano letters 2014, 14, 2584–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brivio, F.; Walker, A.B.; Walsh, A. Structural and electronic properties of hybrid perovskites for high-efficiency thin-film photovoltaics from first-principles. Apl Materials 2013, 1, 042111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umari, P.; Mosconi, E.; De Angelis, F. Relativistic GW calculations on CH3NH3PbI3 and CH3NH3SnI3 perovskites for solar cell applications. Scientific reports 2014, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, N.-J.; Noh, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-C.; Yang, W.-S.; Ryu, S.-C.; Seok, S.-I. Solvent engineering for high-performance inorganic–organic hybrid perovskite solar cells. Nature materials 2014, 13, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Chen, Q.; Li, G.; Luo, S.; Song, T.-B.; Duan, H.-S.; Hong, Z.; Jingbi You, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. Interface engineering of highly efficient perovskite solar cells. Science 2014, 345, 542–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.-S.; Yeom, E.-J.; Yang, W.-S.; Hur, S.; Kim, M.-G.; Im, J.; Seo, J.-W.; Noh, J.-H.; Seok, S.-I. Colloidally prepared La-doped BaSnO3 electrodes for efficient, photostable perovskite solar cells. Science 2017, 356, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.-J.; Yang, J.-H.; Kang, J.-G.; Yan, Y.; Wei, S.-H. Halide perovskite materials for solar cells: a theoretical review. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2015, A3, 8926–8942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnkar, A.; Marshall, A.R.; Sanehira, E.M.; Chernomordik, B.D.; Moore, D.T.; Christians, J.A.; Chakrabarti, T.; Luther, J.M. Quantum dot–induced phase stabilization of α-CsPbI3 perovskite for high-efficiency photovoltaics. Science 2016, 354, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Ye, Q.; Chu, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; Zhigang Yin, Z.; You, J. Solvent-controlled growth of inorganic perovskite films in dry environment for efficient and stable solar cells. Nature communications 2018, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Kan, M.; Zhao, Y. Bifunctional stabilization of all-inorganic α-CsPbI3 perovskite for 17% efficiency photovoltaics. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2018, 140, 12345–12348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Ma, Y.; Fan, J.; Mai, Y. All-inorganic CsPbI2Br perovskite solar cells with high efficiency exceeding 13%. Journal of the American chemical society 2018, 140, 3825–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, W.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Y.; Gao, X.; Xue, Q.; Yip, H.-L.; Fan, J.; et al. Structurally Reconstructed CsPbI2Br Perovskite for Highly Stable and Square-Centimeter All-Inorganic Perovskite Solar Cells. Advanced Energy Materials 2019, 9, 1803572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Xue, Q.; Li, X.; Chueh, C.-C.; Yip, H.-L.; Zhu, Z.; Jen, A.K.Y. Highly efficient all-inorganic perovskite solar cells with suppressed non-radiative recombination by a Lewis base. Nature communications 2020, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoumpos, C.C.; Malliakas, C.D.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Semiconducting tin and lead iodide perovskites with organic cations: phase transitions, high mobilities, and near-infrared photoluminescent properties. Inorganic chemistry 2013, 52, 9019–9038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, G.; Mathews, N.; Lim, S.S.; Yantara, N.; Liu, X.; Sabba, D.; Grätzel, M.; Mhaisalkar, S.; Sum, T.C. Low-temperature solution-processed wavelength-tunable perovskites for lasing. Nature materials 2014, 13, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyata, A.; Mitioglu, A.; Plochocka, P.; Portugall, O.; Wang, J.T.-W.; Stranks, S.D.; Snaith, H.J.; Nicholas, R.J. Direct measurement of the exciton binding energy and effective masses for charge carriers in organic–inorganic tri-halide perovskites. Nature Physics 2015, 11, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda-Yamamuro, N.; Matsuo, T.; Suga, H. Dielectric study of CH3NH3PbX3 (X= Cl, Br, I). Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 1992, 53, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanehira, E.M.; Marshall, A.R.; Christians, J.A.; Harvey, S.P.; Ciesielski, P.N.; Wheeler, L.M.; Schulz, P.; Lin, L.Y.; Beard, M.C.; Luther, J.M. Enhanced mobility CsPbI3 quantum dot arrays for record-efficiency, high-voltage photovoltaic cells. Science advances 2017, 3, eaao4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christians, J.A.; Fung, R.C.M.; Kamat, P.V. An inorganic hole conductor for organo-lead halide perovskite solar cells. Improved hole conductivity with copper iodide. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2014, 136, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbiah, A.S.; Halder, A.; Ghosh, S.; Mahuli, N.; Hodes, G.; Sarkar, S.K. Inorganic hole conducting layers for perovskite-based solar cells. The journal of physical chemistry letters 2014, 5, 1748–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Tanaka, S.; Ito, S.; Tetreault, N.; Manabe, K.; Nishino, H.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Grätzel, M. Inorganic hole conductor-based lead halide perovskite solar cells with 12.4% conversion efficiency. Nature communications 2014, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Chen, P.; Que, M.; Xing, Y.; Que, W.; Niu, C.; Shao, J. Highly efficient flexible perovskite solar cells using solution-derived NiOx hole contacts. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3630–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Lee, J.-W.; Yantara, N.; Boix, P.P.; Kulkarni, S.A.; Mhaisalkar, S.; Gratzel, M.; Park, N.G. High efficiency solid-state sensitized solar cell-based on submicrometer rutile TiO2 nanorod and CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite sensitizer. Nano letters 2013, 13, 2412–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etgar, L.; Gao, P.; Xue, Z.; Peng, Q.; Chandiran, A.K.; Liu, B.; Md, K. Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Grätzel, M. Mesoscopic CH3NH3PbI3/TiO2 heterojunction solar cells. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2012, 134, 17396–17399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.; Jeong, S.-H.; Park, M.-H.; Kim, Y.-H.; Wolf, C.; Lee, C.-L.; Heo, J.-H.; Sadhanala, A.; Myoung, N.; Yoo, S.-H.; et al. Overcoming the electroluminescence efficiency limitations of perovskite light-emitting diodes. Science 2015, 350, 1222–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthron, K.; Lauret, J.S.; Doyennette, L.; Lanty, G.; Al Choueiry, A.; Zhang, S.J.; Brehier, A.; Largeau, L.; Mauguin, O.; Bloch, J.; et al. Optical spectroscopy of two-dimensional layered (C6H5C2H4-NH3) 2-PbI4 perovskite. Optics Express 2010, 18, 5912–5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhou, H.; Hong, Z.; Luo, S.; Duan, H.-S.; Wang, H.-H.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Yang, Y. Planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells via vapor-assisted solution process. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2014, 136, 622–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baikie, T.; Fang, Y.; Kadro, J.M.; Schreyer, M.; Wei, F.; Mhaisalkar, S.G.; Graetzel, M.; White, T.J. Synthesis and crystal chemistry of the hybrid perovskite (CH 3 NH 3) PbI 3 for solid-state sensitised solar cell applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2013, 1, 5628–5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum, T.C.; Mathews, N. Advancements in perovskite solar cells: photophysics behind the photovoltaics. Energy & Environmental Science 2014, 7, 2518–2534. [Google Scholar]

- Ponseca Jr, C.S.; Savenije, T.J.; Abdellah, M.; Zheng, K.; Yartsev, A.; Pascher, T.; Harlang, T.; Chabera, P.; Pullerits, T.; Stepanov, A.; et al. Organometal halide perovskite solar cell materials rationalized: ultrafast charge generation, high and microsecond-long balanced mobilities, and slow recombination. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2014, 136, 5189–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosconi, E.; Amat, A.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Grätzel, M.; De Angelis, F. First-principles modeling of mixed halide organometal perovskites for photovoltaic applications. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2013, 117, 13902–13913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutselas, I.B.; Ducasse, L.; Papavassiliou, G.C. Electronic properties of three-and low-dimensional semiconducting materials with Pb halide and Sn halide units. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 1996, 8, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Yu, H.; Lyu, M.; Wang, Q.; Yun, J.-H.; Wang, L. Composition-dependent photoluminescence intensity and prolonged recombination lifetime of perovskite CH 3 NH 3 PbBr 3− x Cl x films. Chemical Communications 2014, 50, 11727–11730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, B.; Xing, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, W.-H.; Qiu, J. High performance hybrid solar cells sensitized by organolead halide perovskites. Energy & Environmental Science 2013, 6, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yin, C.; Yang, F.; Yao, Y.; Yuan, F.; Chen, H.; Wang, R.; Bai, S.; Tu, G.; Hou, L. Highly Luminescent and Stable CsPbI3 Perovskite Nanocrystals with Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Ligand Passivation for Red-Light-Emitting Diodes. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2021, 12, 2437–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.J.; Wieghold, S.; Sponseller, M.C.; Chua, M.R.; Bertram, S.N.; Hartono, N.T.P.; Tresback, J.S.; Hansen, E.C.; Correa-Baena, J.-P.; Bulović, V.; et al. An interface stabilized perovskite solar cell with high stabilized efficiency and low voltage loss. Energy & Environmental Science 2019, 12, 2192–2199. [Google Scholar]

- Report of Best Research Cell efficiencies. Available online: www.nrel.gov/pv/assets/pdf/best-research-cell-efficiencies.2019106.pdf.

- Lee, B.-H.; Stoumpos, C.C.; Zhou, N.; Hao, F.; Malliakas, C.; Yeh, C.Y.; Marks, T.J.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; Chang, R.PH. Air-stable molecular semiconducting iodosalts for solar cell applications: Cs2SnI6 as a hole conductor. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2014, 136, 15379–15385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maughan, A.E.; Ganose, A.M.; Bordelon, M.M.; Miller, E.M.; Scanlon, D.O.; Neilson, J.R. Defect tolerance to intolerance in the vacancy-ordered double perovskite semiconductors Cs2SnI6 and Cs2TeI6. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2016, 138, 8453–8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltzoglou, A.; Antoniadou, M.; Kontos, A.G.; Stoumpos, C.C.; Perganti, D.; Siranidi, E.; Raptis, V.; Trohidou, K.; Psycharis, V.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; et al. Optical-vibrational properties of the Cs2SnX6 (X= Cl, Br, I) defect perovskites and hole-transport efficiency in dye-sensitized solar cells. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2016, 120, 11777–11785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadro, J.M.; Pellet, N.; Giordano, F.; Ulianov, A.; Müntener, O.; Maier, J.; Grätzel, M.; Hagfeldt, A. Proof-of-concept for facile perovskite solar cell recycling. Energy & Environmental Science 2016, 9, 3172–3179. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.-M.; Mohanta, N.; Wang, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-P.; Yang, Y.-W.; Wang, C.-L.; Hung, C.-H.; Diau, E.W.-G. Formation of Stable Tin Perovskites Co-crystallized with Three Halides for Carbon-Based Mesoscopic Lead-Free Perovskite Solar Cells. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2017, 56, 13819–13823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabba, D.; Mulmudi, H.K.; Prabhakar, R.R.; Krishnamoorthy, T.; Baikie, T.; Boix, P.P.; Mhaisalkar, S.; Mathews, N. Impact of anionic Br–substitution on open circuit voltage in lead free perovskite (CsSnI3-xBr x) solar cells. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2015, 119, 1763–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Peng, S.; Wu, Y.; Fang, X.; Chen, X.; Jia, X.; Zhang, K.; Yuan, N.; Ding, J.; Dai, N. Air-stable layered bismuth-based perovskite-like materials: Structures and semiconductor properties. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2017, 526, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.M.; Phuyal, D.; Davies, M.L.; Li, M.; Philippe, B.; De Castro, C.; Qiu, Z.; Kim, J.-H.; Watson, T.; Tsoi, W.C.; et al. An effective approach of vapour assisted morphological tailoring for reducing metal defect sites in lead-free, (CH3NH3) 3Bi2I9 bismuth-based perovskite solar cells for improved performance and long-term stability. Nano Energy 2018, 49, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Xia, X.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Lei, B.; Gao, Y. High-quality (CH3NH3) 3Bi2I9 film-based solar cells: pushing efficiency up to 1.64%. The journal of physical chemistry letters 2017, 8, 4300–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, C.; Liang, G.; Zhao, S.; Lan, H.; Peng, H.; Zhang, D.; Sun, H.; Luo, J.; Fan, P. Lead-free formamidinium bismuth perovskites (FA) 3Bi2I9 with low bandgap for potential photovoltaic application. Solar Energy 2019, 177, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoumpos, C.C.; Frazer, L. Hybrid germanium Iodide perovskite semiconductors: Active lone pairs, structural distortion, Direct and Indirect energy gaps, and strong nonlinear optical properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. (ACS) 2015, 137, 6804–6819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, T.; Ding, H.; Yan, C.; Leong, W.L.; Baikie, T.; Zhang, Z.; Sherburne, M.; Li, S.; Asta, M.; Mathews, N.; et al. Lead-free germanium iodide perovskite materials for photovoltaic applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2015, 3, 23829–23832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Pal, A.J. Tin (IV) substitution in (CH3NH3) 3Sb2I9: toward low-band-gap defect-ordered hybrid perovskite solar cells. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2018, 10, 35194–35205. [Google Scholar]

- Kopacic, I.; Friesenbichler, B.; Hoefler, S.F.; Kunert, B.; Plank, H.; Rath, T.; Trimmel, G. Enhanced performance of germanium halide perovskite solar cells through compositional engineering. ACS Applied Energy Materials 2018, 1, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavney, A.H.; Leppert, L.; Bartesaghi, D.; Gold-Parker, A.; Toney, M.F.; Savenije, T.J.; Neaton, J.B.; Karunadasa, H.I. Defect-induced band-edge reconstruction of a bismuth-halide double perovskite for visible-light absorption. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2017, 139, 5015–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, E.T.; Ball, M.R.; Windl, W.; Woodward, P.M. Cs2AgBiX6 (X= Br, Cl): new visible light absorbing, lead-free halide perovskite semiconductors. Chemistry of Materials 2016, 28, 1348–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Deng, Z.; Sun, S.; Xie, F.; Kieslich, G.; Evans, D.M.; Carpenter, M.A.; Bristowe, P.W.; Cheetham, A.K. The synthesis, structure and electronic properties of a lead-free hybrid inorganic–organic double perovskite (MA) 2 KBiCl 6 (MA= methylammonium). Materials Horizons 2016, 3, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.-G.; Yang, J.-H.; Fu, Y.; Yang, D.; Xu, Q.; Yu, L.; Wei, S.-H.; Zhang, L. Design of lead-free inorganic halide perovskites for solar cells via cation-transmutation. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2017, 139, 2630–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, D.; Hutter, O.S.; Longo, G. Chalcogenide perovskites for photovoltaics: current status and prospects. Journal of Physics: Energy 2021, 3, 034010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishigaki, Y.; Nagai, T.; Nishiwaki, M.; Aizawa, T.; Kozawa, M.; Hanzawa, K.; Kato, Y.; Sai, H.; Hiramatsu, H.; Hosono, H.; et al. Extraordinary strong band-edge absorption in distorted chalcogenide perovskites. Solar RRL 2020, 4, 1900555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xuan, Z.; Chen, T.; Zhang, J.; Hao, X.; Wu, L.; Constantinou, I.; Zhao, D. Progress in perovskite solar cells towards commercialization—a review. Materials 2021, 14, 6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Jang, D.; Dong, L.; Qiu, S.; Distler, A.; Li, N.; Brabec, C.J.; Egelhaaf, H.-J. Upscaling Solution-Processed Perovskite Photovoltaics. Advanced Energy Materials 2021, 11, 2101973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaith, H.J. ; Present status and future prospects of perovskite photovoltaics. Nature materials 2018, 17, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Li, B.; Li, S.; Yin, L. Future Challenges of the Perovskite Materials. In: Arul, N.; Nithya, V. (Eds) Revolution of Perovskite. Materials Horizons: From Nature to Nanomaterials. Springer, Singapore. 2020, pp 315–320.

- Milić, J.V.; Zakeeruddin, S.M.; Grätzel, M. Layered Hybrid Formamidinium Lead Iodide Perovskites: Challenges and Opportunities. Accounts of Chemical Research 2021, 54, 2729–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Liu, S.F.; Tress, W. A review on the stability of inorganic metal halide perovskites: challenges and opportunities for stable solar cells. Energy & Environmental Science 2021, 14, 2090–2113. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Peng, Y.; Jen, A.K.-Y.; Yip, H.-L. Development and challenges of metal halide perovskite solar modules. Solar RRL 2022, 6, 2100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Akin, S.; Hinderhofer, A.; Eickemeyer, F.T.; Zh, H.; Seo, J.-Y.; Zhang, J.; Schreiber, F.; Zhang, H.; Zakeeruddin, S.M.; et al. Stabilization of highly efficient and stable phase-pure FAPbI3 perovskite solar cells by molecularly tailored 2D-overlayers. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2020, 59, 15688–15694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Mende, L.; Dyakonov, V.; Olthof, S.; Ünlü, F.; Lê, K.M.T.; Mathur, S.; Karabanov, A.D.; et al. Roadmap on organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite semiconductors and devices. APL Materials 2021, 9, 109202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liao, L.; Chen, L.; Xu, C.; Yao, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, P.; Deng, J.; Song, Q. Perovskite solar cells fabricated under ambient air at room temperature without any post-treatment. Organic Electronics 2020, 86, 105918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Van Brackle, C.H.; Dai, X.; Zhao, J.; Chen, B.; Huang, J. Tailoring solvent coordination for high-speed, room-temperature blading of perovskite photovoltaic films. Science advances 2019, 5, eaax7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huckaba, A.J.; Lee, Y.; Xia, R.; Paek, S.; Bassetto, V.C.; Oveisi, E.; Lesch, A.; Kinge, S.; Dyson, P.J.; Girault, H.; et al. Inkjet-Printed Mesoporous TiO2 and Perovskite Layers for High Efficiency Perovskite Solar Cells. Energy Technology 2019, 7, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, X.; Pi, Y.; Du, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, K.; Wu, K.; Zhuang, C.; Han, X. A polymer controlled nucleation route towards the generalized growth of organic-inorganic perovskite single crystals. Nature communications 2021, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhe, T.A.; Su, W.-N.; Chen, C.-H.; Pan, C.-J.; Cheng, J.-H.; Chen, H.-M.; Tsai, M.-C.; Chen, L.-Y.; Dubale, A.R.; Hwang, B.-J. Organometal halide perovskite solar cells: degradation and stability. Energy & Environmental Science 2016, 9, 323–356. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, G.; Guo, X.; Wang, L. Review of recent progress in chemical stability of perovskite solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2015, 3, 8970–8980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lin, Q.; Chmiel, F.P.; Sakai, N.; Herz, L.M.; Snaith, H.J. Efficient ambient-air-stable solar cells with 2D–3D heterostructured butylammonium-caesium-formamidinium lead halide perovskites. Nature Energy 2017, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijtens, T.; Eperon, G.E.; Pathak, S.; Abate, A.; Lee, M.M.; Snaith, H.J. Overcoming ultraviolet light instability of sensitized TiO 2 with meso-superstructured organometal tri-halide perovskite solar cells. Nature communications 2013, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domanski, K.; Correa-Baena, J.-P.; Mine, N.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Abate, A.; Saliba, M.; Tress, W.; Hagfeldt, A.; Grätzel, M. Not all that glitters is gold: metal-migration-induced degradation in perovskite solar cells. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 6306–6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Williams, S.T.; Xiong, D.; Zhang, W.; Chueh, C.-C.; Chen, W.; Jen, A.K.-Y. SrCl2 Derived Perovskite Facilitating a High Efficiency of 16% in Hole-Conductor-Free Fully Printable Mesoscopic Perovskite Solar Cells. Advanced Materials 2017, 29, 1606608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Shao, Z.; Li, C.; Pang, S.; Yan, Y.; Cui, G. Structural Properties and Stability of Inorganic CsPbI3 Perovskites. Small Structures 2021, 2, 2000089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tschumi, M.; Han, H.; Babkair, S.S.; Alzubaydi, R.A.; Ansari, A.A.; Habib, S.S.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Zakeeruddin, S.M.; Grätzel, M. Outdoor performance and stability under elevated temperatures and long-term light soaking of triple-layer mesoporous perovskite photovoltaics. Energy Technology 2015, 3, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X.; Gao, F.; Cao, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, Q.; Liu, H.; Li, S. Progress on the stability and encapsulation techniques of perovskite solar cells. Organic Electronics 2022, 106, 106515. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, J.; Bazaka, K.; Anderson, L.J.; White, R.D.; Jacob, M.V. Materials and methods for encapsulation of OPV: A review. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2013, 27, 104–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Ahmad, I.; Leung, T.; Lin, J.; Chen, W.; Liu, F.; Ching Ng, A.M.; Zhang, Y.; Djurišić, A.B. Encapsulation and Stability Testing of Perovskite Solar Cells for Real Life Applications. ACS Materials 2022, 2, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cao, H.; Yu, H.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, H.; Yang, L.; Yin, S. Large-area, high-quality organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite thin films via a controlled vapor–solid reaction. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2016, 4, 9124–9132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteocci, F.; Cinà, L.; Lamanna, E.; Cacovich, S.; Divitini, G.; Midgley, P.A.; Ducati, C.; Di Carlo, A. Encapsulation for long-term stability enhancement of perovskite solar cells. Nano Energy 2016, 30, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Hou, X.; Hu, Y.; Mei, A.; Liu, L.; Wang, P.; Han, H. Synergy of ammonium chloride and moisture on perovskite crystallization for efficient printable mesoscopic solar cells. Nature communications 2017, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Shi, Y.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xing, Y.; Wang, K.; Du, Y.; Ma, T. Hole-conductor-free, metal-electrode-free TiO2/CH3NH3PbI3 heterojunction solar cells based on a low-temperature carbon electrode. The Journal of Physical Chemistry letters 2014, 5, 3241–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, Y.-S.; Lim, J.; Yun, H.-J.; Kim, Y.-H.; Park, T. A diketopyrrolopyrrole-containing hole transporting conjugated polymer for use in efficient stable organic–inorganic hybrid solar cells based on a perovskite. Energy & Environmental Science 2014, 7, 1454–1460. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.-Y.; Lee, K.-T.; Huang, W.-K.; Siao, H.-Y.; Chang, Y.-C. High-performance, air-stable, low-temperature processed semitransparent perovskite solar cells enabled by atomic layer deposition. Chemistry of Materials 2015, 27, 5122–5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, S.G.; Tiihonen, A.; Martineau, D.; Ozkan, M.; Vivo, P.; Kaunisto, K.; Ulla, V.; Zakeeruddin, S.M.; Grätzel, M. Long term stability of air processed inkjet infiltrated carbon-based printed perovskite solar cells under intense ultra-violet light soaking. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2017, 5, 4797–4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eperon, G.E.; Stranks, S.D.; Menelaou, C.; Johnston, M.B.; Herz, L.M.; Snaith, H.J. Formamidinium lead trihalide: a broadly tunable perovskite for efficient planar heterojunction solar cells. Energy & Environmental Science 2014, 7, 982–988. [Google Scholar]

- Filip, M.R.; Eperon, G.E.; Snaith, H.J.; Giustino, F. Steric engineering of metal-halide perovskites with tunable optical band gaps. Nature Communications 2014, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, M.; Qian, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhao, Y. Potential lead toxicity and leakage issues on lead halide perovskite photovoltaics. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 426, 127848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, G.; Gupta, D.; Tiwari, A. Toxicity of lead: a review with recent updates. Interdisciplinary toxicology 2012, 5, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Ho-Baillie, A.; Snaith, H.J. The emergence of perovskite solar cells. Nature Photonics 2014, 8, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Cheng, S.-N.; Cheng, L.; Wang, Z.-K.; Liao, L.-S. Toxicity, Leakage, and Recycling of Lead in Perovskite Photovoltaics. Advanced Energy Materials 2023, 13, 2204144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Luo, W.; Guo, X.; Huang, Z.; Ting, H.; Sun, W.; Zhong, X.; Wei, S.; et al. The dawn of lead-free perovskite solar cell: highly stable double perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 film. Advanced Science 2018, 5, 1700759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartono, N.T.P.; Thapa, J.; Tiihonen, A.; Oviedo, F.; Batali, C.; Yoo, J.J.; Liu, Z.; Li, R.; Marrón, D.F.; Bawendi, M.G.; et al. How machine learning can help select capping layers to suppress perovskite degradation. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, L.M. How lattice dynamics moderate the electronic properties of metal-halide perovskites. The journal of physical chemistry letters 2018, 9, 6853–6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, E.; Tang, X.; Langner, S.; Duchstein, P.; Zhao, Y.; Levchuk, I.; Kalancha, V.; Stubhan, T.; Hauch, J.; Egelhaaf, H.J.; et al. Robot-based high-throughput screening of antisolvents for lead halide perovskites. Joule 2020, 4, 1806–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, F.P.; Jin, S.; Paggiola, G.; Petchey, T.HM.; Clark, J.H.; Farmer, T.J.; Hunt, A.J.; McElroy, C.R.; Sherwood, J. Tools and techniques for solvent selection: green solvent selection guides. Sustainable Chemical Processes 2016, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zheng, X.; Deng, Y.; Li, T.; Shao, Y.; Gruverman, A.; Shield, J.; Huang, J. Is Cu a stable electrode material in hybrid perovskite solar cells for a 30-year lifetime? Energy & Environmental Science 2016, 9, 3650–3656. [Google Scholar]

- Binek, A.; Petrus, M.L.; Huber, N.; Bristow, H.; Hu, Y.; Bein, T.; Docampo, P. Recycling perovskite solar cells to avoid lead waste. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2016, 8, 12881–12886. [Google Scholar]

- Kadro, J.M.; Pellet, N.; Giordano, F.; Ulianov, A.; Müntener, O.; Maier, J.; Grätzel, M.; Hagfeldt, A. Proof-of-concept for facile perovskite solar cell recycling. Energy & Environmental Science 2016, 9, 3172–3179. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, M. The Economics of Solar Perovskite Manufacturing, PV magazine 2022 Sept-22. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2022/09/02/the-economics-of-perovskite-solar-manufacturing/.

- Čulík, P.; Brooks, K.; Momblona, C.; Adams, M.; Kinge, S.; Maréchal, F.; Dyson, P.J.; Nazeeruddin, M.K. Design and Cost Analysis of 100 MW Perovskite Solar Panel Manufacturing Process in Different Locations. ACS Energy Letters 2022, 7, 3039–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S. No. | Inorganic Perovskite | Method | Solar Cell Device Structure | Efficiency (%) |

Ref. |

| 1 | CsPbI3 and its derivative perovskite solar cells (PSC) | Solvent controlled growth | Stable α-phase CsPbI3. Device structure: (ITO)/SnO2/CsPbI3/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au |

15.77 | [41] |

| 2 | CsPbI3 | PCE-based PSC via surface termination of the perovskite film using phenyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (PTMBr) | Highly stable phase due to the use of PTMBr treated with CsPbI3. Device layers: FTO/c: TiO2/perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD/Ag | 17.06 | [42] |

| 3 | CsPbI3 | Formamidium (FA) iodide (FAI)-coated quantum dots | Tio2/FAI-coated CsPbI3/Spiro-O MeTAD/ MoOx/Al | 10.7 | [40] |

| 4. | CsPbI2Br | Fabrication of ZnO/C60 bilayer electron transport layer in inverted PSC PCE | FTO/NIOx/ CsPbI2Br/ZnO @C60 | 13.3 | [43] |

| 5 | CsPbI2Br | Introduction of InCl3 to enhance the efficiency of inverted PSC | Yellow stable (δ-phase). Device structure: FTO/NiOx/perovskite/ZnO@C60/Ag using InCl3:CsPbI2Br perovskite |

13.74 | [44] |

| 6. | CsPbIxBr3-x | Lewis base, 6TIC-4F certified, and the most efficient inverted inorganic PSC with improved photostability reported till date. | Inverted layer with structure FTO/NIOx/ CsPbIxBr3-x /ZnO/ C60/Ag | 16.1 certified 15.6 | [45] |

| SN | Hybrid Perovskite | HTM | Device Structure | Efficiency (%) | Ref. |

| 1. | CH3NH3PbI3 | I-/I-3 | CH3NH3PbI3 Quantum dots (QD)/TiO2 substrate | 6.5 | [27] |

| 2. | CH3NH3PbI3 | CuI | TiO2/ CH3NH3PbI3/ spiroOMeTAD | 6.0 | [51] |

| 3. | CH3NH3PbI3-xClx | NiO | FTO/NiO/CuSCN/ CH3NH3PbI3-xClx/ PCBM/Ag | 7.3 | [52] |

| 4. | CH3NH3PbI3 | CuSCN | TiO2/ CH3NH3PbI3/ CuSCN/Au | 12.4 | [53] |

| 5. | CH3NH3PbI3-xBrx | PTAA | TiO2/ CH3NH3PbI3-xBrx/DMSO/PTAA/Au | 16.2 | [36] |

| 6. | CH3NH3PbI3 | NiOx | ITO/NiOx/ CH3NH3PbI3/PCBM/Ag | 16.47 | [54] |

| 7. | CH3NH3PbI3-xClx | spiroOMeTAD | ITO/PEIE/TiO2 CH3NH3PbI3-xClx/ spiroOMeTAD/Au | 19.32 | [37] |

| Perovskite | Characteristics | Behavior Response |

| CsPbI3 | Bandgap | Spin-orbit coupling approximation 1.16eV can be reduced to 0.39eV |

| Binding energy | 169eV | |

| Photoluminescence | λem = 680nm, λex = 365nm | |

| CH3NH3PbBr3 | Absorption | 800–550nm |

| Bandgap | 2.2eV | |

| Binding energy | 150meV | |

| Photoluminescence | Emission at shorter wavelength owing to larger bandgap λem = 560nm | |

| CH3NH3PbI3 | Absorption | 800nm to complete visible spectrum |

| The thickness of the film | 600nm | |

| Bandgap | 1.55eV comparable with the optimal band gap 1.4eV | |

| Binding energy | 50meV | |

| Photoluminescence | Emission at longer wavelength owing to small bandgap (λem = 770nm for λex = 546 nm) | |

| Ambipolar behavior | Mesoporous TiO2/ CH3NH3PbI3 | p-type charge transport. Solar efficiency of 5.5% |

| Mesoporous ZnO2/ CH3NH3PbI3 | n-type charge transport. Solar efficiency of 10.8% | |

| Dispersion range | 130nm and 100nm. 1100nm and 1200nm in CH3NH3PbI3-xClx |

| Perovskite Materials | Eg (eV) | Voc (V) | Jsc (mA-cm2) | FF | PCE (%) | Ref. |

| MASnI3 | 1.3 | 0.68 | 16.3 | 0.48 | 5.23 | [73] |

| MASnI3-xBrx | 1.75 | 0.82 | 12.3 | 0.57 | 5.73 | [73] |

| MASnIBr0.8Cl0.2 | 1.25 | 0.38 | 14 | 0.57 | 3 | [74] |

| CsSnI2.9Br0.1 | 0.22 | 24.16 | 0.33 | 1.76 | [75] |

| Perovskite Materials | Eg (eV) | Voc (V) | Jsc (A-cm2) | FF | PCE (%) | Ref. |

| Cs3Bi2I9 | 2.2 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.5 | 1.09 | [76] |

| MA3Bi2I9 | 2.1 | 0.83 | 3.0 | 0.79 | 3.17 | [77] |

| MA3Bi2I9 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 3.0 | 0.79 | 1.64 | [78] |

| FA3Bi2I9 | 2.19 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 0.46 | 0.022 | [79] |

| MA3Bi2I9-xClx | 2.4 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.38 | 0.003 | [77] |

| Perovskite Materials | Eg (eV) | Voc (V) | Jsc (A-cm2) | FF | PCE (%) | Ref. |

| CsGeI3 | 1.63 | 0.074 | 5.7 | 0.27 | 1.1 | [81] |

| MAGeI3 | 2.2 | 0.15 | 4.0 | 0.3 | 2.0 | [82] |

| MAGeI2.7Br0.3 | 0.46 | 3.11 | 0.48 | 5.7 | [83] |

| Materials | Merits | Demerits and Challenges |

| Tin (Sn) based perovskites | The optical bandgap is in the near infrared region, has a comparable ionic radius (1.35 Å) to Pb2+ (1.49 Å), and exhibits stability against moisture. Sn-based materials possess stability for 3800 hours. Among all lead-free materials, this material has presently achieved the highest efficiency. | Sn2+ may be as hazardous as Pb2+ and, therefore, may also face the same challenges that Pb-based perovskites are facing today. |

| Bismuth (Bi) based perovskites | Bi2+ has the same electronic configuration as Pb2+ (ns2). Inorganic Bi2+-based materials show promising stability, are insoluble in water, are not toxic to the environment, are cost-effective, and have the potential to overcome most of the challenges that are faced by Pb in terms of industrialization. | has a broad bandgap, low performance, and more internal defects. Organic compound stability is relatively low. The lowest power conversion efficiency (PCE) achieved so far in comparison with other materials Needs a more promising research direction. |

| Increasing quantum yield and PCE can make this candidate an immediate replacement for Pb in the near future. | ||

| Antimony (Sb) based perovskites | Sb3+ compounds show stability in the presence of air, and the bandgap is also comparable to that of Pb (2.14 eV). They are insoluble in water, and Sb2+ possesses good charge transport properties owing to the small bandgap. | (CH3NH3)3SbI9 may face the challenges of energetic disorder and low photocurrent density. low-hopping mechanism for charge transport owing to the large bandgap. |

| Germanium (Ge) based perovskites | These are leading materials in the semiconductor industry and possess good optoelectronic properties. Moreover, they are lightweight and less toxic to the environment. They are stable in an inert atmosphere. | Decomposes easily in the air. It is not a cost-effective material. |

| Double halide perovskites | Robust stability and a direct bandgap of 0.9–1.02 eV. | Most of the research is based on the computational method. |

| Merits | Demerits |

|---|---|

| Hybrid perovskites with the general formula ABX3 (A = organic cation, B = divalent metal, and X = halogen or pseudo-halogen) are used. | External factors, such as water, heat, humidity, and sunlight, inherently degrade the stability of the active layer of perovskite solar panels. |

| Easy, low-cost manufacturing processes make perovskite the obvious choice for mass production. | Water sensitivity causes irreversible damage to perovskite materials. |

| The PCE of perovskite solar cells is high. | Heat: Lead halides show an inability to sustain thermal stress. Therefore, the perovskite structure degrades under heat and creates halogen gases that are the source of the formation of B metals (lead, tin, germanium, etc.) on the perovskite film. |

| Hybrid perovskite film solar panels are confirming candidates for power generation in the near future. | Oxygen and light: Prolonged exposure to air and light photons adversely degrades the longevity of the solar panel. |

| Conversion energy loss is less in perovskite solar cells compared with other cells. | Scalability and efficiency on large-area perovskite are comparatively small. The technology is yet to be effectively transferred from the laboratory to the industry. |

| Solar Cell Structure | Testing Conditions | ||||||

| Stability Time (hours) | Illumination Dark/Light | Temperature (0C) | Atmospheric Condition Humidity (%) | Encapsulation | Percentage of initial Performance (%) | Ref. | |

| m-TiO2/MAPbI3/Carbon | >2000 | Dark | RT | Air | No | 100 | [117] |

| m-TiO2/MAPbI3/PDPPDBTE/Au | 1000 | Dark | RT | Air (20) | No | 100 | [118] |

| ITO/NiOx/MAPbI3/ZnO/Al | 1440 | Dark | 25 | Air (30–35) | No | 90 | [119] |

| ITO/PETOD:PSS/MAPbI3/ZnO/Ag | 1000 | Dark | 30 | Air (65) | Yes | >95 | [119] |

| m-TiO2 /ZrO2/MAPbI3/Carbon | >3000 | Dark | RT | Air (35) | no | ~100 | [116] |

| m-TiO2/MAPbI3/Carbon | 1002 | Ultraviolet | 40 | Air (45) | Yes | ~100 | [120] |

| BaSnO3/MaPbI3/NiO/Au | 1000 | Light | RT | Air | Yes | 93 | [36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).