Submitted:

29 January 2023

Posted:

30 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Doping Precursors Preparation and SDS-PAGE Profiling of Mytilus edulis Extrapallial Fluid

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of the C-N-TiO2 Semiconductors

2.3. MPs and NPs Obtainment and Characterization

2.4. Photocatalytic Experiments

2.4.1. Photocatalysis of Primary PS NPs and MPs

2.4.2. Photocatalysis of Primary PE MPs

3. Results and Discussion

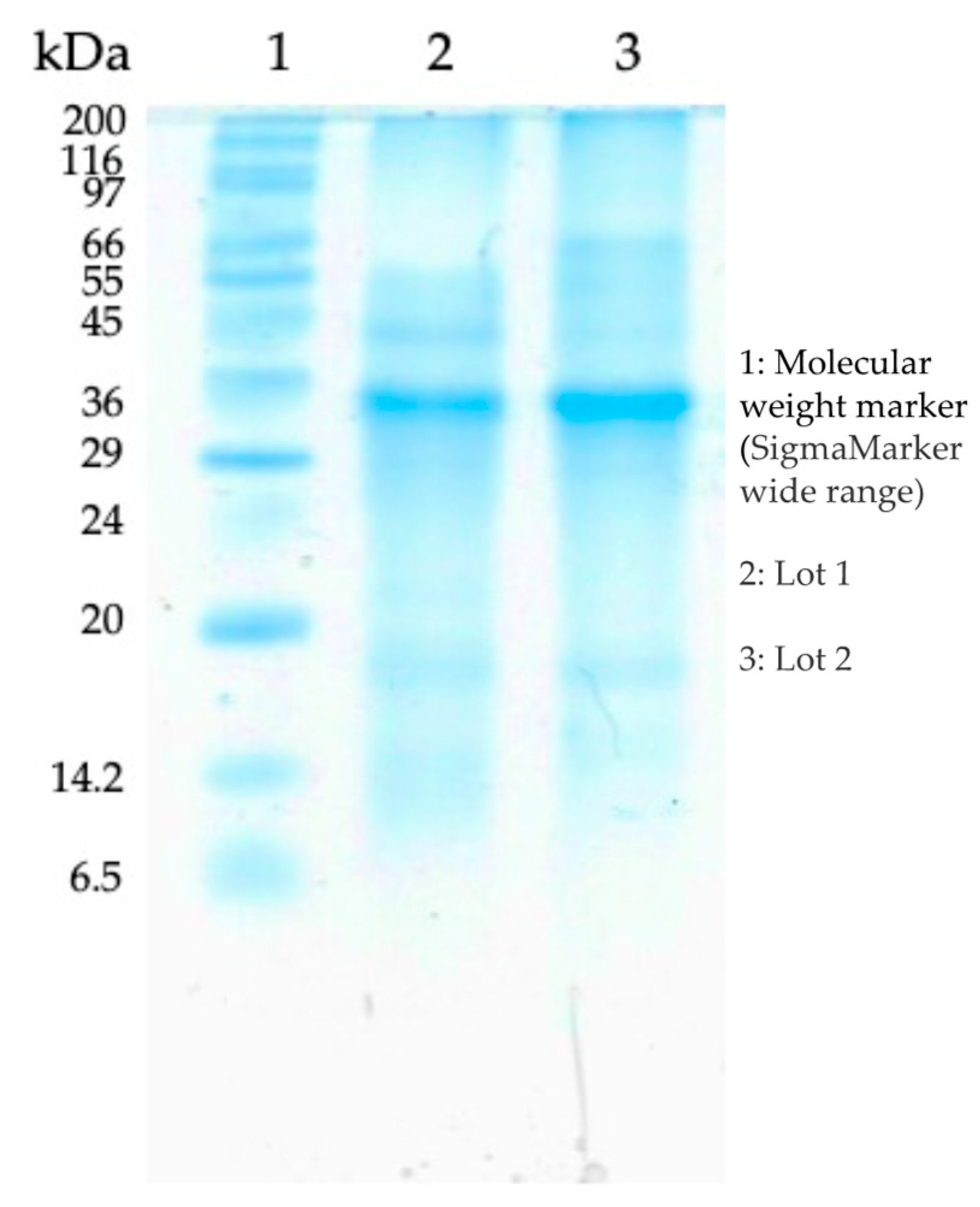

3.1. Protein Quantification of M. edulis EPF

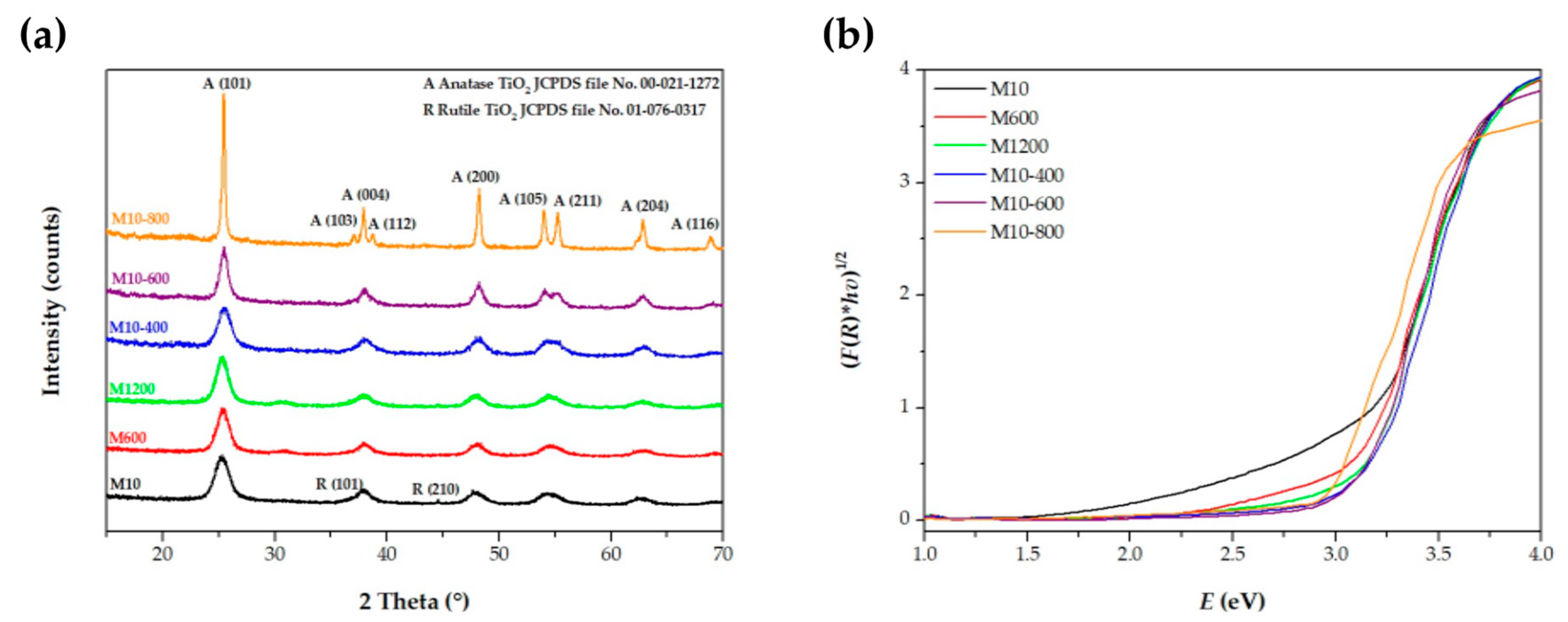

3.2. Semiconductors Characterization

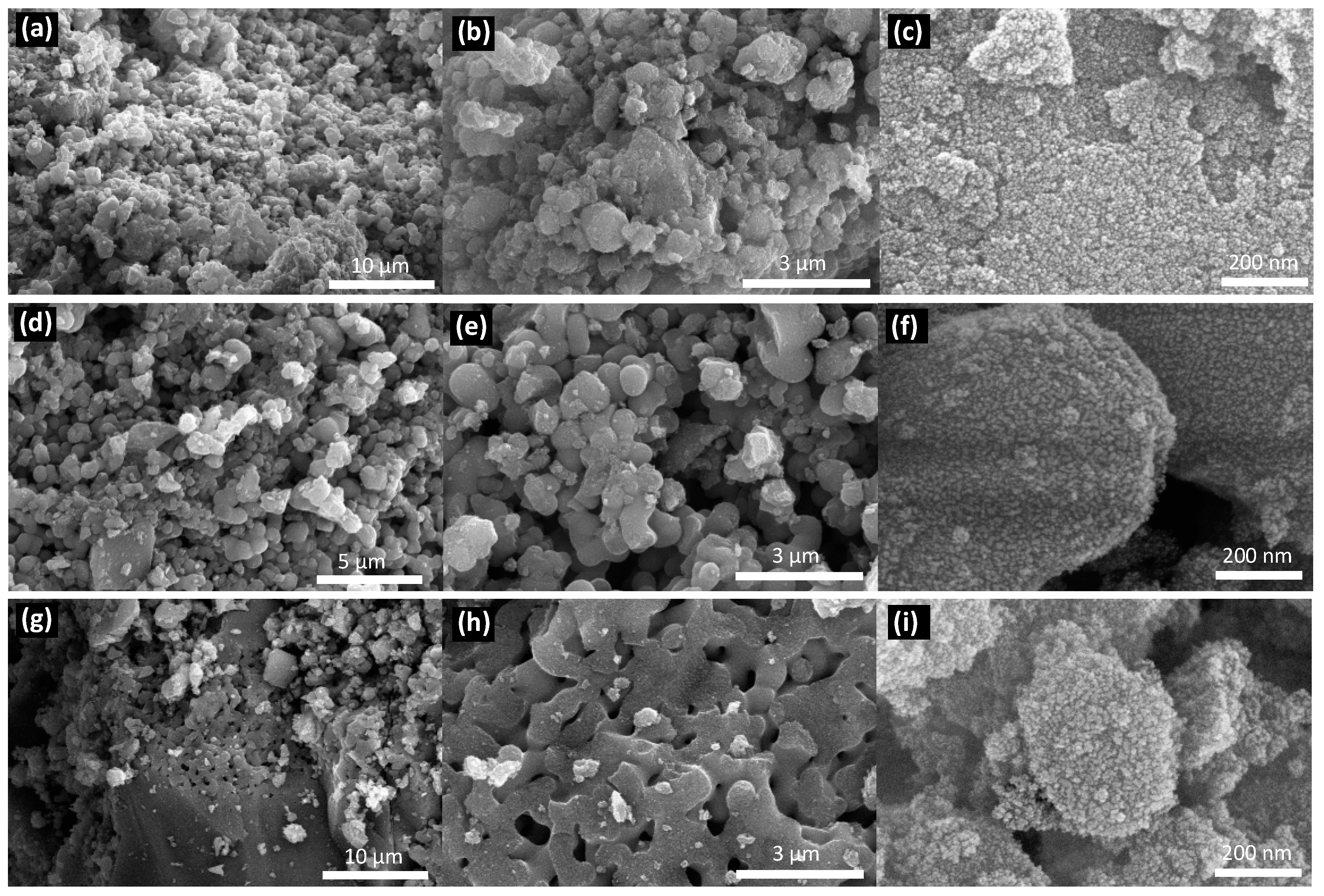

3.3. PS NPs and MPs Characterization

3.4. Photocatalysis of Primary PS NPs and MPs Using C,N-TiO2 Films

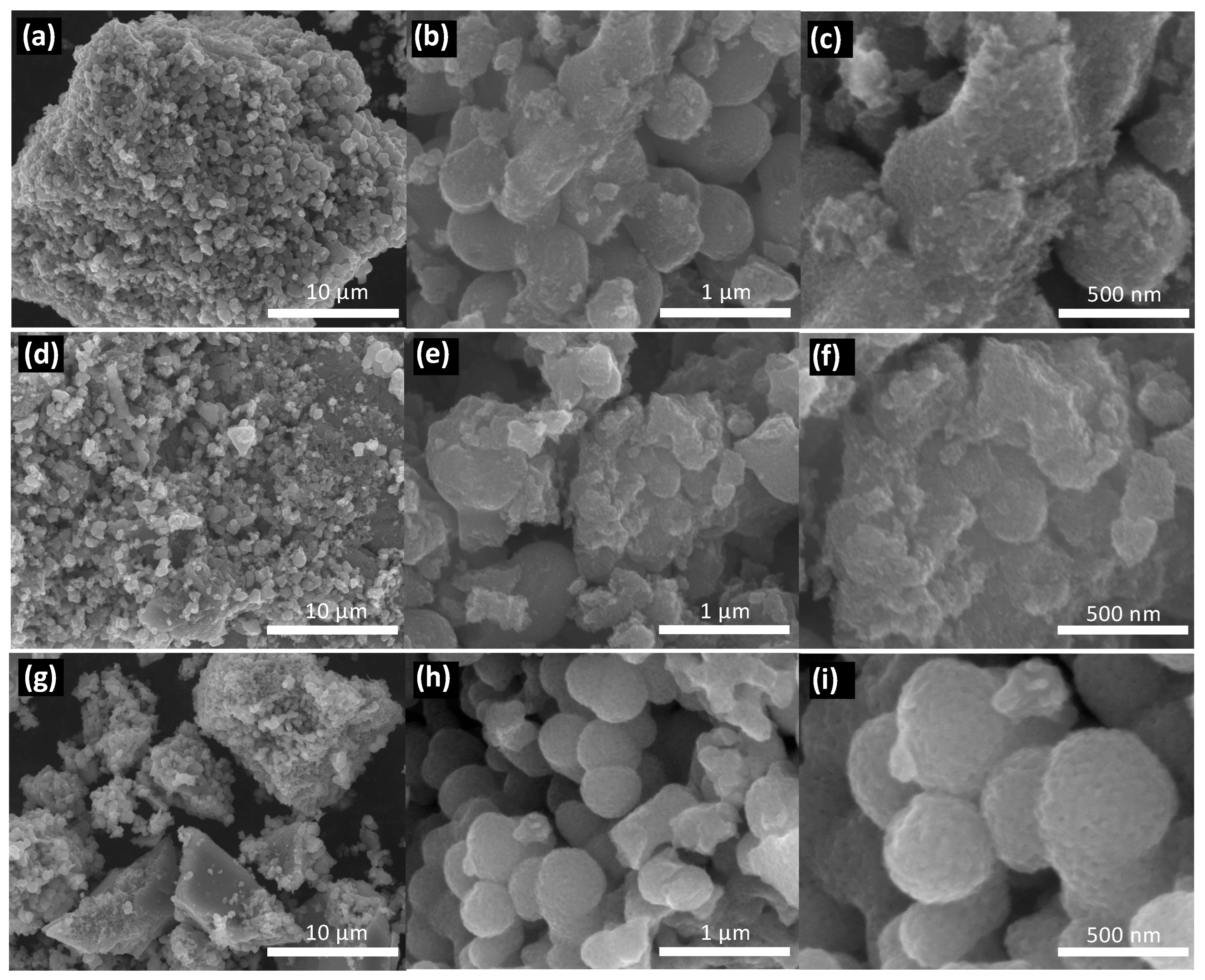

3.5. PE MPs Characterization

3.6. Photocatalysis of Primary PE MPs Using C,N-TiO2 Powders

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Plastic Pollution. Our World in Data 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gall, S.C.; Thompson, R.C. The Impact of Debris on Marine Life. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2015, 92, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, K.L. Plastics in the Marine Environment. Annual Review of Marine Science 2017, 9, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee for Risk Assessment (RAC); Committee for Socio-economic Analysis (SEAC) Background Document to the Opinion on the Annex XV Report Proposing Restrictions on Intentionally Added Microplastics; European Chemicals Agency (ECHA): Helsinki, Finland, 2000.

- Pizzurro, F.; Recchi, S.; Nerone, E.; Salini, R.; Barile, N.B. Accumulation Evaluation of Potential Microplastic Particles in Mytilus Galloprovincialis from the Goro Sacca (Adriatic Sea, Italy). Microplastics 2022, 1, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; Silva, A.L.P.; da Costa, J.P.; Dias-Pereira, P.; Carvalho, A.; Fernandes, A.J.S.; da Costa, F.M.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Microplastics in Internal Tissues of Companion Animals from Urban Environments. Animals 2022, 12, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Shi, H.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Jabeen, K.; Kolandhasamy, P. Microplastic Pollution in Table Salts from China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 13622–13627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schymanski, D.; Goldbeck, C.; Humpf, H.-U.; Fürst, P. Analysis of Microplastics in Water by Micro-Raman Spectroscopy: Release of Plastic Particles from Different Packaging into Mineral Water. Water Research 2018, 129, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutralam-Muniasamy, G.; Pérez-Guevara, F.; Elizalde-Martínez, I.; Shruti, V.C. Branded Milks – Are They Immune from Microplastics Contamination? Science of The Total Environment 2020, 714, 136823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M.; Tahir, A.; Williams, S.L.; Baxa, D.V.; Lam, R.; Miller, J.T.; Teh, F.-C.; Werorilangi, S.; Teh, S.J. Anthropogenic Debris in Seafood: Plastic Debris and Fibers from Textiles in Fish and Bivalves Sold for Human Consumption. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 14340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, H.A.; van Velzen, M.J.M.; Brandsma, S.H.; Vethaak, A.D.; Garcia-Vallejo, J.J.; Lamoree, M.H. Discovery and Quantification of Plastic Particle Pollution in Human Blood. Environment International 2022, 163, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, A.; Svelato, A.; Santacroce, C.; Catalano, P.; Notarstefano, V.; Carnevali, O.; Papa, F.; Rongioletti, M.C.A.; Baiocco, F.; Draghi, S.; et al. Plasticenta: First Evidence of Microplastics in Human Placenta. Environment International 2021, 146, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabl, P.; Köppel, S.; Königshofer, P.; Bucsics, T.; Trauner, M.; Reiberger, T.; Liebmann, B. Detection of Various Microplastics in Human Stool: A Prospective Case Series. Annals of Internal Medicine 2019, 171, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, J.P.; Duarte, A.C.; Santos-Echeandía, J.; Rocha-Santos, T. Significance of Interactions between Microplastics and POPs in the Marine Environment: A Critical Overview. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2019, 111, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barus, B.S.; Chen, K.; Cai, M.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Cheng, S.-Y. Heavy Metal Adsorption and Release on Polystyrene Particles at Various Salinities. Frontiers in Marine Science 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Yang, J. Microplastic Serves as a Potential Vector for Cr in an In-Vitro Human Digestive Model. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 703, 134805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Vázquez, J.; Rodil, R.; Trujillo-Rodríguez, M.J.; Quintana, J.B.; Cela, R.; Miró, M. Mimicking Human Ingestion of Microplastics: Oral Bioaccessibility Tests of Bisphenol A and Phthalate Esters under Fed and Fasted States. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 826, 154027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamidian, A.H.; Ozumchelouei, E.J.; Feizi, F.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M. A Review on the Characteristics of Microplastics in Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Source for Toxic Chemicals. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 295, 126480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Hamid, A.K.; Krebsbach, S.A.; He, J.; Wang, D. Critical Review of Microplastics Removal from the Environment. Chemosphere 2022, 293, 133557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricardo, I.A.; Alberto, E.A.; Silva Júnior, A.H.; Macuvele, D.L.P.; Padoin, N.; Soares, C.; Gracher Riella, H.; Starling, M.C.V.M.; Trovó, A.G. A Critical Review on Microplastics, Interaction with Organic and Inorganic Pollutants, Impacts and Effectiveness of Advanced Oxidation Processes Applied for Their Removal from Aqueous Matrices. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 424, 130282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Yan, D.; Fu, J.; Chen, Y.; Ou, H. Ultraviolet-C and Vacuum Ultraviolet Inducing Surface Degradation of Microplastics. Water Research 2020, 186, 116360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, R.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, C.G. Surface Modification of Polyethylene Microplastic Particles during the Aqueous-Phase Ozonation Process. Environmental Engineering Research 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Liu, Y.; Gao, M.; Yu, X.; Xiao, P.; Wang, M.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. Degradation of Polyvinyl Chloride Microplastics via an Electro-Fenton-like System with a TiO2/Graphite Cathode. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 399, 123023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Zhou, L.; Duan, X.; Sun, H.; Ao, Z.; Wang, S. Degradation of Cosmetic Microplastics via Functionalized Carbon Nanosprings. Matter 2019, 1, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña-Bedoya, J.D.; Luévano-Hipólito, E.; Cedillo-González, E.I.; Domínguez-Jaimes, L.P.; Hurtado, A.M.; Hernández-López, J.M. Boosting Visible-Light Photocatalytic Degradation of Polystyrene Nanoplastics with Immobilized CuxO Obtained by Anodization. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9, 106208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofa, T.S.; Kunjali, K.L.; Paul, S.; Dutta, J. Visible Light Photocatalytic Degradation of Microplastic Residues with Zinc Oxide Nanorods. Environ Chem Lett 2019, 17, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofa, T.S.; Ye, F.; Kunjali, K.L.; Dutta, J. Enhanced Visible Light Photodegradation of Microplastic Fragments with Plasmonic Platinum/Zinc Oxide Nanorod Photocatalysts. Catalysts 2019, 9, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Lu, G.; Yan, Z.; Liu, J.; Wu, D.; Wang, Y. Microplastic Degradation by Hydroxy-Rich Bismuth Oxychloride. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 405, 124247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Wan, S.; Wang, Y.; Guo, H.; Ou, M.; Zhong, Q. Highly-Efficient Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic H2 Evolution Integrated with Microplastic Degradation over MXene/ZnxCd1-XS Photocatalyst. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2022, 605, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, M.F.; Didit, A.M.; Ibadurrohman, M.; Setiadi, S.; Slamet, S. Doped TiO2 Photocatalyst for Disinfection of E. Coli and Microplastic Pollutant Degradation in Water. Asian Journal of Chemistry 2021, 33, 2038–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kwon, H.; Song, R.; Shin, S.; Ham, S.-Y.; Park, H.-D.; Lee, J.; Fischer, P.; Bodenschatz, E. Hierarchical Optofluidic Microreactor for Water Purification Using an Array of TiO2 Nanostructures. npj Clean Water 2022, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Luo, Y.; Song, S.; Dong, X.; Yu, X. High Photocatalytic Degradation Activity of Polyethylene Containing Polyacrylamide Grafted TiO2. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2013, 98, 1754–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadli, M.H.; Ibadurrohman, M.; Slamet, S. Microplastic Pollutant Degradation in Water Using Modified TiO2 Photocatalyst Under UV-Irradiation. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1011, 012055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Tarazona, M.C.; Villarreal-Chiu, J.F.; Hernández-López, J.M.; Rivera De la Rosa, J.; Barbieri, V.; Siligardi, C.; Cedillo-González, E.I. Microplastic Pollution Reduction by a Carbon and Nitrogen-Doped TiO2: Effect of PH and Temperature in the Photocatalytic Degradation Process. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 395, 122632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorente-García, B.E.; Hernández-López, J.M.; Zaldívar-Cadena, A.A.; Siligardi, C.; Cedillo-González, E.I. First Insights into Photocatalytic Degradation of HDPE and LDPE Microplastics by a Mesoporous N–TiO2 Coating: Effect of Size and Shape of Microplastics. Coatings 2020, 10, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, L.; Zhang, F.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, J. Feasible Degradation of Polyethylene Terephthalate Fiber-Based Microplastics in Alkaline Media with Bi2O3@N-TiO2 Z-Scheme Photocatalytic System. Advanced Sustainable Systems 2022, 6, 2100516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuwendi, Y.; Ibadurrohman, M.; Setiadi, S.; Slamet, S. Photocatalytic Degradation of Polyethylene Microplastics and Disinfection of E. Coli in Water over Fe- and Ag-Modified TiO2 Nanotubes. Bulletin of Chemical Reaction Engineering & Catalysis 2022, 17, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Luo, H.; Zhang, F.; Wu, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, H. Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of the Persistent PET Fiber-Based Microplastics over Pt Nanoparticles Decorated N-Doped TiO2 Nanoflowers. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2022, 4, 1094–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Xie, J.; Xie, H.; Su, B.-L.; Wang, M.; Ping, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Fu, Z. Bioprocess-Inspired Synthesis of Hierarchically Porous Nitrogen-Doped TiO2 with High Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 19588–19596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Analytical Biochemistry 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telford, A.M.; Pham, B.T.T.; Neto, C.; Hawkett, B.S. Micron-Sized Polystyrene Particles by Surfactant-Free Emulsion Polymerization in Air: Synthesis and Mechanism. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry 2013, 51, 3997–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napper, I.E.; Bakir, A.; Rowland, S.J.; Thompson, R.C. Characterisation, Quantity and Sorptive Properties of Microplastics Extracted from Cosmetics. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2015, 99, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Jaimes, L.P.; Cedillo-González, E.I.; Luévano-Hipólito, E.; Acuña-Bedoya, J.D.; Hernández-López, J.M. Degradation of Primary Nanoplastics by Photocatalysis Using Different Anodized TiO2 Structures. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 413, 125452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamas, A.; Moon, H.; Zheng, J.; Qiu, Y.; Tabassum, T.; Jang, J.H.; Abu-Omar, M.; Scott, S.L.; Suh, S. Degradation Rates of Plastics in the Environment. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 3494–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, P.; Liu, J.; Yu, J. New Understanding of the Difference of Photocatalytic Activity among Anatase, Rutile and Brookite TiO2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 20382–20386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Liu, W.; Cai, J.; Chen, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H.; Qi, L. Nanoporous Anatase TiO2 Mesocrystals: Additive-Free Synthesis, Remarkable Crystalline-Phase Stability, and Improved Lithium Insertion Behavior. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishima, A.; Zhang, X.; Tryk, D.A. TiO2 Photocatalysis and Related Surface Phenomena. Surface Science Reports 2008, 63, 515–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.M.; Márquez, G.; Tena, M.; Álvarez, P.M.; Beltrán, F.J. Determination of Main Species Involved in the First Steps of TiO2 Photocatalytic Degradation of Organics with the Use of Scavengers: The Case of Ofloxacin. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2015, 178, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kik, K.; Bukowska, B.; Sicińska, P. Polystyrene Nanoparticles: Sources, Occurrence in the Environment, Distribution in Tissues, Accumulation and Toxicity to Various Organisms. Environmental Pollution 2020, 262, 114297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vital-Grappin, A.D.; Ariza-Tarazona, M.C.; Luna-Hernández, V.M.; Villarreal-Chiu, J.F.; Hernández-López, J.M.; Siligardi, C.; Cedillo-González, E.I. The Role of the Reactive Species Involved in the Photocatalytic Degradation of HDPE Microplastics Using C,N-TiO2 Powders. Polymers 2021, 13, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socrates, G. Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies: Tables and Charts; 3rd.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-470-09307-8. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.H.; Lee, C.M.; Choi, J.W.; Park, G.C.; Joo, J. Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of Porous Single Crystal TiO2/CNT Composites by Annealing Process. Ceramics International 2018, 44, 1641–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Semiconductor | Eg (eV) | Wavelength of Light Absorption (nm) | Carbon (wt.%) | Nitrogen (wt.%) |

SBET (m2/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M10 | 2.93 | 423 | 1.37 | 0.41 | 223.2 |

| M1600 | 2.87 | 432 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 171.15 |

| M1200 | 2.95 | 421 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 192.8 |

| M10-400 | 2.88 | 431 | 4.44 | 0.42 | 166.48 |

| M10-600 | 3.02 | 411 | 4.58 | 0.32 | 76.73 |

| M10-800 | 2.99 | 415 | 10.37 | 0.34 | 6.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).