Introduction

The Middle East offers both organizations with religious and secular motivations a fertile ground for violent extremists to pursue their goals through the use of physical force. ISIS has played a key role in this matter. Therefore, Syria has been steadily moving closer to a likely military triumph, and efforts to negotiate a settlement are still being made. Yemen, while less in the public eye, is nonetheless embroiled in conflict, with both sides labeling the other side as violent extremists. Additionally, complicated and dangerous are the actions of Egypt and other foreign parties in Libya (Pickering, 2019) [1].

The 22 Arab League member states share significant linguistic, cultural, religious, and geographic similarities, in addition to some demographic traits relating to population growth, age distribution, and marriage patterns. The population of Arab nations has nearly tripled over the previous 40 years, rising from approximately 128 million in 1970 to an estimated 359 million in 2010. The population's age distribution is still "young" in comparison to other regions of the world. Compared to an estimated 48 percent for developing countries and 29 percent for developed countries, more than half (54%) are still under the age of 25. Despite the fact that the "youth bulge" as a percentage of the population seems to have peaked at about 2005 (UNPY, cited in Makhlouf, 2015), the continuous population expansion has led to a number of young people unheard of before (Makhlouf, 2015)[2].

Young people are the change agents who have the capacity to create a more prosperous and resilient future for themselves and their communities. Adolescents and young people (10 to 24 years old) currently make up 27% of the total population in the Arab world. Since there are currently few options for meaningful learning, social engagement, and employment, particularly for adolescents and young people, including young women, refugees, and people with special needs, realizing this potential will require urgent and major investments. Even at the most fundamental level of adolescent well-being, there are still many problems. In this area, violence against children begins at a young age and persists all throughout the child's life. Approximately 12 million kids, or over half of all pupils aged 13 to 15, experience bullying at school, with levels above 50 percent in Egypt, Palestine, and Algeria. Conflicts and political instability have further increased the vulnerabilities of adolescents and youth, exposing them to more violence, exploitation, and abuse (World Bank, 2017; No Lost Generation Initiative, 2017; Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, 2020).[ 3][4][5]

Youth must be protected because they are particularly vulnerable to different risks and dangers, including alcohol misuse, violence, sexual exploitation, and destructive beliefs. They pose a threat to society since they are troublemakers, deviants, and people with their own problems. Young people are the present, not just the future; they should be recognized; they are a part of the solution, and young people have agency - the means or power to take action. They are also co-creators because they have the capacity to create, contribute, and make a difference. European Union through SALTO centers [Cultural Diversity (SALTO CD) is one of eight resource centers in the SALTO-Youth network (Support Advanced Learning and Training Opportunities for Youth)] with support of Erasmus+[( is the European Union program for education, training, youth, and sport)] has conducted youth program aims to modernize education, training and youth work across Europe, by developing knowledge and skills, and to increase the quality and relevance of qualifications. (SALTO Cultural Diversity Resource Centre, 2017)[ 6].

The spread and ascent of extremist groups at the start of the twenty-first century are significant global trends. As a result, attention has been drawn to the issue of public insecurity, human rights violations, and societal instability as result of researching these tensions (Dicko, A., Mousa, I., Oumaro, I., & Issaka, M., 2018)[7]. As stated by UNESCO, "Violent extremism has become a serious threat facing societies across the world. It affects the security, well-being, and dignity of many individuals living in both developed and developing countries, as well as their peaceful and sustainable ways of life. It also poses grave challenges to human rights. To date, the challenges presented by violent extremism have been evaluated primarily through military and security lenses (UNESCO, 2017, p.10)"[8]. Violent extremism is currently at the center of social, educational, and security concerns among researchers, policymakers, and the local, national, and global communities.

In reality, extremism takes the form of broad categorizations, sharp distinctions between groups, and a belief in "us" versus "them." An extremist mind turns to rigid categorization and straightforward facts rather than acknowledging the complexity of the social world. The practice of using, threatening, and inciting violence for ideological purposes is known as violent extremism. The worldview and ideals of extremists are used to justify the use of violence. Violent extremism typically opposes equality, diversity, human rights, democracy, and the rule of law. It is common for people to consider their own worldview to be superior to other beliefs. Violent extremism arises from a number of variables; therefore, it cannot be attributed to a particular ideology, religion, or set of beliefs (Dicko, A., Mousa, I., Oumaro, I., & Issaka, M., 2018)[9].

The extremism problem requires the researchers and experts' community to adopt solid theoretical and conceptual grounds and rigorous methodology, especially when working on violent extremism. Therefore, researchers should develop valid and reliable measures in order to produce them. Documenting relevant and available knowledge within public policies has become a national and international priority. Researchers, therefore, focused on how societies produce extremism, analyzing the different stakeholders' motivations and the process that led to this choice. However, violent extremism is a complex construct and does not have a consensual definition. The right of a child to equitable treatment and a secure, nurturing environment that supports the child's personal growth as a contributing member of society is compromised by violent extremism (Zogg, Kurki, Tuomala, & Haavisto, 2021)[10].

In order to stop young people from becoming violent radicals, guardians and other adults who work with children and adolescents have a special responsibility and opportunity. Kids and young people may establish a secure and encouraging atmosphere that enhances their resilience- their capacity to bounce back from change and adversity psychologically. Additionally, parents and professionals who work with young people are well-positioned to spot early changes in a child's thinking or behavior, giving them a chance to intervene at an early stage (Zogg et al., 2021) [11]..

A large portion of the work in the social, behavioral, and health sciences depends on the development and validation of scales. However, the combination of methods needed for scale creation and evaluation can be time-consuming, resource-intensive, and jargon-filled. Scales are an expression of latent constructs; they measure the actions, attitudes, and speculative events that we anticipate will occur as a result of our theoretical grasp of the universe but are unable to be directly evaluated (DeVellis, 2012)[12]. Scale development is both a time-consuming and challenging process (Schmitt & Klimoski, 1991) [13]. Scales are frequently employed to measure behaviors, emotions, or actions that cannot be adequately expressed by a single variable or item (Boateng, Neilands, Frongillo, Melgar-Quiñonez & Young, 2018 ) [14].

Scale construction is the process of creating an accurate and valid measure of a construct in order to evaluate an important attribute that poses special difficulties because it is typically impossible to observe. Unobservable constructs must be evaluated indirectly, such as by self-report, as they cannot be measured directly. Furthermore, these constructs are frequently quite abstract. Finally, rather than being a single, standalone concept, these constructions are frequently complicated and may include a number of different components. Because of this complexity, creating a measurement instrument can be difficult, and validation is crucial for the creation of scales (Tay & Jebb, 2017) [15].

Literature review

Definitions of the construct of violent extremism

Construct Definition: A clear conceptualization of the violent extremism construct is required. This entails delineating and defining the construct based on the literature review and existing relevant scales. A construct that is very broad (e.g., extremism in general) and is composed of many dimensions or components. A theoretical step is needed to specify the likely number of components, or dimensions, that make up the construct of violent extremism. It is a multidimensional construct. The dimensionality of a youth violent extremism construct can be understood as a combination of a number of distinct sub-components (multidimensional). The following table summarizes some of the frequently cited construct definitions.

Table 1.

Governmental and intergovernmental definitions of the construct of violent extremism.

Table 1.

Governmental and intergovernmental definitions of the construct of violent extremism.

| Governmental Definitions |

|---|

Australia

|

Violent extremism. Violent extremism is the beliefs and actions of people who support or use violence to achieve ideological, religious or political goals. This includes terrorism and other forms of politically motivated and communal violence. All forms of violent extremism seek change through fear and intimidation rather than through peaceful means. If a person or group decides that fear, terror and violence are justified to achieve ideological, political or social change, and then acts accordingly, this is violent extremism (Australian Government measures to counter violent extremism: a quick guide, 2017, p.1) [16]. |

| Canada |

"[V]iolent extremism" is where an offense is "primarily motivated by extreme political, religious or ideological views". Some definitions explicitly note that radical views are by no means a problem in themselves, but that they become a threat to national security when such views are put into violent action (Public Safety Canada, 2009, pp 1-2)[17]. |

| USA, The FBI & USAID |

"encouraging, condoning, justifying, or supporting the commission of a violent act to achieve political, ideological, religious, social, or economic goals", whilst USAID defines violent extremist activities as the "advocating, engaging in, preparing, or otherwise supporting ideologically motivated or justified violence to further social, economic or political objectives" (USAID, 2011, p. 2)[18]. |

| Norway |

Violent extremism constitutes activities of persons and groups that are willing to use violence in order to achieve political, ideological or religious goals (* Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security, 2014, p. 9)[19]. |

| Sweden |

A violent extremist is someone "deemed repeatedly to have displayed behavior that does not just accept the use of violence but also supports or exercises ideologically motivated violence to promote something" (Government Offices of Sweden, 2011, p. 9)[20]. |

| UK |

Extremism is defined as the vocal or active opposition to fundamental values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and the mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs, as well as calls for the death of United Kingdom armed forces at home or abroad (HM Government (UK), 2015, p. 9)[21]. |

Finland

Save the Children Finland |

Extremism describes thinking that is, by its nature, markedly stark, absolute, and black and white. Typically, it involves stiff and uncompromising views on right and wrong – which in reality manifest as generalizing classifications and strong separation of groups, with an idea of “us” and “them”. An extremist mind does not accept the complexities of the social world, but rather resorts to rigid and strict categorization and simple truths.

Violent extremism describes the process of rationalizing the use, threat, an incitement of violence by ideological means4. Extreme measures – the use of violence– are seen as justified by means of extremists’ worldview and values. Typically, violent extremism opposes diversity, human rights, democracy and rule of law. It is also usual that one’s own worldview is seen as superior and other ideologies as wrong or false. Violent extremism cannot be reduced to one single ideology, religion, or set of values, as it is a result of a variety of factors (Zogg, Kurki, Tuomala, & Haavisto, 2021 p. 7)[22]. |

| International Organization for Migration |

Violent extremism can be defined as “the beliefs and actions of people who support or use violence to achieve ideological, religious or political goals”, including “terrorism and other forms of politically motivated and communal violence”. According to this definition, “all forms of violent extremism seek change through fear and intimidation rather than through peaceful means”. Thus, “if a person or group decides that fear, terror and violence are justified to achieve ideological, political or social change, and then acts accordingly, this is violent extremism”. However, it is important to note that violence here is a key concept (Dicko, A., Mousa, I., Oumaro, I., & Issaka, M., 2018 p.1)[23]. |

| Intergovernmental definition |

| The USAID |

’advocating, engaging in, preparing, or otherwise supporting ideologically motivated or justified violence to further social, economic or political objectives’ (Glazzard & Zeuthen, 2016, p.1)[24]. |

| Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) |

"[P]romoting views which foment and incite violence in furtherance of particular beliefs, and foster hatred which might lead to inter-community violence"(OECD, 2016)[25]. |

| United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) + Preventing violent extremism through education |

"Refers to the beliefs and actions of people who support or use violence to achieve ideological, religious or political goals" (UNESCO, 2017)[26]. |

| European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report, 2016 |

It consists of the use of violence to instill fear, destabilize and then destroy a disputed existing order (Alava, Frau-Meigs & Hassan, 2017)[27]. |

A current UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) report examined current State practices on policies and measures governing "violent extremism" (General Assembly Human Rights Council report A/HRC/33/29, 2016)[29]. The report also looked at good practices and lessons learned on how protecting and promoting human rights contribute to preventing and countering violent extremism. The phenomenon of "violent extremism" is thought to be more widespread than that of terrorism, notwithstanding the range of definitional approaches. There are many different governmental and intergovernmental definitional approaches to the construct of violent extremism, some examples of which are given here. Extremism is the imposition of one's beliefs, values, and ideologies on others by force to curtail civil and human rights (Schmidt, 2014) [30]. Extremism may include the following two important characteristics (Borum, 2011) [31]. Firstly, the imposition of someone's own beliefs, values, and ideologies on other human beings by force, and secondly, religious, gender, and race-based discrimination and violence to defraud the civil and human rights of minorities and others (Hassan, Khattak, Qureshi, & Iqbal, 2021, p.53) [32].

Identification of the Initials Dimensions

The following are de-identified dimensions; 1. Cult of power; 2. Admissibility of aggression; 3. Forcing consensus; 4. Intolerance; 5. Social pessimism; 6. Mysticism; 7. Destructiveness; 8. Passion for movement; 9. Normativism; 10. Ant introspection; 11. Conformity; 12. Religious centrism; 13. Grievance; 14. Jihadi groups; 15 Dogmatism; 16. Creed; 17. Ideological centrism; 18. Exclusion of others; 19. Group centrism; 20. Fascism; 21. Authoritarianism; 22. Closure and 23. Anti-Women

Item Generation (Question Development)

The following methods were used to identify appropriate questions about the scale. The deductive method: This is based on the description of the relevant domain and the identification of items. This is done through a literature review and assessment of existing scales and indicators of that domain. The inductive method involves the generation of items from the responses of individuals. Qualitative data is obtained through direct observations and exploratory research methodologies, such as focus groups and individual interviews. Qualitative techniques were used to move the domain from an abstract point to the identification of its manifest forms. It is considered best practice to combine both deductive and inductive methods to define the domain and identify the questions to assess it.

Content validity was estimated by evaluation by experts' judges. Content validity is mainly assessed through evaluation by expert and target population judges. Ten experts were used as judges to evaluate the first pool of questions and their relevancy to the Arab youth violent extremism. Expert judges are highly knowledgeable about the domain of interest and/or scale development; target population judges are potential users of the scale (DeVellis, 2012) [33] Based on sample 1 (N=1401), as a first stage, 55 questions were generated that met the inclusion criterion. Items identified using deductive and inductive approaches were broader and more comprehensive.

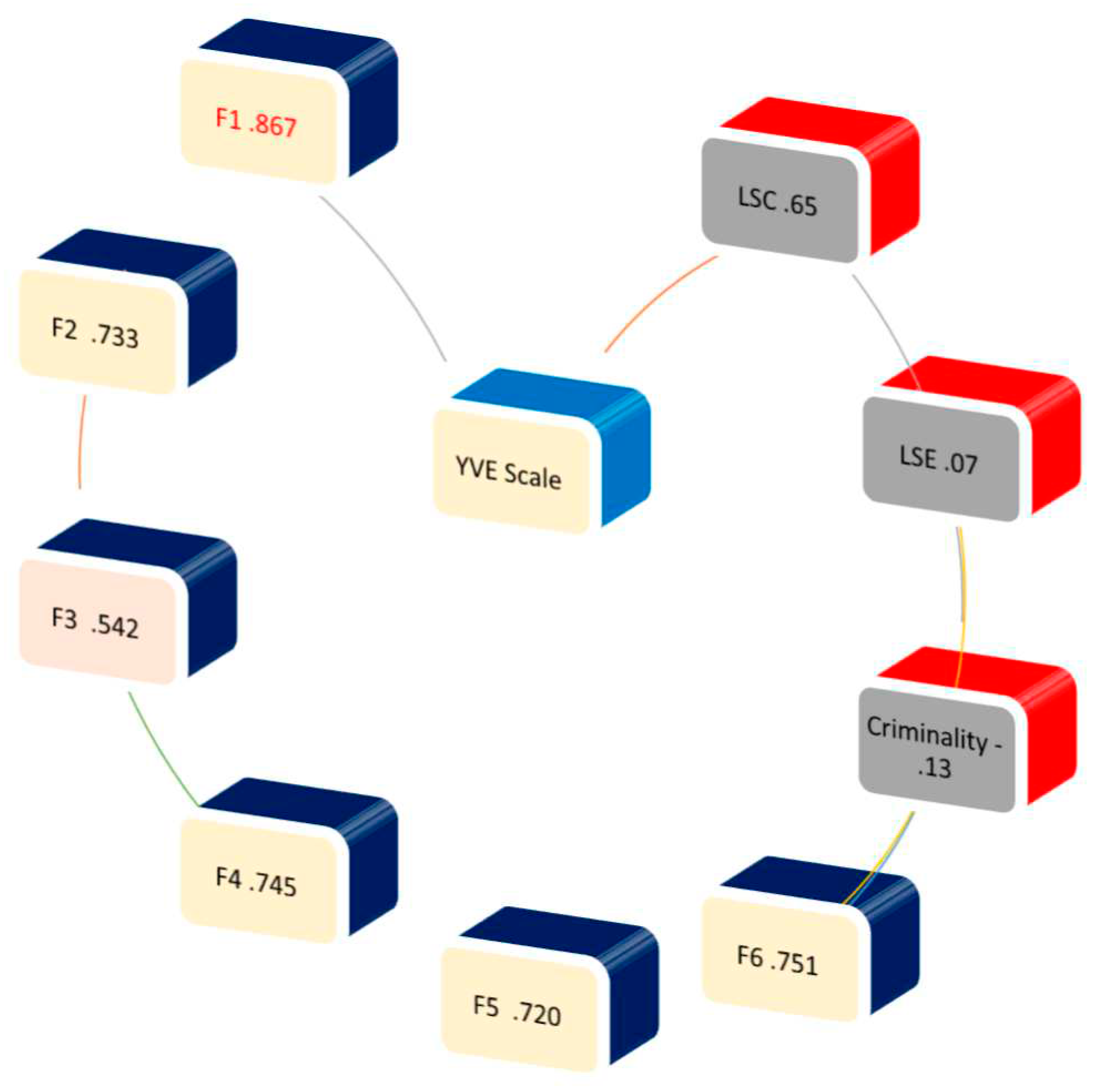

Nomological Network: Utilizing the multidimensional construct definition of violent extremism by outlining the nomological network to present how the violent extremism construct is related to its dimensions (factors) and to other constructs. The principal component factor analysis revealed six factors. The F1 factor labeled "Exclusion of others & intolerance" (9 items), the F2 factor (4 items) "Rigidity & social pessimism," and the F3 factor (5 items) "Dogmatism & forcing consensus," the F4 factor (4 items) "Violence & Jihadi Groups," the F5 factor (3 items) "Cult of power, "and the F6 factor (4 items) "Grievances & mysticism ."Since a scale empirically correlates with other recognized measures in the form predicted by violent extremism theories and the literature review exhibits significant sorts of validity evidence, the nomological network will be crucial to the validation process (convergent and divergent validity) (Tay & Jebb, 2017) [34].

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients between Youth Violent Extremism Scale and Constructs.

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients between Youth Violent Extremism Scale and Constructs.

| |

YVE scale |

F1 |

F2 |

F3 |

F4 |

F5 |

F6 |

| YVE Scale |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| F1 Exclusion of others & intolerance |

.867** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| F2 Rigidity & social pessimism |

.733** |

.563** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

| F3 Dogmatism & forcing consensus |

.542** |

.286** |

.215** |

1 |

|

|

|

| F4 Violence & Jihadi Groups |

.745** |

.557** |

.606** |

.287** |

1 |

|

|

| F5 Cult of power |

.720** |

.529** |

.509** |

.258** |

.542** |

1 |

|

| F6 Grievances & mysticism |

.751** |

.588** |

.419** |

.381** |

.482** |

.483** |

1 |

| Low self-control scale |

.651** |

.566** |

.478** |

.305** |

.536** |

.342** |

.633** |

| Life stress Events |

.070** |

.016 |

.105** |

-.106** |

.093** |

.218** |

.088** |

| Criminality |

-.126** |

-.170** |

.023 |

-.07** |

.016 |

-.116** |

-.136** |

Figure 1.

The nomological network Correlation confidents between Youth Violent Extremism Scale and constructs.

Figure 1.

The nomological network Correlation confidents between Youth Violent Extremism Scale and constructs.

Scale Refinement

Results of the Principle Factor Analysis

Dimensionality

Method: The violent extremism scale that was developed for the present study was derived from available literature on violent extremism and other relevant theories and scales, like the Aspar Extremism scale (KSA). The scale has been developed based on several studies and tests. Study 1 (n = 1401) school students, an initial item pool and evaluated items via expert judges' feedback (n = 10) and a questionnaire developed based on the previous research Aspar Extremism scale (KSA) (ASBAR, 2010, [35], Al-badayneh & ElHasan, 2017[36]). The questionnaire consisted of demographic information, family information, social variables, and feelings of justice, equality, and national pride. Also, it includes religiosity variables, use of force, criminality, violence and life stress events, and low self-control. An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) is used to explore the underlying factor structure, revealing 23 domains and 55 items. Study 2 had a representative sample of (1116) university students with five domains representing 51 items (Al-badayneh, Khalifa & Alhasan, 2016) [37]. Study 3 used EFA and revealed 16 of 44 domains (i.e., women, education, media, jihadism, others, faith, jihadi groups, takfir, use of violence, power, others, fascism, dogmatism, rigidity, and grievances). Study 4 revealed six factors and 29 items. A replication of the factor structure proposed by Study 3 via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) examined the validity of a related construct, violent extremist intentions (n = 4816). Items are selected with the following principles: simplicity, straightforwardness, and with the avoidance of slang, jargon language, duple negativity, ambiguity, or overly abstract or leading questions. The final scale questionnaire was written in Arabic. The Violent Extremism Scale (VES) consists of the youth violent extremism scale of 29 items with six theoretical dimensions.

Instruments of Data Collection

In testing the correlation matrix and sampling adequacy, correlation coefficients were computed and were found to be statistically significant. The determinant (t = 4.85) and the correlation matrix are not singular and statistically significant using Bartlett's test of sphericity (c = 69790.431, α = 0.000), which indicates that the correlation matrix is not an identity matrix.

Table 3.

KMO and Bartlett's Test of Sphericity.

Table 3.

KMO and Bartlett's Test of Sphericity.

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. |

.936 |

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity Approx. Chi-Square |

69790.431 |

| Df |

406 |

| Sig. |

.000 |

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test was used to examine sample adequacy (homogeneity of the sample), and the KMO value in this study was 0.936, a value greater than Zero. Kaiser (1974) [38]. recommended that values greater than (0.5) are acceptable, values between (0.7-0.8) are good, values between (0.8-0.9) are great, and values above (0.90) are superb. As can be seen, Bartlett's Test of Sphericity presented six factors.

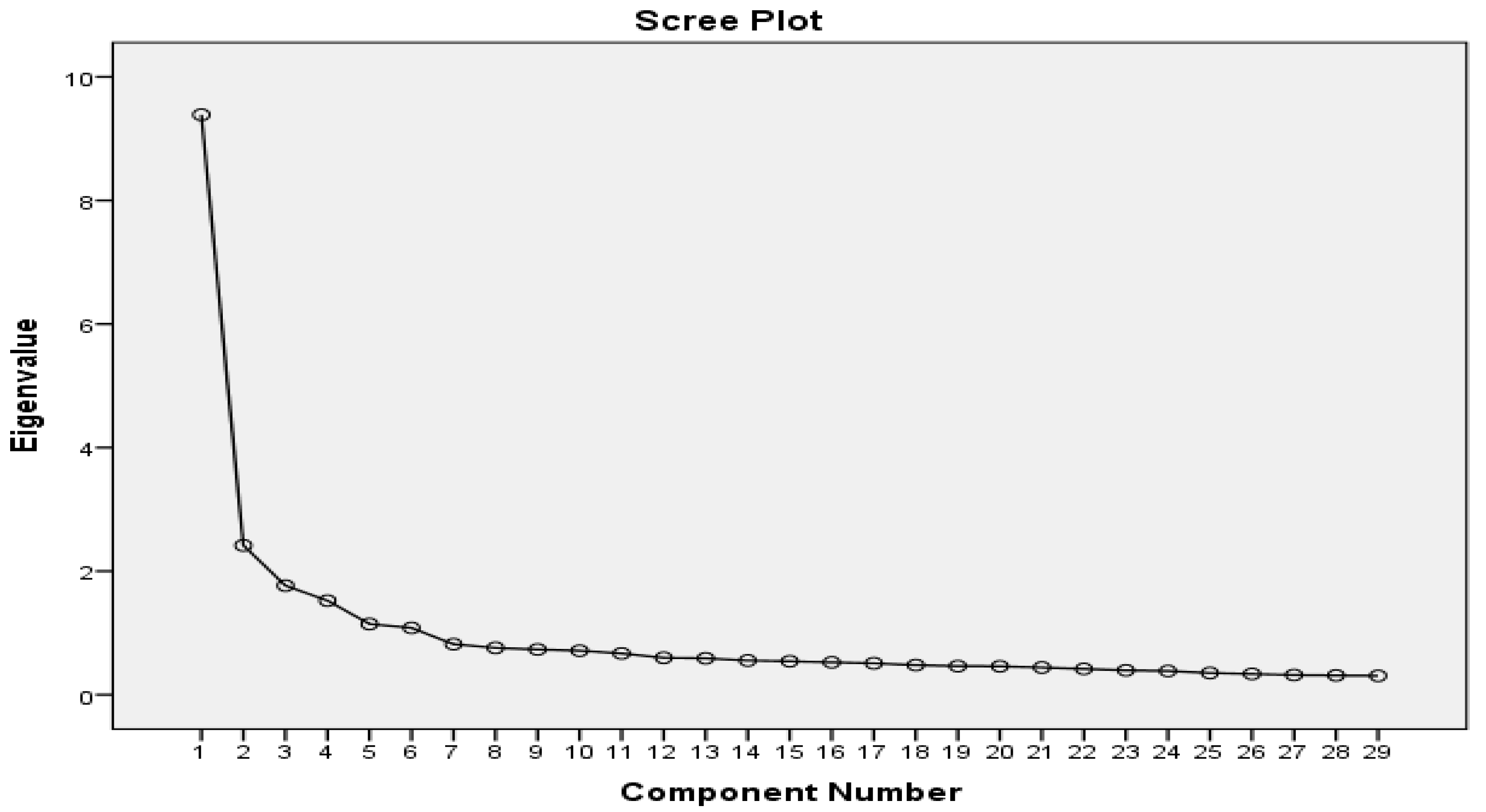

As can be seen from the screen plot, the suggested number of dimensions is 6. Also, factor loading analysis revealed six factors (components).

Item Reduction

The 29-item Violent Extremism Scale is distributed around the following factors:

Exclusion of others & intolerance

Rigidity & social pessimism

Dogmatism & forcing consensus

Violence & Jihadi Groups

Cult of power

Grievances & mysticism

A Principal Component Factor analysis with Varimax with Kaiser Normalization rotation through SPSS (version 22) was used initially to estimate the number of factors empirically and to determine which questions are to be retained. Applying the graphical method called the Scree test first proposed by Cattell (1966) [39], a scree plot was examined, and eigenvalue analysis (i.e., eigenvalue ≥ 1) suggested a 6-factor solution was appropriate for the data (see Figure 2). The factor analysis used Varimax with Maximum likelihood rotation with the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy stopping rule. A factor solution was identified as a resolution of factor analysis, and the Scree Plot Analysis revealed that the six factors accounted for (59.724%) of the variance on the scale. A Principal Component Factor analysis with Varimax with Kaiser Normalization produced six factors (29 items) explaining 59.7% of the total variance of Youth Violent Extremism. The first factor, labeled "Exclusion of others & intolerance" (9 items), explained 15.3% of the variance, the second factor (4 items), "Rigidity & social pessimism," explained 10.2%, and the third factor (5 items) "Dogmatism & forcing consensus" explained 9.3% of the variance. The fourth factor (4 items), "Violence & Jihadi Groups," explained 9.2% of the variance. The fifth factor (3 items), "cult of power," explained 8 % of the variance, and the sixth factor (4 items), "Grievances & mysticism," explained 7.4% of the variance.

Figure 2.

Scree plot 1 representing the number of 6 violent extremism factors.

Figure 2.

Scree plot 1 representing the number of 6 violent extremism factors.

Discussion and Conclusion

Scale development is a challenging and time-consuming process (Schmitt & Klimoski, 1991) [40]. Scale construction is the process of creating an accurate and valid measure of a construct in order to evaluate an important attribute that poses special difficulties because it is typically impossible to observe. Unobservable constructs must be evaluated indirectly, such as by self-report, as they cannot be measured directly. Furthermore, these constructs are frequently quite abstract. Finally, rather than being a single, standalone concept, these constructs are frequently complicated and may include a number of different components. Because of this complexity, creating a measurement instrument can be difficult, and validation is crucial for the creation of scales (Tay & Jebb, 2017) [41]. The complexity and difficulty of proving construct validity for a new measure are described by Cronbach and Meehl (1955) [42]. To avoid the production of ambiguous data, researchers may have as one of their goals the development of standardized measures based on large heterogeneous samples. The use of standardized measures would improve the formulation and testing of theory and make it simpler to compare results (Price & Mueller, 1986) [43]. Future joint research in particular areas may find success in the establishment of measurements. It might also be relevant to challenge criminological research's continuous dependence on survey questionnaires.

The purpose of the study was to develop a cross-cultural youth violent extremism scale (YVES). A scale that considers the within and between cultural differences can be applied and tested in a single or a group of countries and cultures. The future use of the scale can identify the unique practical concerns related to violent extremism. Therefore, the goal also was to concisely develop a new, valid, and reliable research tool for youth violent extremism scale.

Understanding the causes and effects of violent extremism among young people requires a valid and reliable measure of the phenomenon. Furthermore, it's critical to comprehend what can be done to support young people, shield them from violent extremism, and discourage them from engaging in violent behavior in the future. Youth need to be redesigned policies and strategies to be adapted to universal human values in order to make up for the lack of research-center-policies in education and development. De-radicalization has become crucial for preventing extremist relapse and abstaining from violent extremist behaviors. Spreading violent extremism has the potential to harm societal order, human security, and future human progress (Al-badayneh, Khalifa & Alhasan, 2016) [44].

Youth are particularly susceptible to all types of violent extremism. They represent a weak and marginalized group in society who experience exclusion, disenfranchisement, resentment, and alienation from the broader group. The academic setting is perfect for religious radicals' recruitment efforts for their political parties and even for terrorist activities. Schools thus serve as a breeding ground for radicals (Al-Badayneh, 2012) [45]. Youth are the target of recruitment due to their environments that support extremism, such as identity crises among young people and other social crises like poverty, unemployment, inequality, and unjust treatment, as well as their marginalization and exclusion from the majority of significant aspects of life. Exclusion from political involvement, decision-making, and the creation of policies that serve their interests are only a few examples (Al-badayneh, Khalifa & Alhasan, 2016) [46].

In conclusion, this study offers a valid and repeatable scale for measuring youth violent extremism, which is seen as an important increasing global problem. In the majority of nations, this group is particularly susceptible to embracing ideologies and ideas that could inspire terrorism in the future. The scale has proven to be valid and is simple to adapt to various countries and cultures. The application of this scale might enable cross-cultural comparisons. However, additional empirical validation is required, particularly if the scale is to be utilized with a population segment other than university students, as they may have distinctive characteristics not present in younger or older sub-groups.