1. Introduction

It is well-established that nanoparticles with sizes ranging between 1 and 100 nm, exhibit different and appealing characteristics compared with their micro and macro counterparts. In recent years, magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) have been used in areas of nanotechnology, in particular for biomedical applications [

1,

2] where precise delivery of anticancer drugs and selective killing of cancer cells is desirable. Magnetic hyperthermia treatment [

3] is based on the use of nanoparticles dispersed in a magnetic fluid. When MNPs are under the presence of an external AMF, they are able to heat a specific area of the body causing cells death in tumor tissue [

6]. During such process, two relaxation mechanisms for MNPs are known, namely, the Néel [

4] and Brown [

5] modes. In the former, magnetic moments rotate inside the nanoparticle due to the action of the external AMF. In contrast, in Brown relaxation, magnetic moments are locked to the magnetic easy-axis of the MNP and the AMF causes a mechanical rotation of the particle as a whole. The heat released to the medium is either caused by the friction between the surface of MNPs and the surrounding magnetic-fluid, or by the power dissipated through the hysteresis losses [

7]. The heating efficiency of a MNP under an external AMF is expressed in the physical quantity called specific loss power (SLP) [

8,

9].

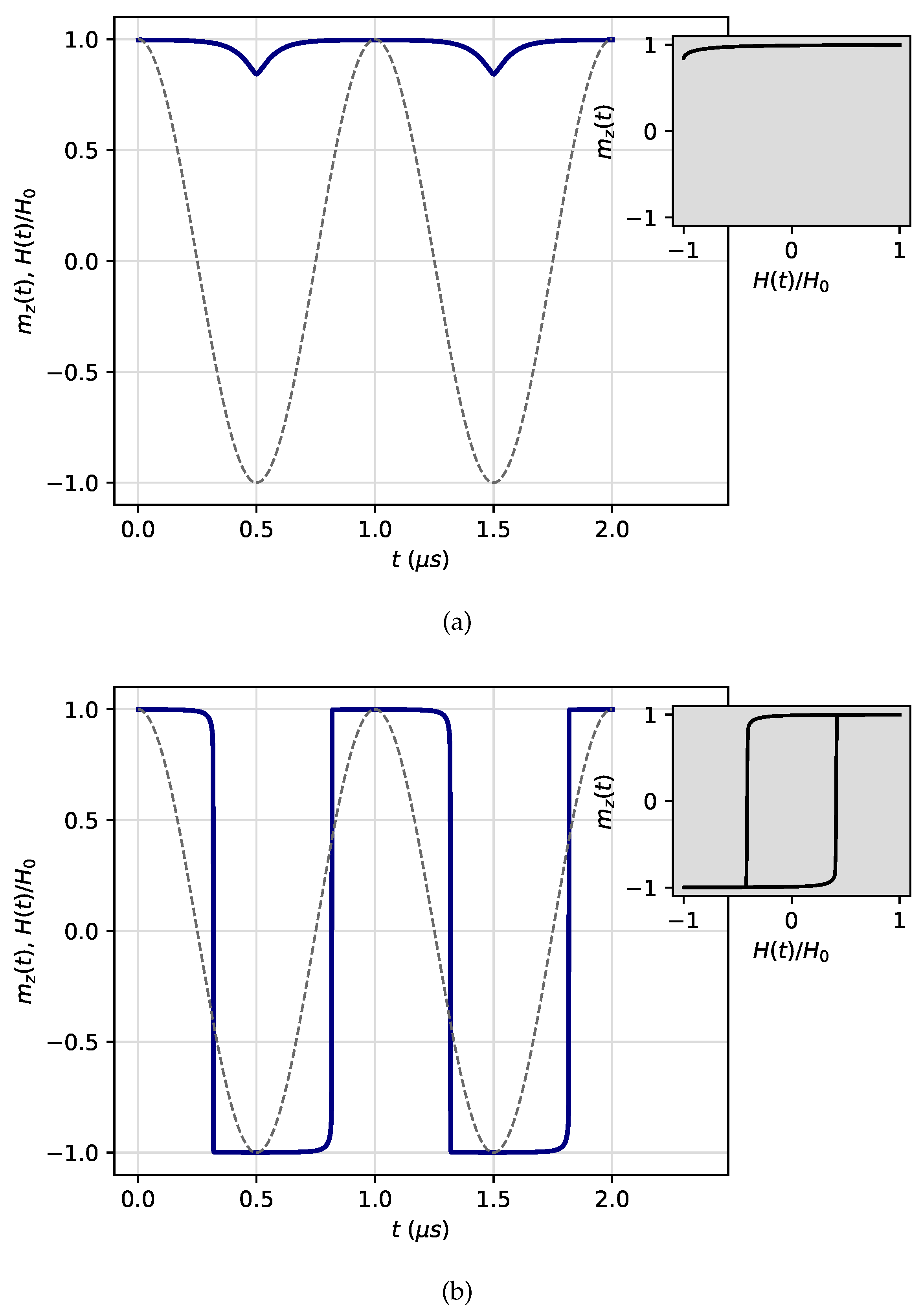

The dynamic response of a MNP in an external time-dependent magnetic field of amplitude

and period

P, is not instantaneous and it exhibits a delay in time. Time delay of the magnetization gives rise to the appearance of two possible regimes [

10,

11,

12]: a dynamically ordered phase (DOP) and a dynamically disordered one (DDP), which depend on the relationship between

P,

and the metastable lifetime

[

13,

14]. In the DOP (see

Figure 1a), magnetization is not able to follow the magnetic field, giving rise to a high value of the average magnetization. In DDP (see

Figure 1b), magnetization follows the magnetic field even though with a

dependent delay, and it gets to be reversed resulting in a well-defined hysteresis loop. In this case, the metastable lifetime, which is the elapsed time to go from the saturation state and pass through zero magnetization, can be computed.

The universal aspects that allow a dynamic phase transition have been studied in some works [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. B. K. Chakrabarti and M. Acharyya [

12] showed that magnetic response in time by an external field depends on the competing time scales, i.e. the time period of oscillation of the external perturbation and the typical relaxation time. When the time period of oscillation is comparable with the effective relaxation time, symmetric hysteresis loops around the origin are obtained. A breaking of the symmetry of the hysteresis appears when the driving frequency of the field increases. This phase transition depends on the field amplitude and temperature. On the other hand, G. Korniss et. al. [

11] studied through Monte Carlo simulations the two-dimensional kinetic Ising model with a square-wave oscillating external field of period

P. Their results showed that the system undergoes a dynamic phase transition when the half-period

of the field is comparable to the metastable lifetime

, which in turn depends on temperature

T and the field amplitude

. Several metastable states were also studied by P. A. Rikvold et. al. [

14] for an impurity-free kinetic Ising model with nearest neighbor interactions and local dynamics under a magnetic field, in the framework of droplet theory and Monte Carlo simulation. They demonstrated that metastable lifetimes exhibited magnetic field and system-size dependences. Additionally, W. D. Baez and T. Datta [

13], established for a two-dimensional ferromagnetic kinetic Ising model with oscillating field and next-nearest neighbor interactions, that metastable lifetimes are determined by the lattice size, amplitude and frequency of the external field, temperature and additional interactions present in the system.

Micromagnetic models [

15], based on the solution of the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert equation [

16,

17,

18], have also allowed a theoretical description of micro and nanoscale magnetization processes above the exchange length. Micromagnetism integrates classical and quantum mechanical effects, where the spin operators of the Heisenberg model are replaced by classical vectors and also accounts for exchange interaction. The main assumptions of the model are: the distribution of the magnetic moments is considered discrete throughout the volume of the magnetic system by means a set of discretization cells and at the same time it is approximated by a density vector

, which is continuous and differentiable with respect to both space

and time

t, and it can be written in terms of a unit vector field

where

is the saturation value of constant norm.

Despite all the studies devoted to systems exhibiting dynamic phase transitions, little effort has been paid to the role played by the spatial orientation of the easy-axis of a single nanoparticle relative to the direction and sense of the external applied oscillatory field. It must be stressed that different orientations of the magnetic easy-axis must be interpreted as different ensamble microstates occurring during Brown rotation, so by fixing the magnetic easy-axis in each microstate considered, we can drive our attention to the Néel relaxation at each Brown rotation step. Thus, the purpose of the present work is to calculate the metastable lifetimes for different amplitudes

and orientations of the magnetic easy-axis

as well as the interplay between these two parameters. To do so, micromagnetic simulations were performed using the Ubermag [

19] package based on the Object Oriented Micromagnetic Framework (OOMF) [

20].

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2 we present an overview of the micromagnetic background of a MNP with a given easy-axis of magnetization, its geometrical and physical aspects and computational details. Numerical results are presented in

Section 3 where a proposal of dynamic phase diagram is presented, and in

Section 4 we make a summary and a brief conclusion of the main results.

3. Results and Discussion

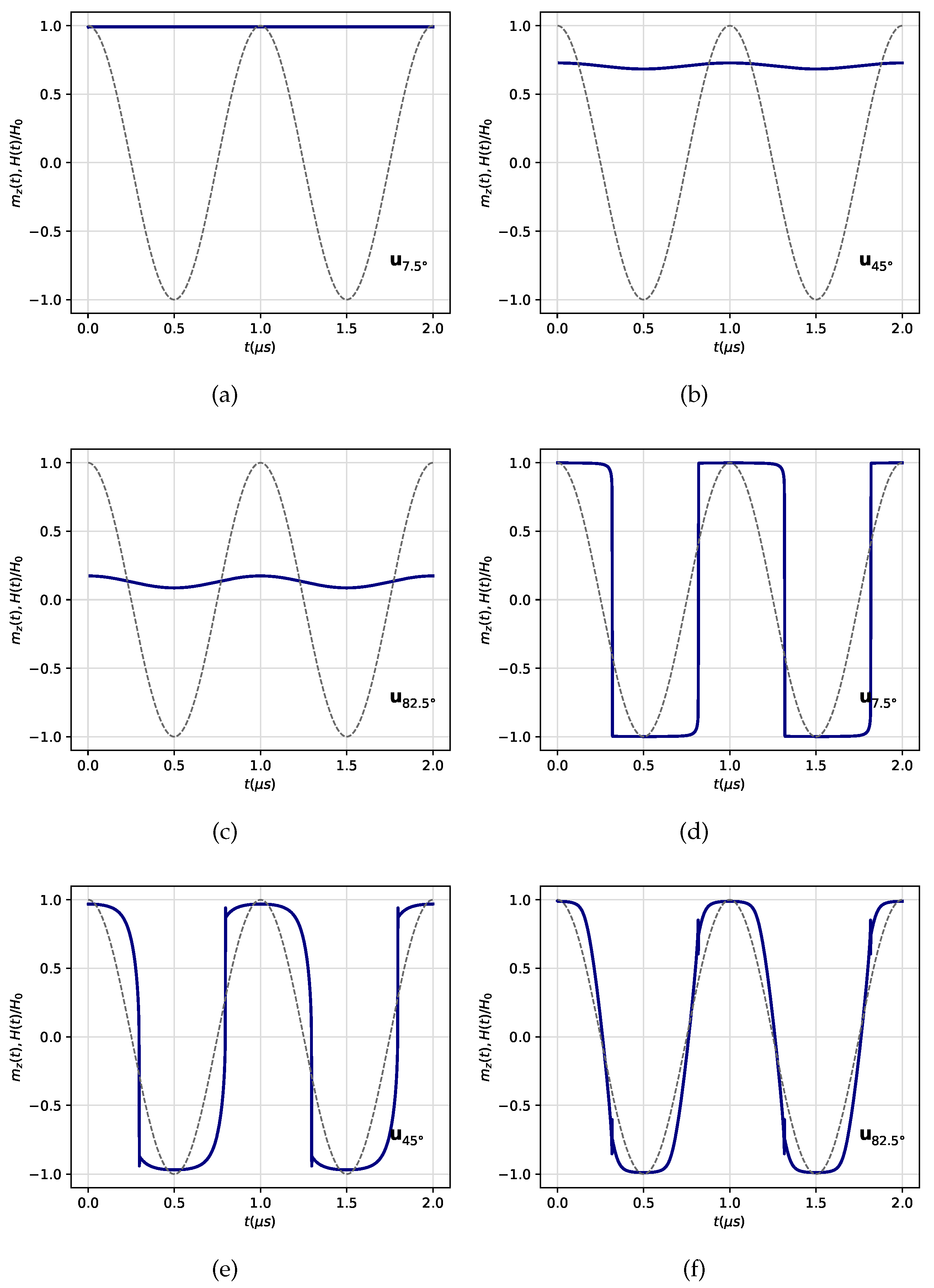

The magnetization in the micromagnetic model is calculated by solving the LLG equation at zero temperature. First, we calculate the

component of magnetization for amplitudes of

mT and

mT, as is shown in

Figure 4a–c and

Figure 4c–e respectively. Simulations were performed for

,

and

. First, note that for an amplitude of the external AMF of

mT, and for each orientation of the easy-axis, the system is found in a DOP. In contrast, a DDP is evidenced for

mT. Hence, the results shown in

Figure 4 demonstrate that both DOP and DDP depend on the

of AMF and the easy-axis orientation. A sharp reversal of magnetization takes place for

values small, i.e.

.

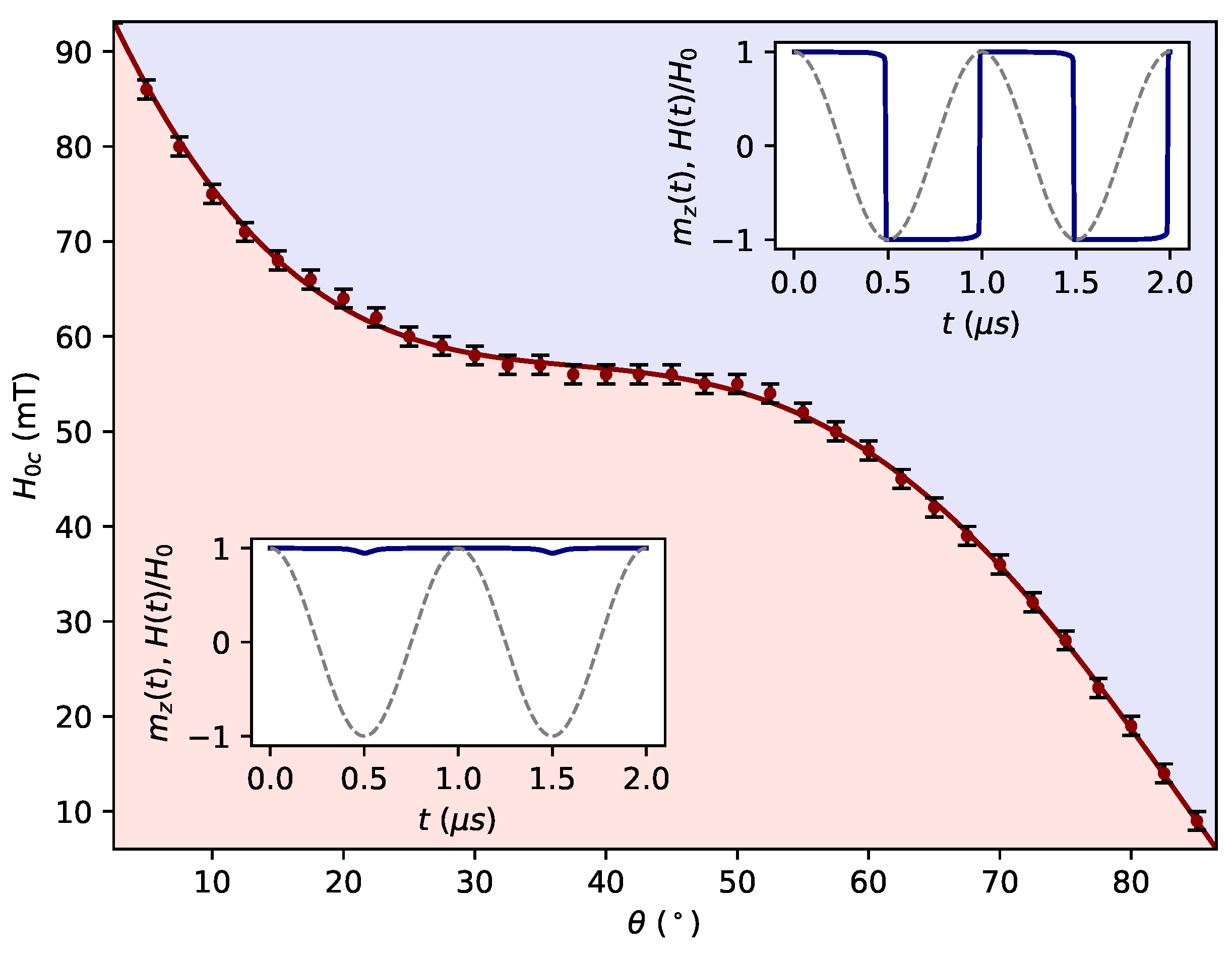

Now that it is known the dependence of DOP and DDP with the amplitude of the external AMF, we can calculate the critical amplitudes

for which the DPT of the type DOP-DDP occurs for a wide range of values of the polar angle

as shown in

Figure 5. To achieve this dynamic magnetic phase diagram, it was necessary to carry out systematically several simulations like those shown in

Figure 4, in order to determine the critical amplitudes

of the AMF for which the magnetization was not able to be switched. As can be observed in this figure, the lower region corresponds to the DOP whereas the upper region indicates the DDP. Thus, the DPT is strongly dependent on both the amplitude and the easy-axis orientation of the particle, and both quantities follow a non-linear relationship. Moreover, as the easy-axis is oriented nearly-parallel to the magnetic field direction, DPT takes place at higher values of amplitude. In contrast, for an orientation nearly-perpendicular of

DPT occurs at lower amplitude values. Thus, a nearly perpendicular orientation of

makes the magnetic system less rigid, giving rise to a DPT at small magnetic fields. This fact constitutes a way of tuning the magnetically hard or soft character of the system.

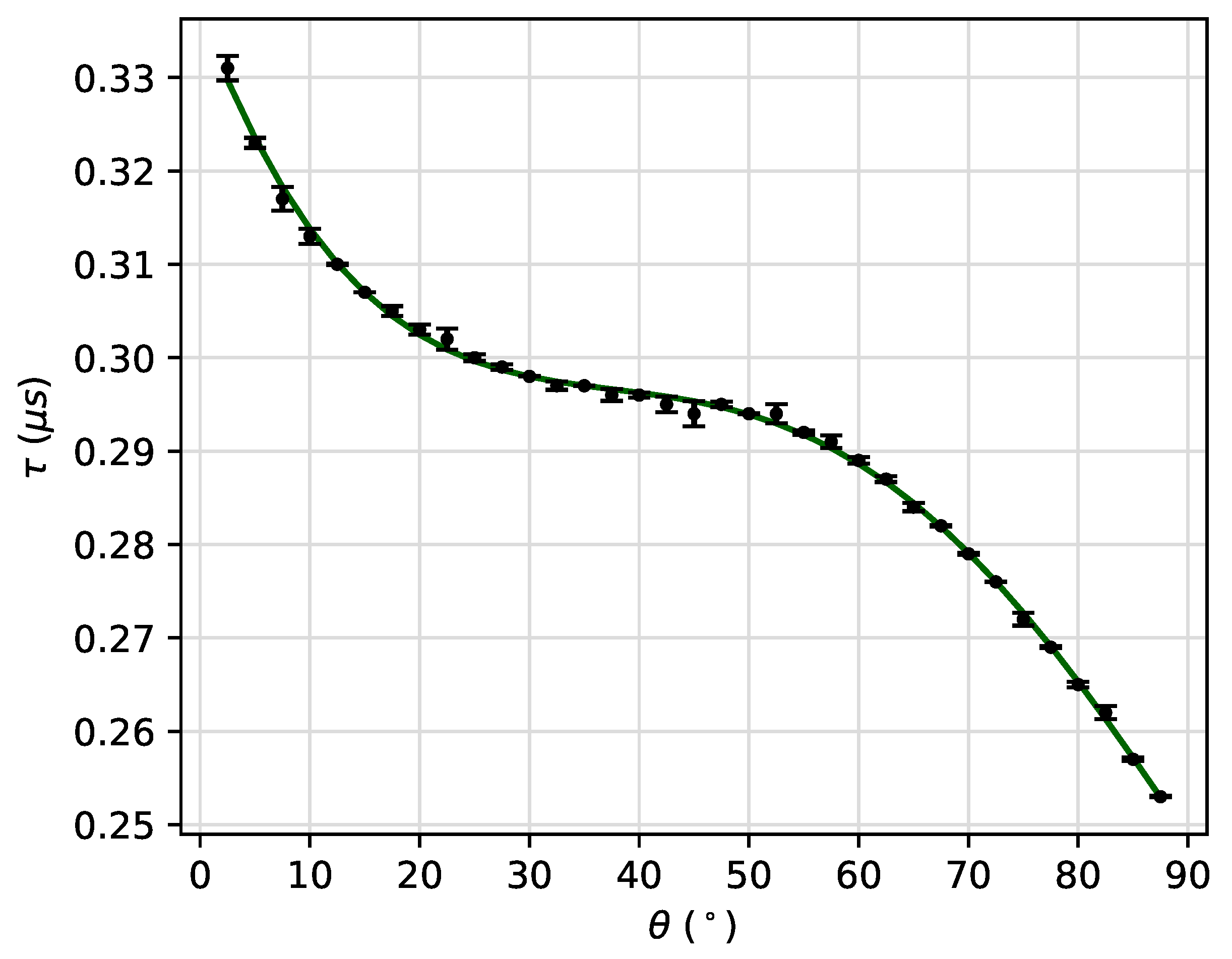

As larger amplitudes of the external AMF are considered, the magnetization quickly escapes from its metastable state and

slowly decreases as

is oriented nearly-perpendicular to the external AMF direction. In contrast, the small the amplitude, more time is required to escape from the metastable state, and

quickly decreases with the increase of

. Thus, we conclude that the metastable lifetime

not only depends on the amplitude of the external AMF at a given frequency, but also on the easy-axis orientation. Several numerical results for different orientations of

were obtained as is shown in

Figure 6.

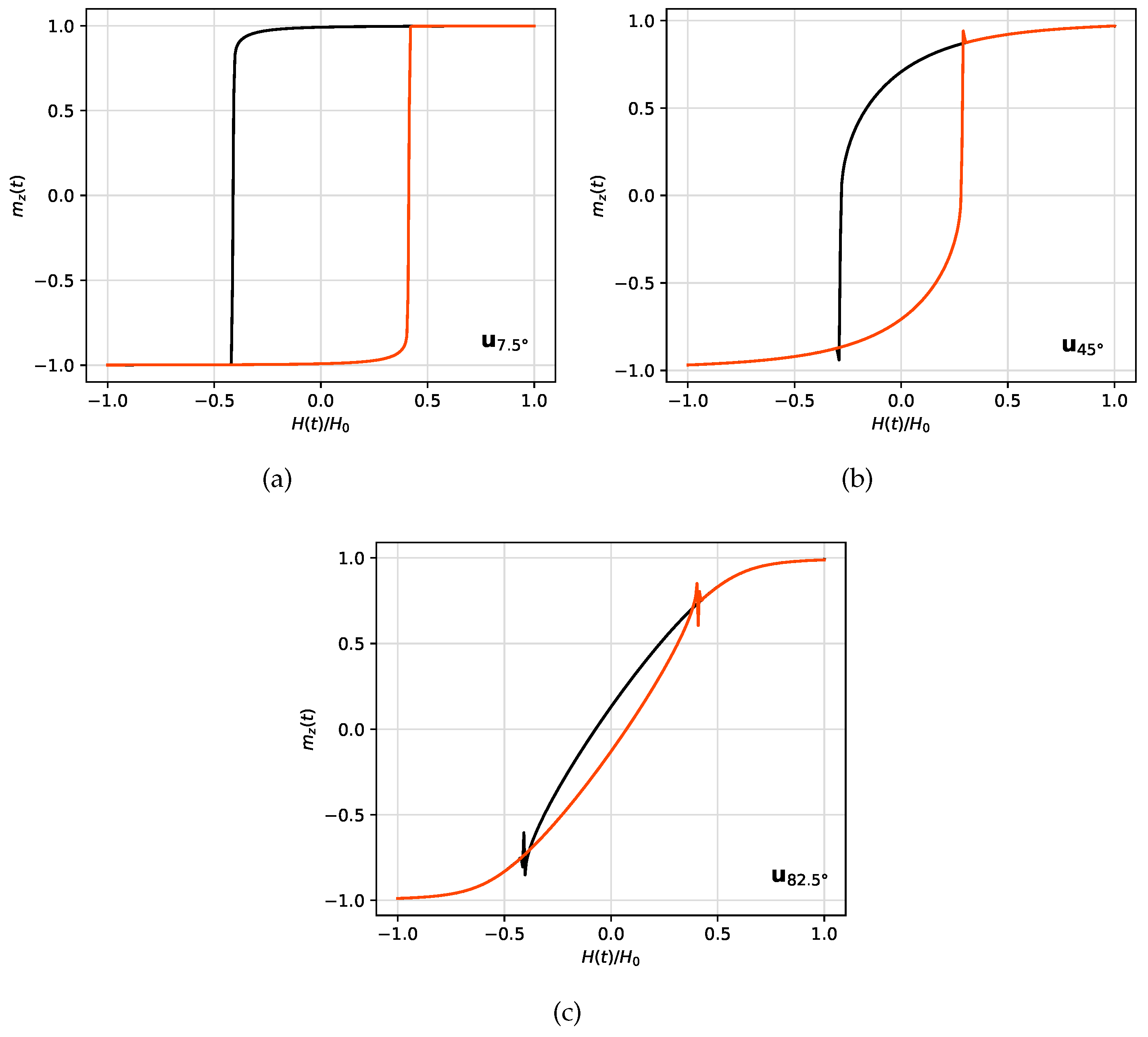

In addition, we also obtained the dynamic hysteresis loops for different easy-axis orientations of at a given field amplitude. The respective results are shown in

Figure 7 for

mT. Hence, as already unveiled, it is clear that the angle

of the easy-axis strongly affects magnetization reversal. As long as the easy-axis is oriented nearly perpendicular to the external AMF main direction, coercivity is significantly reduced. This presumably implies that as the external field is applied in a direction away from that of the easy-axis, it is easier to "pull" the magnetization out of the easy direction of anisotropy through different paths in phase space. This fact is also the responsible for the crossing of branches observed in the descending and ascending branches of the hysteresis loops at the switching fields, which is more noticeable for large values of

. This peculiar and surprisingly behavior of the crossing of hysteresis branches has been already demonstrated to occur in similar systems [

30,

31]. The crossing of the ascending and descending branches of the magnetization is observable when the applied external AMF is considerably far of the easy-axis, and this fact is associated with the energy minimum around the metastable state. Mathews et al. in [

30] demonstrated that such scenario can be occur for a Stoner–Wohlfarth particle with a unique anisotropy. Hence, we have been able to show that the crossing of branches is significantly affected by the orientation of the particle.

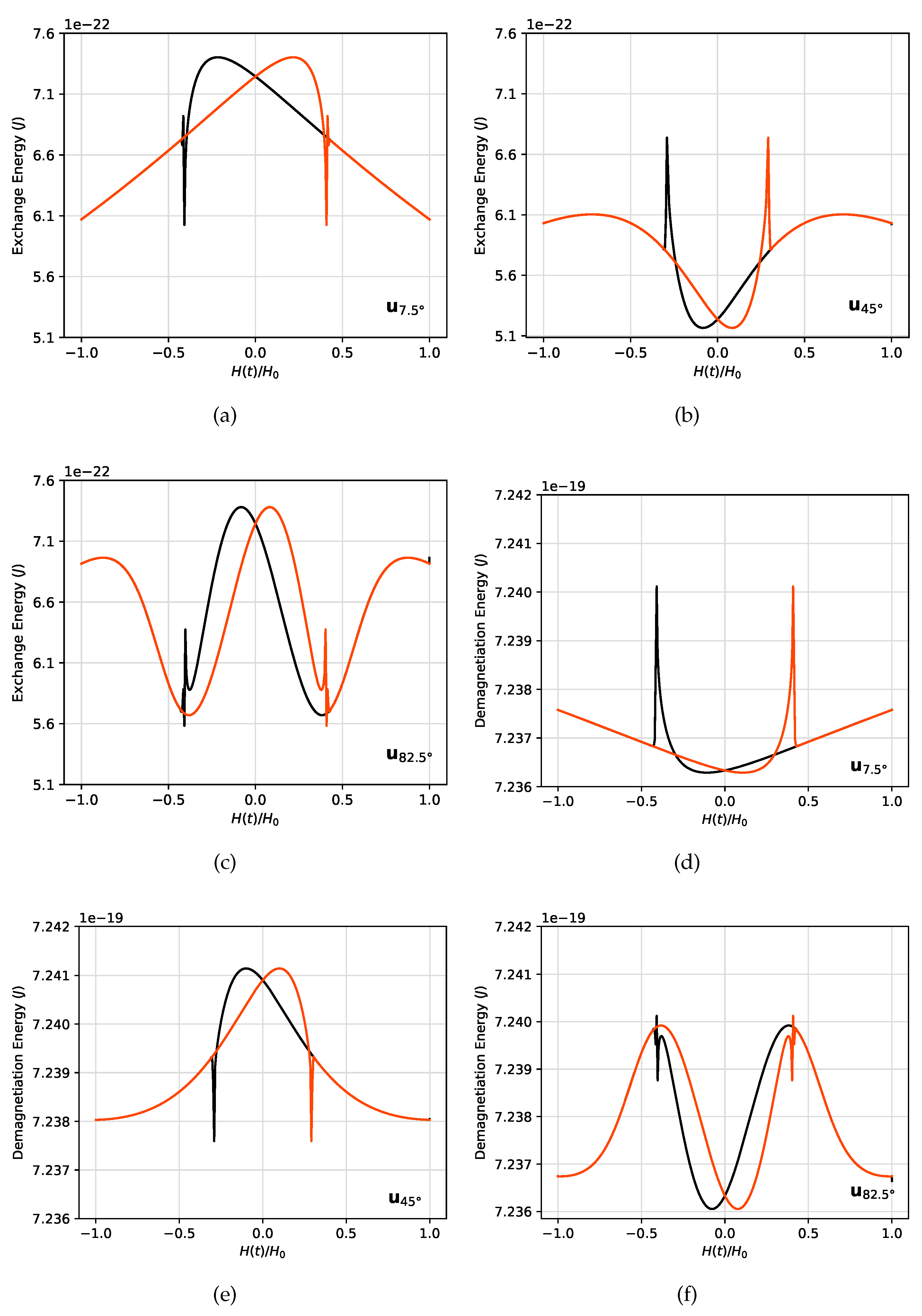

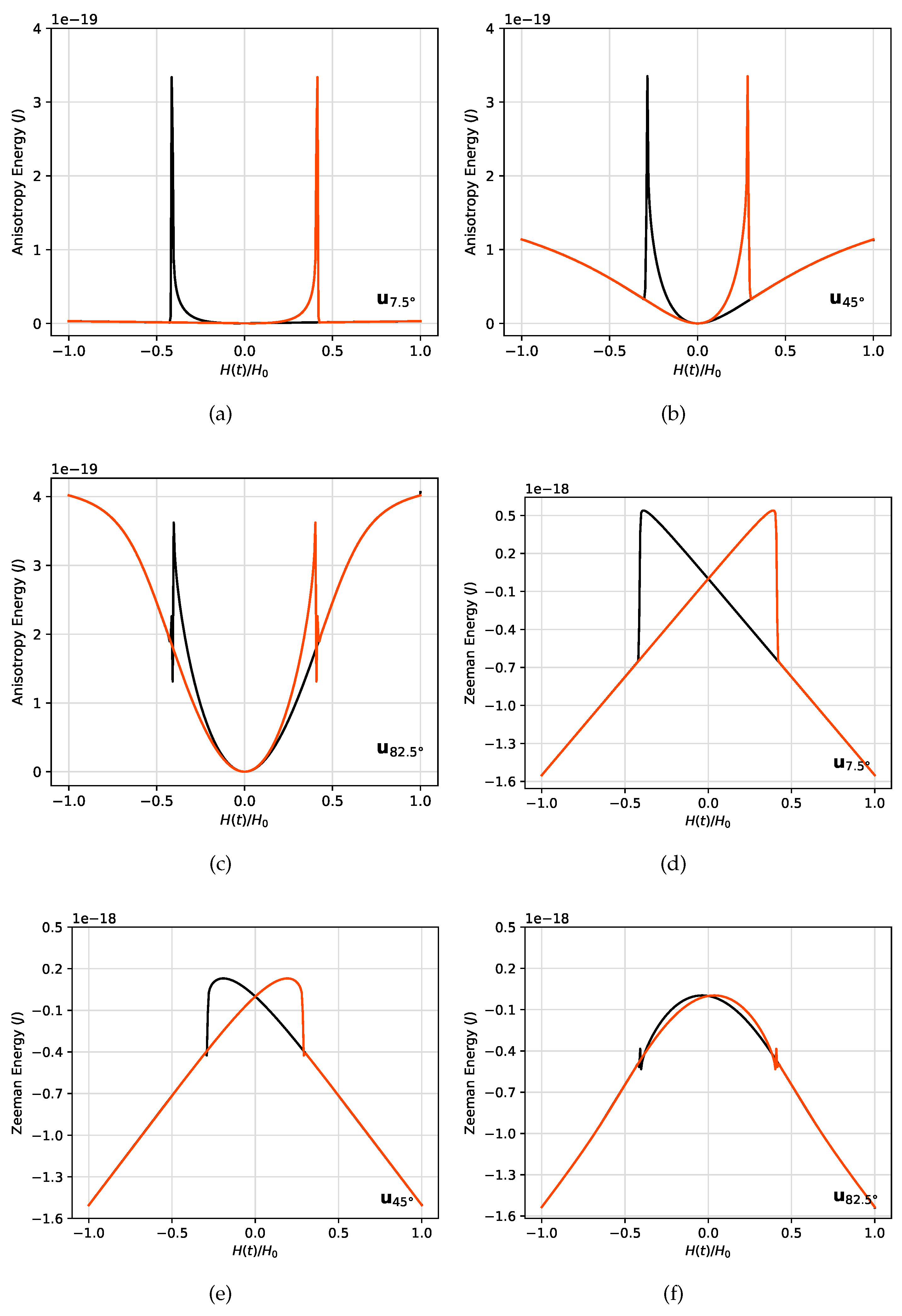

On the other hand, the micromagnetic energy contributions for each orientation of the easy-axis are shown in

Figure 8.

Figure 8a–c show the exchange energy for

,

and

, respectively.

Figure 8d–f stand for the demagnetization energy,

Figure 9a–c for the anisotropy energy and

Figure 9d–f for Zeeman energy, and for the same angles. We observe that the main micromagnetic energy contribution is given by the Zeeman energy, whereas the exchange energy contribution is the smallest one.

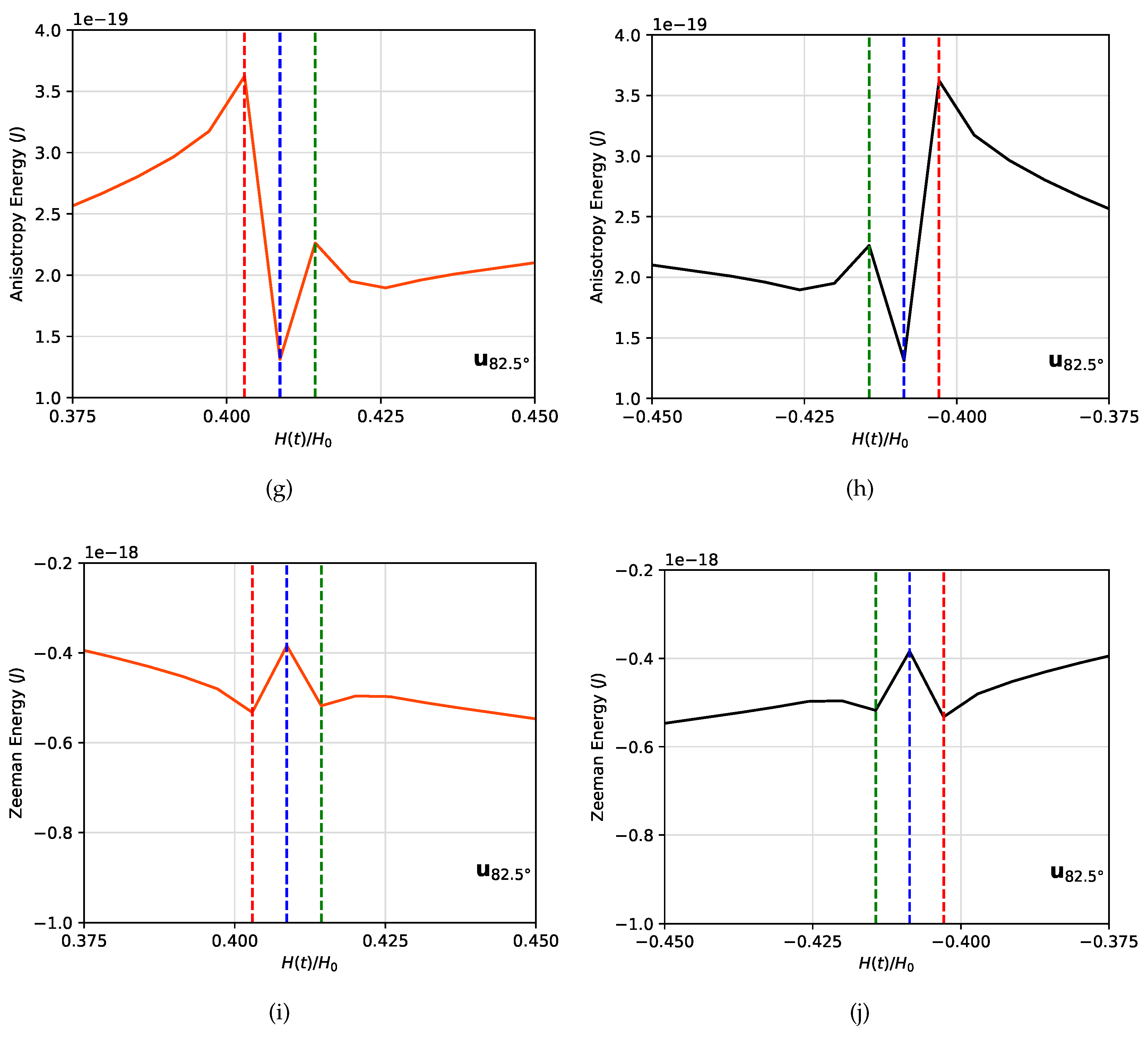

For the case of

, a zoom of the anisotropy and Zeeman energies is shown for clarity in

Figure 9. Some jumps at

,

and

are observed for both the ascending and descending field branches, which is consistent with a sort of transition zone. In particular, a significant increase in the value of the anisotropy energy is observed for

, which implies that the magnetic moments are not aligned with the easy-axis of the MNP. At the same value of

, a minimum in the Zeeman energy is observed, which implies an alignment of the magnetic moments with the field direction. In contrast, for

, the opposite scenario takes place. This means, that during the transition zone, magnetic moments become magnetically frustrated, as a consequence of the competition between these two energies.

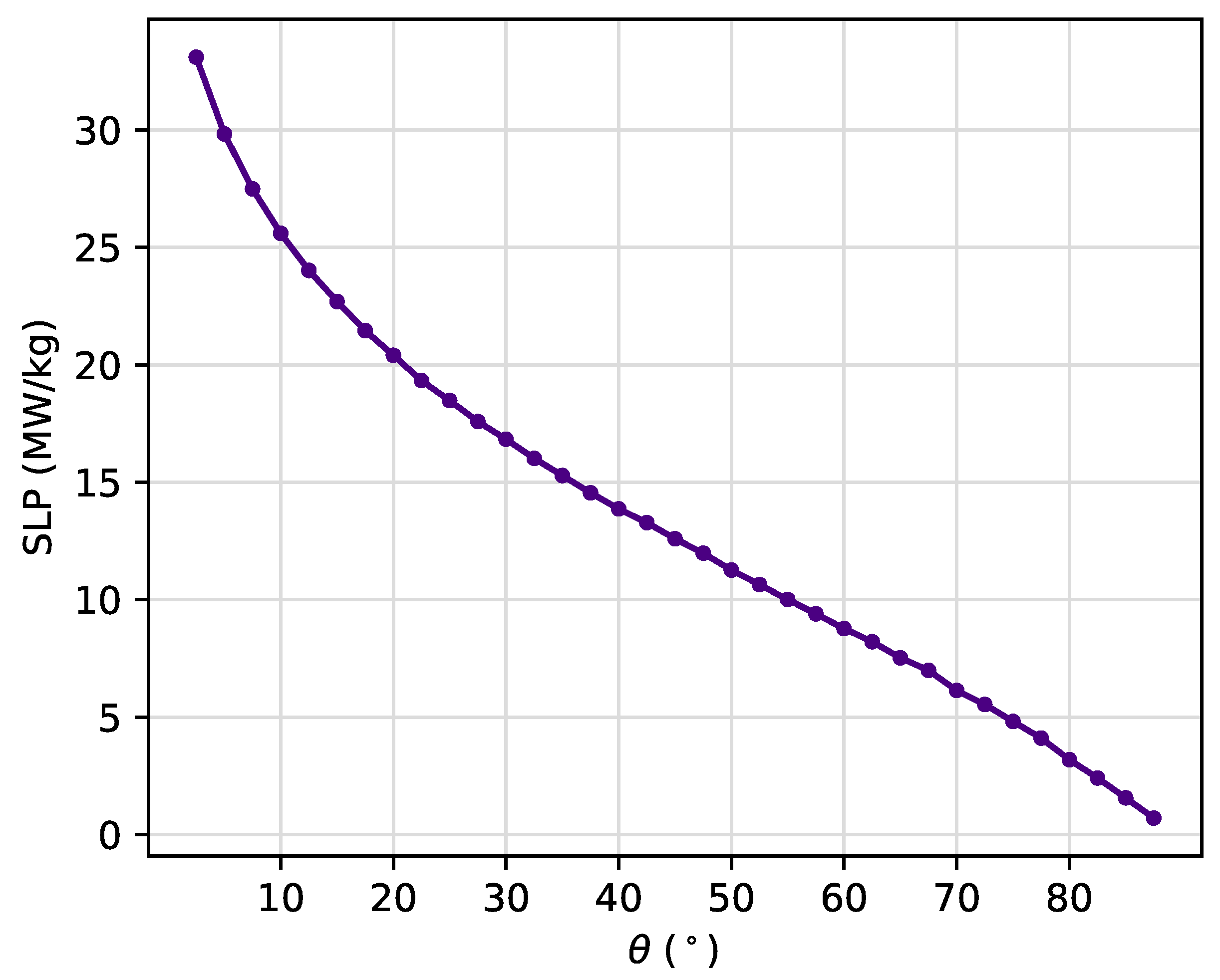

Finally, all of the above results lead to ask about the amount of heat that can be dissipated in terms of the specific loss power, which is proportional to the hysteresis loop area. Such quantity was computed using Equation

5, and the respective angular dependence is shown in

Figure 10. The SLP is maximized when the easy-axis of the MNP is oriented nearly parallel to the magnetic field direction, that is, for small angle values there is a greater efficiency in the amount of heat released to the environment. This is a novel result, because in the literature it is known that the specific loss power depends on parameters such as the size of the particles, the frequency and amplitude of the external AMF [

8,

9], but to the best of our knowledge, no studies on this specific regard have been addressed up to now. This result may shed lights on new ways to maximize the SLP for hyperthermia purposes.

Figure 1.

Time-dependent magnetization

(blue solid lines) of a magnetite nanoparticle of radius

nm under an external AMF

(gray dashed lines) with amplitude (

a)

mT and (

b)

mT. The first two periods are shown for each case, where the sample initially is fully ordered magnetized. The resulting response of the system can be divided into two regimes, (

a) a DOP one, and (

b) a DDP one. The inset shows the magnetization

as a function of external AMF

for each phase. The parameters are frequency

MHz, which is within range of the radio-frequency [

26], and angle

between the magnetic easy-axis of the MNP and the external AMF.

Figure 1.

Time-dependent magnetization

(blue solid lines) of a magnetite nanoparticle of radius

nm under an external AMF

(gray dashed lines) with amplitude (

a)

mT and (

b)

mT. The first two periods are shown for each case, where the sample initially is fully ordered magnetized. The resulting response of the system can be divided into two regimes, (

a) a DOP one, and (

b) a DDP one. The inset shows the magnetization

as a function of external AMF

for each phase. The parameters are frequency

MHz, which is within range of the radio-frequency [

26], and angle

between the magnetic easy-axis of the MNP and the external AMF.

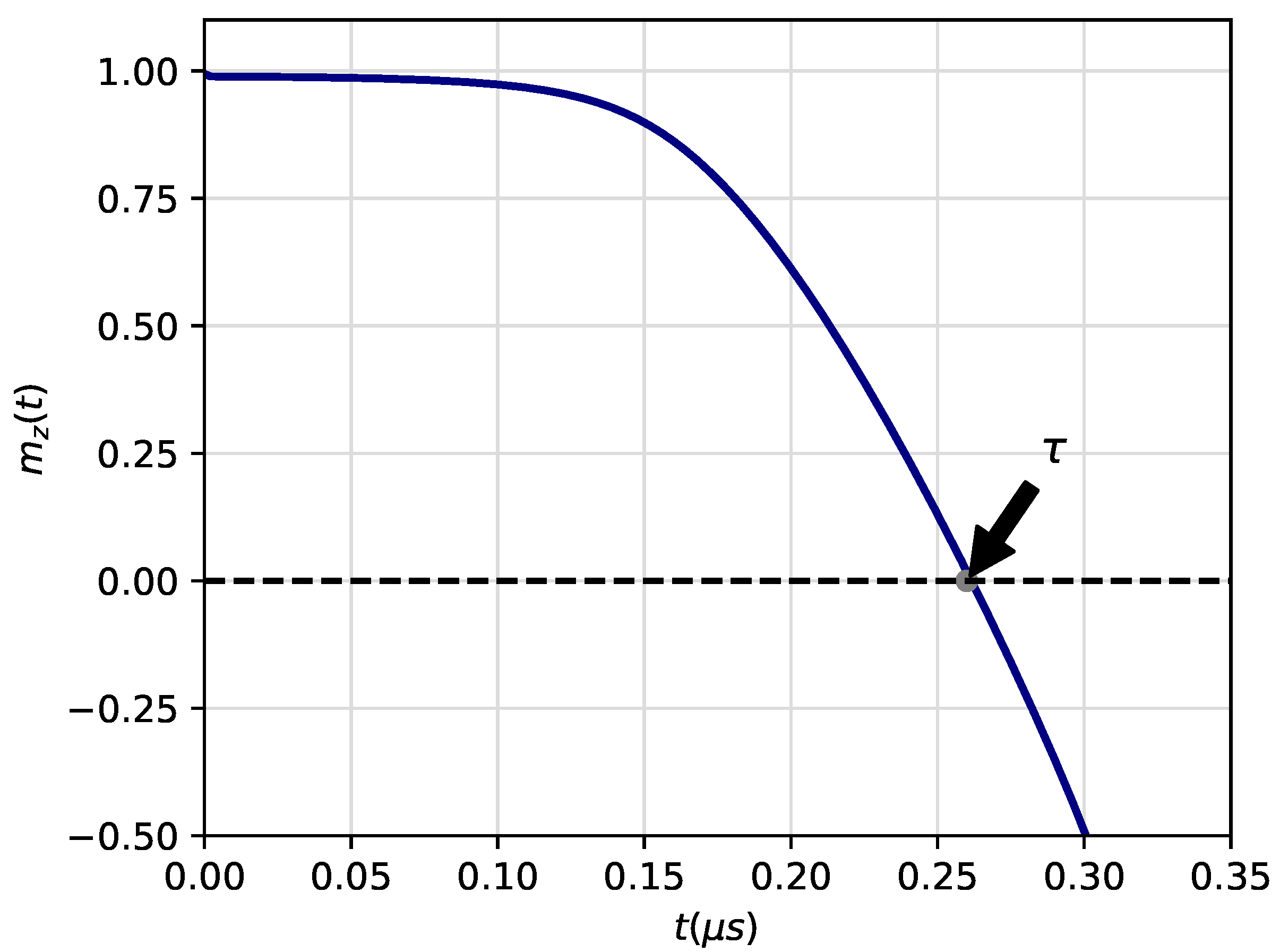

Figure 2.

Determination of the metastable lifetime corresponding to the first-passage time through zero magnetization from saturation state. The initial configuration corresponds to a fully saturated state along the main direction of the AMF. The parameters are Hz, mT and and orientation of the magnetic easy-axis relative to the field direction. The metastable lifetime in this case is s.

Figure 2.

Determination of the metastable lifetime corresponding to the first-passage time through zero magnetization from saturation state. The initial configuration corresponds to a fully saturated state along the main direction of the AMF. The parameters are Hz, mT and and orientation of the magnetic easy-axis relative to the field direction. The metastable lifetime in this case is s.

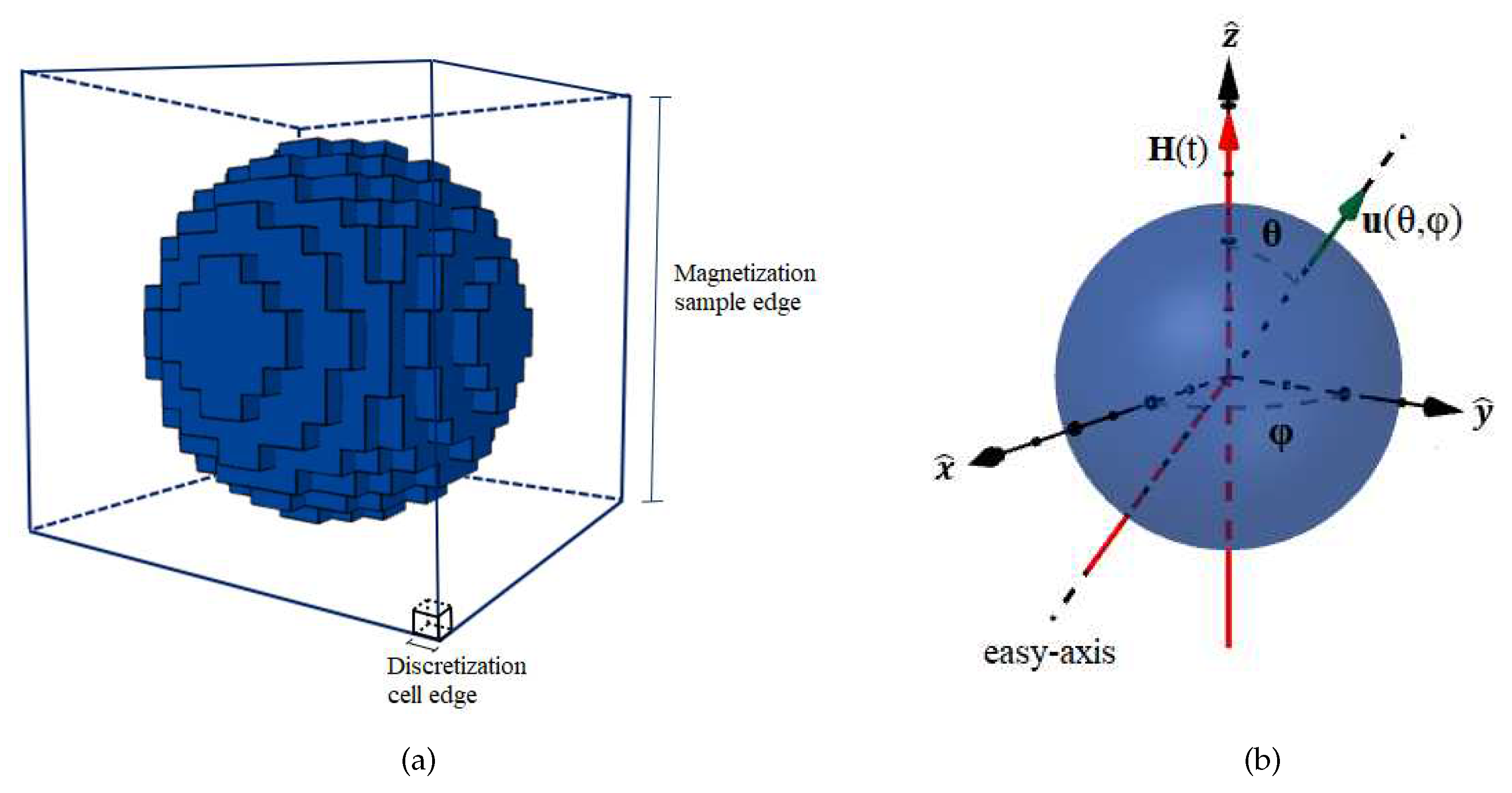

Figure 3.

(a) Finite-difference mesh used in our simulation. (b) Coordinates for the magnetic easy-axis orientation of the MNP. Where is the angle between the main direction of the external AMF and the magnetic easy-axis orientation.

Figure 3.

(a) Finite-difference mesh used in our simulation. (b) Coordinates for the magnetic easy-axis orientation of the MNP. Where is the angle between the main direction of the external AMF and the magnetic easy-axis orientation.

Figure 4.

Time dependence of the -component of magnetization and the external AMF. Polar angles for the easy-axis orientation are: (a) , (b) and (c) , for an amplitude of mT. Polar angles for the easy-axis orientation are: (d) , (e) and (f) , for an amplitude of mT. Figures (a)-(c) show a typical dynamic ordered phase (DOP) whereas figures (d)-(e) show a typical dynamic disordered phase (DDP).

Figure 4.

Time dependence of the -component of magnetization and the external AMF. Polar angles for the easy-axis orientation are: (a) , (b) and (c) , for an amplitude of mT. Polar angles for the easy-axis orientation are: (d) , (e) and (f) , for an amplitude of mT. Figures (a)-(c) show a typical dynamic ordered phase (DOP) whereas figures (d)-(e) show a typical dynamic disordered phase (DDP).

Figure 5.

Dynamic phase diagram between the DOP and the DDP. The coloured regions represent the DOP (pink) and DDP (violet) phases. Error bars are determined by the step of the AMF, namely mT.

Figure 5.

Dynamic phase diagram between the DOP and the DDP. The coloured regions represent the DOP (pink) and DDP (violet) phases. Error bars are determined by the step of the AMF, namely mT.

Figure 6.

Dependence of the metastable lifetime with the polar angle for mT.

Figure 6.

Dependence of the metastable lifetime with the polar angle for mT.

Figure 7.

Hysteresis loops for a field amplitude mT and for three different angles of the applied feld with respect to the easy-axis orientations of the MNP, namely , and . The ascending curves (from negative to positive saturation) are shown in orange, while the descending curves (from positive to negative saturation) are shown in black. For and , crossing of branches is evident.

Figure 7.

Hysteresis loops for a field amplitude mT and for three different angles of the applied feld with respect to the easy-axis orientations of the MNP, namely , and . The ascending curves (from negative to positive saturation) are shown in orange, while the descending curves (from positive to negative saturation) are shown in black. For and , crossing of branches is evident.

Figure 8.

Micromagnetic energy contributions as a function of the reduced applied field for different easy-axis orientations , and . (a-c) Exchange energy. (d-f) Demagnetization energy. (g-i) Anisotropy energy. (j-l) Zeeman energy. Orange lines stand for the ascending curves, while the descending curves are shown in black lines.

Figure 8.

Micromagnetic energy contributions as a function of the reduced applied field for different easy-axis orientations , and . (a-c) Exchange energy. (d-f) Demagnetization energy. (g-i) Anisotropy energy. (j-l) Zeeman energy. Orange lines stand for the ascending curves, while the descending curves are shown in black lines.

Figure 9.

Zoom of the (a-b) anisotropy and (c-d) Zeeman energies as a function of for . The ascending field branch is depicted in orange whereas the descending field branch is shown in black. At (red dashed line), (blue dashed line) and (green dashed line), energy contributions exhibit some jumps.

Figure 9.

Zoom of the (a-b) anisotropy and (c-d) Zeeman energies as a function of for . The ascending field branch is depicted in orange whereas the descending field branch is shown in black. At (red dashed line), (blue dashed line) and (green dashed line), energy contributions exhibit some jumps.

Figure 10.

Variation of the SLP as a function of the angle of easy-axis orientation for an amplitude mT of the external AMF.

Figure 10.

Variation of the SLP as a function of the angle of easy-axis orientation for an amplitude mT of the external AMF.

Table 1.

Physical properties of magnetite [

26,

27].

Table 1.

Physical properties of magnetite [

26,

27].

| Chemical formula |

(Am) |

A (Jm) |

K (Jm) |

(nm) |

(Kgm) |

|

|

|

|

|

5240 |