Appendix 1

The first Einstein field equation and its solutions

The Einstein-Hilbert equation for empty space (i.e., Einstein vacuum) has the form of equation (1) for

where

is the scalar curvature;

is Ricci tensor;

is Christoffel symbols.

Combining Eq.s (1.A1) with the contravariant components of the metric tensor

, we obtain

where

is the number of space dimensions.

For any

n-dimensional space (except for

n = 2), equality (2.A1) can be satisfied only for

R = 0. Therefore, for

n = 4, Eq. (1.A1) takes the simplest form

We will call this equation the first Einstein vacuum equation, and it is an expression of the conservation laws, since

In this case, the solutions of Eq.s (3.A1) describe the metric-dynamic state of stable vacuum formations.

Einstein wrote [

19]: “

The equation of gravity for empty space is the only rationally substantiated case of field theory that can claim to be rigorous.”

Solutions of the Eq.s (3.A1) are considered in many works on modern differential geometry and general relativity. However, none of the publications known to the author discusses the relationship between various solutions of this equations, so we will consider it in sufficient detail.

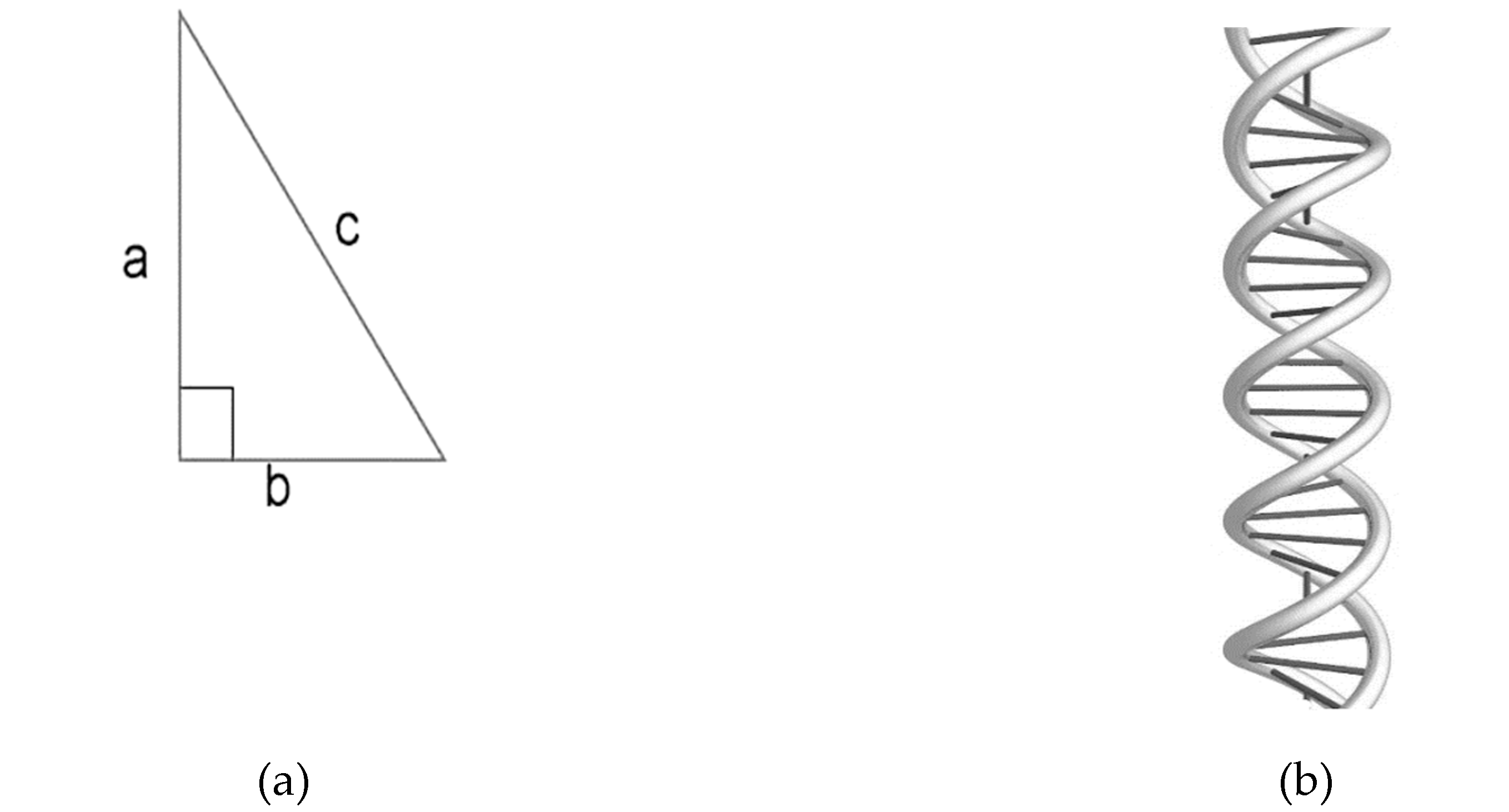

Solutions to Eq.s (3.A1) are sought in a spherical coordinate system in the form of metrics:

where

ν and

λ are the required functions of

t and

r.

As a result of substitution of the covariant and contravariant components of the metric tensor from the metric (4.A1) into Eq. (3.A1) for the stationary (i.e., time-independent) state of the "vacuum", a system of three equations is obtained [

20]:

The differential Eq. (7.A1) has three solutions:

where h1, h2, h3 are integration constants.

Eq. (8.A1) also has three solutions:

where

rb is the integration constant (the radius of the spherical volume).

For h1 = 1, h2 = rb and h3 = 0, the solutions of Eq.s (7.A1) and (8.A1) coincide.

Substituting three possible solutions (10.A1) into the metric (4.A1) we get three metrics with the same signature (+ – – –):

Performing similar operations with the components of the metric tensor from the metric (5.A1), we obtain three more metrics that also satisfy Eq.s (3.A1), but with the opposite signature (– + + +):

Irreducible into each other metrics (11.A1) – (16.A1) will be called generalized Schwarzschild metrics.

Metrics (11.A1) – (16.A1) describe the metric-dynamic state of the same vacuum region, therefore it is proposed to consider various options for averaging them, despite the fact that Eq.s (3.A1) is non-linear and, as a rule, in such cases, the sum of his decisions is not his own decision.

If the centers of the metrics (11.A1) – (13.A1) and (14.A1) – (16.A1) are aligned, then it is obvious that their sum is equal to zero

is also a trivial solution of the vacuum Eq.s (3.A1).

Thus, contrary to expectations, the addition of six metrics (11.A1) – (16.A1) led to an additional solution to Eq. (3.A1).

Consider now the arithmetic mean of two metrics (11.A1) and (12.A1)

The distance between two points

r1 and

r2 along the length with the signature (+ – – –) in general relativity is determined by the expression

in the case of substitution

from the averaged metric (20.A1), we obtain

Let’s first find the value of the segment between the points

r1= rb and

r2 = ∞:

The length of this segment is equal to the radius of the cavity

rb, and the imaginary nature of this result indicates that there is no "vacuum" in the cavity. Outside this cavity from

r1= rb to

r2 = ∞ we have

In the absence of vacuum deformation, the distance between the points

r2 = ∞ and

r1 =

rb is equal ∞ –

rb, and in the case under consideration it is equal to (24.A1). The difference between these segments is approximately equal to

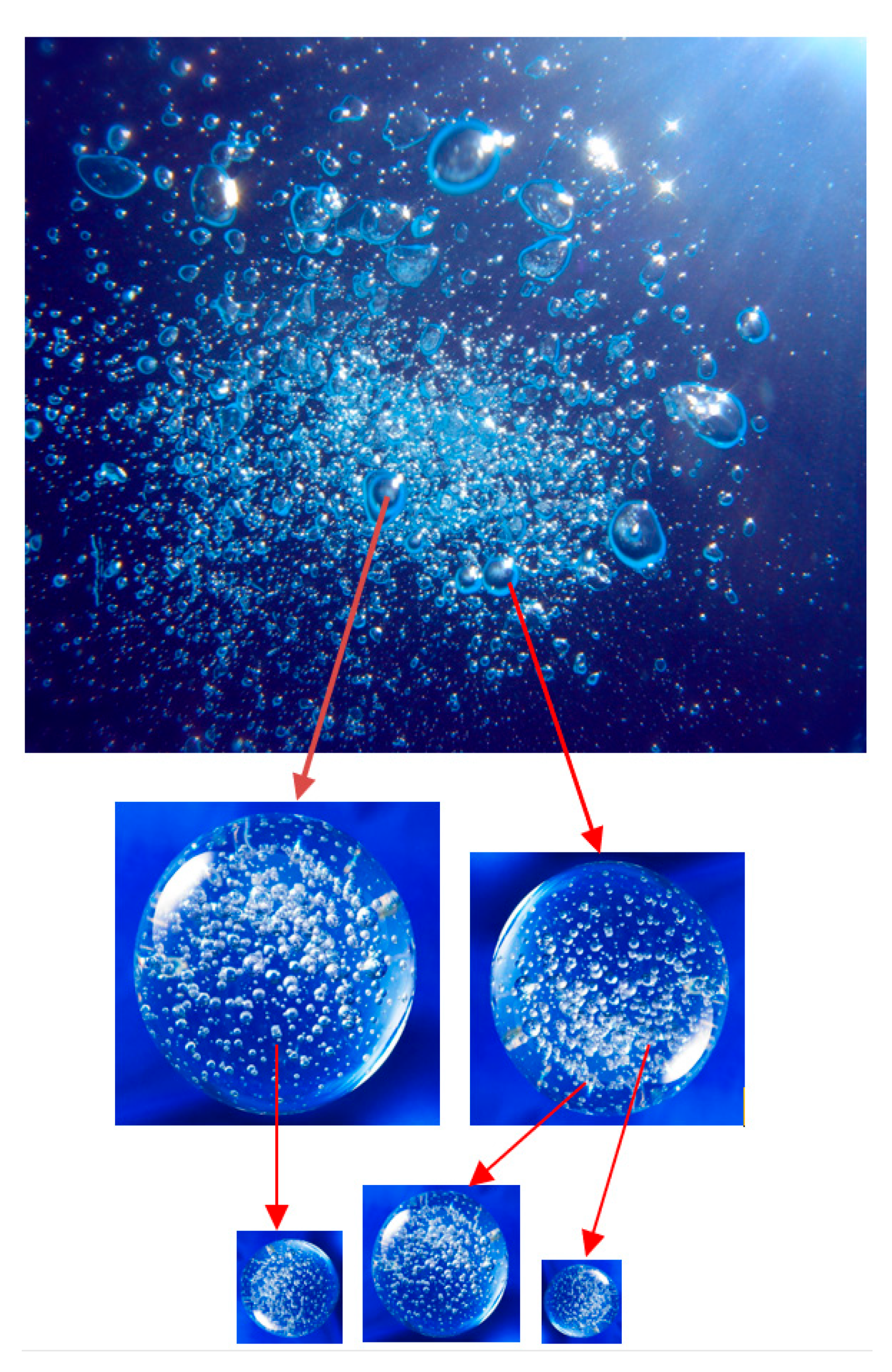

This result shows that the average vacuum extension on the segment ]

rb, ∞[ is compressed by the value ~

rb, in all radial directions due to the fact that it is displaced from the cavity with radius (25.A1). This result is similar to an air bubble in a liquid (

Figure 2.A.1).

The difference between the initial (non-curved) state of a local area of vacuum and its actual (curved) state is determined by the difference [

21]

where

are the components of the metric tensor of the non-curved vacuum from the metric (13.A1).

Figure 2.A1.

Air bubble in liquid.

Figure 2.A1.

Air bubble in liquid.

The relative elongation of the vacuum region in this case is [

21]

whence it follows [

21]

and

The uncarved state of the vacuum section under consideration is given by the metric (13.A1), therefore, substituting the components

gii0(–) and

gii(–), respectively, from (13.A1) and (20.A1) into (29.A1), we obtain the relative elongation of the vacuum in each radial direction in the region from

rb to ∞

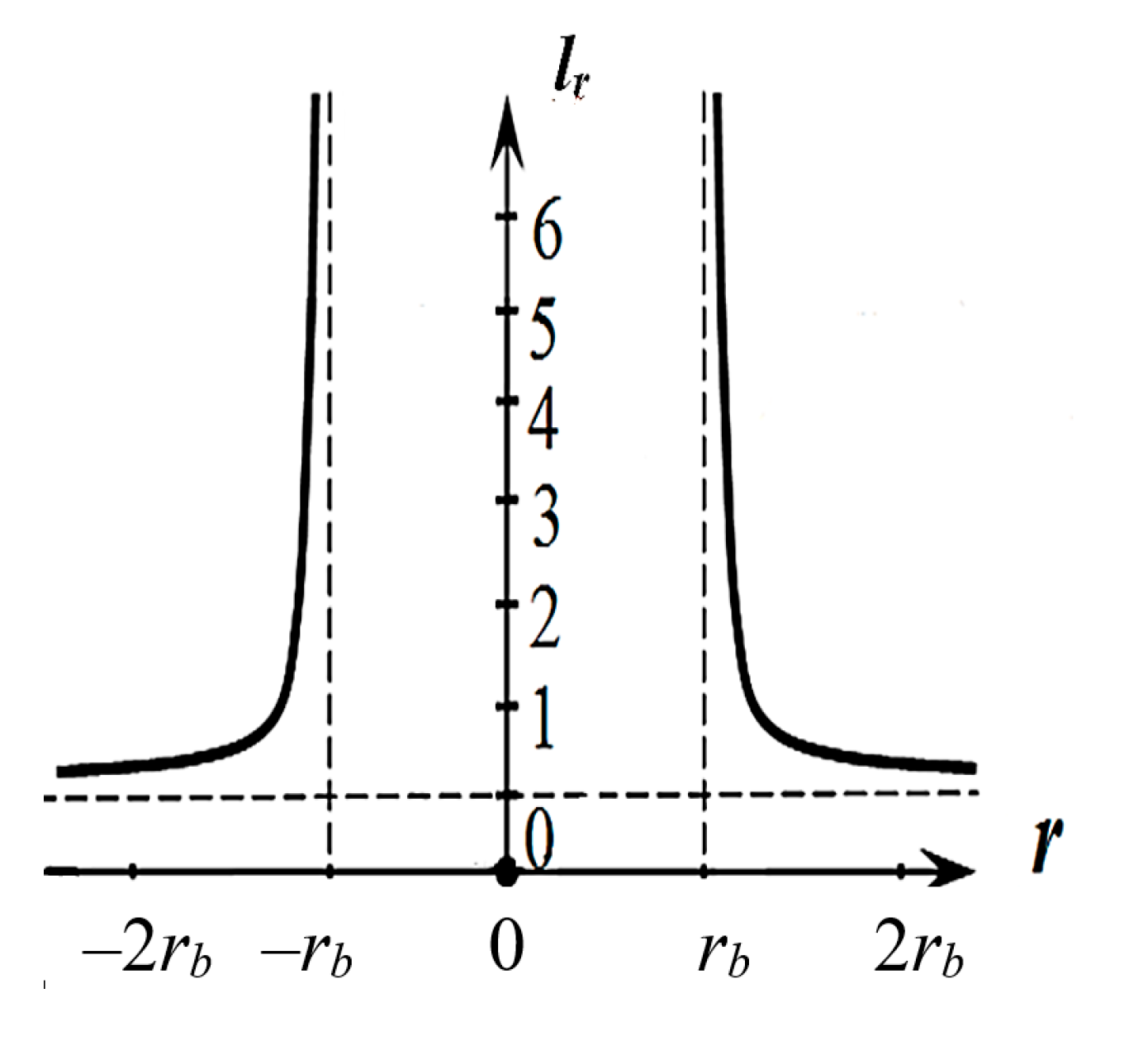

The graph of the function

lr(–) (30.A1) is shown in

Figure 3.A1. For

r = rb, this function tends to infinity, and for

r <

rb it becomes imaginary.

Figure 3.A1.

Graph of the function lr(–) – the relative elongation of the vacuum in the outer shell surrounding the spherical cavity. The calculation was performed at rb = 2, using the software MathCad 15.

Figure 3.A1.

Graph of the function lr(–) – the relative elongation of the vacuum in the outer shell surrounding the spherical cavity. The calculation was performed at rb = 2, using the software MathCad 15.

Here we will not discuss the question: – What is inside the cavity with radius rb, if the vacuum is displaced from there? When considering the second and third Einstein vacuum equations (8) and (43), this problem will be solved by itself.

Thus, averaging the metrics (11.A1) and (11.A1) leads to a metric-dynamic description of a stable vacuum formation of the "air bubble in liquid" (see

Figure 3.A1) type, while these metrics alone do not lead to such results.

Averaging the metrics (14.A1) and (15.A1) allows you to get similar results, but with the opposite signature

Appendix 2

The Standard Model of Elementary Particles from the Algebra of signatures

1.A2 Models ofхi+-«quark» andxi–-«antiquark» in the Algebra of signatures

The fundamentals of "Algebra of signatures" and "Stochastic Metraphysics" (that is, fully geometrized physics from the standpoint of Algebra of signatures) are described in [

16,

17].

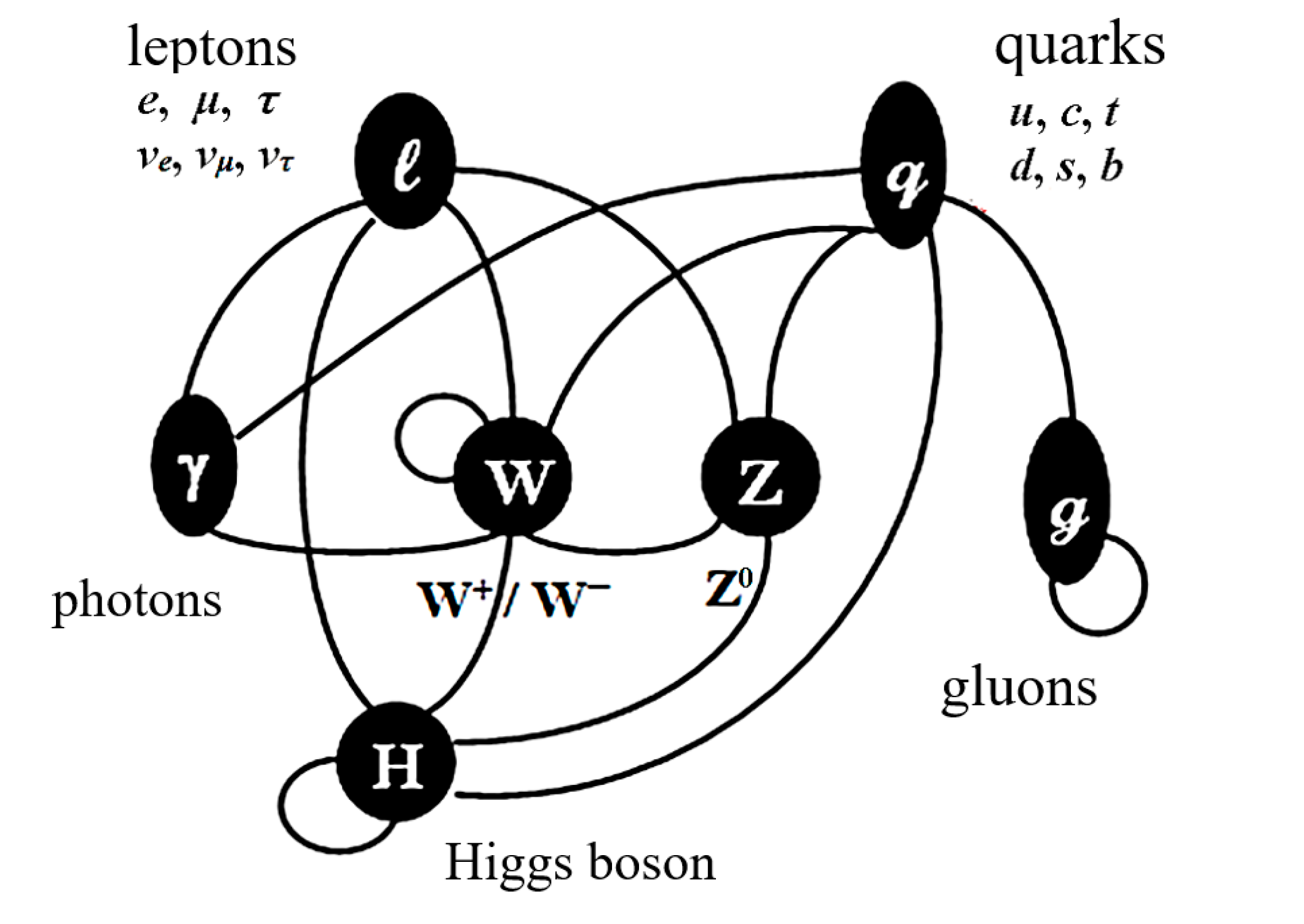

This Appendix contains only the main conclusions of the Algebra of signatures related to the Standard Model of elementary particles (

Figure 1.A2).

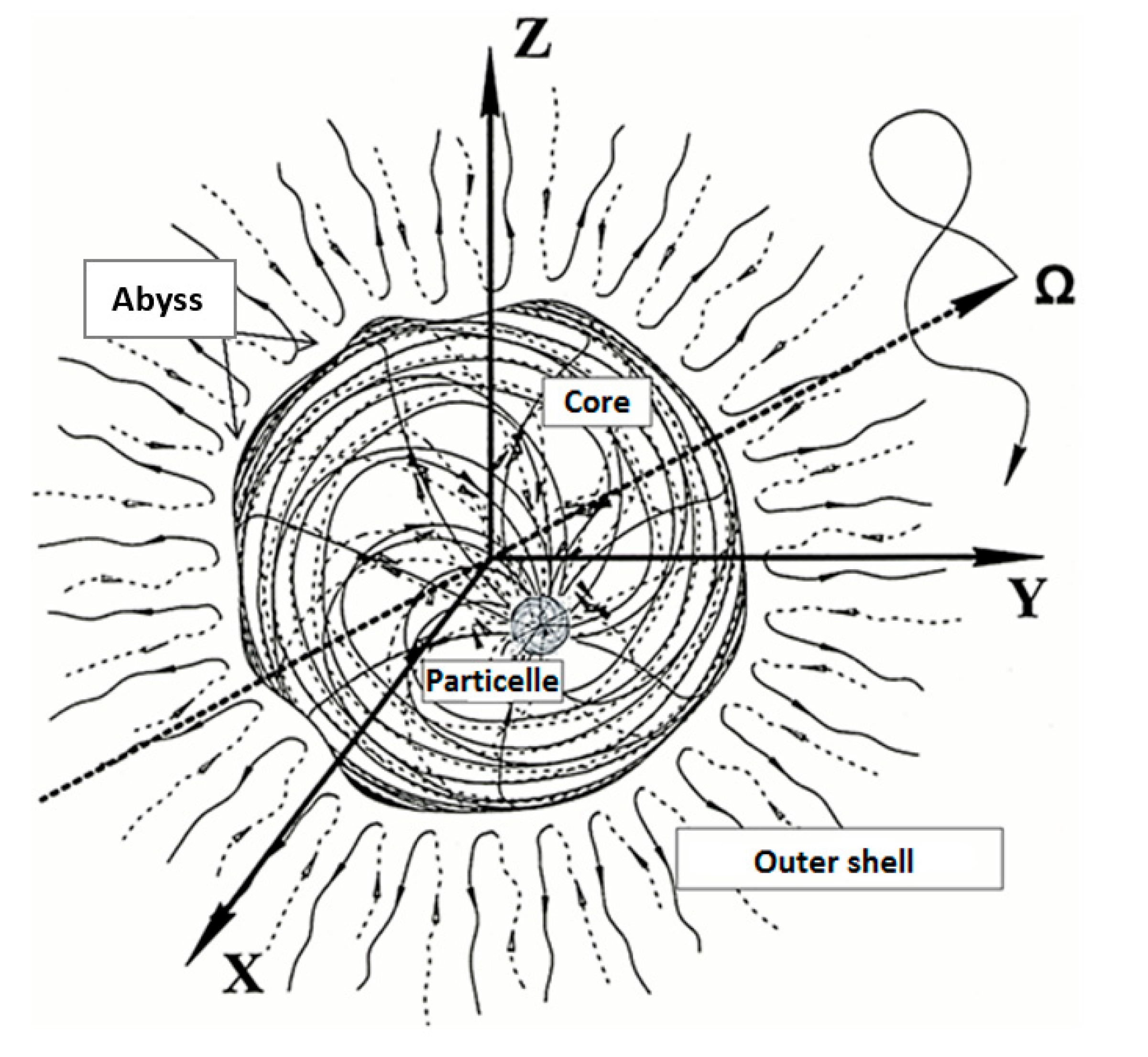

Figure 1.A2.

Elements of the Standard Model of elementary particles.

Figure 1.A2.

Elements of the Standard Model of elementary particles.

In the above article, it was conditionally assumed that an «electron» is a spherical convexity in empty space (i.e., the Einstein vacuum), which is described by a set of metrics (79) – (87) with the signature (+ – – –); and a «positron» is the exact opposite copy of an «electron», i.e. spherical concavity in the Einstein vacuum, which is described by a set of metrics (89) – (97) with an inverted signature (– + + +).

The Algebra of signatures takes into account all 16 signatures (37), and the "building material" of the entire variety of observed objects are «quarks» and «antiquarks»:

"Convex-concave" multilayer spherical formation

with one of the following signatures:

consisting of:

The outer shell of thexi+-«quark» orxi–-«antiquark»

in the interval [

r5, r6] (Figure 8)

The core of thexi+-«quark» orxi–-«antiquark»

in the interval [

r6, r7] (Figure 8)

The shelt of thexi+-«quark» orxi–-«antiquark»

in the interval [0

, ∞]

where

r5 ~ 10

–3 cm,

r6 ~10

–13 cm,

r7 ~10

–24 cm.

Signatures, colors and names of all 16 possible xi+-«quarks» and xi–-«antiquarks» presented in Table 1.A2.

Note that within the framework of the Algebra of signatures, these 16 xi+-«quarks» and xi–-«antiquarks» refer not only to elementary particles, but also to any other spherical formations from the hierarchy (76). Only instead of radii r5 , r6 , r7 in metrics (1.П2) – (11.П2) it is necessary to substitute accordingly: for bacteria r4 , r5 , r6; for stars r3 , r4 , r5; for galaxies r2 , r3 , r4 etc.

Table 1.A2.

.

| «Quarks» |

«Antiquarks» |

| Signature type |

10 metrics

type (1.A2) - (11.A2)

with signature: |

xi+-«quarks» |

10 metrics

type (1.A2) - (11.A2)

with signature: |

xi–-«antiquarks» |

Color of «quarks»

and «antiquarks» |

1–3 |

(+ – – –) |

ey+-«quark» («electron») |

(– + + +) |

ey–-«antiquark» («positron») |

yellow |

3–1 |

(+ + + –)

(+ + – +)

(+ – + +) |

dr+-«quark»

dg+-«quark»

db+-«quark» |

(– – – +)

(– – + –)

(– + – –) |

dr–-«antiquark»

dg–-«antiquark»

db–-«antiquark» |

red

green

blue |

2–2 |

(+ – – +)

(+ – + –)

(+ + – –)

|

ur+-«quark»

ug+-«quark»

ub+-«quark» |

(– + + –)

(– + – +)

(– – + +) |

ur–-«antiquark»

ug–-«antiquark»

ub–-«antiquark» |

red

green

blue |

| 4 |

(+ + + +) |

iw+-«quark»

|

(– – – –) |

iw–-«antiquark» |

white |

For example, let's represent a

ur–-«antiquark» in expanded form:

"Convex-concave" multilayer spherical formation

with the signatures (– + + –), consisting of:

The outer shell of theur–-«antiquark»

in the interval [

r5, r6] (Figure 8)

The core of the ur–-«antiquark»

in the interval [

r6, r7] (Figure 8)

The shelt of the ur–-«antiquark»

in the interval [0

, ∞]

where

r5 ~ 10

–3 cm,

r6 ~10

–13 cm,

r7 ~10

–24 cm.

Let's introduce the notation for 16 types of spherical formations:

10* metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (+ – – –) – yellow ey–-«quark» («electron»);

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (– + + +) – yellow ey+-«antiquark» («positron»);

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (+ + + –) – red dr+-«antiquark»;

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (+ + – +) – green dg+-«antiquark»;

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (+ – + +) – blue db+-«antiquark»;

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (– – – +) – red dr–-«quark»;

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (– – + –) – green dg–-«quark»;

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (– + – –) – blue db–-«quark»;

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (+ – – +) – red ur+-«antiquark»;

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (+ – + –) – green ug+-«antiquark»;

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (+ + – –) – blue ub+-«antiquark»;

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (– + + –) – red ur–-«quark»;

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (– + – +) – green ug–-«quark»;

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (– – + +) – blue ub–-«quark»;

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (– – – –) – white iw–-«quark»;

10 metrics of the form (12.A2) with signature (+ + + +) – white iw+-«antiquark». |

(22.A2) |

*10 metrics (12.A2), because Shelt type (21.A2) refers to both the "core" and the "outer shell" of the corresponding xi–-«quark» or xi+-«antiquark» (). Thus, 5 metrics describe the "core", and 5 metrics describe the "outer shell" of each xi–-«quark» and xi+-«antiquark».

Of the spherical formations (22.A2), only a convex formation are stable – «electron» (ey–-«quark») with the signature (+ – – –) and a concave formation is a “positron” (ey+-«antiquark») with signature (– + + +), because they consist of solutions of Einstein's field equations (8), which is the stability condition. All other spherical formations from the list (22.A2) are unstable, because do not satisfy the conditions of stability (8). That is, when substituting the components of metric tensors from metrics (1.A2) – (11.A2) with any other signature except (+ – – –) and (– + + +) into Eq.s (8), equality will not work.

At the same time, out of 16 xi+-«quark» and xi–-«antiquark» from the list (22.A2) it is possible to compose averaged stable spherical formations with signatures (+ – – –) or (– + + +). This will be shown in the following paragraphs.

2.A2 Models of «proton» and «antiproton» in the Algebra of signatures

On average, stable spherical formations with signatures (+ – – –) or (– + + +) can be composed of two different-colored

u-«quarks» (or

u-«antiquarks») and one

d-«quark» (or

d-«antiquark») from the list (22.A2):

dк+(+ + + –)

uз– (– + – +)

uг– (– – + +)

р1–(– + + +) +

|

(23.A2)

|

dз+ (+ + – +)

uг– (– – + +)

uк– (– + + –)

p2– (– + + +) +

|

( (24.A2)

|

dг+(+ – + +)

uк–(– + + –)

uз–(– + – +)

p3–(– + + +) +

|

(25.A2) |

where

pi– are three possible states of

pi–-«proton» (i = 1, 2, 3) with signature (– + + +)

dк– (– – – +)

uз+ (+ – + –)

uг+ (+ + – –)

р1+ (+ – – –) +

|

(26.A2) |

dз– ( – – + –)

uг+ ( + + – –)

uк+ ( + – – +)

р2+( + – – –) + |

(27.A2) |

dг– ( – + – –)

uк+ ( + – – +)

uз+ ( + – + –)

р3+( + – – –)+

|

(28.A2) |

where pi+ are three possible states of pi+-«antiproton» with signature (+ – – –).

In a more compact form, the states a

pi–-«proton» and

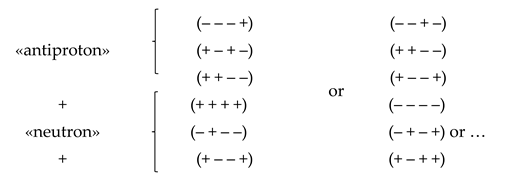

pi+-«antiproton» can be represented as

This type of recording of the states of the «proton» and «antiproton» almost completely coincides with the recording of the states of the proton and antiproton in modern quantum chromodynamics, on which the Standard Model of elementary particles is based.

The difference, however, is that in the Standard Model, protons are made up of quarks and antiprotons are made up of antiquarks, while in the Algebra of signatures pi–-«proton» and pi+-«antiproton» are made up of xi+-«quarks» and xi–-«antiquarks». Therefore, in the Algebra of signatures, there is no problem associated with the baryon asymmetry of the Universe.

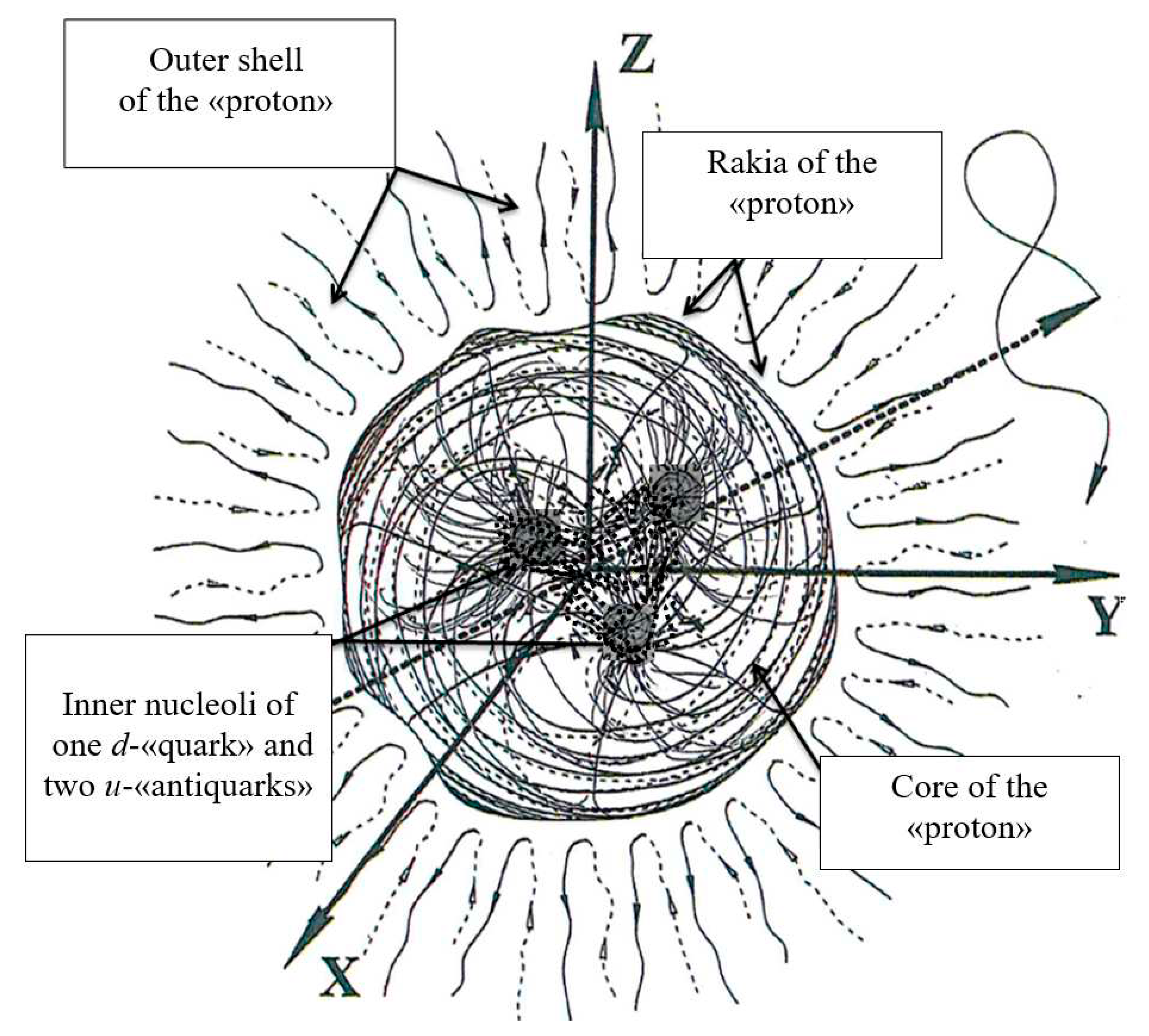

For example, let's imagine a multilayer metric-dynamic model of

pi–-«proton» (23.A2)

dк+(+ + + –)

uз– (– + – +)

uг– (– – + +)

р1+(– + + +) +

|

|

On average, a "concave" multilayer vacuum formation

with a common signature (– + + +)

"Convex-concave" multilayer spherical formation

with the signatures (+ + + –), consisting of:

in the interval [

r5, r6] (

Figure 1.A2)

in the interval [

r6, r7] (

Figure 1.A2)

in the interval [0

, ∞]

"Convex-concave" multilayer spherical formation

with the signatures (– + – +), consisting of:

in the interval [

r5, r6] (

Figure 1.A2)

in the interval [

r6, r7] (

Figure 1.A2)

in the interval [0

, ∞]

"Convex-concave" multilayer spherical formation

with the signatures (– – + +), consisting of:

in the interval [

r5, r6] (

Figure 1.A2)

in the interval [

r6, r7] (

Figure 1.A2)

in the interval [0

, ∞]

where

r5 ~ 10

–3 cm,

r6 ~10

–13 cm,

r7 ~10

–24 cm.

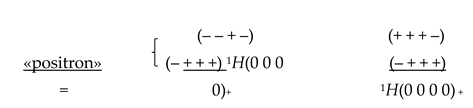

Figure 1.A2.

Core of the «proton» consists of 3 practically superimposed cores: the core of one d-«quark» and of two cores u-«antiquarks». The inner nucleoli of these 3 "quarks" are in constant chaotic movement and interweaving with each other.

Figure 1.A2.

Core of the «proton» consists of 3 practically superimposed cores: the core of one d-«quark» and of two cores u-«antiquarks». The inner nucleoli of these 3 "quarks" are in constant chaotic movement and interweaving with each other.

When averaging homogeneous terms in metrics (32.A2) – (40.A2), is obtained a set of metrics (89) – (97) describing the metric-dynamic state of the «positron». However, it should be expected that the radius of the core of the «protons», consisting of the cores of 1 «quark» and 2 «antiquarks», will be greater than the radius of the core of the «positron», because the inner nucleoli of the three «quarks» are difficult to interact, pushing each other away from the common center

r = 0 (see

Figure 1.A2).

The problem of the confinement of three convex-concave spherical formations: dr+-«quark», ug–-«antiquark» and ub–-«antiquark» is solved by itself, since each xi+-«quark» or xi–-«antiquark» from list (22.A2), except ey– and ey+, are unstable deformed states of vacuum.

Separately

dr+-«quark»,

ug–-«antiquark» and

ub–-«antiquark» cannot exist for a long time, because the metrics describing them (32.A2) – (40.A2) are not solutions of Einstein's vacuum equation (8). Only together, they form a stable on average "concave" vacuum formation «proton» (see

Figure 1.A2), each averaged layer of which satisfies the stability condition (8).

The centers of the «quarks»

dr+,

ub– and

ub– should wander so chaotically about the common center

r = 0 and relative to each other (see

Figure 1.A2) so that only on average their centers coincide with the common center of the «proton» cores: <

rr> =

r = 0, <

rg> =

r = 0, <

rb> =

r = 0. Therefore, we are forced to apply not only the metric-dynamic, but also the statistical description of intranuclear processes, which partly considered in [

16,

17].

The set of metrics (32.A2) – (40.A2) when using the mathematical techniques given in [

16,

17], allows to extract information about the set of processes and sub-processes occurring both inside the «proton» core and in its "outer shell".

A serious difference between the Algebra of signatures (AS) and the Standard Model of Elementary Particles (SMEP) is that the AS not only largely coincides with the quantum chromodynamics of SMEP, but also extends to spherical objects of any scale.

For example, if in the metrics (1.A2) – (40.A2) we substitute instead of radii:

respectively, the radii from the hierarchical sequence (76):

then we get stellar metric Chromodynamics.

Similarly, if from the same sequence (76) we substitute into metrics (32.A2) – (40.A2), respectively, the radii

then we get galactic metric Chromodynamics, and so on.

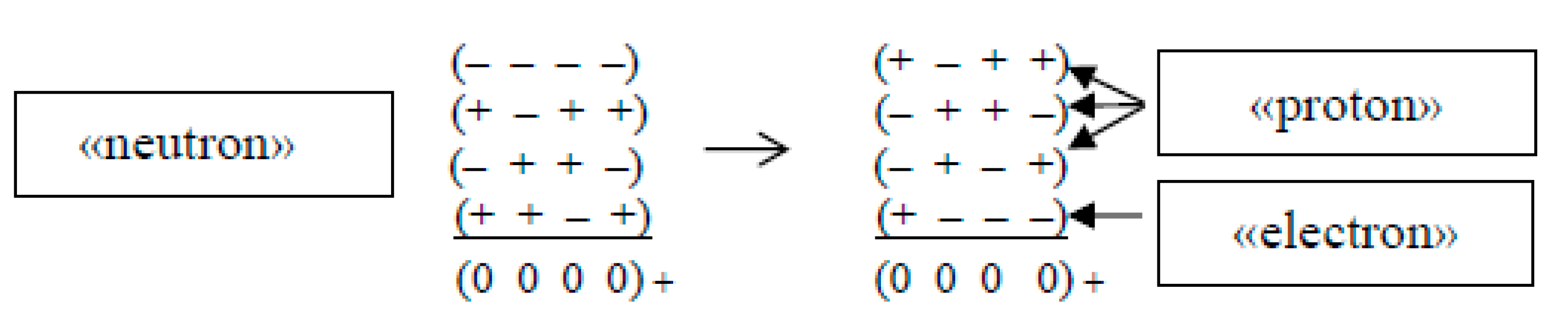

3.A2 The «neutron» model in the Algebra of signatures

In modern nuclear physics, it is believed that the neutron consists of two d-quarks with a charge of (–1/3)

e and one

u-quark with a charge of (2/3)e (where

e is the electron charge)

As a result of this combination, the neutron turns out to be an electrically neutral particle with a zero total charge (–1/3)e + (–1/3)e + (2/3)e = 0.

In Algebra of signatures of a «particle» consisting of three «quarks» («antiquarks») with a zero “electric” environment are not obtained. Since there is not a single additive combination of three of the 16 signatures (37), leading to a zero signature (0 0 0 0), which actually means that all vacuum currents (flows) in the outer shell of such a «particle» are completely mutual compensated [

17].

The desired result is achieved in the case of rankings consisting of four signatures. Therefore, an "electrically" neutral «particle» («neutron») can have the following topological (nodal) configurations:

iw– (– – – –)

db+ (+ – + +)

ur– (– + + –)

dg+ (+ + – +)

n10 (0 0 0 0) +

|

iw– (– – – –)

dg+ (+ + – +)

dr+ (+ + + –)

ub– (– – + +)

n20 (0 0 0 0) +

|

iw– (– – – –)

db+ (+ – + +)

ug– (– + – +)

dr+ (+ + + –)

n30 (0 0 0 0) +

|

iw– (– – – –)

ug– (– + – +)

db+ (+ – + +)

dr+ (+ + + –)

n40 (0 0 0 0) +

|

(42.A2) |

iw+ (+ + + +)

dg– (– + – –)

ur+ (+ – – +)

dg– (– – + –)

n50 (0 0 0 0) +

|

iw+ (+ + + +)

dg– (– – + –)

dr– (– – – +)

ug+ (+ + – –)

n60 (0 0 0 0) +

|

iw+ (+ + + +)

db– (– + – –)

ug+ (+ – + –)

dr– (– – – +)

n70 (0 0 0 0) + |

iw+ (+ + + +)

ug+ (+ – + –)

db– (– + – –)

dr– (– – – +)

n80 (0 0 0 0) +

|

(43.A2) |

where (43.A2)

iw+ – white iw+-«quark», i.e. 10 metrics of the form (1.A2) with signature (+ + + +);

iw– –white iw+-«antiquark», i.e. 10 metrics of the form (1.A2) with signature (– – – –),

(

i from the word

invisible). These «quarks» are called white because they are practically invisible inside the core of the «neutron», because in terms of topology, they are "point" and "anti-point" [

16,

17]. Apparently, therefore, their presence in the core of the neutron was not detected experimentally, and was not taken into account by the Standard Model.

Thus, within the framework of the Algebra of signatures, eight possible states of the «neutron» can be represented as:

which differs from the neutron of the Standard Model (41.A2) by the presence of barely distinguishable

iw+-«quark» and

iw–-«antiquark».

Due to the complex topological (or signature) metamorphoses inside the core of the «neutron», any permutation of the 4-«quarks-antiquarks» (44.A2) can be rearranged so that inside a given vacuum formation a combination will be obtained, consisting, for example, of a «proton» and an «electron»:

Apparently, this restructuring ("decoupling") a topological node inside the core of a «neutron» and leads to a decay reaction

where

νe is an electronic «neutrino».

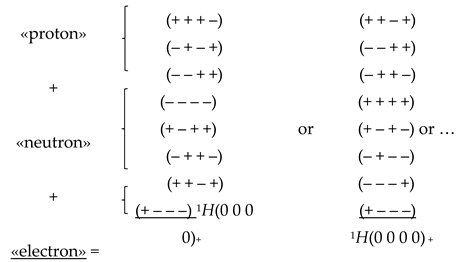

4.A2 The model of the «atom» of hydrogen in the Algebra of signatures

Compared to the neutron, the atom of hydrogen is a much more stable formation.

A hydrogen atom (more precisely deuterium) consists of one proton, one neutron and one electron. Within the framework the Algebra of signature, it also turns out that the deuterium «atom» consists of a «proton», a «neutron» and an «electron». The ranking (topological) equivalent of the nodal configuration of such a spherical formation is:

or

Recall that each signature in these rankings corresponds to 10 metrics of the form (1.A2) with a given signature.

The relationship between the metric extent signature and its topology is shown in §1.11 in [

17].

Each nodal (topological) configuration (47a.P2) or (47b.P2) can be implemented with some probability, and can eventually move from one state to another due to intra-atomic processes while maintaining the overall result: 1Н(0 0 0 0)+.

In the Algebra of Signatures, an «atom” of hydrogen (as well as all other «atoms» included in Mendeleev’s Periodic Table of Elements) can consist of «xi+-quarks» and «xi–-antiquarks». In other words, this theory is initially built in such a way that it does not contain the problem of the baryon asymmetry of the Universe.

It is possible to make many combinations of signatures similar to (47.A2), which reflects the possibilities of "colored" combinatorics of intranuclear metamorphoses. But the topological configuration of this "knot" always remains the same:

taking into account the topological properties of metrics with corresponding signatures (see §1.11 in [

17]), we find that this "knot" consists of 3 intertwined "tori", 4 "oval surfaces" and one "point".

In a similar way, all known chemical elements of the Mendeleev periodic table of elements can be "designed" ("woven"). In this case, the average sizes of the core of «atoms»

rA must depend on the number of x

i+-«quarks» and x

i–-«antiquarks»

A that form these "topological nodes"

The Algebra of signatures extends the approach proposed here to the "construction" of multilayer metric-dynamical models of all «atoms» from the periodic table of elements using Fermi’s «quarks» and «antiquarks» (with characteristic sizes of core r4 ~ 108 cm), to "construction" of metric-dynamical models of "stars» and «planets» with the help of Newton’s «quarks» and «antiquarks» (with characteristic sizes of core r4 ~ 108 cm), as well as for the construction of «galaxies» with the help of Galileo’s «quarks» and «antiquarks» (with characteristic sizes of core r3 ~ 1018 cm), as well as on the construction of «metagalaxies» with the help of Einstein’s «quarks» and «antiquarks» (with characteristic sizes of core r3 ~ 1029 cm), etc.

5.A2 Models of «mesons» and «baryons» in the Algebra of signatures

In quantum chromodynamics, mesons are composed of a quark and an antiquark, and are given by the formula

where

is the color quark triplet (

α = b,,r);

is the color triplet of the antiquark.

Baryons consist of 3 quarks, and are given by the formula

where

εαβγ is a completely antisymmetric tensor.

Almost exactly the same way «mesons» and «baryons» are composed within the Algebra of signatures. Consider a specific example: three varieties of

π-mesons in the theory of strong interactions (quantum chromodynamics) have the following quark structure:

In the Algebra of signatures, for example, three states of the meson

π+ = u– d + is represented as

dк+ (+ + + –)

uз–(– + – +)

π1+ (0 2+ 0 0)+

|

dз+ (+ + – +)

uг– (– – + +)

π2+ (0 0 0 2+)+

|

dг+( + – + +)

uк–( – + + –)

π3+ (0 0 2+ 0)+

|

(53.A2) |

where each signature corresponds to a set of 10 metrics of type (1.A2) with a given signature.

In turn, the quark construction

may have the following signature (topological) analogues: (55.A2)

uк+(+ – – +)

uз–(– + – +)+

–

dк+(+ + + –)

dз–(– – + –)+

π10 (0 0 0 0) |

uз+(+ – + –)

uг–(– – + +)+

–

dз+ (+ + – +)

dг–(– + – –)+

π20 (0 0 0 0) |

uг+(+ + – –)

uк–(– + + –)+

–

dг+ (+ – + +)

dк–(– – – +)+

π30 (0 0 0 0) |

Similarly, within the framework of the Algebra of signatures, all known mesons and baryons of the Standard Model can be "constructed".

The construction of the Algebra of signatures (AS) differs from the constructions of the Standard Model of elementary particles, only by the presence of additional iw+-«quark» and iw–-«antiquark», as well as by the fact that most of the studied AS of multilayer spherical formations consist of intertwining xi+-«quarks» and xi–-«antiquarks», so there is no problem of baryon asymmetry in AS.

6.A2 Models of «bosons» in the Algebra of signatures

«Bosons» are various types of wave (more precisely, helical harmonic) perturbations in vacuum (see §§1.1 – 1.9 in [

17]). In this section, we present the main mathematical models of the Algebra of signatures for these wave disturbances.

a) "Photon" and "antiphoton"

Spiral harmonic perturbation [

17]

we will conventionally call it a «photon» with signature {+ – – –}.

Then a spiral harmonic perturbation propagating in the opposite direction, (57.A2)

cos{(2π /λ)(–сt+x+y+z)}+ i sin{(2π/λ)(–сt+x+y+z)} = ехр{i (2π/λ)(–сt+x+y+z)}= ехр –{i(ω t – k⋅ r)}.

we will conventionally call it an «antiphoton» with the stignature {– + + +}.

The notion of the stignature of an affine space was introduced in §1.8 in [

17].

b) W±-«bosons»

The three color states of the W

+-«boson» are given by the following expressions and their corresponding rankings [

17]

ехр {i 2π /λ (– сt – x – y + z)}×

× ехр {j 2π /λ ( сt – x + y – z)}×

× ехр {k 2π /λ ( сt + x – y – z)}

|

{– – – +}

{+ – + –}

{+ + – –}

{+ – – –}+

|

(58) |

ехр {i 2π /λ (– сt – x + y – z)}×

× ехр {j 2π /λ ( сt + x – y – z)}×

× ехр {k 2π /λ ( сt – x – y + z)}

|

{– – + –}

{+ + – –}

{+ – – +}

{+ – – –}+

|

ехр {i 2π /λ (– сt + x – y – z)}×

× ехр {j 2π /λ ( сt – x – y + z)}×

× ехр {k 2π /λ ( сt – x + y – z)} |

{– + – –}

{+ – – +}

{+ – + –}

{+ – – –}+

|

The three color states of the W

–-«boson»:

ехр {i 2π /λ ( сt + x + y – z)}×

× ехр {j2π /λ (– сt + x – y + z)}×

× ехр {k 2π /λ (– сt – x + y + z)}

|

{+ + + –}

{– + – +}

{– – + +}

{– + + +}+

|

(59) |

ехр {i 2π /λ ( сt + x – y + z)}×

× ехр {j 2π /λ (– сt – x + y + z)}×

× ехр {k 2π /λ (– сt + x + y – z)}

|

{+ + – +}

{– – + +}

{– + + –}

{– + + +}+

|

ехр {i 2π /λ ( сt – x + y + z)}×

× ехр {j 2π /λ (– сt + x + y – z)}×

× ехр {k 2π /λ (– сt + x – y + z)} |

{+ – + +}

{– + + –}

{– + – +}

{– + + +}+ , |

where

i, j, k are imaginary units, form the anticommutative algebra

c) Z0-«bosons»

The six color states of the Z

0-«boson» are given by the following expressions and the corresponding rankings [

17]

ехр { 2π /λ (– сt – x – y – z)}×

× ехр {i 2π /λ ( сt – x + y + z)}×

× ехр {j 2π /λ (– сt + x + y – z)}×

× ехр {k 2π /λ ( сt + x – y + z)}

|

{– – – –}

{+ – + +}

{– + + –}

{+ + – +}

{0 0 0 0}+

|

(61.A2) |

ехр { 2π /λ (– сt – x – y – z)}×

× ехр {i 2π /λ ( сt + x – y + z)}×

× ехр {j 2π /λ ( сt + x + y – z)}×

× ехр {k 2π /λ (– сt – x + y + z)} |

{– – – –}

{+ + – +}

{+ + + –}

{– – + +}

{0 0 0 0}+

|

ехр { 2π /λ (– сt – x – y – z)}×

× ехр {i 2π /λ ( сt – x + y + z)}×

× ехр {j 2π /λ (– сt + x – y + z)}×

× ехр {k 2π /λ ( сt + x + y – z)}

|

{– – – –}

{+ – + +}

{– + – +}

{+ + + –}

{0 0 0 0}+

|

ехр { 2π /λ ( сt + x + y + z)}×

× ехр {i 2π /λ (– сt + x – y – z)}×

× ехр {j 2π /λ ( сt – x – y + z)}×

× ехр {k 2π /λ (– сt – x + y – z)}

|

{+ + + +}

{– + – –}

{+ – – +}

{– – + –}

{0 0 0 0}+

|

ехр { 2π /λ ( сt + x + y + z)}×

× ехр {i 2π /λ (– сt – x + y – z)}×

× ехр {j 2π /λ (– сt – x – y + z)}×

× ехр {k 2π /λ ( сt + x – y – z)}

|

{+ + + +}

{– – + –}

{– – – +}

{+ + – –}

{0 0 0 0}+

|

ехр { 2π /λ ( сt + x + y + z)}×

× ехр {i 2π /λ (– сt + x – y – z)}×

× ехр {j 2π /λ ( сt – x + y – z)}×

× ехр {k 2π /λ (– сt – x – y + z)}

|

{+ + + +}

{– + – –}

{+ – + –}

{– – – +}

{0 0 0 0}+

|

d) «Graviton» (or «landscapeton»)

In the Algebra of signatures, there is another «boson», which is called «graviton» (or «landscapeton») [

17]

ехр {ζ1 2π /λ ( сt + x + y + z)}

× ехр {ζ3 2π /λ ( сt – x – y + z)}×

× ехр {ζ4 2π /λ (–сt – x + y – z)}×

× ехр {ζ5 2π /λ ( сt + x – y – z)}×

× ехр{ζ6 2π /λ (– сt + x – y – z)}×

× ехр {ζ7 2π /λ ( сt – x + y – z)}×

× ехр {ζ8 2π /λ (– сt+ x + y +z)}×

× ехр {ζ1 2π /λ (– сt –x – y – z)}×

× ехр{ζ2 2π /λ ( сt + x + y – z)}×

× ехр{ζ32π /λ (– сt + x + y – z)}×

× ехр{ζ4 2π /λ ( сt + x – y + z)}×

× ехр (ζ5 2π /λ (– сt – x + y + z)}×

× ехр{ζ6 2π /λ ( сt – x + y + z)}×

× ехр {ζ7 2π /λ (– сt + x– y + z)}×

× ехр {ζ8 2π /λ ( сt – x – y – z)} |

{+ + + +}

{– – – +}

{+ – – +}

{– – + –}

{+ + – –}

{– + – –}

{+ – + –}

{– + + + }

{– – – – }

{+ + + – }

{– + + – }

{+ + – +}

{– – + +}

{+ – + +}

{– + – +}

{+ – – –}

{0 0 0 0}+

|

(62.A2) |

where the objects ζm satisfy the anticommutative relations of the Clifford algebra

where

δkm is the Kronecker symbol (

δkm= 0 for

m ≠

k and

δkm= 1 for

m =

k ). One of the possibilities for determining the objects

ζm and the Kronecker symbol

δkm is presented below:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7.A2 Conclusions on Annex 2

Metric-dynamic models of all kinds of «neutrinos», «muons» and «antimuons», τ-«leptons»,

c+,s+,b+,t+-«quarks» and

c–,s–,b–,t–-«antiquarks», as well as a geometrized description of the main force interactions: electrostatic, electromagnetic, weak and nuclear are given in chapters 3 – 10 [

17].

Thus, taking into account the superposition of stably curved metric spaces with all 16 possible signatures (37)

allow metric-statistical description of almost all elements of the Standard Model of elementary particles, except for the Higgs boson.

In the massless Algebra of signatures (or stochastic metaphysics) proposed here, there is no concept of "mass", so there is no need to introduce the concept of a field that provides a mechanism for spontaneous breaking of electroweak symmetry, and, accordingly, about the quanta of this field - Higgs bosons. However, it is possible that in a fully geometrized theory, metric-dynamic models of vacuum formations with characteristics similar to those of these bosons will arise.

Note that if in the aggregate of metrics of the form (78), (88), (12.A2) and (31.A2) instead of:

r5 ~ 10–3 cm is the characteristic radius of the «biological cell»;

r6 ~10–13 cm is the characteristic radius of the «electron» core;

r7 ~ 10–24 cm is the characteristic radius of the «proto-quark» core,

substitute accordingly, for example,

r3 ~ 1018 cm is the radius commensurate with the radius of the «galaxy» core;

r4 ~ 108 cm is the radius commensurate with the radius of the core of a «star» («planet»);

r5 ~ 10–3 cm is the radius commensurate with the size of a «biological cell»;

then we get a practically similar multilayer metric-dynamic description of spherical formations on a stellar-planetary scale.

Whereas, if we substitute

r2 ~ 1029 cm is the characteristic radius of the core of the «metagalaxy»;

r3 ~ 1018 cm is the characteristic radius of the core of the «galaxy»;

r4 ~ 108 cm – characteristic radius, the core of a "star" or «planet»,

then we get a description of spherical formations of a galactic scale, etc.

Thus, in the opinion of the author, has been obtained a universal metric-dynamic model of a closed and, at the same time, Ricci-flat universe, inhabited by countless spherical formations of various scales,

The probabilistic formalism of the Standard Model also remains valid, since the cores and nucleoli of stable vacuum formations constantly move chaotically under the influence of neighboring stable spherical formations and many other vacuum fluctuations. The study of the chaotic motion of the core of a vacuum formation led to the derivation of the Schrödinger equation (see Chapters 3 and 4 in [

17]).

Appendix 3

Rakia is a multilayer shell of the core of a spherical formation

Let’s return to the consideration of Ex. (60)

We propose to analyze this expression with respect to one of the spheres (core) included in the hierarchy of nested spherical formations with radii (76).

All subsequent actions can be done with respect to any spherical formation with radius rj from the given hieratic sequence.

Let’s focus on the sphere (core) with a radius of ~ 10–13 cm, which corresponds to the nucleus of an elementary particle («electron», «proton», «neutron», etc.).

Further, instead of r6, we will write re (i.e., r6 = re), meaning for brevity, this value is the radius of the «electron», but remembering that this radius is a characteristic size for all elementary particles.

A simplified case, when the core of an “electron” with a radius

re ≈

r6 ~ 10

–13 cm is located only inside a closed Universe with a radius

Rν, was studied in detail in [

17].

Here we consider the situation when the electron core is built into the hierarchy of 10 nested nuclei with radii (76) (see

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

We write Ex.s (1.A3) with selection of terms containing

re ≈

r6

Let’s introduce the notation

then the Ex. (1.A3) takes the form

which can be written as follows

Similarly, Ex.s (61) – (63) can be represented as

The nearest environment (rakia) of the «electron» core

We investigate how the vacuum behaves in the immediate vicinity of the «electron» core, i.e. in the region

r ≈

re, which is called the «electron» rakia (see Figures 1.A3 and 2.A3). For this, we recall that according to the hierarchical sequence of radii (76)

Radii of the outer (surrounding) cores

|

Radius of the core of the «electron» |

Radii of the cores

|

r1 ~ 1039 cm,

r2 ~ 1029 cm,

r3 ~ 1018 cm,

r4 ~ 108 cm,

r5 ~ 10–3 cm |

r6 = re ~ 10–13 cm |

r7 ~ 10–24 cm,

r8 ~10–34 cm,

r9 ~ 10–45 cm,

r10 ~ 10–55 cm |

Substitute these values of

rk into Ex.s (3.A3), as a result, for

r ≈

re , on

r ≠

re we get

In this case, the Ex.s (5.A3) – (8.A3) are simplified and become approximately equal

However, when

r =

re from Ex.s (5.A3) – (8.A3) follows

» core, see Figures 1.A3 and 2.A3) is significantly influenced by all the global spheres in which it is immersed (see

Figure 5). Also, this area is affected by all the spheres included inside the core of the «electron»

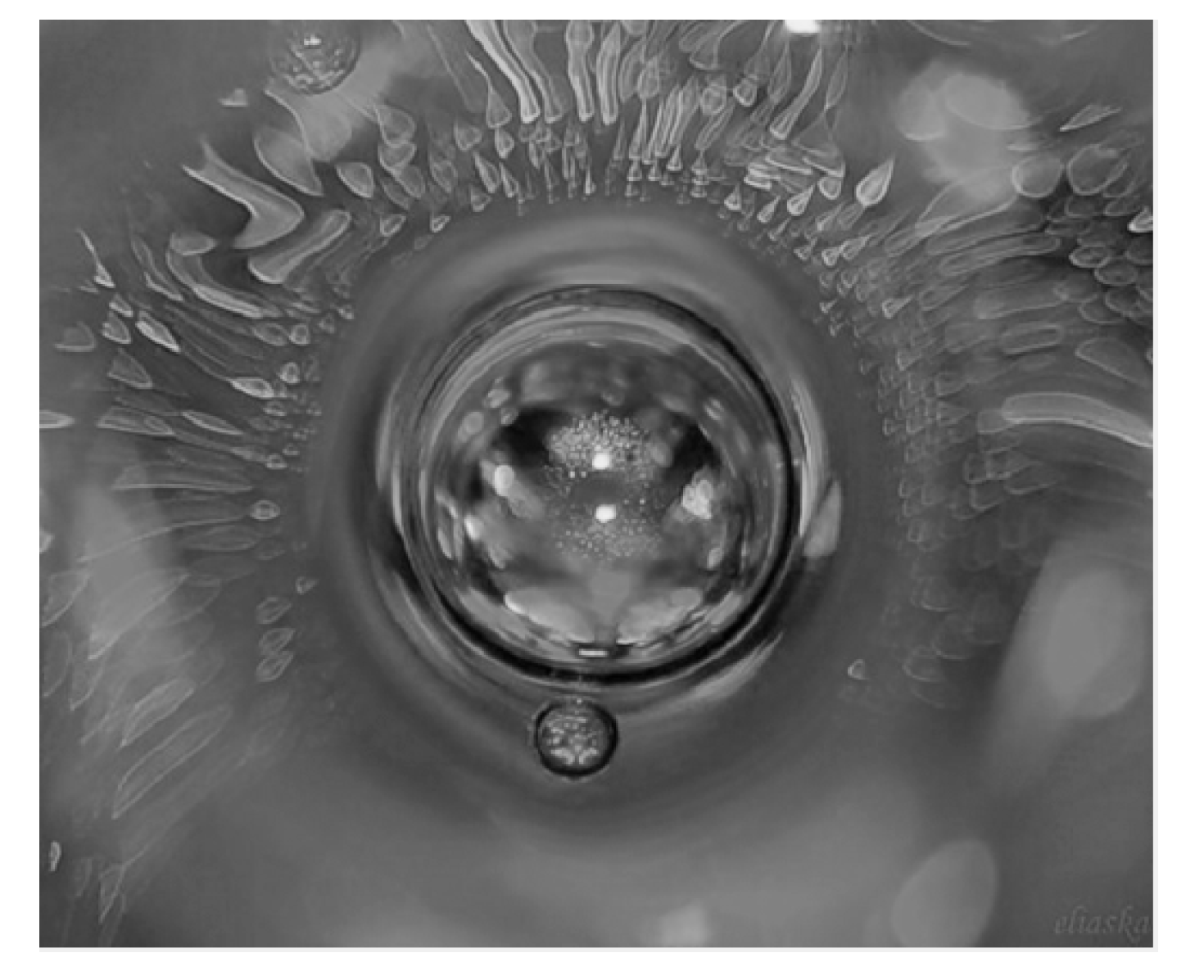

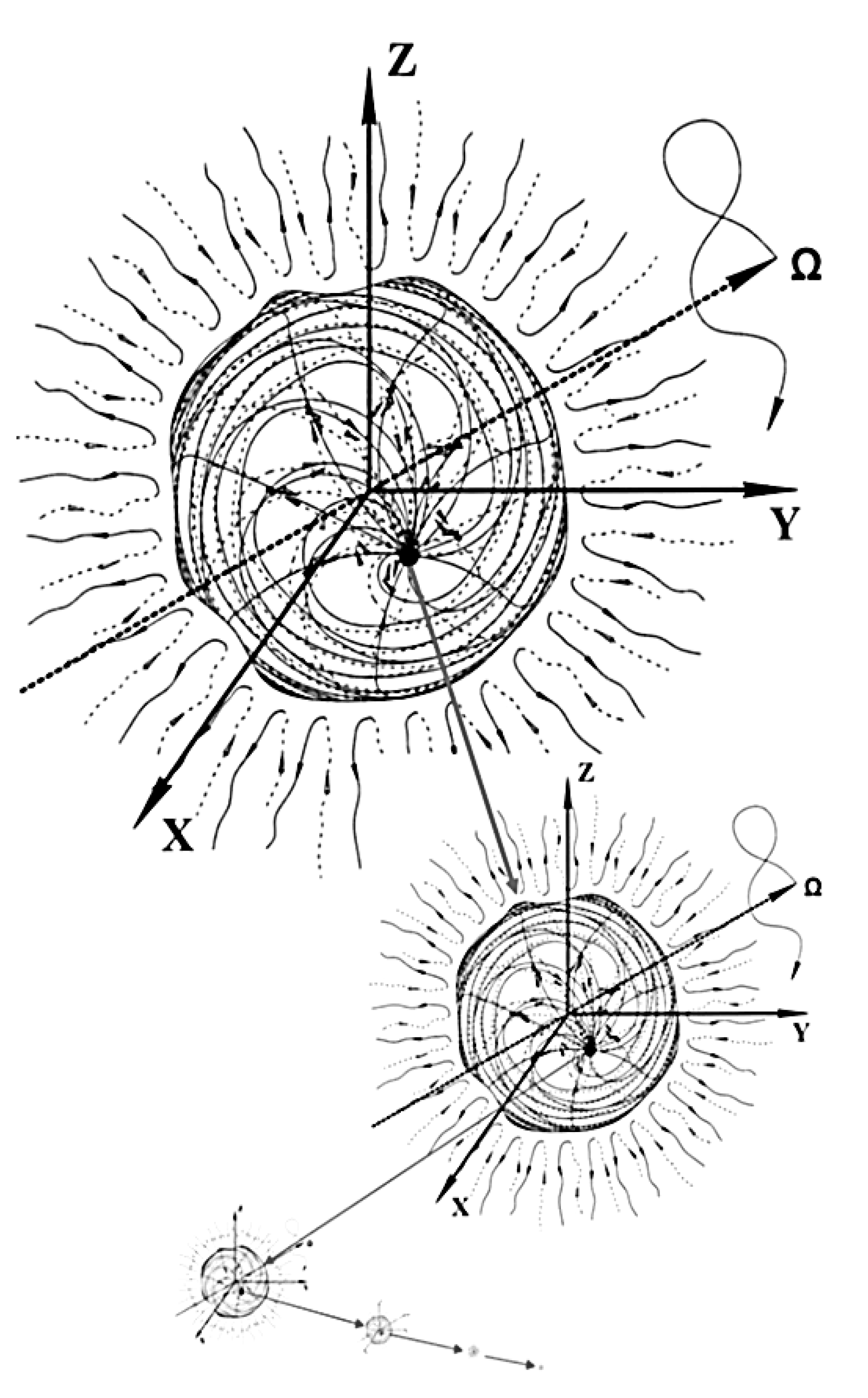

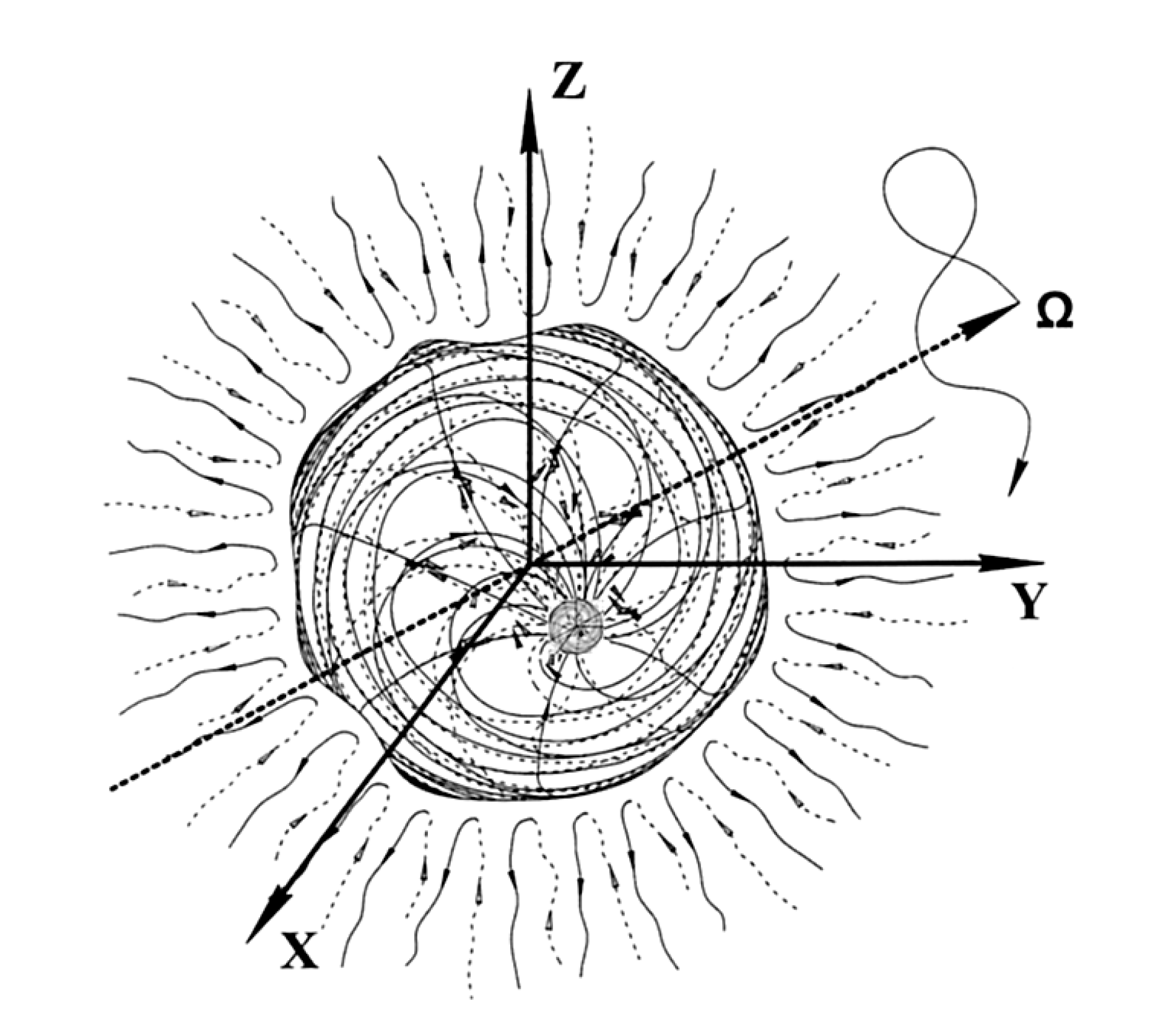

Figure 1.A3.

"Rakia" of an «electron» (i.e. the area surrounding its nucleus).

Figure 1.A3.

"Rakia" of an «electron» (i.e. the area surrounding its nucleus).

It looks as if the core of the "electron" was wrapped in a multi-layered, intricately intertwined shell (rakia). Each layer of such a shell (rakia) is connected with the corresponding “sphere” of a spherical formation, inside which the «electron» core is located, and with spherical formations, which is inside the «electron» core.

In other words, in the immediate environment of the «electron» core there is a spherical layer associated with a spherical Universe; there is a layer associated with a spherical metagalaxy; there is a layer associated with the spherical halo of the galaxy; there is a layer connected with a spherical star or planet, inside of which the core of the «electron» under consideration is located, etc. Together, these layers form a multilayer "rakia" (core’s shell) of the «electron».

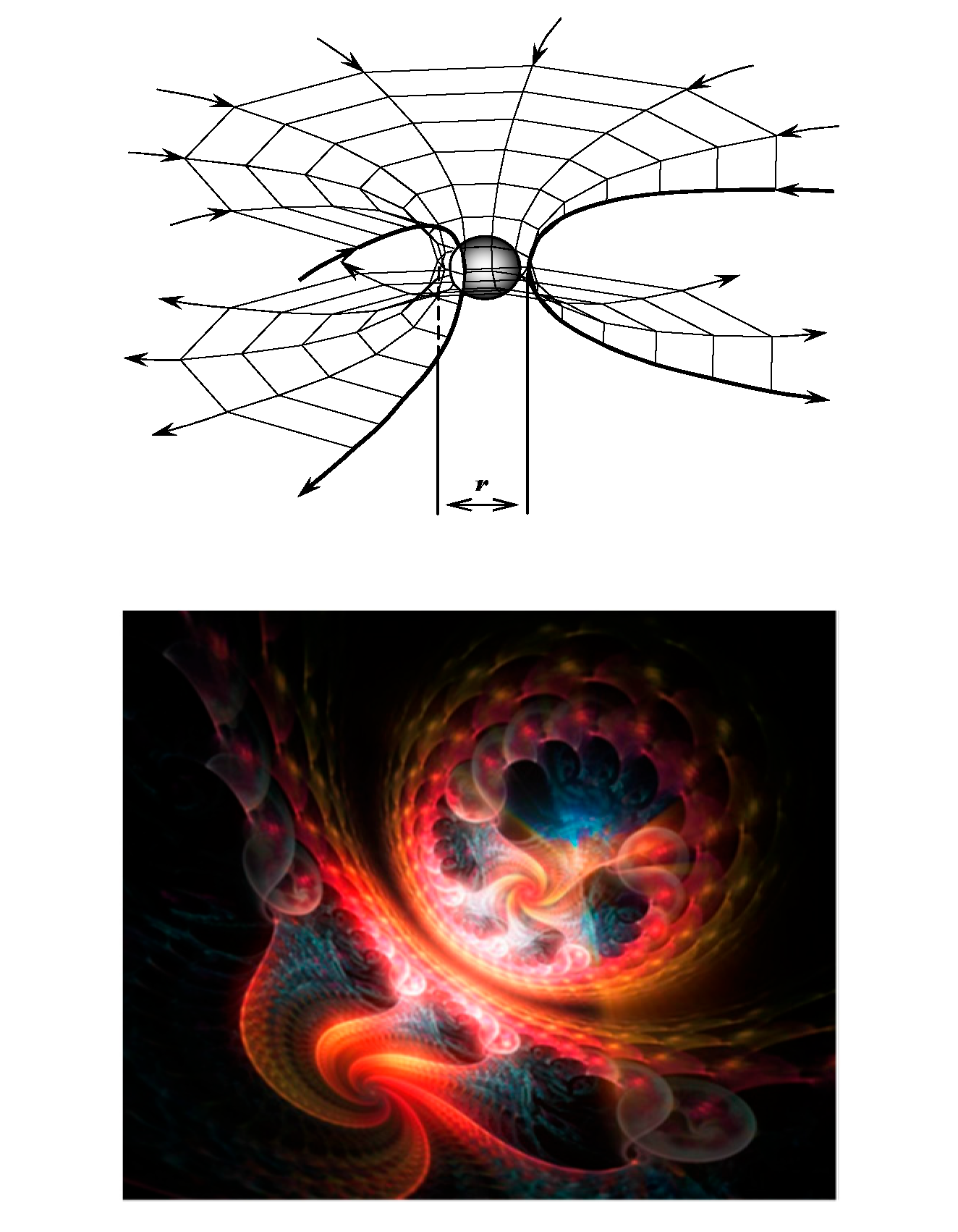

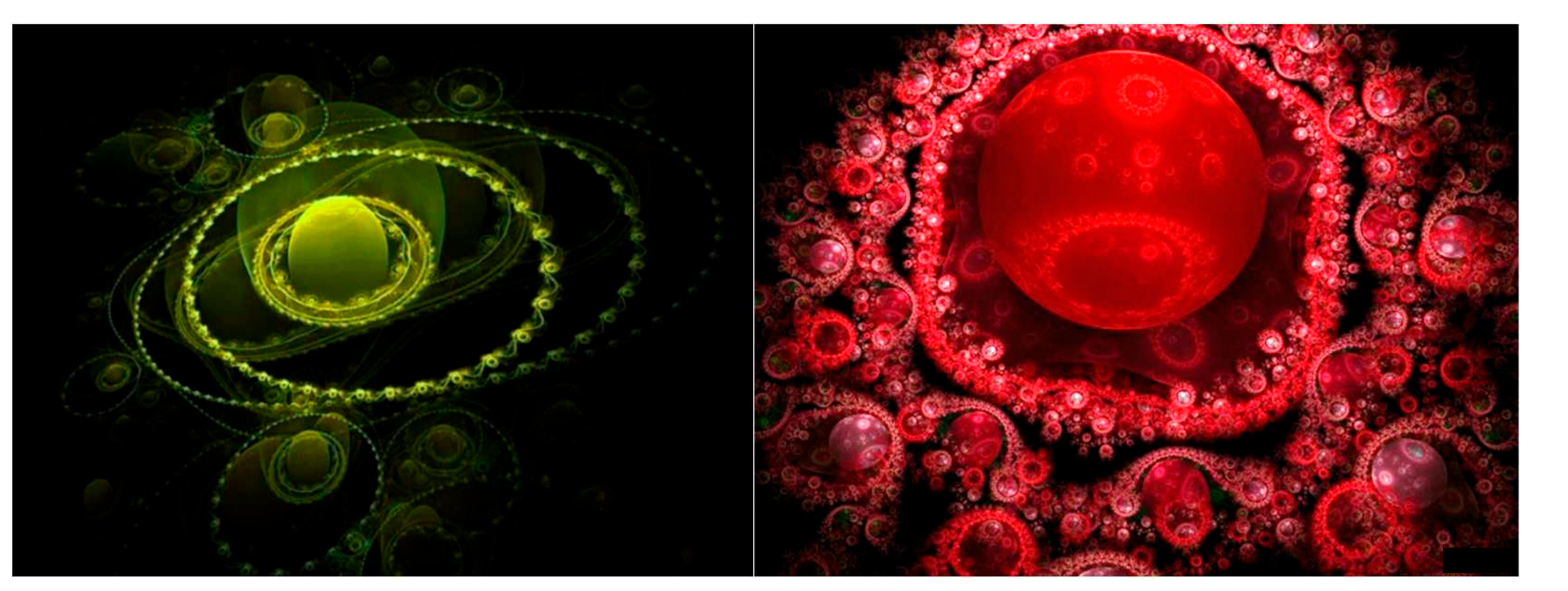

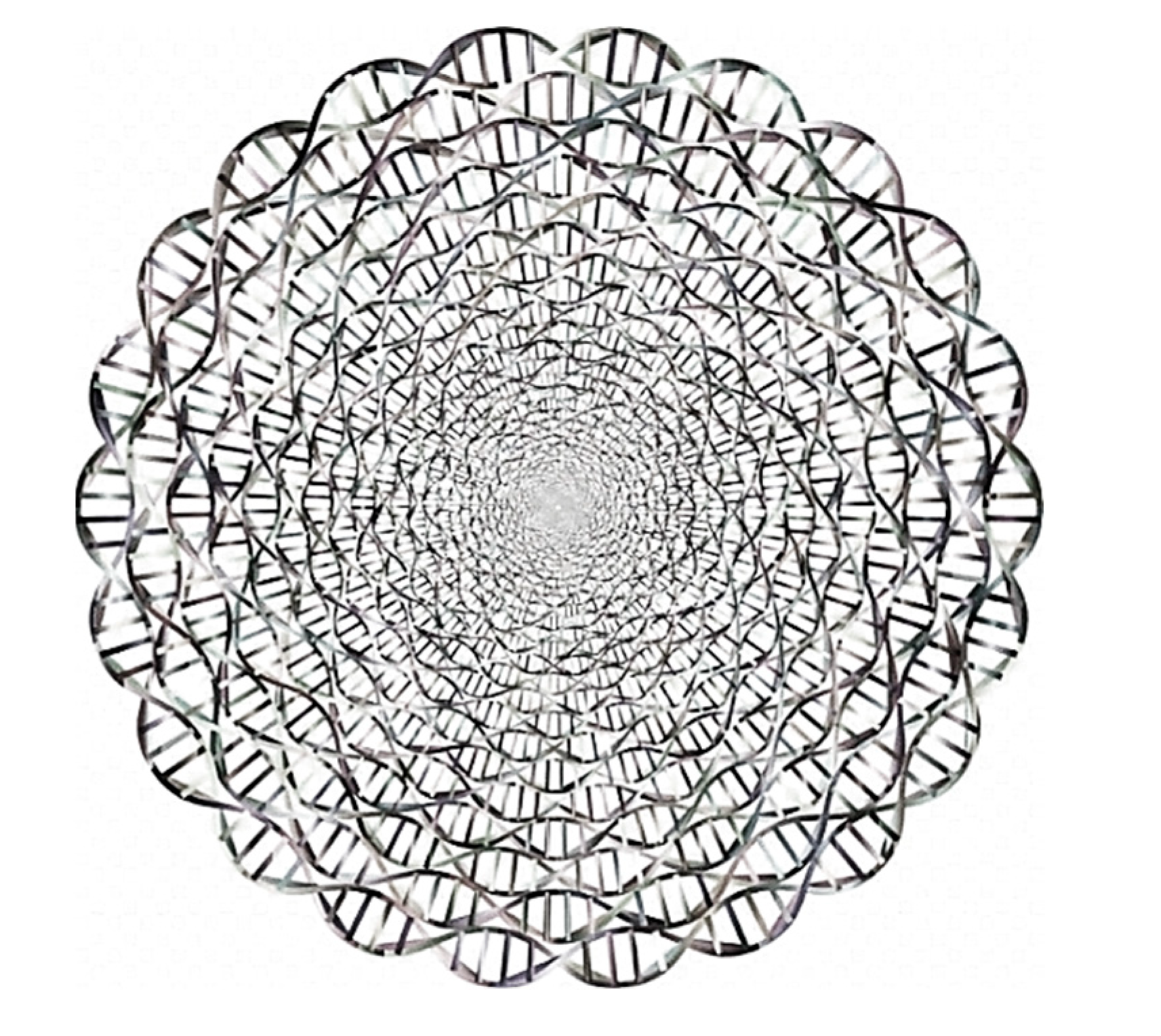

On

Figure 2.A3 shows fractal illustrations that reflect one or another aspect of “rakia”, i.e. a multilayer shell surrounding the core of a spherical formation (in particular, an «electron»). At the same time, each layer of this multilayer shell is associated with the corresponding a more global (external) spherical formations, and with a much smaller (internal) spherical formations (see

Figure 5).

Figure 2.A3.

Fractal illustrations of various aspects of the manifestation of "rakia" (multilayer shell) surrounding the core of the spherical formation (in particular, «electron»).

Figure 2.A3.

Fractal illustrations of various aspects of the manifestation of "rakia" (multilayer shell) surrounding the core of the spherical formation (in particular, «electron»).

The metric-dynamic structure of the vacuum around the core of the «electron»

We consider the vacuum state at a somewhat remote distance from the «electron» core from its outer side

r ≥

re =

r6 (i.e., in the region ~ 10

–8 cm ≥

r ≥ 10

–13 cm). In this case, expressions (3.A3) take the approximate form

and the components of the metric tensor (5.A3) – (8.A3) become approximately equal

The metric-dynamic structure of the vacuum inside the core of the «electron»

Let's consider the state of vacuum extension inside the core of the «electron», at

r ≤

re =

r6 (i.e. in the region of 10

–13cm ≥

r ≥ 10

–21cm). In this case, Ex.s (3.A3) take an approximate form

and the components of the metric tensor (5.A3) – (8.A3) are approximately equal to

Metric-dynamic models (structures) of «electron» and «positron»

We collect all the obtained metrics (13.A3) – (16.A3), (18.A3) – (21.A3) and (23.A3) – (26.A3) together, and “construct” from them an approximate multilayer metric-dynamic model (structure) of «electron», which is included in the sequence of nested spherical formations (76):

all metrics with signature (+ – – –)

The outer environment of the «electron» core

Rakia (multilayered shell) of the «electron» core

The core of the «electron»

The shelt of the «electron»

«Positron» is a negative metric-dynamic copy of «electron». If an «electron» is a local, intricately intertwined convexity of vacuum extension, then a «positron» is its local concavity arranged in exactly the same way.

all metrics with signature (– + + +)

The outer environment of the «positron» core

Rakia (multilayered shell) of the «positron» core

The core of the «positron»

The shelt of the «positron»

These model representations are informative enough to consider and solve a large class of problems related to the most subtle interactions of various levels of being.

In the presented multilayer metric-dynamic model of an elementary particle (in particular, an "electron"), each layer of its rakia (i.e. the multilayer shell surrounding the core of this spherical formation) is associated with a spherical formation of a much larger scale, for example, with the rakia of a biological cell, with the rakia of a planet, with the rakia of a galaxy, and the rakia of a metagalaxy, etc., inside which the core of the studied elementary particle is located, as well as with spherical formations of a much smaller scale: with proto-quark cancer, with plankton cancer, with protoplankton cancer, etc., which are located inside the nucleus of the considered elementary particle.

This mathematical apparatus can allow:

- to realize the internal nature of the synchronization of microscopic and macroscopic cyclic processes;

- explain the features of different layers of rakia spherical objects from a hierarchical sequence (76). For example, it is possible that the layers of the planet Earth are associated with the intersection of the influences of some elementary particles, some of atoms, some of a star, some of a galaxy, and some of a metagalaxy, etc.

- distinguish between spherical formations of various scales (in particular, «electron»), which are included in various sequences of nested spheres. For example, according to the mathematical model developed in this article, the rakia (i.e., the shell of the core) of a free «electron» that is only inside the «Universe» differs from the rakia of a free «electron» that is inside the «biological cell» and inside the «Universe», or inside the core of the «planet» and inside the «Universe», etc.

At the same time, while studying the layered structure of a rakia of one spherical formation, we simultaneously partially comprehend the properties of rakia and all other spherical objects from the hierarchical sequence (76), because they are similar.