Submitted:

18 May 2023

Posted:

19 May 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

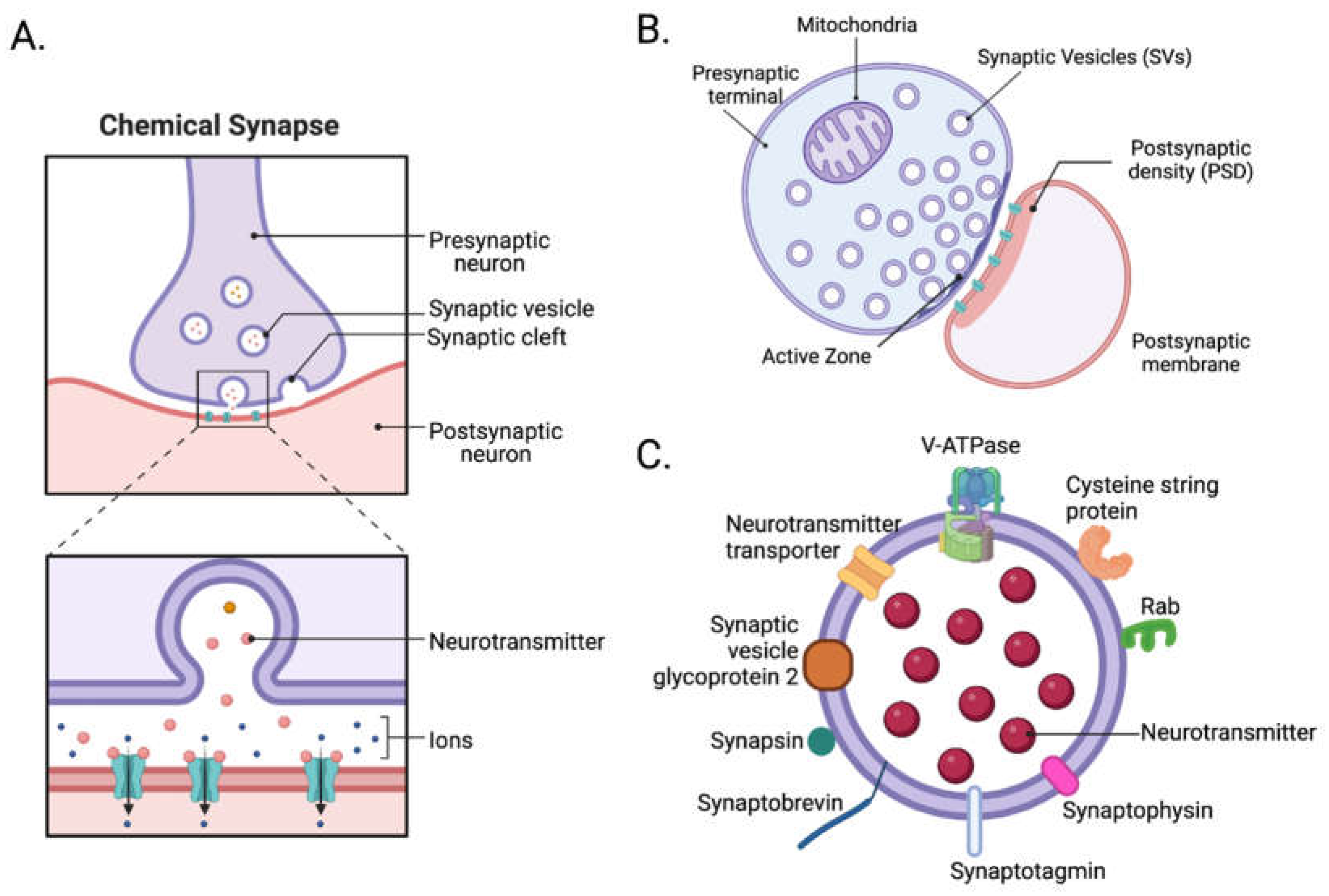

2. Synapses

2.1. Structure of Synapses

2.2. Isolation of Synapses

3. Advancements in Neuroproteomics

3.1. Isolation of Cell Types, Subcellular Compartments, and Cell-Type-Specific Synapses

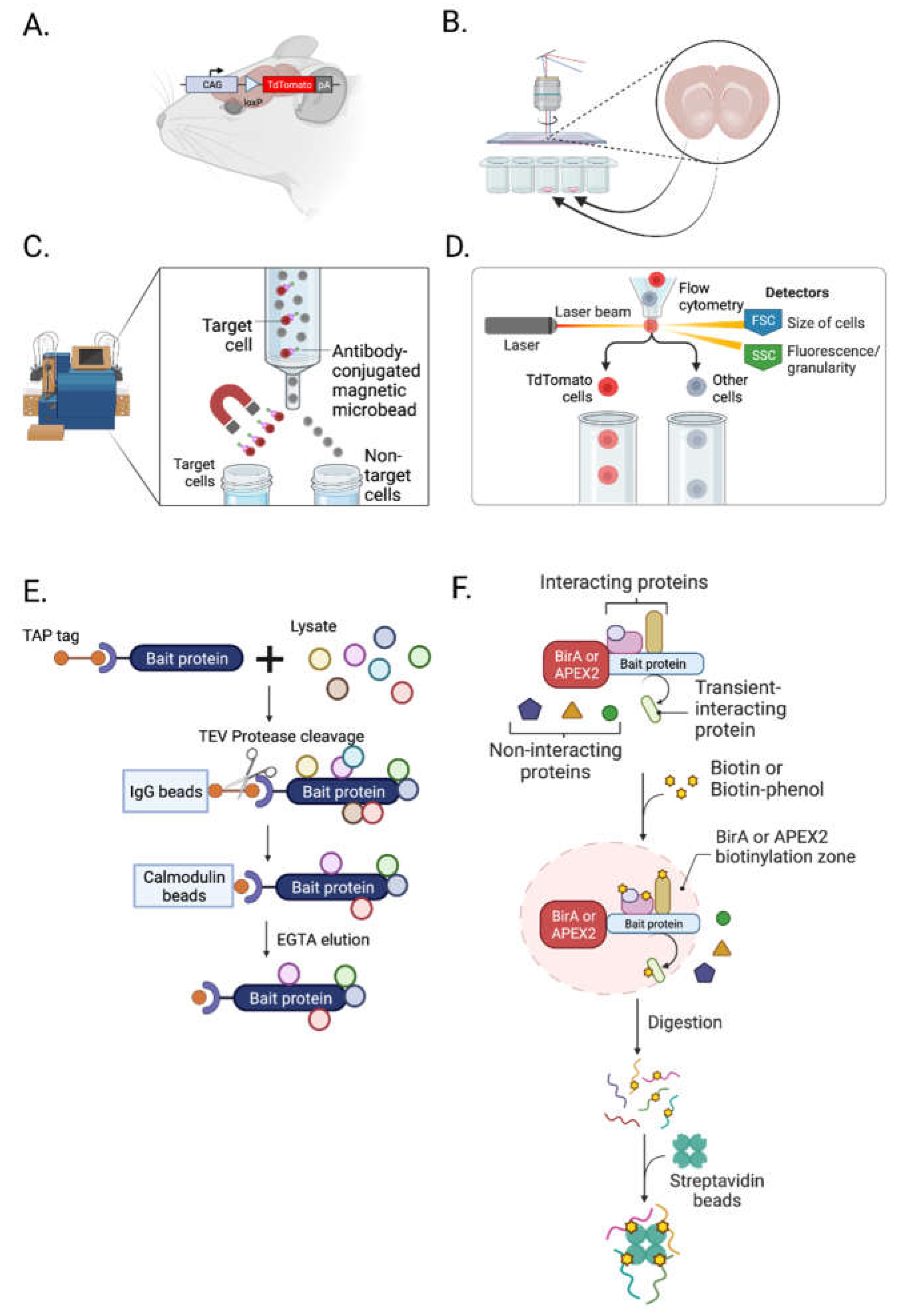

3.1.1. Transgenic Animals

3.1.2. Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM)

3.1.3. Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS)

3.1.4. Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

3.1.5. Tandem Affinity Purification

3.1.6. Protein Labeling

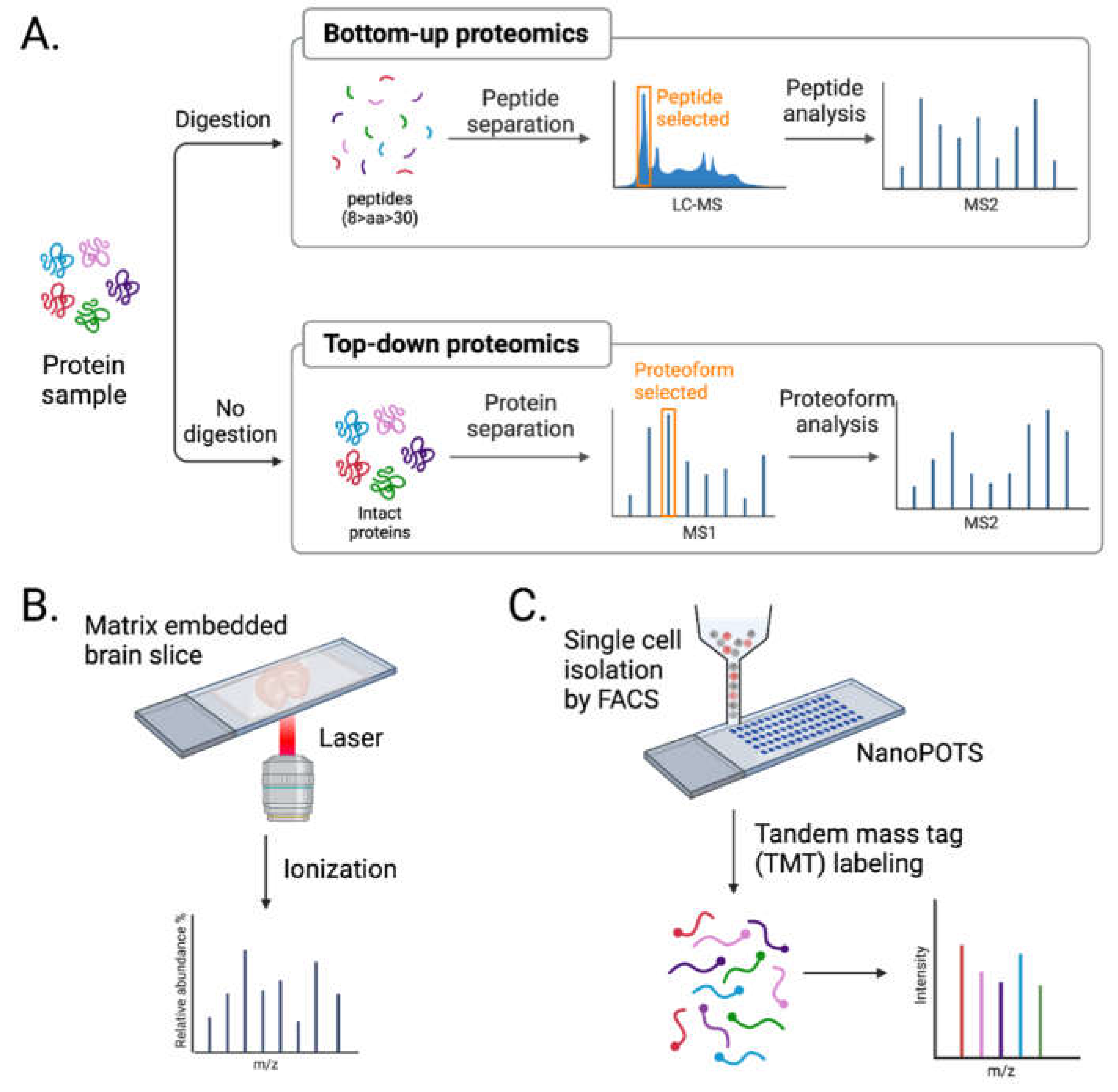

3.2. Advancements in MS Approaches

3.2.1. Direct in situ Spatial Proteomics

3.2.2. Single-Cell Mass Spectrometry

4. Application of Neuroproteomics Analysis to Neuropsychiatric Disorders

4.1. Autism Spectrum Disorder

4.2. Alzheimer‘s Disease

4.3. Schizophrenia

4.4. Major Depressive Disorder

4.5. Substance Use Disorders

5. Limitation and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, Y.; Song, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Li, J. Proteomic insights into synaptic signaling in the brain: the past, present and future. Mol Brain 2021, 14, 37. [CrossRef]

- Marcassa, G.; Dascenco, D.; de Wit, J. Proteomics-based synapse characterization: From proteins to circuits. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2023, 79, 102690. [CrossRef]

- Lake, J.; Storm, C.S.; Makarious, M.B.; Bandres-Ciga, S. Genetic and Transcriptomic Biomarkers in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Current Situation and the Road Ahead. Cells 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Husain, I.; Ahmad, W.; Ali, A.; Anwar, L.; Nuruddin, S.M.; Ashraf, K.; Kamal, M.A. Functional Neuroproteomics: An Imperative Approach for Unravelling Protein Implicated Complexities of Brain. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2021, 20, 613-624. [CrossRef]

- Alzate, O. Neuroproteomics. In Neuroproteomics, Alzate, O., Ed.; Frontiers in Neuroscience; Boca Raton (FL), 2010.

- Bai, F.; Witzmann, F.A. Synaptosome proteomics. Subcell Biochem 2007, 43, 77-98. [CrossRef]

- Bayes, A.; Grant, S.G. Neuroproteomics: understanding the molecular organization and complexity of the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009, 10, 635-646. [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, N.; Uy, J.; Singh, K.K. Emerging proteomic approaches to identify the underlying pathophysiology of neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. Mol Autism 2020, 11, 27. [CrossRef]

- Caire, M.J.; Reddy, V.; Varacallo, M. Physiology, Synapse. In StatPearls; Treasure Island (FL), 2023.

- Landgraf, P.; Antileo, E.R.; Schuman, E.M.; Dieterich, D.C. BONCAT: metabolic labeling, click chemistry, and affinity purification of newly synthesized proteomes. Methods Mol Biol 2015, 1266, 199-215. [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, F.; van Nierop, P.; Andres-Alonso, M.; Byrnes, A.; Cijsouw, T.; Coba, M.P.; Cornelisse, L.N.; Farrell, R.J.; Goldschmidt, H.L.; Howrigan, D.P.; et al. SynGO: An Evidence-Based, Expert-Curated Knowledge Base for the Synapse. Neuron 2019, 103, 217-234 e214. [CrossRef]

- van Gelder, C.; Altelaar, M. Neuroproteomics of the Synapse: Subcellular Quantification of Protein Networks and Signaling Dynamics. Mol Cell Proteomics 2021, 20, 100087. [CrossRef]

- Natividad, L.A.; Buczynski, M.W.; McClatchy, D.B.; Yates, J.R., 3rd. From Synapse to Function: A Perspective on the Role of Neuroproteomics in Elucidating Mechanisms of Drug Addiction. Proteomes 2018, 6. [CrossRef]

- Martins-de-Souza, D. Proteomics, metabolomics, and protein interactomics in the characterization of the molecular features of major depressive disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2014, 16, 63-73. [CrossRef]

- Abul-Husn, N.S.; Devi, L.A. Neuroproteomics of the synapse and drug addiction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2006, 318, 461-468. [CrossRef]

- Paget-Blanc, V.; Pfeffer, M.E.; Pronot, M.; Lapios, P.; Angelo, M.F.; Walle, R.; Cordelieres, F.P.; Levet, F.; Claverol, S.; Lacomme, S.; et al. A synaptomic analysis reveals dopamine hub synapses in the mouse striatum. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 3102. [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, D.; Kater, M.S.J.; Sakers, K.; Nygaard, K.R.; Liu, Y.; Koester, S.K.; Fass, S.B.; Lake, A.M.; Khazanchi, R.; Khankan, R.R.; et al. Activity-dependent translation dynamically alters the proteome of the perisynaptic astrocyte process. Cell Rep 2022, 41, 111474. [CrossRef]

- Bradberry, M.M.; Mishra, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, L.; McKetney, J.M.; Vestling, M.M.; Coon, J.J.; Chapman, E.R. Rapid and Gentle Immunopurification of Brain Synaptic Vesicles. J Neurosci 2022, 42, 3512-3522. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Schmitt, S.; Bergner, C.G.; Tyanova, S.; Kannaiyan, N.; Manrique-Hoyos, N.; Kongi, K.; Cantuti, L.; Hanisch, U.K.; Philips, M.A.; et al. Cell type- and brain region-resolved mouse brain proteome. Nat Neurosci 2015, 18, 1819-1831. [CrossRef]

- Scofield, M.D.; Li, H.; Siemsen, B.M.; Healey, K.L.; Tran, P.K.; Woronoff, N.; Boger, H.A.; Kalivas, P.W.; Reissner, K.J. Cocaine Self-Administration and Extinction Leads to Reduced Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Expression and Morphometric Features of Astrocytes in the Nucleus Accumbens Core. Biol Psychiatry 2016, 80, 207-215. [CrossRef]

- Schoch, S.; Gundelfinger, E.D. Molecular organization of the presynaptic active zone. Cell Tissue Res 2006, 326, 379-391. [CrossRef]

- Sudhof, T.C. The synaptic vesicle cycle. Annu Rev Neurosci 2004, 27, 509-547. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, R.G.; Bellen, H.J. Hauling t-SNAREs on the microtubule highway. Nat Cell Biol 2004, 6, 918-919. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.P.; Sudhof, T.C. Cell biology of Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2010, 22, 496-505. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Kim, K.T. Short-term plasticity of small synaptic vesicle (SSV) and large dense-core vesicle (LDCV) exocytosis. Cell Signal 2009, 21, 1465-1470. [CrossRef]

- Dresbach, T.; Qualmann, B.; Kessels, M.M.; Garner, C.C.; Gundelfinger, E.D. The presynaptic cytomatrix of brain synapses. Cell Mol Life Sci 2001, 58, 94-116. [CrossRef]

- Sudhof, T.C. Neurotransmitter release: the last millisecond in the life of a synaptic vesicle. Neuron 2013, 80, 675-690. [CrossRef]

- Perea, G.; Navarrete, M.; Araque, A. Tripartite synapses: astrocytes process and control synaptic information. Trends Neurosci 2009, 32, 421-431. [CrossRef]

- Farhy-Tselnicker, I.; Allen, N.J. Astrocytes, neurons, synapses: a tripartite view on cortical circuit development. Neural Dev 2018, 13, 7. [CrossRef]

- Chelini, G.; Pantazopoulos, H.; Durning, P.; Berretta, S. The tetrapartite synapse: a key concept in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry 2018, 50, 60-69. [CrossRef]

- Kruyer, A.; Chioma, V.C.; Kalivas, P.W. The Opioid-Addicted Tetrapartite Synapse. Biol Psychiatry 2020, 87, 34-43. [CrossRef]

- Chaves Filho, A.J.M.; Mottin, M.; Los, D.B.; Andrade, C.H.; Macedo, D.S. The tetrapartite synapse in neuropsychiatric disorders: Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) as promising targets for treatment and rational drug design. Biochimie 2022, 201, 79-99. [CrossRef]

- Murthy, V.N.; De Camilli, P. Cell biology of the presynaptic terminal. Annu Rev Neurosci 2003, 26, 701-728. [CrossRef]

- Yim, Y.Y.; Zurawski, Z.; Hamm, H. GPCR regulation of secretion. Pharmacol Ther 2018, 192, 124-140. [CrossRef]

- Lepeta, K.; Lourenco, M.V.; Schweitzer, B.C.; Martino Adami, P.V.; Banerjee, P.; Catuara-Solarz, S.; de La Fuente Revenga, M.; Guillem, A.M.; Haidar, M.; Ijomone, O.M.; et al. Synaptopathies: synaptic dysfunction in neurological disorders - A review from students to students. J Neurochem 2016, 138, 785-805. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.; Kim, E. The postsynaptic organization of synapses. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011, 3. [CrossRef]

- Sudhof, T.C. Towards an Understanding of Synapse Formation. Neuron 2018, 100, 276-293. [CrossRef]

- Loh, K.H.; Stawski, P.S.; Draycott, A.S.; Udeshi, N.D.; Lehrman, E.K.; Wilton, D.K.; Svinkina, T.; Deerinck, T.J.; Ellisman, M.H.; Stevens, B.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Unbounded Cellular Compartments: Synaptic Clefts. Cell 2016, 166, 1295-1307 e1221. [CrossRef]

- Biederer, T.; Kaeser, P.S.; Blanpied, T.A. Transcellular Nanoalignment of Synaptic Function. Neuron 2017, 96, 680-696. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.Y.; Ichtchenko, K.; Sudhof, T.C.; Brose, N. Neuroligin 1 is a postsynaptic cell-adhesion molecule of excitatory synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999, 96, 1100-1105. [CrossRef]

- Linhoff, M.W.; Lauren, J.; Cassidy, R.M.; Dobie, F.A.; Takahashi, H.; Nygaard, H.B.; Airaksinen, M.S.; Strittmatter, S.M.; Craig, A.M. An unbiased expression screen for synaptogenic proteins identifies the LRRTM protein family as synaptic organizers. Neuron 2009, 61, 734-749. [CrossRef]

- Chih, B.; Gollan, L.; Scheiffele, P. Alternative Splicing Controls Selective Trans-Synaptic Interactions of the Neuroligin-Neurexin Complex. Neuron 2006, 51, 171-178. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Katayama, K.-i.; Sohya, K.; Miyamoto, H.; Prasad, T.; Matsumoto, Y.; Ota, M.; Yasuda, H.; Tsumoto, T.; Aruga, J.; et al. Selective control of inhibitory synapse development by Slitrk3-PTPδ trans-synaptic interaction. Nature Neuroscience 2012, 15, 389-398. [CrossRef]

- Varoqueaux, F.; Jamain, S.; Brose, N. Neuroligin 2 is exclusively localized to inhibitory synapses. European Journal of Cell Biology 2004, 83, 449-456. [CrossRef]

- Dunkley, P.R.; Robinson, P.J. Synaptosome Preparations: Which Procedure Should I Use? In Synaptosomes; Neuromethods; 2018; pp. 27-53.

- Gray, E.G.; Whittaker, V.P. The isolation of nerve endings from brain: an electron-microscopic study of cell fragments derived by homogenization and centrifugation. J Anat 1962, 96, 79-88.

- Dodd, P.R.; Hardy, J.A.; Oakley, A.E.; Edwardson, J.A.; Perry, E.K.; Delaunoy, J.P. A rapid method for preparing synaptosomes: comparison, with alternative procedures. Brain Res 1981, 226, 107-118. [CrossRef]

- Cotman, C.W.; Matthews, D.A. Synaptic plasma membranes from rat brain synaptosomes: isolation and partial characterization. Biochim Biophys Acta 1971, 249, 380-394. [CrossRef]

- Booth, R.F.; Clark, J.B. A rapid method for the preparation of relatively pure metabolically competent synaptosomes from rat brain. Biochem J 1978, 176, 365-370. [CrossRef]

- Dunkley, P.R.; Jarvie, P.E.; Robinson, P.J. A rapid Percoll gradient procedure for preparation of synaptosomes. Nat Protoc 2008, 3, 1718-1728. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, B.G.; Mandad, S.; Truckenbrodt, S.; Krohnert, K.; Schafer, C.; Rammner, B.; Koo, S.J.; Classen, G.A.; Krauss, M.; Haucke, V.; et al. Composition of isolated synaptic boutons reveals the amounts of vesicle trafficking proteins. Science 2014, 344, 1023-1028. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Holt, M.; Riedel, D.; Jahn, R. Small-scale isolation of synaptic vesicles from mammalian brain. Nat Protoc 2013, 8, 998-1009. [CrossRef]

- Hell, J.W.; Maycox, P.R.; Stadler, H.; Jahn, R. Uptake of GABA by rat brain synaptic vesicles isolated by a new procedure. EMBO J 1988, 7, 3023-3029. [CrossRef]

- Chantranupong, L.; Saulnier, J.L.; Wang, W.; Jones, D.R.; Pacold, M.E.; Sabatini, B.L. Rapid purification and metabolomic profiling of synaptic vesicles from mammalian brain. Elife 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Muzumdar, M.D.; Tasic, B.; Miyamichi, K.; Li, L.; Luo, L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. genesis 2007, 45, 593-605. [CrossRef]

- De Gasperi, R.; Rocher, A.B.; Sosa, M.A.G.; Wearne, S.L.; Perez, G.M.; Friedrich Jr, V.L.; Hof, P.R.; Elder, G.A. The IRG mouse: A two-color fluorescent reporter for assessing Cre-mediated recombination and imaging complex cellular relationships in situ. genesis 2008, 46, 308-317. [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, H.; Koizumi, K.; Kaneko, R.; Ikeda, K.; Egawa, R.; Yanagawa, Y.; Muramatsu, S.-i.; Onimaru, H.; Ishizuka, T.; Yawo, H. A Novel Reporter Rat Strain That Conditionally Expresses the Bright Red Fluorescent Protein tdTomato. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0155687. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yu, L.; Pan, S.; Gao, S.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X.; Dong, W.; Li, J.; Zhou, R.; Huang, L.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeting of the Rosa26 locus produces Cre reporter rat strains for monitoring Cre–loxP-mediated lineage tracing. The FEBS Journal 2017, 284, 3262-3277. [CrossRef]

- Bryda, E.C.; Men, H.; Davis, D.J.; Bock, A.S.; Shaw, M.L.; Chesney, K.L.; Hankins, M.A. A novel conditional ZsGreen-expressing transgenic reporter rat strain for validating Cre recombinase expression. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 13330. [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Endo, H.; Ajiki, T.; Hakamata, Y.; Okada, T.; Murakami, T.; Kobayashi, E. Establishment of Cre/LoxP recombination system in transgenic rats. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2004, 319, 1197-1202. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, M.; Im, S.-K.; Fang, S. Mouse Cre-LoxP system: general principles to determine tissue-specific roles of target genes. lar 2018, 34, 147-159. [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.A.; Hirokawa, K.E.; Sorensen, S.A.; Gu, H.; Mills, M.; Ng, L.L.; Bohn, P.; Mortrud, M.; Ouellette, B.; Kidney, J.; et al. Anatomical characterization of Cre driver mice for neural circuit mapping and manipulation. Frontiers in Neural Circuits 2014, 8. [CrossRef]

- Shcholok, T.; Eftekharpour, E. Cre-recombinase systems for induction of neuron-specific knockout models: a guide for biomedical researchers. Neural Regen Res 2023, 18, 273-279. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, Q.; Chen-Tsai, R.Y. Establishment of a Cre-rat resource for creating conditional and physiological relevant models of human diseases. Transgenic Research 2021, 30, 91-104. [CrossRef]

- Witten, Ilana B.; Steinberg, Elizabeth E.; Lee, Soo Y.; Davidson, Thomas J.; Zalocusky, Kelly A.; Brodsky, M.; Yizhar, O.; Cho, Saemi L.; Gong, S.; Ramakrishnan, C.; et al. Recombinase-Driver Rat Lines: Tools, Techniques, and Optogenetic Application to Dopamine-Mediated Reinforcement. Neuron 2011, 72, 721-733. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Brown, A.; Fisher, D.; Wu, Y.; Warren, J.; Cui, X. Tissue Specific Expression of Cre in Rat Tyrosine Hydroxylase and Dopamine Active Transporter-Positive Neurons. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0149379. [CrossRef]

- Espina, V.; Wulfkuhle, J.D.; Calvert, V.S.; VanMeter, A.; Zhou, W.; Coukos, G.; Geho, D.H.; Petricoin, E.F.; Liotta, L.A. Laser-capture microdissection. Nature Protocols 2006, 1, 586-603. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Piehowski, P.D.; Zhao, R.; Chen, J.; Shen, Y.; Moore, R.J.; Shukla, A.K.; Petyuk, V.A.; Campbell-Thompson, M.; Mathews, C.E.; et al. Nanodroplet processing platform for deep and quantitative proteome profiling of 10–100 mammalian cells. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 882. [CrossRef]

- Plum, S.; Steinbach, S.; Attems, J.; Keers, S.; Riederer, P.; Gerlach, M.; May, C.; Marcus, K. Proteomic characterization of neuromelanin granules isolated from human substantia nigra by laser-microdissection. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 37139. [CrossRef]

- Drummond, E.; Wisniewski, T. The use of localized proteomics to identify the drivers of Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Neural Regeneration Research 2017, 12.

- Nijholt, D.A.T.; Stingl, C.; Luider, T.M. Laser Capture Microdissection of Fluorescently Labeled Amyloid Plaques from Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Tissue for Mass Spectrometric Analysis. In Clinical Proteomics: Methods and Protocols, Vlahou, A., Makridakis, M., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2015; pp. 165-173.

- Garcia-Berrocoso, T.; Llombart, V.; Colas-Campas, L.; Hainard, A.; Licker, V.; Penalba, A.; Ramiro, L.; Simats, A.; Bustamante, A.; Martinez-Saez, E.; et al. Single Cell Immuno-Laser Microdissection Coupled to Label-Free Proteomics to Reveal the Proteotypes of Human Brain Cells After Ischemia. Mol Cell Proteomics 2018, 17, 175-189. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Bogdanovic, N.; Nakagawa, H.; Volkmann, I.; Aoki, M.; Winblad, B.; Sakai, J.; Tjernberg, L.O. Analysis of microdissected neurons by 18O mass spectrometry reveals altered protein expression in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2012, 16, 1686-1700. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, M.L.; Favo, D.; Garver, M.; Sun, Z.; Arion, D.; Ding, Y.; Yates, N.; Sweet, R.A.; Lewis, D.A. Laser capture microdissection–targeted mass spectrometry: a method for multiplexed protein quantification within individual layers of the cerebral cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 743-748. [CrossRef]

- Griesser, E.; Wyatt, H.; Ten Have, S.; Stierstorfer, B.; Lenter, M.; Lamond, A.I. Quantitative Profiling of the Human Substantia Nigra Proteome from Laser-capture Microdissected FFPE Tissue*. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2020, 19, 839-851. [CrossRef]

- do Canto, A.M.; Vieira, A.S.; A, H.B.M.; Carvalho, B.S.; Henning, B.; Norwood, B.A.; Bauer, S.; Rosenow, F.; Gilioli, R.; Cendes, F.; et al. Laser microdissection-based microproteomics of the hippocampus of a rat epilepsy model reveals regional differences in protein abundances. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 4412. [CrossRef]

- Bensaddek, D.; Narayan, V.; Nicolas, A.; Brenes Murillo, A.; Gartner, A.; Kenyon, C.J.; Lamond, A.I. Micro-proteomics with iterative data analysis: Proteome analysis in C. elegans at the single worm level. PROTEOMICS 2016, 16, 381-392. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.P.; Ludhiadch, A.; Munshi, A. Chapter 9 - Single-Cell Genomics: Technology and Applications. In Single-Cell Omics, Barh, D., Azevedo, V., Eds.; Academic Press: 2019; pp. 179-197.

- Holt, L.M.; Olsen, M.L. Novel Applications of Magnetic Cell Sorting to Analyze Cell-Type Specific Gene and Protein Expression in the Central Nervous System. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0150290. [CrossRef]

- Rayaprolu, S.; Gao, T.; Xiao, H.; Ramesha, S.; Weinstock, L.D.; Shah, J.; Duong, D.M.; Dammer, E.B.; Webster, J.A., Jr.; Lah, J.J.; et al. Flow-cytometric microglial sorting coupled with quantitative proteomics identifies moesin as a highly-abundant microglial protein with relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener 2020, 15, 28. [CrossRef]

- Jungblut, M.; Tiveron, M.C.; Barral, S.; Abrahamsen, B.; Knöbel, S.; Pennartz, S.; Schmitz, J.; Perraut, M.; Pfrieger, F.W.; Stoffel, W.; et al. Isolation and characterization of living primary astroglial cells using the new GLAST-specific monoclonal antibody ACSA-1. Glia 2012, 60, 894-907. [CrossRef]

- Stokum, J.A.; Shim, B.; Huang, W.; Kane, M.; Smith, J.A.; Gerzanich, V.; Simard, J.M. A large portion of the astrocyte proteome is dedicated to perivascular endfeet, including critical components of the electron transport chain. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2021, 41, 2546-2560. [CrossRef]

- Rangaraju, S.; Dammer, E.B.; Raza, S.A.; Gao, T.; Xiao, H.; Betarbet, R.; Duong, D.M.; Webster, J.A.; Hales, C.M.; Lah, J.J.; et al. Quantitative proteomics of acutely-isolated mouse microglia identifies novel immune Alzheimer’s disease-related proteins. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2018, 13, 34. [CrossRef]

- Maes, E.; Cools, N.; Willems, H.; Baggerman, G. FACS-Based Proteomics Enables Profiling of Proteins in Rare Cell Populations. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.; Schoendube, J.; Zimmermann, S.; Steeb, M.; Zengerle, R.; Koltay, P. Technologies for Single-Cell Isolation. Int J Mol Sci 2015, 16, 16897-16919. [CrossRef]

- Postupna, N.O.; Latimer, C.S.; Keene, C.D.; Montine, K.S.; Montine, T.J.; Darvas, M. Flow cytometric evaluation of crude synaptosome preparation as a way to study synaptic alteration in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuromethods 2018, 141, 297-310. [CrossRef]

- Biesemann, C.; Gronborg, M.; Luquet, E.; Wichert, S.P.; Bernard, V.; Bungers, S.R.; Cooper, B.; Varoqueaux, F.; Li, L.; Byrne, J.A.; et al. Proteomic screening of glutamatergic mouse brain synaptosomes isolated by fluorescence activated sorting. EMBO J 2014, 33, 157-170. [CrossRef]

- Husi, H.; Ward, M.A.; Choudhary, J.S.; Blackstock, W.P.; Grant, S.G.N. Proteomic analysis of NMDA receptor–adhesion protein signaling complexes. Nature Neuroscience 2000, 3, 661-669. [CrossRef]

- Dosemeci, A.; Makusky, A.J.; Jankowska-Stephens, E.; Yang, X.; Slotta, D.J.; Markey, S.P. Composition of the synaptic PSD-95 complex. Mol Cell Proteomics 2007, 6, 1749-1760. [CrossRef]

- Klemmer, P.; Smit, A.B.; Li, K.W. Proteomics analysis of immuno-precipitated synaptic protein complexes. Journal of Proteomics 2009, 72, 82-90. [CrossRef]

- Paulo, J.A.; Brucker, W.J.; Hawrot, E. Proteomic Analysis of an α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Interactome. Journal of Proteome Research 2009, 8, 1849-1858. [CrossRef]

- Farr, C.D.; Gafken, P.R.; Norbeck, A.D.; Doneanu, C.E.; Stapels, M.D.; Barofsky, D.F.; Minami, M.; Saugstad, J.A. Proteomic analysis of native metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 protein complexes reveals novel molecular constituents. Journal of Neurochemistry 2004, 91, 438-450. [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.O.; Husi, H.; Yu, L.; Brandon, J.M.; Anderson, C.N.G.; Blackstock, W.P.; Choudhary, J.S.; Grant, S.G.N. Molecular characterization and comparison of the components and multiprotein complexes in the postsynaptic proteome. Journal of Neurochemistry 2006, 97, 16-23. [CrossRef]

- Rigaut, G.; Shevchenko, A.; Rutz, B.; Wilm, M.; Mann, M.; Séraphin, B. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nature Biotechnology 1999, 17, 1030-1032. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. The tandem affinity purification technology: an overview. Biotechnol Lett 2011, 33, 1487-1499. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, E.; Collins, M.O.; Uren, R.T.; Kopanitsa, M.V.; Komiyama, N.H.; Croning, M.D.; Zografos, L.; Armstrong, J.D.; Choudhary, J.S.; Grant, S.G. Targeted tandem affinity purification of PSD-95 recovers core postsynaptic complexes and schizophrenia susceptibility proteins. Mol Syst Biol 2009, 5, 269. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Collins, M.O.; Harmse, J.; Choudhary, J.S.; Grant, S.G.N.; Komiyama, N.H. Cell-type-specific visualisation and biochemical isolation of endogenous synaptic proteins in mice. Eur J Neurosci 2020, 51, 793-805. [CrossRef]

- Stone, S.E.; Glenn, W.S.; Hamblin, G.D.; Tirrell, D.A. Cell-selective proteomics for biological discovery. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2017, 36, 50-57. [CrossRef]

- Fingleton, E.; Li, Y.; Roche, K.W. Advances in Proteomics Allow Insights Into Neuronal Proteomes. Front Mol Neurosci 2021, 14, 647451. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Castelao, B.; Schanzenbacher, C.T.; Hanus, C.; Glock, C.; Tom Dieck, S.; Dorrbaum, A.R.; Bartnik, I.; Nassim-Assir, B.; Ciirdaeva, E.; Mueller, A.; et al. Cell-type-specific metabolic labeling of nascent proteomes in vivo. Nat Biotechnol 2017, 35, 1196-1201. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Castelao, B.; Schanzenbacher, C.T.; Langer, J.D.; Schuman, E.M. Cell-type-specific metabolic labeling, detection and identification of nascent proteomes in vivo. Nat Protoc 2019, 14, 556-575. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, B.; Bathla, S.; Williams, K.R.; Nairn, A.C. Deciphering Spatial Protein-Protein Interactions in Brain Using Proximity Labeling. Mol Cell Proteomics 2022, 21, 100422. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.I.; Jensen, S.C.; Noble, K.A.; Kc, B.; Roux, K.H.; Motamedchaboki, K.; Roux, K.J. An improved smaller biotin ligase for BioID proximity labeling. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2016, 27, 1188-1196. [CrossRef]

- Branon, T.C.; Bosch, J.A.; Sanchez, A.D.; Udeshi, N.D.; Svinkina, T.; Carr, S.A.; Feldman, J.L.; Perrimon, N.; Ting, A.Y. Efficient proximity labeling in living cells and organisms with TurboID. Nature Biotechnology 2018, 36, 880-887. [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.S.; Martell, J.D.; Kamer, K.J.; Deerinck, T.J.; Ellisman, M.H.; Mootha, V.K.; Ting, A.Y. Directed evolution of APEX2 for electron microscopy and proximity labeling. Nature Methods 2015, 12, 51-54. [CrossRef]

- Cijsouw, T.; Ramsey, A.M.; Lam, T.T.; Carbone, B.E.; Blanpied, T.A.; Biederer, T. Mapping the Proteome of the Synaptic Cleft through Proximity Labeling Reveals New Cleft Proteins. Proteomes 2018, 6. [CrossRef]

- Shuster, S.A.; Li, J.; Chon, U.; Sinantha-Hu, M.C.; Luginbuhl, D.J.; Udeshi, N.D.; Carey, D.K.; Takeo, Y.H.; Xie, Q.; Xu, C.; et al. In situ cell-type-specific cell-surface proteomic profiling in mice. Neuron 2022, 110, 3882-3896 e3889. [CrossRef]

- Dumrongprechachan, V.; Salisbury, R.B.; Soto, G.; Kumar, M.; MacDonald, M.L.; Kozorovitskiy, Y. Cell-type and subcellular compartment-specific APEX2 proximity labeling reveals activity-dependent nuclear proteome dynamics in the striatum. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 4855. [CrossRef]

- Brewer, K.D.; Shi, S.M.; Wyss-Coray, T. Unraveling protein dynamics to understand the brain - the next molecular frontier. Mol Neurodegener 2022, 17, 45. [CrossRef]

- Uezu, A.; Kanak, D.J.; Bradshaw, T.W.A.; Soderblom, E.J.; Catavero, C.M.; Burette, A.C.; Weinberg, R.J.; Soderling, S.H. Identification of an elaborate complex mediating postsynaptic inhibition. Science 2016, 353, 1123-1129. [CrossRef]

- Spence, E.F.; Dube, S.; Uezu, A.; Locke, M.; Soderblom, E.J.; Soderling, S.H. In vivo proximity proteomics of nascent synapses reveals a novel regulator of cytoskeleton-mediated synaptic maturation. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 386. [CrossRef]

- Rayaprolu, S.; Bitarafan, S.; Santiago, J.V.; Betarbet, R.; Sunna, S.; Cheng, L.; Xiao, H.; Nelson, R.S.; Kumar, P.; Bagchi, P.; et al. Cell type-specific biotin labeling in vivo resolves regional neuronal and astrocyte proteomic differences in mouse brain. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 2927. [CrossRef]

- Takano, T.; Wallace, J.T.; Baldwin, K.T.; Purkey, A.M.; Uezu, A.; Courtland, J.L.; Soderblom, E.J.; Shimogori, T.; Maness, P.F.; Eroglu, C.; et al. Chemico-genetic discovery of astrocytic control of inhibition in vivo. Nature 2020, 588, 296-302. [CrossRef]

- Hobson, B.D.; Choi, S.J.; Mosharov, E.V.; Soni, R.K.; Sulzer, D.; Sims, P.A. Subcellular proteomics of dopamine neurons in the mouse brain. Elife 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.M.T.; Kim, J.; Doan, T.T.; Lee, M.-W.; Lee, M. APEX Proximity Labeling as a Versatile Tool for Biological Research. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 260-269. [CrossRef]

- Dupree, E.J.; Jayathirtha, M.; Yorkey, H.; Mihasan, M.; Petre, B.A.; Darie, C.C. A Critical Review of Bottom-Up Proteomics: The Good, the Bad, and the Future of this Field. Proteomes 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fonslow, B.R.; Shan, B.; Baek, M.C.; Yates, J.R., 3rd. Protein analysis by shotgun/bottom-up proteomics. Chem Rev 2013, 113, 2343-2394. [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.M.; Kelleher, N.L.; Linial, M.; Goodlett, D.; Langridge-Smith, P.; Ah Goo, Y.; Safford, G.; Bonilla*, L.; Kruppa, G.; Zubarev, R.; et al. Proteoform: a single term describing protein complexity. Nature Methods 2013, 10, 186-187. [CrossRef]

- Catherman, A.D.; Skinner, O.S.; Kelleher, N.L. Top Down proteomics: facts and perspectives. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014, 445, 683-693. [CrossRef]

- Melby, J.A.; Roberts, D.S.; Larson, E.J.; Brown, K.A.; Bayne, E.F.; Jin, S.; Ge, Y. Novel Strategies to Address the Challenges in Top-Down Proteomics. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2021, 32, 1278-1294. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Nairn, A.C. Cell-Type-Specific Proteomics: A Neuroscience Perspective. Proteomes 2018, 6. [CrossRef]

- Giesen, C.; Wang, H.A.O.; Schapiro, D.; Zivanovic, N.; Jacobs, A.; Hattendorf, B.; Schüffler, P.J.; Grolimund, D.; Buhmann, J.M.; Brandt, S.; et al. Highly multiplexed imaging of tumor tissues with subcellular resolution by mass cytometry. Nature Methods 2014, 11, 417-422. [CrossRef]

- Amy, L.V.D.; Sarah, M.G.; Corey, M.W.; Austin, B.K.; Kristen, I.F.; Irene, C.; Christopher, D.D.; Eli, R.Z. A developmental atlas of the mouse brain by single-cell mass cytometry. bioRxiv 2022, 2022.2007.2027.501794. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gaiteri, C.; Bodea, L.G.; Wang, Z.; McElwee, J.; Podtelezhnikov, A.A.; Zhang, C.; Xie, T.; Tran, L.; Dobrin, R.; et al. Integrated systems approach identifies genetic nodes and networks in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Cell 2013, 153, 707-720. [CrossRef]

- Vogel, C.; Marcotte, E.M. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nature Reviews Genetics 2012, 13, 227-232. [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Abreu, R.; Penalva, L.O.; Marcotte, E.M.; Vogel, C. Global signatures of protein and mRNA expression levels. Molecular BioSystems 2009, 5, 1512-1526. [CrossRef]

- Mansuri, M.S.; Williams, K.; Nairn, A.C. Uncovering biology by single-cell proteomics. Commun Biol 2023, 6, 381. [CrossRef]

- Budnik, B.; Levy, E.; Harmange, G.; Slavov, N. SCoPE-MS: mass spectrometry of single mammalian cells quantifies proteome heterogeneity during cell differentiation. Genome Biol 2018, 19, 161. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.F.; Zhao, R.; Williams, S.M.; Moore, R.J.; Schultz, K.; Chrisler, W.B.; Pasa-Tolic, L.; Rodland, K.D.; Smith, R.D.; Shi, T.; et al. An Improved Boosting to Amplify Signal with Isobaric Labeling (iBASIL) Strategy for Precise Quantitative Single-cell Proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 2020, 19, 828-838. [CrossRef]

- Goto-Silva, L.; Junqueira, M. Single-cell proteomics: A treasure trove in neurobiology. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 2021, 1869, 140658. [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Bai, Z.; Song, F.; Lei, H. Genomics in neurological disorders. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2014, 12, 156-163. [CrossRef]

- Reim, D.; Distler, U.; Halbedl, S.; Verpelli, C.; Sala, C.; Bockmann, J.; Tenzer, S.; Boeckers, T.M.; Schmeisser, M.J. Proteomic Analysis of Post-synaptic Density Fractions from Shank3 Mutant Mice Reveals Brain Region Specific Changes Relevant to Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Mol Neurosci 2017, 10, 26. [CrossRef]

- Al Shweiki, M.R.; Oeckl, P.; Steinacker, P.; Barschke, P.; Dorner-Ciossek, C.; Hengerer, B.; Schonfeldt-Lecuona, C.; Otto, M. Proteomic analysis reveals a biosignature of decreased synaptic protein in cerebrospinal fluid of major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry 2020, 10, 144. [CrossRef]

- Pennington, K.; Beasley, C.L.; Dicker, P.; Fagan, A.; English, J.; Pariante, C.M.; Wait, R.; Dunn, M.J.; Cotter, D.R. Prominent synaptic and metabolic abnormalities revealed by proteomic analysis of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2008, 13, 1102-1117. [CrossRef]

- Mullin, A.P.; Gokhale, A.; Moreno-De-Luca, A.; Sanyal, S.; Waddington, J.L.; Faundez, V. Neurodevelopmental disorders: mechanisms and boundary definitions from genomes, interactomes and proteomes. Transl Psychiatry 2013, 3, e329. [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Elsabbagh, M.; Baird, G.; Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet 2018, 392, 508-520. [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Wang, T.; Wan, H.; Han, L.; Qin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, C.; Berton, F.; Francesconi, W.; et al. Fmr1 deficiency promotes age-dependent alterations in the cortical synaptic proteome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, E4697-4706. [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.J.; Paranjape, S.R.; Walker, M.P.; Choudhury, R.; Wolter, J.M.; Fragola, G.; Emanuele, M.J.; Major, M.B.; Zylka, M.J. The autism-linked UBE3A T485A mutant E3 ubiquitin ligase activates the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway by inhibiting the proteasome. J Biol Chem 2017, 292, 12503-12515. [CrossRef]

- Matic, K.; Eninger, T.; Bardoni, B.; Davidovic, L.; Macek, B. Quantitative phosphoproteomics of murine Fmr1-KO cell lines provides new insights into FMRP-dependent signal transduction mechanisms. J Proteome Res 2014, 13, 4388-4397. [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.O.; Yu, L.; Coba, M.P.; Husi, H.; Campuzano, I.; Blackstock, W.P.; Choudhary, J.S.; Grant, S.G. Proteomic analysis of in vivo phosphorylated synaptic proteins. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 5972-5982. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wilkinson, B.; Clementel, V.A.; Hou, J.; O’Dell, T.J.; Coba, M.P. Long-term potentiation modulates synaptic phosphorylation networks and reshapes the structure of the postsynaptic interactome. Sci Signal 2016, 9, rs8. [CrossRef]

- Amal, H.; Barak, B.; Bhat, V.; Gong, G.; Joughin, B.A.; Wang, X.; Wishnok, J.S.; Feng, G.; Tannenbaum, S.R. Shank3 mutation in a mouse model of autism leads to changes in the S-nitroso-proteome and affects key proteins involved in vesicle release and synaptic function. Mol Psychiatry 2020, 25, 1835-1848. [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, N.; Cheng, A.A.; Brown, C.O.; Meka, D.P.; Hong, S.; Uy, J.A.; El-Hajjar, J.; Pipko, N.; Unda, B.K.; Schwanke, B.; et al. Neuron-specific protein network mapping of autism risk genes identifies shared biological mechanisms and disease-relevant pathologies. Cell Rep 2022, 41, 111678. [CrossRef]

- Tilot, A.K.; Bebek, G.; Niazi, F.; Altemus, J.B.; Romigh, T.; Frazier, T.W.; Eng, C. Neural transcriptome of constitutional Pten dysfunction in mice and its relevance to human idiopathic autism spectrum disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2016, 21, 118-125. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, Y.W.; Xu, H. Proteolytic processing of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid precursor protein. J Neurochem 2012, 120 Suppl 1, 9-21. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, K.; Lee, Y.C.; Kim, S.; Won, H.H.; Yu, T.Y.; Lee, E.M.; Kang, J.M.; Lewis, M.; Kim, D.K.; et al. Associations between vascular risk factors and subsequent Alzheimer’s disease in older adults. Alzheimers Res Ther 2020, 12, 117. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, G.M.; Li, S.; Mehta, T.H.; Garcia-Munoz, A.; Shepardson, N.E.; Smith, I.; Brett, F.M.; Farrell, M.A.; Rowan, M.J.; Lemere, C.A.; et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med 2008, 14, 837-842. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.P.; Barlow, A.K.; Chromy, B.A.; Edwards, C.; Freed, R.; Liosatos, M.; Morgan, T.E.; Rozovsky, I.; Trommer, B.; Viola, K.L.; et al. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95, 6448-6453. [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.Y.; Nouwens, A.S.; Dodd, P.R.; Etheridge, N. The synaptic proteome in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2013, 9, 499-511. [CrossRef]

- Hesse, R.; Hurtado, M.L.; Jackson, R.J.; Eaton, S.L.; Herrmann, A.G.; Colom-Cadena, M.; Tzioras, M.; King, D.; Rose, J.; Tulloch, J.; et al. Comparative profiling of the synaptic proteome from Alzheimer’s disease patients with focus on the APOE genotype. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2019, 7, 214. [CrossRef]

- Kadoyama, K.; Matsuura, K.; Takano, M.; Otani, M.; Tomiyama, T.; Mori, H.; Matsuyama, S. Proteomic analysis involved with synaptic plasticity improvement by GABA(A) receptor blockade in hippocampus of a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Res 2021, 165, 61-68. [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.R.; Cherian, J.; Gohil, K.; Atkinson, D. Schizophrenia: overview and treatment options. P T 2014, 39, 638-645.

- Luvsannyam, E.; Jain, M.S.; Pormento, M.K.L.; Siddiqui, H.; Balagtas, A.R.A.; Emuze, B.O.; Poprawski, T. Neurobiology of Schizophrenia: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e23959. [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.J.; Sawa, A.; Mortensen, P.B. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2016, 388, 86-97. [CrossRef]

- Brisch, R.; Saniotis, A.; Wolf, R.; Bielau, H.; Bernstein, H.G.; Steiner, J.; Bogerts, B.; Braun, K.; Jankowski, Z.; Kumaratilake, J.; et al. The role of dopamine in schizophrenia from a neurobiological and evolutionary perspective: old fashioned, but still in vogue. Front Psychiatry 2014, 5, 47. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.J.; Weinberger, D.R. Schizophrenia genes, gene expression, and neuropathology: on the matter of their convergence. Mol Psychiatry 2005, 10, 40-68; image 45. [CrossRef]

- Osimo, E.F.; Beck, K.; Reis Marques, T.; Howes, O.D. Synaptic loss in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and systematic review of synaptic protein and mRNA measures. Mol Psychiatry 2019, 24, 549-561. [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, R.; Weinberger, D.R. Genetic insights into the neurodevelopmental origins of schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017, 18, 727-740. [CrossRef]

- Rosato, M.; Stringer, S.; Gebuis, T.; Paliukhovich, I.; Li, K.W.; Posthuma, D.; Sullivan, P.F.; Smit, A.B.; van Kesteren, R.E. Combined cellomics and proteomics analysis reveals shared neuronal morphology and molecular pathway phenotypes for multiple schizophrenia risk genes. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 784-799. [CrossRef]

- Focking, M.; Lopez, L.M.; English, J.A.; Dicker, P.; Wolff, A.; Brindley, E.; Wynne, K.; Cagney, G.; Cotter, D.R. Proteomic and genomic evidence implicates the postsynaptic density in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2015, 20, 424-432. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, H.; Howrigan, D.P.; Wilkinson, B.; Souaiaia, T.; Evgrafov, O.V.; Genovese, G.; Clementel, V.A.; Tudor, J.C.; et al. Spatiotemporal profile of postsynaptic interactomes integrates components of complex brain disorders. Nat Neurosci 2017, 20, 1150-1161. [CrossRef]

- Administration., S.A.a.M.H.S. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56). 2021.

- Martins-de-Souza, D. Comprehending depression through proteomics. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2012, 15, 1373-1374. [CrossRef]

- Beasley, C.L.; Pennington, K.; Behan, A.; Wait, R.; Dunn, M.J.; Cotter, D. Proteomic analysis of the anterior cingulate cortex in the major psychiatric disorders: Evidence for disease-associated changes. Proteomics 2006, 6, 3414-3425. [CrossRef]

- Johnston-Wilson, N.L.; Sims, C.D.; Hofmann, J.P.; Anderson, L.; Shore, A.D.; Torrey, E.F.; Yolken, R.H. Disease-specific alterations in frontal cortex brain proteins in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. The Stanley Neuropathology Consortium. Mol Psychiatry 2000, 5, 142-149. [CrossRef]

- Martins-de-Souza, D.; Guest, P.C.; Harris, L.W.; Vanattou-Saifoudine, N.; Webster, M.J.; Rahmoune, H.; Bahn, S. Identification of proteomic signatures associated with depression and psychotic depression in post-mortem brains from major depression patients. Transl Psychiatry 2012, 2, e87. [CrossRef]

- Martins-de-Souza, D.; Guest, P.C.; Vanattou-Saifoudine, N.; Rahmoune, H.; Bahn, S. Phosphoproteomic differences in major depressive disorder postmortem brains indicate effects on synaptic function. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2012, 262, 657-666. [CrossRef]

- Ditzen, C.; Tang, N.; Jastorff, A.M.; Teplytska, L.; Yassouridis, A.; Maccarrone, G.; Uhr, M.; Bronisch, T.; Miller, C.A.; Holsboer, F.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for major depression confirm relevance of associated pathophysiology. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 1013-1025. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.B.; Zhang, R.F.; Luo, D.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fang, L.; Li, W.J.; Mu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of plasma from major depressive patients: identification of proteins associated with lipid metabolism and immunoregulation. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2012, 15, 1413-1425. [CrossRef]

- See, R.E. Neural substrates of conditioned-cued relapse to drug-seeking behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2002, 71, 517-529. [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B.J.; Wolf, M.E. Psychomotor stimulant addiction: a neural systems perspective. J Neurosci 2002, 22, 3312-3320, doi:20026356.

- Jasinska, A.J.; Chen, B.T.; Bonci, A.; Stein, E.A. Dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) circuitry in rodent models of cocaine use: implications for drug addiction therapies. Addict Biol 2015, 20, 215-226. [CrossRef]

- Van den Oever, M.C.; Spijker, S.; Smit, A.B.; De Vries, T.J. Prefrontal cortex plasticity mechanisms in drug seeking and relapse. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010, 35, 276-284. [CrossRef]

- Bosch, P.J.; Peng, L.; Kivell, B.M. Proteomics Analysis of Dorsal Striatum Reveals Changes in Synaptosomal Proteins following Methamphetamine Self-Administration in Rats. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0139829. [CrossRef]

- Lull, M.E.; Erwin, M.S.; Morgan, D.; Roberts, D.C.; Vrana, K.E.; Freeman, W.M. Persistent proteomic alterations in the medial prefrontal cortex with abstinence from cocaine self-administration. Proteomics Clin Appl 2009, 3, 462-472. [CrossRef]

- Puig, S.; Xue, X.; Salisbury, R.; Shelton, M.A.; Kim, S.M.; Hildebrand, M.A.; Glausier, J.R.; Freyberg, Z.; Tseng, G.C.; Yocum, A.K.; et al. Uncovering circadian rhythm disruptions of synaptic proteome signaling in prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens associated with opioid use disorder. bioRxiv 2023. [CrossRef]

- Scofield, M.D.; Heinsbroek, J.A.; Gipson, C.D.; Kupchik, Y.M.; Spencer, S.; Smith, A.C.; Roberts-Wolfe, D.; Kalivas, P.W. The Nucleus Accumbens: Mechanisms of Addiction across Drug Classes Reflect the Importance of Glutamate Homeostasis. Pharmacol Rev 2016, 68, 816-871. [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F.; Volkow, N.D. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 760-773. [CrossRef]

- Lobo, M.K.; Covington, H.E., 3rd; Chaudhury, D.; Friedman, A.K.; Sun, H.; Damez-Werno, D.; Dietz, D.M.; Zaman, S.; Koo, J.W.; Kennedy, P.J.; et al. Cell type-specific loss of BDNF signaling mimics optogenetic control of cocaine reward. Science 2010, 330, 385-390. [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, A.V.; Tye, L.D.; Kreitzer, A.C. Distinct roles for direct and indirect pathway striatal neurons in reinforcement. Nat Neurosci 2012, 15, 816-818. [CrossRef]

- Calipari, E.S.; Bagot, R.C.; Purushothaman, I.; Davidson, T.J.; Yorgason, J.T.; Pena, C.J.; Walker, D.M.; Pirpinias, S.T.; Guise, K.G.; Ramakrishnan, C.; et al. In vivo imaging identifies temporal signature of D1 and D2 medium spiny neurons in cocaine reward. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 2726-2731. [CrossRef]

- Lutz, P.E.; Kieffer, B.L. The multiple facets of opioid receptor function: implications for addiction. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2013, 23, 473-479. [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.D.; Kashima, D.T.; Manz, K.M.; Grueter, C.A.; Grueter, B.A. Synaptic Plasticity in the Nucleus Accumbens: Lessons Learned from Experience. ACS Chem Neurosci 2018, 9, 2114-2126. [CrossRef]

- Chartoff, E.H.; Connery, H.S. It’s MORe exciting than mu: crosstalk between mu opioid receptors and glutamatergic transmission in the mesolimbic dopamine system. Front Pharmacol 2014, 5, 116. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Cizeron, M.; Qiu, Z.; Benavides-Piccione, R.; Kopanitsa, M.V.; Skene, N.G.; Koniaris, B.; DeFelipe, J.; Fransen, E.; Komiyama, N.H.; et al. Architecture of the Mouse Brain Synaptome. Neuron 2018, 99, 781-799 e710. [CrossRef]

- Curran, O.E.; Qiu, Z.; Smith, C.; Grant, S.G.N. A single-synapse resolution survey of PSD95-positive synapses in twenty human brain regions. Eur J Neurosci 2021, 54, 6864-6881. [CrossRef]

- Cizeron, M.; Qiu, Z.; Koniaris, B.; Gokhale, R.; Komiyama, N.H.; Fransen, E.; Grant, S.G.N. A brainwide atlas of synapses across the mouse life span. Science 2020, 369, 270-275. [CrossRef]

- Minehart, J.A.; Speer, C.M. A Picture Worth a Thousand Molecules-Integrative Technologies for Mapping Subcellular Molecular Organization and Plasticity in Developing Circuits. Front Synaptic Neurosci 2020, 12, 615059. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).