Submitted:

24 May 2023

Posted:

26 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study area

2.2 Data

2.3 Inversion frequency

- A day comprises the nighttime hourly observations between 00 and 06 UTC, all inclusive.

- At a given hour, an inversion is detected if the difference of the 2 m temperature between stations A and B is positive, with A having a higher altitude than B.

- A dry day is one in which the hourly precipitation in all the surface weather stations in the Lousã/Seia region during nighttime is lower or equal to 0.2 mm/1h.

2.4 Downslope windstorms

- 2 m temperature must be equal or increase when going from A to C.

- 2 m relative humidity must be equal or lower when going from A to C.

- Wind direction is from the south, southeast or east.

- 10 m wind gust must be above a given threshold. The threshold was set after a thorough review of the observed data and is site dependent. After reviewing the observed data, the values used are 10 m/s in Lousã and Seia and 8 m/s in Candal and provide a balanced cut-off to identify events on which downslope wind were strong.

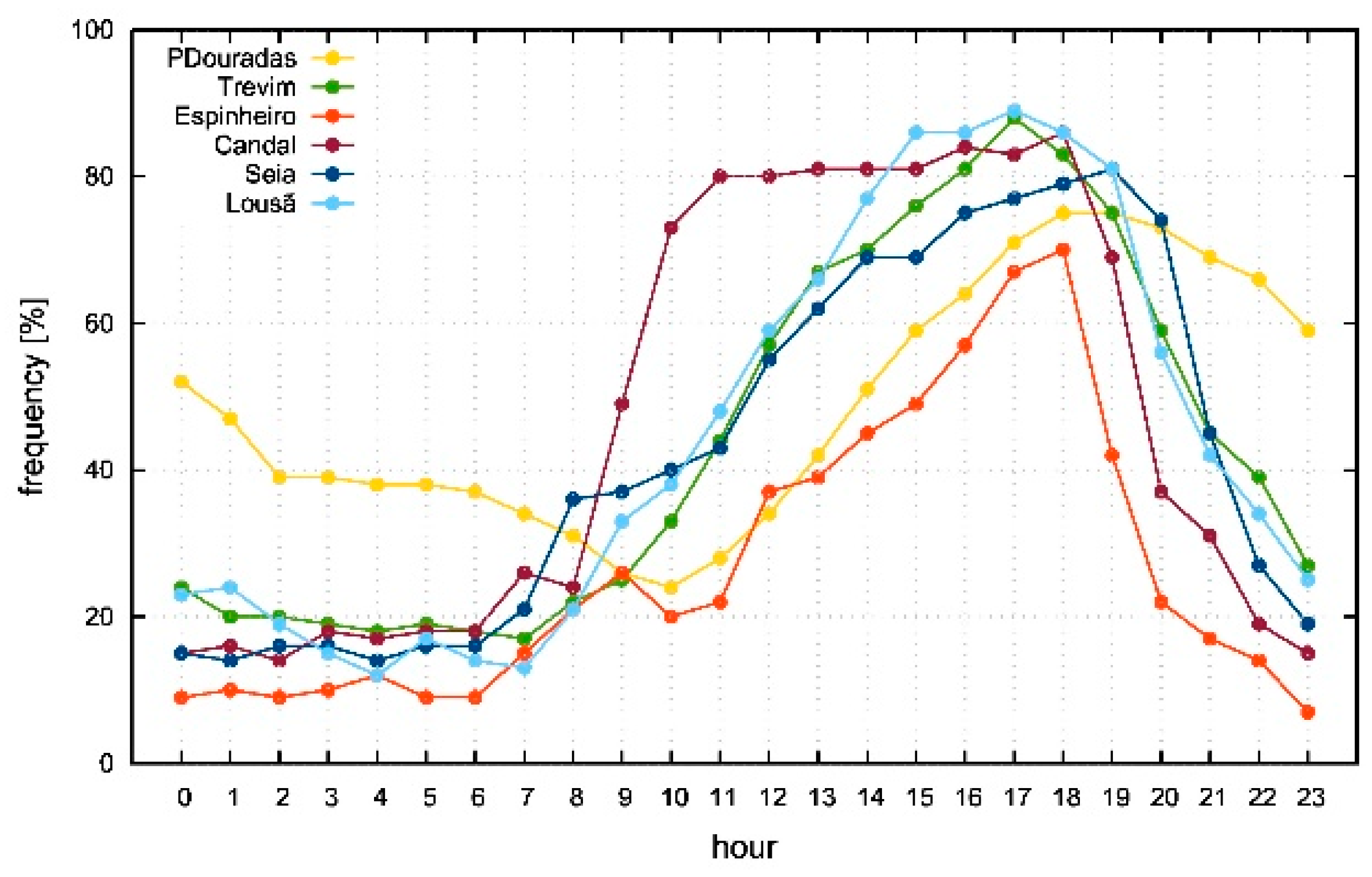

2.5 Daily cycle

3. Results

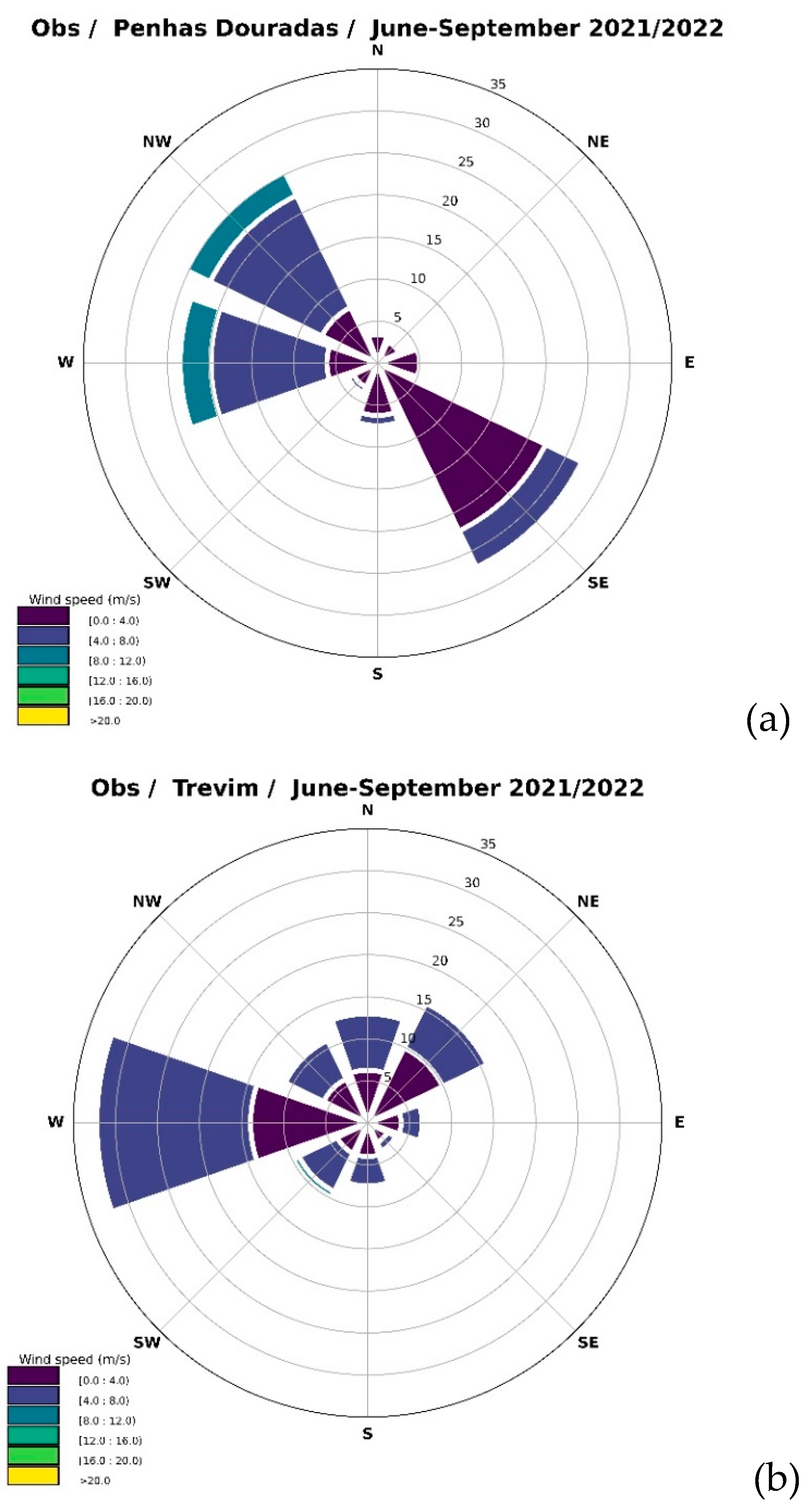

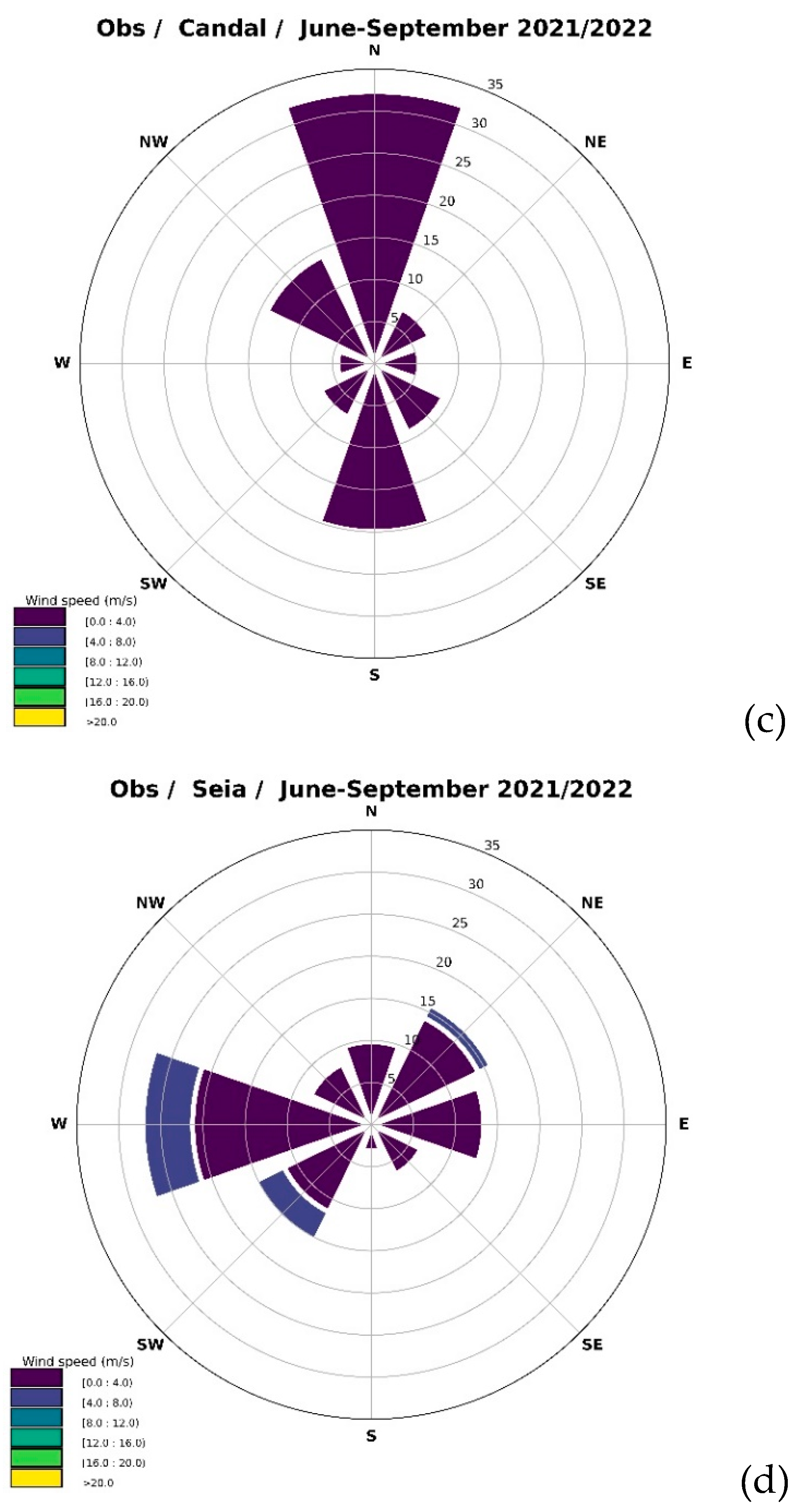

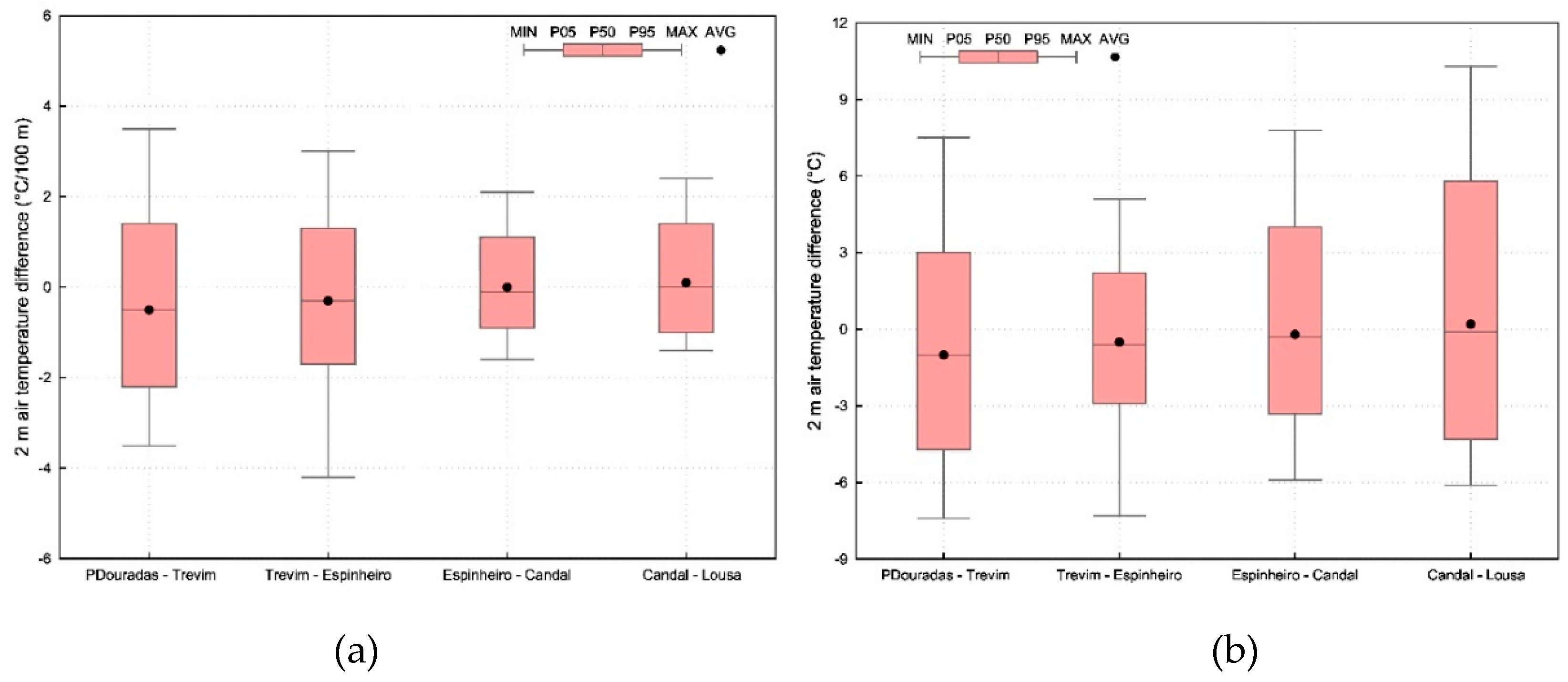

3.1 Seasonal Statistics

- a)

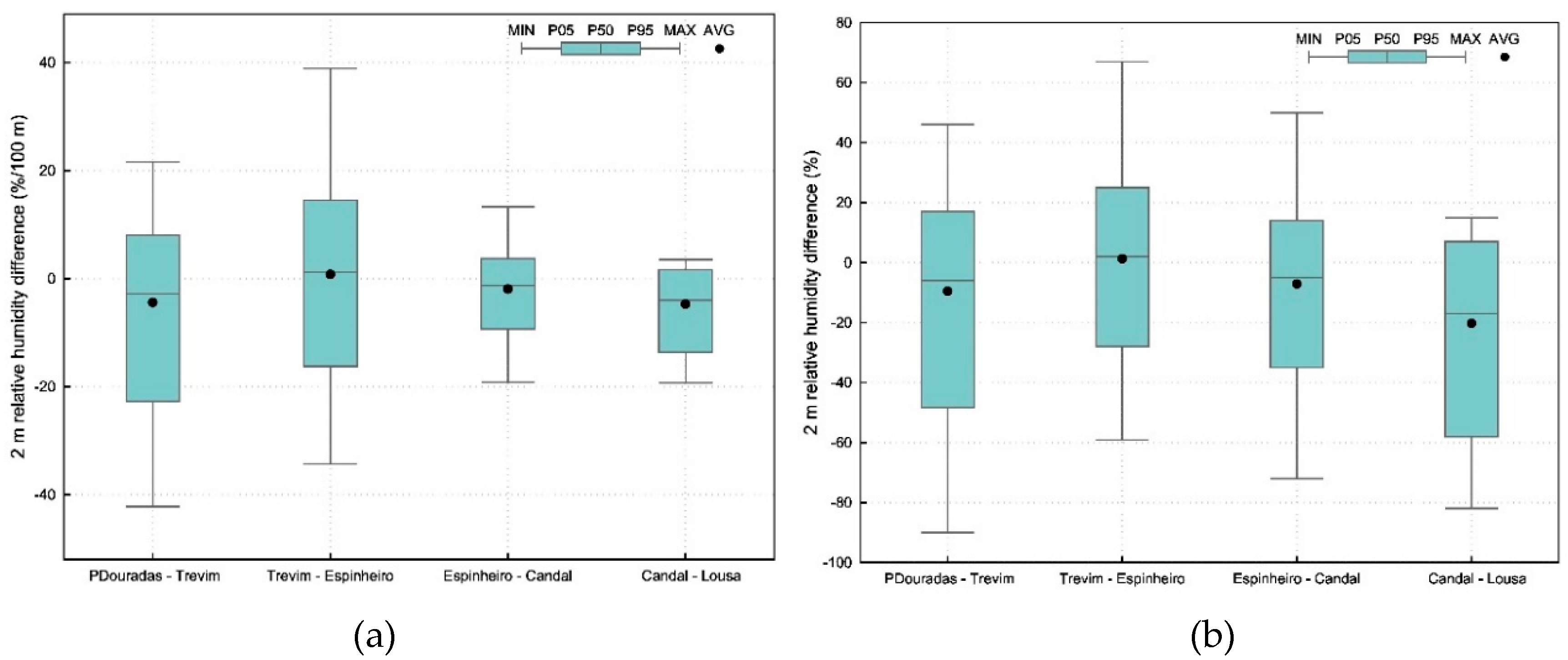

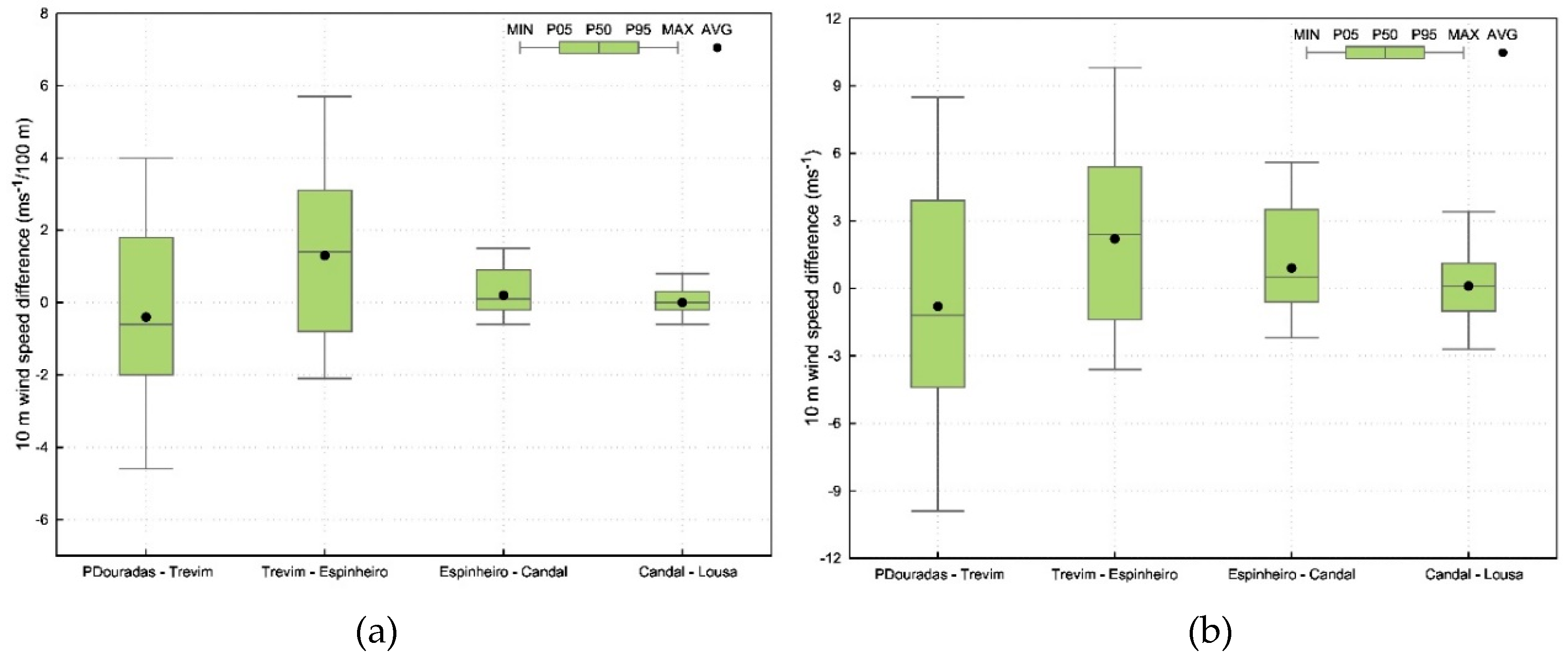

- Between Penhas Douradas (1380 m asl) and Trevim (1167 m asl) there were seven events with a 2 m temperature difference equal or above 5°C. These events occurred with a west/northwesterly flow in both AWS and positive differences in the 10 m wind speed. In these periods, the values of 2 m relative humidity in Penhas Douradas were frequently 40% lower than in Trevim and the extreme minimum differences reached -80%.

- b)

- Between Penhas Douradas and Trevim there were 16 events with a 2 m temperature difference equal to or below -5°C. In these periods the wind direction was mainly from the east/southeast aloft and east/northeast in Trevim. The difference in the 10 m wind speed was usually negative, which implies higher values at the lower elevation (Trevim). Given the orientation of the mountain ridge, a strong interaction between the flow and the topography is likely to play a relevant role in such conditions.

- c)

- While the data between Trevim (1167 m asl) and Espinheiro (995 m asl) shows a large dispersion, negative differences in the 10 m wind speed only occurred with an east/northeast in Trevim and a southeasterly wind in Espinheiro. The biggest differences in 2 m temperature occurred with south/southwesterly or east/northeasterly winds at both sites. In the latter case large negative differences in the 2 m relative humidity were also observed.

- d)

- Despite the large dispersion, the data from Espinheiro (995 m asl) and Candal (621 m asl) shows that positive differences in the 2 m temperature and large negative differences in the 2 m relative humidity (over -40%) occurred with an east/southeasterly flow at the site aloft.

- e)

- Large positive differences in the 2 m temperature between Candal (621 m asl) and Lousã (195 m asl) and large negative differences in the 2 m relative humidity (lower or equal to -40%) occurred with east/southeasterly winds in Candal. In these periods the wind direction was from the west/northwest in Lousã. Negative differences in the 2 m temperature were observed with northwesterly winds in Candal.

- f)

- In Candal the 10 m wind speed may be higher than in Lousã and this was observed either from the W/NW or E/SE directions, which may suggest channelling in the narrow valley. On some occasions the 10 m wind speed is below 2 m/s in both Candal and Lousã, but the 10 m wind gusts in Candal may exceed by 6 m/s the values observed in the valley. In these events the wind direction is from the E/SE in Candal, which suggest that strong downslope winds do not always reach the valley.

- g)

- Differences in the 2 m relative humidity larger than -60% were observed in 15 events in Candal/Lousã and the frequency of temperature inversions was 63%. In the Seia region, the frequency of temperature inversions between the valley station and Espinheiro was higher, at 88%. Both results highlight the large vertical variability between valley areas and the medium slope.

- h)

- The frequency of temperature inversions in the upper slope was 50% when using data from Penhas Douradas and Trevim. If a deeper layer is chosen (Penhas Douradas-Espinheiro), the frequency drops to 23%. Finally, the frequency of temperature inversion in all the layers between Penhas Douradas and Candal is lower, at 12%.

- i)

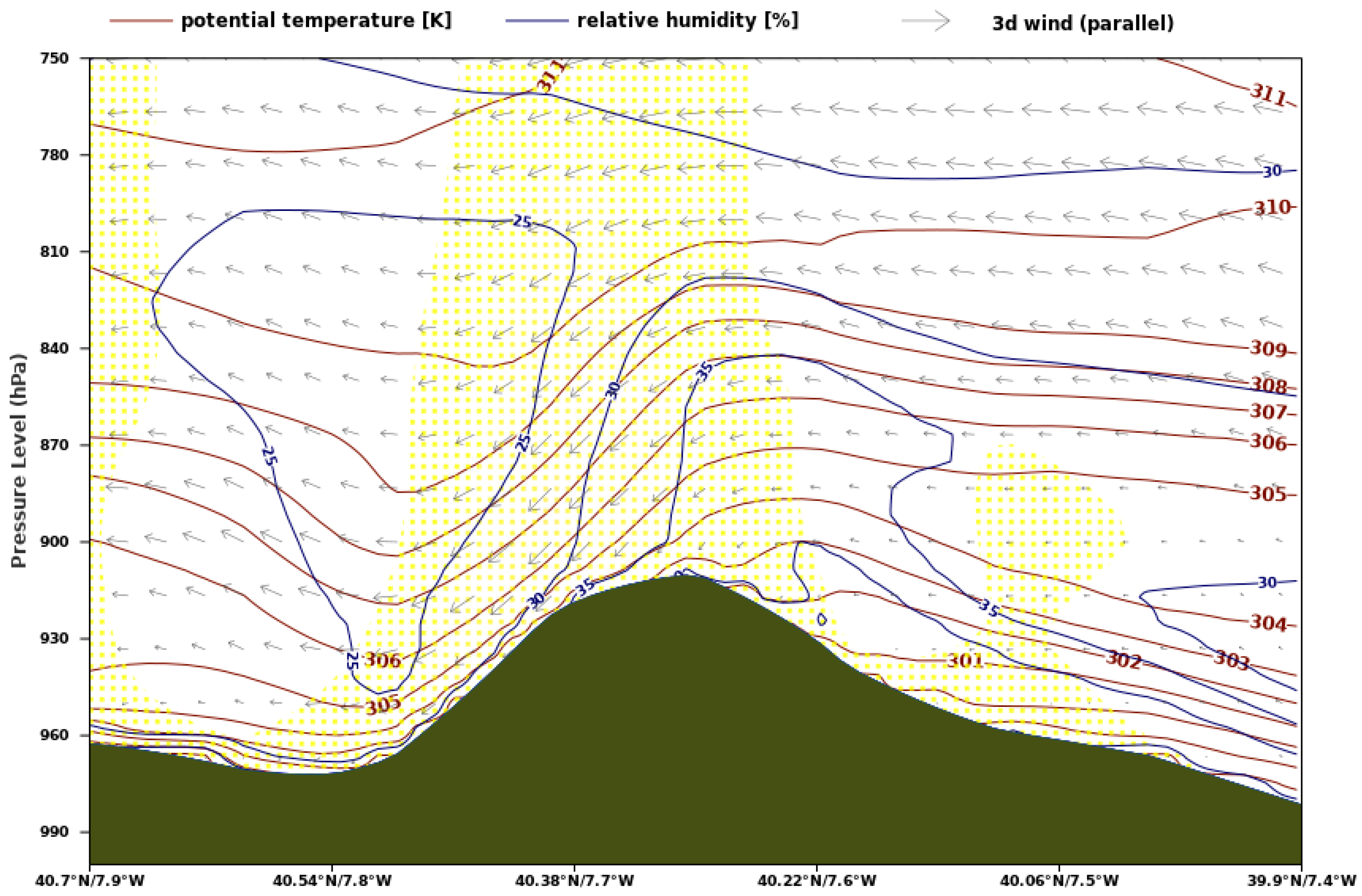

- Large negative differences in the 2 m relative humidity (more than -40%) were observed in all the three layers studied between Penhas Douradas and Candal. When these large differences were observed in the two upper layers (Penhas Douradas/Trevim and Trevim/Espinheiro) a strong vertical gradient of the potential temperature was detected in the 880-940 hPa layer. When the large negative difference in 2 m relative humidity was observed between Espinheiro and Candal, the strong vertical gradient was usually around 930-960 hPa. When dry air is detected as low as in Candal, which is taken by considering the threshold of 2°C in the 2 m dew point temperature at this site, an inversion was present at levels below 960 hPa level. Model data tends to overestimate these low values of 2 m dew point temperature in Candal (not shown).

4. Events with large vertical variability

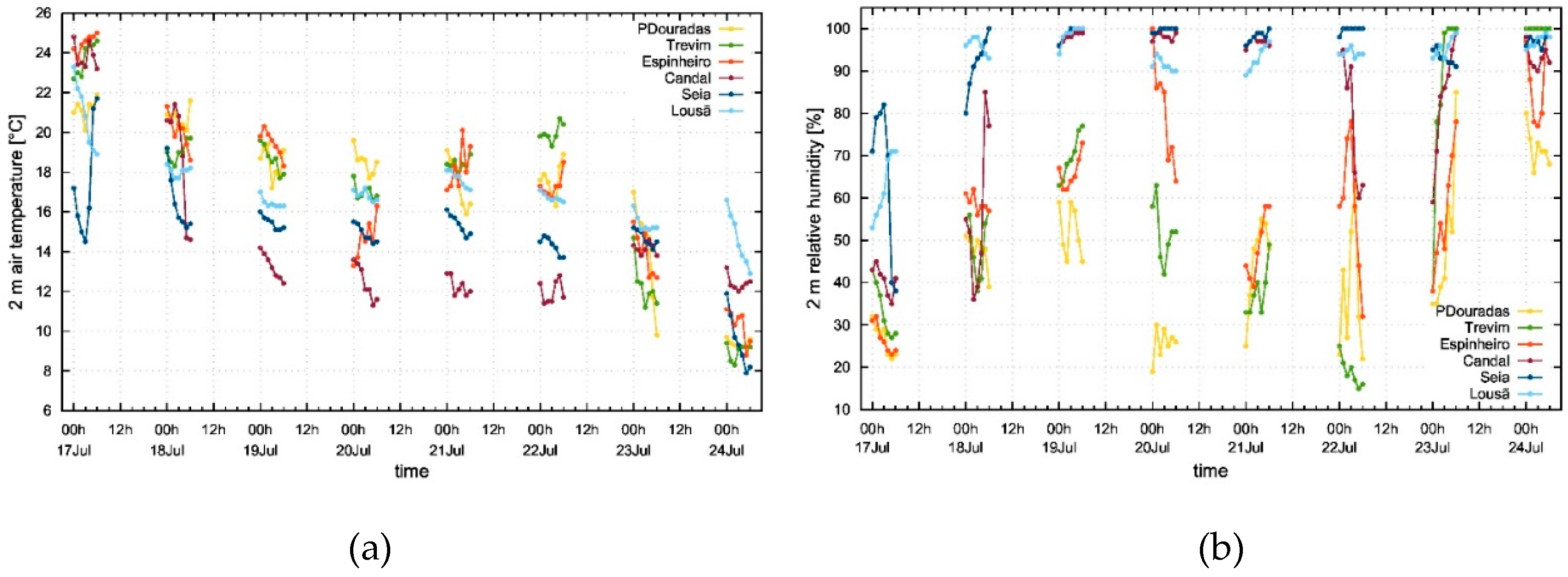

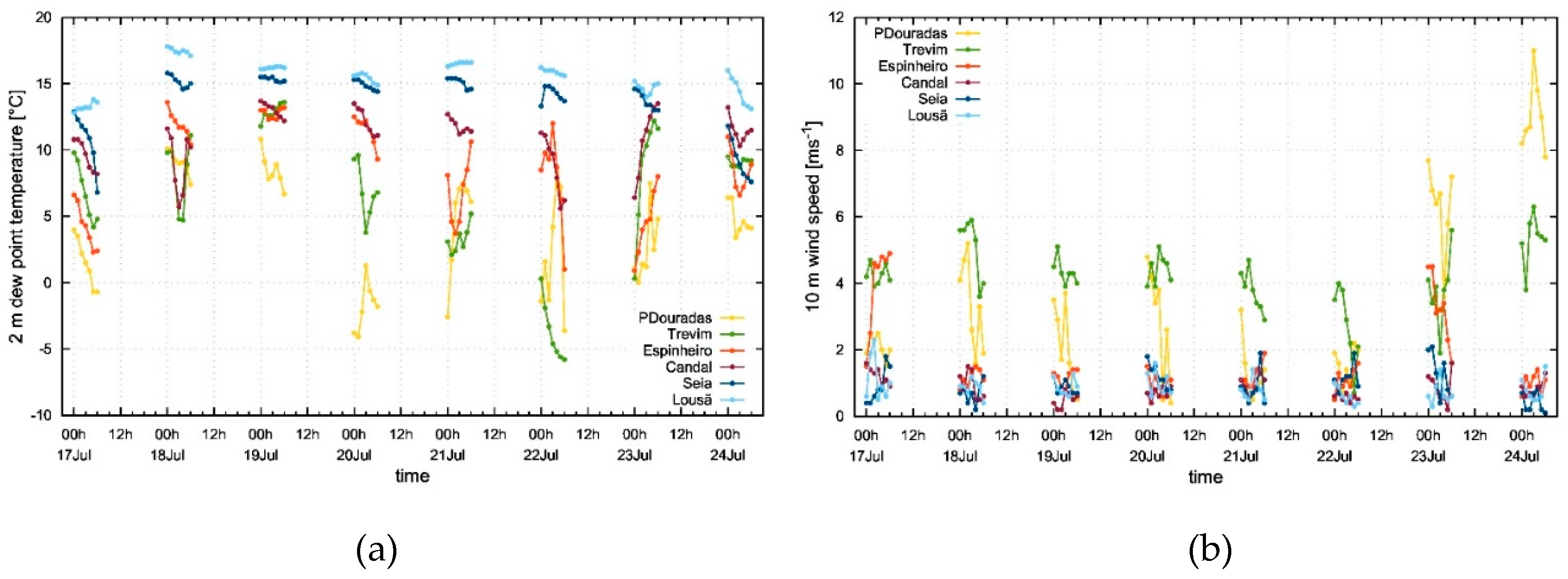

4.1 Maritime inversion, 19-22 July 2021

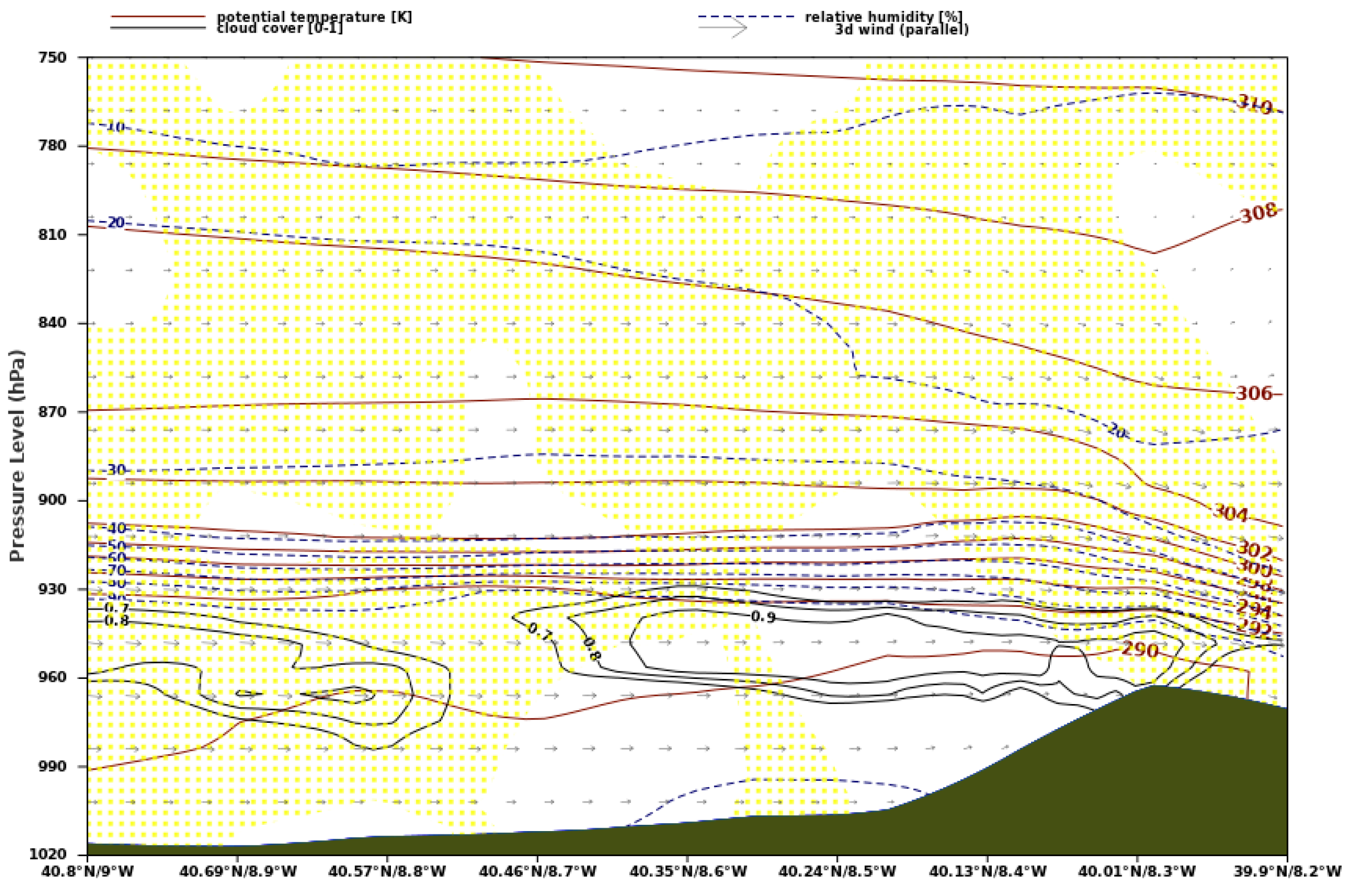

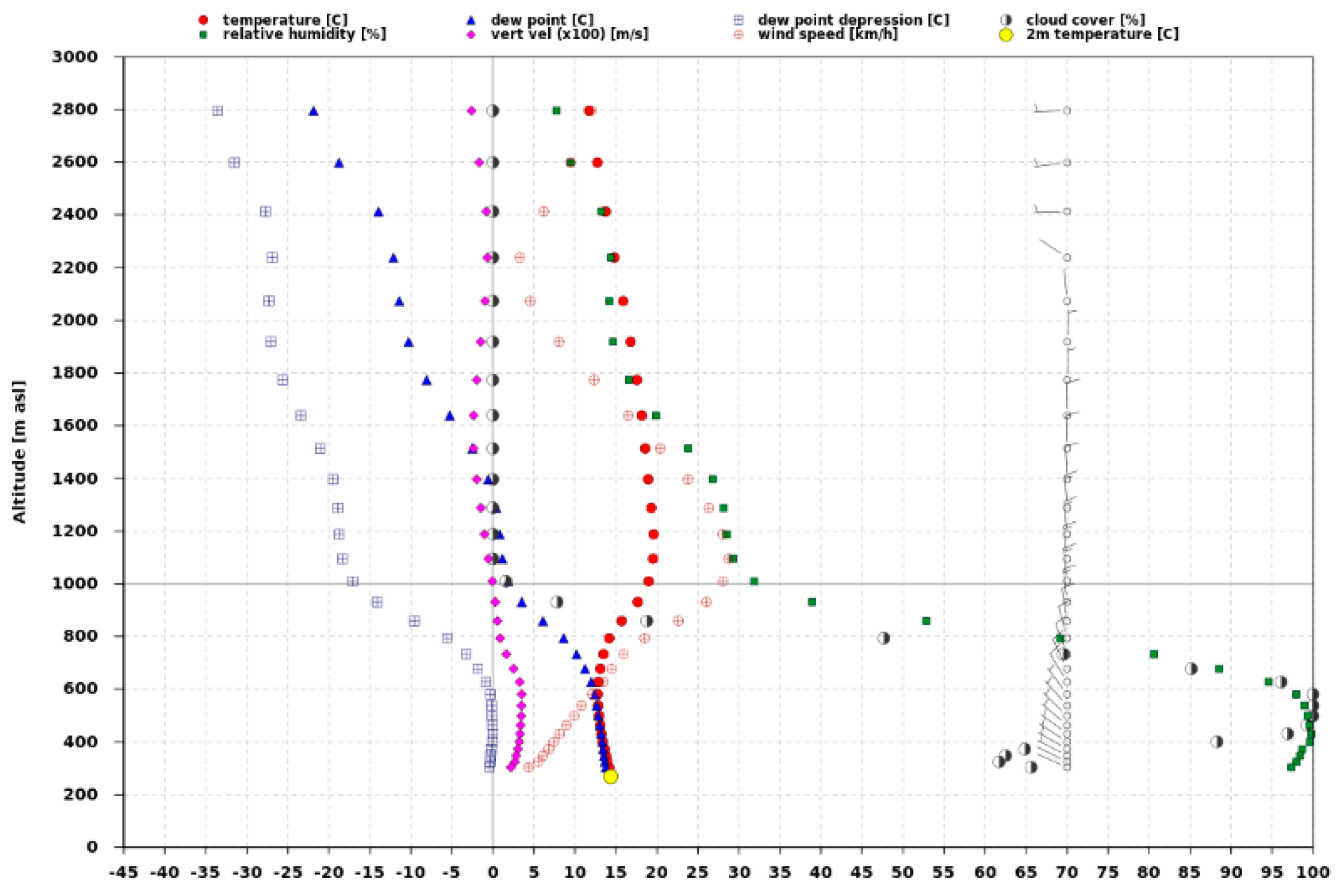

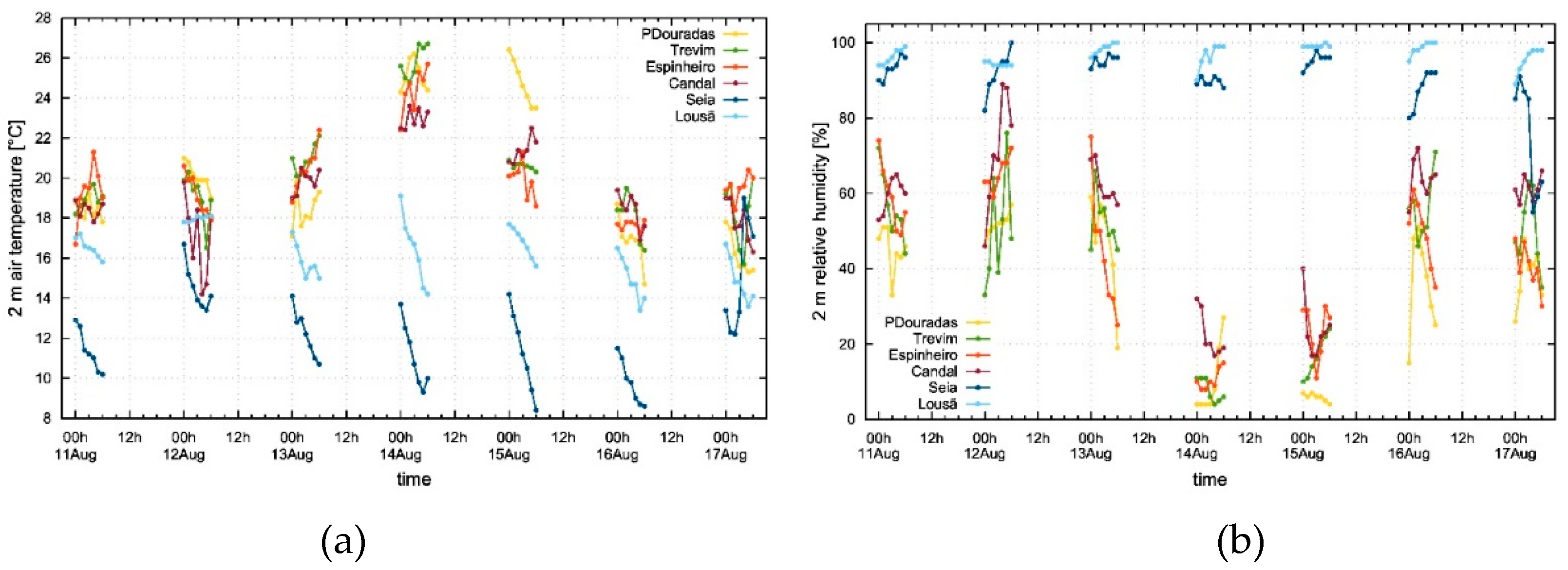

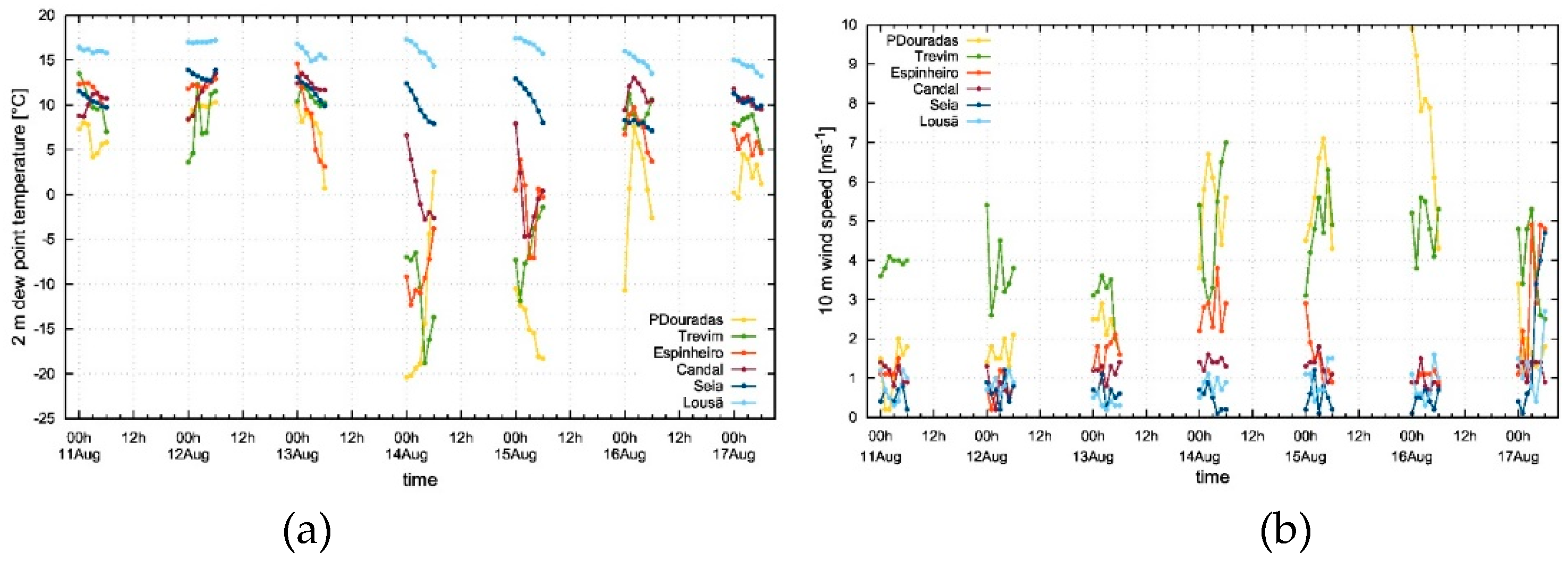

4.2 Large-scale subsidence at low elevations, 14-15 August 2021

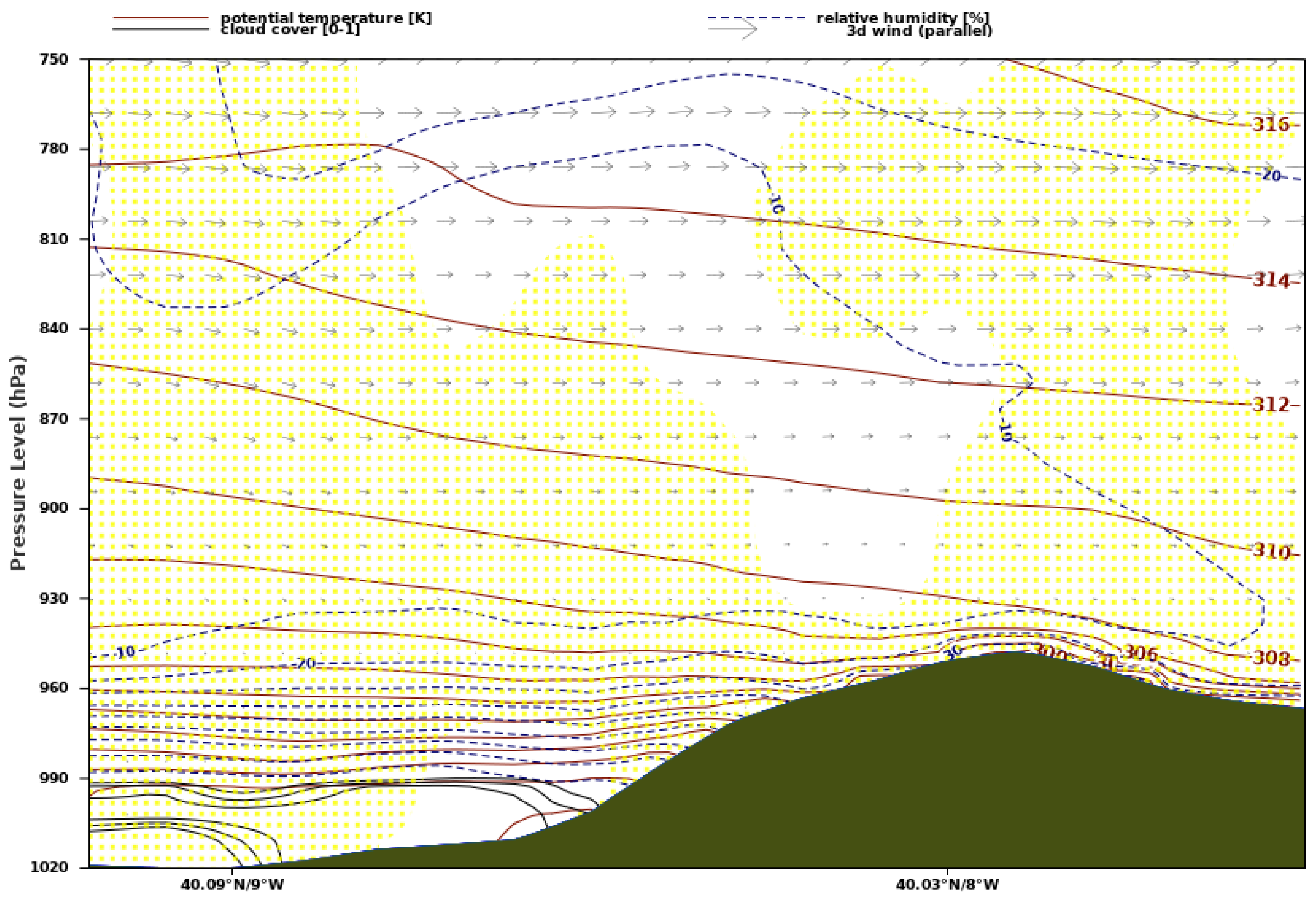

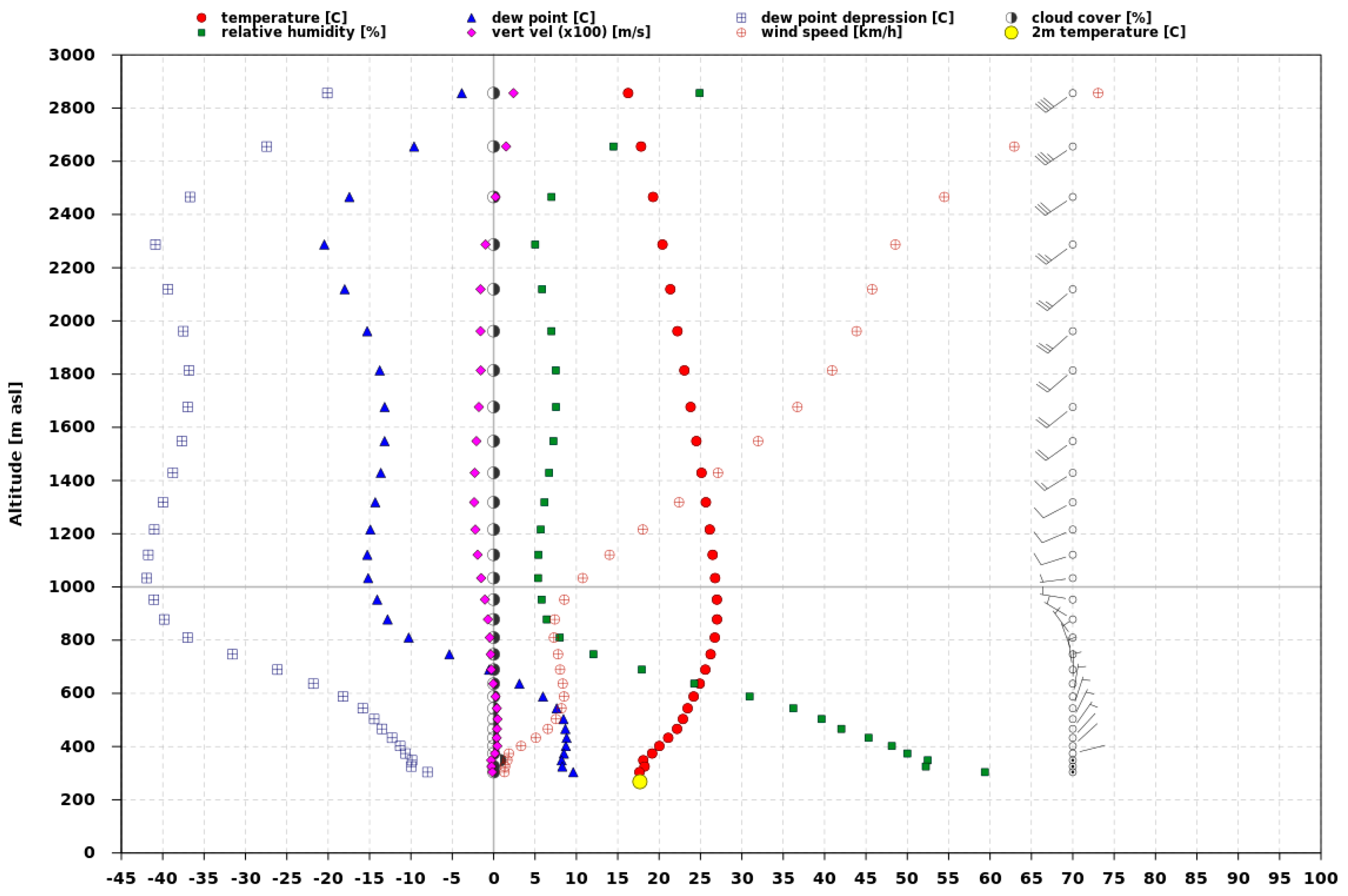

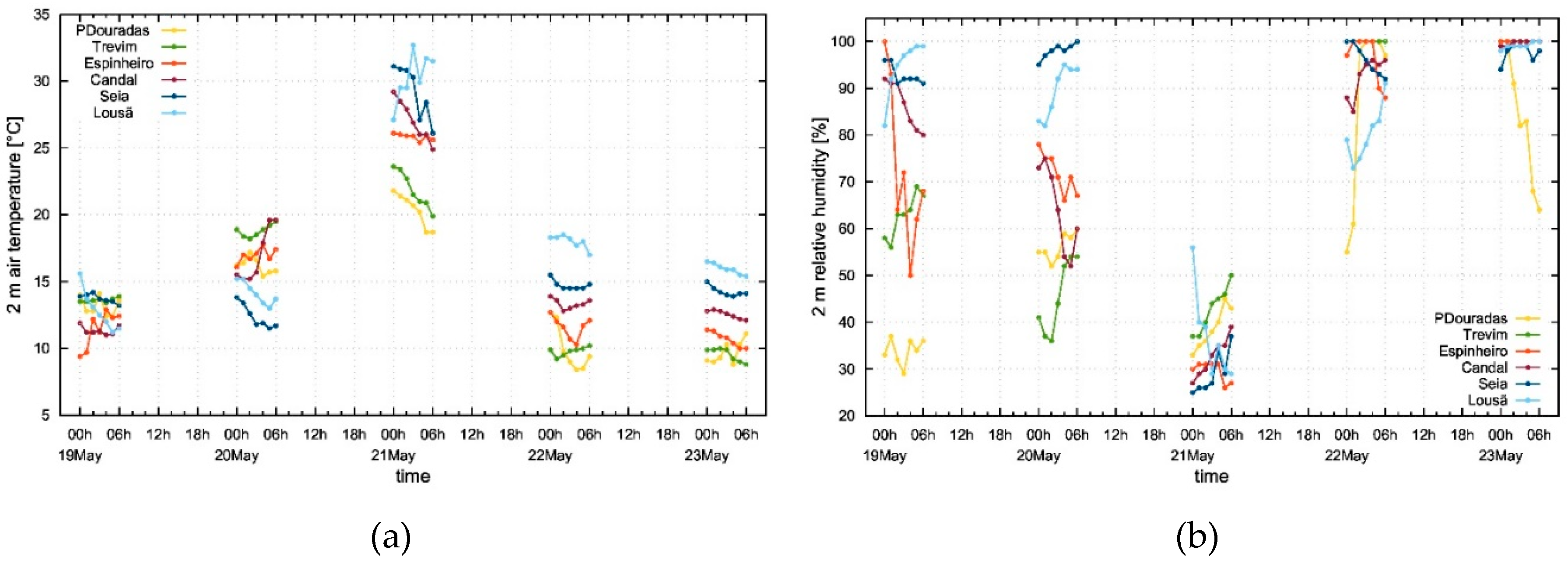

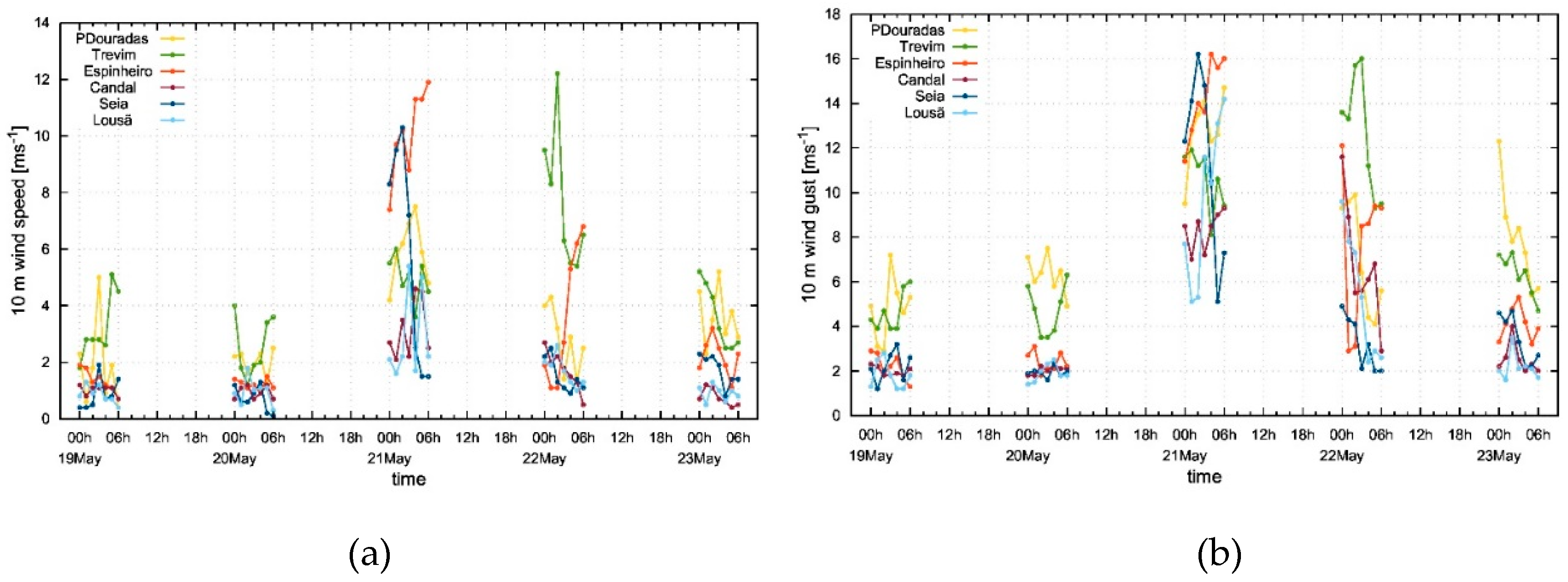

4.3 Downslope windstorm on 21 May 2022

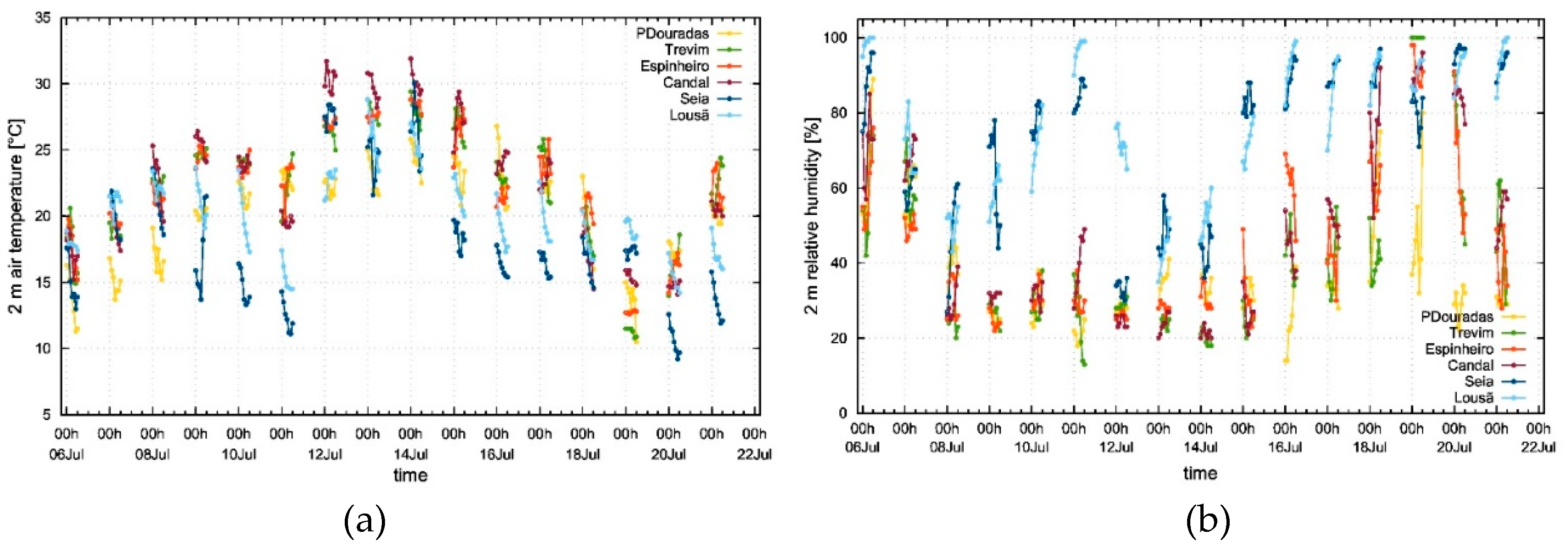

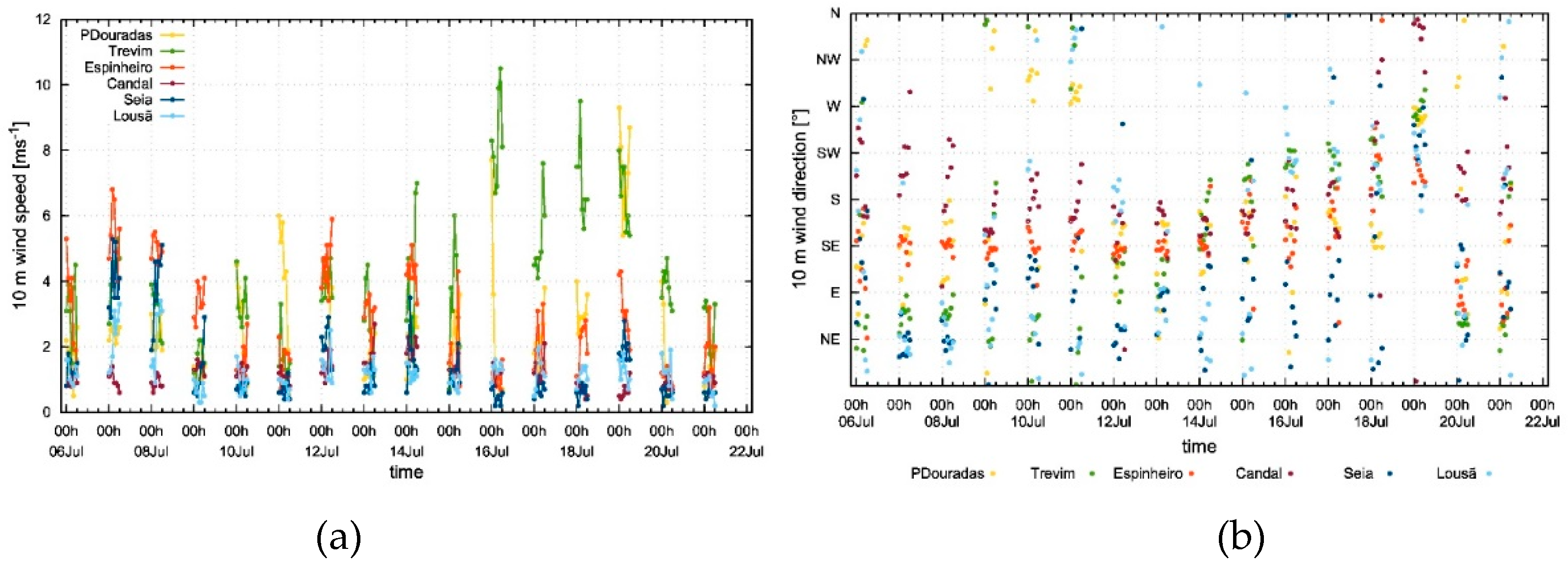

4.4 Large variability in July 2022

5. Final remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Miranda, P.M.; Coelho, F.; Tomé, A.; Valente, M.; Carvalho, A.; Pires, C.; Pires, H.; Pires, V.; Ramalho, C. 20th century Portuguese Climate and Climate Scenarios, in Santos, F.D., K. Forbes, and R. Moita (eds), 2002, Climate Change in Portugal: Scenarios, Impacts and Adaptation Measures (SIAM Project), 23-83, Gradiva, 454 pp.

- Mora, C.; Vieira, G. The Climate of Portugal. In: Vieira, G., Zêzere, J., Mora, C. (eds) Landscapes and Landforms of Portugal. World Geomorphological Landscapes. Springer, Cham, 2020, pp 33-46.

- Trigo, R.M.; Pereira, J.M.; Pereira, M.G.; Mota, B.; Calado, T.J.; da Câmara, C. and Santo, F.E. Santo. Atmospheric conditions associated with the exceptional fire season of 2003 in Portugal. Int. J. Climatol., 2006, 26, 1741–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, R.M.; Sousa, P.M.; Pereira, M.G.; Rasilla, D. and Gouveia, C. M. Modelling wildfire activity in Iberia with different atmospheric circulation weather types. Int. J. Climatol., 2016, 36, 2761–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Trigo, R.; Camara, C.; Pereira, J. and Leite, S. Synoptic patterns associated with large summer forest fires in Portugal. Agric For Meteorol, 2005, 129, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, I.; Russo, A.; M. Trigo, R. Identifying Local-Scale Weather Forcing Conditions Favourable to Generating Iberia’s Largest Fires. Forests, 2020, 11, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Gouveia, C.M.; Páscoa, P.; da Câmara, C.C.; Sousa, P.M. and Trigo, R.M. Assessing the role of drought events on wildfires in the Iberian Peninsula. Agric For Meteorol, 2017, 237, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, M.; Ferreira, J.P.; Mendes, M.T.; Silva, Á.; Silva, P.C.; Alves, D.; Reis, L.C.D.; Novo, I.; Viegas, D.X. The climatology of extreme wildfires in Portugal, 1980-2018: Contributions to forecasting and preparedness. Int J Climatol 2022, 42, 3123–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, Brian. Atmospheric interactions with wildland fire behaviour - I. Basic surface interactions, vertical profiles and synoptic structures. Int. J. Wildland Fire, 2012, 21, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, G. A. and McCaw, W. L. Atmospheric stability environments and fire weather in Australia: extending the Haines index. Centre for Australian Weather, Climate Research Melbourne, Australia, 2010.

- Chaboureau, J.P.; Guichard, F.; Redelsperger, J.-L. and Lafore, J.-P. The role of stability and moisture in the diurnal cycle of convection over land. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc., Wiley, 2004, 130, 3105–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, B. Atmospheric Moist Convection. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 2005, 33, 605–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, P.; Silva, Á.P.; Viegas, D.X.; Almeida, M.; Raposo, J.; Ribeiro, L.M. Influence of Convectively Driven Flows in the Course of a Large Fire in Portugal: The Case of Pedrógão Grande. Atmosphere, 2022, 13, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalashnikov, D.; Abatzoglou, J.; Nauslar, N.; Swain, D.; Touma, D.; Singh, D. Meteorological and geographical factors associated with dry lightning in central and northern California. Environ. Res.: Climate, 2022; 1, 025001.

- Pérez-Invernón, F. J.; Huntrieser, H.; Soler, S.; Gordillo-Vázquez, F. J.; Pineda, N.; Navarro-González, J.; Reglero, V.; Montanyà, J.; Van der Velde, O. and Koutsias, N. Lightning-ignited wildfires and long continuing current lightning in the Mediterranean Basin: preferential meteorological conditions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 2021, 21, 17529–17557. [Google Scholar]

- Análise das Causas dos Incêndios Florestais. ICNF, Lisbon, Portugal, 2014 (In Portuguese).

- 8º Relatório Provisório de Incêndios Rurais. ICNF, Lisbon, Portugal, 2022 (In Portuguese).

- Rio, J. Probabilidade de ocorrência de trovoada seca. Nota Técnica DivMV 08/2020, IPMA, Lisbon, Portugal. 2020 (In Portuguese).

- Prior, V. Estrutura Termomecânica da baixa troposfera associada ao regime de brisas em Portugal. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Aveiro, Portugal, 2006. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, P. Avaliação do desempenho das previsões do modelo AROME: posicionamento de frentes de brisa. DORE, IPMA, Lisbon, Portugal, 2011 (In Portuguese).

- Martins, J.; Cardoso, R.; Soares, P.; Trigo, I.; Belo-Pereira, M.; Moreira, N.; Tomé, R. The summer diurnal cycle of coastal cloudiness over west Iberia using Meteosat/SEVIRI and a WRF regional climate model simulation, Int. J. Climatolol., 2016, 36, 1755–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, J.J. An overview of mountain meteorological effects relevant to fire behaviour and bushfire risk. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werth, P. A.; Potter, B. E.; Clements, C. B.; Finney, M. A.; Goodrick, S. L.; Alexander, M. E.; Cruz, M. G.; Forthofer, J. A.; McAllister, S. S. Synthesis of knowledge of extreme fire behavior: volume I for fire managers. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-854. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 2011, 144 p.

- Fernando, H. J. S., Pardyjak, E. R., Di Sabatino, S., Chow, F. K., De Wekker, S. F. J., Hoch, S. W., Hacker et al. The MATERHORN: Unraveling the Intricacies of Mountain Weather. Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 96, 1945–1967.

- Whiteman, C. D. Mountain Meteorology: Fundamentals and Applications, Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 2000, 355 pp.

- Durran, D.R. Mountain Waves and Downslope Winds. In: Blumen, W. (eds) Atmospheric Processes over Complex Terrain. Meteorological Monographs, vol 23. American Meteorological Society, Boston, MA, 1990.

- Belcher, S.E.; Hunt, J.C.R. Turbulent flow over hills and waves. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 1998, 30, 507–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. B.; Gleason, A. C.; Gluhosky, P. A.; Grubišić, V. The Wake of St. Vincent. J Atmos Sci. 1997, 54, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertenstein, R.F.; Joachim, P. K. Rotor types associated with steep lee topography: influence of the wind profile. Tellus A. 2005, 57, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackadar, A. K. Boundary Layer Wind Maxima and their Significance for the Growth of Nocturnal Inversions, Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc., 1957, 38, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banta, R.; Newsom, R.K.; Lundquist, J.K.; et al. Nocturnal Low-Level Jet Characteristics Over Kansas During Cases-99. Boundary-Layer Meteorology, 2002, 105, 221–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P. Development and mechanisms of the nocturnal jet. Meteorol. Appl. 2000, 7, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Palarz, A.; Celiński-Mysław, D. and Ustrnul, U. Temporal and spatial variability of elevated inversions over Europe based on ERA-Interim reanalysis. Int. J. Climatol., 2020, 40, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palarz, A., Luterbacher, J., Ustrnul, Z., Xoplaki, E. and Celiński-Mysław, D. Representation of low-tropospheric temperature inversions in ECMWF reanalyses in Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 074043. [CrossRef]

- Stull, R.B. An Introduction to Boundary Layer Meteorology. Kluwer Academic, Publishers, Dordrecht, 1998, 666 pp.

- LeMone, M. A.; Angevine, W. M.; Bretherton, C. S.; Chen, F.; Dudhia, J.; Fedorovich, E.; et al. 100 years of progress in boundary layer meteorology. Meteorological Monographs, 2019, 59, 9.1–9.85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulos, G. S.; Blumen, W.; Fritts, D. C.; Lundquist, J. K.; Sun, J.; Burns, S. P.; Nappo, C.; Banta, R.; Newsom, R.; Cuxart, J.; Terradellas, E.; Balsley, B.; Jensen, M. CASES-99: A Comprehensive Investigation of the Stable Nocturnal Boundary Layer. Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc. 2002, 83, 555–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goens, D.W. Forecast guidelines for fire weather and forecasters, how nighttime humidity affects wildland fuels. Series: NOAA technical memorandum NWS WR, 1989, 205.

- Balch, J.K.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Joseph, M.B.; et al. Warming weakens the night-time barrier to global fire. Nature, 2022, 602, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, D.; Almeida, M. , Ribeiro, L. et al. Análise dos Incêndios Florestais Ocorridos em 15 de outubro de 2017. ADAI/LAETA, Centro de Estudos sobre Incêndios Florestais (CEIF), Coimbra University, Coimbra, Portugal, 2019 (In Portuguese).

- Novo, I.; Pinto, P.; Rio, J. and Gouveia, C. Fires in Portugal on 15th October 2017: A Catastrophic Evolution, In Advances in Forest Fire Research 2018. Eds. Coimbra University Press, Coimbra, Portugal, 2018, pp. 57–70. 20 October.

- Fernando, H. J. S.; Mann, J.; Palma, J. M. L. M.; Lundquist, J. K.; Barthelmie, R.J.; Belo-Pereira, M.; Brown, W.O.J.; et al. The Perdigão: Peering into Microscale Details of Mountain Winds. In Bull. Am. Meteorol.; 2019; Volume 100, pp. 799–819.

- Silva, P.; Carmo, M.; Rio, J.; Novo, I. Changes in the Seasonality of Fire Activity and Fire Weather in Portugal: Is the Wildfire Season Really Longer? . Meteorology 2023, 2, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, I.; Ferreira, J.; Silva, P.; Ponte, J.; Moreira, N.; Ramos, R., Rio, J. and Cardoso, E. Large Fires in Portugal and Synoptic Circulation Patterns: meteorological parameters and fire danger indices associated with the critical weather types. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Forest Fire Research, Coimbra, Portugal, 14-18 November 2022.

- Haraldur, O. and Bao, J.W. Uncertainties in numerical weather prediction, 1st ed. Elsevier, 2021, 364 pp.

| Region | Station Name | Latitude (°N) | Longitude (°W) | Elevation [m] | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seia | Penhas Douradas | 40.41 | 7.56 | 1380 | Small plateau on the ridge | IPMA |

| Espinheiro | 40.41 | 7.67 | 995 | Medium slope | IPMA/FireStorm | |

| Seia | 40.46 | 7.69 | 438 | Open valley | IPMA/Firestorm | |

| Lousã | Trevim | 40.09 | 8.18 | 1167 | Ridge | IPMA/FireStorm |

| Candal | 40.08 | 8.20 | 621 | Narrow valley in medium slope | IPMA/FireStorm | |

| Lousã | 40.13 | 8.24 | 195 | Open valley | IPMA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).