Submitted:

26 May 2023

Posted:

29 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of Putative Wheat AGO, DCL, and RDR Genes

2.3. Phylogenetic Relationship Analysis and Classification of RNA Silencing Genes in Wheat

2.4. Prediction of Motifs and Gene Structure

2.5. Chromosomal Locations, Interaction Network and Orthologous Events Analysis

2.6. Identification of Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements

2.7. Prediction of miRNA Targeting Genes

2.8. RNA-seq Derived Gene Expression Profiling

2.9. Plant Material and Heat Stress Treatment

2.10. Expression Analysis of AGO, DCL, and RDR under Heat Stress

3. Results

3.1. Identification and In Silico Analysis of AGO, RDR, and DCL Genes in Wheat

3.2. Physio-Chemical Properties of TaAGO, TaDCL, and TaRDR Gene Families

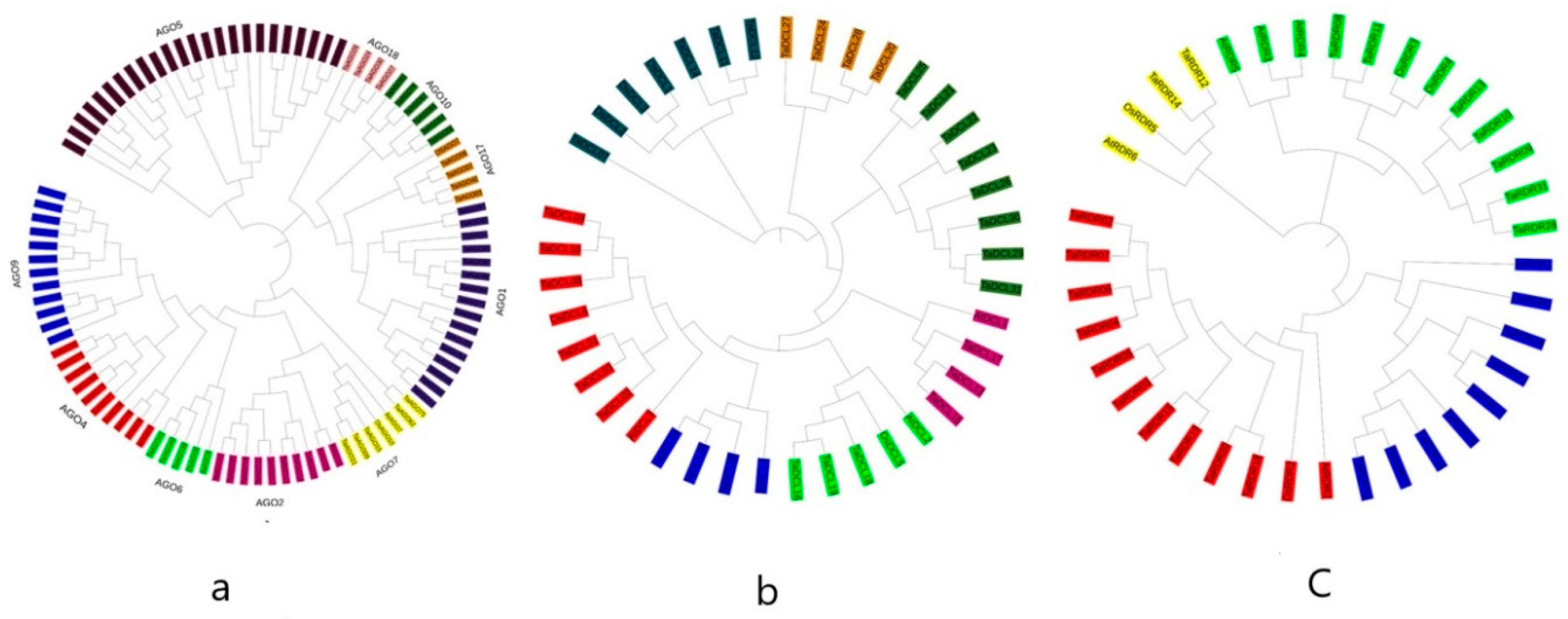

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of DCL, AGO, and RDR Proteins

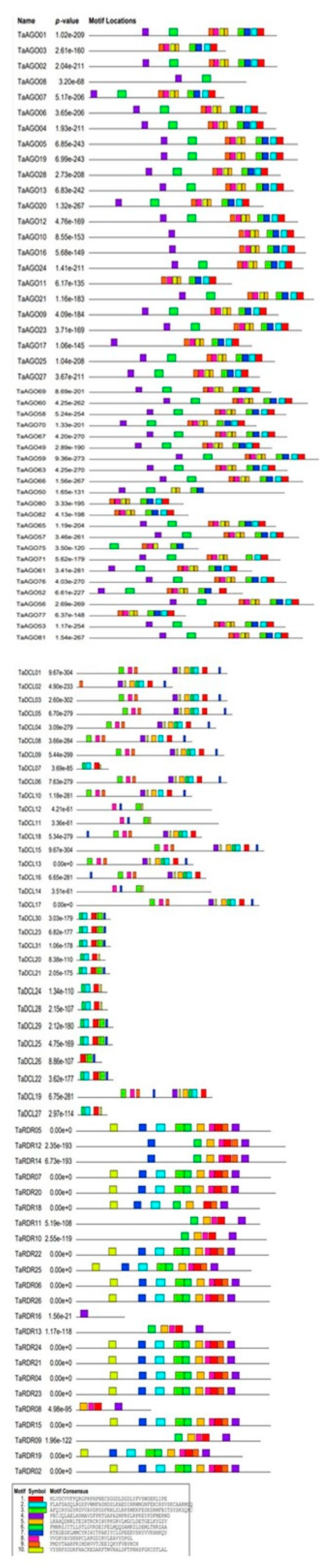

3.4. Conserved Domain and Motif Analysis of DCL, AGO and RDR Proteins in Wheat

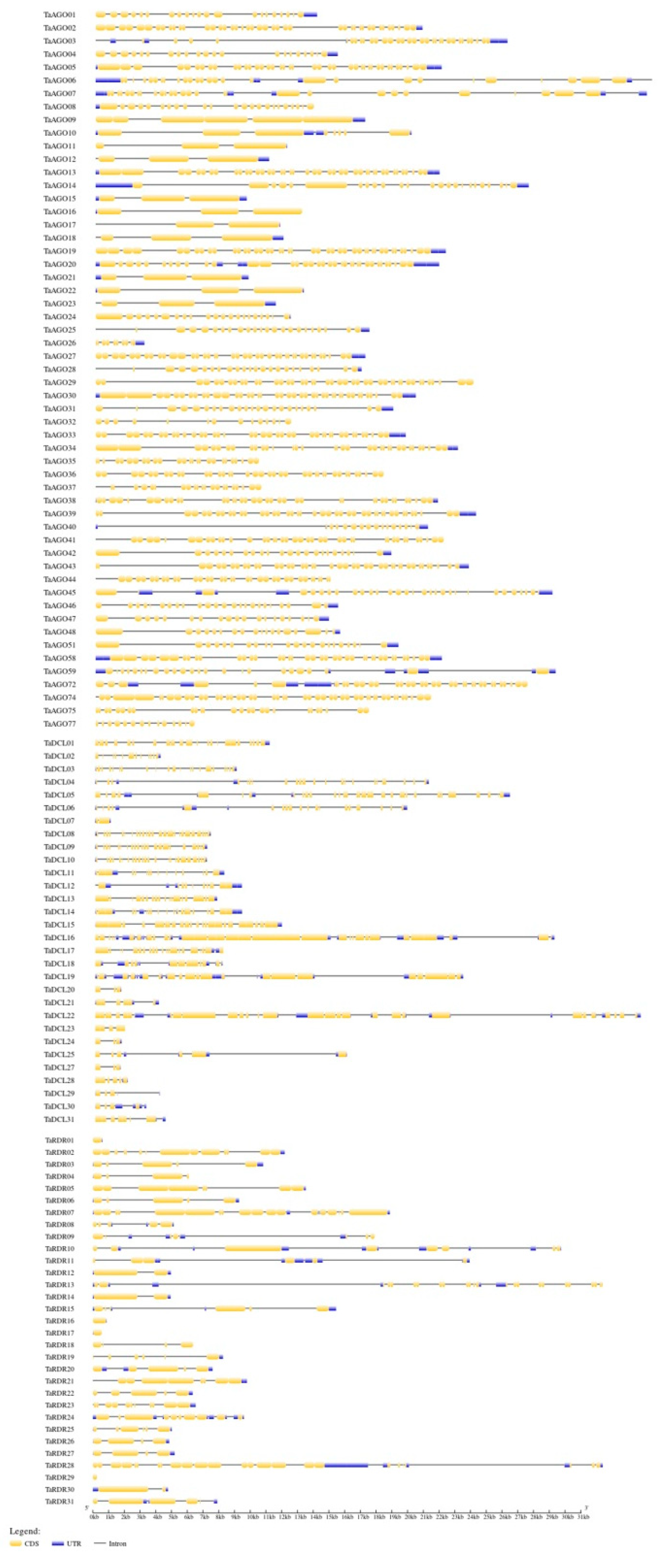

3.5. Gene Structure

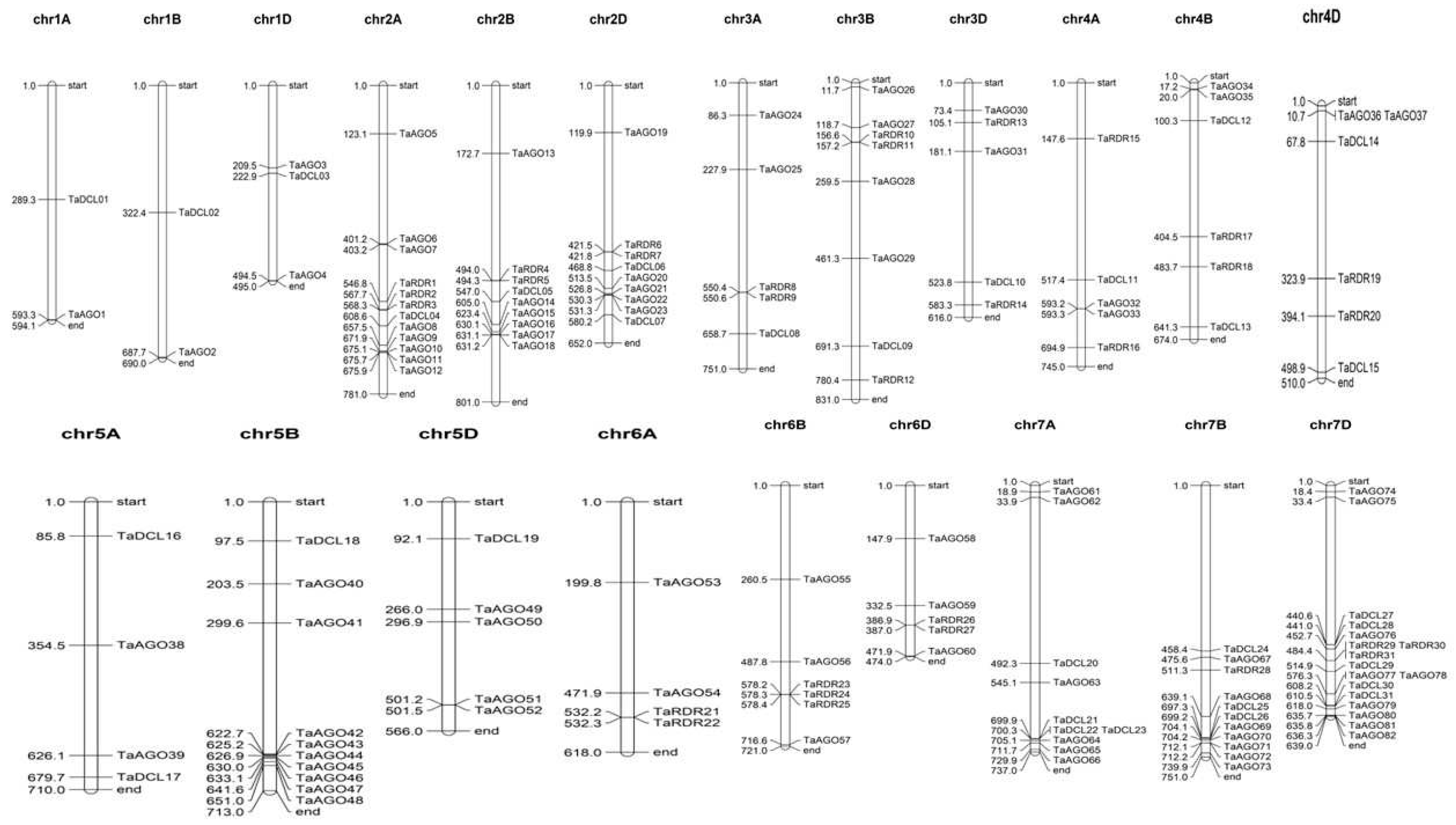

3.6. Chromosomal Location of Wheat DCL, RDR and AGO Genes

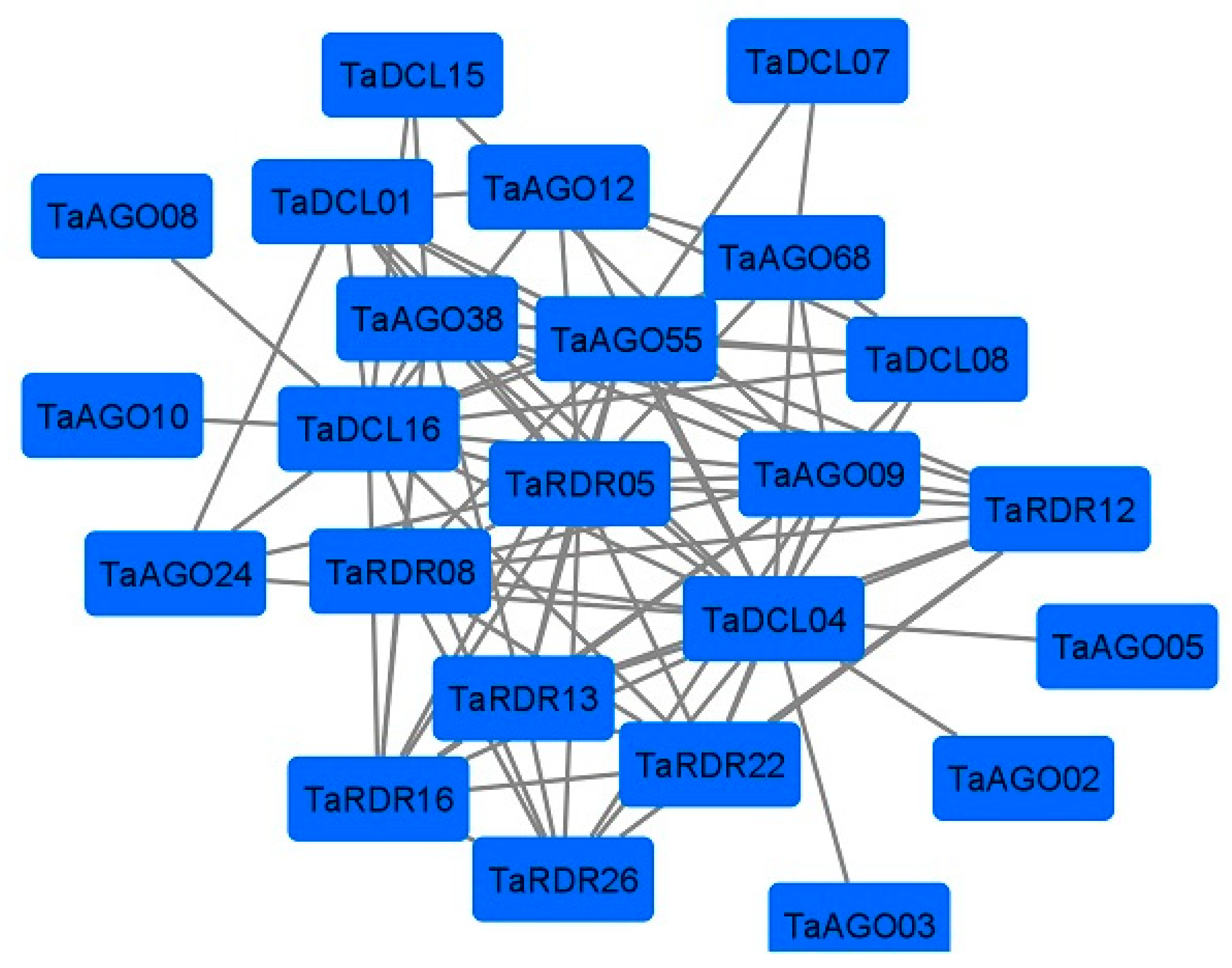

3.7. Protein-Interaction Network Analysis

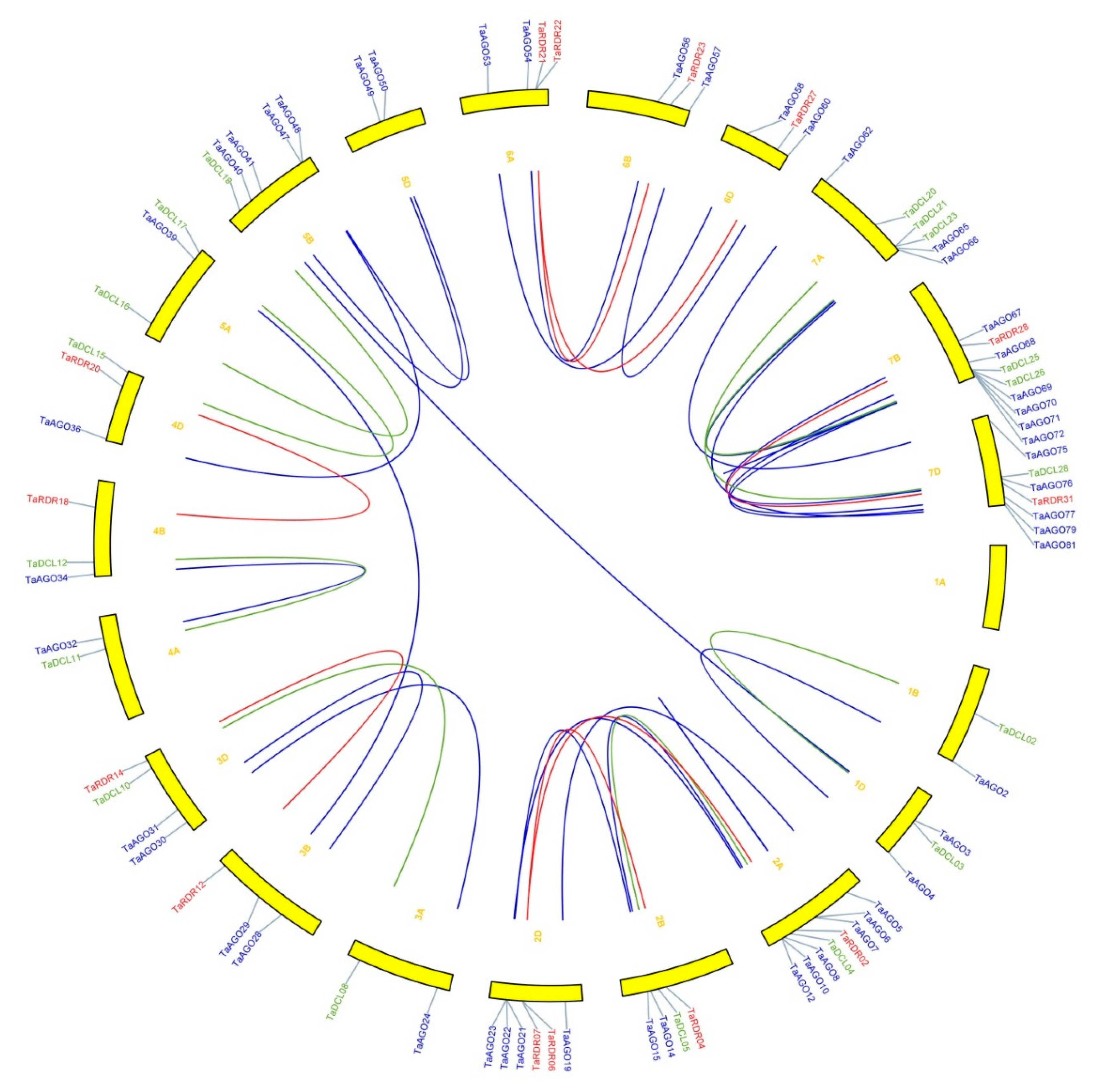

3.8. Identification of Orthologous and Paralogous RNA Silencing Genes

3.9. cis-acting Regulatory Elements

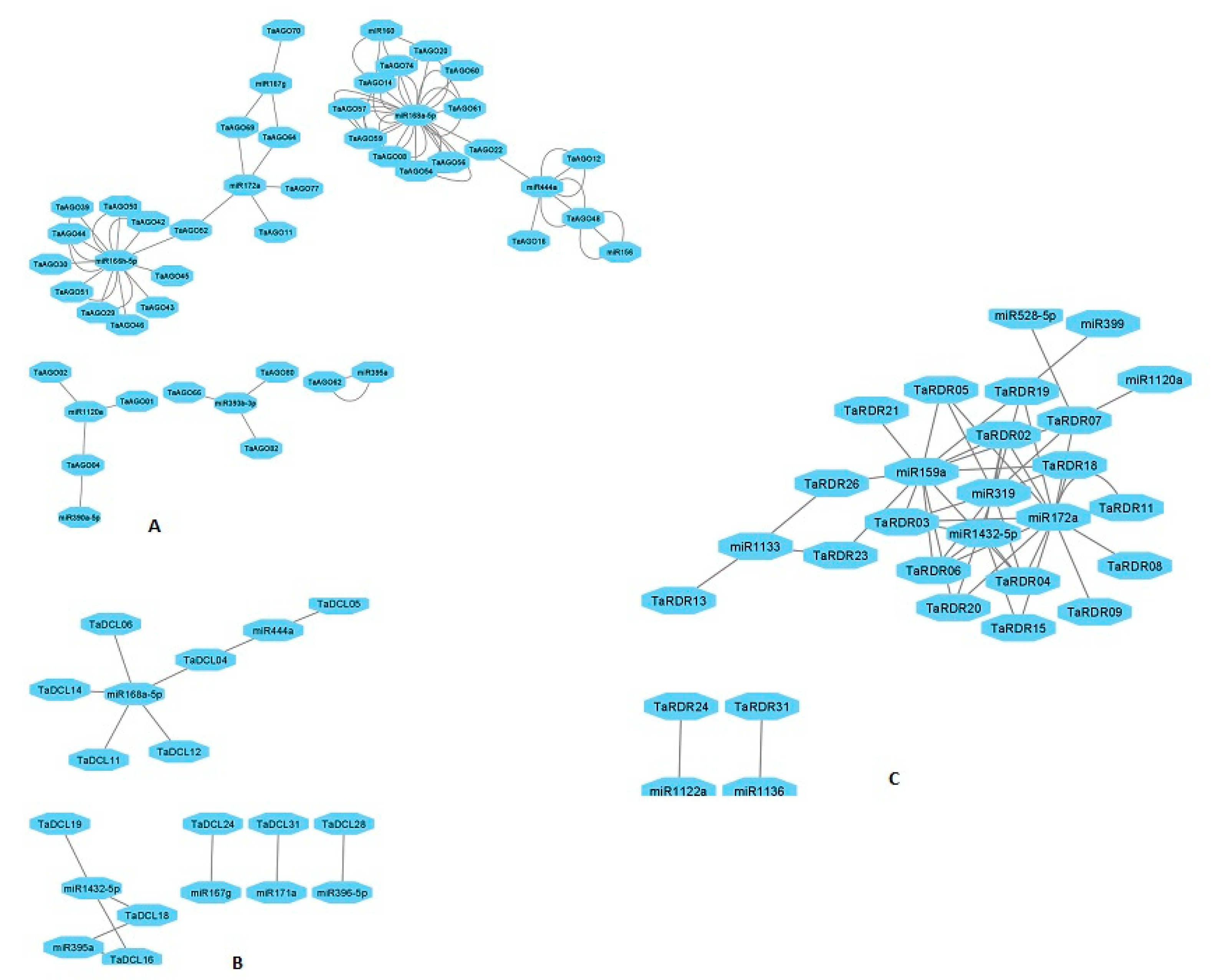

3.10. MicroRNA Targeting AGO, DCL and RDR Genes

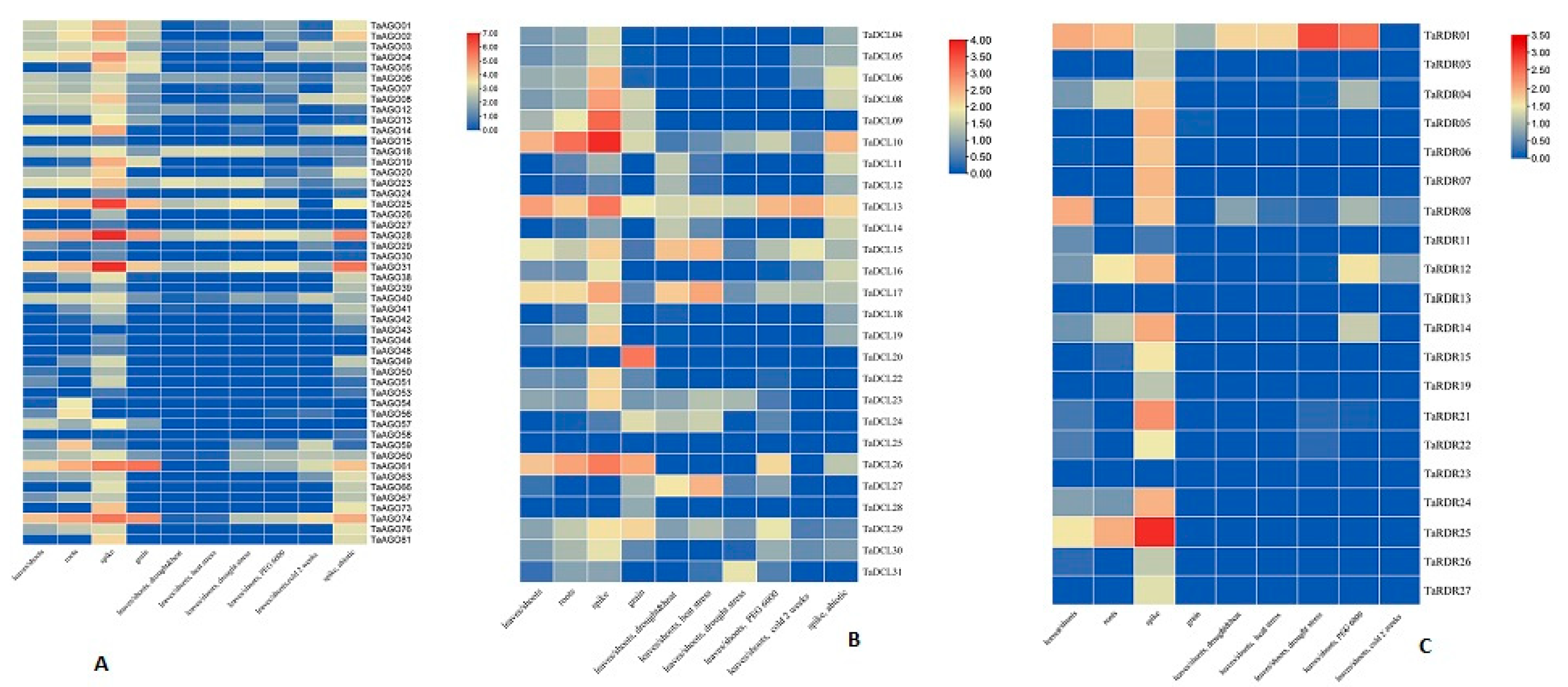

3.11. Expression Analysis of RNA Silencing Genes in T. aestivum

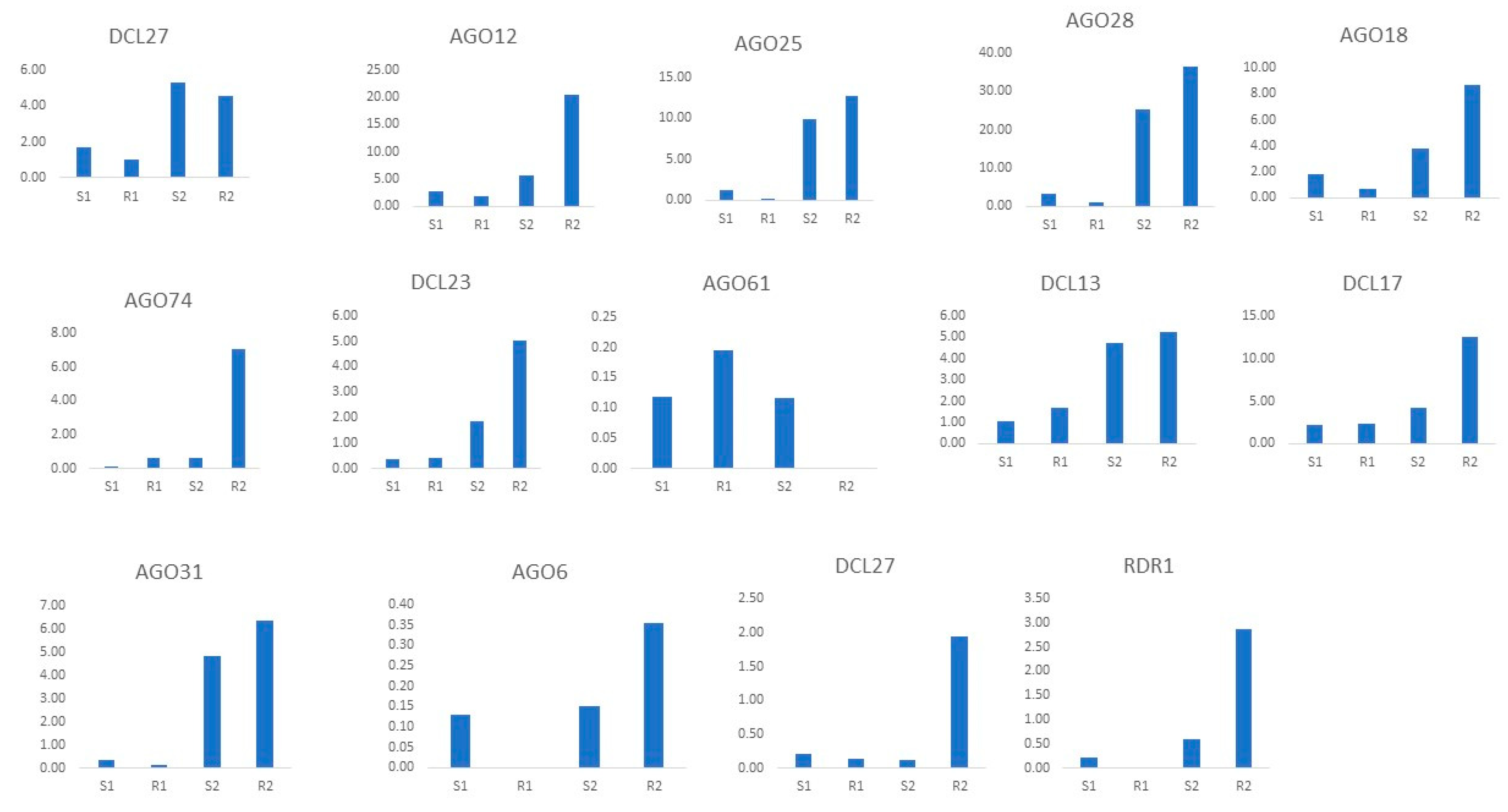

3.12. qRT-PCR Expression Analysis of TaAGO, TaDCL, and TaRDR Genes under Heat Stress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author’s Contribution

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

Competing Interests

References

- Gualtieri, C.; Leonetti, P.; Macovei, A. Plant MiRNA Cross-Kingdom Transfer Targeting Parasitic and Mutualistic Organisms as a Tool to Advance Modern Agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoloi, K.S.; Agarwala, N. MicroRNAs in Plant Insect Interaction and Insect Pest Control. Plant Gene 2021, 26, 100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Graham Ruby; Calvin H. Jan; David P. Bartel1 Intronic MicroRNA Precursors That Bypass Drosha Processing. Nature 2010, 136, 642–655. [CrossRef]

- Pratt, A.J.; MacRae, I.J. The RNA-Induced Silencing Complex: A Versatile Gene-Silencing Machine. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 17897–17901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaucheret, H. Plant ARGONAUTES. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.J.; Smith, S.K.; Hannon, G.J.; Joshua-Tor, L. Crystal Structure of Argonaute and Its Implications for RISC Slicer Activity. Science (80-. ). 2004, 305, 1434–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.S.; Yan, S.; Farooq, A.; Han, A.; Zeng, L.; Zhou, M.M. Structure and Conserved RNA Binding of the PAZ Domain. Nature 2003, 426, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.S.; Roe, S.M.; Barford, D. Crystal Structure of a PIWI Protein Suggests Mechanisms for SiRNA Recognition and Slicer Activity. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 4727–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.S.; Roe, S.M.; Barford, D. Europe PMC Funders Group Structural Insights into MRNA Recognition from a PIWI Domain – SiRNA Guide Complex. 2010, 434, 663–666. [CrossRef]

- Mallory, A.; Vaucheret, H. Form, Function, and Regulation of ARGONAUTE Proteins. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 3879–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yang, H.; Zou, C.; Li, W.X.; Xu, Y.; Xie, C. Identification and Functional Characterization of the AGO1 Ortholog in Maize. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2016, 58, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbione, A.; Daurelio, L.; Vegetti, A.; Talón, M.; Tadeo, F.; Dotto, M. Genome-Wide Analysis of AGO, DCL and RDR Gene Families Reveals RNA-Directed DNA Methylation Is Involved in Fruit Abscission in Citrus Sinensis. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, D.L.; Meng, J.Y.; Ren, X.Y.; Yue, J.J.; Fu, H.Y.; Huang, M.T.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Gao, S.J. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of DCL, AGO and RDR Gene Families in Saccharum Spontaneum. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margis, R.; Fusaro, A.F.; Smith, N.A.; Curtin, S.J.; Watson, J.M.; Finnegan, E.J.; Waterhouse, P.M. The Evolution and Diversification of Dicers in Plants. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 2442–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prospects, C.; Situation, F. Crop Prospects and Food Situation #2, July 2022; 2022; ISBN 9789251365960. 20 July.

- Ceccon, E. Plant Productivity and Environment. Science (80-. ). 1982, 218, 443–448. [Google Scholar]

- Guttikonda, S.K.; Valliyodan, B.; Neelakandan, A.K.; Tran, L.S.P.; Kumar, R.; Quach, T.N.; Voothuluru, P.; Gutierrez-Gonzalez, J.J.; Aldrich, D.L.; Pallardy, S.G.; et al. Overexpression of AtDREB1D Transcription Factor Improves Drought Tolerance in Soybean. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 7995–8008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, R.D.; Coggill, P.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; Eddy, S.R.; Mistry, J.; Mitchell, A.L.; Potter, S.C.; Punta, M.; Qureshi, M.; Sangrador-Vegas, A.; et al. The Pfam Protein Families Database: Towards a More Sustainable Future. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D279–D285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Lu, S.; Anderson, J.B.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; DeWeese-Scott, C.; Fong, J.H.; Geer, L.Y.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; et al. CDD: A Conserved Domain Database for the Functional Annotation of Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, S.C.; Luciani, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Park, Y.; Lopez, R.; Finn, R.D. HMMER Web Server: 2018 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W200–W204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.Y.; Xu, Y.P.; Li, W.; Li, S.S.; Rahman, H.; Cai, X.Z. Genome-Wide Identification of Dicer-like, Argonaute, and RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Gene Families in Brassica Species and Functional Analyses of Their Arabidopsis Homologs in Resistance to Sclerotinia Sclerotiorum. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorrips, R.E. Mapchart: Software for the Graphical Presentation of Linkage Maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 2002, 93, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Franceschini, A.; Wyder, S.; Forslund, K.; Heller, D.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Roth, A.; Santos, A.; Tsafou, K.P.; et al. STRING V10: Protein-Protein Interaction Networks, Integrated over the Tree of Life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D447–D452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul Shannon, 1; Andrew Markiel, 1; Owen Ozier, 2 Nitin S. Baliga, 1 Jonathan T. Wang, 2 Daniel Ramage, 2; Nada Amin, 2; Benno Schwikowski, 1, 5 and Trey Ideker2, 3, 4, 5; 山本隆久; 豊田直平; 深瀬吉邦; 大森敏行 Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models. Genome Res. 1971, 13, 426. [CrossRef]

- Goodstein, D.M.; Shu, S.; Howson, R.; Neupane, R.; Hayes, R.D.; Fazo, J.; Mitros, T.; Dirks, W.; Hellsten, U.; Putnam, N.; et al. Phytozome: A Comparative Platform for Green Plant Genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metsalu, T.; Vilo, J. ClustVis: A Web Tool for Visualizing Clustering of Multivariate Data Using Principal Component Analysis and Heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W566–W570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthusamy, S.K.; Dalal, M.; Chinnusamy, V.; Bansal, K.C. Differential Regulation of Genes Coding for Organelle and Cytosolic ClpATPases under Biotic and Abiotic Stresses in Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bologna, N.G.; Voinnet, O. The Diversity, Biogenesis, and Activities of Endogenous Silencing Small RNAs in Arabidopsis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014, 65, 473–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akond, Z.; Rahman, H.; Ahsan, M.A.; Mosharaf, M.P.; Alam, M.; Mollah, M.N.H. Comprehensive in Silico Analysis of RNA Silencing-Related Genes and Their Regulatory Elements in Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Wang, L.M.; Zhao, L.Z.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.X. Genome-Wide Identification and Evolutionary Analysis of Argonaute Genes in Hexaploid Bread Wheat. Biomed Res. Int. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.Y.W.; Valli, A.; Deery, M.J.; Navarro, F.J.; Brown, K.; Hnatova, S.; Howard, J.; Molnar, A.; Baulcombe, D.C. Distinct Roles of Argonaute in the Green Alga Chlamydomonas Reveal Evolutionary Conserved Mode of MiRNA-Mediated Gene Expression. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, F.F.; Hossen, M.I.; Sarkar, M.A.R.; Konak, J.N.; Zohra, F.T.; Shoyeb, M.; Mondal, S. Genome-Wide Identification of DCL, AGO and RDR Gene Families and Their Associated Functional Regulatory Elements Analyses in Banana (Musa Acuminata); 2021; Vol. 16; ISBN 1111111111.

- Hamar, E.; Szaker, H.M.; Kis, A.; Dalmadi, A.; Miloro, F.; Szittya, G.; Taller, J.; Gyula, P.; Csorba, T.; Havelda, Z. Genome-Wide Identification of RNA Silencing-Related Genes and Their Expressional Analysis in Response to Heat Stress in Barley (Hordeum Vulgare L.). Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnatreya, D.B.; Baruah, P.M.; Dowarah, B.; Chowrasia, S.; Mondal, T.K.; Agarwala, N. Genome-Wide Identification, Evolutionary Relationship and Expression Analysis of AGO, DCL and RDR Family Genes in Tea. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Qi, Y. Rnai in Plants: An Argonaute-Centered View. Plant Cell 2015, 28, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, J.J.W.; Lewsey, M.G.; Patel, K.; Westwood, J.; Heimstädt, S.; Carr, J.P.; Baulcombe, D.C. An Antiviral Defense Role of AGO2 in Plants. PLoS One 2011, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, H.; Gao, S.; Wang, W.C.; Katiyar-Agarwal, S.; Huang, H. Da; Raikhel, N.; Jin, H. Arabidopsis Argonaute 2 Regulates Innate Immunity via MiRNA393*-Mediated Silencing of a Golgi-Localized SNARE Gene, MEMB12. Mol. Cell 2011, 42, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Ba, Z.; Gao, M.; Wu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Amiard, S.; White, C.I.; Danielsen, J.M.R.; Yang, Y.G.; Qi, Y. A Role for Small RNAs in DNA Double-Strand Break Repair. Cell 2012, 149, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, T.A.; Howell, M.D.; Cuperus, J.T.; Li, D.; Hansen, J.E.; Alexander, A.L.; Chapman, E.J.; Fahlgren, N.; Allen, E.; Carrington, J.C. Specificity of ARGONAUTE7-MiR390 Interaction and Dual Functionality in TAS3 Trans-Acting SiRNA Formation. Cell 2008, 133, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, R.N.; Wiley, D.; Sarkar, A.; Springer, N.; Timmermans, M.C.P.; Scanlon, M.J. Ragged Seedling2 Encodes an ARGONAUTE7-like Protein Required for Mediolateral Expansion, but Not Dorsiventrality, of Maize Leaves. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 1441–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Zhang, H.; Tang, K.; Zhu, X.; Qian, W.; Hou, Y.; Wang, B.; Lang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Specific but Interdependent Functions for A Rabidopsis AGO 4 and AGO 6 in RNA -directed DNA Methylation. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durán-Figueroa, N.; Vielle-Calzada, J.P. ARGONAUTE9-Dependent Silencing of Transposable Elements in Pericentromeric Regions of Arabidopsis. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 1476–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havecker, E.R.; Wallbridge, L.M.; Hardcastle, T.J.; Bush, M.S.; Kelly, K.A.; Dunn, R.M.; Schwach, F.; Doonan, J.H.; Baulcombe, D.C. The Arabidopsis RNA-Directed DNA Methylation Argonautes Functionally Diverge Based on Their Expression and Interaction with Target Loci. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, F.; Martienssen, R.A. The Expanding World of Small RNAs in Plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Mao, L.; Qi, Y. Roles of DICER-LIKE and ARGONAUTE Proteins in TAS-Derived Small Interfering RNA-Triggered DNA Methylation. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matzke, M.A.; Mosher, R.A. RNA-Directed DNA Methylation: An Epigenetic Pathway of Increasing Complexity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Goel, S.; Meeley, R.B.; Dantec, C.; Parrinello, H.; Michaud, C.; Leblanc, O.; Grimanelli, D. Production of Viable Gametes without Meiosis in Maize Deficient for an ARGONAUTE Protein. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Ye, R.; Ji, Y.; Zhao, S.; Ji, S.; Liu, R.; Xu, L.; et al. Viral-Inducible Argonaute18 Confers Broad-Spectrum Virus Resistance in Rice by Sequestering a Host MicroRNA. Elife 2015, 2015, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Zhang, H.; Arikit, S.; Huang, K.; Nan, G.L.; Walbot, V.; Meyers, B.C. Spatiotemporally Dynamic, Cell-Type-Dependent Premeiotic and Meiotic PhasiRNAs in Maize Anthers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 3146–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holoch, D.; Moazed, D. RNA-Mediated Epigenetic Regulation of Gene Expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branscheid, A.; Marchais, A.; Schott, G.; Lange, H.; Gagliardi, D.; Andersen, S.U.; Voinnet, O.; Brodersen, P. SKI2 Mediates Degradation of RISC 5′-Cleavage Fragments and Prevents Secondary SiRNA Production from MiRNA Targets in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 10975–10988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, A.; Carrington, J.C. Antiviral Roles of Plant ARGONAUTES. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 27, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, P.; Zhai, J.; Zhou, M.; Ma, L.; Liu, B.; Jeong, D.H.; Nakano, M.; Cao, S.; Liu, C.; et al. Roles of DCL4 and DCL3b in Rice Phased Small RNA Biogenesis. Plant J. 2012, 69, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.; Zhang, H.; Hammond, R.; Huang, K.; Meyers, B.C.; Walbot, V. Dicer-like 5 Deficiency Confers Temperature-Sensitive Male Sterility in Maize. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, C.T.; Stephens, J.; Hornyik, C.; Shaw, J.; Collinge, D.B.; Lacomme, C.; Albrechtsen, M. Identification and Characterization of Barley RNA-Directed RNA Polymerases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gene Regul. Mech. 2009, 1789, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleman, M.; Sidorenko, L.; McGinnis, K.; Seshadri, V.; Dorweiler, J.E.; White, J.; Sikkink, K.; Chandler, V.L. An RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Is Required for Paramutation in Maize. Nature 2006, 442, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaki, H.; Itoh, J.I.; Hayashi, K.; Hibara, K.I.; Satoh-Nagasawa, N.; Nosaka, M.; Mukouhata, M.; Ashikari, M.; Kitano, H.; Matsuoka, M.; et al. The Small Interfering RNA Production Pathway Is Required for Shoot Meristem Initiation in Rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 14867–14871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jiao, X.; Kong, X.; Hamera, S.; Wu, Y.; Chen, X.; Fang, R.; Yan, Y. A Signaling Cascade from MiR444 to RDR1 in Rice Antiviral RNA Silencing Pathway. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 2365–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakasugi, K.; Crowhurst, R.N.; Bally, J.; Wood, C.C.; Hellens, R.P.; Waterhouse, P.M. De Novo Transcriptome Sequence Assembly and Analysis of RNA Silencing Genes of Nicotiana Benthamiana. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaucheret, H.; Vazquez, F.; Crété, P.; Bartel, D.P. The Action of ARGONAUTE1 in the MiRNA Pathway and Its Regulation by the MiRNA Pathway Are Crucial for Plant Development. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Várallyay, É.; Válóczi, A.; Ágyi, Á.; Burgyán, J.; Havelda, Z. Plant Virus-Mediated Induction of MiR168 Is Associated with Repression of ARGONAUTE1 Accumulation. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 3507–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, S.; Shivaprasad, P. V. Diversity, Expression and MRNA Targeting Abilities of Argonaute-Targeting MiRNAs among Selected Vascular Plants. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozhuner, E.; Eldem, V.; Ipek, A.; Okay, S.; Sakcali, S.; Zhang, B.; Boke, H.; Unver, T. Boron Stress Responsive MicroRNAs and Their Targets in Barley. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Hernández, E.C.; Alejandri-Ramírez, N.D.; Juárez-González, V.T.; Dinkova, T.D. Maize MiRNA and Target Regulation in Response to Hormone Depletion and Light Exposure during Somatic Embryogenesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmadi, A.; Gyula, P.; Balint, J.; Szittya, G.; Havelda, Z. AGO-Unbound Cytosolic Pool of Mature MiRNAs in Plant Cells Reveals a Novel Regulatory Step at AGO1 Loading. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 9803–9817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.S.; Kuo, C.C.; Yang, I.C.; Tsai, W.A.; Shen, Y.H.; Lin, C.C.; Liang, Y.C.; Li, Y.C.; Kuo, Y.W.; King, Y.C.; et al. MicroRNA160 Modulates Plant Development and Heat Shock Protein Gene Expression to Mediate Heat Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Yang, G.S.; Chen, W.T.; Mao, Z.C.; Kang, H.X.; Chen, G.H.; Yang, Y.H.; Xie, B.Y. Genome-Wide Identification of Dicer-like, Argonaute and RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Gene Families and Their Expression Analyses in Response to Viral Infection and Abiotic Stresses in Solanum Lycopersicum. Gene 2012, 501, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stief, A.; Altmann, S.; Hoffmann, K.; Pant, B.D.; Scheible, W.R.; Bäurle, I. Arabidopsis MiR156 Regulates Tolerance to Recurring Environmental Stress through SPL Transcription Factors. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1792–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhonga, S.H.; Liu, J.Z.; Jin, H.; Lin, L.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, Y.X.; Wang, Z.Y.; Huang, H.; Qi, Y.J.; et al. Warm Temperatures Induce Transgenerational Epigenetic Release of RNA Silencing by Inhibiting SiRNA Biogenesis in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 9171–9176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).