Submitted:

26 April 2023

Posted:

27 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Olive Fruits

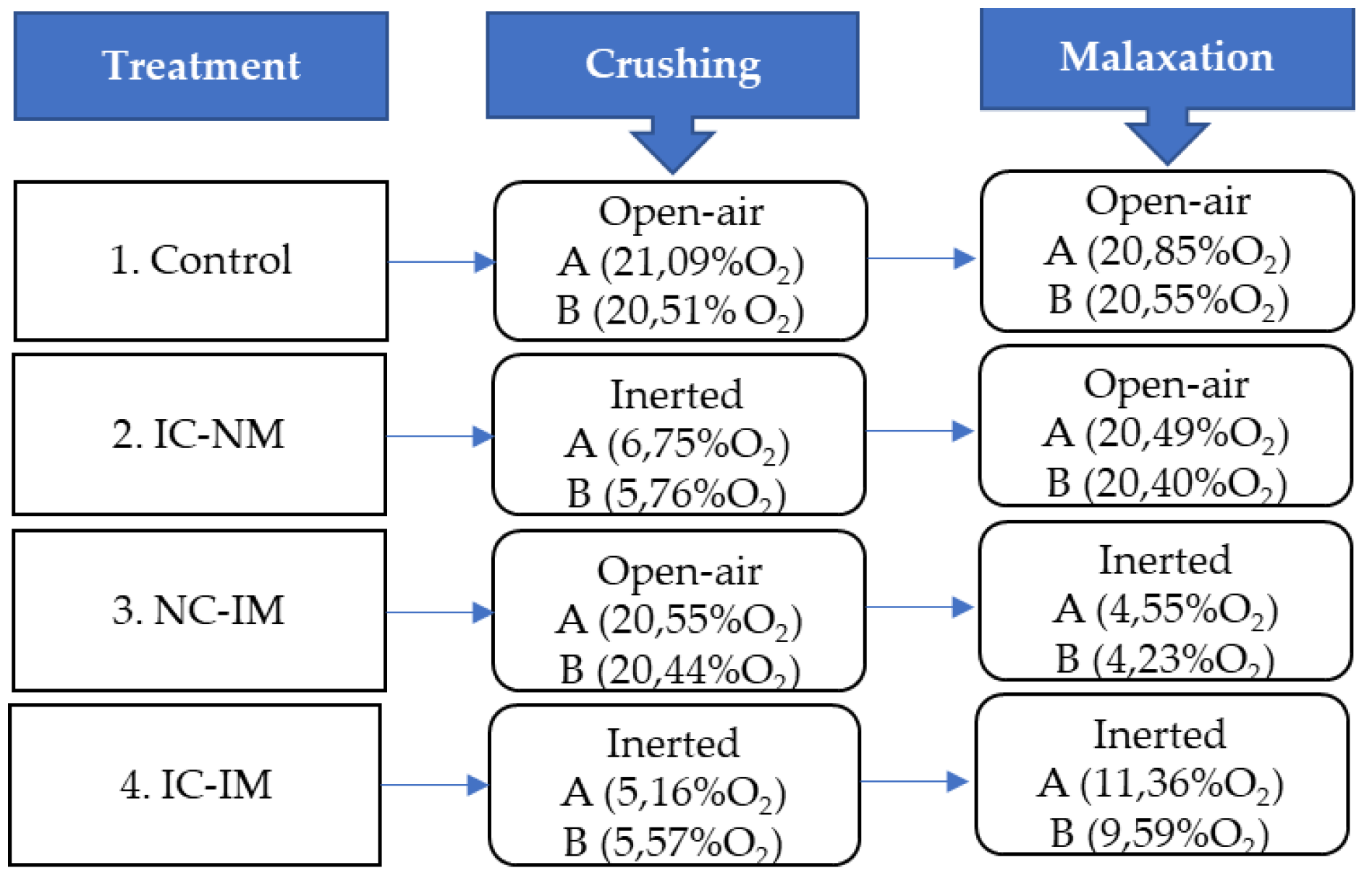

2.2. Olive Oil Extraction and Treatments

2.3. Chemicals

2.4. Quality Parameters Analysis

2.5. Minor Compounds

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Quality Parameters

| Trial | HD | MI | WM (g) |

FMO (%) |

DMO (%) |

Moisture (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 03/12/2021 | 3.76 | 3.09 | 19.45 | 56.82 | 43.18 |

| B | 15/12/2021 | 3.36 | 2.40 | 18.58 | 52.20 | 47.80 |

| Parameter*. | A Trial | |||

| Control | T1 (IC-NM) | T2 (NC-IM) | T3 (IC-IM) | |

| Free acidity | 0.22±0.03 | 0.20±0.03 | 0.18±0.00 | 0.20±0.03 |

| Peroxide value | 4.56±0.52 | 4.73±0.25 | 4.25±0.29 | 4.24±0.29 |

| K232nm | 1.70±0.11 | 1.64±0.04 | 1.58±0.01 | 1.65±0.03 |

| K270nm | 0.15±0.04 | 0.11±0.03 | 0.10±0.01 | 0.13±0.01 |

| B Trial | ||||

| Control | T1 (IC-NM) | T2 (NC-IM) | T3 (IC-IM) | |

| Free acidity | 0.24±0.00 | 0.23±0.00 | 0.22±0.00 | 0.21±0.00 |

| Peroxide value | 5.56±0.00 | 4.99±0.02 | 5.17±0.63 | 4.98±0.02 |

| K232nm | 1.75±0.02 | 1.79±0.06 | 1.76±0.03 | 1.74±0.02 |

| K270nm | 0.15±0.00* | 0.16±0.01 | 0.18±0.01 | 0.18±0.01 |

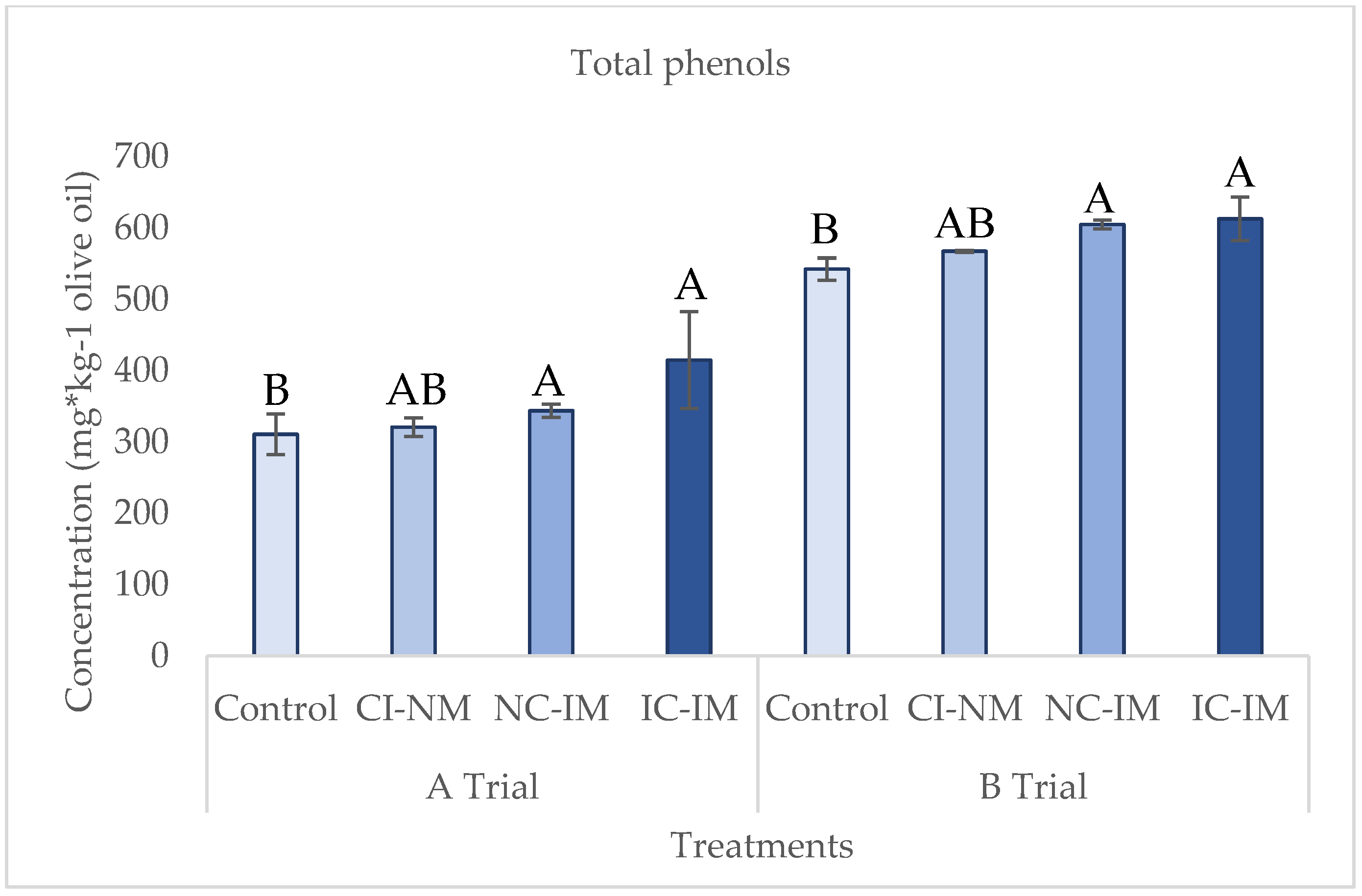

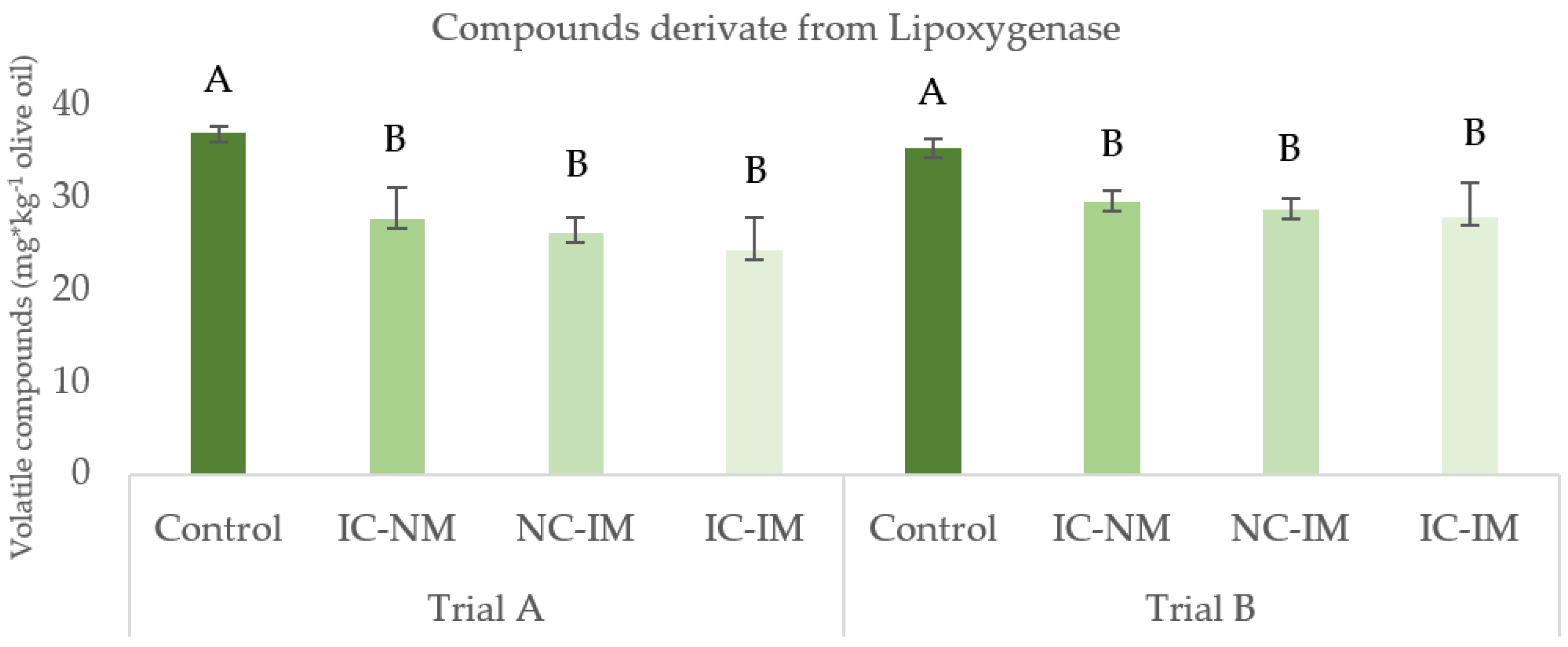

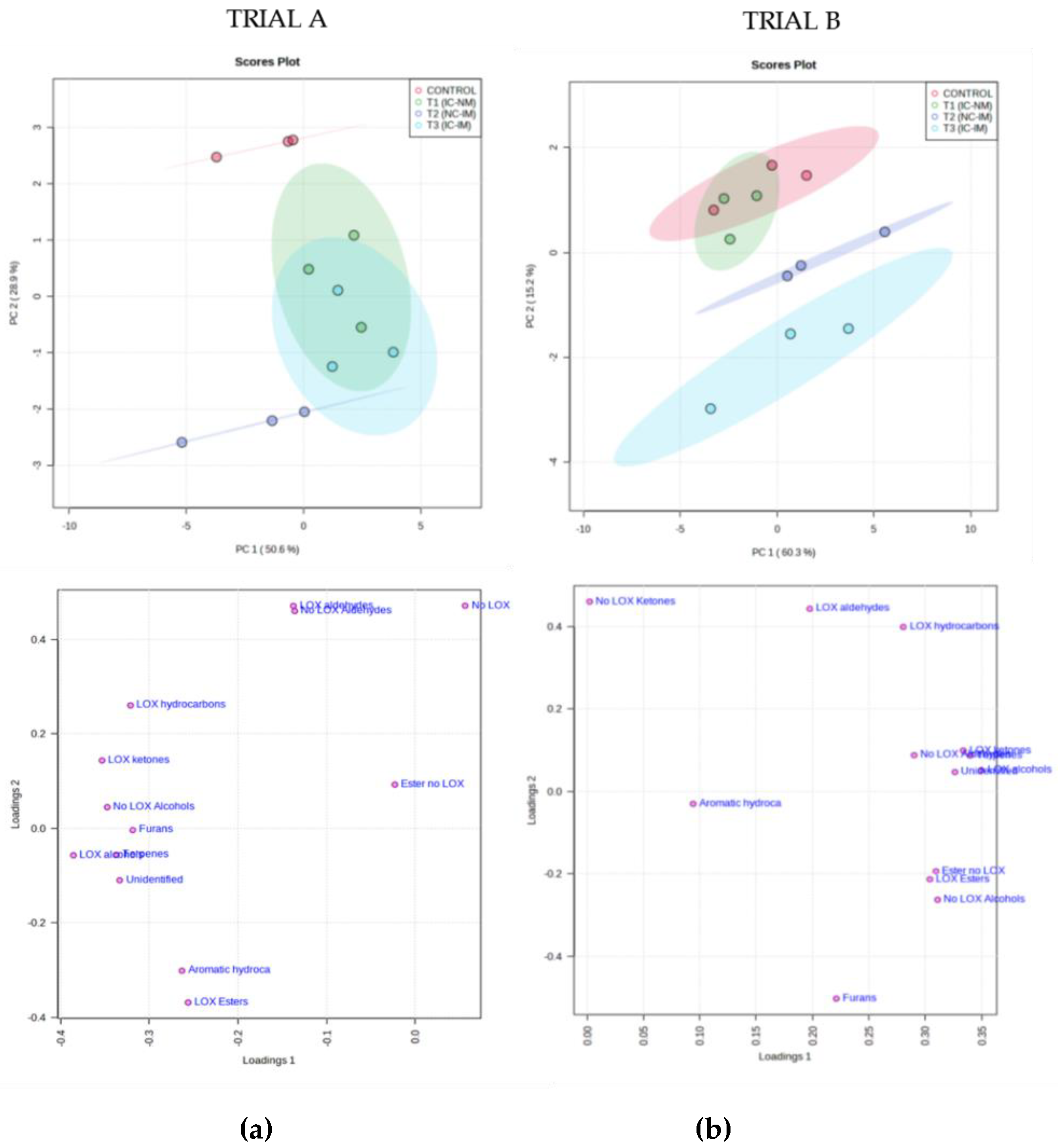

3.2. Effect of the Treatments of Reduction of Oxygen on Minor Fraction of Virgin Olive Oil

| A Trial | ||||

| Control | T1 (IC-NM) | T2 (NC-IM) | T3 (IC-IM) | |

| α-tocopherol | 257.24±8.11bc | 254.93±1.62c | 268.74±4.63ab | 271.57±4.33a |

| β-tocopherol | 6.34±0.33a | 6.05±0.04a | 6.19±0.45ab | 6.23±017a |

| ɣ-tocopherol | 16.51±0.68a | 16.07±0.07a | 17.00±0.44ab | 16.95±0.31a |

| Total | 280.10±9.09ab | 277.05±1.65b | 291.92±4.72ab | 294.75±4.61a |

| B Trial | ||||

| Control | T1 (IC-NM) | T2 (NC-IM) | T3 (IC-IM) | |

| α-tocopherol | 352.46±2.62a | 356.94±1.84a | 357.46±2.41a | 355.55±2.54a |

| β-tocopherol | 6.81±0.17a | 6.84±0.20a | 6.77±0.04a | 6.96±0.04a |

| ɣ-tocopherol | 14.39±0.12a | 14.80±0.52a | 14.58±0.12a | 14.14±0.05a |

| Total | 373.66±2.83a | 378.59±2.26a | 378.82±2.36a | 376.66±2.56a |

| A Trial | ||||

| Control | T1 (IC-NM) | T2 (NC-IM) | T3 (IC-IM) | |

| Carotenes | 2.16±0.05c | 2.98±0.17a | 2.93±0.08a | 2.52±0.11b |

| Chlorophylls | 1.21±0.10a | 1.73±0.20a | 1.61±0.23a | 1.33±0.26a |

| B Trial | ||||

| Control | T1 (IC-NM) | T2 (NC-IM) | T3 (IC-IM) | |

| Carotenes | 7.94±0.11b | 8.36±0.16ab | 8.72±0.14a | 8.77±0.36a |

| Chlorophylls | 6.39±0.18c | 7.32±0.32b | 8.15±0.11ab | 8.81±0.54a |

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Angerosa, F. Influence of volatile compounds on virgin olive oil quality avaluated by analytical approaches and sensor panels. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 2002, 104, 639–660. https://doi.org/10.1002/1438-9312(200210)104:9/10<639::AID-EJLT639>3.0.CO;2-U. [CrossRef]

- Visioli, F.; Franco, M.; Toledo, E.; Luchsinger, J.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A. Olive oil and prevention of chronic diseases: Summary of an International conference. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 649–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2018.04.004. [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, L.; Migliorini, M.; Mulinacci, N. Virgin olive oil volatile compounds: Composition, sensory characteristics, analytical approaches, quality control, and authentication. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 2013–2040. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07744. [CrossRef]

- Genovese, A.; Caporaso, N.; Sacchi, R. Flavor chemistry of virgin olive oil: An overview. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11041639. [CrossRef]

- European Union Commission Regulation (CEE) No 2568/91; 1991; p. 83;

- R.432/2012 Commission Regulation (EU) No 432/2012 of 16 May 2012 establishing a list of permitted health claims made on foods, other than those referring to the reduction of disease risk and to children’s development and health; 2012;

- Bendini, A.; Cerretani, L.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Lercker, G. Phenolic molecules in virgin olive oils: A survey of their sensory properties, health effects, antioxidant activity and analytical methods. An overview of the last decade. Molecules 2007, 12, 1679–1719. https://doi.org/10.3390/12081679. [CrossRef]

- El Riachy, M.; Priego-Capote, F.; León, L.; Rallo, L.; Luque de Castro, M.D. Hydrophilic antioxidants of virgin olive oil. Part 1: Hydrophilic phenols: A key factor for virgin olive oil quality. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2011, 113, 678–691. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.201000400. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-López, C.; Carpena, M.; Lourenço-lopes, C.; Gallardo-Gomez, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-gandara, J. Bioactive Compounds and Quality of Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Food 2020, 9, doi:doi:10.3390/foods9081014. [CrossRef]

- Velasco, J.; Dobarganes, C. Oxidative stability of virgin olive oil. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2002, 104, 661–676. https://doi.org/10.1002/1438-9312(200210)104:9/10<661::AID-EJLT661>3.0.CO;2-D. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Bejaoui, M.A.; Herrera, M.P.A.; Márquez, A.J.; Maza, G.B. Application of oxygen during olive fruit crushing impacts on the characteristics and sensory profile of the virgin olive oil. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2016, 118. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.201500276. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Romero, C.; Pérez, A.G.; Sanz, C. Oxygen concentration affects volatile compound biosynthesis during virgin olive oil production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 4681–4685. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf8004838. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Pérez, A.G.; Sanz, C. Synthesis of aroma compounds of virgin olive oil: Significance of the cleavage of polyunsaturated fatty acid hydroperoxides during the oil extraction process. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2013.03.045. [CrossRef]

- Olías, J.M.; Pérez, A.G.; Rios, J.J.; Sanz, L.C. Aroma of virgin olive oil: biogenesis of the “green” odor notes. J. Agric. food Chem. 1993, 41, 2368–2373. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf00036a029. [CrossRef]

- Angerosa, F.; Camera, L.; d’Alessandro, N.; Mellerio, G. Characterization of Seven New Hydrocarbon Compounds Present in the Aroma of Virgin Olive Oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 648–653. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf970352y. [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, R.; Romero-Segura, C.; Sanz, C.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Pérez, A.G. Role of polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase in shaping the phenolic profile of virgin olive oil. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 629–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2010.12.023. [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; Romaniello, R.; Zagaria, R.; Tamborrino, A. Development of a prototype malaxer to investigate the influence of oxygen on extra-virgin olive oil quality and yield, to define a new design of machine. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 118, 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2013.12.002. [CrossRef]

- Catania, P.; Vallone, M.; Pipitone, F.; Inglese, P.; Aiello, G.; La Scalia, G. An oxygen monitoring and control system inside a malaxation machine to improve extra virgin olive oil quality. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 114, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2012.10.009. [CrossRef]

- Vezzaro, A.; Boschetti, A.; Dell’Anna, R.; Canteri, R.; Dimauro, M.; Ramina, A.; Ferasin, M.; Giulivo, C.; Ruperti, B. Influence of olive (cv Grignano) fruit ripening and oil extraction under different nitrogen regimes on volatile organic compound emissions studied by PTR-MS technique. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 399, 2571–2582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-010-4636-1. [CrossRef]

- Masella, P.; Parenti, A.; Spugnoli, P.; Calamai, L. Malaxation of olive paste under sealed conditions. JAOCS, J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2011, 88, 871–875. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11746-010-1739-y. [CrossRef]

- Tamborrino, A.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Leone, A.; Amirante, P.; Paice, A.G. The Malaxation Process: Influence on Olive Oil Quality and the Effect of the Control of Oxygen Concentration in Virgin Olive Oil. In Olives and Olive Oil in Health and Disease Prevention; Preedy, V.R., Watson, R.R., Eds.; 2010; pp. 77–83.

- Servili, M.; Taticchi, A.; Esposto, S.; Urbani, S.; Selvaggini, R.; Montedoro, G. Influence of the decrease in oxygen during malaxation of olive paste on the composition of volatiles and phenolic compounds in virgin olive oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 10048–10055. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf800694h. [CrossRef]

- Parenti, A.; Spugnoli, P.; Masella, P.; Calamai, L. Influence of the extraction process on dissolved oxygen in olive oil. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2007, 109, 1180–1185. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.200700088. [CrossRef]

- Parenti, A.; Spugnoli, P.; Masella, P.; Calamai, L. Carbon dioxide emission from olive oil pastes during the transformation process: Technological spin offs. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 222, 521–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-005-0003-4. [CrossRef]

- Parenti, A.; Spugnoli, P.; Masella, P.; Calamai, L.; Pantani, O.L. Improving olive oil quality using CO2 evolved from olive pastes during processing. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2006, 108, 904–912. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.200600182. [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, M.; Mugelli, M.; Cherubini, C.; Viti, P.; Zanoni, B. Influence of O2 on the quality of virgin olive oil during malaxation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 2140–2146. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.2588. [CrossRef]

- Servili, M.; Selvaggini, R.; Taticchi, A.; Esposto, S.; Montedoro, G. Air exposure time of olive pastes during the extraction process and phenolic and volatile composition of virgin olive oil. JAOCS, J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2003, 80, 685–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11746-003-0759-0. [CrossRef]

- Veneziani, G.; García-González, D.L.; Esposto, S.; Nucciarelli, D.; Taticchi, A.; Boudebouz, A.; Servili, M. Effect of Controlled Oxygen Supply during Crushing on Volatile and Phenol Compounds and Sensory Characteristics in Coratina and Ogliarola Virgin Olive Oils. 2023.

- Iqdiam, B.M.; Abuagela, M.O.; Marshall, S.M.; Yagiz, Y.; Goodrich-Schneider, R.; Baker, G.L.; Welt, B.A.; Marshall, M.R. Combining high power ultrasound pre-treatment with malaxation oxygen control to improve quantity and quality of extra virgin olive oil. J. Food Eng. 2019, 244, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.09.013. [CrossRef]

- Vallone, M.; Aiello, G.; Bono, F.; De Pasquale, C.; Presti, G.; Catania, P. An Innovative Malaxer Equipped with SCADA Platform for Improving Extra Virgin Olive Oil Quality. Sensors 2022, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22062289. [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; Romaniello, R.; Mangialardi, G.I.; Tamborrino, A. Modified atmosphere in head space of extra virgin olive oil tanks: Testing a prototype integrated storage system. Acta Hortic. 2015, 1071, 319–326.

- Sanmartin, C.; Venturi, F.; Macaluso, M.; Nari, A.; Quartacci, M.F.; Sgherri, C.; Flamini, G.; Taglieri, I.; Ascrizzi, R.; Andrich, G.; et al. Preliminary Results About the Use of Argon and Carbon Dioxide in the Extra Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO) Storage to Extend Oil Shelf Life: Chemical and Sensorial Point of View. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2018, 120. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.201800156. [CrossRef]

- Angeloni, G.; Spadi, A.; Corti, F.; Guerrini, L.; Calamai, L.; Parenti, A.; Masella, P. Investigation of the Effectiveness of a Vertical Centrifugation System Coupled with an Inert Gas Dosing Device to Produce Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-022-02884-3. [CrossRef]

- International Olive Council Guide for the Determination of the characteristics of oil-olives; 2011; p. 41;

- IOC (INTERNATIONAL OLIVE COUNCIL) Trade standard applying to olive oils and olive pomace oils. Int. Olive Counc. 2022, 15, 1–17.

- International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Commission on Oils, F. and D. Standard Methods for the Analysis of Oils, Fats and Derivatives 1st Supplement to the 7th Edition International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Commission on Oils, Fats and Derivatives. 1992, 151.

- Mínguez-Mosquera, M.I.; Rejano-Navarro, L.; Gandul-Rojas, B.; Sánchez-Gómez, A.H.; Garrido-Fernández, J. Color-pigment correlation in virgin olive oil. J. Food Qual. 1991, 69, 332–336.

- Vázquez-Roncero, A.; Janer del Valle, C.; Janer del Valle, M.L. Determinación de polifenoles totales del aceite de oliva. Grasas Aceites 1973, 24, 350–357.

- Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Bejaoui, M.A.; Quintero-Flores, A.; Jiménez, A.; Beltrán, G. “Biosynthesis of volatile compounds by hydroperoxide lyase enzymatic activity during virgin olive oil extraction process.” Food Res. Int. 2018, 111, 220–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2018.05.024. [CrossRef]

- Sansone, S.A.; Fan, T.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J.L.; Hardy, N.W.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R.; Kristal, B.S.; Lindon, J.; Mendes, P.; Morrison, N.; et al. The metabolomics standards initiative. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 844–848. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt0807-846b WE - Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED). [CrossRef]

- Molina, F.; Cano, J.; Navas, J.F.; De La Rosa, R.; León Moreno, L. Determinación del momento óptimo de recolección en olivo; Córdoba, 2021;

- Deiana, P.; Filigheddu, M.R.; Dettori, S.; Culeddu, N.; Dore, A.; Molinu, M.G.; Santona, M. The chemical composition of Italian virgin olive oils. In Olives and Olive Oil in Health and Disease Prevention; INC, 2020; pp. 51–62 ISBN 9780128195284.

- Fadda, C.; Del Caro, A.; Sanguinetti, A.M.; Urgeghe, P.P.; Vacca, V.; Arca, P.P.; Piga, A. Changes during storage of quality parameters and in vitro antioxidant activity of extra virgin monovarietal oils obtained with two extraction technologies. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 1542–1548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.03.076. [CrossRef]

- Squeo, G.; Tamborrino, A.; Pasqualone, A.; Leone, A.; Paradiso, V.M.; Summo, C.; Caponio, F. Assessment of the Influence of the Decanter Set-up During Continuous Processing of Olives at Different Pigmentation Index. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 592–602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-016-1842-7. [CrossRef]

- Gandul-Rojas, B.; Gallardo-Guerrero, L.; Roca, M.; Aparicio-Ruiz, R. Chromatographic Methodologies: Compounds for Olive Oil Color Issues BT - Handbook of Olive Oil: Analysis and Properties. In; Aparicio, R., Harwood, J., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2013; pp. 219–259 ISBN 978-1-4614-7777-8.

- García-Rodríguez, R.; Romero-Segura, C.; Sanz, C.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Pérez, A.G. Role of polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase in shaping the phenolic profile of virgin olive oil. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2010.12.023. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).