1. Introduction

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Lib. (de Bary), a widespread necrotrophic plant pathogen, is known to infect and cause disease in over 500 plant species worldwide [

1], including many important agronomic crops and weeds [

2]. Sclerotinia stem rot (SSR) disease is a major limiting factor in the production of

Brassica napus L. (canola/ rapeseed), the second most important oilseed crop in the world [

3]. Under favourable environmental conditions, outbreaks of SSR can lead to substantial economic losses in

B. napus through reduction in yield and grain quality [

4]. Yield loss in

B. napus is typically caused by

S. sclerotiorum colonization of the main stem via infected petals lodging on axils, which blocks the movement of nutrients and water to the developing seeds [

5]. Currently, SSR management in

B. napus depends heavily on effective fungicide applications at the flowering stage, with no complete SSR host resistance available [

6]. However, prophylactic fungicide applications are challenging as efficacy depends on accurate prediction of timing of fungal ascospore release and presence on the plant tissue [

4]. A rapid expansion of

B. napus production in Australia over the past few decades in combination with the long-term persistence of inoculum (sclerotia) in soil has highlighted the need for development of economically viable and effective SSR management strategies, that is underpinned by sound knowledge of the disease cycle in

B. napus.

Whilst

S. sclerotiorum has a broad host range and is considered to have little host specificity, the importance of understanding isolate diversity and subsequent pathogenicity on hosts throughout the growing period is well known as it enables effective screening strategies to be developed that identify host response and resistance [

7]. Although many studies have been conducted on the pathogenicity of

S. sclerotiorum isolates on mature Brassica [

5,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] and non-Brassica species [

14,

15] host genotypes using stem inoculation, disease impact and isolate aggressiveness was singularly determined by stem lesion measurements. Furthermore, many of these

B. napus screening studies utilized single isolates i.e. [

5,

8,

10,

11,

13], which does not reflect the diversity present in

S. sclerotiorum populations in the field with genetically distinct isolates infecting

B. napus showing differentiation in phenotypic traits such as aggressiveness [

9,

12,

16], germination and pre-conditioning requirements [

17,

18] and fungicide sensitivity [

19].

To determine the whole impact of an isolate on its

B. napus host (via expression of SSR disease), it is essential that the impact is assessed throughout the growing season examining both short- (i.e. lesion development, yield) and long-term (i.e. inoculum production) outcomes. Whilst it has been observed in the field that with heavy infections of the pathogen and under conducive conditions necrotic stem lesions can lead to lodging of

B. napus plants by girdling the stem and causing SSR-induced yield loss [

4], to our knowledge no study has examined the relationship between the degree of pathogenicity as measured by lesion length and final yield of

Brassica napus genotypes. There have been research activities examining other important disease survival traits such as inoculum production on hosts, however these either focused on measurement of sclerotia morphology only [

20,

21], or were limited in their analysis or correlation to pathogenicity as determined by lesion length [

12,

16]. For example, Taylor et al. [

12] measured both lesion length and sclerotia production in 20

B. napus lines inoculated with a single

S. sclerotiorum isolate, with more resistant lines observed to produce fewer sclerotia in the stem, however no direct correlation between the two traits were made. Ge et al. [

16] compared lesion length of

B. napus with isolate sclerotia morphological traits such as growth rate and production, but these sclerotial traits were determined in vitro under laboratory conditions. Research has shown

S. sclerotiorum isolates differ in their ability to produce inoculum, with sclerotia production highly variable in two genetically distinct

S. sclerotiorum isolates from Alaska [

20] when inoculated on excised tissue from two cabbage and three lettuce cultivars, but differences were less pronounced on carrot and celery. The strong influence of both host and isolate genotype on inoculum potential is also confirmed in the field by results from Taylor et al. [

21] who inoculated five host genotypes (bean, carrot, potato, rape, lettuce) with three genetically distinct isolates. The ability of isolates to produce more sclerotia is highly beneficial for the long-term continuation of the pathogen as sclerotia can survive for up to 8 years in soil [

2], increasing the potential for higher levels of infection in subsequent years. Furthermore, the ability of particular isolates to produce larger sclerotia may also lead to an ecological fitness advantage as they are shown to survive in the soil for longer periods [

22] and produce more apothecia (and consequently ascospores) during carpogenic germination [

23].

The aim of this study was to screen B. napus varieties to four diverse aggressive S. sclerotiorum isolates over two growing seasons. Host response was determined using a combination of disease variables measured through the disease cycle.

4. Discussion

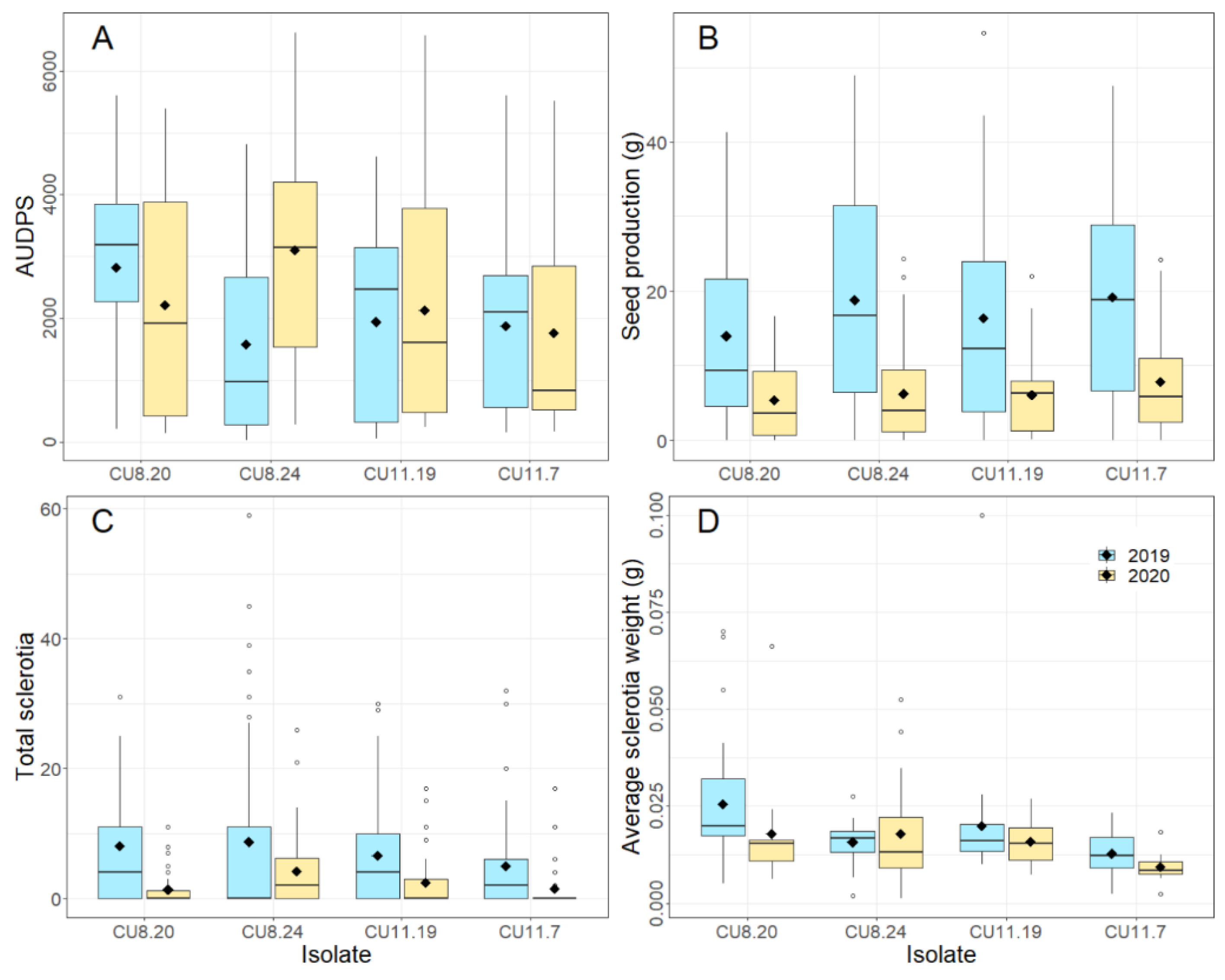

This study determined SSR susceptibility at various points through the growing season of B. napus varieties to four diverse S. sclerotiorum isolates screened over two years. We identified notable differences in varietal response, isolate aggressiveness and their corresponding interactions in relation to four disease outcomes – lesion development, sclerotia production, sclerotia weight and seed production. These responses also varied greatly depending on the environmental conditions experienced, with no consistent pattern occurring between the two study years.

The influence of environment, recorded in this study as temperature within the two experimental periods, is acknowledged as being crucial for SSR disease development and outcome, and therefore needs to be considered when undertaking variety screening studies as well as developing a disease rating system for

B. napus. We found that the four isolates responded contrarily under the different environmental conditions of two growing seasons. For example, CU8.20 produced the longest lesions across all stem inoculated varieties in 2019, whereas the longest lesions were produced by CU8.24 in 2020, with CU8.20 producing significantly smaller lesions. The same response was also observed between varieties, with those being most susceptible in 2019 (i.e highest AUDPS and sclerotia numbers with lowest seed production) not being the same as the most susceptible varieties in 2020. Crop responses to

S. sclerotiorum inoculation can be hard to replicate, even under controlled temperature environmental conditions. For example, following an experiment on lesion diameter growth on

B. napus cotyledons after inoculation with four isolates of

S. sclerotiorum, Garg et al. [

7] found significant differences in cotyledon lesion diameter between hosts, isolates and host by isolate interactions. However, when the experiment was repeated using the same environment conditions (18/14°C) and treatments, pathogenicity responses differed, resulting in a significant, but weak correlation (r=0.56, r

2 = 0.26) between the two experiments. In our study the experiment was repeated across two different seasons (effectively different environments) with no significant correlation identified between years, with seed production and sclerotia production, in particular, producing dissimilar responses in different seasons. However, the interactions between year and isolate, and year and variety were highly significant further emphasising the strong influence of environmental condition on host genotype and isolate response in relation to disease expression. It is suggested that temperature at the time of inoculation, and during disease progression (lesion and sclerotia development) has a significant effect on the aggressiveness of the different isolates, and their subsequent impact on the host. Barbetti et al. [

30] previously suggested that warmer temperatures can lead to a reduction in host resistance through increased disease severity, as well as some of the genes associated with resistance being temperature-dependent and ineffective at higher temperatures.

A study by Li et al. [

31] found time of inoculation (measured as days to 50% flowering) was strongly correlated to lesion length when measured at one and two weeks after inoculation, but no significant correlation was found at three weeks. Barbetti et al. [

8] also found no significant relationship between flowering time and lesion length at three weeks. It was proposed that delaying the measurement of lesion length until after three weeks post inoculation avoids any confounding effect of flowering time between genotypes. This is supported by results from our study, which showed only a very weak correlation between lesion length at four weeks post inoculation and flowering time.

Brassica napus varieties were also found to vary in their response to the different measured disease variables, with varieties with the highest AUDPS not typically producing the highest sclerotia numbers or the heaviest sclerotia. Only a weak correlation was identified between

B. napus seed production and AUDPS indicating that lesion length alone may not be the best measure of host resistance, as it does not provide an indication of the impact on

B. napus seed production. To the best of our knowledge, no other studies investigating the susceptibility of

B. napus varieties to

S. sclerotiorum have continued their experiment through to harvest to obtain data for the mean seed production of infected plants. Following our results, it is recommended to also include other long-term disease outcome factors such as sclerotia production and weight as well as the impact on final seed production on assessments of variety susceptibility. Although the immediate impact of SSR is evident within the season in which it occurs (i.e. stem lesion length, yield loss), the long-term impact may be realised for up to eight years post infection through the production and persistence of sclerotia as a source of inoculum in subsequent seasons [

2].

The final yield of

B. napus following

S. sclerotiorum infection varies depending on the size of the lesion and whether that lesion envelopes the whole stem, effectively impeding the translocation of nutrients and water up and down the stem, and the environmental conditions during and post infection. The influence of plant traits, such as thin versus thicker stems and maturity length, are reported to only have a weak relationship with disease susceptibility. Barbetti et al. [

8] found no significant relationship between stem width and lesion length based on screening 19

B. napus genotypes with a single

S. sclerotiorum isolate and measuring lesion length at three weeks post inoculation. No correlation between stem width and lesion length was also observed by Li et al. [

31] who inoculated 15

B. napus and 38

B. juncea genotypes with a single isolate under field conditions. This contrasts with that found in Li et al. [

32] where a strong relationship was observed between the two traits, potentially explained by the larger stem widths measured in the later study (0.37 to 1.01 cm from 42

B. napus and 12

B. juncea genotypes [

32] compared to 0.46 to 1.79 cm in the later study [

31]). Taylor et al. [

12] also found a significant correlation between the two traits, however this relationship was very weak (R = -0.26). Our study also showed a weak significant correlation (-0.41) between the two traits, based on an average stem width of 1.27 cm and lesion length at four weeks across all varieties and years. However, it is important to note that the above studies only used a single isolate, whereas we used four diverse aggressive isolates. Stem width, therefore, does not appear to be a significant factor in predicting SSR resistance but may contribute to the overall variability in measured disease traits. For this reason, stem width was used as an explanatory variable in the PCA to help in the interpretation of the observed patterns but appeared to separate the plants based on season/year which may be linked to plant growth response to seasonal conditions, rather than disease response.

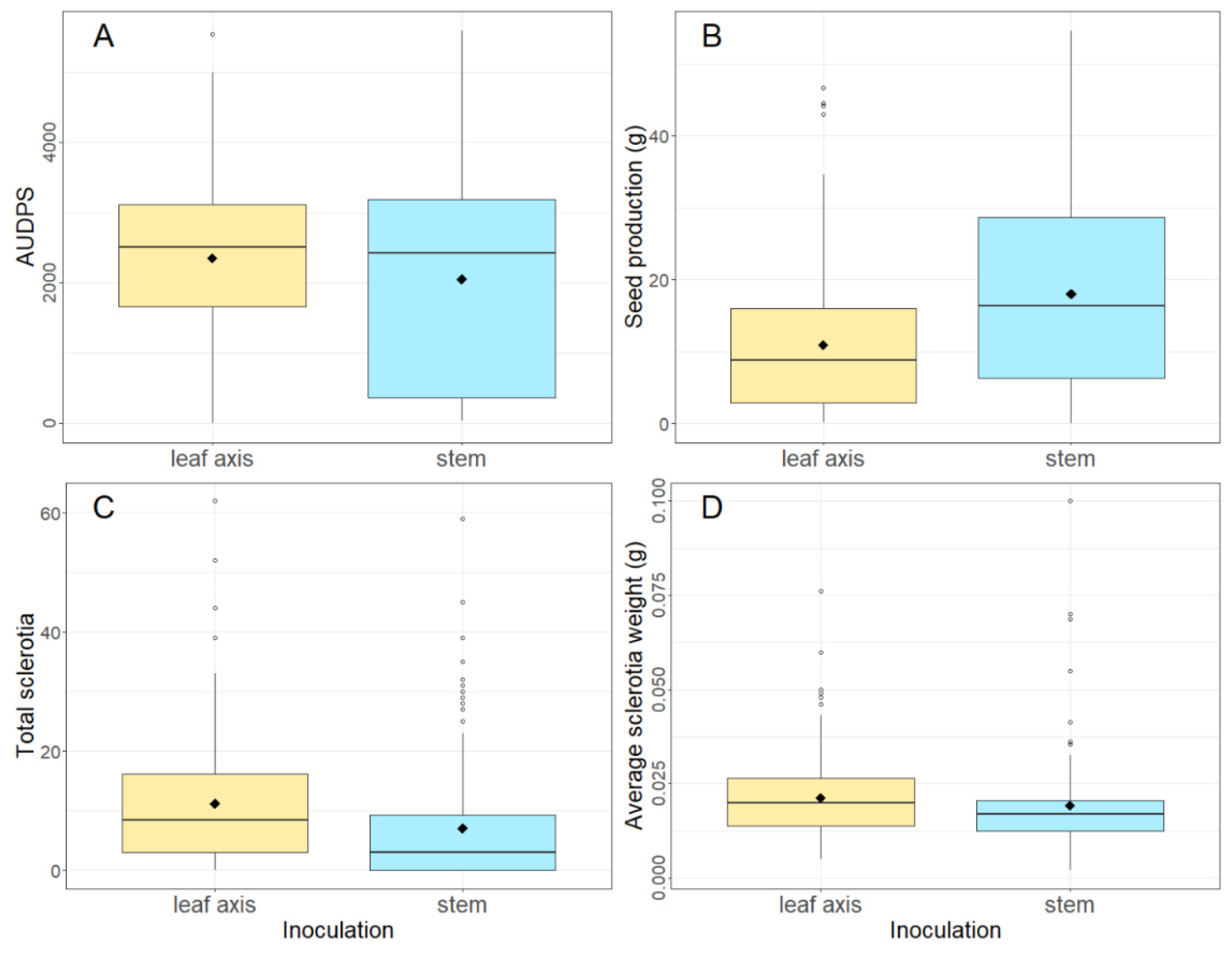

Inoculation at the leaf axis was found to be too aggressive and direct comparisons to other inoculation studies was difficult. Although inoculation at the leaf axis mimics what occurs in a commercial crop in the field, inoculation in the study was through the application of actively growing mycelium, rather than germinating ascospores on dying petals sitting in the leaf axis. There appears to be a weak point in the stem-leaf axis which resulted in a more severe impact of the pathogen, in relation to a greater number and heavier sclerotia being produced, a lower

B. napus seed production and a greater AUDPS. Stem inoculation is therefore recommended as the best method for a standardised inoculation procedure and is a commonly used inoculation method in the literature (i.e. [

5,

8,

9,

10,

11,

13,

14,

16,

32,

35].

Long term success in breeding and utilising resistant

B. napus genotypes requires a detailed understanding of the ecology and life history of both host and pathogen as well as their interactions [

33]. With abundant information on host and pathogen genotypes generated from rapidly evolving next-generation sequencing and other molecular tools in the laboratory, the challenge is to apply this knowledge to the field and develop better disease management systems [

33]. Resistance to

Sclerotinia species is through the interaction of many minor effect genes, termed quantitative disease resistance [

34], indicating the development of complete host resistance as a disease management tool is problematic. Consequently, only partial resistance has been identified in

B. napus to date [

35], and therefore it is important to understand the impact of infection from the whole disease cycle perspective, not just stem resistance.

The important points arising from this study that require further investigation are the potential importance of environmental conditions, primarily temperature, at the time of inoculation and during the infection process and their influence on the response of both different B. napus varieties and different S. sclerotiorum isolates. This has important implications for future screening of disease resistance in B. napus genotypes and in the development of a disease rating system, as the results and recommendations may vary depending on the environment in which the screening takes place, and on the varietal choices that growers are making depending on their environment. Further work is required to better understand the role of environmental conditions within the season on disease development.

To conclude, the host response of nine B. napus varieties to four aggressive S. sclerotiorum isolates was determined across four disease variables over two years. The varieties varied greatly in their response with the impact of environment having the greatest effect on disease development across all the measured variables. The lack of correlation between the disease traits highlights the complexity of disease responses to diverse isolates and host genotypes under different environments, and it is recommended that both long-term (such as inoculum production) and short-term (such as seed production) disease outcomes are combined with lesion length measurements for future studies.

Figure 1.

Boxplots showing (A) AUDPS (area under the disease progress stairs), (B) seed production (g), (C) total sclerotia number and (D) average sclerotia weight (g) of nine varieties of B. napus inoculated in 2019 at either the leaf axis or stem with four S. sclerotiorum isolates; CU8.20, CU11.7, CU11.19, CU8.24 (mean of five replicates is shown as ◆). Each boxplot visualizes the median, two hinges (25th and 75th percentile), two whiskers (largest value no further than 1.5 x interquartile range) and all outliers.

Figure 1.

Boxplots showing (A) AUDPS (area under the disease progress stairs), (B) seed production (g), (C) total sclerotia number and (D) average sclerotia weight (g) of nine varieties of B. napus inoculated in 2019 at either the leaf axis or stem with four S. sclerotiorum isolates; CU8.20, CU11.7, CU11.19, CU8.24 (mean of five replicates is shown as ◆). Each boxplot visualizes the median, two hinges (25th and 75th percentile), two whiskers (largest value no further than 1.5 x interquartile range) and all outliers.

Figure 2.

Boxplots showing AUDPS (area under the disease progress stairs), seed production (g), total sclerotia number and average sclerotia weight (g) of nine B. napus varieties stem inoculated with four S. sclerotiorum isolates; CU8.20, CU11.7, CU11.19, CU8.24, over two years (mean of five replicates is shown as ◆). Each boxplot visualizes the median, two hinges (25th and 75th percentile), two whiskers (largest value no further than 1.5 x interquartile range) and all outliers.

Figure 2.

Boxplots showing AUDPS (area under the disease progress stairs), seed production (g), total sclerotia number and average sclerotia weight (g) of nine B. napus varieties stem inoculated with four S. sclerotiorum isolates; CU8.20, CU11.7, CU11.19, CU8.24, over two years (mean of five replicates is shown as ◆). Each boxplot visualizes the median, two hinges (25th and 75th percentile), two whiskers (largest value no further than 1.5 x interquartile range) and all outliers.

Figure 3.

Boxplots showing (A) AUDPS (area under the disease progress stairs), (B) seed production (g), (C) total sclerotia number and (D) average sclerotia weight (g) of nine B. napus varieties stem inoculated in 2019 and 2020 with four S. sclerotiorum isolates; CU8.20, CU11.7, CU11.19, CU8.24 (mean of five replicates is shown as ◆). Each boxplot visualizes the median, two hinges (25th and 75th percentile), two whiskers (largest value no further than 1.5 x interquartile range) and all outliers.

Figure 3.

Boxplots showing (A) AUDPS (area under the disease progress stairs), (B) seed production (g), (C) total sclerotia number and (D) average sclerotia weight (g) of nine B. napus varieties stem inoculated in 2019 and 2020 with four S. sclerotiorum isolates; CU8.20, CU11.7, CU11.19, CU8.24 (mean of five replicates is shown as ◆). Each boxplot visualizes the median, two hinges (25th and 75th percentile), two whiskers (largest value no further than 1.5 x interquartile range) and all outliers.

Figure 4.

Biplots following Principal Components Analysis for nine B. napus varieties stem inoculated in 2019 and 2020 with four S. sclerotiorum isolates; CU8.20, CU11.7, CU11.19, CU8.24. Data is colour coded according to A) Year, B) Variety maturity, C) Variety and D) Isolate. Variable abbreviations are AUDPS (area under the disease progress stairs) and TT (accumulated thermal time, °C days).

Figure 4.

Biplots following Principal Components Analysis for nine B. napus varieties stem inoculated in 2019 and 2020 with four S. sclerotiorum isolates; CU8.20, CU11.7, CU11.19, CU8.24. Data is colour coded according to A) Year, B) Variety maturity, C) Variety and D) Isolate. Variable abbreviations are AUDPS (area under the disease progress stairs) and TT (accumulated thermal time, °C days).

Table 1.

Australian Brassica napus varieties used in the study.

Table 1.

Australian Brassica napus varieties used in the study.

| Variety |

Breeding type |

Herbicide tolerance |

Release date |

Inoculation date |

Flowering maturity |

Stem width (mm) |

| 2019 |

2020 |

| Hyola 559TT |

Hybrid |

Triazine |

2012 |

12th Aug |

22nd July |

mid |

13.8 ± 0.4 |

| Hyola 350TT |

Hybrid |

Triazine |

2017 |

29th July |

1st July |

early |

12.1 ± 0.3 |

| Pioneer 43Y23 RR |

Hybrid |

Glyphosate |

2012 |

29th July |

8th July |

early |

13.3 ± 0.3 |

| ATR Bonito |

Open pollinated |

Triazine |

2013 |

5th Aug |

15th July |

early-mid |

11.3 ± 0.3 |

| ATR Mako |

Open pollinated |

Triazine |

2015 |

5th Aug |

8th July |

early-mid |

11.8 ± 0.3 |

| DG 408RR |

Hybrid |

Glyphosate |

2017 |

5th Aug |

15th July |

early-mid |

13.2 ± 0.4 |

| HyTTec Trophy |

Hybrid |

Triazine |

2017 |

5th Aug |

8th July |

early-mid |

13.1 ± 0.3 |

| InVigor T 4510 |

Hybrid |

Triazine |

2016 |

5th Aug |

15th July |

early-mid |

12.6 ± 0.4 |

| Pioneer 44Y27 RR |

Hybrid |

Glyphosate |

2017 |

5th Aug |

22nd July |

early-mid |

13.9 ± 0.4 |

Table 2.

Summary of treatment main effects and interactions on AUDPS, seed production (g), total sclerotia and average sclerotia weight for A) 2019 B. napus varieties either stem or leaf axis inoculated, and B) B. napus varieties stem inoculated in both years, with four known S. sclerotiorum isolates; CU8.20, CU11.7, CU11.19, CU8.24. Variance ratio and degrees of freedom (in brackets) presented. Significance indicated by: ns, not significant, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Table 2.

Summary of treatment main effects and interactions on AUDPS, seed production (g), total sclerotia and average sclerotia weight for A) 2019 B. napus varieties either stem or leaf axis inoculated, and B) B. napus varieties stem inoculated in both years, with four known S. sclerotiorum isolates; CU8.20, CU11.7, CU11.19, CU8.24. Variance ratio and degrees of freedom (in brackets) presented. Significance indicated by: ns, not significant, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

| |

|

Response |

| Treatment |

AUDPS |

Seed

production |

Total sclerotia |

Sclerotia weight a

|

| A) 2019 varieties |

| |

Isolate |

15.37 (3) |

*** |

6.23 (3) |

*** |

9.15 (3) |

*** |

16.80 (3) |

*** |

| |

Variety |

17.93 (8) |

*** |

10.40 (8) |

*** |

6.45 (8) |

*** |

2.06 (8) |

ns |

| |

Inoculation |

7.93 (1) |

** |

45.50 (1) |

*** |

19.08 (1) |

*** |

8.05 (1) |

** |

| |

Isolate x Variety |

2.93 (24) |

*** |

2.35 (24) |

*** |

3.03 (24) |

*** |

1.12 (24) |

ns |

| |

Isolate x Inoculation |

2.66 (3) |

* |

1.20 (3) |

ns |

3.38 (3) |

* |

0.85 (3) |

ns |

| |

Variety x Inoculation |

2.24 (8) |

* |

1.95 (8) |

ns |

1.03 (8) |

ns |

0.69 (8) |

ns |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| B) 2019 and 2020 varieties (stem inoculated only) |

| |

Isolate |

4.81 (3) |

** |

4.44 (3) |

** |

2.73 (3) |

* |

5.23 (3) |

** |

| |

Variety |

16.47 (8) |

*** |

9.46 (8) |

*** |

4.39 (8) |

*** |

0.95 (8) |

ns |

| |

Year |

3.44 (1) |

ns |

114.86 (1) |

*** |

37.25 (1) |

*** |

2.18 (1) |

ns |

| |

Isolate x Variety |

1.45 (24) |

ns |

1.78 (24) |

ns |

2.12 (24) |

** |

0.58 (23) |

ns |

| |

Isolate x Year |

11.64 (3) |

*** |

0.73 (3) |

ns |

0.82 (3) |

ns |

0.76 (3) |

ns |

| |

Variety x Year |

8.67 (8) |

*** |

5.05 (8) |

*** |

4.68 (8) |

*** |

0.63 (8) |

ns |

Table 3.

Principal Component Analysis results showing eigenvalues, percentage variation and component loadings for nine Australian B. napus varieties stem inoculated over two growing seasons with four S. sclerotiorum isolates; CU8.20, CU11.7, CU11.19, CU8.24. AUDPS (area under the disease progress stairs); TT (accumulated thermal time); PC (principal component).

Table 3.

Principal Component Analysis results showing eigenvalues, percentage variation and component loadings for nine Australian B. napus varieties stem inoculated over two growing seasons with four S. sclerotiorum isolates; CU8.20, CU11.7, CU11.19, CU8.24. AUDPS (area under the disease progress stairs); TT (accumulated thermal time); PC (principal component).

| Component |

PC1 |

PC2 |

PC3 |

| Eigenvalues (Standard deviation) |

1.4204 |

1.4128 |

0.9431 |

| Proportion of Variance |

0.3363 |

0.3327 |

0.1482 |

| Cumulative Proportion |

0.3363 |

0.6689 |

0.8171 |

| Loadings |

|

|

|

| |

Seed production |

0.5110 |

-0.3686 |

0.0481 |

| |

Stem width |

-0.1803 |

-0.4349 |

-0.7235 |

| |

AUDPS |

-0.2155 |

0.5951 |

0.1134 |

| |

Sclerotia number |

0.0659 |

0.4946 |

-0.6676 |

| |

TT during AUDPS |

0.5765 |

0.1044 |

-0.0299 |

| |

TT post AUDPS to harvest |

0.5685 |

0.2557 |

-0.1219 |