1. Introduction

Backyard production systems (BPS) represent the most common form of animal production worldwide [

1]. Approximately 13% of world population is linked to small-scale family production systems, which contribute to household economy and the supply of basic food in rural areas [

2]. In Chile, 92% of agricultural farms correspond to small-scale family settings [

3]. However, the great volume of Chilean agricultural production is concentrated in the industrial sector. Industrial and backyard production coexist in the central zone of Chile, which includes Metropolitan, Libertador General Bernardo O’Higgins (LGB O’Higgins) and Valparaiso regions. This area concentrates more than 80% of the total pigs in the country and 2,282 swine BPS are located in this same area [

4]. The Chilean pork production is concentrated at the industrial sector through highly integrated large-scale commercial farms that implement high standards of biosecurity. On the contrary, BPS are small-scale family farms where different animal species are bred, being poultry species the most commonly present, followed by swine, and with practically absent implementation of biosecurity measures [

5,

6]. Backyard production contributes to family economy and food access. Regarding poultry, studies performed in central Chile described that 62% of poultry backyard farmers obtain a positive balance from production and poultry products are mainly intended for household consumption and traded in some cases. Besides, household poultry consumption increases as BPS distance to markets also increases and is greater for low-income families compared to families of higher per capita income [

7].

Although biosecurity measures implemented in swine BPS have not yet been deeply characterized, deficiencies in these practices have been well documented in poultry BPS in the literature. The most common deficiencies described are the incorrect handling of mortalities, no veterinary treatment of sick animals, the absence of disinfection procedures at the entrance of people, vehicles, or materials, among others. In addition, backyard animals may contact directly with wild birds and neighboring backyard animals [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Therefore, people, domestic and wild animals come into contact in BPS, which could favor the entry of animal pathogens into the backyard or the emergence of zoonotic diseases, with a potential negative impact on both animal and public health [

5,

9,

10,

11]. In this context, swine constitute a key specie in the epidemiology of zoonotic infections of influenza A virus (IAV) because they are susceptible to both IAV of avian and mammalian origin [

12,

13]. Recent studies have shown that IAV is circulating in poultry and swine kept in BPS from central Chile with reported prevalence at the farm level ranging among seasons from 27% to 45%, detecting both poultry and swine positives by RT-qPCR [

6,

8,

14]. In addition, an IAV (H1N2) was isolated from a pig kept in a BPS located in Valparaiso region that was shown to be a reassortment of human (HA and NA glycoprotein genes) and swine (internal genes) virus genes, representing a potential risk for people in contact with animals kept in these production systems and for public health in general [

15]. Nevertheless, despite the antecedents that highlight the potential role of swine BPS as point of emergence of zoonotic diseases, these production systems have not yet been deeply characterized in Chile. Consequently, the objectives of this paper are: i) to characterize swine BPS in the central zone of Chile in terms of structure, animal management and implemented biosecurity measures, and ii) to describe the value chain of production.

2. Materials y Methods

2.1. Study area and study design

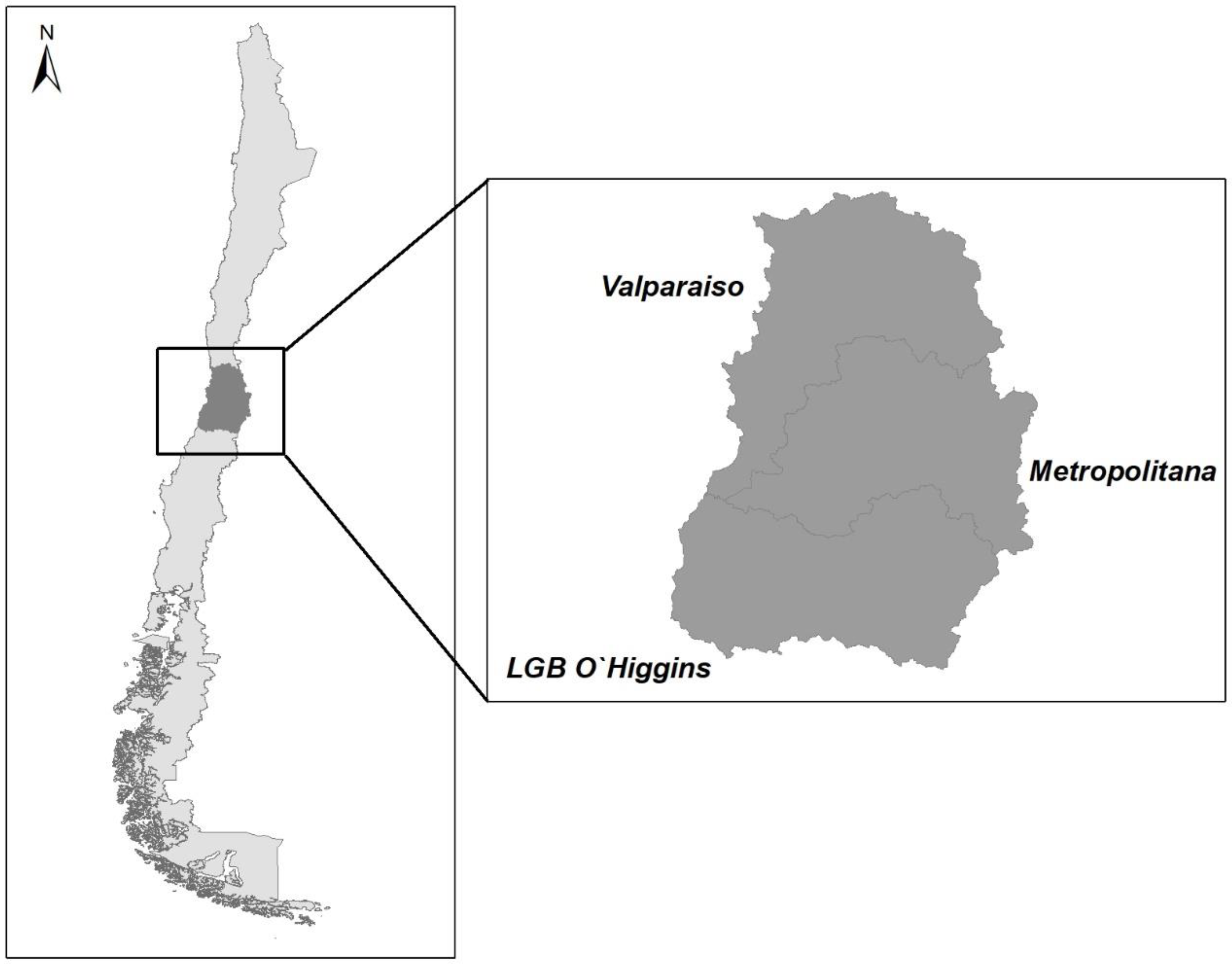

The target population included BPS breeding swine located in the central zone of Chile, including Metropolitan, LGB O’Higgins and Valparaiso regions (

Figure 1). This area of Chile has the highest population of swine and poultry in both industrial and backyard farm settings [

4]. A total of 358 BPS were included in the present study. Of these, 71 BPS were selected through a stratified and proportional sampling that covered all the provinces of the three regions of central Chile, previously described by Bravo-Vasquez and colaborators [

8]. The remaining 287 BPS come from a study that aimed to evaluate the risk of introduction of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) virus, which included all swine BPS in a highly concentrated industrial production area of 100 km

2 located in Metropolitan and LGB O’Higgins regions.

Figure 1.

Study area in the central zone of Chile including Metropolitana, Libertador General Bernardo O’Higgins (LGB O’Higgins) and Valparaiso regions.

Figure 1.

Study area in the central zone of Chile including Metropolitana, Libertador General Bernardo O’Higgins (LGB O’Higgins) and Valparaiso regions.

2.2. Farm data colection

Farm data was collected using a face-to-face semi-structured interview administered to swine backyard farmers by Veterinarians from the Faculty of Veterinary and Livestock Science of the University of Chile between 2013 and 2015. The duration of the questionnaire was approximately 20 minutes and consisted of open and close questions about BPS structure, handling of the animals, animal movements in and out of the BPS, implemented biosecurity measures, and type and destination of animal products, among others (

Table 1). Questionnaire variables considered for the characterization of biosecurity measures implemented in BPS were: 1) presence of functional fences, 2) presence of footbaths, 3) farmers handwashing before and after handling animal, 4) presence of poultry or swine in neighboring BPS, 5) proximity to commercial poultry or swine farms, and 6) presence of a water body inside the BPS.

2.3. Data analysis

The variables collected through the interwiew were presented using descriptive statistics. The comparison of BPS size between different categories was evaluated using non-parametric tests (Kruskal Wallis), according to the distribution of the response variable. Comparison of proportions of categorical variables were made using Chi-square test. Statistical tests were performed using InfoStat statistical software and the statistical significance was set at ≤0.05.

Questionnaire performed to a total of 71 BPS included variables related to type, origin and destination of inputs and outputs of swine production and were used to build a conceptual framework in order to describe the value chain of swine backyard production.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of swine BPS: structure, animal handling and biosecurity measures

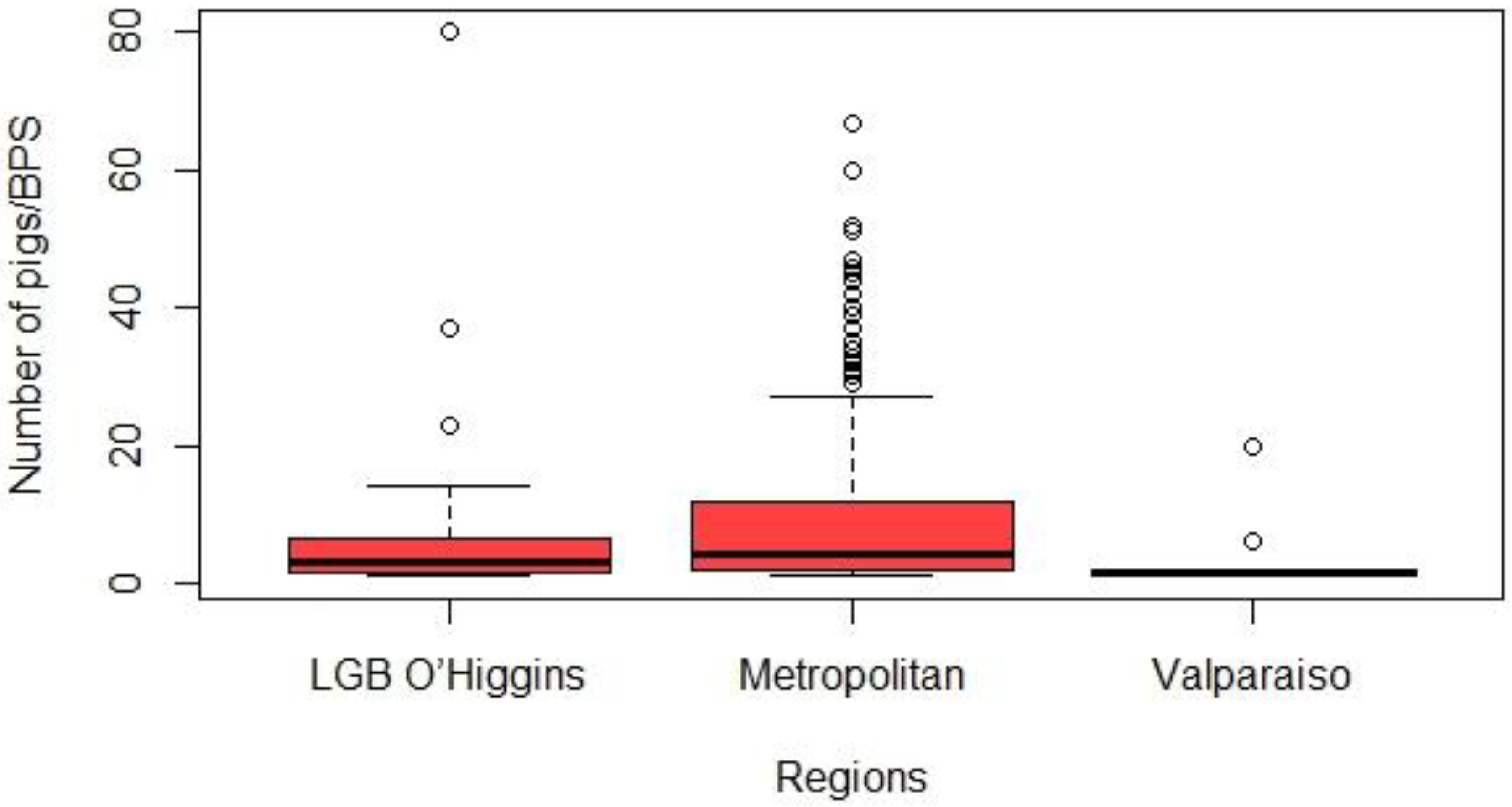

A total of 358 swine backyard farmers from Metropolitan (n = 269), LGB O’Higgins (n = 75) and Valparaiso (n = 14) regions were interviewed. The median BPS size was 4 pigs (minimum = 1; maximum = 80), being greater for Metropolitan (median = 4), compared to LGB O’Higgins and Valparaiso regions, whose medians were 3 and 1.5 pigs per BPS, respectively (

P = 0.001;

Figure 2). Most of the BPS farmers reported household consumption of pig products as the main objective of breeding swine or a mixed objective of household consumption and sale (45% and 46%, respectively), while only 9% of backyard farmers reported that the objective of pig production was exclusively the sale of the products, being these proportions significatively different (

P < 0.001). Years of swine rearing was equal or greater than two years for 61% of BPS, while 39% of BPS owners reported to have started raising pigs in the last two years. Men were in charge of pigs in 57% of the BPS, followed by the family (22%) and women (21%). The differences found in the proportions of different confinement management were significant (

P < 0.001), where the most prevalent type of confinement was permanent (76%), followed by mixed confinement keeping pigs free for at least part of the day (20%) and free-range (4%). The entry and exit of pigs to the farm was commonly reported, 16% of backyard farmers reported lending breeding animals to other farms, being a very common practice to lent breeding animals to various neighboring backyards. Besides this, the most common origin of swine replacements was from outside the BPS (63%), among which the most common strategy was to acquire animals from neighbors (

Table 1).

Regarding animal health management, almost 80% of BPS owners reported not receiving veterinary care. Farmers declared to perform veterinary treatments to pigs in 55% of BPS, however, less than half of these BPS reported to call a veterinarian when pigs showed clinical signs of disease. Incorrect handling of pig mortalities (any method other than burial or burning, i.e., dispose off the farm or throw to garbage) was reported by 28% of BPS (

Table 1).

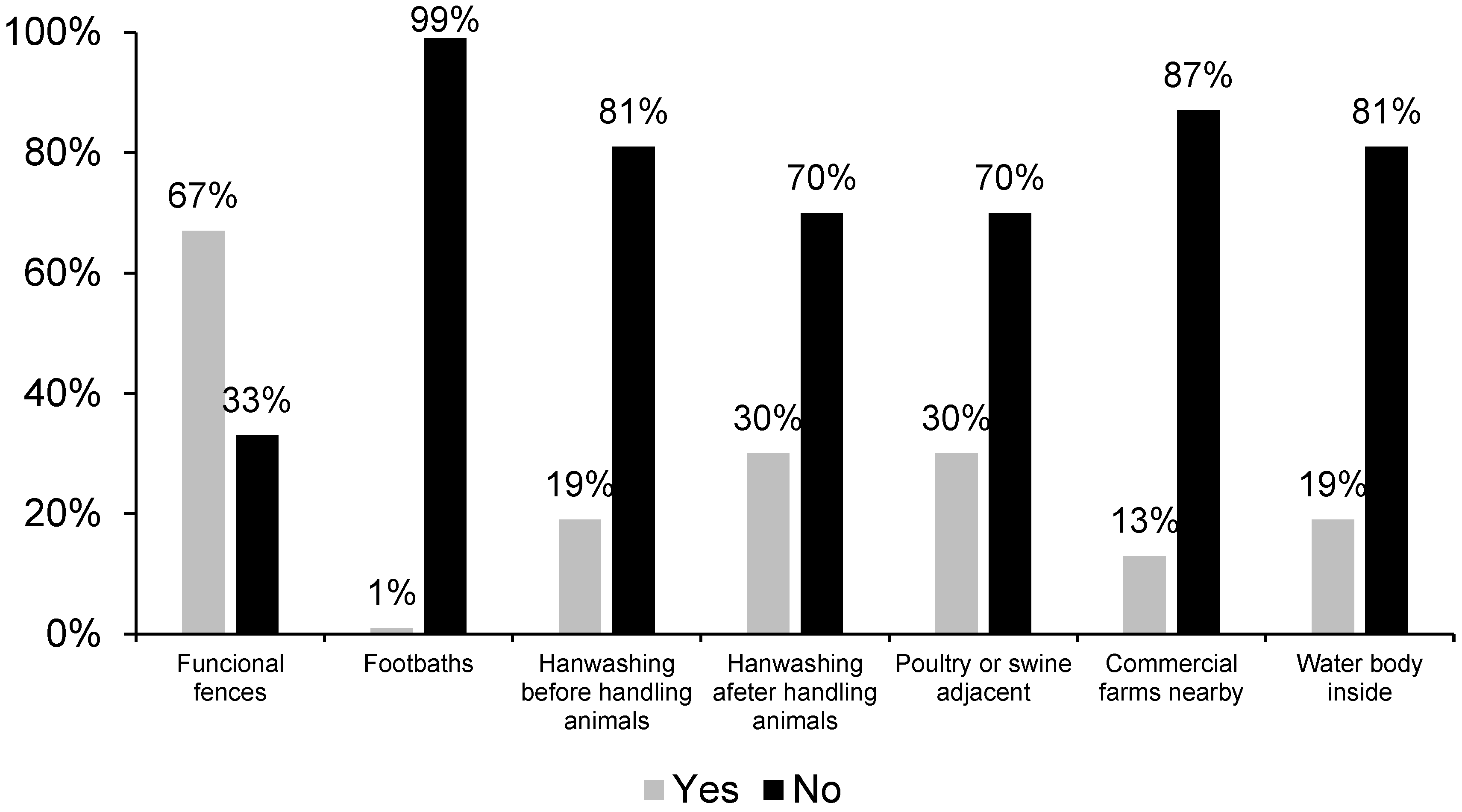

In general, the implementation of biosecurity measures was very limited. In almost no BPS footbaths were present at the entrance to the pens and no hand washing was performed prior to handling the animals. Functional fences were present in 79% of BPS. Hand washing after handling the animals was reported in 70% of BPS (

Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Box plot for swine backyard production system (BPS) size (total number of pigs per BPS) for Libertador General Bernardo O’Higgins (LGB O’Higgins), Metropolitan and Valparaiso regions in the central zone of Chile.

Figure 2.

Box plot for swine backyard production system (BPS) size (total number of pigs per BPS) for Libertador General Bernardo O’Higgins (LGB O’Higgins), Metropolitan and Valparaiso regions in the central zone of Chile.

Table 1.

Questionnaire variables used for the characterization of swine backyard production systems in the central zone of Chile.

Table 1.

Questionnaire variables used for the characterization of swine backyard production systems in the central zone of Chile.

| Variable |

Categories |

Number |

Percentage |

| Main objective of |

Household consumption |

157 |

45% |

| swine breeding |

Sale |

31 |

9% |

| |

Household consumption and sale |

163 |

46% |

| |

Total |

351 |

|

| Years of swine |

Less than 2 years |

133 |

39% |

| rearing |

Between 2 and 10 years |

98 |

28% |

| |

More than 10 years |

113 |

33% |

| |

Total |

344 |

|

| Confinement |

Free range |

15 |

4% |

| |

Mixed |

69 |

20% |

| |

Permanent |

268 |

76% |

| |

Total |

352 |

|

| Swine management |

Woman in charge |

74 |

21% |

| |

Man in charge |

200 |

57% |

| |

Family in charge |

75 |

22% |

| |

Total |

349 |

|

| Veterinary care |

No veterinary care |

272 |

78% |

| |

Veterinary care at least once a year |

76 |

22% |

| |

Total |

348 |

|

| Feeding |

Grains |

58 |

17% |

| |

Swine feed |

15 |

5% |

| |

Scavenging and household scrap |

21 |

6% |

| |

Mixed |

241 |

72% |

| |

Total |

335 |

|

| Water |

Potable sources |

303 |

87% |

| |

Environmental sources |

47 |

13% |

| |

Total |

350 |

|

| Mortalities handling |

Bury |

208 |

63% |

| |

Burn |

28 |

9% |

| |

Throw to the garbage |

14 |

4% |

| |

Throw far away |

17 |

5% |

| |

Household consumption or sale |

4 |

1% |

| |

Nothing |

8 |

3% |

| |

Mixed |

24 |

7% |

| |

No mortalities reported |

25 |

8% |

| |

Total |

328 |

|

| Movement of swine |

Yes |

39 |

16% |

| in or out the BPS |

No |

202 |

84% |

| |

Total |

241 |

|

| Replacement |

Own offspring |

123 |

37% |

| |

Neighbors |

146 |

43% |

| |

Own offspring and neighbors |

32 |

10% |

| |

Markets or other |

21 |

6% |

| |

Mixed |

15 |

4% |

| |

Total |

337 |

|

Figure 3.

Characterization of biosecurity measures implemented in swine backyard production systems in the central zone of Chile.

Figure 3.

Characterization of biosecurity measures implemented in swine backyard production systems in the central zone of Chile.

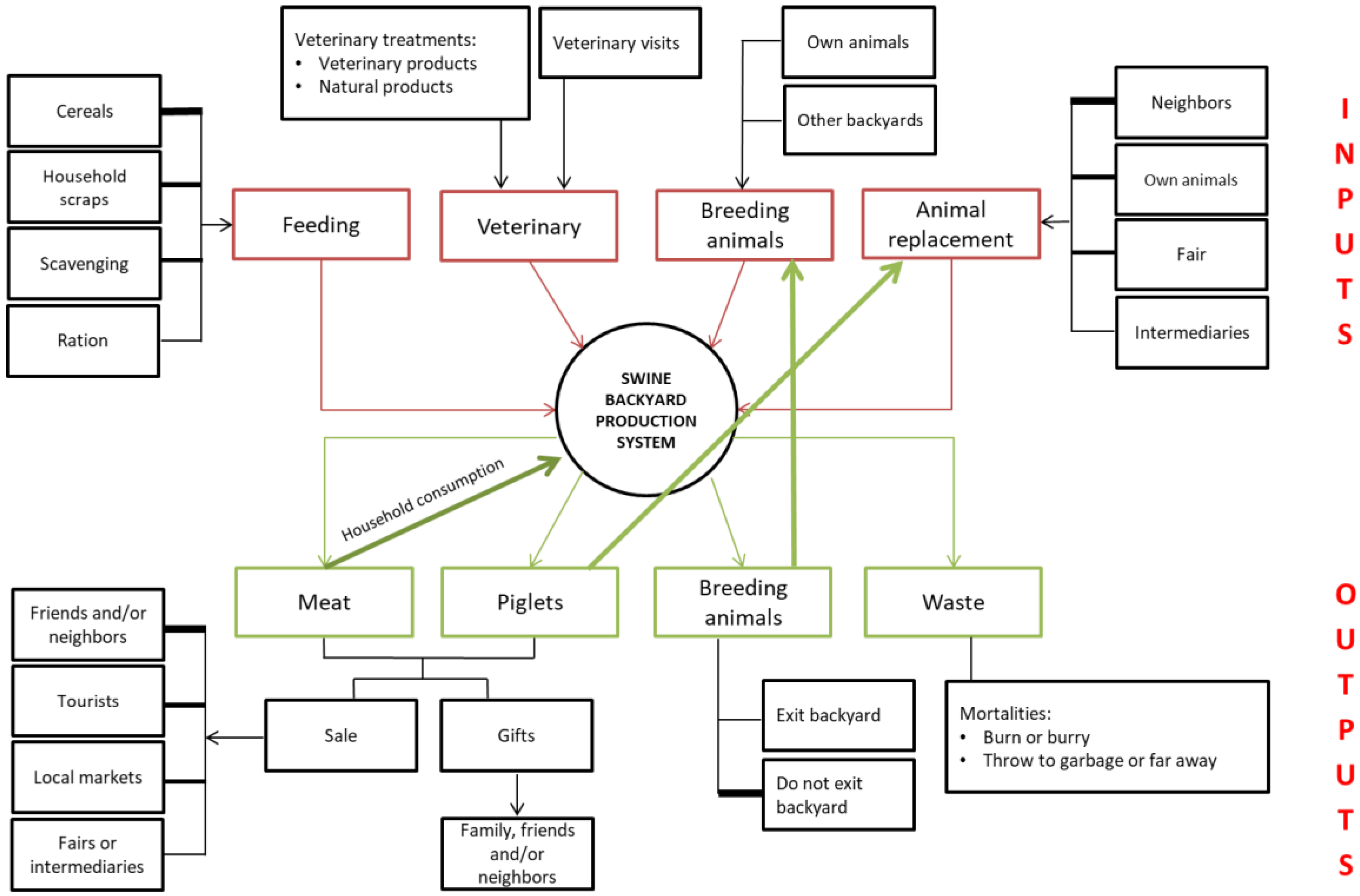

3.2. Description of swine BPS value chain in central Chile

Inputs of swine backyard production included feed, veterinary visits, veterinary products (antibiotics, antiparasitic, vitamins, and others), animal replacements (own replacements, from other BPS, fairs, commercial farms, or intermediaries) and breeding animals (own or from other BPS). Regarding outputs, the main products obtained from swine production were live animals (piglets and breeding animals) and meat. Meat was the most valuable product for 55% of swine backyard farmers. Besides, wastes (dead animals and others) were considered as a production output. The main buyers of meat and piglets were relatives, neighbors, tourists, local markets, fairs, and intermediaries. Piglets were also used as animal replacements in the same BPS and as gifts to family, neighbors, and friends. Breeding animals were destined for the same BPS or lent to other BPS for reproductive purposes. In the majority of BPS, dead animals were handled correctly (i.e., burning or burial). However, in some BPS, it was reported that dead animals were sold or consumed by household members or thrown away from the BPS (

Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Conceptual framework of type, origin and destination of inputs and outputs of swine backyard production systems of the central zone of Chile.

Figure 4.

Conceptual framework of type, origin and destination of inputs and outputs of swine backyard production systems of the central zone of Chile.

4. Discussion

In the present study, swine BPS in the central zone of Chile were characterized based on general structure, handling of animals and biosecurity measures implemented, together with the description of the value chain of swine backyard production. Results indicate that the implementation of biosecurity measures such as the presence of footbaths and hand washing before and after handling the animals are absent in many BPS, along with possible contact of pigs with domestic animals from neighboring backyards and the lack of animal health management. Lack of biosecurity measures have already been reported in backyard poultry rearing in Chile [

5,

6,

7,

8,

14], however, swine BPS has not yet been deeply characterized. The results reported in the present study are similar to those reported by other studies carried out in countries where backyard pig production is widely extended due to its significant contribution to rural poverty alleviation and where backyard and small-scale swine farmers have experienced very important economic losses due to the introduction of African swine fever [

16,

17,

18]. Costard

et al (2009) described heterogeneity regarding biosecurity practices for small swine farming systems located in different study areas, suggesting that the heterogeneity may be due to differences in culture, climate, and training of farmers [

16]. Geographic differences could also be present in different regions of Chile, which throughout its territory includes a wide range of climatic conditions, as well as differences in husbandry practices, therefore further studies are needed to assess these differences.

Regarding animal confinement, different management is present depending on the specie bred. Studies carried out in poultry BPS in Chile have reported that only about 10% of the BPS have permanent confinement of poultry [

5,

7]. On the contrary, the present study found that permanent confinement is the most used management in swine BPS. However, due to the type of pens found in swine backyard production (most of them are not roofed), contact with domestic and wild animal is still important.

The value chain of production presented in this study shows that there is usually movement of animals in and out the backyard farm, as the most common origin of animal replacements was from outside the farm and breeding animals were lend to other farms in 16% of BPS. Sanitary status of backyard pigs is usually unknown due to the lack of veterinary care and animal health management, representing a risk for the dissemination of animal diseases. Most of backyard farmers reported that the main objective of swine backyard production is household consumption of products. Meat is the most important output of swine production and slaughter is carried out in the backyard without the inspection of meat products by veterinary doctors, which represents a risk of people exposure to food borne pathogens, such as Salmonella

spp. [

19].

The risk of introduction and dissemination of animal pathogens in swine BPS evidences the challenges of disease control in backyards [

9]. In the present study the third part of backyard farmers reported not having functional fences, indicating that backyard swine may have contact with domestic or wild animals from outside the BPS in a context of lack of biosecurity. This is of particular importance considering the recent confirmation in July 2021 of outbreaks of African Swine Fever in BPS located in two geographic regions of Dominican Republic, constituting the first report of African Swine Fever in the Americas since 1980 [

20,

21]. Due to the high risk of animal diseases dissemination in swine BPS, backyards constitute a particular challenge in disease eradication programs, such as the epidemiological strategy that allowed a large part of Colombian territory to be declared free of Classical Swine Fever, where an important backyard management component was fundamental [

22]. In addition, swine production farms have a potential role in the emergence and spread of zoonotic diseases of very adverse impact on public health. This was the case of the H1N1 (pdmH1N1) influenza pandemic that emerged in Mexico in 2009, where a new viral variant was initially transmitted from pigs to people and later between people through the respiratory route, giving rise to the first pandemic of the 21st century [

13,

23,

24]. In this regard, previous findings of IAV circulation in pigs kept in BPS in central Chile further highlight the importance of our results [

6,

14,

15]. The identification of a human-swine reassort IAV H1N2 in a pig kept in a backyard in the central zone of Chile with the ability to replicate in-vivo and in-vitro and to be transmitted by droplets in ferret model evidences the risk of exposure to animal-origin IAV of backyard farmers and household members [

15]. The scarce implementation of biosecurity measures in the management of backyard swine and the important movement of animals between backyards described in the present study, together with previous evidence of IAV circulation on backyard pigs, indicate that swine backyards may play an important role in the emergence of zoonotic diseases with potential negative impact on public health.

5. Conclusions

The movement of animals and animal products in and out the backyard, together with the deficient implementation of biosecurity measures in swine BPS from Central Chile indicate a high risk of introduction and dissemination of animal diseases, as well as risk of emergence of zoonotic diseases. Therefore, swine BPS in the central zone of Chile should be part of a target population where surveillance programs and preventive measures are directed in order to avoid the emergence of zoonotic pathogens that may have a potential very negative impact for public health.

Author Contributions

C.H.-W. contributed conception and design of the study; C.B., P.G., C.O., P.J.-B., F.D.P., V.M, performed field activities., C.B. organized the database; C.B., F.D.P., V.M., C.H.-W. analyzed the data; C.B. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Fondecyt grant 1191747 to CHW and ANID scholarship 21190466 (2019) to CB. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sonaiya: E.B., Swan, S.E.J.: Small Scale Poultry production technical guide. FAO Animal Production and Health. (2004).

- FAO: Smallholder poultry production – livelihoods, food security and sociocultural significance, by K. N. Kryger, K. A. Thomsen, M. A. Whyte and M. Dissing. FAO Smallholder Poultry Production. (2010).

- FAO: Agricultura familiar en América Latina y el Caribe: Recomendaciones de Política. (2014).

- INE: Censo Agropecuario. Santiago, Chile. (2007).

- Hamilton-West, C., Rojas, H., Pinto, J., Orozco, J., Hervé-Claude, L.P., Urcelay, S.: Characterization of backyard poultry production systems and disease risk in the central zone of Chile. Res Vet Sci. 93, 121–124 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.06.015. [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Vasquez, N., di Pillo, F., Lazo, A., Jiménez-Bluhm, P., Schultz-Cherry, S., Hamilton-West, C.: Presence of influenza viruses in backyard poultry and swine in El Yali wetland, Chile. Prev Vet Med. 134, 211–215 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2016.10.004. [CrossRef]

- di Pillo, F., Anríquez, G., Alarcón, P., Jimenez-Bluhm, P., Galdames, P., Nieto, V., Schultz-cherry, S., Hamilton-west, C.: Backyard poultry production in Chile : animal health management and contribution to food access in an upper middle-income country. Prev Vet Med. 164, 41–48 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2019.01.008. [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Vasquez, N., Baumberger, C., Jimenez-Bluhm, P., di Pillo, F., Lazo, A., Sanhueza, J., Schultz-Cherry, S., Hamilton-West, C.: Risk factors and spatial relative risk assessment for influenza a virus in poultry and swine in backyard production systems of central Chile. Vet Med Sci. 6, 518–516 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/vms3.254. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.: Controlling avian influenza infections: The challenge of the backyard poultry. Journal and genetic medicine. 3, 119–120 (2009). https://doi.org/http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2702076/.

- Vandegrift, K.J., Sokolow, S.H., Daszak, P., Kilpatrick, A.M.: Ecology of avian influenza viruses in a changing world. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1195, 113–128 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05451.x. [CrossRef]

- Conan, A., Goutard, F., Sorn, S., Vong, S.: Biosecurity measures for backyard poultry in developping contries: a systematic review. BMC Vet. Res. 8, 240 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-8-240. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y., Ito, T., Suzuki, T., Holland, R.E., Chambers, T.M., Kiso, M., Ishida, H., Kawaoka, Y.: Sialic acid species as a determinant of the host range of influenza A viruses. J Virol. 74, 11825–31 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.74.24.11825-11831.2000. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A., Abdelwhab, E.M., Mettenleiter, T.C., Pleschka, S.: Zoonotic Potential of Influenza A Viruses : A Comprehensive Overview. 1–38 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/v10090497. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Bluhm, P., di Pillo, F., Bahl, J., Osorio, J., Schultz-Cherry, S., Hamilton-West, C.: Circulation of influenza in backyard productive systems in central Chile and evidence of spillover from wild birds. Prev Vet Med. 153, 1–6 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2018.02.018. [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Vasquez, N., Karlsson, E.A., Jimenez-Bluhm, P., Meliopoulos, V., Kaplan, B., Marvin, S., Cortez, V., Freiden, P., Beck, M.A., Hamilton-west, C., Schultz-cherry, S.: Swine Influenza Virus (H1N2) Characterization and Transmission in Ferrets, Chile. 23, 241–251 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2302.161374. [CrossRef]

- Costard, S., Porphyre, V., Messad, S., Rakotondrahanta, S., Vidon, H., Roger, F., Pfeiffer, D.U.: Multivariate analysis of management and biosecurity practices in smallholder pig farms in Madagascar. Prev Vet Med. 92, 199–209 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2009.08.010. [CrossRef]

- Costard, S., Zagmutt, F.J., Porphyre, T., Pfeiffer, D.U.: Small-scale pig farmers’ behavior, silent release of African swine fever virus and consequences for disease spread. Sci Rep. 5, 1–9 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17074. [CrossRef]

- Chenais, E., Boqvist, S., Sternberg-Lewerin, S., Emanuelson, U., Ouma, E., Dione, M., Aliro, T., Crafoord, F., Masembe, C., Ståhl, K.: Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Related to African Swine Fever Within Smallholder Pig Production in Northern Uganda. Transbound Emerg Dis. 64, 101–115 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.12347. [CrossRef]

- Alegria-Moran, R., D., R., Toledo, V. Moreno-Switt, A.I., Hamilton-West, C.: First detection and characterization of Salmonella spp. in poultry and swine raised in backyard production systems in central Chile. Epidemiol Infect. 9, 1–11 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268817002175. [CrossRef]

- Paulino-Ramirez, R.: Food Security and Research Agenda in African Swine Fever Virus: a new Arbovirus Threat in the Dominican Republic. InterAmerican Journal of Medicine and Health. 4, (2021). https://doi.org/10.31005/iajmh.v4i.210. [CrossRef]

- WOAH: Dominican (Rep.) - African swine fever virus (Inf. with) - Immediate notification. Report ID IN_150921. (2021).

- WOAH: Recognition of the Classical Swine Fever Status of Members. Resolution No. 18. 89th General Session. (2022).

- Neumann, G., Noda, T., Kawaoka, Y.: Swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus. Nature. 459, 931–939 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08157. [CrossRef]

- Trovão, N.S., Nelson, M.I.: When pigs fly: Pandemic influenza enters the 21st century. PLoS Pathog. 16, 1–8 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1008259. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).