Submitted:

01 May 2023

Posted:

02 May 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM) and Clustering

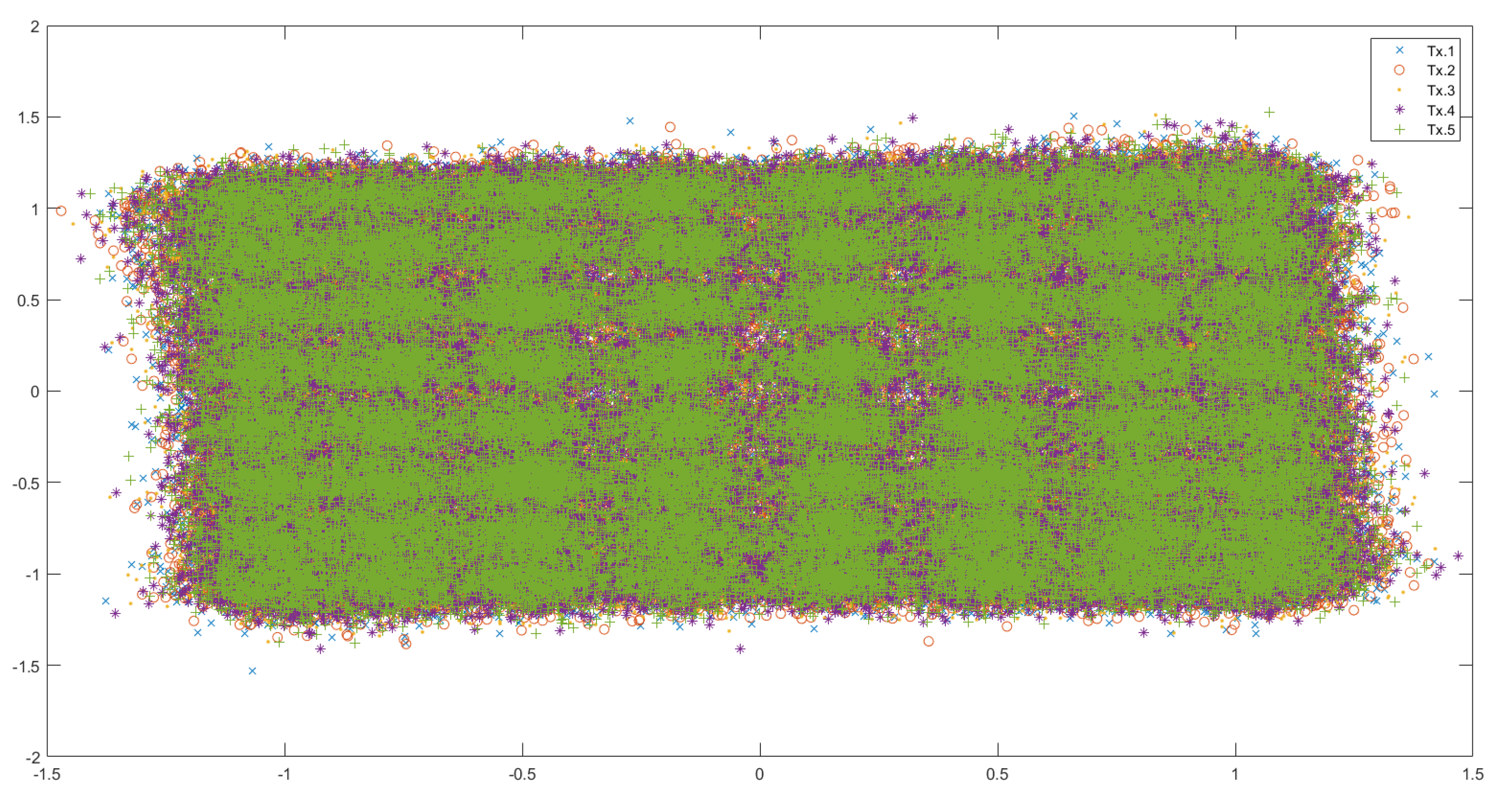

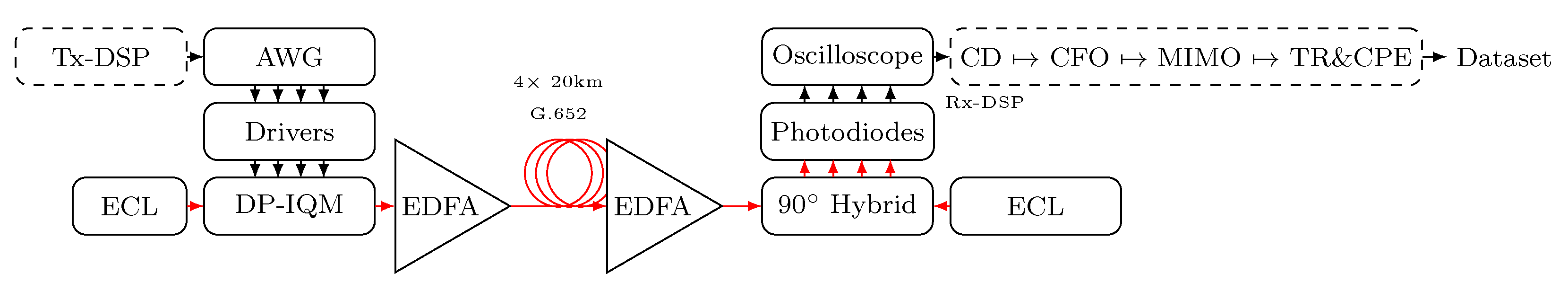

1.2. Experimental Setup for Data Collection

- ’alphabet’: The initial analog values at which the data was transmitted, in the form of complex numbers i.e. for an entry (), the transmitted signal was of the form . Since the transmission protocol is 64-QAM, there are 64 values in this variable. The transmission alphabet is the same irrespective of the channel noise.

- ’rxsignal’: The received analog values of the signal by the receiver. This data is in the form of a matrix. Each datapoint was transmitted 5 times to the receiver, and so each row contains the values detected by the receiver during the different instances of the transmission of the same datapoint. The values in different rows represent unique datapoint values detected by the receiver.

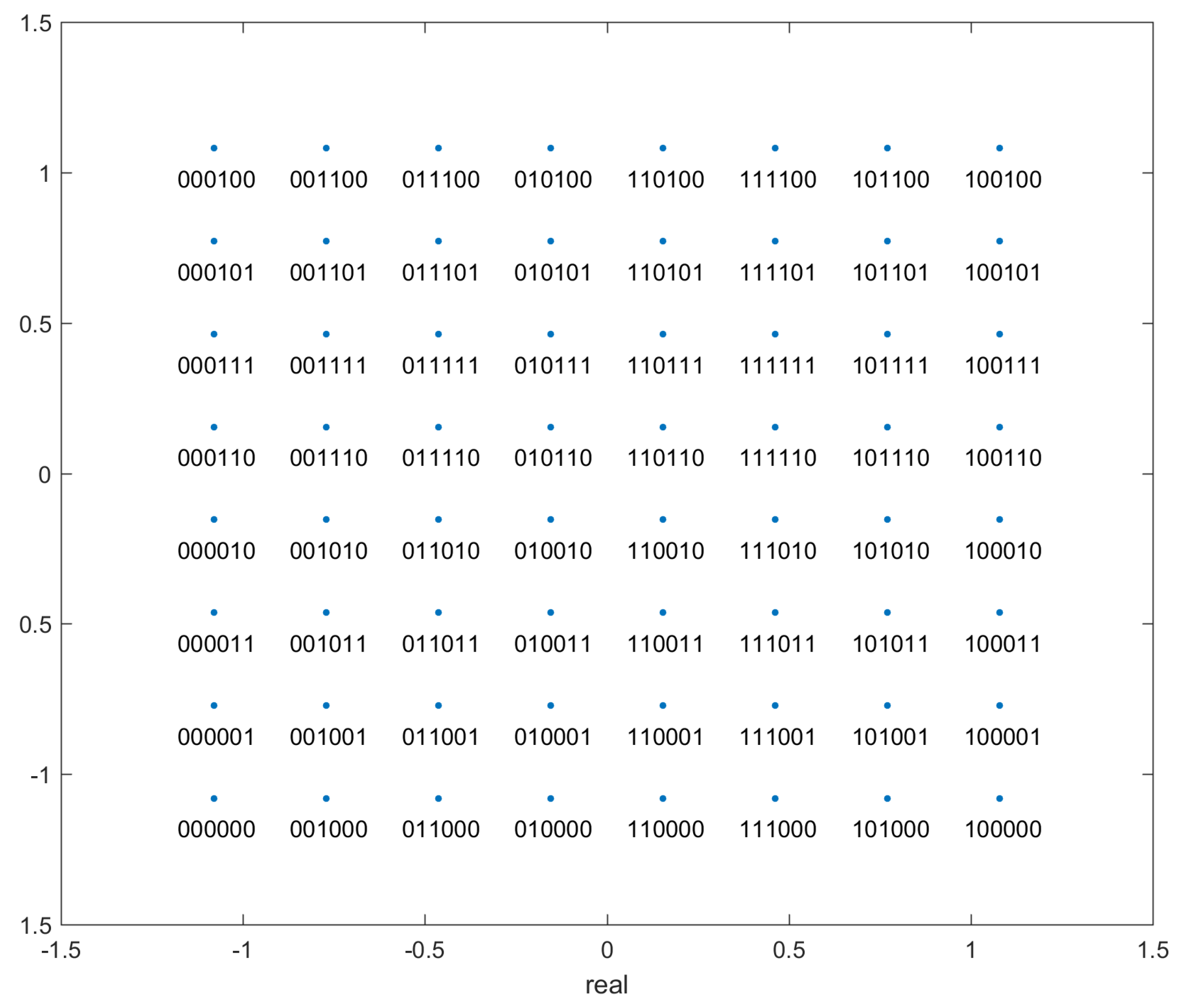

- ’bits’: This is the true label for the transmitted points. This data is in the form of a matrix. Since the protocol is 64-QAM, each analog point represents 6 bits. These 6 bits are the entries in each column, and each value in a different row represents the correct label for a unique transmitted datapoint value. The first 3 bits encode the column and the last 3 bits encode the row - see Figure 2.

1.3. Related Work

1.4. Contribution

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Nearest Neighbour Clustering Algorithm

2.1.1. Dissimilarity Function

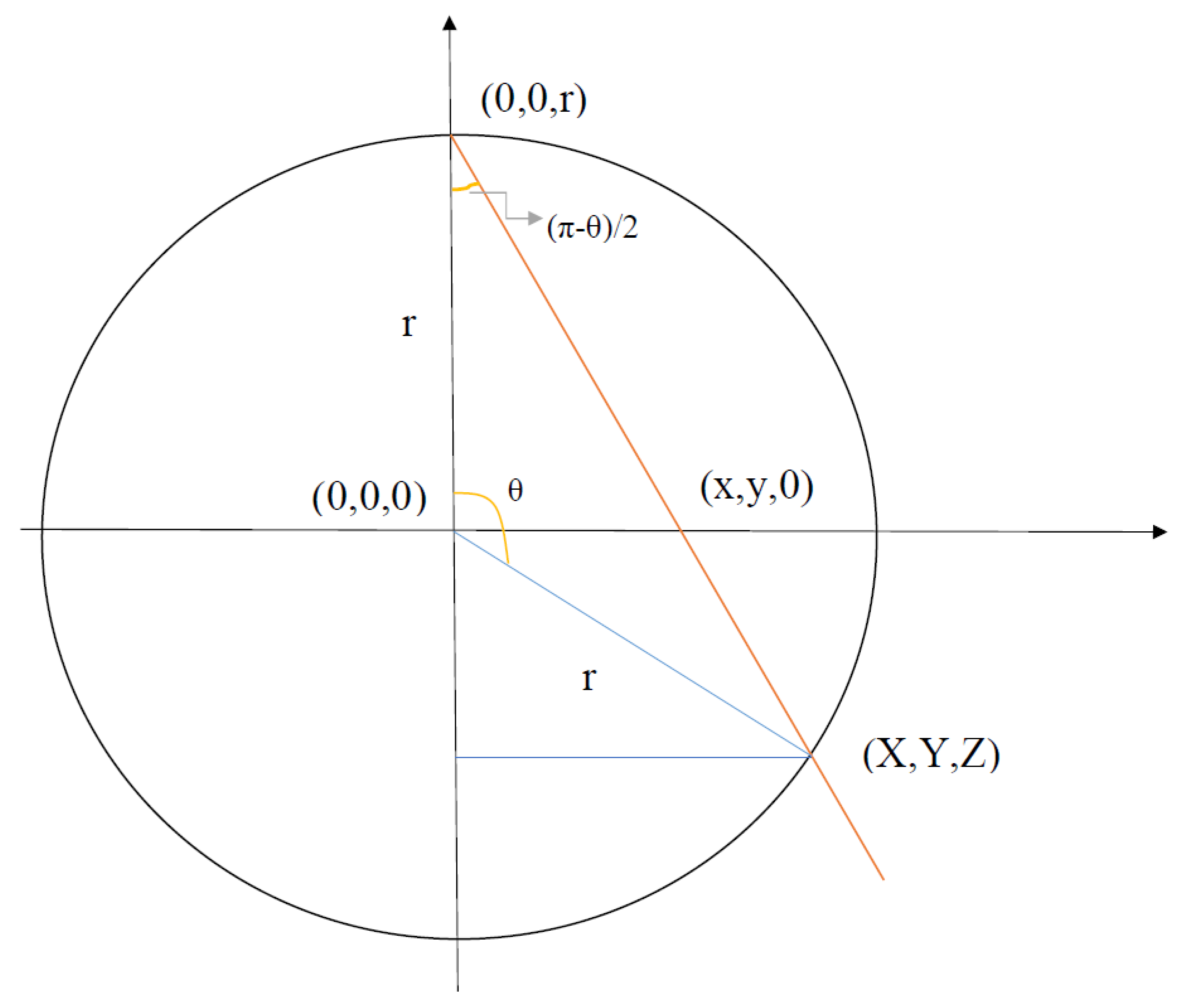

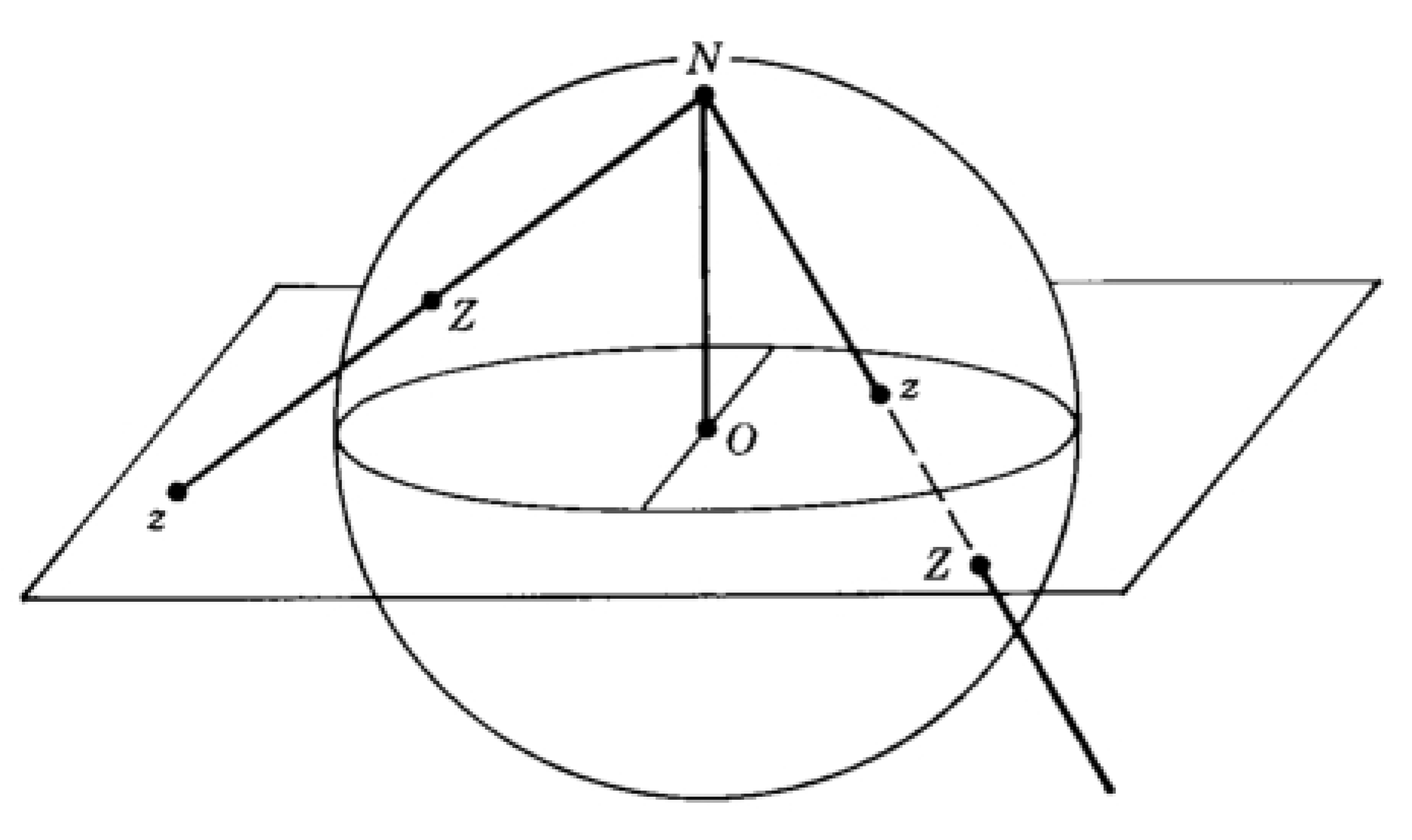

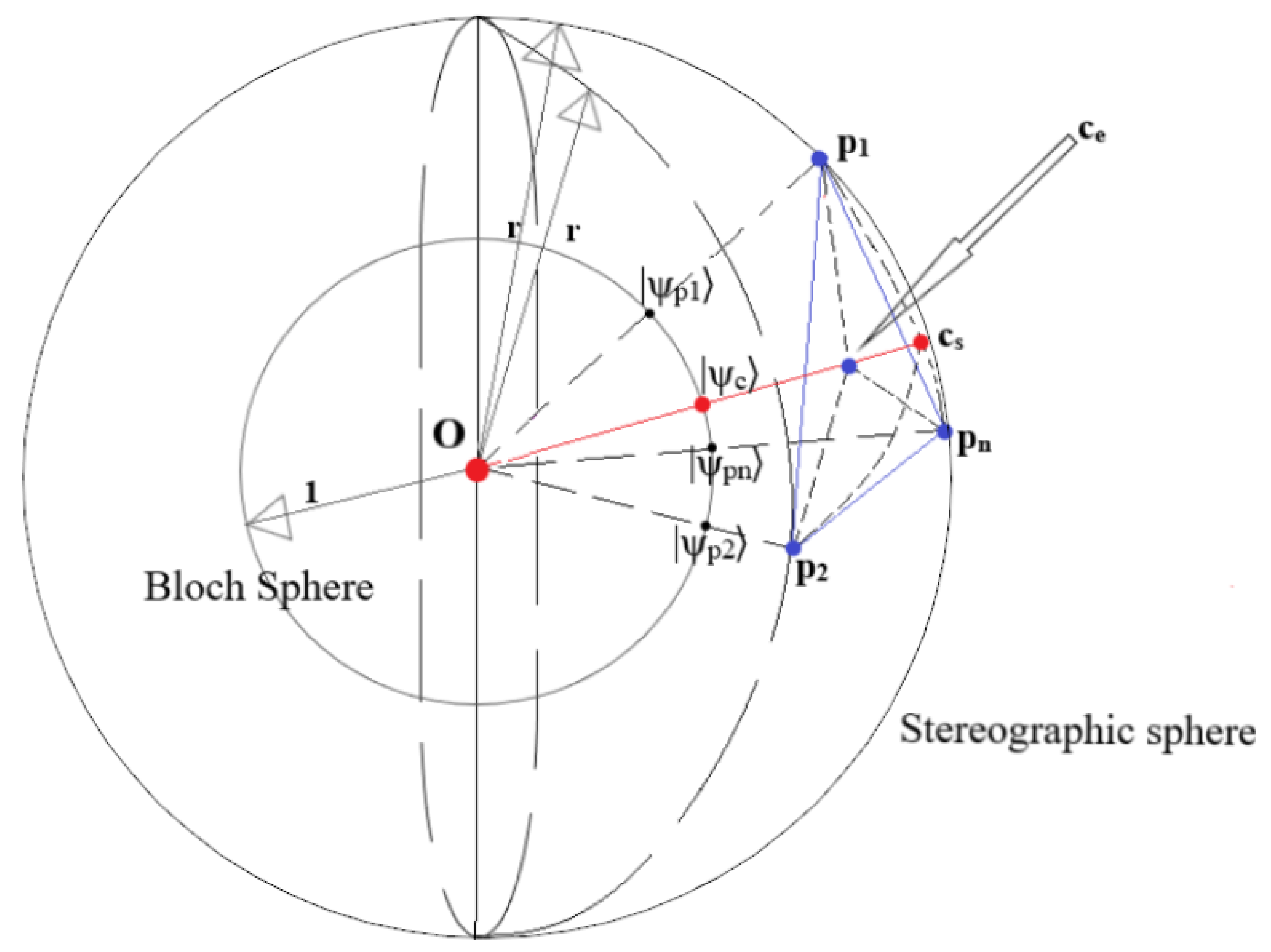

2.2. Stereographic Projection

3. Quantum and Quantum-Inspired k Nearest-Neighbour Clustering Using Stereographic Embedding

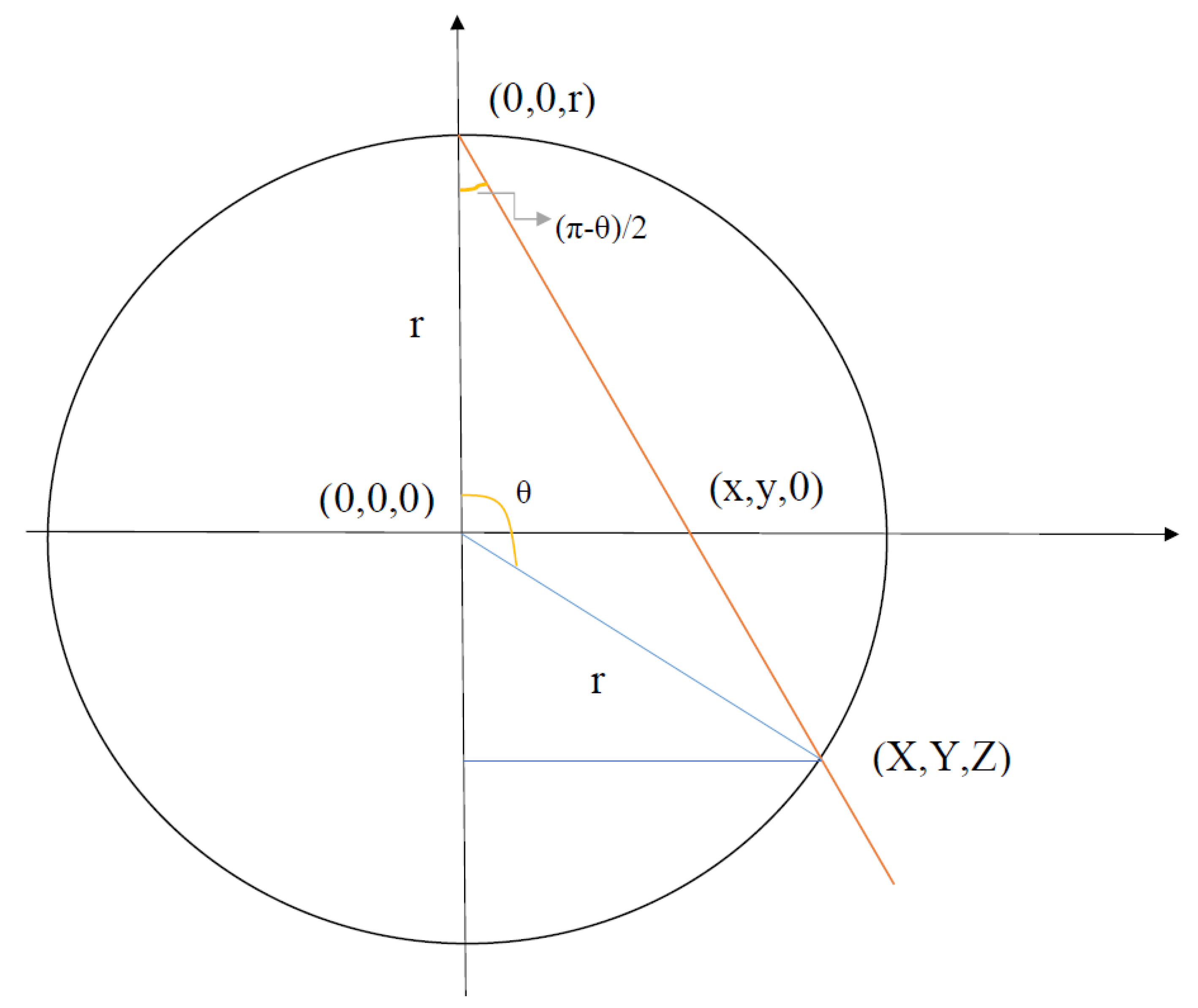

3.1. Stereographic Embedding

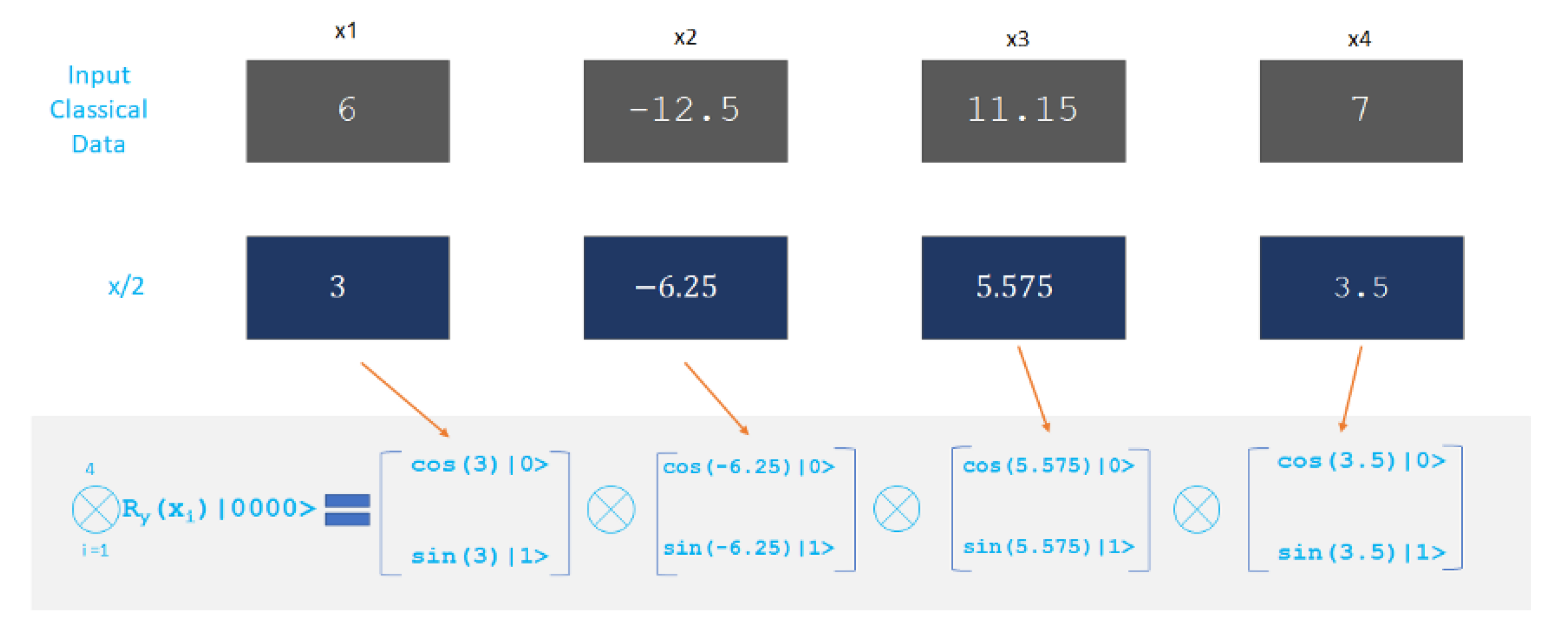

- Then, the computed parameters and are used to map the data points into the Bloch-sphere (pure states of qubits) by performing the unitary operation:

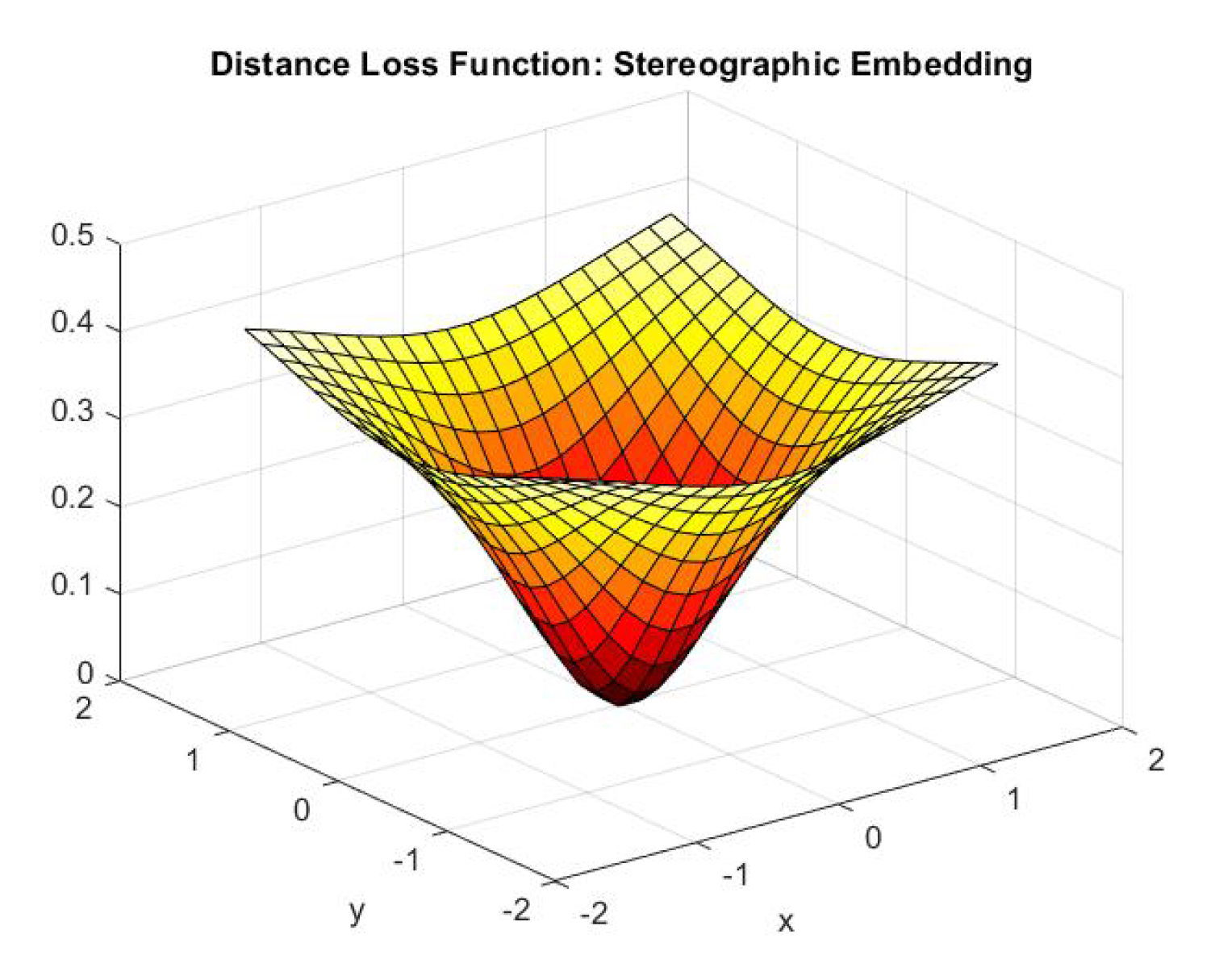

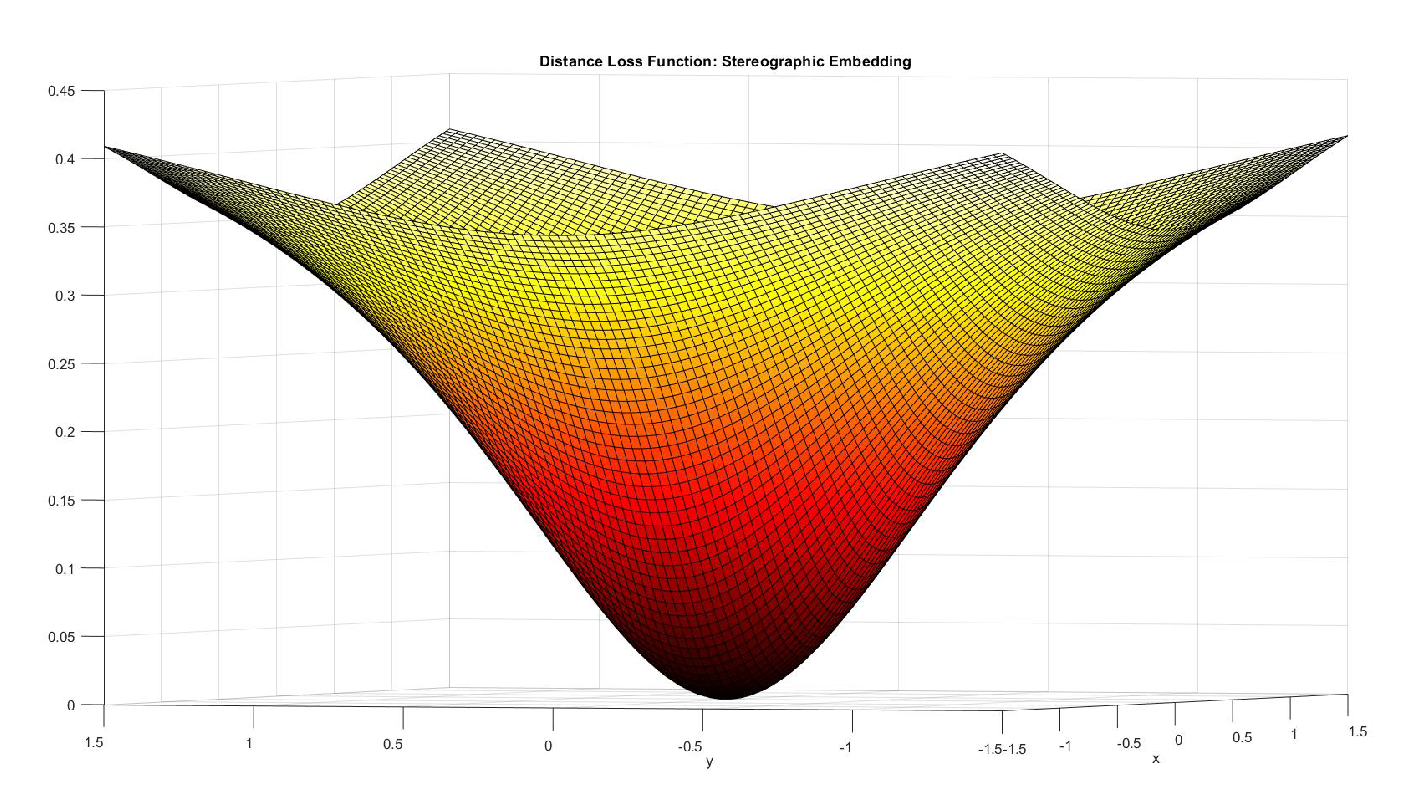

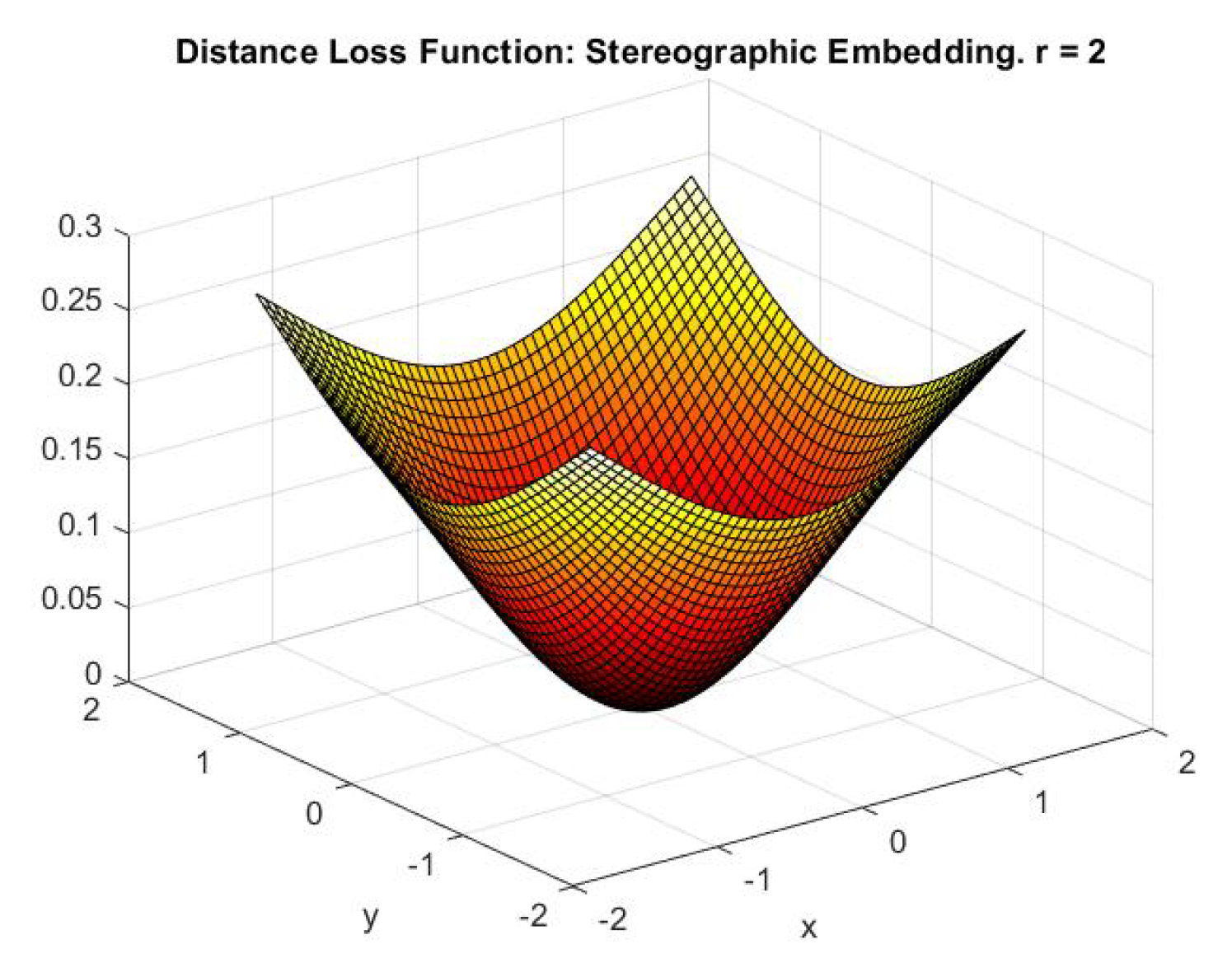

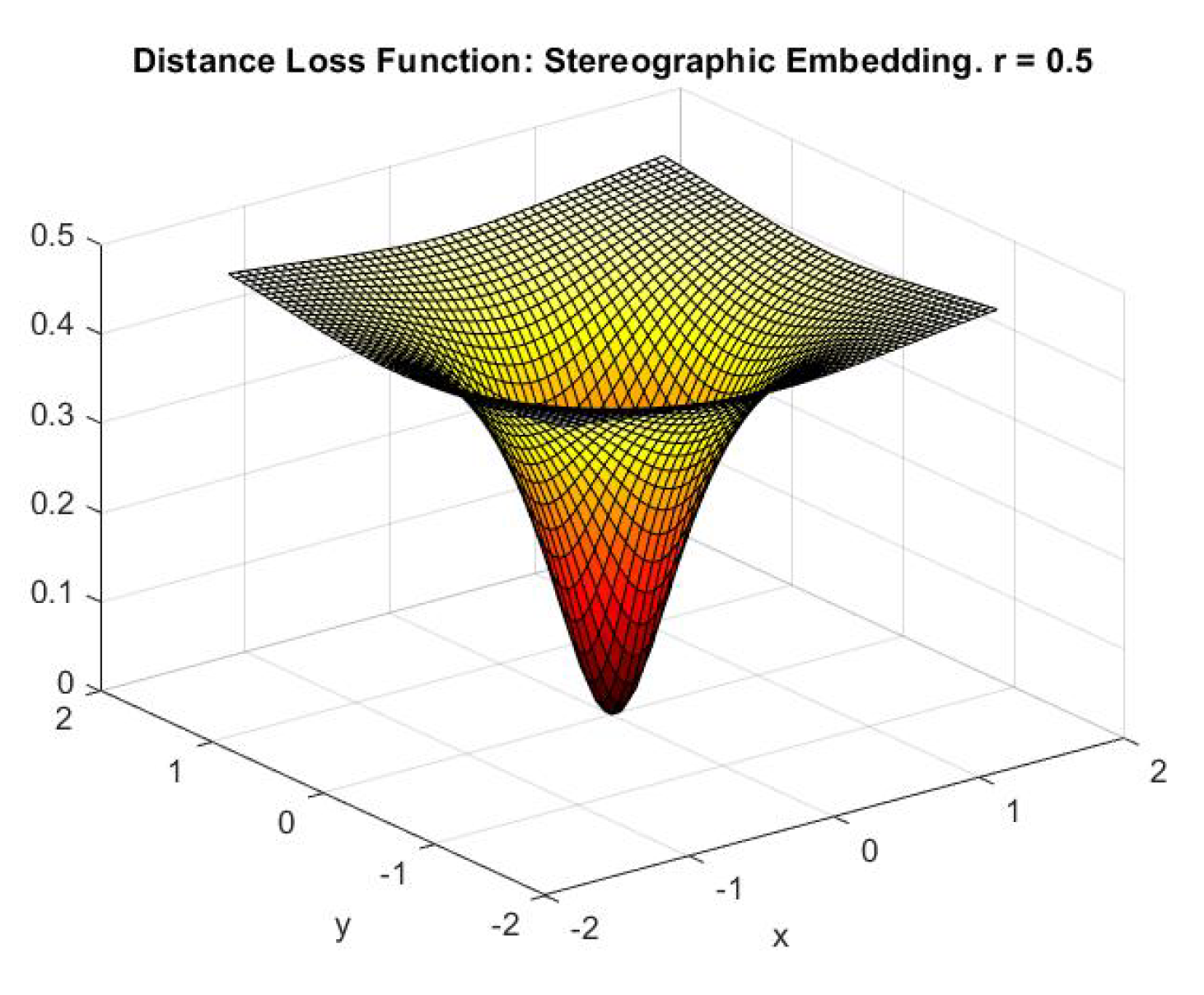

3.2. Computation Engines and Distance Loss Function

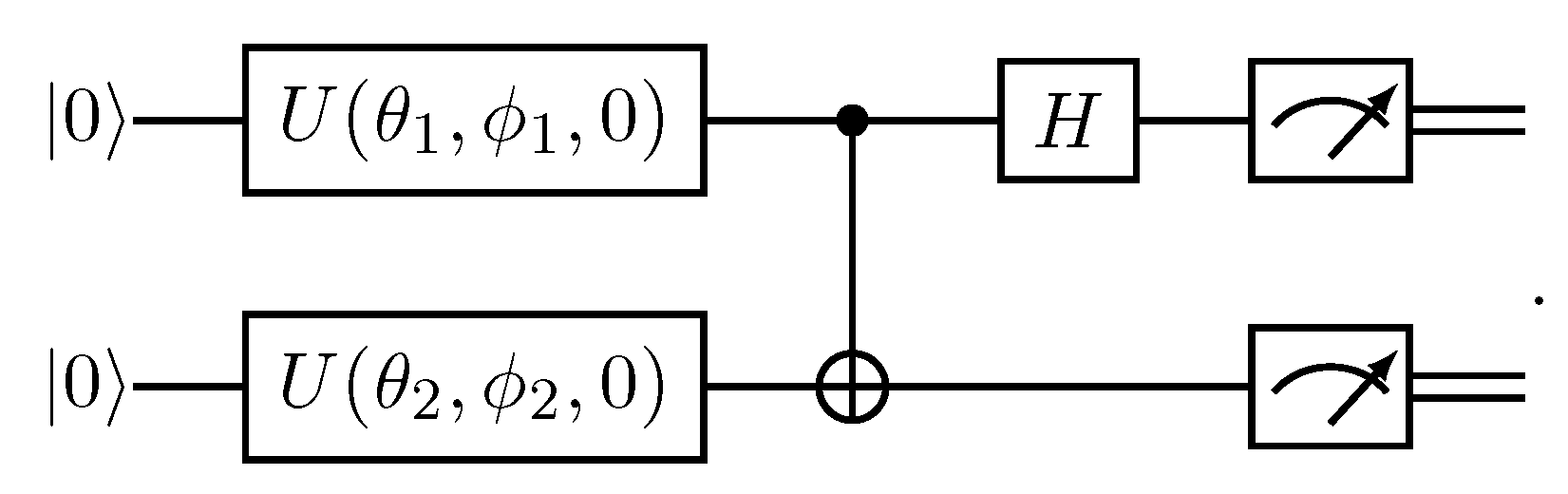

3.2.1. Quantum Circuit Set-Up

3.2.2. Cosine Dissimilarity from the Bell-Measurement Circuit

3.2.3. Distance Loss Function

3.2.4. Summary

- First, prepare to embed the classical data and initial centroids into quantum states using the Generalised Stereographic Embedding procedure: project the 2-dimensional datapoints and initial centroids (in our case, the alphabet) onto a sphere of radius r and calculate the polar and azimuthal angles of the points. The calculated angles will be used to create the states using angle embedding through the unitary U( Equation 28). This first step is executed entirely on a classical computer.

- Cluster Update: The polar and azimuthal angles of the updated centroids are calculated classically. The dissimilarity between the centroid and datapoint is then estimated by using the calculated polar and azimuthal angles to create the quantum state, manipulating the state through the Bell State measurement quantum circuit, and finding the probability of measuring ’1’ on both qubits. This step is entirely handled by the quantum circuit and classical controller. The controller feeds in the classical values at the appropriate times and stores the results of the various shots.

3.3. A Classical Analogue to the Quantum Algorithm

- 1.

- ,

- 2.

- ,

- 3.

- for all .

- Stereographically project all the 2-dimensional data and initial centroids onto the sphere of radius r. Notice that the initial centroids will naturally lie on the sphere.

- Centroid Update: A closed-form expression for the centroid update was calculated in Equation 27 . This expression recalculates the centroid once the new clusters have been assigned. Once the new centroid is updated, Step 2 (cluster update) is then repeated, and so on, until a stopping condition is met.

4. Experiments and Results

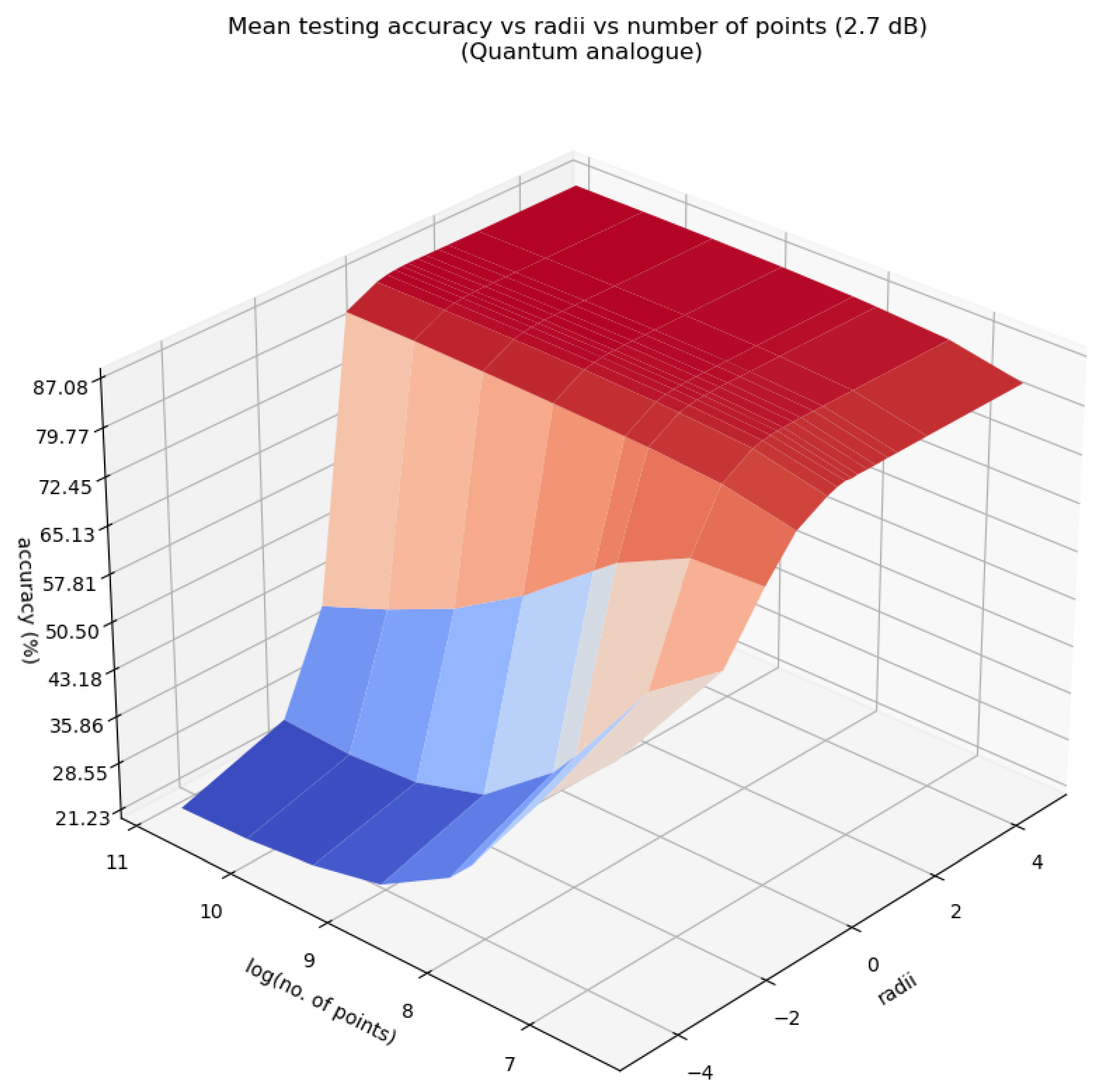

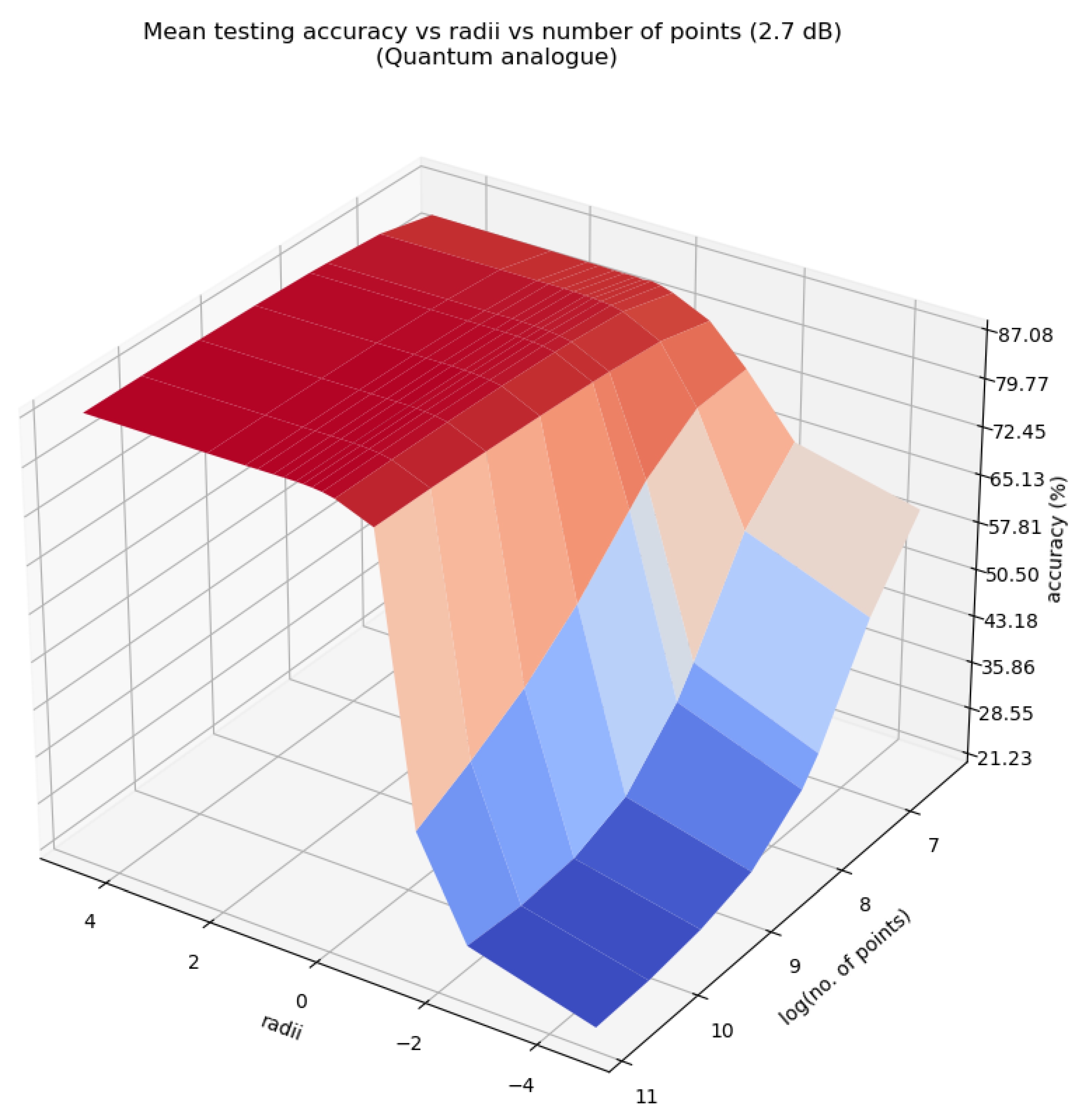

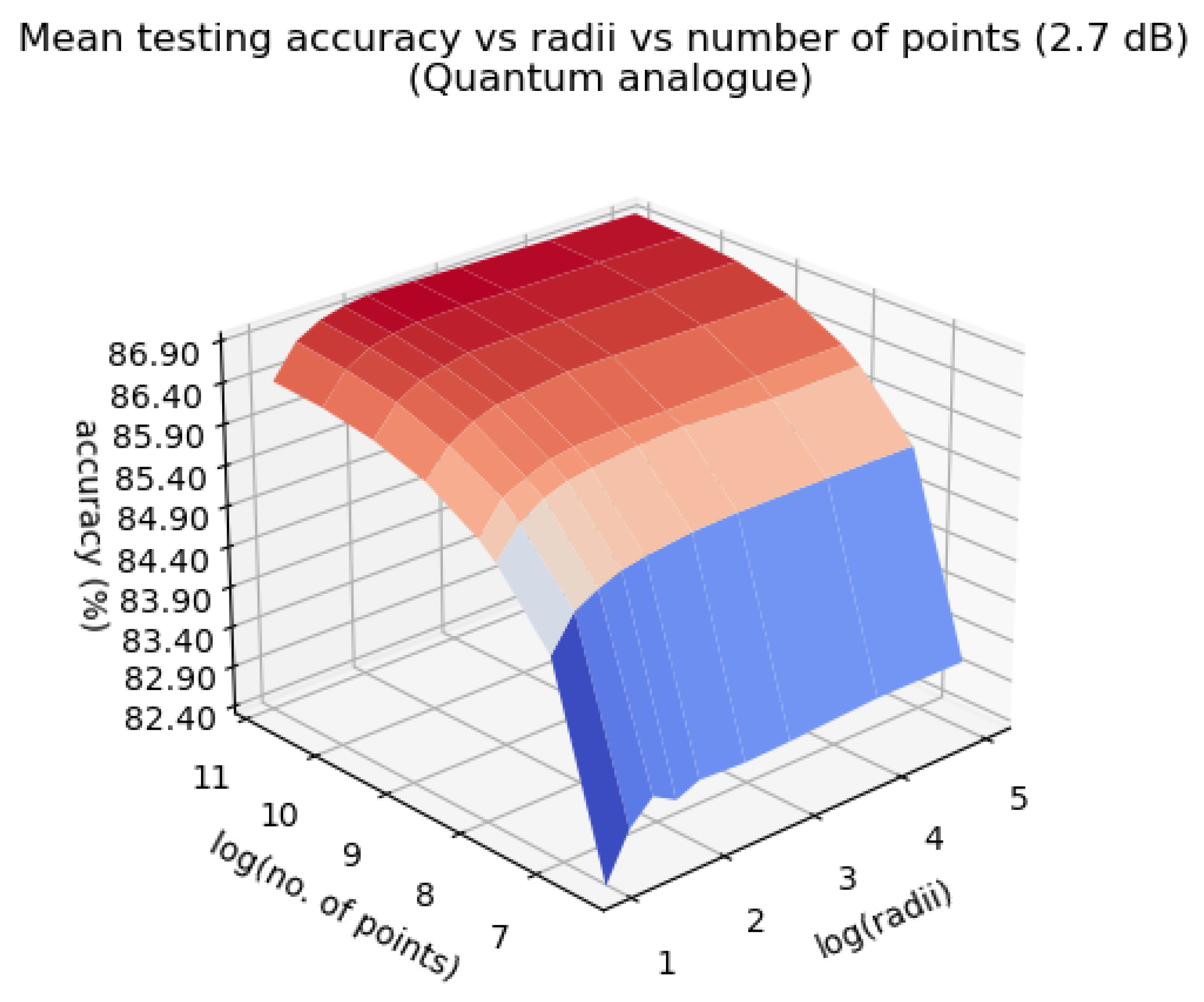

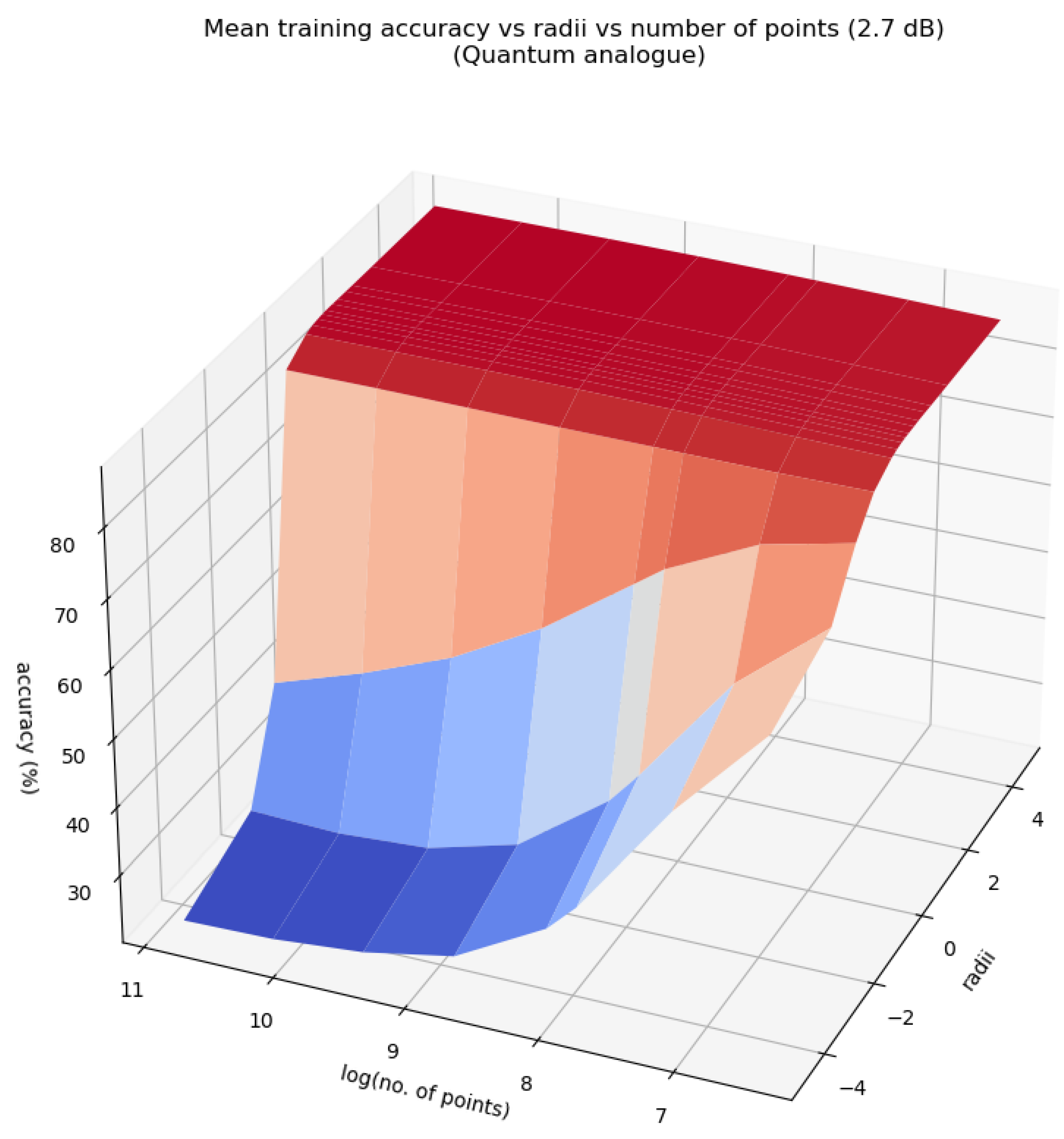

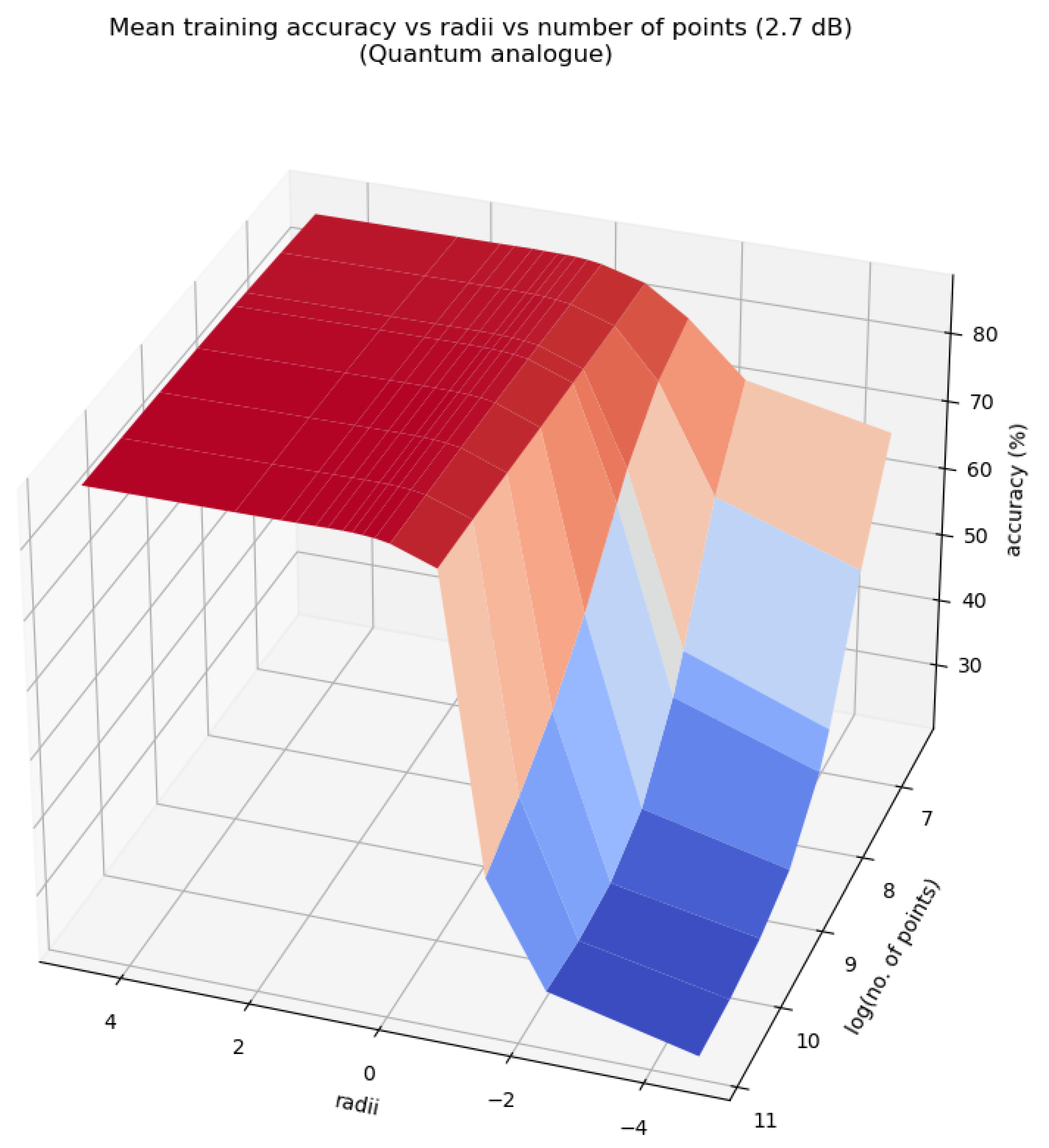

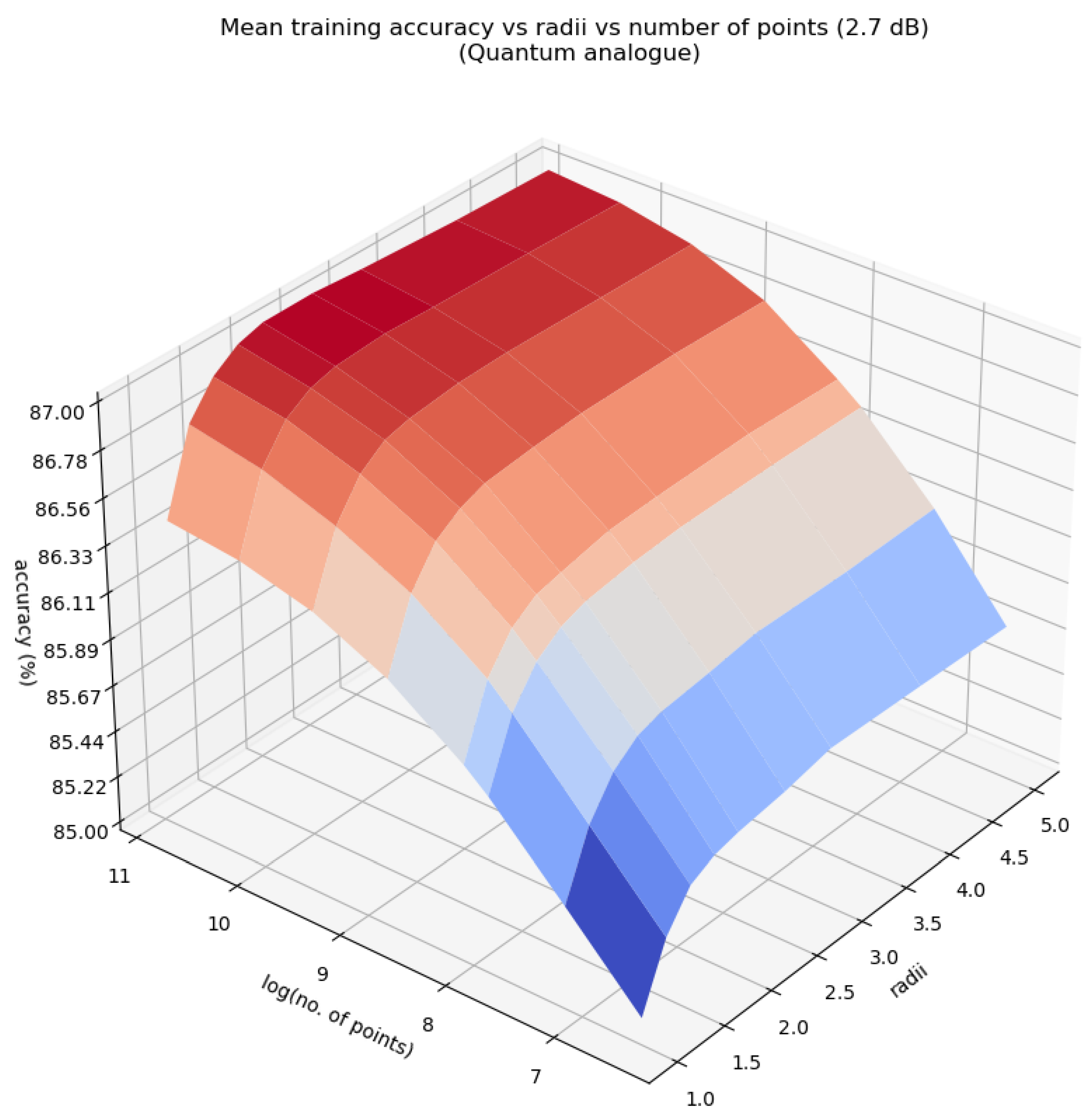

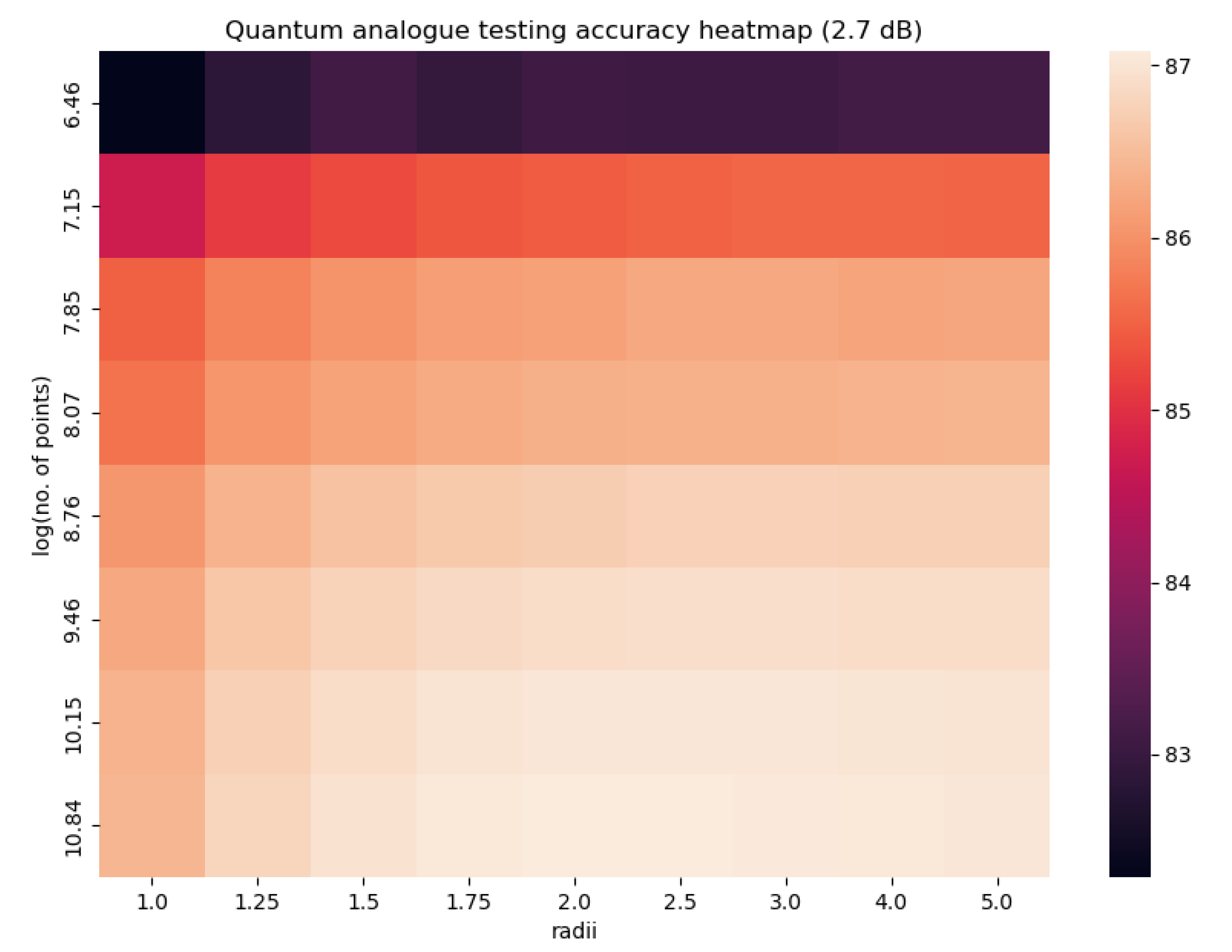

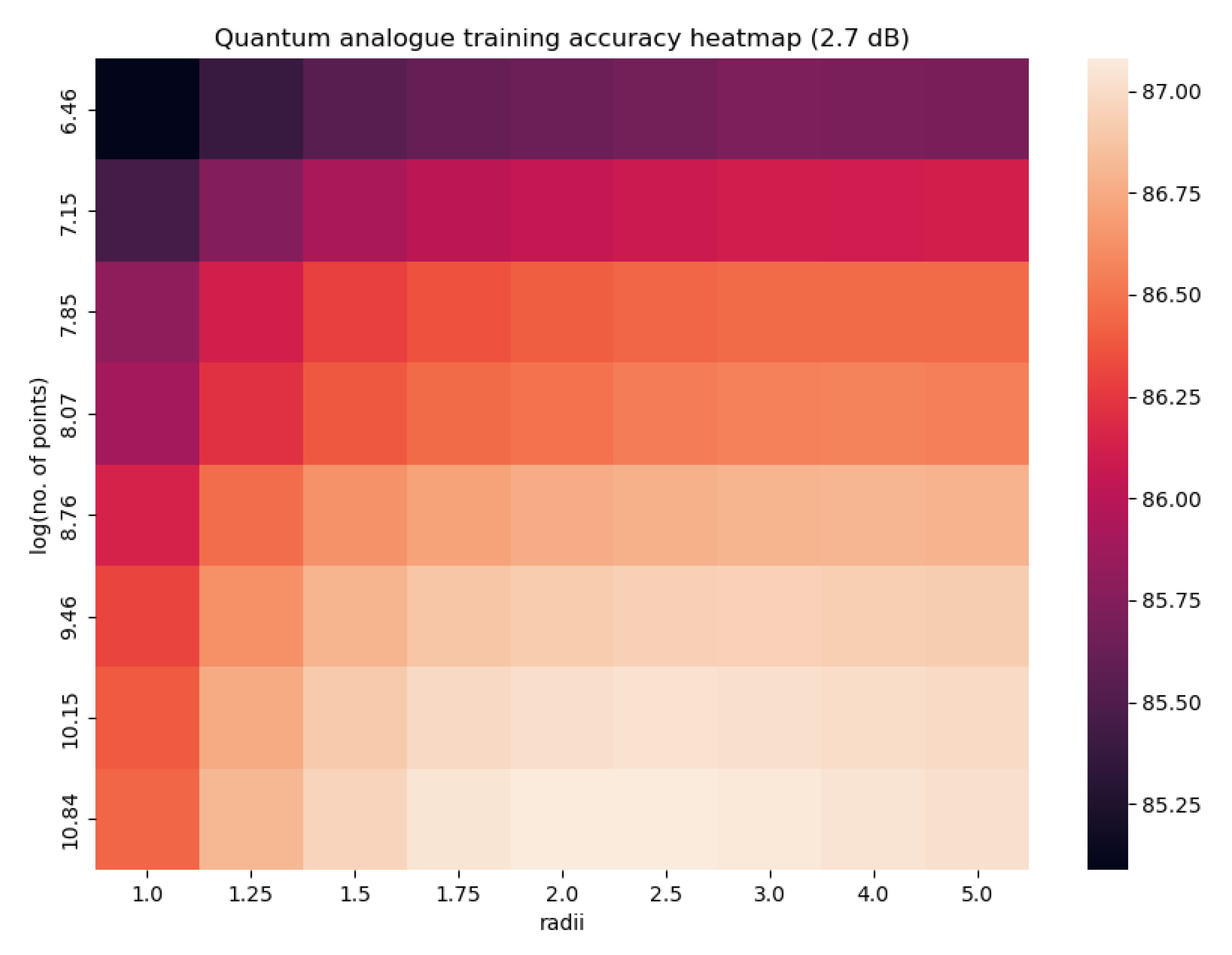

- Radius: the radius of the stereographic sphere onto which the 2-dimensional points are projected.

- Number of points: the number of points upon which the clustering algorithm was performed. For every experiment, the selected points were a random subset of all the 64-QAM data (of a specific noise) with cardinality equal to the required number of points.

- Accuracy: The symbol accuracy rate. As mentioned before, due to Gray encoding, the bit error rate is approximately of the symbol error rate. All accuracies are recorded as a percentage.

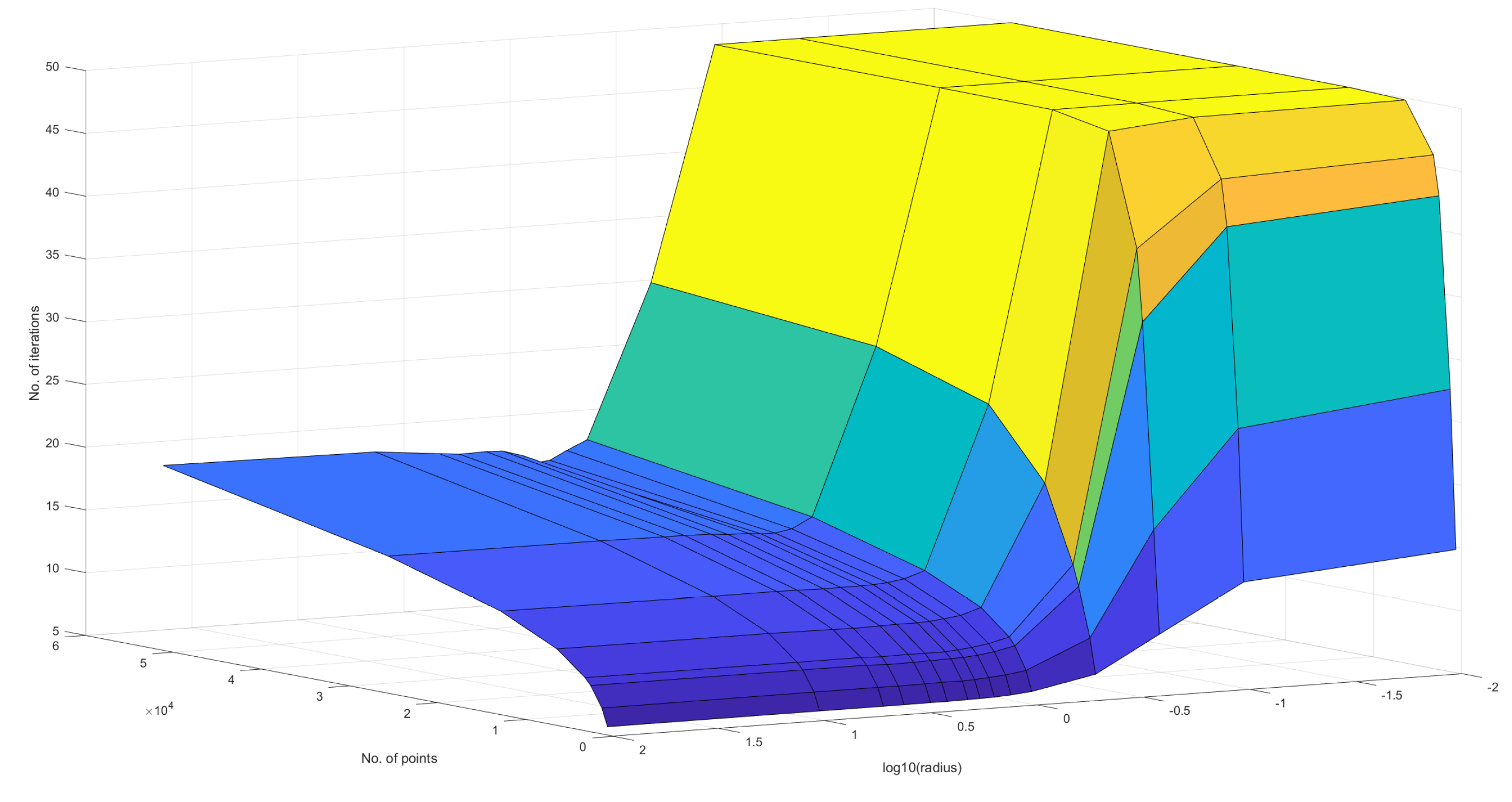

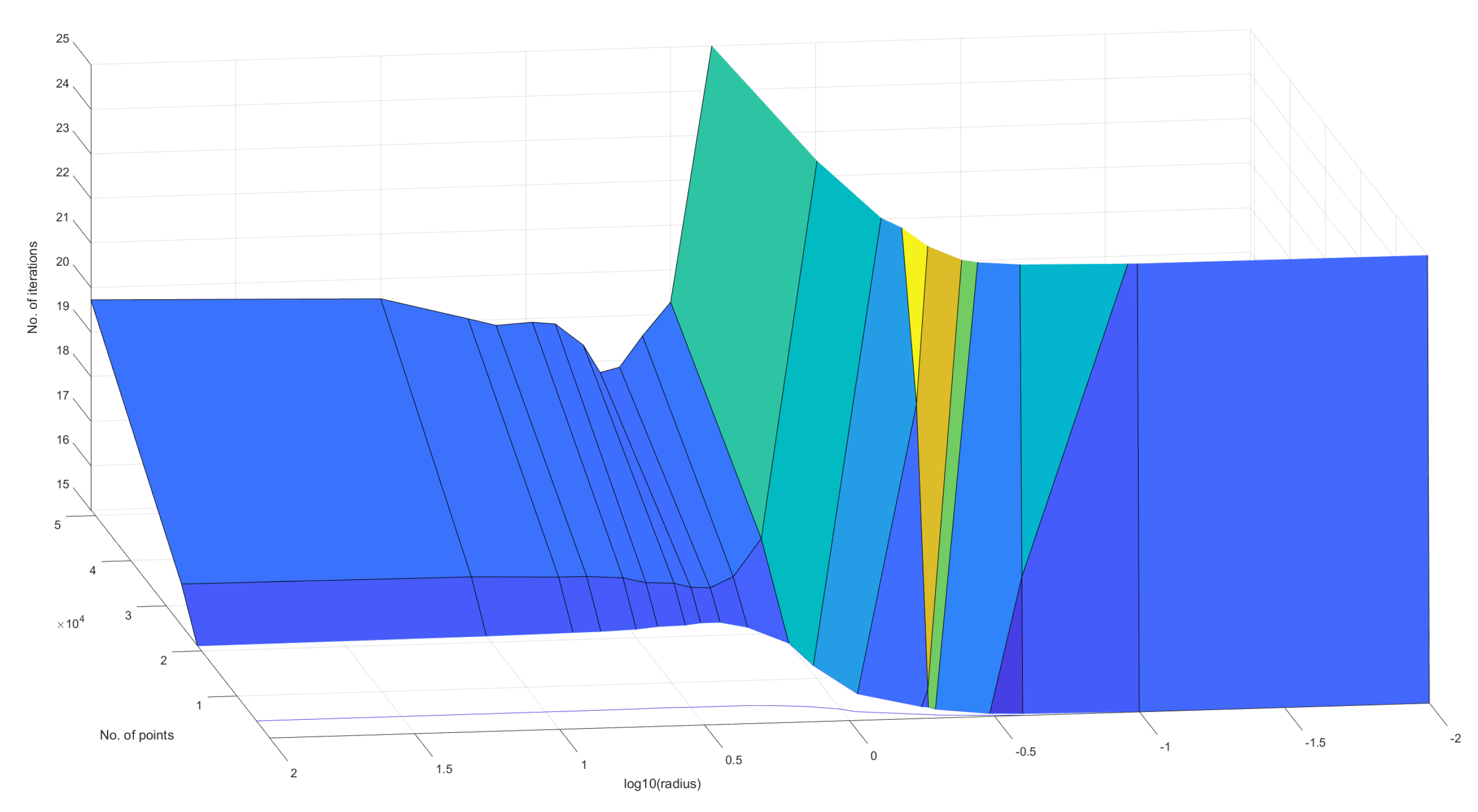

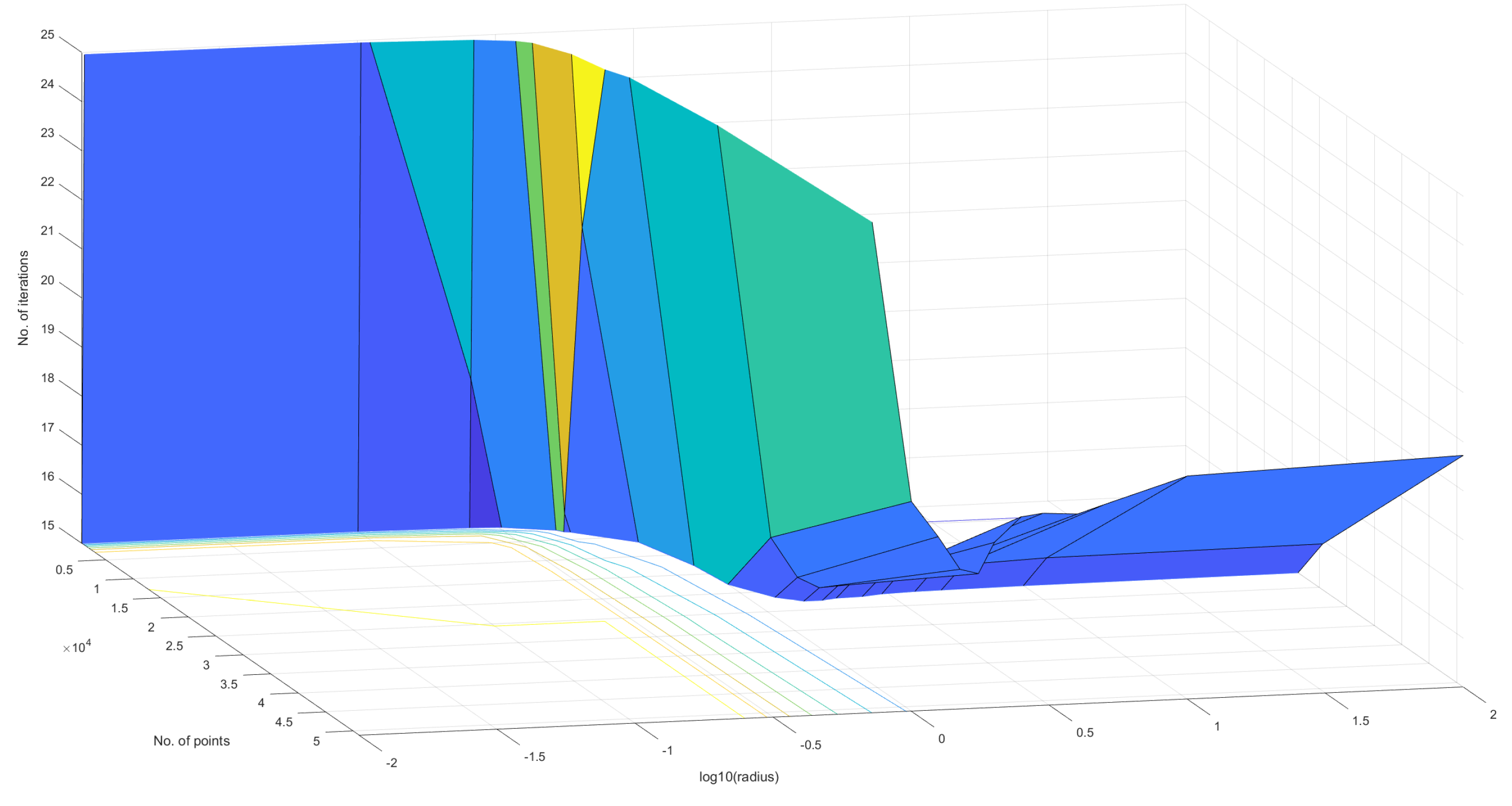

- Number of iterations: One iteration of the clustering algorithm occurs when the algorithm performs the cluster update followed by the centroid update (the algorithm must then perform the cluster update once again). The number of times the algorithm repeats these 2 steps before stopping is the number of iterations.

- Execution time: The amount of time taken for a clustering algorithm to give the final output (the final centroids and clusters) given the 2-dimensional data points as input, i.e. the time taken end to end for the clustering process. All times in this work are recorded in milliseconds (ms).

4.1. Candidate Algorithms

- Quantum Analogue: The most important candidate for our testing. The algorithm is described in Section 3.3.

- 2-D Classical: The standard classical k nearest-neighbour algorithm implemented upon the original 2-dimensional dataset. The algorithm performed Cluster Update [Definition 1] with (i.e. using the Euclidean dissimilarity) and , the phase-space plane in which the dataset exists. It performed Centroid Update [Definition 2] with the same parameters, resulting in the updated centroid being equal to the average point of the cluster. In terms of closed form expression, where. This serves as a baseline for performance comparison.

- Stereographic Classical: The standard classical k nearest-neighbour algorithm, but implemented upon the stereographically projected 2-dimensional dataset. The algorithm performed Cluster Update [Definition 1] with (i.e. using the Euclidean dissimilarity) as well, but with , the 3-dimensional space which the projected dataset occupies. It performed Centroid Update [Definition 2] with the same parameters, resulting in the updated centroid once again being equal to the average point of the cluster. In terms of closed form expression, once again, . Note that generally, this centroid will lie within the stereographic sphere. This algorithm serves as another control to see how much is the effect of just stereographically projecting the dataset, versus restricting the centroid to the surface of the sphere. It is an intermediate step between the Quantum Analogue and the 2-D classical algorithms.

4.2. Experiments

- 2-D Classical: Number of points, dataset noise

- Quantum Analogue: Radius, Number of points, dataset noise

- Stereographic Classical: Radius, Number of points, dataset noise

4.2.1. Characterisation Experiment 1

- It exhaustively covers all the parameters that can be used to quantify the performance of the algorithms. We were able to observe very important trends in the performance parameters with respect to the choice of radius and the effect of the number of points (affecting the choice of when one should trigger the clustering process on the collected received points).

- It avoids the commonly known problem of overfitting. Though this approach is not usually used in the testing of the k nearest-neighbour algorithm due to its iterative nature, we felt that from a machine learning perspective, it is useful to know how well the algorithms perform in a classification setting as well.

- Another reason that justifies the approach of training and testing (clustering and classification) is the nature of the real-world application setup. When transmitting QAM data through optic fibre, the receiver receives only one point at a time and has to classify the received point to a given cluster in real-time using the current centroid values. Once a number of datapoints have accumulated, the k means algorithm can be run to update the centroid values; after the update, the receiver will once again perform classification until some number of points has been accumulated. Hence, we can see that in this scenario the clustering, as well as classification performance of the chosen method, becomes important.

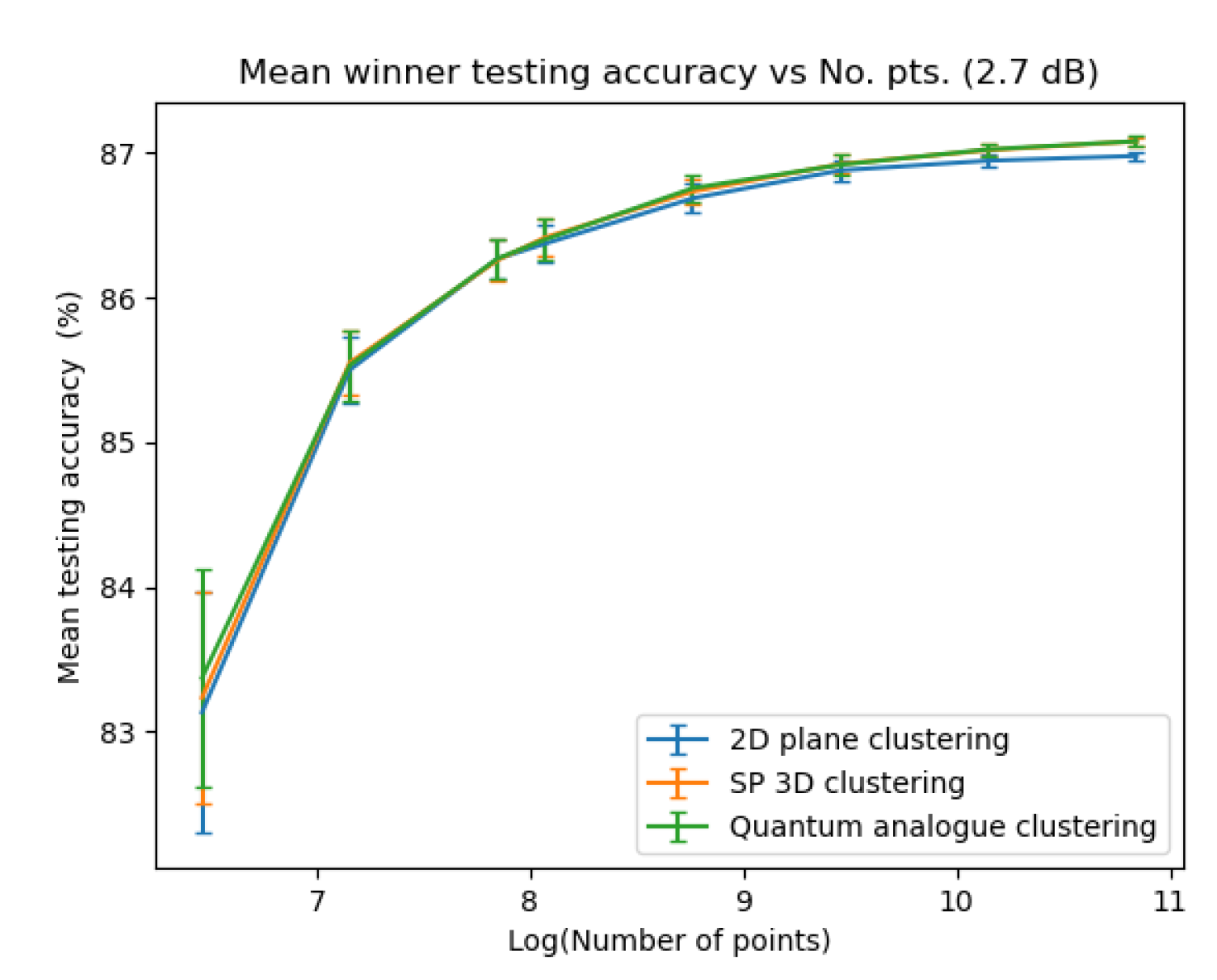

4.2.2. Characterisation Experiment 2

4.3. Results of Experiments

4.3.1. Characterisation Experiment 1: The Overfitting experiment

4.3.2. Characterisation Experiment 2: the Stopping Criteria experiment

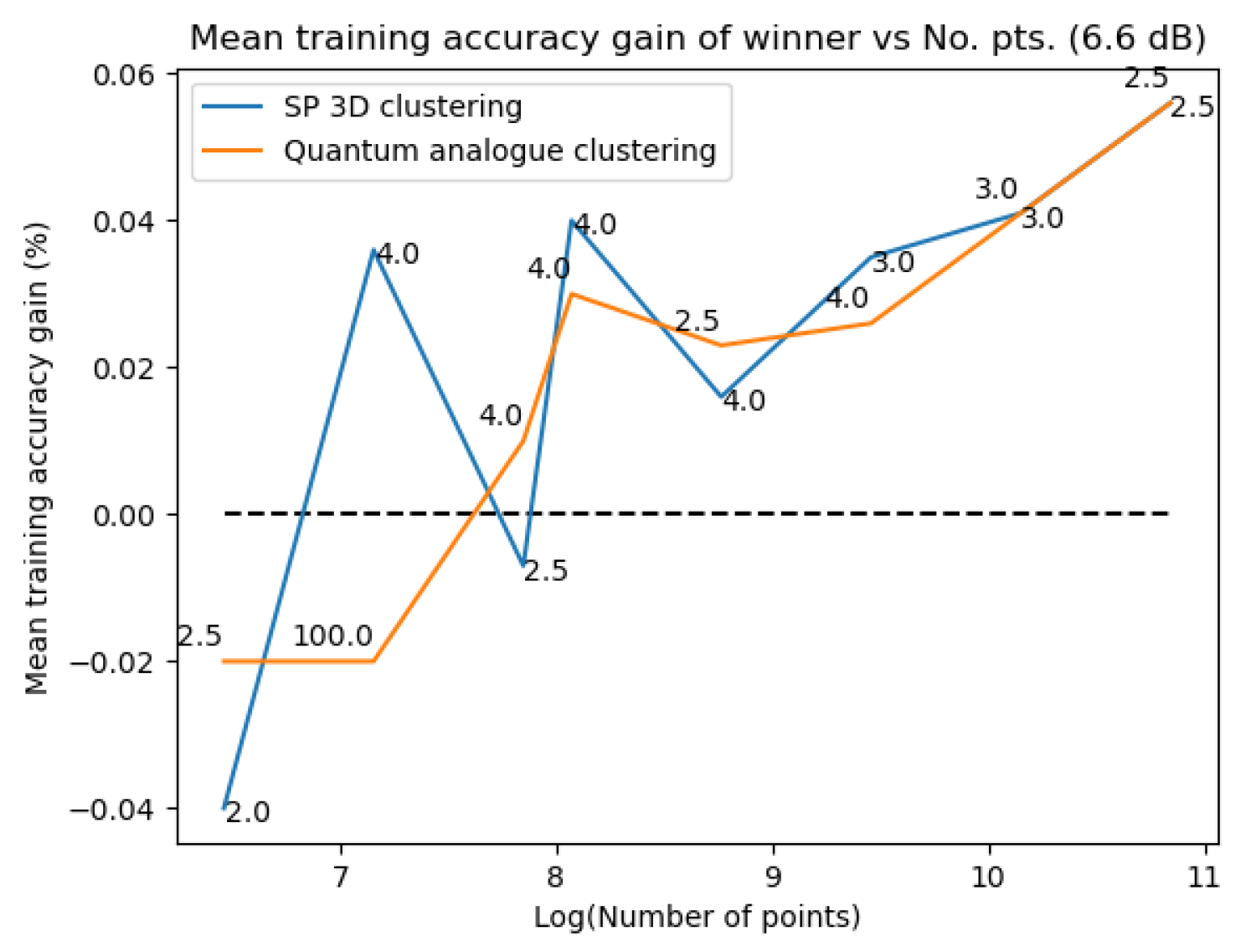

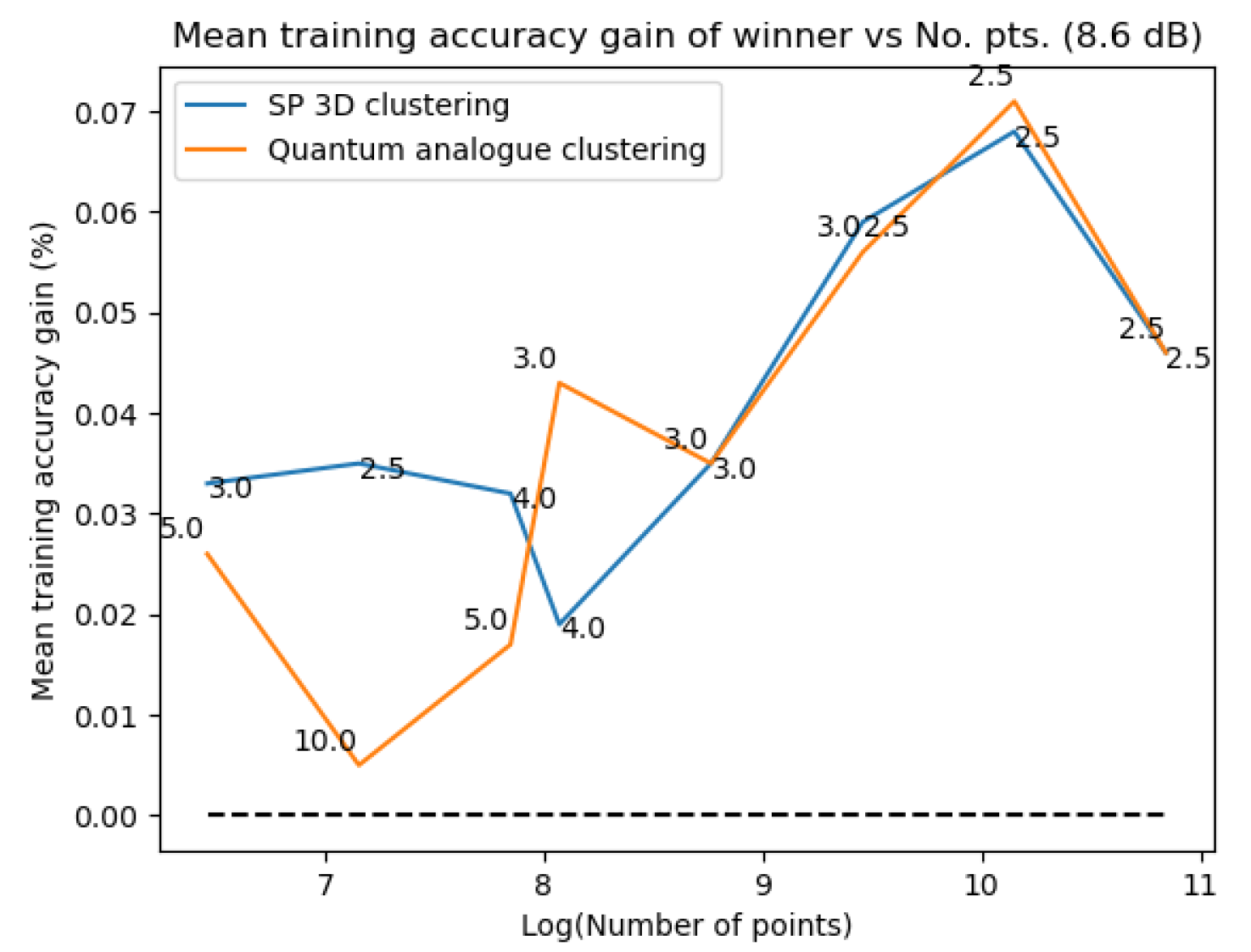

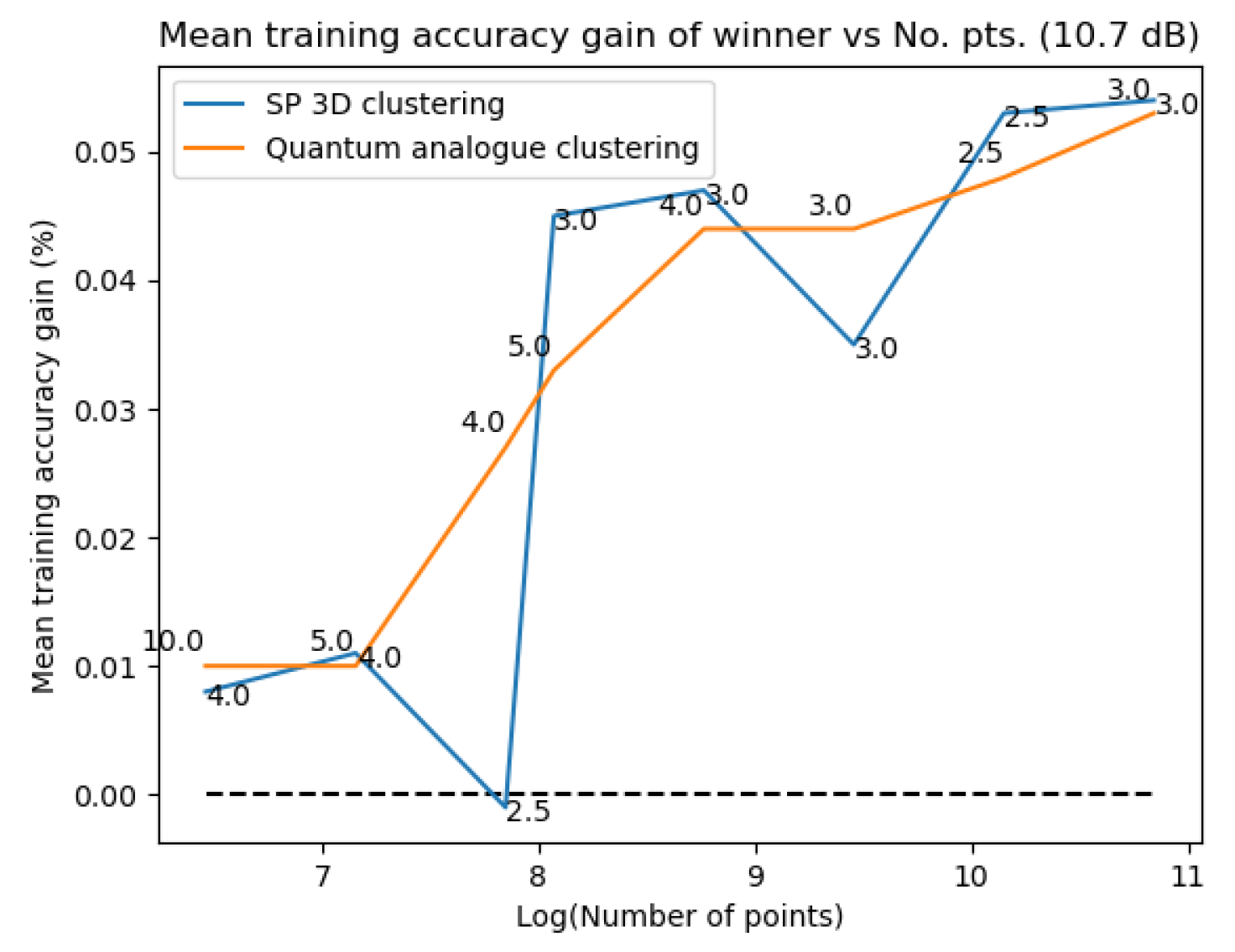

4.4. Discussion and Analysis of Experimental Results

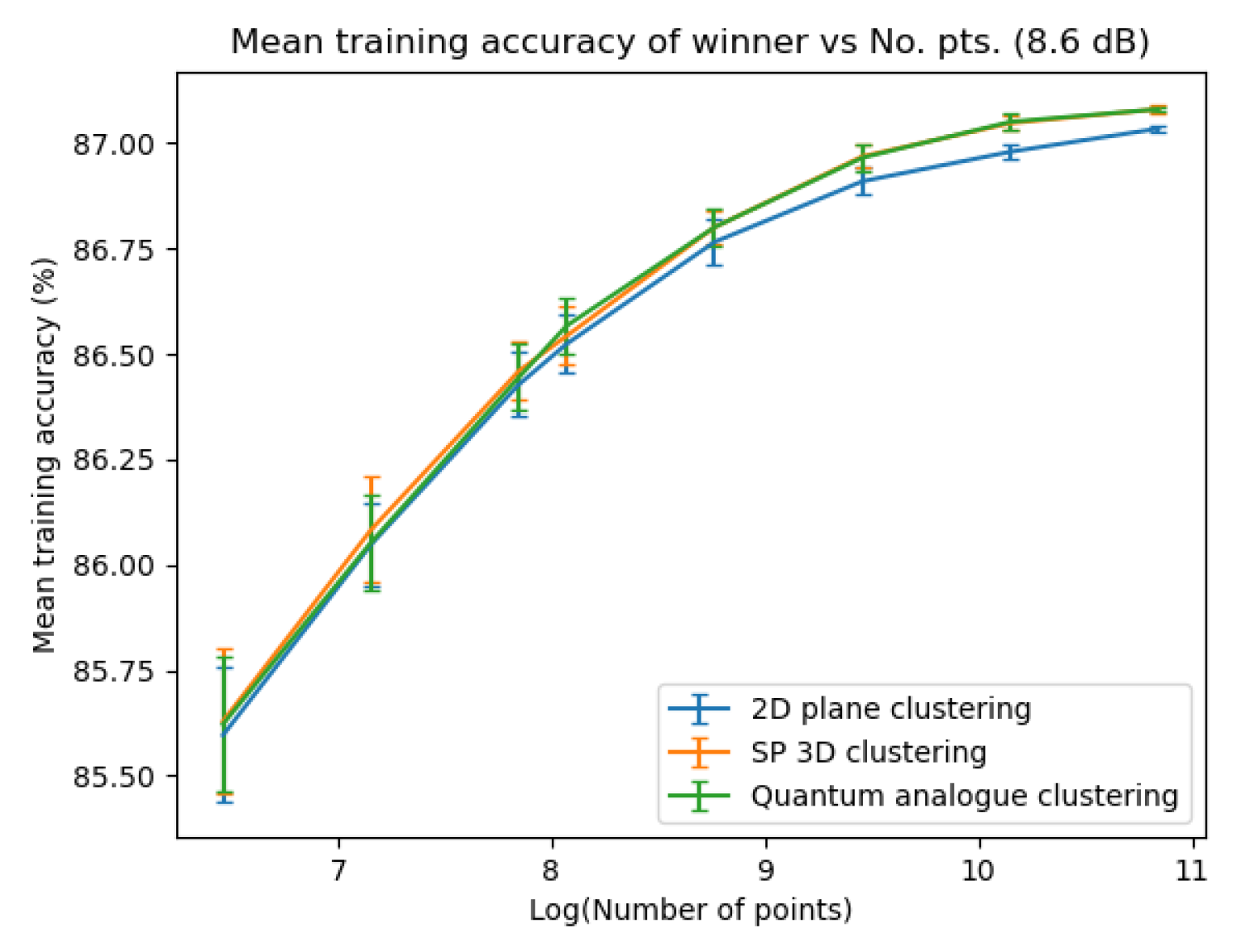

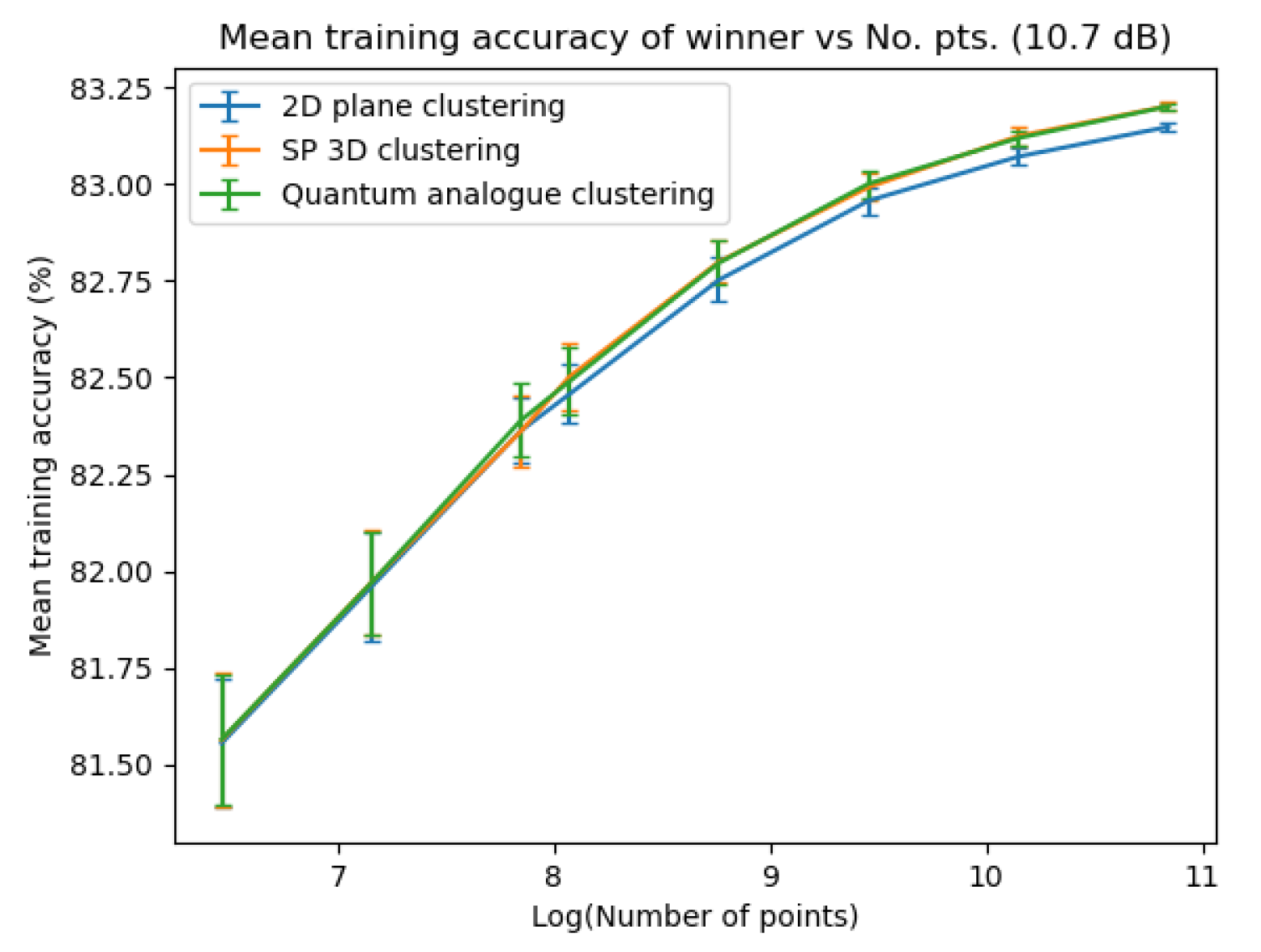

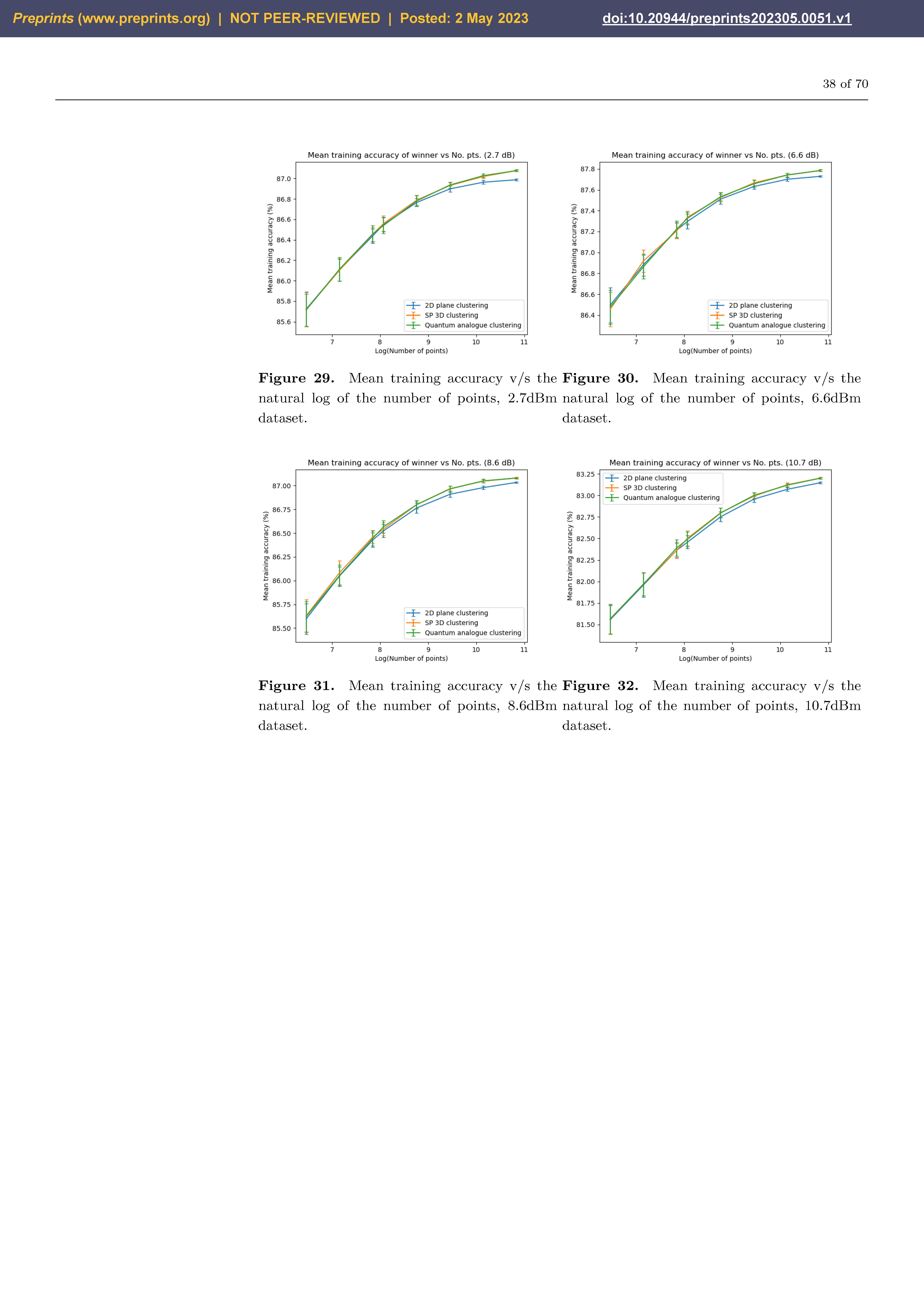

4.4.1. Characterisation Experiment 1: the overfitting test

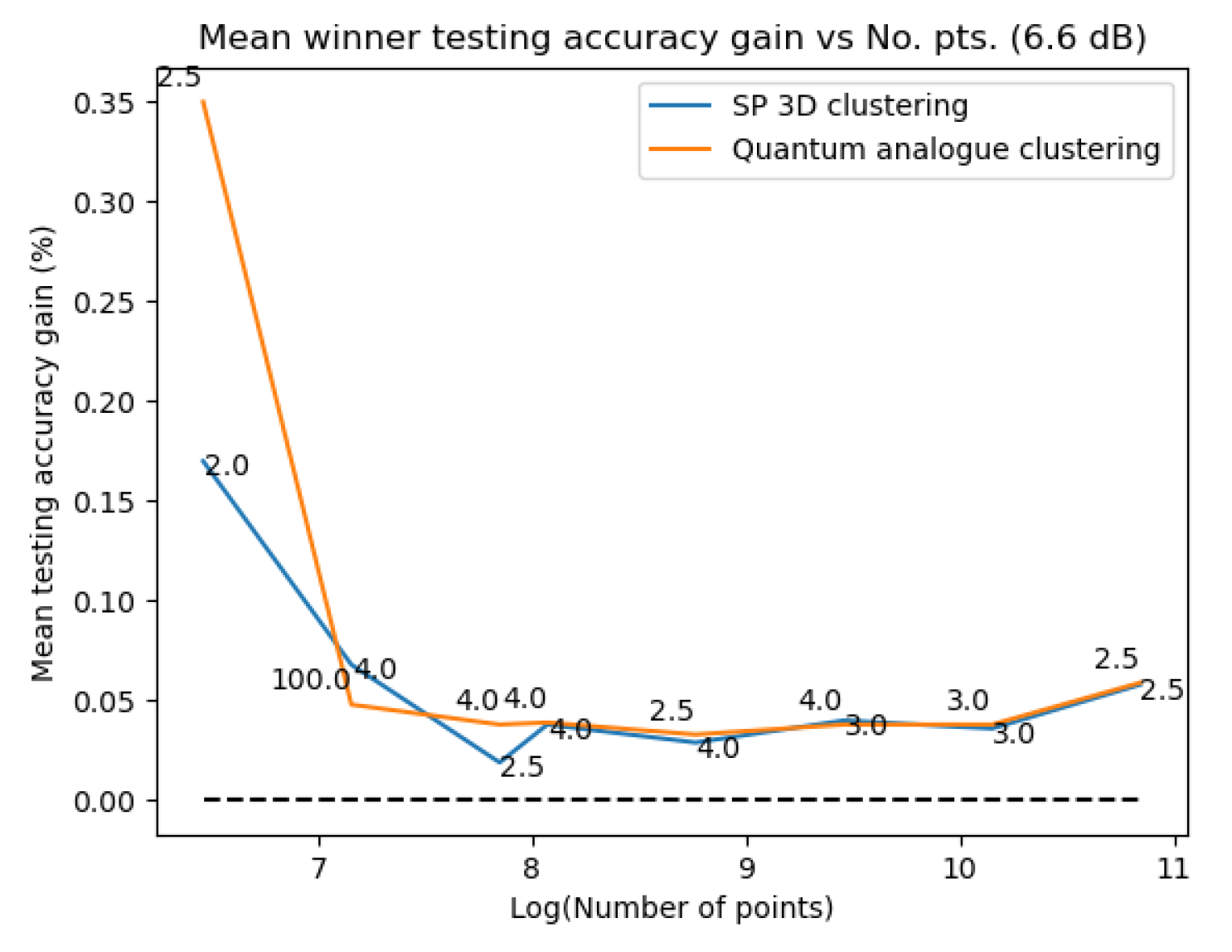

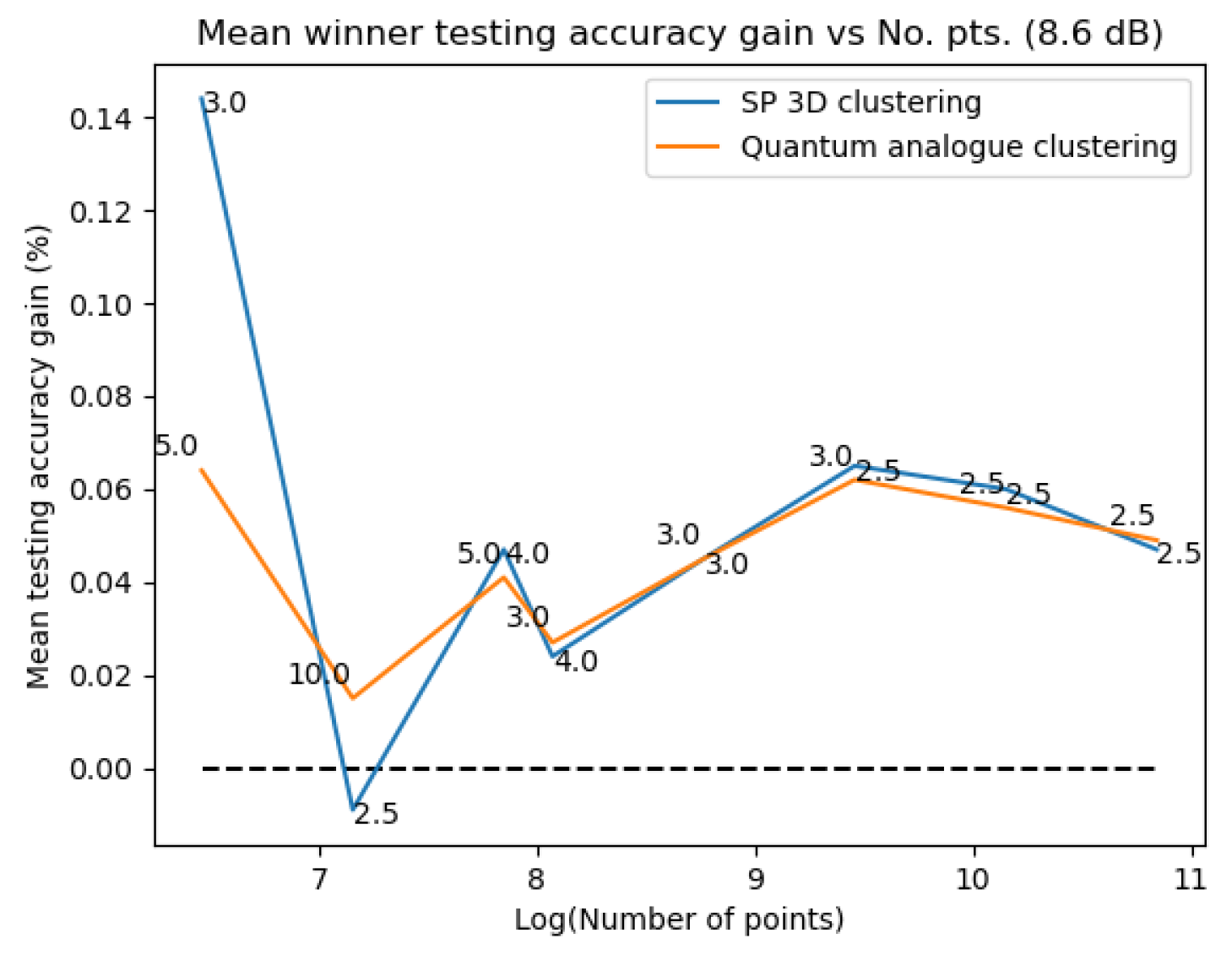

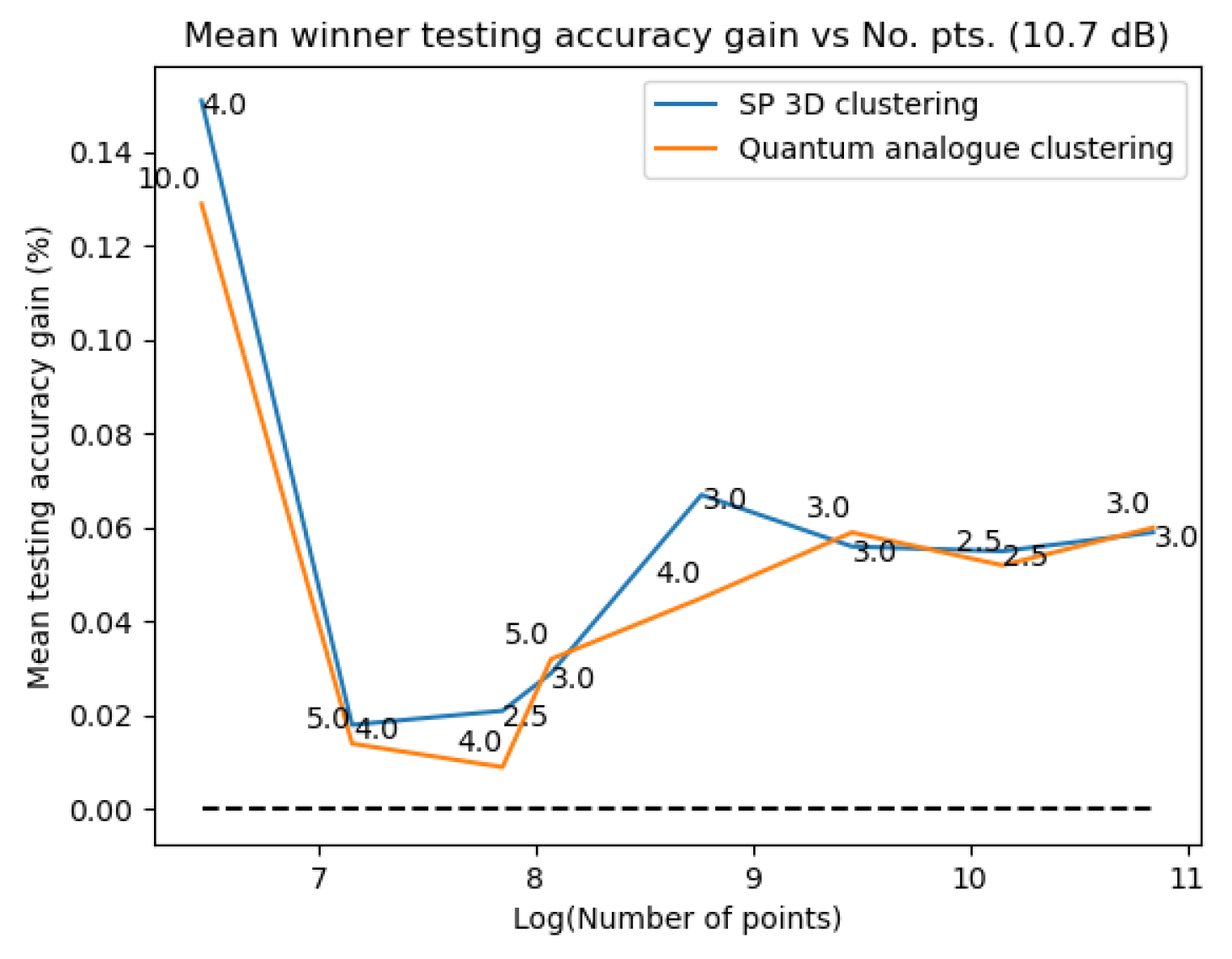

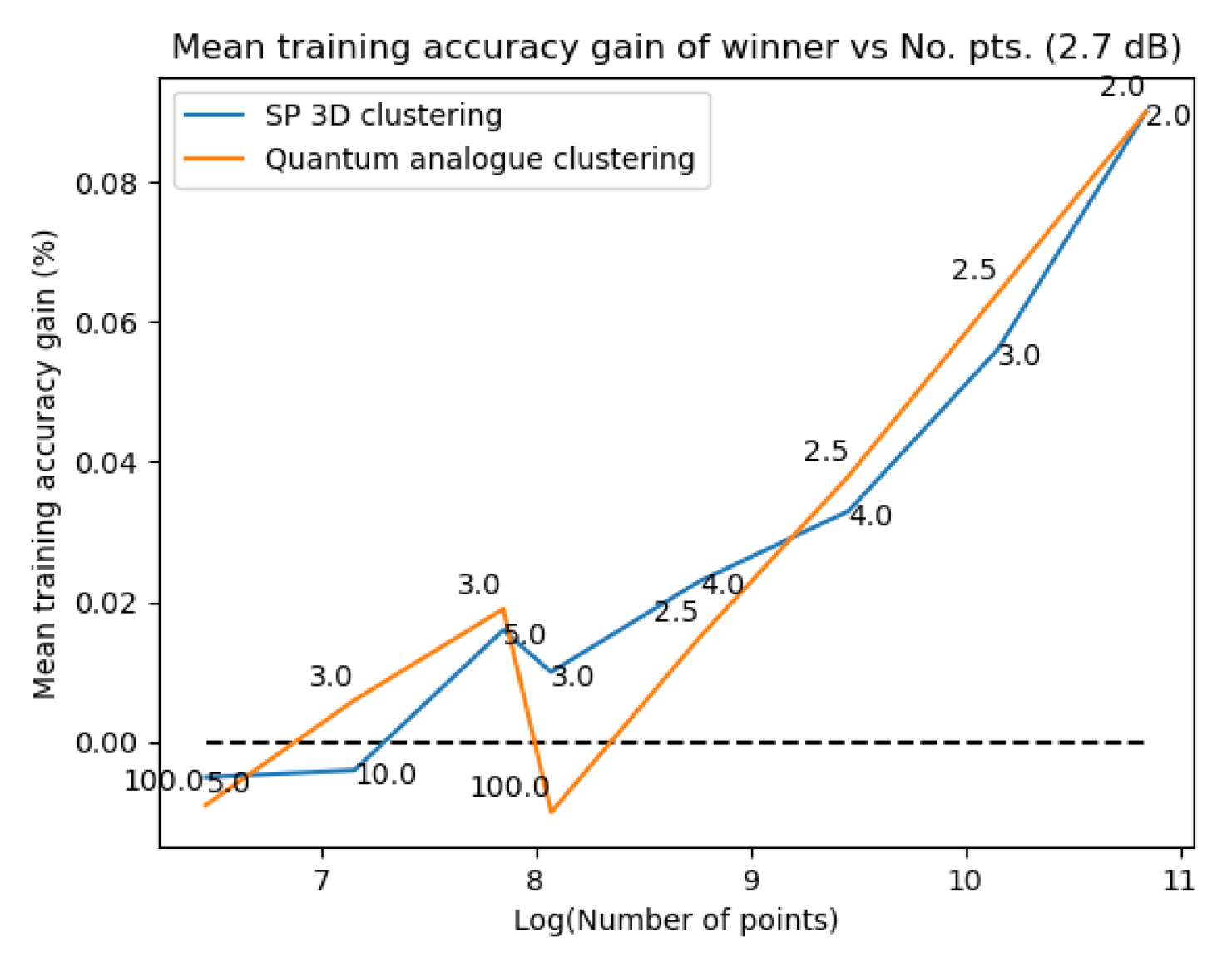

- The ideal radius of projection is greater than 1 and between 2 and 5. At this ideal radius, one achieves maximum testing and training accuracy, and minimum iterations.

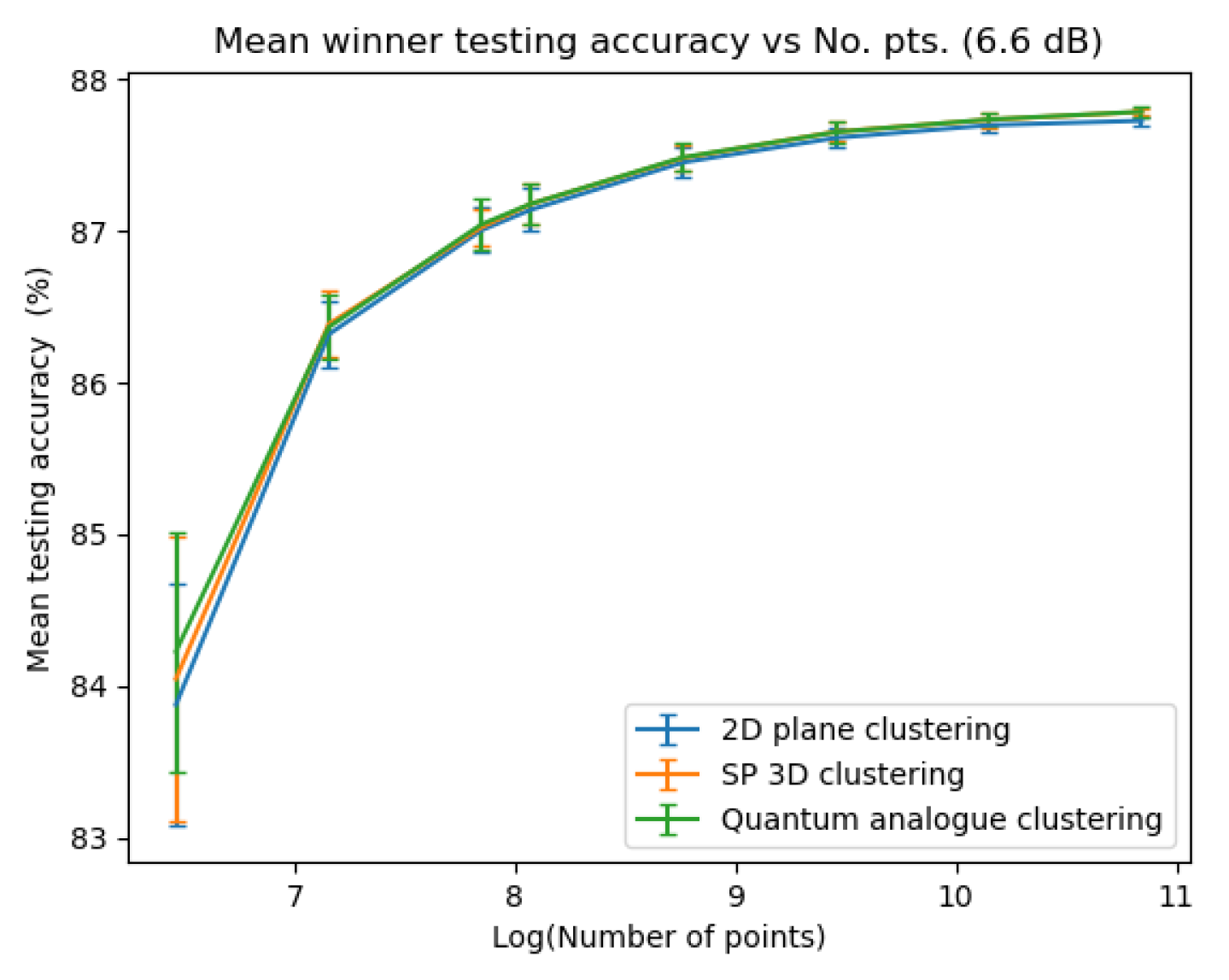

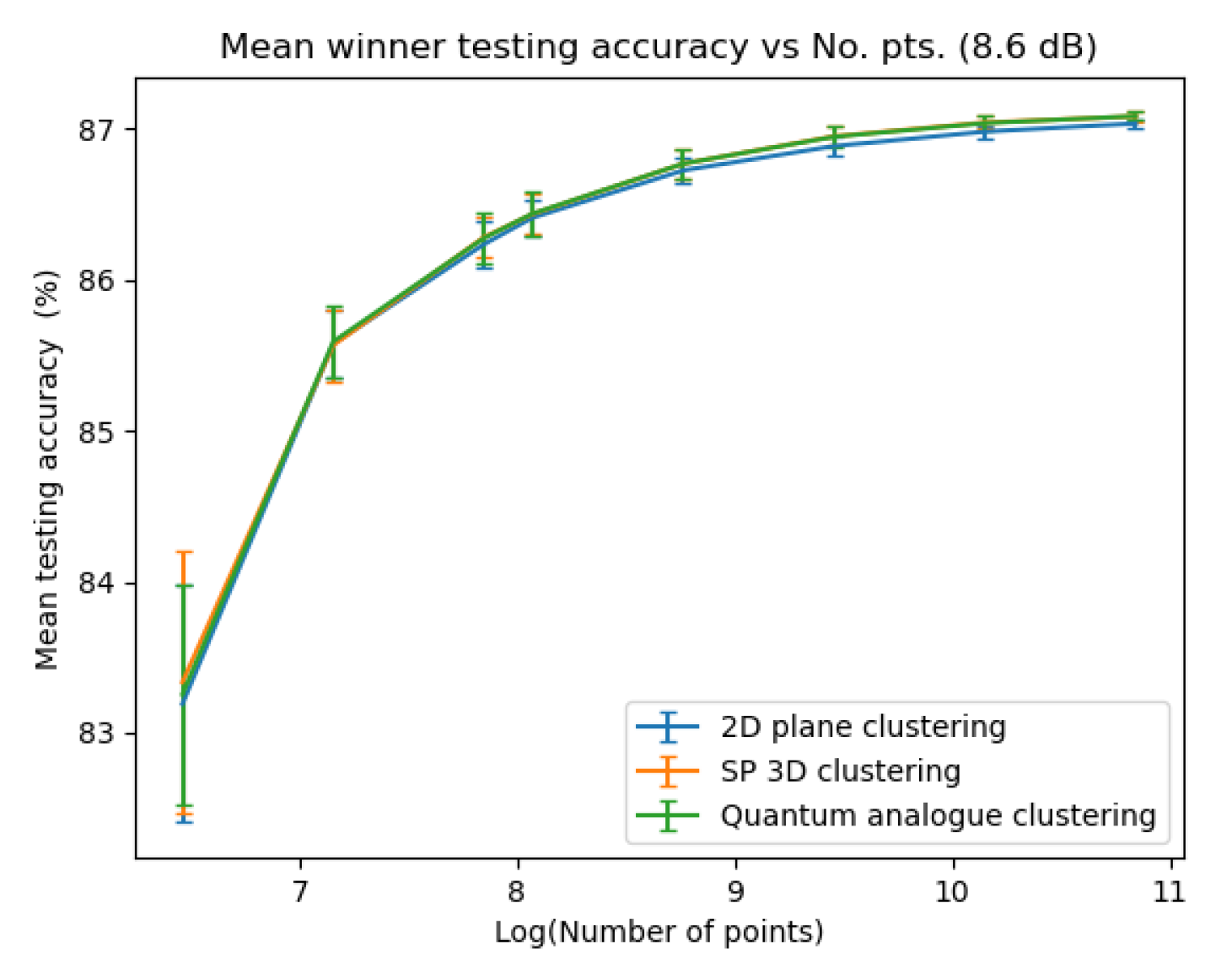

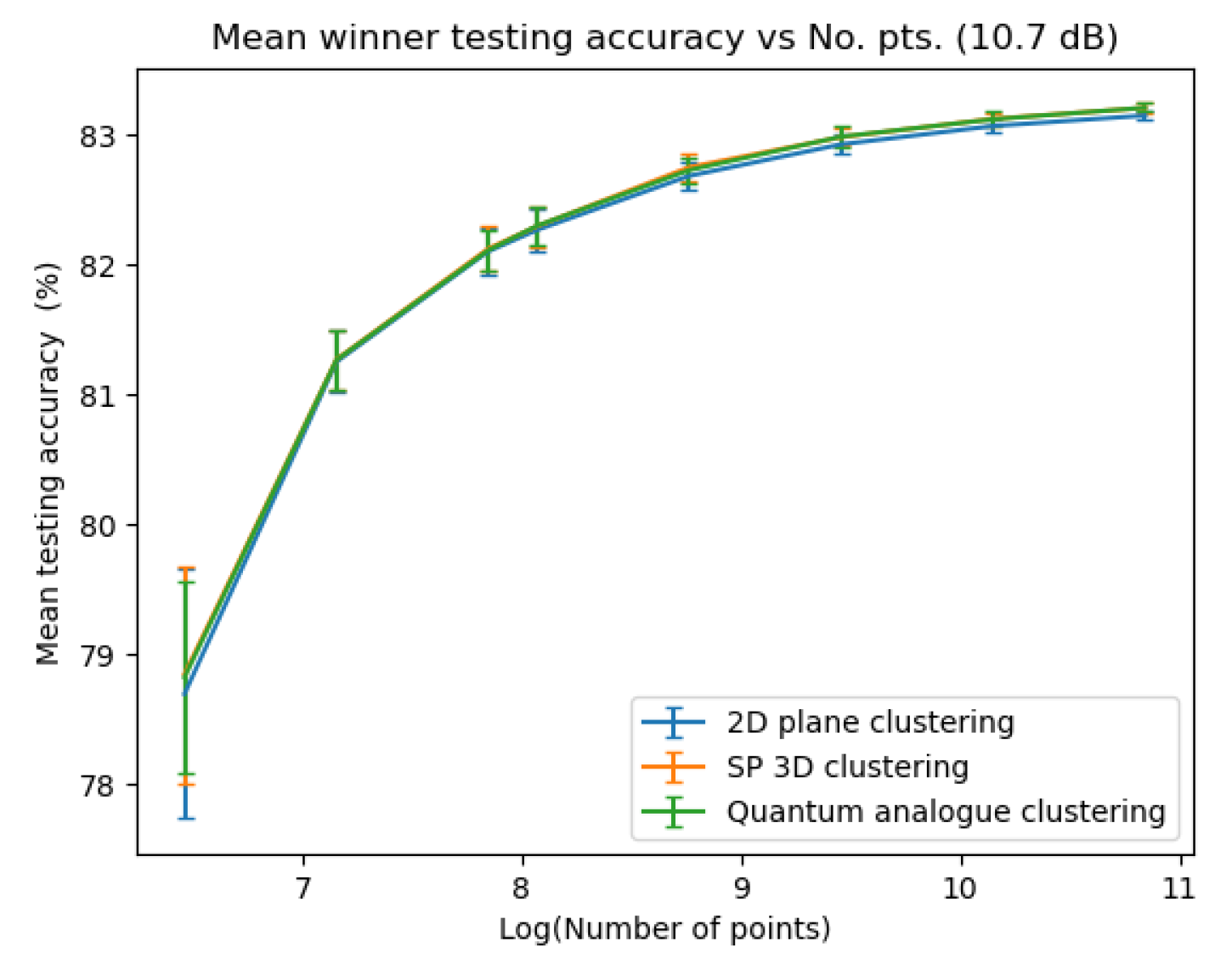

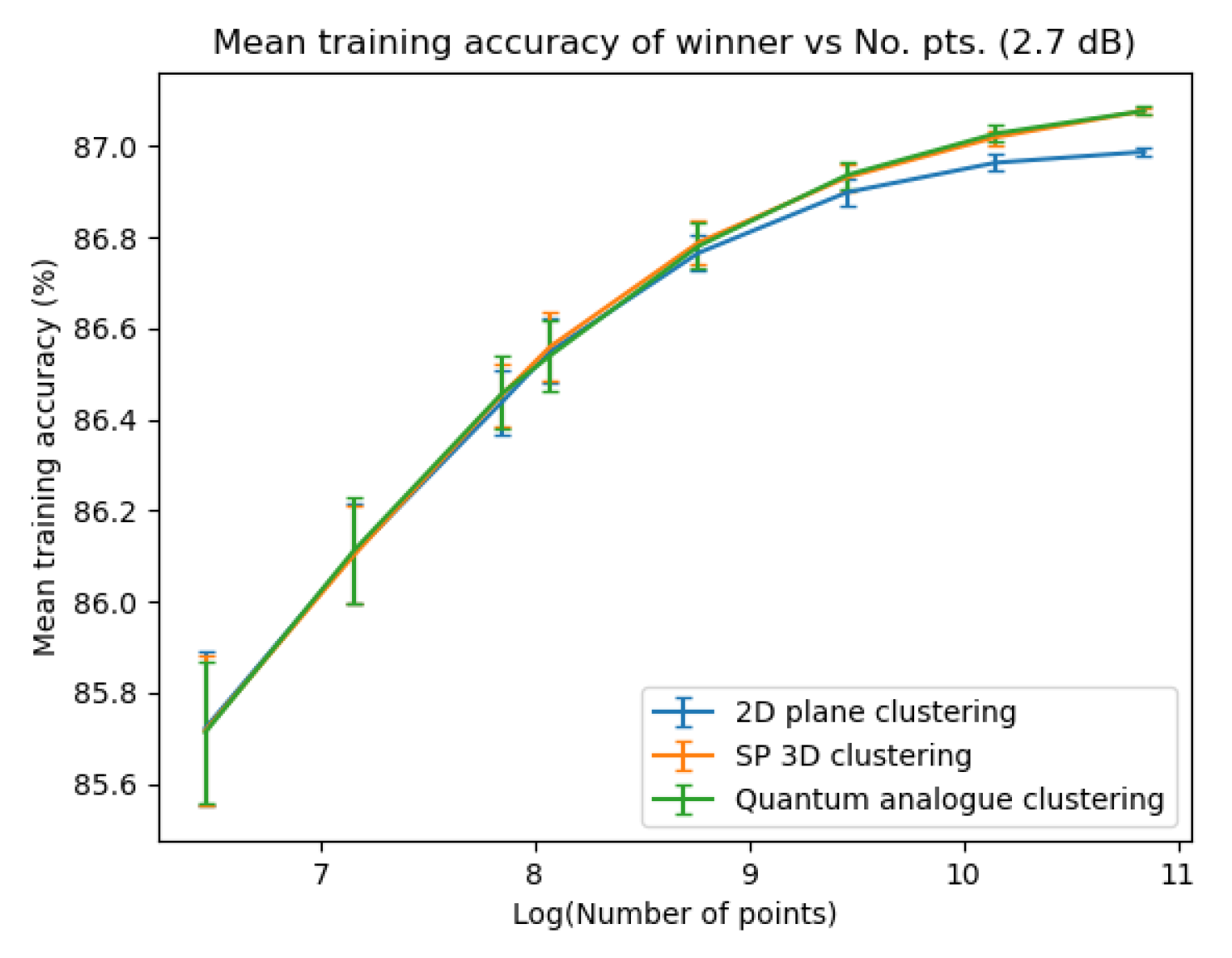

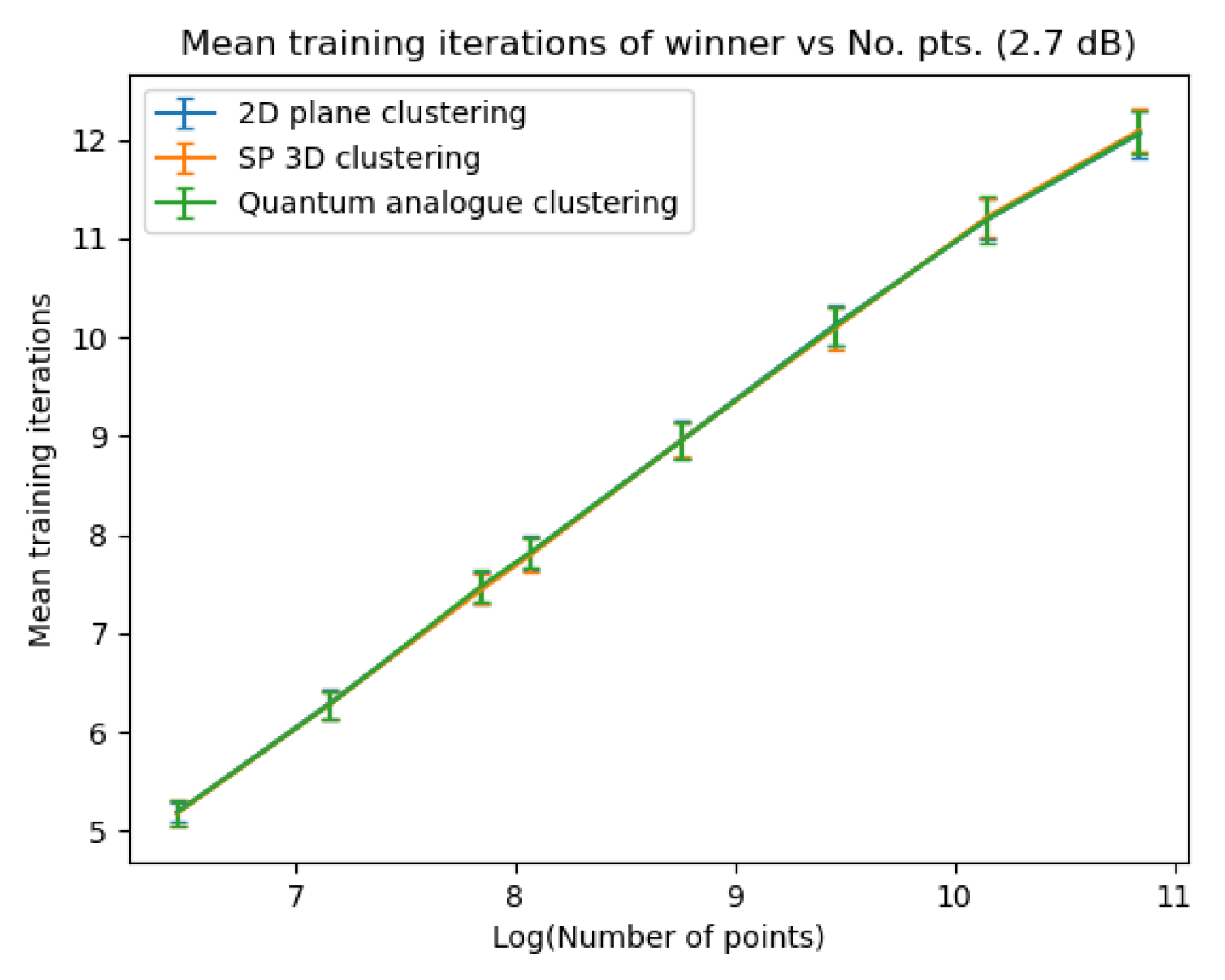

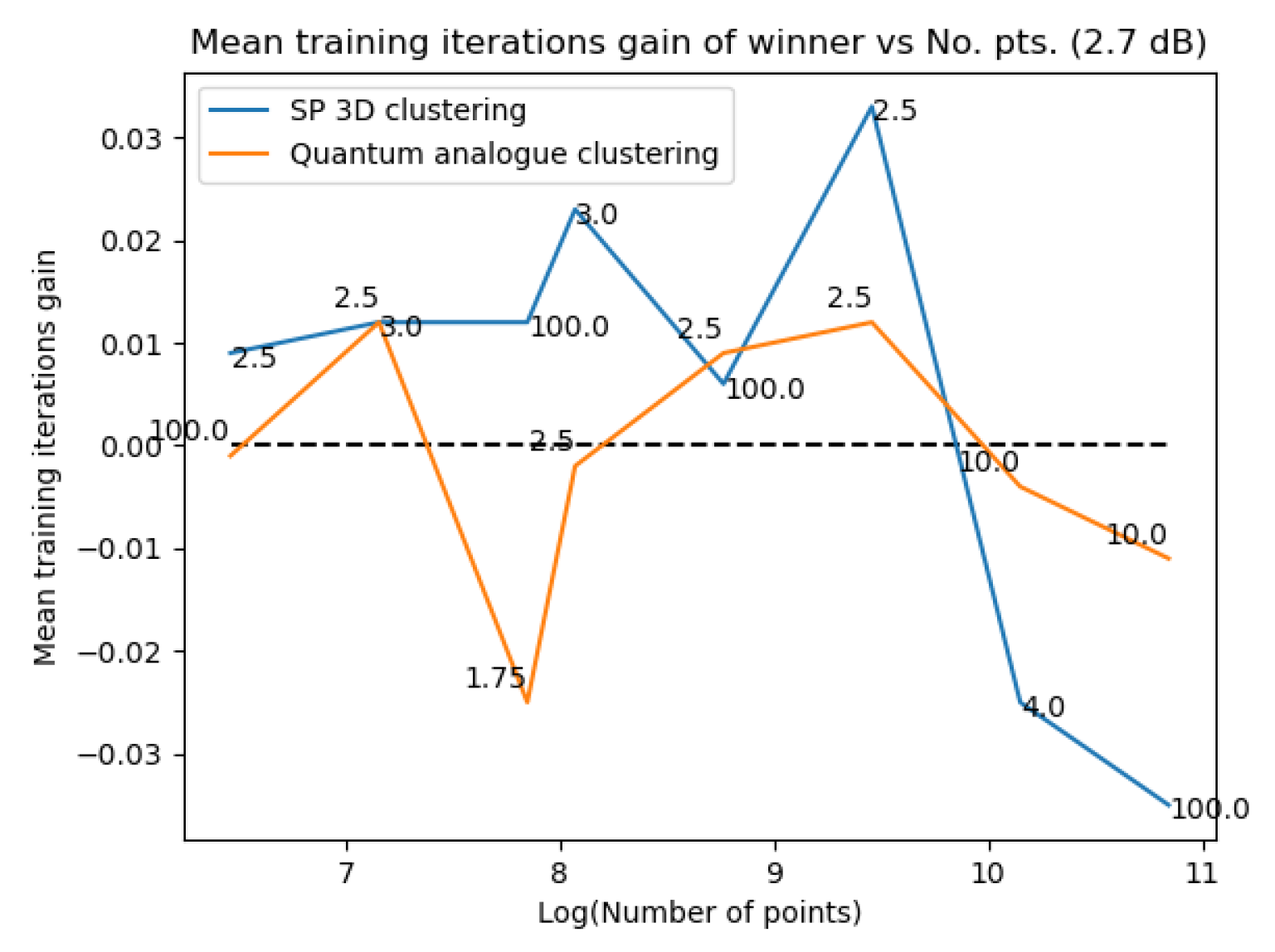

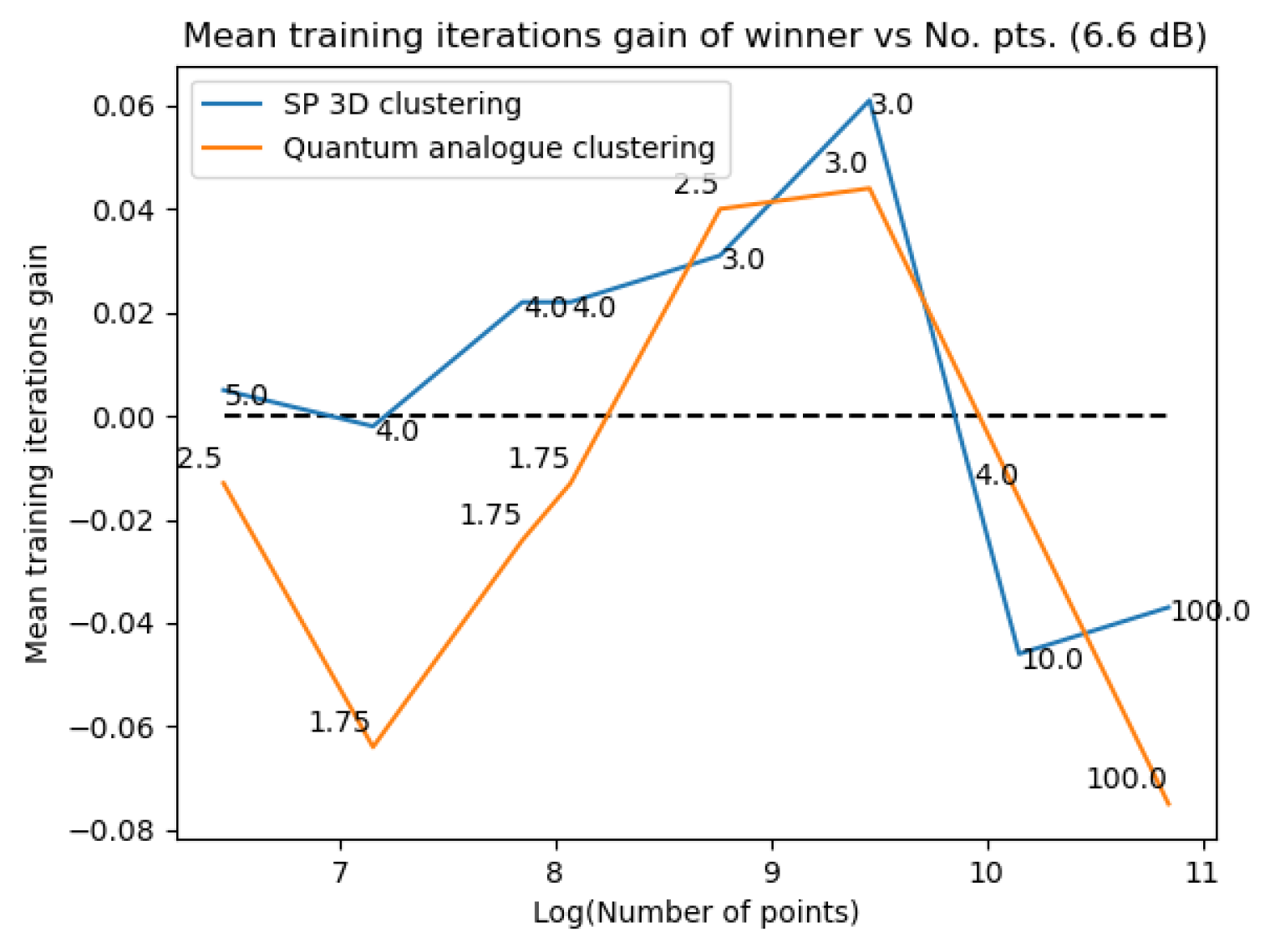

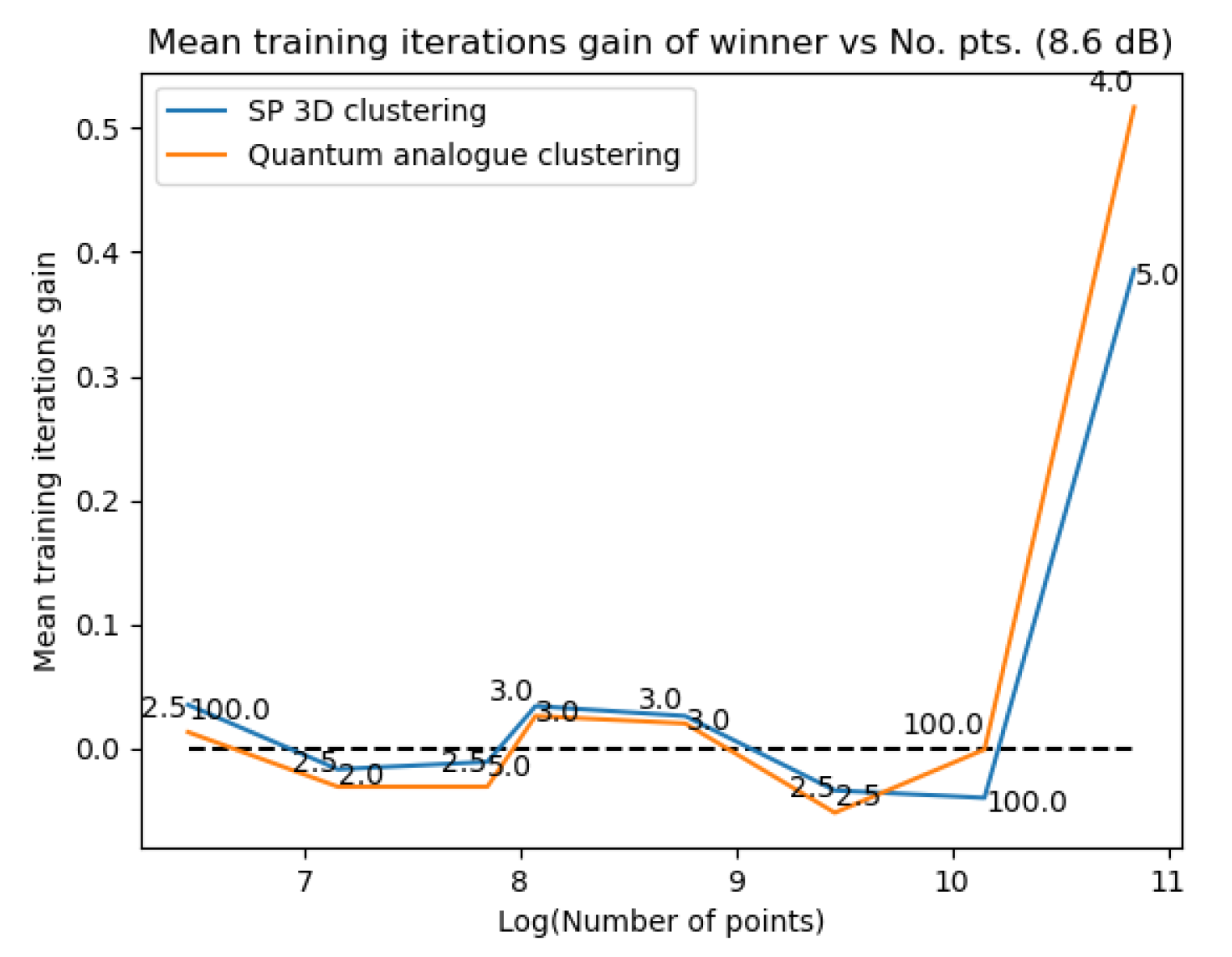

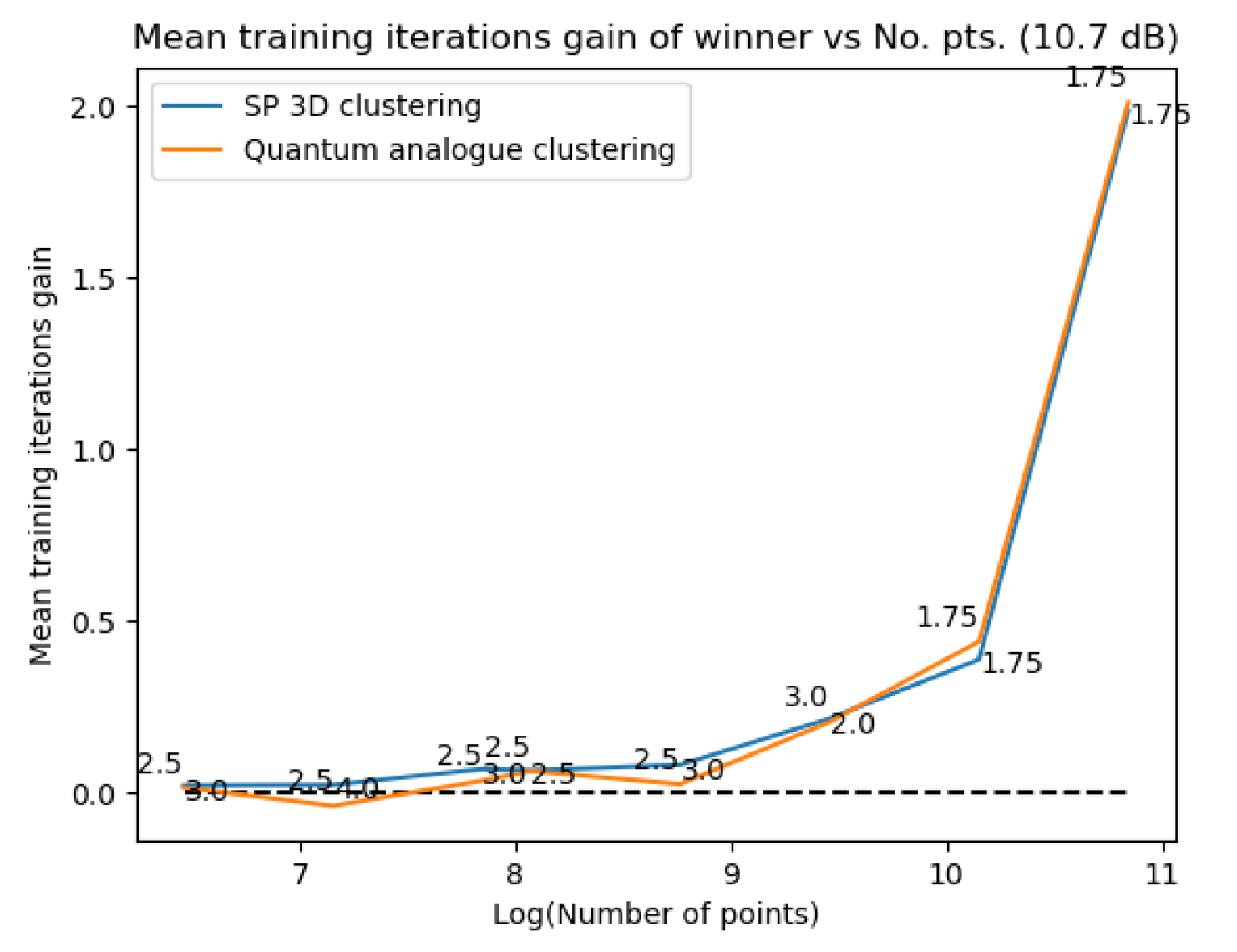

- In general, the accuracy performance is the same for 3D Stereographic and Quantum Analogue algorithms - this shows a significant contribution of the stereographic projection to the advantage as opposed to ’quantumness’. This is a very significant distinction, not made by any other previous work. The Quantum Analogue algorithm generally requires fewer iterations to achieve the ideal accuracy, however.

- Quantum Analogue algorithm and 3D Stereographic Classical algorithm lead to an increase in the accuracy performance in general, with the increase most pronounced for the 2.7dBm dataset.

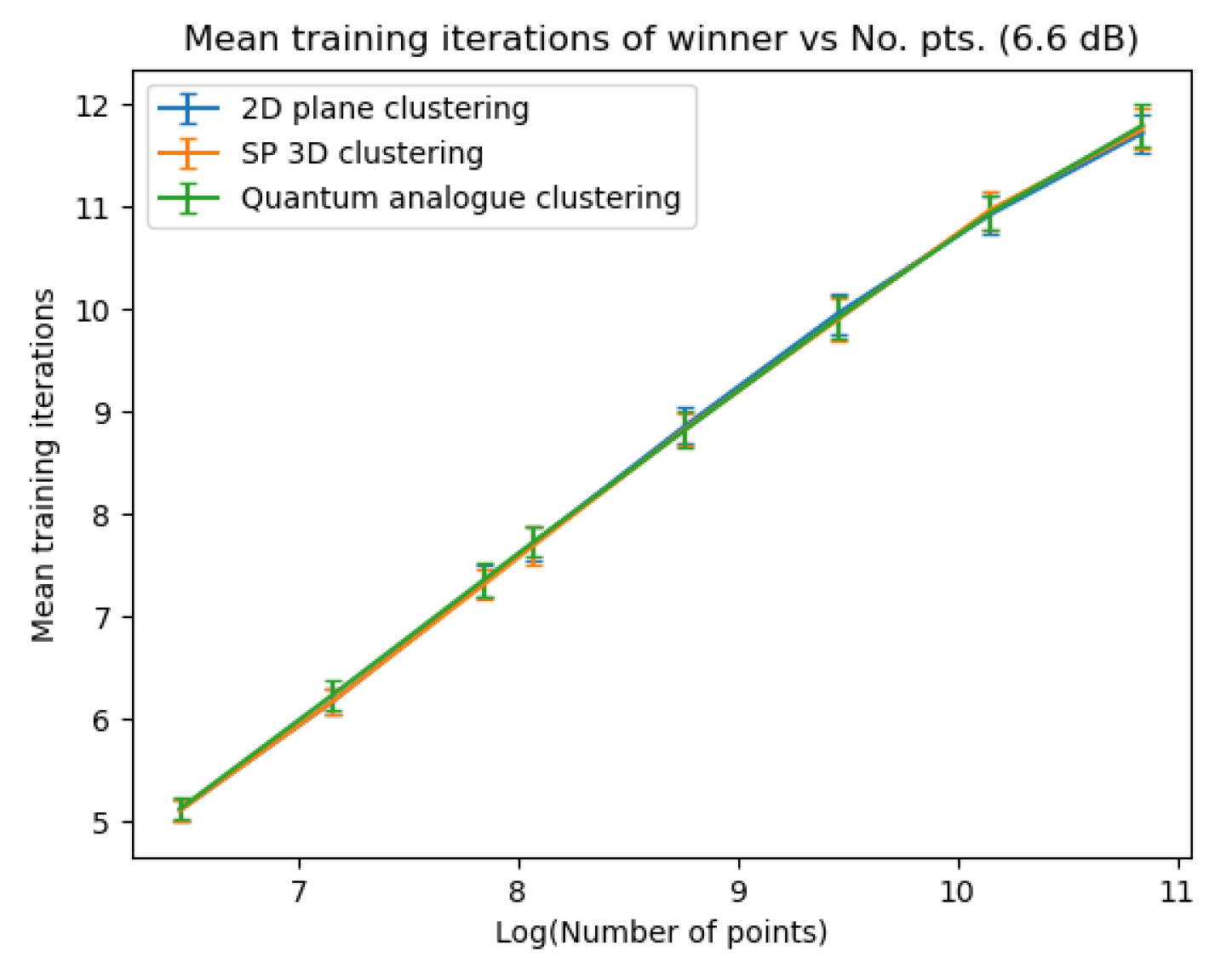

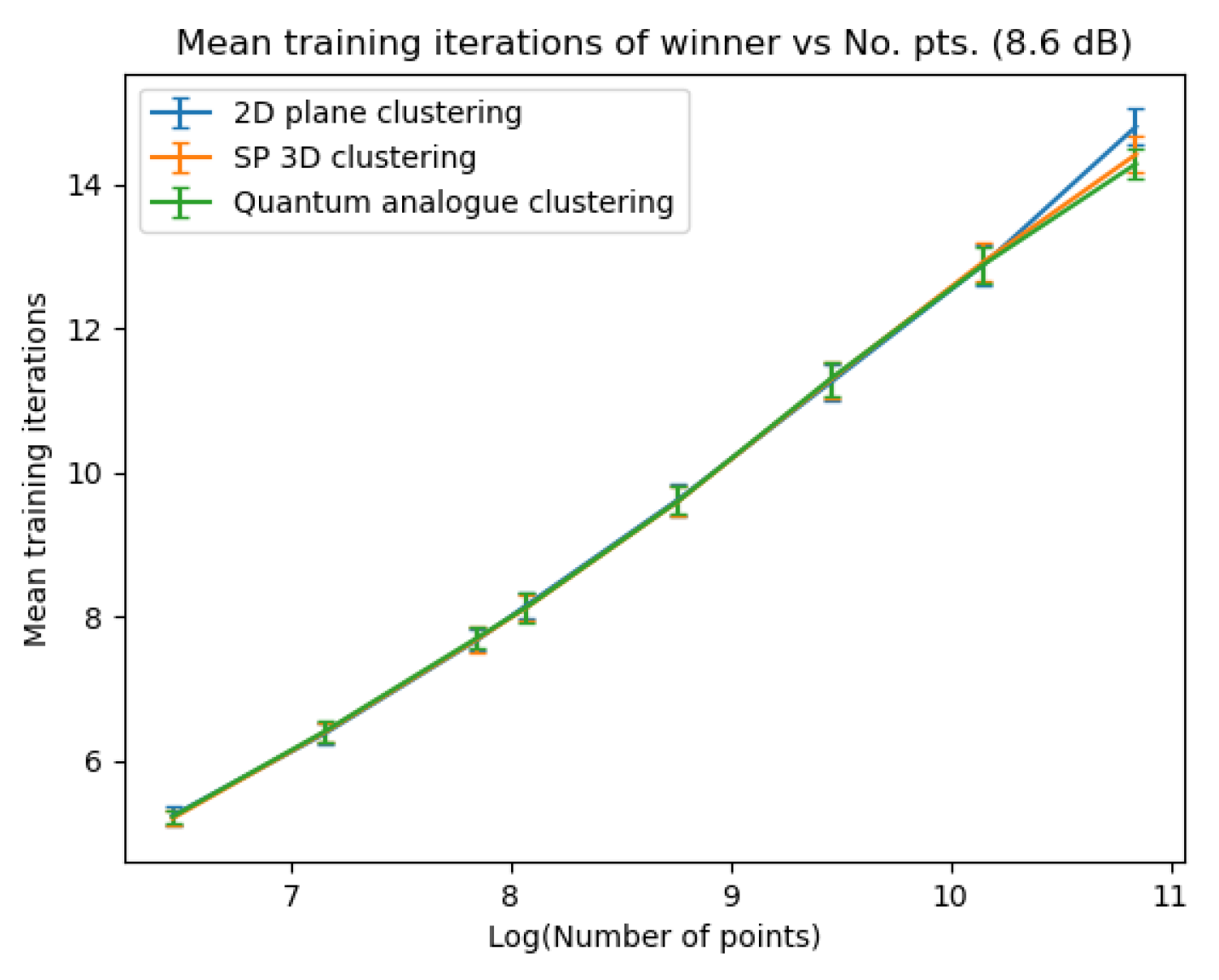

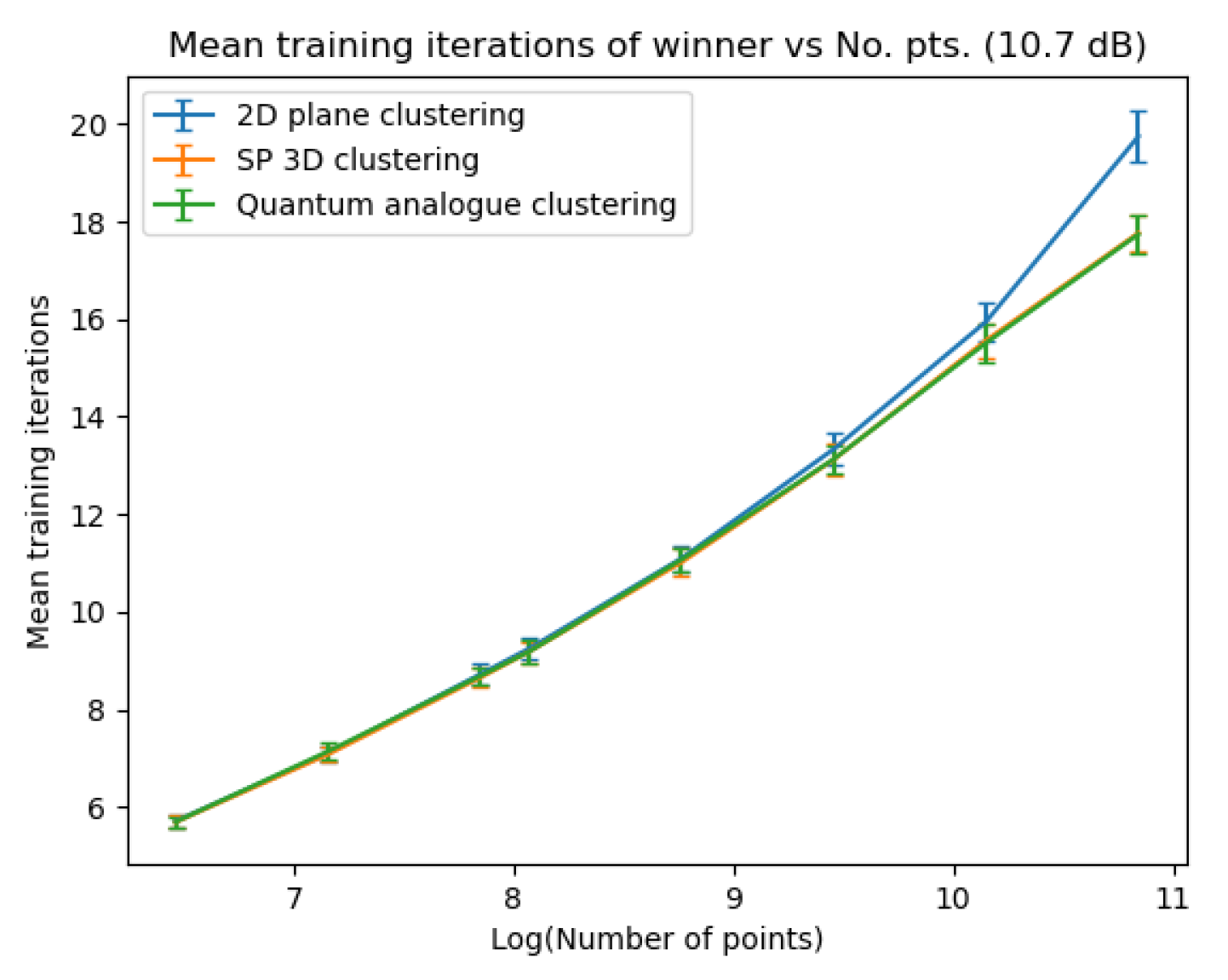

- The Quantum Analogue algorithm and 3D Stereographic Classical algorithm give more iteration performance gain (fewer iterations required than 2D classical) high noise datasets and for a large number of points.

- Generally, increasing the number of points works in favour of the Quantum Analogue algorithm and 3D Stereographic Classical algorithm, with the caveat that a good radius must be carefully chosen.

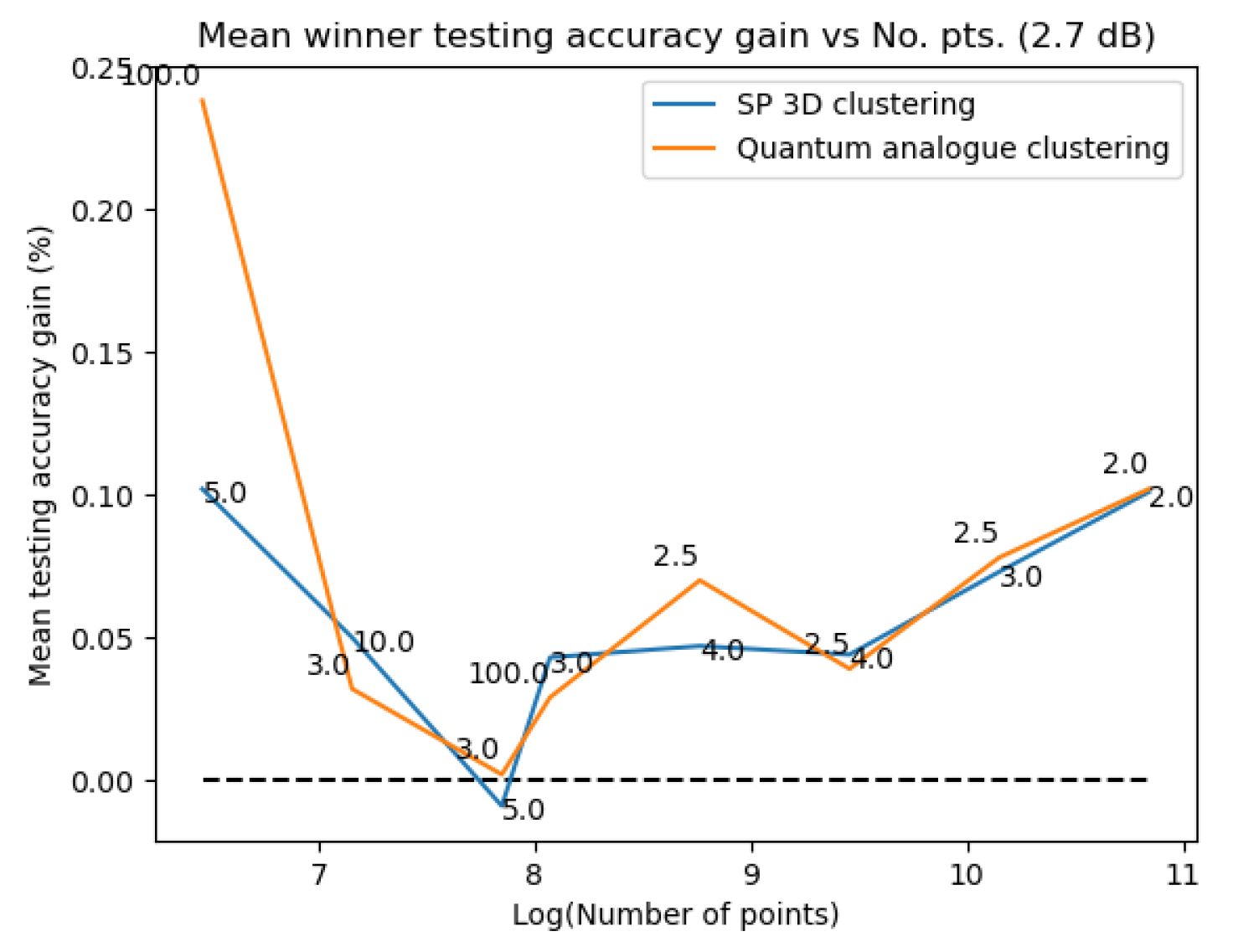

4.4.2. Characterisation Experiment 2: Stopping Criterion

- These results further stress the importance of choosing a good radius (2 to 5) and a better stopping criteria. The natural endpoint is not suitable.

- The results clearly justify the fact that the developed Quantum Analogue algorithm has significant advantages over 2D classical k-means clustering and 3D Stereographic Classical clustering.

- The Quantum Analogue algorithm performs the nearly the same as the 3D Stereographic Classical algorithm in terms of accuracy, but for iterations to achieve this max accuracy, the Quantum Analogue algorithm is better (esp. for high noise and a high number of points).

- The developed Quantum Analogue algorithm and 3D Stereographic Classical algorithm are better than the 2D classical algorithm in general - in terms of both accuracy and iterations to reach that maximum accuracy.

5. Conclusion and Further Work

5.1. Future Work

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Data Visualisation

Appendix A.1. 64-QAM Data

Appendix B. Data Embedding

| Embedding | Encoding | Num. qubits required | Gate Depth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basis | per data point | ||

| Angle | |||

| Amplitude | gates | ||

| QRAM | queries |

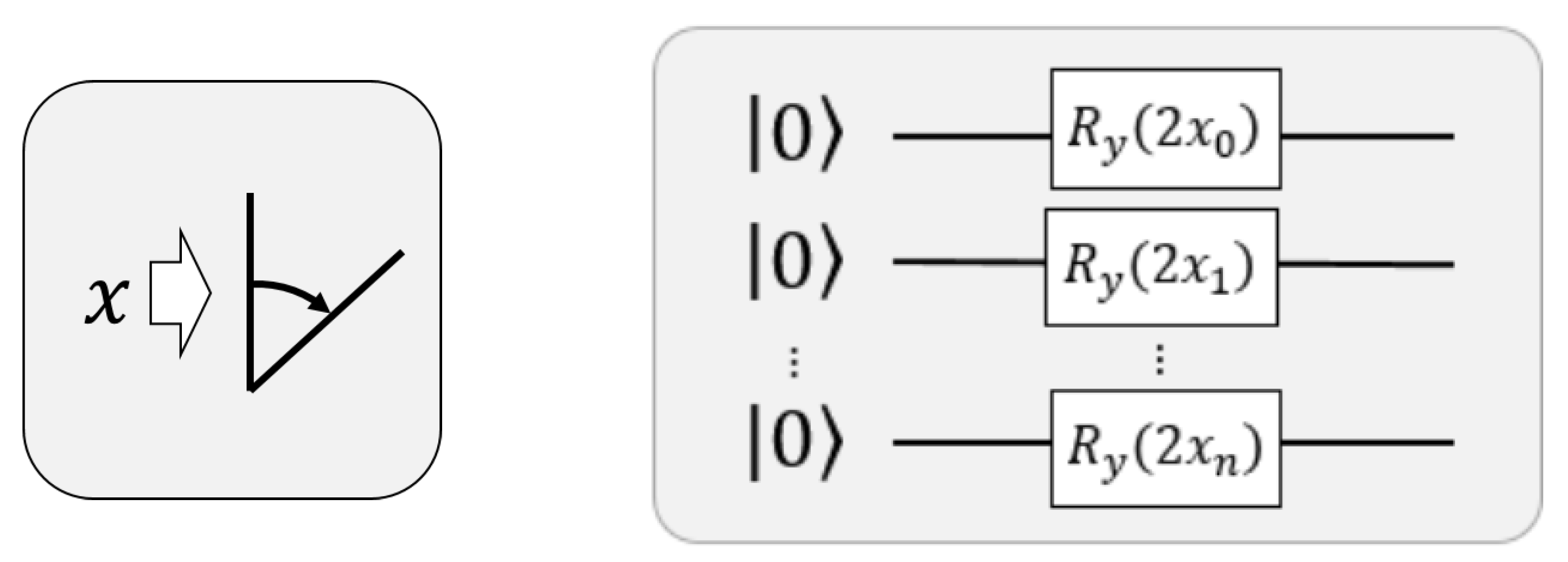

Appendix B.1. Angle Embedding

- rotation=X uses the features as angles of rotations

- rotation=Y uses the features as angles of rotations

- rotation=Z uses the features as angles of rotations

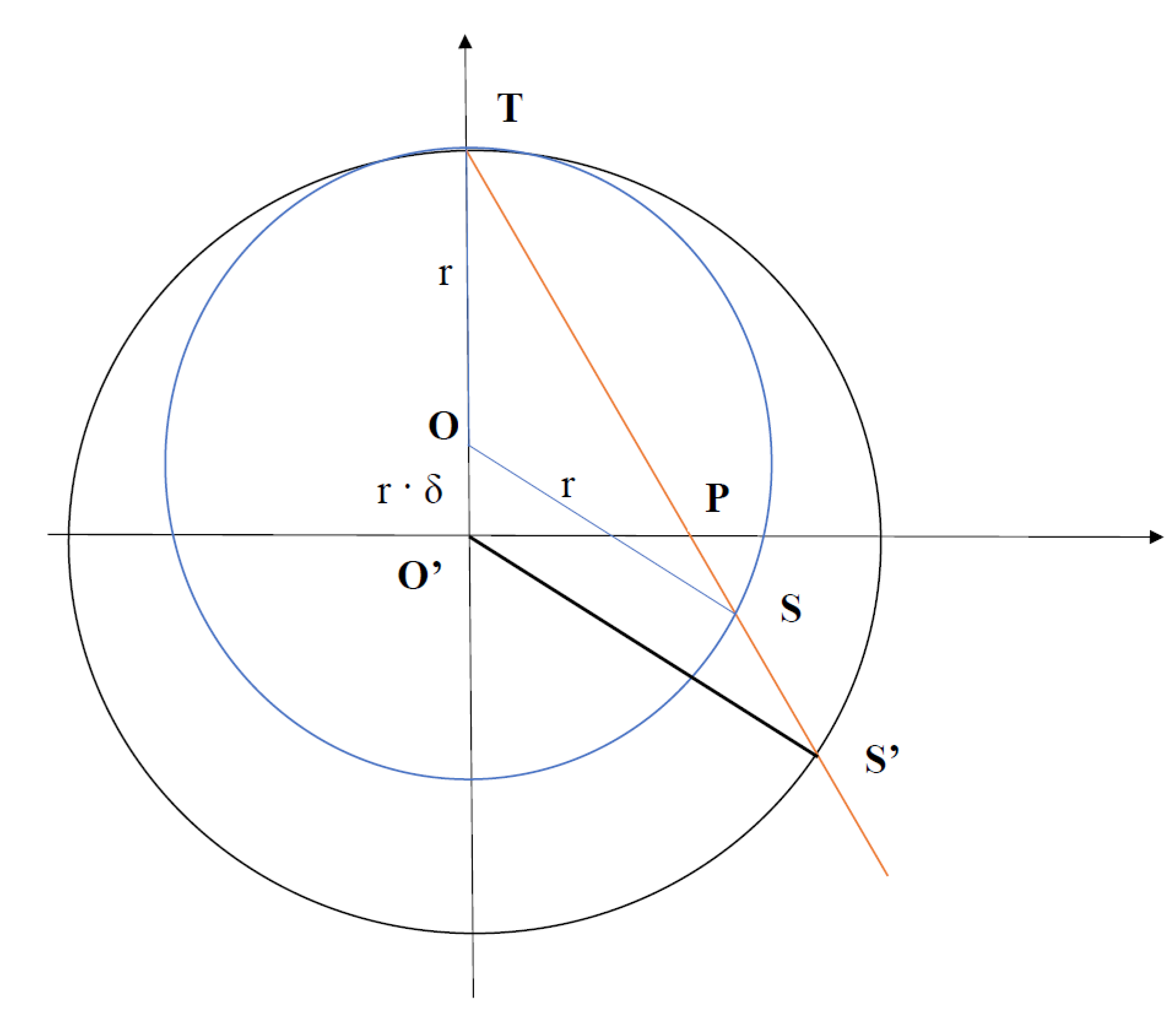

Appendix C. Stereographic Projection

Appendix C.1. Stereographic Projection for General Radius

Appendix C.2. Equivalence of displacement and scaling

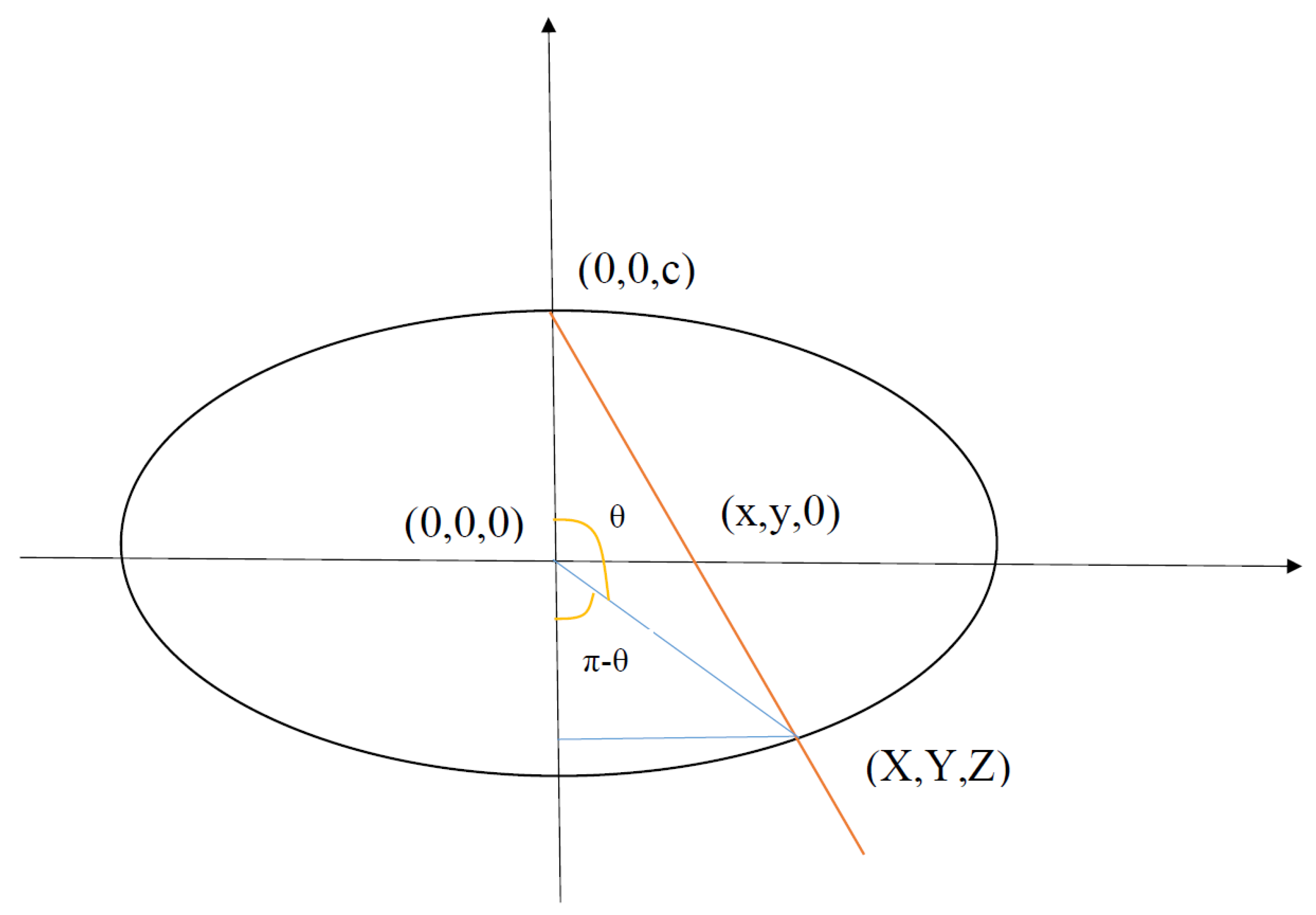

Appendix D. Ellipsoidal Embedding

Appendix E. Rotation Gates and the UGate

Appendix F. Distance Estimation through the SWAP test

References

- Arute, F.; Arya, K.; Babbush, R.; Bacon, D.; Bardin, J.; Barends, R.; Biswas, R.; Boixo, S.; Brandao, F.; Buell, D.; et al. Quantum Supremacy using a Programmable Superconducting Processor. Nature 2019, 574, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuld, M.; Petruccione, F. Supervised Learning with Quantum Computers; Quantum Science and Technology, Springer International Publishing, 2018.

- M. Schuld, I. Sinayskiy, F.P. An introduction to quantum machine learning. arXiv:1409.3097 [quant-ph] 2014.

- Kerenidis, I.; Prakash, A. Quantum Recommendation Systems. In Proceedings of the 8th Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference (ITCS 2017); Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics (LIPIcs), Vol. 67; Papadimitriou, C.H., Ed.; Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik: Dagstuhl, Germany, 2017; pp. 49–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerenidis, I.; Landman, J.; Luongo, A.; Prakash, A. q-means: A quantum algorithm for unsupervised machine learning. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1812.03584. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, S.; Mohseni, M.; Rebentrost, P. Quantum algorithms for supervised and unsupervised machine learning. arXiv, 2013; arXiv:1307.0411. [Google Scholar]

- Pakala, L.; Schmauss, B. Non-linear mitigation using carrier phase estimation and k-means clustering. In Proceedings of the Photonic Networks; 2015, 16. ITG Symposium. VDE; pp. 1–5.

- Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Gao, M.; Shen, G. K-means-clustering-based fiber nonlinearity equalization techniques for 64-QAM coherent optical communication system. Optics express 2017, 25, 27570–27580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E. Quantum Principal Component Analysis Only Achieves an Exponential Speedup Because of Its State Preparation Assumptions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 060503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Microsystems, B. Digital modulation efficiencies.

- Jr., L.E.F. Electronics Explained: Fundamentals for Engineers, Technicians, and Makers, Newnes, 2018.

- Tang, E. A Quantum-Inspired Classical Algorithm for Recommendation Systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 51st Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing; STOC 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E. Quantum Principal Component Analysis Only Achieves an Exponential Speedup Because of Its State Preparation Assumptions. Physical Review Letters 2021, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, N.H.; Lin, H.H.; Wang, C. Quantum-inspired sublinear classical algorithms for solving low-rank linear systems. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1811.04852. [Google Scholar]

- Gilyén, A.; Lloyd, S.; Tang, E. Quantum-inspired low-rank stochastic regression with logarithmic dependence on the dimension. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1811.04909. [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola, J.M.; Delgado, A.; Bardhan, B.R.; Lloyd, S. Quantum-inspired algorithms in practice. Quantum 2020, 4, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyn, J.M.; Rossi, Z.M.; Tan, A.K.; Chuang, I.L. A grand unification of quantum algorithms. arXiv, 2021; arXiv:2105.02859. [Google Scholar]

- Kopczyk, D. Quantum machine learning for data scientists. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1804.10068. [Google Scholar]

- Esma Aimeur, G.B.; Gambs, S. Quantum clustering algorithms. ICML ’07: Proceedings of the 24th international conference on Machine learning June 2007, 2007; 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cruise, J.R.; Gillespie, N.I.; Reid, B. Practical Quantum Computing: The value of local computation. arXiv, 2020; arXiv:2009.08513. [Google Scholar]

- Johri, S.; Debnath, S.; Mocherla, A.; Singh, A.; Prakash, A.; Kim, J.; Kerenidis, I. Nearest centroid classification on a trapped ion quantum computer. npj Quantum Information 2021, 7, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Awan, A.J.; Vall-Llosera, G. K-Means Clustering on Noisy Intermediate Scale Quantum Computers. arXiv, 2019; arXiv:1909.12183. [Google Scholar]

- Cortese, J.A.; Braje, T.M. Loading classical data into a quantum computer. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1803.01958. [Google Scholar]

- Chia, N.H.; Gilyén, A.; Li, T.; Lin, H.H.; Tang, E.; Wang, C. Sampling-based sublinear low-rank matrix arithmetic framework for dequantizing Quantum machine learning. Proceedings of the 52nd Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrazola, J.M.; Delgado, A.; Bardhan, B.R.; Lloyd, S. Quantum-inspired algorithms in practice. Quantum 2020, 4, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, N.H.; Gilyén, A.; Lin, H.H.; Lloyd, S.; Tang, E.; Wang, C. Quantum-Inspired Algorithms for Solving Low-Rank Linear Equation Systems with Logarithmic Dependence on the Dimension. In Proceedings of the 31st International Symposium on Algorithms and Computation (ISAAC 2020); Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics (LIPIcs), Vol. 181; Cao, Y.; Cheng, S.W.; Li, M., Eds.; Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik: Dagstuhl, Germany, 2020; pp. 47–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergioli, G.; Santucci, E.; Didaci, L.; Miszczak, J.A.; Giuntini, R. A quantum-inspired version of the nearest mean classifier. Soft Computing 2018, 22, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergioli, G.; Bosyk, G.M.; Santucci, E.; Giuntini, R. A quantum-inspired version of the classification problem. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 2017, 56, 3880–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhi, G.M.; Messikh, A. Simple quantum circuit for pattern recognition based on nearest mean classifier. International Journal on Perceptive and Cognitive Computing 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguemto, S.; Leyton-Ortega, V. Re-QGAN: an optimized adversarial quantum circuit learning framework, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Eybpoosh, K.; Rezghi, M.; Heydari, A. Applying inverse stereographic projection to manifold learning and clustering. Applied Intelligence 2022, 52, 4443–4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggiali, A.; Berti, A.; Bernasconi, A.; Del Corso, G.; Guidotti, R. Quantum Clustering with k-Means: a Hybrid Approach. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2212.06691. [Google Scholar]

- de Veras, T.M.L.; de Araujo, I.C.S.; Park, D.K.; da Silva, A.J. Circuit-Based Quantum Random Access Memory for Classical Data With Continuous Amplitudes. IEEE Transactions on Computers 2021, 70, 2125–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, K.; Feinerer, I.; Kober, M.; Buchta, C. Spherical k-Means Clustering. Journal of Statistical Software 2012, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, X.; Ding, X.; Shan, Z. An Enhanced Quantum K-Nearest Neighbor Classification Algorithm Based on Polar Distance. Entropy 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlfors, L.V. Complex Analysis, 2 ed.; McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1966.

- Fanizza, M.; Rosati, M.; Skotiniotis, M.; Calsamiglia, J.; Giovannetti, V. Beyond the Swap Test: Optimal Estimation of Quantum State Overlap. Physical Review Letters 2020, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plesch, M.; Brukner, Č. Quantum-state preparation with universal gate decompositions. Physical Review A 2011, 83, 032302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigold, M.; Barzen, J.; Leymann, F.; Salm, M. Expanding Data Encoding Patterns For Quantum Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 18th International Conference on Software Architecture Companion (ICSA-C); 2021; pp. 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quantum Computing Patterns. https://quantumcomputingpatterns.org/. Accessed: 2021-10-30.

- Roy, B. All about Data Encoding for Quantum Machine Learning.https://medium.datadriveninvestor.com/all-about-data-encoding-for-quantum-machine-learning-2a7344b1dfef, 2021.

- Harry Buhrman, Richard Cleve, J.W.; de Wolf, R. Quantum fingerprinting. arXiv:quant-ph/0102001.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).