Submitted:

06 May 2023

Posted:

09 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. GC–IMS Analysis

2.2.2. GC–IMS Analysis

2.2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

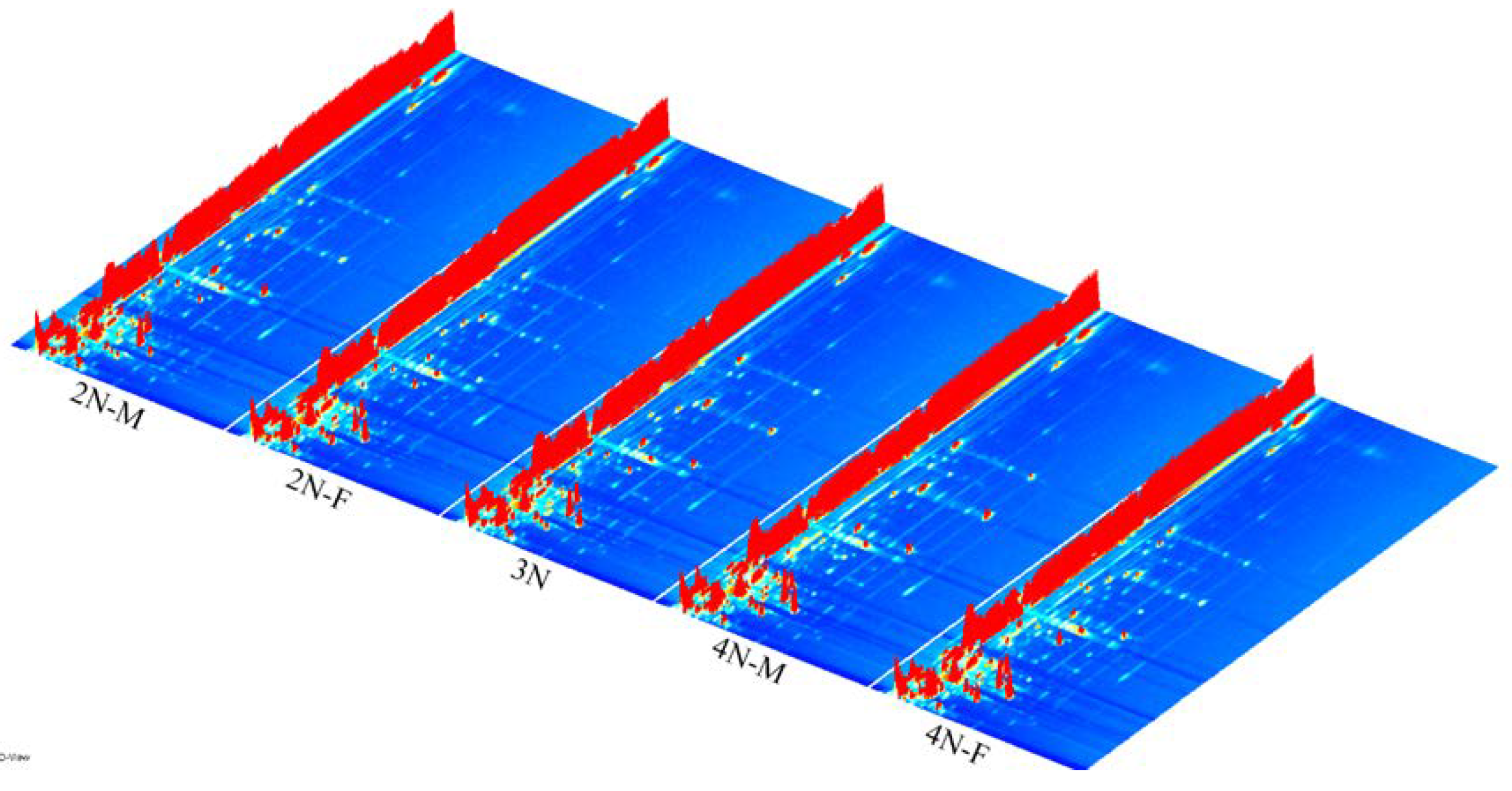

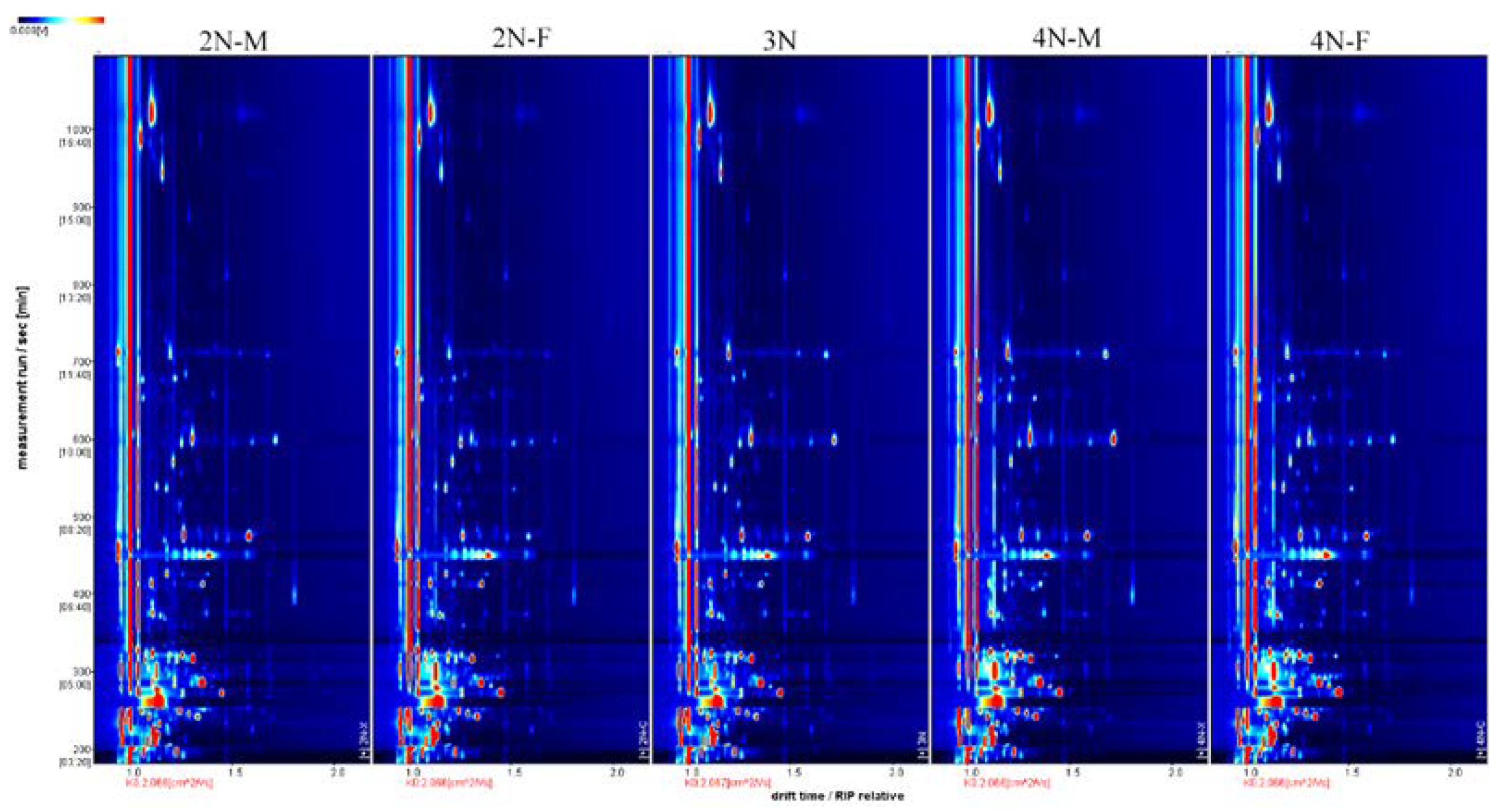

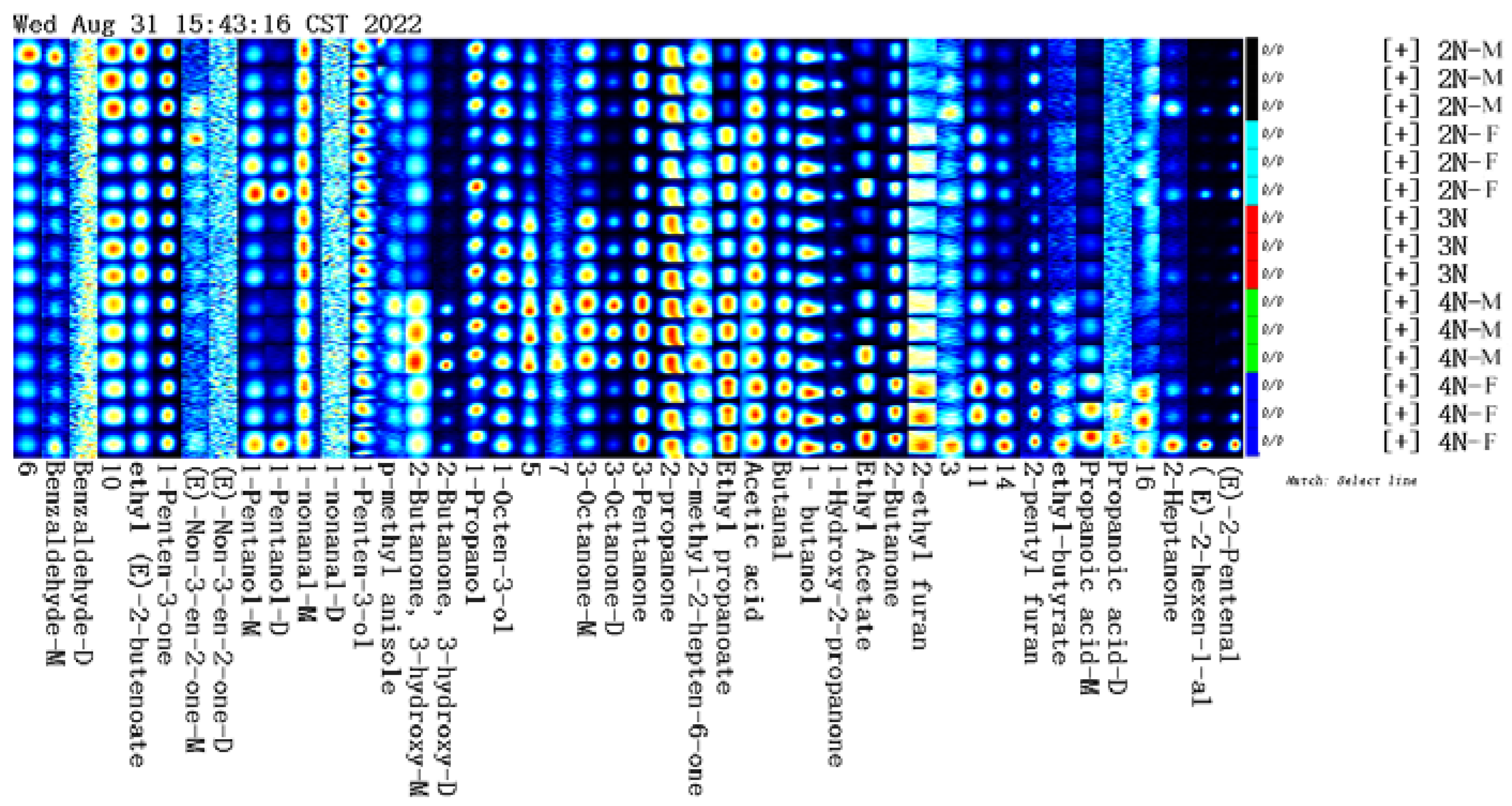

3.1. GC-IMS Profiles of Male and Female Oysters with Different Ploidy Levels

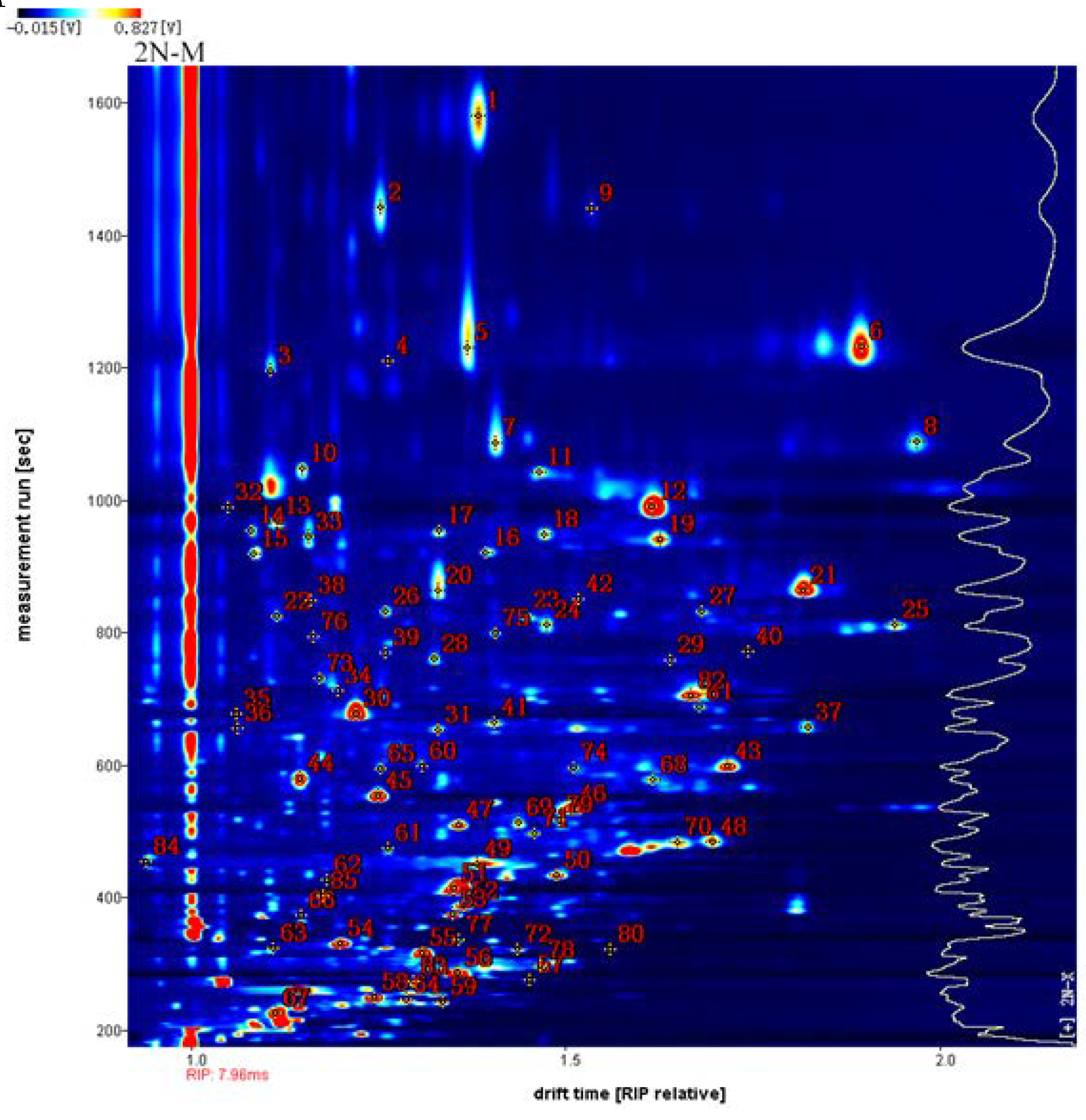

3.2. Identification of VOCs in Male and Female Oysters with Different Ploidy Levels

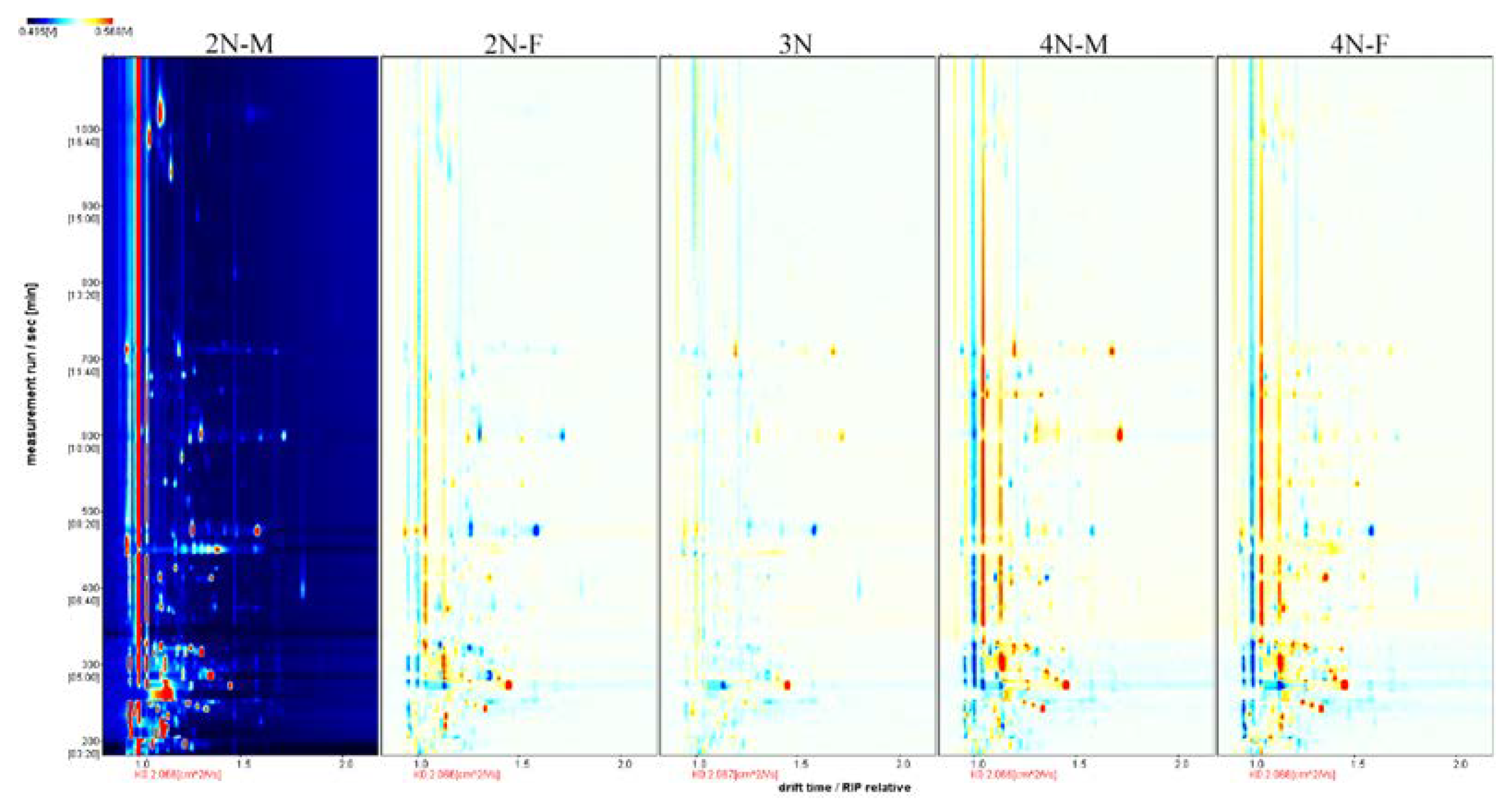

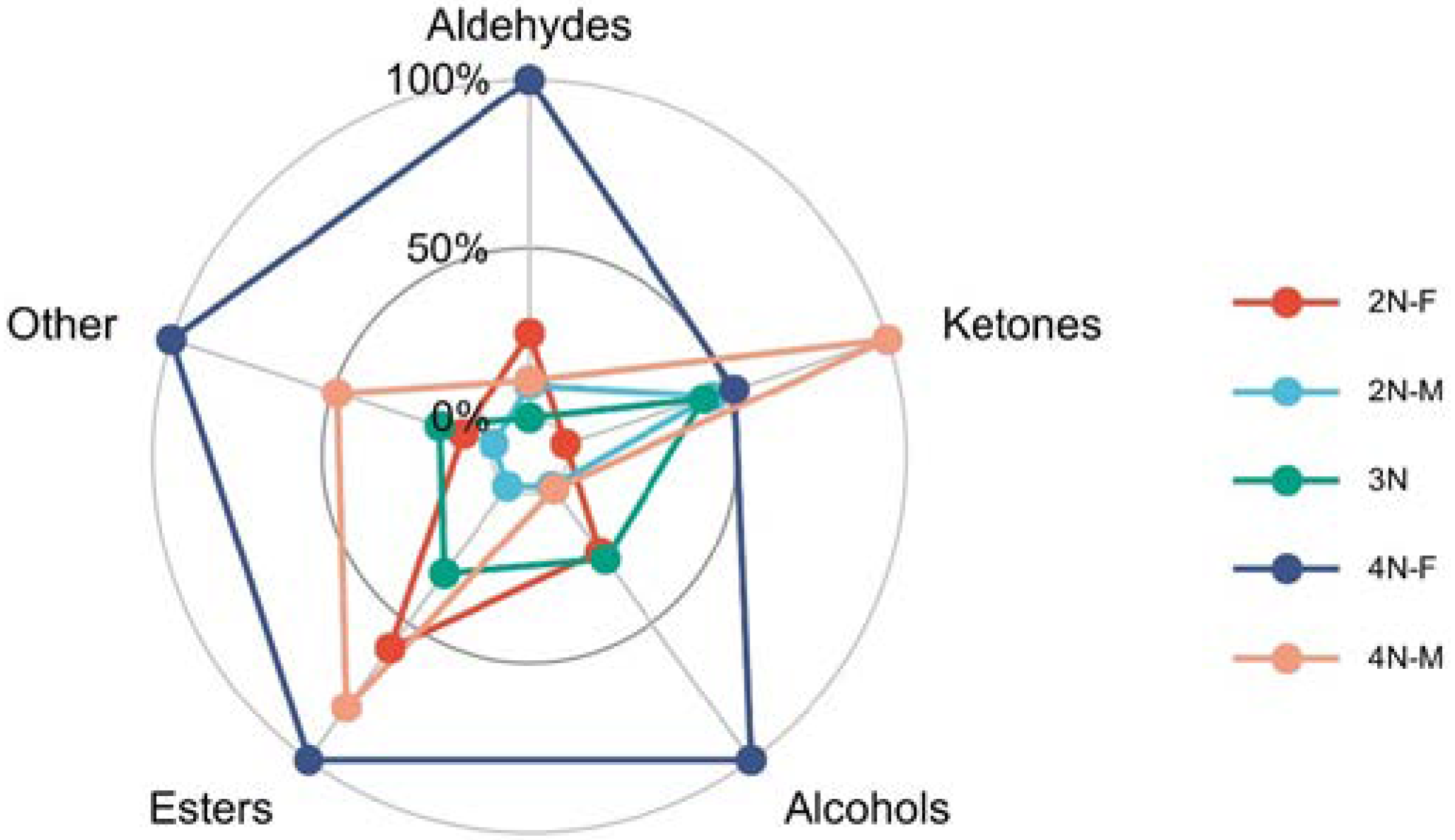

3.3. Fingerprint Analysis of VOCs in Male and Female Oysters with Different Ploidy Levels

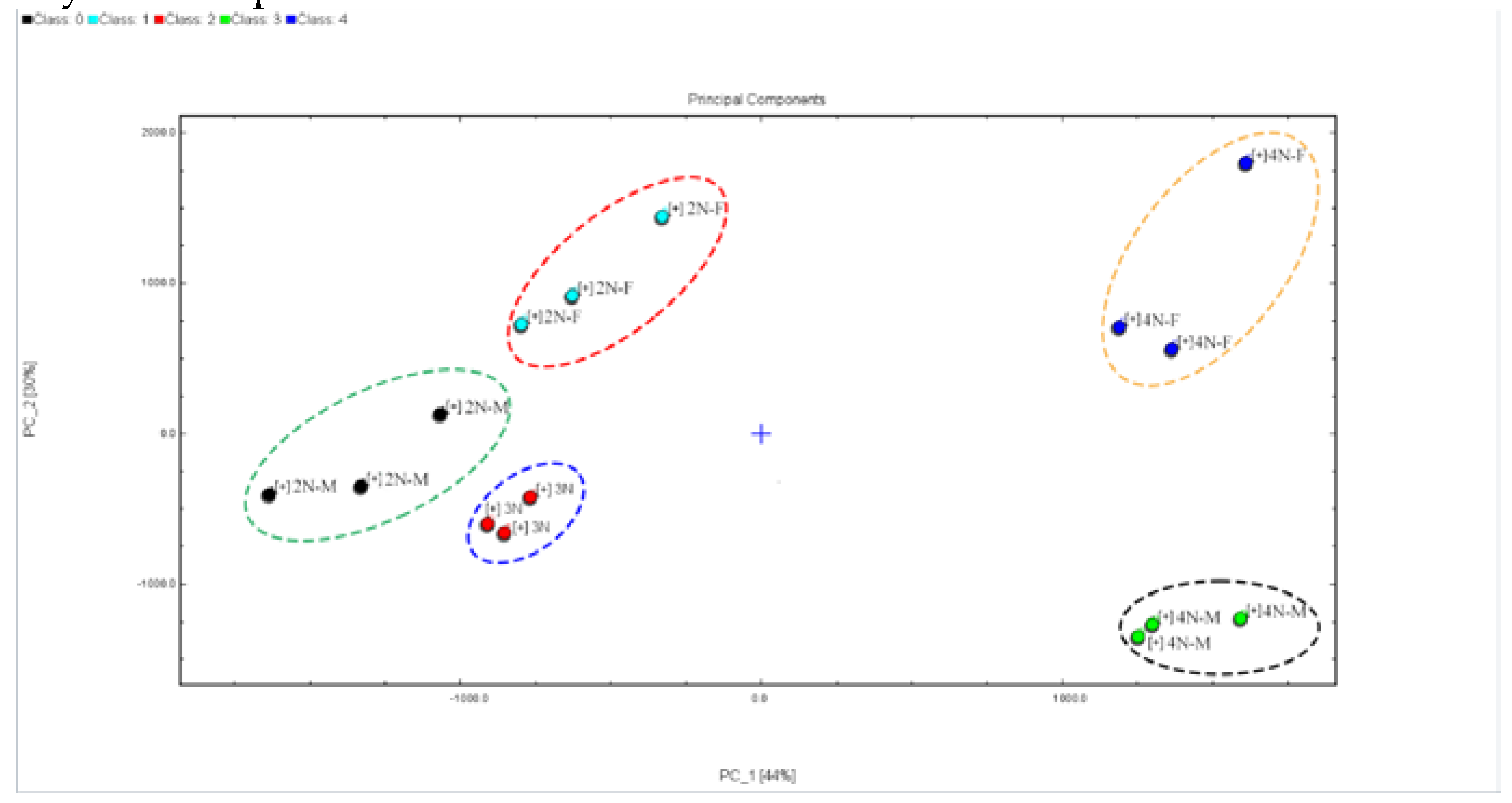

3.4. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of Volatile Compounds Profiles

3.5. Comparison of Volatile Compounds between Different Sexes of Oysters

3.6. Comparison of Volatile Compounds between Different Ploidy Oysters

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zeng, M. In vitro simulated digestion and fermentation characteristics of polysaccharide from oyster (Crassostrea gigas), and its effects on the gut microbiota. Food Res. Int 2021, 149, 110646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, Y. High Hydrostatic Pressure Treatment of Oysters (Crassostrea gigas)—Impact on Physicochemical Properties, Texture Parameters, and Volatile Flavor Compounds. Molecules 2021, 26, 5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felici, A.; Vittori, S.; Meligrana, M.; Roncarati, A. Quality traits of raw and cooked cupped oysters. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, H.; Wu, X.; Xiao, S.; Li, J.; Mo, R.; Yu, Z. Comparison of the biochemical composition and nutritional quality between diploid and triploid Hong Kong oysters, Crassostrea hongkongensis. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Fonseca, B.P.; Góngora-Gómez, A.M.; Muñoz-Sevilla, N.P.; Domínguez-Orozco, A.L.; Hernández-Sepúlveda, J.A.; García-Ulloa, M.; Ponce-Palafox, J.T. Growth and economic performance of diploid and triploid Pacific oysters Crassostrea gigas cultivated in three lagoons of the Gulf of California. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2017, 45, 466–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Xiaoxue, W.; Bin, Z.; Haiqing, T.; Changhu, X.; Jiachao, X. Comparison of taste components between triploid and diploid oyster. J. Ocean Univ. Qingdao 2002, 1, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillet, E.; Panelay, P. Triploidy induction by thermal shocks in the Japanese oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Aquaculture 1986, 57, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Eudeline, B.; Huang, C.; Allen Jr, S.K.; Tiersch, T.R. Commercial-scale sperm cryopreservation of diploid and tetraploid Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas. Cryobiology 2005, 50, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Allen Jr, S.K. Viable tetraploids in the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas Thunberg) produced by inhibiting polar body 1 in eggs. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Allen, S.K., Jr. Reproductive potential and genetics of triploid Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg). Biol. Bull. 1994, 187, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nell, J.A. Farming triploid oysters. Aquaculture 2002, 210, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; DeBrosse, G.A.; Allen, S.K., Jr. All-triploid Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas Thunberg) produced by mating tetraploids and diploids. Aquaculture 1996, 142, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Li, R.; Liao, Q.; Shi, G.; Zhou, Y.; Wan, W.; Li, J.; Ma, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z. Comparison of biochemical composition, nutritional quality, and metals concentrations between males and females of three different Crassostrea sp. Food Chem. 2022, 398, 133868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, R.; Du, X.; Yang, C.; Deng, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, Q. Integrated application of transcriptomics and metabolomics provides insights into unsynchronized growth in pearl oyster Pinctada fucata martensii. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 666, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portillo-López, A.; Gould, M.C.; Stephano, J.L. MAPK is involved in metaphase I arrest in oyster and mussel oocytes. Biol. Cell 2003, 95, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, O.; Johnston, M.A.; Shuster, C.B. Aurora B kinase maintains chromatin organization during the MI to MII transition in surf clam oocytes. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 2648–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, M.; Asturiano, J.F. Reproduction in Aquatic Animals: From Basic Biology to Aquaculture Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Van Houcke, J.; Medina, I.; Linssen, J.; Luten, J. Biochemical and volatile organic compound profile of European flat oyster (Ostrea edulis) and Pacific cupped oyster (Crassostrea gigas) cultivated in the Eastern Scheldt and Lake Grevelingen, the Netherlands. Food Control 2016, 68, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, H.; Jian, S.; Xue, Q.; Lin, Z. Molecular basis of taste and micronutrient content in Kumamoto oysters (Crassostrea sikamea) and Portuguese oysters (Crassostrea angulata) from Xiangshan bay. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 713736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, J.; Mottram, D. Flavour development in meat. Improving the sensory and nutritional quality of fresh meat 2009, 111–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, T.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Chen, G. Study on the volatile profile characteristics of oyster Crassostrea gigas during storage by a combination sampling method coupled with GC/MS. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennarun, A.-L.; Prost, C.; Haure, J.; Demaimay, M. Comparison of two microalgal diets. 2. Influence on odorant composition and organoleptic qualities of raw oysters (Crassostrea gigas). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piveteau, F.; Le Guen, S.; Gandemer, G.; Baud, J.-P.; Prost, C.; Demaimay, M. Aroma of fresh oysters Crassostrea gigas: Composition and aroma notes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 4851–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotfy, S.N.; Fadel, H.H.; El-Ghorab, A.H.; Shaheen, M.S. Stability of encapsulated beef-like flavourings prepared from enzymatically hydrolysed mushroom proteins with other precursors under conventional and microwave heating. Food Chem. 2015, 187, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Song, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, J.; Yu, D. Determination of aroma compounds in pork broth produced by different processing methods. Flavour Fragr. J. 2016, 31, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Pei, Z.; Wei, P.; Xiang, D.; Cao, X.; Shen, X.; Li, C. Volatile flavour components and the mechanisms underlying their production in golden pompano (Trachinotus blochii) fillets subjected to different drying methods: A comparative study using an electronic nose, an electronic tongue and SDE-GC-MS. Food Res. Int 2019, 123, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Liu, X.; Tian, H.; Han, B.; Li, Y.; Tang, C.; Zhu, K.; Li, C.; Meng, Y. Odor-active volatile compounds profile of triploid rainbow trout with different marketable sizes. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 17, 100312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, R.; Cava, R. Volatile profiles of dry-cured meat products from three different Iberian X Duroc genotypes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1923–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duflos, G.; Coin, V.M.; Cornu, M.; Antinelli, J.F.; Malle, P. Determination of volatile compounds to characterize fish spoilage using headspace/mass spectrometry and solid-phase microextraction/gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 600–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No.1 | Compound | CAS# | Formula | MWa | RIb | Rtc | Dtd | Commente |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 20 21 22 23 24 25 28 29 30 31 32 33 36 37 38 41 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 62 63 64 65 67 68 70 73 74 75 76 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 |

(E, Z)-2,6-nonadienal phenylacetaldehyde Propanoic acid Propanoic acid (E)-Non-3-en-2-one (E)-Non-3-en-2-one (E) -2-nonenal (E) -2-nonenal phenylacetaldehyde Benzaldehyde Benzaldehyde (E, E)-2,4-heptadienal p-methyl anisole Furfural 3-(methylsulfanyl)propanal 3-(methylsulfanyl)propanal Furfural (E)-2-octenal (E)-2-octenal (E, E)-2,4-hexadienal (E, E)-2,4-hexadienal 1-nonanal 1-nonanal 1 -hexanol 1 -hexanol 1-Hydroxy-2-propanone 2-Butanone, 3-hydroxy Acetic acid 1-Octen-3-ol 2-Butanone, 3-hydroxy 1-octanal 2-Ethyl-3-methyl pyrazine butyl pentanoate 3-Octanone (Z)-4-heptenal 2-pentyl furan (E)-2-hexen-1-al 3-Methyl-2-butenal Heptaldehyde 1-butanol (Z)-2-Methylpent-2-enal (E)-2-Pentenal (Z)-2-pentenal (E)-3-penten-2-one (E)-2-butenal 1-Penten-3-one 3-Pentanone Ethyl propanoate 2-Butanone Ethyl Acetate 3-Octanone ethyl (E)-2-butenoate 1-Propanol Butanal 1-Pentanol 2-propanone (Z)-4-heptenal 2-Heptanone 2-methyl-2-hepten-6-one 1-Pentanol 2-Nonanone 2,3,5- trimethylpyrazine 1-Butanol, 3-methyl ethyl-butyrate 1-Octen-3-one (E)-2-Heptenal 2-ethyl furan 1-Penten-3-ol 2-butylfuran |

C557482 C122781 C79094 C79094 C18402830 C18402830 C18829566 C18829566 C122781 C100527 C100527 C4313035 C104938 C98011 C3268493 C3268493 C98011 C2548870 C2548870 C142836 C142836 C124196 C124196 C111273 C111273 C116096 C513860 C64197 C3391864 C513860 C124130 C15707230 C591684 C106683 C6728310 C3777693 C6728263 C107868 C111717 C71363 C623369 C1576870 C1576869 C3102338 C123739 C1629589 C96220 C105373 C78933 C141786 C106683 C623701 C71238 C123728 C71410 C67641 C6728310 C110430 C110930 C71410 C821556 C14667551 C123513 C105544 C4312996 C18829555 C3208160 C616251 C4466244 |

C9H14O C8H8O C3H6O2 C3H6O2 C9H16O C9H16O C9H16O C9H16O C8H8O C7H6O C7H6O C7H10O C8H10O C5H4O2 C4H8OS C4H8OS C5H4O2 C8H14O C8H14O C6H8O C6H8O C9H18O C9H18O C6H14O C6H14O C3H6O2 C4H8O2 C2H4O2 C8H16O C4H8O2 C8H16O C7H10N2 C9H18O2 C8H16O C7H12O C9H14O C6H10O C5H8O C7H14O C4H10O C6H10O C5H8O C5H8O C5H8O C4H6O C5H8O C5H10O C5H10O2 C4H8O C4H8O2 C8H16O C6H10O2 C3H8O C4H8O C5H12O C3H6O C7H12O C7H14O C8H14O C5H12O C9H18O C7H10N2 C5H12O C6H12O2 C8H14O C7H12O C6H8O C5H10O C8H12O |

138.2 120.2 74.1 74.1 140.2 140.2 140.2 140.2 120.2 106.1 106.1 110.2 122.2 96.1 104.2 104.2 96.1 126.2 126.2 96.1 96.1 142.2 142.2 102.2 102.2 74.1 88.1 60.1 128.2 88.1 128.2 122.2 158.2 128.2 112.2 138.2 98.1 84.1 114.2 74.1 98.1 84.1 84.1 84.1 70.1 84.1 86.1 102.1 72.1 88.1 128.2 114.1 60.1 72.1 88.1 58.1 112.2 114.2 126.2 88.1 142.2 122.2 88.1 116.2 126.2 112.2 96.1 86.1 124.2 |

1737.5 1691.5 1597.9 1603.6 1611.9 1612.7 1549.9 1550.3 1691.2 1531.9 1529.3 1503.8 1491.9 1484.8 1466.1 1467.4 1484.2 1434.9 1434.9 1411.6 1413.1 1403.7 1404.0 1370.7 1369.5 1313.6 1294.8 1502.6 1479.7 1296.6 1298.7 1426.5 1304.3 1265.7 1254.7 1239.0 1227.3 1211.6 1194.1 1169.8 1157.3 1139.8 1118.0 1105.9 1053.9 1031.9 985.5 961.9 901.0 884.0 1265.2 1150.4 1043.2 896.2 1263.7 843.9 1254.0 1193.4 1351.1 1264.4 1396.2 1393.1 1216.4 1040.9 1321.3 1333.5 957.8 1171.9 1130.9 |

1580.877 1441.904 1195.785 1209.576 1229.733 1231.854 1086.517 1087.265 1441.125 1048.106 1042.566 990.859 967.468 953.925 918.838 921.301 952.694 863.438 863.438 824.042 826.505 811.116 811.731 759.409 757.562 677.539 652.276 988.507 944.205 654.891 657.566 849.028 665.014 598.497 579.319 552.949 534.114 509.799 484.114 450.824 434.743 413.076 387.568 374.154 331.065 315.212 285.945 274.969 248.547 241.637 597.553 426.075 323.287 246.591 594.974 226.112 578.092 483.056 730.198 596.137 799.107 794.156 517.124 321.634 688.033 704.915 273.08 453.687 402.512 |

1.3853 1.25563 1.10796 1.26464 1.37089 1.89675 1.40871 1.96933 1.53643 1.1505 1.46691 1.6172 1.1157 1.08248 1.08564 1.39572 1.33244 1.33086 1.81812 1.1157 1.44793 1.4764 1.94152 1.32611 1.64093 1.2217 1.3317 1.05136 1.1587 1.06375 1.82562 1.16209 1.40639 1.71809 1.14747 1.25109 1.51085 1.35897 1.69822 1.38425 1.48969 1.35223 1.36614 1.35167 1.20029 1.31048 1.35723 1.45295 1.24704 1.33831 1.30973 1.18305 1.11199 1.28862 1.25483 1.11453 1.61885 1.65086 1.17369 1.51151 1.40828 1.16446 1.49232 1.56149 1.67936 1.6689 1.29858 0.94218 1.17811 |

Monomer Monomer Dimer Monomer Dimer Monomer Dimer Dimer Monomer Dimer Monomer Monomer Dimer Dimer Monomer Dimer Monomer Dimer Monomer Dimer Monomer Dimer Dimer Monomer Dimer Monomer Monomer Monomer Dimer Dimer |

| No. | Compound | The peak volume | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2N-M | 2N-F | 4N-M | 4N-F | ||||

| 3 | Propanoic acid | 104.56±3.98b | 122.28±7.57a | - | - | <0.05 | |

| - | - | 300.06±49.44b | 615.37±103.41a | <0.01 | |||

| 13 | p-methyl anisole | 175.79±12.15a | 94.12±11.26a | - | - | <0.01 | |

| - | - | 164.68±15.94a | 112.81±22.24b | <0.05 | |||

| 21 | (E)-2-octenal | 85.89±7.44a | 70.27±10.64b | - | - | <0.05 | |

| - | - | 88.06±6.30a | 80.31±14.13a | 0.435 | |||

| 23 | (E,E)-2,4-hexadienal | 43.16±2.50a | 56.04±7.30a | - | - | <0.05 | |

| - | - | 47.54±10.81a | 45.02±2.52a | 0.728 | |||

| 30 | 1-Hydroxy-2-propanone | 477.89±44.53a | 324.98±53.87b | - | - | <0.05 | |

| - | - | 342.43±28.23b | 551.35±21.73a | <0.01 | |||

| 31 | 2-Butanone,3-hydroxy | 72.97±7.12b | 93.46±8.48a | - | - | <0.05 | |

| - | - | 234.25±55.86a | 155.55±15.99a | 0.079 | |||

| 32 | Acetic acid | 1576.30±5.72b | 1652.99±16.02a | - | - | <0.01 | |

| - | - | 1760.70±45.02a | 1825.28±37.38a | 0.129 | |||

| 36 | 2-Butanone,3-hydroxy | 95.25±6.71b | 129.73±12.40a | - | - | <0.05 | |

| - | - | 235.27±24.64a | 176.28±9.61b | <0.05 | |||

| 43 | 3-Octanone | 465.51±16.49a | 165.57±2.74b | - | - | <0.01 | |

| - | - | 1676.19±155.93a | 450.18±70.83b | <0.01 | |||

| 45 | 2-pentyl furan | 130.04±8.65a | 99.22±13.44b | - | - | <0.05 | |

| - | - | 114.70±21.40b | 163.59±12.81a | <0.05 | |||

| 49 | 1- butanol | 1062.35±26.96b | 1165.43±13.89a | - | - | <0.01 | |

| - | - | 1227.71±80.73b | 1434.19±13.50a | <0.05 | |||

| 56 | 3-Pentanone | 3463.02±33.01a | 2435.40±75.58a | - | - | <0.01 | |

| - | - | 4518.05±266.45a | 3509.57±578.61a | 0.052 | |||

| 57 | Ethyl propanoate | 815.47±52.01b | 2568.56±54.98a | - | - | <0.01 | |

| - | - | 3093.35±40.73b | 3523.66±107.29a | <0.01 | |||

| 58 | 2-Butanone | 745.20±34.15a | 794.30±46.05a | - | - | 0.212 | |

| - | - | 893.98±33.19b | 1112.21±10.28a | <0.01 | |||

| 60 | 3-Octanone | 850.65±37.88a | 417.32±36.7b | - | - | <0.01 | |

| - | - | 1300.20±43.89a | 652.47±111.80b | <0.01 | |||

| 62 | ethyl (E)-2-butenoate | 379.92±68.51a | 308.87±4.05a | - | - | 0.214 | |

| - | - | 284.01±5.25a | 264.81±7.75b | <0.05 | |||

| 64 | Butanal | 330.81±15.83b | 472.97±56.93a | - | - | <0.05 | |

| - | - | 558.10±48.26b | 662.81±35.06a | <0.05 | |||

| 67 | 2-propanone | 2616.37±52.58a | 2328.45±134.30b | - | - | <0.05 | |

| - | - | 3054.40±95.93a | 2775.62±66.91b | <0.05 | |||

| 73 | 2-methyl-2-hepten-6-one | 78.51±6.50a | 67.43±4.05ab | - | - | 0.067 | |

| - | - | 82.51±4.17a | 66.90±5.42b | <0.05 | |||

| 75 | 2-Nonanone | 59.67±4.50a | 44.86±3.27b | - | - | <0.05 | |

| - | - | 54.25±7.59a | 53.33±7.33a | 0.887 | |||

| 82 | (E)-2-Heptenal | 76.38±6.70a | 57.71±6.00b | - | - | <0.05 | |

| - | - | 332.24±18.93a | 116.55±27.76b | <0.01 | |||

| 83 | 2-ethyl furan | 40.83±7.08b | 71.54±2.00a | - | - | <0.01 | |

| - | - | 81.72±2.01b | 95.48±5.88a | <0.05 | |||

| 85 | 2-butylfuran | 15.21±1.43a | 13.14±1.62a | - | - | 0.173 | |

|

TVOCd |

- 27027.36±1521.508a |

- 26771.64±2015.42a |

53.36±6.71a - 34016.38±953.05a |

20.86±9.20b - 34890.89±2916.28a |

<0.01 0.869 0.647 |

||

| No. | Compound | The peak volume | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2N-M | 2N-F | 3N | 4N-M | 4N-F | ||||

| 3 | Propanoic acid | 104.56±3.98c | - | 190.68±30.05b | 300.06±49.44a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 122.28±7.57b | 190.68±30.05b | - | 615.37±103.41a | <0.01 | |||

| 15 | 3-(methylsulfanyl)propanal | 92.75±0.69b | - | 104.51±3.62a | 103.67±5.93a | - | <0.05 | |

| - | 92.71±4.40b | 104.51±3.62a | - | 102.83±0.82a | <0.05 | |||

| 30 | 1-Hydroxy-2-propanone | 477.89±44.53a | - | 311.82±42.53b | 342.43±28.23b | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 324.98±53.87b | 311.82±42.53b | - | 551.35±21.73a | <0.01 | |||

| 31 | 2-Butanone,3-hydroxy-D | 72.97±7.12b | - | 64.33±10.64b | 234.25±55.86a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 93.46±8.48b | 64.33±10.64c | - | 155.55±15.99a | <0.01 | |||

| 32 | Acetic acid | 1576.30±5.72c | - | 1641.73±2.81b | 1760.70±45.02a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 1652.99±16.02b | 1641.73±2.81b | - | 1825.28±37.38a | <0.01 | |||

| 36 | 2-Butanone,3-hydroxy | 95.25±6.71b | - | 90.66±16.97b | 235.27±24.64a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 129.73±12.40b | 90.66±16.97c | - | 176.28±9.61a | <0.01 | |||

| 43 | 3-Octanone | 465.51±16.49c | - | 700.41±42.92b | 1676.19±155.93a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 165.57±2.74c | 700.41±42.92a | - | 450.18±70.83b | <0.01 | |||

| 44 | (Z)-4-heptenal | 111.71±38.42b | - | 100.00±21.30b | 202.99±5.99a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 144.08±37.23b | 100.00±21.30b | - | 244.71±48.97a | <0.01 | |||

| 49 | 1- butanol | 1062.35±26.96b | - | 1129.44±34.33ab | 1227.71±80.73a | - | <0.05 | |

| - | 1165.43±13.89b | 1129.44±34.33b | - | 1434.19±13.50a | <0.01 | |||

| 54 | (E)-2-butenal | 209.26±22.19b | - | 202.55±22.17b | 328.25±25.85a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 278.55±107.07b | 202.55±22.17b | - | 521.75±157.66a | <0.05 | |||

| 56 | 3-Pentanone | 3463.02±33.01b | - | 2957.40±98.31c | 4518.05±266.45a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 2435.40±75.58b | 2957.40±98.31ab | - | 3509.57±578.61a | <0.05 | |||

| 57 | Ethyl propanoate | 815.47±52.01c | - | 1969.56±54.98b | 3093.35±40.73a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 2568.56±54.98b | 1969.56±54.98c | - | 3523.66±107.29a | <0.01 | |||

| 58 | 2-Butanone | 745.20±34.15b | - | 879.82±49.96a | 893.98±33.19a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 794.30±46.05c | 879.82±49.96b | - | 1112.21±10.28a | <0.01 | |||

| 59 | Ethyl Acetate | 532.94±31.52b | - | 593.64±57.28b | 1378.32±360.09a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 1057.36±317.92b | 593.64±57.28b | - | 1636.02±316.90a | <0.01 | |||

| 60 | 3-Octanone-M | 850.65±37.88c | - | 1052.75±32.04b | 1300.20±43.89a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 417.32±36.7c | 1052.75±32.04a | - | 652.47±111.80b | <0.01 | |||

| 62 | ethyl (E)-2-butenoate | 379.92±68.51a | - | 371.75±4.54a | 284.01±5.25b | - | <0.05 | |

| - | 308.87±4.05b | 371.75±4.54a | - | 264.81±7.75c | <0.01 | |||

| 64 | Butanal | 330.81±15.83b | - | 387.23±19.72b | 558.10±48.26a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 472.97±56.93b | 387.23±19.72c | - | 662.81±35.06a | <0.01 | |||

| 67 | 2-propanone | 2616.37±52.58c | - | 2812.23±76.19b | 3054.40±95.93a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 2328.45±134.30b | 2812.23±76.19a | - | 2775.62±66.91a | <0.01 | |||

| 80 | ethyl-butyrate | 14.77±2.37ab | - | 13.38±3.50b | 19.84±1.30a | - | <0.05 | |

| - | 14.09±2.05b | 13.38±3.50b | - | 24.56±6.10a | <0.05 | |||

| 82 | (E)-2-Heptenal | 76.38±6.70c | - | 185.52±12.88b | 332.24±18.93a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 57.71±6.00c | 185.52±12.88a | - | 116.55±27.76b | <0.01 | |||

| 83 | 2-ethyl furan | 40.83±7.08c | - | 59.79±2.36b | 81.72±2.01a | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 71.54±2.00b | 59.79±2.36c | - | 95.48±5.88a | <0.01 | |||

| 84 | 1-Penten-3-ol | 1733.78±17.79b | - | 1821.35±9.59a | 1604.56±20.70c | - | <0.01 | |

| - | 1744.23±8.94b | 1821.35±9.59a | - | 1649.95±25.41c | <0.01 | |||

| TVOC | 27027.36±1521.50b | - | 28222.26±714.81b | 34016.38±953.05a | - | <0.01 | ||

| - | 26771.64±2015.46b | 28222.26±714.81b | - | 34890.89±2916.28a | <0.01 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).