1. Introduction

Wood polymer composites (WPC) are widely used engineering materials that offer sustainable alternatives to natural wood products. WPCs, which can be produced using forest by-products and recycled polymers, allow the production of environmentally friendly, semi-green materials [

1,

2,

3,

4]. At the same time, WPC offers sufficient strength properties for structural applications, while also offering high resistance to weather conditions and biological degradation[

5]. Due to WPC's physical characteristics, which include low moisture content, thickness swelling (TS), and water absorption (WA), it may be used for both indoor and outdoor applications [

6].

Usage areas of WPCs are changing and expanding rapidly depending on consumer preferences. The usage areas of WPCs have increased due to the developing production methods and material industry. Today, WPCs can be preferred in the applications of many load-bearing systems, such as marine structures and sports equipment, especially outdoor applications. The main problem restricting the applications for WPC is their poor mechanical performance, brought on by the incompatibility of the wood with the polymer matrix. This frequently results in poor stress transfers across composites, which reduces their mechanical characteristics and reduces their ability to resist moisture [

7].

By adding nanoparticles as additives, WPCs can have better physical, mechanical, thermal, and surface properties. For the production of polymer nanocomposites, a variety of nanomaterials, including SiO

2, TiO

2, MgO, zinc oxide (ZnO), graphene, carbon nanotubes, and ZnO, can be utilized. When ZnO nanoparticles are added to WPCs, it can give us new information about how to improve the properties of composites. There are several reports on the use of ZnO nanoparticles in the preparation of WPCs. However, production methods of WPCs are important for improving the interfacial interaction between ZnO nanoparticles, wood, and plastics [

8]. Using the right method of production is very important if you want to make sure that the nanoparticles are spread out evenly in the composite. In this way, it contributes to the improvement of the physical, mechanical, and surface properties as well as the load transfer.

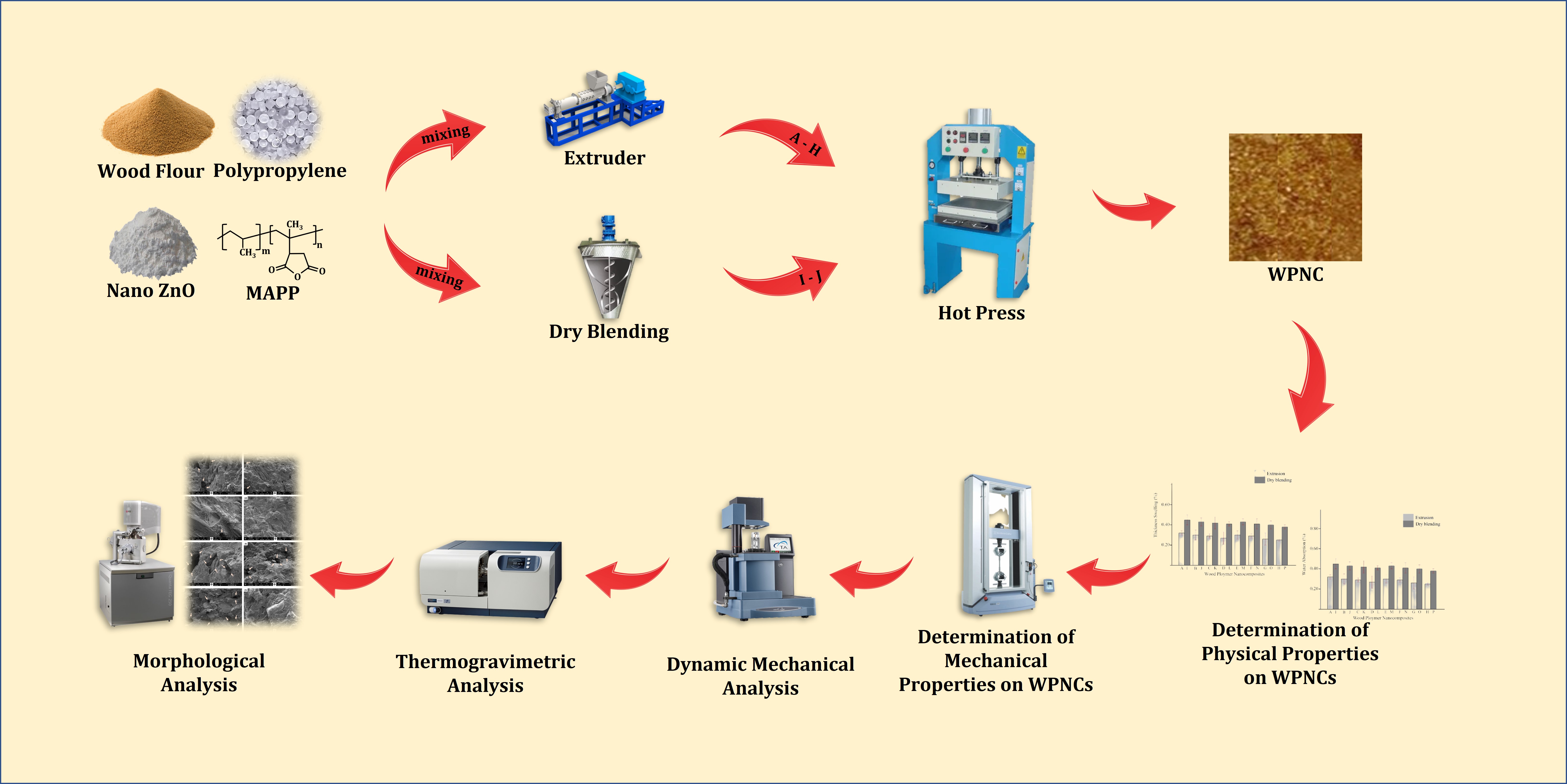

In this study, wood / polypropylene (PP) / nano ZnO nanocomposites with different nano ZnO contents were prepared by extrusion and dry blending to evaluate the appropriate methods for these nanocomposites. To meet this objective, nanocomposites fabricated by two different methods have been extensively characterized by different analyzes, including physical and mechanical tests, scanning electron microscope (SEM) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). This study's primary objective is to determine the effect of manufacturing method on the physical, mechanical, thermal and morphological properties of wood plastic nanocomposites (WPNC). In addition, the effect of nano ZnO on improving the above-mentioned characteristics of WPNCs was also investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

Black pine (

Pinus nigra J.F.Arnold subsp.) wood flour (WF) was supplied by a local WPC plant in Tekirdağ, Turkey. The PP was acquired from Borealis group in Austria and has a density of 0.90 g/cm

3. It has a 170 °C melt point and a 2.5 g/10 min melting flow index at 230 °C. ZnO was purchased from the Grafen Company in Turkey. Some of the mechanical and physical characteristics of nano ZnO are shown in

Table 1. The coupling agent, maleic anhydride grafted polypropylene (MAPP), was bought from Pluss Polymers Gurgaon in India.

2.1. Wood Polymer Nanocomposites Preparation

WF was first dried for 1 day at 103±2 °C in a laboratory type oven before being used to preparation WPNCs. Then, the dried WF, PP, ZnO, and with and without MAPP (

Table 2) were blended for 10 minutes with using a high-speed mixer.

This mixture was pelletized in an extruder at a temperature of 170 – 200 °C. The pellets were injected at 180 °C with a pressure of 3 to 5 MPa in an injection molding machine. The remaining pellet mixture was weighed and then formed into an aluminum caul plate mat using a 250x250 mm2 frame. A computer-controlled press was used to apply hot pressing to the mats. The maximum press pressure was 45 N/cm2, the press temperature was 210 °C, and the total press cycle was 500 s.

Following the hot-pressing cycle, the ready panel was moved from the hot press to a climate-controlled room for cooling. Before characterization, the samples were conditioned in a climate room at 23±2 °C and 65±2% relative humidity.

2.2. Physical Properties

The tests were performed in accordance with ISO 62 for thickness swelling and water absorption. The samples utilized for this purpose were 5x5 mm in size. The samples that were conditioned in a climate room at 23±2 °C temperature and 50±5% relative humidity was measured after being left in water for 1 and 28 days.

2.3. Mechanical Properties

For the flexural and tensile tests, which were done according to ISO 178 and ISO 527, a Shimadzu universal testing machine (Model AG-IC 20/50 KN STD) was used. The tests were run at 5 mm/min crosshead speeds. Both flexural and tensile strength tests were conducted on seven replications.

2.4. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

TA- DMA Q800 Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer was used to analyze the DMA characteristics of the WPNCs in the 0 to 150 °C temperature range. The specimens, which were evaluated in a nitrogen environment at a fixed frequency of 1 Hz and a heating rate of 5 °C min-1, had dimensions of 20 mm by 10 mm by 20 mm. In total three samples were tested in each group to analyze the dynamical mechanical behaviors.

2.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA analyses were carried out using a Hitachi STA7300. For TGA analysis, nitrogen gas was utilized at a flow rate of 20 mL/min. In this experiment, the samples were heated at 25 °C/min from room temperature to 500 °C.

2.6. Morphology of Fracture Surface

The WPNC bars were frozen in liquid nitrogen before being snapped in half for SEM analysis. A scanning electron microscope (Model: FEO Quanta FEG 250) was used to examine the surfaces directly.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physical Properties of WPNCs

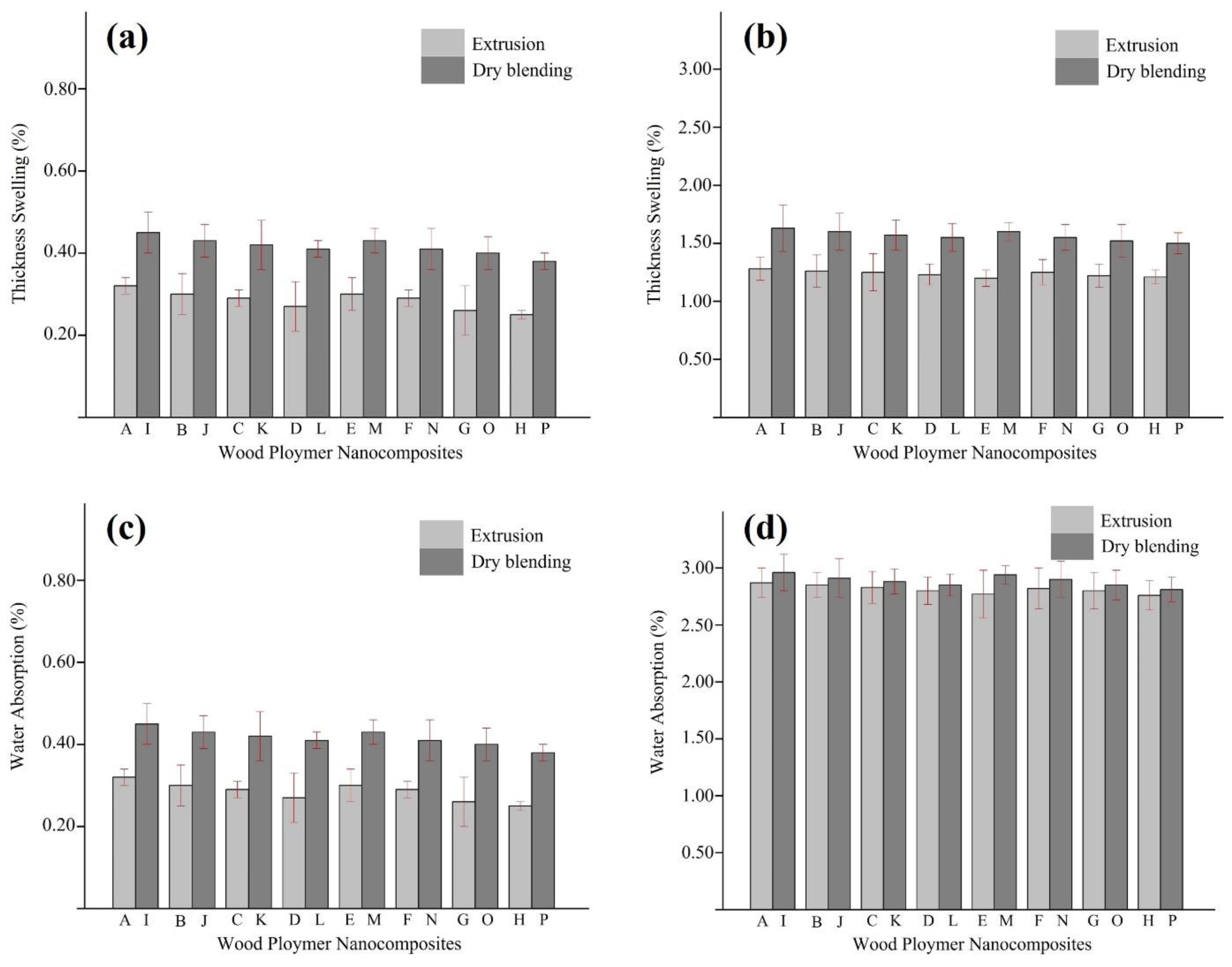

Figure 1 represents some of the physical characteristics of ZnO reinforced WPNCs. Due to ZnO's hydrophobic nature, incorporation of ZnO nanoparticles into the composite structure led to low TS and WA values, as expected. The physical characteristics of the WPNCs significantly improved with ZnO nanoparticle loading. The control samples (0 wt% ZnO extrusion and 0 wt% the ZnO dry blending) without the ZnO had the highest TS with values of 0.32% and 0.45% respectively, while the lowest TS with value of 0.25% and 0.38% was found for the samples containing 5 wt% ZnO with MAPP- extrusion and 5 wt% ZnO with MAPP- dry blending, respectively.

The merging of nanoparticles into the composite structure using the dry blending method resulted in poor dispersion of ZnO nanoparticles. This situation caused a significant increase in the TS of WPNCs produced using the dry blending method. By contrast, the incorporation of ZnO nanoparticles into the composite structure using the extrusion blending method resulted in good dispersion of ZnO nanoparticles. From TS results, the extrusion blending process, in which ZnO/PP nanocomposite was used as a matrix, appeared to be the best method of incorporating ZnO in wood polymer nanocomposites. The WA decreased with increased ZnO nanoparticle loading in nanocomposites in experiments including 1-day and 28-day water immersion. There are more water residence sites as the ZnO nanoparticle loading increases therefore, more water is absorbed. The WA values of the extrusion method vary from 0.50% to 0.56% after 1 day submersion in water, whereas the WA values of the hot-pressing method range from 0.60% to 0.67% after 1 day submersion in water. Better WA results were obtained with the extrusion method due to the more homogeneous structure of nanocomposites reinforced with ZnO. This increases the internal bonding strength by providing better mixing. In the hot-pressing method, the behavior of PP is to accumulate at the bottom of the mat, resulting in low adhesion medium between wood flour and ZnO nanoparticles.[

9]

The addition of MAPP greatly increased the dimensional stability of the nanocomposites reinforced with ZnO. As a consequence of the MAPP's increased coherent interfacial structure between the wood flour, PP matrix, and ZnO nanoparticles, there are fewer microvoids and fiber-polypropylene-ZnO debondings in the interphase area. Similar results were also found by several researchers [

10,

11,

12]. They found that modification of the nanocomposites with MAPP increased their dimensional stability. The production method of wood polymer nanocomposites is of great importance for the effectiveness of the coupling agent. For example, the nanocomposites produced by extrusion method have a fixed content of ZnO nanoparticles loading (5 wt%). The WA and TS values were 2.76% and 1.21% lower than those of the dry blending method, respectively.

3.2. Mechanical Properties of WPNCs

Table 3 demonstrate that the results of tests called "modulus of rupture" (MOR) and "modulus of elasticity" (MOE) that were done on ZnO nanoparticle-filled WPNC samples. The loading of ZnO nanoparticles considerably increased the MOR of WPNCs. The WPNCs containing ZnO nanoparticles were stiffer than those without ZnO (

Table 3).

The control samples (0 wt% ZnO extrusion and 0 wt% ZnO dry blending) without the ZnO had the lowest MOR with a value of 41.65 N/mm

2 and 35.23 N/mm

2, respectively, while the highest MOR with value of 69.33 N/mm

2 and 42.36 N/mm

2 % was found for the samples containing 5 wt% ZnO with MAPP- extrusion and 5 wt% ZnO with MAPP- dry blending, respectively. This increases the internal bonding strength by providing better mixing. Devi and Maji [

13] examined the impact of SiO

2 on some properties of wood polymer nanocomposites and found that nanoparticles served as a reinforcing agent that bound the polymer chain inside the gallery cavity and therefore inhibited the polymer chain's mobility. Nanoparticles also improved the adhesion of wood flour to PP. The impact of decreasing polymer chain mobility and increasing adhesion resulted in a considerable improvement in mechanical characteristics [

13]. Better MOR results were obtained with the extrusion method due to the more homogeneous structure of nanocomposites reinforced with ZnO. When ZnO nanoparticles were added to the composite structure using the dry blending method, they were not dispersed very well. A similar trend was also observed for MOE. The control samples (0 wt% ZnO extrusion and 0 wt% ZnO dry blending) without ZnO had the lowest MOE with values of 5236 N/mm

2 and 4941 N/mm

2 respectively, while the highest MOE with values of 6042 N/mm

2 and 5471 N/mm

2 was obtained for the specimens including 5 wt% ZnO with MAPP- extrusion and 5 wt% ZnO with MAPP- dry blending.

Table 4 shows the tensile characteristics of WPNCs reinforced with ZnO nanoparticles. The control samples (0 wt% ZnO extrusion and 0 wt% ZnO dry blending) without ZnO had the lowest tensile strength with values of 28.3 N/mm

2 and 25.1 N/mm

2 respectively, while the highest tensile strength with values of 47.3 N/mm

2 and 32.4 N/mm

2 % was found for the samples containing 5 wt% ZnO with MAPP- extrusion and 5 wt% ZnO with MAPP- dry blending, respectively. The maximum value for tensile strength of nanocomposites reinforced with ZnO nanoparticles was obtained from the extrusion method (47.3 N/mm

2). This might be attributed to the well-distributed ZnO nanoparticles in the WF and polymer matrix. This finding is consistent with earlier research [

10,

14,

15,

16,

17].

In this study, all of the composite processing methods that used coupling agents had less strain at the highest stress levels than those that didn't. Utilizing extrusion technology to manufacture WPNCs has been studied by many researchers. This way offers various benefits, such as improved dispersion and less property deterioration [

18,

19,

20,

21].

3.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

In

Table 4, the data from each thermogram of the ZnO-reinforced WPNC samples were listed. The thermal stability of WPNC improves with ZnO nanoparticle addition. According to

Table 4, the maximum 1

st peak temperature in nanocomposite groups containing 5% of ZnO with MAPP (extrusion processing) was 309.7 °C, whereas the lowest 1

st peak temperature in nanocomposite control groups (dry blending processing) was 300.8 °C. A similar trend was observable in the 2

nd peak temperature results for nanocomposite groups.

Table 4.

Thermogravimetric analysis of WPNCs reinforced with ZnO.

Table 4.

Thermogravimetric analysis of WPNCs reinforced with ZnO.

| WPNC Code1

|

Production method |

Peak temperature

(°C) |

Total weight Loss

(%) |

Residue after 500 (°C) |

| 1st Peak |

2nd Peak |

| A |

Extrusion |

50 |

0 |

50 |

0 |

| B |

Extrusion |

50 |

1 |

49 |

0 |

| C |

Extrusion |

50 |

3 |

47 |

0 |

| D |

Extrusion |

50 |

5 |

45 |

0 |

| E |

Extrusion |

50 |

0 |

47 |

3 |

| F |

Extrusion |

50 |

1 |

46 |

3 |

| G |

Extrusion |

50 |

3 |

44 |

3 |

| H |

Extrusion |

50 |

5 |

42 |

3 |

| I |

Dry Blending |

50 |

0 |

50 |

0 |

| J |

Dry Blending |

50 |

1 |

49 |

0 |

| K |

Dry Blending |

50 |

3 |

47 |

0 |

| L |

Dry Blending |

50 |

5 |

45 |

0 |

| M |

Dry Blending |

50 |

0 |

47 |

3 |

| N |

Dry Blending |

50 |

1 |

46 |

3 |

| O |

Dry Blending |

50 |

3 |

44 |

3 |

| P |

Dry Blending |

50 |

5 |

42 |

3 |

The maximum 2

nd peak temperature was obtained to be 456.7 °C in nanocomposite groups including 5% of ZnO with MAPP (extrusion processing), while the minimum 2

nd peak temperature was obtained to be 446.8 °C in control groups (dry blending processing). In addition, as the amount of ZnO in nanocomposites increased, the total weight loss decreased. For example, increasing the ZnO loading on WPNCs from 0% to 5% reduced the total weight reduction from 89.1% to 87.2%. The data obtained are similar to earlier studies. Hosseinihashemi et al. [

22] investigated the properties of WPNs reinforced with almond shell flour and montmorillonite. The researchers found that the presence of montmorillonite nanoparticles in the lignocellulose matrix led to an improvement in the nanocomposite's thermal stability. Also, they have said that having nanoparticles in the lignocellulose matrix makes the nanocomposite more stable at high temperatures.

3.4. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

The effects of ZnO nanoparticles and MAPP content on the DMA performance of WPNCs are shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6.

With the increase in ZnO nanoparticle loading, storage and loss modulus values have increased. The control samples (0 wt% ZnO extrusion and 0 wt% ZnO dry blending) without ZnO nanoparticles had the lowest storage modulus with value of 1357 N/mm

2 and 1213 N/mm

2 respectively, while the highest storage with values of 2792 N/mm

2 and 2364 N/mm

2 % was found for the samples containing 5 wt% ZnO with MAPP- extrusion and 5 wt% ZnO with MAPP- dry blending, respectively. A similar trend can be observed for the loss modulus behavior. The highest increase in loss modulus was found in the system filled with 3 wt% MAPP and 5 wt% ZnO nanoparticles. The dynamic mechanical behavior of nanocomposite materials is primarily affected by the elemental characteristics, structural morphology, and the situation of the interface between the nanoparticle and the polymer matrix. This result is in agreement with that published by Faruk and Matuana [

23], where the impact of nanoclay content on some characteristics of wood polymer nanocomposites was investigated. According to the findings of their research, clay-reinforced HDPE/wood composites performed better in terms of storage and loss modulus than clay-free HDPE/wood composites.

With the increase in temperature, the storage and loss modulus of wood polymer nanocomposites were found to decrease because of the increased chain mobility of the wood cell wall polymeric components. Similar observations were reported by Hazarika et al. [

24]. According to their findings, the viscoelastic nature of wood was responsible for the sharp decrease in values at the glass transition temperature (Tg) of wood (50 – 120 °C).

The storage and loss modulus values indicated that the processing technology of WPNCs could be a key factor in the resistance of the materials obtained by extrusion. The storage and loss modulus of WPNCs reinforced with ZnO manufactured by the extrusion technology were determined to be higher than the samples produced by the dry blending method.

The ZnO-reinforced nanocomposites gained a lot more storage and loss modulus when the MAPP was added. In general, the high interfacial interaction in the composite structure positively affects stress transfer. Specimens coupled with MAPP further improved the value of storage and loss modulus. A similar result was observed by Hazarika et al. [

24]. According to their findings, the presence of clay nanoparticles and a coupling agent in the matrix increased the storage and loss of the nanocomposite.

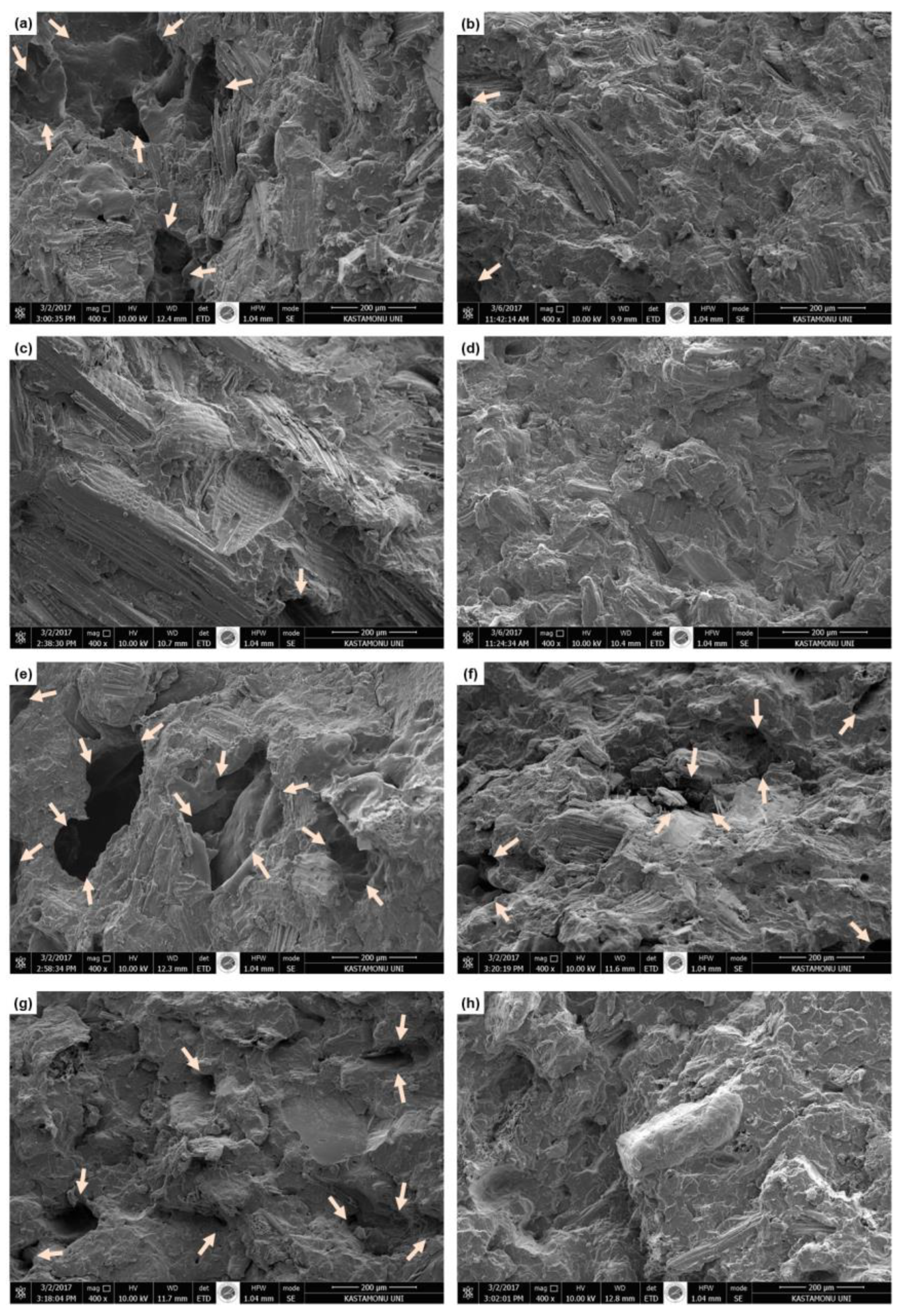

3.5. Morphology of Fracture Surface

Figure 2 shows SEM micrographs of the fracture surface of the manufactured WPNCs. When SEM micrographs of WPNCs are studied, it is clear that the fracture surfaces of those with MAPP added (

Figure 2c - 2d - 2g and 2h) are smoother than those with nano ZnO added (

Figure 2a - 2b - 2e and 2f). Large gaps are highlighted with arrows in SEM micrographs of some WPNCs. According to the studies in the literature, these gaps are created by the incompatibility of wood and plastic [

25,

26,

27]. According to SEM micrographs, the most homogeneous distribution of WPNCs occurs in the E, H, and P groups. These findings appear to be consistent with the mechanical test results obtained from the SEM micrographs.

The dispersion of wood flour into the polymer matrix rises linearly with the rates of nano ZnO and MAPP. When the SEM micrographs of WPNC panels using nano ZnO and MAPP are compared, it can be said that the use of MAPP in WPNC panels homogenizes the distribution more effectively than the use of nano ZnO alone. There was no aggregation found in WPNCs with 3 and 5% nano ZnO added. This demonstrates that the study's findings are consistent with the literature [

28,

29].

On the other hand, when SEM micrographs are examined, it is understood that WPNCs produced by the extrusion method (

Figure 2a – 2b – 2c and 2d) show a more homogeneous distribution than WPNCs produced by the dry blending method (

Figure 2e – 2f – 2g and 2h). Birinci [

30], in his study, said that the voids in the SEM images of the nanocomposites produced by using the dry blending – flat press method are due to the production method.

4. Conclusions

The physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of the WPNCs reinforced with ZnO are significantly dependent on the processing technology, nanomaterial and coupling agent ratios used in the formulations. The TS and WA values of the WPNC groups produced by the extrusion method were lower than those produced by the dry blending method. The processing technology of WPNCs is of great importance to the effectiveness of MAPP and nano ZnO. At the constant content of the ZnO nanoparticles loading (5 wt%) the nanocomposites produced by extrusion method.

The WA and TS values were 2.76% and 1.21% lower than those of the dry blending method, respectively. Similarly, the processing technology, and MAPP and ZnO ratios are significantly important for the mechanical properties of WPNCs.

The mechanical properties of WPNCs improved with increasing amounts of ZnO. The obtained results could be due to the good dispersion of ZnO and MAPP in the wood polymer matrix via the extrusion method. The storage and loss modulus values indicated that the processing technology of WPNCs could be a key factor in the resistance of the materials obtained by extrusion. The storage and loss modulus of WPNCs reinforced with ZnO manufactured by the extrusion technology were determined to be higher than those of the samples produced by the dry blending method. According to TGA results, it has been determined that the presence of ZnO nanoparticles in the lignocellulose matrix resulted in an increased thermal stability of the nanocomposite. Similarly, it was found that the thermal stability of nanocomposites produced by extrusion was higher than that of nanocomposites produced by dry blending.

When SEM micrographs of WPNCs were studied, large voids were seen, particularly in WPNCs that did not utilize MAPP and nano ZnO, and these gaps were largely removed with the inclusion of MAPP and the increase in nano ZnO rates. In addition, according to SEM micrographs, it is understood that WPNCs produced using the extrusion method show a more homogeneous distribution than WPNCs produced by the dry blending method.

Overall, formulations of 3 wt% MAPP and 5 wt% ZnO in wood polymer nanocomposite made by extrusion technology have much better physical, mechanical, and thermal properties than others.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B. and A.K.; methodology, E.B. and A.K.; software, E.B.; validation, E.B. and A.K.; formal analysis, A.K.; investigation, E.B.; resources, E.B. and A.K.; data curation, E.B. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B.; writing—review and editing, E.B. and A.K.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, E.B.; project administration, E.B.; funding acquisition, E.B. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pringle, A.M.; Rudnicki, M.; Pearce, J.M. Wood Furniture Waste–Based Recycled 3-D Printing Filament. For Prod J 2018, 68, 86–95. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kruth, J.-P. Composites by Rapid Prototyping Technology. Mater Des 2010, 31, 850–856. [CrossRef]

- Karami, S.; Khamedi, R.; Azizi, H.; Ahmadi Najafabadi, M. Investigation of the Effect of Nanoparticles on Wood-Bioplastic Composite Behavior Using the Acoustic Emission Method. J Compos Mater 2023, 57, 23–34. [CrossRef]

- Pourghayoumi, M.; Jamali, A.; Behravesh, A.H.; Mazdi, M.; Hedayati, S.K.; Naeini, H.M. Mechanical Properties of Extruded Continuous Glass Fiber Reinforced Wood Particle/HDPE Composites: Effects of Glass Bundle Tex and Arrangement. J Compos Mater 2023, 002199832211510. [CrossRef]

- Klyosov, A.A. Wood-Plastic Composites; John Wiley & Sons, 2007;.

- Arnandha, Y.; Satyarno, I.; Awaludin, A.; Irawati, I.S.; Prasetya, Y.; Prayitno, D.A.; Winata, D.C.; Satrio, M.H.; Amalia, A. Physical and Mechanical Properties of WPC Board from Sengon Sawdust and Recycled HDPE Plastic. Procedia Eng 2017, 171, 695–704. [CrossRef]

- Pickering, K.L.; Efendy, M.G.A.; Le, T.M. A Review of Recent Developments in Natural Fibre Composites and Their Mechanical Performance. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2016, 83, 98–112. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Gu, M.; Guo, Y.; Pan, X.; Mu, G. Effects of Carbon Nanotube Functionalization on the Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Epoxy Composites. Carbon N Y 2009, 47, 1723–1737. [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, A.; Madhoushi, M.; Ashori, A. Wood Plastic Composite Panels: Influence of the Species, Formulation Variables and Blending Process on the Density and Withdrawal Strength of Fasteners. J Polym Environ 2014, 22, 260–266. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.H.; Choi, M.H.; Koo, C.M.; Choi, Y.S.; Chung, I.J. Synthesis and Characterization of Maleated Polyethylene/Clay Nanocomposites. Polymer (Guildf) 2001, 42, 9819–9826. [CrossRef]

- Kord, B.; Hemmasi, A.H.; Ghasemi, I. Properties of PP/Wood Flour/Organomodified Montmorillonite Nanocomposites. Wood Sci Technol 2011, 45, 111–119. [CrossRef]

- Kord, B. Effects of Compatibilizer and Nanolayered Silicate on Physical and Mechanical Properties of PP/Bagasse Composites. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry 2012. [CrossRef]

- Devi, R.R.; Maji, T.K. Chemical Modification of Simul Wood with Styrene–Acrylonitrile Copolymer and Organically Modified Nanoclay. Wood Sci Technol 2012, 46, 299–315. [CrossRef]

- Tabari, H.Z.; Nourbakhsh, A.; Ashori, A. Effects of Nanoclay and Coupling Agent on the Physico-Mechanical, Morphological, and Thermal Properties of Wood Flour/Polypropylene Composites. Polym Eng Sci 2011, 51, 272–277. [CrossRef]

- Asgary, A.R.; Nourbakhsh, A.; Kohantorabi, M. Old Newsprint/Polypropylene Nanocomposites Using Carbon Nanotube: Preparation and Characterization. Compos B Eng 2013, 45, 1414–1419. [CrossRef]

- Kaymakci, A.; Ayrilmis, N.; Gulec, T.; Tufan, M. Preparation and Characterization of High-Performance Wood Polymer Nanocomposites Using Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J Compos Mater 2017, 51, 1187–1195. [CrossRef]

- Kaymakci, A.; Ayrilmis, N. Influence of Repeated Injection Molding Processing on Some Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Wood Plastic Composites. Bioresources 2016, 11. [CrossRef]

- Hemmasi, A.H.; Khademi-Eslam, H.; Talaiepoor, M.; Kord, B.; Ghasemi, I. Effect of Nanoclay on the Mechanical and Morphological Properties of Wood Polymer Nanocomposite. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites 2010, 29, 964–971. [CrossRef]

- Cobut, A.; Sehaqui, H.; Berglund, L.A. Cellulose Nanocomposites by Melt Compounding of TEMPO-Treated Wood Fibers in Thermoplastic Starch Matrix. Bioresources 2014, 9. [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, R.F.; Lepienski, C.M.; Becker, D.; Coelho, L.A.F. Influence of Mixing Methods on the Properties of High Density Polyethylene Nanocomposites with Different Carbon Nanoparticles. Matéria (Rio de Janeiro) 2017, 22. [CrossRef]

- Ladavos, A.; Giannakas, A.E.; Xidas, P.; Giliopoulos, D.J.; Baikousi, M.; Gournis, D.; Karakassides, M.A.; Triantafyllidis, K.S. Preparation and Characterization of Polystyrene Hybrid Composites Reinforced with 2D and 3D Inorganic Fillers. Micro 2021, 1, 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinihashemi, S.K.; Eshghi, A.; Ayrilmis, N.; Khademieslam, H. Thermal Analysis and Morphological Characterization of Thermoplastic Composites Filled with Almond Shell Flour/Montmorillonite. Bioresources 2016, 11. [CrossRef]

- Faruk, O.; Matuana, L. Nanoclay Reinforced HDPE as a Matrix for Wood-Plastic Composites. Compos Sci Technol 2008, 68, 2073–2077. [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, A.; Mandal, M.; Maji, T.K. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis, Biodegradability and Thermal Stability of Wood Polymer Nanocomposites. Compos B Eng 2014, 60, 568–576. [CrossRef]

- Ayrilmis, N.; Akbulut, T.; Dundar, T.; White, R.H.; Mengeloglu, F.; Buyuksari, U.; Candan, Z.; Avci, E. Effect of Boron and Phosphate Compounds on Physical, Mechanical, and Fire Properties of Wood–Polypropylene Composites. Constr Build Mater 2012, 33, 63–69. [CrossRef]

- Kaymakci, A.; Ayrilmis, N.; Gulec, T.; Tufan, M. Preparation and Characterization of High-Performance Wood Polymer Nanocomposites Using Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J Compos Mater 2017, 51, 1187–1195. [CrossRef]

- Karakuş, K.; Aydemir, D.; Öztel, A.; Gunduz, G.; Mengeloglu, F. Nanoboron Nitride-Filled Heat-Treated Wood Polymer Nanocomposites: Comparison of Different Multicriteria Decision-Making Models to Predict Optimum Properties of the Nanocomposites. J Compos Mater 2017, 51, 4205–4218. [CrossRef]

- Ammala, A.; Hill, A.J.; Meakin, P.; Pas, S.J.; Turney, T.W. Degradation Studies of Polyolefins Incorporating Transparent Nanoparticulate Zinc Oxide UV Ztabilizers. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2002, 4, 167–174. [CrossRef]

- Farahan, M.R.M.; Banikarim, F. Effect of Nano Zinc Oxide on Decay Resistance of Wood-Plastic Composites. Bioresources 2013, 8, 5715–5720.

- Birinci, E. Determination of Technological Properties of Wood Plastic Nanocomposites Produced by Flat Press Reinforced with Nano MgO. J Compos Mater 2023, 57, 1641–1651. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).