1. Introduction

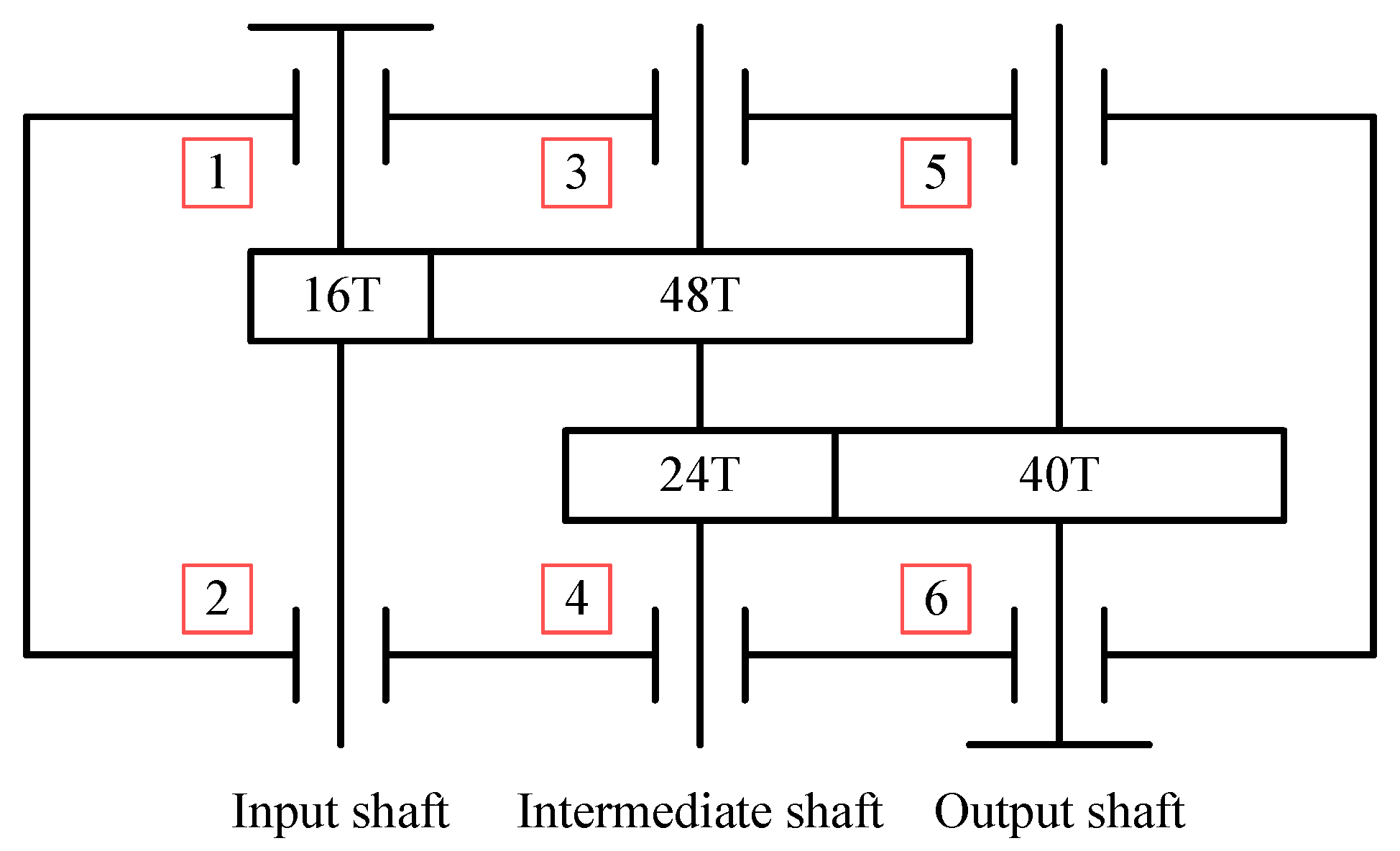

Gearboxes are one of the most widely used speed and power transfer elements in rotating machinery and play a vital role in manufacturing. Gearboxes contain gears, rolling bearings, drive shafts, and other components, which usually operate under harsh operating conditions with different speeds and loads and are prone to failures. And gearbox failure may lead to unexpected downtime, causing substantial economic losses and significant casualties. Therefore, it is essential to study gearbox fault diagnosis to ensure the efficient operation of mechanical systems [

1].

Generally speaking, gears and bearings are the two components in gearboxes that are most prone to failure. Common failures include broken teeth, tooth surface wear, bearing fatigue spalling, and running wear [

2]. And the loss of one component often causes the failure of another element in contact with it, triggering a compound failure. In the practical application of gearboxes, the features of solid faults easily cover the information of weak fault features due to the different damage mechanisms and loss degrees of individual defects embedded in the vibration signals [

3]. Together with the complex transmission path of the movement, the vibration effects generated by different faults will interact, making the coupling and modulation phenomenon between the signals more severe and the mark features challenging to extract.

Traditional composite fault diagnosis methods usually use signal processing techniques such as wavelet transform analysis [

4], resonance demodulation [

5], and empirical modal decomposition [

6,

7] for feature extraction, and then shallow machine learning models such as BP neural networks [

8] and support vector machines [

9] for fault classification. Although the traditional methods have achieved fruitful results, the following drawbacks still exist in the era of big data [

10]: 1) the process of feature extraction and selection using signal processing techniques is complex, requires manual operations, and relies mainly on engineering experience; 2) manual feature extraction reduces the complexity of the input data and causes rich fault state information to be lost in the original data; 3) the traditional signal feature extraction techniques make it difficult to separate the coupled features of compound faults.

Deep learning has been widely used in fault diagnosis, driven by artificial intelligence technology in recent years. Compared with traditional diagnosis methods, deep learning-based fault diagnosis methods are free from the reliance on expert knowledge and signal pre-processing methods, can directly excavate the composite fault features hidden in the original vibration signal, and have obvious advantages in the face of massive data. The convolutional neural network (CNN) is the most widely used among them. This is due to its features, such as local connectivity, weight sharing, and pooling operations, that can effectively reduce the number of training parameters, have strong robustness, and are easy to train and optimize. Yao et al. [

11] proposed a CNN-based composite fault diagnosis method that converts bearing vibration signals into grayscale maps as training samples for the network, which can effectively identify bearing hybrid faults in urban rail trains. Zhang et al. [

12] considered a deep convolutional generative adversarial network model under insufficient diagnostic samples and effectively improved the composite fault diagnosis by generating additional composite fault data samples. Sun et al. [

13] combined an improved particle swarm-optimized variational modal decomposition with CNN to achieve mixed fault diagnosis of planetary gearboxes. Although the above methods achieved good results, each channel contains different information learned by the convolutional kernel for the features extracted by CNN. The traditional CNN gives the same weight to each track, ignoring the importance of the elements contained in different channels for the fault diagnosis task.

The attention mechanism considers the weight effect, i.e., the mapping relationship between input and output, which can enhance the key features and weaken the redundant components [

14,

15]. Therefore, introducing the attention mechanism into the diagnostic model can improve the effectiveness and reliability of the method. Li et al. [

16] designed a fusion strategy based on the channel attention mechanism to obtain more fault-related information when fusing multi-sensor data features. Xie et al. [

17] constructed an improved CNN incorporating the channel attention mechanism for fault diagnosis of diesel engine systems. The model mentioned above, considering feature weights, achieves good results, but scalar neurons reduce specific parameters such as location and scale in the feature mapping of their subject network CNN. Therefore, the fully connected layer requires a large amount of data to estimate the parameters of the features, and the demand for memory, computation, and data volume is enormous [

18]. On the other hand, the pooling layer of the CNN gives the model a prior probability that is not affected b the translation but loses specific spatial information. In other words, CNNs obtain invariance rather than covariance [

19].

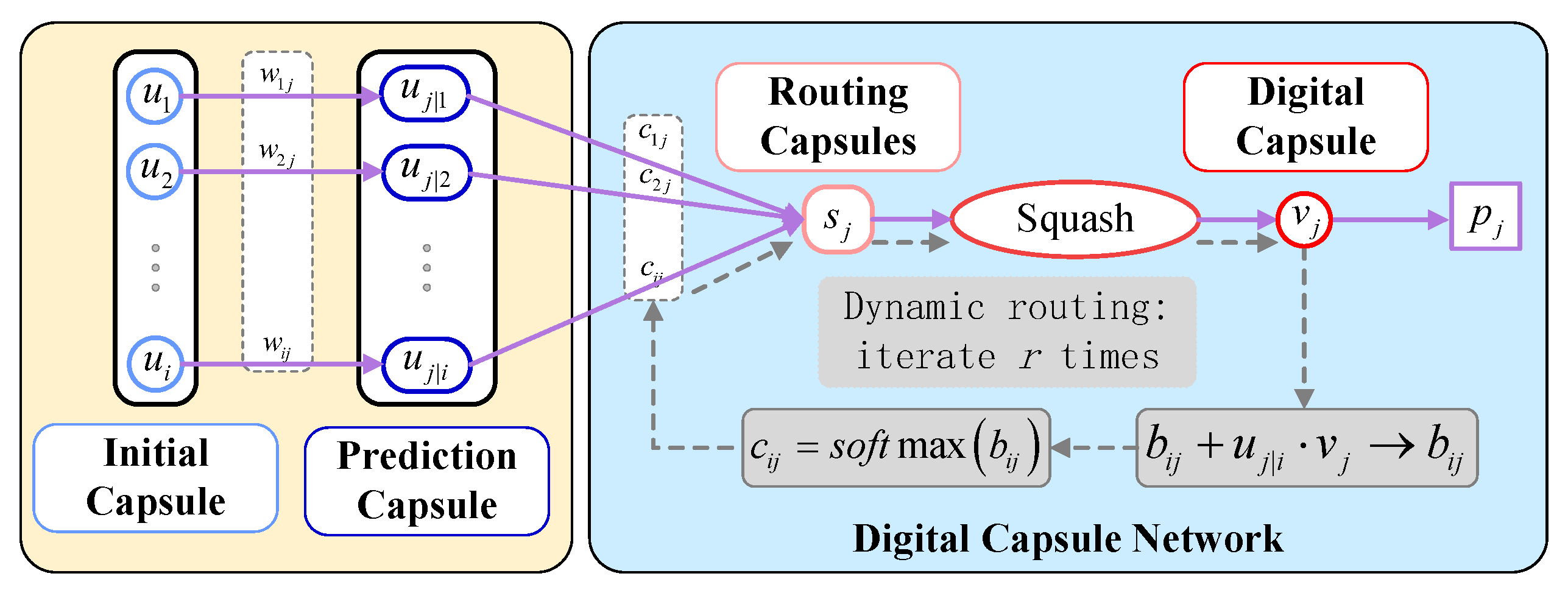

In 2017, Sabour et al. [

19] proposed a capsule neural network, which uses vectors to describe the object representation, where each set of neurons forms a capsule, and the capsule layer outputs vectors, with the vector length indicating the probability of the object presentation; the vector direction means the instantiation parameter. In mechanical fault diagnosis applications, multidimensional capsules can retain specific feature parameters at different rotational speeds. In addition, the capsule's distance represents the features' dispersion, so the capsule network's classification quality is better than traditional neural networks. Zhang et al. [

20] combined wavelet transform and capsule network for bearing fault diagnosis in high-speed trains. Ke et al. [

21] proposed an improved capsule network for the problem of insignificant composite fault features in modular multilevel converters.

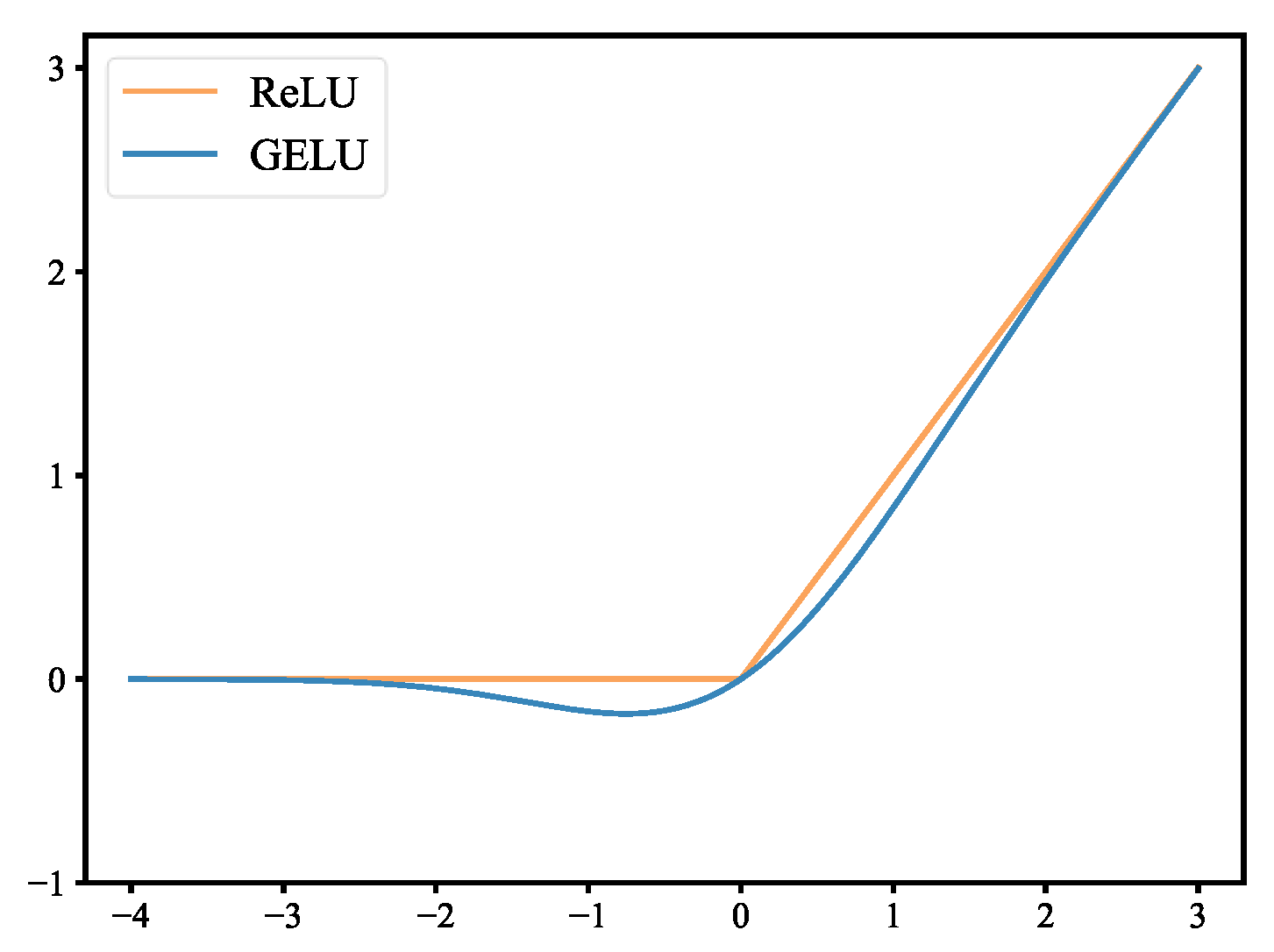

The studies mentioned above only diagnose compound faults occurring in a single component, while in actual production, compound faults are usually coupled by multiple component faults in the transmission system. Therefore, an efficient channel attention capsule network is proposed for the problem of multi-component composite fault diagnosis in gearbox drive systems at different speeds. The method uses a one-dimensional convolutional neural network to extract composite fault features, introduces an efficient channel attention module to assign weights to the channel features, and performs composite fault classification by the capsule network. The main contributions of this paper are as follows: 1) ECA-CN discards the pooling layer in traditional CNN and introduces a capsule network instead, using a dynamic routing algorithm instead of pooling operation to ensure that the core features are not lost; 2) the activation function of ECA-CN is selected using GELU instead of the commonly used ReLU to accelerate the network convergence and effectively improve the robustness of the model; 3) the method does not require a time-consuming manual feature extraction process, and can achieve end-to-end gearbox composite fault diagnosis at different speeds.

3. Fault diagnosis method based on efficient channel attention capsule network

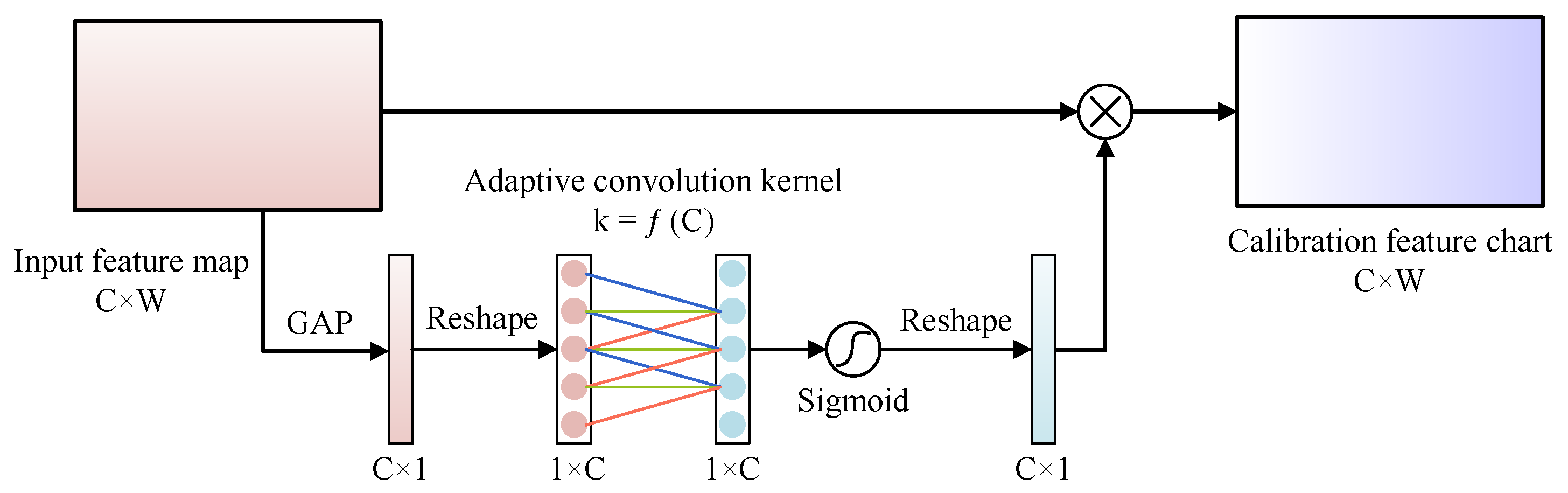

3.1. Efficient channel attention module

Efficient channel attention (ECA) [

24] is a lightweight, plug-and-play attention module with good generalization capability to improve the performance of CNN architectures. The ECA module is processed as shown in

Figure 3, given an input feature map

, of size

, where

is the number of channels and

is the width. Figure. 3 The schematic diagram of the efficient channel attention module.

Step 1: Aggregate the spatial information using global average pooling (GAP) to obtain the spatial information description vector

:

Step 2: The

is deformed and processed by one-dimensional convolution to achieve local cross-channel information interaction, and then the channel attention weight

is obtained by the Sigmoid activation function. Where the size of the convolution kernel is adaptively selected according to the number of channels in the input feature map, calculated as follows:

where both are constants,

and

.

indicates that the nearest odd number

is taken.

Step 3: Multiply the

deformation with

to get the feature map

corrected by channel attention.

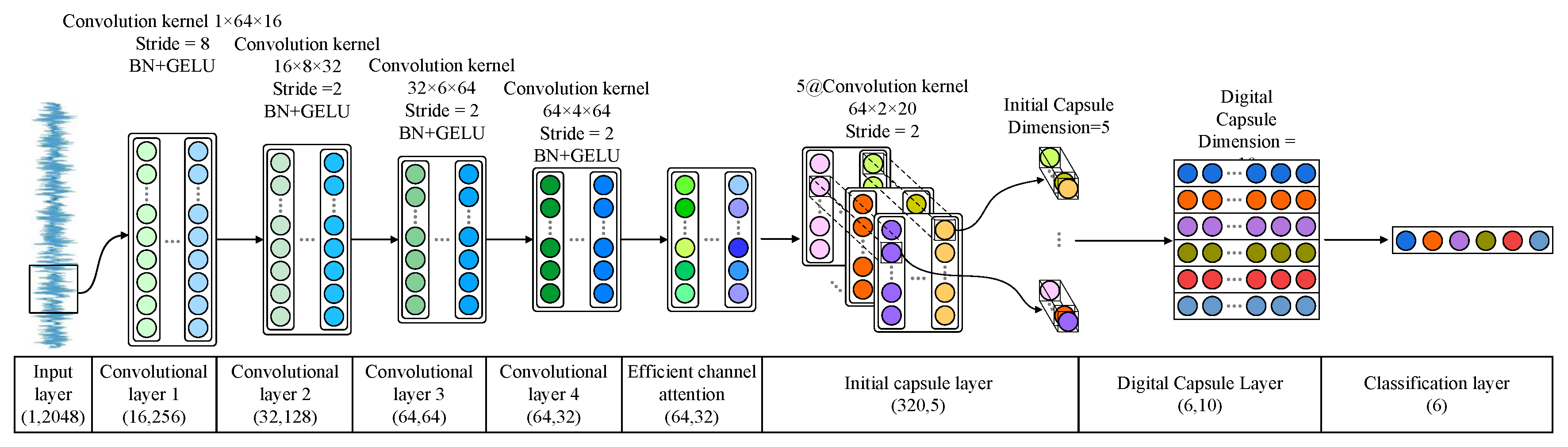

3.2. Efficient channel attention capsule network

The architecture of the efficient channel attention capsule network constructed in this paper is shown in

Figure 4, which mainly includes the input layer, convolutional layer, ECA module, initial capsule layer, digital capsule layer, and classification layer. The network processing process is as follows:

1) The vibration signal sample

is input from the input layer, and the fault feature

is finally obtained using one-dimensional convolutional step-by-step feature extraction. It is worth noting that the method uses wide convolutional kernels in convolutional layer 1, which can extract global features and reduce the effect of noise. And the kernel size of the subsequent convolutional layers is chosen as narrow convolutional kernels that become progressively smaller as the network level deepens, which can fully exploit the local features.

2) The ECA module assigns weights to the features of different channels in

and obtains the attention-corrected feature map

. Channel attention can enhance critical fault information, suppress useless information, and solve the feature redundancy problem.

3) In the initial capsule layer, five groups of convolution are performed on , which features can be further extracted. After convolution, the scalar values in the feature matrix are spliced to construct 320 initial capsules with a capsule dimension of 5. For the initial capsules, the spatial relationship is represented by each corresponding capsule because of the large number of pills. Since the initial and digital tablets are weighted mapping relationships, the number of digital capsules decreases, but the fault information embedded in each capsule increases. In the digital capsule layer, the dynamic routing algorithm is used to calculate the correlation between the initial capsule and the digital capsule, update the weights, complete the conversion between the pills to realize the accurate categorization of fault information, and finally generate six digital tablets with a capsule dimension of 10.

4) Calculate the two-parametric number of digital capsules to obtain the probability of different gearbox health states as in equation (11).

In this paper, compared with the traditional CNN fault diagnosis method, firstly, GELU is used as the activation function to introduce a nonlinear transformation to the network while adding random regularization, which makes the network converge faster and more robust. Secondly, the efficient channel attention module is introduced, which can assign weights to different fault information learned by the network, highlighting the fault information that plays a vital role in the diagnosis decision and suppressing the useless and harmful information, effectively solving the feature redundancy problem. Finally, the traditional pooling layer is discarded in favor of a capsule network using a dynamic routing algorithm. It thoroughly explores the fault features and maximally preserves their spatial information through vector neurons to obtain better fault diagnosis performance than the traditional CNN.

3.3. Fault diagnosis process

In this paper, CNN, ECA, and CN are combined to build a deep learning network that can be used for compound fault diagnosis of gearboxes under different speed conditions, and its diagnosis process is shown in

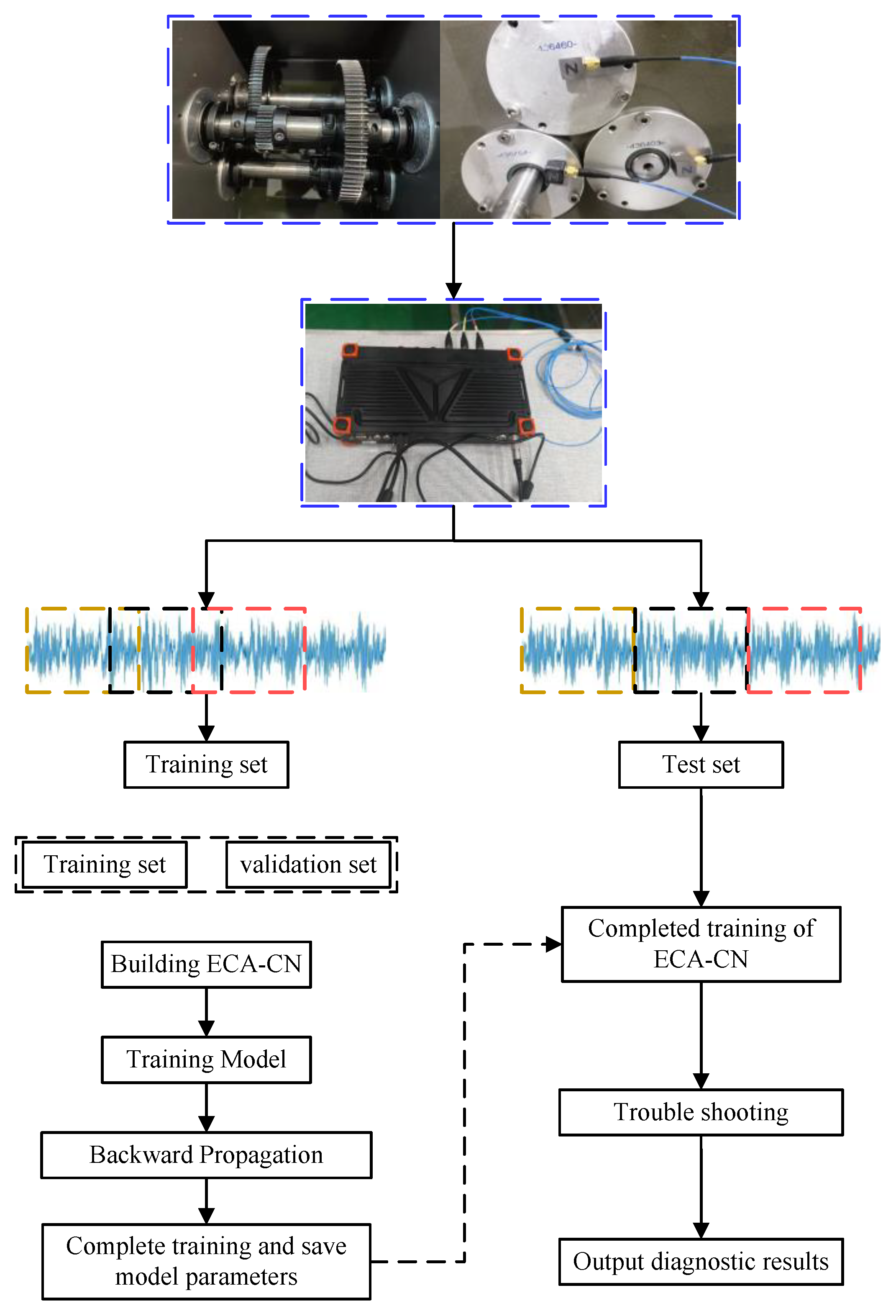

Figure 5. The specific diagnosis steps are as follows:

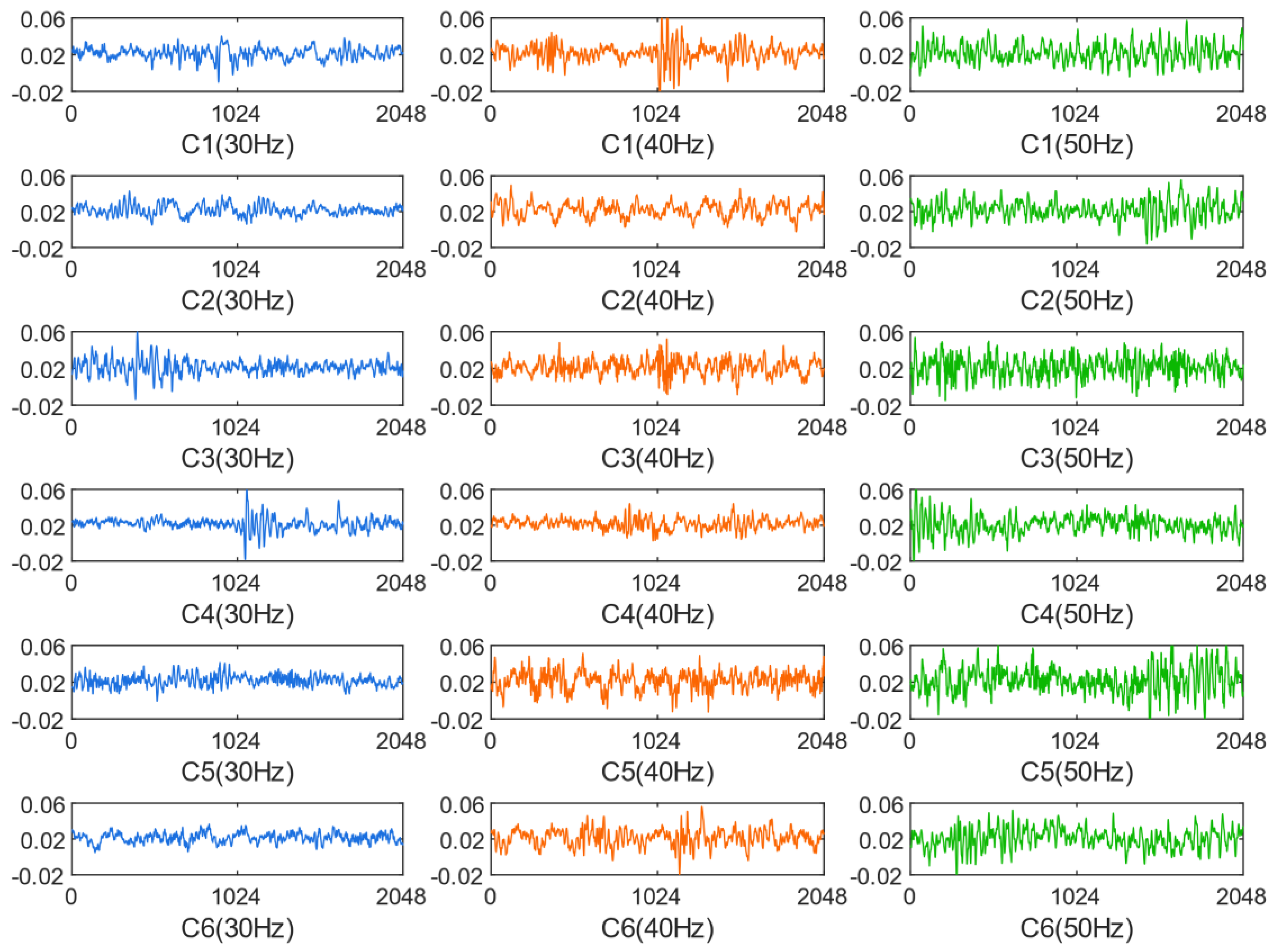

1) Collect the vibration data of the gearbox at different rotational speeds using acceleration sensors.

2) Overlap sampling of vibration data is performed to obtain the training set. The leave-out method randomly divides the training set into a new training set and a validation set. To prevent the information leakage of the test set, the vibration data are routinely window sampled to obtain the test set.

3) Construct the ECA-CN model and initialize the parameters.

4) Train the model using the training set, select the optimal model based on the validation set, and save the model parameters.

5) Evaluate the final model using the test set and derive the diagnosis results.

5. Conclusion

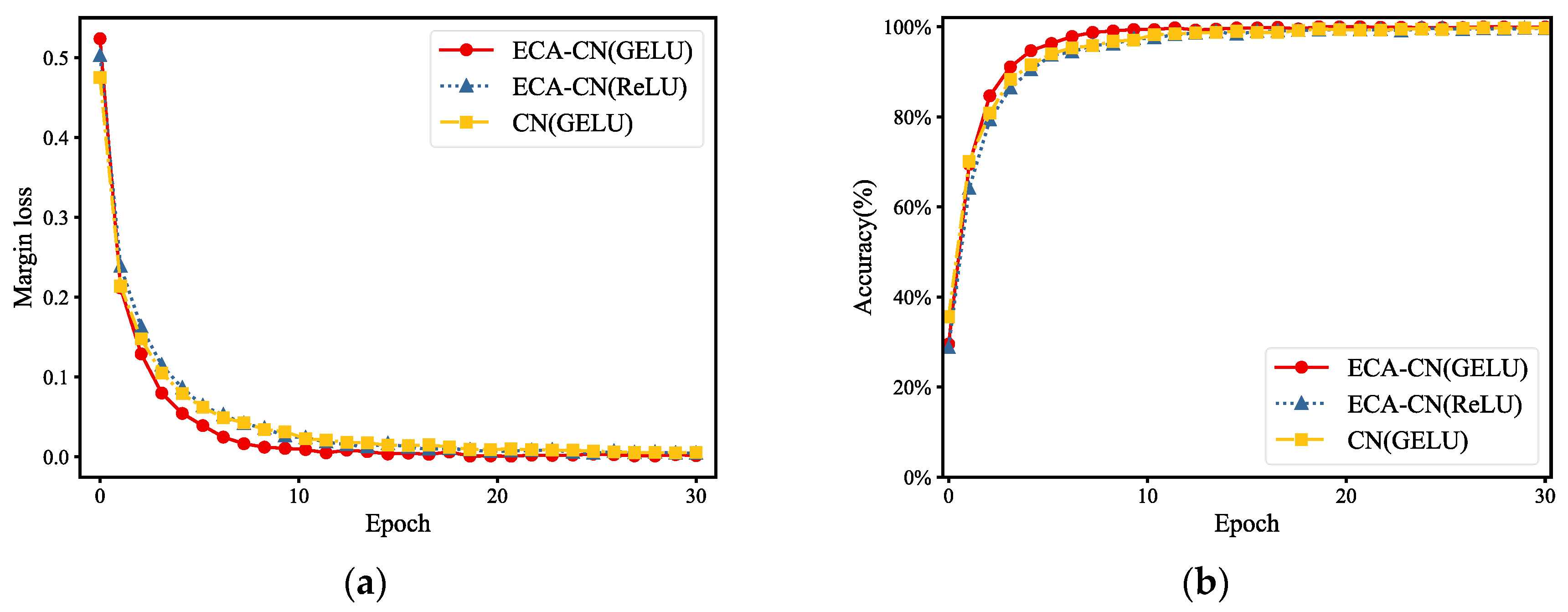

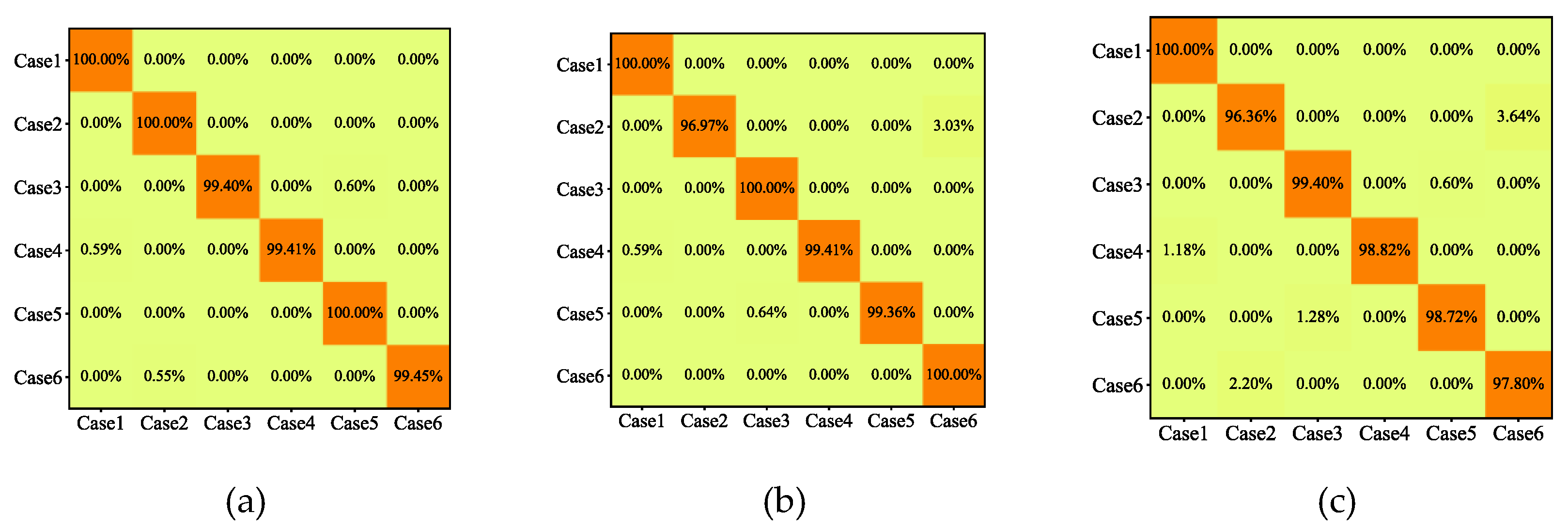

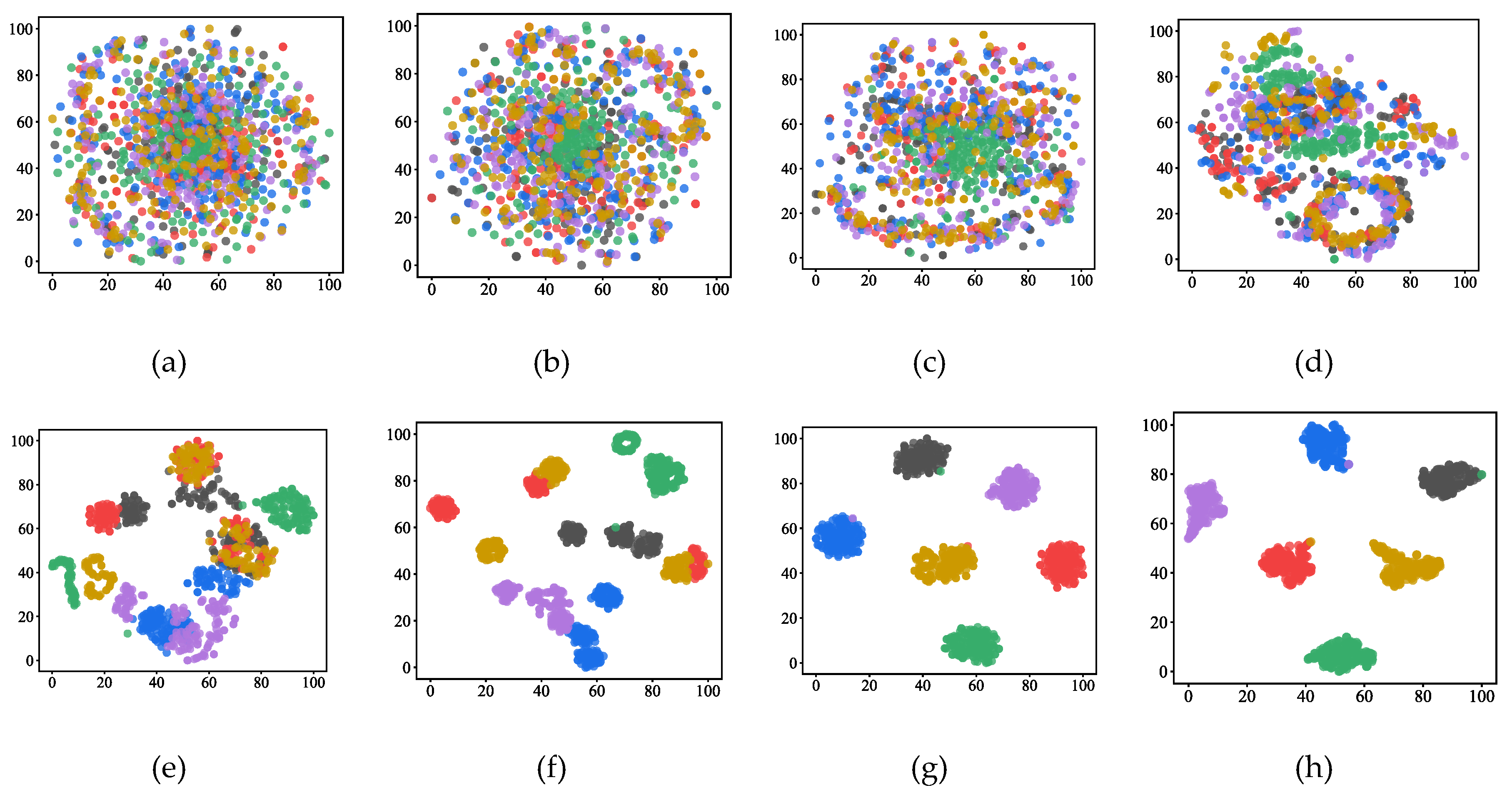

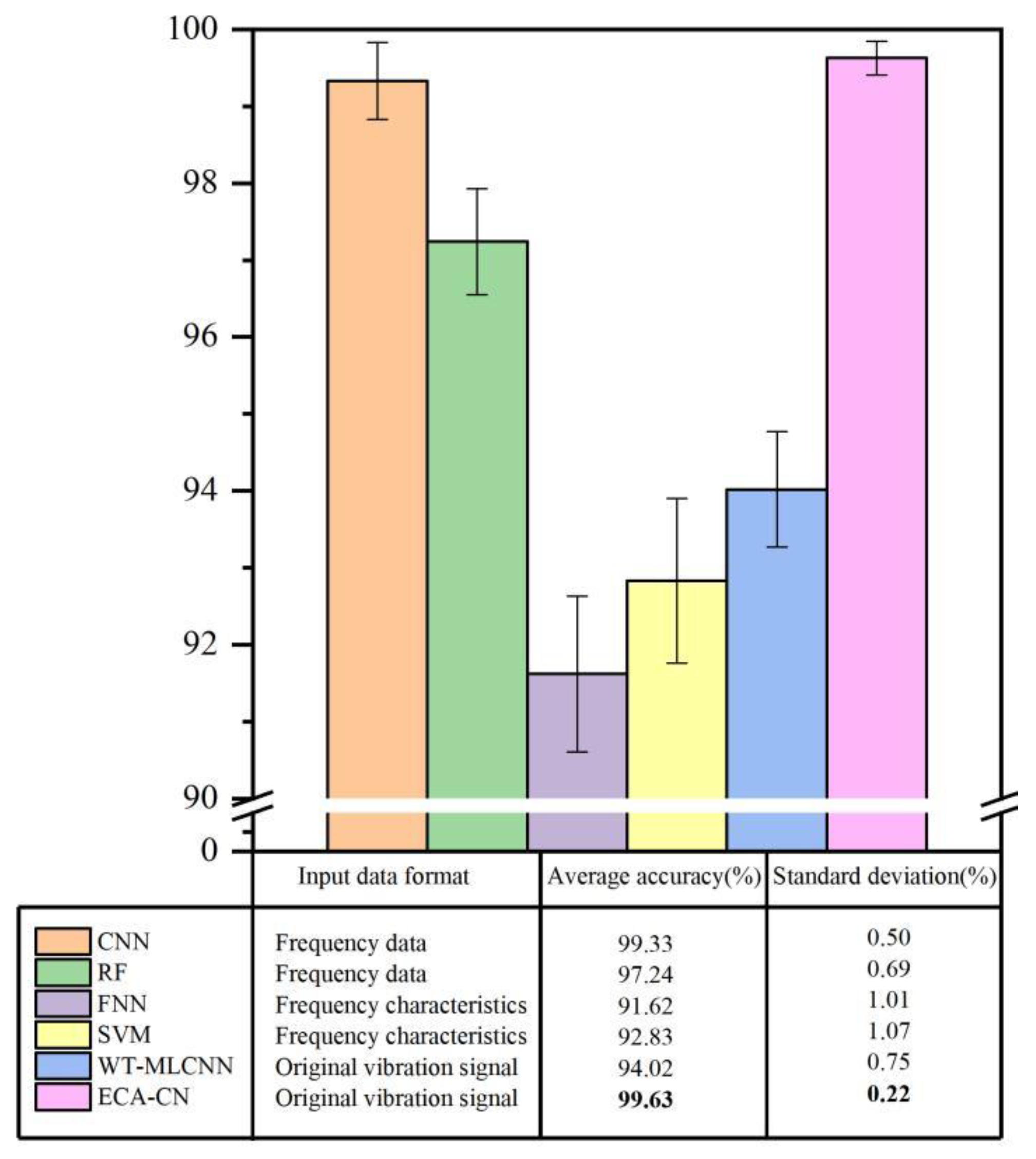

This paper proposes an intelligent diagnosis model with an efficient channel attention capsule network for compound fault diagnosis of gearboxes at different speeds, which can realize "end-to-end" intellectual fault diagnosis from raw vibration data to fault identification. The method uses a deep convolutional neural network to extract fault features, introduce s ECA module for feature filtering, and use a capsule network to retain the spatial information of features, which can achieve accurate fault diagnosis. The effectiveness and superiority of the method are verified using the 2009 PHM Challenge gearbox dataset: 1) the ECA-CN model uses GELU as the activation function, and the experimental results show that the ECA-CN (GELU) converges faster and is more robust than the ECA-CN (ReLU); 2) the ECA-CN model introduces the ECA module, and the experimental results show that the CN has an accuracy of 99.70%, while the accuracy of CN without the attention module is 98.68%, indicating that the ECA module can effectively improve the fault diagnosis accuracy of the model; 3) Compared with the shallow machine learning model and the traditional CNN model, the average accuracy of ECA-CN is improved by 4.62%, and the standard deviation is reduced by 0.58%, showing a more competitive fault diagnosis performance, which can achieve compound fault diagnosis of gearboxes at different rotational speeds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z., H.J. and Q.X.; methodology, X.Z. and Q.X.; software, Q.X.; validation, X.Z. and Q.X.; formal analysis, H.J. and J.L; investigation, X.Z.; resources, X.Z.; data curation, Q.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.Z., Q.X., H.J. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.