Submitted:

08 May 2023

Posted:

09 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology for Literature Search and Study Selection

3. Phytochemicals (PHYs)

3.1. Phytochemicals and Nutraceuticals: Not Quite the Same

3.2. Phytochemicals: An Overview

3.2.1. Specific Sources and Benefits of Main Types of PHYs

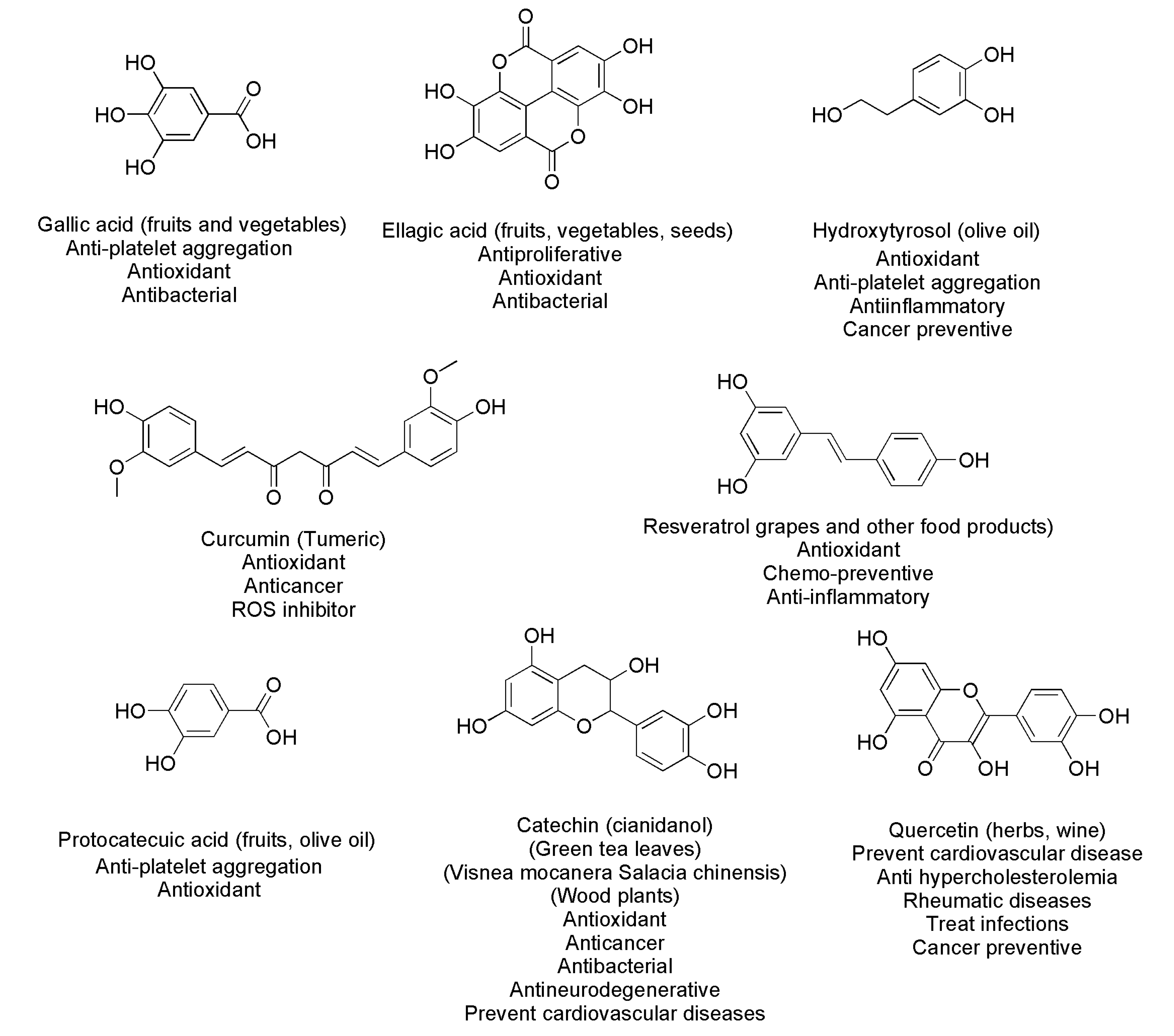

Polyphenols

Tannins

Lutein and Zeaxanthin

Sulforaphane

Eugenol

Terpenoids

3.2.2. Let's Eat in Colors!

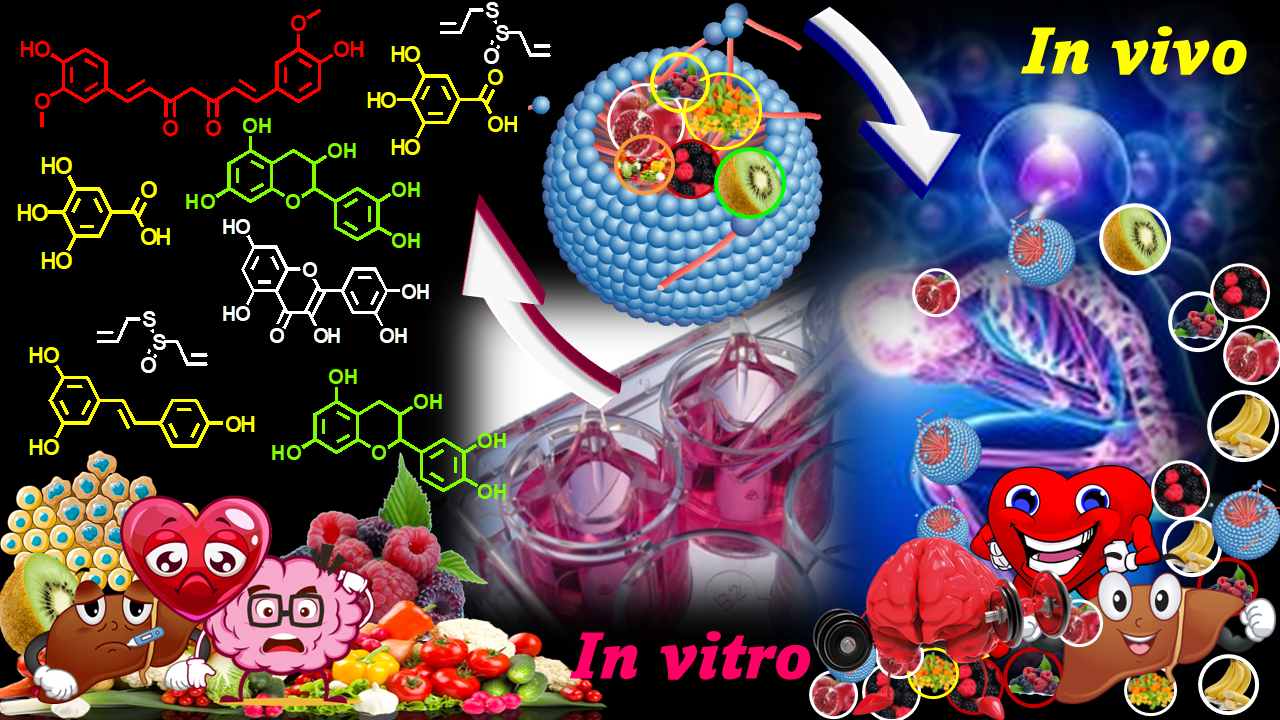

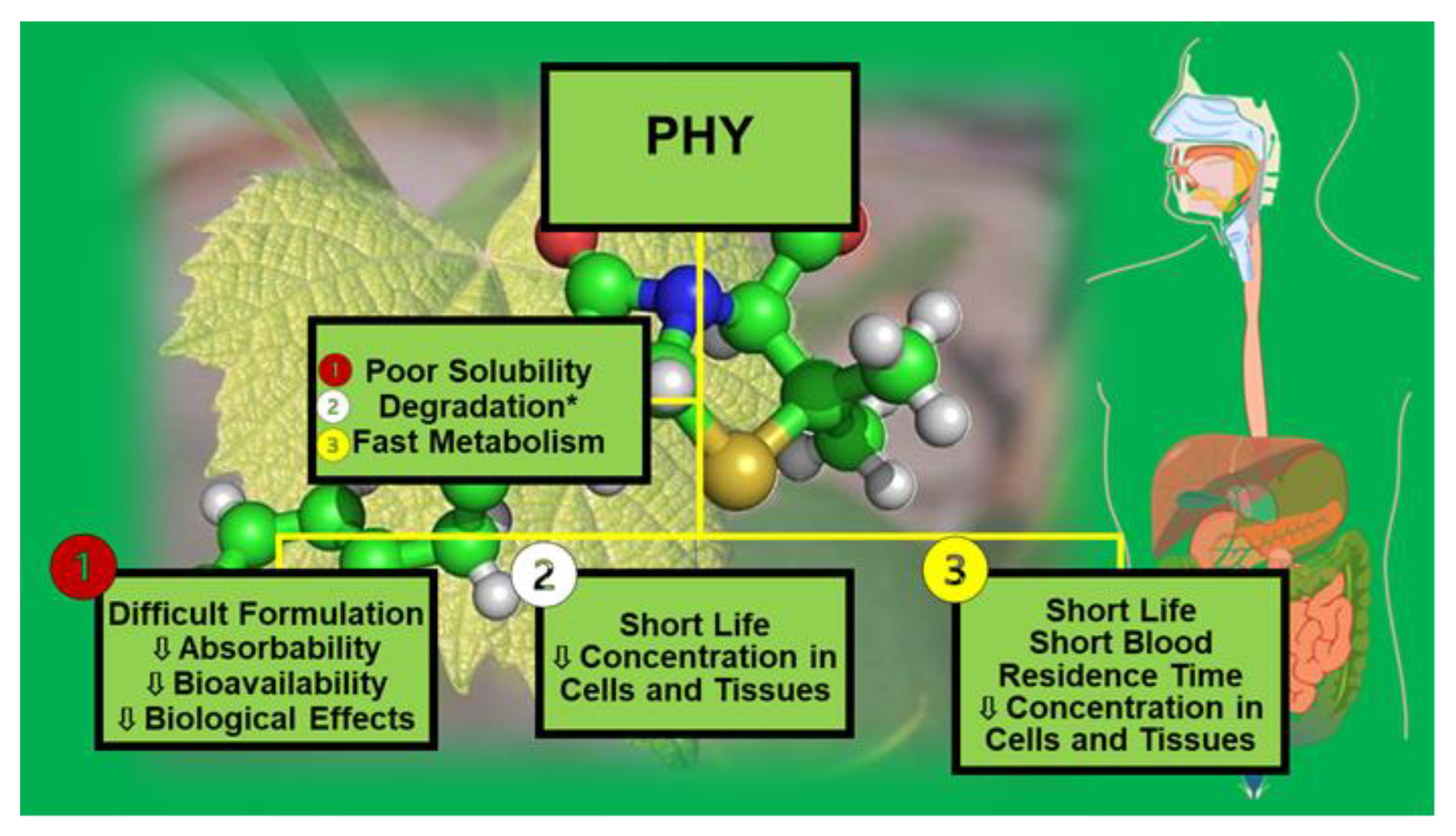

3.2.3. Phytochemicals: A Plethora of Benefits in Vitro Against Poor Findings in Vivo

3.2.4. Improving Solubility of Bioactive Compounds

Particle Engineering Techniques (PETs)

Formulation Approaches (FAs)

4. Nanotechnology

4.1. Advantages of Nanotechnology Application

4.2. Nanosuspension and Nanoemulsion Approaches

4.2.1. Nanosuspension Techniques

Nano-suspensions-based Phytochemicals Delivery Systems

4.2.2. Emulsion-Based Techniques

High Energy and Low Energy Methods

Novel Nano-emulsion Preparation Techniques

NE-based Phytochemicals Delivery Systems

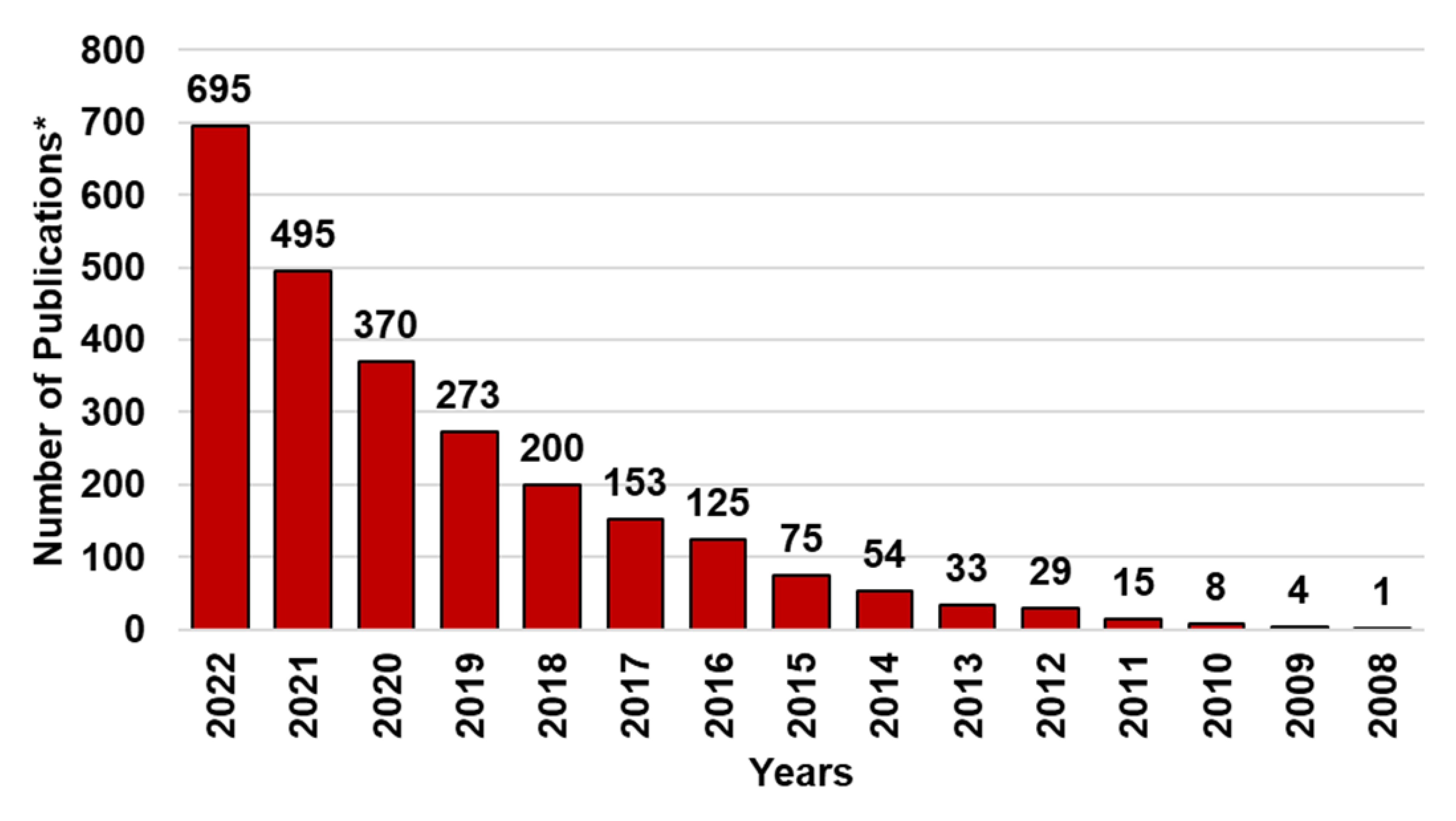

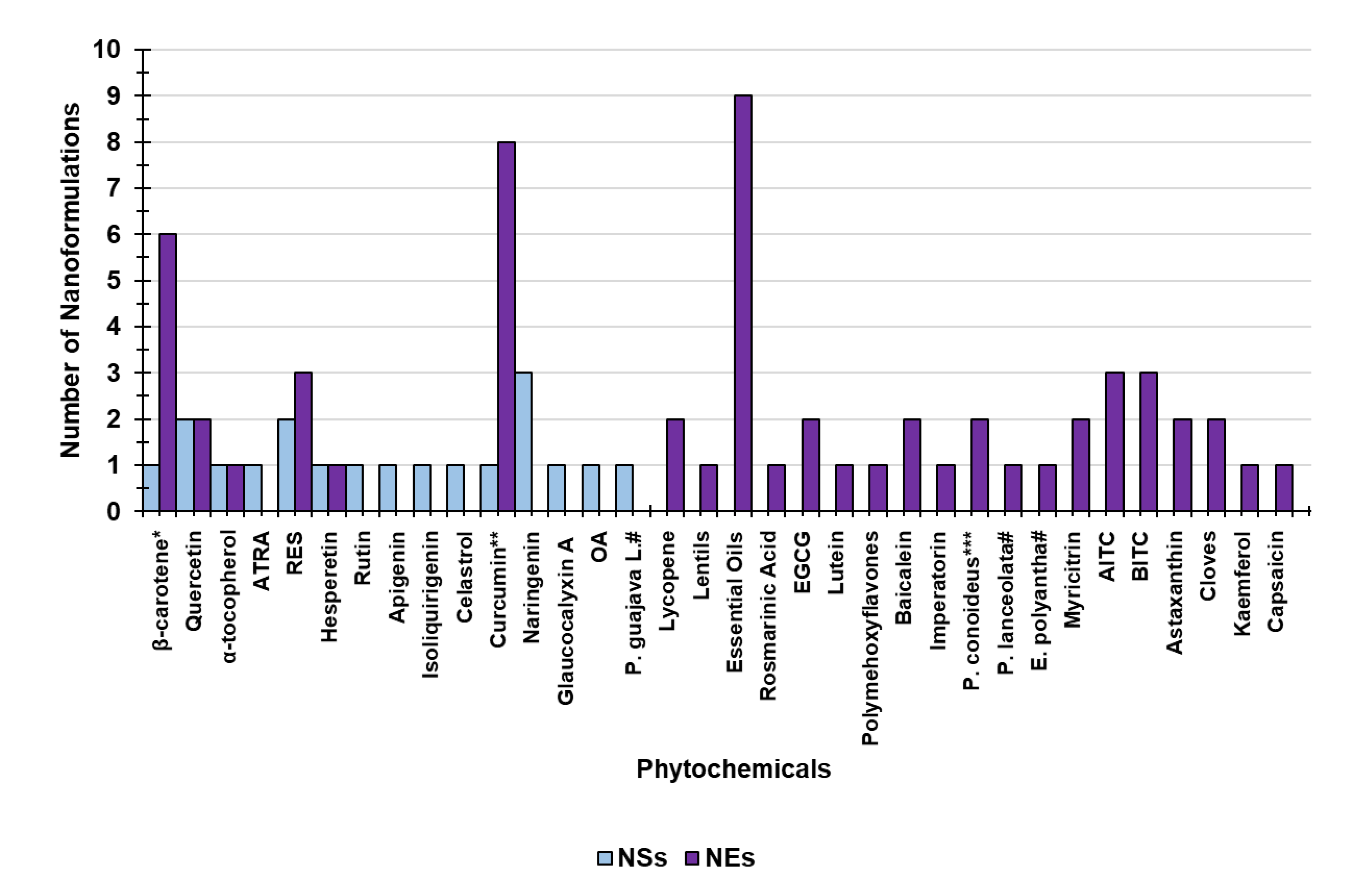

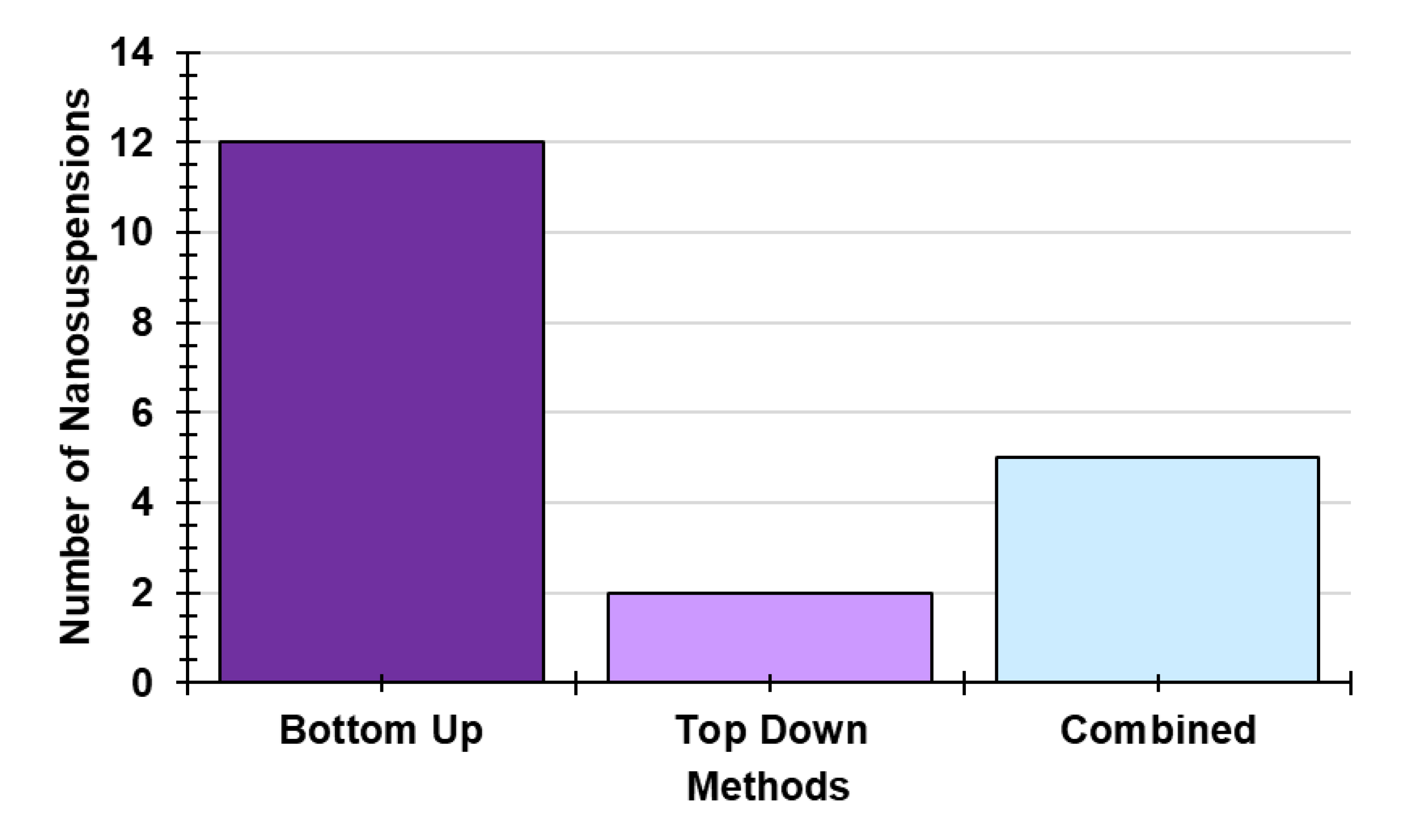

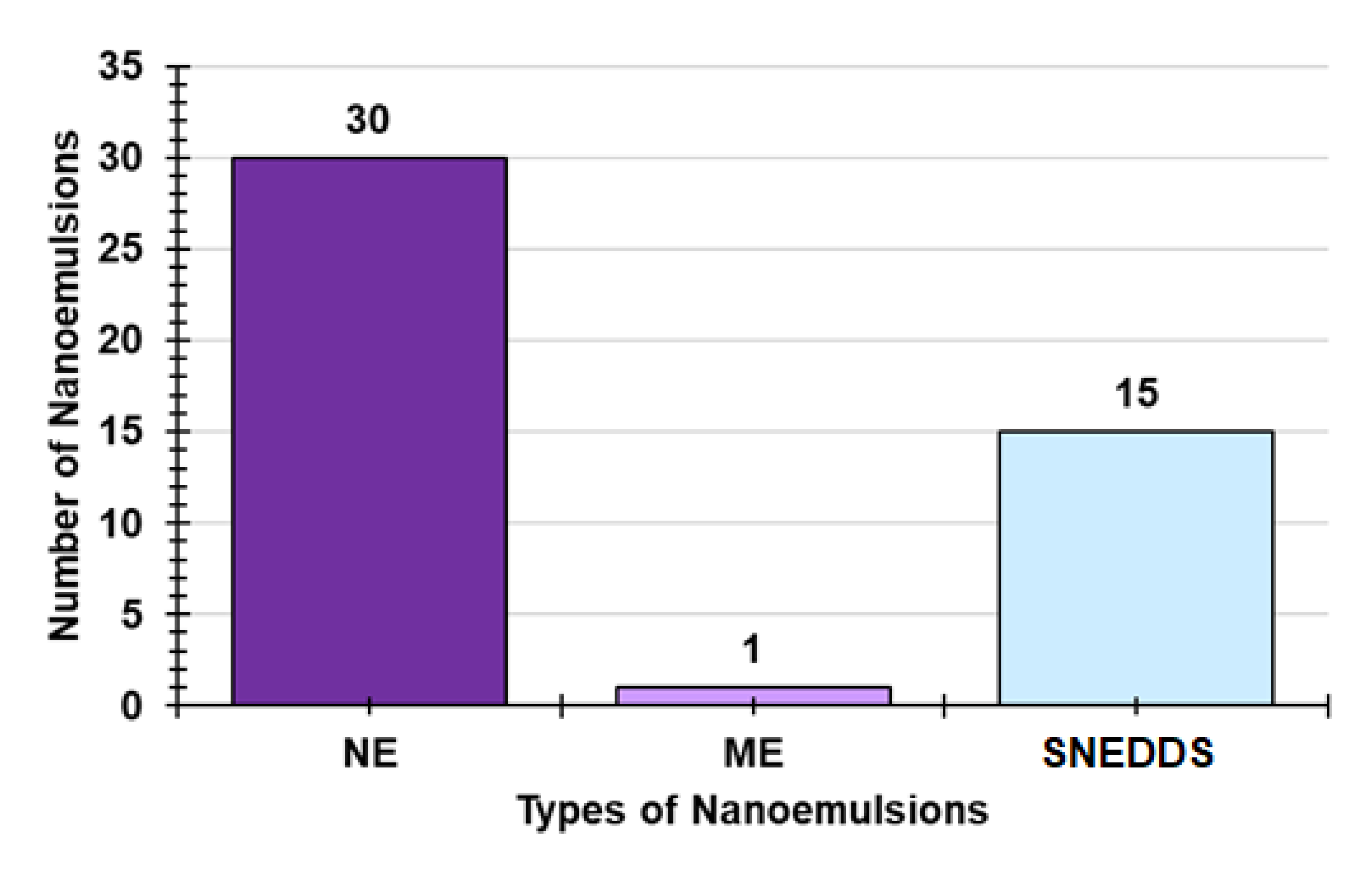

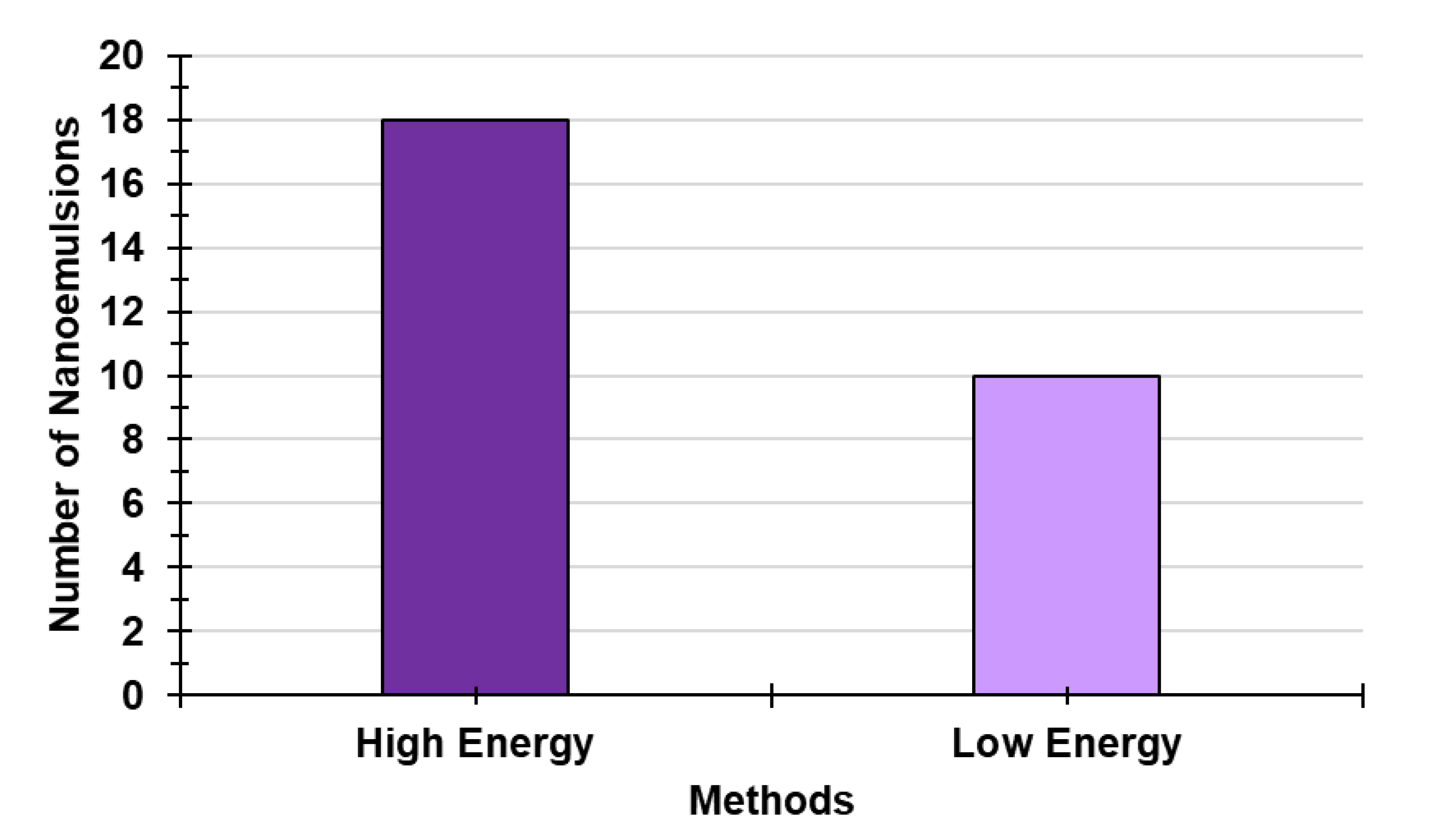

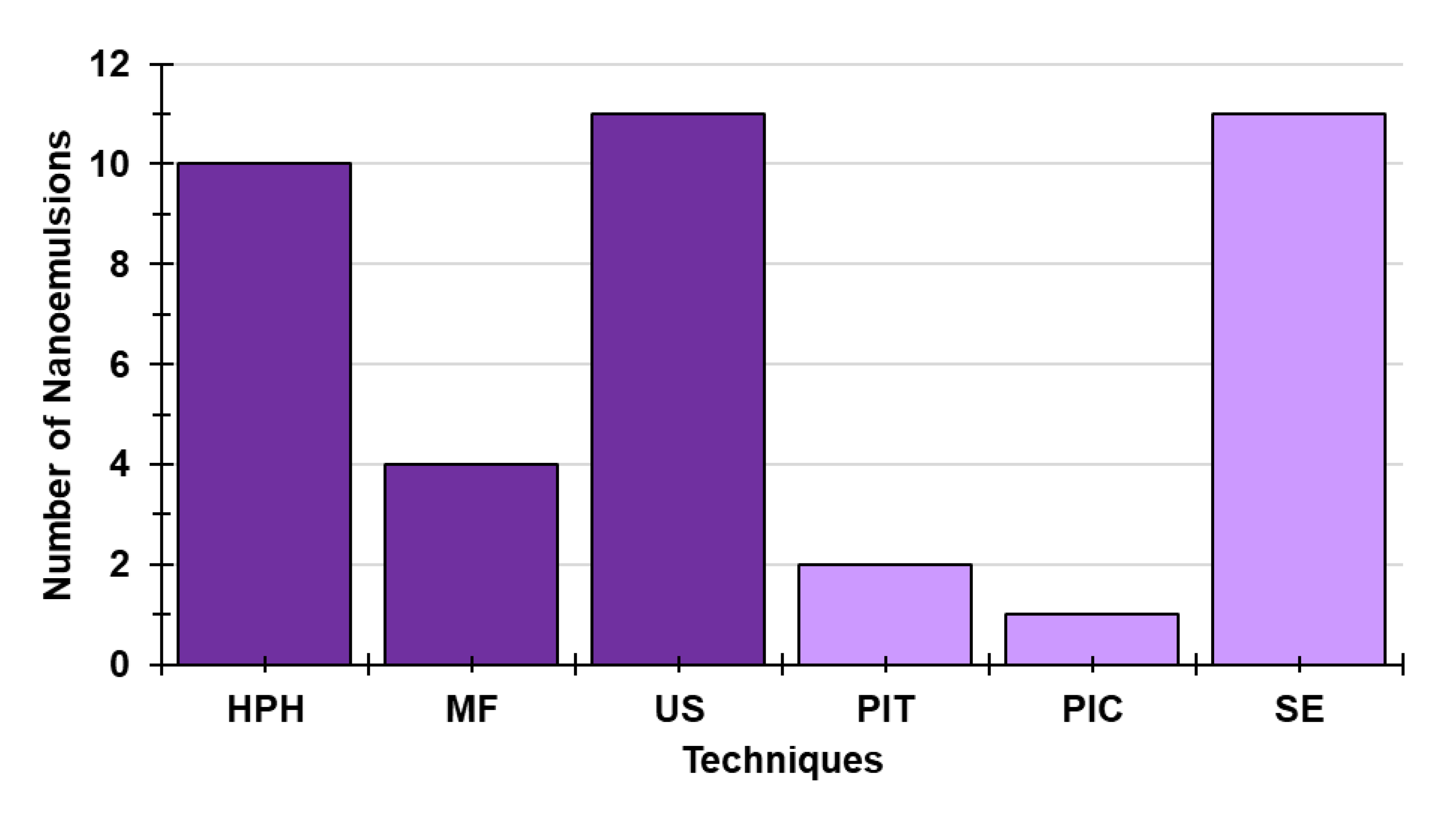

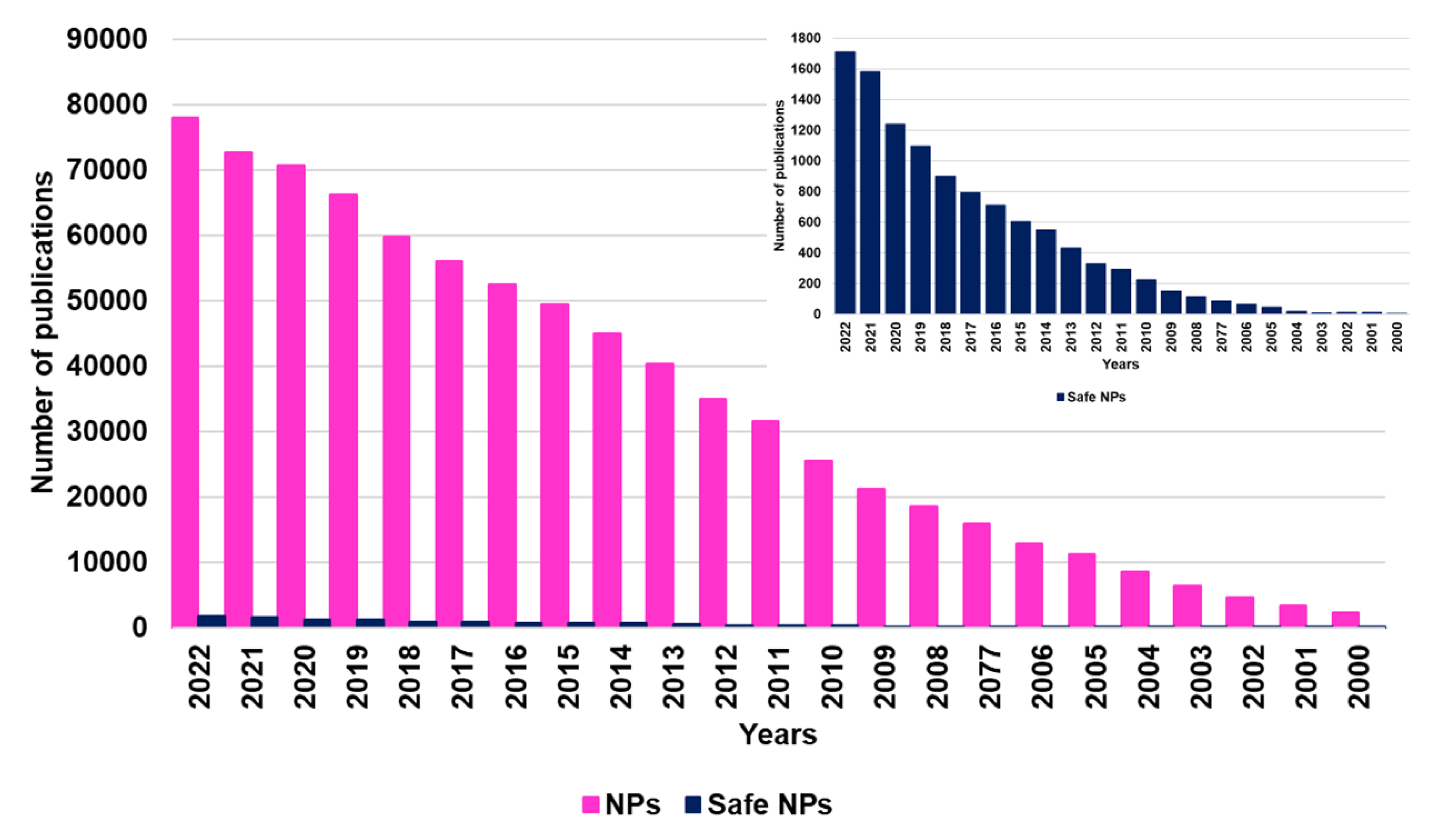

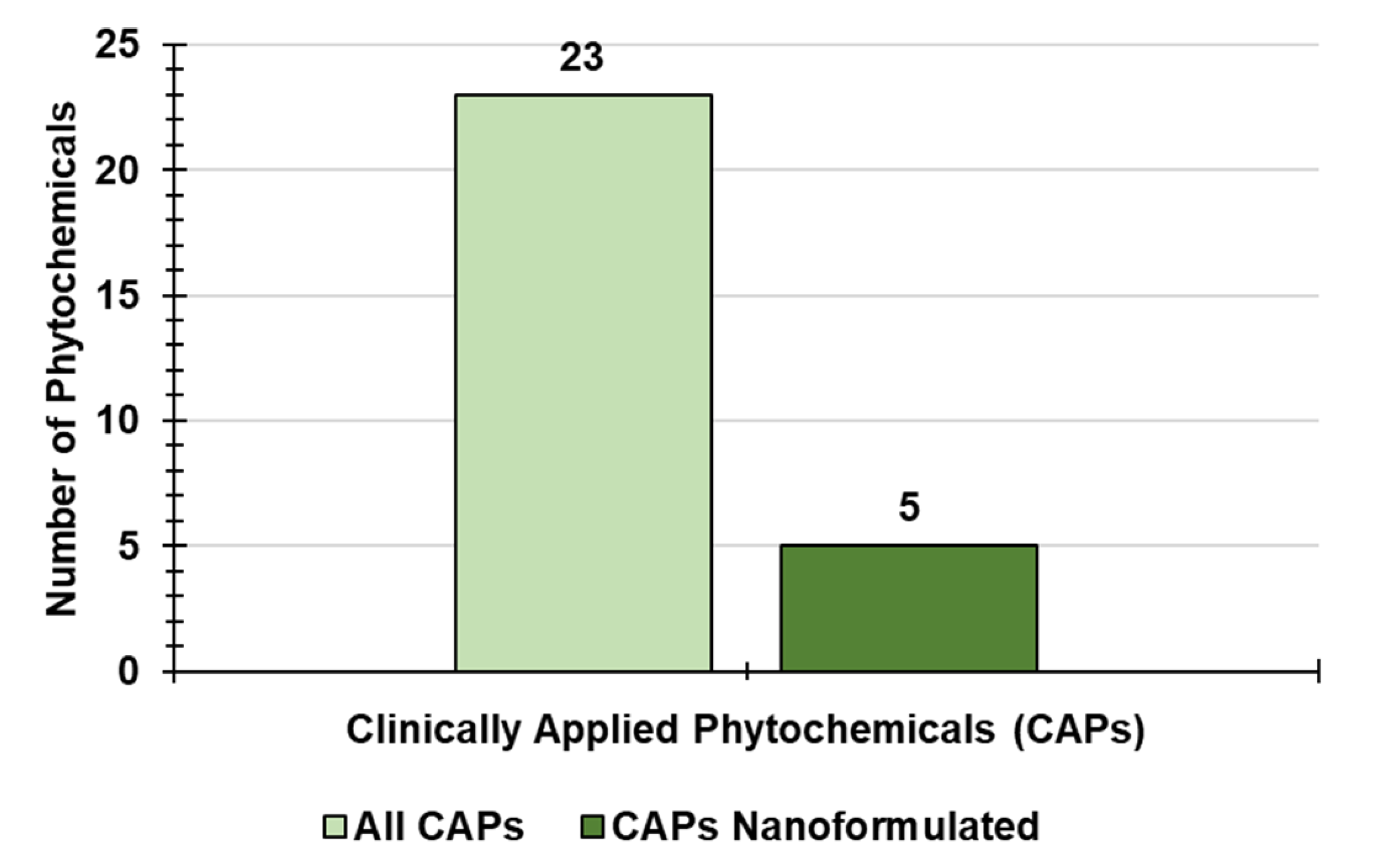

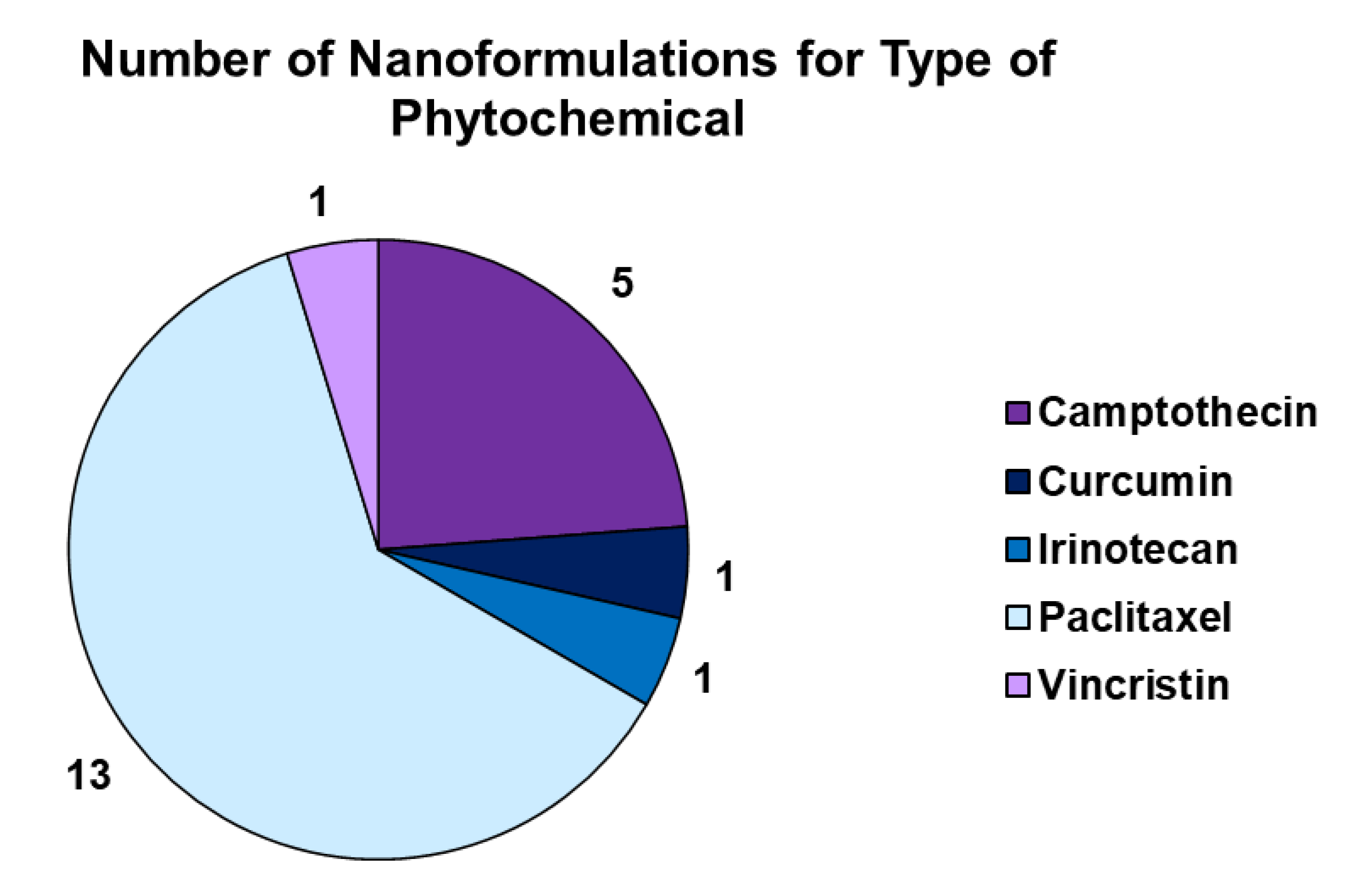

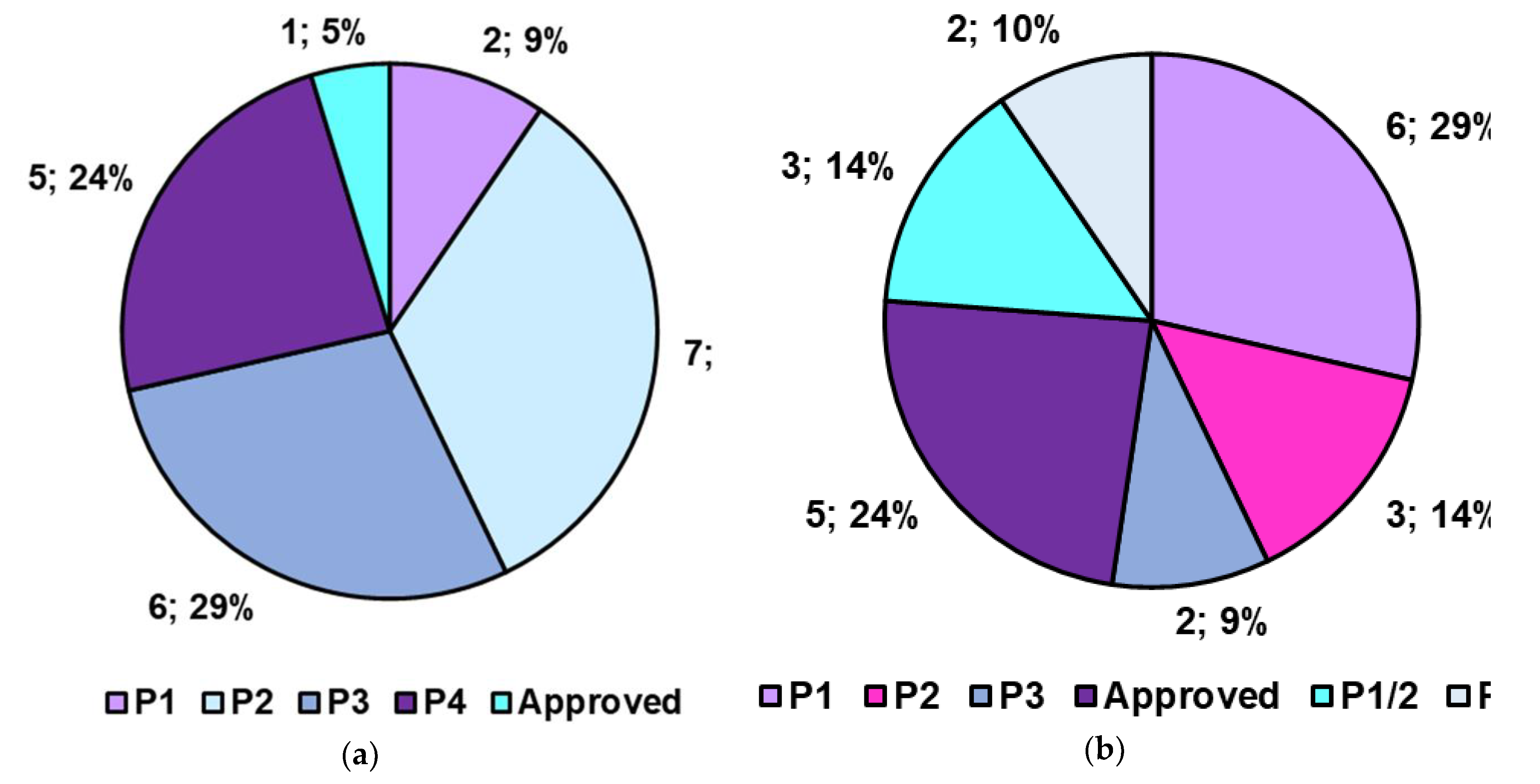

NSs- and NEs-based Phytochemicals Formulations: The State of The Art in Graphs

5. Nanomaterials and Nanoparticles: What We Know and What We Should Know

5.1. Ongoing Actions to Address Challenges Related to Nanotechnology

5.2. Providing Nanotechnology Guidance and Information

5.2.1. Safety of Nanocarriers

Titanium Dioxide: The European Case

5.2.2. Strategies to Reduce the Toxicity of Nanoparticles

6. Phytochemicals-Loaded Nanomedicines: Where Are We and Where Are We Going?

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfei, S.; Schito, A.M.; Zuccari, G. Nanotechnological Manipulation of Nutraceuticals and Phytochemicals for Healthy Purposes: Established Advantages vs. Still Undefined Risks. Polymers 2021, 13, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Garcia, S.N.; Vazquez-Cruz, M.A.; Garcia-Mier, L.; Contreras-Medina, L.M.; Guevara-González, R.G.; Garcia-Trejo, J.F.; Feregrino-Perez, A.A. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Properties of Secondary Metabolites in Berries. Therapeutic Foods 2018, 397–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phytochemical. Available online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phytochemical. Accessed on 06 April 2023.

- Higdon, J.; Drake, V.J. Evidence-Based Approach to Phytochemicals and Other Dietary Factors; Thieme, 2012; ISBN 978-3-13-169712-7.

- Rutz, A.; Sorokina, M.; Galgonek, J.; Mietchen, D.; Willighagen, E.; Gaudry, A.; Graham, J.G.; Stephan, R.; Page, R.; Vondrášek, J.; et al. The LOTUS Initiative for Open Knowledge Management in Natural Products Research. eLife 2022, 11, e70780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Gouvinhas, I.; Rocha, J; et al. Phytochemical and antioxidant analysis of medicinal and food plants towards bioactive food and pharmaceutical resources. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BenSaad, L.A.; Kim, K.H.; Quah, C.C.; Kim, W.R.; Shahimi, M. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Ellagic Acid, Gallic Acid and Punicalagin A&B Isolated from Punica Granatum. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2017, 17, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.-S.; Yang, S.-F.; Sethi, G.; Hu, D.-N. Natural Bioactives in Cancer Treatment and Prevention. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015, 182835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imm, B.-Y.; Kim, C.H.; Imm, J.-Y. Effects of Partial Substitution of Lean Meat with Pork Backfat or Canola Oil on Sensory Properties of Korean Traditional Meat Patties (Tteokgalbi). Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2014, 34, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisio, A.; Milella, L.; Parricchi, A.; Alfei, S.; Vignola, L.; De Mieri, M.; Schito, A.; Hamburger, M.; De Tommasi, N. Biological activity of constituents of Salvia chamaedryoides. Plant. Med. 2016, 81, S1–S381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisio, A.; De Mieri, M.; Milella, L.; Schito, A.M.; Parricchi, A.; Russo, D.; Alfei, S.; Lapillo, M.; Tuccinardi, T.; Hamburger, M.; et al. Antibacterial and Hypoglycemic Diterpenoids from Salvia chamaedryoides. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Ho, C.-T.; Huang, Q. Common delivery systems for enhancing in vivo bioavailability and biological efficacy of nutraceuticals. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 7, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Cao, Y.; Huang, Q. Edible Nanoencapsulation Vehicles for Oral Delivery of Phytochemicals: A Perspective Paper. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 6727–6735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccari, G.; Alfei, S.; Zorzoli, A.; Marimpietri, D.; Turrini, F.; Baldassari, S.; Marchitto, L.; Caviglioli, G. Increased Water-Solubility and Maintained Antioxidant Power of Resveratrol by Its Encapsulation in Vitamin E TPGS Micelles: A Potential Nutritional Supplement for Chronic Liver Disease. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S. Nanotechnology Applications to Improve Solubility of Bioactive Constituents of Foods for Health-Promoting Purposes. In Nanofood Engineering, 1st ed.; Hebbar, U., Ranjan, S., Dasgupta, N., Mishra, R.K., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 189–258. [Google Scholar]

- Phytonutrients: What Are They & Why Are They Important? . Available online at Phytonutrients: What Are They & Why Are They Important? - Cancer Nutrition Consortium. Accessed on 27 April 2023.

- Liu, R.H. Health-promoting components of fruits and vegetables in the diet. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.) 2013, 4, 384S–92S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westergaard, D.; Li, J.; Jensen, K.; Kouskoumvekaki, I.; Panagiotou, G. Exploring Mechanisms of Diet-Colon Cancer Associations through Candidate Molecular Interaction Networks. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, M.; Pellegrini, N.; Fogliano, V. The effect of cooking on the phytochemical content of vegetables. Journal of the science of food and agriculture 2014, 94, 1057–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budisan, L.; Gulei, D.; Zanoaga, O.M.; Irimie, A.I.; Sergiu, C.; Braicu, C.; Gherman, C.D. Berindan-Neagoe, I. Dietary Intervention by Phytochemicals and Their Role in Modulating Coding and Non-Coding Genes in Cancer. International journal of molecular sciences 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, H.E.; Azlan, A.; Tang, S.T.; Lim, S.M. Anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: colored pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients, and the potential health benefits. Food & nutrition research 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Blumberg, J.B. Phytochemical composition of nuts. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition 2008, 17 Suppl 1, 329–332. [Google Scholar]

- Peluso, I.; Serafini, M. Antioxidants from black and green tea: from dietary modulation of oxidative stress to pharmacological mechanisms. British journal of pharmacology 2017, 174, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrone, T.; Russo, M.A.; Jirillo, E. Cocoa and Dark Chocolate Polyphenols: From Biology to Clinical Applications. Frontiers in immunology 2017, 8, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tümen, İ.; Akkol, E.K.; Taştan, H.; Süntar, I.; Kurtca, M. Research on the antioxidant, wound healing, and anti-inflammatory activities and the phytochemical composition of maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Ait). Journal of ethnopharmacology 2018, 211, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saab, A.M.; Gambari, R.; Sacchetti, G.; Guerrini, A.; Lampronti, I.; Tacchini, M.; El Samrani, A.; Medawar, S.; Makhlouf, H.; Tannoury, M.; Abboud, J.; Diab-Assaf, M.; Kijjoa, A.; Tundis, R.; Aoun, J.; Efferth, T. Phytochemical and pharmacological properties of essential oils from Cedrus species. Natural product research 2018, 32, 1415–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malcolm, B.J.; Tallian, K. Essential oil of lavender in anxiety disorders: Ready for prime time? The mental health clinician 2018, 7, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, C.; Prakash, D. Phytonutrients as therapeutic agents. Journal of complementary & integrative medicine 2014, 11, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S.; Dixit, M. Role of Polyphenols and Other Phytochemicals on Molecular Signaling. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2015, 504253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Xing, H.; Ye, J. Efficacy of berberine in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism: clinical and experimental 2008, 57, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Spagnuolo, C.; Tedesco, I.; Russo, G.L. Phytochemicals in cancer prevention and therapy: truth or dare? Toxins 2010, 2, 517–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Tian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Si, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, D. Recent progress in the antiviral activity and mechanism study of pentacyclic triterpenoids and their derivatives. Medicinal research reviews 2018, 38, 951–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, R.; Coppo, E.; Marchese, A.; Daglia, M.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Nabavi, S.F.; Nabavi, S.M. Phytochemicals for human disease: An update on plant-derived compounds antibacterial activity. Microbiological research 2017, 196, 44–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Hassan, S.S.; Azim, S. A Therapeutic Connection between Dietary Phytochemicals and ATP Synthase. Current medicinal chemistry 2017, 24, 3894–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, M.; Peluso, I. Functional Foods for Health: The Interrelated Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Role of Fruits, Vegetables, Herbs, Spices and Cocoa in Humans. Current pharmaceutical design 2016, 22, 6701–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F.; Du, B.; Xu, B. Anti-inflammatory effects of phytochemicals from fruits, vegetables, and food legumes: A review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2018, 58, 1260–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lushchak, V.I. Glutathione homeostasis and functions: potential targets for medical interventions. Journal of amino acids, 7368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianbo, X.; Bai, W. Bioactive phytochemicals. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2019, 59(6), 827–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, B. Functional and Preservative Properties of Phytochemicals; Elsevier Science & Technology, 2020; ISBN 978-0-12-818593-3.

- Food Source of Carotenoids and Why they are so Important. Available online at https://nutritionyoucanuse.com/food-sources-of-carotenoids. Accessed on 28 April 2023.

- List of phytochemicals in food. Available online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_phytochemicals_in_food. Accessed on 28 April 2023.

- A list of food high in phytosterols. Available online at https://lazyplant.com/foods-with-phytosterols/. Accessed on 28 April 2023.

- Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.P. , López-Martínez, L.X., Contreras-Angulo, L.A., Elizalde-Romero, C.A., Heredia, J.B. (2020). Plant Alkaloids: Structures and Bioactive Properties. In: Swamy, M. (eds) Plant-derived Bioactives. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Perles, R.; Abellán, Á.; León, D.; Ferreres, F.; Guy, A.; Oger, C.; Galano, J.M.; Durand, T.; Gil-Izquierdo, Á. Sorting out the phytoprostane and phytofuran profile in vegetable oils. Food research international (Ottawa, Ont.), 2018, 107, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Which foods are high in fiber? Available online at https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/high-fiber-foods-chart#food-chart. Accessed on 28 April 2023.

- Ulanowska, M.; Olas, B. Biological Properties and Prospects for the Application of Eugenol—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hseu, Y.-C.; Chou, C.-W.; Kumar, K.S.; Fu, K.-T.; Wang, H.-M.; Hsu, L.-S.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Wu, C.-R.; Chen, S.-C.; Yang, H.-L. Ellagic acid protects human keratinocyte (HaCaT) cells against UVA-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis through the upregulation of the HO-1 and Nrf-2 antioxidant genes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V, A.; Kp, M. Ellagic Acid as a Potential Anti-Cancer Drug. Int. J. Radiol. Radiat. Ther. 2017, 3, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrosa, M.; Conesa, M.T.G.; Espín, J.C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Ellagitannins, ellagic acid and vascular health. Mol. Asp. Med. 2010, 31, 513–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, K.H.; Dianat, M.; Sarkaki, A. Ellagic acid improves electrocardiogram waves and blood pressure against global cerebral ischemia rat experimental models. Electron. Phys. 2015, 7, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Hoseinynejad, K.; Gharib-Naseri, M.K.; Sarkaki, A.; Dianat, M.; Badavi, M.; Farbood, Y. Effects of ellagic acid pretreatment on renal functions disturbances induced by global cerebral ischemic-reperfusion in rat. Iran J. Basic Med. Sci. 2017, 20, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Firdaus, F.; Zafeer, M.F.; Waseem, M.; Anis, E.; Hossain, M.M.; Afzal, M. Ellagic acid mitigates arsenic-trioxide-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cytotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2018, 32, e22024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakuradze, T.; Tausend, A.; Galan, J.; Groh, I.A.M.; Berry, D.; Tur, J.A.; Marko, D.; Richling, E. Antioxidative activity and health benefits of anthocyanin-rich fruit juice in healthy volunteers. Free radical research 2019, 53, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Q.; Chu, M.; Yu, X.; Xie, Y.; Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.-F.; Shi, J.; Yan, N. Anthocyanins and Proanthocyanidins: Chemical Structures, Food Sources, Bioactivities, and Product Development. Food Reviews International 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboonabi, A.; Aboonabi, A. Anthocyanins reduce inflammation and improve glucose and lipid metabolism associated with inhibiting nuclear factor-kappaB activation and increasing PPAR-γ gene expression in metabolic syndrome subjects. Free radical biology & medicine 2020, 150, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhao, G.; Hu, T.; Wang, Y. Potential and Challenges of Tannins as an Alternative to In-Feed Antibiotics for Farm Animal Production. Animal Nutrition 2018, 4, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeriglio, A.; Barreca, D.; Bellocco, E.; Trombetta, D. Proanthocyanidins and Hydrolysable Tannins: Occurrence, Dietary Intake and Pharmacological Effects. British Journal of Pharmacology 2017, 174, 1244–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrowicka, M.; Mrowicki, J.; Kucharska, E.; Majsterek, I. Lutein and Zeaxanthin and Their Roles in Age-Related Macular Degeneration—Neurodegenerative Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga, K.E.; Bishop, N.J.; Turner, A.S. Dietary Lutein and Zeaxanthin Are Associated with Working Memory in an Older Population. Public Health Nutrition 2021, 24, 1708–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthline. Nutrition. Lutein and Zeaxanthin: Benefits, Dosage and Food Sources. Available online at . Accessed on 06 April 2023.

- Healthline. Nutrition. Sulforaphane: Benefits, Dosage and Food Sources. Available online at https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/sulforaphane. Accessed on 06 April 2023.

- Barboza, J.N.; da Silva Maia Bezerra Filho, C.; Silva, R.O.; Medeiros, J.V.R.; de Sousa, D.P. An Overview on the Anti-inflammatory Potential and Antioxidant Profile of Eugenol. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer-Young, E.C.; Calhoun, A.C.; Mirzayeva, A.; Sadd, B.M. Effects of the Floral Phytochemical Eugenol on Parasite Evolution and Bumble Bee Infection and Preference. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, M.F.; Khadim, M.; Rafiq, M.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Wan, C.C. Pharmacological Properties and Health Benefits of Eugenol: A Comprehensive Review. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2021, 2021, 2497354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minich, D.M. A Review of the Science of Colorful, Plant-Based Food and Practical Strategies for "Eating the Rainbow". J. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 2, 2125070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricardo Lagoa, João Silva, Joaquim Rui Rodrigues, Anupam Bishayee, Advances in phytochemical delivery systems for improved anticancer activity, Biotechnology Advances, Volume 38, 2020, 107382. [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, M.; Tang, S.Y.; Tan, K.W. Cavitation technology–A greener processing technique for the generation of pharmaceutical nanoemulsions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014, 21, 2069–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Su, R.; Nie, S.; Sun, M.; Zhang, J.; Wu, D.; Moustaid-Moussa, N. Application of nanotechnology in improving bioavailability and bioactivity of diet-derived phytochemicals. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S. , Taptue, G.B., Catena, S. et al. Synthesis of Water-soluble, Polyester-based Dendrimer Prodrugs for Exploiting Therapeutic Properties of Two Triterpenoid Acids. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2018, 36, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schito, A.M.; Schito, G.C.; Alfei, S. Synthesis and Antibacterial Activity of Cationic Amino Acid-Conjugated Dendrimers Loaded with a Mixture of Two Triterpenoid Acids. Polymers 2021, 13, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Schito, A.M.; Zuccari, G. Considerable Improvement of Ursolic Acid Water Solubility by Its Encapsulation in Dendrimer Nanoparticles: Design, Synthesis and Physicochemical Characterization. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schito, A.M.; Caviglia, D.; Piatti, G.; Zorzoli, A.; Marimpietri, D.; Zuccari, G.; Schito, G.C.; Alfei, S. Efficacy of Ursolic Acid-Enriched Water-Soluble and Not Cytotoxic Nanoparticles against Enterococci. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, B.B.; Aloorkar, N.H.; Deshmukh, S.M.; Sulake, S.P.; Humbe, P.V.; Mane, P.P. Recent advancements in particle engi-neering techniques for pharmaceutical applications. Indo. Am. J. Pharm. Res. 2014, 4, 2027–2049. [Google Scholar]

- Koshy, P.; Pacharane, S.; Chaudhry, A.; Jadhav, K.; Kadam, V. Drug particle engineering of poorly water-soluble drugs. Der. Pharm. Lett. 2010, 2, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, J.O.; Watts, A.B.; McConville, J.T. Mechanical particle-size reduction techniques. In Formulating Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs; Williams, R.O., III, Watts, A.B., Miller, D.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 133–170. ISBN 9781461411444. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Owens, D.E.; Williams, R.O. Pharmaceutical Cryogenic Technologies. In: Williams III, R., Watts, A., Miller, D. (eds) Formulating Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. AAPS Advances in the Pharmaceutical Sciences Series, vol 3. Springer, New York, NY., pp. 443–500. [CrossRef]

- Zuccari, G.; Baldassari, S.; Ailuno, G.; Turrini, F.; Alfei, S.; Caviglioli, G. Formulation Strategies to Improve Oral Bioavailability of Ellagic Acid. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avachat, A.M.; Patel, V.G. Self nanoemulsifying drug delivery system of stabilized ellagic acid–phospholipid complex with improved dissolution and permeability. Saudi Pharm. J. 2015, 23, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrigal-Carballo, S.; Lim, S.; Rodriguez, G.; Vila, A.O.; Krueger, C.G.; Gunasekaran, S.; Reed, J.D. Biopolymer coating of soybean lecithin liposomes via layer-by-layer self-assembly as novel delivery system for ellagic acid. J. Funct. Foods 2010, 2, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour, H.; Hamishehkar, H.; Rahmati-yamchi, M.; Shanehbandi, D.; Nazari Soltan Ahmad, S.; Hasani, A. Enhanced Anti-Cancer Capability of Ellagic Acid Using Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs). International Journal of Cancer Management 2018, 11, e9402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulani, V.D.; Kothavade, P.S.; Kundaikar, H.; Gawali, N.B.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Degani, M.S.; Juvekar, A.R. Inclusion complex of ellagic acid with β-cyclodextrin: Characterization and in vitro anti-inflammatory evaluation. J. Mol. Struct. 2016, 1105, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mady, F.; Ibrahim, S.R.-M. Cyclodextrin-based nanosponge for improvement of solubility and oral bioavailability of Ellagic acid. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 31, 2069–2076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Turrini, F.; Catena, S.; Zunin, P.; Parodi, B.; Zuccari, G.; Pittaluga, A.M.; Boggia, R. Preparation of ellagic acid micro and nano formulations with amazingly increased water solubility by its entrapment in pectin or non-PAMAM dendrimers suitable for clinical applications. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 2438–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, K.; Liu, B.; Feng, S.-S. A strategy for precision engineering of nanoparticles of biodegradable copolymers for quantitative control of targeted drug delivery. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 9145–9155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, X.; Guo, J.; Chen, Y.; Fang, X. Effect of phospholipid composition on pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of epirubicin liposomes. J. Liposome Res. 2011, 22, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, A.; Angelov, B.; Drechsler, M.; Lesieur, S. Neurotrophin delivery using nanotechnology. Drug Discov. Today 2013, 18, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.S.; Koo, S.Y.; Choi, K.Y. Emerging Nanoformulation Strategies for Phytocompounds and Applications from Drug Delivery to Phototherapy to Imaging. Bioactive Materials 2022, 14, 182–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhao, X.; Fu, Y. Preparation, Characterization and Antitumor Activity Evaluation of Apigenin Nanoparticles by the Liquid Antisolvent Precipitation Technique. Drug Delivery 2017, 24, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Shaal, L.; Müller, R.H.; Shegokar, R. SmartCrystal Combination Technology–Scale up from Lab to Pilot Scale and Long Term Stability. Die Pharm. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 65, 877–884. [Google Scholar]

- De Paz, E. ; Martín, Á; Estrella, A.; Rodríguez-Rojo, S.; Matias, A.A.; Duarte, C.M.; Cocero, M.J. Formulation of β-carotene by precipitation from pressurized ethyl acetate-on-water emulsions for application as natural colorant. Food Hydrocoll.

- Lai, F.; Franceschini, I.; Corrias, F.; Sala, M.C.; Cilurzo, F.; Sinico, C.; Pini, E. Maltodextrin Fast Dissolving Films for Quercetin Nanocrystal Delivery. A Feasibility Study. Carbohydrate Polymers 2015, 121, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karadag, A.; Ozcelik, B.; Huang, Q. Quercetin Nanosuspensions Produced by High-Pressure Homogenization. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 1852–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campardelli, R.; Reverchon, E. α-Tocopherol nanosuspensions produced using a supercritical assisted process. J. Food Eng. 2015, 149, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xia, Q.; Gu, N. Preparation of All-Trans Retinoic Acid Nanosuspensions Using a Modified Precipitation Method. Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy 2006, 32, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, B.; Müller, R.H.; Möschwitzer, J.P. Precipitation followed by high pressure homogenization as a combinative approach to prepare drug nanocrystals. In Tag der Pharmazie; Abstract V2, Booklet Page 6; FU Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, F.Z. , Yue; Mai, Yaping; Guo, Jueshuo; Dong, Luning; Zhang, Wannian; Yang, Jianhong Isoliquiritigenin Nanosuspension Enhances Cytostatic Effects in A549 Lung Cancer Cells. Planta Med 2020, 86, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Ao, H.; Guo, Y.; Han, M.; Wang, X. Preparation of High Drug-Loading Celastrol Nanosuspensions and Their Anti-Breast Cancer Activities in Vitro and in Vivo. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 8851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momenkiaei, F.; Raofie, F. Preparation of Curcuma Longa L. Extract Nanoparticles Using Supercritical Solution Expansion. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2019, 108, 1581–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gera, S.; Talluri, S.; Rangaraj, N.; Sampathi, S. Formulation and Evaluation of Naringenin Nanosuspensions for Bioavailability Enhancement. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017, 18, 3151–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Pooja, D.; Ravuri, H.G.; Gunukula, A.; Kulhari, H.; Sistla, R. Fabrication of Surfactant-Stabilized Nanosuspension of Naringenin to Surpass Its Poor Physiochemical Properties and Low Oral Bioavailability. Phytomedicine 2018, 40, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajamani, S.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Sengodan, T.; Thangavelu, S. Augmented Anticancer Activity of Naringenin-Loaded TPGS Polymeric Nanosuspension for Drug Resistive MCF-7 Human Breast Cancer Cells. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2018, 44, 1752–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Li, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X. A Nanoparticulate Drug-Delivery System for Glaucocalyxin A: Formulation, Characterization, Increased in Vitro, and Vivo Antitumor Activity. Drug Delivery 2016, 23, 2457–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Das, S.; Ng, K.; Heng, P.W.S. Formulation, Biological and Pharmacokinetic Studies of Sucrose Ester-Stabilized Nanosuspensions of Oleanolic Acid. Pharmaceutical Research 2011, 28, 2020–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaur, P.K. Nanosuspension of Flavonoid-Rich Fraction from Psidium Guajava Linn for Improved Type 2-Diabetes Potential. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2021, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Hussain, F.; Naeem, M.; Khan, A.; Al-Harrasi, A. Nanotechnology Approach for Exploring the Enhanced Bioactivities and Biochemical Characterization of Freshly Prepared Nigella Sativa L. Nanosuspensions and Their Phytochemical Profile. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. M, S.; Naveen, N.R.; Rao, G.S.N.K.; Gopan, G.; Chopra, H.; Park, M.N.; Alshahrani, M.M.; Jose, J.; Emran, T.B.; Kim, B. A Spotlight on Alkaloid Nanoformulations for the Treatment of Lung Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, Q. A Review on Polymer and Lipid-Based Nanocarriers and Its Application to Nano-Pharmaceutical and Food-Based Systems. Frontiers in Nutrition 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chime, S.A.; Kenechukwu, F.C.; Attama, A.A. Nanoemulsions–Advances in Formulation, Characterization and Applications in Drug Delivery; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 9789535116288. [Google Scholar]

- Odriozola-Serrano, I.; Oms-Oliu, G.; Martã n-Belloso, O. Nanoemulsion-Based Delivery Systems to Improve Functionality of Lipophilic Components. Front. Nutr. 2014, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.R.; Ho, M.J.; Choi, Y.W.; Kang, M.J. A Polyvinylpyrrolidone-Based Supersaturable Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System for Enhanced Dissolution of Cyclosporine A. Polymers 2017, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Beg, S.; Khurana, R.K.; Sandhu, P.S.; Kaur, R.; Katare, O.P. Recent advances in self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS). Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carr. Syst. 2014, 31, 121–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Montañez, G.; Ragazzo-Sánchez, J.A.; Picart-Palmade, L.; Calderón-Santoyo, M.; Chevalier-Lucia, D. Optimization of Nanoemulsions Processed by High-Pressure Homogenization to Protect a Bioactive Extract of Jackfruit (Artocarpus Heterophyllus Lam). Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies 2017, 40, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariffa, Y.N.; Tan, T.B.; Uthumporn, U.; Abas, F.; Mirhosseini, H.; Nehdi, I.A.; Wang, Y.-H.; Tan, C.P. Producing a Lycopene Nanodispersion: Formulation Development and the Effects of High Pressure Homogenization. Food Research International 2017, 101, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabilo-Munizaga, G.; Villalobos-Carvajal, R.; Herrera-Lavados, C.; Moreno-Osorio, L.; Jarpa-Parra, M.; Pérez-Won, M. Physicochemical Properties of High-Pressure Treated Lentil Protein-Based Nanoemulsions. LWT 2019, 101, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhou, Y.; Bai, L.; Liu, F.; Deng, Y.; McClements, D.J. Fabrication of β-Carotene Nanoemulsion-Based Delivery Systems Using Dual-Channel Microfluidization: Physical and Chemical Stability. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2017, 490, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aswathanarayan, J.B.; Vittal, R.R. Nanoemulsions and Their Potential Applications in Food Industry. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahruie, H.H.; Ziaee, E.; Eskandari, M.H.; Hosseini, S.M.H. Characterization of Basil Seed Gum-Based Edible Films Incorporated with Zataria Multiflora Essential Oil Nanoemulsion. Carbohydrate Polymers 2017, 166, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kaur, K.; Uppal, S.; Mehta, S.K. Ultrasound Processed Nanoemulsion: A Comparative Approach between Resveratrol and Resveratrol Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex to Study Its Binding Interactions, Antioxidant Activity and UV Light Stability. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2017, 37, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuesiang, P.; Siripatrawan, U.; Sanguandeekul, R.; Mcclements, D.J.; McLandsborough, L. Antimicrobial Activity of PIT-Fabricated Cinnamon Oil Nanoemulsions: Effect of Surfactant Concentration on Morphology of Foodborne Pathogens. Food Control 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Melero, J.; López-Mitjavila, J.-J.; García-Celma, M.J.; Rodríguez-Abreu, C.; Grijalvo, S. Rosmarinic Acid-Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticles Prepared by Low-Energy Nano-Emulsion Templating: Formulation, Biophysical Characterization, and In Vitro Studies. Materials 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, S.N.; Utra, U.; Alias, A.K.; Tan, T.B.; Tan, C.P.; Yussof, N.S. Physical, Morphological and Antibacterial Properties of Lime Essential Oil Nanoemulsions Prepared via Spontaneous Emulsification Method. LWT 2020, 128, 109388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, I.F.; Anand, S.; Varanasi, K.K. Creating Nanoscale Emulsions Using Condensation. Nature Communications 2017, 8, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering emulsions. Available online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pickering_emulsion. Accessed on 06 April 2023.

- Kang, D.J.; Bararnia, H.; Anand, S. Synthesizing Pickering Nanoemulsions by Vapor Condensation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 21746–21754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simion, V.; Stan, D.; Constantinescu, C.A.; Deleanu, M.; Dragan, E.; Tucureanu, M.M.; Gan, A.M.; Butoi, E.; Constantin, A.; Manduteanu, I.; et al. Conjugation of curcumin-loaded lipid nanoemulsions with cell-penetrating peptides increases their cellular uptake and enhances the anti-inflammatory effects in endothelial cells. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2016, 68, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazari-Vanani, R.; Moezi, L.; Heli, H. In Vivo Evaluation of a Self-Nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery System for Curcumin. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2017, 88, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugasini, D.; Lokesh, B.R. Curcumin and Linseed Oil Co-Delivered in Phospholipid Nanoemulsions Enhances the Levels of Docosahexaenoic Acid in Serum and Tissue Lipids of Rats. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 2017, 119, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 128. Gouda,W.; Hafiz, N.A.; Mageed, L.; Alazzouni, A.S.; Khalil,W.K.; Afify, M.; Abdelmaksoud, M.D. Effects of nano-curcumin on gene expression of insulin and insulin receptor. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent.

- Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Bao, Z.; Wu, L. Curcumin Nanoemulsions Inhibit Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cell Proliferation by PI3K/Akt/MTOR Suppression and MiR-199a Upregulation: A Preliminary Study. Oral Diseases 2022, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhao, G.; Xia, Q.; Sun, R. Development and characterization of a self-double-emulsifying drug delivery system containing both epigallocatechin-3-gallate and α-lipoic acid. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 6567–6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutelidakis, A.E.; Argyri, K.; Sevastou, Z.; Lamprinaki, D.; Panagopoulou, E.; Paximada, E.; Sali, A.; Papalazarou, V.; Mallouchos, A.; Evageliou, V.; et al. Bioactivity of Epigallocatechin Gallate Nanoemulsions Evaluated in Mice Model. Journal of Medicinal Food 2017, 20, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, P.Y.; Gue, S.Z.; Leow, S.K.; Goh, L.B. Solid self-microemulsifying system (S-SMECS) for enhanced bioavailability and pigmentation of highly lipophilic bioactive carotenoid. Powder Technol. 2015, 274, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.H.; Shanmugam, S.; Thapa, P.; Lee, E.-S.; Balakrishnan, P.; Baskaran, R.; Yoon, S.-K.; Choi, H.-G.; Yong, C.S.; Yoo, B.K.; et al. Novel self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system for enhanced solubility and dissolution of lutein. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2010, 33, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugam, S.; Baskaran, R.; Balakrishnan, P.; Thapa, P.; Yong, C.S.; Yoo, B.K. Solid self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (S-SNEDDS) containing phosphatidylcholine for enhanced bioavailability of highly lipophilic bioactive carotenoid lutein. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2011, 79, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, J.; Xiao, H.; Mcclements, D. Nanoemulsion-Based Delivery Systems for Poorly Water-Soluble Bioactive Compounds: Influence of Formulation Parameters on Polymethoxyflavone Crystallization. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 272, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, C.; Decker, E.; Xiao, H.; McClements, D.J. Nanoemulsion delivery systems: Influence of carrier oil on β-carotene bioaccessibility. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1440–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, T.V.A.; Kim, S.; Choi, Y.; Kwak, H.-S.; Lee, S.J.; Wen, J.; Oey, I.; Ko, S. Antioxidant activity and bioaccessibility of size-different nanoemulsions for lycopene-enriched tomato extract. Food Chem. 2015, 178, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.H.; Guo, Y.; Song, D.; Bruno, R.; Lu, X. Quercetin-Containing Self-Nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery System for Improving Oral Bioavailability. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 103, 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuior, E.V.; Deleanu, M.; Constantinescu, C.A.; Rebleanu, D.; Voicu, G.; Simionescu, M.; Calin, M. Functional Role of VCAM-1 Targeted Flavonoid-Loaded Lipid Nanoemulsions in Reducing Endothelium Inflammation. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Xiang, C.; Wang, P.; Yin, Y.; Hou, Y. Biocompatible nanoemulsions based on hemp oil and less surfactants for oral delivery of baicalein with enhanced bioavailability. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017, 12, 2923–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhao, G.; Tang, T.; Dong, W.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Liao, Z. Preparation, Characterization, and Pharmacokinetic Evaluation of Imperatorin Lipid Microspheres and Their Effect on the Proliferation of MDA-MB-231 Cells. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, S.D.; Ramadhani, C.C.; Veronika, A.; Ningrum, A.D.K.; Nugroho, B.H.; Syukri, Y. Study of Self Nano-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System (SNEDDS) Loaded Red Fruit Oil (Pandanus Conoideus Lamk.) As an Eliminated Cancer Cell MCF-7. Journal of drug delivery 2018, 8, 229–232. [Google Scholar]

- JUFRI, M.; ISWANDANA, R.; WARDANI, D.A.; MALIK, S.F. FORMULATION OF RED FRUIT OIL NANOEMULSION USING SUCROSE PALMITATE. International Journal of Applied Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, A.; Kósa, D.; Nemes, D.; Ujhelyi, Z.; Fehér, P.; Vecsernyés, M.; Váradi, J.; Fenyvesi, F.; Kuki, Á.; Gonda, S.; Vasas, G.; Gesztelyi, R.; Salimi, A.; Bácskay, I. Self-Nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery Systems Containing Plantago lanceolata—An Assessment of Their Antioxidant and Antiinflammatory Effects. Molecules 2017, 22, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prihapsara, F.; Harini, M.; Widiyani, T.; Artanti, A.N.; Ani, I.L. Antidiabetic Activity of Self Nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery System from Bay Leaves (Eugenia Polyantha Wight) Ethyl Acetate Fraction. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2017, 176, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Meng, H.; Xin, L.; Xia, M.; Shen, H.; Li, G.; Xie, Y. Self-Nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery Systems of Myricetin: Formulation Development, Characterization, and in Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2017, 160, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, N.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Adu-Frimpong, M.; Sun, C.; Zhang, K.; Yang, Q.; Wei, Q.; Ji, H.; Toreniyazov, E.; et al. Improved oral bioavailability of myricitrin by liquid self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 52, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.A. , Rizwan; Naqvi, Atta Abbas; Alam, Md Aftab; Abdur Rub, Rehan; Ahmad, Farhan Jalees Enhancement of Quercetin Oral Bioavailability by Self-Nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery System and Their Quantification Through Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry in Cerebral Ischemia. Drug Res (Stuttg) 2017, 67, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakab, G.; Fülöp, V.; Bozó, T.; Balogh, E.; Kellermayer, M.; Antal, I. Optimization of Quality Attributes and Atomic Force Microscopy Imaging of Reconstituted Nanodroplets in Baicalin Loaded Self-Nanoemulsifying Formulations. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Bao, Y. Nanodelivery of Natural Isothiocyanates as a Cancer Therapeutic. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2021, 167, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinas-Basurto, D.; Ibarra, J.; Juárez, J.; Burboa, M.G.; Barbosa, S.; Taboada, P.; Troncoso-Rojas, R.; Valdez, M.A. Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) Nanoparticles for Sustained Release of Allyl Isothiocyanate: Characterization, in Vitro Release and Biological Activity. Journal of Microencapsulation 2017, 34, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinas-Basurto, D.; Juarez, J.; Valdez, A.M.; Burboa, G.M.; Barbosa, S.; Taboada, P. Targeted Drug Delivery Via Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor for Sustained Release of Allyl Isothiocyanate. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 18, 1252–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kaur, K.; Pandey, S.K.; Kumar, R.; Uppal, S.; Mehta, S.K. Fabrication of Benzylisothiocynate Encapsulated Nanoemulsion through Ultrasonication: Augmentation of Anticancer and Antimicrobial Attributes. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2018, 263, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppal, S.; Aashima; Kumar, R. ; Sareen, S.; Kaur, K.; Mehta, S.K. Biofabrication of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Using Emulsification for an Efficient Delivery of Benzyl Isothiocyanate. Applied Surface Science 2020, 510, 145011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppal, S.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, R.; Kaur, K.; Bhatia, A.; Mehta, S.K. Effect of Benzyl Isothiocyanate Encapsulated Biocompatible Nanoemulsion Prepared via Ultrasonication on Microbial Strains and Breast Cancer Cell Line MDA MB 231. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2020, 596, 124732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccelli, A.; Vitanza, L.; Imbriano, A.; Fraschetti, C.; Filippi, A.; Goldoni, P.; Maurizi, L.; Ammendolia, M.G.; Crestoni, M.E.; Fornarini, S.; Menghini, L.; Carafa, M.; Marianecci, C.; Longhi, C.; Rinaldi, F. Satureja montana L. Essential Oils: Chemical Profiles/Phytochemical Screening, Antimicrobial Activity and O/W NanoEmulsion Formulations. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, F.; Maurizi, L.; Conte, A.L.; Marazzato, M.; Maccelli, A.; Crestoni, M.E.; Hanieh, P.N.; Forte, J.; Conte, M.P.; Zagaglia, C.; et al. Nanoemulsions of Satureja Montana Essential Oil: Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity against Avian Escherichia Coli Strains. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.C.; Chang, C.W.; Hsu, M.C.; Wu, Y.T. Self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system for resveratrol: Enhanced oral bioavailability and reduced physical fatigue in rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.F.; Zhou, J.; Hu, X.; Cong, Z.Q.; Liu, C.Y.; Pan, R.L.; Chang, Q.; Liu, X.M.; Liao, Y.H. Improving oral bioavailability of resveratrol by a udp-glucuronosyltransferase inhibitory excipient-based self-microemulsion. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 114, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugapriya, K.; Kim, H.; Kang, H.W. A new alternative insight of nanoemulsion conjugated with k-carrageenan for wound healing study in diabetic mice: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 133, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmala, M.J.; Durai, L.; Gopakumar, V.; Nagarajan, R. Anticancer and antibacterial effects of a clove bud essential oil-based nanoscale emulsion system. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 6439–6450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, A.V.M.; Karimi, E.; Oskoueian, E.; Mohammad, G.R.K.S.; Shafaei, N. Chemical investigation and screening of anti-cancer potential of Syzygium aromaticum L. bud (clove) essential oil nanoemulsion. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 49.

- Colombo, M.; Melchiades, G.L.; Figueiró, F.; Battastini, A.M.O.; Teixeira, H.F.; Koester, L.S. Validation of an HPLC-UV method for analysis of Kaempferol-loaded nanoemulsion and its application to in vitro and in vivo tests. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2017, 145, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Figueiró, F.; Dias, A. de F.; Teixeira, H.F.; Battastini, A.M.O.; Koester, L.S. Kaempferol-Loaded Mucoadhesive Nanoemulsion for Intranasal Administration Reduces Glioma Growth in Vitro. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2018, 543, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Li, F.; Li, Z.; McClements, D.J.; Xiao, H. Encapsulation of Carotenoids in Emulsion-Based Delivery Systems: Enhancement of β-Carotene Water-Dispersibility and Chemical Stability. Food Hydrocolloids 2017, 69, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, A.K. de O.C.; Gomes, C. de C.; Amaral, M.L.Q. de A.; Medeiros, L.D.G. de; Medeiros, I.; Porto, D.L.; Aragão, C.F.S.; Maciel, B.L.L.; Morais, A.H. de A.; Passos, T.S. Nanoencapsulation Improved Water Solubility and Color Stability of Carotenoids Extracted from Cantaloupe Melon (Cucumis Melo L.). Food Chemistry 2019, 270, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcón-Alarcón, C.; Inostroza-Riquelme, M.; Torres-Gallegos, C.; Araya, C.; Miranda, M.; Sánchez-Caamaño, J.C.; Moreno-Villoslada, I.; Oyarzun-Ampuero, F.A. Protection of Astaxanthin from Photodegradation by Its Inclusion in Hierarchically Assembled Nano and Microstructures with Potential as Food. Food Hydrocolloids 2018, 83, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.D.; Poejo, J.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Donsì, F.; Serra, A.T.; Duarte, C.M.M.; Ferrari, G.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Vicente, A.A. Evaluating the Behaviour of Curcumin Nanoemulsions and Multilayer Nanoemulsions during Dynamic in Vitro Digestion. Journal of Functional Foods 2018, 48, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiga-Artigas, M.; Lanjari-Pérez, Y.; Martín-Belloso, O. Curcumin-Loaded Nanoemulsions Stability as Affected by the Nature and Concentration of Surfactant. Food Chemistry 2018, 266, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdou, E.S.; Galhoum, G.F.; Mohamed, E.N. Curcumin Loaded Nanoemulsions/Pectin Coatings for Refrigerated Chicken Fillets. Food Hydrocolloids 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, S.; Zeynali, F.; Almasi, H. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Efficiency of Nanoemulsion-Based Edible Coating Containing Ginger (Zingiber Officinale) Essential Oil and Its Effect on Safety and Quality Attributes of Chicken Breast Fillets. Food Control 2018, 84, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbas, E.; Soyler, B.; Oztop, M.H. Formation of Capsaicin Loaded Nanoemulsions with High Pressure Homogenization and Ultrasonication. LWT 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advancing the Science of Nanotechnology in Drug Development. Available online at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/advancing-science-nanotechnology-drug-development. Accessed on. 28 April.

- Drug Products, including Biological Products, that Contain Nanomaterials. Available online at https://www.fda.gov/media/109910/download (Accessed on ). 06 April.

- D'Mello, S. R. , Cruz, C. N., Chen, M. L., Kapoor, M., Lee, S. L., & Tyner, K. M. (2017). The evolving landscape of drug products containing nanomaterials in the United States. M. ( 12(6), 523–529. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C. N. , Tyner, K. M., Velazquez, L., Hyams, K. C., Jacobs, A., Shaw, A. B., Jiang, W., Lionberger, R., Hinderling, P., Kong, Y., Brown, P. C., Ghosh, T., Strasinger, C., Suarez-Sharp, S., Henry, D., Van Uitert, M., Sadrieh, N., & Morefield, E. (2013). CDER risk assessment exercise to evaluate potential risks from the use of nanomaterials in drug products. ( 15(3), 623–628. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyner, K. M. , Zou, P., Yang, X., Zhang, H., Cruz, C. N., & Lee, S. L. (2015). Product quality for nanomaterials: current U.S. experience and perspective. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Nanomedicine and nanobiotechnology. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. L. , John, M., Lee, S. L., & Tyner, K. M. (2017). Development Considerations for Nanocrystal Drug Products. M. ( 19(3), 642–651. [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, M. , Lee, S. L., & Tyner, K. M. (2017). Liposomal Drug Product Development and Quality: Current US Experience and Perspective. The AAPS journal. [CrossRef]

- Zou, P. , Tyner, K., Raw, A., & Lee, S. (2017). Physicochemical Characterization of Iron Carbohydrate Colloid Drug Products. ( 19(5), 1359–1376. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najahi-Missaoui, W.; Arnold, R.D.; Cummings, B.S. Safe Nanoparticles: Are We There Yet? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toragall, V.; Jayapala, N.; P, M.S.; Vallikanan, B. Biodegradable Chitosan-Sodium Alginate-Oleic Acid Nanocarrier Promotes Bioavailability and Target Delivery of Lutein in Rat Model with No Toxicity. Food Chemistry 2020, 330, 127195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missaoui, W.N.; Arnold, R.D.; Cummings, B.S. Toxicological status of nanoparticles: What we know and what we don’t know. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 295, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freyre-Fonseca, V.; Delgado-Buenrostro, N.L.; Gutiérrez-Cirlos, E.B.; Calderón-Torres, C.M.; Cabellos-Avelar, T.; Sánchez-Pérez, Y.; Pinzón, E.; Torres, I.; Molina-Jijón, E.; Zazueta, C.; et al. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Impair Lung Mitochondrial Function. Toxicology Letters 2011, 202, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Duan, J.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Z. Silica nanoparticle-induced blockage of autophagy leads to autophagic cell death in HepG2 cells. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2017, 13, 485–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cui, X.; Zhai, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Zhu, H.; Qu, G.; Jiang, G.; et al. Tuning Cell Autophagy by Diversifying Carbon Nanotube Surface Chemistry. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 2087–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Wang, L.; Shao, P.; Sun, P.; Yang, C.S. A Review on Chemical and Physical Modifications of Phytosterols and Their Influence on Bioavailability and Safety. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 62, 5638–5657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prow, T.W.; Grice, J.E.; Lin, L.L.; Faye, R.; Butler, M.; Becker, W.; Wurm, E.M.T.; Yoong, C.; Robertson, T.A.; Soyer, H.P.; et al. Nanoparticles and Microparticles for Skin Drug Delivery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2011, 63, 470–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, M.S.; Mohammed, Y.; Pastore, M.N.; Namjoshi, S.; Yousef, S.; Alinaghi, A.; Haridass, I.N.; Abd, E.; Leite-Silva, V.R.; Benson, H.A.E.; et al. Topical and Cutaneous Delivery Using Nanosystems. Journal of Controlled Release 2017, 247, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Din, F.U.; Choi, J.Y.; Kim, D.W.; Mustapha, O.; Kim, D.S.; Thapa, R.K.; Ku, S.K.; Youn, Y.S.; Oh, K.T.; Yong, C.S.; et al. Irinotecan-Encapsulated Double-Reverse Thermosensitive Nanocarrier System for Rectal Administration. Drug Deliv 2017, 24, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, K.; Aoki, H.; Teruyama, C.; Iijima, M.; Tsutsumi, H.; Kuroda, S.; Hamano, K. A Novel Hybrid Drug Delivery System for Treatment of Aortic Aneurysms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, T.; Han, S.M.; Lim, C.; Won, W.R.; Lee, E.S.; Youn, Y.S.; Oh, K.T. A PH-Sensitive Polymer for Cancer Targeting Prepared by One-Step Modulation of Functional Side Groups. Macromolecular Research 2019, 27, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Zhang, M.; Liu, K. Colon-Targeted Drug Delivery of Polysaccharide-Based Nanocarriers for Synergistic Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 272, 118530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, T.; Lim, C.; Hoang, N.H.; Kim, J.E.; Lee, E.S.; Youn, Y.S.; Oh, K.T. Synergistic Photodynamic Therapeutic Effect of Indole-3-Acetic Acid Using a PH Sensitive Nano-Carrier Based on Poly(Aspartic Acid-Graft-Imidazole)-Poly(Ethylene Glycol). J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 8498–8505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjili, H.K.; Ghasemi, P.; Malvandi, H.; Mousavi, M.S.; Attari, E.; Danafar, H. Pharmacokinetics and in vivo delivery of curcumin by copolymeric mPEG-PCL micelles. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2017, 116, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, T.J.; Wick, P.; Manser, P.; Spohn, P.; Grass, R.N.; Limbach, L.K.; Bruinink, A.; Stark, W.J. In vitro cytotoxicity of oxide nanoparticles: Comparison to asbestos, silica, and the effect of particle solubility. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 4374–4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, H.L.; Cronholm, P.; Gustafsson, J.; Moller, L. Copper oxide nanoparticles are highly toxic: A comparison between metal oxide nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008, 21, 1726–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayes, C.M.; Gobin, A.M.; Ausman, K.D.; Mendez, J.; West, J.L.; Colvin, V.L. Nano-C60 cytotoxicity is due to lipid peroxidation. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 7587–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, T.C.; Saleh, N.; Tilton, R.D.; Lowry, G.V.; Veronesi, B. Titanium dioxide (P25) produces reactive oxygen species in immortalized brain microglia (BV2): Implications for nanoparticle neurotoxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 4346–4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poland, C.A.; Duffin, R.; Kinloch, I.; Maynard, A.; Wallace, W.A.; Seaton, A.; Stone, V.; Brown, S.; Macnee, W.; Donaldson, K. Carbon nanotubes introduced into the abdominal cavity of mice show asbestos-like pathogenicity in a pilot study. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, A.B.; Hurt, R.H. Nanotoxicology: The asbestos analogy revisited. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 378–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Bai, R.; Wu, Z.; Qian, W.; Yang, L.; Cai, R.; Yan, H.; Li, T.; Pandey, V.; et al. Long-term pulmonary exposure to multi-walled carbon nanotubes promotes breast cancer metastatic cascades. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadpour, R.; Dobrovolskaia, M.A.; Cheney, D.L.; Greish, K.F.; Ghandehari, H. Subchronic and chronic toxicity evaluation of inorganic nanoparticles for delivery applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 144, 112–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousef, M.I.; Mutar, T.F.; Kamel, M.A.E. Hepato-renal toxicity of oral sub-chronic exposure to aluminum oxide and/or zinc oxide nanoparticles in rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2019, 6, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, A.; Martins, A.; Guilhermino, L. Toxicological interactions induced by chronic exposure to gold nanoparticles and microplastics mixtures in Daphnia magna. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628–629, 474–483.

- Li, J.; Schiavo, S.; Xiangli, D.; Rametta, G.; Miglietta, M.L.; Oliviero, M.; Changwen, W.; Manzo, S. Early ecotoxic effects of ZnO nanoparticle chronic exposure in Mytilus galloprovincialis revealed by transcription of apoptosis and antioxidant-related genes. Ecotoxicology 2018, 27, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdörster, G.; Ferin, J.; Lehnert, B.E. Correlation between particle size, in vivo particle persistence, and lung injury. Environ. Health Perspect. 1994, 102 (Suppl. 5), 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, N.M.; Rogers, N.J.; Apte, S.C.; Batley, G.E.; Gadd, G.E.; Casey, P.S. Comparative toxicity of nanoparticulate ZnO, bulk ZnO, and ZnCl2 to a freshwater microalga (Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata): The importance of particle solubility. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 8484–8490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Kovochich, M.; Liong, M.; Madler, L.; Gilbert, B.; Shi, H.; Yeh, J.I.; Zink, J.I.; Nel, A.E. Comparison of the mechanism of toxicity of zinc oxide and cerium oxide nanoparticles based on dissolution and oxidative stress properties. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 2121–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadrieh, N.; Wokovich, A.M.; Gopee, N.V.; Zheng, J.; Haines, D.; Parmiter, D.; Siitonen, P.H.; Cozart, C.R.; Patri, A.K.; McNeil, S.E.; et al. Lack of Significant Dermal Penetration of Titanium Dioxide from Sunscreen Formulations Containing Nano- and Submicron-Size TiO2 Particles. Toxicological Sciences 2010, 115, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevacqua, E.; Occhiuzzi, M.A.; Grande, F.; Tucci, P. TiO2-NPs toxicity and safety: an update of the findings published over the last six years. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry, 2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutillier, S.; Fourmentin, S.; Laperche, B. History of titanium dioxide regulation as a food additive: a review. Environ Chem Lett 2022, 20, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicine Agency (EMA). Available online at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/final-feedback-european-medicine-agency-ema-eu-commission-request-evaluate-impact-removal-titanium_en.pdf. Accessed on 06 April 2023.

- McClements, D.J. Emulsion design to improve the delivery of functional lipophilic components. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 1, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, M.A.; Jayaraman, M.; Matsuda, S.; Liu, J.; Barros, S.; Querbes, W.; Tam, Y.K.; Ansell, S.M.; Kumar, V.; Qin, J.; et al. Biodegradable lipids enabling rapidly eliminated lipid nanoparticles for systemic delivery of RNAi therapeutics. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 1570–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xia, T.; Duch, M.C.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, R.; Sun, B.; Lin, S.; Meng, H.; Liao, Y.P.; et al. Pluronic F108 coating decreases the lung fibrosis potential of multiwall carbon nanotubes by reducing lysosomal injury. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 3050–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlu, G.M.; Budinger, G.R.; Green, A.A.; Urich, D.; Soberanes, S.; Chiarella, S.E.; Alheid, G.F.; McCrimmon, D.R.; Szleifer, I.; Hersam, M.C. Biocompatible nanoscale dispersion of single-walled carbon nanotubes minimizes in vivo pulmonary toxicity. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 1664–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rosso, T.; Louro, S.R.W.; Deepak, F.L.; Romani, E.C.; Zaman, Q.; Tahir; Pandoli, O. ; Cremona, M.; Freire Junior, F.L.; De Beule, P.A.A.; et al. Biocompatible Au@Carbynoid/Pluronic-F127 Nanocomposites Synthesized by Pulsed Laser Ablation Assisted CO2 Recycling. Applied Surface Science 2018, 441, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Ding, J.; Xu, J.; Deng, J.; Guo, J. TiO2 nanoparticles co-doped with silver and nitrogen for antibacterial application. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2010, 10, 4868–4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, W.Y.; Amal, R.; Madler, L. Flame spray pyrolysis: An enabling technology for nanoparticles design and fabrication. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 1324–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, X.; Ji, Z.; Sun, B.; Zhang, H.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, S.; Meng, H.; Liao, Y.P.; Wang, M.; et al. Surface charge and cellular processing of covalently functionalized multiwall carbon nanotubes determine pulmonary toxicity. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 2352–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, C.M.; McCusker, C.D.; Yilmaz, T.; Rotello, V.M. Toxicity of gold nanoparticles functionalized with cationic and anionic side chains. Bioconjug. Chem. 2004, 15, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu,W. ;Wu, Z.; Yu, T., Jiang, C., Eds.; Kim,W.S. Recent progress on magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis, surface functional strategies and biomedical applications. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater 2015, 16, 023501. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R.; Park, I.K.; Jeong, Y.Y. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for multimodal imaging and therapy of cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 15910–15930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 225. Wu,W.; He, Q.; Jiang, C. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis and surface functionalization strategies. Nanoscale Res. Lett.

- Cardoso, V.F.; Francesko, A.; Ribeiro, C.; Banobre-Lopez, M.; Martins, P.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Advances in Magnetic Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Adv. Health Mater 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, J.; Chanana, M. Coating Matters: Review on Colloidal Stability of Nanoparticles with Biocompatible Coatings in Biological Media, Living Cells and Organisms. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 4553–4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xia, T.; Ntim, S.A.; Ji, Z.; Lin, S.; Meng, H.; Chung, C.H.; George, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; et al. Dispersal state of multiwalled carbon nanotubes elicits profibrogenic cellular responses that correlate with fibrogenesis biomarkers and fibrosis in the murine lung. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 9772–9787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenoff, J.B. Zwitteration: Coating surfaces with zwitterionic functionality to reduce nonspecific adsorption. Langmuir 2014, 30, 9625–9636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo García, K.; Zarschler, K.; Barbaro, L.; Barreto, J.A.; O’Malley, W.; Spiccia, L.; Stephan, H.; Graham, B. Zwitterionic-coated “stealth” nanoparticles for biomedical applications: Recent advances in countering biomolecular corona formation and uptake by the mononuclear phagocyte system. Small 2014, 10, 2516–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.R.; Wu, S.T.; Tsai, Z.T.; Wang, J.J.; Yen, T.C.; Tsai, J.S.; Shih, M.F.; Liu, C.L. Characterization of quaternized chitosantem. ionic-coated “stealth” nanoparticles forel potential magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent for cell tracking. Polym. Int.

- Tang, S.; Tang, Y.; Zhong, L.; Murat, K.; Asan, G.; Yu, J.; Jian, R.; Wang, C.; Zhou, P. Short- and long-term toxicities of multi-walled carbon nanotubes in vivo and in vitro. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2012, 32, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyles, M.S.; Young, L.; Brown, D.M.; MacCalman, L.; Cowie, H.; Moisala, A.; Smail, F.; Smith, P.J.; Proudfoot, L.; Windle, A.H.; et al. Multi-walled carbon nanotube induced frustrated phagocytosis, cytotoxicity and pro-inflammatory conditions in macrophages are length dependent and greater than that of asbestos. Toxicol. Vitro 2015, 29, 1513–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.T.; Babu, B.; Stella, R.J.; Manjari, V.P.; Ravikumar, R.V. Spectral investigations on undoped and Cu(2)(+) doped ZnO-CdS composite nanopowders. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc 2015, 139, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adeleye, A.S.; Pokhrel, S.; Madler, L.; Keller, A.A. Influence of nanoparticle doping on the colloidal stability and toxicity of copper oxide nanoparticles in synthetic and natural waters. Water Res. 2018, 132, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, J.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Akhtar, M.J.; Alhadlaq, H.A.; Alshamsan, A.; Khan, S.T.; Wahab, R.; Al-Khedhairy, A.A.; Al-Salim, A.; Musarrat, J.; et al. Copper doping enhanced the oxidative stress-mediated cytotoxicity of TiO2 nanoparticles in A549 cells. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2018, 37, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, S.; Pokhrel, S.; Xia, T.; Gilbert, B.; Ji, Z.; Schowalter, M.; Rosenauer, A.; Damoiseaux, R.; Bradley, K.A.; Madler, L.; et al. Use of a rapid cytotoxicity screening approach to engineer a safer zinc oxide nanoparticle through iron doping. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Zhao, Y.; Sager, T.; George, S.; Pokhrel, S.; Li, N.; Schoenfeld, D.; Meng, H.; Lin, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Decreased dissolution of ZnO by iron doping yields nanoparticles with reduced toxicity in the rodent lung and zebrafish embryos. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 1223–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, M.P.; Pardeshi, S.R.; Pardeshi, C.V.; Sonawane, G.A.; Shinde, M.N.; Deshmukh, P.K.; Naik, J.B.; Kulkarni, A.D. Recent Advances in Phytochemical-Based Nano-Formulation for Drug-Resistant Cancer. Medicine in Drug Discovery 2021, 10, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Edible Plants | Essential Oils | Benefits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brightly Colored | Not Brightly Colored | ||

| Berries | Potatoes Almonds Pecans Pistachios Cauliflower Walnuts Cashews Hazelnuts Tea Dark chocolate Cacao beans Barley Beans Lentils Rice Coffee Mung beans Soybeans Cloves Cinnamon Cumin Nutmeg |

Pine needles Cedar Lavender |

Boost the immune system [28] Combat OS and FR [29] ⇓ Blood sugar levels [29,30] ⇓ Blood pressure [28] ⇓ Diabetes risk [29,31] ⇓ Serious health issues [29,31] Prevent chronic disease [28,29] Protect from pathogens [32,33,34] Protect brain and liver [28] ⇓ Cholesterol [28] ⇓ Inflammation [29,35,36] Support detoxification [29,37] Ward off osteoporosis [28] |

| Cranberries | |||

| Blackberries | |||

| Strawberries | |||

| Cherries | |||

| Currants | |||

| Grapes | |||

| Plums | |||

| Purple potatoes | |||

| Red Cabbage | |||

| Cabbage | |||

| Kohlrabi | |||

| Broccoli sprouts | |||

| Apples | |||

| Bananas | |||

| Peaches | |||

| Antiparasitic herbs | |||

| Egg yolks | |||

| Orange peppers | |||

| Oranges | |||

| Pumpkins | |||

| Yellow corn | |||

| Kale | |||

| Parsley | |||

| Romain lettuce | |||

| Spinach | |||

| Olive oil | |||

| Melons | |||

| PHYs | Sources | Health benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Carotenoids [40,41] | Carrots, tomatoes, parsley Orange and green leafy vegetables Chenopods, fenugreek Spinach, cabbage, radish, turnips |

Antioxidant Protect against uterine, prostate, colorectal, lung, and digestive tract cancers |

| Phytosterols [41,42] | Vegetables, nuts, fruits, seeds | Suppress the growth of diverse tumour cell lines |

| Limonoids [41] | Citrus fruits | Inhibit phase I enzymes and induce phase II detoxification enzymes in liver Provide protection to lung tissue, detoxify enzymes |

| Curcuminoids [41] | Turmeric, curry powder, mango, ginger | Analgesic, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, antioxidative, anti-depressive Against hay fever, depression, ⇓ cholesterol and itching risk |

| Indole compounds [41] (Indole-3-carbinol) |

Cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, kale Brussels sprouts |

Strong antioxidant, DNA protector, chemo-preventive, anti-cancer, ⇑ heart health |

| Alkaloids [43] | Plants (also animals and bacteria) | Antimalarial, antiasthma, anticancer, cholinomimetics, vasodilatory, antiarrhythmic Analgesic, antibacterial, antihyperglycemic, psychotropic, stimulant |

| Phytoprostanes [44] Phytofurans [44] |

Almonds, vegetal oils, olives, algaePassion fruit, nut kernels, rice | Immunomodulators, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumours |

| Polyphenols [41] | Fruits, vegetables, cereals, beverages, legumes Chocolates, oilseeds | Action against free radicals, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergenic Inhibition of platelet aggregation, against hepatotoxins |

| Flavonoids * [41] | Fruits, vegetables, cereals, beverages, legumes Chocolates, oilseeds | Action against free radicals, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergenic Inhibition of platelet aggregation, against hepatotoxins |

| Iso-flavonoids ** [41] | Fruits, vegetables, cereals, beverages, legumes Chocolates, oil seeds | Action against free radicals, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergenic Inhibition of platelet aggregation, against hepatotoxins |

| Anthocyanidins ** [41] Anthocyanins ** [41] |

Fruits, vegetables, cereals, beverages, legumes Chocolates, oilseeds | Action against free radicals, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergenic Inhibition of platelet aggregation, against hepatotoxins |

| Glucosinolates [41] | Cruciferous vegetables | Protection against cancer of colon, rectum, stomach |

| Phytoestrogens [41] | Legumes, berries, whole grains, cereals Red wine, peanuts, red grapes |

Protection against bone loss, heart disease, cardiovascular diseases Protection against breast and uterine cancers |

| Terpenoids [41] Isoprenoids [41] |

Mosses, liverworts, algae, lichens, mushrooms | Antimicrobial, antiparasitic, antiviral, antiallergic, anti-inflammatory, chemotherapeutic Antihyperglycemic, antispasmodic |

| Fibers [45] | Fruits and vegetables (green leafy), oats | ⇓ Blood cholesterol, ⇓ cardiovascular disease |

| Polysaccharides [41] | Fruits and vegetables | Antimicrobial, antiparasitic, antiviral, antiallergic, anti-inflammatory ⇓ Serum, ⇑ defence mechanisms |

| Saponins [41] | Oats, leaves, flowers, green fruits of tomato | Protection against pathogens, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antiulcer agent |

| Tannins [41] | Cranberries, currants, blackberries, apples Grapes, peaches, strawberries, almonds Hazelnuts, pecans, pistachios, walnuts, barley Beans, lentils, rice, tea, cacao beans Dark chocolate, antiparasitic herbs |

Antioxidant, fight pathogens, ⇓ blood pressure, ⇓ inflammation, ⇓ serious health risks Regulate the immune system |

| Lutein [41] Zeaxanthin [41] |

Egg yolks, orange peppers, oranges, pumpkins Yellow corn, kale, parsley, romaine lettuce Spinach, pistachios, olive oil | Protect retina from damage, ⇑ eye function, ⇑ memory and brain function Promote the body’s use of insulin, ⇑ skin health, ⇓ blood pressure, ⇓ inflammation Support heart health |

| Eugenol [46] | Cloves, cinnamon, cumin, nutmeg, coffee Mung beans, soybeans, bananas, melons Strawberries, tomatoes |

Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, eliminate parasites, fights fungi Inhibits serious health concerns, protects the brain and the liver, ⇓ bacterial biofilm Supports heart and stomach health |

| Color Group | Foods | PHYs | Properties | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green | Asparagus, avocados, Celery Cucumbers, Green beans, green peppers, kale, kiwi Spinach, zucchini |

EGCG, glucosinolates, indolesisoflavones Isothiocyanates, lutein and zeaxanthin Sulforaphane |

Promote wound healing and healthy gums Support arteries, blood cells, eyes, liver, and lungs |

[16,65] |

| Purple | Black beans, blackberries Eggplants, elderberries, plums Purple cabbage, purple grapes, raisins |

Anthocyanins, flavonoids, phenols, tannins, RES | Protect against serious health issues Support arteries, bones, brain, cognition, healthy aging, and heart |

[16,65] |

| Red | Cherries, cranberries, kidney beans Red beans. strawberries, tomatoes watermelon |

Anthocyanins, ellagic acid, eugenol, hesperidin Lycopene, tannins, quercetin |

Protect against heart disease and other serious health issues Support prostate, urinary tract, and DNA health |

[16,65] |

| Yellow | Apricots, cantaloupe, carrots, grapefruit, Yellow pears, yellow peppers Yellow winter squash |

α-Carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lutein Zeaxanthin, hesperidin |

Boost the immune system, support heart and vision health | [16,65] |

| White | Apples, cauliflower Great northern beans Mushrooms, onions |

Allicin, ECGC, glucosinolates, indoles, tannins Quercetin |

Protect against heart disease and other serious health issues Support arteries, bones, and circulation |

[16] |

| Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emulsion solvent extraction Double-emulsion solvent extraction |

Low-cost | ⇑Residual solvent ⇓Encapsulation efficiency (EE) Thermal degradation Multi-steps processes Micronization step needed |

[15] |

| SD | Improved bioavailability Taste masking Modified release achievable Aseptic manufacturing Fine powders Improved stability |

High overhead Possible thermal degradation Not for every compound Not widely available Multi-steps processes Micronization step needed |

[15] |

| Liquid anti-solvent technique | Low-cost | ⇑Residual solvent ⇓ EE Thermal degradation Multi-steps processes Micronization step needed |

[15] |

| Spray freeze drying (SFD)* | Higher rate of freezing Independent control over particle size |

⇓ Biological activity Possible protein denaturation Excipients required |

[15] |

| Spray freezing into liquid (SFL)* | Higher level of biological activity High degree of atomization Ultra-rapid freezing (URF) Formation of amorphous highly porous NPs |

Possible ⇑ viscosity of the feed liquid Limited applications ⇑ Cost equipment Time and energy-intensive |

[15] |

| Thin film freezing (TFF) ** | High-yield products Flexibility on processable drugs Large-scale production Simple, efficient, robust process ⇑ stability of the protein product |

⇑-Cost equipment | [15] |

| Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) method | Single-step process Controllable particle size Controllable morphology Controllable crystallinity Monitorable residual solvent |

⇑-Cost equipment | [15] |

| Solvent evaporation technique | Low-cost | ⇑Residual solvent ⇓EE Thermal degradation Multi-steps processes Micronization step needed |

[15] |

| Nano-suspension techniques | ||

|---|---|---|

| Conventional techniques | Combined techniques (CTNI) | |

| Bottom-up (B-U) | Top-down (T-D) | Nanoedge™ Technique (Baxter Healthcare) H 69 Technology (SmartCrystal® technology group) H 42 Technology (SmartCrystal® technology) H 96 Technology (SmartCrystal®, Abbott/Soliqs, Ludwigshafen, Germany) Combination Technology (CTNO) |

| PHY | NPs/Mechanical Method (MM)/ Combined techniques (CTNI) |

Particle size | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-carotene [90] (B-U) |

n-Octenyl succinate-modified starch (NPs) | 300-600-nm-sized particles | ⇑ Dispersibility ⇑Coloring strength, ⇑ Bioavailability |

| Quercetin [91] (B-U) |

Maltodextrin (NPs) | 753-nm-sized particles | Water-re-dispersible ⇑ RSA ⇑ ORAC |

| Quercetin [92] (T-D) |

HPH (MM) + spray-drying (MM) | 400-nm-sized particles | ⇑ Antioxidant ⇑ Anti-inflammatory ⇑ Anticancer properties ⇑ Water solubility ⇑ Oral bioavailability |

| α-Tocopherol [93] (B-U) |

Supercritical assisted process | 150-nm-sized particles | ⇑ Solubility ⇑ Bioavailability |

| All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) [94] | Nanoedge™ Technique | 155-nm-sized particles | Orally administrable 30′ Operation time |

| Resveratrol (RES) [95] | H 69 Technology | 150 nm-sized NPs | Orally administrable 10 cycles HPH/1200 bar |

| RES [15] | H 42 Technology | 200 nm-sized NPs | Orally administrable 1 HPH cycle at 1500 bar |

| Hesperidin [15] * | CTNO | 599 nm-sized NPs | ⇑ Solubility Long-term stability Orally administrable Topically applicable Five homogenization cycles (1000 bar) |

| Rutin [15] ** | CTNO | 600 nm-sized NPs | ⇑ Solubility Orally administrable Topically applicable 1 Cycle of HPH at 100 bar |

| Apigenin [15] | CTNO | 275 nm-sized NPs | 1 Cycle HPH at 300 bar |

| Isoliquiritigenin [96] T-D |

Wet media milling (MM) | 238 nm-sized NPs (HPC-SSL) 354 nm-sized NPs (PVP-K30) |

⇑ Solubility ⇑ Cytotoxicity ⇑ Cellular up-take ⇑ Apoptosis induction ⇓ Toxicity |

| Celastrol [97] B-U |

Antisolvent precipitation method | 148 nm-sized NPs | Stable in plasma Orally administrable ⇑ EE% ⇑ DL% ⇑ Solubility (vitro) ⇑ Cytotoxicity (vivo) ⇑ Cumulative release (48h) |

|

Curcuma Longa L. Extracts [98] B-U |

Supercritical fluid expansion | 47 nm-sized NPs | ⇑ Solubility |

| Naringenin (NRG) [99] B-U |

Antisolvent sonoprecipitation | 117 nm-sized NPs | ⇑ Absorption in GIT ⇑ Dissolution ⇑ Oral bioavailability |

| NRG [100] B-U |

Precipitation-ultrasonication | 118 nm-sized NPs | ⇑ Drug dissolution ⇑ Pharmacokinetic profile ⇑ Stability |

| NRG [101] B-U |

HPH | 81 nm-sized NPs | ⇑ Intracellular ROS level ⇑ Mitochondrial membrane potential ⇑ Caspase-3 activity ⇑ Lipid peroxidation status ⇓ GSH levels ⇑ Antitumor activity on DLA cells ⇑ Life span ⇓ Cancer cell number ⇓ Tumor weight |

| Glaucocalyxin A [102] B-U |

Precipitation-ultrasonication | 143 nm-sized NPs | ⇑In vitro antitumor activity ⇑ In vivo anticancer efficacy |

| Oleanolic acid (OA) [103] B-U |

Organic solvent evaporation | 100 nm-sized NPs | ⇑ Stability ⇑ Saturation solubility ⇑ Dissolution rate ⇑Cytotoxicity ⇑ Bio-efficacy ⇑ Bioavailability |

|

P. guajava L. extracts [104] B-U |

Nanoprecipitation | 241-327 nm-sized NPs | ⇑ Antihyperglycemic activity ⇑ Physical parameters ⇑ Hepatic parameters ⇑ Renal parameters ⇑ Absorption ⇓ Metabolism ⇑ Stability |

|

Nigella sativa L. [105]B-U |

Nanoprecipitation | N.R. | ⇑ Total phenolic content ⇑ Total flavonoid contents ⇑ Antioxidant activity ⇑ Antidiabetic activity ⇑ Antibiofilm activity ⇑ Bioavailability |

| Type of NEs | Oily Phase | Advantages | Drawbacks | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEs o/w or w/o (100-500 nm) |

Captex 355 Captex 8000 Witepsol Myritol 318 Isopropyl myristate Capryol 90Sefsol-218 Triacetin Isopropyl myristate Castor oil Olive oil |

PHYs protection Controlled release Sustained release ⇑ DL% |

No high-melting PHYs 5-10% additives* required |

[1] | |

| SEDDSs o/w ** | ⇑ Oral bioavailability Possibility of easy scale-up ⇑ DL% Allow delivering peptides/lipids without the risk of digestion |

5-10% additives* required For low therapeutic dose PHYs Many parameters The physicochemical properties of PHYs can influence the efficiency of oral absorption and the performances of SEDDSs. |

[1] | ||

| SNEDDSs ** (<50 nm) |

SMEDDSs ** (100–200 nm) |

||||

| SDEDDSs ** (w/o/w) or (o/w/oil) | |||||

| Technique | Method | PHYs | Activity | Particle size (nm) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HET | High pressure homogenization (HPH) | Jackfruit pulp extract* rich in carotenoids | Antioxidant | 166 | [112] |

| Lycopene | Radicals scavenging activity | 92.6 | [113] | ||

| Lentil | ⇓ Blood pressure ⇓ Bad cholesterol (LDL) ⇑ Good cholesterol (HDL) ⇓ Heart disease risk |

149 | [114] | ||

| Microfluidization (MF) | β-carotene | Antioxidant | 140-160 | [115,116] | |

| Ultrasonication (US) | Essential oils (EOs)(Zataria multiflora) | Antibacterial | 91-211 | [117] | |

| RES | ⇓ Diseases by oxidative stress | 20.4 **; 24.5 *** | [118] | ||

| LET | Phase Inversion Temperature (PIT) | Cinnamon EO | Antioxidant Antimicrobial |

101 | [119] |

| Phase Inversion Composition (PIC) | Rosmarinic acid (RA) | Antiviral Anti-inflammatory Antioxidant |

70-100 | [120] | |

| Spontaneous Emulsification (SE) | Key lime (Citrus aurantifolia) EO | Antibacterial | 21 | [121] | |

| Kaffir lime (Citrus hystrix) EO | 28 | ||||

| Calamansi lime (Citrofortunella microcarpa) EO | 60 |

| PHY | Emulsion type/Method | Additives | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin | NE | Tween-20 | ⇓ Toxicity ⇑ Bioavailability ⇑ Bioactivity ⇑ Anti-inflammatory |

[125] |

| o/w SNEDDS Mild agitation |

Tween 80 PEG 600 |

⇑ Oral bioavailability ⇑ C max |

[126] | |

| NE/HPH | PEG (3%) | ⇑ Oral bioavailability ⇓ DHA levels |

[127] | |

| Emulsion–diffusion evaporation |

N.R. | ⇓ Blood glucose levels, ⇑ Insulin | [128] | |

| Interfacial prepolymer deposition and SE | Lipoid 100 | Inhibition of OSCC cell ⇓ PI3K/Akt/mTOR ⇑ miR-199a |

[129] | |

| EGCG (E) + ALA (A) | SDEDDS | PGPR S721, P10, L23. and S40 |

⇑Photo-stability Antioxidant ⇑EE |

[130] |

| EGCG | NE (o/w) | BC WPI |

No toxicity ⇑ Antioxidant |

[131] |

| Carotenoids (Paprika Oleoresin) |

SMEDDS | Tween 80 | ⇑ Solubility | [132] |

| Lutein | SMEDDS | Tween 80 Labrasol TranscutolHP/Lutro-E400 1 |

⇑ Solubility ⇑ Bioavailability |

[133,134] |

| Polymethoxyflavones (PMFs) |

NE | Tween 20 Tween 85 |

⇑ Dissolution rate | [135] |

| β-Carotene | o/w NE | Tween 20 | ⇑ Emulsion stability ⇑ Solubility ⇑ Bioaccessibility |

[136] |

| Lycopene | Microemulsion (ME) | ESE 3GIO SML |

⇑ Solubility | [137] |

| Quercetin | SNEDDS | Tween 80PEG 400 | ⇑ Solubility | [138] |

| Naringenin Hesperetin |

NE | Glycerin | ⇑ Solubility ⇑ In vitro stability No cytotoxic (vitro) No hemolytic (vivo) Anti-inflammatory |

[139] |

| Baicalein | NE/HPH | PEGM Sodium oleate Hoechst 33258 3,3-DODOXAP |

⇑ Oral bioavailability ⇑GIT permeability ⇑Transcellular transport ability ⇓ Cytotoxicity |

[140] |

| Imperatorin | NE/HSS NE/HPH |

Polaxamer 188 | ⇑ Bioavailability Antiploriferative (MDA-MB-231) |

[141] |

| Pandanus conoideus Lamk (red fruit) | SNEDDS | PPG Tween 20 |

⇑ Cytotoxic activity | [142] |

| Pandanus conoideus Lamk (red fruit) | NE/high-speed mixer | PPG SEPIGEL 305™ |

Antioxidant | [143] |

| Plantago lanceolata L. | SNEDDS | Labrasol or Kolliphor RH 40 Transcutol HP | ⇑ Solubility ⇑ Permeability ⇑ Bioavailability ⇑ Pharmacological effects |

[144] |

| Bay Leaves extracts (Eugenia polyantha Wight) |

Tween 80 PEG 400 |

[145] | ||

| Myricitrin | Capryol 90 Cremophor RH 40 PEG 400 Cremophor EL Transcutol HP |

[146] | ||

| Myricitrin | Cremophor EL35 Dimethyl carbinol |

[147] | ||

| Quercetin | PEG 200 Tween 40 Tween 60 Tween 80 PEG 400 Transcutol HP |