Submitted:

22 May 2023

Posted:

23 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Problem Statement

-

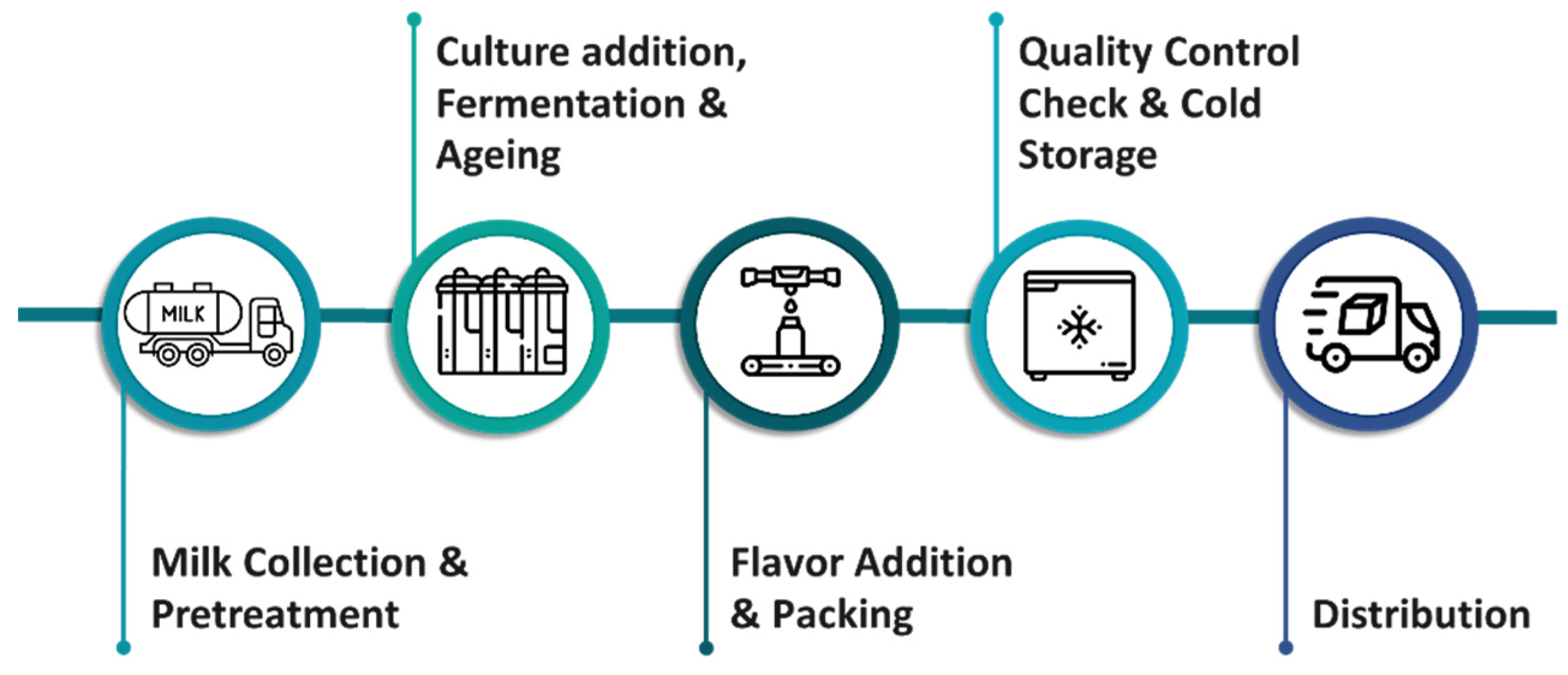

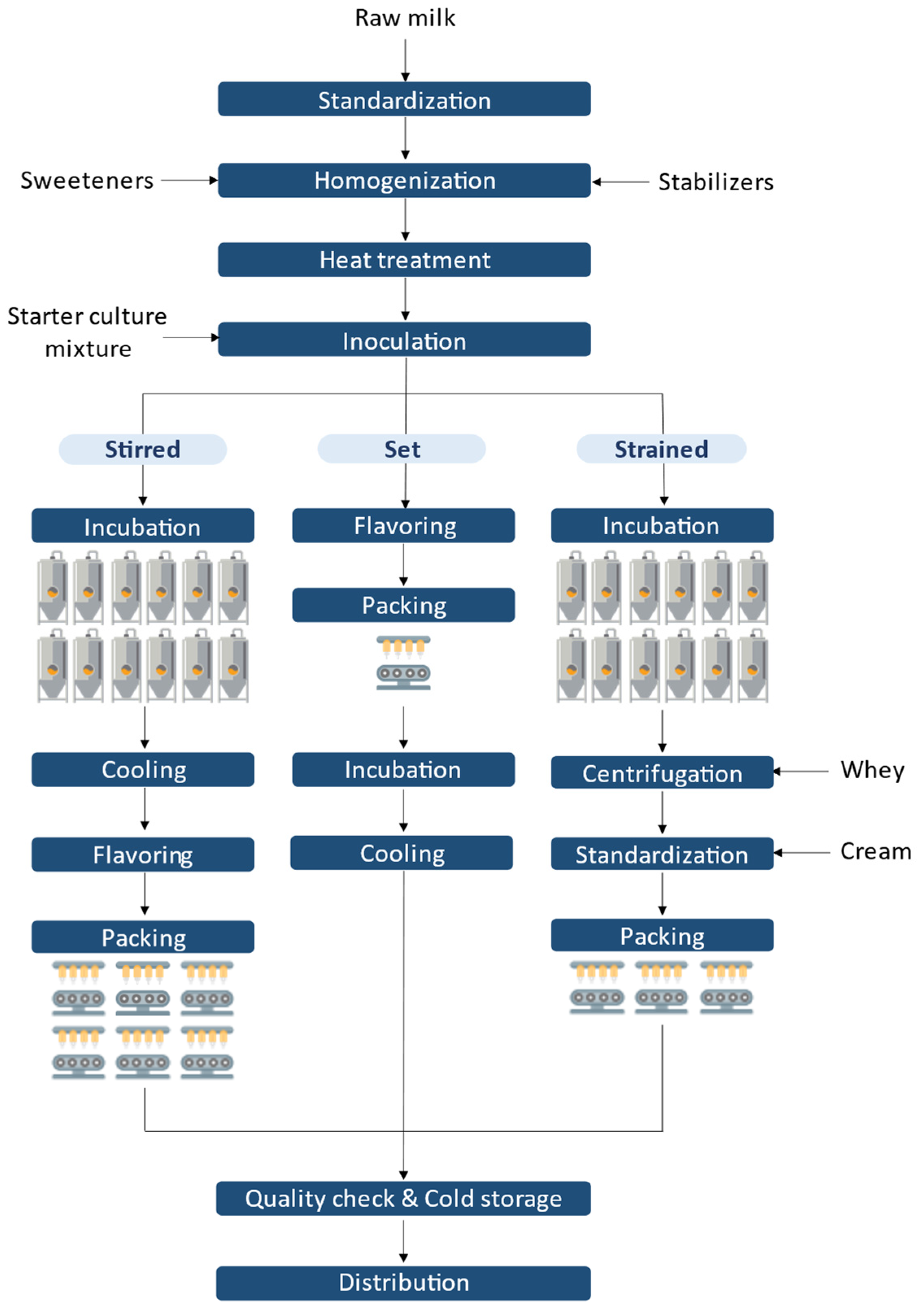

Milk Collection & PretreatmentDaily milk is collected from local farms, decontaminated and transferred to the factory. It should be noted that the composition of fresh milk in water, fat, protein, lactose and minerals varies from day to day. Once the milk reaches the factory, it is subject to a variety of processes including standardization, homogenization and heat treatment. Firstly, two types of standardization are done to improve the quality of the final yogurt product concerning the fat content and other non-fat-content-solids. Fat content is adjusted to meet compositional standards through removal, mixing, or addition of fat while solids content is adjusted through addition of milk powder, stabilizers, emulsifiers, and other substances, such as sweeteners and preservatives. These adjustments are subject to specific legislative regulations. After being standardized, milk is homogenized so as to obtain a less creamy effect and to prevent clumping leading to an improved appearance, texture, and viscosity. Then, the milk is briefly heated to kill off pathogens.

-

Culture Addition, Fermentation & AgeingLactic acid bacteria are added to the milk by mixing a pre-prepared culture of Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus into the milk. In some cases, other bacteria may be added to the culture to produce a specific type of yogurt. The milk and culture mixture is then placed in an incubation tank and maintained at the proper temperature for several hours. During this time, the bacteria ferment the lactose in the milk, producing lactic acid and thickening the milk into yogurt. The exact incubation time will vary depending on the temperature, the bacteria concentration, the type of yogurt being produced and the desired flavor and texture. Once the yogurt has thickened, it is cooled to 4°C or lower to slow the growth of the bacteria and to stabilize the yogurt. The cooled yogurt is then stored for several hours. As mentioned before, set yogurt is fermented after packaging, unlike other yogurt varieties.

-

Flavor Addition and PackingFlavorings, such as syrups or fruit pieces, can be added to the yogurt after it has been thickened and cooled using a mixer. This allows a more distinct layering of flavors and a better texture. Some flavorings can also be added to the milk and culture mixture before it is incubated to integrate with the yogurt mixture. Finally, the yogurt is packed in a variety of containers, including plastic cups, glass jars, or larger containers. This is done using parallel packing lines that can handle different types of yogurt products and packing options. During the packing process, the containers are filled with the desired yogurt, sealed and labeled with the product information required by law.

-

Quality Control Check & Cold StorageBefore reaching the consumers, the yogurt must pass a series of quality control checks to ensure that it meets quality standards, such as proper consistency, flavor, and appearance. The packaged yogurt is then stored in a temperature-controlled environment, below 10°C (usually between 2°C and 8°C), to maintain its quality until it is distributed to customers. This is typically done in a storage room or warehouse that is specifically designed for the storage of dairy products.

-

Distribution to CustomersThe yogurt is finally transported to retail stores or distribution centers, where it is made available for sale to consumers. Customers are either directly served by the company's refrigerated trucks or they use their own transportation methods.

- The planning horizon of interest divided into a set of time periods.

- A set of parallel packing lines and their available production time in each period.

- A set of batch recipes with minimum preparation time and specified production capacity.

- A set of products.

- A set of product families in which all products are grouped.

- Assignment suitability constraints between packing lines, products, recipes and product families.

- All production related parameters including production targets, production rates, minimum and maximum processing runs, cup weights, daily opening and shutdown times.

- The required sequence-dependent changeover operations whenever a new family is processed after a previous one in each processing unit, as long as the processing sequence is not forbidden.

- The required sequence-independent setup operations whenever a product is assigned to a processing unit.

- The cost coefficients associated with recipes preparation, unit operation, changeovers, inventory and external production.

- The assignment of product families to packing lines.

- The sequencing of product families in each packing line.

- The amount of every product produced in each processing unit.

- The production run length, starting and completion time for every product family.

- The amount of every product externally produced in a cooperating plant.

- The inventory level for every product in each time period.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. MILP model

- Products Lot-Sizing Constraints

- Constraints which impose lower and upper bounds on the produced amount of a product in each processing unit and in each period. The upper bound is either equal to the remaining demand until the end of the scheduling horizon, or to the maximum amount of product that can be processed by the packing line in the current period.

- Families Allocation Constraints

- Constraints which ensure that if at least one product that belongs to a specific family is processed on a unit in a period, then this family will be assigned to this unit in the same period.

- Constraints which ensure that a packing line is used in a time period if at least one family is assigned to it in for that particular time period.

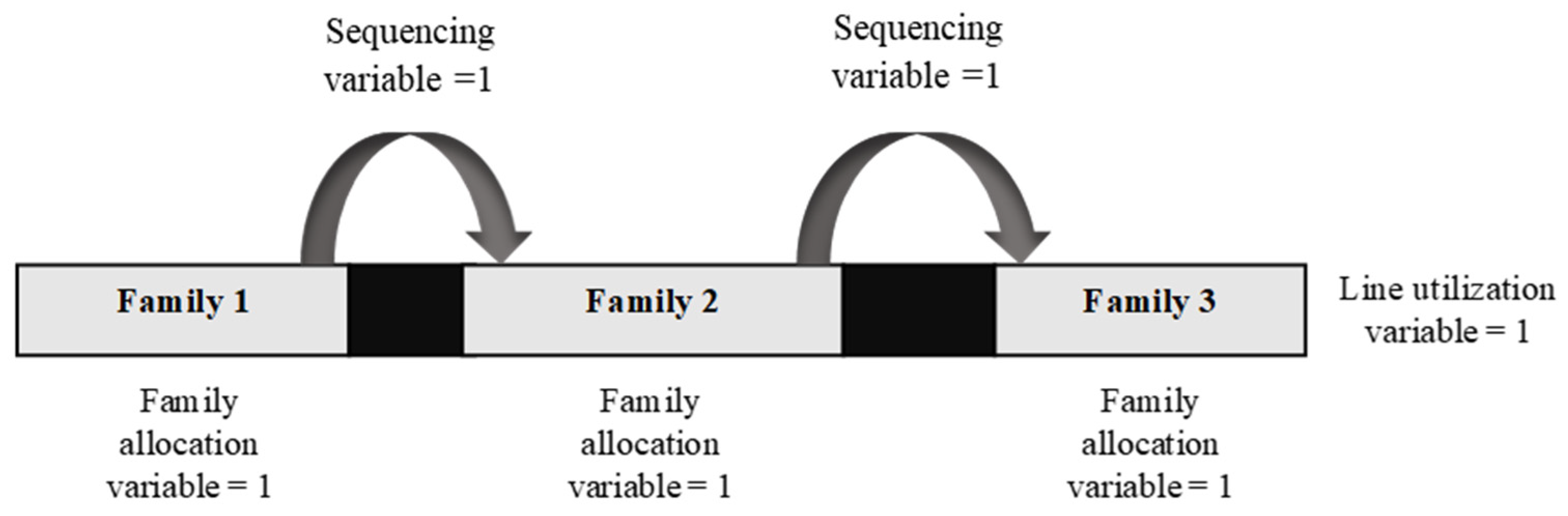

- Families Sequencing Constraints

- Constraints to establish that if a family is assigned to a specific processing unit during a period, then this family has at most one predecessor and one successor.

- Constraints that impose that the sum of the total active sequence binary variables and the binary variable which indicates whether a packing line is used, must equal the total number of active allocation variables in the packing line, in each time period. For example, if three families are produced in a packing line then there are three active allocation variables, two active sequence binary variables and an active binary line utilization variable, as shown in Figure 3.

- Families Timing Constraints

- Constraints that state that the starting time of processing a product family after another family in a unit, is greater than the sum of the completion time of the first family and the necessary changeover time between the families.

- Constraints that define a family’s processing time as the total processing time for all products that belong to the family plus the required set up times in order to process each product.

- Constraints which introduce lower and upper bounds in the families completion times. More specifically, the completion time of a family must be greater than the sum of the daily plant startup time, the minimum time for the fermentation recipe preparation, the family processing time and the necessary changeover time. Additionally, the completion time of a family must not exceed the available daily production horizon minus the daily shutdown time of the plant.

- Recipe Preparation Batch Stage Constraints

- Constraints which bound the total produced quantity of products between the minimum produced recipe amount and the maximum recipe production capacity.

- Constraints which guarantee that a recipe is produced in a time period if at least one family deriving from this recipe is processed in a packing line in the same time period.

- Mass Balance Constraints

- Constraints that ensure full demand satisfaction, under the expression that the inventory of a product at the end of a time period equals the previous time period inventory, plus the total internal and external production, minus the production targets of the period. The external production term demonstrates production realized to an affiliated production facility or the unsatisfied demand.

- Objective function

- The objective of the mathematical model is the minimization of the total production cost, which includes costs of storage, recipe preparation, packing line utilization, families changeovers, internal production and external production. The external production term demonstrates production realized to an affiliated production facility or the unsatisfied demand.

3.2. Commercial Scheduling tool (ScheduleProTM)

- 1.

- Declaration of recipes: Recipes contain information about the processing steps required to produce the final product. They consist of procedures which include operations that consume resources and produce the desired materials. Each procedure has its own equipment pool (processing units) where it can take place, while operations may also have auxiliary equipment or resources. The duration of each operation as well as its timing with respect to other tasks is declared. Whether the operation is interruptible or delayable should also be stated. This step also involves defining the standard recipe for each product to be manufactured.

- 2.

- Declaration of available equipment and resources: This involves identifying the available equipment, labor, storage, utilities etc. and the production capacity of each resource. Parallel use of equipment or resources and possible existing downtimes are also declared.

- 3.

- Declaration of production campaigns: This involves creating a campaign of recipes that define the batches that need to be produced. A release or due date for each campaign can be stated.

- 4.

- Schedule generation and modification: A production schedule that indicates when each batch will be produced, which resources will be used, and how long each step of the process will take, is automatically generated. The generated schedule can be inspected by the users through various tables and graphs, such as economic reports or the equipment occupancy chart, which helps to identify potential bottlenecks or scheduling conflicts. Moreover, resource graphs are also available to capture the consumption and inventory of resources such as materials and utilities against their availability. The generated schedule can be modified as needed to accommodate changes in production requirements, resource availability or other factors. Tracking the status of production as a function of time is possible, thus well-informed and timely decisions can be easily made to ensure that production objectives are met.

- First, the production facility and the scheduling horizon are identified and then, potential existing downtimes are declared. These downtimes can refer to weekends, plant setup and shutdown times, scheduled maintenance etc.

- All products in the plant are declared under the SKUs tab. Two SKU types are inserted, one containing the product families and one containing the fermentation recipes/formulas. The mapping between SKUs and types is also realized.

- The available equipment of the facility and its possible outages are added. The minimum and maximum capacity of fermentation tanks as well as which fermentation recipes they can produce are defined. For the packing lines, a setup time and a product-dependent rate is set. Moreover, a changeover matrix is inserted including the changeover time needed by each specific equipment for the sequential processing of two product families.

- Regarding the introduction of the production process, a single semi-continuous recipe is declared for all yogurt products. Note that this “recipe” refers to the production process and not to the fermentation recipes/formulas needed to prepare yogurts. This recipe consists of two procedures, one for the yogurt preparation stage and one for the packing stage. The main equipment responsible for the execution of each procedure is declared. The first procedure includes one operation, the actual fermentation process and the second procedure is further divided into three operations, one for the product-dependent changeover, one for the machine setup time and one for the filling process. An SKU-type-specific fixed duration is set for the fermentation operation, which is scheduled as the first operation to take place. The duration of changeover operations is set based on the equipment changeover times declared, with respect to the task before. This operation is scheduled to start with the end of the fermentation operation and a flexible time shift is added regarding the equipment availability. The duration of the setup operation is set equal to the equipment’s setup time and the operation is scheduled to start after the end of changeover operation. Finally, the duration of the filling operation is set as rate-based and it is equipment depended and scalable with batch size. This operation is scheduled right after the setup operation. The operation responsible for producing the final products is defined as the filling operation.

- To fulfill the facility’s pending orders, campaign projects are created for each day of the week. A campaign can be based on an SKU order template and specifies how many batches of each product need to be produced and within which time frame. It is noted that the order in which the campaigns are inserted has a major impact on the derived schedule, therefore extensive knowledge of the facility is required to obtain acceptable and near optimal schedules.

4. Results & Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Georgiadis, G.P.; Elekidis, A.P.; Georgiadis, M.C. Optimization-Based Scheduling for the Process Industries: From Theory to Real-Life Industrial Applications. Processes 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, C.A.; Cerdá, J.; Grossmann, I.E.; Harjunkoski, I.; Fahl, M. State-of-the-Art Review of Optimization Methods for Short-Term Scheduling of Batch Processes. Comput Chem Eng 2006, 30, 913–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondili, E.; Pantelides, C.C.; Sargent, R.W.H. A GENERAL ALGORITHM FOR SHORT-TERM SCHEDULING OF BATCH OPERATIONS-I. MILP FORMULATION. Comput Chem Eng 1993, 17, 21–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Maravelias, C.T. Combining the Advantages of Discrete-and Continuous-Time Scheduling Models: Part 3. General Algorithm. Comput Chem Eng 2020, 139, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulds, L.R.; Wilson, J.M. Scheduling Operations for the Harvesting of Renewable Resources. J Food Eng 2005, 70, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.; Abakarov, A. Optimal Scheduling of Canned Food Plants Including Simultaneous Sterilization. J Food Eng 2009, 90, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Li, J. Modeling, Analysis and Continuous Improvement of Food Production Systems: A Case Study at a Meat Shaving and Packaging Line. J Food Eng 2012, 113, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldo, T.A.; Santos, M.O.; Almada-Lobo, B.; Morabito, R. An Optimization Approach for the Lot Sizing and Scheduling Problem in the Brewery Industry. Comput Ind Eng 2014, 72, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polon, P.E.; Alves, A.F.; Olivo, J.E.; Paraíso, P.R.; Andrade, C.M.G. Production Optimization in Sausage Industry Based on the Demand of the Products. J Food Process Eng 2018, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, G.P.; Mariño Pampín, B.; Adrián Cabo, D.; Georgiadis, M.C. Optimal Production Scheduling of Food Process Industries. Comput Chem Eng 2020, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, G.P.; Elekidis, A.P.; Georgiadis, M.C. Optimal Production Planning and Scheduling in Breweries. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2021, 125, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sel, C.; Bilgen, B.; Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J.M.; van der Vorst, J.G.A.J. Multi-Bucket Optimization for Integrated Planning and Scheduling in the Perishable Dairy Supply Chain. Comput Chem Eng 2015, 77, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrup, M.L.; Günther, H.O.; Van Beek, P.; Grunow, M.; Seiler, T. Mixed-Integer Linear Programming Approaches to Shelf-Life-Integrated Planning and Scheduling in Yoghurt Production. Int J Prod Res 2005, 43, 5071–5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doganis, P.; Sarimveis, H. Optimal Scheduling in a Yogurt Production Line Based on Mixed Integer Linear Programming. J Food Eng 2007, 80, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopanos, G.M.; Puigjaner, L.; Georgiadis, M.C. Optimal Production Scheduling and Lot-Sizing in Dairy Plants: The Yogurt Production Line. Ind Eng Chem Res 2010, 49, 701–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wari, E.; Zhu, W. Multi-Week MILP Scheduling for an Ice Cream Processing Facility. Comput Chem Eng 2016, 94, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sel, Ç.; Bilgen, B.; Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J. Planning and Scheduling of the Make-and-Pack Dairy Production under Lifetime Uncertainty. Appl Math Model 2017, 51, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, G.P.; Kopanos, G.M.; Karkaris, A.; Ksafopoulos, H.; Georgiadis, M.C. Optimal Production Scheduling in the Dairy Industries. Ind Eng Chem Res 2019, 58, 6537–6550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, X.; Luo, J. Filling Process Optimization through Modifications in Machine Settings. Processes 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branke, J.; Nguyen, S.; Pickardt, C.W.; Zhang, M. Automated Design of Production Scheduling Heuristics: A Review. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2016, 20, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzella, F.; Morganti, G.; Ciaschetti, G. A Genetic Algorithm for the Flexible Job-Shop Scheduling Problem. Comput Oper Res 2008, 35, 3202–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.; Mei, Y.; Zhang, M. Genetic Programming for Production Scheduling: A Survey with a Unified Framework. Complex & Intelligent Systems 2017, 3, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantilis, C.D.; Kiranoudis, C.T. A Modern Local Search Method for Operations Scheduling of Dehydration Plants. J Food Eng 2002, 52, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.J.; Huang, J.X. Solving the Economic Lot Scheduling Problem with Deteriorating Items Using Genetic Algorithms. J Food Eng 2005, 70, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Pan, Q.K.; Gao, L. Production Scheduling for Blocking Flowshop in Distributed Environment Using Effective Heuristics and Iterated Greedy Algorithm. Robot Comput Integr Manuf 2021, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Chen, Y.; Mumtaz, J.; Ullah, S. Dynamic Mixed Model Lotsizing and Scheduling for Flexible Machining Lines Using a Constructive Heuristic. Processes 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemkhani, A.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R.; Rahimi, Y.; Shahnejat-Bushehri, S.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, H. Integrated Production-Inventory-Routing Problem for Multi-Perishable Products under Uncertainty by Meta-Heuristic Algorithms. Int J Prod Res 2022, 60, 2766–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, F.; Demartini, M.; Arezza, A.; Tonelli, F.; Pacella, M.; Papadia, G. An Agent-Based Approach for Make-To-Order Master Production Scheduling. Processes 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommadath, R.; Maharana, D.; Anandalakshmi, R.; Kotecha, P. Multi-Objective Scheduling in the Vegetable Processing and Packaging Facility Using Metaheuristic Based Framework. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2023, 137, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjunkoski, I.; Maravelias, C.T.; Bongers, P.; Castro, P.M.; Engell, S.; Grossmann, I.E.; Hooker, J.; Méndez, C.; Sand, G.; Wassick, J. Scope for Industrial Applications of Production Scheduling Models and Solution Methods. Comput Chem Eng 2014, 62, 161–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulouris, A.; Misailidis, N.; Petrides, D. Applications of Process and Digital Twin Models for Production Simulation and Scheduling in the Manufacturing of Food Ingredients and Products. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2021, 126, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumi, A.; Jürgens, C.; Jungo, C.; Maier, B.A.; Papavasileiou, V.; Petrides, D.P. Design and Optimization of a Large Scale Biopharmaceutical Facility Using Process Simulation and Scheduling Tools. Pharmaceutical Engineering 2010, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Koulouris, A.; Siletti, C.A.; Petrides, D.P. Throughput Analysis of Biochemical and Pharmaceutical Batch Processes with Simulation and Scheduling Tools. Computer Aided Chemical Engineering 2004, 18, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulouris, A.; Kotelida, I. Simulation-Based Reactive Scheduling in Tomato Processing Plant with Raw Material Uncertainty. Computer Aided Chemical Engineering 2011, 29, 1020–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, A.; Kendrik, D.; Meeraus, A.; Raman, R.; Rosenthal, R.E. GAMS-A User’s Guide. GAMS Software GmbH Eupener 1998. [CrossRef]

- Papavasileiou, V.; Koulouris, A.; Siletti, C.; Petrides, D. Optimize Manufacturing of Pharmaceutical Products with Process Simulation and Production Scheduling Tools. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2007, 85, 1086–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Recipe | Fermentation time (hr) | Min quantity (kg) | Cost (€) |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | 4.75 | 1200 | 545 |

| R2 | 4.5 | 1200 | 540 |

| R3 | 8.25 | 1200 | 565 |

| R4 | 7.75 | 1200 | 555 |

| R5 | 5.25 | 1200 | 525 |

| R6 | 7.25 | 1200 | 565 |

| R7 | 8.75 | 1200 | 625 |

| R8 | 1.5 | 0 | 505 |

| R9 | 1.5 | 0 | 510 |

| R10 | 1.5 | 0 | 515 |

| R11 | 8.75 | 1200 | 625 |

| R12 | 8.75 | 1200 | 600 |

| Recipe | Fermentation time (hr) | Min quantity (kg) | Max quantity (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | 8.50 | 3500 | 52222 |

| R2 | 7.50 | 3500 | 52222 |

| R3 | 7.50 | 3500 | 52222 |

| R4 | 6.00 | 3500 | 52222 |

| R5 | 6.50 | 3500 | 36000 |

| R6 | 1.00 | 3500 | 30000 |

| R7 | 7.50 | 3500 | 52222 |

| R8 | 8.50 | 3500 | 36000 |

| R9 | 8.50 | 3500 | 36000 |

| R10 | 13.50 | 3500 | 36000 |

| R11 | 7.50 | 3500 | 52222 |

| R12 | 1.00 | 3500 | 30000 |

| R13 | 8.50 | 3500 | 36000 |

| R14 | 8.50 | 3500 | 36000 |

| R15 | 1.00 | 3500 | 30000 |

| R16 | 1.00 | 3500 | 30000 |

| Line | Setup time (hr) | Shutdown time (hr) | Available production time (hr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| J1 | 0.13 | 1.33 | 22.54 |

| J2 | 0.13 | 1.33 | 22.54 |

| J3 | 0.13 | 1.50 | 22.37 |

| J4 | 0.13 | 1.67 | 22.20 |

| J5 | 0.13 | 1.67 | 22.20 |

| J6 | 0.13 | 1.67 | 22.20 |

| J7 | 0.13 | 1.67 | 22.20 |

| (A) KRI-KRI | (B) TYRAS | |

|---|---|---|

| Products | 93 | 176 |

| Recipes | 12 | 16 |

| Families | 23 | 41 |

| Fermentation tanks | 15 | 12 |

| Packing lines | 4 | 7 |

| Scheduling horizon in days | 5 | 7 |

| Case | Details |

|---|---|

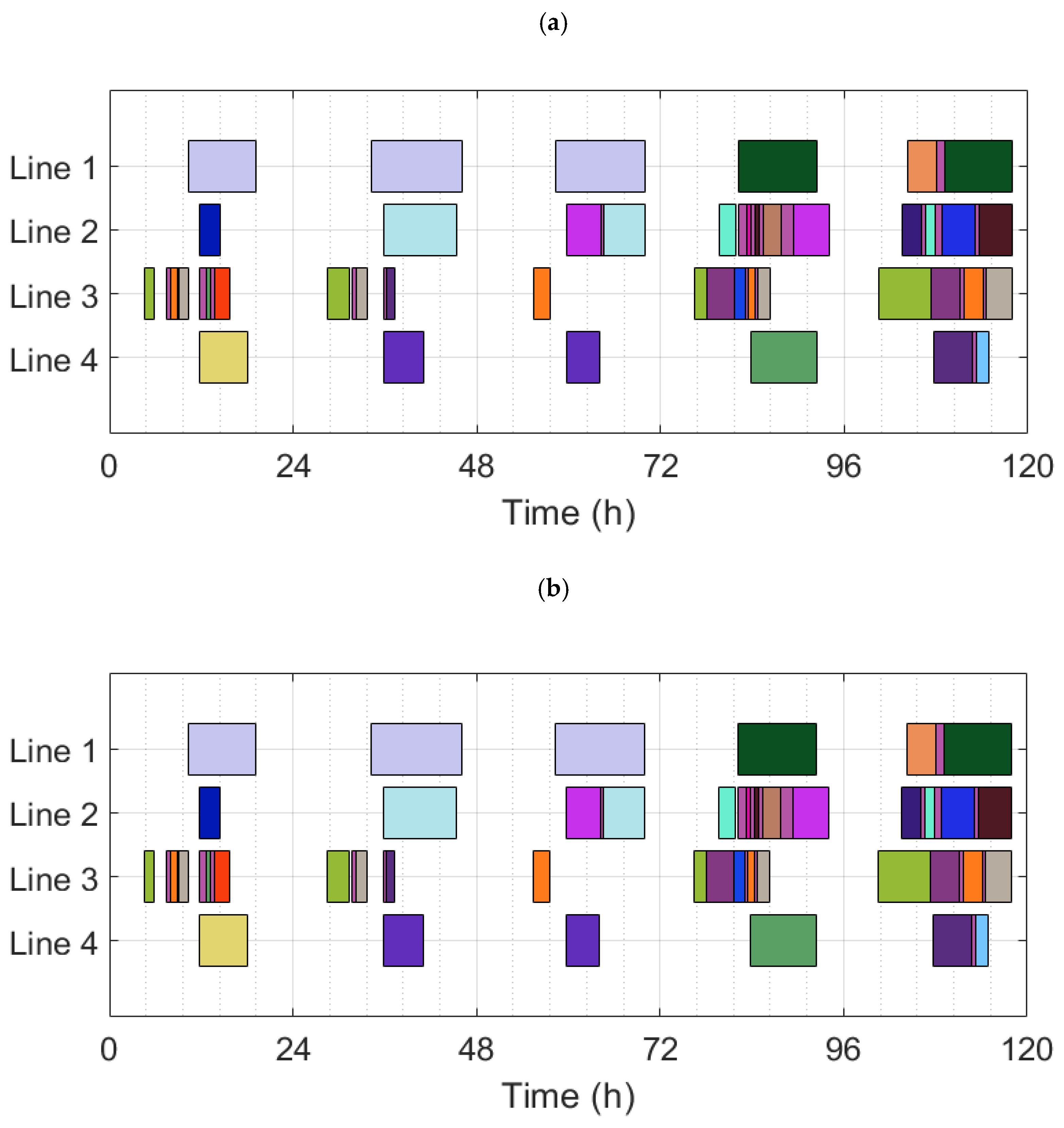

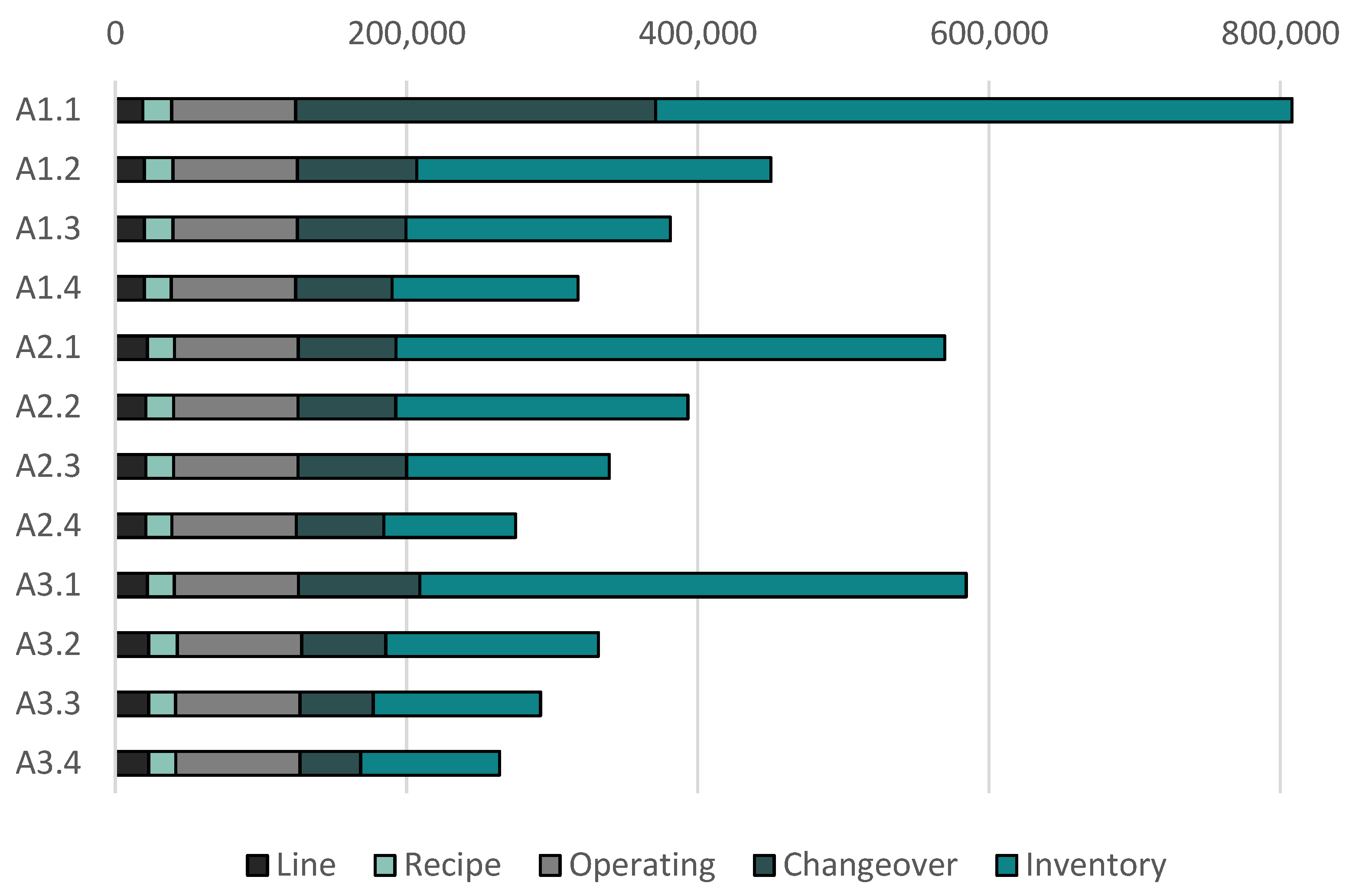

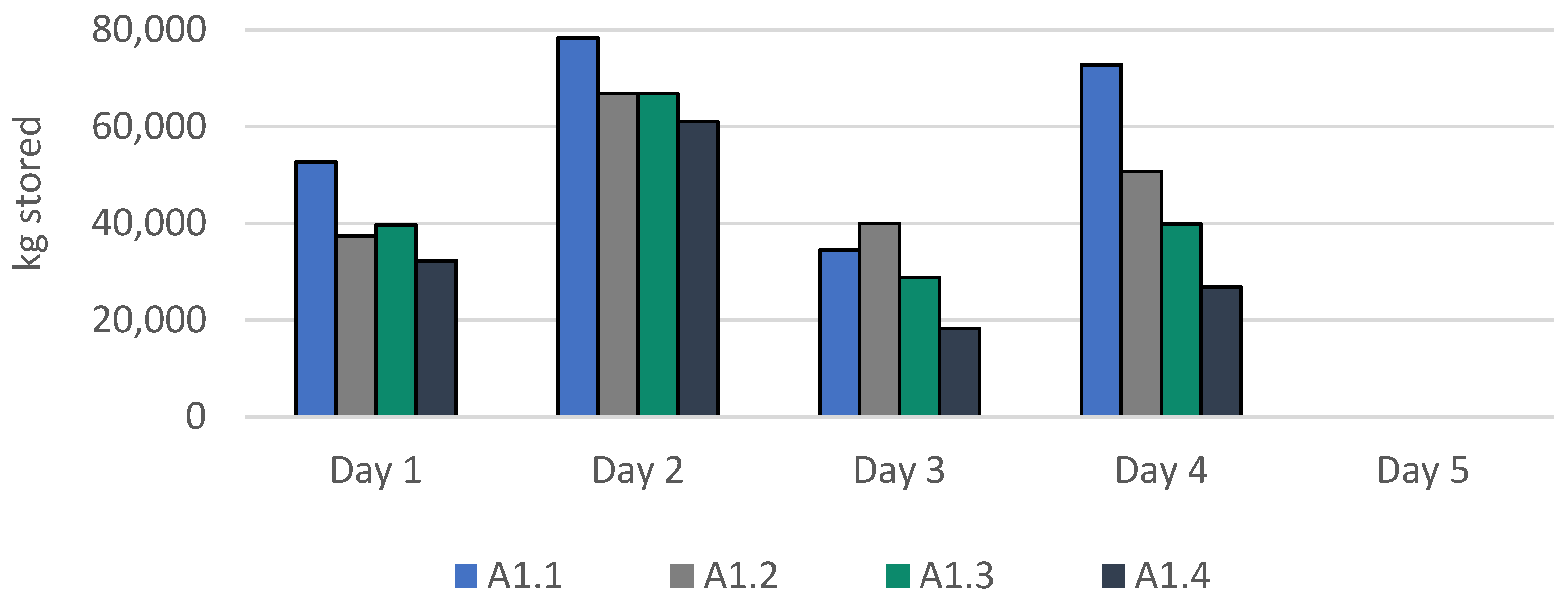

| A1 | Basic scenario for KRI-KRI facility |

| A1.1 | A1 solved using a random sequence of production orders in ScheduleProTM |

| A1.2 | A1 solved using the given families relative sequence of production in ScheduleProTM |

| A1.3 | A1 solved using an experience-based sequence of production orders in ScheduleProTM |

| A1.4 | A1 solved using the MILP model |

| A2 | Addition of an extra packing line identical to line 1 in KRI-KRI facility |

| A2.1 | A2 solved using a random sequence of production orders in ScheduleProTM |

| A2.2 | A2 solved using the given families relative sequence of production in ScheduleProTM |

| A2.3 | A2 solved using an experience-based sequence of production orders in ScheduleProTM |

| A2.4 | A2 solved using the MILP model |

| A3 | Addition of an extra packing line identical to line 2 in KRI-KRI facility |

| A3.1 | A3 solved using a random sequence of production orders in ScheduleProTM |

| A3.2 | A3 solved using the given families relative sequence of production in ScheduleProTM |

| A3.3 | A3 solved using an experience-based sequence of production orders in ScheduleProTM |

| A3.4 | A3 solved using the MILP model |

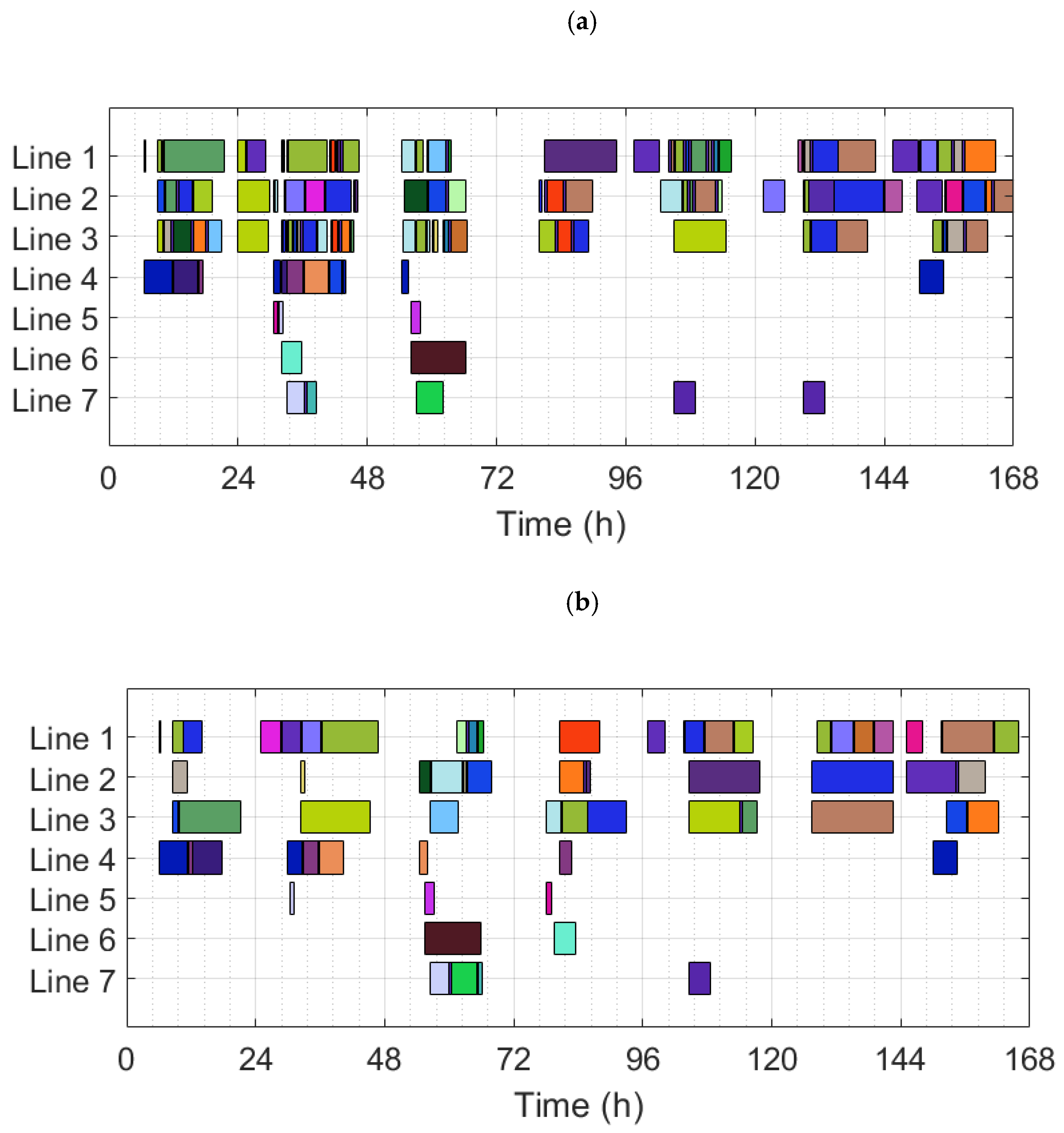

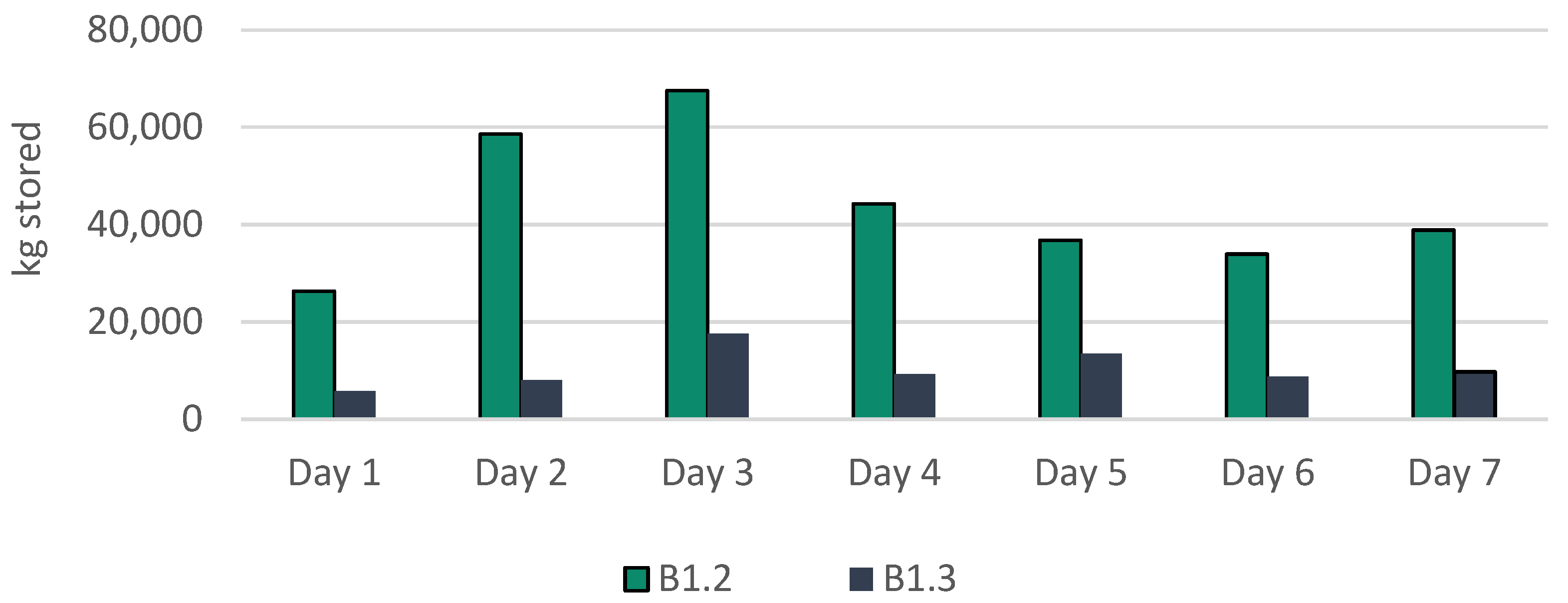

| B1 | Basic scenario for TYRAS facility |

| B1.1 | B1 solved using a random sequence of production orders in ScheduleProTM |

| B1.2 | B1 solved using an experience-based sequence of production orders in ScheduleProTM |

| B1.3 | B1 solved using the MILP model |

| B2 | Addition of an extra packing line identical to line 2 in TYRAS facility |

| B2.1 | B2 solved using a random sequence of production orders in ScheduleProTM |

| B2.2 | B2 solved using an experience-based sequence of production orders in ScheduleProTM |

| B2.3 | B2 solved using the MILP model |

| Line | Families Relative Sequence | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J1 | F20 → | F21 → | F22 | |||||||

| J2 | F12 → | F11 → | F19 → | F18 → | F13 → | F14 → | F15 → | F16 → | F17 | |

| J3 | F01 → | F02 → | F03 → | F05 → | F04 → | F08 → | F09 → | F10 → | F06 → | F07 |

| J4 | F08 → | F09 → | F10 → | F06 → | F23 | |||||

| Case |

Production Cost (€) | Improvement (%) |

Weekly Makespan (hr) | Avg Daily Makespan (hr) | Cmax (hr) |

CPU (s) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A1.1 | 808094 | - | 117.28 | 21.67 | 21.90 | 1.32 |

| A1.2 | 450206 | 44.3 | 116.62 | 21.41 | 21.95 | 1.08 | |

| A1.3 | 381223 | 52.8 | 116.62 | 21.41 | 21.95 | 1.04 | |

| A1.4 | 317852 | 60.7 | 118.00 | 21.44 | 22.00 | 1.87 | |

| A2 | A2.1 | 569604 | - | 117.28 | 21.27 | 21.85 | 1.13 |

| A2.2 | 393266 | 31.0 | 116.47 | 21.08 | 21.95 | 1.07 | |

| A2.3 | 339213 | 40.4 | 116.47 | 20.60 | 21.95 | 1.10 | |

| A2.4 | 274961 | 51.7 | 118.00 | 21.10 | 22.00 | 2.06 | |

| A3 | A3.1 | 584415 | - | 115.78 | 21.37 | 21.89 | 1.19 |

| A3.2 | 331795 | 43.2 | 116.62 | 21.13 | 21.82 | 1.02 | |

| A3.3 | 292084 | 50.0 | 116.62 | 21.13 | 21.82 | 1.07 | |

| A3.4 | 263951 | 54.8 | 118.00 | 21.22 | 22.00 | 1.97 |

| Type of cost | Amount |

|---|---|

| Line utilization | 1000 € / line and day of operation |

| Recipe preparation | Recipe cost (Table 1) / recipe and day used |

| Operating | 500 € / hr of operation of line |

| Changeover | Changeover cost (Table S4) / type of changeover |

| Inventory | Inventory cost (Table S2) / kg of product stored |

| Initial capacity | Extra line identical to line 1 | Extra line identical to line 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1.1 | (A2.1) | -29.5% | (A3.1) | -27.7% |

| A1.2 | (A2.2) | -12.6% | (A3.2) | -26.3% |

| A1.3 | (A2.3) | -11.0% | (A3.3) | -23.4% |

| A1.4 | (A2.4) | -13.5% | (A3.4) | -17.0% |

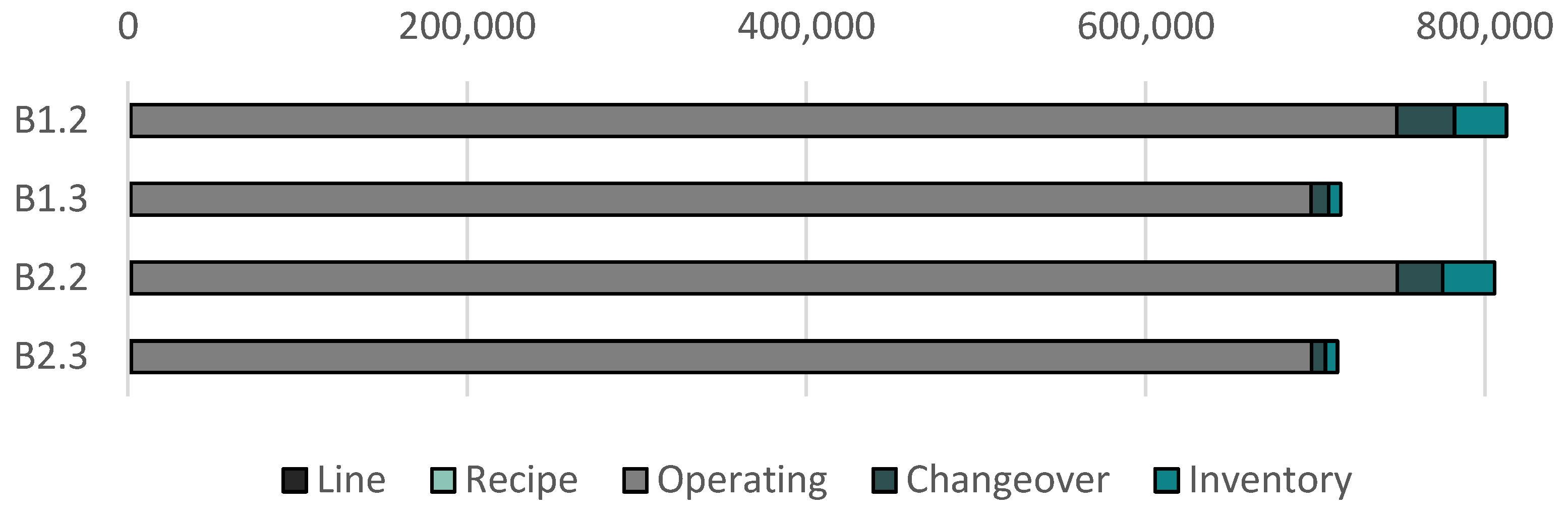

| Case |

Production Cost (€) | Improvement (%) |

Weekly Makespan (hr) | Avg Daily Makespan (hr) | Cmax (hr) |

CPU (s) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B1.1 | - | Infeasible | - | - | - | - |

| B1.2 | 812646 | - | 165.30 | 21.17 | 22.60 | 0.87 | |

| B1.3 | 715075 | 12.0 | 165.97 | 21.60 | 22.67 | 144.29 | |

| B2 | B2.1 | - | Infeasible | - | - | - | - |

| B2.2 | 805625 | - | 164.72 | 21.12 | 22.47 | 0.87 | |

| B2.3 | 713112 | 11.5 | 165.72 | 20.95 | 22.67 | 269.61 |

| Type of cost | Amount |

|---|---|

| Line utilization | 50 € / line and day of operation |

| Recipe preparation | - |

| Operating | 2 € / kg of product produced |

| Changeover | 1300 € / hour of changeover |

| Inventory | 0.1 € / kg of product stored and day |

| Initial capacity | Extra line identical to line 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| B1.2 | (B2.2) | -0.86% |

| B1.3 | (B2.3) | -0.27% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).