Submitted:

02 May 2023

Posted:

03 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study site and samples collection

2.2. Physico-chemical properties of soil

2.3. Isolation, characterization and screening of isolated rhizobacteria

2.3.1. Total bacterial Count

2.3.2. Colony and cell morphology of isolated rhizobacteria

2.3.3. Gram reaction

2.3.4. Atmospheric Nitrogen (N2) fixing ability

2.3.5. Phosphate solubilization

2.3.6. Biofilm production

2.3.7. Antagonistic activity

2.3.8. Catalase production

2.3.9. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production activity

2.4. Screening and identification of salt tolerance rhizobacteria isolated from spinach growing areas

2.4.1. Screening the of salt resistant rhizobacteria

2.4.2. Potential salt resistant rhizobacterial growth Curve and biomass measurement

2.4.3. Optimization of bacterial fermentation condition under various pH levels

2.4.4. Optimization of carbon and nitrogen (C:N) ratio

2.4.5. Molecular identification (16S rRNA Gene Sequencing) of potential microbes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample collection and, bacterial isolation and characterization from the spinach grown on saline soil

3.1.1. Physio-chemical properties of soil samples

3.1.2. Isolation characterization of salt tolerant rhizobacteria from spinach grown under saline soil

3.1.3. Total bacterial count in rhizosphere

3.1.4. Biochemical characterization

3.1.5. Determination of IAA production

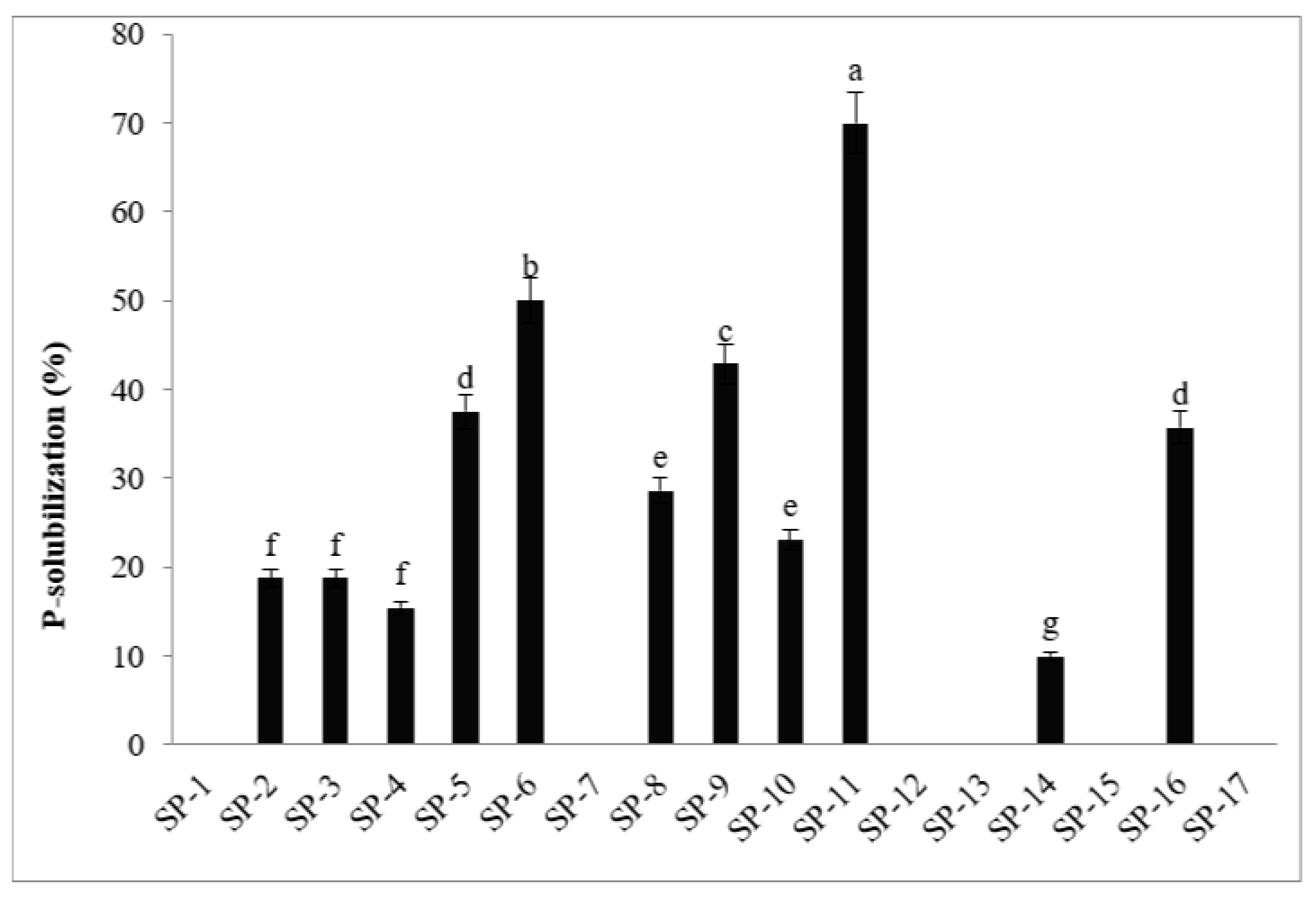

3.1.6. Phosphate solubilizing activities

3.2. Screening and identification of salt tolerance rhizobacteria isolated from spinach growing areas

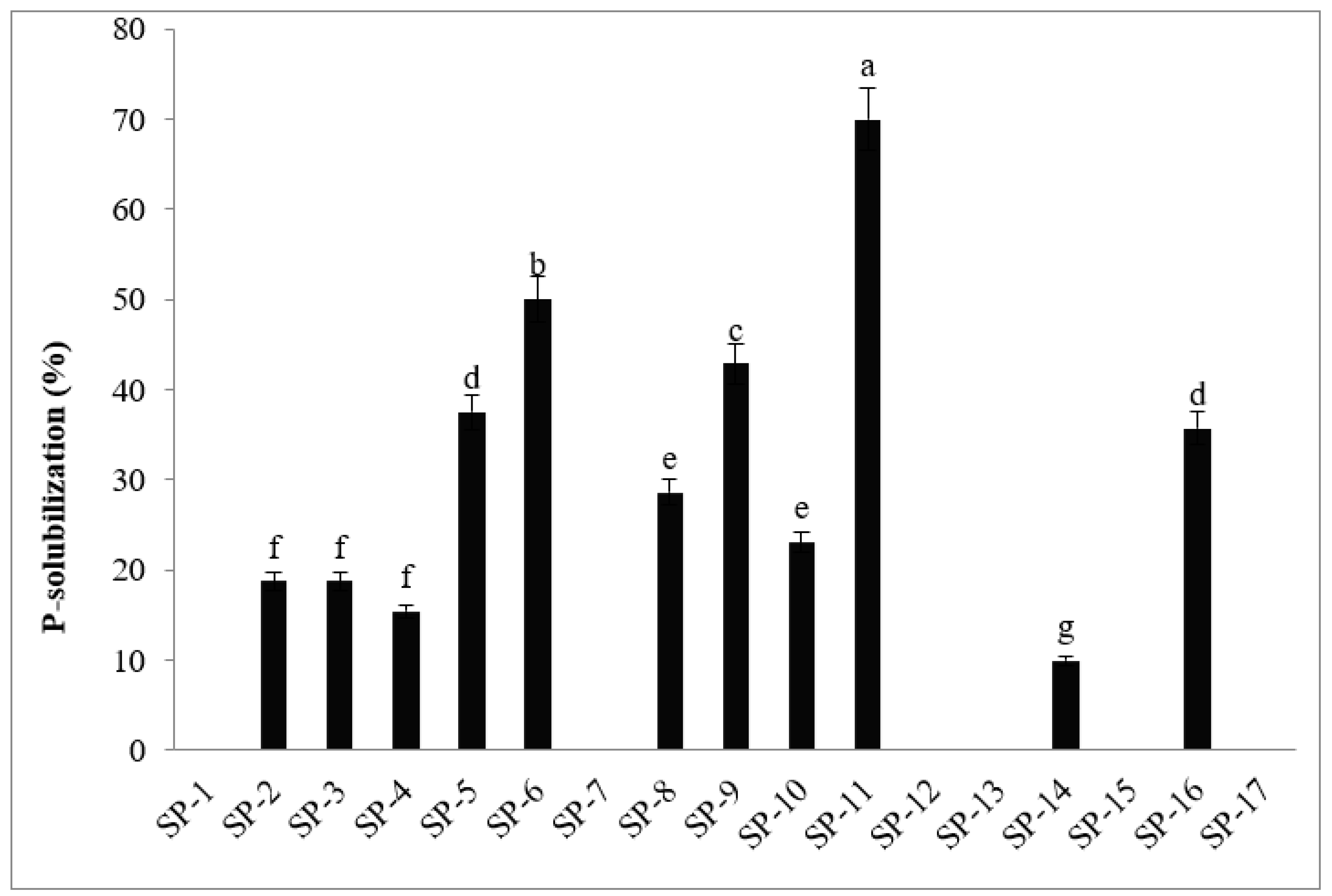

3.2.1. Salt tolerance efficiency of rhizobacteria

3.2.2. Rhizobacteria growth in response to increasing salt (NaCl) concentration

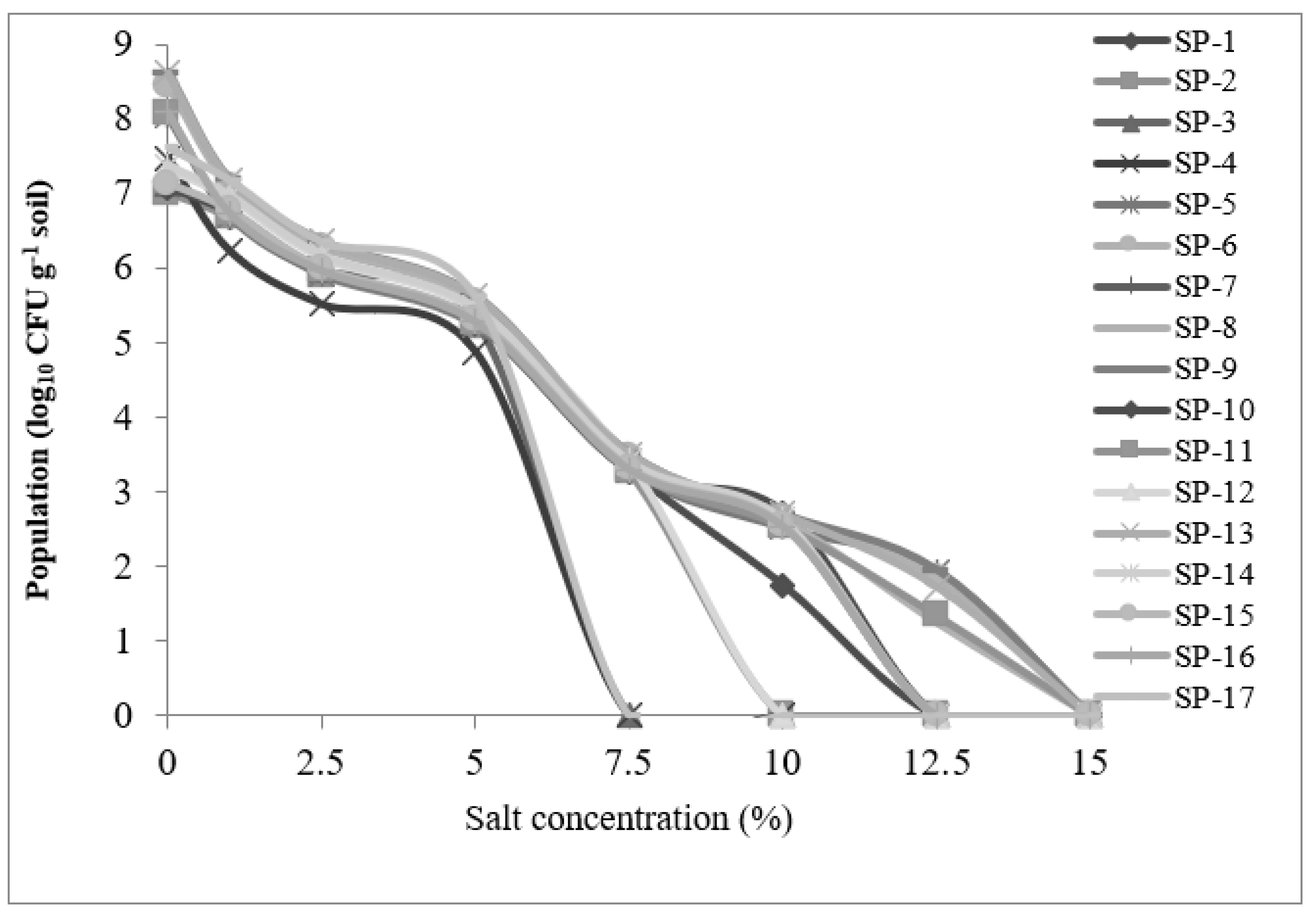

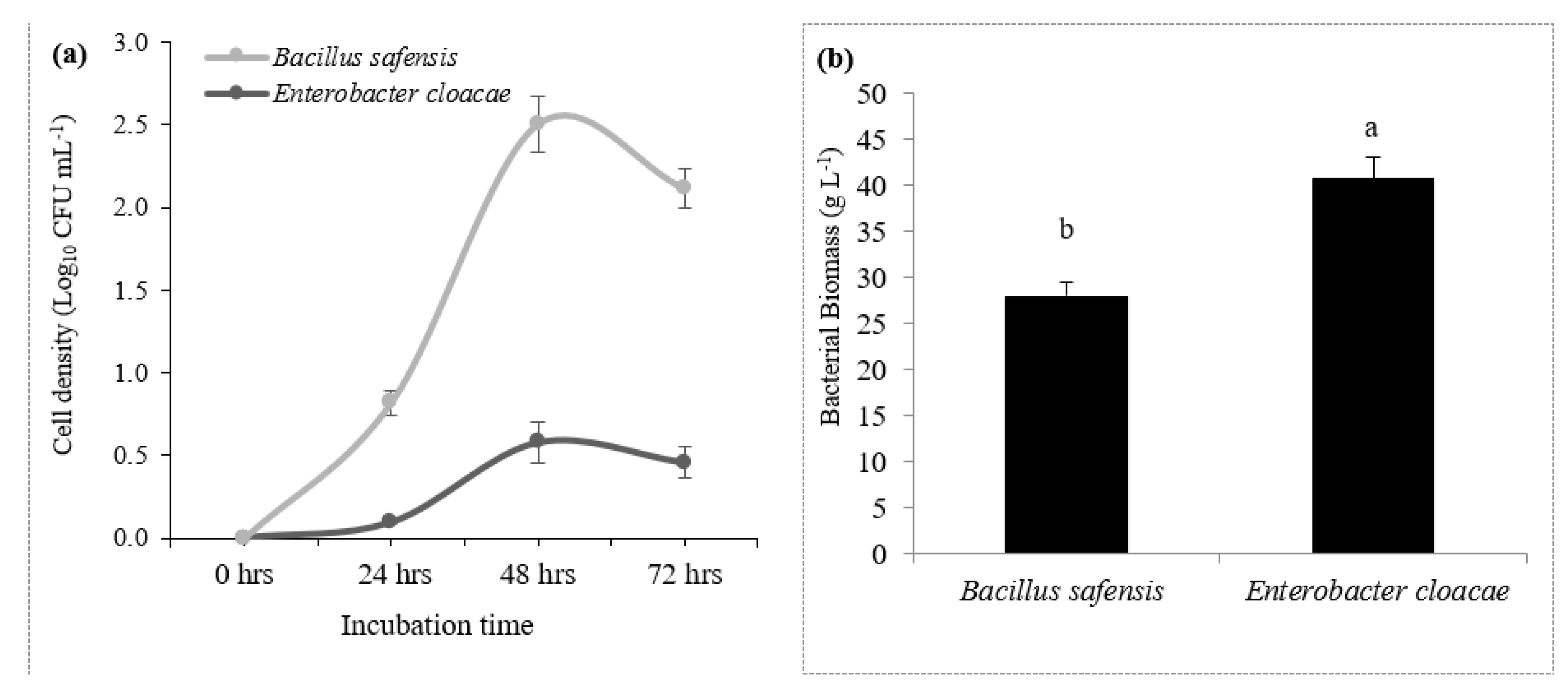

3.2.3. Potential salt resistant rhizobacterial growth curve measurement and bacterial biomass

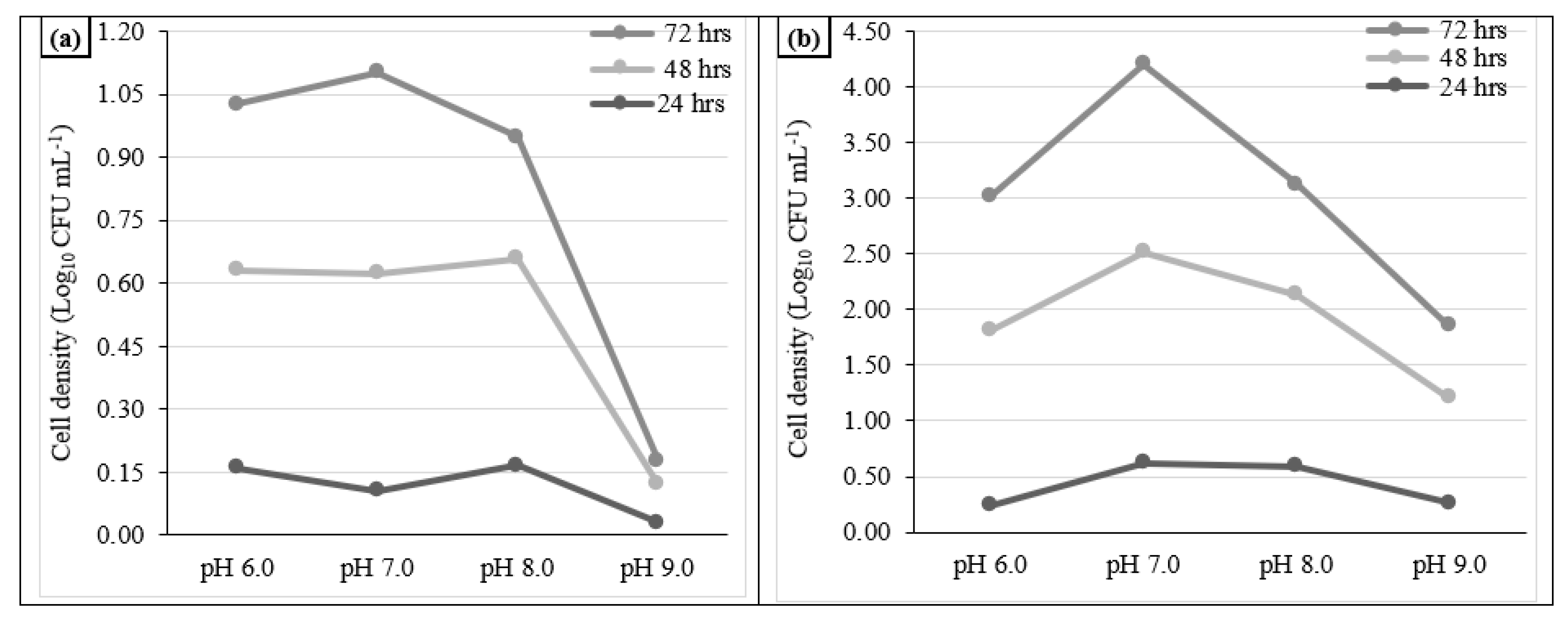

3.2.4. Optimization of bacterial fermentation condition under various pH levels

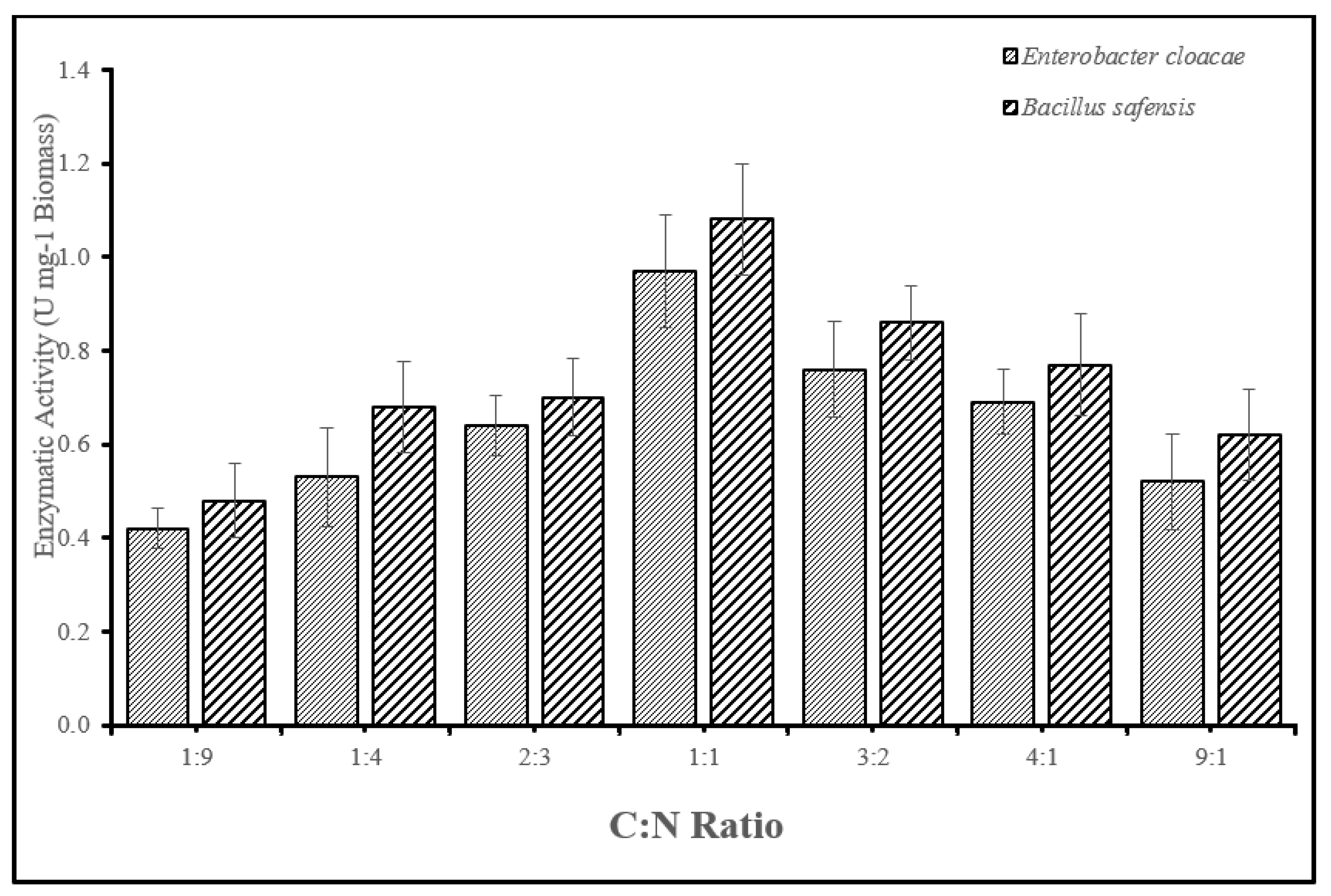

3.2.5. Optimization of carbon and nitrogen ratio

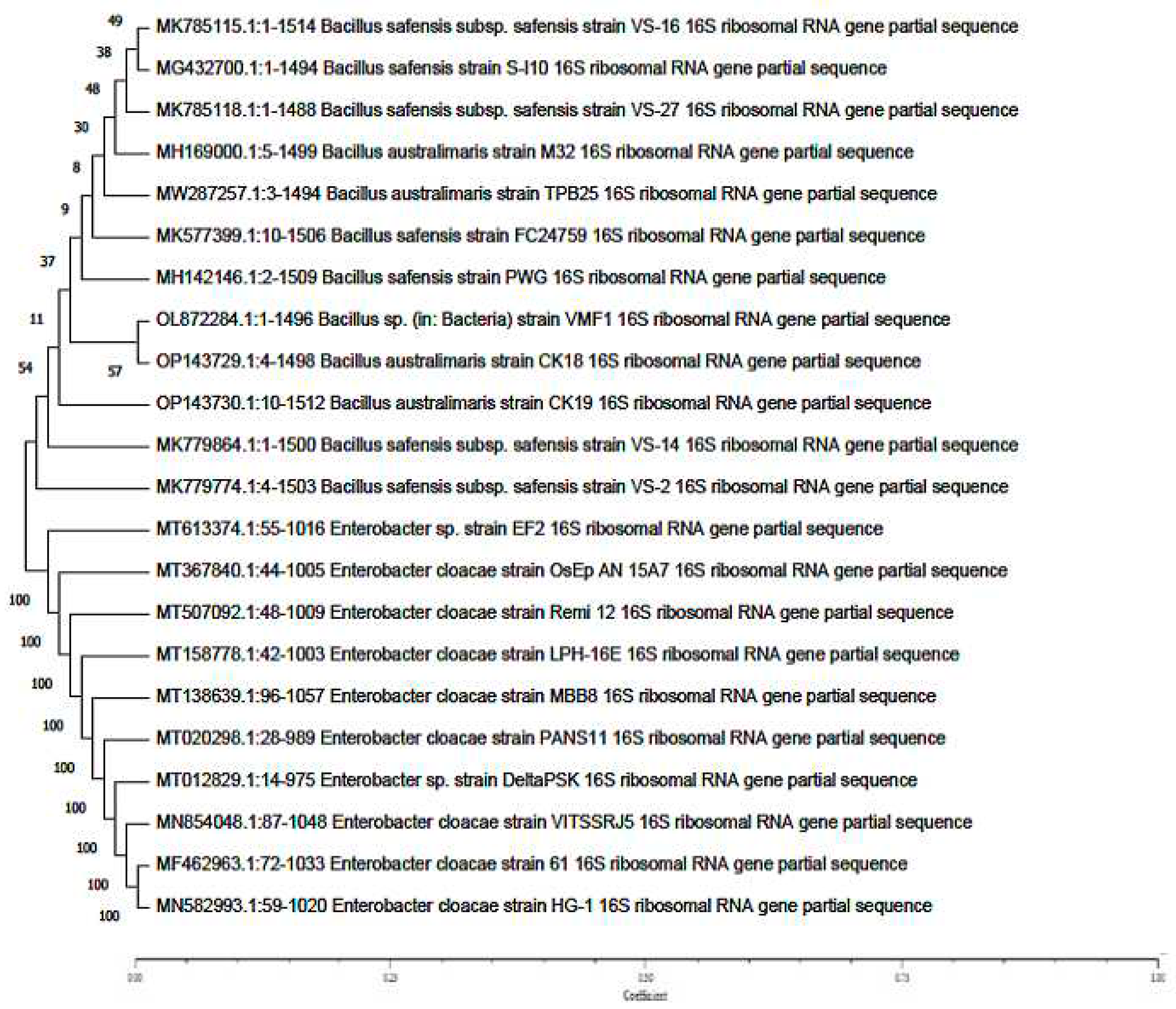

3.2.6. Bacterial identification

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pau, D. Osmotic stress adaptations in rhizobacteria.” J. basic Microbiol. 2013, 53(2), 101-110.

- Nagler, K.;Moeller, R. Systematic investigation of germination responses of Bacillus subtilis spores in different high-salinity environments.” FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015, 91(5), 23. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wan, W.; Luo, X.; Zheng, L.; He, G.; Huang, D.; Chen, W. Huang, Q. “High salinity inhibits soil bacterial community mediating nitrogen cycling.” Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87(21), e1366-21. [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.;Yang, Y.; Guan,P.; Geng, L.; Ma,L.; Hongjie Di; Wenju Liu, Bowen Li. Remediation of organic amendments on soil salinization: Focusing on the relationship between soil salts and microbial communities.” Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety. 2022, 239, 113616. [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, S.M.; Ahmad, M.; Naveed, M., Imran, M., Zahir, Z.A.; Crowley, D.E. Relationship between in vitro characterization and comparative efficacy of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for improving cucumber salt tolerance. Archives Microbiol. 2016, 198, 379–387. [CrossRef]

- Havlin, J.L.; Soltanpour. A. nitric acid plant tissue digest method for use with inductively coupled plasma spectrometry. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1980, 11(10), 969-980. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.; Huang, B. Mechanism of salinity tolerance in plants: physiological, biochemical, and molecular characterization. 2014, 70, 1596. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W., Niu, L.; Wang, P.; Wang, C. The responses of bacterial community and N2O emission to nitrogen input in lake sediment: estrogen as a co-pollutant.” Environ. Res. 2019, 179, 108769. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yu Shi, Xiaoqing Cui, Ping Yue, Kaihui Li, Xuejun Liu, Binu M. Tripathi, Haiyan Chu. Salinity is a key determinant for soil microbial communities in a desert ecosystem. Msystems. 2019, 4(1), e00225-18. [CrossRef]

- Chaparro, J.M.; Dayakar V. B.; Jorge M. Rhizosphere microbiome assemblage is affected by plant development. The ISME J. 2014, 8(4), 790-803.

- Gavrichkova, O.; Brykova, R.A., Brugnoli, E., Calfapietra, C., Cheng, Z., Kuzyakov, Y., Liberati, D., Moscatelli, M.C. Secondary soil salinization in urban lawns: Microbial functioning, vegetation state, and implications for carbon balance. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31(17), 2591-2604. [CrossRef]

- Rath, K.M.; Rousk J. Salt effects on the soil microbial decomposer community and their role in organic carbon cycling: a review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 81, 108–123. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, Q.; Guo, T.; Wang, P. Effect of sodium chloride on the expression of genes involved in the salt tolerance of Bacillus sp. strain “SX4” isolated from salinized greenhouse soil. Open Chem., 2021, 19(1), 9-22.

- Jiao, S.; Lu, Y.H. Abundant fungi adapt to broader environmental gradients than rare fungi in agricultural fields. Global Change Biol. 2020, 26, 8, 4506-4520. [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Song, L.; Yinong X.; Weide G. Drought-tolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria associated with foxtail millet in a semi-arid agroecosystem and their potential in alleviating drought stress. Frontiers Microbiol. 2018, 8, 2580.

- Singh, R.P.; Jha, P.N. The multifarious PGPR Serratia marcescens CDP-13 augments induced systemic resistance and enhanced salinity tolerance of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.).” PLos one. 2016, 11, 6. e0155026. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kulkarni, J.; Jha, B. Halotolerant rhizobacteria promote growth and enhance salinity tolerance in peanut.” Frontiers Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1600. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Ghosh, P.K.; Pramanik, K.; Mitra, S., Soren, T., Pandey, S., Mondal, M.H.; Maiti, T.K. A halotolerant Enterobacter sp. displaying ACC deaminase activity promotes rice seedling growth under salt stress.” Res. Microbiol. 2018, 169(1), 20-32. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, O.; Sharma, R.; Rahi, P.; Karthikeyan, N. Role of microorganisms in plant nutrition and health. Nutrient use efficiency: from basics to advances. 2015, pp. 125–161.

- Microbes, S.; Understanding soil microbes and nutrient recycling. Actinomycetes. 2020, 107, 40–50.

- Glick, B.R.; Gamalero, E. Recent developments in the study of plant microbiomes. Microorganisms. 2021, 9(7), 15-33. [CrossRef]

- Caparrotta, S.; Masi, E; Atzori G.; Diamanti I.; Azzarello E.; Mancuso S.; Pandolfi, C. Growing spinach (Spinacia oleracea) with different seawater concentrations: Effects on fresh, boiled and steamed leaves. Scientia Horticulturae. 2019, 256, 108540. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, M.C.; Grieve C.M. Shannon, M. C., and C. M. Grieve. Tolerance of vegetable crops to salinity. Scientia Horticulturae, 1998, 78(1-4), 5-38.

- Thomas, R.M.; Verma, A.K.; Prakash, C., Krishna, H.; Prakash, S.; Kumar, A. Utilization of Inland saline underground water for bio-integration of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and spinach (Spinacia oleracea). Agri. Water Manage. 2019, 222,154-160. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Bai, X.; Long, J., Li, K.; Xu, H. Nitric oxide enhances the nitrate stress tolerance of spinach by scavenging ROS and RNS. Scientia Horticulturae. 2016, 213, 24–33. [CrossRef]

- Ors, S.; Suarez, D.L. Spinach biomass yield and physiological response to interactive salinity and water stress.” Agri. Water Manage. 2017, 190, 31–41. [CrossRef]

- Ibekwe, A.M.; Ors, S.; Ferreira, J.F.; Liu, X.; Suarez, D.L. Seasonal induced changes in spinach rhizosphere microbial community structure with varying salinity and drought.” Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 1485–1495.

- Çakmakçı, R.; Erat, M.; Erdoğan, Ü.; Dönmez, M.F. The influence of plant growth–promoting rhizobacteria on growth and enzyme activities in wheat and spinach plants. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2007, 170, 288–95. [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Tian, L.; Nasir, F.; Bahadur, A., Batool, A., Luo, S., Yang, F., Wang, Z. and Tian, C. Response of microbial communities and enzyme activities to amendments in saline-alkaline soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 135, 16–24. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qi, L.; Li, W.; Hu, B.X. Dai, Z. Bacterial community variations with salinity in the saltwater-intruded estuarine aquifer. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755,1424. [CrossRef]

- Othman, N.M.I.; Othman, R.; Zuan, A.T.K.; Shamsuddin, A.S.; Zaman, N.B.K.; Sari, N.A.; Panhwar, Q.A. 2022. Isolation, characterization, and identification of zinc-solubilizing bacteria (ZSB) from wetland rice fields in Peninsular Malaysia. Agriculture, 2022, 12, 1823.

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37(1), 29-38. [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.B. Laboratory guide for conducting soil tests and plant analysis. Chemical Rubber Company (CRC) Press, 2001.

- Bouyoucos, G.J. Hydrometer method improved for making particle size analyses of soils 1.” Agron. J. 1962, 54(5), 464-465. [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M.; Mulvaney, C.S. Nitrogen–total. In ‘Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2. Chemical and microbiological properties’, 2nd edn. (Eds A.L. Page; R.H. Miller; D.R. Keeney) pp. 595–624. Soil Science Society of America, Inc. and American Society of Agronomy, Inc.: Madison, WI 1982.

- Havlin, J.L.; Soltanpour. A. nitric acid plant tissue digest method for use with inductively coupled plasma spectrometry. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1980, 11(10), 969-980. [CrossRef]

- Somasegaran, P.; Hoben, H.J. Methods in legume-Rhizobium technology. Paia, Maui: University of Hawaii NifTAL Project and MIRCEN, Department of Agronomy and Soil Science, Hawaii Institute of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, 1985, 1–52.

- Gyaneshwar, P.; James, E.K.; Mathan, N.; Reddy, P.M., Reinhold-Hurek, B.; Ladha, J.K. Endophytic colonization of rice by a diazotrophic strain of Serratia marcescens. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183(8), 2634–2645.

- Pikovskaya, R.I.; Mobilization of phosphorus in soil in connection with vital activity of some microbial species. Mikrobiologiya, 1948, 17, 362–370.

- Nguyen, C.; W. Yan, W.; F. Le Tacon Lapeyrie, F. Genetic variability of phosphate solubilizing activity by monocaryotic and dicaryotic mycelia of the ectomyccorhizal fungus Laccaria bicolor (Maire) P.D. Orton. Plant Soil, 1992, 143, 193–199.

- Watnick, K.; Koltre. Biofilm, City of Microbes. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 2675–79.

- Sariah, M. Potential of Bacillus spp. as biocontrol agent for anthracnose fruit rot of chilli. Malaysian Appl. Biol. 1994, 23, 53–60.

- Serra, B.; Zhang, J., Morales, M.D., de Prada, A.G.V., Reviejo, A.J.; Pingarron, J.M. A rapid method for detection of catalase-positive and catalase-negative bacteria based on monitoring of hydrogen peroxide evolution at a composite peroxidase biosensor. Talanta. 2008, 75(4), 1134–1139. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A.S.; Weber, R.P. Colorimetric estimation of indole acetic acid. Plant physiol. 1951, 26(1), 192.

- Morales-Borrell, D.; González-Fernández, N.; Silva, R.S.; Gómez, E.S. Optimization of fermentation conditions of bacterium Pseudoxanthomonas indica H32.” Biotechnol. Reports. 2021, 32, e00676. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Kable, M.E.; Marco, M.L. Impact of DNA sequencing and analysis methods on 16S rRNA gene bacterial community analysis of dairy products.” Msphere. 2018, 3(5), e00410-18. [CrossRef]

- Weisburg, W.G.; Barns, S.M.; Pelletier, D.A.; Lane, D.J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173(2), 697-703.

- Sadiq, H. M.; Jahangir, G. Z.; Nasir, I. A.; Iqtidar, M.; Iqbal, M. Isolation and Characterization of Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria from Rhizosphere Soil. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equipment. 2014, 27(6), 4248-4255. [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Yang, Y.; Guan, P.; Geng, L.; Ma, L.; Di, H.; Liu, W,; Li, B,; Remediation of organic amendments on soil salinization: Focusing on the relationship between soil salts and microbial communities. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety. 2022, 239, 113616. [CrossRef]

- Naher, U.A.; Biswas, J.C.; Maniruzzaman, M.; Khan, F.H.; Sarker, M.I.U.; Jahan, A.; Hera, M.H.R.; Hossain, M.B.; Islam, A.; Islam, M.R.; Kabir, M.S. Bio-Organic Fertilizer: A Green Technology to Reduce Synthetic N and P Fertilizer for Rice Production. Frontiers Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 152. [Google Scholar]

- Qurashi, A.W.; Sabri, A.N. Osmoadaptation and plant growth promotion by salt tolerant bacteria under salt stress. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2011, 5(21), 3546–3554. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Xiong, X.S.; Yang, Y.Y., Wang, J.J., Wang, M.M., Tang, J.W., Liu, Q.H., Wang, L.; Gu, B. Effects of NaCl concentrations on growth patterns, phenotypes associated with virulence, and energy metabolism in Escherichia coli BW25113. Frontiers Microbiol. 2021, 12, 705326. [CrossRef]

- Abuhena, Md.; Al-Rashid, J.; Azim, M.F.; Morshed, M. N.; Golam Kabidr, M.K.; Barman, N.C.; Rasul, N.M.; Akter, S.; Huq, M.A. Optimization of industrial (3000 L) production of Bacillus subtilis CW-S and its novel application for minituber and industrial-grade potato cultivation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11153. [Google Scholar]

- Shultana, R.; Zuan, A.T.K.; Naher, U.A.; Islam, A.K.M.M.; Rana, M.M.; Rashid, M.H.; Irin, I.J.; Islam, S.S.; Rim, A.A.; Hasan, A.K. The PGPR Mechanisms of Salt Stress Adaptation and Plant Growth Promotion. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.M.; Kumar, R.; Panwar, S.; Kumar, A. Microbial alkaline proteases: Optimization of production parameters and their properties. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2017, 15(1), 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Parameter | Analytical Procedure |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Organic matter | Walkley and Black (1934) method [32] |

| 2. | Soil pH and EC | Soil: water (1:2.5) extract using PHM210 standard pH meter and EC meter [33] |

| 3. | Soil texture | Bouyoucos hydrometer method [34] |

| 4. | Total N | Kjeldahl method [35] |

| 5. | Exchangeable P | Wet digestion [36] |

| 6. | Exchangeable cations (Ca, Mg, Na and K) | Wet digestion [36] |

| No. | Farmer’s Nam | Location | GPS Location | Variety | Method of sowing | Crop Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Muhammad Afzal Khawaja | Khawaja stop | 25°29’32.1”N68°51’15.9”E, | local | Ridge sowing | 30 days |

| 2. | Muhammad Afzal Khawaja | Tando Allahyar | 25°29’51.8”N68°53’04.0”E | local | Ridge sowing | 40 days |

| 3. | Ghulam Mustafa | Awami Markaz road, Nawazabad | 25°30’02.9”N 68°51’14.7”E | local | Ridge sowing | 45 days |

| 4. | Rustam Khawaja | Nawazabad | 25°32’04.4”N 68°52’27.7”E | Hybrid | Ridge sowing | 65 days |

| 5. | Rustam Khawaja | Near Civil Hospital, Sultanabad | 25°28’09.8”N 68°43’15.4”E | local | Ridge sowing | 60 days |

| 6. | Nawaz Khawaja | Village Kamal Khan Mastoi | 25°34’14.0”N 68°49’32.4”E | local | Ridge sowing | 45 days |

| 7. | Shah Nawaz | Village Shah Nawaz | 25°33’19.5”N 68°48’02.2”E | local | Ridge sowing | 50 days |

| 8. | Muhammad Asif | Village DatoKarloo | 25°30’11.1”N 68°47’30.3”E | local | Ridge sowing | 55 days |

| 9. | Muhammad Asif | Village Ghulam Hussain Lund | 25°30’14.6”N 68°45’10.5”E | Hybrid | Ridge sowing | 45 days |

| 10. | Shah Nawaz | Village Kaamaro Sharif | 25°29’09.3”N 68°47’59.7”E | local | Ridge sowing | 50 days |

| 11. | Mubeen Laghari | Village JadoLaghari | 25°27’03.7”N 68°47’31.3”E | local | Ridge sowing | 45 days |

| No. | Farmer’s Name | Location | OM (%) |

EC (dS/m) |

pH | Texture | N (%) |

P (ppm) |

K (ppm) | Ca (mqL-1) |

Na (ppm) |

Mg (mqL-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Muhammad Afzal Khawaja | Khawaja stop | 1.27 | 4.52 | 8.5 | Silty loam | 0.04 | 2.9 | 177 | 40.6 | 0.48 | 60.65 |

| 2. | Muhammad Afzal Khawaja | Tando Allahyar | 0.78 | 8.80 | 8.7 | Clay loam | 0.03 | 3.0 | 158 | 36.0 | 0.47 | 52.03 |

| 3. | Ghulam Mustafa | Awami Markaz road, Nawazabad | 0.92 | 7.36 | 8.8 | Silty clay loam | 0.03 | 2.9 | 105 | 33.24 | 0.43 | 42.61 |

| 4. | RustamKhawaja | Nawazabad | 0.63 | 10.12 | 8.6 | Clay | 0.03 | 2.6 | 120 | 41.23 | 0.49 | 31.23 |

| 5. | Rustam Khawaja | Near civil hospital, Sultanabad | 0.87 | 6.77 | 8.4 | Clay loam | 0.04 | 2.3 | 167 | 34.28 | 0.31 | 45.67 |

| 6. | Nawaz Khawaja | Goth Kamal Khan Mastoi | 0.69 | 7.84 | 8.4 | Silty loam | 0.04 | 3.2 | 156 | 37.71 | 0.37 | 49.15 |

| 7. | Shah Nawaz | Village Shah Nawaz | 1.02 | 3.92 | 8.7 | Silty loam | 0.06 | 3.0 | 177 | 39.76 | 0.34 | 36.74 |

| 8. | Muhammad Asif | Village DatoKarloo | 0.94 | 6.26 | 8.5 | Silty loam | 0.04 | 2.9 | 143 | 40.01 | 0.32 | 14.78 |

| 9. | Muhammad Asif | Village Ghulam Hussain lund | 0.85 | 7.90 | 8.4 | Clay loam | 0.03 | 2.9 | 171 | 35.51 | 0.36 | 38.10 |

| 10. | Shah Nawaz | Village Kaamaro Sharif | 1.20 | 4.52 | 8.6 | Silty clay loam | 0.03 | 2.5 | 124 | 37.32 | 0.37 | 36.54 |

| 11. | Mubeen Laghari | Village Jado Laghari | 1.05 | 5.49 | 8.0 | Silty loam | 0.04 | 2.6 | 161 | 38.13 | 0.35 | 40.14 |

| No. | Farmer’s Name | Location | Total bacteria count (CFU g-1 soil) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Muhammad Afzal Khawaja | Khawaja stop,Tando Allahyar | 12×107c |

| 2. | Muhammad Afzal Khawaja | Khawaja stop,Tando Allahyar | 42×107a |

| 3. | Ghulam Mustafa | Awami Markaz road, Nawazabad | 14×107c |

| 4. | RustamKhawaja | Nawazabad | 2×107e |

| 5. | Rustam Khawaja | Near civil hospital, Sultanabad | 23×107b |

| 6. | Nawaz Khawaja | Goth Kamal Khan Mastoi | 21×107b |

| 7. | Shah Nawaz | Village Shah Nawaz | 11×107c |

| 8. | Muhammad Asif | Village DatoKarloo | 6×107d |

| 9. | Muhammad Asif | Village Ghulam Hussain Lund | 5×107d |

| 10. | Shah Nawaz | Village Kaamaro Sharif | 14×107c |

| 11. | Mubeen Laghari | Village Jado Laghari | 13×107c |

| No. | Isolates | Colony Morphology | Gram Staining | Nitrogen fixing ability | Phosphate- solubilizing ability | Biofilm production | Antagonistic effect (%) | Catalase test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SP-1 | Long rod | -ve | + | - | - | - | + |

| 2 | SP-2 | Rod shape | -ve | + | + | + | - | + |

| 3 | SP-3 | Short rod | +ve | + | + | + | - | +++ |

| 4 | SP-4 | Short rod | +ve | + | + | + | + | - |

| 5 | SP-5 | Short rod | +ve | + | + | + | - | + |

| 6 | SP-6 | Long rod shape | +ve | + | + | - | + | +++ |

| 7 | SP-7 | Short rod shape | +ve | - | - | ++ | - | +++ |

| 8 | SP-8 | Medium rod shape | -ve | + | + | - | +++ | + |

| 9 | SP-9 | Short rod | +ve | + | + | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| 10 | SP-10 | Short rod | +ve | + | + | - | +++ | + |

| 11 | SP-11 | Round | -ve | + | + | + | +++ | + |

| 12 | SP-12 | Round shape | +ve | - | - | + | ++ | +++ |

| 13 | SP-13 | Long rod shape | +ve | - | - | + | + | + |

| 14 | SP-14 | Round shape | +ve | + | + | - | + | - |

| 15 | SP-15 | Long rod shape | +ve | + | + | + | +++ | + |

| 16 | SP-16 | Short rod | +ve | + | + | - | +++ | + |

| 17 | SP-17 | Short rod | +ve | + | - | - | +++ | +++ |

| Note: +ve = positive, -ve = negative | ||||||||

| No. | Strain | Salt concentration (%) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 4 | 5 | 7.5 | 10 | 12.5 | 15 | ||

| 1 | SP-1 | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| 2 | SP-2 | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - |

| 3 | SP-3 | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | SP-4 | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | SP-5 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | - |

| 6 | SP-6 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | - |

| 7 | SP-7 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| 8 | SP-8 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| 9 | SP-9 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | + | - |

| 10 | SP-10 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | - | - |

| 11 | SP-11 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | - |

| 12 | SP-12 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - |

| 13 | SP-13 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | - |

| 14 | SP-14 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| 15 | SP-15 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| 16 | SP-16 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| 17 | SP-17 | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| Note: - Sensitive, + Slightly tolerant, ++ Moderately Tolerant, +++ Tolerant | |||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).