1. Introduction

Terraces are defined as a small step-like ridge on a steep surface or a flattened section of a hilly area. Some of the terraces may spontaneously form as a result of certain natural phenomena. Terraces formed as such are called terracets [

1]. Additionally, terraces can also be built anthropogenically for the purposes of agricultural activities, preventing erosion, landslides, and floods. The most widespread human-made terraces are agricultural terraces built for agricultural purposes. Agricultural terraces are among agricultural landscapes, which are the first and most basic form of interaction between humans and the environment [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Agricultural terraces originated as a way for people to carry out agricultural activities in mountainous areas [

10]. They are traditional agricultural structures that alter the slope of sloping land to allow agricultural activities [

11,

12]. The history of agricultural terraces has been synchronized with the development of civilization. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, whose existence today cannot be proven conclusively but is depicted by many ancient historians such as Quintus Curtius Rufus and thought to have been located in the city of Al Hillah in present-day Iraq, was regarded as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world as listed by Hellenic culture [

13]. The Hanging Gardens are still recognized as one of the most spectacular agricultural terraces even in modern days [

14,

15].

According to previous research, the oldest surviving terraces are located in Middle Eastern countries such as Syria [

16], Palestine [

17], and Yemen [

18], and are estimated to be approximately 5000 years old. Agricultural terraces built by the Incas in ancient times on the slopes of the Andes Mountains in South America are still being used for agricultural activities [

19,

20]. In 2007, a Swiss organization recognized the ancient city of Machi Pichu, where the agricultural terraces are located, as one of the new seven wonders of the world [

21]. Currently, various vegetables, mainly maize, are cultivated on the Machu Picchu terraces. In Europe, especially in Mediterranean countries such as Spain [

22,

23], Italy [

24], Greece [

25,

26], and Türkiye [

27] many terraces date back to ancient times.

Agricultural terraces are anthropological traces of agricultural landscapes that cover large areas of the world [

28,

29,

30], which often maximize the use of irrigation water [

31,

32], reduce erosion [

33,

34,

35], facilitate human labor and irrigation on slopes [

36] and have benefits in terms of vegetation restoration, land productivity, and crop yields [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42].

Agricultural terraces are exceptional cultural landscapes, a physical product of the traditional form of landscape components, continuity of landscape function, traditional knowledge, rituals, architecture, and architectural construction techniques, underpinned by human socioeconomic and religious values [

43]. Therefore, terraced landscapes are regarded as an integral part of the rural landscape and cultural heritage [

44]. The architectural features of agricultural terraces, the materials used in their construction, the construction methods, and the landscapes they constitute as a whole with the rural landscape make them precious in terms of cultural heritage [

12]. UNESCO recognizes agricultural terraces as cultural landscapes and includes them within the scope of tangible cultural heritage. UNESCO has included six transboundary properties on the World Heritage List and 121 properties on the list of World Cultural Landscapes. Several of these areas included agricultural terraces. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) classifies agricultural terraces as "Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS)". FAO defines agricultural terraces as sustainable land use systems and important landscapes that are skillfully built by rural communities as a source of food supply and livelihoods, but also support social and cultural structure [

45].

Agricultural terraces are also essential for the services they provide within the ecosystem [

20,

46]. Agricultural terraces are carbon sinks for the ecosystems in which they are located [

47,

48]. They also provide habitat for other species such as invertebrates, reptiles, birds, and insects, supporting biodiversity [

49,

50,

51]. Terrace walls absorb heat during the day and release it in the evening, creating a microclimate for plants and animals [

52]. The moist and vegetated environment at the base of the terrace walls provides a breeding ground for invertebrates [

53,

54]. The gaps between the stones forming the terrace walls provide shelter for invertebrates, reptiles, and insects in summer.

Furthermore, crops cultivated on terraces also contribute to agricultural biodiversity [

46,

55,

56,

57]. Due to global warming, environmental pollution, and decreasing access to food in the twenty-first century, agricultural biodiversity has become increasingly important [

58,

59,

60]. In today’s world of global environmental problems, terraces provide sustainable food production with the agricultural biodiversity they offer [

61,

62,

63]. The unique rural landscapes formed by terraces [

64,

65] offer the possibility of recreational use [

66,

67], thereby allowing agricultural terraces to be associated with different forms of tourism. Agricultural terraces constitute a potential for various types of alternative tourism such as agrotourism, eco-tourism, and gastro-tourism, and that potential offers an opportunity for local and regional development [

68]. However, it is only possible to take advantage of this opportunity if agricultural terraces are designed in accordance with the basic principles of sustainable tourism. In particular, the principles of sustainable tourism for the conservation of tangible and intangible cultural heritage, biodiversity, and visual integrity can serve as a general planning framework for the sustainable use of agricultural terraces in the context of tourism [

69]. Offering traditional and safe forms of food production as well as environmental, social, cultural, and economic benefits, agricultural terraces are also essential for the world’s shared goal of sustainable development (SDG-Agenda 2030) [

70].

The present study was conducted to analyze some agricultural terraces in Cittaslow Uzundere, which is located in the southern part of the Coruh Basin in the western part of the Western Caucasus Ecoregion, one of the world’s 200 most important ecologically sensitive areas and 35 hotspots. There are numerous agricultural terraces in the Uzundere district, built in ancient times, which are an integral part of traditional agriculture and local culture. However, these terraces are currently being abandoned for various reasons and are in danger of disappearing in the future. The abandonment of these terraces threatens the sustainability of ecosystems, biodiversity, agricultural product diversity and cultural landscapes in the district. Within the scope of the present study, agricultural terraces in the Erikli neighborhood, which hosts one of the densest terraces in the district, were mapped with the help of drone technology and geographical information systems (GIS) and analyzed in terms of their size and density. Hence, it is crucial to identify the agricultural terraces in the region and to expand the limited studies in the area.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Areas

The study was conducted in the Uzundere district of Erzurum province, located in northeastern Türkiye (

Figure 1). Uzundere district is one of Türkiye’s 21 settlements on the cittaslow list. Uzundere is located between 40º 42’ - 40º 26’ north latitude and 41º 26’ - 41º 47’ east longitude. The area of the district is 84.000 hectares, and the altitude is 1.050 m.

Uzundere is geographically located in the Tortum Stream Valley, one of the valleys that make up the Çoruh Basin. The Çoruh Basin formed the western part of the Caucasus Ecoregion, announced by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as one of the 200 important ecoregions and 35 hotspots in the world due to its rich biodiversity and threatened species and ecosystems [

71]. The Tortum Stream Valley, located in such an important and sensitive region, is one of Turkey’s 305 Important Nature Areas.

There are 327 herbaceous and woody plant species along the Tortum Stream Valley, and 89 are endemic. Vegetation characteristics of the Iranian-Anatolian, European-Siberian, and Mediterranean phytogeographic regions are observed throughout the valley. Located on the Caucasus-Africa bird migration route, the Tortum Stream Valley is the habitat of more than 200 bird species and mammal species such as lynx, wolf, wildcat, brown bear, and mountain goat [

72].

One of the most important water resources of Uzundere is the Tortum Stream. Many streams feed the Tortum Stream flowing along the valley. In addition to Tortum Stream, other important hydrographic resources of the district are Tortum Lake, a landslide sed lake, and Tortum Waterfall, one of the most important waterfalls in the world, which falls from a height of 48 meters.

The geological structure of Uzundere generally consists of volcanic rocks such as basalt and andesite from the Paleocene and Lower-Middle Jurassic periods and classical carbonate sedimentary rocks from the Upper Jurassic-Upper Cretaceous period [

72]. Characteristic folded structures were formed especially due to the compression of sedimentary rocks by tectonic movements [

73].

The general geomorphologic structure of Uzundere consists of a narrow valley floor and mountain and hill slopes. The height of the hills and mountains surrounding the district reaches up to 2500 meters in places. The Tortum Stream, which flows in the north-south direction through the valley floor, and the other streams that feed the Tortum Stream are the main elements that shape the valley.

The sloping land structure of the region, which is not suitable for agriculture, was terraced and agricultural activities have been carried out by the local people since the past. The district consists of 18 neighborhoods and one of them is the Erikli neighborhood located in the center of the Uzundere district. Along with its central location, the Erikli neighborhood is one of the most densely populated areas of agricultural terraces in the district (

Figure 2). Furthermore, it is more accessible than other regions due to its central location. Therefore, agricultural terraces in the Erikli neighborhood were covered in the study. The slope, aspect, contour and hydrography maps of the study area, Erikli neighborhood, and its immediate surroundings are given in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

The stones obtained from the fragmentation of the volcanic bedrock of the Paleocene period, during which the geological formation of Tav Mountain, one of the important mountains of the region, and its surroundings took place, were used during the construction of agricultural terraces in the district [

12]. After the reclamation of the Tortum Stream in the 1990s, floodplains were used as agricultural areas and agricultural activities in these areas were easier compared to the terraces. These and other factors such as the decrease in the population engaged in agriculture gradually and migration from rural to urban areas are among the reasons for the abandonment of the terraces in the region.

2.2. Methods

The study employed a 3-stage methodology including field and office studies and the methodology diagram of the study is presented in

Figure 7.

1. Survey activities started on 13.07.2021 and several photographs were taken along the path from the edge of the Tortum Stream to the ruins of the old church in the Erikli neighborhood. On 31.03.2022, 01.04.2022, 02.04.2022, 24.09.2022, 01.12.2022, and 02.12.2022, 2k and 1080p videos of the study area were captured by a drone. Lidar-integrated commercial drone technology is a frequently used method in the last decade for determining agricultural terraces and archaeological sites and preparing 3D maps [

42,

74,

75]. However, the expensiveness of commercial drones and the need for official permits in Turkey forced the use of drones under 250 gr, which is cheaper and includes fewer permit procedures, in this study carried out for the mapping of agricultural terraces. Hence, DJI Mini 2 lightweight drone was used in the study. The specifications of the DJI Mini 2 lightweight drone are given in

Table 1.

2. After the field studies, the images acquired from the Google Earth Pro program, orthophotos derived from the ’Republic of Türkiye Ministry of National Defense General Directorate of Mapping’ KURE application [

76], and orthophotos derived from the ’Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change General Directorate of Geographical Information Systems’ ATLAS application [

77] were combined by image overlaying with geographic information system software (ESRI-GIS).

3. In order to determine the character of terraces in the region, terrace classes used in ’ALPTER-Terraced Landscapes of the Alps’ and ’Interreg IIIB Alpine Space Project’ were employed. The method was introduced by Scaramellini (2005) and utilizes a measurement criterion based on size and density indices to quantify terraces in a region [

78,

79]. Under this method, the Terrace Size Index (TSI) defines the size of the terraced area in an area of 1 hectare. Based on this definition, three qualitative classes are established: micro terrace if the terrace size is 0.01-0.33 ha, meso terrace if 0.33-0.66 ha, and macro terrace if 0.66-1.00 ha. The Terrace Density Index (TDI) is measured as the linear sum of the length of terraces in 1 ha and is classified as low density (5-200 m/ha); medium density (200-800 m/ha) and high density (>800 m/ha) [

79]. Increasing terrace density means that the original terrain topography is being moved away from the original topography. As maintenance decreases on terraces with high densities, fragility increases [

80]. Spatial analyses in TDI and TSI calculations were conducted with ESRI-ArcMap software.

3. Results and Discussion

The Erikli neighbourhood of the Uzundere district, located in the northern of the Eastern Anatolia Region of Türkiye has many agricultural terraces which are an essential part of the cultural landscape reflecting human-nature interaction. The rough terrain of the district, which restricts agricultural activities, has led the inhabitants to search for alternative ways of agricultural production for centuries. The agricultural terraces that emerged as a result of this pursuit have shaped the cultural landscape texture and identity of the Tortum Lake Basin and the Coruh Valley. The stones collected from the surroundings and occasionally obtained by crushing the bedrock on the land were used for the construction of the terrace gardens analyzed within the scope of the present study. The stones were carefully piled using dry stone masonry technique, and terrace walls were built (

Figure 8). The dry-stone wall technique is an old architectural construction technique. The technique was included in the ’Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity’ by UNESCO with the application of eight European countries in 2018 [

81]. Although the dry-stone wall technique is recognized as a shared heritage of eight European countries, the fact that the terrace walls analyzed were built with this technique is of significance in terms of reflecting the intangible cultural heritage element in Northeastern [

12]. Beams, a traditional method, were used to enhance the durability of the terrace walls. The use of beams is a traditional method that has existed for more than 2500 years and is also widely spread in Turkish architecture [

82].

In order to map the terraces, drone photographs were taken at different time periods in the study area (

Figure 9). The drone photographs provided additional supporting material for mapping the terraces. A plan view showing the general formal characteristics of the agricultural terraces is shown in

Figure 10.

In the study area, 37.37 hectares of terrace area and a total length of 22195 meters of terrace walls were recorded. Terrace Size Index (TSI) and Terrace Density Index (TDI) maps were created using ArcMap’s areal analysis and density algorithms.

Figure 11 shows the TSI and TDI maps of the study area, while

Figure 12 shows the spatial and proportional distribution of TSI and TDI.

Figure 11 shows that the terraces analyzed in the study consist of micro-sized terraces with 8.82 ha, meso terraces with 14.95 ha, and macro-sized terraces with 13.6 ha in terms of TSI. In terms of proportional distribution, 36% of the total terrace area consists of macro terraces, 40% of meso terraces, and 24% of micro terraces. In terms of TDI, it was concluded that 4.86 ha (13%) were low density, 27.75 ha (74.30%) were medium density, and 4.76 ha (12.70%) were high density.

Figure 13 shows the map of the size and density of mixed classes and

Table 2 shows the data for the spatial distribution of terrace classes:

Table 2.

Spatial and proportional distribution of terrace classes.

Table 2.

Spatial and proportional distribution of terrace classes.

The average terrace length was calculated as 593.3 m/ha. It was established that meso/medium-characterized agricultural terraces, which constitute 40.03% of the region, cover the largest area.

In their study conducted in the Alps, Varotto & Ferrarese (2008) recorded micro and meso terraces as 28% and 55% respectively in the Granile region, and macro terraces as 50% and 60% respectively in the River Brenta and Aosta Valleys. The maximum terrace density index was 1278 m/ha for Granile, 1626 m/ha for the River Brenta Valley, and 1807 m/ha for the Aosta Valley. They concluded that 77% of the terraces in Granile, 79% in the River Brenta Valley, and 38% in the Aosta Valley are composed of medium-density terraces. The size index of the terraces analyzed in the study was determined as 23.6%, 40%, and 36.4% for micro, meso, and macro, respectively. The maximum terrace density index was calculated as 954.26 m/ha in the vegetable and vine growing areas in the south of Erikli neighborhood, the minimum as 471.34 m/ha in the easily accessible and low-sloping areas in the west of Erikli neighborhood, and the average as 523.29 m/ha. The findings of the study revealed that 76.4% of the terraces in the Erikli neighborhood are meso and macro-character terraces and therefore have similar characteristics to the terraces in the Alps. This result also shows that the terraces in the Erikli neighbourhood have a high fragility potential and need for maintenance.

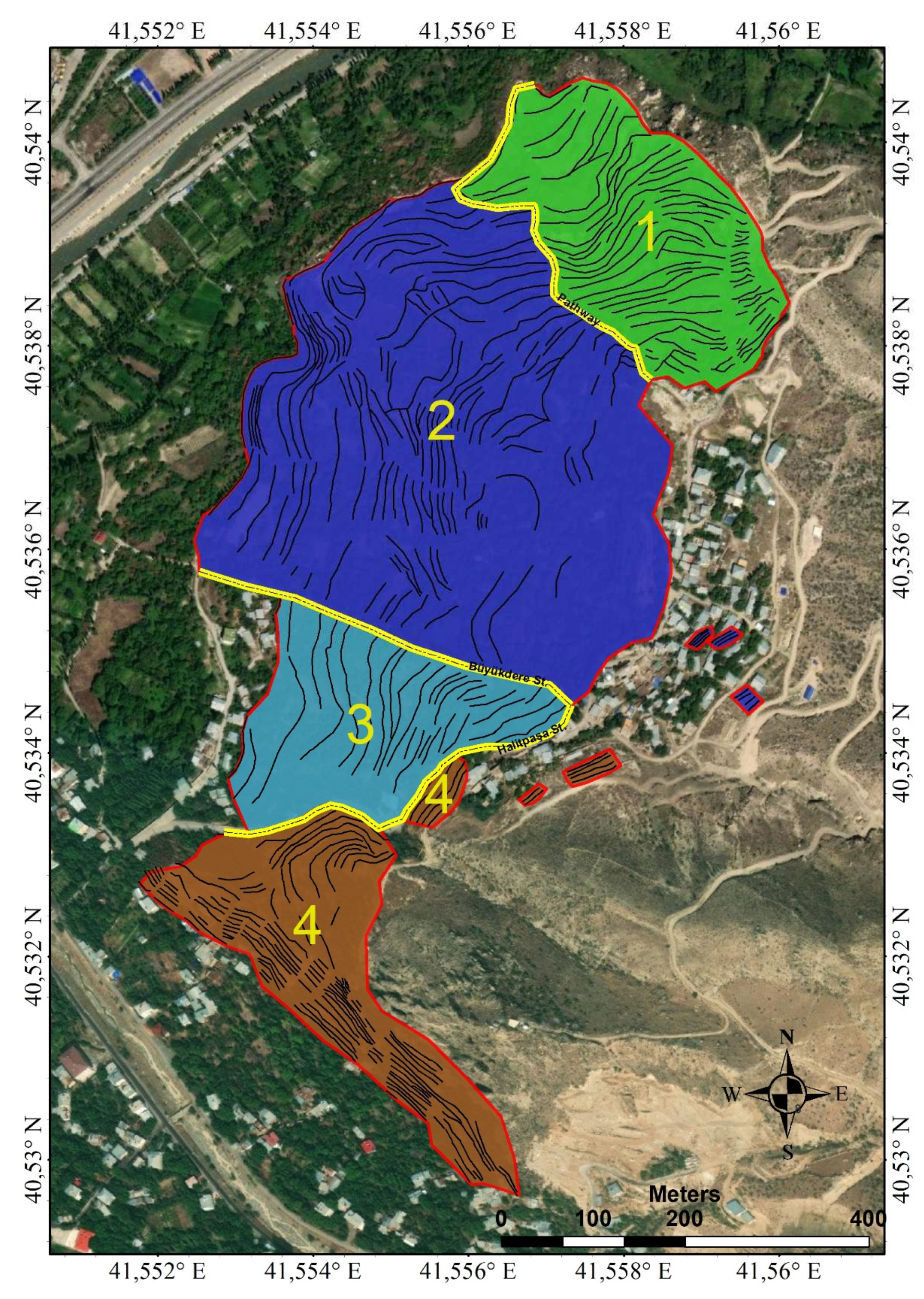

A pathway crossing the terraces in the study area and Büyükdere and Halitpaşa roads divide the region into four physical parts. Thus, the terraces in the area are divided into four sections from north to south. In the terrace sections, 82, 154, 29, and 131 terraces were identified from north to south (

Section 1,

Section 2,

Section 3 and

Section 4) respectively. Average plot sizes were calculated as 815.85 m

2, 1267.53 m

2, 1800 m

2, and 456.49 m

2, respectively (

Figure 14).

According to the parcel classification of Agnoletti et al., 2019 (small<556 m

2, medium; 556-1533 m

2, large>1533 m

2);

Section 4 consists of small terraces,

Section 1 consists of medium terraces,

Section 2 consists of large terraces to the east and medium terraces to the west, and

Section 3 consists of large terraces. The total terrace lengths in the sections are 4912 m, 9115.6 m, 2460.4 m, and 5706.5 m respectively. Terrace densities are 734.3 m/ha, 467 m/ha, 471.3 m/ha, and 954.3 m/ha respectively. During the field studies, it was observed that

Section 4, which has a high density of terraces, is generally located behind the village houses, and mainly vegetables and grapevines are cultivated, whereas in

Section 2 and

Section 3, various fruit trees, especially mulberry and walnut, are grown; in

Section 1, vegetables are mainly cultivated in the western regions with easy access, while mulberry, walnut, and grapevine are grown in the other regions.

Özgeriş and Karahan (2022) reported that 78% of the terraces they studied in different regions of Uzundere had extremely steep slopes [

12]. It was detected that 51.6% of the terraces in the Erikli neighborhood have extremely steep slopes. It can be argued that the terraces analyzed in the present study were built on less sloping lands than the terraces analyzed by Özgeriş and Karahan (2022). Nevertheless, the results of both studies show that the terraces in the region enable agricultural activities on high slopes. Additionally, Koulouri & Giourga (2007) reported that agricultural terraces in the Mediterranean Basin had slope values ranging from 25% to 40%. Studies with similar results indicate that agricultural terraces are a significant form of land use [83].

It was noted that the terraces analyzed within the scope of the study were neglected and damaged in terms of structural and vegetative aspects (

Figure 15).

In some terraces where agricultural activities were carried out, it was considered that there was a transformation in terms of architectural construction techniques with the development and change in technological, social, economic, and cultural spheres. In some of the terraces, for instance, the dry-stone wall technique was replaced with cement mortared stone walls. It was also observed that plastic (PVC) pipes were used instead of open water channels in irrigation and drainage systems. The findings are similar to those of Özgeriş and Karahan (2022), who examined 9 agricultural terraces in the study area. It is expected that migration from rural areas to cities as a result of socio-economic and cultural transformation and the fragmentation of agricultural lands through inheritance may result in the complete disappearance of agricultural terraces and specialized construction techniques in the near future.

4. Conclusions

The present study was conducted in Uzundere, one of the 21 settlements in Türkiye that are members of the International Network of Cittaslow. The study aimed to map and classify the agricultural terraces in the Erikli neighborhood, which is one of the areas with the highest density of agricultural terraces in Uzundere, in terms of density and spatial size. As part of the study, surveys were conducted in the area, and drone photographs were obtained. GIS-based analyses were carried out together with satellite images of the area. The results show that collapsing satellite images and orthophotos with drone photographs is an easy way to map agricultural terraces.

The study showed that there are many agricultural terraces in the Erikli neighbourhood of Uzundere. These terraces are mostly medium and high density, meso and macro terraces. They are also structurally and vegetationally neglected. This is mainly due to the fragmentation of agricultural lands through inheritance and abandonment due to migration from rural to urban areas. The high density and neglect of the terraces increase their fragility and encourage their disappearance.

The research shows that the terraces in the region were constructed with the use of traditional construction techniques such as dry stone wall technique and beam application. In some terraces where agricultural activities are still carried out, the original architectural construction techniques have been replaced by modern materials and construction techniques. Undoubtedly, this is directly related to changes in social, cultural, economic, and technological spheres. However this threatens the sustainability of agricultural terraces and their specialized construction techniques in the future. Moreover, this will also have a negative result in terms of the sub-criteria of environmental integrity and conservation of biodiversity, which are the requirements of the Cittaslow status.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.K., M.Ö. and O.G.; methodology, F.K. and O.G.; software, O.G.; validation, F.K., M.Ö. and O.G.; investigation, F.K., M.Ö. and O.G.; resources, F.K., M.Ö., N.D., I.S., A.K. and O.G.; data curation, F.K., M.Ö. and O.G.; writing—original draft preparation, F.K., M.Ö., N.D., I.S., A.K. and O.G.; writing—review and editing, F.K., M.Ö., N.D., I.S., A.K. and O.G.; visualization, O.G.; supervision, F.K.; project administration, F.K. and O.G.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was funded by ATATÜRK UNIVERSITY, grant number FDK-2022-10399 This grant support was used for drone filming. The geographical information systems and field research were funded by the authors themselves.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Demirciler, V. Agricultural terraces and farmsteads of Bozburun Peninsula in antiquity. Ph.D. Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Türkiye, 2014.

- Antrop, M. Why landscapes of the past are important for the future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 21–34, . [CrossRef]

- Robertson, G.P.; Swinton, S.M. Reconciling agricultural productivity and environmental integrity: a grand challenge for agriculture. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2005, 3, 8-46.

- Plieninger, T.; Höchtl, F.; Spek, T. Traditional land-use and nature conservation in European rural landscapes. Environ. Sci. Policy 2006, 9, 317–321. [CrossRef]

- Verburg, P.H.; Schulp, C.; Witte, N.; Veldkamp, A. Downscaling of land use change scenarios to assess the dynamics of European landscapes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 114, 39–56, . [CrossRef]

- Karahan, F.; Orhan, T. Uzundere Vadisi Tarımsal Faaliyetlerinin Peyzaj Çeşitliliğine Etkileri. Alinteri Journal of Agriculture Science. 2008, 15, 26–32.

- Fahrig, L.; Baudry, J.; Brotons, L.; Burel, F.G.; Crist, T.O.; Fuller, R.J.; Sirami, C.; Siriwardena, G.M.; Martin, J. Functional landscape heterogeneity and animal biodiversity in agricultural landscapes. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 101–112, . [CrossRef]

- Sezen, I. Türkiye’de Tarımsal Peyzaj. Harman Time. 2014, 2, 78–80.

- Atik, M.; Taşkan, G.; Balta, S. Kırsal–Tarımsal Peyzajların Korunmasında GIAHS Küresel Öneme Sahip Tarımsal Miras Sistemleri ve Akdeniz Selge Örneği. Journal of Agriculture Faculty of Ege University. 2022, 59(2).

- Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Shi, C.; Deng, B. Tourists’ Perceived Attitudes toward the Famous Terraced Agricultural Cultural Heritage Landscape in China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1394, . [CrossRef]

- Pijl, A.; Tosoni, M.; Roder, G.; Sofia, G.; Tarolli, P. Design of Terrace Drainage Networks Using UAV-Based High-Resolution Topographic Data. Water 2019, 11, 8147, . [CrossRef]

- zgeriş, M.; Karahan, F. Agricultural Terraces and Its Characteristics in the Context of Cultural Heritage: An Evaluation on the Case of Uzundere (Erzurum). Milli Folklor. 2022, (133).

- Dalley, S. Ancient Mesopotamian Gardens and the Identification of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon Resolved. Gard. Hist. 1993, 21, . [CrossRef]

- Woods, M.; Woods, M. B. Seven Wonders of the Ancient World; Twenty-First Century Books, 2008.

- Clayton, P. A.; Price, M. The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World; Routledge. ISBN 9780415050364, 2013.

- Avni, G. Terraced Fields, Irrigation Systems and Agricultural Production in Early Islamic Palestine and Jordan: continuity and innovation. Journal of Islamic Archaeology. 2020, 7, 111–137.

- Gibson, S. The archaeology of agricultural terraces in the Mediterranean zone of the southern Levant and the use of the optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating method. Soils and Sediments as Archives of Landscape Change. Geoarchaeology and Landscape Change in the Subtropics and Tropics. 2015, 295-314.

- Pietsch, D.; Mabit, L. Terrace soils in the Yemen Highlands: Using physical, chemical and radiometric data to assess their suitability for agriculture and their vulnerability to degradation. Geoderma 2012, 185-186, 48–60, . [CrossRef]

- Juo, A. S.; Thurow, T. L. Sustainable technologies for use and conservation of steeplands. Food & Fertilizer Technology Center, 1997.

- Wei, W.; Chen, D.; Wang, L.; Daryanto, S.; Chen, L.; Yu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Sun, G.; Feng, T. Global synthesis of the classifications, distributions, benefits and issues of terracing. Earth-Science Rev. 2016, 159, 388–403, . [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, A. New Seven Wonders of the World. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/list/new-seven-wonders-of-the-world, 2018.

- Arnáez, J.; Lana-Renault, N.; Lasanta, T.; Ruiz-Flaño, P.; Castroviejo, J. Effects of farming terraces on hydrological and geomorphological processes. A review. Catena 2015, 128, 122–134, . [CrossRef]

- Bonardi, L. Terraced vineyards in Europe: the historical persistence of highly specialised regions. In World Terraced Landscapes: History, Environment, Quality of Life (pp. 7-25). Springer, Cham.; 2019.

- Cucchiaro, S.; Paliaga, G.; Fallu, D.J.; Pears, B.R.; Walsh, K.; Zhao, P.; Van Oost, K.; Snape, L.; Lang, A.; Brown, A.G.; et al. Volume estimation of soil stored in agricultural terrace systems: A geomorphometric approach. Catena 2021, 207, 105687, . [CrossRef]

- Kizos, T.; Dalaka, A.; Petanidou, T. Farmers’ attitudes and landscape change: evidence from the abandonment of terraced cultivations on Lesvos, Greece. Agric. Hum. Values 2010, 27, 199–212, . [CrossRef]

- Dimakopoulos, S. Agricultural Terraces in Classical and Hellenistic Greece. In LAC 2014 proceedings; 2016.

- Turner, S.; Kinnaird, T.; Varinlioğlu, G.; Şerifoğlu, T. E.; Koparal, E.; Demirciler, V.; Athanasoulis, D.; Ødegård, K.; Crow, J.; Jackson, M.; Bolos, J.; Sánchez-Pardo, J. C.; Carrer, F.; Sanderson, D.; Turner, A. Agricultural terraces in the Mediterranean: medieval intensification revealed by OSL profiling and dating. Antiquity. 2021, 95, 773–790.

- Douglas, T.; Critchley, D.; Park, G. The Deintensification of Terraced Agricultural Land Near Trevelez, Sierra Nevada, Spain. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. Lett. 1996, 5, 258, . [CrossRef]

- Gallart, F.; Llorens, P.; Latron, J. Studying the role of old agricultural terraces on runoff generation in a small Mediterranean mountainous basin. J. Hydrol. 1994, 159, 291–303, . [CrossRef]

- Dunjó, G.; Pardini, G.; Gispert, M. Land use change effects on abandoned terraced soils in a Mediterranean catchment, NE Spain. CATENA 2003, 52, 23–37, . [CrossRef]

- Biddoccu, M.; Zecca, O.; Audisio, C.; Godone, F.; Barmaz, A.; Cavallo, E. Assessment of long-term soil erosion in a mountain vineyard, Aosta Valley (NW Italy). Land Degradation & Development. 2018, 29, 617–629.

- Brandolini, P.; Cevasco, A.; Capolongo, D.; Pepe, G.; Lovergine, F.; Del Monte, M. Response of terraced slopes to a very intense rainfall event and relationships with land abandonment: a case study from Cinque Terre (Italy). Land Degradation & Development. 2018, 29, 630–642.

- Lasanta, T.; Arnáez, J.; Oserín, M.; Ortigosa, L.M. Marginal Lands and Erosion in Terraced Fields in the Mediterranean Mountains. Mt. Res. Dev. 2001, 21, 69–76, . [CrossRef]

- Cammeraat, E.L. Scale dependent thresholds in hydrological and erosion response of a semi-arid catchment in southeast Spain. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 104, 317–332, . [CrossRef]

- Cots-Folch, R.; Martínez-Casasnovas, J.; Ramos, M. Land terracing for new vineyard plantations in the north-eastern Spanish Mediterranean region: Landscape effects of the EU Council Regulation policy for vineyards’ restructuring. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 115, 88–96, . [CrossRef]

- Tarolli, P.; Preti, F.; Romano, N. Terraced landscapes: From an old best practice to a potential hazard for soil degradation due to land abandonment. Anthropocene 2014, 6, 10–25, . [CrossRef]

- Moser, K.F.; Ahn, C.; Noe, G.B. The Influence of Microtopography on Soil Nutrients in Created Mitigation Wetlands. Restor. Ecol. 2009, 17, 641–651, . [CrossRef]

- Damene, S.; Tamene, L.; Vlek, P. L. Performance of Farmland Terraces in Maintaining Soil Fertility: A Case of Lake Maybar Watershed in Wello, Northern Highlands of Ethiopia. Journal of Life Sciences. 2012, 6, 1251–1261.

- Doğan, O. Teraslar ve Gradoni Teras Üzerine Araştırmalar. ÇEM Genel Müdürlüğü, Ankara, Türkiye; 2012.

- Armitage, A.R.; Ho, C.-K.; Madrid, E.N.; Bell, M.T.; Quigg, A. The influence of habitat construction technique on the ecological characteristics of a restored brackish marsh. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 62, 33–42, . [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Errico, A.; Santoro, A.; Dani, A.; Preti, F. Terraced Landscapes and Hydrogeological Risk. Effects of Land Abandonment in Cinque Terre (Italy) during Severe Rainfall Events. Sustainability 2019, 11, 235, . [CrossRef]

- Winzeler, H.E.; Owens, P.R.; Kharel, T.; Ashworth, A.; Libohova, Z. Identification and Delineation of Broad-Base Agricultural Terraces in Flat Landscapes in Northeastern Oklahoma, USA. Land 2023, 12, 486, . [CrossRef]

- Momirski, L.A.; Kladnik, D. The terraced landscape in the Brkini hills. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2015, 55, . [CrossRef]

- Praticò, S.; Solano, F.; Di Fazio, S.; Modica, G. A Multitemporal Fragmentation-Based Approach for a Dynamics Analysis of Agricultural Terraced Systems: The Case Study of Costa Viola Landscape (Southern Italy). Land. 2022, 11(4), 482.Tian, M.; Min, Q.; Lun, F.; Yuan, Z.; Fuller, A.M.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J. Evaluation of Tourism Water Capacity in Agricultural Heritage Sites. Sustainability. 2015, 7, 15548-15569. [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Nie, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhu, D. Advantages and disadvantages of terracing: A comprehensive review. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2021, 9, 344–359, . [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ricketts, T.H.; Kremen, C.; Carney, K.; Swinton, S.M. Ecosystem services and dis-services to agriculture. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 64, 253–260, . [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wei, W.; Daryanto, S.; Tarolli, P. Does terracing enhance soil organic carbon sequestration? A national-scale data analysis in China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 721, 137751, . [CrossRef]

- Collier, M.J. Field Boundary Stone Walls as Exemplars of ‘Novel’ Ecosystems. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 141–150, . [CrossRef]

- Košulič, O.; Michalko, R.; Hula, V. Recent artificial vineyard terraces as a refuge for rare and endangered spiders in a modern agricultural landscape. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 68, 133–142, . [CrossRef]

- Solomou, A.; Proutsos, N.; Keretsos, G.; Tsagkari, K. Impact of Stone Terraces and Walls’ Micro-environment on Biodiversity Conservation: A Case Study in the Mediterranean Island of Kythira-Greece. Proceedings of the 9th International Conferences on HAICTA; 2020.

- Vernikos, N.; Daskalopoulou, S.; Paylogeorgatos, G. Proposal for Classification of Stone Structures. In M. Varte-Matarangas, Katselis Y., ed., The Building Stone in Monuments. Paper presented at the International Interdisciplinary Workshop Scientific Conference ICOMOS – IGME 2001, p. 170- 270. Mytilene, Greece, 2001.

- Arnett, R. Jr,; Thomas M.C.; Skelley, P.E.; Frank, J.H. American Beetles, Volume II: Polyphaga: Scarabaeoidea through Curculionoidea. CRC Press LLC, Boca Raton, FL, 2002.

- Dajoz, R. Les coléoptères carabidés et ténébrionidésmTec & Doc Lavoisier, 2002.

- Fedick, S. L. Prehistoric Maya settlement and land use patterns in the upper Belize River area, Belize, Central America. Arizona State University, USA; 1988.

- Görcelioğlu, E. Ağaçlandırma alanlarında su ve toprak koruma amacıyla kullanılan teraslar ve orman yollarında erozyon kontrolü. Journal of the Faculty of Forestry Istanbul University. 1996, 46, 23–36.

- Erickson, C. L. Intensification, political economy, and the farming community; in defense of a bottom-up perspective of the past, 2006.

- Fischer, G.; Shah, M. M.; Van Velthuizen, H. T.; Nachtergaele, F. O. Global agro-ecological assessment for agriculture in the 21st century. 2001.

- elik, Z. Tarımsal Biyoçeşitliliğin Korunmasında Yerel Tohum Ağları ve Ekolojik Tarımdaki Yeri. Türkiye Ix. Tarım Ekonomisi Kongresi Şanlıurfa, 2010.

- Jacobsen, S.-E.; Sørensen, M.; Pedersen, S.M.; Weiner, J. Feeding the world: genetically modified crops versus agricultural biodiversity. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 651–662, . [CrossRef]

- Dişbudak, K. Avrupa Birliği’nde Tarım-Çevre İlişkisi ve Türkiye’nin Uyumu. T.C. Tarım Ve Köyişleri Bakanlığı, Ankara, Türkiye; 2008.

- Koohafkan, P.; Altieri, M. A. Globally important agricultural heritage systems: a legacy for the future. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2011.

- Koohafkan, P.; Cruz, M. J. D. Conservation and adaptive management of globally important agricultural heritage systems (GIAHS). Journal of Resources and Ecology. 2011, 2, 22–28.

- Koulouri, M. Soil water erosion and land use change in the Mediterranean: abandoning traditional extensive cultivation. Doctoral thesis. Environment Department. University of the Aegean. Mytilene, 2004.

- Lasanta Martínez, T.; Arnáez-Vadillo, J.; Ruiz Flaño, P.; Lana-Renault, N. Agricultural Terraces in The Spanish Mountains: An Abandoned Landscape and A Potential Resource. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles. 2013, 63, 487-491.

- Kladnik, D.; Kruse, A.; Komac, B. Terraced landscapes: an increasingly prominent cultural landscape type. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2017, 57, . [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Qian, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, A. Why are the Longji Terraces in Southwest China maintained well? A conservation mechanism for agricultural landscapes based on agricultural multi-functions developed by multi-stakeholders. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 42–51, . [CrossRef]

- Terkenli, T. S.; Castiglioni, B.; Cisani, M. The challenge of tourism in terraced landscapes. In World terraced landscapes: History, environment, quality of life (pp. 295-309). Springer, Cham.; 2019.

- Zhang, L.; Stewart, W. Sustainable Tourism Development of Landscape Heritage in a Rural Community: A Case Study of Azheke Village at China Hani Rice Terraces. Built Heritage 2017, 1, 37–51, . [CrossRef]

- Bertolino, M.A.; Corrado, F. Rethinking Terraces and Dry-Stone Walls in the Alps for Sustainable Development: The Case of Mombarone/Alto Eporediese in Piedmont Region (Italy). Sustainability 2021, 13, 12122, . [CrossRef]

- WWF. https://www.wwf.org.tr/ne_yapiyoruz/doga_koruma/doal_alanlar/kafkasyaekolojikkoridoru/, 2023.

- Özgeriş, M.; Karahan, F. Use of geopark resource values for a sustainable tourism: a case study from Turkey (Cittaslow Uzundere). Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 23, 4270–4284, . [CrossRef]

- Kopar, İ.; Sevindi, C. Tortum Gölü’nün (Uzundere-Erzurum) Güneybatısında Aktüel Sedimantasyon ve Siltasyona Bağlı Alan-Kıyı Çizgisi Değişimleri. Türk Coğrafya Dergisi. 2013. 60, 49-66.

- Johnson, B.G.; Smith, J.A.; Beeton, J.M. Using a post-glacial terrace sequence to better understand landscape evolution and paleohydrology in the eastern San Juan Mountains, USA. Geomorphology 2023, 429, . [CrossRef]

- Tipping, R.; Kinnaird, T.C.; Dingwall, K.; Ross, I. Some geomorphological implications of recent archaeological investigations on river terraces of the River Dee, Aberdeenshire. Scott. J. Geol. 2023, 59, . [CrossRef]

- GDM. Republic of Turkey Ministry of National Defence General Directorate of Mapping; HGM KURE application https://kure.harita.gov.tr/; 2023.

- GDGIS. Republic of Turkey Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change, Directorate General of Geographic İnformation Systems; ATLAS web application https://basic.atlas.gov.tr/?_appToken=&metadataId=; 2023.

- Scaramellini, G. Il Paesaggio agrario e il paesaggio culturale dei terrazzamenti artificiali nelle Alpi, in Trischitta D. (a cura di), Il paesaggio terrazzato. Un patrimonio geografico, antropologico, architettonico, agrario, ambientale, Città del Sole Edizioni, Reggio Calabria, pp. 101-141; 2005.

- Agnoletti, M.; Cargnello, G.; Gardin, L.; Santoro, A.; Bazzoffi, P.; Sansone, L.; Pezza, L.; Belfiore, N. Traditional landscape and rural development: comparative study in three terraced areas in northern, central and southern Italy to evaluate the efficacy of GAEC standard 4.4 of cross compliance. Ital. J. Agron. 2010, e 6(s1): e16, 121–139. [CrossRef]

- Varotto, M.; Ferrarese, F. Mapping and geographical classification of terraced landscapes: problems and proposals. Terraced landscapes of the Alps-ATLAS (eds) by Guglielmo Scaramellini and Mauro Varotto. https://www.alpter.net/IMG/pdf/ALPTER_Atlas_ENG_small.pdf; 2008.

- UNESCO. Art of dry stone walling, knowledge and techniques. https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/art-ofdry-stone-walling-knowledge-and-techniques-01393; 2023.

- Yilmaz Karaman, Ö.; Tanaç Zeren, M. Importance and Deterioration Prob-lems of Wooden Suppor-ting Elements within The Masonry System of Traditional Turkish Houses. Dokuz Eylul Unıversity Fa-culty of Engineering, Journal of Scien-ce and Engineering. 2010, 12 (2): 75-87.

- Koulouri, M.; Giourga, C. Land abandonment and slope gradient as key factors of soil erosion in Mediterranean terraced lands. Catena 2007, 69, 274–281, doi:10.1016/j.catena.2006.07.001.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).