Submitted:

17 May 2023

Posted:

18 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

3.1. The GENIUS project

- Building design that allows for the creation of parametrically different building shapes by varying their dimensions and configurations while keeping the area fixed.

- Energy and daylight simulations and optimization with a focus on Energy Use Intensity, Daylight Autonomy, and Spatial Daylight Autonomy.

- Office design that optimizes room layouts in areas with poor daylight and desk layouts in areas with optimal illuminance levels.

- Data analytics that allow for the analysis of data from optimization studies directly in Power BI.

- The GENIUS algorithm can be applied in both the concept and design phases. In the concept design phase, it can be used to:

- Optimize building layouts while considering energy and daylight performance.

- Optimize window and shading designs as well as Window-Wall Ratio (WWR) while considering energy and daylight performance.

- Define the best room and/or desk layout configuration in the office based on daylight simulations.

- In the design phase, it can be used by designers to:

- Validate the energy and daylight performance of the office arrangement.

- Define the best desk layout configuration in areas with good illuminance, considering the surrounding office space (existing rooms).

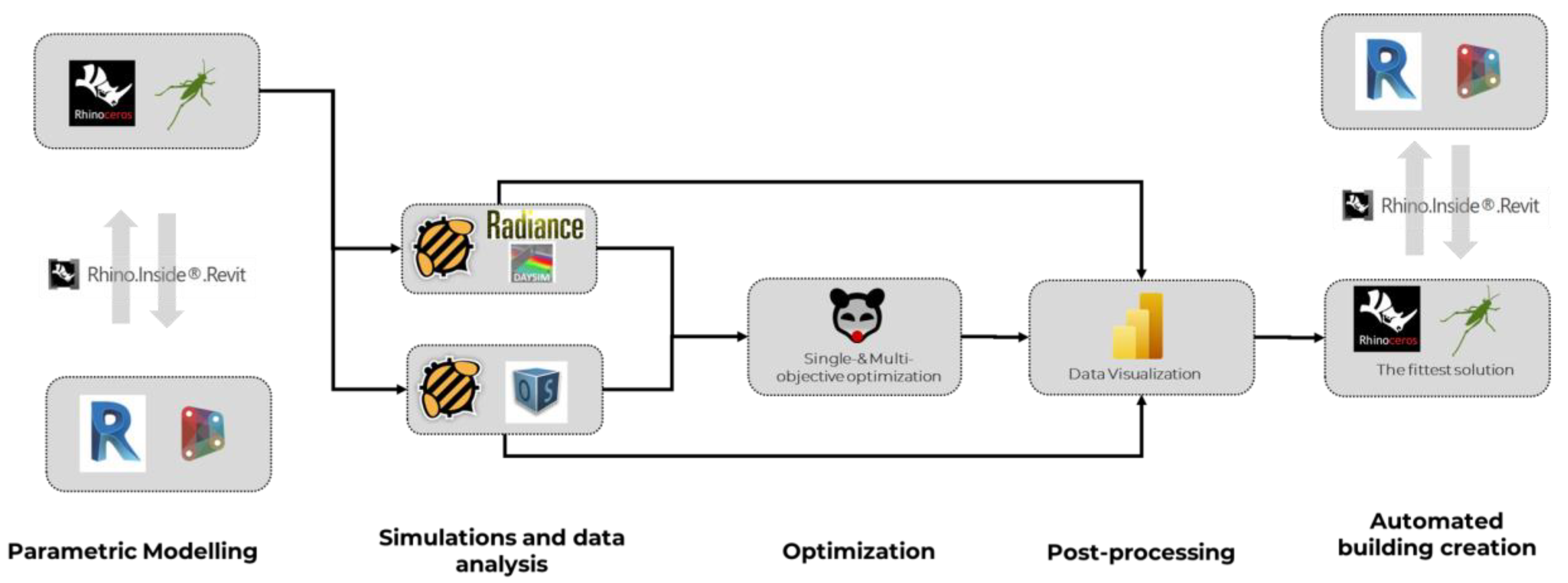

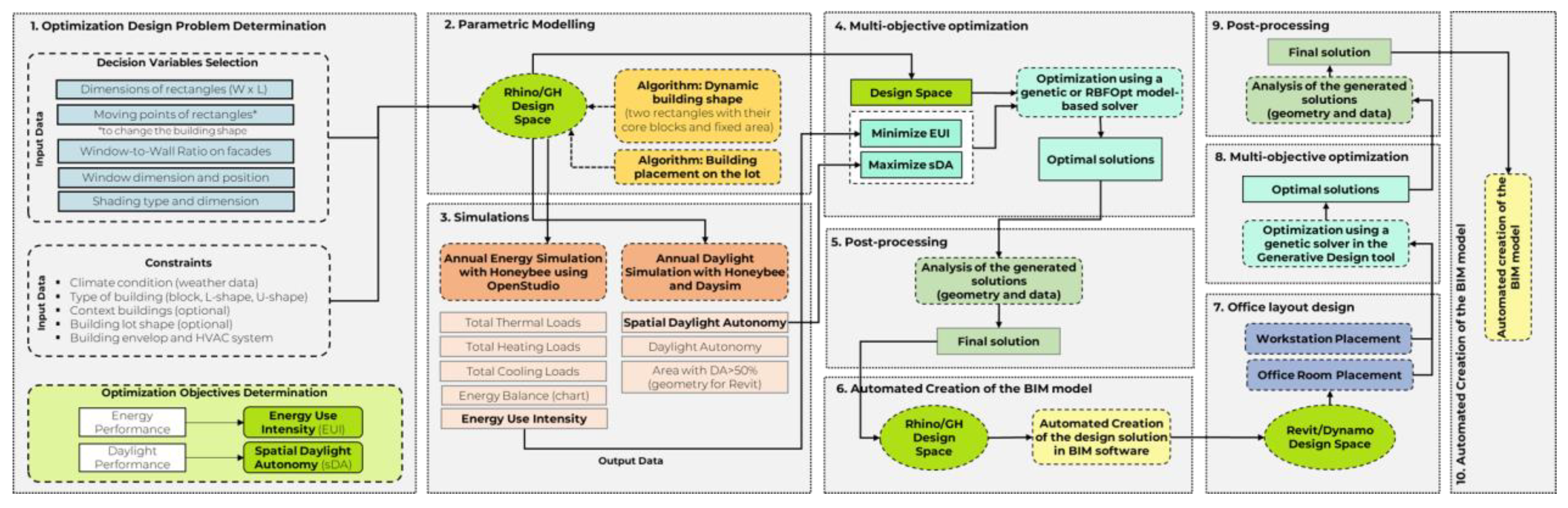

3.2. Design process and workflow

- Optimization Design Problem Determination: The designer must establish the goals for optimization, variables for decision-making, and constraints based on the specific conditions and requirements of the building design project. In the presented case study, two objectives were identified to improve energy and daylight performance: minimize Energy Use Intensity (EUI) and maximize spatial Daylight Autonomy (sDA).

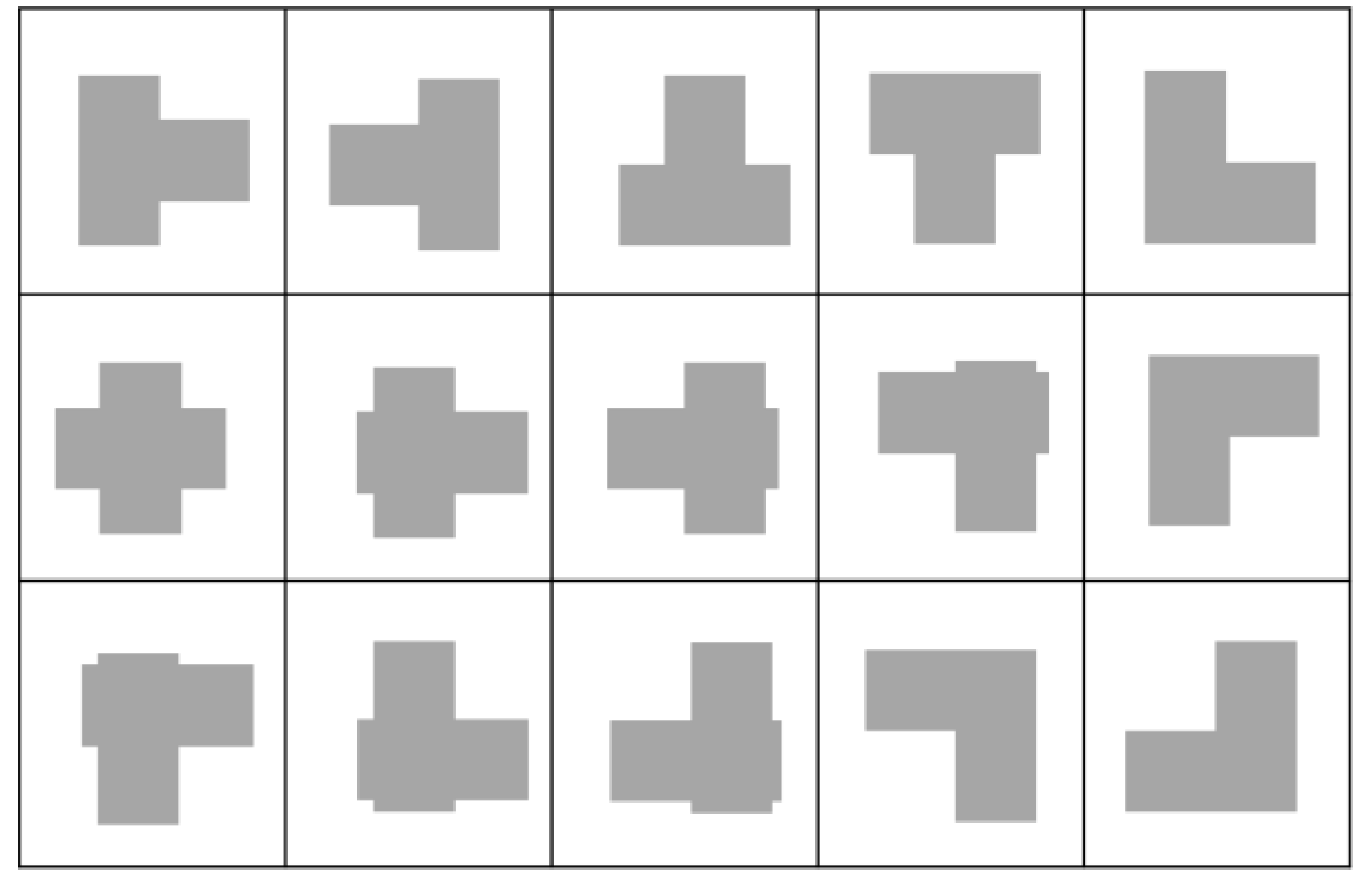

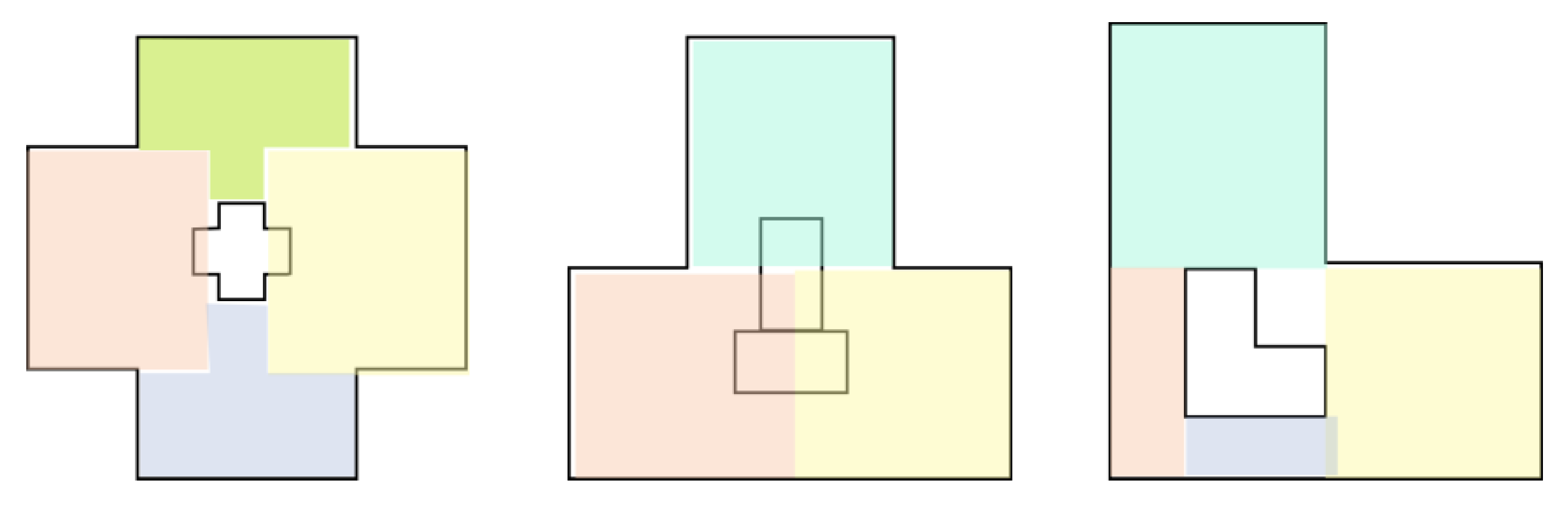

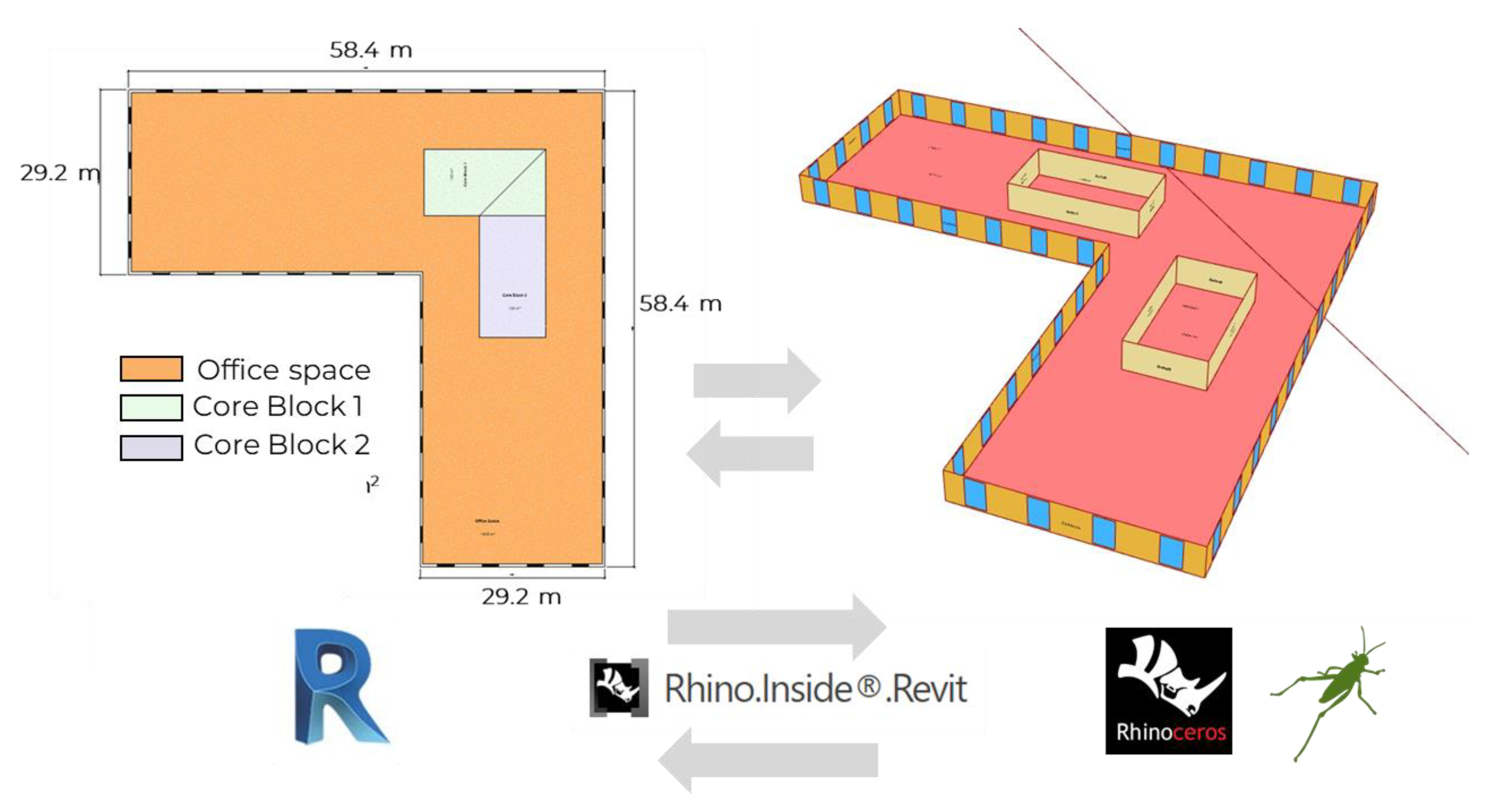

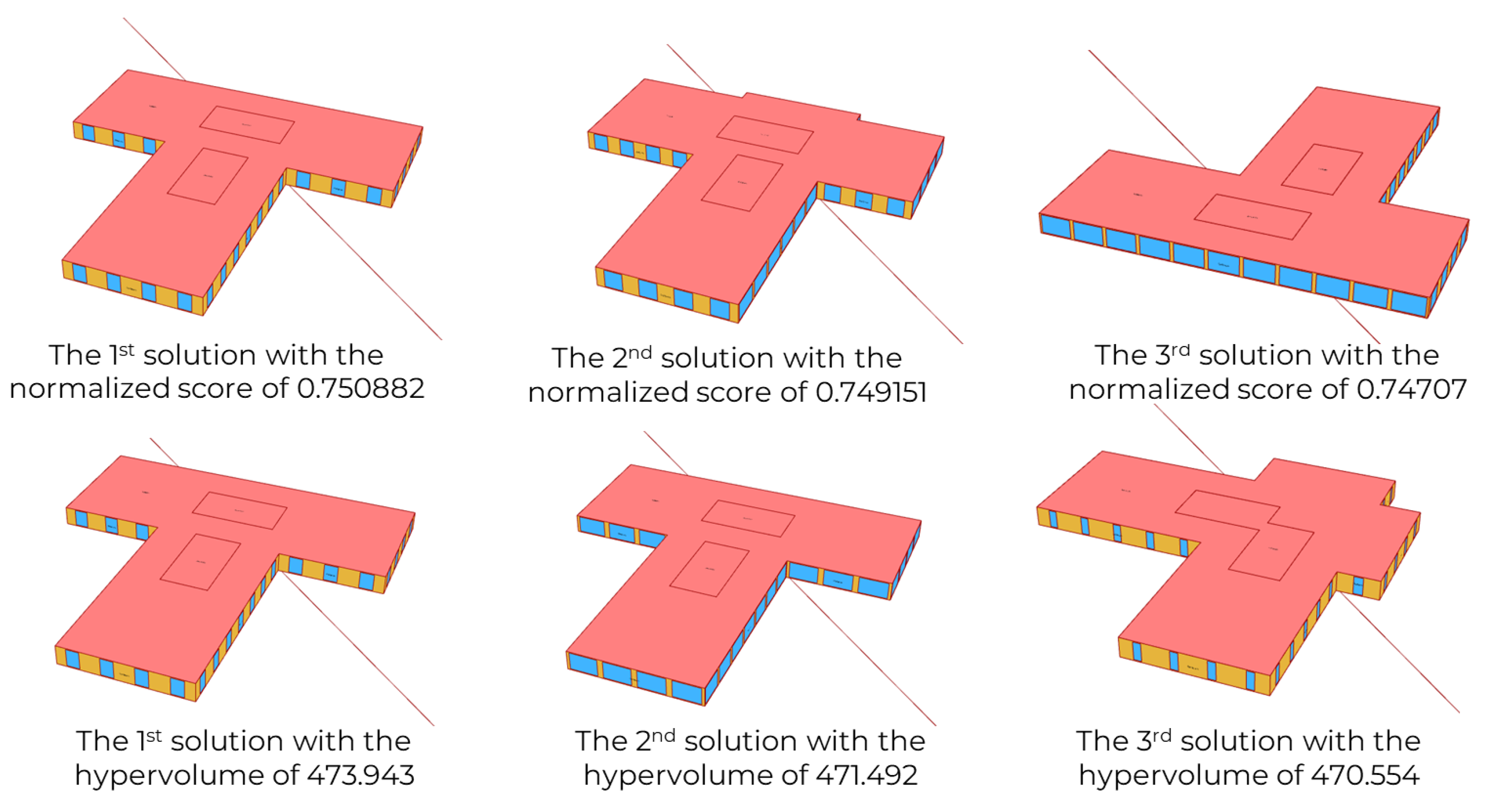

- Parametric modelling: The parametric model was created in Grasshopper based on the decision variables and objectives. The base model, which was imported from BIM software, has an L-shape with two core blocks containing lifts, stairs, and technical rooms. To allow for parametric representation and the ability to change shape (e.g., cross-shape, T-shape, etc.), two rectangular cuboids with core blocks were created that can move in relation to each other. The potential shape configurations are illustrated in Figure 4. Additionally, surrounding buildings (context) can be added to the model, and the building model can be placed on a lot. The position of the building model on the lot can be an additional variable to determine the optimal location relative to the context and to enhance energy and daylight performance.

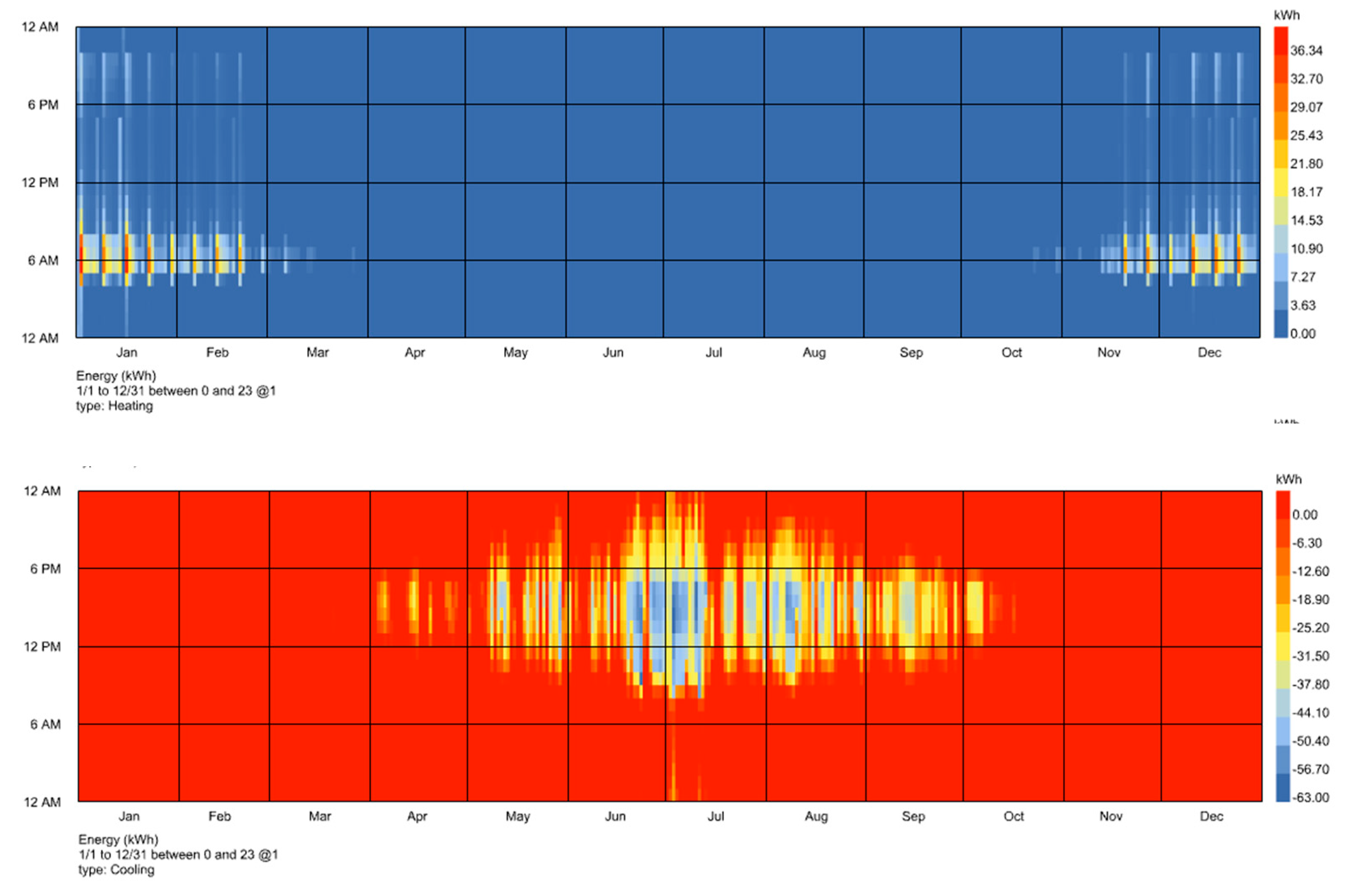

- Simulations: The energy and daylight simulations were conducted using Honeybee and Ladybug plugins within the Grasshopper platform. The OpenStudio component with the EnergyPlus engine was used for energy simulations, which provided outputs such as total heating and cooling loads, energy balance, and EUI. Annual daylight simulations were performed using the Daysim component, with outputs including Daylight Autonomy (DA) and sDA. For the optimization process, EUI and sDA metrics were considered.

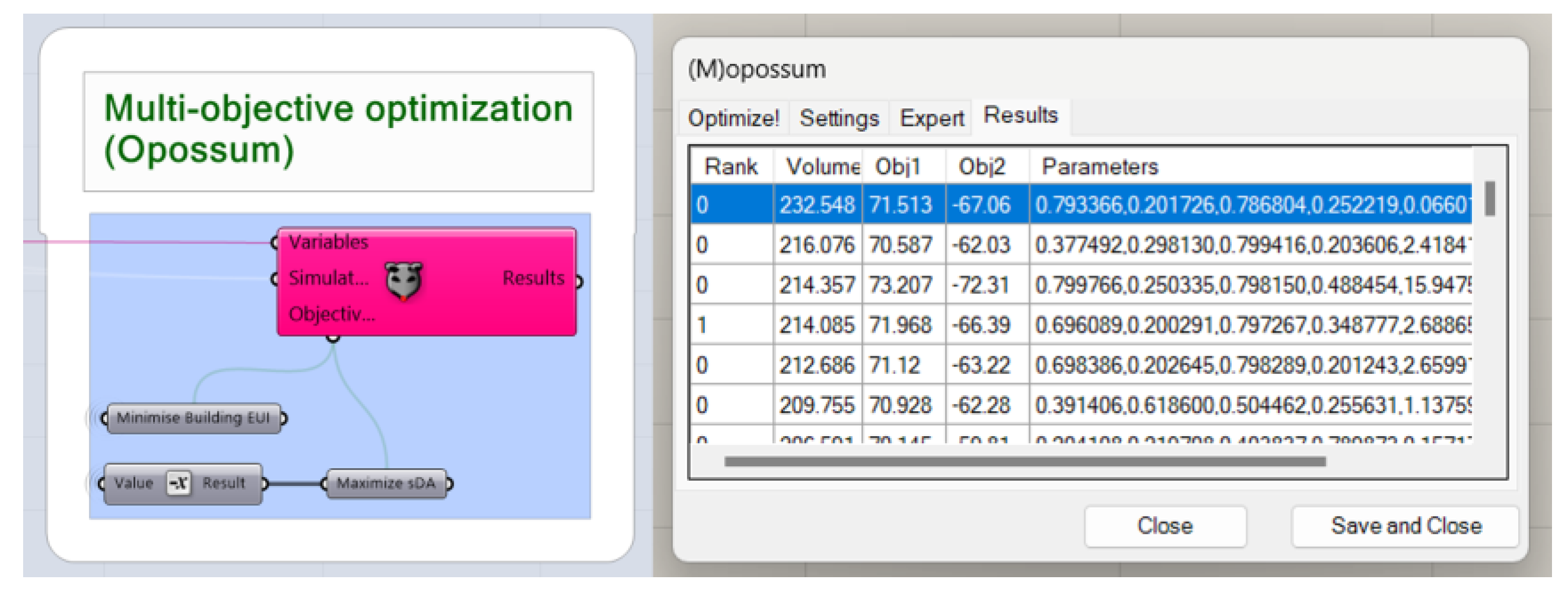

- Multi-objective optimization: MOO was performed considering two objectives: minimize EUI and maximize sDA. The Opossum plugin was used on the Grasshopper platform to run the optimization. This plugin was chosen since it uses RBFOpt model-based optimization. According to [11,12], RBFOpt is considered the fastest optimization algorithm with good results, especially if applied to problems that involve time-intensive simulations like daylight and energy simulations. BFOpt employs advanced machine learning methods to discover effective solutions with a minimal number of simulations. The optimization process comprises three primary steps: (1) scanning the model to identify a promising solution for evaluation, (2) executing simulations on the selected solution, and (3) refining the model based on the outcome of the simulations. Consequently, model-based approaches constantly boost the accuracy of the model [11].

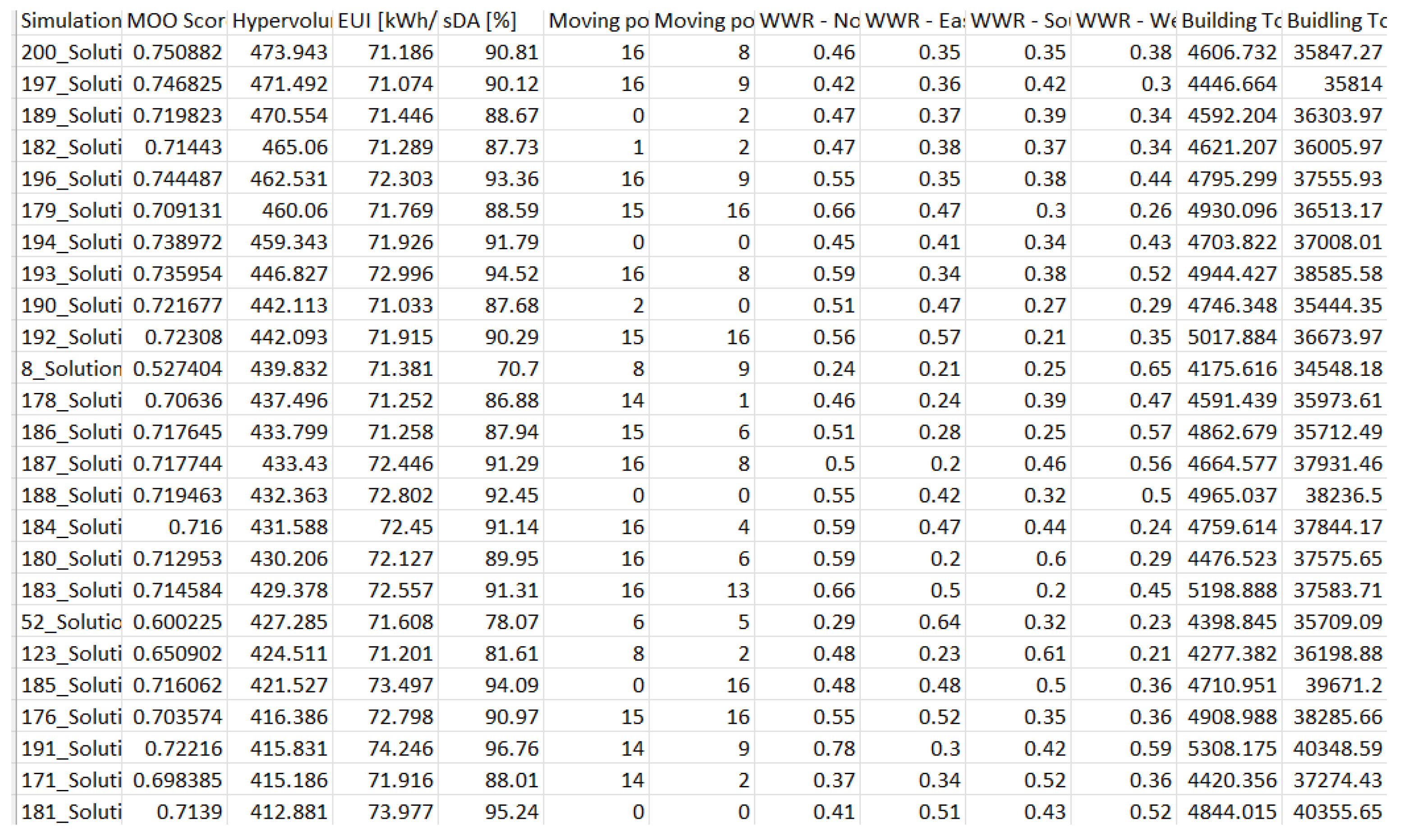

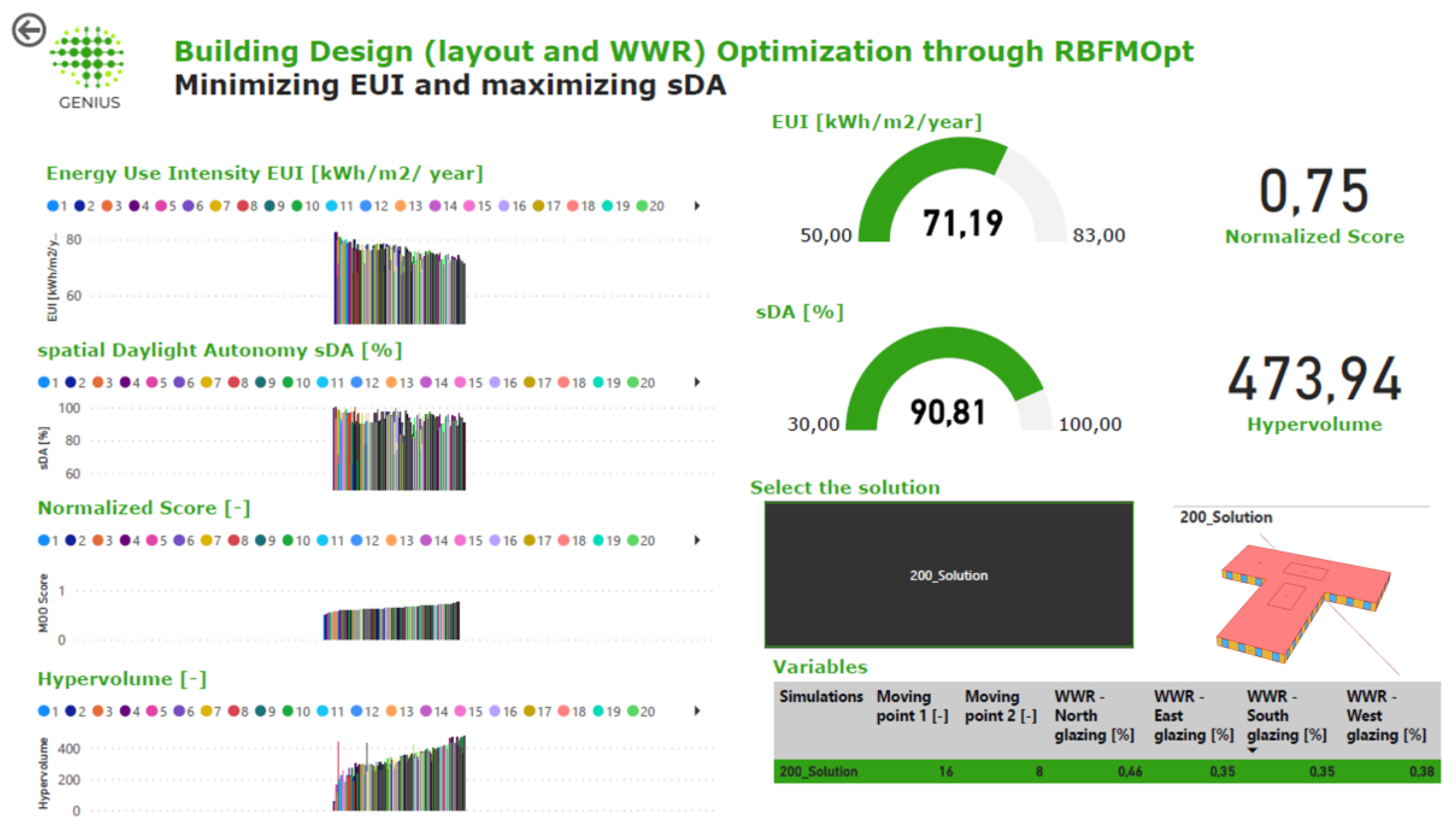

- Post-processing: Design variables and simulation output data were recorded for each optimization run in two ways: directly in the Opossum plugin and through the data recorder component linked to each variable and simulation output. These data were automatically transferred to an Excel file using a Grasshopper script. Using PowerBI, an interactive data visualization tool, a dashboard was created to allow designers to evaluate different solutions easily. Two ranking metrics were used to identify the most performing solutions: hypervolume, which measures the volume of the trade-off space covered by a Pareto front, and the average of normalized data for EUI and sDA, ranging from 0 to 1.

- Automated Creation of the BIM model: After identifying the most performing solution, the designer can automatically create a new BIM model in the original file that includes the base model. This is achieved using a Grasshopper script with Revit-aware components capable of creating native Revit elements. It is important to note that the new BIM model must be manually saved under a new name and the base model deleted. The new model can then be used for further building design.

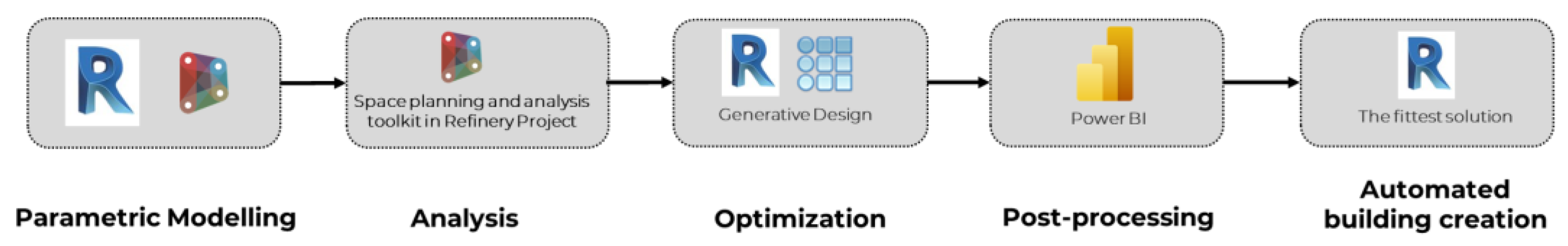

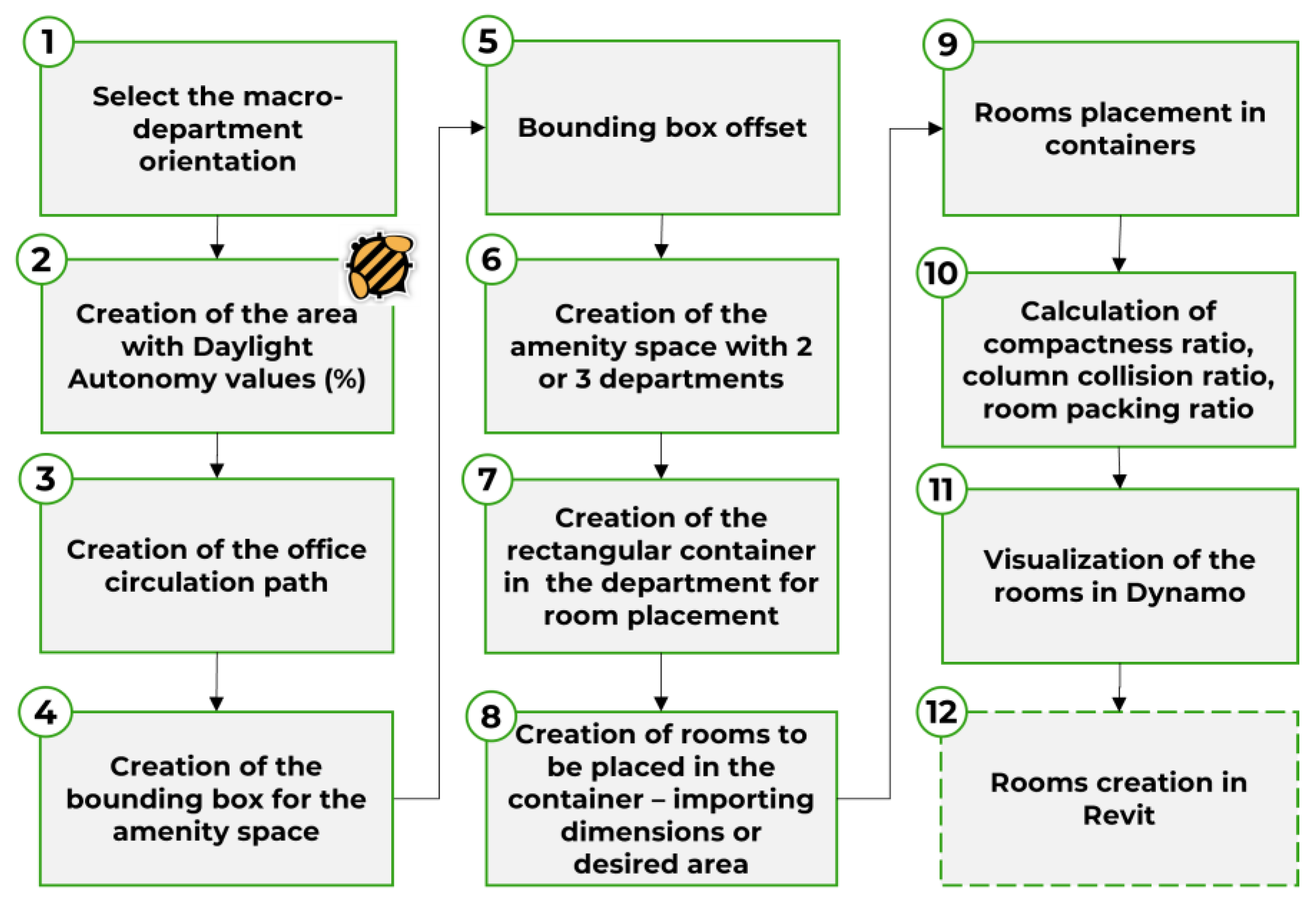

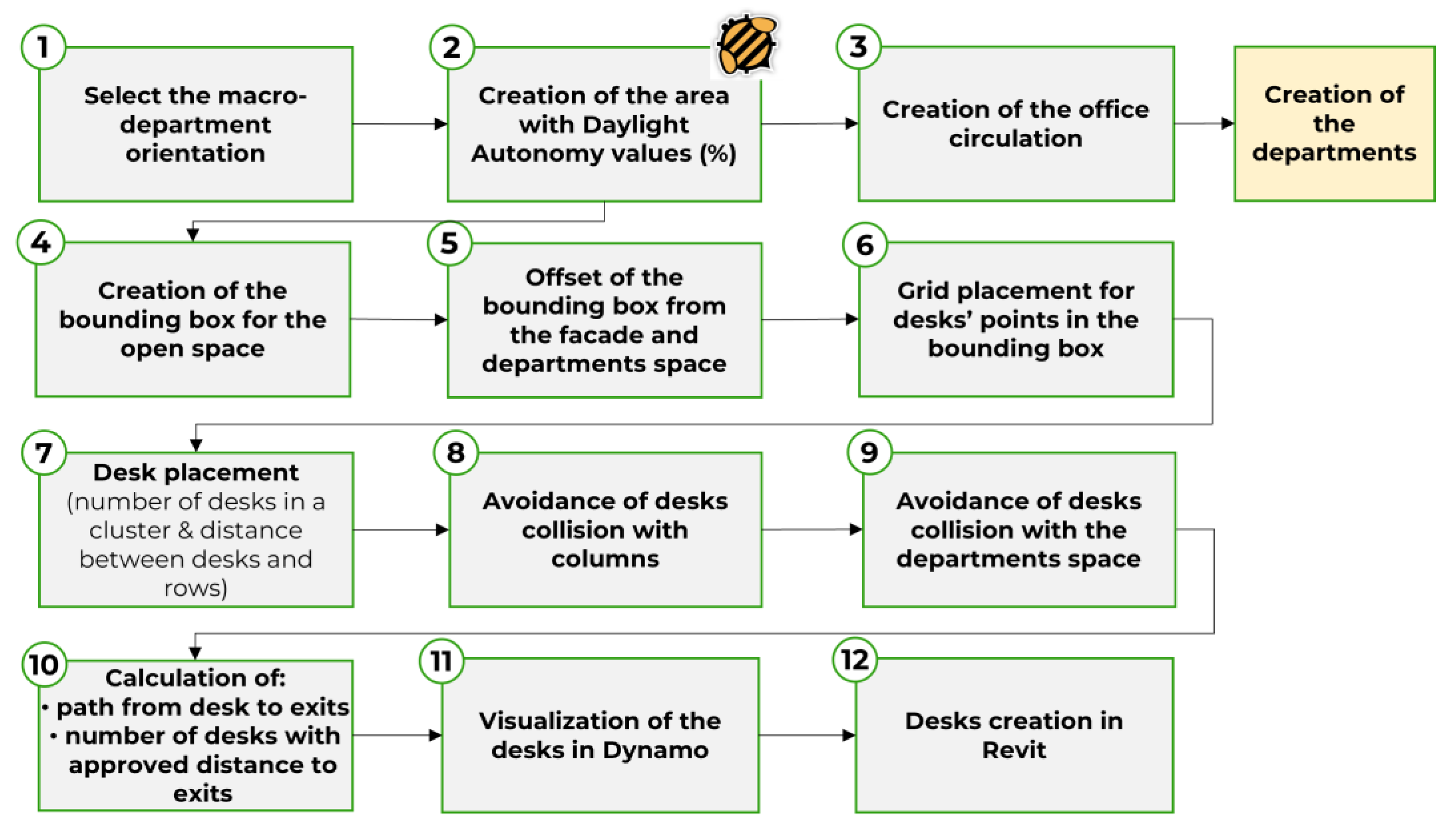

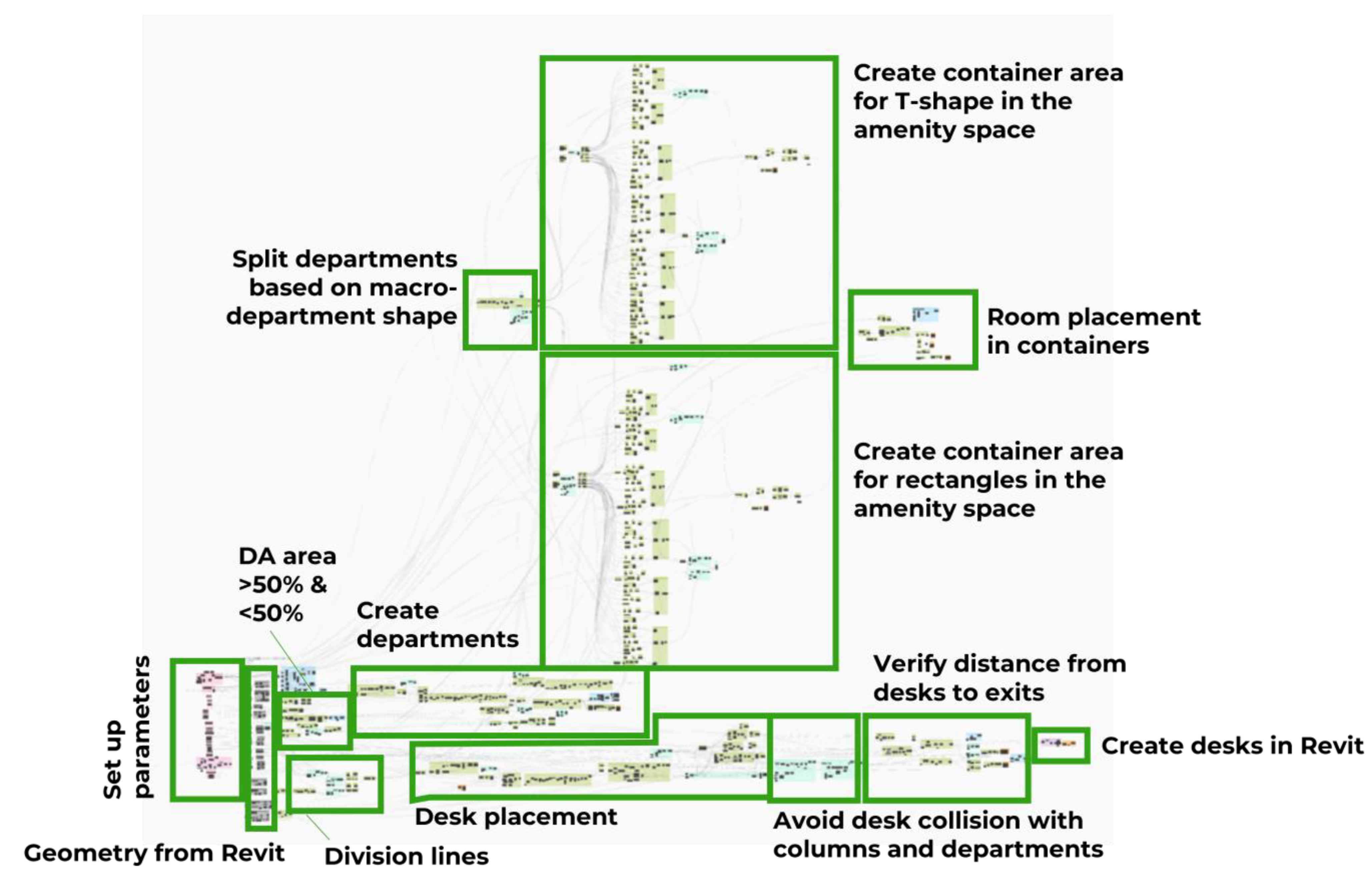

- Office layout design: This subprocess is carried out in Revit, a BIM software, and the Dynamo platform. The script consists of two parts: (1) placing rooms in departments with Daylight Autonomy (DA) values below 50%, and (2) placing desks in an open space area with DA values of 50% or higher. This rule ensures a comfortable workspace with adequate natural light according to the EN 17037:2022 standard. The standard specifies that an illuminance level of at least 300 lux should cover at least 50% of the building for at least half of the daylight hours in a year. The Refinery Toolkit package's 2D packing algorithm was adopted for room placement. Rooms are packed using a rectangular packer that offers three distinct strategies: packing based on rectangle area, long side, or short side. Each strategy results in a unique layout. Desk placement is based on grid object placement methods, allowing the designer to set parameters such as the number of desks in a cluster and the distance between rows and desks. The Space Analysis package's pathfinding algorithm was used to evaluate the distance between each desk and exits, to comply with fire safety standards and determine the maximum number of approved desks.

-

Multi-objective optimization: The office space can be optimized using the Generative Design tool in the Dynamo platform. Optimization can be carried out at two levels: room and desk placement. In the first case, the optimization goals are:

- Compactness ratio, indicating the percentage of the department's area that is occupied by rooms.

- Packing ratio, indicating the percentage of packed rooms versus rooms that are supposed to be packed.

- Column-room collision ratio is a metric that shows the impact of collisions between columns and rooms in the department.

For the first two metrics, a higher percentage yields better results, while the third metric should be minimized.In the second case, the optimization goals are:- A number of desks with an approved distance for the fire evacuation path.

- The average distance from a desk to an exit.

The first metric can be maximized or minimized based on the design goal, and the second metric should be minimized. - Post-processing: This subprocess is like point (5). Since the optimization process is performed for five objectives, a radar chart is used to display the scores for each objective. A larger filled area on the chart indicates a better solution.

- Automated BIM model update: After identifying the most effective solution, the designer can set up initial parameters for the selected solution in the script and automatically create objects in Revit software. The script enables the designer to create a desk layout automatically. While the rooms can also be created automatically, we believe that the architect should always review the room layout and treat the automated solution as a concept that needs further elaboration.

4. The GENIUS algorithm

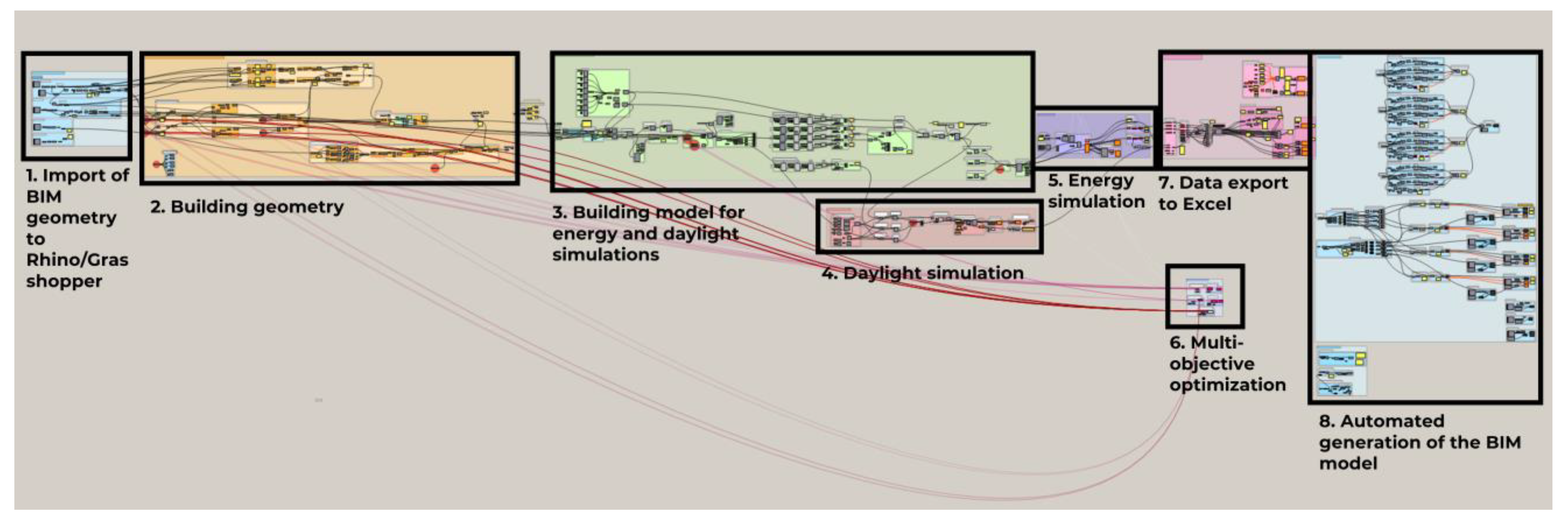

4.1. Energy and daylight optimization algorithm

- Import of BIM geometry to Rhino/Grasshopper: the base geometry of the office building is done in Revit. With the Rhino.Inside.Revit plugin for Revit, it's easy to directly access the Rhino/Grasshopper platform and develop a daylight and energy optimization algorithm. This plugin guarantees full integration between two platforms. Revit-aware components can be used to import Revit elements and data, such as rooms, floor height, window dimensions, number of windows, topography (building lot) and surrounding buildings.

- Building geometry: The geometry and data from point 1 are used to create parametrically the building model composed of two rectangular cuboids and core blocks. Additional buildings can be added to the model to enhance its surroundings, and it can be placed on a specific lot for further analysis.

- Building model for energy and daylight simulations: In this part of the script, programs, loads, and schedules are assigned to building zones. As a building program, a large office was utilized with two room programs: open office and stair, which are default settings provided by Honeybee based on ASHRAE 90.1 standards. To identify the indoor walls of core blocks, the adjacency problem (???) was solved. Subsequent parts of the script focus on defining the Wall-to-Window Ratio (WWR), HVAC system, building components, and creating windows and shading systems to produce the final building model for simulations.

- Energy simulation: This part of the script conducts an annual energy simulation using the OpenStudio component, which can calculate EUI, cooling loads, heating loads, and balance charts as output data. The EUI values are utilized for optimization purposes.

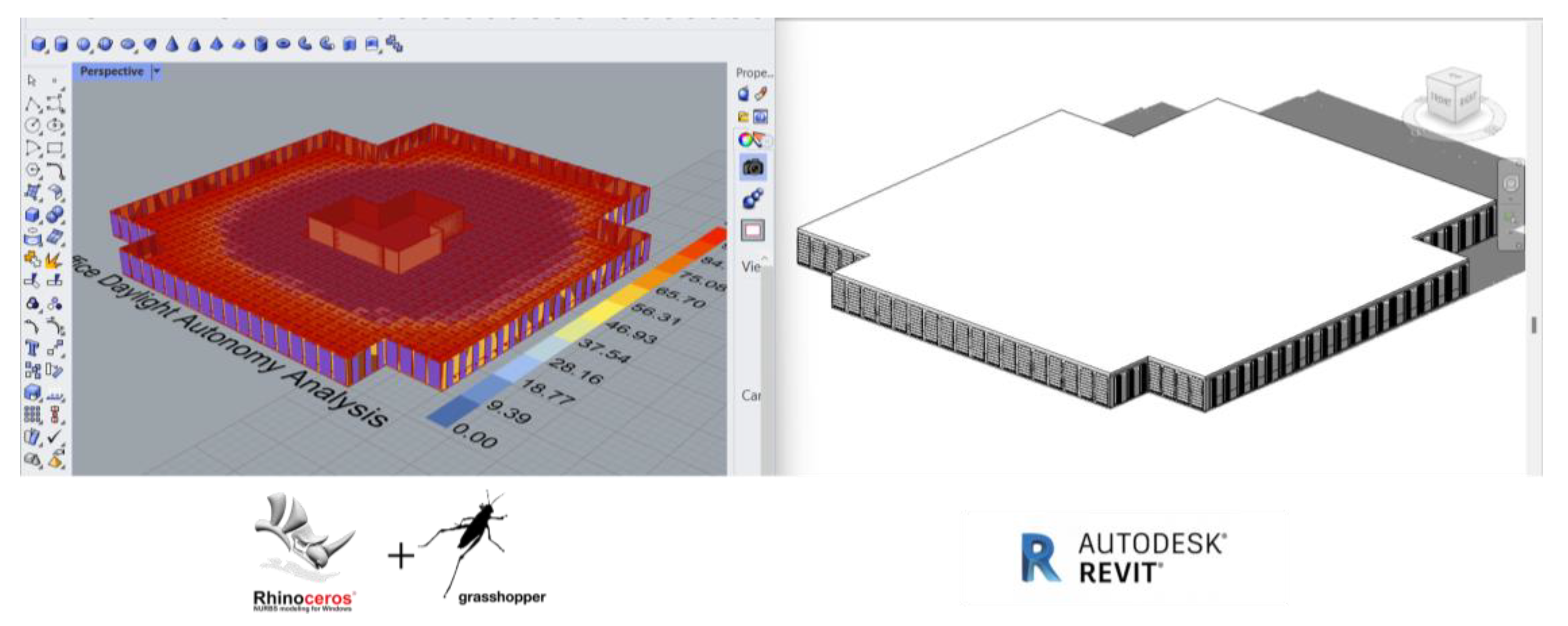

- Daylight simulation: This part of the script conducts annual daylight simulations using the Daysim component, following procedures outlined in the EN 17037:2022 standard. The simulations are conducted for an illuminance level of 300 lux with low-quality Radiance parameters. Although there may be some differences in output values when using different quality parameters, we opted for lower quality to maintain a fast and acceptable computation time. As output data, sDA and DA values are calculated. The DA values are necessary for defining building areas with values greater than or equal to 50% (acceptable for workstations) and values less than 50%.

- Multi-objective optimization: The MOO is performed using the Opossum plugin, which utilizes the RBFOpt model-based optimization method. The optimization component is linked to the input variables and fitness functions, which, in the case study, involve the maximization of sDA and the minimization of EUI.

- Data export to Excel: In this section, the script records data, including variables and output data, from the simulations conducted during the optimization process. The data is then sorted and scored. For EUI and sDA values scores are calculated by taking the average of the normalized data, which ranges from 0 to 1. The data are properly prepared and exported to an Excel file, to which the rank (hypervolume) from the optimization run in the Opossum plugin is manually added at the end. The Excel file can then be utilized in Power BI to analyse various design solutions generated by the optimization process.

- Automated generation of the BIM model: The final part of the script transfers the geometry of the optimized solution from Grasshopper to Revit, along with the geometry data related to the daylight simulation (DA) using Rhino.Inside.Revit plugin. This is accomplished using Revit-aware components. An example is shown in Figure 6. The optimised solution must be saved manually as a new Revit file.

4.2. Office layout optimization algorithm

- Macro-division of the building space: The algorithm can only analyse space enclosed in rectangular or T-shaped polygons, so the architect must divide the building into macro departments based on orientation (north, west, south, east). It's important to note that the macro-department area should include exit doors to calculate the path from the desk to the exit door. Additionally, the macro-department area should include all areas with DA faces previously imported from Grasshopper as a result of daylight simulation. Macro departments can be designed using a model line in Revit. Some examples of possible macro-division of the building space are presented in Figure 7.

- Department circulation: Design the circulation path for the department divisions.

- Columns: Design columns and fire exit doors for the office building.

- Desk: Import a desk family that will be used for desk layout optimization. It should be a single desk.

5. Case study

5.1. Referenced Building

5.2. Energy model

5.3. Daylight model

5.4. Parameters and Variables of the case study

| Model | Parameters | Settings |

|---|---|---|

| Parametric | Length and width of the Rectangle 1 | 23x60.5 m* |

| Width and length of the Rectangle 2 | 60.5x23 m** | |

| Energy | Window height | 2.7 m |

| Sill height | 0.15 m |

| Model | Variables | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Parametric | Moving point of the Rectangle 1 | 0-16 |

| Moving point of the Rectangle 2 | ||

| Energy | WWR north | 0.2-0.8 |

| WWR east | ||

| WWR south | ||

| WWR west |

6. Results

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tedesch, A.; Lombardi, D. The algorithms-aided design (AAD). In Book Informed Architecture; Hemmerling, M.; Cocchiarella, L.; Springer Cham, July 2017 pp. pp.33-38.

- Zboinska, M.A. Hybrid CAD/E platform supporting exploratory architectural design, Computer-Aided Design, 59, 2015, pp. 64-84. [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, Fakhri A. A. Hierarchical Evolutionary Algorithmic Design (HEAD) system for generating and evolving building design models. Diss. Queensland University of Technology, 2011.

- Eastman, C. M.; Teicholz, P.; Sacks, R.; Liston, K. BIM handbook: A guide to building information modeling for owners, managers, designers, engineers and contractors. John Wiley & Sons, USA, 2011.

- Eltaweel, A., Su, Y., Parametric design and daylighting: a literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, pp. 1086-1103. [CrossRef]

- Elghazi, Y.; Wagdy, A.; Mohamed, S.; Hassan, A. Daylighting Driven Design: Optimizing Kaleidocycle Façade For Hot Arid Climate. In Proceedings of the 5th German-Austrian IBPSA Conference: RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany, September 22-24, 2014.

- Burry, M. Scripting Cultures: Architectural Design and Programming. John Wiley & Sons, UK, 2011.

- Khan, S.; Awan, M.J. A generative design technique for exploring shape variations. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2018, 38, pp. 712–724. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, D.; Villaggi, L. Generative Design for Architectural Space Planning. Autodesk University. 2020. Available online: https://www.autodesk.com/autodesk-university/article/Generative-Design-Architectural-Space-Planning-2020 (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Singh, V.; Gu, N. Towards an integrated generative design framework. Des. Stud. 2012, 33, pp.185–207. [CrossRef]

- Wortmann, Thomas. Opossum-introducing and evaluating a model-based optimization tool for grasshopper. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference of the Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA), pp. 283-293, Hong Kong, April 5-8, 2017.

- De Luca, F.;Wortmann, T. Multi-Objective Optimization for Daylight Retrofit. In Proceedings of the 38th Conference on Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe, Berlin, Germany, September 16-18, 2020.

- Emmerich, MTM; Deutz, AH. A tutorial on multiobjective optimization: fundamentals and evolutionary methods, Nat. Comput., 2018, 17(3), pp. 585–609. [CrossRef]

- Leder, S.; Newsham, G.R.; Veitch, J.A.; Mancini, S.; Charles, K.E. Effects of office environment on employee satisfaction: a new analysis. Build. Res. Inf., 2016, 44, pp. 34-50.

- Al Horr, Y.; Arif, M.; Kaushik, A.; Mazroei, A.; Katafygiotou, M.; Elsarrag, E. Occupant productivity and office indoor environment quality: a review of the literature. Build. Environ., 2016, 105, pp. 369-389. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M, Mardaljevic, J and Lockley. A framework for Predicting the Non-visual Effects of Daylight - Part I: Photobiology-based model, Lighting Research & Technology, 2012, 44(1), pp. 37-53. [CrossRef]

- De Luca, F; Voll, H.; Thalfeldt, M. Comparison of Static and Dynamic Shading Systems for Office Buildings Energy Consumption and Cooling Load Assessment, Management of Envinron. Quality: An Int. Journal, 2018, 29(5), pp. 978-998. [CrossRef]

- Nazaroff, WW. Illumination, lighting technologies, and indoor environmental quality, Indoor Air, 2014, 24(3), pp. 225-226.

- Haase, M.; Grynning, S. Optimized Façade Design – Energy Efficiency, Comfort and Daylight in Early Design Phase, En. Procedia, 2017, 132, pp. 484-489.

- De Luca, F.; Voll, H.; Thalfeldt, M. Horizontal or Vertical Windows’ layout selection for shading devices optimization, Management of Envinron. Quality: An Int. Journal, 2016, 27(6), pp. 623-633. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F. Optimization of Daylighting and Energy Performance Using Parametric Design, Simulation Modeling, and Genetic Algorithms. Ph.D. Dissertation, Faculty of North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, 2017.

- Heschong, L.; Mahone, D. Windows and offices: A study of office worker performance and the indoor environment. California Energy Commission, 2003, pp. 1-5.

- Niclas, N.R. Using genetic algorithms in parametric building façade design to create different atmospheres. Ph.D. Dissertation, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark, 28 May 2019.

- Wortmann, T. Genetic Evolution vs. Function Approximation: Benchmarking Algorithms for Architectural Design Optimization, JCDE, 2019, 6(3), pp. 414-428. [CrossRef]

- Waibel, C.; Wortmann, T.; Evins, R.; Carmeliet, J. Building energy optimization: An extensive benchmark of global search algorithms. Energy and Buildings, 2019, 187, pp. 218-240. [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II’, IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput., 2002, 6(2), p. 182–197. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, H. MOEA/D: A Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithm Based on Decomposition, IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput., 2007, 11(6), p. 712–731. [CrossRef]

- Ko, R. Tuning and Benchmarking a Blackbox Optimization Algorithm, Master’s Thesis, Yale, 2019.

- Toutou, A.M.Y. Parametric approach for multi-objective optimization for daylighting and energy consumption in early stage design of office tower in new administrative capital city of Egypt. Academic Research Community Publication; IEREK: London, UK, 2019; 3, pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Besbas, S.; Nocera, F.; Zemmouri, N.; Khadraoui, M.A.; Besbas, A. Parametric-Based Multi-Objective Optimization Workflow: Daylight and Energy Performance Study of Hospital Building in Algeria. Sustainability, 2022, 14, 12652. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Bokel, R.; van den Dobbelsteen, A.; Sun, Y.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, Q. Optimization of thermal and daylight performance of school buildings based on a multi-objective genetic algorithm in the cold climate of China, Energy and Buildings, 2017, 139, pp. 371-384. [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, L.E.; Wang, J.; Brown, N.C. Quantifying potential dynamic façade energy savings in early design using constrained optimization, Building, and Environment. Build. Environ. 2022, 221, 109265. [CrossRef]

- Elghandour, A.; Saleh, A.; Aboeineen, O.; Elmokadem, A. Using Parametric Design To Optimize Building’s Façade Skin To Improve Indoor Daylighting Performance. In the Proceedings of the 3rd IBPSA-England Conference BSO 2016, Great North Museum, Newcastle, 12th-14th September 2016.

- Sun, C.; Liu, Q. Yunsong, H. Many-Objective Optimization Design of a Public Building for Energy, Daylighting and Cost Performance Improvement. Applied Sciences. 2020, 10, 2435. [CrossRef]

- Musau, F.; Steemers, K. Space Planning and Energy Efficiency in Office Buildings: The Role of Spatial and Temporal Diversity, Architectural Science Review, 2008, 51(2), pp. 133-145. [CrossRef]

- Yi, H. User-Driven Automation for Optimal Thermal-Zone Layout during Space Programming Phases. Architectural Science Review, 2016, 59(4), pp. 279–306. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, E.; Adélio, R.G.; Álvaro, G. An Approach to the Multi-Level Space Allocation Problem in Architecture Using a Hybrid Evolutionary Technique. Automation in Construction, 2013, 35, pp. 482–98.

- Michalek, J.; Ruchi C.; Panos P. Architectural Layout Design Optimization. Engineering Optimization, 2002, 34(5), pp. 37–41.

- Catalina, T.; Virgone, J.; Iordache V. Study on the impact of the building form on the energy consumption. In Proceedings of Building Simulation 2011: 12th Conference of International Building Performance Simulation Association, Sydney, Australia, 14-16 November 2011.

- Liggett, R.S. Automated facilities layout: past, present and future. Automation in construction, 2000, 9(2), pp. 197-215. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, D.; Lau, D.; Locke, J.; Stoddart, J.; Villaggi, L.; Wang, R.; Zhao, D.; Benjamin, D. Project Discover: An Application of Generative Design for Architectural Space Planning. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Simulation for Architecture and Urban Design, 2017, 7, pp. 1–8.

- Cheng, C.; Ninić, J.; Tizani, W. Parametric Virtual Design-Based Multi-Objective Optimization for Sustainable Building Design. Intelligent Computing in Engineering and Architecture, 2018.

- Autodesk University. Generative Design for Complex Buildings: Optimizing Spaces and Flows with Dynamo and Refinery. Available online: https://medium.com/autodesk-university/generative-design-for-complex-buildings-optimizing-spaces-and-flows-with-dynamo-and-refinery-98881be34fa7 (accessed on 11th April 2023).

| Thermal zone settings: Open office | |

|---|---|

| People | 0.057 people/m2 |

| Lighting | 6.6 W/m2 |

| Electric Equipment | 7.6 W/m2 |

| Infiltration | 0.000227 m3/s-m2 |

| Ventilation | 0.0024 m3/s-person |

| Setpoint | H: 21 ºC, C:24 ºC |

| Thermal zone settings: Stair | |

|---|---|

| People | - |

| Lighting | 5.3 W/m2 |

| Electric Equipment | - |

| Infiltration | 0.000227 m3/s-m2 |

| Ventilation | - |

| Setpoint | H: 21 ºC, C:24 ºC |

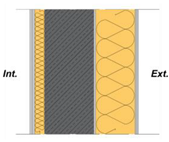

| Wall 01 | Layers | Thickness [mm] | Thermal conductivity [W/(m*K) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Interior finishing (plaster) | 10 | 0.8 |

| Gypsum fibreboard | 25 | 0.36 | |

| Insulation (Rockwool) | 50 | 0.033 | |

| Concrete wall | 250 | 2.3 | |

| Adhesive | 10 | 0.16 | |

| Insulation (Rockwool)Basecoat | 2006 | 0.0350.16 | |

| Exterior finishing (plaster) | 10 | 0.8 |

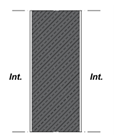

| Wall 02 | Layers | Thickness [mm] | Thermal conductivity [W/(m*K) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Interior finishing (plaster) | 10 | 0.8 |

| Concrete wall | 250 | 2.3 | |

| Exterior finishing (plaster) | 10 | 0.8 |

| Materials | Int. wall | Ext. wall | Floor | Ceiling | Ground plane | Shading system | Windows |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reflectance [%] | 50 | 20 | 20 | 70 | 20 | 70 | - |

| Transmissivity [%] | - | - | - | - | - | - | 70 |

| Radiance parameters | -aa | -ab | -ad | -ar | -as |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0.25 | 3 | 5000 | 16 | 128 |

| Ranking | Solution | Ranking value | EUI [kWh/m2/year] |

sDA [%] |

WWR North | WWR - East | WWR - South | WWR - West |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypervolume | 1 | 473.943 | 71.186 | 90.81 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.38 |

| 2 | 471.492 | 71.074 | 90.12 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.3 | |

| 3 | 470.554 | 71.446 | 88.67 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.34 | |

| Normalized EUI and sDA | 1 | 0.750882 | 71.186 71.186 |

90.81 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.38 |

| 2 | 0.749151 | 90.65 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.38 | ||

| 3 | 0.74707 | 71.482 | 91.29 | 0.5 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).