Submitted:

30 May 2023

Posted:

31 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Morphological Traits of Tomato Plants

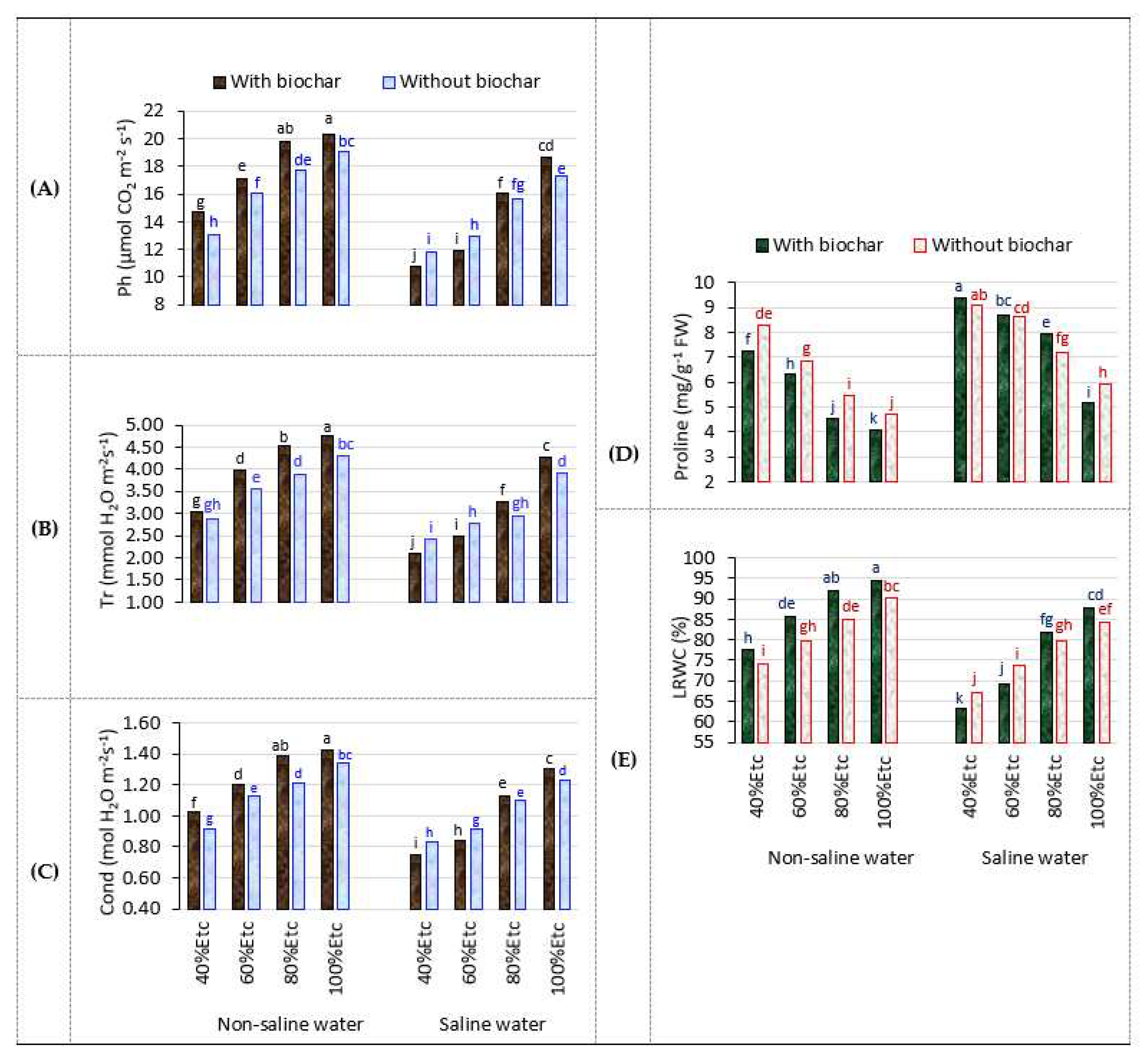

2.2. Physiological Parameters.

2.3. Photosynthetic Pigments

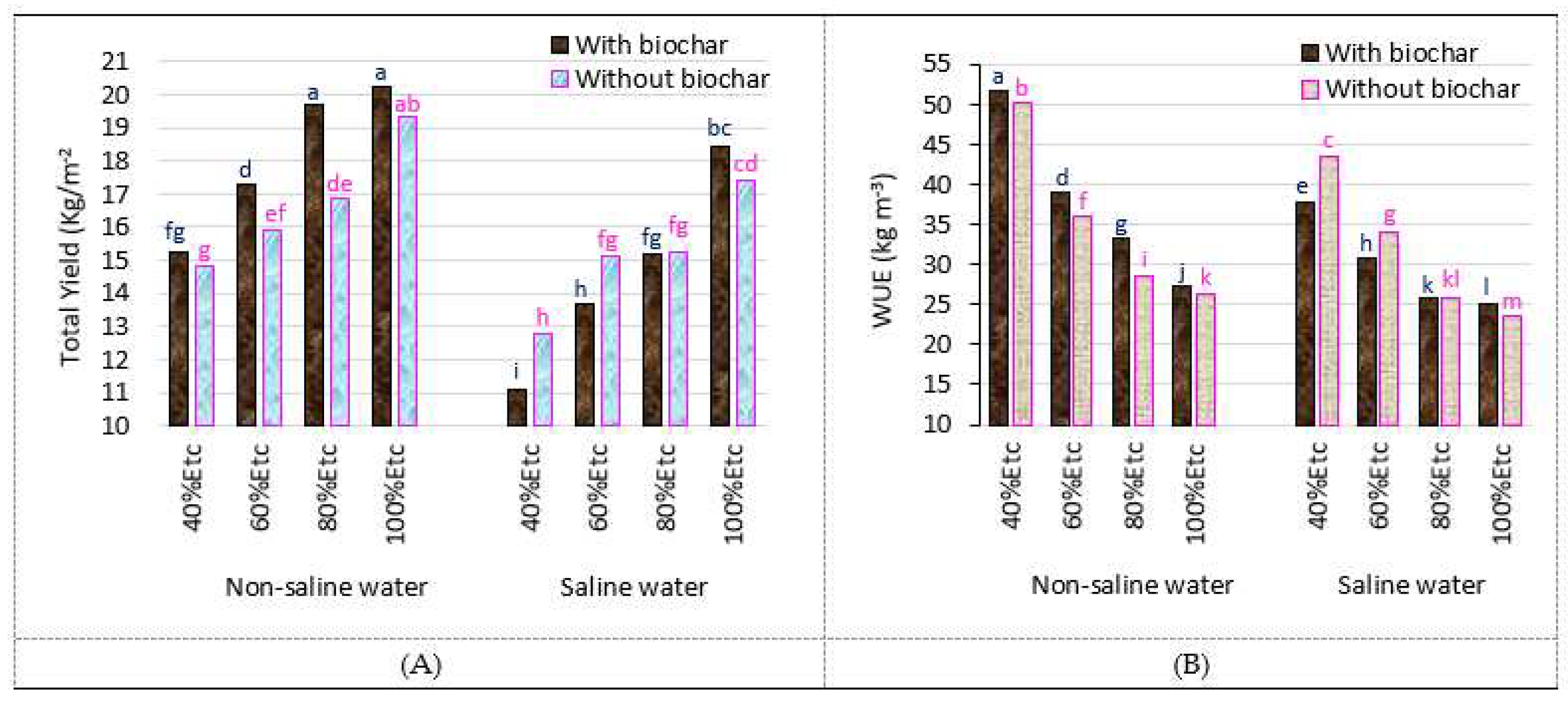

2.4. Fruit Yield (Kg m-2) and WUE (Kg m-3) of Tomato Plants

2.5. WUE Improvement and Irrigation Water Savings

3. Materials and Methods

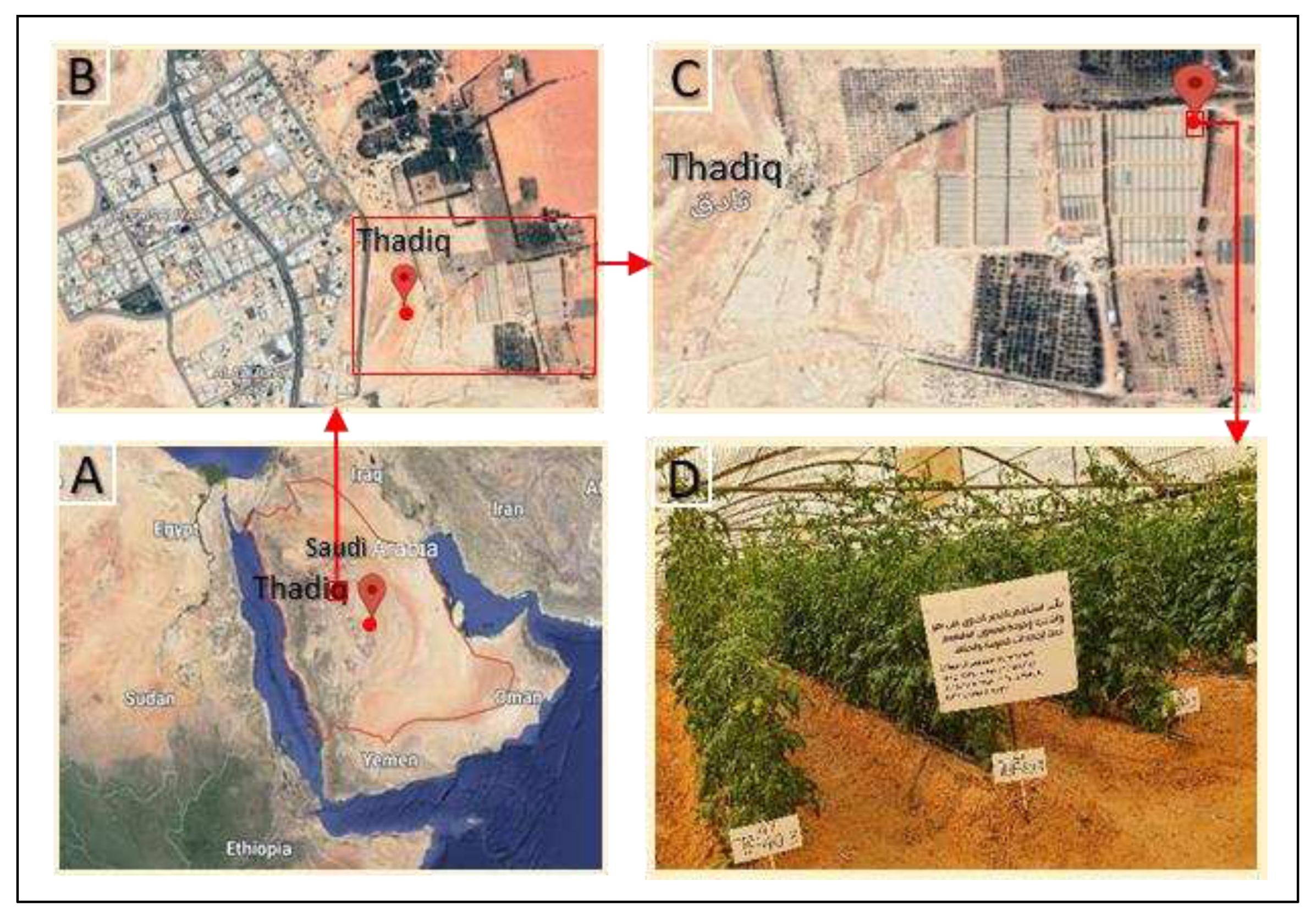

3.1. Experimental Site

3.2. Treatments and Experiment Design

3.3. Biochar Production

3.4. The Measurements

3.4.1. Growth and Physiological Parameters

3.4.2. Total Yield and WUE

3.5. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdul-Hammed, M.; Bolarinwa, I.F.; Adebayo, L.O.; Akindele, S.L. Kinetics of the degradation of carotenoid antioxidants in tomato paste. Adv. J. Food. Sci. Technol. 2016, 11, 734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, P.; Ahanger, M.A.; Alam, P.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wijaya, L.; Ali, S.; Ashraf, M. Silicon (Si) supplementation alleviates NaCl toxicity in mung bean [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek] through the modifications of physio-biochemical attributes and key antioxidant enzymes. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 38, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Modi, P.; Dave, A.; Vijapura, A.; Patel, D.; Patel, M. Effect of abiotic stress on crops. Sustainable crop production 2020, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Omran, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Alharbi, A. Effects of biochar and compost on soil physical quality indices. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2021, 52, 2482–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Q.; Gan, Y.; Zhao, C.; Xu, H.-L.; Waskom, R.M.; Niu, Y.; Siddique, K.H. Regulated deficit irrigation for crop production under drought stress. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Liu, H.; Sun, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, H. Comparison of shuttleworth-wallace model and dual crop coefficient method for estimating evapotranspiration of tomato cultivated in a solar greenhouse. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 217, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquah, S.J.; Yan, H.; Zhang, C.; Wang, G.; Zhao, B.; Wu, H.; Zhang, H. Application and evaluation of Stanghellini model in the determination of crop evapotranspiration in a naturally ventilated greenhouse. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi, A.G.; Al-Omran, A.; Alkhasha, A.; Alharbi, A.R. Impacts of biochar on hydro-Physical properties of sandy soil under differentirrigation regimes for enhanced tomato growth. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Wahid, A.; Kobayashi, N.; Fujita, D.; Basra, S. Plant drought stress: effects, mechanisms and management. Sustain. Agric. 2009, 153–188. [Google Scholar]

- Lahoz, I.; Pérez-de-Castro, A.; Valcárcel, M.; Macua, J.I.; Beltran, J.; Roselló, S.; Cebolla-Cornejo, J. Effect of water deficit on the agronomical performance and quality of processing tomato. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 200, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obadi, A.; AlHarbi, A.; Abdel-Razzak, H.; Al-Omran, A. Biochar and compost as soil amendments: effect on sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) growth under partial root zone drying irrigation. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Biswas, A. Comprehensive approaches in rehabilitating salt affected soils: a review on Indian perspective. Open transactions on geosciences 2014, 1, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, M.; Dhakarey, R.; Hazman, M.; Miro, B.; Kohli, A.; Nick, P. Exploring jasmonates in the hormonal network of drought and salinity responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhi, G.S.; Kaur, M.; Kaushik, P.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Alsahli, A.A.; Ahmad, P. Arbuscular mycorrhiza in combating abiotic stresses in vegetables: An eco-friendly approach. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 1465–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teh, K.-Y.; Ro, S.-C.; Ray, P. Mapping water salinity in coastal areas affected by rising sea level. In Technology Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development; Springer, 2022; pp. 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Du, T.; Mao, X.; Ding, R.; Shukla, M.K. A comprehensive method of evaluating the impact of drought and salt stress on tomato growth and fruit quality based on EPIC growth model. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 213, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ors, S.; Ekinci, M.; Yildirim, E.; Sahin, U.; Turan, M.; Dursun, A. Interactive effects of salinity and drought stress on photosynthetic characteristics and physiology of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) seedlings. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 137, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgari, R.; Franzoni, G.; Ferrante, A. Biostimulants application in horticultural crops under abiotic stress conditions. Agronomy 2019, 9, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Biochar for environmental management: science, technology and implementation; Routledge, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oni, B.A.; Oziegbe, O.; Olawole, O.O. Significance of biochar application to the environment and economy. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2019, 64, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkharabsheh, H.M.; Seleiman, M.F.; Battaglia, M.L.; Shami, A.; Jalal, R.S.; Alhammad, B.A.; Almutairi, K.F.; Al-Saif, A.M. Biochar and its broad impacts in soil quality and fertility, nutrient leaching and crop productivity: A review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yang, L.; Hu, Z.; Xue, J.; Lu, Y.; Chen, X.; Griffiths, B.S.; Whalen, J.K.; Liu, M. Biochar exerts negative effects on soil fauna across multiple trophic levels in a cultivated acidic soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2020, 56, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faloye, O.; Alatise, M.; Ajayi, A.; Ewulo, B. Effects of biochar and inorganic fertiliser applications on growth, yield and water use efficiency of maize under deficit irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 217, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M.; Hayat, R.; Hussain, Q.; Ahmed, M.; Pan, G.; Tahir, M.I.; Imran, M.; Irfan, M. Biochar improves soil quality and N2-fixation and reduces net ecosystem CO2 exchange in a dryland legume-cereal cropping system. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 186, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 25. Baiamonte, G.; Crescimanno, G.; Parrino, F.; De Pasquale, C. Biochar amended soils and water systems: investigation of physical and structural properties. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 12108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kul, R.; Arjumend, T.; Ekinci, M.; Yildirim, E.; Turan, M.; Argin, S. Biochar as an organic soil conditioner for mitigating salinity stress in tomato. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 67, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, A.R.A.; Al-Wabel, M.I.; Abdulaziz, A.-H.; Mahmoud, W.-A.; EL-NAGGAR, A.H.; AHMAD, M.; Abdulelah, A.-F.; Abdulrasoul, A.-O. Conocarpus biochar induces changes in soil nutrient availability and tomato growth under saline irrigation. Pedosphere 2016, 26, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Qayyum, M.F.; Ok, Y.S.; Ibrahim, M.; Riaz, M.; Arif, M.S.; Hafeez, F.; Al-Wabel, M.I.; Shahzad, A.N. Biochar soil amendment on alleviation of drought and salt stress in plants: a critical review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 2017, 24, 12700–12712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazman, M.Y.; El-Sayed, M.E.; Kabil, F.F.; Helmy, N.A.; Almas, L.; McFarland, M.; Shams El Din, A.; Burian, S. Effect of biochar application to fertile soil on tomato crop production under Saline irrigation regime. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wabel, M.I.; Al-Omran, A.; El-Naggar, A.H.; Nadeem, M.; Usman, A.R. Pyrolysis temperature induced changes in characteristics and chemical composition of biochar produced from conocarpus wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 131, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabhi, R.; Basile, L.; Kirk, D.W.; Giorcelli, M.; Tagliaferro, A.; Jia, C.Q. Electrical conductivity of wood biochar monoliths and its dependence on pyrolysis temperature. Biochar 2020, 2, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnusamy, V.; Jagendorf, A.; Zhu, J.K. Understanding and improving salt tolerance in plants. Crop Sci. 2005, 45, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harbi, A.R.; Al-Omran, A.M.; Alenazi, M.M.; Wahb-Allah, M.A. Salinity and deficit irrigation influence tomato growth, yield and water Use efficiency at different developmental stages. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2015, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, U.; Raheel, M.; Ashraf, W.; Ur Rehman, A.; Zahid, M.S.; Moustafa, M.; Ali, M.A. Influence of Biochar Application on morpho-physiological attributes of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill) and soil Properties. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2023, 54, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, B.; Zhu, L.; Xing, B. Effects and mechanisms of biochar-microbe interactions in soil improvement and pollution remediation: a review. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antala, M.; Sytar, O.; Rastogi, A.; Brestic, M. Potential of karrikins as novel plant growth regulators in agriculture. Plants 2019, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, S.S.; Andersen, M.N.; Naveed, M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Liu, F. Interactive effect of biochar and plant growth-promoting bacterial endophytes on ameliorating salinity stress in maize. Funct. Plant Biol. 2015, 42, 770–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabay, U.; Toptas, A.; Yanik, J.; Aktas, L. Does biochar alleviate salt stress impact on growth of salt-sensitive crop common bean. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2021, 52, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; Ekinci, M.; Ors, S.; Turan, M.; Yildiz, S.; Yildirim, E. Effects of individual and combined effects of salinity and drought on physiological, nutritional and biochemical properties of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata). Sci. Hortic. 2018, 240, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, M.; Ors, S.; Yildirim, E.; Turan, M.; Sahin, U.; Dursun, A.; Kul, R. Determination of physiological indices and some antioxidant enzymes of chard exposed to nitric oxide under drought stress. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 67, 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhoshan, M.; Ramin, A.A.; Zahedi, M.; Sabzalian, M.R. Effects of water deficit on shoot, root and some physiological characteristics in some greenhouse grown potato cultivars. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harbi, A.; Al-Omran, A.; Alqardaeai, T.; Abdel-Rassak, H.; Alharbi, K.; Obadi, A.; Saad, M. Grafting affects tomato growth, productivity, and water use efficiency under different water regimes. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2018, 20, 1227–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Gharsallah, C.; Fakhfakh, H.; Grubb, D.; Gorsane, F. Effect of salt stress on ion concentration, proline content, antioxidant enzyme activities and gene expression in tomato cultivars. AoB Plants 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parveen, A.; Liu, W.; Hussain, S.; Asghar, J.; Perveen, S.; Xiong, Y. Silicon priming regulates morpho-physiological growth and oxidative metabolism in maize under drought stress. Plants 2019, 8, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahib, R.H.; Migdadi, H.M.; Al Ghamdi, A.A.; Alwahibi, M.S.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Al-Selwey, W.A. Assessment of morpho-physiological, biochemical and antioxidant responses of tomato landraces to salinity stress. Plants 2021, 10, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, S.S.; Li, G.; Andersen, M.N.; Liu, F. Biochar enhances yield and quality of tomato under reduced irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 138, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbna, G.H.; Dongli, S.; Zhipeng, L.; Elshaikh, N.A.; Guangcheng, S.; Timm, L.C. Effects of deficit irrigation and biochar addition on the growth, yield, and quality of tomato. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 222, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wei, J.; Guo, L.; Fang, H.; Liu, X.; Liang, K.; Niu, W.; Liu, F.; Siddique, K.H. Effects of two biochar types on mitigating drought and salt stress in tomato seedlings. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafakheri, A.; Siosemardeh, A.; Bahramnejad, B.; Struik, P.; Sohrabi, Y. Effect of drought stress on yield, proline and chlorophyll contents in three chickpea cultivars. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2010, 4, 580–585. [Google Scholar]

- Kazerooni, E.A.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Rashid, U.; Kang, S.-M.; Lee, I.-J. Actinomucor elegans and Podospora bulbillosa positively improves endurance to water deficit and Salinity Stresses in tomato plants. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Mu, X.; Shao, H.; Wang, H.; Brestic, M. Global plant-responding mechanisms to salt stress: physiological and molecular levels and implications in biotechnology. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2015, 35, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, M.; Ahmad, W.; Hussain, F.; Ahamd, W.; Numan, M.; Shah, M.; Ahmad, I. Phytostabalization of the heavy metals in the soil with biochar applications, the impact on chlorophyll, carotene, soil fertility and tomato crop yield. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Chang, T.; Shaghaleh, H.; Hamoud, Y.A. Improvement of photosynthesis by biochar and vermicompost to Enhance Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) yield under greenhouse conditions. Plants 2022, 11, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeem, S.M.; Imran, M.; Naveed, M.; Khan, M.Y.; Ahmad, M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Crowley, D.E. Synergistic use of biochar, compost and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for enhancing cucumber growth under water deficit conditions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 5139–5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwal, S.; Ilyas, N.; Shabir, S.; Saeed, M.; Gul, R.; Zahoor, M.; Batool, N.; Mazhar, R. Application of biochar in mitigation of negative effects of salinity stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Plant Nutr. 2018, 41, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomran, A.; Louki, I.; Aly, A.; Nadeem, M. Impact of deficit irrigation on soil salinity and cucumber yield under greenhouse condition in an arid environment. 2013.

- Hossain, M.K.; Strezov, V.; Chan, K.Y.; Nelson, P.F. Agronomic properties of wastewater sludge biochar and bioavailability of metals in production of cherry tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum). Chemosphere 2010, 78, 1167–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Yu, H.; Niu, W.; Kharbach, M. Biochar promotes nitrogen transformation and tomato yield by regulating nitrogen-related microorganisms in tomato cultivation soil. Agronomy 2021, 11, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Wei, Z.; Wan, H.; Liu, F. Effect of biochar addition and reduced irrigation regimes on growth, physiology and water use efficiency of cotton plants under salt stress. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 198, 116702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Fan, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Hao, X.; Li, S.; Kang, S. Response of yield and quality of greenhouse tomatoes to water and salt stresses and biochar addition in Northwest China. Agricultural Water Management 2022, 270, 107736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Idowu, O.J.; Brewer, C.E. Using Agricultural Residue Biochar to Improve Soil Quality of Desert Soils. Agriculture 2016, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, C.; Van der Salm, C.; Hofland-Zijlstra, J.; Streminska, M.; Eveleens, B.; Regelink, I.; Fryda, L.; Visser, R. Biochar for horticultural rooting media improvement: evaluation of biochar from gasification and slow pyrolysis. Agronomy 2017, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements-FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. Fao, Rome 1998, 300, D05109. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Wabel, M.I.; Usman, A.R.A.; Al-Farraj, A.S.; Ok, Y.S.; Abduljabbar, A.; Al-Faraj, A.I.; Sallam, A.S. Date palm waste biochars alter a soil respiration, microbial biomass carbon, and heavy metal mobility in contaminated mined soil. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 2019, 41, 1705–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman, A.R.; Abduljabbar, A.; Vithanage, M.; Ok, Y.S.; Ahmad, M.; Ahmad, M.; Elfaki, J.; Abdulazeem, S.S.; Al-Wabel, M.I. Biochar production from date palm waste: Charring temperature induced changes in composition and surface chemistry. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2015, 115, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, R.E.; Bingham, G.E. Rapid estimates of relative water content. Plant physiology 1974, 53, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellburn, A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. Journal of plant physiology 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant physiology 1949, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claussen, W. Proline as a measure of stress in tomato plants. Plant science 2005, 168, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelli, S.; Perniola, M.; Ferrara, A.; Di Tommaso, T. Yield response factor to water (Ky) and water use efficiency of Carthamus tinctorius L. and Solanum melongena L. Agricultural water management 2007, 92, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.F.; Yu, H.; Yang, X.; Jiang, W. Deficit irrigation affects growth, yield, vitamin C content, and irrigation water use efficiency of hot pepper grown in soilless culture. HortScience 2014, 49, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, R.G.D.; Torrie, J.H. Principles and procedures of statistics, a biometrical approach; McGraw-Hill Kogakusha, Ltd., 1980. [Google Scholar]

| Treatments | Plant height (cm) |

Leaf Area index (cm2) |

Stem diameter (mm) | fresh weight of plant (g) |

Dry weight of plant (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salinity | |||||

| S 0.9 ds m-1 | 334.05 a | 7345.68 a | 15.65 a | 1769.50 a | 223.43 a |

| S 2.3 ds m-1 | 281.69 b | 6262.42 b | 12.36 b | 1393.03 b | 194.23 b |

| Irrigation Levels (%Etc) | |||||

| 100 | 359.01 a | 7867.46 a | 17.23 a | 1957.99 a | 241.08 a |

| 80 | 332.89 b | 7082.46 b | 14.87 b | 1737.82 b | 222.85 b |

| 60 | 283.87 c | 6454.43 c | 13.04 c | 1408.95 c | 197.23 c |

| 40 | 255.73 d | 5811.84 d | 10.89 d | 1220.31 d | 174.17 d |

| Biochar | |||||

| BC0% | 303.60 b | 6711.23 b | 13.58 b | 1542.35 b | 203.08 b |

| BC5% | 312.14 a | 6896.87 a | 14.43 a | 1620.19 a | 214.59 a |

| salinity | Irrigation Levels (%Etc) |

Biochar (%) |

height (cm) |

Leaf area index (cm2) |

stem diameter (mm) | fresh weight of plant (g) |

Dry weight of plant (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0.9 ds m-1 | 100 | BC0% | 363.49 bc | 8054.68 b | 18.14 b | 1991.03 b | 234.75 c |

| BC5% | 383.82 a | 8547.19 a | 19.17 a | 2137.60 a | 255.00 ab | ||

| 80 | BC0% | 348.34 de | 7070.38 ef | 15.49 de | 1819.51 d | 221.15 de | |

| BC5% | 366.63 b | 7934.80 bc | 18.53 ab | 2067.97 ab | 265.52 a | ||

| 60 | BC0% | 310.89 g | 6818.79 fg | 13.85 fg | 1551.13 f | 210.94 ef | |

| BC5% | 334.07 f | 7573.61 cd | 16.09 d | 1722.16 e | 217.32 e | ||

| 40 | BC0% | 268.67 i | 6157.50 h | 11.58 hi | 1398.91 h | 181.76 h | |

| BC5% | 296.51 h | 6608.46 g | 12.38 h | 1467.74 gh | 201.03 fg | ||

| S2.3 ds m-1 | 100 | BC0% | 336.18 ef | 7222.09 de | 14.66 ef | 1794.42 de | 231.48 cd |

| BC5% | 352.55 cd | 7645.89 c | 16.94 c | 1908.91 c | 243.10 bc | ||

| 80 | BC0% | 304.21 gh | 6737.78 fg | 13.28 g | 1501.86 fg | 195.82 g | |

| BC5% | 312.35 g | 6586.88 g | 12.18 h | 1561.93 f | 208.91 ef | ||

| 60 | BC0% | 256.71 i | 6004.79 h | 11.33 i | 1229.00 i | 182.15 h | |

| BC5% | 233.79 j | 5420.54 i | 10.89 ij | 1133.52 j | 178.49 hi | ||

| 40 | BC0% | 240.33 j | 5623.81 i | 10.30 j | 1052.90 k | 166.56 i | |

| BC5% | 217.42 k | 4857.58 j | 9.30 k | 961.71 l | 147.34 j |

| Treatments | Photosynthesis Rate (µmol CO2 m-2 s-1) |

Transpiratio Rate (mmol H2O m-2s-1) |

Conductivity (mol H2O m-2s-1) |

Proline (mg/g-1 FW) | LRWC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| salinity | |||||

| S 0.9 ds m-1 | 17.23 a | 3.87 a | 1.20 a | 5.94 b | 84.84 a |

| S 2.3 ds m-1 | 14.38 b | 3.02 b | 1.01 b | 7.76 a | 75.84 b |

| Irrigation Levels (%Etc) | |||||

| 100 | 18.82 a | 4.31 a | 1.32 a | 4.97 d | 89.17 a |

| 80 | 17.29 b | 3.65 b | 1.20 b | 6.29 c | 84.61 b |

| 60 | 14.53 c | 3.21 c | 1.02 c | 7.62 b | 77.13 d |

| 40 | 12.58 d | 2.60 d | 0.88 d | 8.51 a | 70.46 d |

| Biochar | |||||

| BC0% | 15.45 b | 3.34 b | 1.08 b | 7.02 a | 79.20 b |

| BC5% | 16.16 a | 3.55 a | 1.13 a | 6.68 b | 81.48 a |

| Treatments | Leaf Green Index (SPAD) |

Chlorophyll a (mg/g−1 FW) | Chlorophyll b (mg/g−1 FW) | Total Chlorophyll (mg/g−1 FW) | Carotenoids (mg/g−1 FW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| salinity | |||||

| S 0.9 ds m-1 | 48.63 a | 2.55 a | 1.11 a | 3.66 a | 4.91 a |

| S 2.3 ds m-1 | 39.21 b | 2.28 b | 0.93 b | 3.21 b | 4.23 b |

| Irrigation Levels (%Etc) | |||||

| 100 | 53.91 a | 2.74 a | 1.17 a | 3.91 a | 5.26 a |

| 80 | 48.13 b | 2.57 b | 1.10 b | 3.68 b | 4.86 b |

| 60 | 39.78 c | 2.30 c | 0.93 c | 3.23 c | 4.35 c |

| 40 | 33.87 d | 2.05 d | 0.87 d | 2.92 d | 3.79 d |

| Biochar | |||||

| BC0% | 42.72 b | 2.36 b | 1.00 b | 3.36 b | 4.47 b |

| BC5% | 45.12 a | 2.47 a | 1.04 a | 3.51 a | 4.66 a |

| salinity | Irrigation Levels (%Etc) |

Biochar (%) |

Leaf Green Index (SPAD) |

Chlorophyll a (mg/g−1 FW) | Chlorophyll b (mg/g−1 FW) | Total Chlorophyll (mg/g−1 FW) | Carotenoids (mg/g−1 FW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S 0.9 ds m-1 | 100 | BC0% | 57.80 b | 2.75 bc | 1.12 cd | 3.87 b | 5.34 c |

| BC5% | 60.80 a | 2.86 a | 1.29 a | 4.15 a | 5.77 a | ||

| 80 | BC0% | 48.43 d | 2.61 e | 1.06 de | 3.68 cd | 4.71 fg | |

| BC5% | 58.03 b | 2.82 ab | 1.26 ab | 4.09 a | 5.56 b | ||

| 60 | BC0% | 43.10 f | 2.27 h | 1.02 ef | 3.28 ef | 4.68 fg | |

| BC5% | 45.53 e | 2.63 de | 1.14 c | 3.77 bc | 4.98 de | ||

| 40 | BC0% | 35.97 i | 2.13 i | 0.92 g | 3.06 g | 3.98 i | |

| BC5% | 39.33 h | 2.31 gh | 1.06 de | 3.37 e | 4.25 h | ||

| S 2.3 ds m-1 | 100 | BC0% | 46.37 e | 2.64 de | 1.06 de | 3.71 cd | 4.85 ef |

| BC5% | 50.67 c | 2.69 cd | 1.22 b | 3.92 b | 5.11 d | ||

| 80 | BC0% | 41.17 g | 2.35 g | 1.01 f | 3.35 e | 4.53 g | |

| BC5% | 44.87 e | 2.51 f | 1.08 d | 3.59 d | 4.65 fg | ||

| 60 | BC0% | 36.97 i | 2.24 h | 0.91 g | 3.15 fg | 4.10 hi | |

| BC5% | 33.50 j | 2.05 j | 0.67 h | 2.72 h | 3.66 j | ||

| 40 | BC0% | 31.93 j | 1.90 k | 0.89 g | 2.79 h | 3.60 j | |

| BC5% | 28.23 k | 1.87 k | 0.61 i | 2.48 i | 3.32 k |

| Treatments | Total water applied (m-3/ m-2) |

Saving water (%) |

Total Yield (Kg/ m-2) |

Reduction in yield (%) |

WUE (kg m-3) |

Improvement in WUE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| salinity | ||||||

| S 0.9 ds m-1 | ------ | ------ | 17.42 a | 00.00 | 36.53 a | 00.00 |

| S 2.3 ds m-1 | ------ | ------ | 14.87 b | 14.64 | 30.76 b | -15.80 |

| Irrigation Levels (%Etc) | ||||||

| 100 | 0.738 | 0.00 | 18.85 a | 0.00 | 25.54 d | 00.00 |

| 80 | 0.591 | 19.92 | 16.74 b | 11.19 | 28.34 c | 10.96 |

| 60 | 0.443 | 39.98 | 15.50 c | 17.77 | 34.98 b | 36.96 |

| 40 | 0.295 | 60.03 | 13.50 d | 28.38 | 45.72 a | 79.01 |

| Biochar | ||||||

| BC0% | ------- | ------ | 15.93 b | 0.00 | 33.46 b | 0.00 |

| BC5% | ------- | ------ | 16.36 a | -2.70 | 33.83 a | 1.11 |

| Parameters | Unit | Biochar | Soil | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface area | m2 g-1 | 237.80 | --- | |

| PH | - | 8.82 | 7.27 | |

| EC (1:10) | dS m-1 | 3.71 | 2.46 | |

| OM | % | 30.33 | Cations (meql-1) | |

| N | % | 0.24 | Ca+2 | 10.92 |

| P | % | 0.22 | Mg+2 | 2.25 |

| K | % | 0.88 | K+ | 5.10 |

| C | % | 60.00 | Na+ | 3.8 |

| H | % | 3.44 | Anions (meql-1) | |

| Ca | % | 5.63 | CO32- | 0.11 |

| C/N ratio | - | 250:1 | Cl- | 2.50 |

| Moisture | % | 3.53 | HCO3- | 0.83 |

| Ash | % | 25.70 | SAR | 2.02 |

| Resident material | % | 47.90 | --- | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).