1. Introduction

Einstein established the famous theory of special relativity in 1905, which laid the foundation for the relativistic view of spacetime. Based on his deep thinking about special relativity, Einstein established the theory of general relativity (GR) in 1915. GR is considered one of the most elegant theories in the field of physics, and has received significant experimental support. For example: (1) General relativity passed rigorous tests within the solar system; (2) Its applications in cosmology have also been extremely successful; (3) The detection of gravitational waves by the advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in 2015 provided strong support for the theoretical predictions made by GR 100 years ago [

1]; (4) The fact that the Event Horizon Telescope [

2] discovered the existence of supermassive black holes in the center of the Milky Way galaxy in 2019 greatly enhanced interest and confidence for us in the research of general relativity theory. However, it is also evident that many problems and challenges remain in the study of gravitational physics, such as the problem of gravitational quantization, the nature of dark energy, the problem of inflationary universe and the problem of space-time singularity, etc. To address these issues, many modified gravity theories have been developed and discussed, such as f (R) theory [

3,

4], f (T) theory [

5,

6], f (R, T) theory [

7], and f (G) theory [

8], among others. The exploration of modified theories of gravity remain a hot topic in current research of gravitational physics. As one type of modified gravity theory, the Generalized Brans-Dicke (GBD) theory has been studied in cosmology, gravitational wave physics, and other fields [

9,

10,

11]. In this paper we will explore some issues in the framework of GBD theory.

Black hole (BH) is one of the important prediction of general relativity. After years of observation and exploration, people finally captured the first image of a BH in 2019 through the Event Horizon Telescope. For many years, the research on BH physics has attracted the attention of lots of physicists and astronomers. Different types of black holes, such as static BHs [

12], dynamic BHs [

13], spherically symmetric BHs [

14], axially symmetric BHs [

15], and exotic BHs [

16], have been intensively discussed. The study of the thermodynamic laws of BHs areas suggests that black holes, as special celestial bodies, seem to have thermal properties. It is well known that thermal properties of BHs under different types has been widely explored. The research on the corrected BH entropy is a hot topic in BH thermodynamics, and some studies on the correction of black hole entropy under modified gravity theory have been investigated, such as conformal field theory [

17,

18], string theory [

19,

20], and others. This article mainly explore the relevant properties of thermodynamic correction entropy of static spherically symmetric BHs within the framework of GBD modified gravity theory. Additionally, the stability analysis of the geodesic motion of particles around a BH is an important research topic in the field of gravitational physics, which plays a vital role in exploring the properties of black holes and gravity. Under different contexts of BH, people have conducted extensive research on the stability of black holes through the application of geodesic deviation equation, such as charged black holes in f (T) theory [

21], rotating (anti-) de-Sitter black holes in f (R) theory [

22], and non-trivial black holes [

23], etc [

24,

25,

26,

27]. In this paper, we also discuss the stability of the geodesic motion of particles around black holes in the GBD gravity theory.

The structure of our paper is as follows. The first section is an introduction. In the second part of this paper, we focus on the correction of thermodynamic entropy of a static spherically symmetric BH within the framework of GBD modified gravity theory. We analyse the stability of geodesic motion of particles in black holes in the third section. The fourth part is the conclusion of this article.

2.

We first briefly introduce the GBD theory, whose action is written as [

9]:

Here,

denotes the Brans-Dicke scalar field,

is the coupling constant,

represents Lagrange density of matter field. By applying the variational principle, the gravitational field equation and scalar field equation of GBD theory can be derived as follows:

We consider a specific parametric model[

28,

29]:

and

. Under background of the spherically symmetric space-time line elements:

with

, the solution of the field equation can be calculated when

where

and

are two constant parameters. Obviously, expression (

5) is similar in form to the Reissner-Nordstrom solution for charged celestial bodies in Einstein’s general relativity (if the integration constants are set to:

,

, then the two solutions are the same in form). Therefore, in the subsequent discussion,we consider that the values of these two parameters satisfy:

and

.

The study of black hole thermodynamics and entropy correction has always been an important issue in the gravitational physics. Next, we investigate the corrected entropy of spherically symmetric BH in the framework of GBD theory. Consider the partition function in the form [

30]:

where

is the temperature in units of the Boltzmann constant

.

is the density of state, which can be given from (

6) by performing the inverse Laplace transform (keeping

E fixed) [

31,

32]:

In Eq. (

7), the exact entropy as a function of temperature (not just at equilibrium) can be written as[

33]

It is formally defined as the sum of entropies of subsystems of the thermodynamic system, which are small enough to be themselves in equilibrium [

33]. Considering the method of steepest descent around the saddle point:

, we have

with

being the equilibrium temperature. On the other hand, we can receive the following form of entropy function by expanding it about

,

Then Eq.(

9) can be simplified as

with

where

represents the entropy at any temperature, and

is the entropy calculated by the Beckenstein-Hawking area law. As can be seen from Equation(

9), the correction of entropy is only described by the term of

. Using Equation(

8), it can be deduced that

Consider the energy of a canonical ensemble [

33]:

Then we have:

here

C is the heat capacity. So, we finally get

Applying it to a thermodynamic system of BH, the saddle point is represented as

by taking Hawking temperature

instead of

T. Following the method used in reference[

34], the entropy can be rewritten by introducing a parameter

to track the correction term

For GBD modified gravity theory,

can be derived as follows

Comparing the spherically symmetric BH solution(

5) under this theory with the Schwarzschild BH solution in the GR theory, the integration constant

can be easily expressed as

, namely.

Using equations(

19) and (

20), we can derive:

Let

, expression of the event horizon radius can be written as

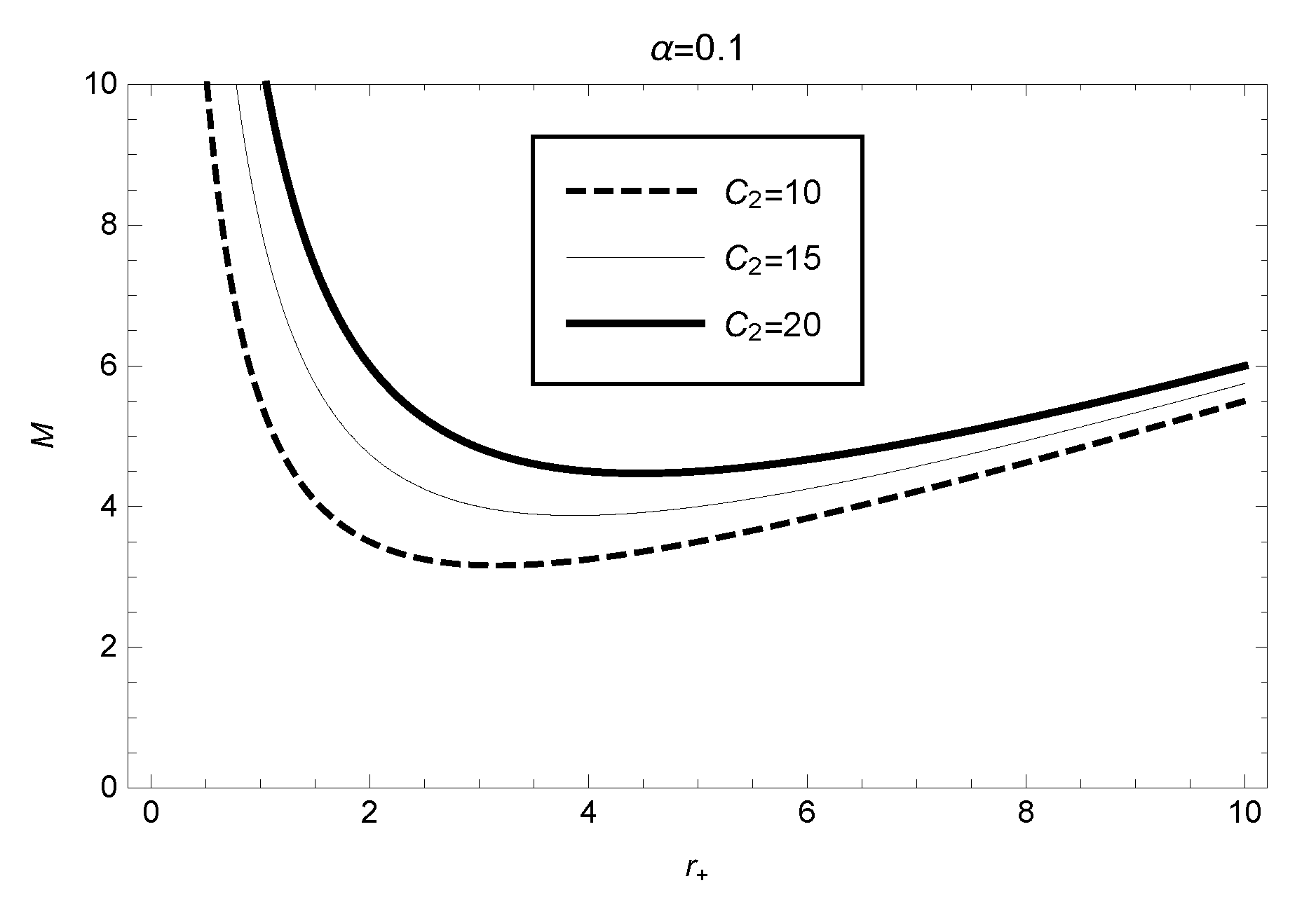

Obviously, the relationship between the BH mass and the event horizon radius in GBD theory meets

Using expression (

23), we draw the picture of the black hole mass relative to the event horizon radius for different parameter values

, as shown in

Figure 1. From

Figure 1, we observe that for the case

, the black hole mass reaches the minimum value

when the event horizon radius is

.

Combining Eqs. (

21) and(

23), we obtain

Then we can get the concrete expressions of temperature and heat capacity for the GBD black hole as follows:

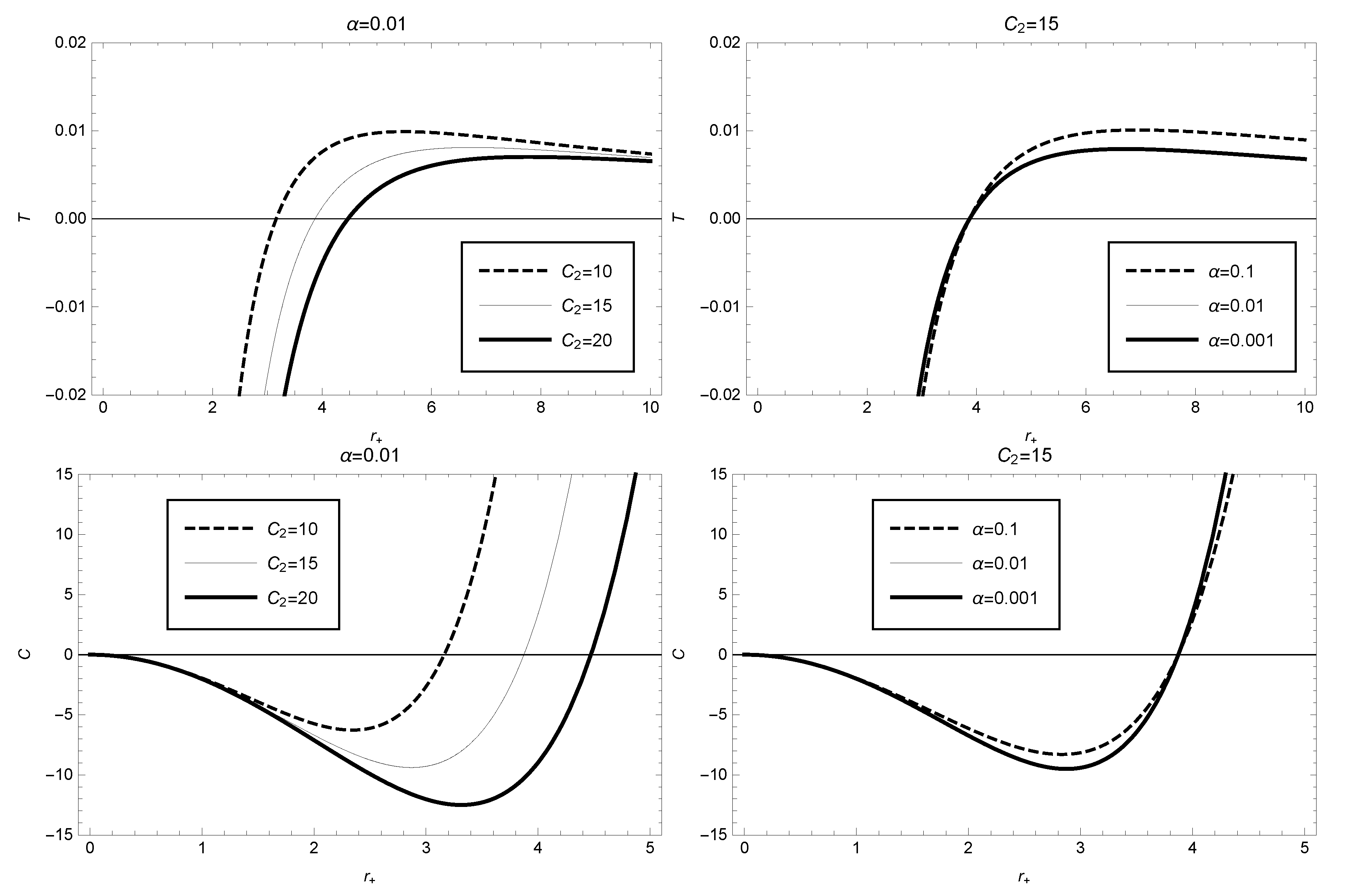

According to these expressions, we plot the variation of BH temperature (upper graph) and heat capacity (lower graph) with respect to the event horizon radius in

Figure 2. From

Figure 2 (upper), we observe that the BH temperature is positive only within a specific range of the event horizon radius. For instance, for the parameter values

and

, the BH temperature is positive when

; whereas for

, it corresponds to a physically meaningless negative temperature region. Moreover, the black hole temperature reaches its maximum value when the event horizon radius is

. The lower graph of

Figure 2 shows that the black hole undergoes a phase transition in the framework of GBD modified gravity theory, and the location of the phase transition depends on the model parameter values. For example, for

and

, the black hole is in an unstable phase with negative heat capacity in the range

, and the heat capacity of BH has its minimum value at the event horizon radius

; On the other hand, for the range

, the black hole is in a stable phase with positive heat capacity. Clearly, the black hole undergoes a phase transition at

, where the BH heat capacity

.

By combining equations(

18),(

25) and (

26), we can derive the corrected entropy expression for black holes under GBD theory, given by:

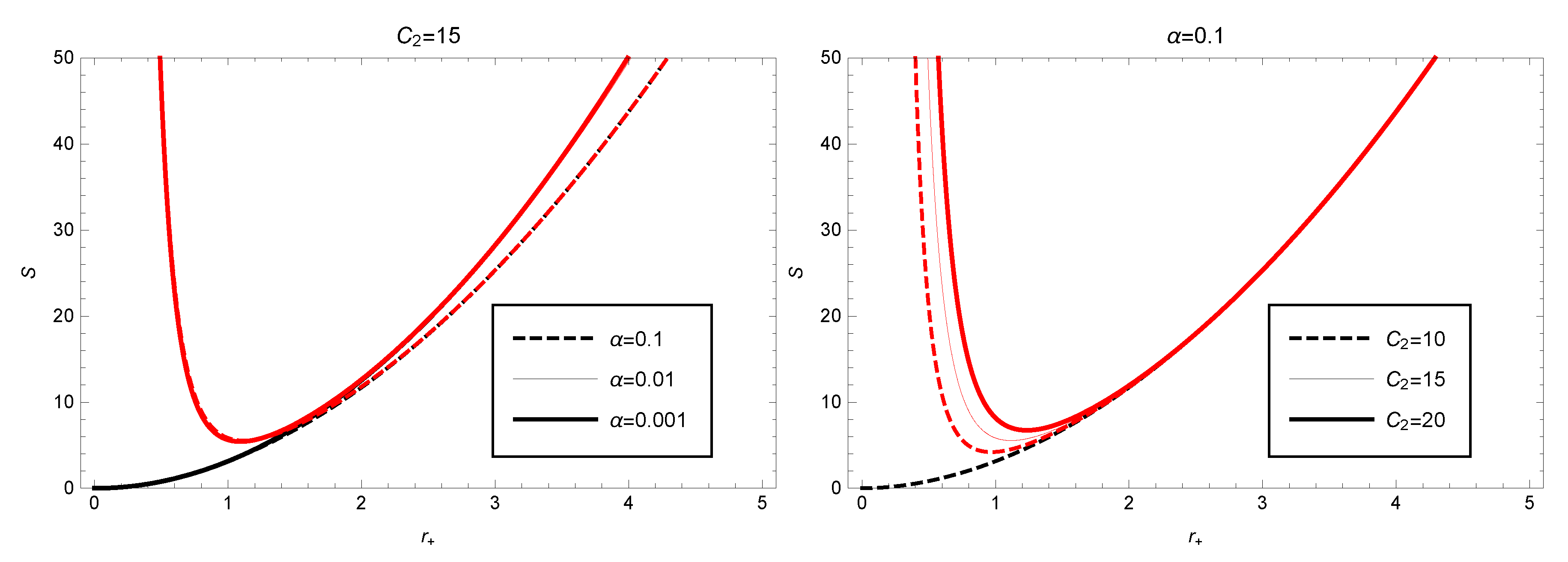

Taking the parameters

,

and

into account, we can use equation (

27) to plot the corrected entropy as a function of the event horizon radius (as shown in

Figure 3). From

Figure 3, we observe that the entropy

S with the correction term decreases rapidly with increasing event horizon radius and reaches its minimum value

at

, then gradually increases. The plot of

indicates that it increases monotonically with

increasing. Comparing the two plots of

S and

, we find that the correction term has a significant effect mainly in the region of small values

, and the entropy-increasing effect is very prominent. As for large values

, the effect of the correction term can be almost ignored (the two curves almost overlap). In addition, we also calculate the influence of other model parameter values on the entropy. From

Figure 3 (left), we can see that the variation of the model parameter

has little effect on the corrected entropy when

is large.

3.

In this section, we analyze the motion of particles and their properties around black holes in the GBD theoretical framework. The motion of a free particle in a gravitational field is described by the geodesic equation:

Here,

p represents the orbital parameter. The component forms of geodesic equation can be written as

Where the prime represents the derivative with respect to the radial coordinate

r. For a gravitational field with spherical symmetry, without loss of generality, we select the initial position and velocity of the particle to be on the equatorial plane, i.e.,

and

. Using equation (

31), we obtain

, which indicates that the particle motion will always remain on the equatorial plane. For particles with non-zero rest mass, the orbital parameter is taken to be the proper time

. Further derivation leads to two equations for the motion of particles in a gravitational field:

Here

E and

J are two constants of integration, representing the energy and angular momentum of a unit mass particle. Additionally, using the normalization condition of the four-velocity

and equations (

33) and (

34), we obtain:

We define the effective potential as:

Then equation (

35) becomes:

Clearly, the properties of the gravitational potential in the GBD theory can be described by equation (

36), which depends on the relative position and angular momentum of the particles. Combining equations (

5) and (

36), we see that when the radius is

, the effective potential is

. Furthermore, equation (

37) indicates that when

, i.e.,

, the orbital radius

r is constant, and the trajectory of particle is circular.

In black hole physics, it is meaningful to discuss the innermost stable circular orbit (ISCO). The ISCO is determined by the following expressions:

Therefore, for the GBD theory, we derive the relationship that the ISCO needs to satisfy:

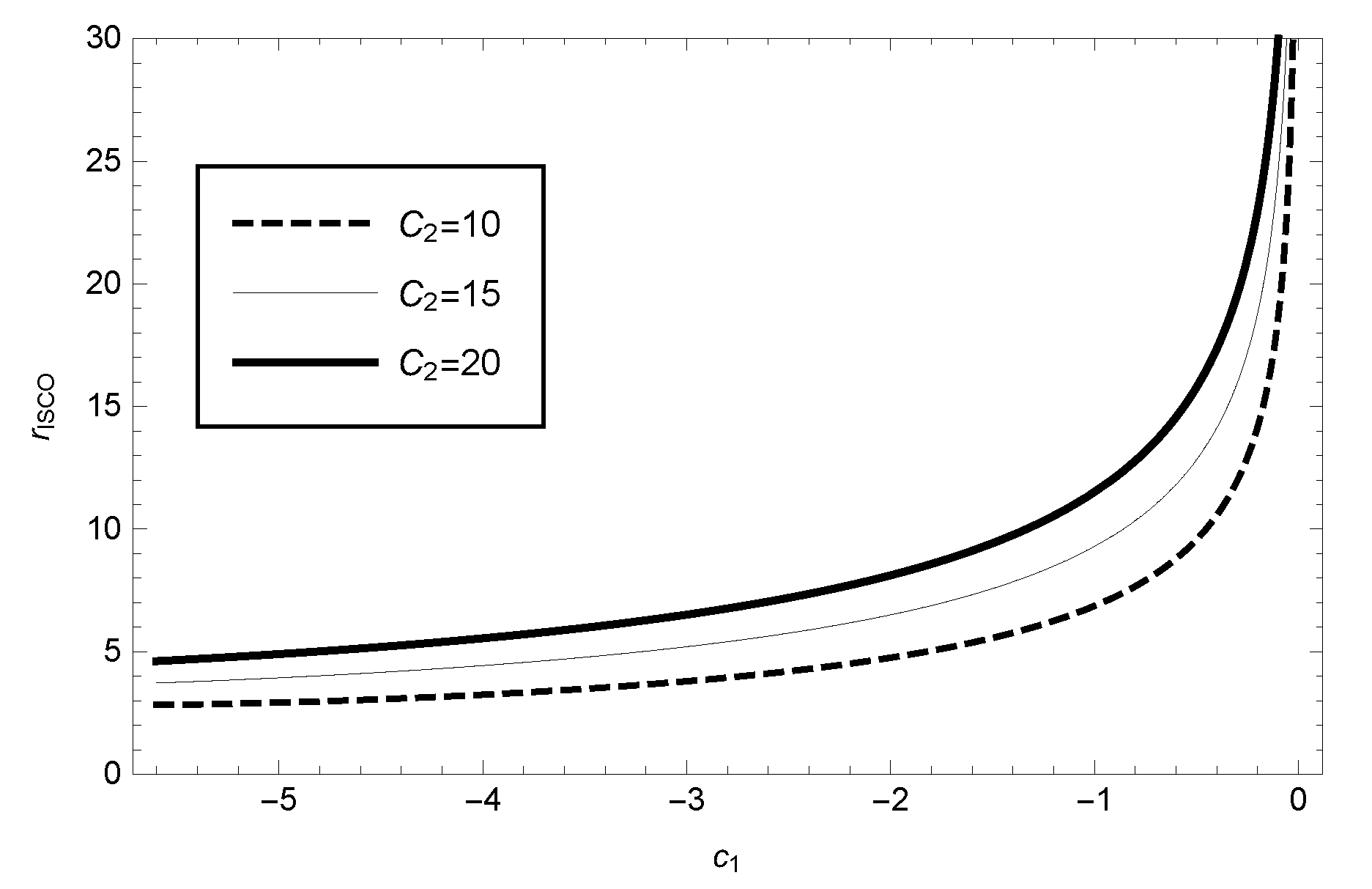

Solving the above equation numerically, we can plot the variation of the ISCO radius with respect to the parameters (as shown in

Figure 4). Our calculations show that the radius of the ISCO in the GBD modified gravity theory framework will continuously increase with increasing values of the parameters

and

.

We also investigate the properties of angular momentum of particles in the GBD theory. Considering the condition of circular orbits in the equatorial plane:

we obtain the expressions for

t and

by calculating the components of the motion equation (

28):

From equations (

42) and(

43), we derive the expression for angular velocity as:

Furthermore, substituting equation (

5) into equation (

44) yields

Using equation (

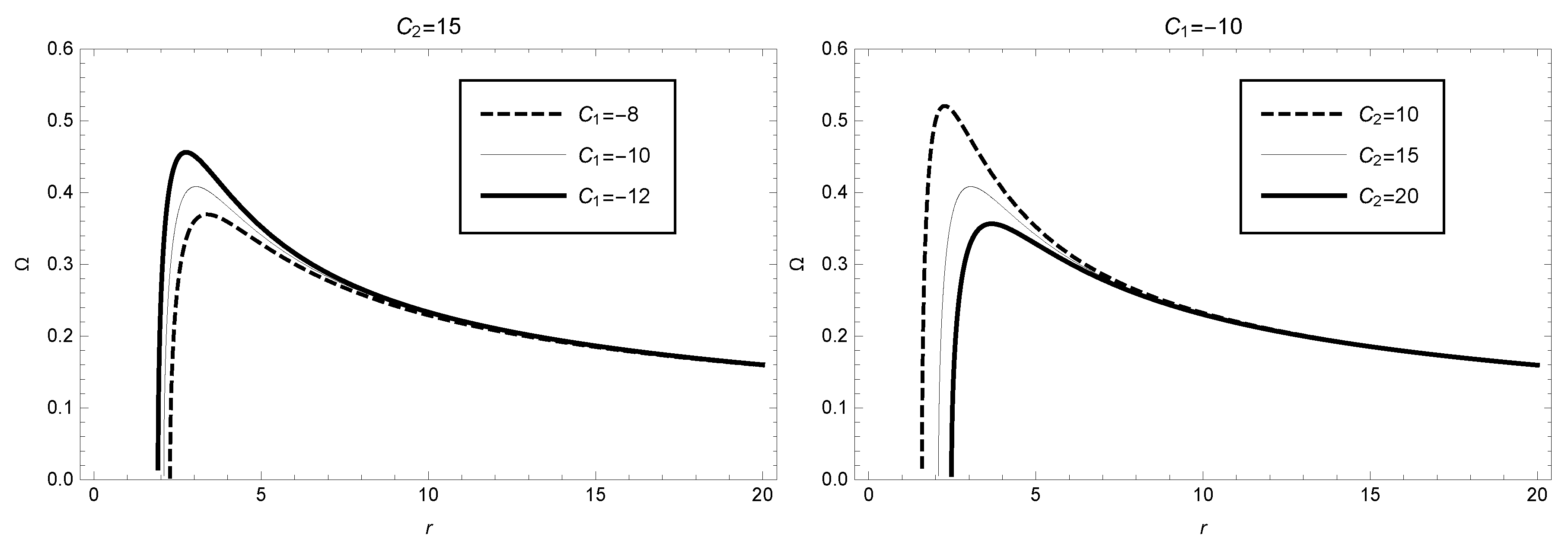

45), we plot the picture of angular velocity as a function of the radius

r in

Figure 5, where parameter values

and

are selected (corresponding to the two thin-solid lines in

Figure 5). For this case we can see that, for these parameter values, the angular velocity sharply increases in the range of radius

r :2.09-3.05, reaches its maximum value

at radius

, and then

decreases to a steady state. In addition, to discuss the variation of angular velocity with respect to the parameters

and

, we also plot the curves for different values of these parameters in

Figure 5. For example, in the left panel of

Figure 5, we consider

,

with values of -8, -10, and -12, respectively. In the right panel of

Figure 5, we consider

,

with values of 10, 15, and 20, respectively. From

Figure 5, we observe that the values of angular velocity decrease with increasing values of

or

.

Also, we can derive to get the specific expressions of energy and angular momentum of unit mass particles in GBD modified theory as follows:

Figure 6 shows the variation of energy and angular momentum of a unit mass particle with radius. From the figure, it can be seen that when the parameter values are taken as

and

, the energy sharply decreases in the radius interval 12.62-24.86, and reaches its minimum value

at the radius

. It then gradually increases. The variation trend of angular momentum is similar to that of energy, also reaching its minimum value

at the radius

. The variation of

E and

J for different parameter values

and

can be seen in detail in

Figure 6. In the plots on the left, takes the value of

, while in the plots on the right, takes the value of

.

To study the issue of circular orbit stability of particles moving around a spherically symmetric black hole in GBD theory, we consider the application of the geodesic deviation equation. The geodesic deviation equation is given by:

where

is the deviation four-vector. By substituting the spherically symmetric line element (

4) and using equations (

41)-(

43), we can derive the expressions for the geodesic deviation equation components:

Obviously, the solution to equation(

51) can be expressed as

. This indicates that the circular orbits of test particles initially in the equatorial plane will undergo harmonic vibration under perturbations. Therefore, the circular orbit of particle motion is stable. For other equations, assuming the solution takes the form:

then substituting equations(

53)-(

55) into equations (

49), (

50), and(

52), and considering the stability requirement for circular orbit motion, we derive the following constraints:

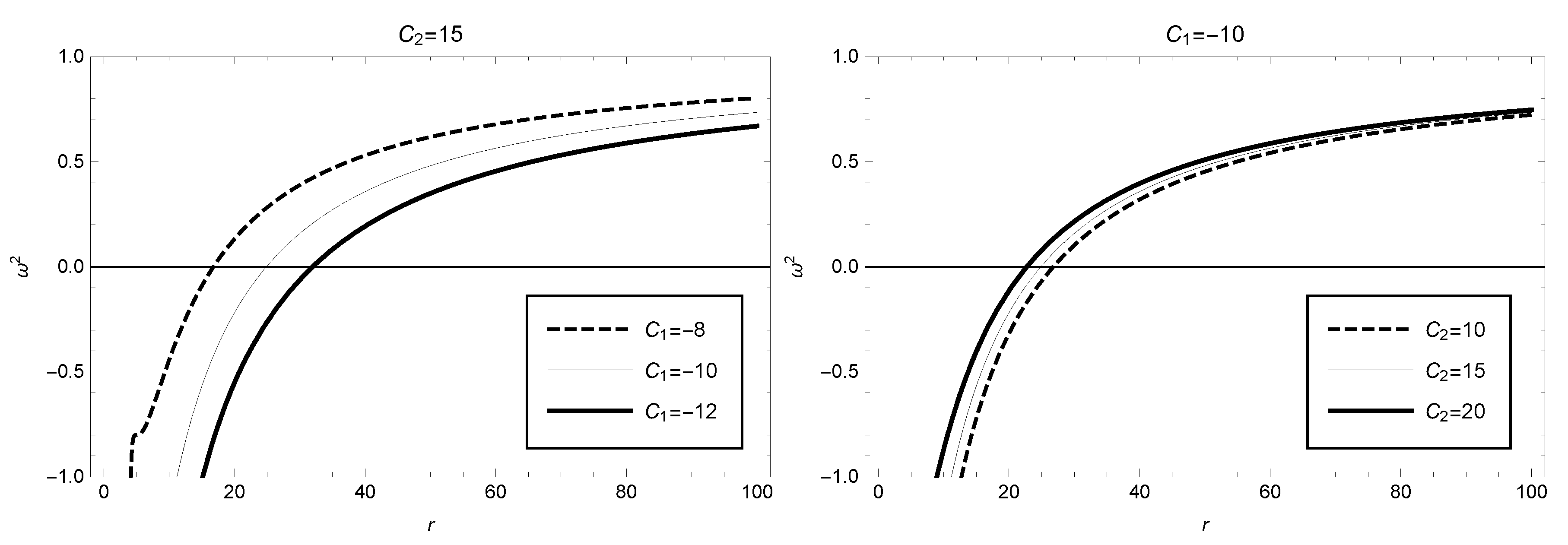

By substituting expression (

5) into the above equation(

56), we show in

Figure 7 the dependence of the parameter

on the circular orbit radius

r. When the integral constants are taken as

and

, we find that the stable region of circular orbits

is :

. The effects of other model parameter values on the parameter

and the corresponding stable circular orbit regions are shown in

Figure 6 (the left figure with

taken as 15 and the right figure with

taken as -10).