1. Introduction

Hemoperfusion, an extracorporeal blood purification technique, could remove endogenous or exogenous toxins through direct contact of porous adsorbents with blood drawn from the body to relieve symptoms, and even cure diseases, which have been widely used in the treatment of acute poisoning [

1], hyperlipidemia [

2], acute hepatitis [

3], sepsis [

4], and uremia [

5]. The technical core of hemoperfusion was adsorbents determining the treatment effect [

6,

7,

8]. Activated carbon (AC), a kind of granular or powdery material obtained by high temperature carbonization activation, is one of the commonly used broad-spectrum adsorbents for various toxins removal with greater mechanical strength, high specific surface area and large pore volume, which showed the adsorption capacity of creatinine. As early as 1964, Yatzidis et al used activated carbon as a hemoadsorbent with strong adsorption efficiency for creatinine, uric acid, phenols, indole, salicylic acid, barbiturates, and glutethimide [

9]. Although AC has excellent adsorption performance due to its porosity and high specific surface area, poor blood compatibility limits its further clinical application [

8,

10]. The biocompatibility of AC could be improved by coating some biopolymers with good biocompatibility, such as collodion-albumin [

11,

12,

13], dextran [

14], zwitterionic hydrogel [

15], poly(ether sulfone) [

16] and so on. Coating could reduce the shedding of carbon particles into blood, reducing damage to red blood cells and the occurrence of carbon thrombosis. However, the hemocompatibity and poor selectivity of AC absorbents is required to improve further due to the complex coagulation process, and the nano- and mesopores would be also blocked after encapsulation, resulting in the reduction of adsorption capacity.

Heparin, a linear polysaccharide, has been widely used as an anticoagulant. Unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low molecular weight heparin (LWMH) can be administered by intravenous or subcutaneous injection to reduce the risk of coagulation in clinic [

17,

18]. Unfractionated heparin is a kind of aminodextran sulfate extracted and refined from porcine intestinal mucosa or bovine lung, and is a mixture ranging in molecular weight from approximately 16000 Da [

19]. Low molecular weight heparin prepared by controlled chemical or enzymatic depolymerization of UFH, is a fragment of aminodextran sulfate with a molecular weight range of 3000-5000 Da [

18]. The anticoagulant mechanisms of heparins with different molecular weights are also different. Both UFH and LWMH can bind to antithrombin through the pentasaccharide sequence to play the role of anti-coagulation factors [

20,

21], but the coagulation factors that can be inhibited are different due to the different lengths of the heparin chains [

22,

23]. After combining with antithrombin III, UFH with larger molecular weight can inhibit coagulation factors Xa and IIa, while LWMH with smaller molecular weight can increase the affinity with coagulation factor Xa, and mainly play the role of anticoagulation factor Xa [

24]. Compared with UFH, LMWH has lower binding to plasma proteins, platelets, and endothelial cells, longer half-life and more predictable anticoagulant response, with lower number of side effects and incidence of bleeding complications [

25,

26,

27]. Because of the anticoagulation and rich functional groups of heparin, surface heparinization have been paid much attention for the improvement of blood compatibility, aiming to the amount of anticoagulation and some side effects. Heparin could be attached to materials by coating [

28], LbL assembly [

29], grafting [

30], and mussel-inspired surface coating [

31,

32]. And a great amount of reports have proved that surface heparinization could improve the blood compatibility of blood-contact materials [

33,

34,

35]. However, there was no much attention to the differences between different molecular weight heparinized surfaces to improve hemocompatibility.

In addition, heparin as a linear polymer with a large negative charge could be used to improve the adsorption selectivity of target toxin [

36,

37]. Creatinine is a product of muscle metabolism in the human body, mainly excreted from the body through glomerular filtration. When the kidneys were in chronic or acute dysfunction, the concentration of creatinine in the blood was increased, ultimately leading to renal failure. So, the creatinine has been found to be a fairly reliable indicator of renal function. In clinic, the removal of creatinine by hemodialysis and hemoperfusion was one of the effective methods for treating renal failure. It was reported that heparin immobilized on graphene oxide presented outstanding removal of uremic toxins (urea, creatinine and phosphorous) after 4 h by hemodialysis [

38]. So, what is the kinetic adsorption mechanism of creatinine on heparinized surfaces and would the adsorption of creatinine be affected by the molecular weight of heparin?

Based on above, UFH or LWMH was covalently grafted on the surface of AC, aiming to improve the blood compatibility and creatinine adsorption of the adsorbent. The absorbents were then characterized by FTIR, SEM, XPS, TA and BET to evaluate the immobilized process and retention of nano- and mesopores. Then, the protein adsorption, clotting time, platelet activation and blood cell assay in vitro were evaluated to investigate the differences between UFH and LWMH modified surfaces in improving blood compatibility. Finally, the adsorption capacity of creatinine and the kinetic adsorption were calculated by UV-Vis spectrophotometer and fitting, respectively. This study was expected to provide a basis for better improving the blood compatibility and adsorption of AC in blood purification.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Activated carbon (AC) were provided by Shenzhen Global Green New Materials Co., Ltd. Polyethyleneimine (MW=600 Da), 1-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC), N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Unfractionated heparin and low molecular weight heparin (Enoxaparin sodium) were purchased from Shenzhen Hepalink Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), phosphate buffered saline (PBS), bovine serum albumin (BSA), fibrinogen (FBG) and Micro BCA Protein Assay Reagent kit were obtained from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.. Creatinine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai) Trading Co. Ltd.

2.2. Preparation of AC- UFH and AC-LMWH

50 g AC was immersed into 300 mL citrate buffer solution (pH=4.7, 0.2 M Na2HPO4 and 0.1 M citric acid) containing EDC and NHS (molar ratio=2:1) for 1 h at 37℃ to obtain the carboxyl-activated AC. Then 3.0 g PEI (600 MW) was added into above mixture with continuous reaction at 37℃. After 24 h, the modified AC was filtered by vacuum, and washed 3 times alternately with deionized water and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH=7.0). Finally, the modified AC was dried at 65℃ for 24 h, and named as AC-PEI.

Unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin was added into citrate buffer solution (pH=4.7) containing EDC and NHS (molar ratio=2:1) for 1 h to activated carboxyl. Subsequently, AC-PEI was immersed into 3mg/mL unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin solution and shaken at 37℃ for 24 h to obtain AC-UFH or AC-LMWH. Then heparinized AC was washed by 4 M NaCl solution to remove the ionically and physically adsorbed heparin, followed by washing 3 times alternately with deionized water and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH=7.0). Finally, AC-UFH or AC-LMWH was dried by vacuum filtration and oven at 65℃.

2.3. Characterization

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, K-Alpha+, Thermo Scientific, US) is used to characterize the elemental composition of materials. The Al Kα excitation source (hυ=1486.6 eV) was used, the test area was 500 μm, and the test pressure was <10-7 Pa. The morphologies of the fabricated materials were examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM-7800F, JEOL Ltd.) at an accelerating voltage of 5.00 kV. The mechanical strength of absorbents was measured by Texture analyzer (TA, TA.XTC-20, Bosintech, Shanghai) with 10 tests for each sample by speed of 0.2 mm/s. Specific surface area and pore volume of absorbents were characterized by a surface area analyzer (BELSORP-max, MicrotracBEL, Japan)

2.4. Hemocompatibility

100 mg samples were balanced in normal saline for 2 h, and incubated with 1.0 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA) or FBG solution at 37℃. After 2 h, the samples were washed slightly with normal saline for 3 times, followed by eluted with 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 37℃ for 2 h to make the adsorbed protein fall off into the solution. Finally, the protein concentration in the elution was determined using the Micro BCATM Protein Assay Reagent Kit (Solarbio) and microplate reader (Multiskan FC, Thermo Scientific, US).

Blood sample was rabbit blood anticoagulated with sodium citrate (1:9). Platelet poor plasma (PPP) was obtained by centrifuging blood at 1500 rpm for 10 minutes. AC, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH were immersed in PPP at 37℃ for 2 h, and the control was untreated PPP. APTT was measured by automated coagulation analyzer (CA620, Sysmex, Japan).

All samples were respectively incubated with anticoagulant blood at 37℃ shaken with 60r/min. The control was blood without contact with materials. After 1 h, the blood was centrifuged with 1500g for 10min, and upper plasma (PPP) was taken, and measured according to rabbit blood platelet globulin (β- TG) ELISA test kit (Cusabio, Wuhan) operation. The OD value was measured at 450 nm by microplate reader (Versa Max, Molecular Devices, US).

The samples were respectively incubated with anticoagulant blood at 37℃. After incubated 1 h, the white cells, red cells and platelet was counted by blood cell analyzer (pocH 100iVD, Sysmex, Japan).

2.5. Adsorption experiments

AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH microspheres were balanced in PBS (50 mM, pH=7.4) for 30 min at room temperature before the adsorption experiment.

Creatinine was dissolved into PBS to prepare standard solution with the range of creatinine concentration of 0-0.1 mg/mL. The absorbance of creatinine solution was determined by a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Nanodrop one, Thermo Scientific, US.) at the wavelength of 235 nm to obtain the calibration curve.

The microspheres were respectively immersed into 0.1 mg/mL creatinine solution and shaken for 2 h at room temperature (25 ± 2℃). The amount of creatinine adsorption was evaluated by the initial concentration and final concentration. And the amount of creatinine adsorption at different time was monitored by a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Nanodrop one, Thermo Scientific, US.) at the wavelength of 235 nm. The concentration of creatinine adsorption at various stages was calculated by the calibration curve.

Kinetic adsorption equations of AC, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH were established through the monitoring and recording of endotoxin concentrations in different time periods, and the adsorption data were fitted and analyzed by pseudo-first-order kinetic equation and pseudo-first-order kinetic equation as following:

Pseudo-first-order kinetic equation:

Pseudo-first-order kinetic equation

where

was the adsorption amount of creatinine at some time (mg/g),

was the adorption amount of creatinine at equilibrium (mg/g),

and

were the rate constants of pseudo-first-order kinetic equation and pseudo-first-order kinetic equation, respectively.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The data in the experimental results were expressed by mean ± SD, and were statistically analyzed by GraphPad Prism 6 software with one way ANOVA method. The data had significant difference when p<0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of AC

Although Shenzhen Global Green New Materials Co., Ltd. kept the specific method of preparing AC confidential, it was known that the AC was obtained from styrene divinylbenzene resin treated through high temperature carbonization, impact removal, high temperature activation, impact removal and drying.

In the process of high temperature carbonization, the groups of styrene divinylbenzene resin would be cracked and rearranged to form new organic structural groups. With the increase of carbonization treatment temperature, these organic structural groups would gradually transform to the direction of forming graphite microcrystals, leading to changes in the functional groups and composition of carbonized products. Therefore, it was necessary to characterize its structural groups before the modification of AC, which was beneficial to provide a basis for subsequent modification.

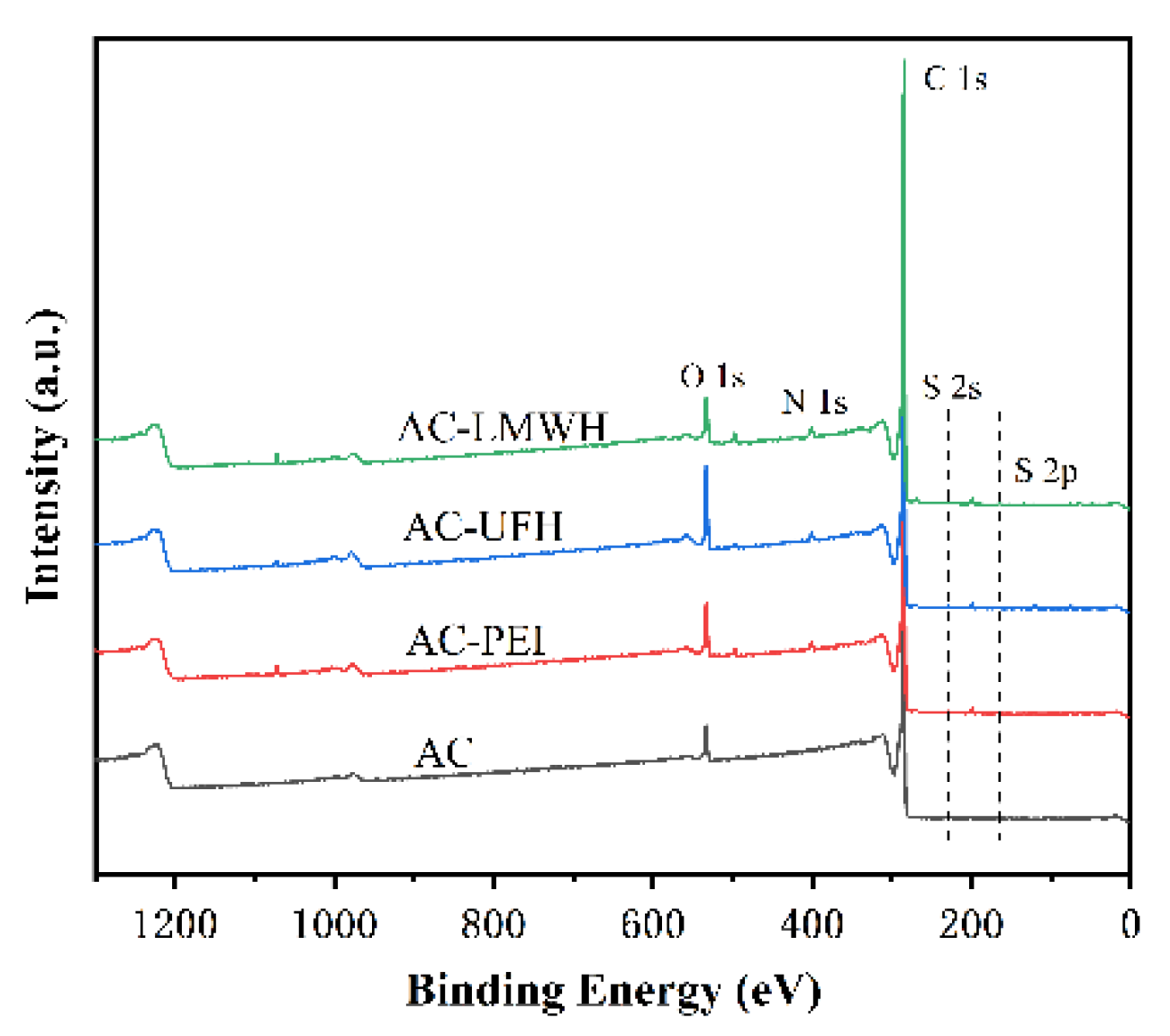

The structure and composition of AC would be calculated by X-ray electron spectroscopy, as shown in

Figure 1.

Table 1 showed chemical valence distribution and content proportion of C1s and O 1s. The results indicated that the AC obtained from high temperature carbonization and activation of styrene divinylbenzene resin had a certain amount of -COOH, which could provide the reactive sites for modification. However, the percentage of -COOH was limited, and the reactive sites could be amplified by the introduction of spacers with rich functional groups, which could decrease the steric hindrance during the grafting of heparin.

3.2. Preparation and characterization of AC-UFH and AC-LWMH

Surface modification is an effective means to endow materials with specific properties by adding or changing the chemical structure or composition of the surface. In order to increase the reactive sites, PEI was used to modify the AC through EDC/NHS chemical coupling reaction to provide rich amino group. In the same way, the UFH or LMWH was grafted onto AC-PEI to obtain the AC-UFH or AC-LMWH.

Figure 1 showed the XPS spectrum of each microsphere, and the analysis is carried out in combination with the element percentage of each sample, as shown in

Table 2. It could be seen that there were peaks at 285.1 eV and 532.1eV of AC microspheres, corresponding to the binding energy of C 1s and O 1s, respectively. And the C and O content of AC were 95.65% and 4.07%, respectively. It indicated that the AC was composed of carbon skeleton (C-C/C=C), and a certain amount of oxygen-containing group, such as -COOH, -OH, etc. (

Table 1). The existence of S element in AC microspheres was due to the residual organic reagents in the synthesis of styrene divinylbenzene microspheres before carbonization. After introduction PEI, a new peak of AC-PEI was appeared at 400.1 eV, corresponding to the binding energy of N 1s, and the N content was increased to 1.88%, demonstrating that the PEI was introduced on AC surface successfully. After the modification with heparin, the O and S content of AC-UFH was increased to 8.32% and 0.36%, indicating that heparin was modified with AC successfully. And AC-LMWH was increased to 5.99% and 0.35%, which was not obviously changed.

In order to evaluate the composition of surface, three point was selected randomly to detect using EDS, as shown in

Table 3. It could be seen that the O and S content of AC-UFH and AC-LMWH surface was significantly increased compared with AC, and the standard deviation was lower, indicating that the UFH and LMWH was modified uniformly on AC surface successfully.

Besides, there was the difference between the O content of AC-UFH and AC-LMWH, and the O content of AC-UFH was higher than that of AC-LMWH, which might be attributed to the steric hindrance of heparin grafting and the longer molecular chain of unfractionated heparin.

After a series of modification processes, whether the microspheres could maintain their original morphology and some of their own characteristics was important for practical application.

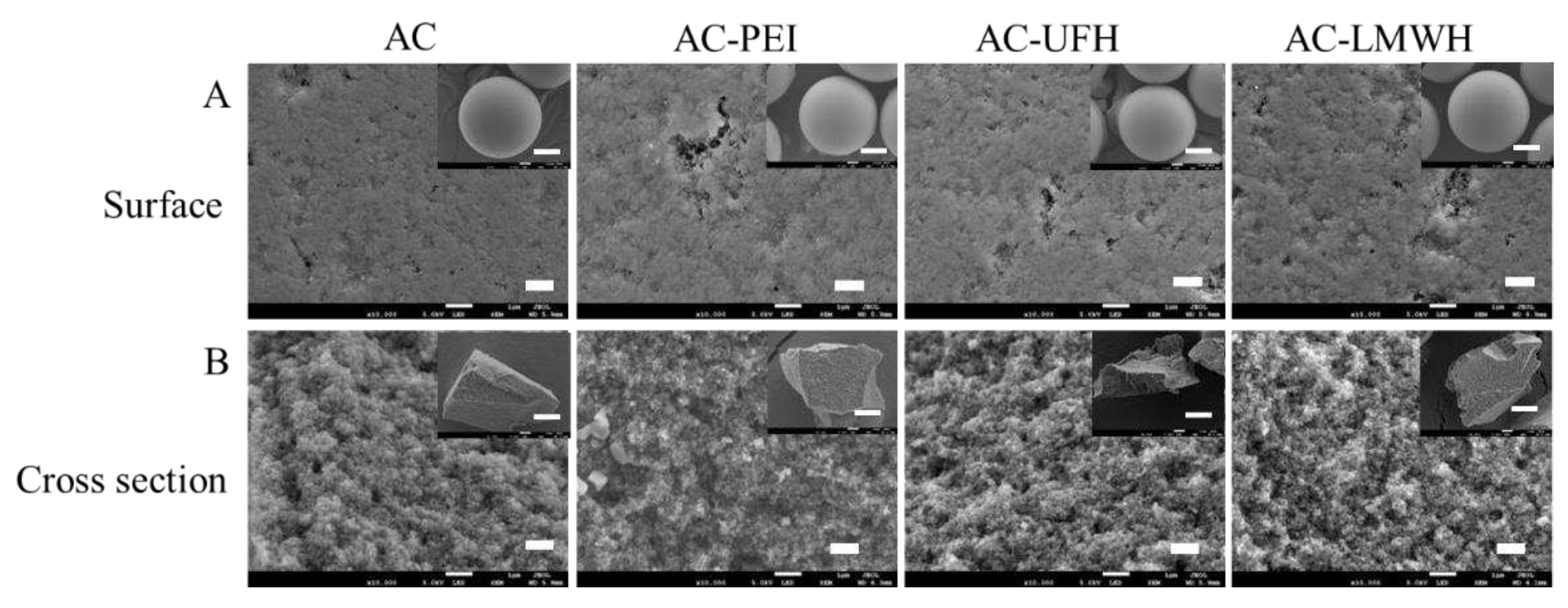

Figure 2 showed the scanning electron microscope images of the morphology of each sample. It could be seen from

Figure 2A that the particle size of microspheres was mainly focused on 500-600 μm, and AC had complete microsphere shape and rich internal channels. Compared with AC, the surface morphology of AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH kept original morphology and was unbroken after a series of reactions. The internal structure can be observed from the cross section of the microsphere, and the modified microspheres maintained the abundant channels and pore structure inside. These results demonstrated that the microspheres could keep the integrity, original morphology and rich pore structure after a series modification.

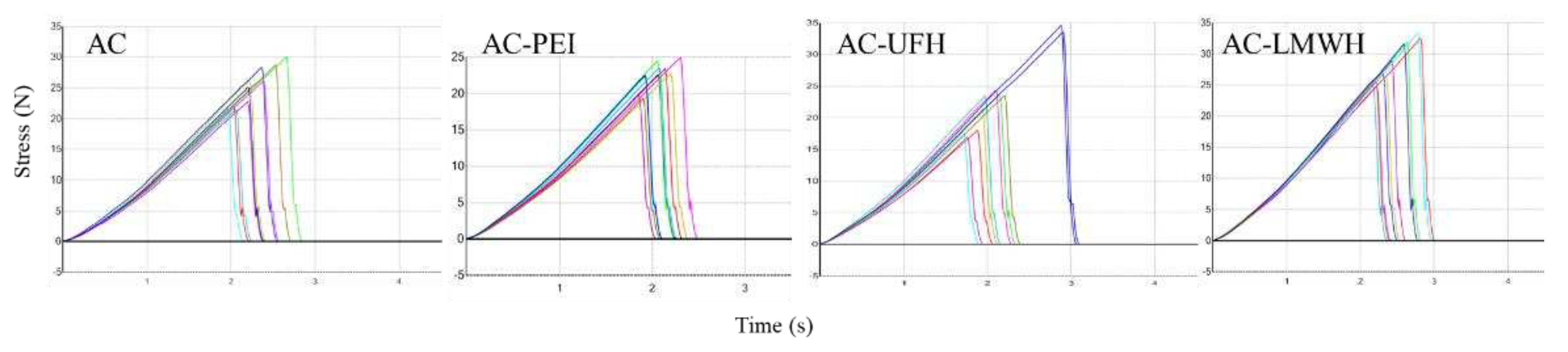

The adsorbent with better mechanical strength could prevent the rupture and particle shedding during the blood perfusion process resulting in thrombosis, and the mechanical strength should be kept during the modification process. The mechanical strength of AC and modified-AC was calculated by the texture curve, as shown in

Figure 3, and

Table 4 showed the first peak force of materials. The first peak force of AC was about 25.28 N, and was not changed obviously during the modification, indicating that modified-AC maintains the original mechanical strength. Carboxylic amine condensation reaction adopts EDC/NHS coupling reaction, which is a simple and mild modification method. The reaction can be completed in the buffer solution with pH=4.7, which had no significant effect on the mechanical strength of the material.

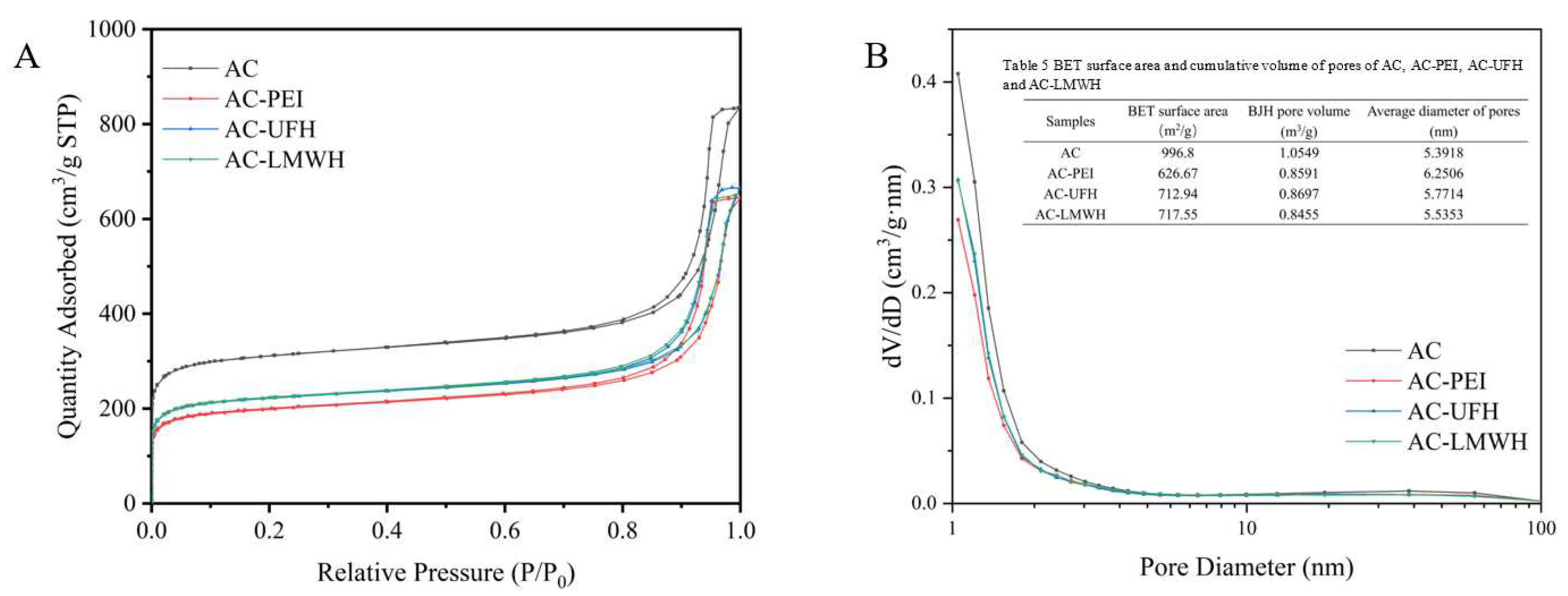

Figure. 4 displayed the nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherm and corresponding pore size distribution of the samples. It could be seen that the isotherm of AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH raised slower compared with AC in the area of low P/P

0, indicating the decrease of the surface area of AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH. Besides, the hysteresis loop on the isotherm of modified materials were not significantly changed compared with AC, indicating that grafting PEI or heparin did not significantly affect the mesopore volume of AC. The pore size distribution curves of AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH were displayed in

Figure 4(B), it shown that the reduction of pore volume due to graft PEI/heparin was mainly concentrated in micropores (<2 nm). The textural property of AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH was illustrated in

Table 5 (inserted in Figure. 4(B)).

3.3. Hemocompatibility

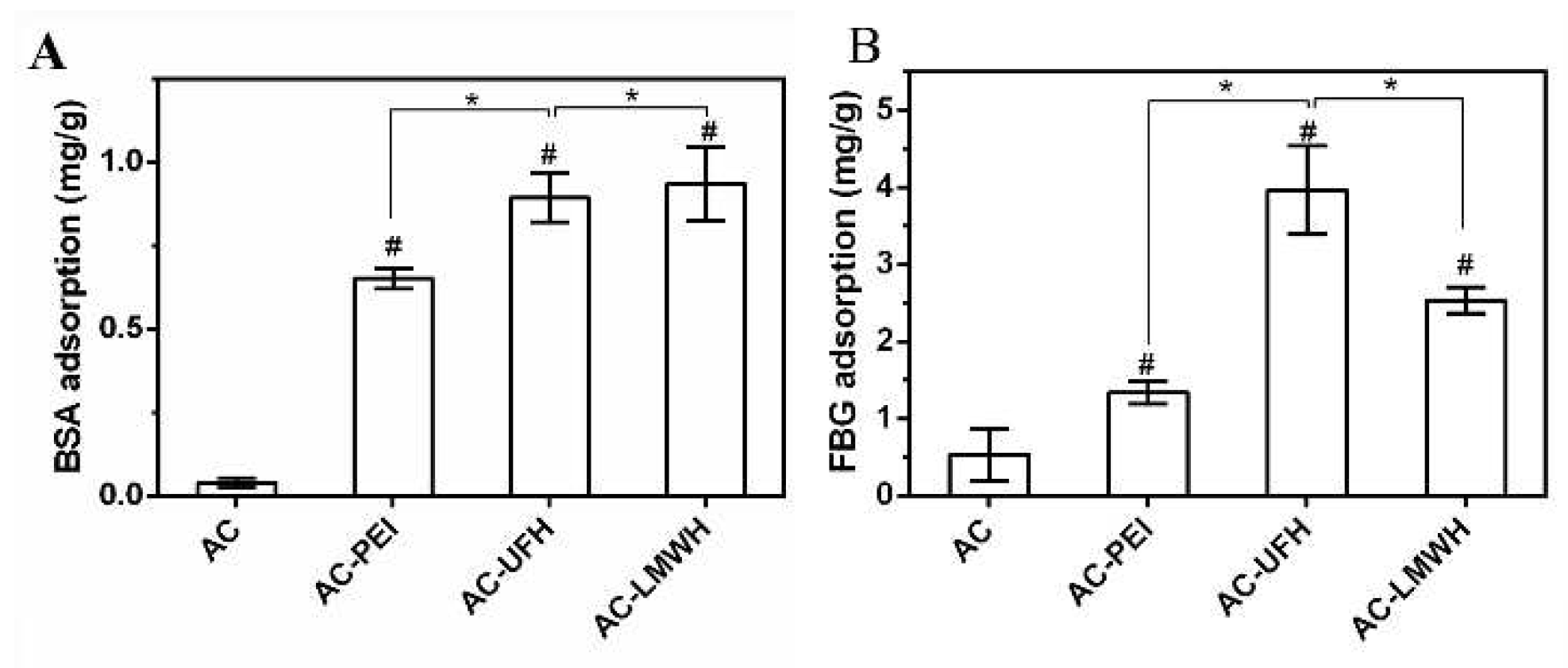

Protein adsorption is considered to be the first event that occurs when blood contacts the surface of material, and the adsorbed protein will mediate the subsequent biological reaction, including the occurrence of platelet adhesion and coagulation cascade reaction. So, it is necessary to investigate the protein adsorption for the evaluation of the blood compatibility of heparinized surface.

Figure 5 showed BSA and FBG adsorption of microspheres in normal saline. Compared with AC, the adsorption amount of modified microspheres on BSA and FBG was increased, which might be assigned to the surface charge and perturbation of molecular chains. It could be observed from

Figure 5A and B that the FBG adsorption amount of microspheres in same group was higher than that of BSA adsorption, implying that the surface of microspheres was more likely to cause FBG adsorption, and present the inertia to BSA. Interestingly, the BSA adsorption amount of AC-UFH and AC-LMWH had no obvious difference, but the FBG adsorption of AC-UFH was higher than that of AC-LMWH. It was reported that enoxaparin could improve the nature and structure of plasma fibrin clots and increase microvascular blood circulation by preventing microthrombosis.[

39]

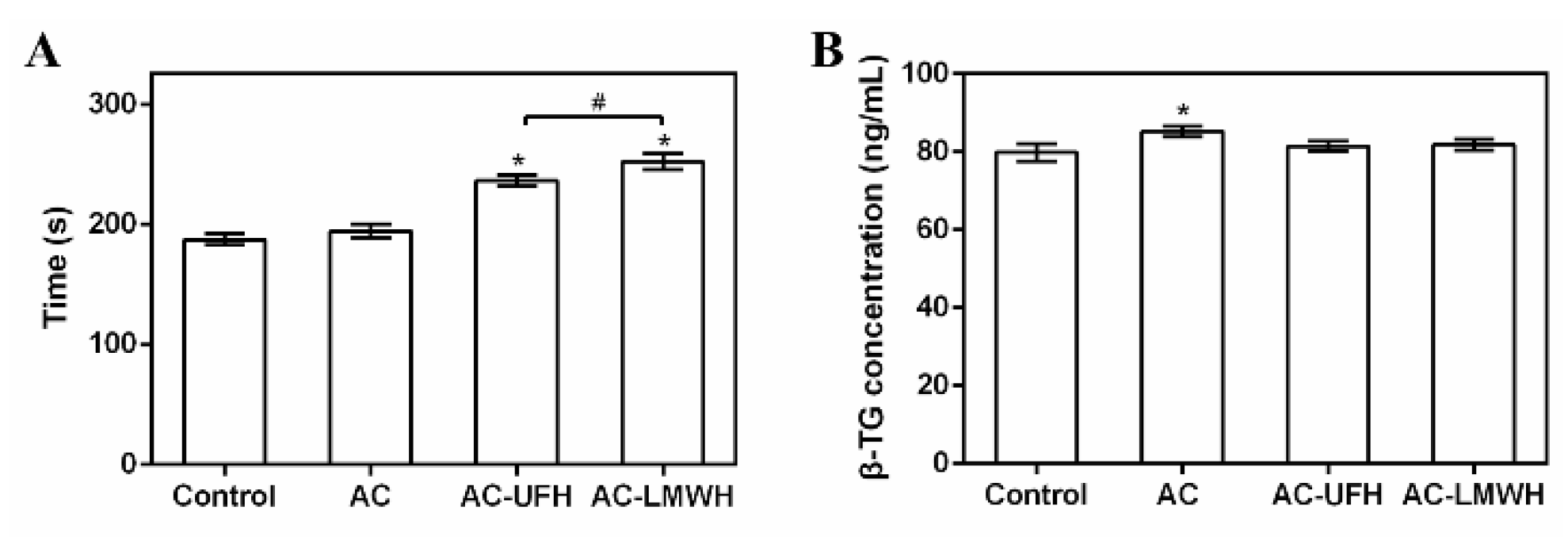

To evaluate the anticoagulation of AC-UFH and AC-LMWH, APTT was measured after PPP incubated with materials by activating the intrinsic blood coagulation cascade. It could be seen from

Figure 6A that APTT of AC was not changed obviously compared with control, showing no effect on blood coagulation. And APTT of AC-UFH and AC-LMWH was longer than that of AC, indicating that whether UFH or LMWH, it could improve the anticoagulation performance of materials when grafted. Although LMWH partially lost the ability to promote AT inactivation of thrombin (IIa) due to the lower molecular weight of heparin (enoxaparin), it still had the ability to inactivate Xa, which could result in the prolong of APTT. Furthermore, APTT of AC-LMWH was longer than that of AC-UFH, consistent with the literature [

40], which might be attributed to the grafting density of heparin on AC caused by steric hindrance.

When the medical device/material contacts with human blood, the increase of particulate matter in blood may be the inducement for the medical device/material to cause or promote bleeding or thrombosis.[

41] If the platelet granules were significantly higher than the control, it indicated that the medical device/material had the potential to activate platelets.[

42] β- thromboglobulin (β- TG) was one of platelet granules, and could represent the activation of platelets.

Figure 6B showed the concentration of β- TG after materials incubated with blood. It could be seen that the β- TG concentration of AC was higher than that of control, indicating that AC activated platelets. After grafted heparin, the β- TG concentration of AC-UFH and AC-LMWH had no significant difference with control, demonstrating that AC-UFH and AC-LMWH could reduce the activation level of platelets, and heparin modification could decrease the platelet activation of AC. Although there was no difference between AC-UFH and AC-LMWH, UFH and LMWH showed the ability of anti-platelet activation.

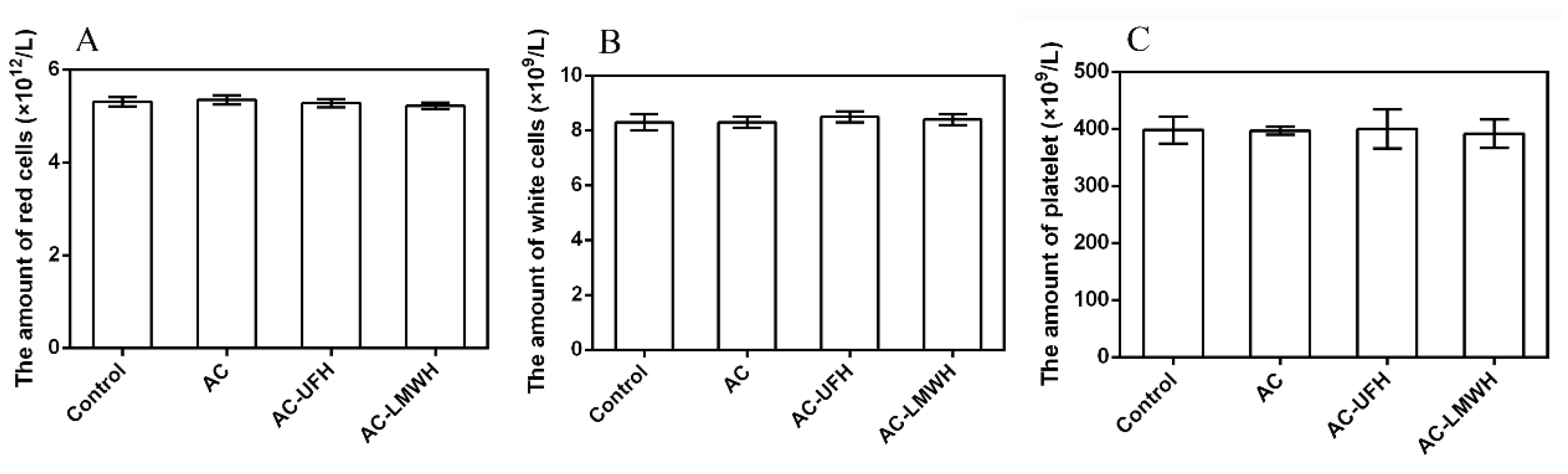

The loss of cell components in blood when AC perfused was a problem that could not be ignored. In addition to high adsorption capacity, the ideal adsorbents for hemoperfusion also needed to have adsorption specificity and good biocompatibility to achieve the effect of less non-specific adsorption of other blood components. In blood, blood cells account for about 45% of the blood volume, including red cells, white cells and platelets. The main function of red cells is to transport oxygen. White blood cells mainly play the role of immunity. When bacteria invade the human body, white cells can pass through the capillary wall, concentrate on the invasion site of the bacteria, surround the bacteria and swallow them. Platelets play an important role in hemostasis.

Figure 7 showed the amount of white cell, red cell and platelet of blood incubated with AC, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH. It could be seen that the amount of with cell, red cell and platelet of AC, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH had no significant difference from the control, indicating that AC, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH had no significant effect on blood cell composition. This was attributed to the microspore of AC preventing blood cells from entering and damaging.

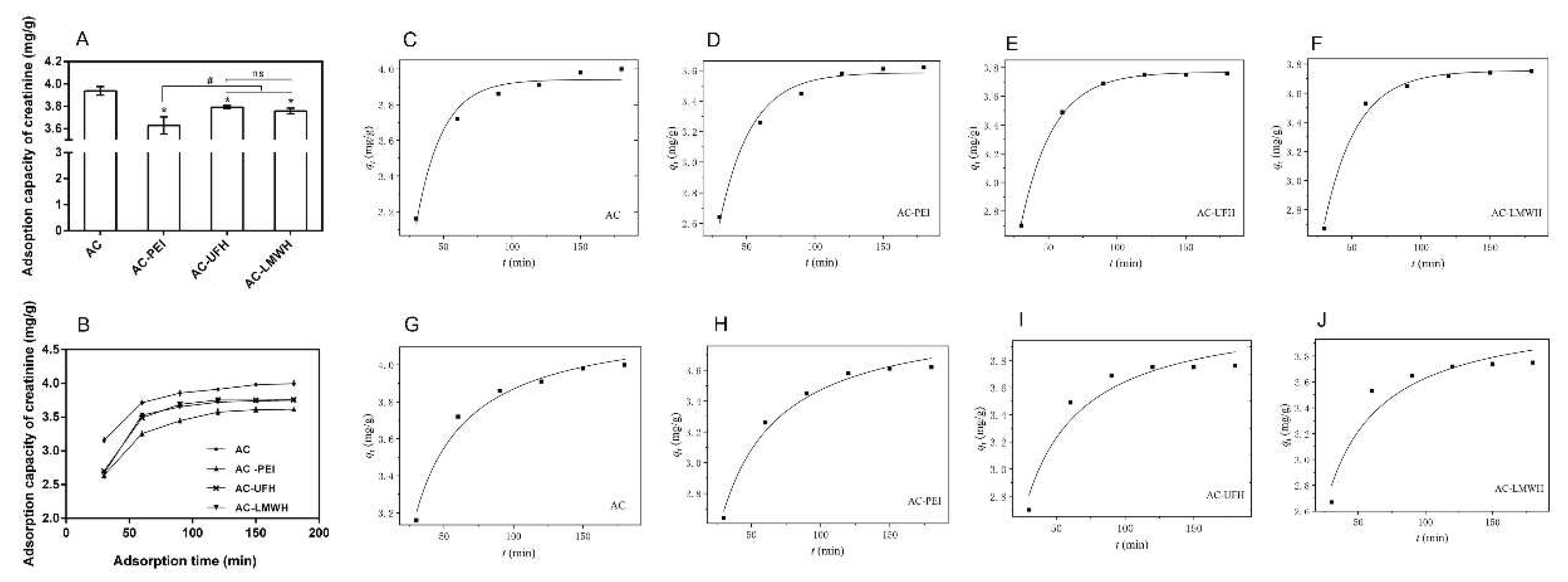

3.4. Adsorption of creatinine

As shown in

Figure 8A, the adsorption capacity of creatinine was decreased after the immobilization when compared with that of AC. When immobilized on AC, molecules would block the nano- and mesopores of AC, causing the reduction of specific surface area, which resulted in the decease of adsorption capacity. Then, the adsorption capacity of AC-UFH and AC-LMWH for creatinine was increased when compared with that of AC-PEI, which might be assigned to two reasons: one was the decline of BET surface, and the other was the positive charge of AC-PEI caused by rich amino. These results implied that the adsorption of creatinine could be affected by surface charges, and the heparin with negative functional groups would enhance the interaction with creatinine, which was consistence with previous report [

38]. For heparin with different molecular weights, it could be found that there was no significant difference between the adsorption capacity of AC-UFH and AC-LMWH.

Furthermore, the influence of adsorption time on adsorption of creatinine was investigated as shown in

Figure 8B. It could be seen that there was rapid adsorption for creatinine at initial 60 min and the equilibrium adsorption capacity of adsorbents could be reached within about 120 min. Besides, it was found from the adsorption curves that the adsorption rate of heparinized AC at initial 60 min was higher than that of AC and AC-PEI, which might be contributed to the functional groups of heparin.

Further, the adsorption kinetics of the adsorbent was nonlinearly fitted by pseudo-first-order kinetics model and pseudo-second-order kinetics model according to the data of

Figure 8B, as shown in

Figure 8(C-J). And

Table 5 presented the corresponding kinetic adsorption parameters calculated from the fitting equations. The kinetics adsorption of AC and AC-PEI was more in line with pseudo-second-order kinetics model (

>

), and the kinetics adsorption of AC-UFH and AC-LMWH was more in line with pseudo-first-order kinetics model (

<

), suggesting that the introduction of heparin resulted in more strong Van der Waals force between adsorbents and creatinine when compared with AC and AC-PEI. Although the k value of AC-UFH and AC-LMWH was lower than that of AC and AC-PEI, the

obtained by fitting was higher than that of AC-PEI, once again proving that the heparin immobilized on AC could enhance the adsorption capacity of creatinine through the intermolecular force.

3.5. Figures and Tables

Figure 1.

XPS spectra of AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH.

Figure 1.

XPS spectra of AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH.

Figure 2.

SEM images of surface and cross-section of AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH.

Figure 2.

SEM images of surface and cross-section of AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH.

Figure 3.

Texture curve of AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH with 10 scans per sample.

Figure 3.

Texture curve of AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH with 10 scans per sample.

Figure 4.

Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms (A) and pore size distribution curves (B) of AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH.

Figure 4.

Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms (A) and pore size distribution curves (B) of AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH.

Figure 5.

BSA (A) and FBG (B) adsorption capacity of absorbents. *p<0.05, #p<0.05 vs. AC.

Figure 5.

BSA (A) and FBG (B) adsorption capacity of absorbents. *p<0.05, #p<0.05 vs. AC.

Figure 6.

APTT (A) and (B) β- TG concentration of plasma incubated with absorbents, and control was untreated plasma. #p<0.05, *p<0.05 vs. control.

Figure 6.

APTT (A) and (B) β- TG concentration of plasma incubated with absorbents, and control was untreated plasma. #p<0.05, *p<0.05 vs. control.

Figure 7.

The amount of red cells (A), white cells (B) and platelet (C) of blood incubated with absorbents, and control was untreated blood.

Figure 7.

The amount of red cells (A), white cells (B) and platelet (C) of blood incubated with absorbents, and control was untreated blood.

Figure 8.

(A) Creatinine adsorption capacity of AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH (n=3), *p < 0.05 vs. AC, #p < 0.05. (B) Creatinine adsorption on AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH at different time. Fitting curve of pseudo-first-order kinetic model of AC (C), AC-PEI (D), AC-UFH (E), AC-LMWH (F). And fitting curve of pseudo-second-order kinetic model of AC (G), AC-PEI (H), AC-UFH (I), AC-LMWH (J).

Figure 8.

(A) Creatinine adsorption capacity of AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH (n=3), *p < 0.05 vs. AC, #p < 0.05. (B) Creatinine adsorption on AC, AC-PEI, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH at different time. Fitting curve of pseudo-first-order kinetic model of AC (C), AC-PEI (D), AC-UFH (E), AC-LMWH (F). And fitting curve of pseudo-second-order kinetic model of AC (G), AC-PEI (H), AC-UFH (I), AC-LMWH (J).

Table 1.

Chemical valence distribution and content proportion of C 1s.

Table 1.

Chemical valence distribution and content proportion of C 1s.

| Atom type |

Peak position/eV |

Formula |

Percentage (%) |

| C 1s |

284.84 |

C-C/C=C |

73.66 |

| 286.37 |

C-O |

6.65 |

| 287.14 |

C=O |

5.25 |

| 287.93 |

C-S/C=S |

3.09 |

| 289.05 |

-COOH |

7.65 |

| 290.95 |

CO32- (π-π*) |

3.70 |

| O 1s |

531.60 |

C-O |

41.58 |

| 532.50 |

-OH |

25.15 |

| 533.24 |

-COOH |

4.44 |

| 533.84 |

CH3-O-(S=O)-O-CH3

|

23.68 |

| 535.12 |

C=O |

3.70 |

| 536.70 |

H2O |

1.45 |

Table 2.

Chemical composition of microspheres calculated from XPS survey scans.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of microspheres calculated from XPS survey scans.

| Microsphere |

Element (Atom %) |

|

| C |

N |

O |

S |

| AC |

95.65 |

— |

4.07 |

0.29 |

| AC-PEI |

92.28 |

1.88 |

5.57 |

0.27 |

| AC-UFH |

89.86 |

1.46 |

8.32 |

0.36 |

| AC-LMWH |

92.31 |

1.35 |

5.99 |

0.35 |

Table 3.

Chemical composition of surface calculated by EDS point scanning.

Table 3.

Chemical composition of surface calculated by EDS point scanning.

| Microsphere |

Element (Atom %) |

|

| C |

O |

S |

| AC |

97.53±2.30 |

2.47±2.30 |

— |

| AC-UFH |

89.80±1.05 |

6.96±1.01* |

0.14±0.01* |

| AC-LMWH |

92.46±0.90 |

5.75±0.80* |

0.11±0.01* |

Table 4.

The fracture strength of materials by texture profile analysis.

Table 4.

The fracture strength of materials by texture profile analysis.

| Samples |

AC |

AC-PEI |

AC-UFH |

AC-LMWH |

| First peak force (N) |

25.28±2.95 |

22.56±1.71 |

23.70±5.81 |

28.68±3.21 |

Table 5.

Parameters for pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic model of adsorbents.

Table 5.

Parameters for pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic model of adsorbents.

| Sample |

Pseudo-first-order kinetic |

|

Pseudo-second-order kinetic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AC |

0.0528 |

0.9765 |

3.94 |

|

0.0239 |

0.9831 |

4.25 |

| AC-PEI |

0.0430 |

0.9850 |

3.59 |

|

0.0175 |

0.9854 |

3.97 |

| AC-UFH |

0.0423 |

0.9992 |

3.77 |

|

0.0164 |

0.9389 |

4.17 |

| AC-LMWH |

0.0424 |

0.9924 |

3.75 |

|

0.0165 |

0.9231 |

4.16 |

4. Conclusions

In summary, considering the different anticoagulant properties and flexibility of the macromolecular chain, UFH or LMWH was grafted on AC through the ligand of PEI by EDC/NHS coupling reaction to investigate the heparin with different molecular weights on anticoagulation and creatinine adsorption. After the modification, AC-UFH and AC-LMWH could maintain the original morphology and mechanical strength of AC, and the BET surface was found to be decreased due to the occupancy of heparin molecules. The anticoagulation of AC-UFH and AC-LMWH was found to be increased compared with AC, in which AC-LMWH had lower FBG adsorption and longer APTT. These results demonstrated that modification with LMWH could decreased the influence on FBG, which had great potential in anti-thrombosis. In future, heparin with different molecular weights could be selected for modification according to different anticoagulant properties required by materials, which could have more targeted effects. In addition, although the modification decreased the adsorption capacity of AC for creatinine, the introduction of heparin could enhance adsorption capacity compared with AC-PEI, which was contributed to the interaction between heparin chain and creatinine via Van der Waals force. And the heparin with different molecular weight had no effect on the adsorption of creatinine. Besides, the kinetic adsorption of adsorbents could reach equilibrium within 120 min. This research provided the theoretical basis for the widespread application of activated carbon in hemoperfusion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jincan Lei and Qi Dang; methodology, Jincan Lei, Haiyan Wang and Qi Dang; software, Jing Huang; validation, Xiang Wang; formal analysis, Haiiyan Wang; investigation, Jincan Lei, Haiyan Wang and Qi Dang; resources, Jingzhou Hou; data curation, Qi Dang and Kejing Fang; writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing, Qi Dang and Chungong Li; visualization, Xiang Wang; supervision, Xiang Wang and Shixian Zhao; project administration, Qi Dang; funding acquisition, Jincan Lei and Xiang Wang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number. 31271229 and 11572065), Project of Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Education Commission of China (grant number. KJQN201903312), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (grant number. cstc2021jcyj-bsh0268) and Scientific Research Foundation for High-level Talents of Chongqing City Management College (grant number. 2017kyqd01).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- T. G. Li, Y. Yan, N. N. Wang and M. Zhao, The American journal of emergency medicine, 2011, 29, 518–522.

- R. Bambauer, C. Bambauer, B. Lehmann, R. Latza and R. Schiel, TheScientificWorldJournal, 2012, 2012, 314283.

- P. H. Plotz, P. D. Berk, B. F. Scharschmidt, J. K. Gordon and J. Vergalla, The Journal of clinical investigation, 1974, 53, 778–785.

- R. Venkataraman, S. Subramanian and J. A. Kellum, Critical care, 2003, 7, 139–145.

- Y. Liu, X. Peng, Z. Hu, M. Yu, J. Fu and Y. Huang, Materials science & engineering. C, Materials for biological applications, 2021, 121, 111879.

- Z. Li, X. Yan, K. Wu, Y. Jiao, C. Zhou and J. Yang, ACS applied bio materials, 2021, 4, 4896–4906.

- Y. Yang, S. Yin, C. He, X. Wu, J. Yin, J. Zhang, L. Ma, W. Zhao, C. Cheng and C. Zhao, Journal of materials chemistry. B, 2020, 8, 1960–1970.

- W. Dou, J. Wang, Z. Yao, W. Xiao, M. Huang and L. Zhang, Materials Advances, 2022, 3, 918–930.

- H. Yatzidis, Nephron, 1964, 1, 310–312.

- J. Barnes, L. D. Cowgill and J. Diaz Auñon, Advances in Small Animal Care, 2021, 2, 131–142.

- T. M. Chang, Kidney international. Supplement, 1975, 387-392.

- T. M. Chang, Journal of bioengineering, 1976, 1, 25–32.

- T. M. Chang, Science, 1964, 146, 524–525.

- C. A. Howell, S. R. Sandeman, Y. Zheng, S. V. Mikhalovsky, V. G. Nikolaev, L. A. Sakhno and E. A. Snezhkova, Carbon, 2016, 97, 134–146.

- N. Cai, Q. Li, J. Zhang, T. Xu, W. Zhao, J. Yang and L. Zhang, Journal of colloid and interface science, 2017, 503, 168–177.

- X. Deng, T. Wang, F. Zhao, L. Li and C. Zhao, Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2007, 103, 1085–1092.

- A. Rodriguez-Fernandez, M. Sanchez-Dominguez, I. Torrado-Espanol, B. Noguerado-Mellado and P. Rojas-Perez-Ezquerra, Journal of investigational allergology & clinical immunology, 2019, 29, 132–134. [Google Scholar]

- N. Banik, S. B. Yang, T. B. Kang, J. H. Lim and J. Park, International journal of molecular sciences, 2021, 22.

- R. G. Ingle and A. S. Agarwal, Carbohydrate polymers, 2014, 106, 148–153.

- K. M. Brinkhous, H. P. Smith, Jr., E. D. Warner and W. H. Seegers, Science, 1939, 90, 539.

- U. Lindahl, G. Backstrom, M. Hook, L. Thunberg, L. A. Fransson and A. Linker, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1979, 76, 3198–3202.

- G. M. Oosta, W. T. Gardner, D. L. Beeler and R. D. Rosenberg, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1981, 78, 829–833.

- L. Thunberg, U. Lindahl, A. Tengblad, T. C. Laurent and C. M. Jackson, The Biochemical journal, 1979, 181, 241–243.

- P. A. Howard, Journal of infusion nursing : the official publication of the Infusion Nurses Society, 2003, 26, 304–310.

- B. H. Chong and F. Ismail, European journal of haematology, 1989, 43, 245–251.

- J. K. Burgess and B. H. Chong, European journal of haematology, 1997, 58, 279–285.

- D. A. Garcia, T. P. Baglin, J. I. Weitz and M. M. Samama, Chest, 2012, 141, e24S–e43S.

- R. Biran and D. Pond, Advanced drug delivery reviews, 2017, 112, 12–23.

- T. Taniguchi, K.-H. Kyung and S. Shiratori, RSC Advances, 2015, 5, 107488–107496.

- Q. Dang, C. G. Li, X. X. Jin, Y. J. Zhao and X. Wang, Carbohydrate polymers, 2019, 205, 89–97.

- N. Jacob Kaleekkal, Journal of Membrane Science, 2021, 623, 119068.

- C. G. Li, Q. Yang, D. Chen, H. Zhu, J. Chen, R. Liu, Q. Dang and X. Wang, RSC Adv, 2022, 12, 34837–34849.

- H. Wei, L. Han, J. Ren and L. Jia, ACS applied materials & interfaces, 2013, 5, 12571–12578.

- L. Shan, Y. Sun, F. Shan, L. Li and Z. P. Xu, Journal of materials chemistry. B, 2020, 8, 878–894.

- M. Zhang, C. H. H. Chan, J. P. Pauls, C. Semenzin, C. Ainola, H. Peng, C. Fu, A. K. Whittaker, S. Heinsar and J. F. Fraser, Journal of materials chemistry. B, 2022, 10, 4974–4983.

- L. Wang, F. Fang, Y. Liu, J. Li and X. Huang, Applied Surface Science, 2016, 385, 308–317.

- Z. Chao, J. Li, W. Jiang, C. Zhang, J. Ji, X. Hua, L. Xu, L. Han and L. Jia, Materials Chemistry Frontiers, 2021, 5, 7617–7627.

- N. Jacob Kaleekkal, Journal of Membrane Science, 2021, 623.

- M. Zabczyk, J. M. Zabczyk, J. Natorska, K. P. Malinowski and A. Undas, Vascular pharmacology, 2020, 133-134, 106783.

- M. K. Meher and K. M. Poluri, Carbohydrate polymers, 2022, 291, 119546.

- K. Egan, J. P. van Geffen, H. Ma, B. Kevane, A. Lennon, S. Allen, E. Neary, M. Parsons, P. Maguire, K. Wynne, O. K. R, J. W. M. Heemskerk and F. N. Ainle, Thrombosis research, 2017, 154, 7–15.

- K. Gerling, L. M. Herrmann, C. Salewski, M. Wolf, P. Mullerbader, D. Siegel-Axel, H. P. Wendel, C. Schlensak, M. Avci-Adali and S. Stoppelkamp, Biomolecules, 2021, 11.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).