1. Introduction

Over the last fifty years, a lot of effort has been invested in cancer research to uncover factors that may cause cancer, find more and better treatments and improve cancer patients’ quality of life. One of the difficulties in the treatment of this disease is the large number of biological processes that are involved in both the genesis and the development of tumor growth [

1]. Basic research to unravel all the processes involved in tumor growth and expansion is still very much needed to advance the development of new and better therapeutic applications [

2]. In this regard, it has recently been established that the tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a very important role in both tumorogenesis and metastatogenesis [

3]. Therefore, therapies targeting components of the tumor microenvironment, in addition to cancer cells, could become an excellent anti-cancer treatment. It has been shown that immune cells, such as macrophages, and biological processes, such as angiogenesis and inflammation, are directly responsible for shaping and favoring the development of TME and, with it, tumor spread. For this reason, the tumor microenvironment is increasingly being considered a complex biological target that may enable the development of more novel anticancer therapies [

4].

Endothelial cells within the TME are actively involved in so-called tumor angiogenesis [

5], which allows the creation of a network of blood microvessels to maintain and enable tumor progression [

6]. On the other hand, TME-associated macrophages [

7] may have a central role in tumor propagation as they drive tumor development in both primary and metastatic sites through their contributions in basement membrane degradation and deposition, angiogenesis, leukocyte recruitment and general immune suppression [

8]. In fact, it is clinically demonstrated that anti-angiogenic therapies can modulate and remodel TME resulting in increased efficacy of immunotherapies [

9]. For example, anti-angiogenic treatments can reduce the number of suppressive immune cells and increase the number of immune-stimulating cells in TME, which can enhance the response to immunotherapy [

10]. Additionally, anti-angiogenic treatments can increase the expression of antigens on cancer cells making them more visible to the immune system and easier to target. For this reason, combining immunotherapies with anti-angiogenic treatments has shown promise in improving treatment outcomes in several types of cancer including renal cell carcinoma, lung cancer and colorectal cancer. In some cases, this combination approach has led to longer progression-free survival and overall survival rates than either approach alone. However, more research is needed to fully understand the optimal timing and dosing of these combination therapies and to identify biomarkers that can predict which patients are most likely to benefit from this approach [

11].

In this work, we focus on VEGFR-2 and PD-L1, which are two promising biological targets for the development of new anticancer drugs as they are both key factors in angiogenesis and immune evasion.

VEGFR-2 (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2) is a protein expressed on the surface of endothelial cells that plays a key role in angiogenesis, the process of forming new blood vessels to supply oxygen and nutrients to growing tumors. By inhibiting VEGFR-2 drugs can block angiogenesis and starve tumors from the blood supply they need to grow and metastasize. VEGFR-2 inhibitors, such as bevacizumab and ramucirumab, have shown efficacy in treating multiple cancer types, including colorectal cancer, lung cancer and ovarian cancer. PD-L1 (programmed death-ligand 1) is a protein expressed on the surface of some cancer cells that interacts with PD-1 (programmed cell death protein 1) on T-cells, inhibiting their ability to attack cancer cells. By blocking the interaction between PD-L1 and PD-1 drugs can enhance the immune system's ability to attack cancer cells. PD-L1 inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, have shown efficacy in treating multiple cancer types including lung cancer, melanoma and bladder cancer [

2].

Over the last five years our research has focused on the screening of compounds able to simultaneously block biological targets of special relevance, such as VEGFR-2 and PD-L1 [

12], and to study their effect on the TME [

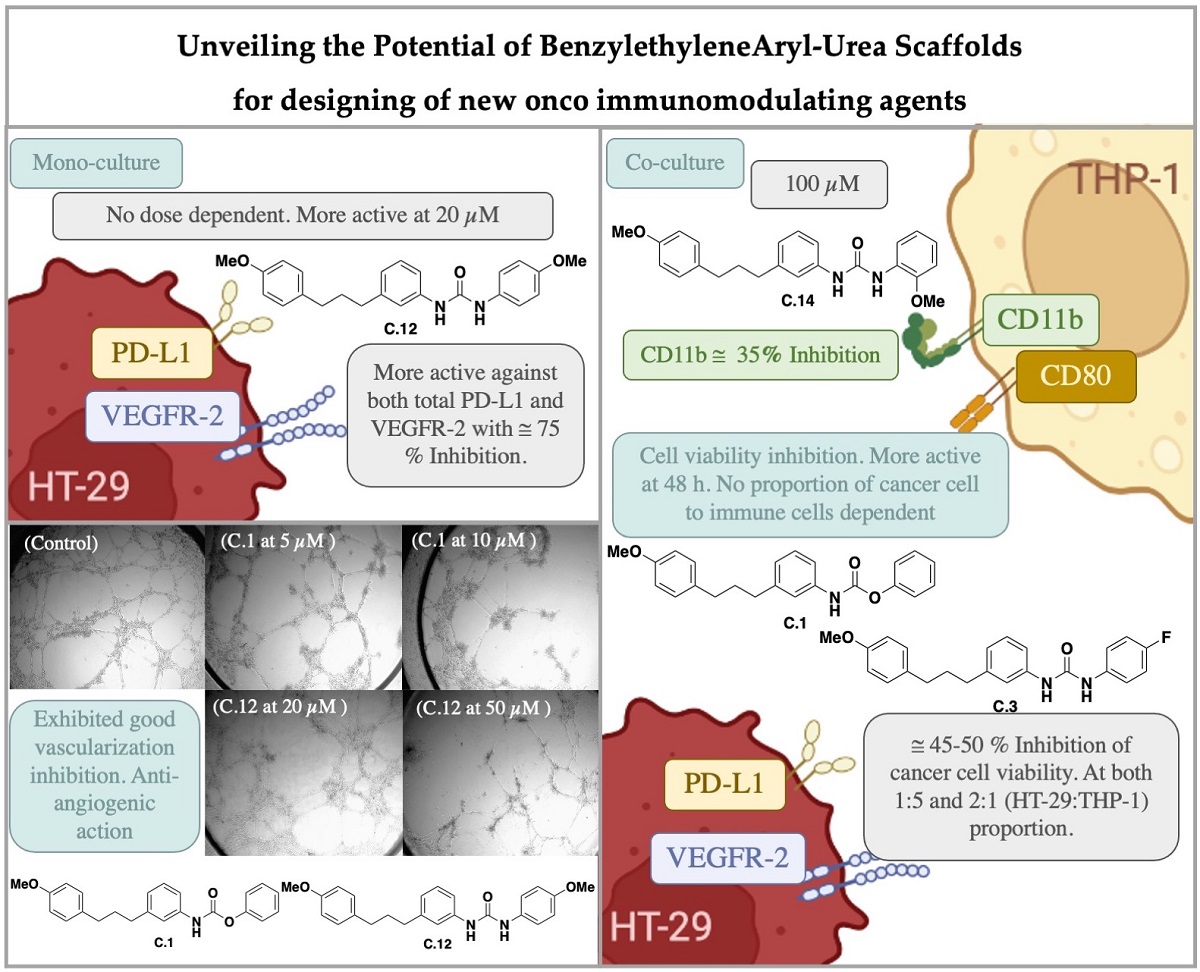

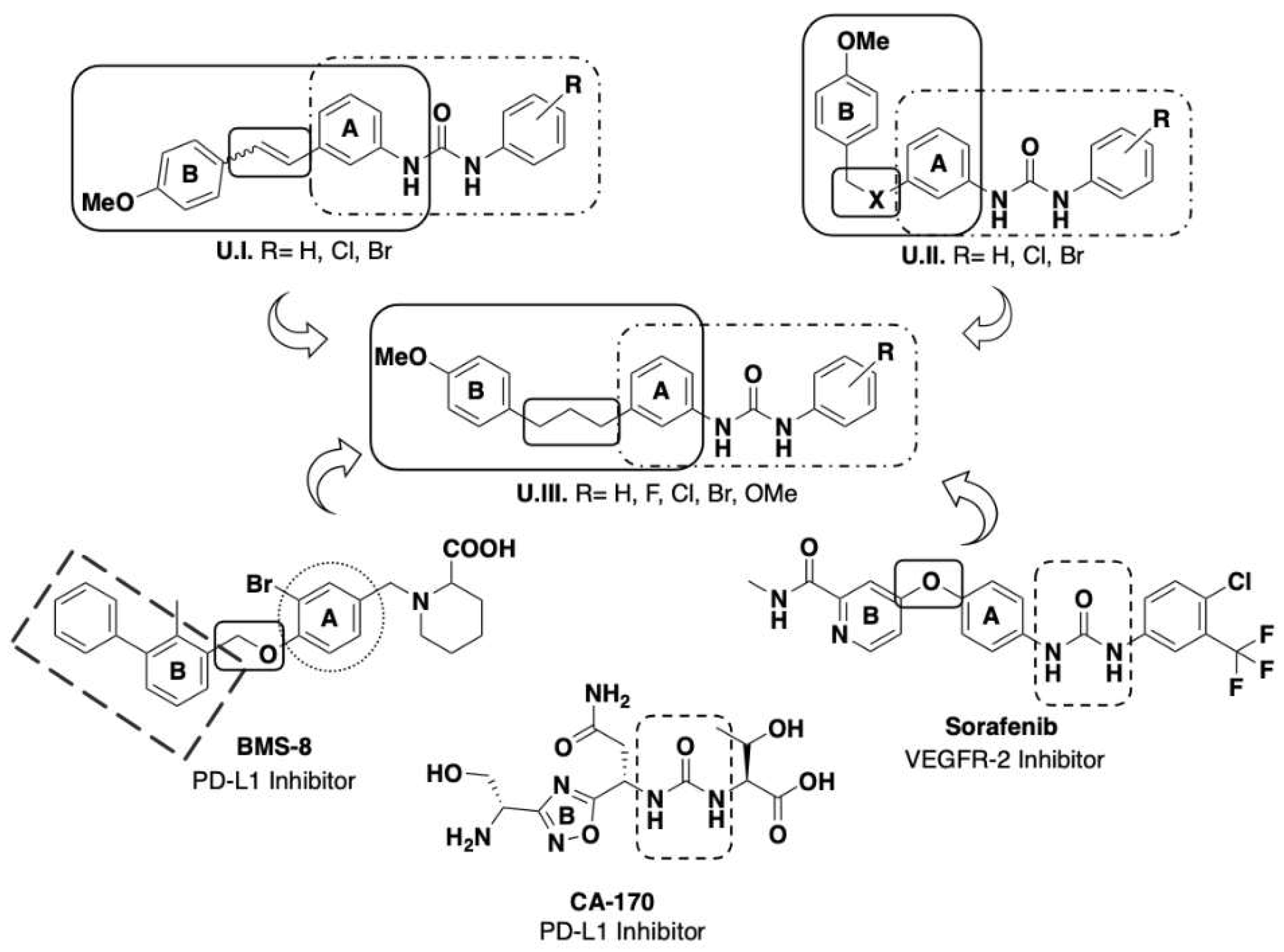

13]. For the designing of the structures we considered the results obtained in our previous studies describing the action of several sets of aryl urea derivatives U.I and U.II bearing a styryl moiety (see

Figure 1). We found that halophenyl urea unit is one of these scaffolds leading to promising small molecule immunomodulator agents due to their multitarget action [

14,

15,

16]. Some small molecules bearing a urea unit had already been described as PD-L1 inhibitors, such as urea CA-170 developed by Aurigene, and as antiangiogenic compounds, such as sorafenib [

17]. In addition, Bristol-Meyers-Squibb has developed PD-L1 inhibitors bearing a biphenyl unit linked to a further aromatic ring through a benzyl ether bond (see as an example BMS-8 structure in

Figure 1) [

17]. With all this information in hand, we decided to develop some new derivatives, generically labelled as U.III in

Figure 1, bearing an aryl urea moiety connected to another aromatic group by a more extensive and flexible chain through the intermediacy of a propenyl functionality. Here we are presenting the synthesis and the biological study of these new U.III derivatives (see

Scheme 1 for specific structures) including their effect on immune cells.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Synthesis of aryl urea derivatives

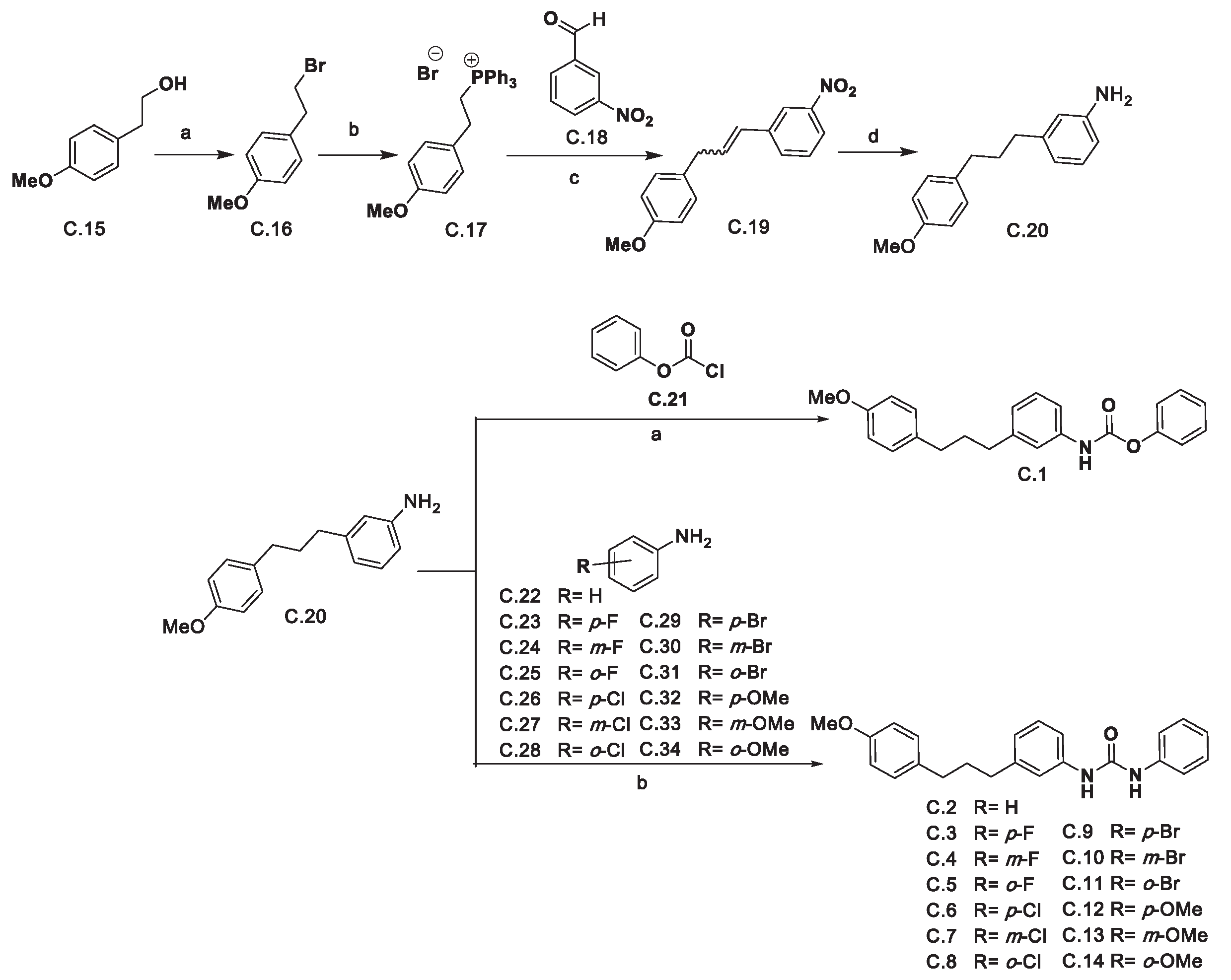

The synthesis of the 1,3-diphenylpropenyl aryl ureas began with the preparation of 3-(3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propyl)aniline

C.20 (see

Scheme 1). Thus, (4-methoxyphenyl)ethan-1-ol

C.15 was converted into 1-(2-bromoethyl)-4-methoxybenzene

C.16 upon reaction with PBr

3.

C.16 treatment with triphenylphosphine afforded the phosphonium salt

C.17 which upon Wittig reaction with 3-nitrobenzaldehyde

C.18 afforded 1-(3-(4-methoxyphenyl)prop-1-en-1-il)-3-nitrobenzene

C.19 as an

E/Z mixture which in turn was converted into aniline

C.20 by hydrogenation.

Aniline C.20 was used to obtain the desired ureas C.2-C.14 and carbamate C.1. As far as the latter is concerned, it was obtained upon the reaction of aniline C.20 with phenyl chloroformate C.21. Finally, the desired ureas were synthesized by reaction of the corresponding anilines C.22-C.34 with triphosgene followed by the addition of compound C.20 to the reaction mixture.

Reagents and conditions: (a) PBr3, toluene, 110 °C, 2 h. (94 %); (b) PPh3, EtOH, 80 °C, 6 days. (83 %); (c) C.18, K2CO3, 18-crown-6, CH2Cl2, 40 °C, 24 h (79 %); (d) H2, Pd/C, AcOEt, r.t., overnight. (78 %); (e) Phenyl chloroformate (C.21), pyridine, THF, 0 °C, 20 min. then r.t. 1 h. (71 %); (f) The appropriate aniline (C.22-C.34), triphosgene, Et3N, THF, r.t. 1 h, then 55 °C 5 h and then aniline C.20, Et3N, THF, 40-50 °C, 24 h. (34- 92 %).

2.2. Biological Evaluation

2.2.1. Cell proliferation inhibition

The ability of the synthesized compounds to affect cell viability was studied by MTT assay using the human tumor cell lines HT-29 (colon adenocarcinoma) and A-549 (pulmonary adenocarcinoma), as well as towards the non-tumor cell line HEK-293 (human embryonic kidney cells), Jurkat T cells and human microvessel endothelial cells (HMEC-1). This assay allowed us to establish the corresponding IC

50 values (expressed as the concentration, in μM at which 50 % of cell viability is achieved) which are shown in

Table 1, in which IC

50 values for the reference compounds sorafenib and BMS-8 are also included.

In terms of the effect on cancer cell lines, in general the synthetic compounds are more active against HT-29 than to A-549 (see

Table 1). We found IC

50 values in the range of micromolar, comparable to that shown by reference compounds sorafenib and BMS-8, except for compounds

C.1 (carbamate),

C.3 (

p-fluorophenyl urea),

C.4 (

m-fluorophenyl urea),

C.12 (

p-methoxyphenyl urea) and

C.14 (

o-methoxyphenyl urea) that have no effect on either HT-29 or A-549, while

C.2 (phenyl urea) and

C.8 (

o-chlorophenyl urea) were also no effective inhibiting A-549 cell proliferation.

Regarding the inhibitory effect on non-cancer cell line HEK-293, the tested compounds behave in a similar way as in HT-29 showing moderate IC50 values except for C.1 (carbamate), C.3 (p-fluorophenyl urea), C.12 (p-methoxyphenyl urea) and C.14 (o-methoxyphenyl urea) that exhibited IC50 values above 100 μM.

Besides, we observed that all the compounds exhibited similar effect on Jurkat T cell than on HMEC-1, that is they were no effective inhibiting proliferation of these cells except for C.7 (m-fluorophenyl urea), C.10 (m-bromophenyl urea), C.11 (o-bromophenyl urea) and C.13 (m-methoxyphenyl urea) with IC50 values around 20 μM.

As in some cases the inhibitory effect on cell proliferation was significantly higher on both cancer cell lines, HT-29 and A-549, than in the others (HEK-293, immune and endothelial cells). Their tumor-selectivity indexes (SI, see

Table 2) were calculated by dividing the IC

50 mean against normal cells by the IC

50 mean against tumor cells. Selectivity indexes below 1 means poor selectivity towards cancer cells in their inhibitory or cytotoxic effect. According to these data, compounds

C.1 (carbamate),

C.3 (

p-fluorophenyl urea),

C.12 (

p-methoxyphenyl urea) and

C.14 (

o-methoxyphenyl urea), with no inhibitory effect towards any cell line were selected for further biological studies.

2.2.2. Effect on cellular PD-L1 and VEGFR-2 in cancer cell lines

In our previous studies, we evaluated the action of some ureas on PD-L1 and VEGFR-2 proteins and we found that these ureas were more active on colorectal cancer cell line HT-29 [

14,

15]. Thus, we decided to assess the effect of our new ureas on these two proteins only on HT-29 cancer cell line by using flow cytometry technique.

Both membrane and total PD-L1 and VEGFR-2 were relatively determined using DMSO treated cells as a negative control and BMS-8 and sorafenib as reference compounds. For these assays, cells were incubated for 24 h in the presence of the corresponding compounds at two different doses, 20 and 100 µM concentrations.

As tested compounds did not show a significant effect on membrane PD-L1 or VEGFR-2,

Table 3 only shows the effect on total PD-L1 and VEGFR-2. It can be seen that no significant effect was achieved for sorafenib at either of the tested doses while BMS-8 inhibited PD-L1 expression in a dose dependent manner, that is 40% at 100 μM and around 15% at 20 μM.

In general, the effect of the selected compounds was not dose dependent. In fact, at 20 μM compounds were more active than at 100 μM. The most active derivative as dual inhibitor was C.12 (p-methoxyphenyl urea) showing inhibition rates at around 75% for both PD-L1 and VEGFR-2. C.14 (o-methoxyphenyl urea) yielded 50% of inhibition of PD-L1 while C.3 (p-fluorophenyl urea) and C.1 (carbamate) inhibited 30% of PD-L1 and about 45 % of VEGFR-2.

Due to the good results obtained for inhibition on both targets, we used the same selected compounds for further studies to determine their potential action as antiangiogenic and immunomodulator agents.

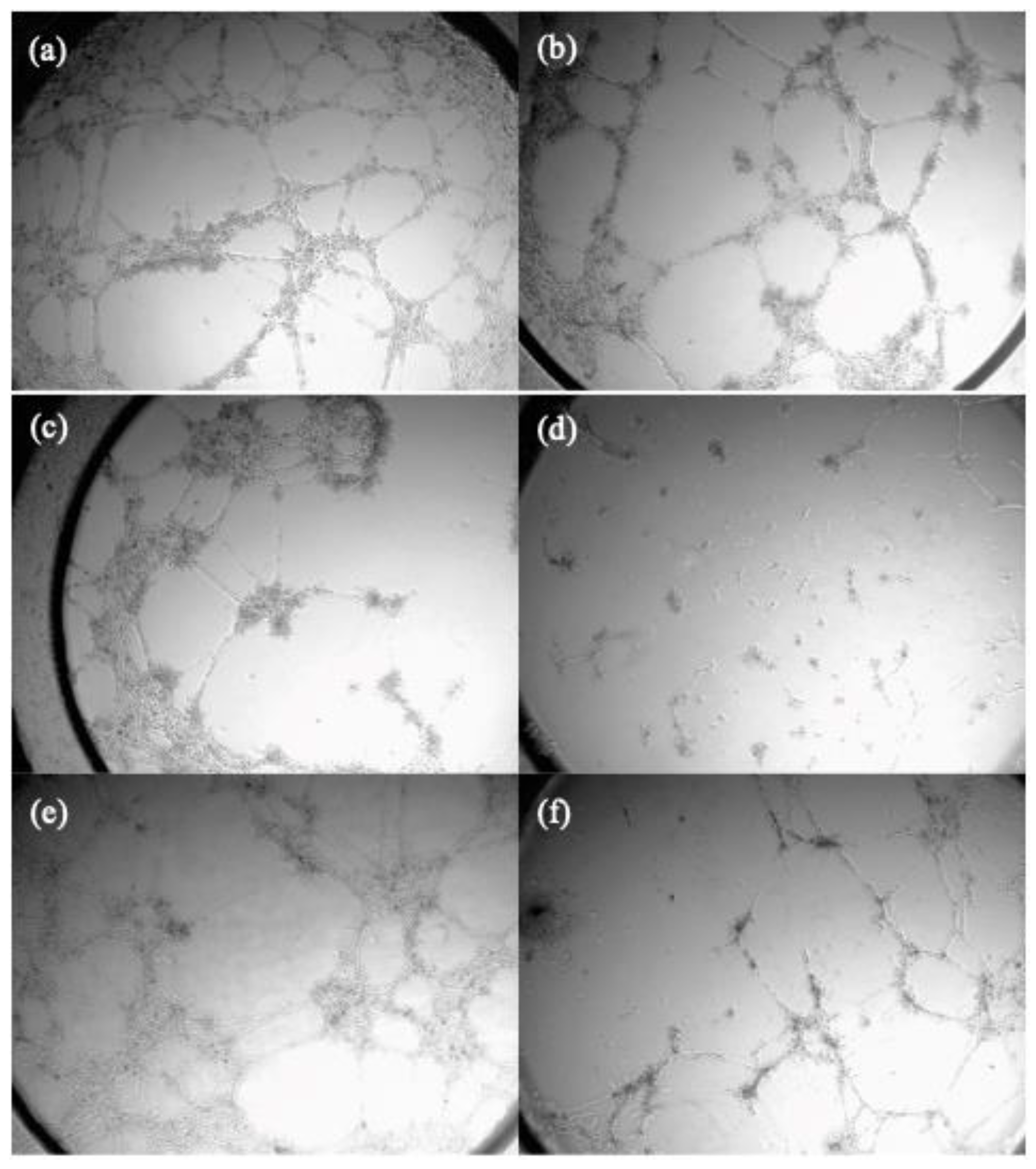

2.2.3. Effect on microtube formation on endothelial cells

To establish the potential of the selected compounds as antiangiogenic agents, the capacity to inhibit the formation of new vasculature network formed by HMEC-1 was evaluated on the reference compounds and selected ones

C.1,

C.3,

C.12 and

C.14.

Table 4 shows the minimum concentration at which these compounds are active and begin to inhibit the microtube formation.

As it can be seen carbamate

C.1 was the most active inhibiting tube formation on HMEC-1, improving sorafenib effect.

C.3 (

p-fluorophenyl urea) and

C.12 (

p-methoxyphenyl urea) have a mild effect whereas

C.14 (

o-methoxyphenyl urea) do not show any effect inhibiting tube formation. These results correlate with the derivates ability to inhibit VEGFR-2 showed in

Table 3.

Figure 2 displays the pictures for the inhibition of neovascularization achieved by compounds

C.1 and

C.12 at different concentrations.

A comparison of the minimum active concentration values to IC

50 values for HMEC-1 cell line (see

Table 1), shows that selected compounds exhibited antiangiogenic action while they have no effect on endothelial cell proliferation.

2.2.4. Effect on cancer cell viability in co-cultures with monocytes THP-1

To establish the potential of the selected compounds as immunomodulator agents, we studied the effect of the selected compounds on tumor cell proliferation in the presence of human monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1. This assay was carried out using HT-29 as the cancer cell line and different proportions of immune cells. Standard proportions for this assay were 1:5 cancer/immune cells. Besides, we also carried out this assay using a 2:1 proportion of cancer cells as regards immune THP-1 cells. Assays were performed after 24 and 48 h of treatment, using 100 μM doses of selected compounds and BMS-8 as the reference compound.

The results in

Table 5 show that the effect on cancer cell viability was higher after 48 hours of treatment and did not depend on the proportion of cancer and immune cells. Compounds

C.1 (carbamate) and

C.3 (

p-fluorophenyl urea) were the most active ones showing 50-45 % of inhibition of cancer cell viability at both (1:5) and (2:1) proportions after 48 h.

C.12 (

p-methoxyphenyl urea) inhibited about 40% of HT-29 cell viability at 48 hours while compound

C.14 (

o-methoxyphenyl urea) was more effective after 48 hours of treatment and with an excess of cancer related to immune cells (43% of inhibition).

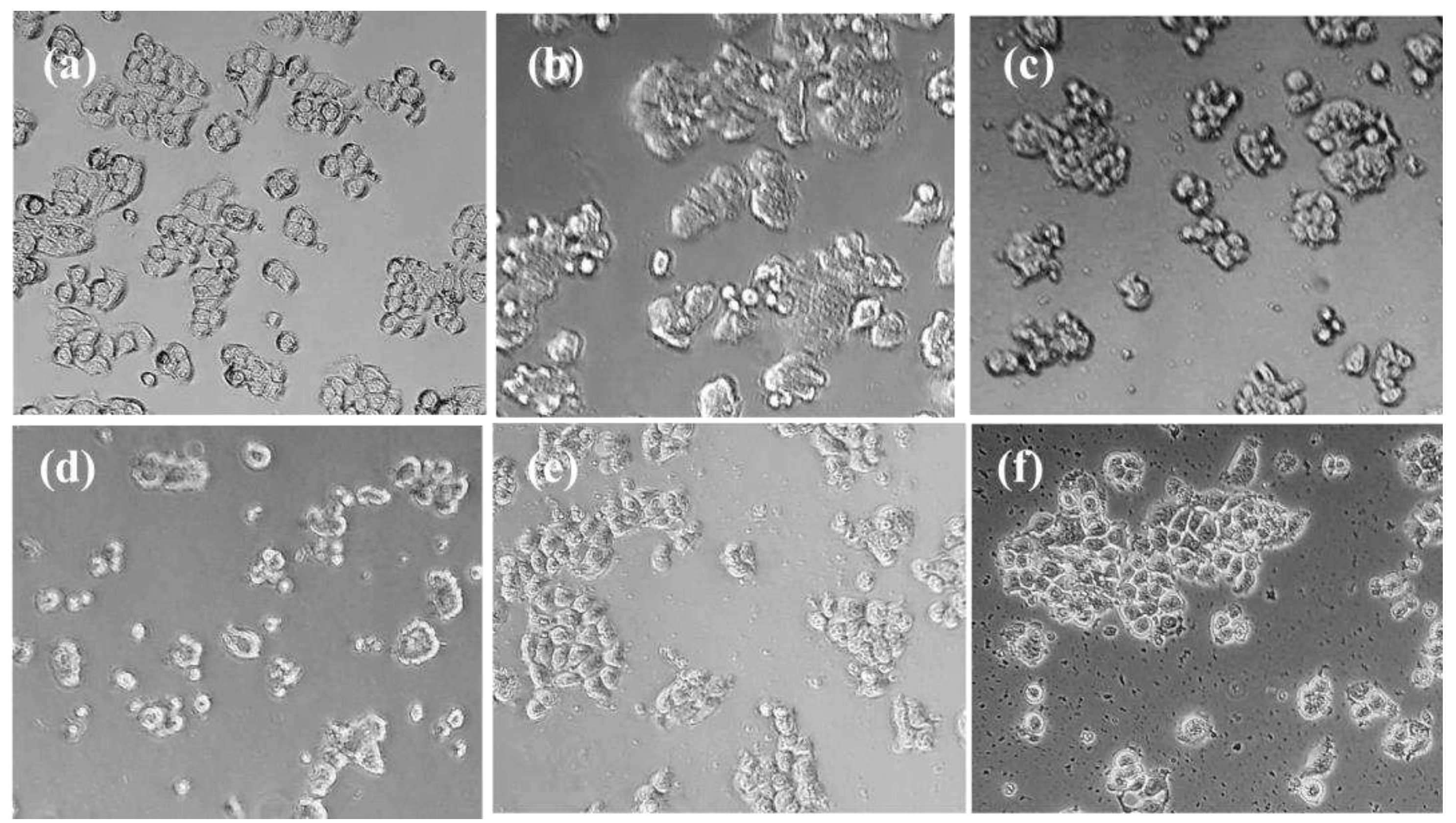

Figure 3 shows the morphological changes suffered by HT-29 cells after 48 hours of co-cultured with THP-1 at (1:5) proportion. We observed that control cells preserved a morphology related to epithelial nature of HT-29 cells while when they were treated with BMS-8 and the selected derivatives cells retained this epithelial nature though increased and brighter cytosolic granulation appeared. Besides, the treatment of HT-29 co-cultures with our compounds lead to a slight loss of cell-to-cell contact and the appearance of clustered cells with rounded shaped-cells and irregular surfaces.

Moreover, treatment with derivatives C.1, C.3, C.12 and C.14 led to less adhesive rounded morphology that resulted in cell scattering with apoptotic features. In addition, derivatives C.1 and C.3 led to less confluent cultures. All of these are morphological changes related to the loss of their epithelial appearance by the synergic action of the compounds and immune cells.

2.2.4. Effect on immune cell viability in co-cultures of HT-29/THP-1

We also determined the effect of the selected compounds on the human monocyte cells THP-1 in the described co-cultures (see

Table 6). In general, none of the compounds had a significant effect on immune cell viability.

It has been demonstrated that cancer, and all the therapies associated with this illness, promote functional alterations in monocytes such as the acquisition of immunosuppressive activity in TME which is related to the expression of CD11b an integrin, that when binds to CD18 promotes the acceleration of the invasiveness and metastasis of cancer cells.[

18]. Reducing the expression of CD11b has become a promising target for immune modulation in anti-cancer therapies. For that reason, we decided to study the effect of our compounds on CD11b in THP-1 cells co-cultured with HT-29. We also determine the relative amount of CD80, a common surface marker for monocytes.

Table 7 shows the most significant results obtained for the expression of CD80 and CD11b proteins on THP-1 membrane. The results are related with non-treated THP-1 cells when they were co-cultured with HT-29.

It can be observed that all the compounds have a mild effect on CD80 expression although a significant effect could be seen on the expression of CD11b. In most of the cases this effect was even higher to the one observed for the reference compound BMS-8. In this sense, C.3 (p-fluorophenyl urea) and C.14 (o-methoxyphenyl urea) reduced about 35% of CD11b, while C.12 (p-methoxyphenyl urea) and carbamate C.1 inhibited around 30% the expression of CD11b.

3. Discussion

We have synthesized thirteen propenylureas and one carbamate to determine their capability as potential multitarget inhibitors of VEGFR-2 and PD-L1 proteins related with the immunosuppressant activity of TME.

In terms of their antiproliferative activity, most of the compounds were found to be selective towards cancer cells as their IC

50 values and, what it is the same, their inhibitory effect on cell proliferation was significantly higher on the tested cancer cell lines HT-29 and A-549 than on the immune and endothelial cells Jurkat T and HMEC-1 cells, respectively. Compared to the effect on non-cancer cells HEK-293, some compounds exhibited selective inhibitory action against cancer cell proliferation at lower doses than the ones against HEK-293, yielding selective indexes above 1 (see

Table 2). Besides, compounds

C.1,

C.3,

C.12 and

C.14 exhibited no antiproliferative action in either of the tested cell lines.

From the observations provided, it can be concluded that there is a relationship between the structure of the synthetic compounds and their antiproliferative activity. Thus, carbamate and fluoro and methoxy phenyl ureas were the less toxic compounds, while for the rest of ureas p-aryl substituted ones were more active in the inhibition of cancer cell proliferation than m-substituted ones and these showed more active than the o-substituted ureas.

Compounds with no inhibitory effect on any cell line (C.1, C.3, C.12 and C.14) were chosen for further biological studies in order to determine their potential as onco-immunomodulatory agents.

From these studies we found that some of the selected compounds exhibited significant inhibitory effects on both total PD-L1 and VEGFR-2 in HT-29 cell line. As regards the effect on VEGFR-2, we found that p-sustituted ureas C.3 and C.12 were the most active ones yielding around 70% of inhibition rates. Besides, in terms of PD-L1 inhibition we found that methoxyphenyl ureas C.12 and C.14 were the most active ones showing more than 55% of protein expression inhibition. Moreover, almost all the tested derivatives exhibited good antiangiogenic properties as they all inhibited the formation of new microvessels on matrigel HMEC-1 cell cultures.

The selected compounds were also tested for their effect on cancer cell proliferation and immune cell viability in co-culture experiments using HT-29 and THP-1 cells. From this study we established that the effect of the tested compounds on cancer cell viability in the presence of THP-1 was more prominent after 48 hours of treatment, though at 24 hours important morphological changes had been already produced not being affected by the proportion of cancer and immune cells. Besides, the effect of the compounds was no-dose dependent. Compounds C.1 and C.3 were the most active ones in inhibiting cancer cell viability, while C.12 and C.14 also showed significant inhibition. On the other hand, none of the tested compounds had any effect on the immune cell viability. Furthermore, the compounds were tested for their effect on CD11b and CD80 expression in THP-1 cells co-cultured with HT-29. While the effect on CD80 expression was very mild (less than 10 % of inhibition rates) all the compounds tested were found to significantly reduce CD11b expression, which is a promising target for immunemodulation in anti-cancer therapies.

Overall, this study provides valuable insights into the potential of the tested compounds as immunemodulators in anti-cancer therapies, especially in reducing CD11b expression. Further studies are needed to determine their efficacy and safety in preclinical settings.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. General procedures

1H and 13C NMR spectra were measured at 25 °C. The signals of the deuterated solvent (CDCl3, DMSOd6 ) were taken as the reference. Multiplicity assignments of 13C signals were made by means of the DEPT pulse sequence. Complete signal assignments in 1H and 13C NMR spectra were made with the aid of 2D homo- and heteronuclear pulse sequences (COSY, HSQC, HMBC). High resolution mass spectra were recorded using electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry (ESI–MS). IR data were measured with oily films on NaCl plates (oils) and are given only for relevant functional groups (C=O, NH). Experiments which required an inert atmosphere were carried out under dry N2 in flame-dried glassware. Commercially available reagents were used as received.

3.1.2. Experimental procedure for the synthesis of ureas C.2-C.14

A solution of the corresponding aniline (1.0 mmol) dissolved in dry THF (5.0 mL) was slowly dripped into a stirred solution of triphosgene (303 mg, 1.0 mmol) in dry THF (5.0 mL). Then, Et3N (279 µL, 2.0 mmol) was slowly added to the reaction mixture and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and then refluxed for 5 h under nitrogen atmosphere. After this time, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and the solid was filtered-off. After evaporation of the solvent in vacuo, the residue was taken up in dry THF (5.0 mL) and a THF solution (5.0 mL) of 3-(3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propyl)aniline (C.20) (241 mg, 1.0 mmol) was directly added followed by Et3N (139 µL, 1.0 mmol) addition. The resulting mixture was refluxed under nitrogen atmosphere overnight. Then, solvent was removed in vacuo and AcOEt (20 mL) was added. The organic phase was washed with aqueous HCl 10 % (2 x 20 mL) and brine and dried over Na2SO4. Then, the solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was recrystallized from acetonitrile and dried under vacuum to give ureas C.2-C.14 as white solids (34-92 %).

3.2. Biological studies

3.2.1. Cell culture

Cell culture media were purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, NY). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Harlan-Seralab (Belton, U.K.). Supplements and other chemicals not listed in this section were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Plastics for cell culture were supplied by Thermo Scientific BioLite. For tube formation assay an IBIDI μ-slide angiogenesis (IBIDI, Martinsried, Germany) was used. All tested compounds were dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 10 mM and stored at −20 °C until use.

HT-29, A549, HEK-293 and Jurkat cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing glucose (1 g/L), glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (50 μg/mL), streptomycin (50 μg/mL), and amphotericin B (1.25 μg/mL), supplemented with 10 % FBS. HMEC-1 cell line was maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/Low glucose containing glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (50 μg/mL), streptomycin (50 μg/mL), and amphotericin B (1.25 μg/mL), supplemented with 10 % FBS. For the development of tube formation assays in Matrigel, HMEC-1 cells were cultured in EGM-2MV Medium supplemented with EGM-2MV SingleQuots.

3.2.2. Cell proliferation assay

In 96-well plates, 5 x 103 (HT-29, A549, HMEC-1, Jurkat and HEK-293) cells per well were incubated with serial dilutions of the tested compounds in a total volume of 100 μL of their respective growth media. The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; Sigma Chemical Co.) dye reduction assay in 96-well microplates was used. After 2 days of incubation (37 °C, 5 % CO2 in a humid atmosphere), 10 μL of MTT (5 mg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline, PBS) was added to each well and the plate was incubated for a further 3 h (37 °C). After that, the supernatant was discarded and replaced by 100 µL of DMSO to dissolve formazan crystals. The absorbance was then read at 550 nm by spectrophotometry. For all concentrations of any compound, cell viability was expressed as the percentage of the ratio between the mean absorbance of treated cells and the mean absorbance of untreated cells. Three independent experiments were performed and the IC50 values (i.e., concentration half inhibiting cell proliferation) were graphically determined using GraphPad Prism 4 software.

3.2.3. PD-L1 and VEGFR-2 Relative Quantification by Flow Cytometry

To study the effect of the compounds on every biological target in cancer cell lines compounds were used at 20 and 100 µM dose.

For the assay, 105 cells per well were incubated for 24 h with the corresponding dose of the tested compound in a total volume of 500 μL of their growth media.

To detect total PD-L1 and VEGFR-2, after the cell treatments they were collected and fixed with 4% in PBS paraformaldehyde. After fixation a treatment with 0,5% in PBS TritonTM X-100 was performed and finally cells were stained with FITC Mouse monoclonal Anti-Human VEGFR-2 (ab184903) and Alexa Fluor® 647 Rabbit monoclonal Anti-PD-L1 (ab215251).

To detect membrane PD-L1 and VEGFR-2 the process was the same avoiding the treatment with 0,5 % in PBS TritonTM X-100 step.

3.2.4. Tube formation inhibition assay

Wells of an IBIDI μ-slide angiogenesis (IBIDI, Martinsried, Germany) were coated with 15 μL of Matrigel® (10 mg/mL, BD Biosciences) at 4 °C. After gelatinization at 37 °C for 30 min, HMEC-1 cells were seeded at 2 x 104 cells/well in 25 μL of culture medium on top of the Matrigel and were incubated 30 min at 37 °C while are attached. Then, compounds were added dissolved in 25 μL of culture medium and after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, tube formation was evaluated.

3.2.5. Cell viability evaluation in co-cultures.

To study the effect of the compounds on the cell viability in co-culture with THP-1 cells, 105 or 2 x 105 of the HT-29 cells line per well were seeded and incubated for 24 h. Then medium was changed by a cell culture medium supplemented with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml; human, Invitrogen®) containing 5 x 105 or 105 respectively of THP-1 cells per well and the corresponding compound at 100 μM or DMSO for the positive control. After 24 h/ 48 h of incubation, supernatants were collected to determine THP-1 living cells. Beside, stain cancer cells were collected with trypsin. Both types of suspension cells were fixed with 4 % in PBS paraformaldehyde and counted by flow cytometry.

3.2.6. CD11b and CD80 relative quantification by Flow Cytometry in co-cultures.

To study the effect of the compounds on every biological target in co-cultured THP-1 immune cell with cancer cell line HT-29, compounds were incubated for 24 h/ 48 h as described before.

To detect membrane CD11b and CD80, after the cell incubation, THP-1 were collected, fixed with 4 % in PBS paraformaldehyde and stained with FITC Mouse monoclonal Anti-Human CD80 (sigma-aldrich SAB4700142) and Alexa Fluor® 647 Rabbit monoclonal Anti-CD11b (Merck #MABF366).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.F. and M.C.; Synthetic methodology, M.C., S.R.; Biological assays: R.G-E. and E.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was been funded by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (projects RTI2018-097345-B-I00 and PID2021-1267770B-100) and by the Universitat Jaume I (project UJI-B2021-46).

Acknowledgments

R.G.-E. thanks the Asociación Española Contra el Cancer (AECC) for a predoctoral fellowship (PRDCA18002CARD). The authors are also grateful to the SCIC of the Universitat Jaume I for providing NMR, Mass Spectrometry and Flow Cytometry facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Whiteside, T. L. The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene. 2008, 27, 5904–5912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M-Z. ; Jin, W-L. The updated landscape of tumor microenvironment and drug repurposing. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020, 5, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Mendes, R.; Baptista, P. V.; Fernandes, A. R. Targeting Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghban, R.; Roshangar, L.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, R. , et al. Tumor microenvironment complexity and therapeutic implications at a glance. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergers, G.; Benjamin, L. E. Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitohy, B.; Nagy, J. A.; Dvorak, H. F. Anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapy for cancer: Reassessing the target. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 1909–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, F. O.; Gordon, S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasiya, S.; Poltavets, L.; Polina, A.; Vishnyakova, A.; Gennady, T.; Sukhikh, L.; Fatkhudinov, T. Macrophage Modification Strategies for Efficient Cell Therapy. Cells. 2020, 9, 1535–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.J. , Bokov, D., Markov, A. et al. Cancer combination therapies by angiogenesis inhibitors; a comprehensive review. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A. , Allavena, P., Marchesi, F. et al. Macrophages as tools and targets in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 799–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonasch, E.; Atkins, M.B.; Chowdhury, S.; Mainwaring, P. Combination of Anti-Angiogenics and Checkpoint Inhibitors for Renal Cell Carcinoma: Is the Whole Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts? Cancers. 2022, 14, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pla-López, A.; Castillo, R.; Cejudo-Marín, R.; García-Pedrero, O.; Bakir-Laso, M.; Falomir, E.; Carda, M. Synthesis and Bio-logical Evaluation of Small Molecules as Potential Anticancer Multitarget Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Edo, R.; Espejo, S.; Falomir, E.; Carda, M. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Potential Oncoimmunomodulator Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Beltrán, C.; Gil-Edo, R.; Hernández-Ribelles, G.; Agut, R.; Marí-Mezquita, P.; Carda, M. and Falomir, E. Aryl Urea Based Scaffolds for Multitarget Drug Discovery in Anticancer Immunotherapies. Pharmaceuticals. 2021, 14, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conesa-Milián, L.; Falomir, E.; Murga, J.; Carda, M.; Marco, J.A. Novel multitarget inhibitors with antiangiogenic and immunomodulator properties. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 148, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conesa-Milián, L.; Falomir, E.; Murga, J.; Carda, M.; Marco, J.A. Synthesis and biological evaluation as antiangiogenic agents of ureas derived from 3′-aminocombretastatin A-4. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 162, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, R.; Fetterly, G.; Lugade, A.; Thanavala, Y. Sorafenib: a clinical and pharmacologic review. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2010, 11, 1943–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, N.; Choi, S.H. Tumor-associated macrophages in cancer: recent advancements in cancer nanoimmunotherapies. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).