Submitted:

30 May 2023

Posted:

31 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

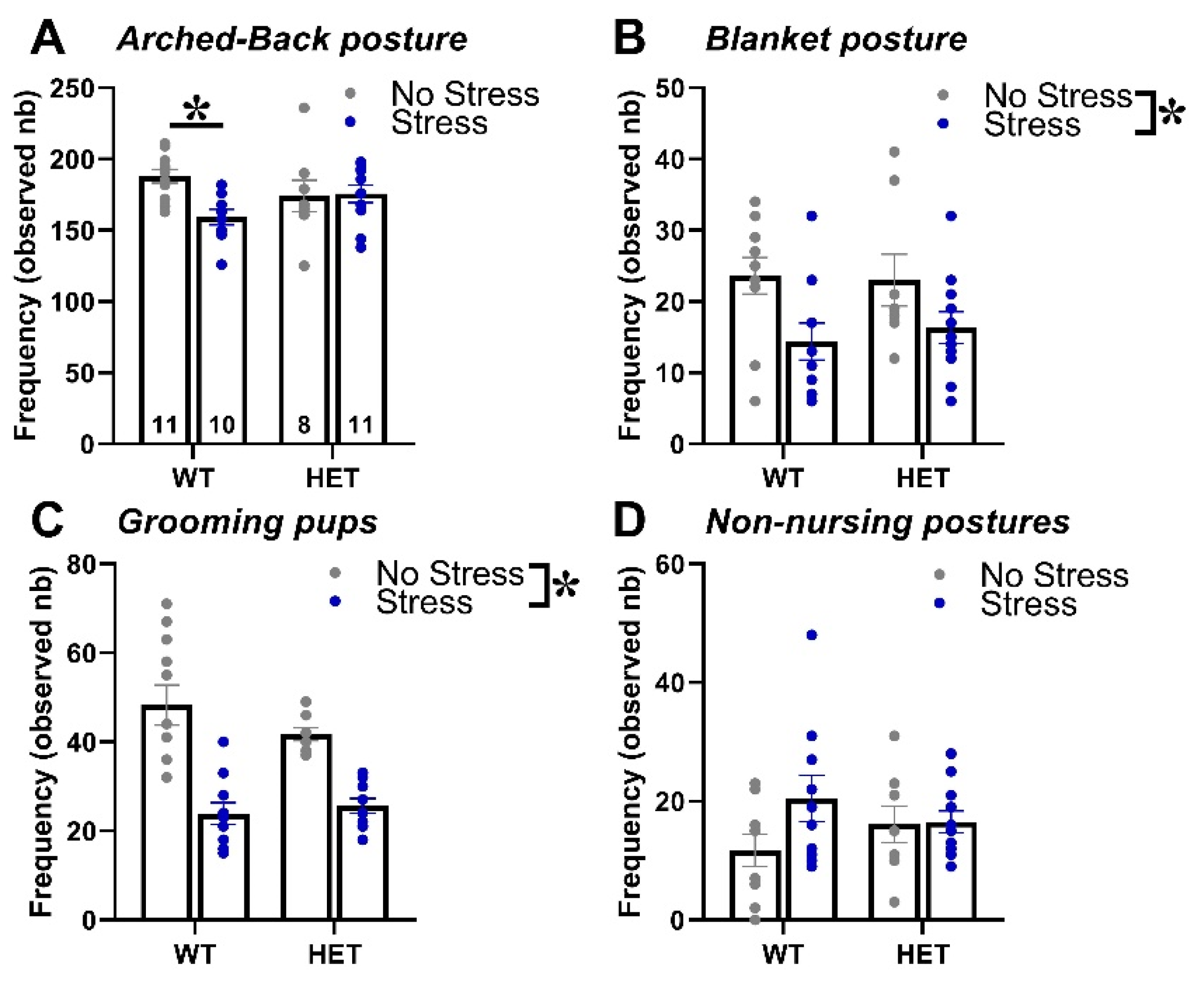

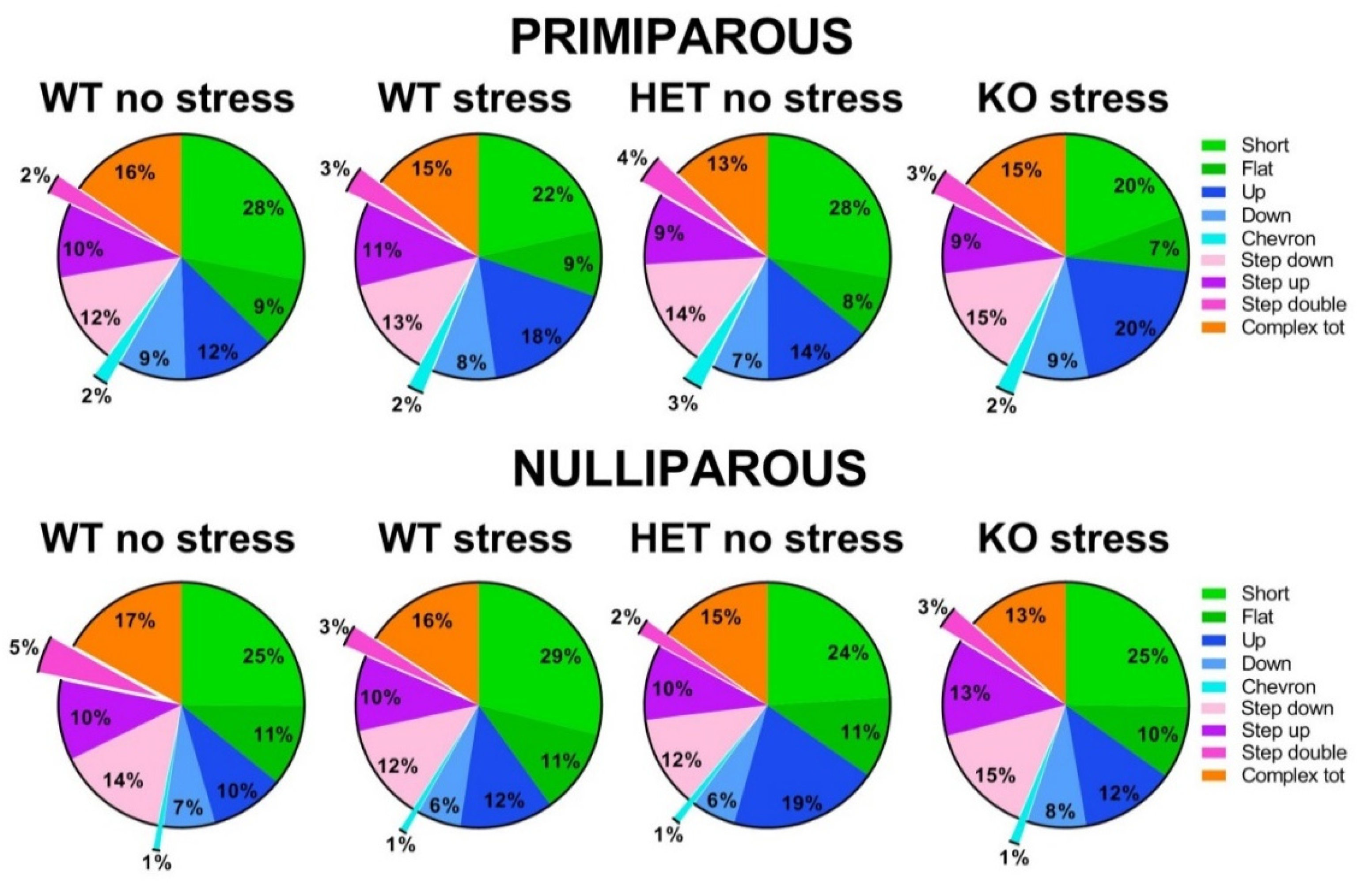

Maternal Behavior

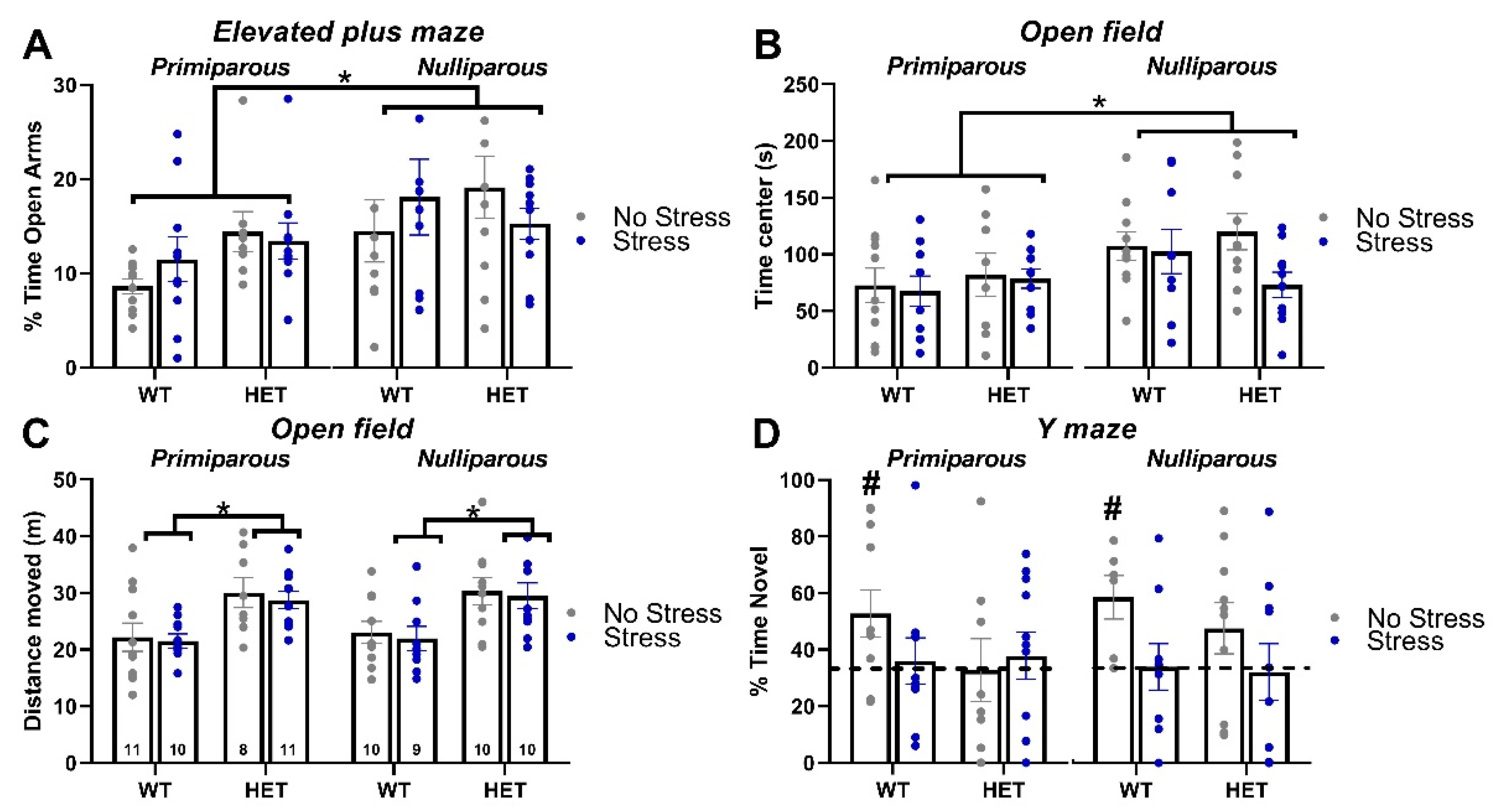

Elevated Plus Maze

Open Field

Y maze

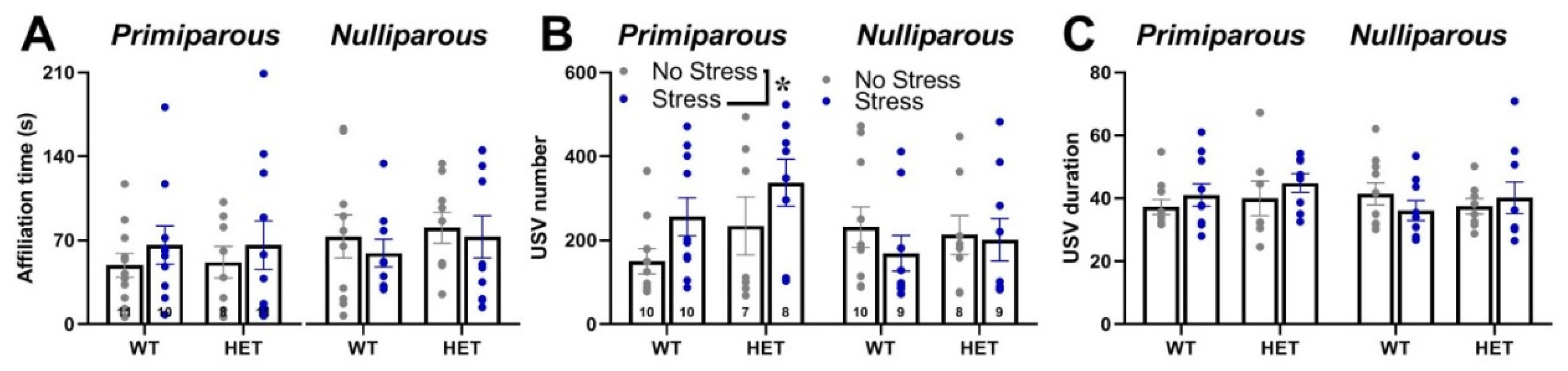

Social interaction and ultrasonic communication

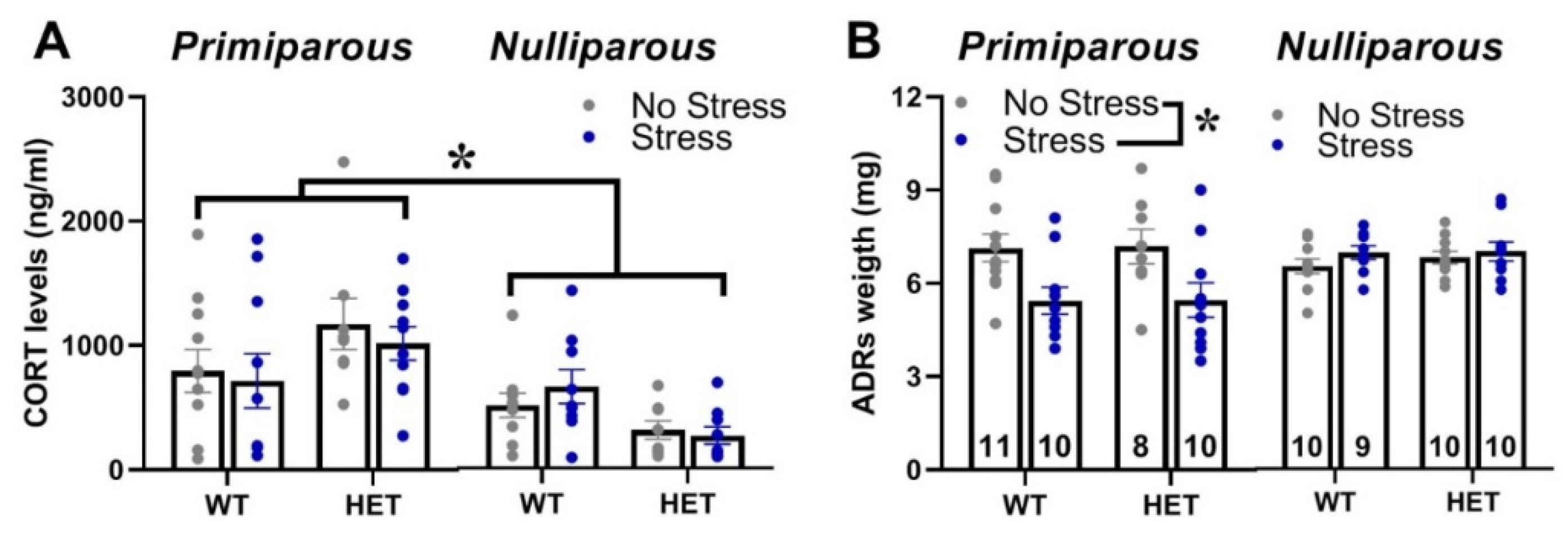

Corticosterone blood levels and adrenal gland weight

3. Discussion

4.4. Materials and Methods

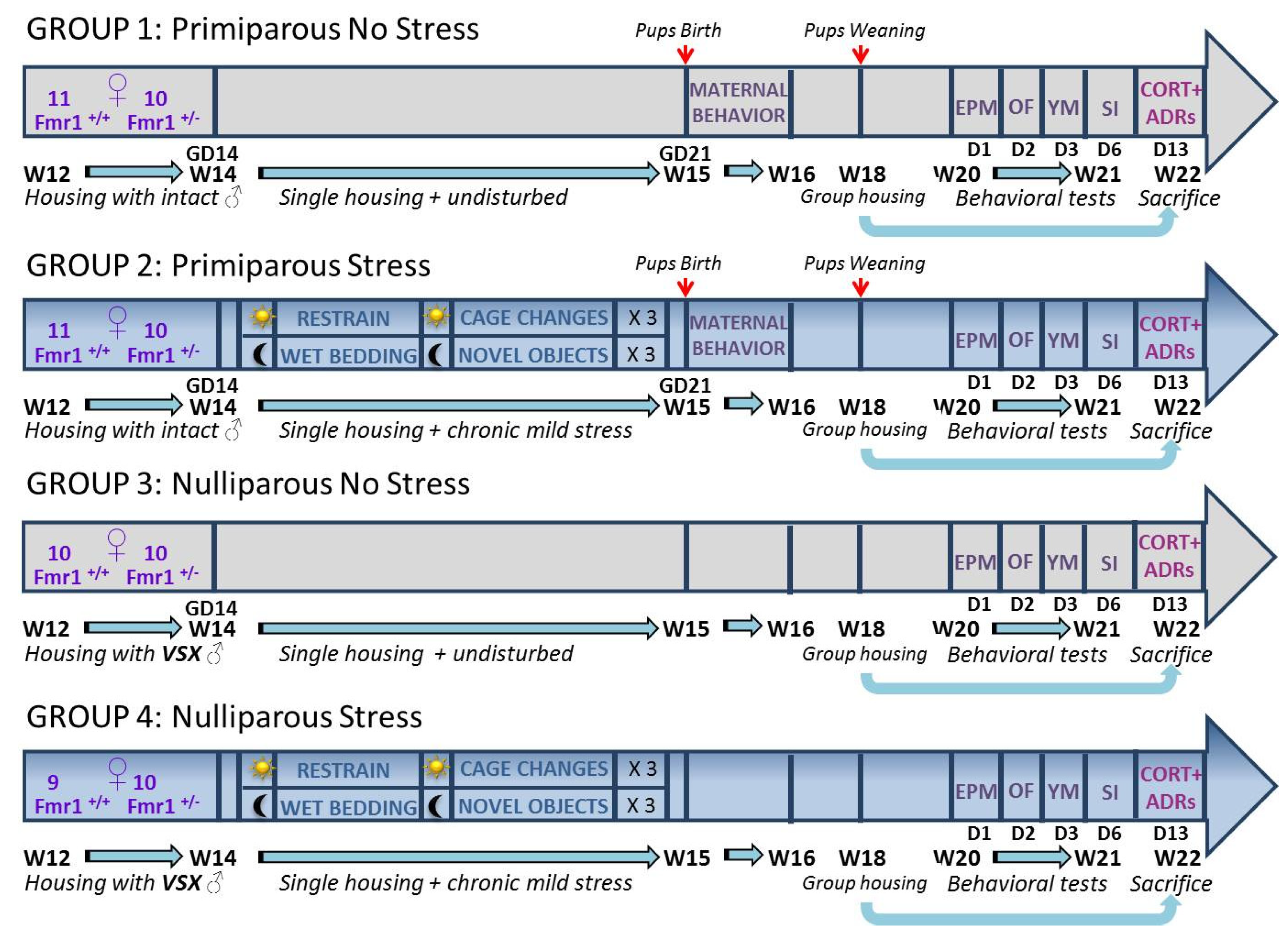

Breeding procedures

Stress procedure

Behavioral testing procedures

Elevated plus maze

Open field

Y maze

Social interaction and ultrasonic communication

Assessment of corticosterone blood levels

Statistical analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Verkerk, A. J., M. Pieretti, J. S. Sutcliffe, Y. H. Fu, D. P. Kuhl, A. Pizzuti, O. Reiner, S. Richards, M. F. Victoria, F. P. Zhang, and et al. "Identification of a Gene (Fmr-1) Containing a Cgg Repeat Coincident with a Breakpoint Cluster Region Exhibiting Length Variation in Fragile X Syndrome." Cell 65, no. 5 (1991): 905-14. [CrossRef]

- Hagerman, Randi Jenssen, and Paul J Hagerman. Fragile X Syndrome: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Research: Taylor & Francis US, 2002.

- Bailey, D. B., Jr., D. D. Hatton, M. Skinner, and G. Mesibov. "Autistic Behavior, Fmr1 Protein, and Developmental Trajectories in Young Males with Fragile X Syndrome." J Autism Dev Disord 31, no. 2 (2001): 165-74. [CrossRef]

- Kerby, D. S., and B. L. Dawson. "Autistic Features, Personality, and Adaptive Behavior in Males with the Fragile X Syndrome and No Autism." Am J Ment Retard 98, no. 4 (1994): 455-62.

- Mazzocco, M. M., W. R. Kates, T. L. Baumgardner, L. S. Freund, and A. L. Reiss. "Autistic Behaviors among Girls with Fragile X Syndrome." J Autism Dev Disord 27, no. 4 (1997): 415-35. [CrossRef]

- Mazzocco, M. M., M. Pulsifer, A. Fiumara, M. Cocuzza, F. Nigro, G. Incorpora, and R. Barone. "Brief Report: Autistic Behaviors among Children with Fragile X or Rett Syndrome: Implications for the Classification of Pervasive Developmental Disorder." J Autism Dev Disord 28, no. 4 (1998): 321-8. [CrossRef]

- Reiss, A. L., and L. Freund. "Behavioral Phenotype of Fragile X Syndrome: Dsm-Iii-R Autistic Behavior in Male Children." Am J Med Genet 43, no. 1-2 (1992): 35-46. [CrossRef]

- Hatton, D. D., J. Sideris, M. Skinner, J. Mankowski, D. B. Bailey, Jr., J. Roberts, and P. Mirrett. "Autistic Behavior in Children with Fragile X Syndrome: Prevalence, Stability, and the Impact of Fmrp." Am J Med Genet A 140A, no. 17 (2006): 1804-13. [CrossRef]

- Turner, G., T. Webb, S. Wake, and H. Robinson. "Prevalence of Fragile X Syndrome." Am J Med Genet 64, no. 1 (1996): 196-7. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, A., M. Raspa, C. Bann, E. Bishop, D. Hessl, P. Sacco, and D. B. Bailey, Jr. "Anxiety, Attention Problems, Hyperactivity, and the Aberrant Behavior Checklist in Fragile X Syndrome." Am J Med Genet A 164A, no. 1 (2014): 141-55. [CrossRef]

- Loesch, D. Z., and D. A. Hay. "Clinical Features and Reproductive Patterns in Fragile X Female Heterozygotes." J Med Genet 25, no. 6 (1988): 407-14. [CrossRef]

- Loesch, D. Z., Q. M. Bui, J. Grigsby, E. Butler, J. Epstein, R. M. Huggins, A. K. Taylor, and R. J. Hagerman. "Effect of the Fragile X Status Categories and the Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein Levels on Executive Functioning in Males and Females with Fragile X." Neuropsychology 17, no. 4 (2003): 646-57. [CrossRef]

- Nolin, S. L., F. A. Lewis, 3rd, L. L. Ye, G. E. Houck, Jr., A. E. Glicksman, P. Limprasert, S. Y. Li, N. Zhong, A. E. Ashley, E. Feingold, S. L. Sherman, and W. T. Brown. "Familial Transmission of the Fmr1 Cgg Repeat." Am J Hum Genet 59, no. 6 (1996): 1252-61.

- Reyniers, E., L. Vits, K. De Boulle, B. Van Roy, D. Van Velzen, E. de Graaff, A. J. Verkerk, H. Z. Jorens, J. K. Darby, B. Oostra, and et al. "The Full Mutation in the Fmr-1 Gene of Male Fragile X Patients Is Absent in Their Sperm." Nat Genet 4, no. 2 (1993): 143-6. [CrossRef]

- Mazzocco, M. M., and J. J. Holden. "Neuropsychological Profiles of Three Sisters Homozygous for the Fragile X Premutation." Am J Med Genet 64, no. 2 (1996): 323-8. [CrossRef]

- Baker, K. B., S. P. Wray, R. Ritter, S. Mason, T. H. Lanthorn, and K. V. Savelieva. "Male and Female Fmr1 Knockout Mice on C57 Albino Background Exhibit Spatial Learning and Memory Impairments." Genes Brain Behav 9, no. 6 (2010): 562-74. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q., F. Sethna, and H. Wang. "Behavioral Analysis of Male and Female Fmr1 Knockout Mice on C57bl/6 Background." Behav Brain Res 271 (2014): 72-8. [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, S. A., P. Bosco, G. Calabrese, C. Bakker, G. B. De Sarro, M. Elia, R. Ferri, and B. A. Oostra. "Audiogenic Seizures Susceptibility in Transgenic Mice with Fragile X Syndrome." Epilepsia 41, no. 1 (2000): 19-23. [CrossRef]

- Nguy, S., and M. V. Tejada-Simon. "Phenotype Analysis and Rescue on Female Fvb.129-Fmr1 Knockout Mice." Front Biol 11, no. 1 (2016): 43-52. [CrossRef]

- Qin, M., J. Kang, and C. B. Smith. "A Null Mutation for Fmr1 in Female Mice: Effects on Regional Cerebral Metabolic Rate for Glucose and Relationship to Behavior." Neuroscience 135, no. 3 (2005): 999-1009. [CrossRef]

- Gauducheau, M., V. Lemaire-Mayo, F. R. D'Amato, D. Oddi, W. E. Crusio, and S. Pietropaolo. "Age-Specific Autistic-Like Behaviors in Heterozygous Fmr1-Ko Female Mice." Autism Res 10, no. 6 (2017): 1067-78. [CrossRef]

- Petroni, V., E. Subashi, M. Premoli, M. Wohr, W. E. Crusio, V. Lemaire, and S. Pietropaolo. "Autistic-Like Behavioral Effects of Prenatal Stress in Juvenile Fmr1 Mice: The Relevance of Sex Differences and Gene-Environment Interactions." Sci Rep 12, no. 1 (2022): 7269. [CrossRef]

- Pietropaolo, S., and E. Subashi. "Mouse Models of Fragile X Syndrome." In Behavioral Genetics of the Mouse, edited by S. Pietropaolo, F. Sluyter and W.E. Crusio, 146-63. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Dawson, G., S. Webb, G. D. Schellenberg, S. Dager, S. Friedman, E. Aylward, and T. Richards. "Defining the Broader Phenotype of Autism: Genetic, Brain, and Behavioral Perspectives." Dev Psychopathol 14, no. 3 (2002): 581-611. [CrossRef]

- Restivo, L., F. Ferrari, E. Passino, C. Sgobio, J. Bock, B. A. Oostra, C. Bagni, and M. Ammassari-Teule. "Enriched Environment Promotes Behavioral and Morphological Recovery in a Mouse Model for the Fragile X Syndrome." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, no. 32 (2005): 11557-62. [CrossRef]

- Oddi, D., E. Subashi, S. Middei, L. Bellocchio, V. Lemaire-Mayo, M. Guzman, W. E. Crusio, F. R. D'Amato, and S. Pietropaolo. "Early Social Enrichment Rescues Adult Behavioral and Brain Abnormalities in a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome." Neuropsychopharmacology 40, no. 5 (2015): 1113-22. [CrossRef]

- Dyer-Friedman, J., B. Glaser, D. Hessl, C. Johnston, L. C. Huffman, A. Taylor, J. Wisbeck, and A. L. Reiss. "Genetic and Environmental Influences on the Cognitive Outcomes of Children with Fragile X Syndrome." J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41, no. 3 (2002): 237-44. [CrossRef]

- Hessl, D., J. Dyer-Friedman, B. Glaser, J. Wisbeck, R. G. Barajas, A. Taylor, and A. L. Reiss. "The Influence of Environmental and Genetic Factors on Behavior Problems and Autistic Symptoms in Boys and Girls with Fragile X Syndrome." Pediatrics 108, no. 5 (2001): E88. [CrossRef]

- Ward, A. J. "A Comparison and Analysis of the Presence of Family Problems During Pregnancy of Mothers of "Autistic" Children and Mothers of Normal Children." Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 20, no. 4 (1990): 279-88. [CrossRef]

- Beversdorf, D. Q., S. E. Manning, A. Hillier, S. L. Anderson, R. E. Nordgren, S. E. Walters, H. N. Nagaraja, W. C. Cooley, S. E. Gaelic, and M. L. Bauman. "Timing of Prenatal Stressors and Autism." J Autism Dev Disord 35, no. 4 (2005): 471-8. [CrossRef]

- Kinney, D. K., A. M. Miller, D. J. Crowley, E. Huang, and E. Gerber. "Autism Prevalence Following Prenatal Exposure to Hurricanes and Tropical Storms in Louisiana." J Autism Dev Disord 38, no. 3 (2008): 481-8. [CrossRef]

- Kinney, D. K., K. M. Munir, D. J. Crowley, and A. M. Miller. "Prenatal Stress and Risk for Autism." Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32, no. 8 (2008): 1519-32. [CrossRef]

- Beversdorf, D. Q., H. E. Stevens, K. G. Margolis, and J. Van de Water. "Prenatal Stress and Maternal Immune Dysregulation in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Potential Points for Intervention." Curr Pharm Des 25, no. 41 (2019): 4331-43. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire-Mayo, V., E. Subashi, N. Henkous, D. Beracochea, and S. Pietropaolo. "Behavioral Effects of Chronic Stress in the Fmr1 Mouse Model for Fragile X Syndrome." Behav Brain Res 320 (2017): 128-35. [CrossRef]

- Qin, M., Z. Xia, T. Huang, and C. B. Smith. "Effects of Chronic Immobilization Stress on Anxiety-Like Behavior and Basolateral Amygdala Morphology in Fmr1 Knockout Mice." Neuroscience 194 (2011): 282-90. [CrossRef]

- Macbeth, A. H., and V. N. Luine. "Changes in Anxiety and Cognition Due to Reproductive Experience: A Review of Data from Rodent and Human Mothers." Neurosci Biobehav Rev 34, no. 3 (2010): 452-67. [CrossRef]

- Brunton, P. J., and J. A. Russell. "The Expectant Brain: Adapting for Motherhood." Nat Rev Neurosci 9, no. 1 (2008): 11-25. [CrossRef]

- Kinsley, C. H. "The Neuroplastic Maternal Brain." Horm Behav 54, no. 1 (2008): 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Darnaudery, M., M. Perez-Martin, F. Del Favero, C. Gomez-Roldan, L. M. Garcia-Segura, and S. Maccari. "Early Motherhood in Rats Is Associated with a Modification of Hippocampal Function." Psychoneuroendocrinology 32, no. 7 (2007): 803-12. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, V., J. M. Billard, P. Dutar, O. George, P. V. Piazza, J. Epelbaum, M. Le Moal, and W. Mayo. "Motherhood-Induced Memory Improvement Persists across Lifespan in Rats but Is Abolished by a Gestational Stress." Eur J Neurosci 23, no. 12 (2006): 3368-74. [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, V., S. Lamarque, M. Le Moal, P. V. Piazza, and D. N. Abrous. "Postnatal Stimulation of the Pups Counteracts Prenatal Stress-Induced Deficits in Hippocampal Neurogenesis." Biol Psychiatry 59, no. 9 (2006): 786-92. [CrossRef]

- Muir, J. L., H. P. Pfister, and A. Ivinskis. "Effects of Prepartum Stress and Postpartum Enrichment on Mother-Infant Interaction and Offspring Problem Solving Ability in Rattus Norvegicus." Journal of Comparative Psychology 99, no. 4 (1985): 468-78.

- Maccari, S., P. V. Piazza, M. Kabbaj, A. Barbazanges, H. Simon, and M. Le Moal. "Adoption Reverses the Long-Term Impairment in Glucocorticoid Feedback Induced by Prenatal Stress." J Neurosci 15, no. 1 Pt 1 (1995): 110-6. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. W., J. R. Seckl, A. T. Evans, B. Costall, and J. W. Smythe. "Gestational Stress Induces Post-Partum Depression-Like Behaviour and Alters Maternal Care in Rats." Psychoneuroendocrinology 29, no. 2 (2004): 227-44. [CrossRef]

- Misdrahi, D., M. C. Pardon, F. Perez-Diaz, N. Hanoun, and C. Cohen-Salmon. "Prepartum Chronic Ultramild Stress Increases Corticosterone and Estradiol Levels in Gestating Mice: Implications for Postpartum Depressive Disorders." Psychiatry Res 137, no. 1-2 (2005): 123-30. [CrossRef]

- Negroni, J., P. Venault, M. C. Pardon, F. Perez-Diaz, G. Chapouthier, and C. Cohen-Salmon. "Chronic Ultra-Mild Stress Improves Locomotor Performance of B6d2f1 Mice in a Motor Risk Situation." Behav Brain Res 155, no. 2 (2004): 265-73. [CrossRef]

- Pardon, M., F. Perez-Diaz, C. Joubert, and C. Cohen-Salmon. "Age-Dependent Effects of a Chronic Ultramild Stress Procedure on Open-Field Behaviour in B6d2f1 Female Mice." Physiol Behav 70, no. 1-2 (2000): 7-13. [CrossRef]

- Pardon, M. C., F. Perez-Diaz, C. Joubert, and C. Cohen-Salmon. "Influence of a Chronic Ultramild Stress Procedure on Decision-Making in Mice." J Psychiatry Neurosci 25, no. 2 (2000): 167-77.

- Champagne, F. A., J. P. Curley, E. B. Keverne, and P. P. Bateson. "Natural Variations in Postpartum Maternal Care in Inbred and Outbred Mice." Physiol Behav 91, no. 2-3 (2007): 325-34. [CrossRef]

- Curley, J. P., C. L. Jensen, B. Franks, and F. A. Champagne. "Variation in Maternal and Anxiety-Like Behavior Associated with Discrete Patterns of Oxytocin and Vasopressin 1a Receptor Density in the Lateral Septum." Horm Behav 61, no. 3 (2012): 454-61. [CrossRef]

- Maggio, John C, and Glayde Whitney. "Ultrasonic Vocalizing by Adult Female Mice (Mus Musculus)." Journal of Comparative Psychology 99, no. 4 (1985): 420.

- Whitney, G., J. R. Coble, M. D. Stockton, and E. F. Tilson. "Ultrasonic Emissions: Do They Facilitate Courtship of Mice." J Comp Physiol Psychol 84, no. 3 (1973): 445-52. [CrossRef]

- Giannoccaro, S., C. Ferraguto, V. Petroni, C. Marcelly, X. Nogues, V. Campuzano, and S. Pietropaolo. "Early Neurobehavioral Characterization of the Cd Mouse Model of Williams-Beuren Syndrome." Cells 12, no. 3 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Petroni, V., E. Subashi, M. Premoli, M. Memo, V. Lemaire, and S. Pietropaolo. "Long-Term Behavioral Effects of Prenatal Stress in the Fmr1-Knock-out Mouse Model for Fragile X Syndrome." Front Cell Neurosci 16 (2022): 917183. [CrossRef]

- Premoli, M., V. Petroni, R. Bulthuis, S. A. Bonini, and S. Pietropaolo. "Ultrasonic Vocalizations in Adult C57bl/6j Mice: The Role of Sex Differences and Repeated Testing." Front Behav Neurosci 16 (2022): 883353. [CrossRef]

- Kat, R., M. Arroyo-Araujo, R. B. M. de Vries, M. A. Koopmans, S. F. de Boer, and M. J. H. Kas. "Translational Validity and Methodological Underreporting in Animal Research: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Fragile X Syndrome (Fmr1 Ko) Rodent Model." Neurosci Biobehav Rev 139 (2022): 104722. [CrossRef]

- Zupan, B., A. Sharma, A. Frazier, S. Klein, and M. Toth. "Programming Social Behavior by the Maternal Fragile X Protein." Genes Brain Behav 15, no. 6 (2016): 578-87. [CrossRef]

- Zupan, B., and M. Toth. "Wild-Type Male Offspring of Fmr-1+/- Mothers Exhibit Characteristics of the Fragile X Phenotype." Neuropsychopharmacology 33, no. 11 (2008): 2667-75. [CrossRef]

- ———. "Fmr-1 as an Offspring Genetic and a Maternal Environmental Factor in Neurodevelopmental Disease." Results Probl Cell Differ 54 (2012): 243-53. [CrossRef]

- Bowman, R., M. Frankfurt, and V. Luine. "Sex Differences in Cognition Following Variations in Endocrine Status." Learn Mem 29, no. 9 (2022): 234-45. [CrossRef]

- Bowman, R. E. "Stress-Induced Changes in Spatial Memory Are Sexually Differentiated and Vary across the Lifespan." J Neuroendocrinol 17, no. 8 (2005): 526-35. [CrossRef]

- Bowman, R. E., K. D. Beck, and V. N. Luine. "Chronic Stress Effects on Memory: Sex Differences in Performance and Monoaminergic Activity." Horm Behav 43, no. 1 (2003): 48-59. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, D. M., J. J. Evans, W. J. Derber, K. A. Johnston, M. L. Laudenslager, L. S. Crnic, and K. N. Maclean. "Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome: Behavioral and Hormonal Response to Stressors." Behav Neurosci 123, no. 3 (2009): 677-86. [CrossRef]

- Qin, M., and C. B. Smith. "Unaltered Hormonal Response to Stress in a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome." Psychoneuroendocrinology 33, no. 6 (2008): 883-9. [CrossRef]

- Sandi, C., and J. Haller. "Stress and the Social Brain: Behavioural Effects and Neurobiological Mechanisms." Nat Rev Neurosci 16, no. 5 (2015): 290-304. [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, M. "The Long-Term Behavioural Consequences of Prenatal Stress." Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32, no. 6 (2008): 1073-86. [CrossRef]

- Laviola, G., W. Adriani, S. Morley-Fletcher, and M. L. Terranova. "Peculiar Response of Adolescent Mice to Acute and Chronic Stress and to Amphetamine: Evidence of Sex Differences." Behav Brain Res 130, no. 1-2 (2002): 117-25. [CrossRef]

- Dallman, M. F., S. F. Akana, A. M. Strack, K. S. Scribner, N. Pecoraro, S. E. La Fleur, H. Houshyar, and F. Gomez. "Chronic Stress-Induced Effects of Corticosterone on Brain: Direct and Indirect." Ann N Y Acad Sci 1018 (2004): 141-50. [CrossRef]

- Nair, B. B., Z. Khant Aung, R. Porteous, M. Prescott, K. A. Glendining, D. E. Jenkins, R. A. Augustine, M. S. B. Silva, S. H. Yip, G. T. Bouwer, C. H. Brown, C. L. Jasoni, R. E. Campbell, S. J. Bunn, G. M. Anderson, D. R. Grattan, A. E. Herbison, and K. J. Iremonger. "Impact of Chronic Variable Stress on Neuroendocrine Hypothalamus and Pituitary in Male and Female C57bl/6j Mice." J Neuroendocrinol 33, no. 5 (2021): e12972. [CrossRef]

- Marchette, R. C. N., M. A. Bicca, Ecds Santos, and T. C. M. de Lima. "Distinctive Stress Sensitivity and Anxiety-Like Behavior in Female Mice: Strain Differences Matter." Neurobiol Stress 9 (2018): 55-63. [CrossRef]

- Safari, M. A., M. Koushkie Jahromi, R. Rezaei, H. Aligholi, and S. Brand. "The Effect of Swimming on Anxiety-Like Behaviors and Corticosterone in Stressed and Unstressed Rats." Int J Environ Res Public Health 17, no. 18 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lupien, S. J., B. S. McEwen, M. R. Gunnar, and C. Heim. "Effects of Stress Throughout the Lifespan on the Brain, Behaviour and Cognition." Nat Rev Neurosci 10, no. 6 (2009): 434-45. [CrossRef]

- Juruena, M. F., F. Eror, A. J. Cleare, and A. H. Young. "The Role of Early Life Stress in Hpa Axis and Anxiety." Adv Exp Med Biol 1191 (2020): 141-53. [CrossRef]

- Pawluski, J. L., K. G. Lambert, and C. H. Kinsley. "Neuroplasticity in the Maternal Hippocampus: Relation to Cognition and Effects of Repeated Stress." Horm Behav 77 (2016): 86-97. [CrossRef]

- Pietropaolo, S., A. Guilleminot, B. Martin, F. R. D'Amato, and W. E. Crusio. "Genetic-Background Modulation of Core and Variable Autistic-Like Symptoms in Fmr1 Knock-out Mice." PLoS ONE 6, no. 2 (2011): e17073. [CrossRef]

- Burkholder, T., C. Foltz, E. Karlsson, C. G. Linton, and J. M. Smith. "Health Evaluation of Experimental Laboratory Mice." Curr Protoc Mouse Biol 2 (2012): 145-65. [CrossRef]

- Pietropaolo, S., and W. E. Crusio. "Strain-Dependent Changes in Acoustic Startle Response and Its Plasticity across Adolescence in Mice." Behav Genet (2009). [CrossRef]

- Pietropaolo, S., M. G. Goubran, C. Joffre, A. Aubert, V. Lemaire-Mayo, W. E. Crusio, and S. Laye. "Dietary Supplementation of Omega-3 Fatty Acids Rescues Fragile X Phenotypes in Fmr1-Ko Mice." Psychoneuroendocrinology 49 (2014): 119-29. [CrossRef]

- Moles, A., and R. D'Amato F. "Ultrasonic Vocalization by Female Mice in the Presence of a Conspecific Carrying Food Cues." Anim Behav 60, no. 5 (2000): 689-94. [CrossRef]

- Moles, A., F. Costantini, L. Garbugino, C. Zanettini, and F. R. D'Amato. "Ultrasonic Vocalizations Emitted During Dyadic Interactions in Female Mice: A Possible Index of Sociability?" Behav Brain Res 182, no. 2 (2007): 223-30. [CrossRef]

- Gaudissard, J., M. Ginger, M. Premoli, M. Memo, A. Frick, and S. Pietropaolo. "Behavioral Abnormalities in the Fmr1-Ko2 Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome: The Relevance of Early Life Phases." Autism Res 10, no. 10 (2017): 1584-96. [CrossRef]

- Maggio, J. C., and G. Whitney. "Ultrasonic Vocalizing by Adult Female Mice (Mus Musculus)." J Comp Psychol 99, no. 4 (1985): 420-36.

- D'Amato, F. R., and A. Moles. "Ultrasonic Vocalizations as an Index of Social Memory in Female Mice." Behav Neurosci 115, no. 4 (2001): 834-40. [CrossRef]

- Premoli, M., S. A. Bonini, A. Mastinu, G. Maccarinelli, F. Aria, G. Paiardi, and M. Memo. "Specific Profile of Ultrasonic Communication in a Mouse Model of Neurodevelopmental Disorders." Sci Rep 9, no. 1 (2019): 15912. [CrossRef]

- Scattoni, M. L., L. Ricceri, and J. N. Crawley. "Unusual Repertoire of Vocalizations in Adult Btbr T+Tf/J Mice During Three Types of Social Encounters." Genes Brain Behav 10, no. 1 (2011): 44-56. [CrossRef]

- Caruso, A., L. Ricceri, and M. L. Scattoni. "Ultrasonic Vocalizations as a Fundamental Tool for Early and Adult Behavioral Phenotyping of Autism Spectrum Disorder Rodent Models." Neurosci Biobehav Rev 116 (2020): 31-43. [CrossRef]

- Caligioni, C. S. "Assessing Reproductive Status/Stages in Mice." Curr Protoc Neurosci Appendix 4 (2009): Appendix 4I. [CrossRef]

- Vandesquille, M., M. Baudonnat, L. Decorte, C. Louis, P. Lestage, and D. Beracochea. "Working Memory Deficits and Related Disinhibition of the Camp/Pka/Creb Are Alleviated by Prefrontal Alpha4beta2*-Nachrs Stimulation in Aged Mice." Neurobiol Aging 34, no. 6 (2013): 1599-609. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).