1. Introduction

Topological phases of quantum systems have been at the forefront of research in condensed matter over the last two decades [

1,

2]. One of these phases takes place in quantum spin Hall (QSH) insulators, which are two-dimensional topological insulators hosting topologically protected and counter-propagating helical edge states on its boundary [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The interplay of superconductivity and the QSH effect has been widely studied in view of applications in spintronics and in (topological) quantum computation [

11,

12]. To this ends, topological Josephson junctions (JJs) appear as fundamental building blocks [

13,

14]. In a topological JJ, two superconducting electrodes are connected through the helical edge state channels of the QSH insulator. If the junction is pierced by a magnetic flux, it realizes a superconducting quantum interference setup [

11,

12,

15]. The interference pattern, namely the flux dependence of the critical current, characterizes the JJs. Despite many theoretical studies on the interference patterns, there are still open questions, particularly when it comes to comparison with experiments [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Many established models for JJs usually assume a local transmission of the Cooper pairs (CPs),

i.e. the same trajectory for both electrons [

20,

21]. A non-local transmission is also considered in the framework of edge transport via CPs’ splitting over opposite edges [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26] – allowed over length scales comparable with the superconducting coherence length

, with

the Fermi velocity and

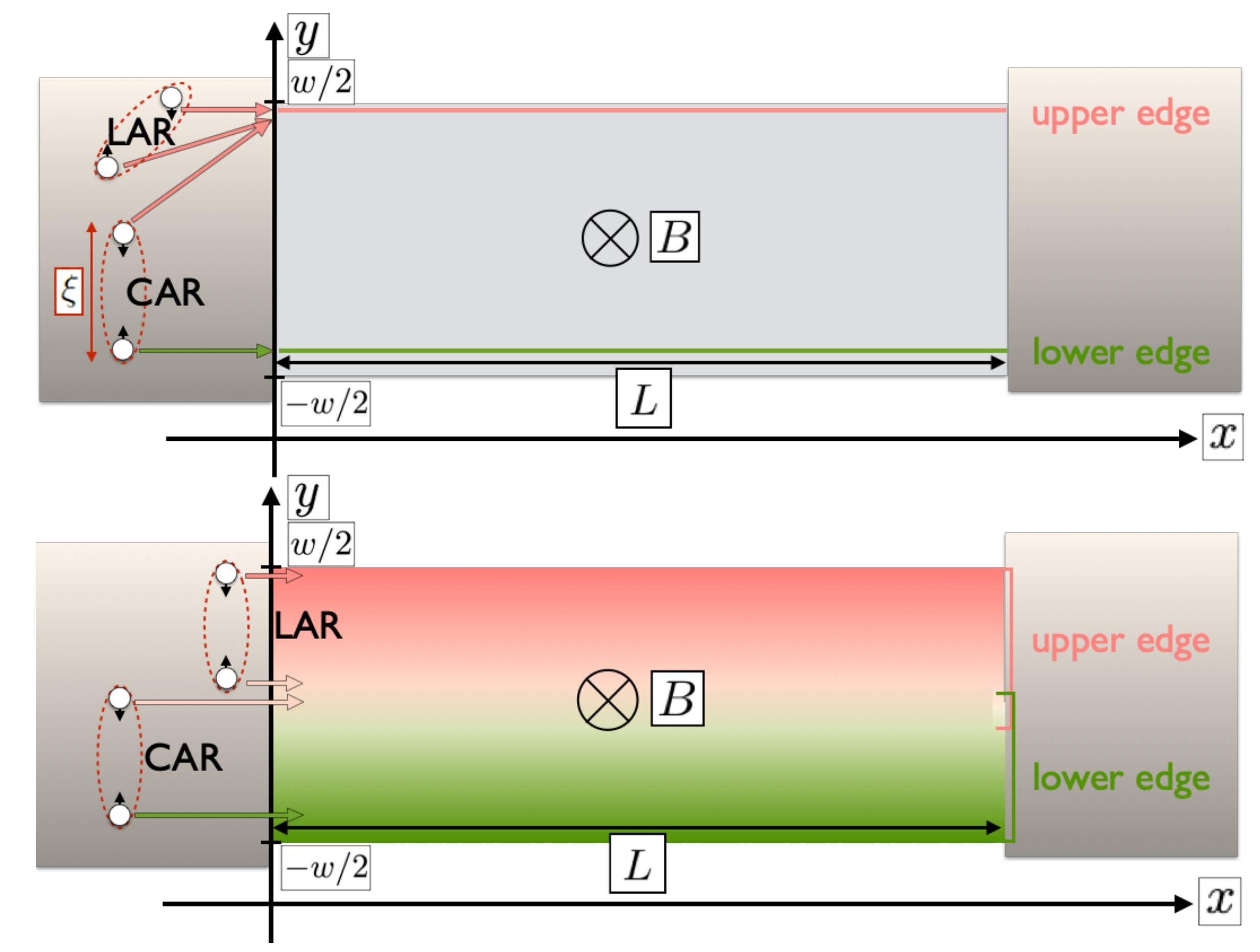

the superconducting gap – but usually in the case of narrow edge states (see the upper panel of

Figure 1). Although the scenario of extended edge states might be experimentally relevant, a theoretical model is still lacking. We address it in this article by proposing a heuristic approach. An edge state with finite spatial extension can host different trajectories for the two electrons forming the CP, provided that they are not further away from each other than

, either injected into a same edge (local Andreev reflection, LAR) or into different edges (crossed Andreev reflection, CAR), see

Figure 1. The wider the edges, the more pronounced will be the consequences on the interference pattern, which is highly sensitive to the electrons’ path.

Specifically, strongly localized edge states give rise to a sinusoidal double-slit pattern, similar to a SQUID pattern, with no decay and a period

. However, the presence of interference oscillations with a doubled periodicity has been theoretically predicted [

24,

27,

28] and experimentally observed in different setups [

27,

29], including 2DTI-based JJs. In this case, the origin of this doubling relies on the CAR processes mentioned above: a non-local transmission of electrons (whose charge quantum is

e versus the CP’s charge quantum of

) takes place [

24,

28]. Depending on the amount of CPs’ splitting, the resultant pattern features either alternating lobes with different heights or a weak cosine modulation around a constant value. On top of that, further single-electron effects leading to anomalous periodicities such as back-scattering [

30] or forward-scattering [

31] have been assessed. Lastly, we recall that a moderate spatial extent of the edge states affects the interference pattern with an overall decay in the magnetic field [

11].

In this work, we explore the combined effect of broadened edge channels, possibly overlapping, and the presence of CAR. This introduces new options for the injection process, which are absent in the case of narrow edges and which enrich the possibilities of interference patterns. Differently from previous approaches assessing 2DTI junctions, we obtain a fast side lobe decay and different oscillation periods. Within this wide phenomenology, we are interested in discussing whether CAR processes can bring along a doubled periodicity as in the case of localized edge states. We find that the answer is affirmative and identify the regime to observe such periodicity, finding that it requires a prevalence of CAR over LAR.

The article is structured as follows: In

Section 2 we review the way of calculating the Josephson current through a junction by introducing the gauge-invariant phase. We address both, local and non-local transfer of CPs. In

Section 3, we introduce our model and approach to determine the supercurrent. In

Section 4, we present and discuss our results. Finally, in

Section 5, we draw our conclusions.

2. Local and non-local transport of Cooper pairs

We consider a two-dimensional JJ of length L and width w. The intermediate region is tunnel-coupled to two superconductors on either side and for now, it is not needed to further specify its properties. A magnetic field is applied perpendicularly to the plane, . We assume that the field is screened from the superconducting electrodes, and choose the gauge , where is the vector potential.

For the evaluation of the supercurrent, it is convenient to introduce the gauge-invariant phase difference,

, with

the superconducting phase difference [

20,

32]. The gauge-invariant phase picked by a CP being transmitted across the junction along a horizontal (ballistic) path

y, with

, is then given by

Here,

labels the right/left superconducting phase and

. The second term in Equation (

1) stems for the Aharonov-Bohm contribution, which for a single electron reads as

.

Concerning the computation of supercurrents, a standard approach is the Dynes and Fulton description [

33], which holds in the tunneling regime (low-transparency interfaces) between the superconductors and their link under the assumption of the local nature of the supercurrent, flowing perpendicularly to the superconducting contacts. This means that the supercurrent density only depends on the

y coordinate while the current flows in the

x direction. In this case, for the junction just introduced, the total current is given by

with

the current density profile of the JJ. The total current hence results from a weighted integration over sinusoidal current-phase-relations (stemming from the tunneling regime). Maximizing with respect to

and getting the absolute value, one obtains the critical current or interference pattern

. This procedure recovers well-known examples of interference patterns [

21].

Non-local transmission has been previously addressed in different realizations of JJs [

27,

34,

35,

36,

37]. We are here interested in JJs featuring edge states, usually modeled as strongly localized. In these setups, a sample’s width

w comparable with the superconducting coherence length

allows an effective splitting of the CP via CAR. In this case, the Aharonov-Bohm phases acquired by the electrons propagating on opposite edges cancel, resulting in a flux-independent process. This leads to the

-periodic even-odd effect in SQUID-like patterns, which has been experimentally observed [

12,

23,

38] and theoretically addressed [

24,

26,

28] in several works. Such phenomenology is shared by helical and non-helical edge channels, though remarkable qualitative differences emerge in response to variations of the parameters [

28]. Besides the even-odd effect, it has been discussed how inter-channel scattering events give rise to anomalous flux dependencies, leading for instance to multi-periodic magnetic oscillations [

30] or to a further doubling of the period up to

[

31].

In the following, we discuss how the current can be calculated in 2D systems with extended edge states. We find different interference patterns which depend on the extension of the edge states, and on the width of the junction. The finite extension of the edge states leads to a Fraunhofer-like interference pattern, with a main central lobe and decaying side lobes. In particular, we show that, if CARs are dominant and the edge states overlap, the resulting periodicity approaches .

3. Model for extended edge channels

We model a junction as the one depicted in the lower panel of

Figure 1, consisting of a two-dimensional JJ where the weak link is a topological insulator sample of length

L and width

w. This region is tunnel-coupled to the right and left superconductors. As previously, we denote as

the phases of the right/left superconductors. Due to the proximity effect, in the superconducting parts the edge states are gapped out. In the center region, the edge states are helical. In

Figure 1, each boundary hosts two counter-propagating channels with identical profile. For clarity, only one colored shape per boundary is shown.

Following the line of reasoning in the previous section, we write a phenomenological expression for the supercurrent which generalizes Equation (

2) with two different coordinates for the two electrons:

where the fundamental ingredient is

, the weight function for the supercurrent, and

label the horizontal trajectories of the two electrons of the CP,

denoting the spin projection.

1 The function

parametrizes how each specific path contributes to the total supercurrent and encodes physical properties of the normal region, such as the supercurrent density profile, the number of transport channels and the helical nature of the junction. If the size of the CP is comparable with the junction’s width, the CP can be split into the two edges. Since we consider here broadened edge states, we assume that the CP can also be split into different trajectories within the same edge. To do so, we include an overall constraint function to take into account the CP’s extent. We hence make the following ansatz

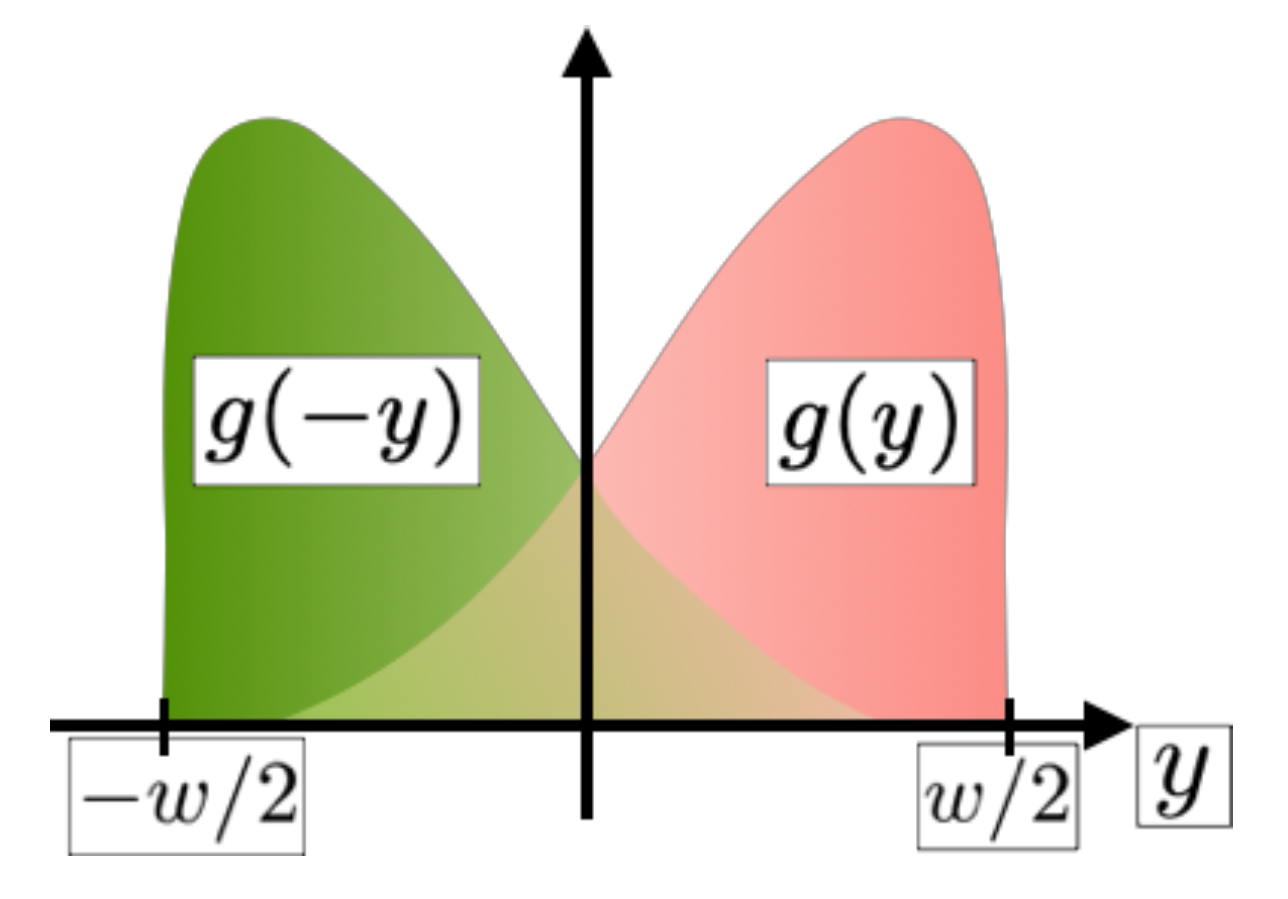

where

describes the spatial extension of the upper/lower edge state, which we assume to be symmetric around

(see

Figure 2 for a schematic view). Since

j is a probability density, we argue that

, where

is the wavefunction of the upper/lower edge state. Our approach allows us to identify the CAR and LAR processes generalized to the case of extended edge states, as marked in Equation (

4). There are two parameters to be discussed in the following: the coherence length

and the ratio of the amplitudes of LAR and CAR processes, denoted by

s. Indeed, due to helicity, LAR and CAR are clearly different processes. Since we do not consider spin-flips, in the LAR case, spin-up and spin-down electrons have opposite directions of propagation. By contrast, in the CAR case, they are either right-movers or left-movers [

28,

31].

Equations (

3)-(

4) show two main features: (1) the electrons can tunnel into the same edge but at different positions; (2) the electrons can tunnel into different edges acquiring Aharonov-Bohm phases that do not cancel each other. The latter implies the unconventional possibility of flux-dependent CAR processes.

We can check some limiting cases of Eqs. (

3)-(

4). Firstly, as to LAR, we notice that they recover the Dynes and Fulton approach for

[

33]. We can rewrite

, where the first fraction takes values between 0 and 1. Then

and the current density vanishes unless

. In this case

and the supercurrent recovers the form

which is the Dynes and Fulton description in Equation (

2). On the other hand, if

and

The integrals over

and

factorize

corresponding to completely independent trajectories.

Regarding CAR, if the conduction can only happen on narrow edges (such as in the upper panel of

Figure 1), then

, which results in a flux-independent contribution to the critical current, as expected.

We do not specify the dependence of

s on temperature, bias or length of the junction. Instead, we treat it as a phenomenological parameter. Our next aim is to identify a parameter regime, where the interference pattern is

-periodic. Indeed, being the doubled periodicity a widely studied signature, it is interesting to investigate new mechanisms that can give rise to it. We have discussed that it usually emerges in the presence of Cooper pair splitting, which is a main feature of our description of broadened edge states. We hence expect it to arise in our system. It turns out that, in our model, CAR-dominated transport is required to obtain this unusual periodicity of the maximal critical current. We hence assume

from now on.

2 Notably, it has been experimentally revealed in InSb JJs [

23] that CAR processes are larger than expected and increase at a lower temperature. It is interesting to identify rather general conditions under which CAR processes are more important than LAR processes but this analysis goes beyond the scope of the present work.

So far we have constructed a formula that generalizes the computation of a supercurrent given the current density to the case of extended edges and shown that it recovers the expected limiting cases. In the next section, we show that, in an appropriate parameter range and for wide edge states, our model features an interference pattern approaching a -Fraunhofer pattern.

4. Results and discussion

Here we analyze the interference pattern of the JJ discussing the role of the edges’ profile

and the two parameters

and

s. Given Equation (

3), the pattern reads

with

from Equation (

4).

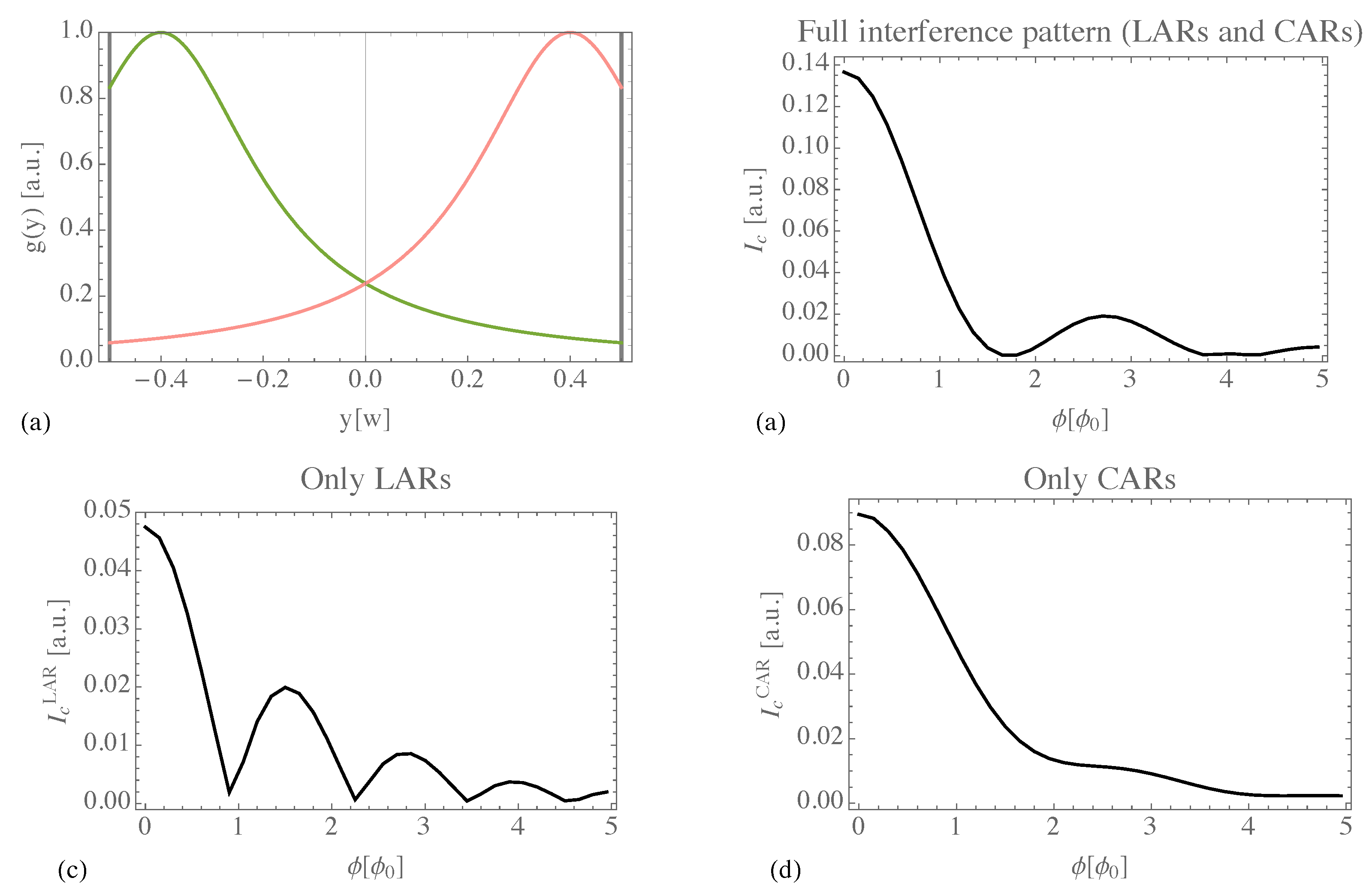

Figure 3 illustrates our results. We assume the edge profile depicted in panel (a),

and

. In

Figure 3(b), we show the total interference pattern: it exhibits minima approaching multiples of

and a fast decay. In panels (c)-(d) we plot the LAR contribution and the CAR term (

) alone, respectively, in order to point out the essential interplay of the two processes. On the one hand, the LAR pattern qualitatively resembles a standard Fraunhofer pattern, although its minima are shifted away from

-multiples as a consequence of the spatial extent of the edges. On the other hand, CAR processes feature a strong decay with a mild

-modulation on top. The

-oscillatory behavior in

Figure 3(b) results from the interaction of these two terms.

In the

Appendix A, we discuss the robustness of the effect by providing plots of the interference pattern for different values of the parameters. From such analysis, we can infer the optimal parameter range for the doubled minima periodicity, which is summarized as follows. A high coherence length

(

) is necessary because short values of

suppress the occurrence of CARs. This first requirement depends on the choice of the superconductors and on the sample width, and is not hard to fulfill. The ratio

s has to be low (at least

), which means that CARs are dominant over LARs. A significant overlap of the edge states is needed. Indeed, it can be shown that, if the edge states do not overlap, the full interference pattern exhibits the features expected for perfectly localized edges: it is a SQUID-like pattern with the additional even-odd effect, which is overall

-periodic but not decaying.

5. Conclusions

We have provided a way of computing the supercurrent across a helical Josephson junction which generalizes the previous theoretical approaches by assuming spatially extended edge states. We have presented a heuristic expression that allows for a simple calculation of the Josephson current as a function of the magnetic flux through the junction. We have argued how, as a consequence of their spatial extension, the edge states can host different trajectories for the two electrons.

We have analyzed the role played by LAR and CAR processes in determining the interference pattern. Their periodicity may vary from to , depending on the dominating process. In particular, we identify the cause for the doubled periodicity with the non-local transport arrangement. In our case, such non-locality is allowed by the extent of the edges. More specifically, the effects we predict are relevant when the two electrons within a pair can separately explore the two edges and the latter are widely broadened through the junction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Alessio Calzona, Niccolò Traverso Ziani and Björn Trauzettel; Investigation, Lucia Vigliotti and Alessio Calzona; Validation, Lucia Vigliotti, Alessio Calzona, Niccolò Traverso Ziani, F. Sebastian Bergeret, Maura Sassetti and Björn Trauzettel; Writing – original draft, Lucia Vigliotti; Writing – review & editing, Lucia Vigliotti, Alessio Calzona, Niccolò Traverso Ziani, F. Sebastian Bergeret, Maura Sassetti and Björn Trauzettel.

Funding

This work was supported by the “Dipartimento di Eccellenza MIUR 2018–2022” and the funding of the European Union-NextGenerationEU through the “Understanding even-odd criticality’’ project, in the framework of the Curiosity Driven Grant 2021 of the University of Genova. This work was further supported by the Würzburg-Dresden Cluster of Excellence ct.qmat, EXC2147, project-id 390858490, and the DFG (SFB 1170). We also thank the Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, Regional Development and Energy for financial support within the High-Tech Agenda Project “Bausteine für das Quanten Computing auf Basis topologischer Materialen”. The work of F.S.B. was partially supported by the Spanish AEI through project PID2020-114252GB-I00 (SPIRIT), the Basque Government through grant IT-1591-22, and IKUR strategy program. F.S.B acknowledges the A. v. Humboldt Foundation for funding, and Prof. Trauzettel for the kind hospitality during his stay at Würzburg University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| JJ |

Josephson junction |

| 2DTI |

two-dimensional topological insulator |

| CP |

Cooper pair |

| SQUID |

superconducting quantum interference device |

| CAR |

crossed Andreev reflection |

| QSH |

quantum spin Hall |

| LAR |

local Andreev reflection |

Appendix A. General discussion

We provide here a more general discussion, commenting on the interference pattern we obtain for a wider range of parameters. This allows us to substantiate the optimal ranges we stated in the main text.

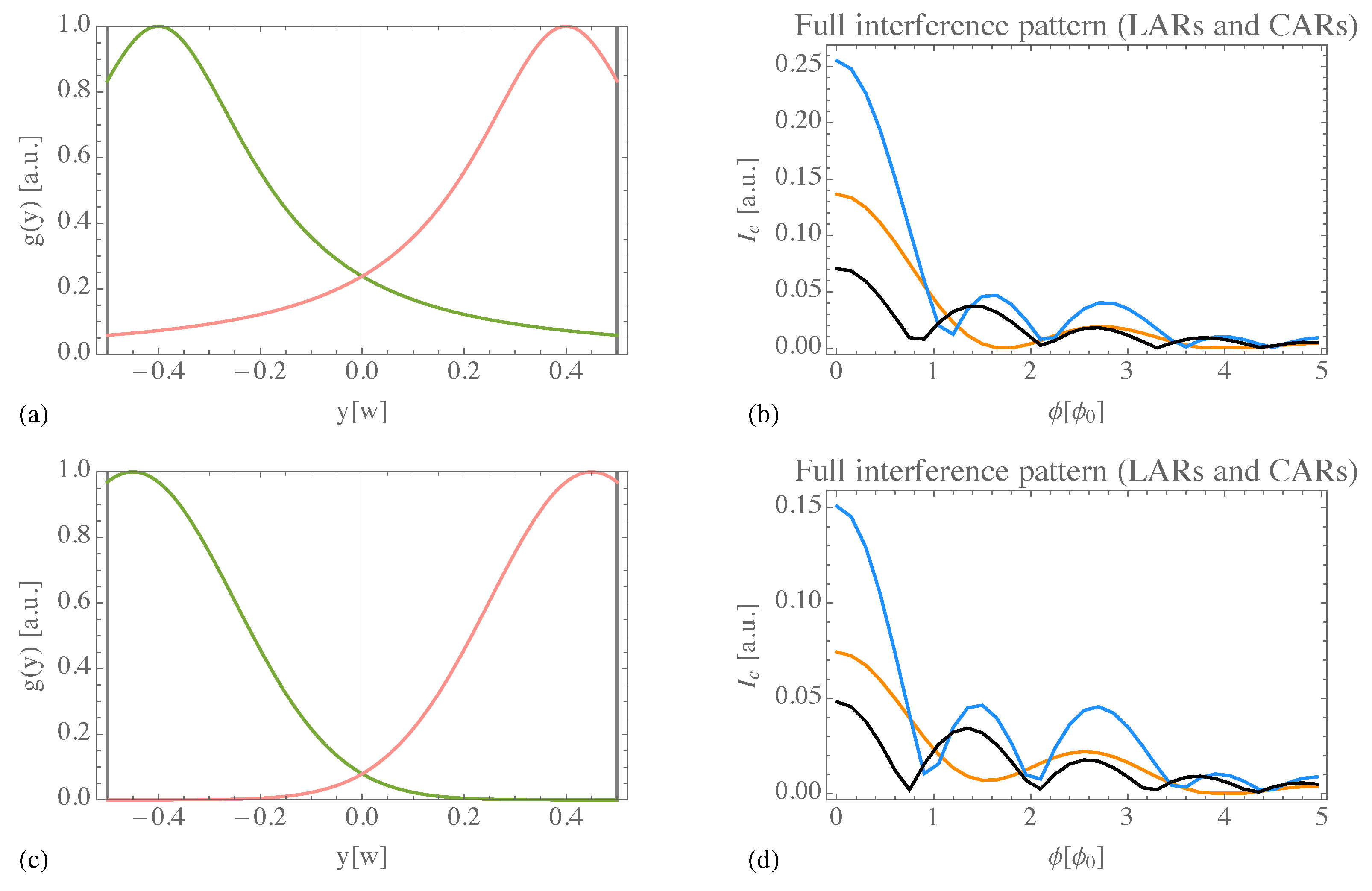

In

Figure A1, we take into consideration two different shapes for the edge states, which we plot in the first column (the upper edge in pink, the lower one in green). They are both peaked at the opposite ends of the junction, around

, but feature a decreasing overlap from the top row to the bottom row. In the second column, we plot the full interference pattern arising from both LAR and CAR. Each colored line corresponds to a different combination of

and

s, given the edge profile.

The functional forms we use for the edge shape are the following.

3

Let us start from the first row, where the same edge shape as in the main text is considered. In panel (b), the orange curve is the one presented in

Section 4, with a high coherence length and a prominent presence of CAR. We use it here as a reference plot.

The black curve shows the opposite regime, where CAR is almost missing. Due to , we fall back into the Dynes and Fulton description, with the interference pattern approaching the one of a supercurrent density . This tends to give rise to a standard Fraunhofer-like pattern, with more minima. If s is decreased, also LAR is suppressed and the entire pattern is lowered.

Increasing the coherence length, we enhance the possibility of a nonlocal propagation of the two electrons, but it is not sufficient to get a well visible -periodicity. A LAR-dominated scenario (a weak suppression ), despite high coherence lengths, still leads to a Fraunhofer-like behaviour with more minima and a slower decay (light blue curve). This pinpoints the additional demand for a prominent presence of CAR (small s, at least ).

The second row allows to discuss the importance of the overlap of edge states, which is quite small in panel (c). Tuning the parameters as in the black and light blue curves gives a result similar to panel (b). This is expected to be the case, since we already commented they are not in the appropriate parameter regime. Hence, a more or less pronounced overlap becomes irrelevant. However, using the optimal parameters (orange curve), the periodicity just starts to approach , but the minima are shallow. This shows the need for highly extended states to see the -periodicity.

Figure A1.

Flux-dependence of the critical supercurrent considering different values of coherence length, a more or less prevalent role played by LARs and CARs (represented by the parameter s), and different profiles for the edge states. In each row, the first panel ((a), (c)) shows such profile and the symmetric . In the second column (panels (b), (d)), we plot the full interference pattern arising from both LARs and CARs. Different colors are associated with different values of and s, see the plot legend.

Figure A1.

Flux-dependence of the critical supercurrent considering different values of coherence length, a more or less prevalent role played by LARs and CARs (represented by the parameter s), and different profiles for the edge states. In each row, the first panel ((a), (c)) shows such profile and the symmetric . In the second column (panels (b), (d)), we plot the full interference pattern arising from both LARs and CARs. Different colors are associated with different values of and s, see the plot legend.

References

- Hasan, M. Z.; Kane, C. L. Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.-L.; Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2011, 83, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcetto, G.; Sassetti, M.; Schmidt, T. L. Edge physics in two-dimensional topological insulators. Riv. Nuovo Cim. 2016, 39, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Bernevig, B. A.; Hughes, T. L.; Zhang, S.-C. Quantum Spin Hall Effect and Topological Phase Transition in HgTe Quantum Wells. Science 2006, 314, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strunz, J.; Wiedenmann, J.; Fleckenstein, C.; Lunczer, L.; Beugeling, W.; Müller, V. L.; Shekhar, P.; Traverso Ziani, N.; Shamim, S.; Kleinlein, J.; Buhmann, H.; Trauzettel, B.; Molenkamp, L. W. Interacting topological edge channels. Nat. Phys. 2020, 16, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, M.; Wiedmann, S.; Brüne, C.; Roth, A.; Buhmann, H.; Molenkamp, L. W.; Qi, X.-L.; Zhang, S.-C. Quantum Spin Hall Insulator State in HgTe Quantum Wells. Science 2007, 318, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knez, I.; Du, R.-R.; Sullivan, G. Evidence for Helical Edge Modes in Inverted InAs/GaSb Quantum Wells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 136603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, F.; Li, G.; Dudy, L.; Bauernfeind, M.; Glass, S.; Hanke, W.; Thomale, R.; Schäfer, J.; Claessen, R. Bismuthene on a SiC substrate: A candidate for a high-temperature quantum spin Hall material. Science 2017, 357, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Fatemi, V.; Gibson, Q. D.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Cava, R. J.; Jarillo-Herrero, P. Observation of the quantum spin Hall effect up to 100 kelvin in a monolayer crystal. Science 2018, 359, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hughes, T. L.; Qi, X.-L.; Wang, K.; Zhang, S.-C. Quantum Spin Hall Effect in Inverted Type-II Semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 236601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.; Ren, H.; Wagner, T.; Leubner, P.; Mühlbauer, M.; Brüne, C.; Buhmann, H.; Molenkamp, L. W.; Yacoby, A. Induced superconductivity in the quantum spin Hall edge. Nat. Phys. 2014, 10, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribiag, V. S.; Beukman, A. J. A.; Qu, F.; Cassidy, M. C.; Charpentier, C.; Wegscheider, W.; Kouwenhoven, L. P. Edge-mode superconductivity in a two-dimensional topological insulator. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015, 10, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deacon, R. S.; Wiedenmann, J.; Bocquillon, E.; Domínguez, F.; Klapwijk, T. M.; Leubner, P.; Brüne, C.; Hankiewicz, E. M.; Tarucha, S.; Ishibashi, K.; Buhmann, H.; Molenkamp, L. W. Josephson Radiation from Gapless Andreev Bound States in HgTe-Based Topological Junctions. Phys. Rev. X 2017, 7, 021011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcini, F.; Houzet, M.; Meyer, J. S. Topological Josephson ϕ0 junctions. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 035428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocquillon, E.; Deacon, R. S.; Wiedenmann, J.; Leubner, P.; Klapwijk, T. M.; Brüne, C.; Ishibashi, K.; Buhmann, H.; Molenkamp, L. W. Gapless Andreev bound states in the quantum spin Hall insulator HgTe. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, C. T.; Draelos, A. W.; Seredinski, A.; Wei, M. T.; Li, H.; Hernandez-Rivera, M.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Tarucha, S.; Bomze, Y.; Borzenets, I. V.; Amet, F.; Finkelstein, G. Anomalous periodicity of magnetic interference patterns in encapsulated graphene Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Res. 2019, 1, 033084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suominen, H. J.; Danon, J.; Kjaergaard, M.; Flensberg, K.; Shabani, J.; Palmstrøm, C. J.; Nichele, F.; Marcus, C. M. Anomalous Fraunhofer interference in epitaxial superconductor-semiconductor Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95, 035307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurter, C.; Finck, A. D. K.; Hor, Y. S.; Van Harlingen, D. J. Evidence for an anomalous current–phase relation in topological insulator Josephson junctions. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börcsök, B.; Komori, S.; Buzdin, A. I.; Robinson, J. W. A. Fraunhofer patterns in magnetic Josephson junctions with non-uniform magnetic susceptibility. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkham, M. Introduction to Superconductivity; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, A.; Paternò, G. Physics and Applications of the Josephson Effect, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 1982.

- Sato, K.; Loss, D.; Tserkovnyak, Y. Cooper-Pair Injection into Quantum Spin Hall Insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 226401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, F. K.; Sol, M. L.; Gazibegovic, S.; op het Veld, R. L. M.; Balk, S. C.; Car, D.; Bakkers, E. P. A. M.; Kouwenhoven, L. P.; Shen, J. Crossed Andreev reflection in InSb flake Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Research 2019, 1, 032031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxevanis, B.; Ostroukh, V. P.; Beenakker, C. W. J. Even-odd flux quanta effect in the Fraunhofer oscillations of an edge-channel Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 041409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recher, P.; Loss, D. Superconductor coupled to two Luttinger liquids as an entangler for electron spins. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 65, 165327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, G.; Taddei, F.; Giovannetti, V.; Braggio, A. Manipulation of Cooper pair entanglement in hybrid topological Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 064514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heida, J. P.; van Wees, B. J.; Klapwijk, T. M.; Borghs, G. Nonlocal supercurrent in mesoscopic Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 57, R5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidekker Galambos, T.; Hoffman, S.; Recher, P.; Klinovaja, J.; Loss, D. Superconducting Quantum Interference in Edge State Josephson Junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 157701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, Y.; Jensen, S.; Akazaki, T.; Takayanagi, H. Anomalous magnetic flux periodicity of supercurrent in mesoscopic SNS Josephson junctions. Physica C: Superconductivity 2002, 367, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironov, S. V.; Mel’nikov, A. S.; Buzdin, A. I. Double Path Interference and Magnetic Oscillations in Cooper Pair Transport through a Single Nanowire. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 227001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigliotti, L.; Calzona, A.; Trauzettel, B.; Sassetti, M.; Traverso Ziani, N. Anomalous flux periodicity in proximitised quantum spin Hall constrictions. New J. Phys. 2022, 24, 053017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachov, G.; Burset, P.; Trauzettel, B.; Hankiewicz, E. M. Quantum interference of edge supercurrents in a two-dimensional topological insulator. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 045408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynes, R. C.; Fulton, T. A. Supercurrent Density Distribution in Josephson Junctions. Phys. Rev. B 1971, 3, 3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzykin, V.; Zagoskin, A. M. Coherent transport and nonlocality in mesoscopic SNS junctions: anomalous magnetic interference patterns. Superlatt. Microstruct. 1999, 25, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledermann, U.; Fauchère, A. L.; Blatter, G. Nonlocality in mesoscopic Josephson junctions with strip geometry. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, R9027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehy, D. E.; Zagoskin, A. M. Theory of anomalous magnetic interference pattern in mesoscopic superconducting/normal/superconducting Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68, 144514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.-H.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Lee, G.-H.; Lee, H.-J. Engineering Crossed Andreev Reflection in Double-Bilayer Graphene. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, F. K.; Timmerman, T.; Ostroukh, V. P.; van Veen, J.; Beukman, A. J. A.; Qu, F.; Wimmer, M.; Nguyen, B.-M.; Kiselev, A. A.; Yi, W.; Sokolich, M.; Manfra, M. J.; Marcus, C. M.; Kouwenhoven, L. P. h/e Superconducting Quantum Interference through Trivial Edge States in InAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 047702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

For now, we neither include diagonal trajectories nor any inter-edge tunneling. |

| 2 |

Notice that one of the two CAR contributions should be proportional to . Since , we will neglect it and work up to the first order in s. |

| 3 |

Fine details about the functional form describing the edge profile are not crucial. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).