1. Introduction

Sepsis is characterized by an imbalance in the immune response triggered by bacterial, viral, or fungal infections in the host, leading to life-threatening multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) [

1]. Sepsis is a prevalent and severe complication among critically ill patients, marked by high incidence and mortality rates, and imposes a substantial economic burden on healthcare systems globally. Recent epidemiological data from mainland China indicate that the incidence of sepsis is approximately 20.6%, with a 90-day mortality rate of 35.5% and a median medical expenditure reaching up to 50,000 RMB [

2]. Current therapeutic approaches for sepsis primarily encompass anti-infective measures, fluid resuscitation, administration of vasopressors, and organ support therapies. However, traditional treatment modalities fail to effectively modulate the immune dysfunction observed in septic patients, thereby not significantly reducing sepsis-related mortality [

3]. Therefore, it is of great significance to search for new therapeutic targets for immunoregulatory therapy in sepsis patients and to explore more effective therapeutic regimens.

“Cytokine storm" is a key factor in the occurrence of sepsis-induced MODS, linked to an excessive inflammatory response involving white blood cells, endothelial cells, cytokines, and the coagulation system [

4]. Pathogen- and damage-associated molecular patterns activate immune cells, leading to the release of inflammatory cytokines like interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and IL-8. This damages endothelial cells and activates the coagulation system, causing a cytokine storm that results in disseminated intravascular coagulation, microcirculation dysfunction, and MODS [

5,

6]. Wiersinga et al. found that injecting live bacteria or their cell wall components in live animals triggers a strong inflammatory response, while removing these cytokines can prevent MODS and death [

7]. Therefore, alleviating the cytokine storm by regulating immune response may be a key target for treating sepsis.

Endotoxins, lipopolysaccharides from Gram-negative bacteria, are released upon cell death and recognized by receptors like Toll-like receptor 4, activating signaling pathways [

8]. On the one hand, these endotoxins induce a marked increase in inflammatory mediators, including IL-6, IL-8, and endothelial cell adhesion molecules such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and E-selectin protein, through the mitogen activated protein kinase and NF-κB pathways. On the other hand, endotoxins contribute to endothelial dysfunction through the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase/reactive oxygen species/endothelial nitric oxide synthase pathway [

9].

In recent years, circulating histones have been identified as a novel class of damage-associated molecular patterns. Our previous research demonstrated that circulating histones can mediate excessive inflammatory responses and contribute to organ dysfunction in patients with sepsis [

10]. Histones have a molecular weight ranging from approximately 11 to 21 kDa and possess a primary structure abundant in basic amino acids, such as arginine and lysine, which confer a positive charge in bodily fluids [

11]. Under normal physiological conditions, histones are primarily involved in chromatin assembly and the regulation of gene transcription. During sepsis, however, inflammatory mediators activate innate immune cells, including neutrophils, macrophages, and monocytes, resulting in a reduced adhesion capacity of histones to immune cells. This reduction leads to the detachment of histones from the cell surface and the formation of circulating histones [

12]. Studies have indicated that the concentration of circulating histones in septic patients is significantly elevated compared to healthy individuals (63.5 μg/mL versus 1.5 μg/mL) and is positively correlated with both disease severity and mortality [

13]. Our study also revealed that circulating histones can activate immune cells, initiate a "cytokine storm," and subsequently trigger the activation of the coagulation system and damage to endothelial cells, ultimately resulting in MODS. Various anionic drugs, including heparin, recombinant protein C, and sialic acid, can mitigate the cytotoxic effects of histones by binding to the positively charged histones, thereby inhibiting tissue neutrophil infiltration and inflammatory exudation induced by histones, and alleviating organ damage in sepsis [

14]. To date, an increasing number of studies have begun to identify circulating histones as critical immune regulatory factors in the cytokine storm associated with sepsis [

15,

16,

17].

Chitosan is a naturally occurring polysaccharide derived from the deacetylation of chitin, characterized by its high storage capacity and excellent biocompatibility [

18]. The molecular structure of chitosan is rich in amino groups, which becomes protonated and facilitate the adsorption of endotoxins through electrostatic interactions [

19]. In our previous work, we developed self-anticoagulant heparin-grafted chitosan/cellulose composite (CSCEHEP) microspheres for simultaneous adsorption of endotoxin and circulating histones. Our findings demonstrated that the obtained CSCEHEP microspheres significantly prolonged plasma coagulation time while maintaining excellent hemocompatibility, owing to the heparin coating. In vitro, CSCEHEP microspheres exhibited considerable adsorption capacities of 251.0 EU/g for endotoxin, with an adsorption clearance ratio of 81.8%, and 288.6 μg/g for histones, with an adsorption clearance ratio of 62.8%. Additionally, CSCEHEP microspheres effectively adsorbed histones in whole blood and counteracted histone-induced endothelial and kidney epithelial cytotoxicity, erythrocyte fragility, and thrombocytopenia [

20]. In this context, the present study seeks to examine the effectiveness of heparin-free hemoperfusion utilizing CSCEHEP microspheres in an LPS-induced septic rabbit model. This investigation focuses on assessing the adsorption efficiency of endotoxins and histones, as well as evaluating the immunoregulatory properties of the CSCEHEP microspheres.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Chitosan (CS, viscosity: 100–200 mPa.s, deacetylation degree ≥ 95%) powder, α-Cellulose (CE, 90 μm, AR), heparin sodium salt (185 USP units/mg), urea (AR), lithium hydroxide (LiOH, AR), potassium hydroxide (KOH, ACS), and toluidine bule (AR) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co. Ltd. 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC, 98%) was purchased from McLean Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. LPS from Escherichia coli 055:B5, rabbit IL-6 ELISA Kit, rabbit TNF-α ELISA Kit were purchased from Biyotime Biotechnology Co. Ltd. Rabbit histone H3 ELISA reagent and rabbit LPS ELISA reagent were purchased from Shanghai Renjie Biotechnology Co. Ltd. New Zealand white rabbit purchased from the animal experiment center of Jiujiang University Affiliated Hospital. Measurements of serum bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, urea nitrogen and creatinine were conducted at the Animal Experiment Center of Jiujiang University Affiliated Hospital.

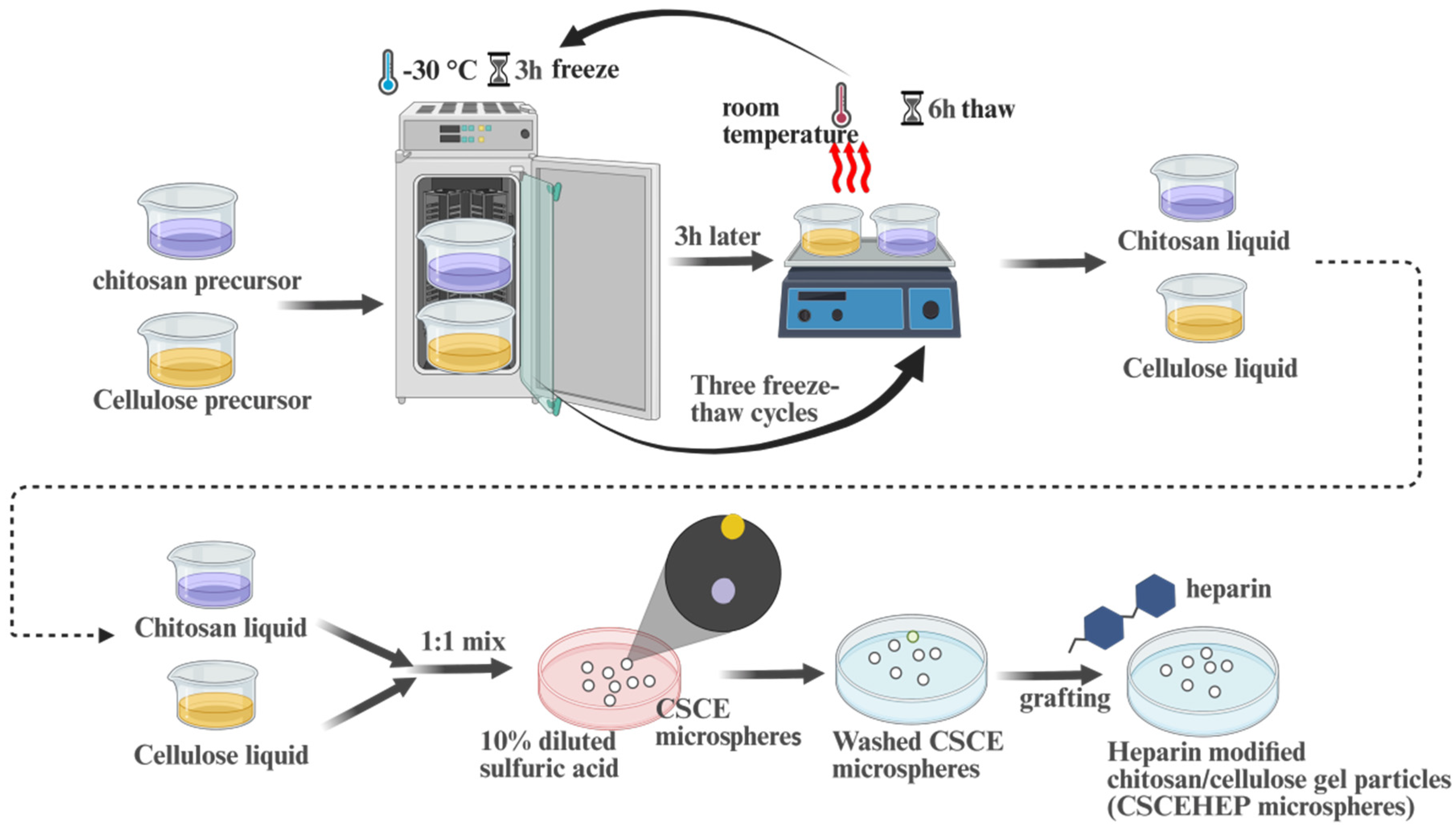

2.2. Preparation of CSCE and CSCEHEP Microspheres

According to our previous work [

20], the preparation process of CSCE and CSCEHEP microspheres can be found in

Figure 1. First, CS and CE solution (dissolved in 4 wt.% alkaline-urea system) were frozen at -30℃ for 4 h, and completely thawed at room temperature. The CS and CE solutions were then mixed in a 1: 1 mass ratio and stirred vigorously after three freeze-thaw cycles. Then, CSCE microspheres were obtained by dropping the mixed CE/CS solution uniformly into a 10 wt.% diluted sulfuric acid solution using a syringe needle (28G). CSCE microspheres were repeatedly cleaned with DI water and stored in DI water. Afterwards, a carbodiimide coupling method was used to prepare CSCEHEP microspheres. In detail, a certain quality heparin sodium salt, CSCE and EDC were reacted in 100mL of 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid buffer solution (0.1M) at room temperature for 24 hours. The CSCEHEP microspheres were washed with DI water and then stored in PBS.

2.3. Efficacy of Extracorporeal Hemoperfusion with CSCEHEP in a Septic Rabbit Model

The experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiujiang First People's Hospital (JJSDYRMYY-YXLL-2023-129). Healthy New Zealand white rabbits (~2.5 kg) were allowed seven days for acclimation, with free access to water and food. We divided healthy New Zealand rabbits into four groups, including a healthy control group, a LPS group, a CSCE group, and a CSCEHEP group, with each group comprising four rabbits. The healthy control group did not undergo any surgical operation, only anesthesia treatment. In the LPS group, Escherichia coli LPS was intravenously injected into the ear vein at a dosage of 500 μg·kg-1. After 12 hours of LPS injection, the rabbits showed symptoms such as fever, lethargy, and poor appetite, confirming the successful establishment of a septic rabbit model. Before the start of hemoperfusion, anesthesia was induced in the rabbits through an intravenous injection of 3% pentobarbital sodium at a dosage of 1 mL·kg⁻¹. Subsequently, the right femoral artery and vein were isolated and secured individually using indwelling needles (24G) to facilitate connection to a custom-made CSCE or CSCEHEP hemoperfusion column. Twelve hours following LPS administration, septic rabbits underwent extracorporeal hemoperfusion utilizing CSCE or CSCEHEP microspheres at a flow rate of 5 mL/min for a duration of 2 hours, without the incorporation of heparin in the blood circuits. Venous blood samples were collected for the analysis of LPS, histones, inflammatory cytokines, and additional parameters. After 2 hours of hemoperfusion, the blood in the column was returned to the rabbit's body using physiological saline and the surgical incision was carefully sutured. The thrombus and total protein adsorption on the column were studied and histopathological injury of the liver and kidneys was assessed within 24 hours after extracorporeal hemoperfusion.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

In this study, either one-way ANOVA or t-test were employed to compare the differences in measured outcomes among different groups. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 software.

3. Results

3.1. Self-Anticoagulation Property of the Home-Made CSCEHEP Hemoperfusion Column

To better meet the needs of hemoperfusion, we redesigned the adsorbents used in hemoperfusion devices by utilizing CSCE or CSCEHEP microspheres as the substrate. We filled a sterile chromatography column measuring 10 mm×10 mm with 20 mg of sterilized CSCE or CSCEHEP microspheres, occupying 95% of the column's space, and primed it with physiological saline to remove air. Additionally, the CSCE and CSCEHEP hemoperfusion column was pre-circulated with physiological saline containing 25% sodium heparin for 30 minutes. Following the intravenous injection of LPS in rabbits for 12 hours, a specially designed device with a column (7.5 mL) packed with CSCE or CSCEHEP microspheres was used for extracorporeal hemoperfusion from the femoral artery to the vein at a blood flow rate of 5 mL·min

–1 (

Figure 2a). Meanwhile, sham-hemoperfusion was carried out using a column filled with glass beads as the LPS group. As depicted in

Figure 2b, the CSCE column turned to dark red following the 2 hours hemoperfusion (original color: white), indicating significant coagulation and thrombogenesis within the CSCE hemoperfusion column. In contrast, the CSCEHEP microspheres column displayed a very light red color, nearly retaining its original white color, with no evident contamination or clotting observed after the 2 hours hemoperfusion. These findings demonstrate that CSCEHEP microspheres possess excellent self-anticoagulation properties in vivo, attributed to the heparin coating. In addition to visual observation, we also detected a total protein adsorption capacity of 42.01 ± 4.68 μg·mg

−1 on the CSCE column, exceeding 8.48-fold of the CSCEHEP column (4.95 ± 1.00 μg·mg

−1) (

Figure 2c).

3.2. Effect of Hemoperfusion with CSCEHEP Microspheres on Blood Cells

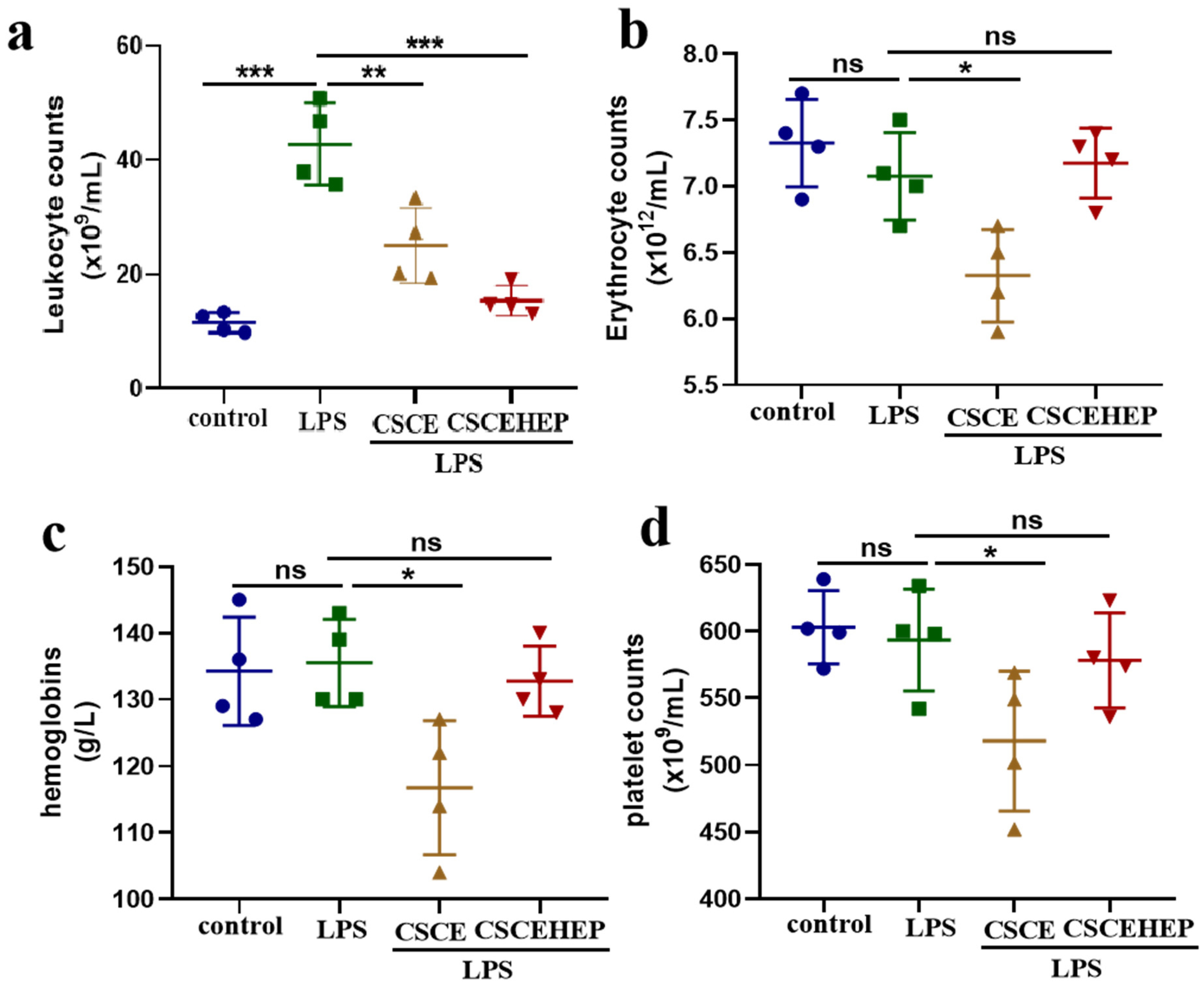

As shown in

Figure 3a, compared to the control group, all sepsis rabbits suffered from severe inflammatory reaction after the LPS injection and the number of leukocyte counts increased remarkably by nearly 73% (P-values < 0.001). The leukocyte counts of CSCEHEP group significantly reduced compared to LPS group (P-values < 0.001), which revealed CSCEHEP microspheres eliminated the LPS-induced inflammatory reaction during the hemoperfusion session.

Figure 3b-c demonstrates that the erythrocyte counts in the CSCE group showed a significant decrease compared with the LPS group due to local thrombus formation (P-values = 0.03). However, there was no significant difference in erythrocyte counts and hemoglobin levels between the CSCEHEP group and the LPS group (P-values = 0.97, P-values = 0.96), indicating that the heparin layer on CSCEHEP exerts sufficient anticoagulant effect to avoid local thrombus formation. As for the platelet counts,

Figure 3d shows that the CSCE group exhibited a significant decrease in platelet counts compared with the LPS group (P-values = 0.43), which was also due to the platelet consumption caused by column thrombosis, while the CSCEHEP group showed no significant change in platelet counts (P-values = 0.95).

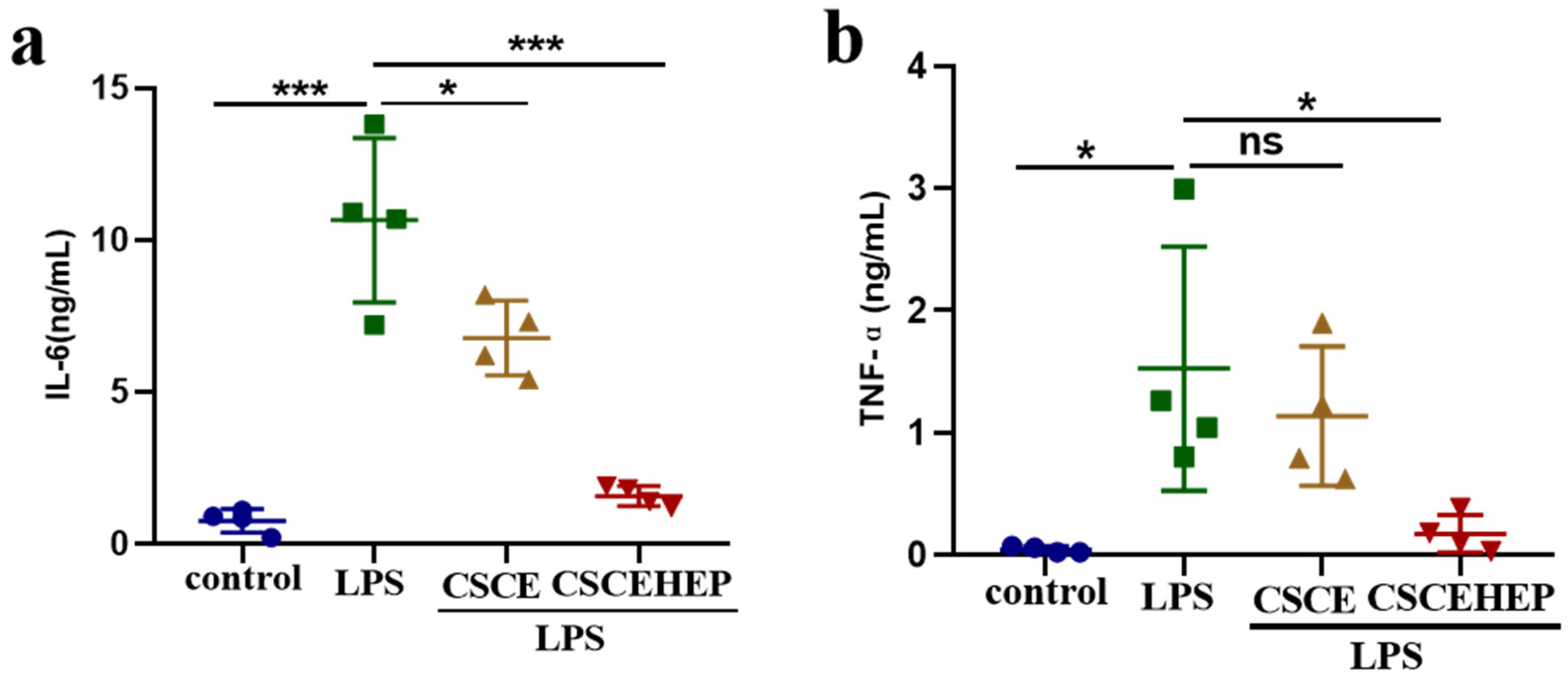

3.3. Effect of Hemoperfusion with CSCEHEP Microspheres on Inflammatory Responses

Next, the immunoregulatory property of CSCEHEP microspheres in the septic rabbit model was studied, and we chose IL-6 and TNF-α as indicators of the inflammatory response. As shown in

Figure4 a-b, compared with the control group, the concentrations of IL-6 and TNF-α in septic rabbits significantly increased after intravenous injection of LPS for 2 hours. Compared to LPS group, the IL-6 concentration in both the CSCE (P-values = 0.02) and CSCEHEP group was significantly reduced (P-values < 0.001). Compared with the LPS group, however, the CSCE group showed no significant decrease in TNF-α concentration (P-values = 0.78), while the CSCEHEP group showed a significant decrease (P-values = 0.03). The findings suggest that CSCE microspheres exhibit a measurable capacity to inhibit the anti-inflammatory response induced by LPS. However, CSCEHEP microspheres demonstrate a superior anti-inflammatory effect, mainly attributed to the potent anti-inflammatory properties of heparin.

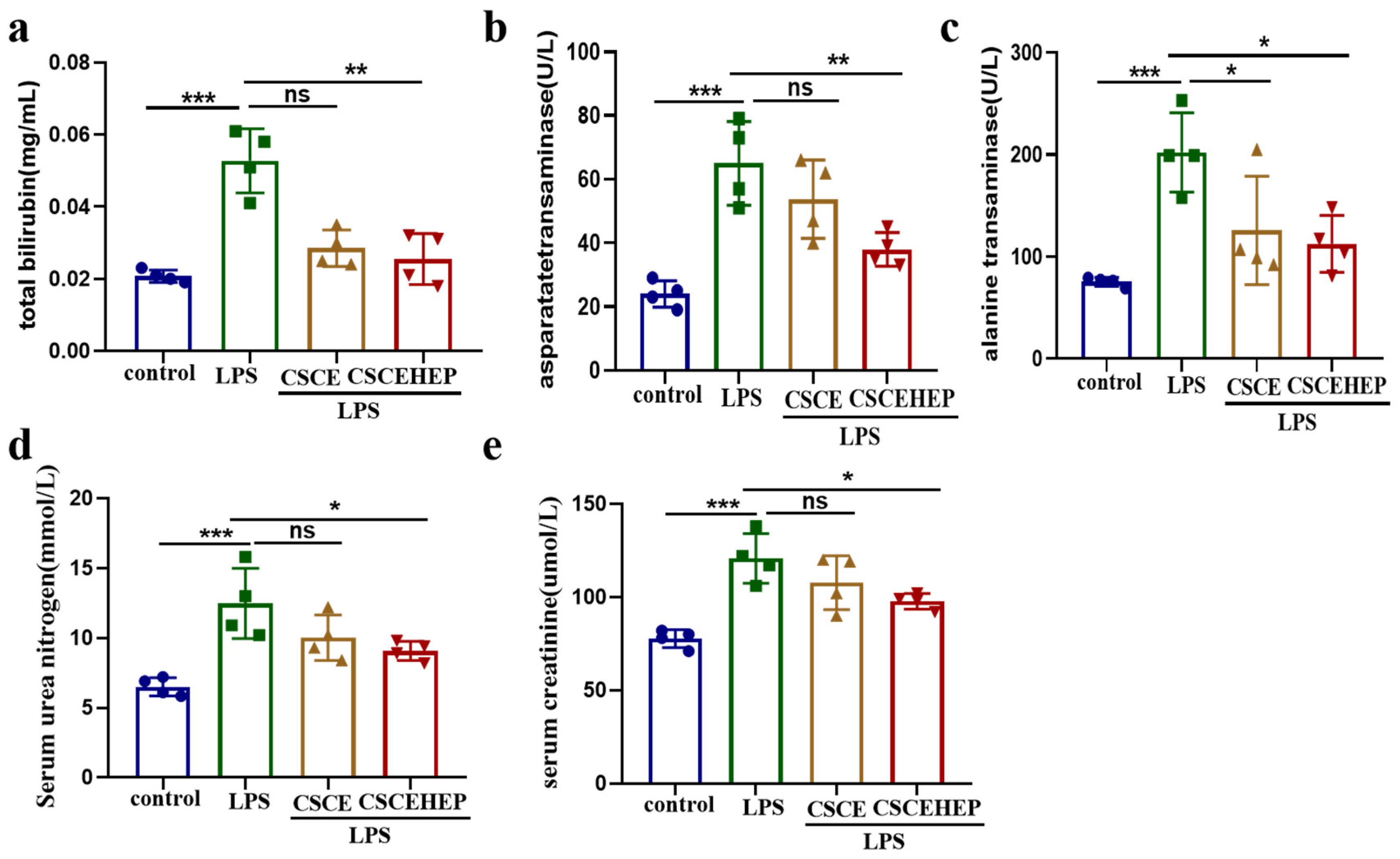

3.4. Effect of Hemoperfusion with CSCEHEP Microspheres on Liver Function and Renal Function

We use serum total bilirubin, aspartate transaminase, and alanine transaminase activities to reflect the dynamic changes of liver function injury in sepsis rabbit. Serum urea nitrogen and creatinine are used to evaluate changes in renal injury. In the LPS-treated group, the total bilirubin, the aspartate transaminase as well as alanine transaminase level exhibited a statistically significant increase compared to the control group (all P-values < 0.001). Compared to the LPS group, the CSCEHEP group exhibit a notable decrease in the aforementioned indicators (all P-values < 0.05) (

Figure 5a-c). As illustrated in

Figure 5d-e, the serum urea nitrogen and creatinine level in the LPS group showed significantly increased compared to control group (all P-values < 0.001). Both the serum urea nitrogen and creatinine level in CSCEHEP group showed a significant decrease compared to LPS group (all P-values = 0.04), whereas the CSCE group did not show a significant reduction (P-values = 0.18, P-values = 0.33).

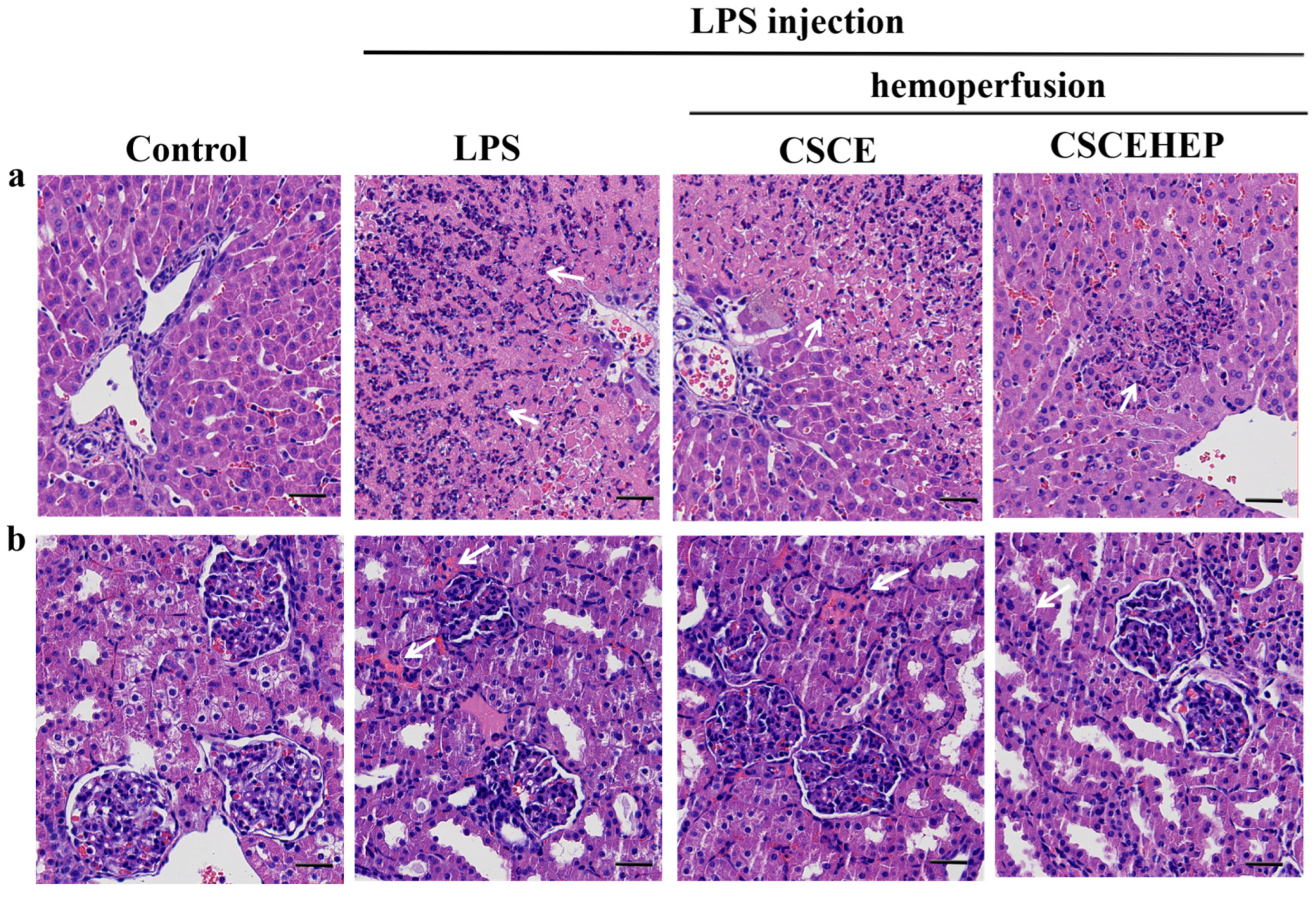

3.5. Effect of Hemoperfusion with CSCEHEP Microspheres on Pathological Damage of Liver and Kidney

We further evaluated the influence of hemoperfusion with CSCEHEP microspheres on the pathological damage of liver and kidney in septic rabbits. Upon challenge with LPS, the liver and kidney tissues of rabbits exhibit rapid and severe inflammatory reactions compared to the control group. In contrast, timely hemoperfusion treatment with CSCEHEP microspheres significantly reduces the infiltration of inflammatory cells in liver tissue (as indicated by the white arrow) (

Figure 6a). Additionally, in comparison to the control group, the LPS group demonstrates pronounced inflammatory cell infiltration in kidney tissue. Hemoperfusion with CSCEHEP microspheres markedly diminishes inflammation in renal tissue compared to the LPS group (as indicated by the white arrow) (

Figure 6b).

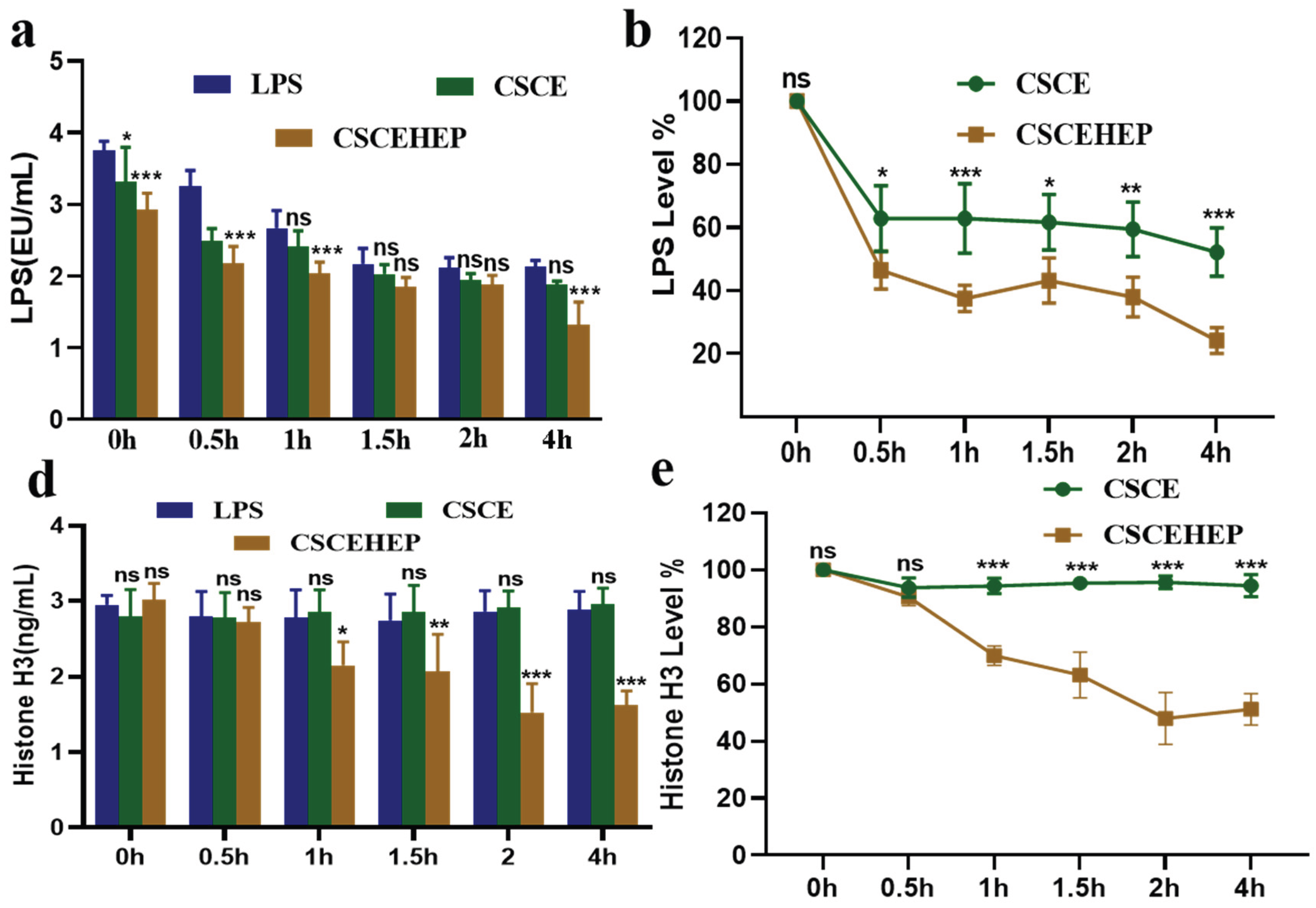

3.6. Effect of Hemoperfusion with CSCEHEP Microspheres on Serum Levels of LPS and Histone H3

As shown in

Figure 7a-b, the peripheral blood LPS level in the LPS group reached at a relatively high level of 3.75 EU·mL

–1. By contrast, in the hemoperfusion group using CSCEHEP microspheres for a duration of 2 hours, a progressive decline in the LPS level from 3.75 ± 0.13 EU·mL

–1 to 1.31±0.32 EU·mL

–1 (P-values < 0.05), more than 70 % of the LPS in blood could be removed by the 7.5mL column (~3.0 g CSCEHEP microspheres). Although CSCE microspheres also exhibit LPS scavenging ability to some extent, the adsorption behavior is more based on non-specific protein adsorption rather than LPS clearance. We can see from

Figure 7c-d that the peripheral blood histone H3 level in the LPS group reached at a relatively high level of 2.95 ± 0.12 ng·mL

–1. After 2 hours hemoperfusion, serum histone H3 levels did not differ significantly between CSCE group and LPS group (P-values = 0.96). However, we can see histone H3 levels extremely decrease to 1.53 ± 0.38 ng·mL

–1 in CSCEHEP group compared to LPS group (P-values < 0.01), nearly 50% of the histone H3 level in blood could be removed.

4. Discussion

The key inflammatory mediators, such as endotoxins and circulating histones, are pivotal in the onset and progression of the "cytokine storm" associated with sepsis. Addressing the issue of immune imbalance in sepsis is critically important for effective treatment; however, this aspect is frequently neglected in clinical settings. With advancements in blood purification technologies, hemoperfusion adsorbents are increasingly employed to eliminate abnormal cytokines, endotoxins, and other inflammatory mediators from the bloodstream of sepsis patients. Despite this, there is a notable lack of hemoperfusion devices specifically designed to remove circulating histones. Currently, the most commonly utilized hemoperfusion adsorbents in clinical practice include polymyxin B (PMX) blood adsorption columns and the oXiris® membrane. These adsorbents have been shown to decrease endotoxin levels in the blood of sepsis patients to varying extents; however, their impact on improving patient survival rates remains inconclusive. According to Dellinger et al., PMX does not significantly reduce the 28-day mortality rate in sepsis patients with an endotoxin activity assay (EAA) greater than 0.6 [

21], and only when the endotoxin load is low (EAA 0.6-0.9) can PMX reduce the short-term mortality rate of patients [

22]. The oXiris membrane material is an AN69ST membrane modified with polyethyleneimine cationic polymer, which has triple functions of endotoxin adsorption, cytokine clearance, and kidney replacement [

23]. Small sample queue studies have shown that the oXiris membrane can significantly reduce SOFA scores and improve hemodynamics of septic patients [

24]. A retrospective study found that the oXiris membrane could reduce SOFA scores faster, but its long-term survival benefit in septic patients is still unknow [

25]. In addition, the median filter life of oXiris membrane is lower (13 hours vs 16 hours), and it is more prone to hemofilter coagulation [

26], associated with high dependence on heparin or citrate anticoagulation. In conclusion, current hemoperfusion adsorbents encounter several clinical challenges, including limited adsorption efficiency, a significant dependence on heparin or citrate anticoagulation, a narrow range of adsorption targets, and suboptimal blood compatibility. The advancement of domestically produced, high-efficiency endotoxin adsorbents that enhance adsorption capacity while simultaneously addressing the clearance of diverse pathogenic factors—such as inflammatory mediators, pathogenic bacteria, and histones—and incorporating self-anticoagulant properties, is of paramount importance. Such developments hold the potential to significantly reduce the mortality rate among sepsis patients.

Our previous study indicated that CSCEHEP microspheres demonstrated excellent hemocompatibility and self-anticoagulant properties, showing no significant activation of complement, contact or kinin systems, nor causing marked hemolysis, cytopenia or platelet activation [

20]. Featuring a loosely porous internal structure with high specific surface area, CSCEHEP microspheres adsorbed 81.8% endotoxin in PBS with an adsorption capacity of 251.0 EU/g. The histone adsorption capacity of CSCEHEP microspheres was 288.6 μg/g in PBS, with a histone clearance ratio of 62.8%. Furthermore, CSCEHEP microspheres effectively adsorbed histones in whole blood and counteracted histone-induced cytotoxicity, erythrocyte osmotic fragility and thrombocytopenia[

20]. These results indicate that the heparin layer on CSCE microspheres can still exhibit self-anticoagulant properties, maintain smooth local blood flow in the extracorporeal pipeline during hemoperfusion, and prevent the risk of bleeding caused by traditional systemic heparinization. This greatly avoids the bleeding risk of systemic anticoagulation in critically ill diseases such as sepsis treated with blood adsorption therapy [

27]. To further validate the self-anticoagulation properties of CSCEHEP microspheres, as well as their clearance and adsorption efficiency in immune regulation within animal models, we developed a blood hemoperfusion device specifically for sepsis rabbit models. Subsequently, we assessed the safety and efficacy of CSCEHEP microspheres in the treatment of sepsis.

In this study, we employed CSCEHEP microspheres for 2 hours hemoperfusion treatment in septic rabbits, notably achieving the procedure without the use of heparin. we found that CSCEHEP microspheres could reduce the increase of leukocyte counts induced by LPS in septic rabbits, indicating that they can exert anti-inflammatory effects through certain mechanisms. Further investigation revealed that CSCEHEP could reduce IL-6 and TNF-α levels in an LPS-induced sepsis rabbit model, confirming that the CSCEHEP microspheres can stabilize anti-inflammatory effects, which might be attributed to the anti-inflammatory effect of chitosan and heparin components in the CSCEHEP microspheres. Chitosan has been confirmed by multiple studies to have significant anti-inflammatory effects, which involve regulating immune responses, inhibiting the release of pro-inflammatory factors, and promoting tissue repair [

28,

29]. Heparin is not only a classic anticoagulant, but has also been shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects through mechanisms such as inhibiting the release of inflammatory mediators, regulating immune cell function, protecting endothelial cells, and clearing free radicals [

30,

31,

32]. Sepsis can rapidly cause tissue damage to multiple organs, leading to liver failure and kidney failure [

33]. The CSCEHEP microspheres also showed a significant decrease in both liver function and renal function, and facts observed that CSCEHEP microspheres can improve the infiltration of inflammatory cells in the liver and renal tissue of septic rabbits.

Endotoxins are one of the core targets in the pathophysiological mechanism of sepsis, especially in sepsis associated with gram-negative bacterial infections. Recent studies have shown that extracellular histones are another novel potential mediator of sepsis induced death [

34,

35]. Histones are the most abundant proteins in the nucleus, consisting of adaptor histone H1 and core histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 [

36]. In animal models of sepsis, histones are released into interstitial spaces where they induce local inflammatory cell aggregation, endothelial damage, and organ dysfunction[

37,

38]. Research has shown that the level of circulating histone H3 is closely associated with coagulation disorder[

39]. It follows that evaluating histone H3 levels is not only important for identifying the severity of sepsis, but also for developing histone-targeted therapy strategies. Our study demonstrated a significant elevation in the concentrations of LPS and histone H3 in septic rabbits. With the extension of hemoperfusion duration, the efficacy of CSCEHEP microspheres hemoperfusion in clearing LPS and histone H3 progressively enhanced. After a 2 hours period of hemoperfusion, the CSCEHEP microspheres hemoperfusion successfully removed over 70% of LPS and approximately 50% of histone H3 from the bloodstream of septic rabbits. Simultaneously, no notable protein contamination or coagulation was detected on the CSCEHEP column during 2 hours hemoperfusion conducted in the absence of heparin

5. Limitations of the Study

This study is subject to several limitations. Firstly, the research focused exclusively on various indicators of sepsis in rabbits subjected to a 2 hours blood perfusion, without extending the observation to track these indicators and the survival prognosis of the sepsis-affected rabbits at 12 hours and 24 hours. Secondly, the specificity of peripheral blood histone H3 concentration as a marker for sepsis requires further investigation, as elevated levels of circulating histone H3 are also observed in non-infectious conditions such as trauma and pancreatitis. Thirdly, this study did not include an assessment of other histone family members, such as histone H4. Previous research indicates that histone H4 is also a potent activator of platelets and endothelial cells, and a combined analysis of histone H4 and H3 levels could enhance our understanding of sepsis pathogenesis.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, the CSCEHEP microspheres we have developed exhibit effective self-anticoagulation properties and can achieve 2 hours heparin free hemoperfusion therapy in septic rabbits. This advancement addresses the challenges of coagulation dysfunction and elevated bleeding risk in patients with sepsis or those who are critically ill. CSCEHEP microspheres have been shown to effectively mitigate the systemic inflammatory response in septic rabbits. This is evidenced by a significant reduction in serum leukocyte count, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) levels. Additionally, there is marked improvement in liver and kidney function, accompanied by a substantial decrease in tissue inflammatory cell infiltration. These findings suggest that CSCEHEP microspheres may alleviate the systemic manifestations of sepsis and prevent organ failure resulting from dysregulated inflammatory responses. Furthermore, CSCEHEP microspheres demonstrated the capability to adsorb 70% of LPS and effectively removed approximately 50% of histone H3 in septic rabbits, achieving dual-targeted adsorption of LPS and histone from the pathogenic source of sepsis. Therefore, CSCEHEP microspheres are promising hemoperfusion adsorbents with simultaneous endotoxin and histone adsorption for future extracorporeal hemoadsorption in sepsis patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.J. Y.L. and H.X.; methodology, L.J. F.W. Y.L. Y.S. Y.L. and H.X.; software, Y.S.; validation, Y.L. and H.X.; formal analysis, L.J. and Y.L.; investigation, L.J.; resources, L.J.; data curation, L.J. Y.L. and H.X; writing—original draft preparation, L.J.; writing—review and editing, Y.L. and H.X.; visualization, F.W.; supervision, Y.L. and H.X.; project administration, L.J. Y.L. and H.X.; funding acquisition, L.J. Y.L. and H.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially sponsored by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82300848), General Project of Jiang-xi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No.20232BAB206031) and Key Research and Development Program of Jiujiang City-Agriculture and Social Development (S2024ZDYFN0048).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Jiujiang First People's Hospital (JJSDYRMYY-YXLL-2023-129).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge that the use of BioRender.com for creating the pro-cess diagram of microspheres preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, Seymour CW, Liu VX, Deutschman CS, et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). Jama. 2016 2016 Feb 23;315(8):775-87. [CrossRef]

- Xie J, Wang H, Kang Y, Zhou L, Liu Z, Qin B, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in chinese icus: a national cross-sectional survey. Crit Care Med. 2020 2020 Mar;48(3):e209-18. [CrossRef]

- Song C, Xu J, Gao C, Zhang W, Fang X, Shang Y. Nanomaterials targeting macrophages in sepsis: a promising approach for sepsis management. Front Immunol. 2022 2022/1/1;13:1026173. [CrossRef]

- Iba T, Levi M, Levy JH. Intracellular communication and immunothrombosis in sepsis. J Thromb Haemost. 2022 2022 Nov;20(11):2475-84. [CrossRef]

- Moriyama K, Nishida O. Targeting cytokines, pathogen-associated molecular patterns, and damage-associated molecular patterns in sepsis via blood purification. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 2021 Aug 18;22(16). [CrossRef]

- Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2013 2013 Aug 29;369(9):840-51. [CrossRef]

- Wiersinga WJ, Leopold SJ, Cranendonk DR, van der Poll T. Host innate immune responses to sepsis. Virulence. 2014 2014 Jan 1;5(1):36-44. [CrossRef]

- Thon P, Rump K, Knorr A, Dyck B, Ziehe D, Unterberg M, et al. The distinctive activation of toll-like receptor 4 in human samples with sepsis. Cells. 2022 2022 Sep 27;11(19). [CrossRef]

- Grylls A, Seidler K, Neil J. Link between microbiota and hypertension: focus on lps/tlr4 pathway in endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation, and therapeutic implication of probiotics. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021 2021 May;137:111334. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wan D, Luo X, Song T, Wang Y, Yu Q, et al. Circulating histones in sepsis: potential outcome predictors and therapeutic targets. Front Immunol. 2021 2021/1/1;12:650184. [CrossRef]

- Singh RK, Paik J, Gunjan A. Generation and management of excess histones during the cell cycle. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2009 2009 Jan 1;14(8):3145-58. [CrossRef]

- Yang T, Li Y, Su B. Understanding the multiple roles of extracellular histones in mediating en-dothelial dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022 2022 Oct;33(10):1951-52. [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama Y, Ito T, Yasuda T, Furubeppu H, Kamikokuryo C, Yamada S, et al. Circulating histone h3 levels in septic patients are associated with coagulopathy, multiple organ failure, and death: a single-center observational study. Thromb J. 2019 2019/1/1;17:1. [CrossRef]

- Jiang L, Li Y, Du H, Qin Z, Su B. Effect of anticoagulant administration on the mortality of hospitalized patients with covid-19: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 2021/1/1;8:698935. [CrossRef]

- Ligi D, Lo Sasso B, Della Franca C, Giglio RV, Agnello L, Ciaccio M, et al. Monocyte distribution width alterations and cytokine storm are modulated by circulating histones. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2023 2023 Jul 26;61(8):1525-35. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X, Jin J, Lv T, Song Y. A narrative review: the role of nets in acute respiratory distress syn-drome/acute lung injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 2024 Jan 25;25(3). [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Li X. The role of histones and heparin in sepsis: a review. J Intensive Care Med. 2022 2022 Mar;37(3):319-26. [CrossRef]

- Lv S, Zhang S, Zuo J, Liang S, Yang J, Wang J, et al. Progress in preparation and properties of chitosan-based hydrogels. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023 2023 Jul 1;242(Pt 2):124915. [CrossRef]

- Reay SL, Jackson EL, Salthouse D, Ferreira AM, Hilkens CMU, Novakovic K. Effective endotoxin removal from chitosan that preserves chemical structure and improves compatibility with immune cells. Polymers (Basel). 2023 2023 Mar 23;15(7). [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y, Chen Y, Song T, Jiang L, He Y, Li Y, et al. Simultaneous removal of endotoxin and circulating histones by heparin-grafted chitosan-cellulose composite microspheres for multi-targeted extracorporeal hemoadsorption in septic blood. Biomacromolecules. 2025, Accepted. [CrossRef]

- Dellinger RP, Bagshaw SM, Antonelli M, Foster DM, Klein DJ, Marshall JC, et al. Effect of targeted polymyxin b hemoperfusion on 28-day mortality in patients with septic shock and elevated endotoxin level: the euphrates randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2018 2018 Oct 9;320(14):1455-63. [CrossRef]

- Klein DJ, Foster D, Walker PM, Bagshaw SM, Mekonnen H, Antonelli M. Polymyxin b hemoperfusion in endotoxemic septic shock patients without extreme endotoxemia: a post hoc analysis of the euphrates trial. Intensive Care Med. 2018 2018 Dec;44(12):2205-12. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Sun P, Chang K, Yang M, Deng N, Chen S, et al. Effect of continuous renal replacement therapy with the oxiris hemofilter on critically ill patients: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2022 2022 Nov 13;11(22). [CrossRef]

- Zang S, Chen Q, Zhang Y, Xu L, Chen J. Comparison of the clinical effectiveness of an69-oxiris versus an69-st filter in septic patients: a single-centre study. Blood Purif. 2022 2022/1/1;51(7):617-29. [CrossRef]

- Guan M, Wang H, Tang X, Zhao Y, Wang F, Zhang L, et al. Continuous renal replacement therapy with adsorbing filter oxiris in acute kidney injury with septic shock: a retrospective observational study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 2022/1/1;9:789623. [CrossRef]

- Wong ET, Ong V, Remani D, Wong W, Haroon S, Lau T, et al. Filter life and safety of hepa-rin-grafted membrane for continuous renal replacement therapy - a randomized controlled trial. Semin Dial. 2021 2021 Jul;34(4):300-08. [CrossRef]

- Scully M, Levi M. How we manage haemostasis during sepsis. Br J Haematol. 2019 2019 Apr;185(2):209-18. [CrossRef]

- Reay SL, Marina Ferreira A, Hilkens CMU, Novakovic K. The paradoxical immunomodulatory effects of chitosan in biomedicine. Polymers (Basel). 2024 2024 Dec 25;17(1). [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Chang L, Xiong Y, Peng Q. Chitosan-based hydrogels as antibacteri-al/antioxidant/anti-inflammation multifunctional dressings for chronic wound healing. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024 2024 Dec;13(30):e2401490. [CrossRef]

- Cassinelli G, Naggi A. Old and new applications of non-anticoagulant heparin. Int J Cardiol. 2016 2016 Jun;212 Suppl 1:S14-21. [CrossRef]

- Wat JM, Audette MC, Kingdom JC. Molecular actions of heparin and their implications in pre-venting pre-eclampsia. J Thromb Haemost. 2018 2018 Jun 7. [CrossRef]

- Simard JM, Schreibman D, Aldrich EF, Stallmeyer B, Le B, James RF, et al. Unfractionated heparin: multitargeted therapy for delayed neurological deficits induced by subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2010 2010 Dec;13(3):439-49. [CrossRef]

- Lelubre C, Vincent J. Mechanisms and treatment of organ failure in sepsis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018 2018 Jul;14(7):417-27. [CrossRef]

- Patel BV, Lee TML, O'Dea K. Clustering circulating histones in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023 2023 Jul 15;208(2):125-27. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Zhang X, Pelayo R, Monestier M, Ammollo CT, Semeraro F, et al. Extracellular histones are major mediators of death in sepsis. Nat Med. 2009 2009 Nov;15(11):1318-21. [CrossRef]

- Talbert PB, Henikoff S. Histone variants at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2021 2021 Mar 26;134(6). [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Wang Y, Qu M, Li W, Wu D, Cata JP, et al. Neutrophil, neutrophil extracellular traps and endothelial cell dysfunction in sepsis. Clin Transl Med. 2023 2023 Jan;13(1):e1170. [CrossRef]

- Denning N, Aziz M, Gurien SD, Wang P. Damps and nets in sepsis. Front Immunol. 2019 2019/1/1;10:2536. [CrossRef]

- Ligi D, Giglio RV, Henry BM, Lippi G, Ciaccio M, Plebani M, et al. What is the impact of circulating histones in covid-19: a systematic review. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2022 2022 Sep 27;60(10):1506-17. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).