1. Introduction

The ovarian corpus luteum is the female reproductive organ and rapid growth and regression with many structural and functional mechanisms [

1]. During the formation and regression of the corpus luteum, this temporary endocrine gland undergoes physiological events, including angiogenesis and apoptosis [

2,

3]. Also, the corpus luteum microenvironment complex signaling pathways, including Ral-interacting protein 76 (RLIP76), small GTPase (R-Ras), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1). Recently, we found that RLIP76 and R-Ras expressed in the luteal endothelial and luteal cells [

4]. RLIP76 and R-Ras protein is also expressed in humans’ ovaries and tumor blood vessels [

5,

6]. The process of corpus luteum and the tumor is similar in tumorigenesis and ovarian corpus luteum formation, such as angiogenesis events.

Tumor tissue is an abnormal solid mass whose growth depends on vascular density [

7]. The tumor vasculature is regulated by tumor growth and therapeutic intervention for cancer [

8,

9,

10]. Studies on tumor angiogenesis are important to understand the molecular mechanisms for inhibiting tumor growth. Tumor angiogenesis is essential for invading tumor growth and is an important factor in regulating cancer progression. The inhibition of angiogenesis in tumors is a novel cancer therapeutic approach to novel cancer therapy. Tumor cells secrete angiogenic factors during tumor growth, and the factor supports vascular growth. Also, endothelial and tumor cells have various cell functions, such as proliferation, migration, and spreading. To study the angiogenesis in tumorigenesis, tumor angiogenesis may be an important key in the mechanism of tumor inhibition and cancer therapy associated with RLIP76, R-Ras, VEGF, and HIF-1.

RLIP76, also known as RalBP1, is a multifunctional protein for treating tumors, such as for the regression of melanoma, breast and lung cancer, and inhibition of carcinoma [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. RLIP76 is overexpressed in melanomas, lung, and ovarian cancers, indicating that RLIP76 can regulate tumor growth and stimulate vasculature development for tumor progression [

16]. Recently, we have reported that RLIP76 regulated the neovascularization of tumors using knockout mice and wild-type mice [

11]. Tumorigenesis (xenografted tumors) and tumor angiogenesis (xenografted Matrigel plugs) in RLIP76 knockout mice were attenuated, suggesting that RLIP76 was required for cancer progression and survival via vascular growth and tumor angiogenesis. Also, RLIP76 regulates cell survival, spreading, and migration by activated R-Ras, suggesting that small GTPase regulates cell morphology and motility. Moreover, the corpus luteum has a similar microenvironment which is angiogenesis for cell growth. Angiogenesis of tumors and the corpus luteum is essential for growing tissues and cells. The proteins of RLIP76 and VEGF are expressed in the corpus luteum as tumors, suggesting that the tumor and corpus luteum have analogous microenvironments. In this article, we will describe the roles of RLIP76/R-Ras and VEGF via HIF-1 in the angiogenesis and microenvironment of the corpus luteum and tumor and the specific regulation in the ovarian corpus luteum and tumors.

2. RLIP76 in the Tumor Microenvironment

RLIP76 is a multifunctional and potential modular protein in mammals, which plays an important role in tumor cells, cell signaling, and xenobiotic defense mechanisms [

17,

18,

19,

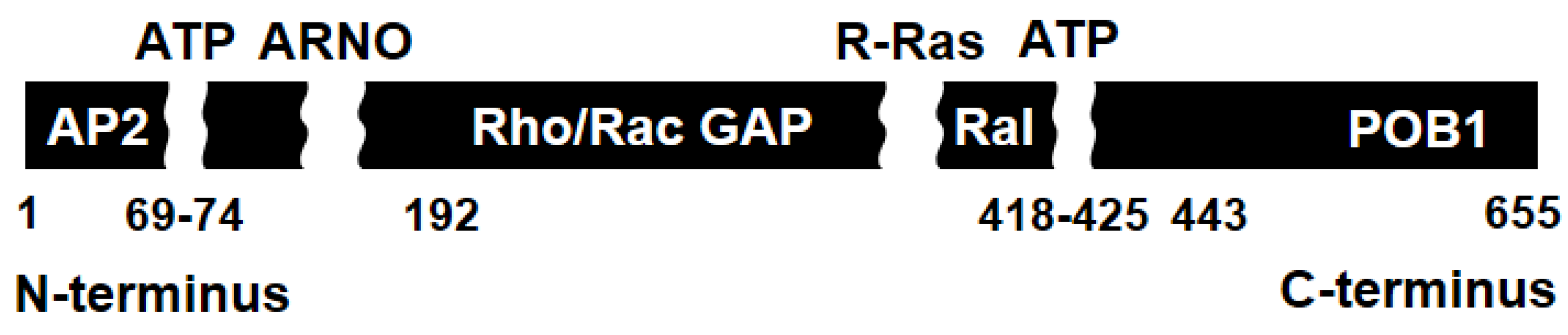

20]. RLIP76 is composed of 655 amino acids and contains a GTPase activating protein domain (RhoGAP domain), a Ral-binding domain (RalBD), and ATP-binding sites, and interacts with Ras-related protein (R-Ras,

Figure 1). The protein is a guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-dependent interaction partner with RalA. It binds directly to RalB [

21,

22]. Ral protein, a signal transducer, activates guanine diphosphate and binds to guanine triphosphate. RLIP76 is a Ral effector that interacts with Ral protein and activates cell functions, such as cell migration and spreading [

20,

21,

22].

RLIP76 regulates tumorigenesis, cell spreading, migration, mitosis, endocytosis, and apoptosis [

13,

16,

23,

24,

25]. Briefly, RLIP76 inhibits apoptosis and promotes the proliferation of human malignant glioma via activation of Rac1-Jun NH

2 kinase (JNK) [

24,

25]. This suggests that RLIP76 is required for tumorigenesis and suppression of apoptosis. In cell motility, RLIP76 is a mediator in the effect of R-Ras on cellular spreading and migration through the activation of Arf6 GTPase via binding to RLIP76/R-Ras [

23]. Additionally, RLIP76 leads to the loss of mitochondrial fission through cyclin B-cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) kinase, a mitotic cyclin-dependent kinase, and activation by phosphorylation of dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) during mitosis [

26]. RLIP76 is involved in endocytosis by binding to activating protein 2 (AP2) on the N-terminal region, partner of RalBP1 (POB1) on the C-terminal and associated Eps homology domain protein, RalBP1-associated Eps domain-containing protein 1 (Reps1) [

27,

28]. In endothelial cells, RLIP76 regulates the intracellular levels of 4-hydroxy-t-2,3-nonenal (HNE) and glutathione [

17,

19]. It also activates the C-JNK signaling pathway in endothelial cells, suggesting that RLIP76 leads to cell differentiation and cellular signaling pathway in apoptosis [

15,

29,

30].

3. RLIP76 and VEGF are Required in Tumor Angiogenesis

In angiogenesis, RLIP76 has potential roles in the function of endothelial cells in the microvasculature. RLIP76 regulates tumorigenesis and metastasis by regulating endothelial cell migration and proliferation and stimulating tumor cells’ activation and differentiation. Also, the vasculature in solid tumors is very complex and has many branched capillaries during angiogenesis [

11,

30,

34]. Overall, RLIP76 plays a role in molecular and physiological functions and processes in tumor angiogenesis.

Recently, we reported a novel physiological role of RLIP76 in angiogenesis and tumorigenesis in mice [

11]. During the growth of carcinoma, we tested the vascular quantification of carcinoma in wild-type and RLIP76 knockout mice using X-ray micro-computed tomography in a 3D system (performed using SKYScan software and analyzed by CTAn 3D program). We found that the growth of tumor vasculature in RLIP76 knockout mice was suppressed. Briefly, the volumes, density, and tortuosity of vasculature were diminished in both types of mice. Analysis in wild-type and knockout mice is important to determine the role of RLIP76 in tumor angiogenesis, mean vessel density, specific surface areas, and vessel tortuosity in angiogenesis. RLIP76 is a main factor that grows vasculature and affects tumor angiogenesis. Additionally, the vascular network can understand the tumor’s structure and growth by measuring the microvascular branch, suggesting that vessels in tumors are unstable and irregular during tumor growth.

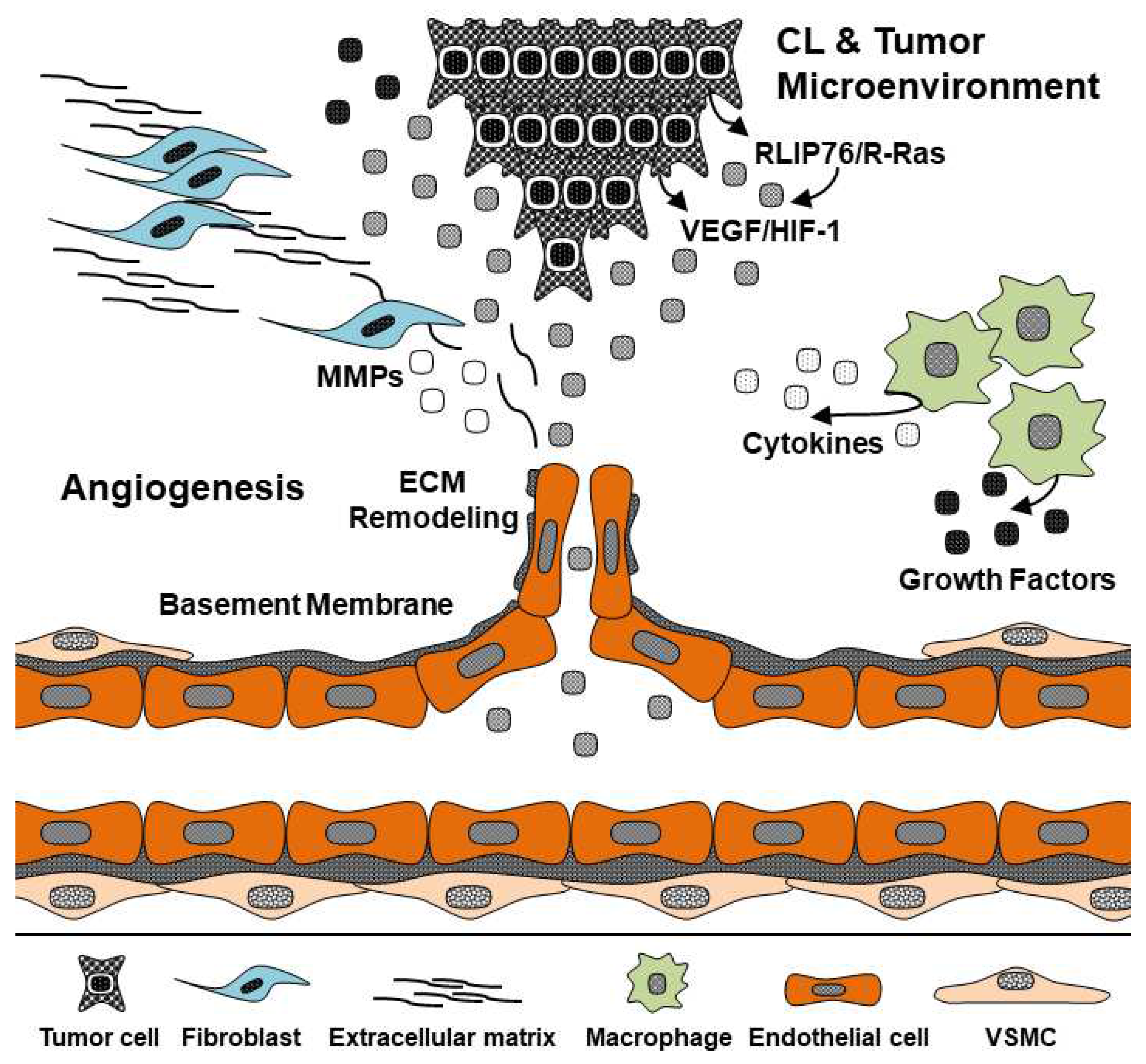

The molecular mechanism of RLIP76 in corpus luteum and tumor angiogenesis is still unknown. Tumor growth has various microenvironment conditions, such as low oxygen, cytokines, growth factors, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and macrophages (

Figure 2) [

35,

36,

37]. We recently found that RLIP76 regulates VEGF, an angiogenic growth factor, in the tumor cell function as it stimulates VEGF expression in melanoma and carcinoma cells, suggesting VEGF production by RLIP76 from tumor cells could be regulated in tumor angiogenesis [

38]. Additionally, RLIP76 regulates the transcriptional activity of HIF-1 and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) in tumors. RLIP76 is required for HIF-1 activation in melanoma and carcinoma tumors. Moreover, RLIP76 is an important protein in PI3K activation since HIF-1 could activate the PI3K pathways, as we have previously shown that the inhibition of RLIP76 by short hairpin ribonucleic acid (shRNA) suppressed PI3K activity downstream of PI3K. Thus, we suggest RLIP76 and VEGF are required for PI3K activity in tumor angiogenesis.

The RLIP76 is required for cell spreading and migration with R-Ras activation [

23]. We studied RLIP76 in the migration and spreading of endothelial cells and tumor cells, which is regulated by the R-Ras-regulated pathway, such as a small GTPase R-Ras effector [

31,

32]. The adapter function of RLIP76 also induces a small GTPase guanine exchange factor (ARNO). R-Ras is necessary to recycle endosomes to spread and migrate cancer cells [

31]. RLIP76 is important in cell spreading by mediating the Ral protein [

33].

Moreover, Goldfinger et al. reported that R-Ras-bound RLIP76 regulates cell spreading and migration via the Arf6-activated Rac1 pathway [

23]. Arf6 is inactivated by the blocked RLIP76, and the negative control of R-Ras inhibited the Arf6 activation. Also, the mutated Arf6 blocked Rac1 localization and formation in the cells. These results suggest that the activation and presence of RLIP76 may associate with Arf6/Racl interaction. However, some studies reported RLIP76 has not bound to multiple Ras families as H-Ras, but not RalA in mammalian cells [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. It seems likely that RalA is not directly regulated in the RLIP76/Ras pathway of cell spreading. Indeed, R-Ras directly binds to RLIP76 and stimulates R-Ras in cell spreading, suggesting that RLIP76 interacts with R-Ras and specific mediators.

4. Microenvironment in Ovarian Corpus Luteum

The morphological and physiological characteristics of the ovarian corpus luteum are dynamically changed during the estrous cycle, such as progesterone production, vessel distribution, and weight [

45]. The Corpus luteum in the ovulated stage is generated from granulosa cells, theca cells, endothelial cells, and other pericytes. Normally, granulosa and theca cells differentiate into luteal steroidogenic cells by luteinizing hormone. At the same time, proliferation is actively increased [

46,

47]. In practice, the development of the corpus luteum in cows proceeded during 8 days after ovulation in cows. The weight of the corpus luteum increases three or four times when the development of the corpus luteum is finished [

48]. Accordingly, nutrients, oxygen, hormones, and growth factors are sufficiently supported for the differentiation and growth of luteal steroidogenic cells through the vascular development system, suggesting the formation of vessels is necessary for completing the development of the corpus luteum in the luteal phase [

47].

Luteal steroidogenic cells are classified into large and small luteal steroidogenic according to cell size, and large luteal steroidogenic cells originate from granulosa cells. In contrast, thecal cells differentiate into small luteal steroidogenic cells [

49]. Luteal steroidogenic cells produce progesterone from cholesterol via enzymes, such as steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), cholesterol side chain cleavage (P450scc), and 3

β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3

β-HSD) [

49]. Synthesized progesterone in the corpus luteum moved on the blood vessels, which regulates the development of endometrium for embryo implantation and pregnancy maintenance [

50]. Additionally, we reported that steroidogenic synthesis and angiogenetic factors were selectively expressed in luteal cell types of the bovine corpus luteum [

51]. Thus, we strongly suggest that the formation and maintenance of vessels during the development of the corpus luteum is important for transporting the synthesized progesterone.

Prostaglandin F2 alpha induces regression of corpus luteum (luteolysis), which affects to loss of progesterone production and activation of apoptotic signals in luteal cells [

51,

52,

53]. During luteolysis, cytokines, nitric oxide, leukotriene C4, and endothelin-1 increase in the corpus luteum microenvironment [

54,

55]. These factors lead to apoptosis in luteal steroidogenic cells and endothelial cells [

52]. Additionally, we found that the connection of cell adhesions in bovine luteal steroidogenic cells is decreased by prostaglandin F2 alpha [

51]. The Corpus luteum comprises heterogeneous cells, and cell adhesion between endothelial cells and luteal steroidogenic cells is the main function for maintaining the corpus luteum structure [

48]. Therefore, we suggest understanding adhesions between endothelial cells and luteal steroidogenic cells by prostaglandin F2 alpha is very important for anti-angiogenesis using hormone therapy in reproductive biomedical fields.

In addition, progesterone and oxytocin, including progesterone receptor (PR) and oxytocin receptor (OR), play essential roles in maintaining the corpus luteum in the ovary [

56]. During pregnancy in the mammalian ovary, the balance of progesterone is necessary for developing endometrium and fetus. Also, progesterone concentration is increased during the formation of the corpus luteum, but the production of progesterone is decreased during the degression of the corpus luteum. The dynamic phenomenon of progesterone may be essential in the function mechanism of ovarian corpus luteum, such as prostaglandin F2 alpha. Oxytocin is a nonapeptide hormone released from the posterior pituitary gland [

57]. In the female reproductive system, oxytocin stimulates uterine contractions via G-protein coupled receptors. Interestingly, Shirasuna et al. reported that the concentration of oxytocin enhanced significantly with endothelin 1 and prostaglandin F2 alpha during luteolysis in the bovine corpus luteum [

58]. Endometrium prostaglandin F2 alpha stimulates ovarian oxytocin, and the stimulated oxytocin also elevates the prostaglandin F2 alpha in the corpus luteum. Actually, prostaglandin F2 alpha directly induces a low progesterone concentration in the ovarian corpus luteum, and oxytocin directly induces an increase in progesterone secretion. Therefore, we suggest that prostaglandin F2 alpha and oxytocin may interact with progesterone during luteolysis in the ovarian corpus luteum. Overall, reproductive hormones play a dynamic role in the formation and regression of the corpus luteum in the mammalian ovary. Thus, prostaglandin F2 alpha and oxytocin will be triggered with progesterone for processing the functional luteolysis in the ovarian corpus luteum.

5. Angiogenesis in the Ovarian Corpus Luteum

Angiogenesis of the corpus luteum has a dynamic microenvironment in which blood flow conditions, low oxygen conditions, changed cell types, dependent hormone concentration, and specific hormones. Normally, angiogenesis regulates endothelial cells (ECs), matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), extracellular matrix (ECM), and basement membrane (BM). Angiogenesis also forms novel vessels during tissue development with cell spreading, migration, proliferation, and differentiation. We explained above that the corpus luteum is similar to normal angiogenesis functions. Especially, the corpus luteum depends on steroid hormones, such as estrogen, progesterone, and prostaglandin F2 alpha. The corpus luteum has luteal cells, endothelial cells, and other cells for forming the corpus luteum and is a very complex tissue [

59]. We reported cell types of corpus luteum isolated from bovine corpus luteum, such as luteal steroidogenic cells, luteal theca cells, and luteal endothelial cells [

60,

61]. Granulosa and theca cells changed to luteal cells during corpus luteum formation, and luteal endothelial cells came to vascular [

59,

60]. Thus, we suggest that angiogenesis function in the corpus luteum is very important for finding novel functions in the ovarian corpus luteum.

VEGF is a major promoter in angiogenesis and also plays an important factor in the physiology of ovarian corpus luteum. We found angiogenic receptors expressed in corpus luteum tissues during estrous cycles [

62]. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) and angiopoietin 1, 2 receptors (Tie2) are important for growing endothelial cells and vascular formation. Both angiogenic receptors protein are expressed in the early and middle estrous cycle but not the late estrous cycle. We suggest that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and angiopoietin reads to the formation of noel vascular in the ovarian corpus luteum. Although the specific angiogenic proteins depend on other hormones, it is interesting in the mechanisms of corpus luteum formation.

The corpus luteum has formation and regression of tissues during estrus cycles since the corpus luteum is a temporary endocrine organ [

63,

64]. Regression of the corpus luteum is also important, such as the formation of the corpus luteum. At the end of the formation, activation of angiogenic proteins is decreased for preparing luteolysis. Hormone secretion is also changed, such as progesterone and prostaglandin F2 alpha. Progesterone comes to luteal cells and regulates cell proliferation, migration, and spreading [

65,

66,

67]. Prostaglandin F2 alpha is increased during regression of the corpus luteum and comes to uterus and ovarian luteal cells. Thus, we are continually studying the novel mechanism of the formation and regression of the corpus luteum. Knowing the interaction of ovarian hormones and angiogenic proteins is very important in the angiogenesis of the ovarian corpus luteum.

6. The Function of RLIP76 and VEGF in the Ovarian Corpus Luteum

The ovarian corpus luteum has RLIP76 and VEGF proteins. RLIP76 has many molecular biology functions and physiological functions in various regulations of cellular. In the signaling pathway, RLIP76 plays an essential role in the Ras protein activator, binding protein partner of endocytosis regulation and cytoskeleton, transport function in the cell stress response, and biochemical property in the biological membrane [

19,

28,

68,

69,

70]. Recently, we found mRNA and protein of RLIP76 in the bovine corpus luteum during estrous cycles [

59]. To determine whether RLIP76 in the corpus luteum is associated with increased angiogenic VEGF expression and activation, we experimented with mRNA and protein expression. In our studies, RLIP76 mRNA was expressed at high levels in the early stage of the bovine corpus luteum, suggesting RLIP76 leads to the generation of the corpus luteum in the bovine. However, the mechanism of RLIP76 function is still unclear in the mammalian. Awasthi

et al. reported that RLIP76 overexpressed in ovarian carcinoma and melanoma cells [

71]. RLIP76 is also regulated in PI3K/AKT and Erk signaling pathways and VEGF/HIF-1 in hypoxia conditions [

24,

38]. The VEGF expression in primary murine endothelial cells is increased by H-Ras, a GTPase protein [

72]. Arbiser

et al. demonstrated that H-Ras leads to enhanced VEGF levels, and elevated expression of VEGF under hypoxia conditions, a known VEGF stimulator. HIF-1 is also overexpressed in low oxygen conditions (hypoxia). We also reported that H-Ras was expressed in the early and middle stages of the bovine corpus luteum [

62]. Moreover, H-Ras acts on the formation of tumor tissues by binding to G-protein receptors. H-Ras also enhances VEGF expression and increases the activity of the matrix metalloproteinase-2, 9 (MMP-2, 9) involved in cell proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis. Therefore, since H-Ras is expected to play a new functional role in the ovarian corpus luteum, the mechanism needs to be clarified through additional cell experiments. In addition, we may need to measure the mRNA and protein expression of H-Ras and RLIP76 in the tissue and cell of the ovarian corpus luteum by estrous cycle to determine whether the factors involved in tumorigenesis were expressed in corpus luteum tissue. Moreover, the mRNA and protein of the VEGF levels were highly expressed in the early and middle corpus luteum in cows, and VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) was also expressed at the highest level in the early corpus luteum. These results suggest that RLIP76 and VEGF play an important role in the angiogenesis of the bovine corpus luteum.

VEGFR 2 and Tie 2 are the main angiogenesis-related receptors, both are higher in bovine corpus luteum tissues in the early and middle stages than in the later stage. Angiopoietin family, including Angiopoietin 1 and 2 (Ang 1 and Ang 2), competitively binds to the endothelial cell-specific receptor, Tie 2. Tie 2 is involved in the stabilization and reconstitution of blood vessels [

73]. Ang 1 is also an angiogenic factor that signals pathways via the EC-specific Tie 2 receptor tyrosine kinase. Ang 1 binds Tie 2 and enhances the tyrosine phosphorylation of Tie 2 in endothelial cells. Also, Tie 2 mRNA and protein were found to be expressed at the highest levels in the corpus luteum of buffalo [

74]. Also, Hayashi et al. and Sugino et al. reported that the Ang 1/Tie 2 signal system was developed in the bovine corpus luteum [

75,

76]. Ang 1 and Tie 2 mRNA was expressed in theca interna of bovine during mature follicles, follicular development, and follicular atresia. The ratio of Ang 2/Ang 1 mRNA was increased in the early stage, and also elevated Tie 2 mRNA. Ang 1 for vascularization is activated by Tie 2 in endothelial cells, but Ang 2 is the antagonist for Ang 1. In fact, Ang-2 can induce the regression of vascular with Ang 1 inhibition. Thus VEGF, Ang 1, Ang 2, and Tie 2 play important roles in angiogenesis and ovarian corpus luteum. The balance of both Ang 1 and Ang 2 may be key for structural and functional luteolysis of the corpus luteum. But, it is not clear whether VEGF, Ang 1/Tie 2 and Ang 2 regulate luteolysis and the regression of vascular in the ovarian corpus luteum. Moreover, the concentration of estradiol and progesterone was enhanced in Ang 1-treated cells. It means that the life of the ovarian corpus luteum is also dependent on reproductive hormones, such as estrogen, progesterone, prostaglandin F2alpha, and oxytocin. The signaling pathway of the ovarian corpus luteum has a complex maze. As above described results, we suggest that Ang 1/Tie 2 system is important in the VEGF-regulated signaling pathway in the ovarian corpus luteum.

VEGF receptors, VEGFR 1 (Flt 1, fms-related tyrosine kinase 1) and VEGFR 2 (KDR, kinase insert domain receptor), are needed for the activation of the VEGF function [

77]. Both receptors of VEGF play a central role in angiogenesis, including the migration and proliferation of endothelial cells. VEGFR 2 has a strong positive signal in angiogenesis, such as VEGF/VEGFR 2. On the other hand, VEGFR 1 has an anti-angiogenesis function in the embryogenesis of mice. Thus we focused on the VEGF/VEGFR 2 signaling pathway in the ovarian corpus luteum. In fact, VEGF binds both VEGFR 1 and VEGFR 2 in mammals, such as VEGFR 1 for cell migration in pathological angiogenesis, and VEGFR 2 for cell proliferation in endothelial cells. Takahashi et al. reported that protein kinase C (PKC)/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway activation with VEGFR 2 is necessary for DNA synthesis in endothelial cells [

78]. Gecaj et al. found that the level of VEGFR 2 was higher during the early estrous cycle in the bovine corpus luteum [

79]. Lee et al. showed that vascular receptors are strongly expressed in the early and middle phases of the corpus luteum in bovine. VEGF and its receptor signal systems are well documented in the ovarian corpus luteum. However, the reproductive hormones-related VEGF signaling pathway is still unclear in luteal endothelial cells. Since ovarian corpus luteum depends on estrogen, progesterone, prostaglandin F2alpha, oxytocin, etc., the research groups maybe need more studies about the function of reproductive hormones with VEGF-regulated signals in for understanding the angiogenesis and apoptosis mechanisms. Nevertheless, these demonstrated findings VEGF/VEGF2 signaling pathway is essential for angiogenesis and the therapy of ovarian cancer in the ovarian corpus luteum.

7. Conclusion

RLIP76 regulates tumor growth and vascular formation in tumor angiogenesis and controls VEGF protein expression in tumor cells. VEGF induced by HIF-1 activation under hypoxic conditions can influence by RLIP76. We suggest that RLIP76/R-Ras regulates VEGF via HIF-1alpha activation, stimulating tumor angiogenesis and enhancing tumor growth. Moreover, angiogenesis in the ovarian corpus luteum is essential for luteal formation and maintenance during the luteal phase. Thus, RLIP76 and VEGF may be required in angiogenesis mechanisms for activating the physiological functions of the ovarian tumor and ovarian corpus luteum.

8. Future Directions

In the future, research groups need to study reproductive hormones-regulated molecular processes and signaling pathways with RLIP76 and VEGF in the ovarian corpus luteum, ovarian cancer, and tumor, since the reproductive endocrine system is important in the ovary. Moreover, RLIP/Ras family and VEGF/HIF-1 are involved in the angiogenesis of tumors and ovarian corpus luteum in humans and animals. These results will be useful data for knowing novel functions and mechanisms of the ovarian corpus luteum and ovarian cancer and tumor.

Author Contributions

T.-H.M. and S.L. contributed to writing and reviewing the manuscript and figures.

Funding

Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2018R1D1A3B07048167).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (2018R1D1A3B07048167).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that I have no competing interests.

List of Abbreviations

Ral-interacting protein, RLIP76; Vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF; Hypoxia-inducible factor-1, HIF-1; Ral-binding domain, Progesterone receptor, PR; Oxytocin receptor, OR; RalBD; Jun NH2 kinase, JNK; Ras-related protein, R-Ras; ADP-ribosylation factor 6, Arf6; Mitotic cyclin-dependent kinase, B-CDK1 kinase; Dynamin-related protein 1, DRP1; Activating protein 2, AP2; Partner of RalBP1, POB; RalBP1-associated Eps domain-containing protein 1, Reps1; 4-hydroxy-t-2,3-nonrenal, HNE; C-Jun N-terminal kinases, C-JNK; Arf nucleotide site opener, ARNO; Matrix metalloproteinases, MMPs; Extracellular matrix, ECM; Phosphoinositide 3-kinase, PI3K; Short hairpin ribonucleic acid (shRNA).

References

- Telfer:, E.E.; Anderson, R.A. The existence and potential of germline stem cells in the adult mammalian ovary. Climacteric 2019, 22, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schams, D.; Berisha, B. Regulation of corpus luteum function in cattle - An overview. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2004, 394, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devoto, L.; Fuentes, A.; Kohen, P.; Cespedes, P.; Palomino, A.; Pommer, R.; Munoz, A.; Strauss, J.F., III. The human corpus luteum: life cycle and function in natural cycles. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 92, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Qi, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Qin, C. RLIP76 decreases apoptosis through Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in gastric cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 2216–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, J.; Urakami, T.; Li, F.; Urakami, A.; Zhu, W.; Fukuda, M.; Li, D.Y.; Ruoslahti, E.; Komatsu, M. Small GTPase R-Ras regulates integrity and functionality of tumor blood vessels. Cancer cell 2012, 22, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, S. Change of Ras and its guanosine triphosphatases during development and regression in bovine corpus luteum. Theriogenology 2020, 144, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Barbe, M.F.; Scalia, R.; Goldfinger, L.E. Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of Neovasculature in Solid Tumors and Basement Membrane Matrix Using Ex Vivo X-ray Microcomputed Tomography. Microcirculation 2014, 21, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, J. Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin. Oncol. 2002, 29, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Zhang, J. Angiogenesis: a curse or cure? Postgrad. Med. J. 2005, 81, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, N.M.; Dhalla, N.S.; Santani, D.D. Angiogenesis—a new target for future therapy. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2006, 44, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Wurtzel, J.G.T.; Singhal, S.S.; Awasthi, S.; Goldfinger, L.E. ; RALBP1/RLIP76 depletion in mice suppresses tumor growth by inhibiting tumor neovascularization. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 5165–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollberg, N.M.; Steinert, G.; Aigner, M.; Hamm, A.; Lin, F.J.; Elbers, H.; Reissfelder, C.; Weitz, J.; Buchler, M.W.; Koch, M. Overexpression of RalBP1 in colorectal cancer is an independent predictor of poor survival and early tumor relapse. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2012, 13, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, S.S.; Awasthi, Y.C.; Awasthi, S. Regression of melanoma in a murine model by RLIP76 depletion. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 2354–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, S.S.; Singhal, J.; Nair, M.P.; Lacko, A.G.; Awasthi, Y.C.; Awasthi, S. Doxorubicin transport by RALBP1 and ABCG2 in lung and breast cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2007, 30, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, S.S.; Singhal, J.; Yadav, S.; Dwivedi, S.; Boor, P.J.; Awasthi, Y.C.; Awasthi, S. Regression of lung and colon cancer xenografts by depleting or inhibiting RLIP76 (Ral-binding protein 1). Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 4382–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Gupta, S.; Singh, S.V.; Medh, R.D.; Ahmad, H.; LaBelle, E.F.; Awasthi, Y.C. Purification and characterization of dinitrophenylglutathione ATPase of human erythrocytes and its expression in other tissues. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990, 171, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, S.; Singhal, S.S.; Pikula, S.; Piper, J.T.; Srivastava, S.K.; Torman, R.T.; Bandorowicz-Pikula, J.; Lin, J.T.; Singh, S.V.; Zimniak, P.; et al. ATP-dependent human erythrocyte glutathione-conjugate transporter. II. Functional reconstitution of transport activity. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 5239–5248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, S.; Singhal, S.S.; Srivastava, S.K.; Torman, R.T.; Zimniak, P.; Bandorowicz-Pikula, J.; Singh, S.V.; Piper, J.T.; Awasthi, Y.C.; Pikula, S. ATP-Dependent human erythrocyte glutathione-conjugate transporter. I. Purification, photoaffinity labeling, and kinetic characteristics of ATPase activity. Biochemistry. 1998, 37, 5231–5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, S.; Cheng, J.; Singhal, S.S.; Saini, M.K.; Pandya, U.; Pikula, S.; Bandorowicz-Pikula, J.; Singh, S.V.; Zimniak, P.; Awasthi, Y.C. Novel function of human RLIP76: ATP-dependent transport of glutathione conjugates and doxorubicin. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 9327–9334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.H.; O’Hayer, K.; Adam, S.J.; Kendall, S.D.; Campbell, P.M.; Der, C.J.; Counter, C.M. Divergent roles for RalA and RalB in malignant growth of human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, 2385–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jullien-Flores, V.; Dorseuil, O.; Romero, F.; Letourneur, F.; Saragosti, S.; Berger, R.; Tavitian, A.; Gacon, G.; Camonis, J.H. Bridging ral GTPase to Rho pathways RLIP76, a ral effector with CDC42/Rac GTPase-activating protein activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 22473–22477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.H.; Baines, A.T.; Fiordalisi, J.J.; Shipitsin, M.; Feig, L.A.; Cox, A.D.; Der, C.J.; Counter, C.M. Activation of RalA is critical for Ras-induced tumorigenesis of human cells. Cancer Cell 2005, 7, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldfinger, L.E.; Ptak, C.; Jeffery, E.D.; Shabanowitz, J.; Hunt, D.F.; Ginsberg, M.H. RLIP76 (RalBP1) is an R-Ras effector that mediates adhesion-dependent Rac activation and cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhang, X.P.; Lv, Z.W.; Fu, D.; Lu, Y.C.; Hu, G.H.; Luo, C.; Chen, J.X. RLIP76 is overexpressed in human glioblastomas and is required for proliferation, tumorigenesis and suppression of apoptosis. Carcinogenesis 2012, 34, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Qi, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Qin, C. RLIP76 increases apoptosis through Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in gastric cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 2216–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashatus, D.F.; Lim, K.H.; Brady, D.C.; Pershing, N.L.; Cox, A.D.; Counter, C.M. RALA and RALBP1 regulate mitochondrial fission at mitosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.S.; Wickramarachchi, D.; Yadav, S.; Singhal, J.; Leake, K.; Vatsyayan, R.; Chaudhary, P.; Lelsani, P.; Suzuki, S.; Yang, S.; et al. Glutathione-conjugate transport by RLIP76 is required for clathrin-dependent endocytosis and chemical carcinogenesis. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011, 10, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, A.; Urano, T.; Goi, T.; Feig, L.A. An Eps homology (EH) domain protein that binds to the Ral-GTPase target, RalBP1. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 31230–31234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margutti, P.; Matarrese, P.; Conti, F.; Colasanti, T.; Delunardo, F.; Capozzi, A.; Garofalo, T.; Profumo, E.; Rigano, R.; Siracusano, A.; et al. Autoantibodies to the C-terminal subunit of RLIP76 induce oxidative stress and endothelial cell apoptosis in immune-mediated vascular diseases and atherosclerosis. Blood 2008, 111, 4559–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarrese, P.; Colasanti, T.; Ascione, B.; Margutti, P.; Franconi, F.; Alessandri, C.; Conti, F.; Riccieri, V.; Rosano, G.; Ortona, E.; et al. Gender disparity in susceptibility to oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by autoantibodies specific to RLIP76 in vascular cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 2825–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, Y.C.; Chaudhary, P.; Vatsyayan, R.; Sharma, A.; Awasthi, S.; Sharma, R. Physiological and pharmacological significance of glutathione-conjugate transport. J. Toxicol. Env. Health-Pt-b-Crit. Rev. 2009, 12, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.Z.; Sharma, R.; Yang, Y.; Singhal, S.S.; Sharma, A.; Saini, M.K.; Singh, S.V.; Zimniak, P.; Awasthi, S.; Awasthi, Y.C. Accelerated metabolism and exclusion of 4-hydroxynonenal through induction of RLIP76 and hGST5. 8 is an early adaptive response of cells to heat and oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 41213–41223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, Y.C.; Yang, Y.; Tiwari, N.K.; Patrick, B.; Sharma, A.; Li, J.; Awasthi, S. Regulation of 4-hydroxynonenal-mediated signaling by glutathione S-transferases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 37, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heitzer, T.; Schlinzig, T.; Krohn, K.; Meinertz, T.; Münzel, T. Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 2001, 104, 2673–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, E.; Yan, T.; Xu, Z.; Shang, Z. Tumor microenvironment and cell fusion. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 5013592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Dai, Y. Tumor microenvironment and therapeutic response. Cancer Lett. 2017, 387, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Wang, H.; He, J.; Wang, Q. Functions of Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells in Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Goldfinger, L.E. RLIP76 regulates HIF-1 activity, expression and secretion in tumor cells, and secretome transactivation of endothelial cells. Faseb, J. 2014, 28, 4158–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, S.B.; Urano, T.; Feig, L.A. Identification and characterization of Ral-binding protein 1, a potential downstream target of Ral GTPases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995, 15, 4578–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.J. Ras effectors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1996, 8, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, K.; Hinoi, T.; Koyama, S.; Kikuchi, A. The post-translational modifications of Ral and Rac1 are important for the action of Ral-binding protein 1, a putative effector protein of Ral. FEBS Lett. 1997, 410, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, S.L.; Khosravi-Far, R.; Rossman, K.L.; Clark, G.J.; Der, C.J. Increasing complexity of Ras signaling. Oncogene 1998, 1998. 17, 1395–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertli, B.; Han, J.; Marte, B.M.; Sethi, T.; Downward, J.; Ginsberg, M.; Hughes, P.E. The effector loop and prenylation site of R-Ras are involved in the regulation of integrin function. Oncogene 2000, 19, 4961–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebreton, S.; Boissel, L.; Iouzalen, N.; Moreau, J. RLIP mediates downstream signalling from RalB to the actin cytoskeleton during Xenopus early development. Mech. Dev. 2004, 121, 1481–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schams, D.; Berisha, B. Regulation of Corpus luteum function in cattle – an overview. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2004, 39, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Shea, J.D.; Rodgers, R.J.; D’Occhio, M.J. Cellular composition of the cyclic corpus luteum of the cow. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1989, 85, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocco, C.; Telleria, C.; Gibori, G. ; The molecular control of corpus luteum formation, function, and regression. Endocr. Rev. 2007, 28, 117–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xavier, P.; Leão, R.; Oliveira e Silva, P.; Marques Júnior, A. Histological characteristics of the corpus luteum of Nelore cows in the first, second and third trimester of pregnancy. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zoo. 2012, 64, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocco, C.; Telleria, C.; Gibori, G. The molecular control of corpus luteum formation, function, and regression. Endocr. Rev. 2007, 28, 117–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, J.L. Regulation of prostaglandin synthesis by progesterone in the bovine corpus luteum. Prostaglandins 1988, 36, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Jung, B.D.; Lee, S. Effect of prostaglandin F2 alpha on E-cadherin, N-cadherin and cell adhesion in ovarian luteal theca cells. Korean, J. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2019, 51, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Acosta, T.J.; Yoshioka, S.; Okuda, K. Prostaglandin F2 alpha regulates the nitric oxide generating system in bovine luteal endothelial cells. J. Reprod. Dev. 2009, 55, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Acosta, T.J.; Nakagawa, Y.; Okuda, K. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of superoxide dismutase and prostaglandin F2 alpha production in bovine luteal endothelial cells. J. Reprod. Dev. 2010, 56, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, K.; Sakumoto, R. Multiple roles of TNF super family members in corpus luteum function. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2003, 1, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korzekwa, A.; Lukasik, K.; Skarzynski, D. Leukotrienes are auto-/paracrine factors in the bovine corpus luteum: an in vitro study. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2010, 45, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, C.V. Progesterone inhibition of oxytocin signaling in endometrium. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Matsuura, T.; Xue, M.; Chen, Q.Y.; Liu, R.H.; Lu, J.S.; Shi, W.; Fan, K.; Zhou, Z.; Miao, Z.; Yang, J.; Wei, S.; Wei, F.; Chen, T.; Zhuo, M. Oxytocin in the anterior cingulate cortex attenuates neuropathic pain and emotional anxiety by inhibiting presynaptic long-term potentiation. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasuna, K.; Shimizu, T.; Hayashi, K.-G.; Nagai, K.; Matsui, M.; Miyamoto, A. Positive Association, in Local Release, of Luteal Oxytocin with Endothelin 1 and Prostaglandin F2alpha during Spontaneous Luteolysis in the Cow: A Possible Intermediatory Role for Luteolytic Cascade Within the Corpus Luteum. Biol. Reprod. 2007, 76, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Billhaq, D.H. A potential function of RLIP76 in the ovarian corpus luteum. J. Ovarian Res. 2019, 12, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.; Kim, G.Y. Expression of Fas and TNFR1 in the luteal cell types isolated from the ovarian corpus luteum. Biomed. Sci. Lett. 2019, 25, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulafia, O.; Shere, D.M. Angiogenesis of the ovary. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 182, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S. Expression of H-Ras, RLIP76 mRNA and protein, and angiogenic receptors in corpus luteum tissues during estrous cycles. Korean, J. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2018, 50, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L.P.; Killilea, S.D.; Redmer, D.A. Angiogenesis in the female reproductive system. Faseb, J. 1992, 6, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schams, D.; Berisha, B. Regulation of corpus luteum function in cattle-an overview. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2004, 394, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Tarso, S.G.S.; Gastal, G.D.A.; Bashir, S.T.; Gastal, M.O.; Apgar, G.A.; Gastal, E.L. Follicle vascularity coordinates corpus luteum blood flow and progesterone production. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2017, 29, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.Q.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, L.Q.; Sun, X.L.; Luo, D.; Fu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, J.B. MiR-29b affects the secretion of PROG and promotes the proliferation of bovine corpus luteum cells. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kfir, S.; Basavaraja, R.; Wigoda, N.; Ben-Dor, S.; Orr, I.; Meidan, R. Genomic profiling of bovine corpus luteum maturation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, M.; Ishida, O.; Hinoi, T.; Kishida, S.; Kikuchi, A. Identification and characterization of a novel protein interacting with Ral-binding protein 1, a putative effector protein of Ral. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshiba, S.; Kigawa, T.; Iwahara, J.; Kikuchi, A.; Yokoyama, S. Solution structure of the Eps15 homology domain of a human POB1 (partner of RalBP1). FEBS Lett. 1999, 442, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jullien-Flores, V.; Mahé, Y.; Mirey, G.; Leprince, C.; Meunier-Bisceuil, B.; Sorkin, A.; Camonis, J.H. RLIP76, an effector of the GTPase Ral, interacts with the AP2 complex: involvement of the Ral pathway in receptor endocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113, 2837–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, S.; Singhal, S.S.; Awasthi, Y.C.; Martin, B.; Woo, J.H. Cunningham CC and Frankel AE: RLIP76 and Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 4372–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbiser, J.L.; Moses, M.A.; Fernandez, C.A.; Ghiso, N.; Cao, Y.; Klauber, N.; Frank, D.; Brownlee, M.; Flynn, E.; Parangi, S.; Byers, H.R.; Folkman, J. Oncogenic H-ras stimulates tumor angiogenesis by two distinct pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997, 94, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maisonpierre, P.C.; Suri, C.; Jones, P.F.; Bartunkova, S.; Wiegand, S.J.; Radziejewski, C.; Compton, D.; McClain, J.; Aldrich, T.H.; Papadopoulos, N.; Daly, T.J.; Davis, S.; Sato, T.N.; Yancopoulos, G.D. Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science 1997, 277, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Parmar, M.; Yadav, V.; Reshma, R.; Bharati, J.; Bharti, M.; Paul, A.; Chouhan, V.S.; Taru Sharma, G.; Gingh, G.; Sarkar, M. Expression and localization of angiopoietin family in corpus luteum during different stages of oestrous cycle and modulatory role of angiopoietins on steroidogenesis, angiogenesis and survivability of cultured buffalo luteal cells. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2016, 51, 855–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.-G.; Acosta, T.J.; Tetsuka, M.; Berisha, B.; Matsui, M.; Schams, D.; Ohtani, M.; Miyamoto, A. Involvement of Angiopoietin-Tie System in Bovine Follicular Development and Atresia: Messenger RNA Expression in Theca Interna and Effect on Steroid Secretion. Biol. Reprod. 2003, 69, 2078–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugino, N.; Suzuki, T.; Sakata, A.; Miwa, I.; Asada, H.; Taketani, T.; Yamagata, Y.; Tamura, H. Angiogenesis in the Human Corpus Luteum: Changes in Expression of Angiopoietins in the Corpus Luteum throughout the Menstrual Cycle and in Early Pregnancy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 6141–6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, N.; Chen, H.; Davis-Smyth, T.; Gerber, H.P.; Nguyen, T.N.; Peers, D.; Chisholm, V.; Hillan, K.J.; Schwall, R.H. Vascular endothelial growth factor is essential for corpus luteum angiogenesis. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Ueno, H.; Shiuya, M. VEGF activates protein kinase C-dependent, but Ras-independent Raf-MEK-MAP kinase pathway for DNA synthesis in primary endothelial cells. Oncogene 1999, 18, 2221–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gecaj, R.M.; Schanzenbach, C.I.; Kirchner, B.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Riedmaier, I.; Tweedie-Cullen, R.Y.; Berisha, B. The Dynamics of microRNA Transcriptome in Bovine Corpus Luteum during Its Formation, Function, and Regression. Fron. Genet. 2017, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).