1. Introduction

Raptors are all species that have retained their raptorial lifestyle derived from a common ancestor. They include the orders Accipitriformes, Cariamiformes, Cathartiformes, Falconiformes, and Strigiformes, the latter being represented by owls [

1], which are widely distributed throughout the world, with approximately 11% of all species occurring in Brazil, and most of them (23 species) are poorly studied [

2]. Strigiformes currently comprise two distinct families: the Tytonidae and the Strigidae. Species of this order have variable sizes and adaptations for hunting in low-light environments and have well-developed, forward-facing eyes, which enable binocular vision, in addition to a very sensitive hearing for the location of prey and the outer area of the primary feathers adapted for silent flight. They generally have nocturnal and crepuscular habits, with some exceptions of dusk behavior [

1,

3].

The Strigidae family includes the genus Megascops, with

Megascops choliba, popularly known as Tropical screech owl, one of the most frequent species of birds of prey in rehabilitation centers in Brazil [

4,

5]. They are relatively small owls with a diet of insects [

6]. Although it is abundant in its distribution, information on bacterial and endoparasitic agents as causes of diseases affecting this species within Brazil is scarce compared to other Falconiformes and Strigiformes, mainly within the Amazon Biome [

4,

5]. Among the predisposing factors are nutritional deficiencies, environmental changes, concomitant diseases, stress in captivity, and inadequate sanitary management that induce immunosuppression [

7]. In addition, the fact that birds develop different bacterial and parasitic infections without showing clinical signs, and when they do, they are often already in an advanced stage of the disease, leads the animals to an unfavorable prognosis, which often results in death [

7].

Knowledge of the epidemiology of infectious agents and their relationships with possible susceptible hosts are critical factors for assessing the risk of occurrence of a given pathology and its impact on biodiversity. In this context, determining the incidence and distribution of pathogens is of great urgency to know the actual sanitary status of captive and wild birds. And, carnivorous animals, such as raptors, occupying the top of the trophic network, can act as “bio accumulators” of exposure to pathogens, resulting in high infection rates, making them sentinels and strategic targets in surveillance programs for pathogen detection [

5,

7,

8]. Therefore, given the importance of this information in birds of prey and the scarcity of data in the literature in this area, the objective was to report the first case of airsacculitis caused by enterobacteria and eggs of the superfamily Diplotriaenoidea in

Megacops choliba in the Amazon Biome.

2. Materials and Methods

A specimen of Megascops choliba, a young male, was attended at the Wild Animals Sector of the Veterinary Hospital (HVSAS) of the Federal University of Pará (UFPA). During the clinical examination, no fracture or other type of injury was found; however, he did not know how to fly or hunt because he was young. The animal remained hospitalized and was fed beef and liver of bovine origin, chicken heart, mouse, and mealworm larvae, offered twice a day, in the proportion of 10% of live weight.

After five months of hospitalization and with the evaluation of the clinical condition determined as healthy, the bird began the rehabilitation process for release through falconry techniques to restore the ability to fly and hunt. For this purpose, the bird was equipped with anklets in the tarsus region and other accessories such as straps, swivels, and leashes. The initial phase of falconry training, known as taming, consisted of acclimatizing the animal to handling, the glove, and the habit of feeding off the fist. In the second phase, there was the first jump, where the animal was stimulated by offering food, the first coming from a training perch to the trainer's fist. The third phase, in turn, consisted of the flight stimulus from a fixed point (perch) to the trainer.

The bird started to be fed only during training, with mice, chicken, and mealworm larvae, receiving food when landing on the trainer's glove and repeating the process to improve its physical conditioning. The amount of food provided ranged from 5 to 15 g. It was weighed before and after training to check the metabolism of ingested food and body mass, associating it with the response during physical activity, classified as impaired, fair, good, or excellent.

Depending on the positive response to the stimuli, the animal would move on to the following steps: free flight, escape, hunting, and release. The training lasted for 37 days, taking place uninterruptedly, with the bird showing excellent development, responding well to commands for flight, and always attentive and interested in food. It even flew without a guarantor in an external environment with excellent response to the order, with the best flight weight of 97 g.

The training was suspended on the 38th day when the bird showed signs of weakness and lack of appetite, even with a constant food supply, so it was kept under observation at the avian treatment unit (ATU). Two days after the onset of the clinical presentation, he started to be medicated with oxytetracycline (48 mg/kg) every 48 hours, intramuscularly; sulfamethoxazole (48 mg/kg), single dose, orally; mebendazole (25 mg/kg), every 12 hours, for five days, orally; Potenay (0.5 ml/kg), every 24 hours, for two days, intramuscularly, and received hydration with 0.9% sodium chloride (50 ml/kg) together with warmed Mercepton (5ml/kg) every 8 hours, for two days, remaining in the ATU for seven days.

On the 7th day of observation at the ATU, fecal collection and copro-parasitological examination were performed using the direct fresh method, according to Hoffmann et al. [

9]. However, during the course of fluid therapy, the animal died. As a result, the necroscopic examination was performed according to the techniques described by Majó & Dolz [

10]. During the necropsy, feces samples were collected for parasitological tests using the centrifuge-flotation process by Faust et al. [

11]. Tissue samples were preserved in 10% buffered formalin and sent to the Laboratory of Animal Pathology at UFPA for histological analysis, as described by Nunes & Cinsa [

12].

For the microbiological examination, the tonsils and tongue were collected. Swabs were taken from the oral cavity, stored in sterile falcon tubes, and sent in Stuart medium to the Laboratory of the National Primates Center (CENP) for bacterial identification and characterization using VITEK 2 bioMerieux automated equipment.

This research was authorized by the animal experimentation ethics committee (CEUA) of the Federal University of Pará (UFPA) under protocol number 8888280618 (ID 002193).

3. Results

During the observation in the ATU, it was verified that the animal presented apathy, cachexia, ruffled feathers, dirty feathers around the cloaca with dry feces, vomiting, and dyspnea, spending most of the time with eyes closed. During this period, a sudden change in the ambient temperature was also observed, as it was a period of intense rainfall with an average rainfall of 366 mm and a minimum average temperature of 23ºC and a maximum of 28ºC. The importance of cold environments for birds is emphasized, as they tend to increase their metabolism to maintain body temperature. The copro-parasitological exams carried out using the direct fresh method and the centrifuge-flotation technique detected many eggs of the Diplotriaenoidea superfamily (

Figure 1).

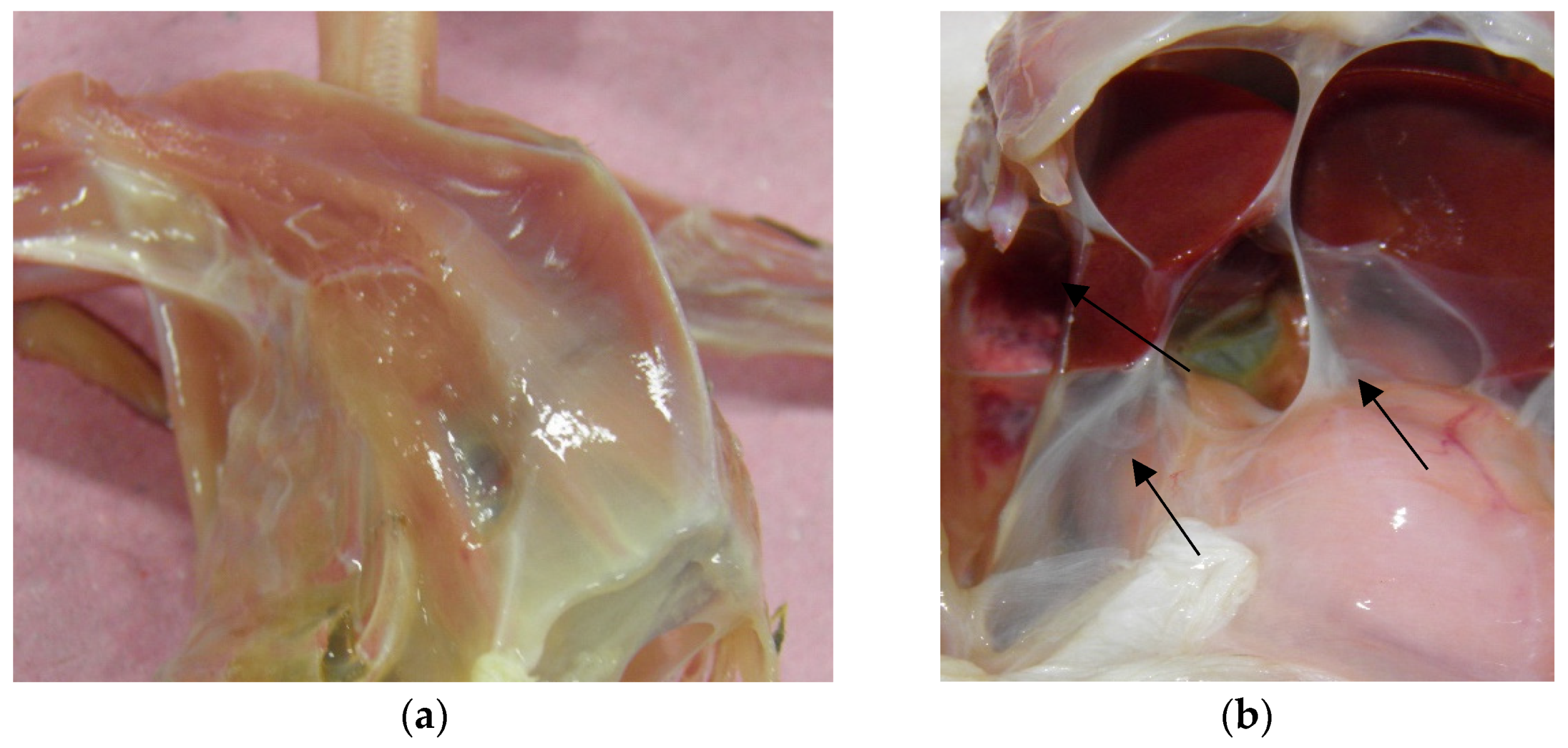

The impressions of the necroscopic exam were severe weight loss, with significant loss of pectoral muscle mass, characterizing a picture of cachexia, and observing the prominence of the keel (

Figure 2a). In the oral cavity and proventriculus, pieces of undigested food were found. The air sacs were thickened, with disseminated turbidity giving a whitish appearance (

Figure 2b), and mucopurulent content was detected. Adult nematodes were not observed in the air sacs macroscopically. The stool was tough in the large intestine with much gas. The liver was enlarged with rounded edges, the spleen was whitish and enlarged, and the kidneys were markedly hyperemic.

The material sent for microbiology showed

Escherichia coli with bio-number 0405610450406610 with 99% probability,

Klebsiella pneumoniae with bio-number 6607734453164410 with 98% probability, and

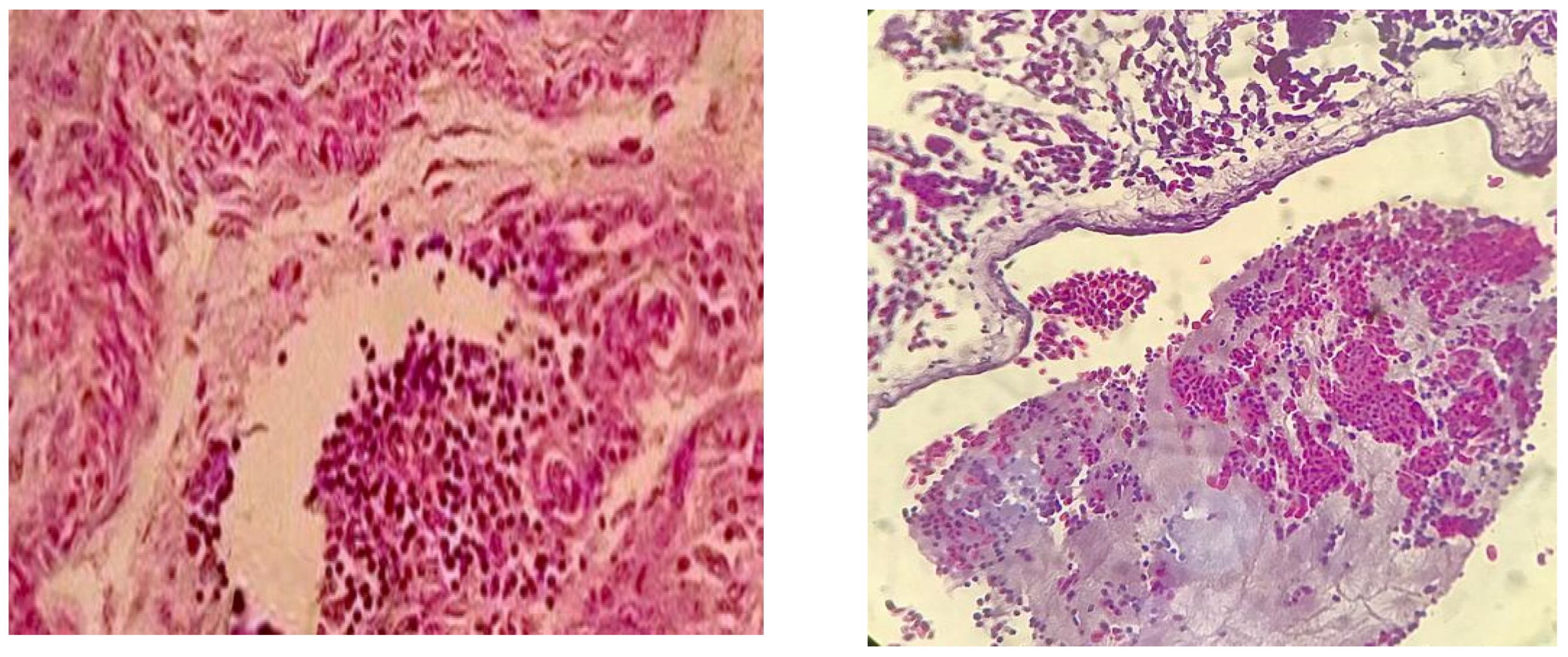

Enterobacter aerogenes with bio-number 2607734553576412 with 93% probability. The histopathological examination also showed air sacs with coalescing multifocal erosion in the mucosa with moderate heterophilic infiltration (

Figure 3a). The lung showed diffuse congestion with granular eosinophilic material deposition in the parabronchi (presence of fibrin) (

Figure 3b). Thus, the histopathological diagnosis was bacterial airsacculitis, and heterophilic airsacculitis, moderate coalescent multifocal, was described.

4. Discussion

The most frequent helminths in prey birds are nematodes in the digestive and respiratory systems [

5,

13]. Those belonging to the order Spirurida, family Diplotrianidae, are occasionally found in the air sacs of wild birds, with

Serratospiculum spp.,

Serratospiculoides spp., and

Diplotriaena spp. the prominent representatives and are responsible for causing intense pulmonary alteration [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. They are described more frequently in Falconiformes than in Strigiformes, which suggests that air sac nematodes are less frequent in this group [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Recently there were the first reports of serratospiculiasis in Falconiformes in Latin America [

19,

20], and it is suggested that this is the first report of the identification of eggs of the superfamily Diplotriaenoidea in

Megascops choliba.

It should be considered that in parasitic infestations in birds, clinical signs are associated with stress conditions. Those caused by parasites of the Diplotriaenoidea family include dyspnea, weight loss, anorexia, and lethargy, in addition to affecting flight performance, thickening of the air sac membrane and sudden onset of respiratory discomfort are common [

14,

15,

16,

21]. Another important aspect is that adult parasites, larvae, and eggs in the air sacs can damage the tissues and predispose to secondary bacterial infections, leading to an increased risk of airsacculitis and pneumonia, resulting in the death of the host [

18,

22]. In this context, the specimen in this study was in captivity, which could have led him to stress conditions and, therefore, to present the clinical picture that culminated in death.

Feeding habits directly influence the parasitic fauna, with omnivorous-insectivorous birds being more susceptible to parasitism, due to diet diversity [

7]. Thus, it should be considered that

Megascops choliba already has reports of this feeding habit. The parasites of the Diplotriaenoidea superfamily have arthropods as intermediate hosts, mainly coprophagous beetles, in their heteroxenous life cycle. Raptors are usually infected by ingesting intermediate and paratenic hosts [

7,

22]. In this case, although the bird received a diet based on mealworms, it cannot be said that this was the source of the bird's infection. In addition, hunting birds, even in captivity and with physical barriers, tend to prey on insects that eventually come within their reach.

It is essential to point out that the eggs of the Diplotraenoidea superfamily were identified, in the present report, only in feces through parasitological examination. Some authors argue that detecting embryonated eggs in the feces does not necessarily indicate the presence of adult nematodes of these genera in the air sacs and that a positive stool test would close the diagnosis [

18,

20,

21,

22]. Considering that the diagnosis most often occurs due to the accidental finding of embryonated eggs during parasitological examinations of feces and pharyngeal swabs, some authors propose the hypothesis of intermittent elimination and recommend the collection and analysis of repeated samples of stool and pharyngeal content as an adequate diagnostic tool [

18,

22]. It is added that standard necropsy procedures must be strictly followed to help identify and diagnose these cases [

18].

The microbiological examination identified the presence of bacteria belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family.

E. coli, for example, is considered commensal and opportunistic;

Klebsiella sp. and

Enterobacter sp. are regarded as opportunistic pathogens [

23,

24]. And, despite being considered commensals in some bird species' intestinal microbiota, they can multiply and cause intestinal and extra-intestinal infections under favorable conditions. Additionally, histopathology alterations are similar to those observed in enterobacterial infections [

24]. Therefore, correlating this information with the result of 99% probability, it is believed that the primary bacterial agent involved in this case is

E. coli since infection by this agent leads to cachexia, lethargy, sepsis, dyspnea, and airsacculitis, is common in immunocompromised animals subjected to stress or overexposure to the agent [

24,

25].

For antimicrobial therapy, oxytetracycline and sulfamethoxazole were used. Given the impossibility of performing the isolation of the agent and antimicrobial sensitivity test, the choice was based on the clinical diagnosis and the rapid evolution of the condition. In this context, oxytetracycline was used due to its good action against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, and sulfamethoxazole was due to the initial suspicion of coccidiosis. In treatment for colibacillosis in an

Ara macao, oxytetracycline hydrochloride (Avitrin Antibiotic) was used in a prescription of 5 drops every 12 hours for seven days orally, with clinical improvement in the animal at the end of the treatment [

26]. However, despite being a broad-spectrum antibiotic, the literature points to studies on the antimicrobial resistance of

E. coli,

Klebsiella spp., and

Enterobacter spp. to this drug in wild birds [

26,

27,

28,

29], which may have been a factor in the unfavorable clinical evolution of the owl.

Regarding this aspect, it is essential to emphasize the importance of access to complementary exams while caring for wild animals. Still, often there need to be sources of funding, making it challenging to send samples. In this case, especially the microbiological tests for isolation and antibiogram would have contributed to the identification of the agent and targeted therapeutic implementation, although one should consider the speed of evolution of the pathological condition and the imminent need for intervention. On the other hand, the antiparasitic therapeutic scheme included, in addition to sulfamethoxazole, the use of mebendazole, which is reported in the literature as effective in treating parasites of the Diplotriaenoidea superfamily at a dose of 20 mg/kg, orally every 24 hours for 14 days [

30]. Although other authors point out the ineffectiveness of this medication due to the anatomical location of the parasite [

16,

21], possibly among the drugs available at the time of care, it was the best choice.

Still on the possibilities, different treatment protocols with ivermectin (1 mg/kg, intramuscular, single dose), fenbendazole (20 mg/kg, orally, every 24 hours for 14 days), doramectin (1 mg/kg, intramuscular, single dose) and merlasomine (0.25 mg/kg, intramuscularly for two days) have been described separately or in combination [

16,

21,

30]. However, the treatment recommendation is controversial, as some authors report that the mass of dead parasites in the air sacs can cause necrotic focus. In contrast, others recommend a dose of ivermectin to cause paralysis and then later remove them by endoscopy with a repetition of the drug dose after the procedure [

30]. Other studies demonstrate improved flight and fitness after treatment with associated ivermectin and melarsomine [

16,

21].

5. Conclusions

The present report describes the first identification of eggs of the Diplotriaenoidea superfamily in Megascops choliba and airsacculitis caused by enterobacteria, which indicates the inclusion of these agents as differential diagnoses in respiratory and enteric clinical pictures in Megascops choliba and other species of Strigiformes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.G.d.S.O., R.C.d.S., C.T.d.A.L., S.F.S.D. and F.M.S.; methodology, H.G.d.S.O., R.C.d.S., C.T.d.A.L., A.I.d.J.S., S.R.R.d.A.S. and S.F.S.D.; formal analysis, H.G.d.S.O., R.C.d.S., C.T.d.A.L., S.F.S.D. and F.M.S; investigation, H.G.d.S.O., R.C.d.S., C.T.d.A.L., A.I.d.J.S., S.R.R.d.A.S.; data curation, H.G.d.S.O., R.C.d.S., C.T.d.A.L., S.F.S.D. and F.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.G.d.S.O., R.C.d.S., C.T.d.A.L., S.F.S.D. and F.M.S.; writing—review and editing, H.G.d.S.O., A.I.d.J.S., C.T.d.A.L., S.F.S.D. and F.M.S; supervision, C.T.d.A.L., S.F.S.D. and F.M.S.;; project administration, C.T.d.A.L., S.F.S.D. and F.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol number 8888280618 (ID 002193) was approved by the National Council for Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA) and was approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use of the Federal University of Para (CEUA/UFPA) in the meeting of 03/07/2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), FAPESPA (Fundação Amazônia de Amparo a Estudos e Pesquisas do Estado do Pará), CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Finance Code 001), Centro Nacional de Primatas (CENP) do Instituto Evandro Chagas (IEC) by microbiological analysis, Laboratório de Patologia Animal (LABPATO) by histopathological analysis and Laboratório de Parasitologia Animal by parasitological analysis do IMV-UFPA (Instituto de Medicina Veterinária da Universidade Federal do Pará) and PROPESP-UFPA (Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação da Universidade Federal do Pará) by paying the publication fee of this article via the Programa Institucional de Apoio à Pesquisa—PAPQ/2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McClure, C. J. W.; Schulwitz, S. E.; Anderson, D. L.; Robinson, B. W.; Mojica, E. K. Therrien, J. F.; Oleyar, M. D.; Johnson, J. Commentary: Defining raptors and birds of prey. J. Raptor Res. 2019, 53, 419-430. [CrossRef]

- Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO). Available online: http://www.cbro.org.br/listas (accessed on 01 March 2023).

- Enríquez, P. L.; Eisermann, K.; Mikkola, H.; Motta-Junior, J. C. A review of the Systematics of Neotropical Owls (Strigiformes). In Neotropical Owls; Enriquez, P. (eds); Springer: Cham, 2017, pp. 7-19. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. S.; Zanette, R. A.; Lara, V. M.; Gressler, L. T.; Carregaro, A. B.; Santurio, J. M; Monteiro, S. G. Gastrointestinal parasites of owls (Strigiformes) kept in captivity in the Southern region of Brazil. Parasitol. Res. 2009, 104, 485-487. [CrossRef]

- Andery, D. A.; Ferreira Junior, F. C.; Araújo, A. V.; Vilela, D. A. R.; Marques, M. V. R.; Marin, S. Y.; Horta, R. S.; Ortiz, M. C.; Resende, J. S.; Martins, N. R. S. Health assessment of raptors in triage in Belo Horizonte, Mg, Brazil. Braz. J. Poult. Sc. 2013, 15, 247-256. [CrossRef]

- Motta-Junior, J. C. Diet of breeding Tropical Screech-Owls (Otus choliba) in Southeastern Brazil. J. Raptor Res. 2002, 36, 332-334.

- Costa, I. A.; Coelho, C. D.; Bueno, C.; Ferreira, I.; Freire, R. B. Ocorrência de parasitos gastrointestinais em aves silvestres no município de Seropédica, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Cien. Anim. Bras. 2010, 11, 914-922. [CrossRef]

- Catão-Dias, J. L. Doenças e seus impactos sobre a biodiversidade. Cien. Cult. 2003, 55, 32-34.

- Hoffman, R. P. Diagnóstico de parasitismo veterinário. Editora Sulina: Porto Alegre, Brasil, 1987, 156p.

- Majó, N.; Dolz, R. Atlas de la necropsia aviar; Bellaterra: SERVET, Espanha, 2010; pp. 6-22.

- Faust, E. C.; D’Antoni, J. S.; Odom, V.; Miller, M. J.; Peres, C.; Sawitz, W.; Thomen, L. F.; Tobie, J.; Walker, J. H. A critical study of clinical laboratory technics for the diagnosis of protozoan cysts and helminth eggs in feces. Amer. J. Trop. Med. 1938, 18, 169-183. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C. S.; Cinsa, L. A. Príncipios do processamento histológico de rotina. Rev. Interd. Est.s Exp. 2016, 8, 31-40.

- Krone, O.; Cooper, J. E. Parasitic Diseases. In Birds of Prey: Health & Disease, 3th ed.; Cooper, J. E.; Blackwell: Malden, United States of America, 2002, pp. 105-120.

- Königová, A.; Molnár, L.; Hrcková, G.; Várady, M. The first report of serratospiculiasis in Great Tit (Parus major) in Slovakia. Helmint. 2013, 50, 254-260. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, S. P.; Blume, G. R.; Barbosa, C. H. G.; Batista, J. S.; Pereira, F. M. A. M.; Reis Junior, J. L.; Sant’Ana, F. J. F. Aerossaculite por diplotrianídeos em aves estrigiformes do Distrito Federal. VIII Encontro Nacional de Diagnóstico Veterinário e III Encontro Internacional de Sanidade de Animais de Produção, Cuiabá, Brasil, 10-13 de Novembro de 2014.

- Al-Timimi, F.; Nolosco, P.; Al-Timimi, P. Incidence and treatment of serratospiculosis in falcons from Saudi Arabia. Vet. Rec. 2009, 165, 408-410. [CrossRef]

- Dolinská, S.; Drutovic, D.; Mlynárcik, P.; Königová, A.; Molnár, L.; Dolinská, M. U.; Strkolcová, G.; Várady, M. Molecular evidence of infection with air saic nematodes in the great tit (Parus major) and the captive-bred gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus). Parasito. Res. 2018, 117, 3851-3856. [CrossRef]

- Azmanis, P. N.; Krautwald-Junghanns, M. E.; Schmidt, V. Suspected toxicity by biological waste and air saic nematode infestation in a free-living peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus). J. Hel. Vet.y Med. Soc. 2017, 65, 243-256. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Puerta, L. A.; Ospina, P. A.; Ramirez, M. G.; Cribillero, N. G. Primer registro de Serratospiculum tendo (Nematoda: Diplotrianidae) para el Perú. Rev. Per. Biol. 2014, 21, 111-114. [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, J.; Merra y Sierra, R. L.; Neira, G.; Ibaceta, D. E. J.; Saggese, M. D. Air sac nematode (Serratospiculum tendo) infection in a Austral Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus cassini) in Argentina. J. Wild. Dis. 2019, 55, 179-182. [CrossRef]

- Tarello, W. Serratospiculosis in falcons from Kuwait: Incidence, pathogenicity and treatment with merlasomine and ivermectin. Paras. 2006, 13, 59-63. [CrossRef]

- Sterner, M. C.; Cole, R. A. Diplotrianea, Serratospiculum and Serratospiculoides. In Parasitic Diseases of Wild Birds, Atkinson, C. T.; Thomas, N. J.; Hunter, D. B.; Blackwell: Iowa, United States of America, 2008, pp. 434-439. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J. E. Nutritional diseases, including poisoning in captive birds. In Birds of Prey: Health & Disease, 3th ed.; Cooper, J. E.; Blackwell: Malden, United States of America, 2002, pp. 143-162.

- Maiorki, K. M.; Fukumoto, N. M. Colibacilose Aviária: Revisão de Literatura. Braz. J. Develop., 2021, 7, 99696-99707. [CrossRef]

- Padial, B. E.; Donnaruma, T. L.; Sater, L. M. A.; Lima, T. G.; Lopez, E. Q. Diagnóstico e reabilitação de Ara-piranga, Ara macao (Linnaeus, 1758), diagnosticada com Escherichia coli, em cativeiro na Fazenda Palmares, Santa Cruz das Palmeiras, SP, Brasil – relato de caso. Braz. J. An. Envir. Res. 2020, 3, 4179-4187. [CrossRef]

- Giacopello, C.; Foti, M.; Mascetti, A.; Grosso, F.; Ricciardi, D.; Fisichella,V.; Lo Piccolo, F. Antimicrobial resistance patterns of Enterobacteriaceae in European wild birds species admitted in a wildlife rescue centre. Vet. Ital. 2016, 52, 139-144. [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. A.; Ponder, J. B.; Wilette, M.; Johnson, T. J.; VanderWaal, K. L. Merging metagenomics and spatial epidemiology to understand the distribution of antimicrobial resistence genes from Enterobacteriaceae in wild owls. Appl. Envir. Microb. 2020, 86. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.; Simões, R.; Oliveira, M.; Vaz-Pires, P.; Brandão, R.; Costa, P. M. Multidrug resistance in wild bird populations: Importance of the food chain. J. Zoo Wild. Med 2015, 46, 723-731. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, A.; Baldomá, L.; Molina-López, R. A.; Martin, M.; Darwich, L. Microbiological diagnosis and antimicrobial sensitivity profiles in diseased free-living raptors. Avian Path. 2017, 46, 442-450. [CrossRef]

- Caliendo, V.; McKinney, P. Fungal airsacculitis associated with serratospiculiasis in captive falcons of United Arab Emirates. Vet Re. 2013, 173, 143. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).