1. Introduction

Acetaminophen (APAP), also known as paracetamol or N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)acetamide, is a widely used over-the-counter and prescription non-steroidal analgesic and antipyretic. Its primary pharmacological action involves the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis through cyclooxygenase (COX-1 and COX-2) pathways, thereby alleviating pain and reducing fever. Global consumption of APAP is substantial, estimated at nearly 1.5 tons annually [

1,

2,

3]. China and India currently lead global production, accounting for over 70% of the total supply [

4,

5].

Despite its therapeutic benefits, APAP has been increasingly recognized as a persistent and ubiquitous contaminant in aquatic environments, posing a pressing environmental and health concern. Its widespread usage, combined with incomplete removal in conventional wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), contributes to its frequent detection in wastewater effluents, surface waters, groundwater, and even seawater. Reported concentrations range from nanograms to milligrams per liter. [

1,

6,

7]. With a solubility of 305 mg/L at 25 °C and a Log Kow of 0.46, APAP is relatively hydrophilic and poorly adsorbed onto organic matter, contributing to its mobility in aquatic systems. Following administration, approximately 90% of APAP is excreted via urine in both unchanged and conjugated forms [

8]. Additional pathways of environmental contamination include discharge from pharmaceutical manufacturing and improper disposal of expired or unused medications [

1]. The direct release of untreated or partially treated wastewater, a significant source of APAP, can have severe ecotoxic effects on aquatic species and carcinogenic and mutagenic effects on humans [

9].

The environmental occurrence of APAP has consequences. It has been documented in surface water, groundwater, and drinking water sources across 29 countries, with reported concentrations averaging 0.161 μg/L and reaching a maximum of up to 230 μg/L. These concentrations, even at the lower end of the range, are significant and indicate the widespread presence of APAP in our water sources, posing potential risks to both the environment and human health [

10].

Human health risks associated with APAP include severe hepatotoxicity, oxidative stress, DNA damage, and liver failure in overdose scenarios. Environmentally, it is classified as a high-risk pollutant, particularly to aquatic organisms [

11,

12,

13]. Aquatic invertebrates such as Daphnia magna, as well as fish species like

Danio rerio and trout, exhibit sensitivity to APAP even at trace levels, manifesting in oxidative stress, enzyme inhibition, and developmental impairments [

14,

15]. Notably, paracetamol was identified as the NSAID (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) that disrupted the most significant number of oxidative stress biomarkers, underscoring its ecotoxicological relevance [

16]. Plants also experience phytotoxic effects, including reduced concentrations of photosynthetic pigments and inhibited root growth [

13].

While the challenges are significant, the potential of advanced treatment solutions beyond conventional methods is promising. A recent survey of 20 WWTPs in China revealed APAP in 19 of the samples, with concentrations ranging from 0.06 to 29.2 nM. However, despite high removal rates reported for APAP during secondary treatment [

3,

17,

18], more toxic metabolites such as

p-aminophenol have been detected post-treatment at elevated concentrations (23.93–108.68 nM), indicating the existence of metabolic bottlenecks in existing treatment processes [

19]. This highlights the need for advanced treatment solutions beyond conventional methods, along with continuous monitoring strategies to mitigate potential environmental and health risks [

8,

20,

21].

Several advanced remediation technologies have been explored for the removal of APAP. Among these, Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) have garnered considerable interest due to their ability to generate highly reactive radicals, particularly hydroxyl (•OH), capable of mineralizing organic pollutants into benign by-products [

3,

22]. In AOPs, hydroxyl radicals play a key role in breaking down organic pollutants, including APAP, into simpler, less harmful compounds, thereby reducing their environmental impact. However, AOPs face limitations, including incomplete mineralization and the formation of toxic intermediates—especially during photocatalytic oxidation. Additionally, UV-based systems are energy-intensive, and their efficiency can be diminished by background organic matter or radical-scavenging ions present in complex water matrices. Membrane technologies, including microfiltration, ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, and reverse osmosis, provide an advanced treatment pathway. While these systems offer high separation efficiencies, they are often hindered by membrane fouling, increased energy consumption, and high operational costs, particularly in pressure-driven applications such as reverse osmosis [

23,

24]. Additionally, high energy consumption is a notable drawback, particularly in pressure-driven systems, such as reverse osmosis, which require substantial energy inputs to maintain optimal performance.

Electrochemical methods, particularly Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes (EAOPs), provide a flexible alternative for degrading pharmaceutical pollutants through redox reactions [

25]. Recent innovations in nanostructured electrodes and catalytic coatings have significantly improved performance [

26]. Integration with biological and membrane-based technologies has also demonstrated synergistic potential in complex treatment scenarios.

Biological remediation approaches, including phytoremediation and microbial biodegradation, have shown promise due to their sustainability and cost-effectiveness. Phytoremediation relies on specific plant species—often hardy or invasive—to absorb and transform pharmaceuticals through enzymatic pathways [

27,

28]. Similarly, microbial biodegradation utilizes bacteria, fungi, and microalgae capable of enzymatically degrading APAP via pathways involving amidases, oxygenases, and deaminases [

13]. The low operational cost and environmental compatibility of biological methods make them an attractive option for sustainable water treatment. However, these methods are sensitive to environmental factors such as temperature, pH, and the presence of co-contaminants, which can impair microbial activity and overall efficiency.

Among the various remediation technologies, adsorption has emerged as one of the most promising strategies for removing emerging contaminants, including pharmaceutical contaminants from water systems [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Adsorbents, such as activated carbon and biochar, capitalize on their high surface area, porosity, and tunable surface chemistries to effectively capture organic contaminants [

34]. Activated carbon, available in both granular (GAC) and powdered (PAC) forms, is particularly valued for its cost-effectiveness, chemical stability, and high adsorption capacity. Surface modifications, including oxidation and amination, further enhance its performance by introducing reactive functional groups that improve affinity toward ionizable or polar compounds such as APAP [

20,

35,

36,

37]. Advanced materials such as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and graphene derivatives exhibit even higher adsorption capacities. However, their high production costs and limited scalability remain significant barriers to widespread application [

38,

39]. In contrast, activated carbon offers a practical and scalable solution, especially for large-scale water treatment applications. Despite its advantages, adsorption-based remediation is not without challenges. Regeneration of spent adsorbents via thermal or chemical means is often energy-intensive and can degrade material integrity over time [

40]. Moreover, safe disposal or recycling of exhausted adsorbents is critical to prevent secondary contamination. Nonetheless, continued advancements in adsorbent materials and system design underscore the viability of adsorption, particularly using activated carbon, as a cornerstone strategy for APAP remediation.

Enhancing the yield and performance of activated carbons can be effectively achieved through modifications to their surface chemistry and porous structure. In this context, we have explored hydrothermal modification as a viable strategy to improve the physicochemical properties of activated carbon. This approach has yielded promising results in previous studies, where the modified materials demonstrated high adsorption capacities for contaminants such as thorium [

41], uranium [

42], and acetamiprid [

43]. Additionally, these materials have shown catalytic activity in reactions relevant to the synthesis of fine chemicals [

44], further highlighting their versatility and potential for multifunctional applications.

In this context, the present study explores the use of activated carbon for the adsorption and removal of acetaminophen from contaminated water. Particular emphasis is placed on elucidating the adsorption mechanisms, evaluating key performance parameters, and assessing the practical feasibility of applying this approach in real-world water treatment systems.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of Carbonaceous Materials

The proximate analysis (heating program detailed in the Supplementary Material) yielded comparable results for both materials, with a slight reduction in fixed carbon content and a corresponding increase in volatile matter in the hydrothermally treated sample (MH), as shown in

Table 1. Both samples exhibit high fixed carbon content, indicative of a significant degree of carbonization, characteristic of activated carbons.

The elemental composition of the organic phase (excluding ash content) is summarized in

Table 2. Hydrothermal treatment results in an increase in carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur content, and a reduction in hydrogen and oxygen. The former three elements are typically embedded within the graphene basal plane and thus exhibit lower reactivity. Conversely, hydrogen and oxygen, commonly located at the edges or defects of the carbon matrix, are more susceptible to removal under hydrothermal conditions.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) further confirms these trends. Atomic and mass-based compositions are reported in

Table 3 and

Table 4, respectively. Both samples display surfaces enriched in carbon, with MH showing a more uniform composition and detectable nitrogen content, not detected in M.

Deconvolution of the C 1s peak (

Figure 1,

Table 5) reveals that hydrothermal treatment significantly reduces the proportion of moderately oxidized carbon species (285.7 to 286.5 eV) and strongly oxidized carbon species (288.6 to 289.6 eV), associated with hydroxyl/ether/carbonyl and carboxylic/ester groups, respectively. In contrast, the signal at 284.8 eV, corresponding to sp² carbon or C–H/C–C bonding, increases in MH.

The deconvolution of the O 1s peak, while limited due to overlap and complexity of functional groups, reveals the emergence of a secondary component at 536.8 eV in MH in addition to the only one showed by M (533 eV), suggesting structural rearrangements during treatment (

Figure S4). Other elemental peaks did not present sufficient resolution for further analysis.

The point of zero charge (PZC) increased from 7.51 (M) to 8.06 (MH), indicating a reduction in surface acidity. This is consistent with the XPS results showing a decrease in oxygenated groups following hydrothermal treatment.

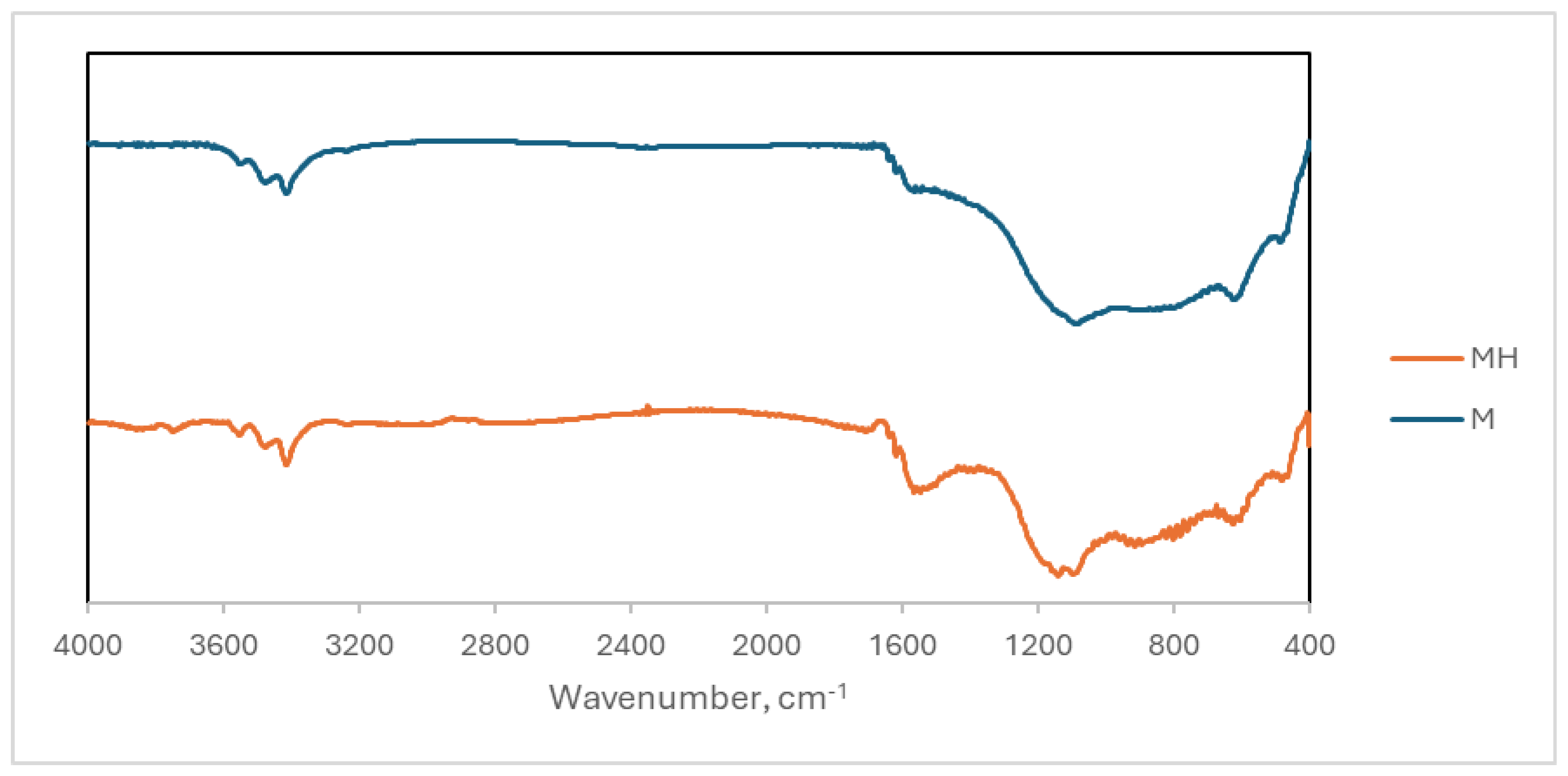

The FTIR spectra of both samples is shown in

Figure 2. There are some small differences between them.

Some of the main bands observed are: 3450 cm-1 (O-H), 1700 cm-1 (C=O), 1550 cm-1 (C=C), 1140 cm-1 (C-O). It is observed that the 1700 cm-1 band only appears (weakly) in the MH sample. The band near 1140 cm-1 has a maximum in M and a double peak in MH. This indicates that changes have occurred in the functional groups possessing C-O single bonds as discussed in the XPS analysis. In addition, in the region between 1500 and 1300 cm-1 carbon backbone of these materials there is a decrease in the intensity at MH while the relative intensity of the 1550 cm-1 band increases. This implies that there are also changes in this part of the structure.

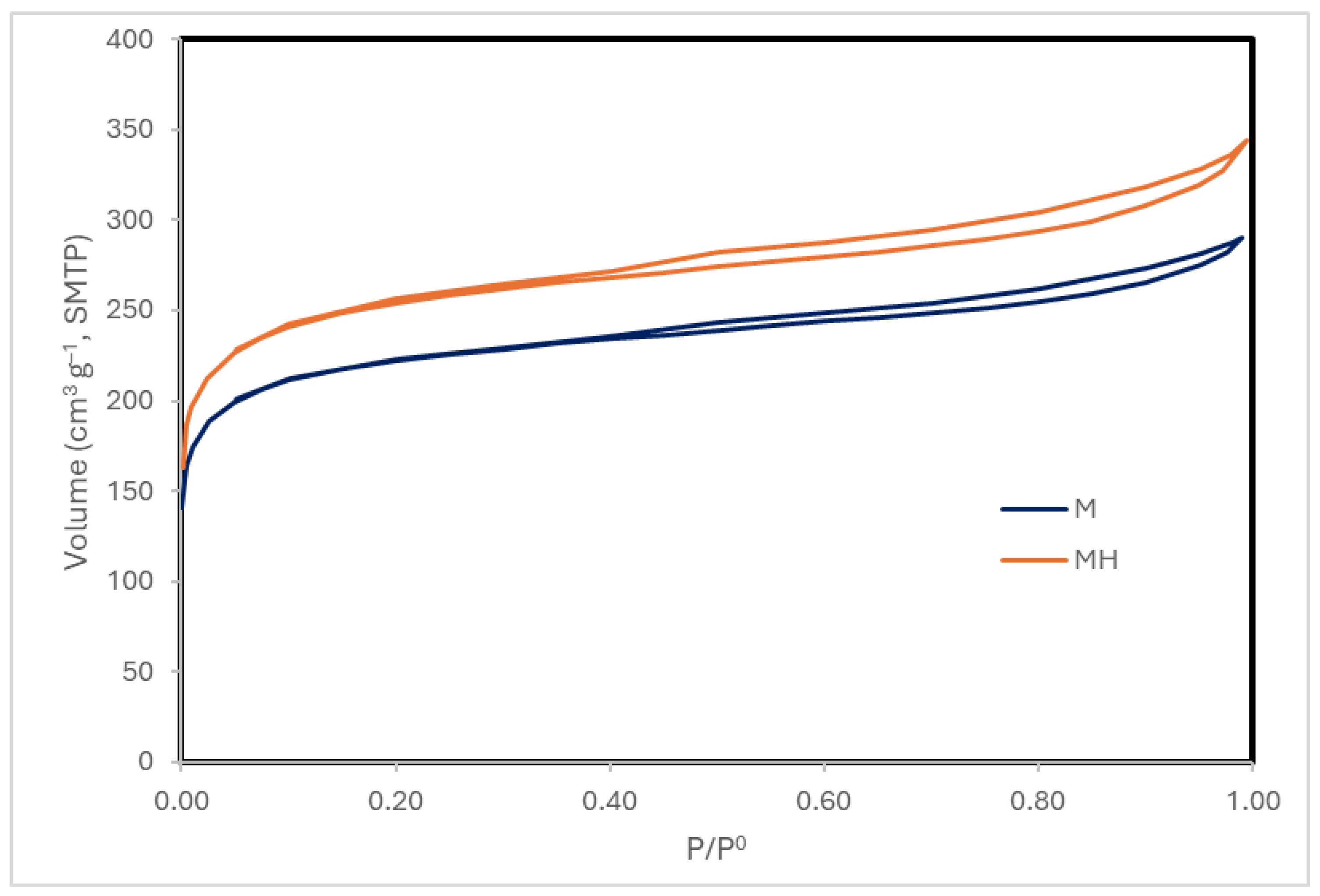

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (

Figure 3) demonstrate that both samples exhibit type IV isotherms with H4 hysteresis loops [

45], typical of micro-mesoporous carbonaceous materials. MH displays a higher total N

2 uptake.

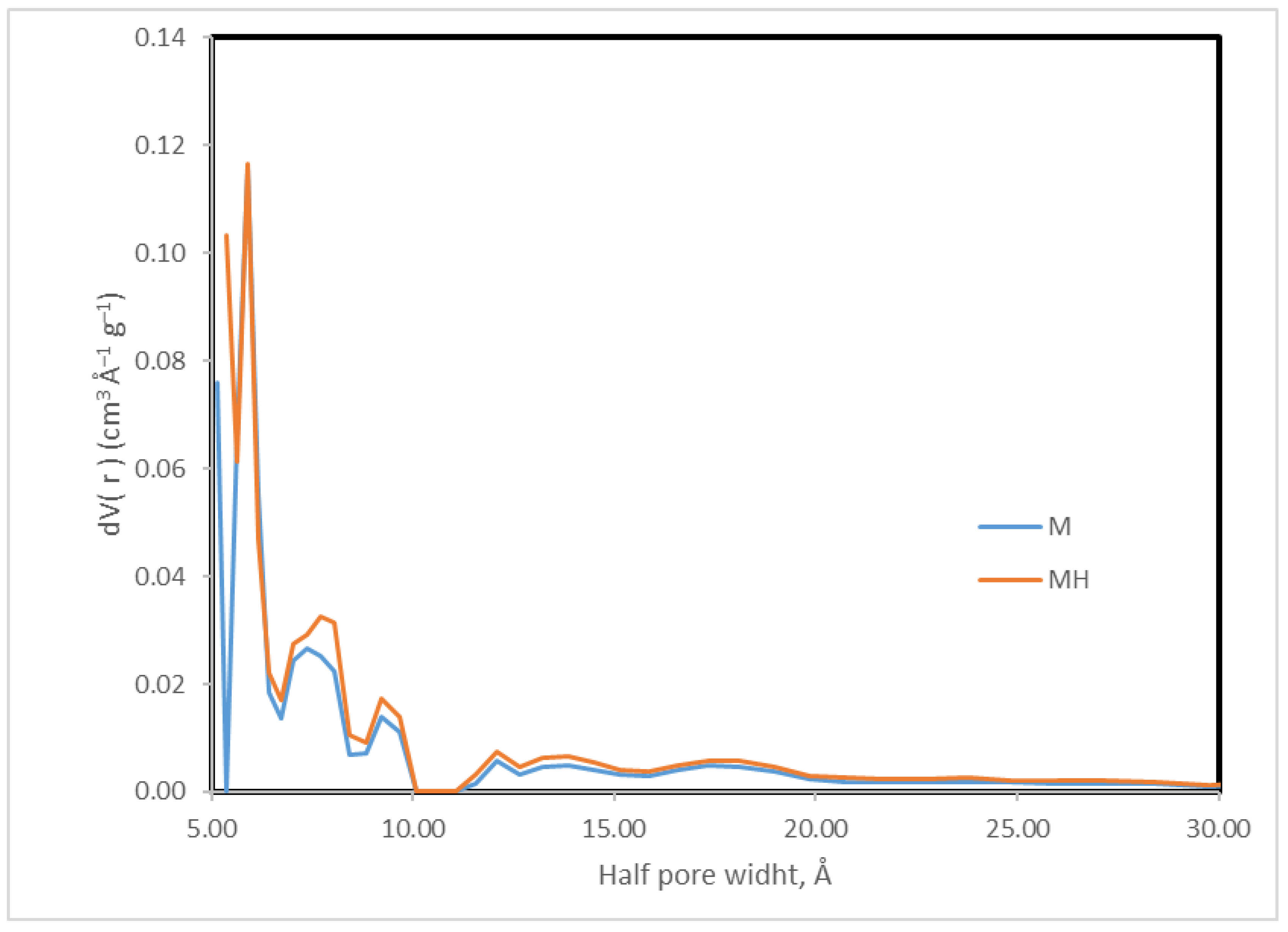

Although MH shows a slight decrease in surface area, it exhibits higher micropore and mesopore volumes, which contribute to its improved adsorption performance. The pore size distribution (

Table 6,

Figure 4) further indicates a broader and slightly larger distribution in MH. In contrast, SEM micrographs (

Figures S1 and S2, Supplementary Information) do not reveal any substantial morphological alterations.

Adsorption Experiments

The adsorption kinetics of acetaminophen (APAP) were evaluated using both adsorbent materials, M and MH, under varying pH (5, 6, and 7) and temperature conditions (30 °C and 40 °C). These parameters were selected to simulate hospital wastewater discharge scenarios, where APAP concentrations might be elevated. At these pH levels, APAP (pK

a = 9.5) [

46], predominantly exists in its neutral molecular form.

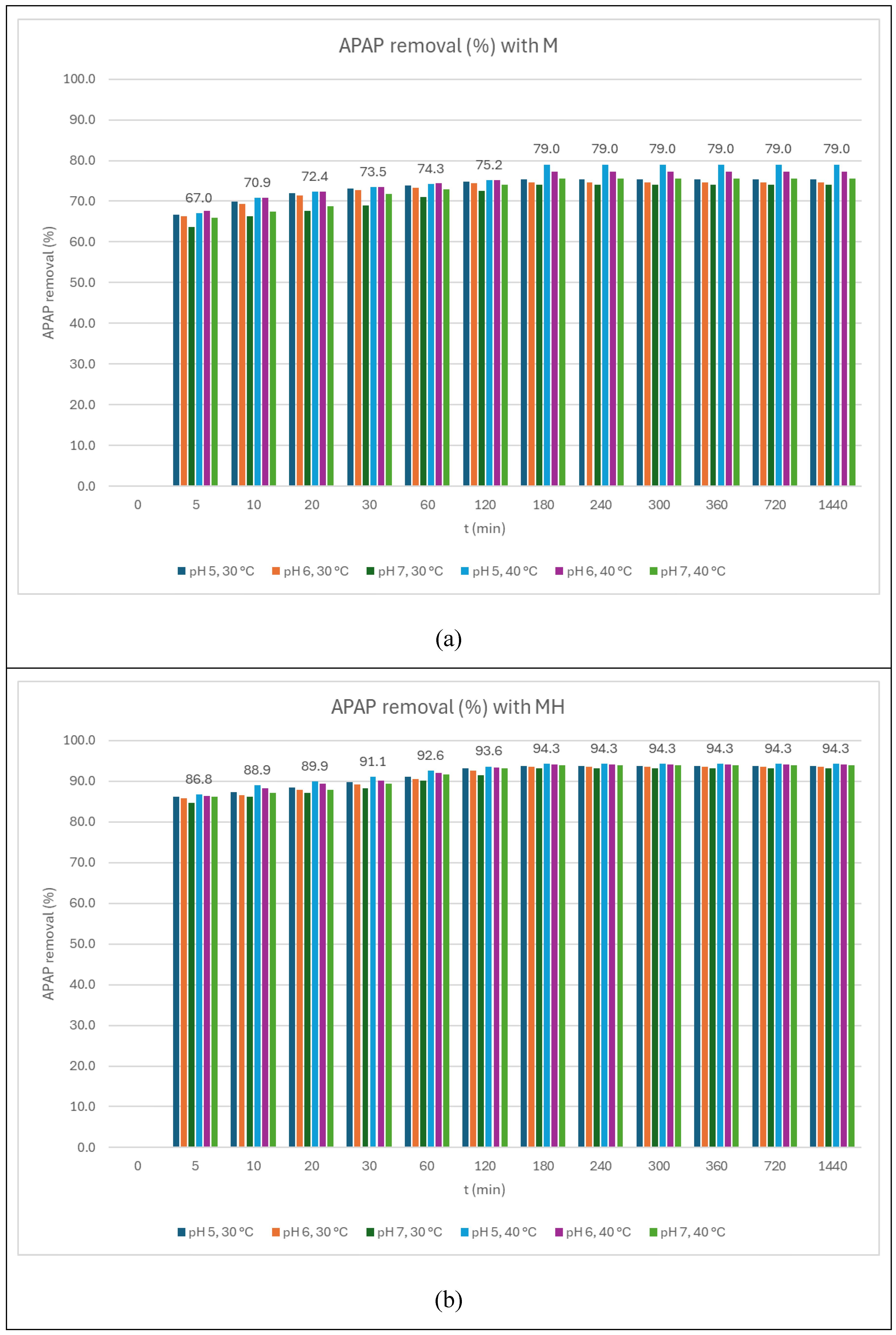

As shown in

Figure 5(a) and 5(b), adsorption equilibrium was reached within 180 minutes for both adsorbents. MH consistently exhibited a significantly higher adsorption capacity than M across all conditions, with differences exceeding 15 percentage points. This enhanced performance is attributed to improved pore accessibility and surface chemistry introduced by hydrothermal treatment, which likely increases the availability of active sites. These conditions facilitate stronger adsorbate–adsorbent interactions, such as, π–π stacking, particularly relevant at pH values where APAP remains neutral. The sharper initial removal rates for MH suggest reduced diffusion resistance and improved mass transport properties.

To elucidate the adsorption mechanism, the kinetic data were fitted to pseudo-first order and pseudo-second-order models:

(1)

(2)Where qt is the amount of adsorbate adsorbed at time t (mg/g); qe is the amount of adsorbate adsorbed in equilibrium; ki is the kinetic constant of the model (pseudo-first order: min -1 pseudo-second order: g/mg min); t is the time (min).

The pseudo-second-order model provided a significantly better fit across all experimental conditions (R² > 0.99). For example, under the MH_40_pH5 condition, an R² of 0.9995 was obtained, with a rate constant

k = 0.2413 min⁻¹ and a calculated equilibrium removal of 94.3%. The kinetic parameters obtained are shown in

Table 7.

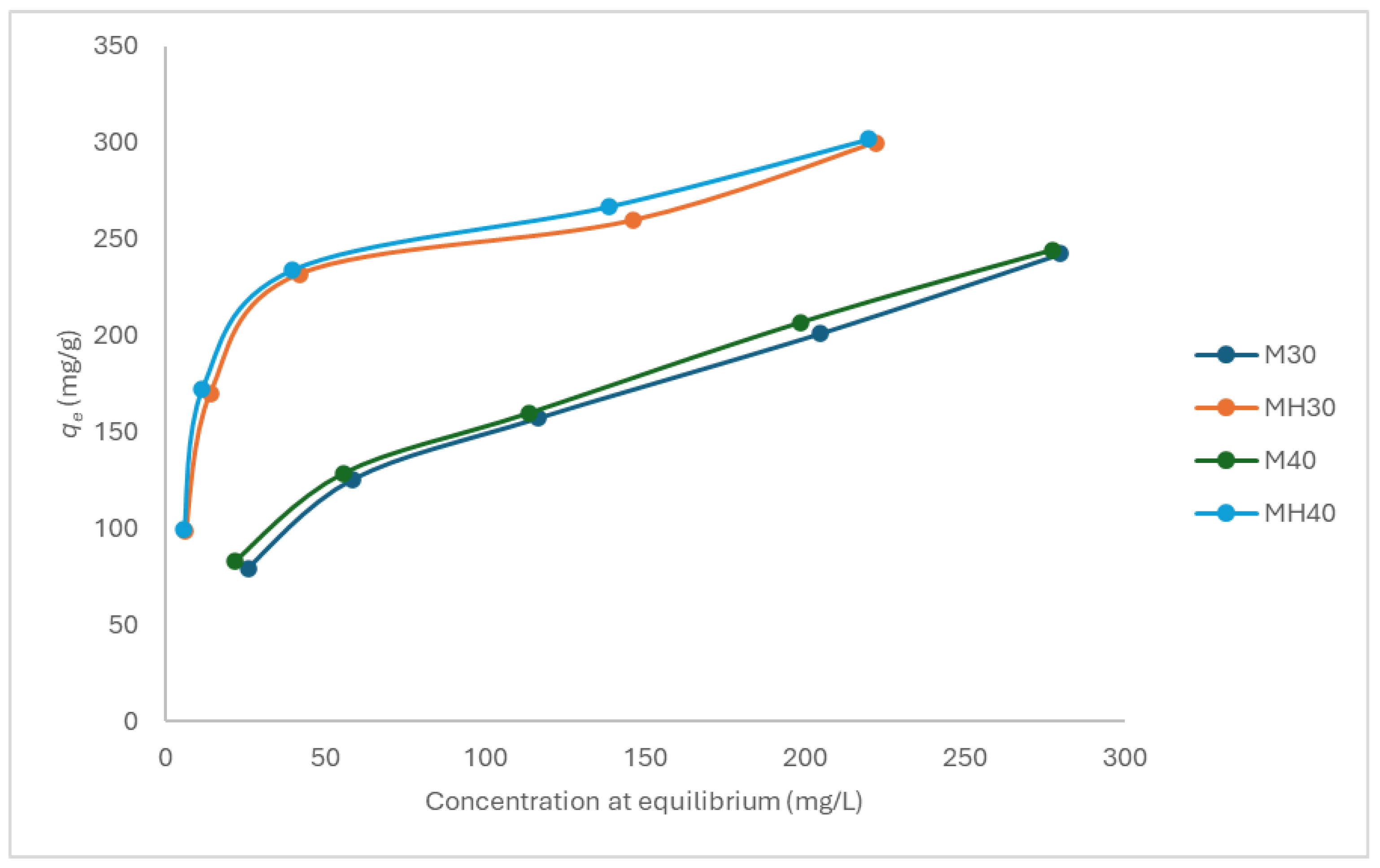

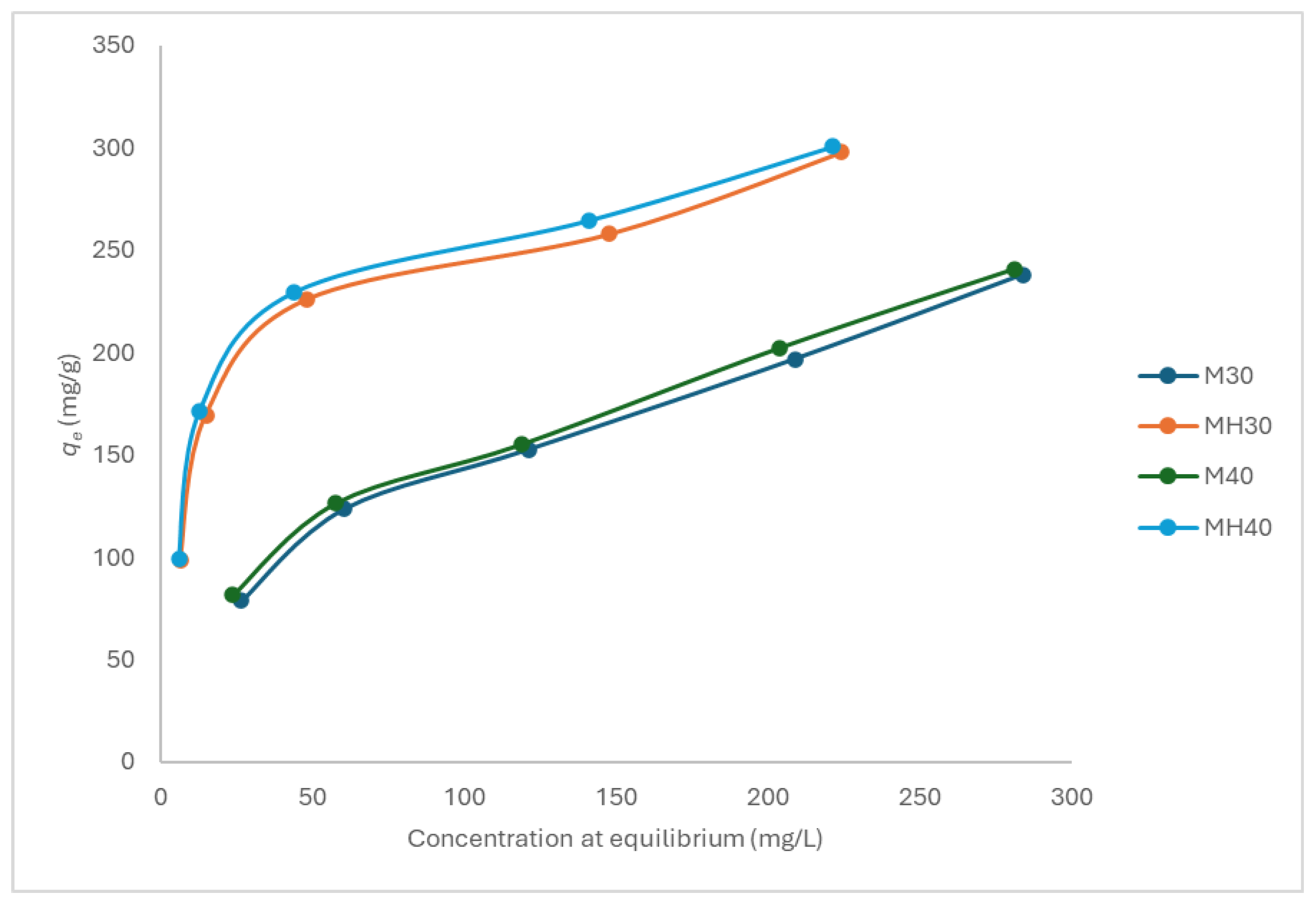

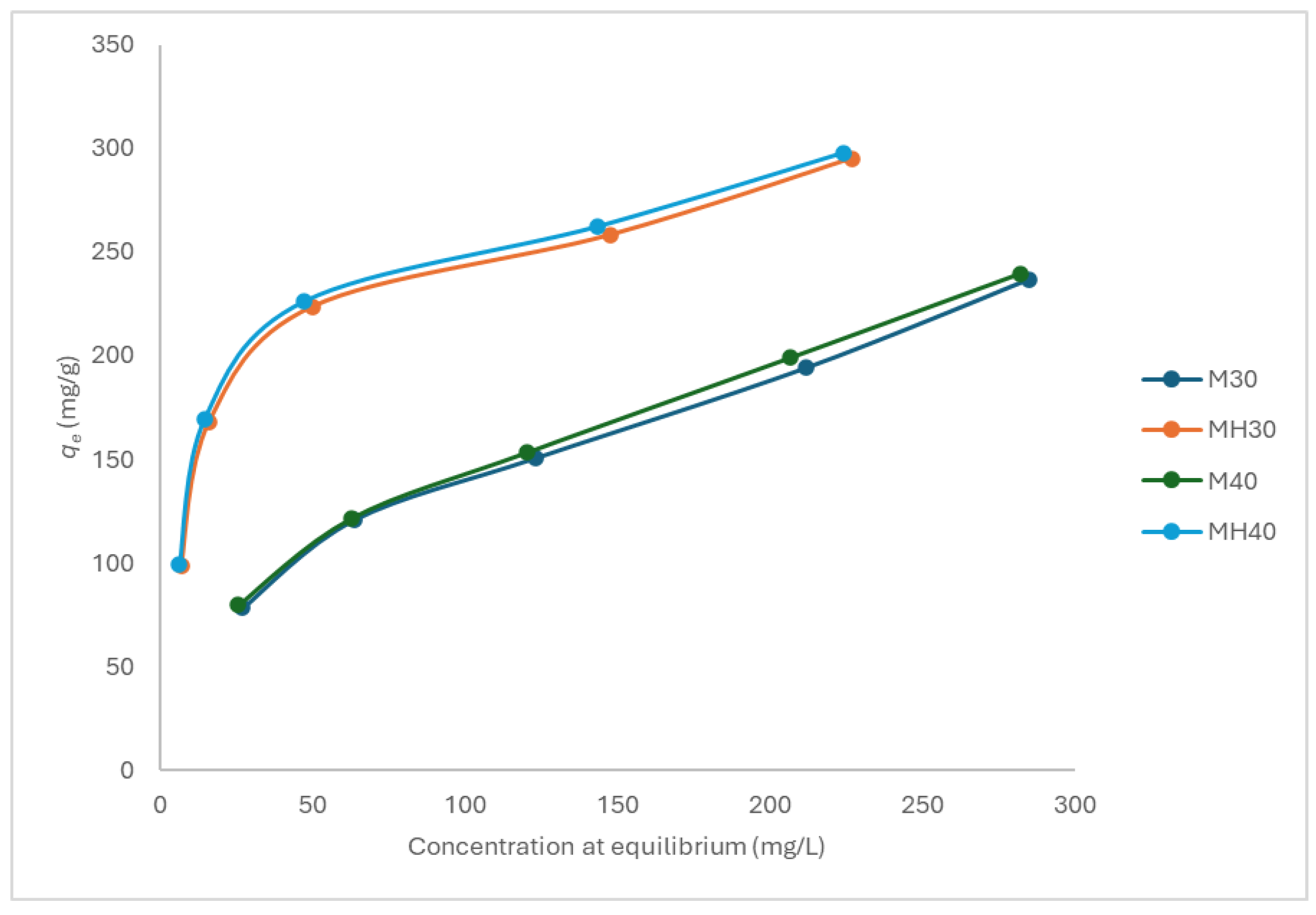

Equilibrium adsorption isotherms were obtained at pH 5, 6, and 7, and at 30 °C and 40 °C, for both materials (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). MH consistently outperformed M, with adsorption efficiency increasing by up to 19.9%. Higher temperature favored adsorption, consistent with an endothermic process.

The equilibrium data were modeled using the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms (

Table 8):

(3) Where K L is the Langmuir constant and S m is the adsorption capacity of a monolayer on the adsorbent.

(4) Where K F is the Freundlich constant that increases with the capacity of the adsorbent.

Carbon M fits the Freundlich model more closely, suggesting a heterogeneous surface with multiple active site types. In contrast, MH adheres better to the Langmuir model, indicating a more uniform surface chemistry and monolayer adsorption behavior. Despite similar monolayer capacities, experimental adsorption was consistently higher for MH. The Freundlich parameter n, which reflects adsorption favorability, was lower for MH, yet experimental results contradicted this, further supporting that different materials may align with different mechanistic models. As they respond to different mechanisms, the comparison of these parameters may not be correct.

To assess performance at higher concentrations, the effect of initial APAP concentration was evaluated.

Table 9 summarizes these results. At low concentrations (100 mg/L), MH removed >93% of APAP across all conditions. Even at 500 mg/L, MH maintained a removal efficiency >57%, significantly outperforming M.

In conclusion, MH exhibits superior adsorption performance primarily due to changes in textural and chemical properties induced by hydrothermal treatment. The influence of temperature and pH, while present, is comparatively secondary. Adsorption is slightly more favorable at lower pH due to speciation effects and is enhanced at higher temperatures, suggesting an endothermic mechanism.

Computational Study

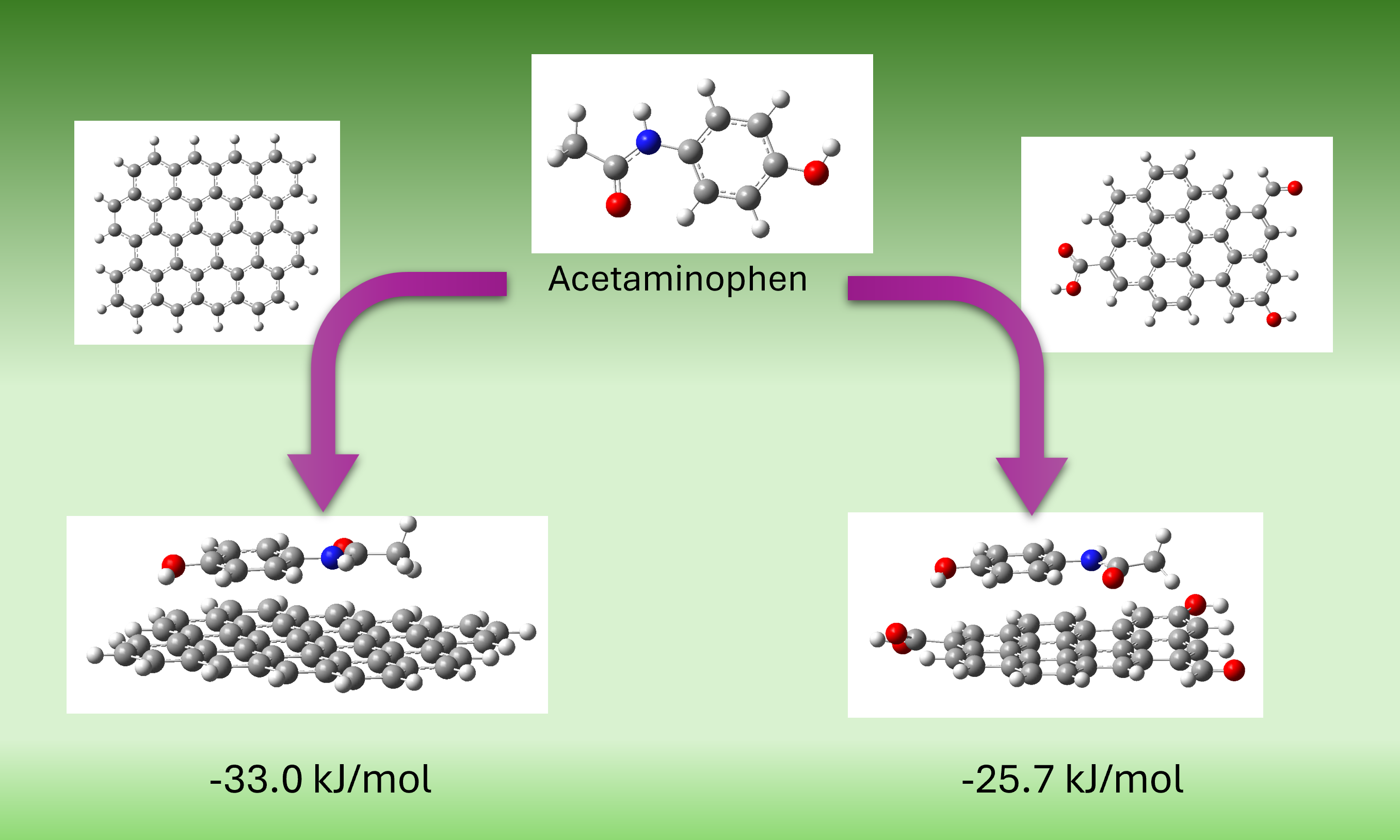

To gain further insight into the adsorptive interactions between APAP and the carbonaceous materials, a computational study was conducted using graphene and oxidized graphene models (see Supplementary Information,

Figure S3). Geometry optimization was performed as outlined in the Experimental section. The oxidized graphene model included representative hydroxyl, carbonyl, and carboxylic functional groups.

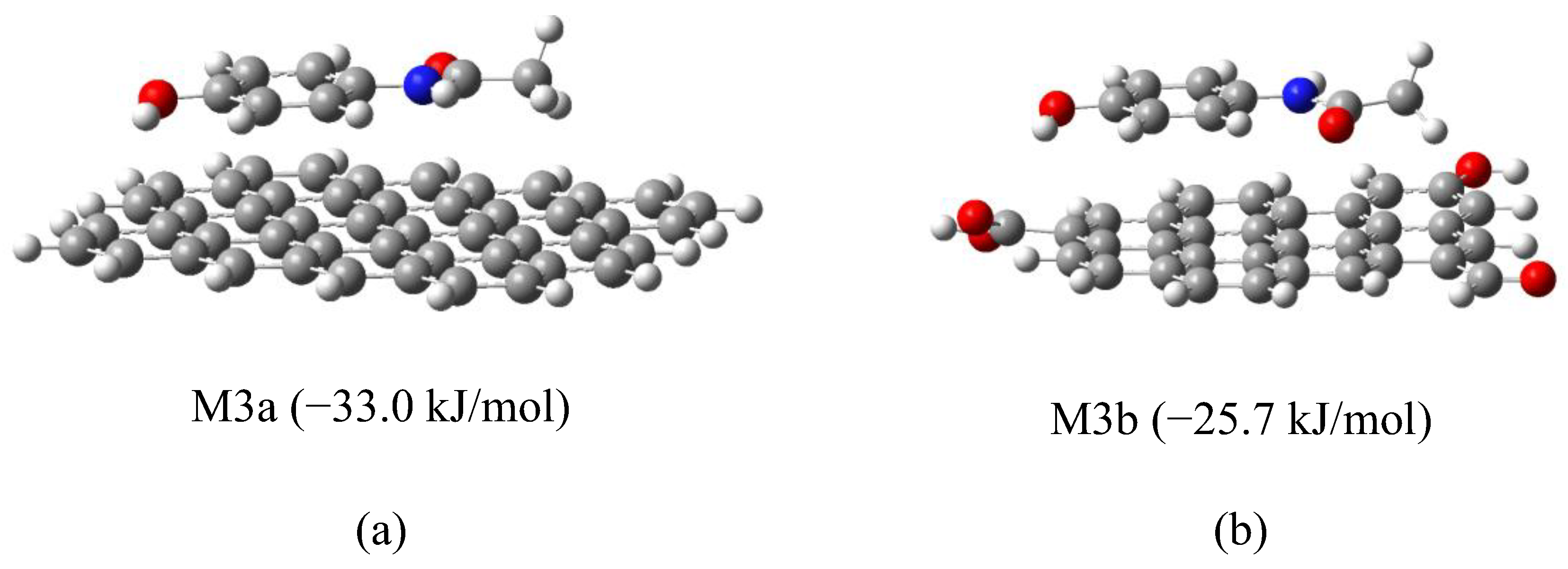

The most stable configuration (model M3a) corresponded to a coplanar π–π stacking interaction between APAP and non-oxidized graphene, with a calculated free energy of adsorption of −33.0 kJ/mol (

Figure 9(a)). In comparison, the analogous interaction with oxidized graphene (model M3b) yielded a less favorable ΔG of −25.7 kJ/mol (

Figure 9(b)). This result is consistent with experimental findings, in which MH (lower oxygen content) exhibited higher adsorption capacity than M. However, it is noteworthy that this trend is not universal; for instance, prior simulations with phenol demonstrated enhanced adsorption on oxidized graphene [

47].

Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis revealed four significant interactions (>0.5 kcal/mol) in M3a versus two in M3b. These were primarily π–π stacking interactions, although one donor–acceptor interaction between APAP hydroxyl groups and graphene aromatic carbons is present as well. The stability of M3a suggests that π–π stacking dominates the adsorption mechanism.

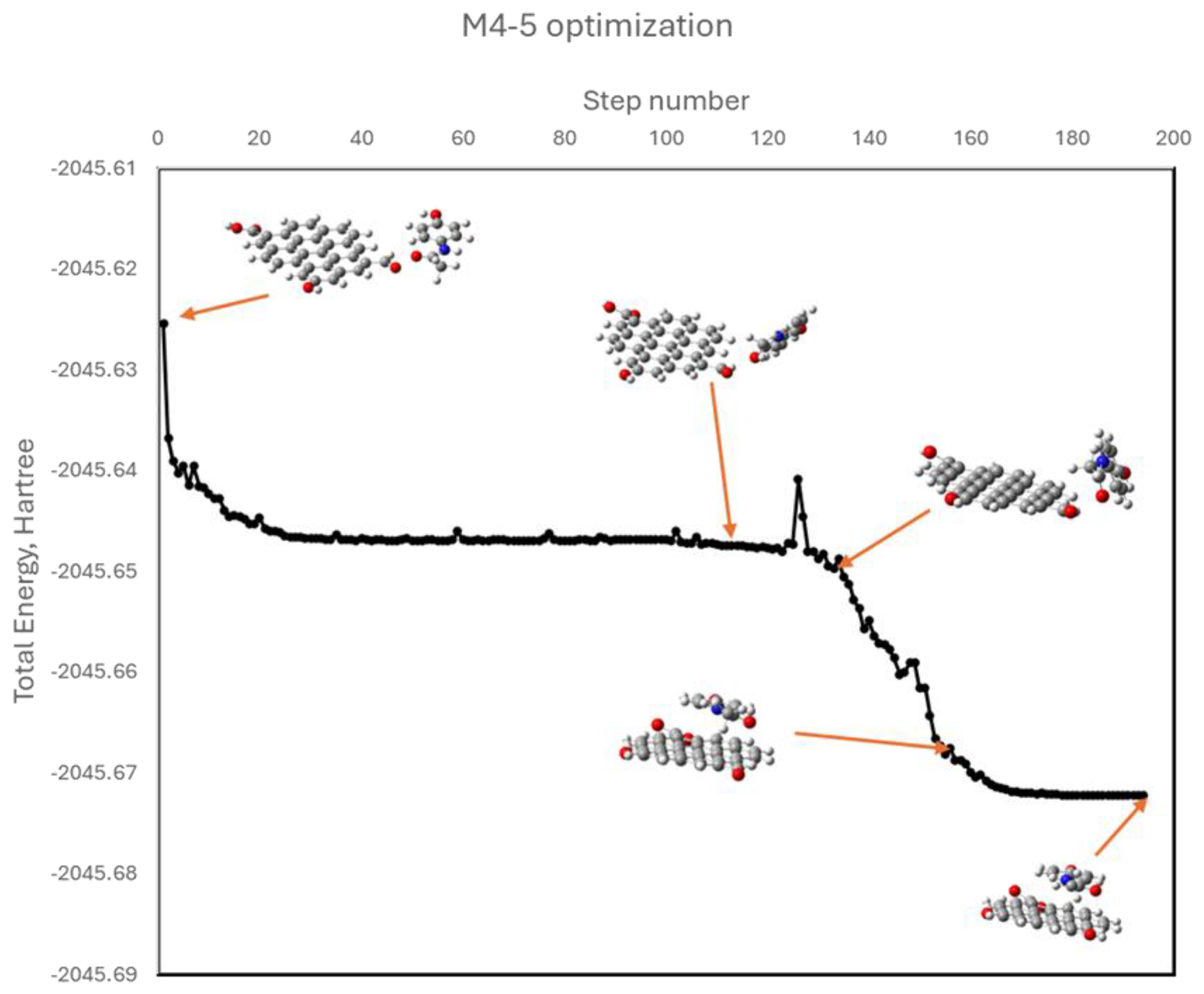

To isolate the role of dipolar interactions, additional models (M4-1 to M4-6) were constructed in which APAP functional groups (hydroxyl or acetamide) were positioned near oxygenated groups on graphene (hydroxyl, carbonyl, or carboxyl), intentionally avoiding initial π–π stacking. During optimization, some systems (M4-2, M4-5) evolved into π–π stacked conformations, indicating a thermodynamic preference for these interactions. This can be better appreciated in

Figure 10. The APAP molecule is initially facing a graphene’s carbonyl group (model M4-5), yet as geometry optimization develops, it keeps moving to find the most stable position located in a parallel plane above the graphene model. Others (M4-1, M4-3) retained dipolar contact but exhibited positive or near-zero ΔG values, suggesting less favorable adsorption. Finally, in the other two cases (M4-4 y M4-6), an intermediate situation was reached.

Figure 11 shows the optimized geometries for all these models.

These results suggest that although dipole interactions may contribute to adsorption under certain conditions, the dominant interaction mechanism for APAP on carbonaceous materials is π–π stacking. The relatively small energy differences among various binding sites further support the experimental observation that surface structure and chemical homogeneity critically influence adsorption behavior.

Figure 1.

C 1s XPS spectra for (a) M and (b) MH.

Figure 1.

C 1s XPS spectra for (a) M and (b) MH.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of M and MH.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of M and MH.

Figure 3.

N₂ adsorption isotherms at 77 K.

Figure 3.

N₂ adsorption isotherms at 77 K.

Figure 4.

Pore size distribution (DFT method).

Figure 4.

Pore size distribution (DFT method).

Figure 5.

APAP removal kinetics for (a) M and (b) MH. Numeric data from pH 5, 40 ºC experiment.

Figure 5.

APAP removal kinetics for (a) M and (b) MH. Numeric data from pH 5, 40 ºC experiment.

Figure 6.

Adsorption isotherm for APAP onto M and MH at pH 5, 30 °C and 40 °C.

Figure 6.

Adsorption isotherm for APAP onto M and MH at pH 5, 30 °C and 40 °C.

Figure 7.

Adsorption isotherm for APAP onto M and MH at pH 6, 30 °C and 40 °C.

Figure 7.

Adsorption isotherm for APAP onto M and MH at pH 6, 30 °C and 40 °C.

Figure 8.

Adsorption isotherm for APAP onto M and MH at pH 7, 30 °C and 40 °C.

Figure 8.

Adsorption isotherm for APAP onto M and MH at pH 7, 30 °C and 40 °C.

Figure 9.

Optimized geometries of APAP interaction with (a) non-oxidized (M3a) and (b) oxidized graphene (M3b).

Figure 9.

Optimized geometries of APAP interaction with (a) non-oxidized (M3a) and (b) oxidized graphene (M3b).

Figure 10.

Optimization trajectory of model M4-5 showing APAP shifting into π–π stacked conformation.

Figure 10.

Optimization trajectory of model M4-5 showing APAP shifting into π–π stacked conformation.

Figure 11.

Optimized geometries of APAP with oxidized graphene in models M4-1 through M4-6, with corresponding ΔG values.

Figure 11.

Optimized geometries of APAP with oxidized graphene in models M4-1 through M4-6, with corresponding ΔG values.

Table 1.

Proximate analysis (dry basis, wt%) of the carbon materials.

Table 1.

Proximate analysis (dry basis, wt%) of the carbon materials.

| Sample |

Fixed Carbon (%) |

Volatile Matter (%) |

Ash (%) |

| M |

92.62 |

3.41 |

3.97 |

| MH |

90.78 |

5.13 |

4.09 |

Table 2.

Elemental composition of the organic fraction (wt%).

Table 2.

Elemental composition of the organic fraction (wt%).

| Sample |

C (%) |

H (%) |

N (%) |

S (%) |

O a (%) |

| M |

81.54 |

2.12 |

0.77 |

0.71 |

14.86 |

| MH |

92.17 |

0.81 |

1.33 |

0.78 |

4.90 |

Table 3.

Surface elemental composition (atomic %) by XPS.

Table 3.

Surface elemental composition (atomic %) by XPS.

| Sample |

C 1s (%) |

O 1s (%) |

N 1s (%) |

S 2p (%) |

Si 2p (%) |

Al 2p (%) |

| M |

94.05 |

5.01 |

n.d. |

0.13 |

0.61 |

0.20 |

| MH |

94.22 |

4.12 |

0.78 |

0.30 |

0.58 |

n.d. |

Table 4.

Surface elemental composition (wt%) by XPS.

Table 4.

Surface elemental composition (wt%) by XPS.

| Sample |

C 1s |

O 1s |

N 1s |

S 2p |

Si 2p |

Al 2p |

| M |

91.36 |

6.48 |

0.00 |

0.34 |

1.39 |

0.44 |

| MH |

91.68 |

5.34 |

0.88 |

0.78 |

1.31 |

0.00 |

Table 5.

Components of the C 1s peak obtained by deconvolution.

Table 5.

Components of the C 1s peak obtained by deconvolution.

| |

B.E., eV (%) |

| M |

284.8 (52.75 %) |

285.7 (23.95 %) |

288.6 (23.3 %) |

| MH |

284.8 (74.69 %) |

286.5 (16.2 %) |

289.6 (9.11 %) |

Table 6.

Textural properties from N₂ isotherms.

Table 6.

Textural properties from N₂ isotherms.

| |

SBET

|

VDR

|

Vme

|

Vtotal

|

| |

m2/g |

cm3/g |

cm3/g |

cm3/g |

| M |

839.10 |

0.336 |

0.103 |

0.448 |

| MH |

808.26 |

0.384 |

0.130 |

0.533 |

| model |

BET |

DR |

DFT |

|

Table 7.

Kinetic parameters for APAP adsorption on M and MH.

Table 7.

Kinetic parameters for APAP adsorption on M and MH.

| |

|

M |

MH |

| |

|

30 °C |

40 °C |

30 °C |

40 °C |

| |

|

pH 5 |

pH 6 |

pH 7 |

pH 5 |

pH 6 |

pH 7 |

pH 5 |

pH 6 |

pH 7 |

pH 5 |

pH 6 |

pH 7 |

| P-first order |

qe

|

28.65 |

28.44 |

29.78 |

32.34 |

28.99 |

31.06 |

29.15 |

29.64 |

30.01 |

28.67 |

28.53 |

79.97 |

| k |

0.0981 |

0.1004 |

0.0693 |

0.0702 |

0.0797 |

0.0769 |

0.0785 |

0.0758 |

0.0721 |

0.0864 |

0.0797 |

0.0267 |

| R2

|

0.7293 |

0.7393 |

0.6019 |

0.6139 |

0.6339 |

0.6599 |

0.5487 |

0.5391 |

0.5202 |

0.5860 |

0.5446 |

0.4169 |

| P-second order |

qe

|

34.01 |

33.33 |

29.41 |

34.25 |

34.13 |

31.95 |

51.02 |

50.51 |

49.50 |

52.63 |

51.55 |

50.51 |

| k |

0.1882 |

0.1882 |

0.2058 |

0.1960 |

0.2067 |

0.1781 |

0.2489 |

0.2456 |

0.2608 |

0.2413 |

0.2640 |

0.2623 |

| R2

|

0.9976 |

0.9975 |

0.9975 |

0.9979 |

0.9983 |

0.9937 |

0.9995 |

0.9994 |

0.9996 |

0.9995 |

0.9997 |

0.9995 |

Table 8.

Isotherm model parameters for APAP adsorption.

Table 8.

Isotherm model parameters for APAP adsorption.

| |

|

|

Langmuir |

Freundlich |

| T, °C |

Carbon |

pH |

R2

|

Sm |

KL |

R2

|

KF |

n |

| 30 |

M |

7 |

0.9615 |

298.5 |

1.08·10-3

|

0.9930 |

1.96·10-3

|

0.4574 |

| 30 |

MH |

7 |

0.9945 |

307.7 |

1.81·10-3

|

0.9184 |

2.13·10-6

|

0.3125 |

| 40 |

M |

7 |

0.9654 |

302.1 |

1.01·10-3

|

0.9960 |

1.57·10-3

|

0.4507 |

| 40 |

MH |

7 |

0.9952 |

309.6 |

1.62·10-3

|

0.9168 |

1.28·10-6

|

0.3050 |

| 30 |

M |

6 |

0.9670 |

296.7 |

1.02·10-3

|

0.9903 |

1.65·10-3

|

0.4521 |

| 30 |

MH |

6 |

0.9930 |

308.6 |

1.70·10-4

|

0.9100 |

1.64·10-6

|

0.3086 |

| 40 |

M |

6 |

0.9676 |

294.1 |

9.25·10-4

|

0.9915 |

7.96·10-4

|

0.4276 |

| 40 |

MH |

6 |

0.9951 |

311.5 |

1.49·10-4

|

0.8982 |

1.22·10-6

|

0.3055 |

| 30 |

M |

5 |

0.9729 |

302.1 |

9.54·10-4

|

0.9918 |

1.60·10-3

|

0.4538 |

| 30 |

MH |

5 |

0.9931 |

308.6 |

1.55·10-4

|

0.8881 |

1.87·10-6

|

0.3125 |

| 40 |

M |

5 |

0.9732 |

295.0 |

8.43·10-4

|

0.9950 |

5.28·10-4

|

0.4162 |

| 40 |

MH |

5 |

0.9956 |

311.5 |

1.35·10-4

|

0.8766 |

1.21·10-6

|

0.3074 |

Table 9.

Influence of initial APAP concentration on adsorption performance.

Table 9.

Influence of initial APAP concentration on adsorption performance.

| Material |

Temperature (°C) |

Adsorption capacity (mg/g) |

Removal efficiency (%) |

| pH 5 |

pH 6 |

pH 7 |

pH 5 |

pH 6 |

pH 7 |

| [APAP] 100 mg/L |

| M |

30 |

79.44 |

78.70 |

78.15 |

75.30 |

74.60 |

74.10 |

| 40 |

83.33 |

81.48 |

79.63 |

79.00 |

77.30 |

75.50 |

| MH |

30 |

98.89 |

98.70 |

98.33 |

93.80 |

93.60 |

93.30 |

| 40 |

99.44 |

99.26 |

99.07 |

94.30 |

94.10 |

94.00 |

| [APAP] 500 mg/L |

| M |

30 |

242.35 |

238.15 |

236.98 |

46.4 |

45.60 |

45.40 |

| 40 |

244.63 |

240.74 |

239.88 |

46.90 |

46.10 |

45.90 |

| MH |

30 |

300.00 |

297.84 |

295.19 |

57.50 |

57.00 |

56.50 |

| 40 |

302.04 |

300.62 |

297.90 |

57.80 |

57.60 |

57.10 |