Submitted:

11 May 2023

Posted:

12 May 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

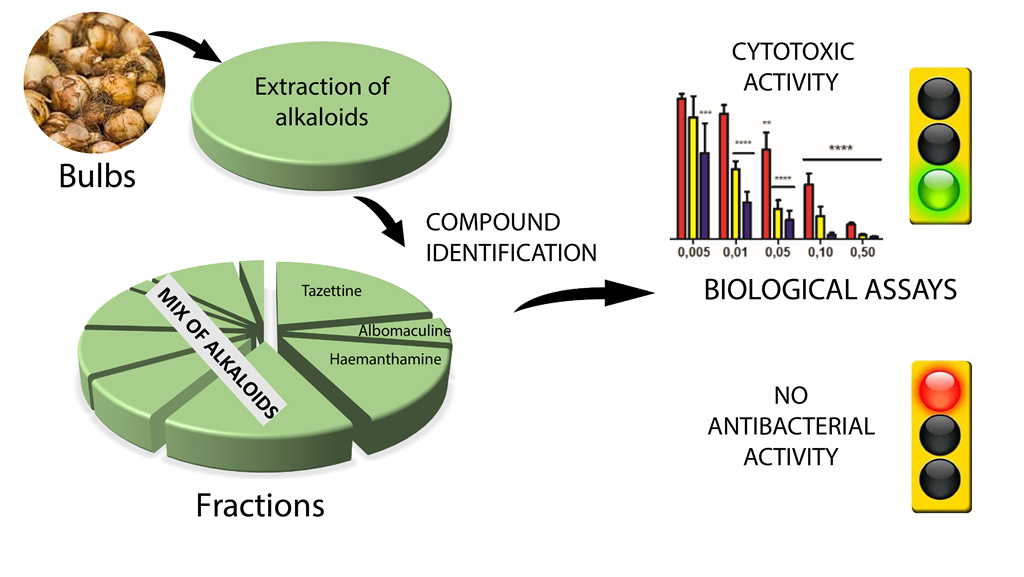

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

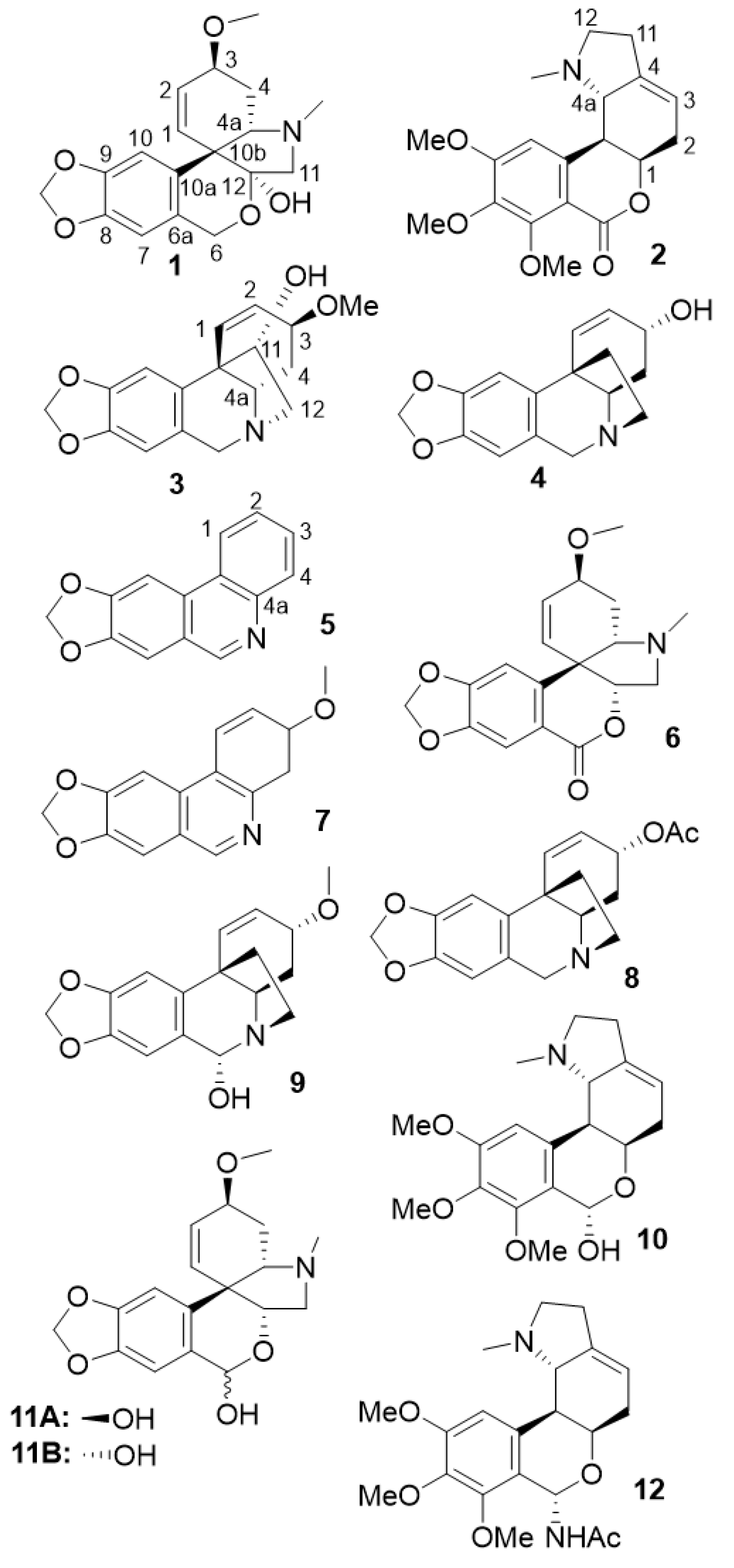

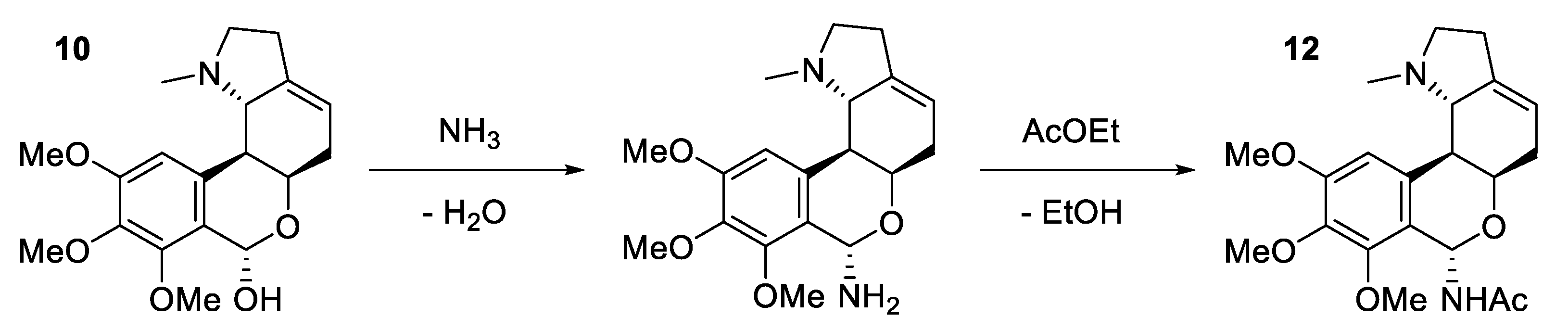

2.1. Phytochemical characterization of S. miniatum bulb extract

2.2. Biological activities of S.miniatum bulb extract

2.2.1. Cytotoxic activities against A431 human epidermoid carcinoma cells

2.2.2. Cytotoxic activities against Jurkat human acute T-leukemia cells

2.2.3. Antibacterial activities

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant material

4.2. Chemicals

4.3. Preparation of the alkaloid-enriched extract

4.4. Centrifugal Partition Chromatography

4.5. UPLC-HRMS

4.6. NMR

4.7. Cytotoxic activity

4.7.1. Cell cultures

4.7.2. Cell viability assays

4.7.3. Statistical analysis

4.8. Preparation of the extracts for antibacterial activity

4.8.1. Bacterial strains and antibacterial assay

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| COCONUT | COlleCtion of Open Natural ProdUcTs |

| CPC | Centrifugal partition chromatography |

| KNApSAcK | Kurokawa Nakamura Asah personal Shinbo Altaf-Ul-Amin computer Kanaya |

| MtBE | Methyl tert-butyl ether |

| NMReDATA | NMR extracted data |

| RPMI | Roswell Park memorial institute |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| TEA | Triethylamine |

| UNPD | Universal natural products database |

| UPLC | Ultra performance liquid chromatography |

References

- Nair, J.J.; van Staden, J. Pharmacological and Toxicological Insights to the South African Amaryllidaceae. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 62, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastida, J.; Lavilla, R.; Viladomat, F. Chapter 3 Chemical and Biological Aspects of Narcissus Alkaloids. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology; Cordell, G.A., Ed.; Academic Press, 2006; Vol. 63, pp. 87–179.

- Lianza, M.; Verdan, M.H.; de Andrade, J.P.; Poli, F.; de Almeida, L.; Costa-Lotufo, L.; Cunha Neto, Á.; Oliveira, S.; Bastida, J.; Batista, A.; et al. Isolation, Absolute Configuration and Cytotoxic Activities of Alkaloids from Hippeastrum Goianum (Ravenna) Meerow (Amaryllidaceae). J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgorashi, E.; Stafford, G.; van Staden, J. Acetylcholinesterase Enzyme Inhibitory Effects of Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids. Planta Med. 2004, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lao, Z.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Long, H.; Li, D.; Lin, L.; Liu, X.; Yu, L.; Liu, W.; et al. Antiviral Activity of Lycorine against Zika Virus in Vivo and in Vitro. Virology 2020, 546, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, J.J.; Wilhelm, A.; Bonnet, S.L.; van Staden, J. Antibacterial Constituents of the Plant Family Amaryllidaceae. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 4943–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, J.J. The Plant Family Amaryllidaceae: Special Collection Celebrating the 80th Birthday of Professor Johannes van Staden. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1934578X1987293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, J.W. Herbal Curing by Qollahuaya Andeans. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1982, 6, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévi-Strauss, C. The Use of Wild Plants in Tropical South America. Econ. Bot. 1952, 6, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, A.W. A New Species of Eucrosia and a New Name in Stenomesson (Amaryllidaceae). Brittonia 1985, 37, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, A.; Jost, L.; Oleas, N. Two New Species of Endemic Ecuadorean Amaryllidaceae (Asparagales, Amaryllidaceae, Amarylloideae, Eucharideae). PhytoKeys 2015, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boit, H.-G.; Döpke, W. Alkaloide aus Urceolina-, Hymenocallis-, Elisena-, Calostemma-, Eustephia- und Hippeastrum-Arten. Chem. Ber. 1957, 90, 1827–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girault, L. Kallawaya, guérisseurs itinérants des Andes: Recherches sur les pratiques médicinales et magiques; IRD Éditions, 2018; ISBN 978-2-7099-1840-4.

- Gaudêncio, S.P.; Pereira, F. Dereplication: Racing to Speed up the Natural Products Discovery Process. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 779–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubert, J.; Nuzillard, J.-M.; Renault, J.-H. Dereplication Strategies in Natural Product Research: How Many Tools and Methodologies behind the Same Concept? Phytochem. Rev. 2017, 16, 55–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knolker, H. The Alkaloids; Elsevier, 2020; ISBN 978-0-12-820981-3.

- Lianza, M.; Leroy, R.; Machado Rodrigues, C.; Borie, N.; Sayagh, C.; Remy, S.; Kuhn, S.; Renault, J.-H.; Nuzillard, J.-M. The Three Pillars of Natural Product Dereplication. Alkaloids from the Bulbs of Urceolina Peruviana (C. Presl) J.F. Macbr. as a Preliminary Test Case. Molecules 2021, 26, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renault, J.-H.; Nuzillard, J.-M.; Le Crouérour, G.; Thépenier, P.; Zèches-Hanrot, M.; Le Men-Olivier, L. Isolation of Indole Alkaloids from Catharanthus Roseus by Centrifugal Partition Chromatography in the PH-Zone Refining Mode. J. Chromatogr. A 1999, 849, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotland, A.; Chollet, S.; Diard, C.; Autret, J.-M.; Meucci, J.; Renault, J.-H. , Marchal, L. Industrial Case Study on Alkaloids Pu-rification by PH-Zone Refining Centrifugal Partition Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A, 2016, 1474, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Andrade, J.P.; Guo, Y.; Font-Bardia, M.; Calvet, T.; Dutilh, J.; Viladomat, F.; Codina, C.; Nair, J.J.; Zuanazzi, J.A.S.; Bastida, J. Crinine-Type Alkaloids from Hippeastrum Aulicum and H. Calyptratum. Phytochemistry 2014, 103, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet Nguyen, K.; Laidmäe, I.; Kogermann, K.; Lust, A.; Meos, A.; Viet Ho, D.; Raal, A.; Heinämäki, J.; Thi Nguyen, H. Preformulation Study of Electrospun Haemanthamine-Loaded Amphiphilic Nanofibers Intended for a Solid Template for Self-Assembled Liposomes. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viladomat, F.; Codina, C.; Bastida, J.; Mathee, S.; Campbell, W.E. Further Alkaloids from Brunsvigia Josephinae. Phytochemistry 1995, 40, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viladomat, F.; Sellés, M.; Cordina, C.; Bastida, J. Alkaloids from Narcissus Asturiensis. Planta Med. 1997, 63, 583–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viladomat, F.; Bastida, J.; Tribo, G.; Codina, C.; Rubiralta, M. Alkaloids from Narcissus Bicolor. Phytochemistry 1990, 29, 1307–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, J.; Forgo, P.; Szabó, P. A New Phenanthridine Alkaloid from Hymenocallis × Festalis. Fitoterapia 2002, 73, 749–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.A.; El Saved, H.M.; Abdalliah, O.M.; Steglich, W. Oxocrinine and Other Alkaloids from Crinum Americanum. Phytochemistry 1986, 25, 2399–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm, A.W.; Ali, A.A.; Ramadan, M.A. 13C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra of Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids. I—Alkaloids with the Crinane Skeleton. Magn. Reson. Chem. 1985, 23, 804–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, S.W.; Debenham, J.S. Total Syntheses of (−)-Haemanthidine, (+)-Pretazettine, and (+)-Tazettine. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, S.; Kihara, M.; Shingu, T.; Shingu, K. Transformation of Tazettine to Pretazettine. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 1980, 28, 2924–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, J.P.; Pigni, N.B.; Torras-Claveria, L.; Berkov, S.; Codina, C.; Viladomat, F.; Bastida, J. Bioactive Alkaloid Extracts from Narcissus Broussonetii: Mass Spectral Studies. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2012, 70, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkov, S.; Osorio, E.; Viladomat, F.; Bastida, J. Chemodiversity, Chemotaxonomy and Chemoecology of Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids. Alkaloids Chem. Biol. 2020, 83, 113–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünver, N.; Gözler, T.; Walch, N.; Gözler, B.; Hesse, M. Two Novel Dinitrogenous Alkaloids from Galanthus Plicatus Subsp. Byzantinus (Amaryllidaceae). Phytochemistry 1999, 50, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltese, F.; van der Kooy, F.; Verpoorte, R. Solvent Derived Artifacts in Natural Products Chemistry. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009, 4, 1934578X0900400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, S.; Wieske, L.H.E.; Trevorrow, P.; Schober, D.; Schlörer, N.E.; Nuzillard, J.-M.; Kessler, P.; Junker, J.; Herráez, A.; Farès, C.; et al. NMReDATA: Tools and Applications. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2021, 59, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fimognari, C.; Ferruzzi, L.; Turrini, E.; Carulli, G.; Lenzi, M.; Hrelia, P.; Cantelli-Forti, G. Metabolic and Toxicological Considerations of Botanicals in Anticancer Therapy. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2012, 8, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanzaro, E.; Greco, G.; Potenza, L.; Calcabrini, C.; Fimognari, C. Natural Products to Fight Cancer: A Focus on Juglans Regia. Toxins 2018, 10, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenzi, M.; Cocchi, V.; Novaković, A.; Karaman, M.; Sakač, M.; Mandić, A.; Pojić, M.; Barbalace, M.C.; Angeloni, C.; Hrelia, P.; et al. Meripilus Giganteus Ethanolic Extract Exhibits Pro-Apoptotic and Anti-Proliferative Effects in Leukemic Cell Lines. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zupkó, I.; Réthy, B.; Hohmann, J.; Molnár, J.; Ocsovszki, I.; Falkay, G. Antitumor Activity of Alkaloids Derived from Amaryllidaceae Species. In Vivo 2009, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Masi, M.; Di Lecce, R.; Mérindol, N.; Girard, M.-P.; Berthoux, L.; Desgagné-Penix, I.; Calabrò, V.; Evidente, A. Cytotoxicity and Antiviral Properties of Alkaloids Isolated from Pancratium Maritimum. Toxins 2022, 14, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, J.J.; Van Staden, J.; Bastida, J. Cytotoxic Alkaloid Constituents of the Amaryllidaceae. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Elsevier, 2016; Vol. 49, pp. 107–156 ISBN 978-0-444-63601-0.

- Nair, J.J.; Van Staden, J. Cytotoxic Tazettine Alkaloids of the Plant Family Amaryllidaceae. South Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 136, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahlíková, L.; Kawano, I.; Řezáčová, M.; Blunden, G.; Hulcová, D.; Havelek, R. The Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids Haemanthamine, Haemanthidine and Their Semisynthetic Derivatives as Potential Drugs. Phytochem. Rev. 2021, 20, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, J.; Nair, J.J.; Codina, C.; Bastida, J.; Pandey, S.; Gerasimoff, J.; Griffin, C. Selective Apoptosis-Inducing Activity of Crinum-Type Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 1068–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ločárek, M.; Nováková, J.; Klouček, P.; Hošt’álková, A.; Kokoška, L.; Gábrlová, L.; Šafratová, M.; Opletal, L.; Cahlíková, L. Antifungal and Antibacterial Activity of Extracts and Alkaloids of Selected Amaryllidaceae Species. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1934578X1501000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xia, B.; Wang, M.; Dong, Y.-F.; Feng, X. Two Novel Ceramides with a Phytosphingolipid and a Tertiary Amide Structure from Zephyranthes Candida. Lipids 2009, 44, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppo, E.; Marchese, A. Antibacterial Activity of Polyphenols. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2014, 15, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renault, J.-H.; Nuzillard, J.-M.; Maciuk, A.; Zeches-Hanrot, M. Use of Centrifugal Partition Chromatography for Purifying Galanthamine. 2009 U.S. Patent Application No. 11/722,004.

- Mandrone, M.; Bonvicini, F.; Lianza, M.; Sanna, C.; Maxia, A.; Gentilomi, G.A.; Poli, F. Sardinian Plants with Antimicrobial Potential. Biological Screening with Multivariate Data Treatment of Thirty-Six Extracts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 137, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Fraction | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| tazettine | A4 | [16] |

| albomaculine | A7 | [20] |

| haemanthamine | A9 | [21] |

| crinine | A11 | [22] |

| trisphaeridine | A2 | [23] |

| 3-epimacronine | A2 | [24] |

| 3-methoxy-8,9-methylenedioxy-3,4-dihydrophenanthridine | A2 | [25] |

| crinine acetate | A6 | [26] |

| 6α-hydroxybuphanisine | A8 | [27] |

| nerinine | A10 | [20] |

| β-pretazettine | A12_8 | [28] |

| α-pretazettine | A12_8 | [29] |

| 6-dehydroxy-6-acetamido-nerinine | A12_8 | - |

| Sample | IC50 24h |

IC50 48h |

IC50 72h |

|---|---|---|---|

| extract | 9.1 | 6.7 | 3.3 |

| A2 | 347.1 | 297.5 | 232.1 |

| A4 (tazettine) | 901.3 | 1171.0 | 869.2 |

| A6 | 394.0 | 419.0 | 412.9 |

| A7 (albomaculine) | 201.5 | 251.5 | 168.7 |

| A8 | 10.1 | 7.1 | 5.1 |

| A9 (haemanthamine) | 7.6 | 5.4 | 3.7 |

| A10 | 16.1 | 13.2 | 5.2 |

| A11 | 9.9 | 10.3 | 8.2 |

| A12 | 5.7 | 4.3 | 5.3 |

| A13 | 6.4 | 4.9 | 3.8 |

| Sample | IC50 24h |

IC50 48h |

IC50 72h |

|---|---|---|---|

| extract | 124.6 | 31.4 | 10.9 |

| A2 | 309.9 | 209.5 | 123.8 |

| A4 (tazettine) | 1373.0 | 857.8 | 881.9 |

| A6 | 894.8 | 360.7 | 256.1 |

| A7 (albomaculine) | 1669.0 | 1073.0 | 446.1 |

| A8 | 233.3 | 31.7 | 13.7 |

| A9 (haemanthamine) | 70.4 | 31.2 | 4.5 |

| A10 | 292.3 | 53.7 | 13.9 |

| A11 | 102.4 | 53.7 | 8.6 |

| A12 | 119.3 | 16.4 | 5.1 |

| A13 | 65.6 | 12.4 | 5.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).