Introduction

Since the end of the Second World War, the federal government of the United States of America (U.S.) has implemented significant public policy regarding university technology transfer to the private sector and technology transfer in general (see Townes, 2022). A significant body of scholarly research on the topic has been developed and continues to be developed, which informs public policy formulation (see Bengoa, Maseda, Iturralde, & Aparicio, 2020; Kirchberger & Pohl, 2016; Noh & Lee, 2019). However, there is a danger that progress in the field will increasingly diminish without sufficient advancements that encourage and facilitate new analytical approaches.

Policy analysts cannot effectively identify, evaluate, and recommend solutions for policy problems, such as those related to university technology transfer, without first usefully formulating the problems (Dunn, 2016). Policy problems “have no existence apart from the individuals and groups who define them” (Dunn, p. 70); thus, there are no innate arrangements of social conditions that inherently constitute policy problems (Dunn). In the case of university technology transfer, such problem formulation includes consideration of various possible conceptualisations of the construct of technology.

Conceptualising and defining constructs are forms of framing. How one frames an issue greatly influences the types of questions that both researchers and policymakers ask and the nature of the solutions that policymakers develop. Consequently, how researchers and policymakers conceptualize technology in the context of university technology transfer significantly affects the nature of the research and public policy they pursue.

The aim of this paper is to make a new conceptual contribution to the knowledge base about university technology transfer. Generally, conceptual articles make theoretical advances without relying on data (M. S. Yadav, 2010). However, this paper takes a more empirical approach. It focuses on answering three primary questions. First, how is technology generally conceptualised in scholarly research and public policy regarding university technology transfer in the United States of America? Second, what are the shortcomings of these conceptualisations of technology as they relate to scholarly research and federal public policy regarding university technology transfer? Finally, what is an alternative conceptualisation of technology that potentially mitigates any disadvantages of the current conceptualisations?

This conceptual analysis integrates constructs and ideas in the related literature to provide a new perspective of technology that can advance future scholarly research and public policy formulation about university technology transfer specifically, and technology transfer in general. Additionally, the methods and methodology employed demonstrate a new approach to theoretical and conceptual research in the social sciences. Although the focus of the paper is university technology transfer to the private sector in the United States, the insights it presents are likely relevant to technology transfer more broadly and applicable in other geopolitical contexts.

Literature Review

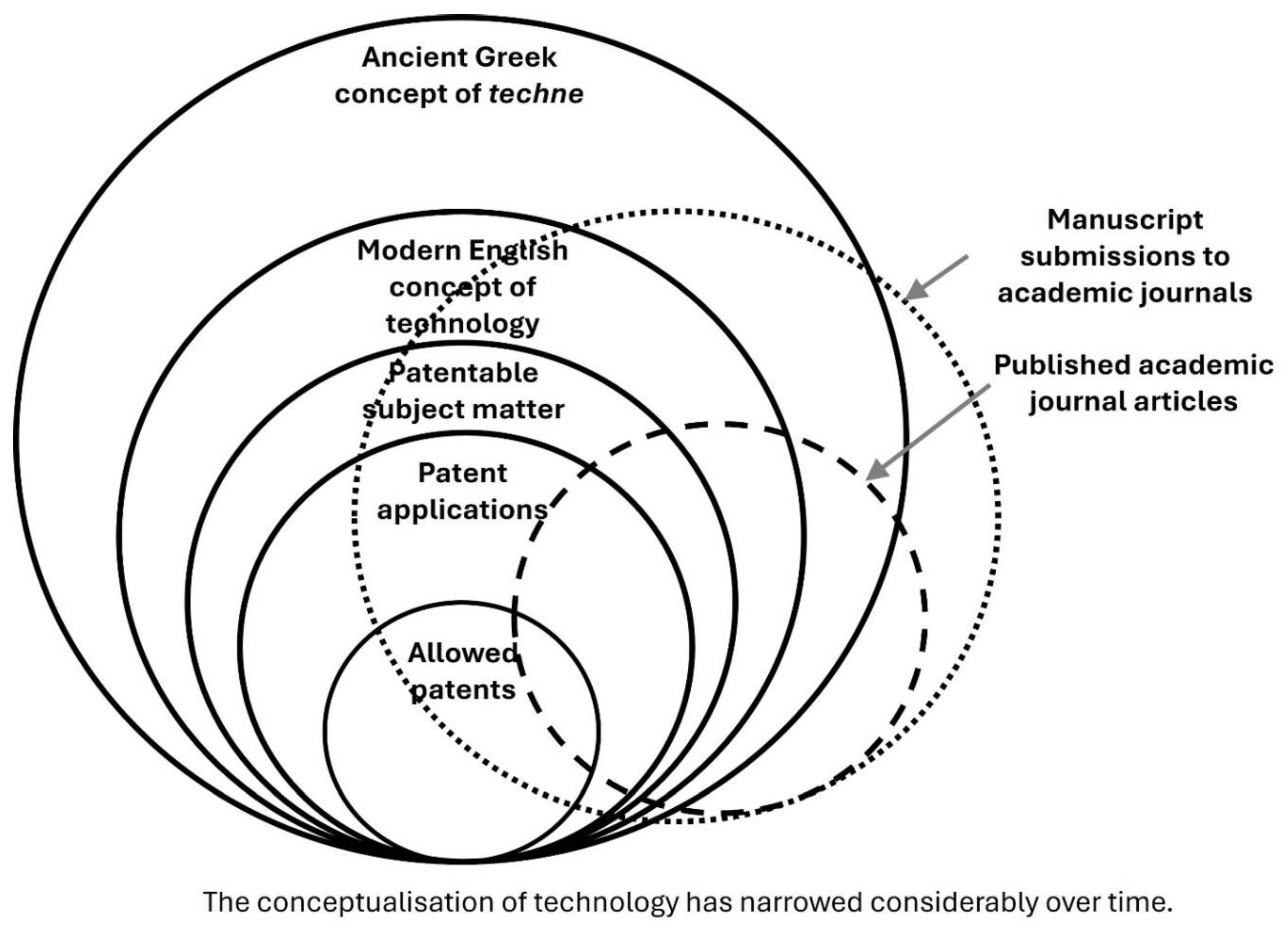

There is no universally accepted definition of technology, either culturally or in the context of U.S. public policy (see Schatzberg, 2018). In fact, there is significant debate among scholars about the definition of the term. Moreover, the literature reveals that the concept of technology has steadily narrowed over time. In fact, when people in the U.S. currently use the term, they typically are referring to instrumental artifacts and patentable inventions.

A Muddled Construct

As a construct, it seems that the term technology is “a bastard child of uncertain parentage” (Schatzberg, 2018, p. 14). Throughout the course of history, the concept of technology has progressively narrowed from the meaning of the original Ancient Greek term techne, which is its oldest known cognate. As Schatzberg explained, techne referred to the science (i.e., principles and processes) of the useful arts (i.e., branch of learning or human activity). The German concept of technik, which was derived from the Ancient Greek concept of techne, also had a broad meaning in its original use (Schatzberg). The German concept was broader than the modern conception of technology in English speaking Western society. Moreover, Technik was distinct from the German term technologie, both of which were associated with craft production (Schatzberg). It seems that the latter was a subset of the former. Technik could take on a broad meaning referring to the rules, procedures, and skills for achieving an objective (i.e., art in the most general sense) or a narrower meaning referring to the physical aspects of commercial enterprise (Schatzberg).

Technik eventually shaped the modern concept of technology in the English language through an unfortunate mistranslation (Schatzberg, 2018). English language scholars mistranslated technik, whose meaning in the German language varied depending on context, and this mistranslation has contributed significantly to the current confusion in the meaning of technology in the English language (Mitcham & Schatzberg, 2009; Schatzberg). It is this confusion that helps drive the current debate among English-speaking scholars about the definition of technology.

Debates surrounding ontological issues about technology and its relation to and influence on society eventually led to the establishment of philosophy of technology as a field of study, marked by the establishment of the Society for the Philosophy of Technology in 1976 (Dusek, 2006). What is technology is a fundamental question of the field. Characterisations of technology generally fall into one of three categories – tools, rules, or systems (Dusek). The modern conceptualisation of technology has both an instrumental and anthropological perspective, one being means to achieve ends and the other being a human activity (Heidegger, 2009).

Currently there are two primary schools of thought among English-speaking scholars regarding the definition of technology (Mitcham & Schatzberg, 2009; Schatzberg, 2018). The instrumental school is the dominant view and conceptualizes technology as tools or implements that serve practical purposes (Schatzberg). This appears to be how technology is generally conceptualised in the United States. Proponents of the idea that technology determines culture (i.e., technological determinism) generally espouse this view (Schatzberg). Alternatively, the cultural school views technology as the “creative expression of human culture” (Schatzberg, p. 3). This view emphasises the anthropological perspective. Scholars in this camp point to the influence that human agency and culture have in shaping the form of technology over time (Schatzberg). Culture shapes technology as much as technology influences culture. Both these viewpoints seem to touch on fundamental truths about the nature of technology but neither serves as an adequate definition of technology in and of itself (Schatzberg). However, these viewpoints are not mutually exclusive. Rather, they are essentially two sides of the same coin.

In the early 1960s a definition of technology emerged in the English language that, although stable over the past several decades, is fairly muddled because it comprises three primary meanings (Schatzberg, 2018). These include (1) the application of science (i.e., applied science), (2) an autonomous body of knowledge, practices, and artifacts (i.e., industrial arts), and (3) technique or instrumental reason (Schatzberg). According to Schatzberg, these meanings are incompatible with one another. One might also argue that these definitions are also somewhat arbitrary categorizations derived from the social machinations of various individuals who sought to manipulate the definition of technology to protect or increase the prestige and political clout of their respective disciplines.

Feibleman (1961) exemplifies the quandary of conceptualising technology. Feibleman attempted to distinguish between pure science, applied science, technology, and engineering. This approach essentially placed these constructs on a continuum with each one building on the previous one. Feibleman argued that pure science was systematic theoretical and experimental efforts to describe nature and discover laws with no concern for potential application while applied science was the application of pure science for improving human means and ends. He defined technology as improvements of instruments used to extend applied science, which conforms to the instrumental conceptualisation of technology. Fiebleman argued that engineering was technology applied to specific situations. He did note, however, that scientific pursuits are not entirely pure science or entirely applied science. Moreover, he maintained that both applied science and technology often reveal previously unknown scientific principles and natural laws.

Conceptualisation in Technology Transfer Research and Public Policy

A review of the literature did not unearth any works that directly addressed the conceptualisation of technology in the context of research and public policy regarding university technology transfer in the United States of America (U.S). However, there was literature that explored the topic in other contexts. Wahab, Rose, and Osman (2012) examined how the concepts and definitions of technology and technology transfer developed across a broad spectrum of disciplines. Based on their analysis of the literature, they concluded that the conceptualisation and definition of technology and technology transfer varied based on organization objectives, research background, discipline, and underlying theory. They concluded that the different perspectives drive different research problems, variables, measurements, and insights.

Other scholars have explored the conceptualisation of technology in the context of international technology transfer (Reddy & Zhao, 1990). Defining the concept of technology surfaces as a difficulty. Various approaches have been used to overcome this challenge, such as the application of various taxonomies (see e.g., Chudson, 1971; Division of Science Resources Studies, 1973; Madeuf, 1984; Mansfield, 1975; Robock & Calkins, 1980). The use of different taxonomies has led to different insights.

Smirnova (2014) indirectly investigated the conceptualisation of technology in a comparison of knowledge transfer and technology transfer in the public policy of Kazakstan. This examination identified various dichotomous taxonomies for knowledge that might be applicable to technology. Smirnova concluded that knowledge transfer embodied technology transfer, but technology transfer does not necessarily embody knowledge transfer; however, effective technology transfer is not possible without knowledge transfer. This raises the notion that technology is a subset of knowledge.

Parayil (2002) touched on the conceptualisation of technology in an examination of technological change in a social-historical context. Parayil proposed that technological change is a reflexive social-historical problem-solving process contingent on the change in knowledge of relevant human agents. As such, Parayil concluded that technology transfer is best explained by studying the exchange of knowledge (i.e., ideas and information) between human agents rather than tangible material artifacts. This implies that technology, at its core, is simply ideas and information. Other scholars have also analysed the conceptualisation of technology in social or historical contexts (see e.g., Andersson, Dasí, Mudambi, & Pedersen, 2016; Aydin, González Woge, & Verbeek, 2019; Rafael, 2013).

Scholars have discussed the conceptualisation of technology in the context of research in a variety of other disciplines such as development communication, information systems, industrial innovation, technology management, trade, and marketing (see e.g., Avila-Robinson & Miyazaki, 2011; Bugbilla, Anyigba, & Korletey, 2019; Faulkner, 1994; Houston & Jackson, 2009; Sawyer & Chen, 2003; N. Yadav, Swami, & Pal, 2006). However, no literature was found that explicitly focused on the effects of the conceptualisation of technology on research and public policy regarding university technology transfer in the United States. Consequently, the examination presented in this paper aims to fill this void in the knowledge base about university technology transfer.

Methodology

The previous two sections identified the knowledge gap that the analysis described in this paper seeks to address and established the conceptual and theoretical framework for the examination. This section details the approach taken to investigate the conceptualisations of technology in scholarly research and public policy regarding university technology transfer in the United States of America, how they affect research and public policy, and what alternative conceptualisation might mitigate concerns and challenges with the current conceptualisations. It explains what data were collected and generated, how the data were analysed, and the rationale for choosing the specific methods employed in the analysis.

Understanding the Current Conceptualisations of Technology

Scholarship in fields relevant to university technology transfer have indicated a need for expanding the scope of methods and methodologies used to study the topic. Of particular note are recommendations to apply more inductive approaches and to increase the use of non-quantitative data (Leo Paul Dana & Dana, 2005). Particularly relevant to the current study is the notion that “fundamental intellectual work, in research, involves the job of re-defining concepts, whether these be newly derived or existing” (Léo-Paul Dana & Dumez, 2015). In an effort to expand the boundaries of current approaches knowledge creation, this study applied methods and methodologies from various fields including thematic analysis, failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA), and lateral thinking techniques.

The study employed thematic analysis to understand how scholars and policymakers currently conceptualise technology in the context of U.S. university technology transfer. This is a family of creative techniques within the category of qualitative social sciences research methods that formalize and structure the process of identifying or developing unifying motifs and patterns of meaning from non-ordinal data (Clarke & Braun, 2017; Fugard, 2020; Guest, MacQueen, & Namey, 2012). The specifics of a particular thematic analysis technique depends on the research question, nature of the textual data, and analysis frame of reference (Fugard). Thematic analysis is rooted in both positivist and interpretive epistemology (Guest et al.). As a method, thematic analysis is particularly useful for this study because of its flexibility with regard to theory, research question, sample size, data form, datum length, data collection methods, and data synthesis techniques (see Clarke & Braun; Guest et al.).

The data used for the analysis consisted of the text of samples from the academic literature on the topic and the text of public laws passed since 1980 that are relevant to university technology transfer in the United States of America. The literature relevant to U.S. university technology transfer is vast, fragmented, and dispersed which makes it difficult to establish a suitable sample frame for probabilistic sampling methods. Given this circumstance and the fact that the analysis was somewhat exploratory, non-probabilistic sampling methods were employed. The textual data used in the analysis were gathered using a combination of purposive sampling (also referred to as judgmental sampling) and convenience sampling.

Manual text segmentation was done to facilitate examination of thematic elements. This consisted of key-word-in-context (KWIC) segmentation which “identifies a word as the locus for a theme or concept in a body of text without predefining the textual boundaries of that locus” (Guest et al., 2012, Chapter 3). In this case, the concept of interest was the conceptualisation of technology, whether explicitly stated or implied.

A codebook was developed during the analysis. This discrete analysis step consisted of systematically sorting the meaning in the textual data into categories, types, and relationships of meaning through an iterative process. Textual data were reviewed in batches, and the codebook was modified as new information and insights were gleaned. The textual data were coded for content to indicate the definitional meaning of technology as applied in the text. This process served to bring focus to the fuzziness of the textual data and maximize the coherence of the codes of the codebook (see Guest et al., 2012).

To refine the themes regarding the conceptualisation of technology, the textual data were re-read with an eye toward the analytical objective of the analysis. This included noting thematic or linguistic cues such as repetition, atypical application of terms, metaphors and analogies, shifts in topical content, similarities and differences between sections of text, linguistic connectors, and expected themes that are absent (see Guest et al., 2012). The identified themes were winnowed to separate the noteworthy (the wheat) from what was notable (the chaff). Additionally, measures were taken to avoid conflating what was said in a text with an interpretation of what was said, which can occur in qualitative analysis as text data and rounds of coding are layered. This was done using an iterative process consisting of (1) reading the text, (2) proposing themes, (3) refining the themes into well-defined codes, (4) coding text data a second after a time lag between the initial coding, and (5) comparing the coded text data. If the results differed, the reason why was determined, the codes and code definitions were adjusted, and the textual data were recoded as necessary.

Examining the Effects on Research and Public Policy

Elements of failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) were modified and applied to examine the effects that scholars’ and policymakers’ current conceptualisations of technology have on university technology transfer research and public policy. FMEA is a method that engineers use to assess and manage risk for products and systems. It is essentially a way of structuring analysis and creative problem-solving activities. FMEA is often modified and applied in different contexts (see e.g., Bradley & Guerrero, 2011; Kara-Zaitri, Keller, Barody, & Fleming, 1991; Sharma & Srivastava, 2018; Vahdani, Salimi, & Charkhchian, 2015).

The terms risk and uncertainty are often used interchangeably but they mean very different things (Knight, 1921). At the conceptual level, a risk is the chance that some action or decision will result in an undesired outcome (i.e., effect) for which one can either specify or estimate the probability of the undesired outcome occurring. Uncertainty is the possibility that some action or decision will result in an outcome for which one cannot specify or reasonably estimate the probability of the outcome occurring. In the context of this analysis, the effects (both desirable and undesirable) on university technology transfer research and public policy result, at least in part, from a common act that both scholars and policymakers make, which is deciding (whether explicitly or implicitly) what conceptualisation of technology they will apply. In this examination, the effects of a technology conceptualisation are an uncertainty.

The purpose of FMEA as applied in engineering is to (1) determine what can go wrong, (2) specify the expected consequences for each of those things that can go wrong, and (3) prioritize the items on which to focus mitigation efforts (Stamatis, 2019). As applied in this analysis, elements of FMEA were used to (1) posit the consequences of the various conceptualisations of technology on research and public policy regarding university technology transfer, and (2) prioritize conceptualisations on which to focus integration.

While these questions are analogous to those addressed by FMEA in engineering contexts, the focus is not strictly on negative outcomes as the term “failure mode” conveys. A failure mode is simply a way in which a component of a system can either function improperly or not function at all thereby adversely impacting the performance of the system. However, the conceptualisation of technology can impact research and public policy in both favourable and unfavourable ways.

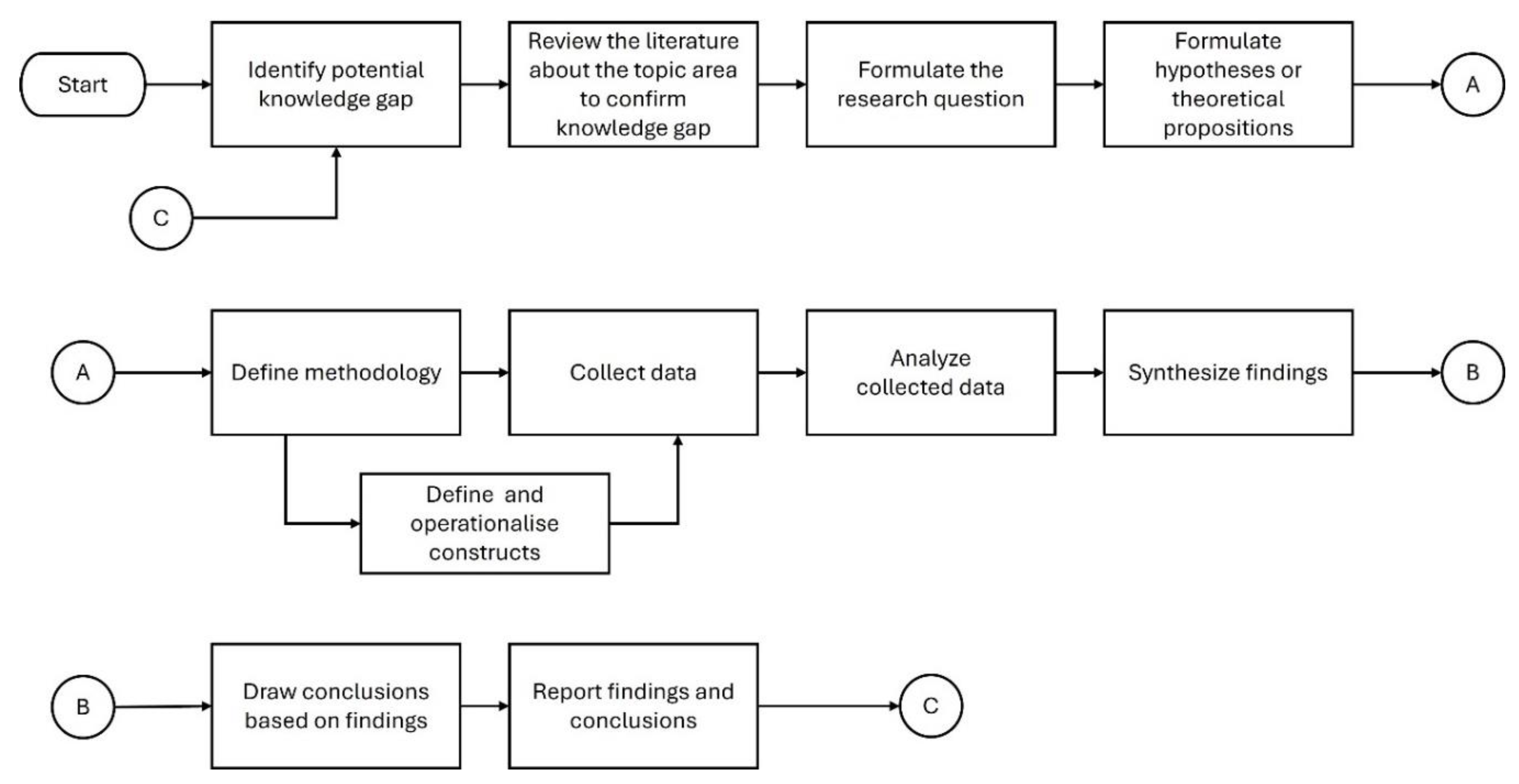

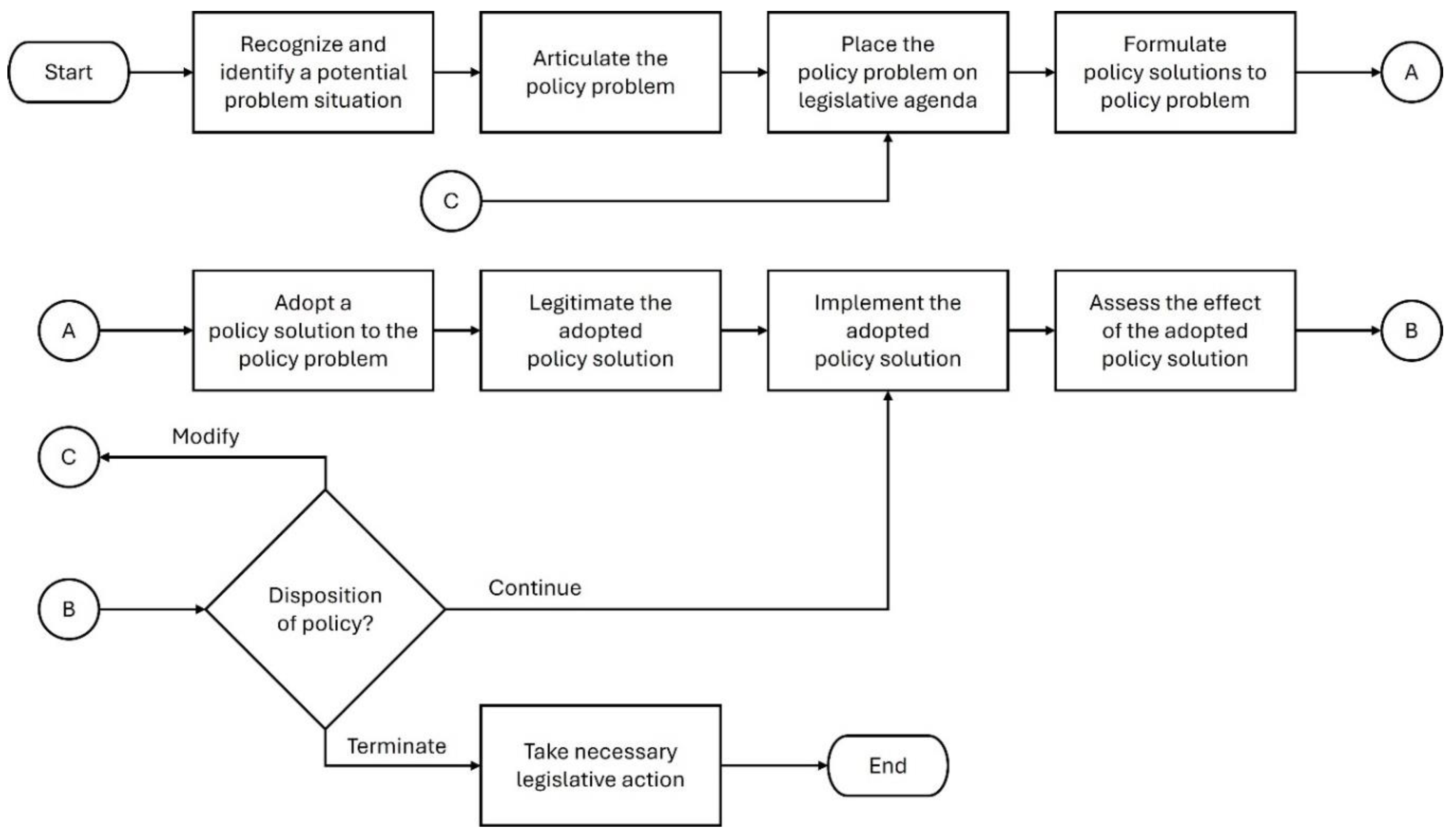

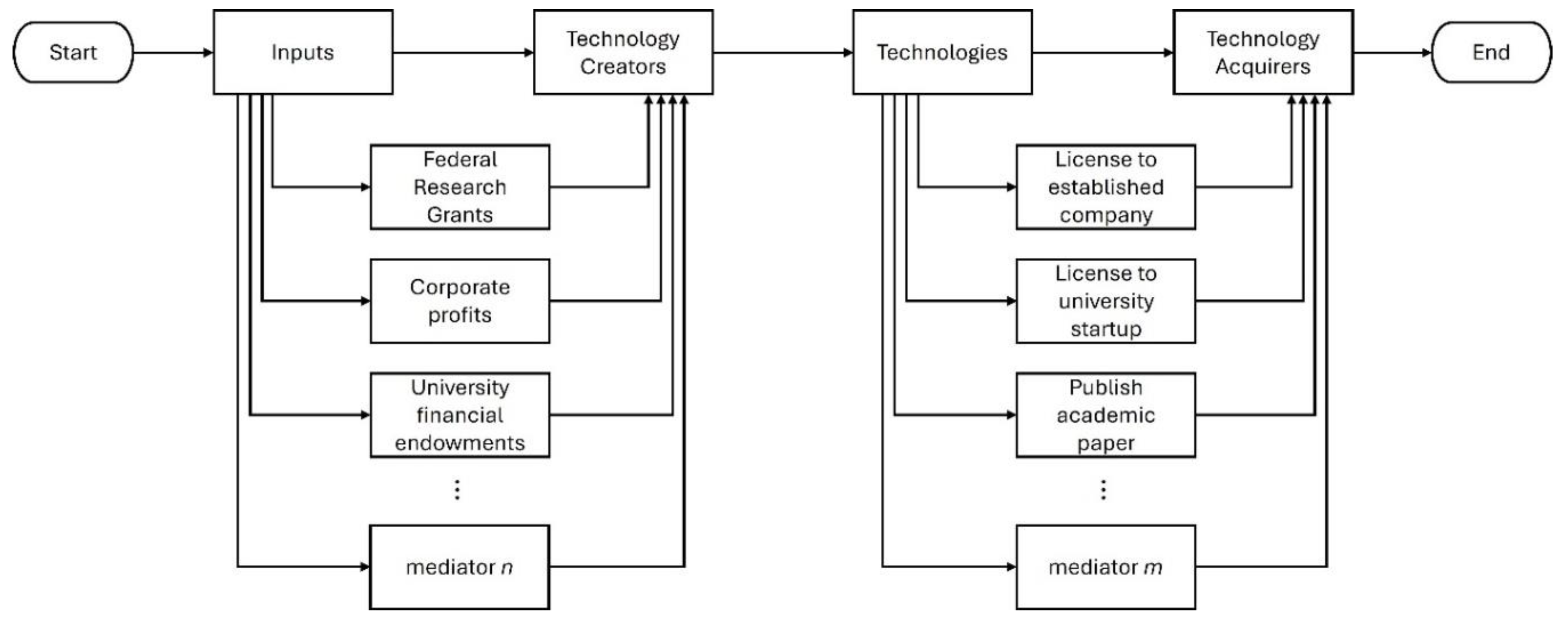

The process employed for this study consisted of four basic steps. The first step in FMEA is assembling a team to perform the analysis. As originally conceived, FMEA was intended to be used by a cross-functional, multidisciplinary team of individuals because the causes of product and system failures can be present anywhere within an organization. However, there is nothing that prevents the solo practitioner from applying it. Therefore, assembling a team was not done for this analysis. The next step in an FMEA is to describe the focus of the analysis, which is generally a product, process, or system. In this case, there are two foci – the scientific research process and the policy process as applied to university technology transfer. Once the foci were defined, they were visually depicted to ensure a thorough understanding of the focus of the analysis. For an FMEA, this consists of preparing a functional block diagram for systems and products or a process flowchart for processes and services. For this analysis, process flowcharts for the scientific research process and policy process were created.

In FMEA, the fourth step is to list potential failure modes, causes of failures, and their effects and then collect data about their frequencies. This step was modified for this analysis. Instead, the various conceptualisations of technologies (identified through the thematic analysis described above) and their effects were listed. Inductive reasoning supplemented with other various techniques, such as brainwriting and scenario planning, was used to postulate the effects of these conceptualisations on university technology transfer research and public policy.

A primary objective of an FMEA is to prioritize failure modes for mitigation. As such, the next step in an FMEA is to assign severity, occurrence, and detection values to each failure mode and then use this data to determine which failure modes would be prioritized for mitigation given limited time and resources. For the purposes of this study, prioritization was not strictly necessary. However, an analogous exercise was performed to help prioritize conceptualisations for integration in the event that addressing all identified conceptualisations was not feasible.

As FMEA was originally conceived, prioritization of a failure mode was based on its risk priority number (RPN) which is a function of the severity of the failure mode (S), frequency of the failure mode’s occurrence (O), and difficulty of detecting the failure mode (D). The RPN is calculated by the following equation:

Values for each variable in the above equation are assigned using ordinal values. However, this prioritization technique has been the focus of much criticism of its validity as a measure (Bradley & Guerrero, 2011). Strictly speaking, multiplying ordinal values has no meaning because the interval between ordinal categories is meaningless. Various other techniques have been proposed to address these criticisms (see e.g., Bradley & Guerrero; Franceschini & Galetto, 2001; Yager, 1993).

For this analysis, the conceptualisations uncovered in the thematic analysis were ranked using a priority of focus score (PFS) which is a function of the perception of how consequential the effects of the conceptualisation are (

E), the prevalence of the conceptualisation (

P), and the perceived propensity for modification of the tendency to employ the conceptualisation (

M). Each of these variables were assigned ratio-interval values to avoid the problems associated with using ordinal values. The PFS was calculated using the following formula:

The effect value (

E) was operationalised using the number of disadvantageous attributes of each conceptualisation of technology identified in the sample. The Beta distribution was used to assign ratio scale values for

P based on the data that was collected for the thematic analysis, where α is the number of instances in which the conceptualisation was present and β is the number of instances in which the conceptualisation was not present. The propensity for modification (

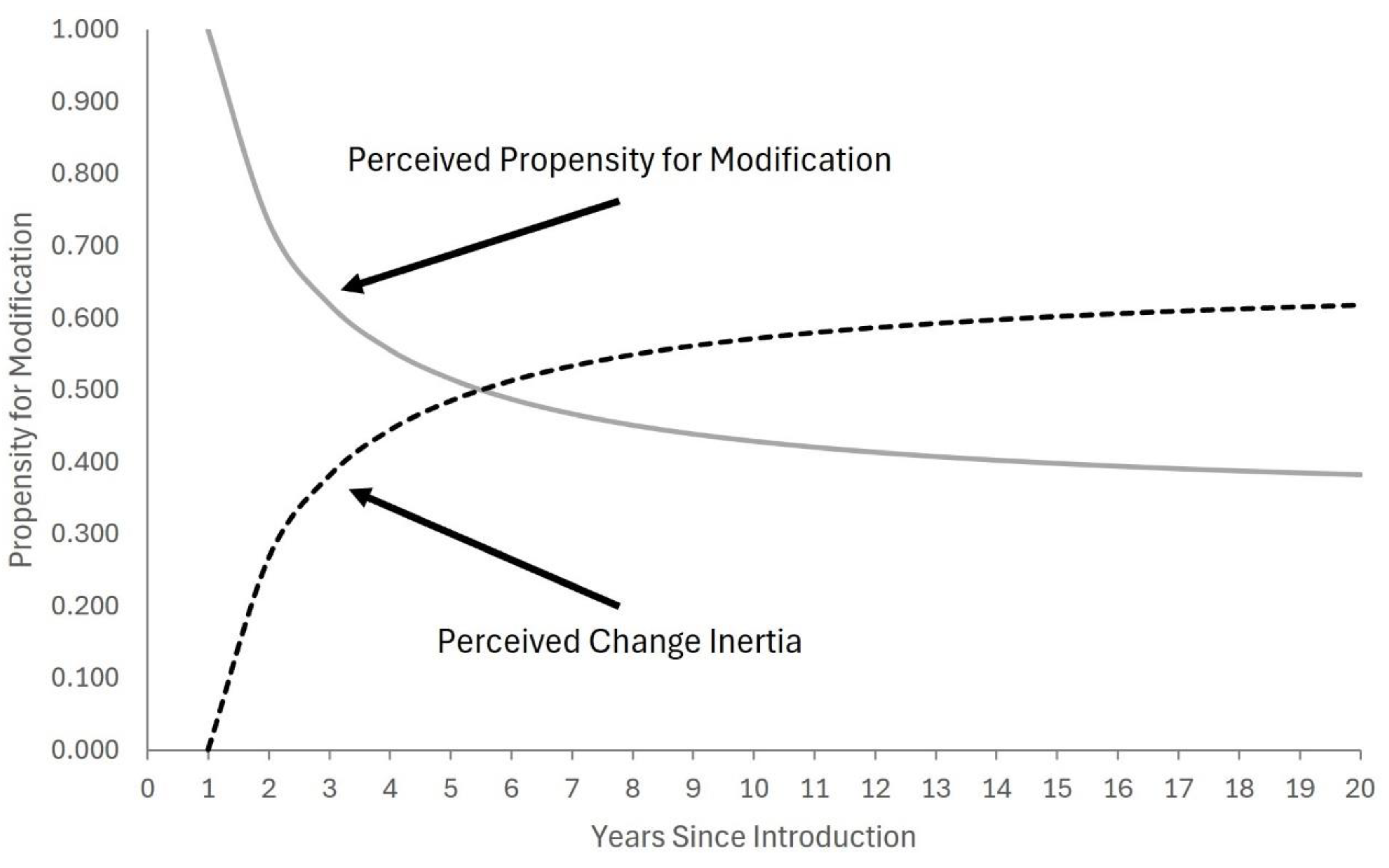

M) was operationalised using the number of years since the earliest instance of the conceptualisation in the sample. This was based on the idea that the longer a conceptualisation has been in use, the greater the amount of resistance (i.e., change inertia) to altering people’s inclination to employ a conceptualisation that will be encountered. Thus, the propensity for modification of the inclination to employ a conceptualisation will be lower. The value of

M was assigned using a transformation of the rational equation

as follows:

where

x is the number of years since the earliest instance of the conceptualisation in the sample. This function was chosen to model the relationship between time and the propensity for modification under the premise that there would be a relatively steep decrease in the propensity for modification (i.e., increase in the change inertia) in the initial years following the introduction of a conceptualisation, but there would also be diminishing marginal decreases (i.e., marginal increase in change inertia) over time (see

Figure 1). However, a highly accurate and precise description of the relationship was not necessary for the analysis. One that generally described the relationship would suffice.

The PFS was used to prioritize the conceptualisations on which to focus when attempting to integrate conceptualisations to formulate an alternative conceptualisation. This was useful because not being able to integrate all conceptualisations was a distinct possibility.

Analysis Results

This section of the paper presents the results and findings of the analysis of the data. They are reported without interpretation.

Current Conceptualisations of Technology

A total of 26 items from the literature, including peer-reviewed published journal articles and doctoral dissertations, were examined to determine how university technology transfer researchers conceptualise technology (see

Table 1). Literature items were included if they either (1) focused on identifying variables or conditions to explain success or failure in U.S. university technology transfer, (2) investigated mechanisms of university technology transfer, (3) discussed the conceptualisation of technology in a context relevant to U.S. university technology transfer, or (4) they examined U.S. public policy regarding university technology transfer.

Table 1.

Literature Reviewed for the Analysis.

Table 1.

Literature Reviewed for the Analysis.

| Source |

Synopsis of Source |

| Alkaabi and Ramadani (2022) |

Examined several factors assumed to contribute to the development of an innovation ecosystem in universities including scientific and technological research capability, intellectual property, collaboration and communication, culture, and economic and commercialisation activity. |

| Arshadi and George (2008) |

Presented an empirical analysis of U.S. university technology transfer activities based on research expenditures, patents, executed licenses, and startup activity. |

| Bozeman (2000) |

Synthesized and criticized the recent literature on U.S. technology transfer from universities and government laboratories to the private sector. Proposed a contingent effectiveness model of technology transfer. |

| Cardozo, Ardichvili, and Strauss (2011) |

Described an economic model for the analysis of the university technology commercialization industry based on an organizational population ecology perspective. |

| Carlsson and Fridh (2002) |

Using data from 1998, this paper examined the role of technology transfer offices at 12 U.S. universities in commercializing research results using patents, licenses, and start-ups of new companies as the primary metrics. |

| Choi (2009) |

Discussed technology conceptualisation, technological diffusion, communication channels, mediating factors, and technology transfer models and proposed a new integrated model of technology transfer. |

| Leo-Paul Dana, Len, and George (2001) |

Compared knowledge management practices in organizations in Singapore with those of organizations in Silicon Valley in the United States of America. |

| Leo-Paul Dana, Korot, and Tovstiga (2005) |

Examined organizational knowledge-based practices in Silicon Valley in the United States of America, Singapore, The Netherlands, and Israel. |

| Di Stefano, Gambardella, and Verona (2007) |

Proposed a model of technological innovation that is driven by demand factors. |

| Ferguson (2014) |

Examined policymakers’ understanding of the ‘valley of death’ and compared it to the historical evidence about the phenomenon. |

Table 1.

(continued). Literature Reviewed for the Analysis.

Table 1.

(continued). Literature Reviewed for the Analysis.

| Source |

Synopsis of Source |

| Huang, Ken, Wang, Wu, and Shiu (2011) |

Presented non-parametric statistics describing the performance of technology transfer efforts for 94 U.S. universities. |

| Huggett (2014) |

Discussed how leaders of university technology transfer offices are changing how they perceive their mission and the methods they use to transfer technologies. |

| J. Kim, Anderson, and Daim (2008) |

Using data from 2001 to 2005, this paper investigated the differences among 51 U.S. universities that are considered efficient at technology transfer and the changes in their performance over time. The paper also proposes the efficiency pattern diagram as a new approach to identify changing technology transfer patterns. |

| Jisun Kim, Diam, and Anderson (2009) |

Presented a review of the literature on university technology transfer focusing on the characteristics of universities and metrics used to assess performance. The authors propose a phase-based process to measure technology transfer success. |

| Y. Kim (2013) |

Examined the technology transfer productivity of 30 major U.S. universities using data envelopment analysis and input-output combination measures. |

| Kremic (2003) |

Compared and contrasted the motives for pursuing technology transfer of corporations and government agencies whose missions include scientific research and the methods they employ. |

| Kundu, Bhar, and Pandurangan (2015) |

Summarized the extrinsic and intrinsic factors relative to the technology provider and technology recipient dyad. |

| Lall (2001) |

A collection of articles in the field of technology transfer that discuss theory and concepts, the drivers of technology development and transfer, and technology transfer in developing countries. |

| Leonard-Barton (1990) |

Discusses technology transfer from the organizational perspective. |

| Lowe (2002) |

Examined why university inventors found firms and assessed the role and experience of this class of start-up founders in developing and commercializing university-owned technologies. |

Table 1.

(continued). Literature Reviewed for the Analysis.

Table 1.

(continued). Literature Reviewed for the Analysis.

| Source |

Synopsis of Source |

| Markman, Gianiodis, and Phan (2009) |

Analysed the correlation of commercialization outcomes with sponsored research, licensing-for-cash strategies, technology transfer office autonomy, royalty share allocated to inventors and departments, and compensation levels of technology transfer office staff. |

| Munteanu (2012) |

Analysed the correlation of technology development stage and licensee type. |

| Phan and Siegel (2006) |

Reviewed and synthesized the literature on the effectiveness of technology transfer mechanisms and presented recommendations for enhancing technology transfer effectiveness. |

| Powers (2003) |

Examined the impact that financial, physical, human capital, and organizational resources of universities have on patenting, licensing, and income generation from licenses, and to what degree the external environment in which a university is located matters to technology transfer outcomes. |

| Williams and Gibson (1990) |

A collection of 14 papers that discuss technology transfer from various perspectives such as group dynamics, organizational studies, media, and interpersonal communication. |

| York and Ahn (2012) |

Reviewed the literature describing critical factors that contribute to successful university technology transfer and examined those factors within a stratified sample of four comparative case studies of peer university technology transfer offices to identify models of relative success and failure based on similarities and differences among the factors identified in the literature. |

A total of 16 U.S. public policies relevant to university technology transfer were examined to determine how U.S. policymakers conceptualise technology (see

Table 2). These included both public laws and executive orders enacted since 1980, which marks the beginning of the modern era of university technology transfer in the United States.

Table 2.

Federal Legislation and Executive Actions Relevant to University Technology Transfer.

Table 2.

Federal Legislation and Executive Actions Relevant to University Technology Transfer.

| Policy |

Relevant Provisions |

| Pub.L. 96-517Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 |

Permitted universities, nonprofit firms, and small businesses to take title to inventions derived from federally funded research as a way to incentive these organizations to facilitate the use of the inventions to benefit the public interest. |

| Pub.L. 96-480Stevenson-Wydler Technology Innovation Act of 1980 |

Mandated that federal laboratories establish an Office of Research and Technology Application (ORTA) to facilitate their active technical cooperation with the private sector. |

| Pub.L. 97-219Small Business Innovation Development Act of 1982 |

Mandated that federal agencies set aside a specific portion of their extramural research budgets to fund research and development projects within the scope of their agency missions to be performed by small businesses in the private sector. |

| Pub.L. 98-462National Cooperative Research Act of 1984 |

Enabled private sector businesses to participate in joint pre-competitive research and development ventures without violating federal antitrust laws. Eliminated treble damages in antitrust litigation arising from such ventures. |

| Pub.L. 99-502Federal Technology Transfer Act of 1985 |

Established the Federal Laboratory Consortium (FLC) for Technology Transfer and enabled government-owned, government-operated federal laboratories (GOGOs) to directly enter into cooperative research and development agreements (CRADAs) with private sector businesses. |

| Executive Order 12591Facilitating Access to Science and Technology |

Further specified Pub.L. 99-502, Pub.L. 98-620, and Pub.L. 96-517 for administrative purposes to ensure that federal agencies and laboratories assist the technology transfer efforts of universities and private sector organizations. |

| Executive Order 12618Uniform Treatment of Federally Funded Inventions |

Expanded upon Executive Order 12591 to harmonize across all Federal agencies the policies for administering patents and licenses for inventions created with federal funding support. |

| Pub.L. 100-418Ominbus Trade and Competitiveness Act |

Established Manufacturing Technology Centers (MTCs) and designated the National Institute of Science and Technology (NIST) as the lead agency to administer them. Specified requirements regarding the equitable access for United States persons to foreign-developed technology and the export of technologies. |

| Pub.L. 101-189National Competitiveness Technology Transfer Act of 1989 |

Extended the ability to execute CRADAs with private sector businesses to all government-owned contractor-operated federal laboratories (GOCOs). |

Table 2.

(continued). Federal Legislation and Executive Actions Relevant to University Technology Transfer.

Table 2.

(continued). Federal Legislation and Executive Actions Relevant to University Technology Transfer.

| Policy |

Relevant Provisions |

| Pub.L. 102-245American Technology Preeminence Act of 1991 |

Authorized appropriations to be available for Regional Centers for the Transfer of Manufacturing Technology, State Technology Extension Program, Advanced Technology Program, and Satellite Manufacturing Centers. |

| Pub.L. 103-160National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1994 |

Directed the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) to promote dual-use technology via technology reinvestment. |

| Pub.L. 104-113National Technology Transfer and Advancement Act of 1995 |

Enacted changes to ease the ability of private sector businesses to obtain exclusive license to inventions that result from cooperative research with the federal government. |

| Pub.L. 106-404Technology Transfer Commercialization Act of 2000 |

Requires license applicants for federally owned inventions to commit to achieving practical application of the invention within a reasonable time. |

| Pub.L. 108-453Cooperative Research and Technology Enhancement (CREATE) Act of 2004 |

Amended federal patent law to clarify the criteria for obviousness and created a framework to facilitate inter-organizational research collaborations that do not create prior art that would serve as a bar to obtaining a valid patent. |

| Pub.L. 112-29Leahy-Smith America Invents Act |

Reformed patent laws and instituted "first inventor to file" patent registration system. |

| Pub.L. 117-167CHIPS and Science Act |

Authorizes funding to support technology transfer capacity building for research institutions to advance the development, adoption, and commercialization of technologies. |

The thematic analysis of the selected literature and public policies identified 15 distinct conceptualisations of technology applied to university technology transfer in the United States (

Table 3).

Impact on Technology Transfer Research and Public Policy

Process flowcharts were created for the scientific research process (

Figure 2) and the public policy process (

Figure 3) as applied to university technology transfer.

The disadvantages (i.e., undesirable effects) and advantages (i.e., desirable effects) of each conceptualisation of technology were postulated as described above (see

Table 4).

Table 4.

The Disadvantages and Advantages of the Various Conceptualisations of Technology.

Table 4.

The Disadvantages and Advantages of the Various Conceptualisations of Technology.

| |

Patentable subject matter |

Any result of scientific research that can be licensed |

A new discovery from scientific research |

Any publishable result generated from scientific research |

New knowledge created through scientific research |

The effective use of knowledge |

Knowledge that extends human capabilities |

Knowledge and artifacts that create new possibilities for humans |

Knowledge and artifacts that serve as means to various ends |

An ends-driven extension of human capabilities |

An output of human creativity comprising knowledge, objects, processes, and volition |

Human ways of doing things that are guided by values, beliefs, and patterns of behaviour |

A modification to current processes and behaviours |

An innovation |

An output of scientific research distinct from knowledge |

| Disadvantages of Conceptualisations |

| Does not account for the influence of culture on technology |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

| Excludes artifacts |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

| Excludes technologies that are not patentable subject matter |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Excludes forms of technology that are not conducive to licensing |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Excludes technologies not created through organized scientific research |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| Excludes technologies that are not conducive to being published |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Excludes technologies that are not considered “new” |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| Excludes technologies that are not used |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Impedes generalizations across geopolitical boundaries |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Implies that only patented technologies have value |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Includes instances that one would not consider technology |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| Abstruse and esoteric |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| Vague or ambiguous |

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

Table 4.

(continued). The Disadvantages and Advantages of the Various Conceptualisations of Technology.

Table 4.

(continued). The Disadvantages and Advantages of the Various Conceptualisations of Technology.

| |

Patentable subject matter |

Any result of scientific research that can be licensed |

A new discovery from scientific research |

Any publishable result generated from scientific research |

New knowledge created through scientific research |

The effective use of knowledge |

Knowledge that extends human capabilities |

Knowledge and artifacts that create new possibilities for humans |

Knowledge and artifacts that serve as means to various ends |

An ends-driven extension of human capabilities |

An output of human creativity comprising knowledge, objects, processes, and volition |

Human ways of doing things that are guided by values, beliefs, and patterns of behaviour |

A modification to current processes and behaviours |

An innovation |

An output of scientific research distinct from knowledge |

| Advantages of Conceptualisations |

| Easily understood |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

| Intuitively appealing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| Consistent with the commonly held instrumental conception of technology |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| Consistent with popular conceptions of technology |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

| Easily operationalized |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Appears to exclude all instances that one would not consider technology |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Appears to include everything that one would consider technology |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

| Encompasses the influence of culture on technology |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

The prevalence of each conceptualisation of technology identified from the thematic analysis was estimated as described above (see

Table 5).

The propensity for modification of the inclination to employ each conceptualisation was estimated as described above (see

Table 6).

Using this information, the PFS for each conceptualisation of technology was calculated as described above (see

Table 7). Higher PFS values indicate a higher ranking for prioritisation.

An Alternative Conceptualisation of Technology

The essence of a thing is that which pervades every instance of every kind of the thing, but it is not the thing itself. The essence of technology is not technological (Heidegger, 2009). It must be something more fundamental. It is this fundamental characteristic around which one can ground a conceptualisation of technology. There seems to be general agreement that instrumentality is a fundamental characteristic of technology, but technology is far more than just instrumentality (Heidegger). Instrumentality implies causality and causes, which provides a clue to the other fundamental attributes of technology. The four kinds of causes that philosophy posits are (1) causa materialis, which is the matter out of which a thing is made, (2) causa formalis, which is the shape into which the matter is formed, (3) causa finalis, which is the end that is achieved, and (4) causa efficiens, or that which brings about the effect (Heidegger).

As an alternative, one can conceptualize technology in terms of information. Using this approach, technology can be defined as culturally influenced information that one or more social actors has synthesized, organized, and structured so that it extends their capabilities or those of other social actors to pursue the objectives of their motivations, and is embodied in such a manner to enable, hinder, or otherwise control its access and use. This definition captures the four causes that are implied with instrumentality. It is also consistent with the observation of Lall (2001) that technology must be embodied in specific items as well as the notions of other scholars that have commented on the subject (see e.g., Herschbach, 1995; Leonard-Barton, 1990; Stoneman, 2002; Weber, 1922/1964; Williams & Gibson, 1990).

Conceptualising technology in terms of information is not an entirely new idea in the discourse about technology transfer. Williams and Gibson (1990) offered a definition of technology as “information that is put to use” (p. 13). Leonard-Barton (1990) expanded on this by offering that technology was knowledge embodied in an artifact that facilitates the completion of some task. This is consistent with the instrumental conceptualisation of technology but relegates technology to mere means. Leonard-Barton further stipulated that such knowledge is technology only when captured in a form that can be communicated. Herschbach (1995) acknowledged that technology embodies knowledge and argued that the knowledge embodied in technology only has meaning in the context of human activity. This suggests that knowledge and technology are distinct and that technology is a superset of knowledge. Stoneman (2002) also pointed out that technology has been defined as information or knowledge within the literature and doing so has certain analytical advantages.

Information sciences literature provides a foundation for conceptualising technology in terms of information. The DIKW (data, information, knowledge, wisdom) hierarchy is the primary paradigm used in information science and knowledge management (Frické, 2019). Conceptualising technology in terms of information as described in the DIKW hierarchy has at least one advantage. There is general agreement about the elements of the hierarchy, their definitions, and their ordering (Rowley, 2007).

Each category in the DIKW hierarchy includes the categories below it (Frické, 2019). According to Frické, data are symbols that represent the observable properties of objects, events, and environments (i.e., phenomena). By definition, intentionally false statements are not data (Frické). Data are assertions believed to accurately represent the nature of reality in the physical and social world. However, data can be inaccurate or incorrect even when they are intended to accurately represent reality.

Information, in turn, is data that has been processed to answer a query (Frické, 2019). By analogy, information is to data what velocity is to location in physics. Velocity is the first order derivative of location with respect to time. Similarly, information is essentially the first order transformation of data. The difference between data and information is more function than form (Frické). For example, the symbols in documents and reports about federal obligations to universities for research and development represent data. They become information when one compiles them into the table to answer the question of whether federal funding for research and development is generally increasing or decreasing.

Knowledge in the DIKW hierarchy is information that has been transformed into instructions to enable control of a system – that is, know-that and know-how that can be applied to achieve an end (Frické, 2019). It is essentially the first order transformation of information and the second order transformation of data. In this respect, technology as defined above has a lot in common with knowledge as defined in the DIKW hierarchy. Whether technology and knowledge are synonymous, or one is a superset of the other remains to be debated and is beyond the scope of this paper.

It is important to note that the term knowledge is used differently in the DIKW framework than in western philosophy and everyday language. In western philosophy, knowledge is that which is known and the traditional definition of what it means to know is “justified true belief” (Ichikawa & Steup, 2018). To know means to justifiably believe an assertion is a true reflection of the physical and social world. However, since the 1960s epistemologists have posed and debated challenges to this definition of knowledge (Ichikawa & Steup). The way the term knowledge is used in everyday language is more appropriately called data and information in the DIKW hierarchy. For example, a political science professor might claim to have a significant amount of knowledge about the U.S. political system. Applying the DIKW framework, it is more appropriate to say that the professor has mentally retained a large amount of data and information about the U.S. political system. That data and information do not become knowledge until the professor applies them in some way to control a system, such as describing a new voting system that more closely resembles an ideal political mechanism.

Finally, in the context of the DIKW framework, wisdom is a more elusive construct. There has been limited discourse about wisdom in the information sciences and knowledge management literature (Rowley, 2007). Frické (2019) argued that wisdom is knowledge that is applied to achieve an end. Some scholars conceive of wisdom as accumulated knowledge from one domain applied to new situations or problems (Rowley, p. 174). However, an adequate definition of wisdom is not necessary to apply the DIKW hierarchy as a framework to underpin a conceptualisation of technology. Since technology is defined as a form of information, definitions for the first three components (data, information, and knowledge) will suffice.

Frické (2019) further argued that the DIKW hierarchy is an incomplete framework and should include document and sign as two additional concepts. This aligns with the notion expressed by Leonard-Barton (1990) that knowledge must be captured in communicable form to be considered technology. The alternative conceptualisation of technology proposed above captures this notion. Frické also argued that documents are culturally specific tools for communicating knowledge, information, and data. This harkens to the cultural school of thought regarding the definition of technology. The proposed alternative conceptualisation of technology captures these concepts through its requirements about embodiment.

Some technology transfer studies have broadened the idea of technology to include “academic knowledge” in the epistemological sense of the term knowledge (see e.g., González-Pernía, Kuechle, & Peña-Legazkue, 2013). By making a slight modification to the DIKW conceptualisation of knowledge, one can harmonize it with the epistemological meaning of the term. Defining knowledge in the DIKW hierarchy as information that one can justifiably believe is a true reflection of the physical and social world that is used to explain, predict, or control phenomena better aligns the term with its use in epistemology while retaining its role in the DIKW hierarchy. Thus, if one conceptualises technology as derived from information, it is apparent that technology is closely related to knowledge as conceptualised in both epistemology and the DIKW hierarchy. Moreover, technology and knowledge might well be synonymous. Within the framework of the DIKW, each category includes the categories below it (Frické, 2019). As such, knowledge consists of information. Likewise, technology as defined in the proposed alternative conceptualisation is information that has been transformed; but the information itself is conserved. As such, technology, like knowledge, consists of information.

Discussion

The aim of the previous section was to integrate the conceptualisations of technology found in the literature and public policy into an alternative conceptualisation and convincingly demonstrate that it has merit. This section of the paper considers the implications of the proposed alternative conceptualisation of technology for efforts to understand and explain the phenomenon of university technology transfer and craft effective public policy.

Current Conceptualisations of Technology

In most cases the meaning of the term technology is ambiguous in both the literature and public policy. Generally, the term is not explicitly defined, and its meaning is only implied. Consequently, one must infer how the authors define technology in the context in which the term is being used. Moreover, both academic literature and public policy often imply different meanings to the term technology within the same application, which further exacerbates the problem. In some cases, what the authors mean by the term technology cannot be inferred from context at all.

Frequently, scholars and policymakers conceptualise technology as patentable subject matter or patented inventions. This notes a considerable narrowing of the conception of technology since the time of ancient Greece (see

Figure 4).

Both research methodologies and public policy seem to conflate technology with the mechanisms for transferring technology. This becomes more apparent when one considers the technology transfer process from technology creation to conveyance to third parties (

Figure 5).

It is not clear if researchers’ conceptualisations of technology cause them to operationalise the concept as they do, or if the data available to them causes them to operationalise the technology in ways that influence their conceptualisations. A similar dynamic may be at play with policymakers. This is an issue that warrants further investigation. Both researchers and policymakers seem to skirt the issue by not bothering to explicitly define their conceptualisations of technology in their publications and legislative measures, respectively.

Concerns and Challenges

The literature on mathematical and logical definitions provides a basis for evaluating conceptualisations of technology. It reveals several concerns and challenges associated with how technology has been conceptualised in scholarly research and public policy regarding university technology transfer.

The standard theory of definition offers two primary criteria for sound definitions. The eliminability criterion requires that in any application of the term, one must be able to replace the definiendeum with the definiens without changing the meaning of the term in the application and the conservativeness criterion requires that the definiens only explains the meaning of the definiendeum without adding any additional meaning or content beyond the definiendeum (see Belnap, 1993; Gupta & Mackereth, 2023). The various conceptualisations of technology identified in this analysis and how they are applied often seems to violate one or both of these criteria.

In addition to the two criteria described above, education practitioners have also offered several guidelines for crafting proper lexical definitions (see

Table 6). These guidelines are also useful for identifying potential problems with the current conceptualisations of technology in university technology transfer research and public policy. Most conceptualisations appear to fall victim to ambiguity and vagueness as well as the lack of appropriate scoping.

Table 6.

Guidelines for Crafting Rigorous Definitions.

Table 6.

Guidelines for Crafting Rigorous Definitions.

| Guideline |

Comments and Examples |

| Comply with standards for proper grammar. |

Use quotes around the term that one is defining. |

| Eliminate circularity. |

Do not use words contained within the term to define the term.

For example, do not state that “technology transfer is the transfer of technology from…” |

| Communicate the essential meaning of the term being defined. |

Do not just list characteristics.

Define the fundamental nature of the concept or construct. |

| Scope the definition appropriately. |

The definition should only apply to instances that are members of the set one is defining.

The definition should capture all instances that are members of the set one is defining.

The definition should eliminate all instances that are not members of the set one is defining. |

| Eliminate ambiguity and vagueness. |

Do not use figurative language.

Do not use similes and metaphors. |

| Eliminate affective terminology. |

The definition should not include secondary or associated meanings that express emotion. |

| Use positive framing rather than negative framing. |

Define what the concept or construct is rather than what it is not. |

| Conform to the eliminability criterion. |

The definiendeum should be able to replace the definiens without changing the meaning of the concept or construct in the application. |

| Conform to the conservativeness criterion. |

The definiens should only explain the meaning of the definiendeum without adding any additional meaning or content beyond the definiendeum. |

Defining technology and measuring the technology transfer phenomenon have posed significant challenges for researchers (Bozeman, 2000). Typically, studies on university technology transfer have not bothered to define the term technology. However, they generally seem to conform to the instrumental definition when operationalising the concept. Scholarly research studies often operationalise technology, in the context of university technology transfer, as a disclosure of potentially patentable subject matter to a university or a patent right to a government recognized invention (see e.g., Anderson, Daim, & Lavoie, 2007; González-Pernía et al., 2013; Markman et al., 2009). However, this approach is problematic. It fails to recognize that patentable subject matter is defined by law, which varies across geopolitical borders. What is patentable in one country may not be patentable in another country. Moreover, what is considered patentable subject matter may change over time and thus is not stable. As such, not all technology is patentable.

The ambiguity surrounding the meaning of technology is vexing for both public policy and society in general. For example, there are medications such as anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, and mood stabilizers that are used to treat various mental illnesses. Likewise, the L.E.A.P. (Listen, Empathize, Agree, Partner) method developed through scientific investigation helps mentally ill persons to accept treatment (Amador, 2011). The U.S. government and society in general tends to view the medications as technology but generally does not view advances like the L.E.A.P. method as technology. Moreover, application of the L.E.A.P. method by society does not show up in any technology transfer metric used to measure the transfer of research discoveries to the private sector. As such the L.E.A.P. method and other similar examples do not get factored into the policy debate about technology transfer in any significant way. However, if the L.E.A.P. method were patentable subject matter and patented accordingly, society and government metrics would likely recognize it as technology. This seems rather arbitrary and demonstrates a narrowing of the meaning of technology from applied science and instrumental reason to patentable subject matter, which is evident in current U.S. public policy regarding technology transfer.

Advantages of the Proposed Conceptualisation of Technology

The alternative conceptualisation of technology presented in this paper mitigates may of the disadvantages of the current conceptualisations identified in this examination. A primary advantage of the proposed alternative conceptualisation of technology is that it can be broadly applied. For example, a peer-reviewed journal article is simply information about a phenomenon that is embodied in a periodical format to facilitate its dissemination and accessibility for use. A patent (under U.S. patent law) is simply information about a composition of matter, manufacture, method, or improvement to a manufacture or method that is embodied in documentation that conforms to guidelines dictated by the government to facilitate its accessibility and use while enabling the patent holder to leverage the coercive powers of the state to prevent others from using the information for a specified period. A trade secret is simply information about something that has inherent economic value that is embodied in documentation, human memory, and protocols to control its accessibility and use while preventing unwanted parties from accessing and using the information. A Clovis point1 is simply information about using pressure flaking to create a leaf shaped projectile point broader near its midsection and toward its base that is embodied in physical form to facilitate its use to achieve an end. A smartphone is information about using digital signals and electronic displays to communicate with others that is embodied in physical form to facilitate its use by the public. All these examples represent embodiments of technology. It is possible, and quite likely, that the nature of the embodiment somehow affects the transfer of the technology from one party to another. This seems to play a role in issues surrounding how university technology transfer is measured and evaluated.

Implications for the Discourse About University Technology Transfer

The conceptualisation and operationalisation of university technology transfer seems to have been troublesome for scholarly research on the subject. How technology itself is conceptualised and defined has likely contributed to and exacerbated this difficulty.

Like the term technology, there is no universally accepted definition of the general concept of technology transfer. As with technology, most studies of technology transfer fail to explicitly define the term. The definition of technology transfer seems to vary depending on the context of the research. For example, an investigation of the effects of international technology transfer on welfare under the conditions of Bertrand and Cournot competition defined technology transfer as “the process of transferring a new technology from a firm in one country to a firm in another country” (Kuo, Lin, & Peng, 2016, p. 214). However, this definition is a bit circular. It also eliminates scenarios that one would generally consider to be cases of technology transfer, such as the transfer of technology between firms in the same country. Thus, it violates the general guidelines for constructing definitions (see Dusek, 2006, p. 30).

Another example is Kundu et al. (2015), which defined technology transfer as “the process by which technology, knowledge, and information developed in one organization for one purpose is applied and utilized by another area in another organization, for another purpose” (p. 70). They seem to have been striving for a definition that comprehensively captures the technology transfer phenomenon. However, this definition also violates generally accepted guidelines for crafting definitions because it is overly restrictive and excludes scenarios that should be included in the definition of technology transfer such as the use of technology, knowledge, and information by another organization for the same purpose for which the creating organization used it or intended its use.

Speser (2012) defined technology transfer as “the transfer of technology from one person to another across organizational lines” (p. xxiii). This definition does attempt to overcome the problem of reification of the organization construct, which is a relevant ontological issue that impacts how the phenomenon of university technology transfer is studied and understood. However, it is also circular and violates the generally accepted rules for formulating definitions. It fails to clarify what it means for a technology to be “transferred.” Moreover, the definition of technology that Speser used is inconsistent. At one point, Speser defined technology as “a physical embodiment of an ideal that is helpful for accomplishing a task” (p. 16) but elsewhere argued that technologies are only those ideas that can be embodied in such a form that their creators can secure property rights (i.e., patentable subject matter) and rely on the coercive powers of the state to enforce those rights (p. 7-8). Again, this exemplifies the narrowing conception of technology as patentable subject matter.

The use of the term commercialisation further exacerbates the issue of conceptualising and defining university technology transfer. The term commercialisation is often used as a synonym for technology transfer; however, it is more appropriately applied to instances of technology transfer endeavours driven by profit motives (see e.g., Fasi, 2022; Gulbrandsen & Rasmussen, 2012; Kirchberger & Pohl, 2016; Mercelis, Galvez-Behar, & Guagnini, 2017). But this is not always the case. Moreover, technology transfer can occur in the absence of a profit motive.

In defining and operationalising technology transfer, it is important to distinguish between it and the closely related phenomenon of technology diffusion. Technological diffusion is concerned with the dissemination of a technology throughout an industry, economy, or society after first incorporation whereas technology transfer has more to do with the introduction and first incorporation of a technology into a setting (Stoneman, 2002).

Generally, studies of technology transfer seem to conflate it with the mechanisms for achieving it. Moreover, most research studies of university technology transfer appear to select indicators and measures more for convenience rather than to maximize construct validity. This is possibly a direct function of how technology itself is conceptualised. However, the measures available to researchers could be determining how researchers conceptualise technology. Licensing and new venture formation are typically used as indicators of technology transfer. Research collaborations and faculty consulting agreements, although discussed in the literature, are used far less frequently. Executed patent licenses, established new business entities, and executed sponsored research agreements have also been used as proxies for technology transfer (see e.g., González-Pernía et al., 2013; Hallam, Wurth, & Mancha, 2014; Markman et al., 2009; Tseng & Raudensky, 2014).

All of the aforementioned approaches have their shortcomings. For example, if a private sector organization executes an exclusive license for a university-created technology but takes no further action because it wants to protect the market position of an existing product or service, should one consider this a case of university technology transfer? Or, if a new business entity is created explicitly to execute a license for a university-created technology but the venture fails to successfully introduce a market offering using the technology, should one consider this a case of university technology transfer? Such scenarios occur, show up in the metrics, and are often associated with significant financial transactions but neither really seems to produce incremental benefit for society. Moreover, the use of such operationalisations tends to reinforce the narrow conceptualisation of technology as patentable subject matter.

Several scholars have commented on the limitations of typical conceptualisations of technology transfer. Approaches for measuring technology transfer success have transitioned from input metrics to output indicators to outcome and impact measures, the last of which technology transfer practitioners believe are more appropriate (Fraser, 2010). University technology transfer outcomes are only partially reflected in measures of income generation and new business venture formation (Carlsson & Fridh, 2002). Using licensing revenue as the primary measure of technology transfer success is limiting because it constitutes only a portion of the outcomes of technology transfer efforts (Herzog & Wasden, 2013). Other outcome and impact phenomena to which technology transfer contributes include the economic impact on the area in immediate proximity to the institution, number of lives saved, improvements in the lives of individuals, and increases in the competitiveness of commercial enterprises (Fraser). Conceptualising technology more broadly can possibly cause scholars to think about university technology transfer more comprehensively and thus lead them to identify additional outcomes that are worthy of consideration in public policy discussions.

Conceptualising technology as information may help bring some clarity to the definition of technology transfer, particularly university technology transfer. At the most basic level, one may think of technology transfer as simply the conveyance of technology (as defined above in terms of information) from the possession of one social actor to the possession of another social actor for the purpose of applying the technology in a setting in which it has not previously been applied. Since technology is defined in terms of information, technology transfer is simply the conveyance of information. This conveyance may occur in various contexts such as between affiliated or unaffiliated social actors and across geopolitical borders. It may occur in various manners such as formally or informally. It may occur through various mechanisms such as fee-based patent licenses, non-fee creative commons licenses, product sales, service delivery, or collaborative work arrangements. It may also occur through various methods such as sanctioned or illicit. Moreover, social actors may engage in technology transfer to achieve a variety of objectives such as generating financial gain, increasing the competitive advantage of a commercial enterprise, increasing the standard of living within a country, facilitating broader economic development within a geopolitical border, or simply developing culture and cultural structures.

Using the proposed alternative conceptualisation of technology, one can go on to conceptualise university technology transfer as technology (as alternatively defined above in terms of information) created by university researchers through systematic methods and practices of inquiry that is knowingly and willingly conveyed to other parties who intend to apply the technology in a setting in which it has not previously been applied to achieve an end. This end is often associated with a profit motive for the receiving party, but this need not be the case. Technology transfer can and has occurred in the context of humanitarian efforts in which the profit motive is minimal or even non-existent (Association of University Technology Managers, 2021).

This broader definition of technology expands the possibilities for various operationalisations of the construct in university technology transfer research. For example, rather than relying on patents as the de facto operationalisation, other embodiments of technology can be used such as patent applications, trade secrets, journal article manuscript submissions, project reports to funding agencies, or even blog posts. Such expansion is highly advantageous given the trends in university technology transfer in which greater emphasis is being placed on non-patented forms of intellectual property such as data, copyrights, know-how, and know-what. Thus, the broader conceptualisation could lead to increased construct validity.

Additionally, an expanded conceptualisation of technology potentially opens new approaches to research on the topic of technology transfer, particularly university technology transfer. A great deal of university technology transfer research relies on correlational analyses and various forms of multiple regression analysis. The data requirements of these methods constrain the types of research questions that can be examined and thus reinforce a narrow conceptualisation of technology. By broadening the conceptualisation of technology, it forces the researcher to think about university technology transfer more expansively and consider other types of operationalisations and data. Thus, researchers are challenged to contemplate and conceive new methodologies, methods, and techniques.

Consider for example, the true incidence of university technology transfer. How technology is conceptualised and operationalised greatly affects the resulting calculation of incidence rate. Consequently, the estimated true incidence of university technology transfer can vary widely. It is also apparent that the problem is further exacerbated when one considers that the definition of technology also influences the conceptualisation and operationalisation of university technology transfer, which contributes to additional variation in the possible calculations of the incidence rate.

Implications for Public Policy Regarding University Technology Transfer

The alternative conceptualisation and definition of technology presented in this paper may cause policy analysts and policymakers to think more comprehensively about technology transfer and what it means to successfully transfer technologies derived from federally funded research to the private sector for use that benefits the public interest. Such reassessments are likely to lead to a larger array of better public policy innovations that generate greater benefits for society.

Some people might say that the list of federal laws and executive orders that form the core of public policy regarding university technology transfer in the United States is rather long and getting longer. These policies seem to focus predominantly on factors most relevant to supply-side actors (such as problems associated with incomplete information) and influencing the behaviour of creators and suppliers of technology (see

Table 7). They also seem to imply a narrow conceptualisation of technology as commercially valuable patentable subject matter. Consider for example the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 which allowed universities to take assignment of patents for inventions derived from federally funded research and development. The premise behind the law was that providing universities with property rights to inventions would create an economic incentive for universities to pursue the transfer of these technologies, primarily through licensing, to private sector commercial enterprises for use that benefits the public interest. However, a consequence of this public policy approach is that technologies comprising non-patentable subject matter or patentable subject matter with low perceived profit-generating potential are unlikely to be pursued regardless of whether they could improve the well-being of citizens and residents.

Table 7.

Focus of University Technology Transfer Policy.

Table 7.

Focus of University Technology Transfer Policy.

| Year |

Policy |

Policy Focus |

| 1980 |

Pub.L. 96-517Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 |

Supply-side |

| 1980 |

Pub.L. 96-480Stevenson-Wydler Technology Innovation Act of 1980 |

Supply-side |

| 1982 |

Pub.L. 97-219Small Business Innovation Development Act of 1982 |

Supply-side |

| 1984 |

Pub.L. 98-462National Cooperative Research Act of 1984 |

Demand-side |

| 1986 |

Pub.L. 99-502Federal Technology Transfer Act of 1985 |

Supply-side |

| 1987 |

Executive Order 12591Facilitating Access to Science and Technology |

Supply-side |

| 1987 |

Executive Order 12618Uniform Treatment of Federally Funded Inventions |

Supply-side |

| 1988 |

Pub.L. 100-418Ominbus Trade and Competitiveness Act |

Supply-side |

| 1989 |