Submitted:

18 May 2023

Posted:

18 May 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Bilingualism and the attentional network

1.2. Attentional Network and socioeconomic status

1.3. The study’s aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Participants’ Sociocultural and Language Characteristics

2.3.1. Assessment of IQ

2.3.2. Assessment of language abilities

2.3.3. Assessment of Working memory

2.3.4. Assessment of attentional networks

2.4. Procedure

2.4.1. Parent’s Questionnaire

- general information about the child and his family;

- employment of parents and educational qualification;

- country of origin of parents and years of stay in Italy;

- languages are spoken at home;

- frequency of activities carried out with his/her child;

- linguistic competence in L1 and L2 (part reserved for parents with languages other than Italian).

2.4.2. Computation of attentional networks

3. Results

3.1. The linguistic and the sociocultural status

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Abutalebi, J.; Della Rosa, P.A.; Green, D.W.; Hernandez, M.; Scifo, P.; Keim, R.; Cappa, S.F.; Costa, A. Bilingualism Tunes the Anterior Cingulate Cortex for Conflict Monitoring. Cereb. Cortex 2011, 22, 2076–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antón, E.; Duñabeitia, J.A.; Estévez, A.; Hernández, J.A.; Castillo, A.; Fuentes, L.J.; Davidson, D.J.; Carreiras, M. Is there a bilingual advantage in the ANT task? Evidence from children. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barkley, R.A.; Fischer, M. Predicting Impairment in Major Life Activities and Occupational Functioning in Hyperactive Children as Adults: Self-Reported Executive Function (EF) Deficits Versus EF Tests. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2011, 36, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertelli, B. & Bilancia, G.(2006). Batterie per la Valutazione dell’Attenzione Uditiva e della Memoria di Lavoro Fonologica nell’Età Evolutiva (VAUMeLF).

- Bialystok, E. Reshaping the mind: The benefits of bilingualism. Can J Exp Psychol. 2011, 65, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blom, E.; Küntay, A.C.; Messer, M.; Verhagen, J.; Leseman, P. The benefits of being bilingual: Working memory in bilingual Turkish–Dutch children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2014, 128, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buac, M.; Gross, M.; Kaushanskaya, M. Predictors of processing-based task performance in bilingual and monolingual children. J. Commun. Disord. 2016, 62, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckner, J.C.; Mezzacappa, E.; Beardslee, W.R. Characteristics of resilient youths living in poverty: The role of self-regulatory processes. Dev. Psychopathol. 2003, 15, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabria, M.; Branzi, F.M.; Marne, P.; Hernández, M.; Costa, A. Age-related effects over bilingual language control and executive control. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2013, 18, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, S.M.; Meltzoff, A.N. Bilingual experience and executive functioning in young children. Dev. Sci. 2008, 11, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, C.; Boiché, J.; Armandon, P.; Baudoin, S.; Bellocchi, S. Is bilingualism associated with better working memory capacity? A meta-analysis. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2021, 25, 2229–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Cohen, S.; Miller, G.E. How Low Socioeconomic Status Affects 2-Year Hormonal Trajectories in Children. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 21, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conejero. ; Rueda, M.R. Infant temperament and family socio-economic status in relation to the emergence of attention regulation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Hernández, M.; Sebastián-Gallés, N. Bilingualism aids conflict resolution: Evidence from the ANT task. Cognition 2008, 106, 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, S.; Shakyawar, S.K.; Sharma, M.; Kaushik, S. Big data in healthcare: management, analysis and future prospects. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.L.; Matthews, R.N. NEPSY-II Review. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2010, 28, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, C.D.; Wadsworth, M.E.; Stump, J. Socioeconomic status, neighborhood disadvantage, and poverty-related stress: Prospective effects on psychological syndromes among diverse low-income families. J. Econ. Psychol. 2011, 32, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Costa, H.; Tabiasco, J.; Berrebi, A.; Parant, O.; Aguerre-Girr, M.; Piccinni, M.-P.; Le Bouteiller, P. Effector functions of human decidual NK cells in healthy early pregnancy are dependent on the specific engagement of natural cytotoxicity receptors. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2009, 82, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. (2007). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test--Fourth Edition (PPVT-4) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. [CrossRef]

- Engle, R.W. Working Memory Capacity as Executive Attention. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2002, 11, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Heron, J.; Lewis, G.; Araya, R.; Wolke, D. Negative self-schemas and the onset of depression in women: longitudinal study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2005, 186, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; McCandliss, B.D.; Sommer, T.; Raz, A.; Posner, M.I. Testing the Efficiency and Independence of Attentional Networks. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2002, 14, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Ovtchinnikov, M.; Comstock, J.M.; McFarlane, S.A.; Khain, A. Ice formation in Arctic mixed-phase clouds: Insights from a 3-D cloud-resolving model with size-resolved aerosol and cloud microphysics. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, F.; Marotta, A.; Martella, D.; Casagrande, M. Development in attention functions and social processing: Evidence from the Attention Network Test. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 35, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossum, I.N.; Andersen, P.N.; Øie, M.G.; Skogli, E.W. Development of executive functioning from childhood to young adulthood in autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A 10-year longitudinal study. Neuropsychology 2021, 35, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federico, F.; Marotta, A.; Adriani, T.; Maccari, L.; Casagrande, M. Attention network test — The impact of social information on executive control, alerting and orienting. Acta Psychol. 2013, 143, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federico, F.; Marotta, A.; Orsolini, M.; Casagrande, M. Aging in cognitive control of social processing: evidence from the attention network test. Aging, Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2020, 28, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, S.F.; Morton, J.B. Time to disengage from the bilingual advantage hypothesis. Cognition 2018, 170, 328–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, S.F.; Morton, J.B. Sequential Congruency Effects in Monolingual and Bilingual Adults: A Failure to Replicate Grundy et al. (2017). Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.T.; Hinshaw, S.P. Executive Functions in Girls With and Without Childhood ADHD Followed Through Emerging Adulthood: Developmental Trajectories. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019, 49, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.W. Mental control of the bilingual lexico-semantic system. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 1998, 1, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, J.G.; Timmer, K. Bilingualism and working memory capacity: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Second. Lang. Res. 2016, 33, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, J.G.; Chung-Fat-Yim, A.; Friesen, D.C.; Mak, L.; Bialystok, E. Sequential congruency effects reveal differences in disengagement of attention for monolingual and bilingual young adults. Cognition 2017, 163, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullifer, J.W.; Chai, X.J.; Whitford, V.; Pivneva, I.; Baum, S.; Klein, D.; Titone, D. Bilingual experience and resting-state brain connectivity: Impacts of L2 age of acquisition and social diversity of language use on control networks. Neuropsychologia 2018, 117, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernàndez, M.; Caño, A.; Costa, A.; Sebastiangalles, N.; Juncadella, M.; Gasconbayarri, J. Grammatical category-specific deficits in bilingual aphasia. Brain Lang. 2008, 107, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, M.J.; Brown, L.H.; McVay, J.C.; Silvia, P.J.; Myin-Germeys, I.; Kwapil, T.R. For Whom the Mind Wanders, and When. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kray, J.; Kipp, K.H.; Karbach, J. The development of selective inhibitory control: The influence of verbal labeling. Acta Psychol. 2009, 130, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroll, J.F.; Bialystok, E. Understanding the consequences of bilingualism for language processing and cognition. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2013, 25, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladas, A.I.; Carroll, D.J.; Vivas, A.B. Attentional Processes in Low-Socioeconomic Status Bilingual Children: Are They Modulated by the Amount of Bilingual Experience? Child Dev. 2015, 86, 557–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, M.; Soveri, A.; Laine, A.; Järvenpää, J.; de Bruin, A.; Antfolk, J. Is bilingualism associated with enhanced executive functioning in adults? A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 394–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.L. Rosen, M.P. Hagen, Lucy Lurie, Miles A, E. Zoe, Margaret A. Sheridan, Andrew N. Meltzoff, K.A. McLaughlin Cognitive stimulation as a mechanism linking socioeconomic status with executive function: a longitudinal investigation of the gap in academic achievement, Child Dev. (2019).

- Rueda, M.; Fan, J.; McCandliss, B.D.; Halparin, J.D.; Gruber, D.B.; Lercari, L.P.; I Posner, M. Development of attentional networks in childhood. Neuropsychologia 2004, 42, 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mance, G.A.; Grant, K.E.; Roberts, D.; Carter, J.; Turek, C.; Adam, E.; Thorpe, R.J. Environmental stress and socioeconomic status: Does parent and adolescent stress influence executive functioning in urban youth? J. Prev. Interv. Community 2019, 47, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, M.C.; Marx, C. Inhibitory processes in visual perception: A bilingual advantage. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2014, 126, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martella, D.; Casagrande, M.; Lupiáñez, J. Alerting, orienting and executive control: the effects of sleep deprivation on attentional networks. Exp. Brain Res. 2011, 210, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechelli, A.; Crinion, J.T.; Noppeney, U.; O’Doherty, J.; Ashburner, J.; Frackowiak, R.S.; Price, C.J. Structural plasticity in the bilingual brain. Nature 2004, 431, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezzacappa, E. Alerting, Orienting, and Executive Attention: Developmental Properties and Sociodemographic Correlates in an Epidemiological Sample of Young, Urban Children. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, J.B.; Harper, S.N. What did Simon say? Revisiting the bilingual advantage. Dev. Sci. 2007, 10, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.B.; Harper, S.N. What did Simon say? Revisiting the bilingual advantage. Dev. Sci. 2007, 10, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network Early Child Care and Children’s Development Prior to School Entry: Results from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2002, 39, 133–164. [CrossRef]

- Noble, K.G.; Norman, M.F.; Farah, M.J. Neurocognitive correlates of socioeconomic status in kindergarten children. Dev. Sci. 2004, 8, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, K.G.; Norman, M.F.; Farah, M.J. Neurocognitive correlates of socioeconomic status in kindergarten children. Dev. Sci. 2004, 8, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øie, M.G.; Sundet, K.; Haug, E.; Zeiner, P.; Klungsøyr, O.; Rund, B.R. Cognitive Performance in Early-Onset Schizophrenia and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A 25-Year Follow-Up Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, A., Pezzuti, L., Picone, L. (2012). WISC-IV. Contributo alla taratura italiana. Firenze: Giunti O.S.

- Orsolini, M.; Federico, F.; Vecchione, M.; Pinna, G.; Capobianco, M.; Melogno, S. How Is Working Memory Related to Reading Comprehension in Italian Monolingual and Bilingual Children? Brain Sci. 2022, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paap, K.R.; Johnson, H.A.; Sawi, O. Bilingual advantages in executive functioning either do not exist or are restricted to very specific and undetermined circumstances. Cortex 2015, 69, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J., Miller, C.A., Sanjeevan, T., Van Hell, J.G., Weiss, D.J. &Mainela-Arnold, E. Bilingualism and attention in typicallydeveloping children and children with developmental languagedisorder.Journal of Speech. Language, and Hearing Research 2019, 62(11), 4105–4118.

- Spinelli, G.; Goldsmith, S.F.; Lupker, S.J.; Morton, J.B. Bilingualism and executive attention: Evidence from studies of proactive and reactive control. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2022, 48, 906–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, S.; Kirst, C.; Bargmann, C.I. Neuromodulatory Control of Long-Term Behavioral Patterns and Individuality across Development. Cell 2017, 171, 1649–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, S.; Friesen, D.; Bialystok, E. Effect of Music Training on Promoting Preliteracy Skills: Preliminary Causal Evidence. Music. Percept. 2011, 29, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamm, L.; Loren, R.E.A.; Peugh, J.; Ciesielski, H.A. The Association of Executive Functioning With Academic, Behavior, and Social Performance Ratings in Children With ADHD. J. Learn. Disabil. 2020, 54, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieba, C.; Long, X.; Dewey, D.; Lebel, C. Young children in different linguistic environments: A multimodal neuroimaging study of the inferior frontal gyrus. Brain Cogn. 2018, 134, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, C.D.; Arredondo, M.M.; Yoshida, H. Differential effects of bilingualism and culture on early attention: a longitudinal study in the U.S., Argentina, and Vietnam. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. (2003). Wechsler intelligence scale for children (4th ed.). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

| Bilingual | Monolingual | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | St. deviation | Mean | St. deviation | |

| Raven’s Progressive Matrices (Z scores) | -0,13 | 0,86 | -0,16 | 0,88 |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (Z scores) | 94,09 | 14,56 | 96,2 | 14,88 |

| Digit Span (Z scores) | 8,57 | 2,63 | 8,98 | 2,81 |

| Non-Word Repetition (Z scores) | -1,12 | 1,68 | -1,08 | 1,58 |

| Letter-Number Sequencing (Z scores) | 9,07 | 3,30 | 9,3 | 4,13 |

| Immediate Narrative Memory(Z scores) | 9,65 | 3,34 | 10,27 | 2,89 |

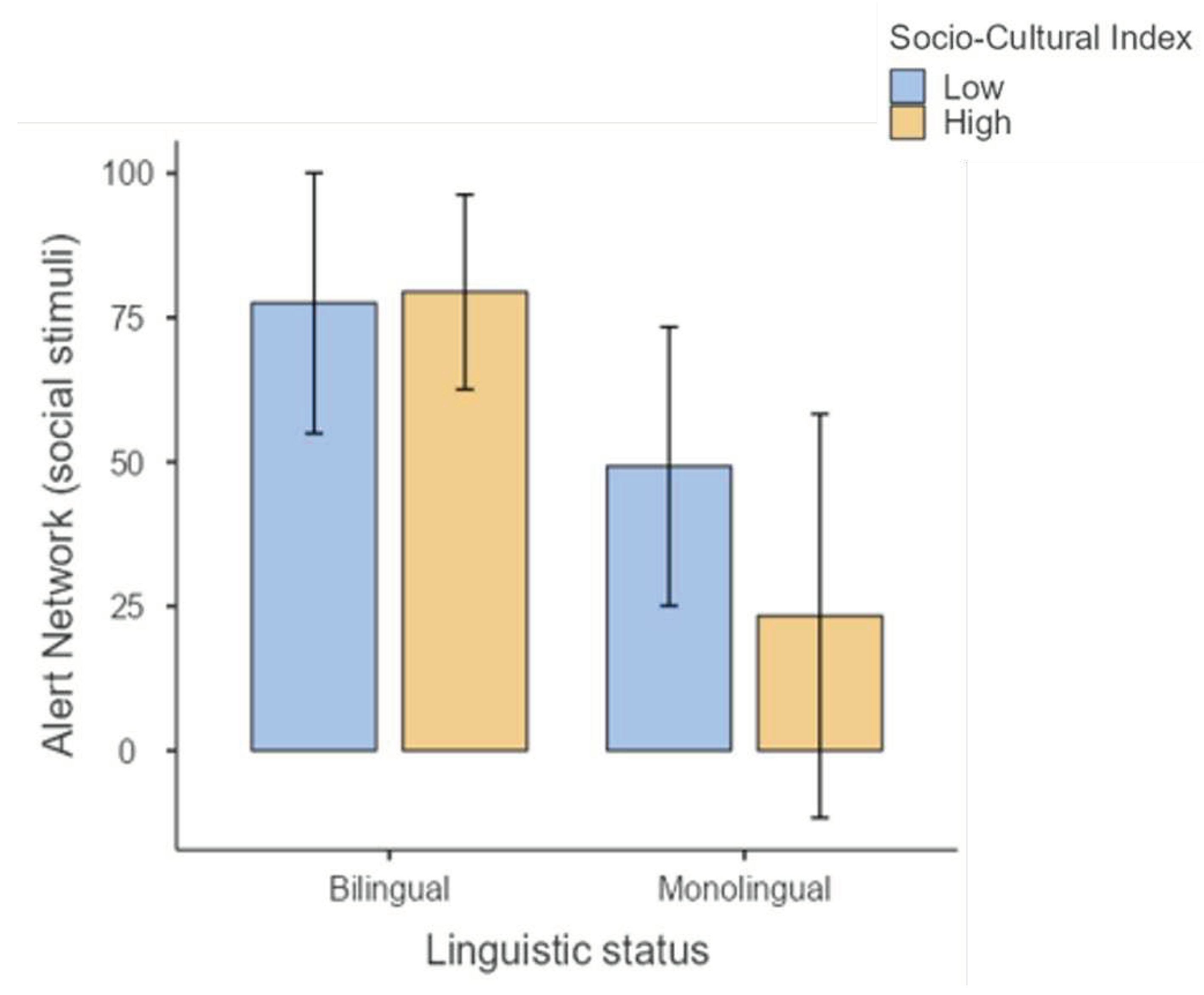

| Alerting Photo (rt) | 78,81 | 115,74 | 32,38 | 191,92 |

| Orienting Photo (rt) | 30,54 | 136,56 | 45,56 | 106,24 |

| Conflict Photo (rt) | 102,62 | 161,17 | 28,80 | 210,97 |

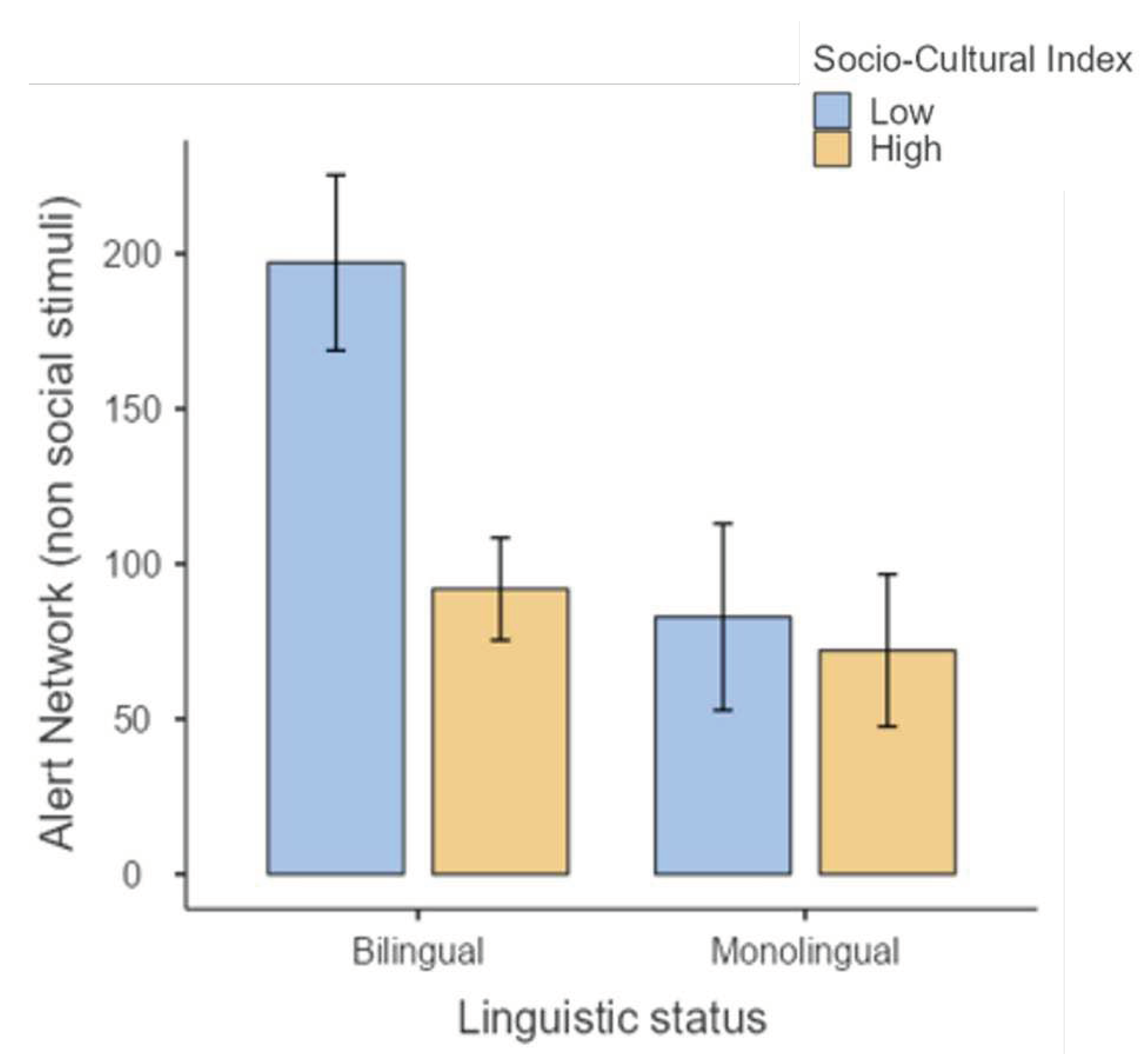

| Alerting Fish (rt) | 126,03 | 132,86 | 75,90 | 150,73 |

| Orienting Fish (rt) | 14,37 | 111,63 | 12,52 | 114,21 |

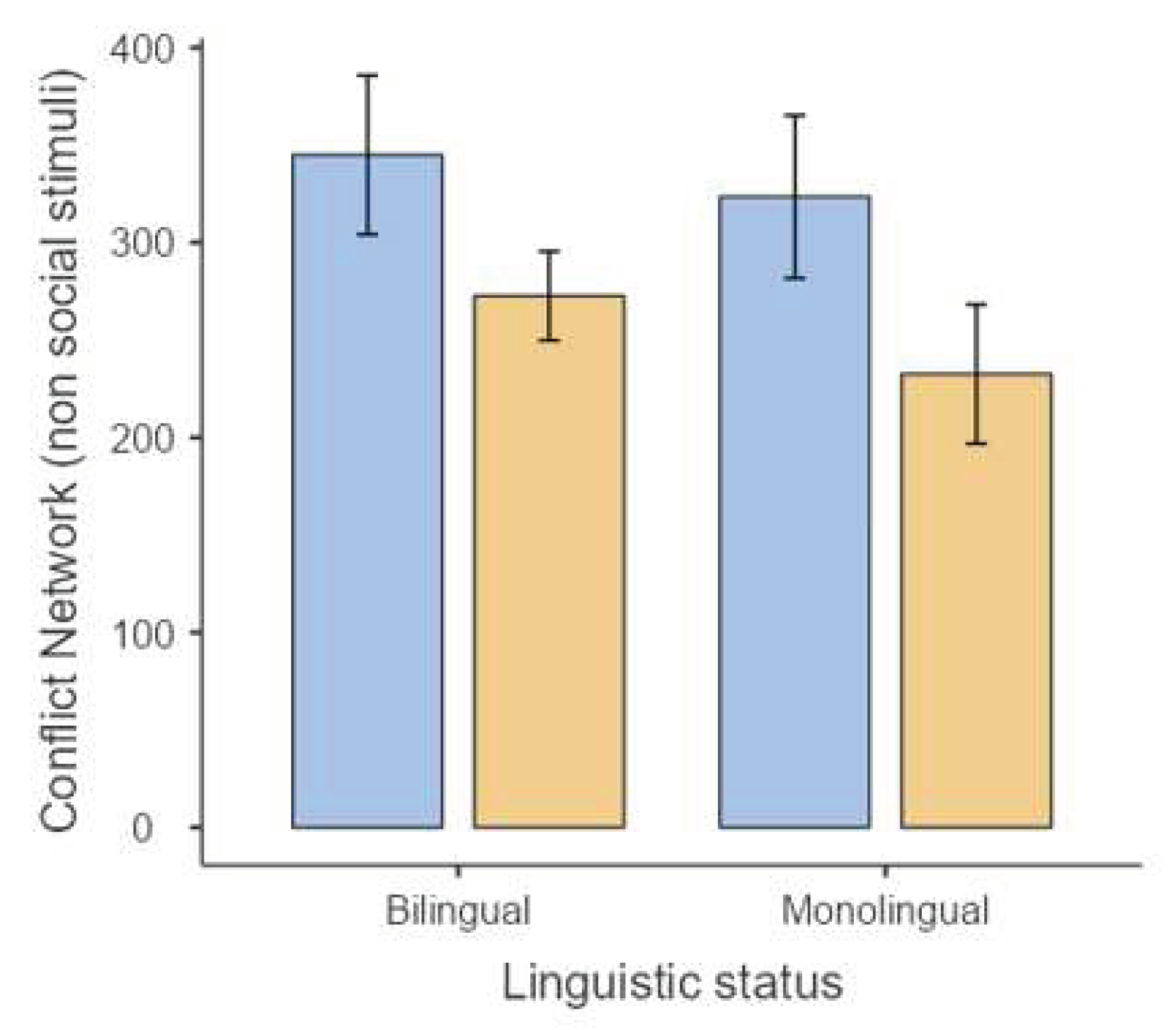

| Conflict Fish (rt) | 296,09 | 176,59 | 264,28 | 220,50 |

| Linguistic status | Sociocultural status | |||||

| F | p | η2 | F | p | η2 | |

| Raven’s Progressive Matrices | 0,04 | 0,843 | 0 | 0,367 | 0,546 | 0,003 |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test | 51,166 | 0 | 0,276 | 0,018 | 0,895 | 0 |

| Non-Word Repetition | 0,043 | 0,837 | 0 | 0,762 | 0,384 | 0,006 |

| Digit Span | 0,043 | 0,837 | 0 | 0,079 | 0,779 | 0,001 |

| Letter-Number Sequencing | 0,783 | 0,378 | 0,006 | 0,231 | 0,632 | 0,002 |

| Immediate Narrative Memory | 1,744 | 0,189 | 0,013 | 1,235 | 0,268 | 0,009 |

| Alerting Photo | 3,386 | 0,068 | 0,025 | 4,086 | 0,045 | 0,03 |

| Orienting Photo | 0,436 | 0,51 | 0,003 | 1,633 | 0,204 | 0,012 |

| Conflict Photo | 5,194 | 0,024 | 0,037 | 13,756 | 0 | 0,093 |

| Alerting Fish | 5,183 | 0,024 | 0,037 | 11,34 | 0,001 | 0,078 |

| Orienting Fish | 0,018 | 0,893 | 0 | 1,013 | 0,316 | 0,008 |

| Conflict Fish | 1,052 | 0,307 | 0,008 | 4,03 | 0,047 | 0,029 |

| Low sociocultural status | High sociocultural status | |||

| Mean | St.dev | Mean | St.dev | |

| Raven’s Progressive Matrices (Z Score) | -0,31 | 0,89 | -0,06 | 0,85 |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test | 94,09 | 14,56 | 96,2 | 14,88 |

| Digit Span | 8,57 | 2,63 | 8,98 | 2,81 |

| Non-Word Repetition | -1,12 | 1,69 | -1,09 | 1,61 |

| Letter-Number Sequencing | 9,07 | 3,30 | 9,3 | 4,13 |

| Immediate Narrative Memory | 9,65 | 3,34 | 10,27 | 2,89 |

| Alerting Photo | 63,98 | 111,51 | 54,16 | 175,51 |

| Orienting Photo | 58,05 | 144,81 | 27,040 | 110,34 |

| Conflict Photo | 6,49 | 176,11 | 100,11 | 187,90 |

| Alerting Fish | 142,48 | 149,81 | 83,01 | 136,00 |

| Orienting Fish | 20,83 | 110,49 | 9,82 | 113,80 |

| Conflict Fish | 334,65 | 195,81 | 254,58 | 194,48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).