1. Introduction

Ethylene propylene diene copolymer rubber (EPDM) not only shows excellent flexion resistance, resilience and low temperature resistance, but also has good chemical structure stability. It is widely used in automotive industry, wire and cable, sealing materials and waterproof coiled materials and other fields. Although EPDM possesses excellent stability in chemical structure, it will still age to a certain extent under the action of external factors such as light, oxygen, heat and chemical media in the actual service and life process, which will degrade its performance and shorten the service life of products. Therefore, it is of great significance to study the aging law of EPDM.

The degradation process of rubbers is a complex and multi-stage mechanism that can be separated in several different steps [

1]. It can lead to changes in material properties, which are caused by physical and irreversible chemical processes, such as polymer chain breaking, cross-linking [

2,

3]. These processes substantially affect the technically relevant properties of polymer materials, such as strength, stiffness, toughness and modulus [

4]. Generally, the extent of aging-related changes is dependent on temperature and other aging conditions [

5]. For example, the cross-linking density depends mainly on the material-dependent oxygen absorption capacity, rate of diffusion and oxygen permeability [

6] as well as the vulcanization temperature, pressure and time. And aging of vulcanized rubber was shown to be related to a conversion of poly-sulfidic sulfur bridges to mono- and di-sulfidic sulfur bridges [

7].

EPDM rubber has been studied in thermal-oxygen aging [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], photo-oxygen aging [

13,

14], artificial weathering aging [

15], radiation aging [

16,

17] and medium aging [

18,

19]. Its research methods and test and characterization methods are diverse, such as dynamic mechanical property analysis, spectral analysis (Fourier infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy), energy spectrum analysis (X-ray electron spectroscopy, nuclear magnetic resonance), and thermal analysis (differential scanning calorimetry, thermogravimetric analysis), etc. However, most of them are limited to the research of EPM and EPDM rubber itself, and lack of research on the thermal oxygen aging of EPDM vulcanizates with antioxidant content and semi-efficient vulcanization system.

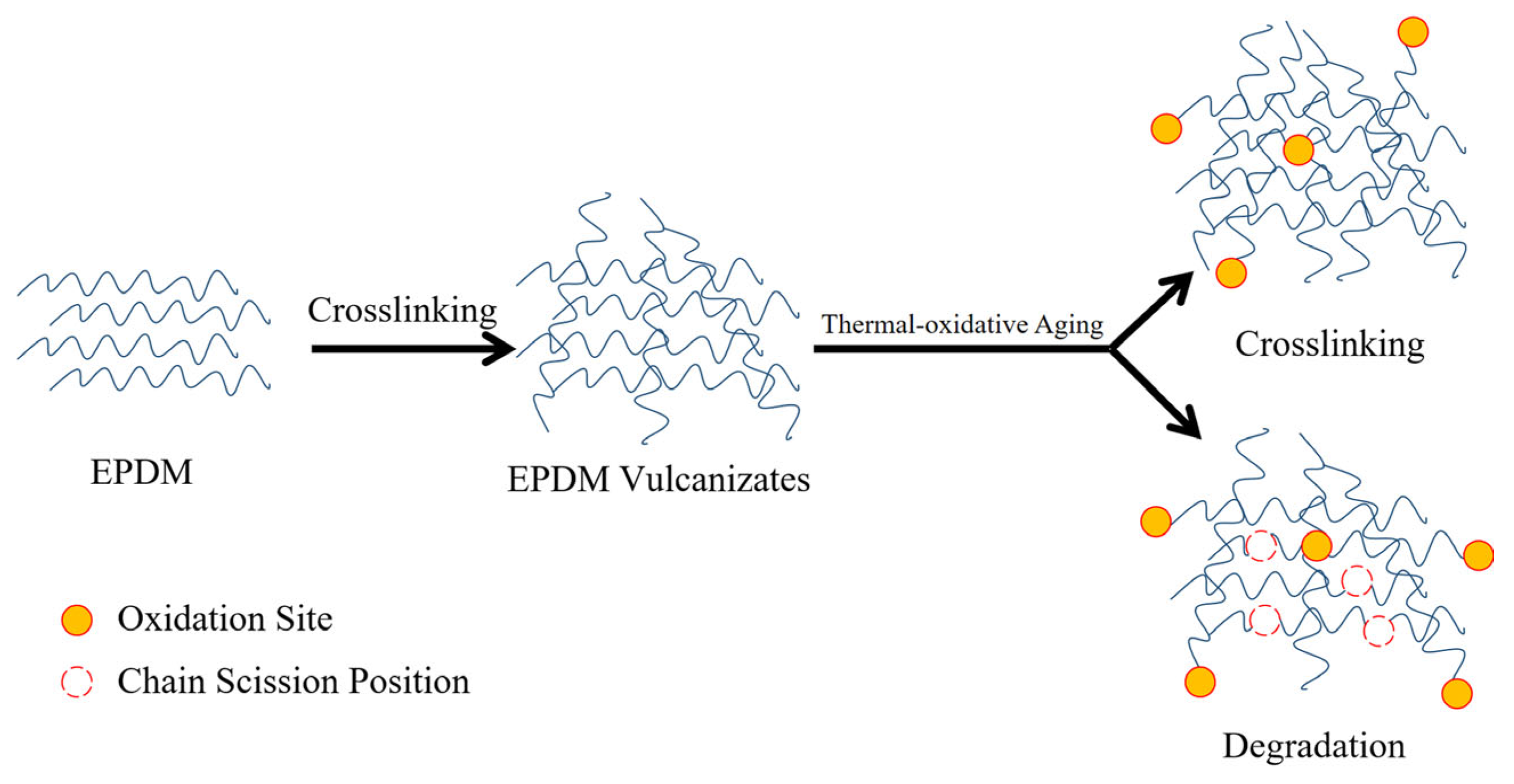

Here, in this paper, EPDM vulcanized rubber with a semi-effective vulcanization system is subjected to thermal and oxygen aging tests at 120℃(

Scheme 1). The effects of thermal-oxygen aging on the structure and properties of EPDM vulcanizates were studied in detail through physical properties, aging coefficient, surface properties, cross-linking density, Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and kinetics, and vulcanization characteristics of EPDM vulcanizates.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

EPDM Rubber(3760P) was purchased from Dow Chemical of the United States;carbon black(N330) was purchased from Cabot Corporation; naphthenic oil (KN4006) was purchased from China National Petroleum Corporation. Sulfur, zinc oxide (ZnO), stearic acid (SA), Tetramethylthiuram disulfide (TMTD), Poly(1,2-dihydro-2,2,4-trimethylquinoline) (RD), N-Isopropyl-N'-phenyl-p-phenylenediamine (4010NA), and they were all commercial industrial products.

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Preparation of EPDM vulcanizates

A two-stage mixing process was applied to EPDM vulcanizates by a Haake torque rheometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Poly Lab OS, Waltham, MA, USA) in this experiment. The speed of the internal mixer was set at 60 r/min and the initial temperature was 90℃. EPDM, ZnO, SA, carbon black (N330), and naphthenic oil were added in sequence. After dumping and pouring into the mixing mill, the two-stage mixing process was carried out. Later, sulfur and accelerator were added while the second temperature was 50℃. After storage for more than 16 hours, EPDM compound was vulcanized to the required samples with a plate vulcanizer (Huzhou Dong-fang Rubber Machinery Co., Ltd, XLB-400×400, Huzhou, Zhejiang, China) under the pressure of 15-20MPa and temperature of 170℃. The formulation of EPDM vulcanizates is listed in

Table 1.

2.2.2. Thermal-oxidative aging

According to ISO 188:2011 standard, the thermal-oxidative aging test was carried out on samples in the thermal oxygen aging test chamber (GOTECH TESTING MACHINES INC., GT-7017-E, Taipei, Taiwan, China). The settings of the apparatus are as follows: temperature of 120°C, temperature deviation of ±2℃, air flow rate of 0.5-1.5m/s and air exchange rate of 3-10 times/h. The aging time was 0h, 24h, 72h, 120h, 168h, and 336h, respectively.

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Vulcanization characteristics

The vulcanization characteristics are tested using a Vulcanizer (GOTECH TESTING MACHINES INC., GT-M2000-A, Taipei, Taiwan, China) according to GB/T 16584-1996 with a specimen weight of approximately 5g, a vulcanization temperature of 170℃ and a vulcanization time of 30min.

2.3.2. The cross-linking density

The rubber only swells and does not dissolve in the solvent, the mixing entropy increases and the swelling equilibrium is reached when the Gibbs free energy ΔGs is zero (Formula (1)).

where,

ΔGm,

ΔGel are mixing free energy, elastic free energy change respectively. In this experiment, the equilibrium swelling method was used to determine the crosslink density of EPDM vulcanized rubber. Assuming uniform deformation of the rubber in the solvent, the Flory-Rehner equation yields Formula (2). Cyclohexane was chosen as the solvent to determine the mass and density of EPDM before swelling, then put into the cyclohexane solvent, fully swelling, and test the mass after swelling every 24h until the difference between the two measurements was less than 0.01g, and calculate the crosslink density according to the following Equation (2).

where

ve: crosslink density;

V: molar volume of solvent;

v1: volume of rubber phase;

v2: volume fraction of rubber phase in vulcanizate;

v3: volume of solvent in rubber phase after swelling;

cyclohexane: interaction parameter between rubber and solvent: (

cyclohexane: 0.35144524);

ρ: density of rubber;

ρ1: density of reagent for swelling;

m1: mass of vulcanized rubber before swelling;

m2: mass of vulcanized rubber after swelling;

m3: mass of rubber phase.

2.3.3. Physical property

Tensile properties and hardness are measured using a AI-7000S electronic tension machine (GOTECH TESTING MACHINES INC., Taipei, Taiwan, China) and shore A hardness tester (GOTECH TESTING MACHINES INC., Taipei, Taiwan, China) according to ISO 37: 2005 and ISO 7619-2: 2004 respectively. The rate of change of performance is calculated according to the following Equation (6).

where,

P-rate of change of performance, %;

Xa-measured value of performance of the specimen after aging;

X0 -measured value of performance of the specimen before aging.

2.3.4. Water contact angle test

The water contact angle is measured with contact angle meter (Shanghai Zhongchen Digital Technology Equipment Co., Ltd, JC2000D2, Shanghai, China). The measured liquid is distilled water, and the test temperature and humidity are 15℃ and 50%, respectively.

2.3.5. Aging coefficient

Aging coefficient (

AC) [

20] is the standard for evaluating the thermal aging performance of rubber and can be expressed as:

In Equation (7), AC refers to the aging coefficient of rubber; σ1 and σ2 refer to the tensile strength (MPa) before and after aging; ε1 and ε2 represent the elongation at break (%) before and after aging respectively.

2.3.6. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer (FTIR) Analysis

The FTIR spectra of the polymer samples were obtained using a Nicolet IS 10 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The measurements of all of the samples were made with a signal average of 32 co-added scans and a resolution of 4 cm-1, 10 times of scanning, within a wave number range of 600~4000cm-1.

2.3.7. Thermal degradation kinetics

The thermogravimetric test was carried out in a N2 atmosphere. The initial temperature was 30℃, and the heating rate was 20℃/min. After heating to 600 ℃, a constant temperature shall be kept for 10 min. After that, it was switched to the air atmosphere with a heating rate of 20℃/min and a 10min constant temperature after heating to 800 ℃.

2.3.8. Thermal degradation kinetics

The thermogravimetric analysis plays an important role in the structure and thermal stability of polymers. The relationship between quality and temperature or time is tested under a certain flow rate atmosphere, so as to analyze the thermal stability and thermal decomposition of samples.

The degradation reaction equation is usually used to describe its kinetics.

Where, α refers to conversion rate,

k refers to the rate constant, while

f(α) depends on the reaction mechanism. The relationship between the rate constant

k and the reaction temperature

T can be expressed by Arrhenius equation:

Where

A is pre-factor (min

-1);

β is heating rate (℃/min);

T is temperature (K);

E is the activation energy (kJ/mol);

n is reaction order; and

R is molar gas constant (8.314472 J/(mol.k)). For the simple reaction equation

f(α).

The Equation (12) can be obtained by substituting Equations (10) and (11) into Equation (8):

Freeman-Carroll method [

21] is a method to calculate the activation energy by obtaining the difference between two points according to the reciprocal of the weight loss rate and temperature at several points on a thermogravimetric curve (TG curve). Assuming the heating rate at a constant

, Equation (13) can be obtained from the dynamic equation and Arrhenius equation:

By taking logarithms on both sides of Equation (13) and dividing them by

at the same time, Equation (14) can be obtained:

Adopting a temperature range of 450-480℃ and a temperature interval of 2℃, this paper performed the Freeman-Carroll operation. The activation energy E and the reaction order n were obtained respectively according to the slope and intercept of the fitting line of for ).

3. Results and Discussion

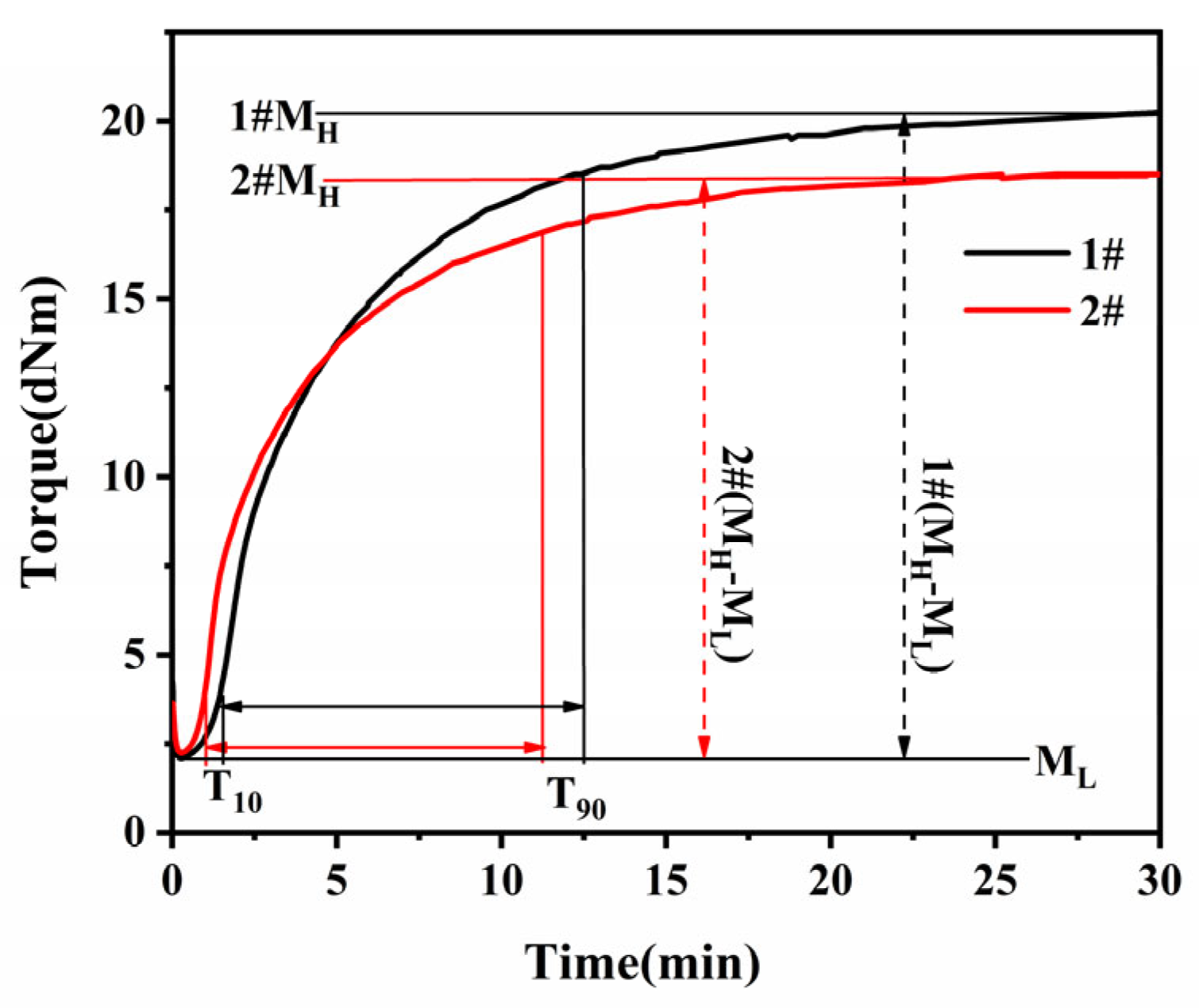

3.1 Vulcanization characteristics

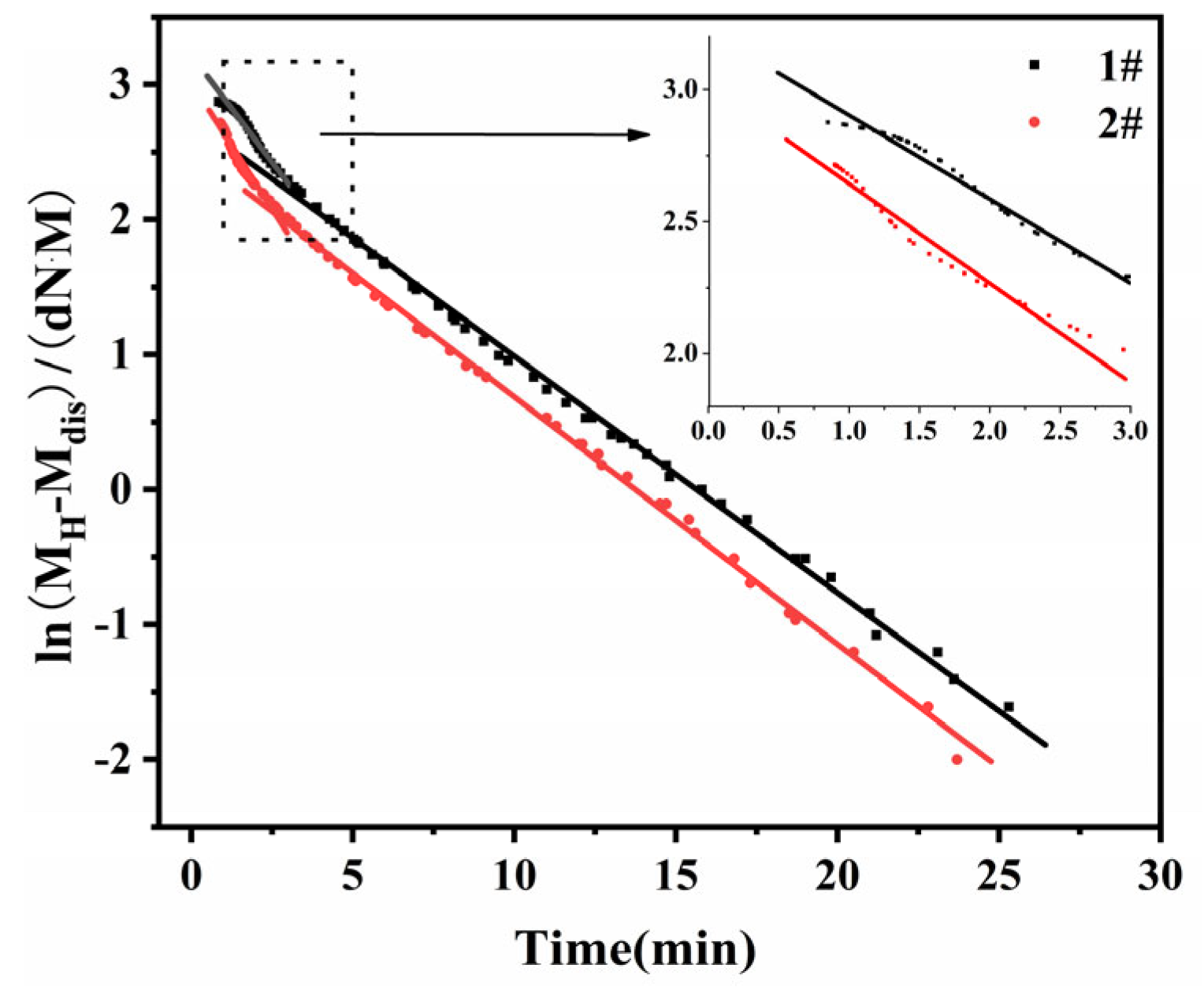

Figure 1 shows the vulcanization characteristics curve of EPDM. The formulation in this article uses a semi-effective vulcanization system (accelerator to sulfur dosage ratio of 1, which is between CV and EV). The resulting EPDM vulcanized rubber has both polysulphide bonds and a moderate amount of single and double sulfur cross-linked bonds. This combines the characteristics of both CV and EV vulcanization systems to improve the thermal and oxygen ageing and fatigue resistance of the vulcanized rubber. The change in torque during rubber vulcanization is proportional to the change in cross-linking density and the rate of change in torque can be used to characterise the rate of vulcanization. The equation for the rate of vulcanization can be expressed as

Where, MH, maximum torque; Mt, torque at vulcanization time t; K, rate constant; n, number of reaction stages.

According to the reaction model for the coking phase derived by Coran [

22], the reaction equation for the vulcanization phase can be expressed as in equation (16).

In addition, the reaction during the scorch period is not a primary reaction, but rather the true primary reaction begins when the rate of change of the torque reaches a maximum, and the sulphation kinetics can be expressed as

In this case,

tdis, the moment when the rate of change of torque reaches its maximum, is plotted against (

t-tdis) by

ln(MH-Mt) (

Figure 2).

K and

lnA can be obtained from the slope and intercept, respectively.

As the sulphidation process after coking is usually divided into two stages, a linear fit to the data was performed separately and the fit was also found to be a smooth straight line, consistent with a first order kinetic reaction. This sulphidation process can therefore be divided into two first order kinetic reactions.

Due to the addition of antioxidant,

T10,

Tdis are shortened, indicating that the start reaction time is earlier, the reaction is easier to carry out; vulcanization rate

K,

CRI value increases, the vulcanization speed becomes faster, but the crosslink density is lower than sample 1, EPDM vulcanization rubber characteristics data as shown in

Table 2.

3.2. Physical properties and cross-linking density

Figure 3 shows that physical properties and cross-linking density changes of EPDM vulcanizates after aging. The specific data of changes in the performance of EPDM vulcanizates after aging was shown in

Table 3. It can be seen that the tensile strength, hardness, and cross-linking density of two EPDM vulcanizates gradually increase but the elongation at break decreases with increasing aging time. Basically, EPDM vulcanizates would continue to be cross-linked at 120 ℃, the conformation transition of the polymer chain was constrained and the flexibility was weakened, which lead to the increasing tensile strength and surface hardness [

23].

The oxidative degradation of the carbon-carbon backbone during the thermal-oxidative aging of EPDM vulcanizates increases the polarity and decreases the flexibility, while aging produces more silver lines and increases the number of weak points leading to lower elongation at break.

The elongation at break of EPDM vulcanizate with antioxidant is higher than that of sample without antioxidant, while the tensile strength, cross-linking density and hardness are slightly lower than that of sample 1#. It is indicating that antioxidant has an effect on the vulcanization characteristics, which can inhibit the generation of cross-linking network structure, and make the macromolecular chain have a larger free volume. The degradation reaction and cross-linking reaction of EPDM vulcanizates are competitive reactions during thermal-oxidative aging. Antioxidants increase the imperfection degree of cross-linking structure, at the same time, chain breaking and oxidation reaction play a leading role with increasing thermal-oxygen aging time.

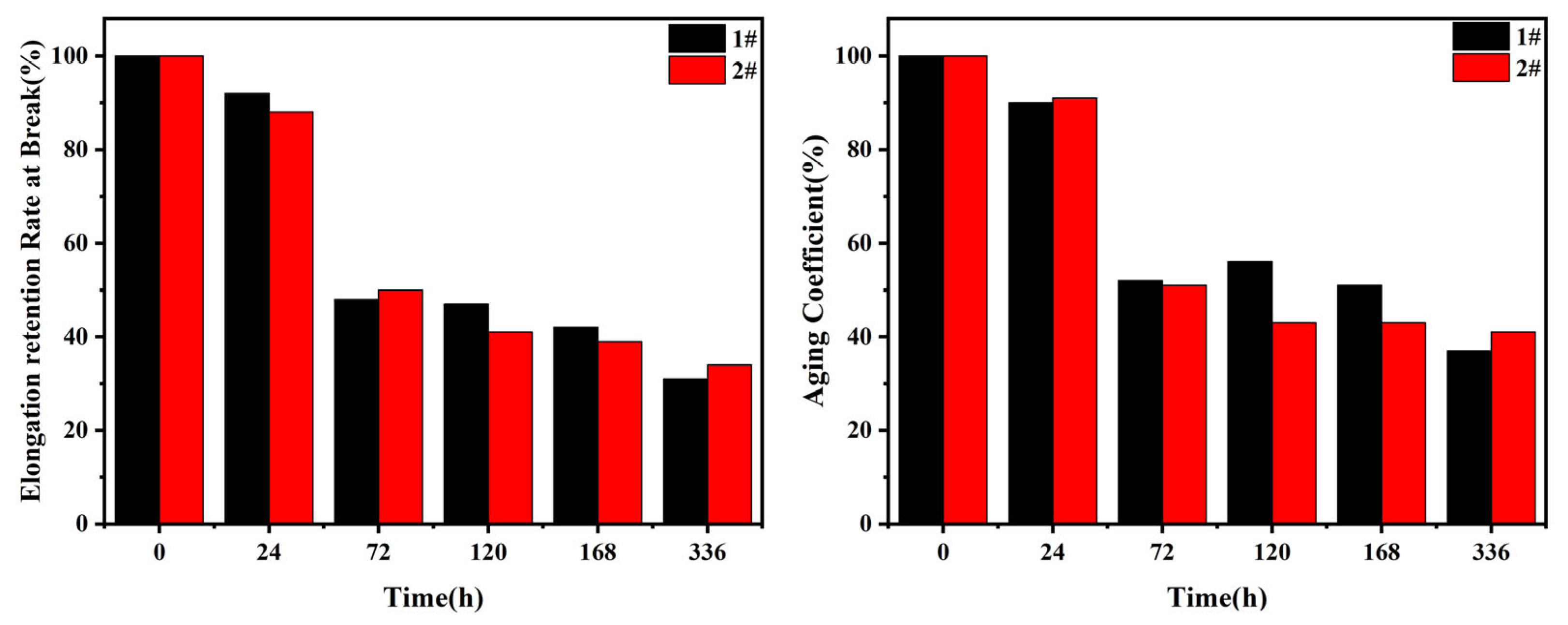

3.3 Aging coefficient and retention

The aging coefficient (

AC) is obtained from the relationship between physical and mechanical properties (e.g. tensile strength, elongation) before and after thermal and oxygen aging. It is usually a key indicator used to evaluate the overall performance of rubber aging.

Figure 4 shows the changes of aging coefficient and tearing elongation retention at break of EPDM vulcanizates with aging time. The specific data are shown in

Table 4. The aging coefficient and elongation retention rate of EPDM vulcanized rubber with the addition of antioxidant are larger than those of the sample 1# without the addition of antioxidant. It means that the addition of antioxidant obviously improves the retention rate of the macro physical properties of EPDM vulcanized rubber with thermal and oxygen aging.

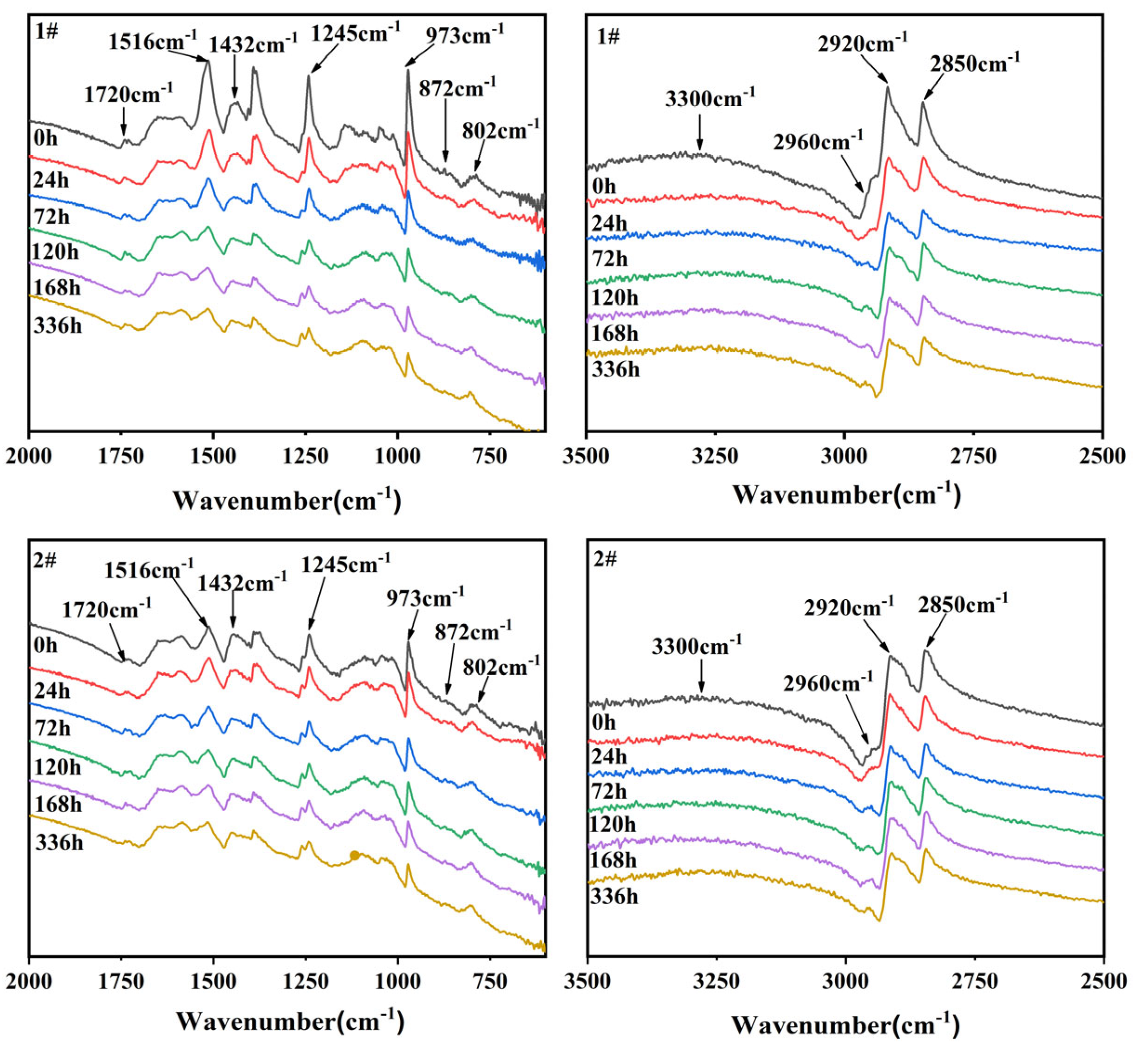

3.4 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer (FTIR) Analysis

In this paper, the structure of EPDM vulcanizates was analyzed by ATR total reflection method after aging, which is a simple and efficient method for analysing the structure of EPDM vulcanized rubber after aging. The change of the infrared spectrum of EPDM vulcanizates are showed by

Figure 5 with aging time. The infrared absorption peaks of the two EPDM vulcanizates at different wavelengths show the same change rule.

The peak at 3300cm

-1 was the stretching vibration peak of the hydroxyl group which is attributed to the extended oxidation group of -OH (alcohol, hydroperoxide and carboxylic acid) [

24]. As a result of thermal oxidative degradation, which content increased with with increasing aging time. For pure EPDM, the peaks between 2800cm

-1 and 3000 cm

-1 are related to CH3, CH2 and CH [

25]. The peak at 2850cm

-1 and 2920cm

-1 belonged to symmetric stretching vibration and asymmetric stretching vibration of (-CH2-) group respectively [

26], which decreases with aging time. The peak at 2960cm

-1 reflects the asymmetric stretching vibration of methyl [

27,

28,

29,

30]. Its content increases with the extension of the aging time, indicating a chain rupturing reaction of the EPDM structure.

The peak at 1720 cm

-1 was the characteristic peak of carbonyl, in which the peak area is a measure of the oxidative degradation degree of the polymer [

31,

32,

33]. As carbonyl was the main product of oxidative degradation of EPDM vulcanizates, the carbonyl index can be determined, namely, the value of carbonyl sulfide line strength at 1720 cm

-1 divided by methylene line strength at 1432 cm

-1[

34]. Carbonyl content and carbonyl index were shown in

Table 5. The upward trend of carbonyl content and carbonyl index with increasing aging time implied that EPDM vulcanizates were gradually oxidized and degraded.

The carbonyl content and carbonyl index of the sample 2# with the addition of antioxidant are smaller than those of the 1# EPDM vulcanized rubber, so it can be inferred that the addition of RD and 4010NA antioxidants can reduce the oxidation reaction on the surface of EPDM vulcanized rubber to a certain extent and improve the heat and oxygen aging resistance.

In the IR absorption region of 1500-800 cm

-1, the peak at 1432 cm

-1 was the -CH2- shear vibration mode of propylene unit of EPDM and CH band lossed due to oxidative degradation [

35]. The peak at 1245cm

-1 was caused by macro-molecular skeleton vibration, the content decreased with increasing aging time also implied that thermal oxygen aging would lead to the fracture of the macro-molecular skeleton.

The peaks at 872 cm

-1 and 802 cm

-1 were the deformation vibration of the typical unsaturated zone C=C-H of the diene part, and 973cm

-1 was the shear deformation vibration of C-H in the third monomer with double bond C=C-H. Its content increased firstly and then decreased with the increasing aging time, which was due to cross-linking firstly, and then breakage loss of double bonds caused by the thermal oxidative aging degradation [

36,

37]. The carbonyl and ester groups were formed and the unsaturation of the third monomer decreased rapidly, which indicated that chain branching [

38] and cross-linking reactions [

39] occur simultaneously during the aging process of EPDM vulcanizates. Therefore, thermal-oxidation aging of EPDM vulcanizates can be seen as a process of breaking of the main chain and oxidation.

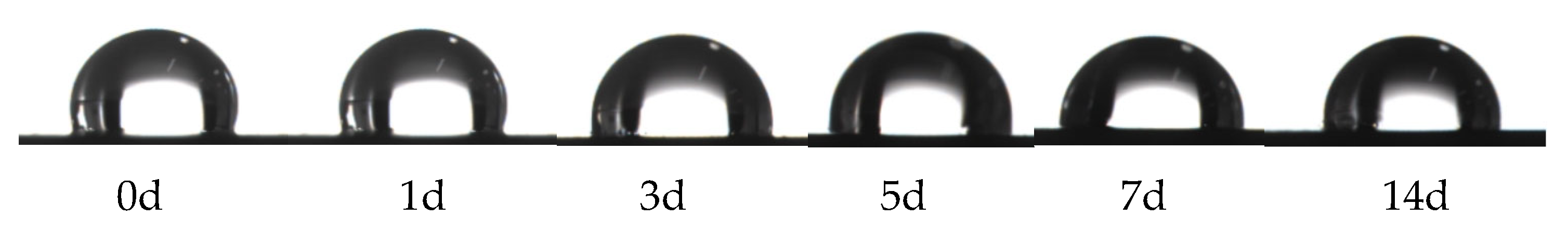

3.5. Surface property

Contact angle is the angle between the tangent line of the gas-liquid interface and the solid-liquid junction line made by the liquid at the intersection of gas, liquid and solid phases after the formation of the Young-Laplace arc on the solid surface. The contact angle is an important parameter to measure the wetting performance of the liquid on the surface of the material, and can express the change of polarity, hydrophilicity and surface energy of the material surface.

Figure 7 shows the variation of contact angle of EPDM vulcanized rubber with aging time, the specific data is shown in

Table 6, it can be seen that the contact angle of 2 types of EPDM vulcanized rubber shows a gradual decrease with the increase of aging time. The reason is that the main chain of EPDM vulcanized rubber is broken and oxidised, and the oxygen-containing groups such as carbonyl and carboxyl groups on the surface gradually increase. The number of carbon atoms in the main chain decreases and the water solubility gradually increases, which shows that the hydrophilic energy gradually increases and the contact angle decreases. As the aging time increases, the oxidative degradation of the main chain of EPDM further intensifies, leading to an increase in the carbonyl index, and thus the contact angle decreases.

The contact angle of sample 2# with the addition of antioxidant was larger than that of sample 1. This is probably due to the fact that the addition of the antioxidant affects the crosslinking reaction and network of the EPDM vulcanized rubber while reducing the oxidation reaction during the vulcanization process. Further, the oxidative degradation of the EPDM vulcanized rubber surface is more intense as the aging time increases. It is suggested that the addition of antioxidants RD and 4010NA can significantly reduce the generation of oxidation groups on the surface and thus the carbonyl index.

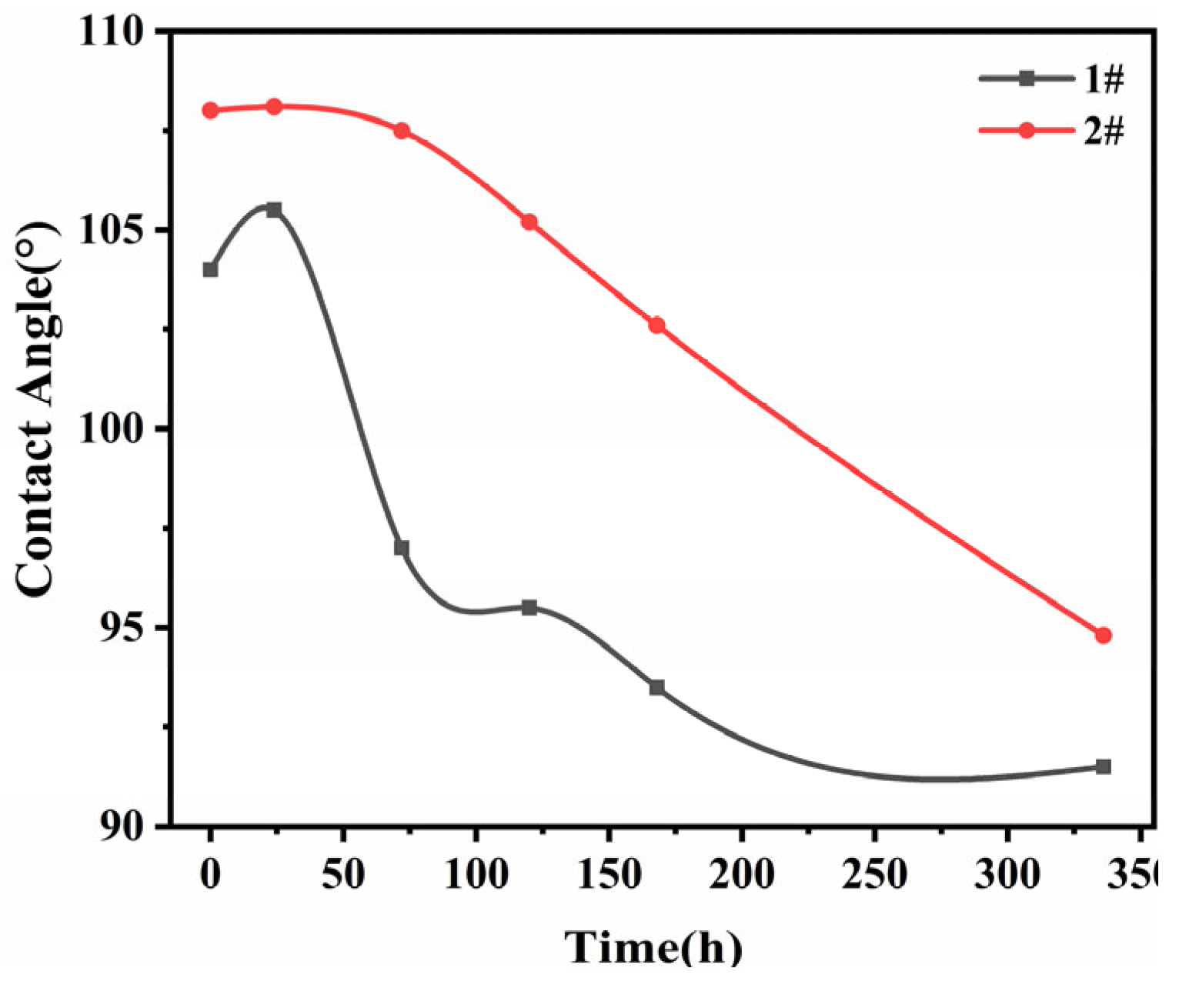

3.6 Thermal degradation behavior and kinetic

The thermal stability of materials can be analyzed by TGA, which can reveal the relationship between the mass of the sample and temperature or time under a certain flow rate atmosphere. The TGA test is the change of sample quality at the same heating rate and isothermal time. The TG curve can not only show the different stages of thermal decomposition of the sample, but also allows qualitatively and quantitatively analyze the composition change after aging. The DTG curve represents the weight loss rate, which can be derived from the TG curve, and the two curves correspond. The decomposition stage, decomposition temperature, decomposition rate, thermal stability, thermal decomposition activation energy of polymer materials can be obtained by the thermogravimetric analysis.

Figure 8 shows the TG/DTG curve of EPDM vulcanizate after aging.

According to the TG/DTG curve in

Figure 8, the thermal weightlessness of EPDM vulcanizates can be divided into three stages. The specific data was listed in

Table 7. It can be seen that the change trend of the initial weight-loss temperature in the first stage gradually reduced with increasing aging time; and were not change with time in the second and third stages. The initial weight-loss temperature in the first stage also represents that its thermal stability gradually decreases. The weight-loss rate of EPDM vulcanizates in the first stage was gradually reduced with increasing aging time. The major losses were highly volatile substances (plasticizers, accelerators, water vapor, etc.), whose aging were accompanied by the quality degradation in the first stage at 120℃. In the second stage, medium volatile substances (EPDM rubber) losed away largely. Some scholars [

40] had tracked the degradation and pyrolysis process of EPDM by gas chromatography to confirmed that the main products were CO

2, H

2O, CO, CH

4, and C

2H

6. combustible substances (carbon black, etc.) burn slowly in the third stage. The remaining materials were some mineral additives, such as ZnO.

The peak of the first weight-loss temperature increased with increasing aging time, while the peak of weight-loss temperature in the second and third stage did not change significantly. This was due to the loss of plasticizers, cross-linking and degradation (the competitive reaction), which were caused by the decomposition of the carbon main chain that affected the free volume of the material during the thermal oxidative aging process of EPDM vulcanizates. The degradation is attributed to the oxidative degradation of the main chain of crosslinked EPDM in the second stage [

41].

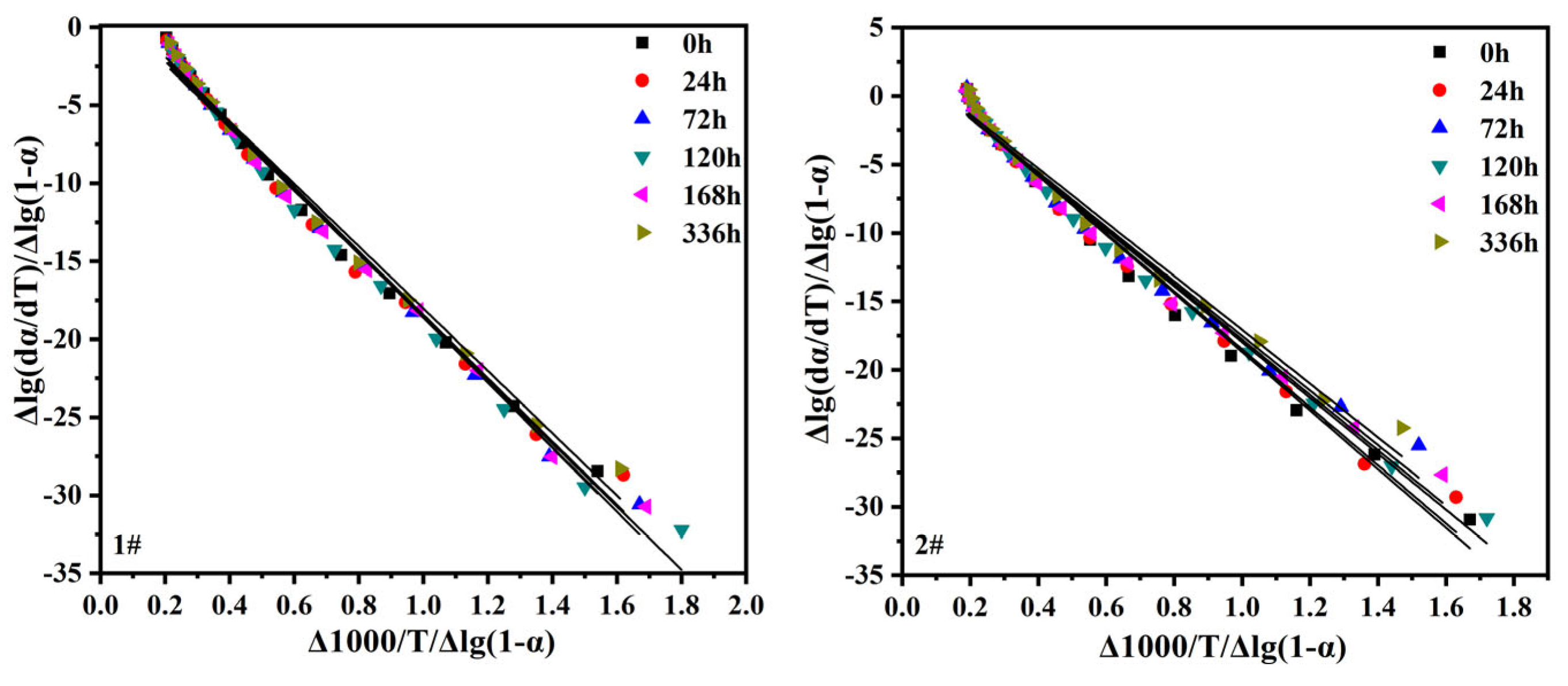

In this paper, the temperature interval 450-480℃ was chosen to calculate the heat drop activation energy. This interval is mainly attributed to the EPDM main chain structure, where the weight loss reaction is relatively intense. The activation energy E and the number of reaction steps n can be obtained from the slope and intercept of the straight line, respectively, by the Freeman-Carroll method for graphing (

Figure 9).

Table 8 shows the data of the thermal analysis of the TG/DTG curve of EPDM vulcanization rubber ageing.

The results show that the degradation process of EPDM is complex and its degradation reaction is not a simple stepwise reaction but a random degradation process [

42]. The degradation of EPDM follows the Avrami-Erofeev two-dimensional nucleation model or random chain breaking mechanism [

43]. The activation energy E of thermal degradation of the EPDM vulcanized rubber backbone structure tends to decrease with increasing thermal and oxygen aging time. This is due to the dual effect of chain breakage and cross-linking occurring simultaneously during thermal oxygen aging, with EPDM vulcanized rubber continuing to cross-link at 120℃ under thermal oxygen [

35]. The crosslink density gradually increases leading to a relatively smooth decrease in the magnitude of its thermal degradation activation energy. However, as the aging time increases, the oxidative degradation reaction of the EPDM backbone dominates and the activation energy continuously decreases [

44,

45].

A comparison of the results from the 2# (with antioxidant) and 1# (without antioxidant) samples shows that the addition of antioxidant increases the EPDM vulcanization starting weight loss temperature and the first stage weight loss peak temperature. At the same time, the number of reaction stages is reduced, indicating that the addition of antioxidant can reduce the thermal degradation reaction and thus inhibit the oxidation effect. This is generally consistent with the macroscopic physical and mechanical properties. The activation energy of thermal degradation of sample 2 is smaller than that of sample 1. This is due to the competition between degradation and cross-linking of the EPDM backbone. The antioxidant enhances the crosslinking rate but does not help to form a complete crosslinking network of the EPDM curing rubber, thus reducing the stability of the carbon-carbon backbone. Herein, the degradation reaction plays a major role in reducing the thermal degradation activation energy.

4. Conclusions

The structure and properties of EPDM vulcanizates with two kinds of semi-efficient vulcanization system before and after thermal-oxidative aging were investigated in detail, including vulcanization characteristics, macroscopic physical properties, surface properties, thermogravimetric behavior and kinetics, and so on.

The vulcanization characteristics showed that the vulcanization process of EPDM vulcanizates consisted of two first-order kinetic reaction stages. Antioxidants can promote the cross-linking reaction and improve the cross-linking speed, but cannot form perfect cross-linking network structures. With increasing aging time, EPDM vulcanizates can continue to cross-link so as that the conformational transformation of polymer chain is constrained, and the flexibility is weakened. And finally, the macroscopic physical properties (such as strength, elongation, hardness, etc.) are affected. The antioxidant can significantly improve the aging coefficient and macroscopic physical retention of EPDM vulcanizates, which can inhibit cross-linking density and have a larger free volume, and thus promote the retention of elongation and hardness.

The FTIR shows that the infrared absorption peaks of two EPDM vulcanizates at different wavelengths have the same changes. It is implied that the oxidation and degradation of the surface intensifies as the aging time increases, and the carbonyl content and carbonyl index gradually increase. This phenomenon is demonstrated macroscopically as an increase in contact angle. Antioxidants can reduce the degree of oxidation and degradation of the surface of EPDM vulcanizates, and improve the thermal oxygen aging properties of the surface.

The thermal degradation behavior and kinetics displayed that the thermal decomposition of two EPDM vulcanizates can be divided into three stages. The 2# sample with the addition of the high boiling-point antioxidant greatly increased the initial weight-loss temperature and the peak of the first weight-loss temperature in the first degradation stage. The kinetic study of the backbone of EPDM vulcanizates under the temperature range of 450-480℃ showed that the antioxidant can reduce the reaction order and promoting the formation of incomplete cross-linked network structure, which intensifies the degradation reaction and reduces the thermal degradation activation energy of the backbone.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Q.-C.H., Q.C, P.-R.S., X.-Y.G., J.-Y.C. and Y.-X.Z.; The first draft of the manuscript was written by Q.-C.H. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the financial support from the Shandong Province Key Research and Development Plan of China (Public Welfare Project 2019GGX102068) and the Program Fund of Non-Metallic Excellence and Innovation Center for Building Materials, 2023TDA2-2, and Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020MB041).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Available data are presented in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Y, Navarro, Torrejon, et al. Consumption and reaction mechanisms of antioxidants during thermal oxidative aging. KGK rubberpoint 2012, 65, 25-31.

- Azura A R, Ghazali S, Mariatti M. Effects of the filler loading and aging time on the mechanical and electrical conductivity properties of carbon black filled natural rubber. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2008, 110, 747-752.

- Nakazono T , Ozaki A , Matsumoto A . Phase separation and thermal aging behavior of styrene-butadiene rubber vulcanizates using liquid polymers as plasticizers studied by differential scanning calorimetry and dynamic mechanical spectroscopy. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2011, 120, 434-440.

- 4Tomer N S , Delor-Jestin F , Singh R P , et al. Cross-linking assessment after accelerated ageing of ethylene propylene diene monomer rubber. Polymer Degradation & Stability 2007, 92, 457-463.

- Osswald S L B . Influence of different types of antioxidants on the aging behavior of carbon-black filled NR and SBR vulcanizates. Polymer Testing, 2019, 79.

- Baldwin J M , Bauer D R , Ellwood K R . Rubber aging in tires. Part 1: Field results. Polymer Degradation & Stability 2007, 92, 103-109.

- Chakraborty S , Kar S , Dasgupta S , et al. Effect of Ozone, Thermo, and Thermo-oxidative Aging on the Physical Property of Styrene Butadiene Rubber-Organoclay Nanocomposites. Journal of Elastomers & Plastics 2010, 42, 443-452.

- Wen H, Wang M, Luo S, et al. Aramid fiber reinforced EPDM microcellular foams: Influence of the aramid fiber content on rheological behavior, mechanical properties, thermal properties, and cellular structure. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2021, 50531.

- Blivet C, Larché J, Israli Y, et al. Thermal oxidation of cross-linked PE and EPR used as insulation materials: Multi-scale correlation over a wide range of temperatures. Polymer Testing 2021, 93, 106913.

- Bhattacharya A B, Chatterjee T, Naskar K. Dynamically vulcanized blends of UHM-EPDM and polypropylene: Role of nano-fillers improving thermal and rheological properties. Materials Today Communications 2020, 101486.

- Tomer N S, Delor-Jestin F, Singh R P, et al. Cross-linking assessment after accelerated ageing of ethylene propylene diene monomer rubber. Polymer Degradation & Stability 2007, 92, 457-63.

- Ma H, He J , Li X , et al. High thermal stability and low flammability for Ethylene-Vinyl acetate Monomer/Ethylene-Propylene-Diene Monomer by incorporating macromolecular charring agent. Polymers for advanced technologies 2021, 6, 32.

- Nordin R, Latiff N, Yusof R, et al. Effect of several commercial rubber as substrates for zinc oxide in the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue under visible irradiation. Express Polymer Letters 2020, 14, 838-847.

- Wang W, Qu B. Photo-and thermo-oxidative degradation of photocrosslinked ethylene–propylene–diene terpolymer. Polymer Degradation & Stability 2003, 81, 531-537.

- Aimura Y, Wada N. Reference materials for weathering tests on rubber products. Polymer Testing 2006, 25, 166-175.

- Barala S S, Manda V, Jodha A S, et al. Ethylene-propylene diene monomer-based polymer composite for attenuation of high energy radiations. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2020,138, 50334.

- Zaharescu T, Mateescu C, Dima A D, et al. Evaluation of thermal and radiation stability of EPDM in the presence of some algal powders. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2020, 327-336.

- Yue T, Liu P, Zhao H, et al. Chain dynamics evolution of ethylene-propylene-diene monomer in response to hot humid and salt fog environment. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2021, 50742.

- Mokhtari S, Mohammadi F, Nekoomanesh M. Surface modification of PP-EPDM used in automotive industry by mediated electrochemical oxidation. Iranian Polymer Journal 2016, 25, 309-320.

- Zhao ZhigangTang Qingguo, Zeng Shaogang, et al. Effect of Sepiolite on Thermo-oxidative Stability Performance of Reinforced EPDM. Journal of Materials Research 2017, 31, 867-873.

- Freeman E S, Carroll B. The Application of Thermoanalytical Techniques to Reaction Kinetics: The Thermogravimetric Evaluation of the Kinetics of the Decomposition of Calcium Oxalate Monohydrate. Journal of Physical Chemistry 1958, 62, 394-397.

- ALBANO C, MARIANELLA H, et al. Characterization of NBR/bentonite composites: Vulcanization kinetics and rheometric and mechanical properties. Polymer Bulletin 2011, 67, 653-667.

- omer N S, Delor-Jestin F, Singh R P, et al. Cross-linking assessment after accelerated ageing of ethylene propylene diene monomer rubber. Polymer Degradation & Stability 2007, 92, 457-63.

- Firat Hacioglu, Tonguc Ozdemir, Cavdar Sada, et al. Possible use of EPDM in radioactive waste disposal: Long term low dose rate and short term high dose rate irradiation in aquatic and atmospheric environment. Radiation Physics & Chemistry 2013, 83, 122-130.

- Chen W L, Chen H C, Tian J Z, et al. Chemical degradation of five elastomeric seal materials in a simulated and an accelerated PEM fuel cell environment. Journal of Power Sources 2011, 196, 1955-1966.

- Boukezzi L, Boubakeur A, Laurent C, et al. Observations on structural changes under thermal ageing of cross-linked polyethylene used as power cables insulation. Iranian Polymer Journal 2008, 17, 611-624.

- Zhao YX, Ma YJ, Yao W. Styrene-Assisted Grafting of Maleic Anhydride Onto Isotactic Poly butene-1. Polymer engineering and science 2011, 51 , 2483-2489.

- Zhao YX, Du YJ, Han L, et al. Study on DTBP initiated MAH onto polybutene-1 with melt-grafting. Journal of Polymer Engineering 2012, 32 , 567-574.

- Zhou YF, Zhao YX, Chen JY, et al. Grafting of glycidyl methacrylate onto isotactic polybutene-1 initiated by di-tert-butyl peroxide. Journal of Elastomers & Plastics 2015, 47, 262-276.

- Zhao YX, Chen JY, Han L, et al. Nonisothermal crystallization kinetics of polybutene-1 containing nucleating agent with acid amides structure. Journal of Polymer Engineering 2014, 34, 53-58.

- Kumar A, Commereuc S, Verney V. Ageing of elastomers: a molecular approach based on rheological characterization. Polymer Degradation & Stability 2004, 85, 751-757.

- Zhao Q, Li X, Jin G. Surface degradation of ethylene-propylene-diene monomer (EPDM) containing 5-ethylidene-2-norbornene (ENB) as diene in artificial weathering environment. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2008, 93, 692-699.

- Zhao Q, Li X, Gao J. Aging of ethylene-propylene-diene monomer (EPDM) in artificial weathering environment. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2007, 92, 1841-1846.

- Snijders E A, Boersma A, Baarle B V, et al. Effect of dicumyl peroxide cross-linking on the UV stability of ethylene-propylene-diene (EPDM) elastomers containing 5-ethylene-2-norbornene (ENB). Polymer Degradation and Stability 2005, 89, 484-491.

- Sun Y, Luo S, Watkins K, et al. Electrical approach to monitor the thermal oxidation aging of carbon black filled ethylene propylene rubber. Polymer Degradation & Stability 2004, 86, 209-215.

- Ozdemir T. Gamma irradiation degradation/modification of 5-ethylidene 2-norbornene (ENB)-based ethylene propylene diene rubber (EPDM) depending on ENB content of EPDM and type/content of peroxides used in vulcanization. Radiation Physics & Chemistry 2008, 77, 787-793.

- Delor F, Teissedre G, Baba M, et al. Ageing of EPDM-2. Role of hydroperoxides in photo-and thermo-oxidation. Polymer Degradation & Stability 1998, 60, 321-331.

- Bhowmick A K, Konar J, Kole S, et al. Surface properties of EPDM, silicone rubber, and their blend during aging. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 1995, 57, 631-637.

- Palmas P, Ca Mpion L L, Bourgeoisat C, et al. Curing and thermal ageing of elastomers as studied by 1H broadband and 13C high-resolution solid-state NMR. Polymer 2001, 42, 7675-7683.

- Tomer N S, Delor-Jestin F, Singh R P, et al. Cross-linking assessment after accelerated ageing of ethylene propylene diene monomer rubber. Polymer Degradation & Stability 2007, 92, 457-63.

- Zaharescu T, Podinǎ C. Radiochemical stability of EPDM. Polymer Testing 2001, 20, 141-149.

- Gamlin C, Dutta N, Roy-Choudhury N, et al. Influence of ethylene–propylene ratio on the thermal degradation behaviour of EPDM elastomers. Thermochimica Acta 2001, 367, 185-193.

- Gamlin C D, Dutta N K, Choudhury N R. Mechanism and kinetics of the isothermal thermodegradation of ethylene-propylene-diene (EPDM) elastomers - ScienceDirect. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2003, 80, 525-531.

- Zaharescu T, Podinǎ C. Radiochemical stability of EPDM. Polymer Testing 2001, 20, 141-149.

- Assink R A, Gillen K T, Sanderson B. Monitoring the degradation of a thermally aged EPDM terpolymer by 1H NMR relaxation measurements of solvent swelled samples. Polymer 2002, 43, 1349-1355.

Scheme 1.

The cross-linking and thermal-oxidative aging process of EPDM vulcanizates.

Scheme 1.

The cross-linking and thermal-oxidative aging process of EPDM vulcanizates.

Figure 1.

Vulcanization Curves of EPDM vulcanizates: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant.

Figure 1.

Vulcanization Curves of EPDM vulcanizates: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant.

Figure 2.

Relationship between ln(MH–Mt) and t of EPDM vulcanizates: (1#)without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant.

Figure 2.

Relationship between ln(MH–Mt) and t of EPDM vulcanizates: (1#)without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant.

Figure 3.

Changes in performance of EPDM vulcanizates after aging: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant.

Figure 3.

Changes in performance of EPDM vulcanizates after aging: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant.

Figure 4.

Elongation retention at break and AC of EPDM vulcanizates after aging: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant.

Figure 4.

Elongation retention at break and AC of EPDM vulcanizates after aging: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant.

Figure 5.

Infrared spectra of sample EPDM vulcanizates: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant

Figure 5.

Infrared spectra of sample EPDM vulcanizates: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant

Figure 6.

Contact angle of 1# EPDM vulcanizates.

Figure 6.

Contact angle of 1# EPDM vulcanizates.

Figure 7.

Contact angle of EPDM vulcanizates after aging: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant.

Figure 7.

Contact angle of EPDM vulcanizates after aging: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant.

Figure 8.

TG/DTG curve of EPDM vulcanizates after aging: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#)with antioxidant

Figure 8.

TG/DTG curve of EPDM vulcanizates after aging: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#)with antioxidant

Figure 9.

Relationship between △lg(dα/dT)/△lg(1-α) and △1000/T/△lg(1-α) of EPDM vulcanizates after aging: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant

Figure 9.

Relationship between △lg(dα/dT)/△lg(1-α) and △1000/T/△lg(1-α) of EPDM vulcanizates after aging: (1#) without antioxidant; (2#) with antioxidant

Table 1.

Formulation of EPDM vulcanizates

Table 1.

Formulation of EPDM vulcanizates

| Samples |

EPDM wt % |

N330

wt % |

Sulfur

wt % |

TMTD

wt % |

ZnO

wt % |

SA

wt % |

KN4006

wt % |

RD

wt % |

4010NA

wt % |

| 1# |

100 |

100 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

5 |

1 |

70 |

- |

- |

| 2# |

100 |

100 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

5 |

1 |

70 |

1 |

2 |

Table 2.

The Data of vulcanization characteristics.

Table 2.

The Data of vulcanization characteristics.

| sample |

MH/(N·M) |

ML/(N·M) |

MH-ML/(N·M) |

T10/(min) |

T90/(min) |

CRI/(min-1) |

Tdis/(min) |

K |

R |

| 1# |

20.29 |

2.09 |

18.2 |

1.46 |

12.23 |

9.07 |

1.89 |

0.23*/0.17 |

0.990*/0.998 |

| 2# |

18.55 |

2.25 |

16.3 |

0.98 |

11.32 |

9.57 |

1.19 |

0.27*/0.18 |

0.987*/0.997 |

Table 3.

Changes in performance of EPDM vulcanizates after aging.

Table 3.

Changes in performance of EPDM vulcanizates after aging.

| Aging time/h |

Hardness |

Tensile Strength /MPa |

Elongation at Break /% |

Cross-linking Density |

| 1# |

2# |

1# |

2# |

1# |

2# |

1# |

2# |

| 0 |

65 |

63 |

16.22 |

16.55 |

490.84 |

561.17 |

1.24×10-4

|

1.11×10-4

|

| 24 |

72 |

73 |

16.51 |

16.83 |

452.52 |

493.58 |

1.31×10-4

|

1.19×10-4

|

| 72 |

85 |

85 |

18.24 |

16.86 |

239.86 |

358.80 |

1.68×10-4

|

1.45×10-4

|

| 120 |

88 |

87 |

19.77 |

17.03 |

232.94 |

329.11 |

1.77×10-4

|

1.69×10-4

|

| 168 |

90 |

88 |

19.20 |

17.52 |

209.55 |

295.17 |

1.81×10-4

|

1.75×10-4

|

| 336 |

90 |

90 |

19.69 |

19.62 |

152.53 |

258.21 |

2.06×10-4

|

2.02×10-4

|

Table 4.

Performance of EPDM vulcanizates after aging

Table 4.

Performance of EPDM vulcanizates after aging

| Aging time/h |

0 |

24 |

72 |

120 |

168 |

336 |

| Elongation retention at break/% |

1# |

100 |

92 |

48 |

47 |

42 |

31 |

| 2# |

100 |

88 |

64 |

59 |

53 |

46 |

| AC/% |

1# |

100 |

90 |

52 |

56 |

51 |

37 |

| 2# |

100 |

90 |

65 |

60 |

56 |

54 |

Table 5.

Changes in the peak area of different groups of EPDM vulcanizates after aging.

Table 5.

Changes in the peak area of different groups of EPDM vulcanizates after aging.

| Aging time/h |

3300cm-1

|

2960cm-1

|

1720cm-1

|

1516cm-1

|

1432cm-1

|

1245cm-1

|

1# 1

|

2# 1

|

| 0 |

200.17 |

1.46 |

2.42 |

40.59 |

1.16 |

24.75 |

2.086 |

0.638 |

| 24 |

204.51 |

2.11 |

2.71 |

33.6 |

1.13 |

25.14 |

2.398 |

0.638 |

| 72 |

209.6 |

3.12 |

3.07 |

34.39 |

1.28 |

23.04 |

2.398 |

0.728 |

| 120 |

213.87 |

3.17 |

3.19 |

21.46 |

1.32 |

19.97 |

2.417 |

0.815 |

| 168 |

220.48 |

3.39 |

3.77 |

21.06 |

1.48 |

18.62 |

2.547 |

0.867 |

| 336 |

231.69 |

5.12 |

4.67 |

18.66 |

1.67 |

17.04 |

2.796 |

0.969 |

Table 6.

Contact angle of EPDM vulcanizates after aging.

Table 6.

Contact angle of EPDM vulcanizates after aging.

| Samples |

0h |

24h |

72h |

120h |

168h |

336h |

| 1# |

104.0 |

105.5 |

97.0 |

95.5 |

93.5 |

91.5 |

| 2# |

108.0 |

108.1 |

107.5 |

105.1 |

102.6 |

94.8 |

Table 7.

TG/DTG curve data of EPDM vulcanizates after aging.

Table 7.

TG/DTG curve data of EPDM vulcanizates after aging.

| Aging time/h |

Initial weight loss temperature/℃ |

Maximum weight loss temperature/℃ |

| First stage |

Second Stage |

Third Stage |

First stage |

Second Stage |

Third Stage |

| |

1# |

2# |

1#、2# |

1#、2# |

1# |

2# |

1#、2# |

1#、2# |

| 0 |

93 |

101 |

393 |

800 |

245.67 |

253.33 |

479.33 |

1222.33 |

| 24 |

89 |

100 |

393 |

800 |

244.30 |

257.00 |

479.33 |

1222.33 |

| 72 |

89 |

107 |

393 |

800 |

298.00 |

283.00 |

479.33 |

1222.33 |

| 120 |

89 |

97 |

393 |

800 |

300.00 |

313.67 |

480.33 |

1222.33 |

| 168 |

86 |

89 |

393 |

800 |

318.67 |

306.67 |

480.33 |

1222.33 |

| 336 |

84 |

87 |

393 |

800 |

325.00 |

327.67 |

479.67 |

1222.33 |

Table 8.

Thermal analysis data of TG/DTG curve of EPDM vulcanizates after aging.

Table 8.

Thermal analysis data of TG/DTG curve of EPDM vulcanizates after aging.

| Aging time/h |

activation energy E/kJ.mol-1

|

the number of reaction stages |

R |

| 1# |

2# |

1# |

2# |

1# |

2# |

| 0 |

440.111 |

434.951 |

4.4084 |

4.0562 |

0.96104 |

0.96488 |

| 24 |

434.981 |

431.557 |

4.1105 |

3.9756 |

0.95935 |

0.9649 |

| 72 |

426.952 |

411.185 |

4.0395 |

3.9283 |

0.97098 |

0.94975 |

| 120 |

420.865 |

413.527 |

3.9563 |

3.7456 |

0.9716 |

0.97406 |

| 168 |

424.908 |

412.543 |

3.9393 |

3.8535 |

0.97151 |

0.96355 |

| 336 |

418.352 |

405.043 |

3.9443 |

3.7375 |

0.96546 |

0.95589 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).