1. Introduction

A Michigan State University study has found that traditionally produced food in the USA is transported to an average distance of almost 1,500 miles before it arrives in supermarket shelves (Henne 2012). This has many implications including unnecessary extra cost of food, carbon emission, deterioration of freshness of food, and potential for supply disruption due to inclement weather, pandemics, road closures, strikes, and other causes. For an industrial market economy, such a supply chain is necessary at the present time. However, as discussed in this paper, practice of urban agriculture can avoid some of these problems.

Of the eight billion people on earth in 2022, more than 55 percent are already living in urban areas. The urban population is expected to exceed 75 percent of the total global population by 2050. To feed these many people, theoretically, a cultivation area equal to that of the South American continent is needed. In addition, a farming area almost the size of Africa is needed for all the animals needed by human beings for food and service. This will require bringing almost 57 percent of the total earth’s surface under habitation. Unfortunately, as almost 57 percent of the earth’s land surface is unhabitable, human activities must be limited to 43 percent of the total land surface. Within that 43 percent area, all types of land use such as roads, buildings, and various recreational activities must be accommodated. Currently, of the global land surface, urban areas occupy between one to three percent of the total land area. Concentrating the urban population that would reach 75 percent of the total population by 2050, within 1-3 percent of urban areas means that urban planning has to become smarter than it is today.

The traditional agricultural sector has become a polluting, water intense, and ecologically damaging industry. Urban agriculture (or farming) could help to offset some of this pollution by shifting at least some of the agricultural production to the urban farms. Urban agriculture can also alleviate the pressure caused by the unending need to expand farmlands to feed the growing population. It will also help in reducing the prevalence of diseases that are often associated with the food that is processed and transported over long distances. Further, a public-private partnership in supporting the production and commercialization of urban agriculture production will help make the urban farming process more efficient and productive. Urban farming helps in efficiently bringing back atmospheric carbon into soils through phytotechnology, which are “plant-based technologies to clean water, soil, air and provide ecosystem services including energy from biomass.” (IPS, 2014: p2).

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. First, it explains what urban farming is. Second, it discusses the theory of urban farming. Third, it provides the background of the study including data and information about Nepali urban development. Fourth, it provides some comparative studies of crop production between traditional farming and urban farming along with estimates of cost and production, and avoidance of carbon emission in the case of Nepal. This is followed by discussions in the fifth section. Then the paper concludes with some recommendations.

2. What Is Urban Agriculture?

Urban agriculture (UA), sometimes also known as urban farming, is the practice of growing food within urban areas for personal consumption or small-scale commercial purposes. It consists of growing fruits and vegetables, and sometimes raising small animals on-site in residential units and sites for household consumption and for supply into the local markets.

Urban agriculture (UA) is an old practice that has existed since the birth of cities. However, more recently, in the dense and often high-rise-filled modern cities, urban agriculture did not find many practitioners. With the environmental concerns related to transporting foods over long distances often with their freshness compromised, and after the experience of pandemics such as Covid-19, urban dwellers are increasingly realizing that handy access to freshly grown food on site is an important backup for food supply in the urban areas.

Kimberley Hodgson, Campbell and Bailkey (2011) define urban agriculture as entailing:

“… the production of food for personal consumption, education, donation, or sale and includes associated physical and organizational infrastructure, policies, and programs within urban, suburban, and rural built environments. From community and school gardens in small rural towns and commercial farms in first-ring suburbs to rooftop gardens and bee-keeping operations in built-out cities, urban agriculture exists in multiple forms and for multiple purposes (p. 2).”

Urban agriculture implies the growing and marketing (when applicable) of food in urban areas. Urban agriculture often takes place in community gardens, building balconies and rooftops, home backyards, and sometimes in vertical structures. This is seen as supporting food security, and promoting individual productivity, community building and environmental and economic sustainability. Urban farming may take the forms of traditional agriculture, hydroponics, aquaponics, vertical farming, and animal raising in space-efficient systems.

Urban agriculture production is typically located on rooftops, balconies, windowsills, indoor, front, back, and side yards of residential units. The production techniques may include normal planting, vase planting, hydroponics, aeroponics, and vertical farms that produce fruits, vegetables, eggs, and meat from small animals. It includes private edible gardens, community and institutional gardens, as well as edible landscape in public areas such as on parks, road medians, sidewalks, and plazas. Urban farming produce are mostly for private consumption, but can also be for commercial purposes. Hodgson, Campbell and Bailkey (2011: 20) find that “Urban agriculture helps meet local food needs while promoting environmental sustainability, health, nutrition, and social interaction; creating opportunities for locally controlled food enterprises and economic development; and enhancing community engagement and empowerment”.

Urban agriculture provides city and community various benefits related to supplemental income or saving on food costs for families, helping to improve health from the consumption of fresh foods, preserving urban environments, improving community cohesion, reducing the transportation of food, and enhancing the overall sustainability of urban developments. Urban agriculture practices can offset carbon emissions, and save households food-related expenses (see authors’ example estimates for Nepal in this paper).

There are also some risks and challenges associated with urban agriculture practices. Examples: smell from compost, flies and worms from soil and plants, and space use conflicts with other uses. Neighbor’s concerns with urban animal raising can be another area of conflict. However, in average, urban agriculture can positively contribute towards a healthy, resilient community, when combined with good planning strategies.

3. Theory of Urban Farming

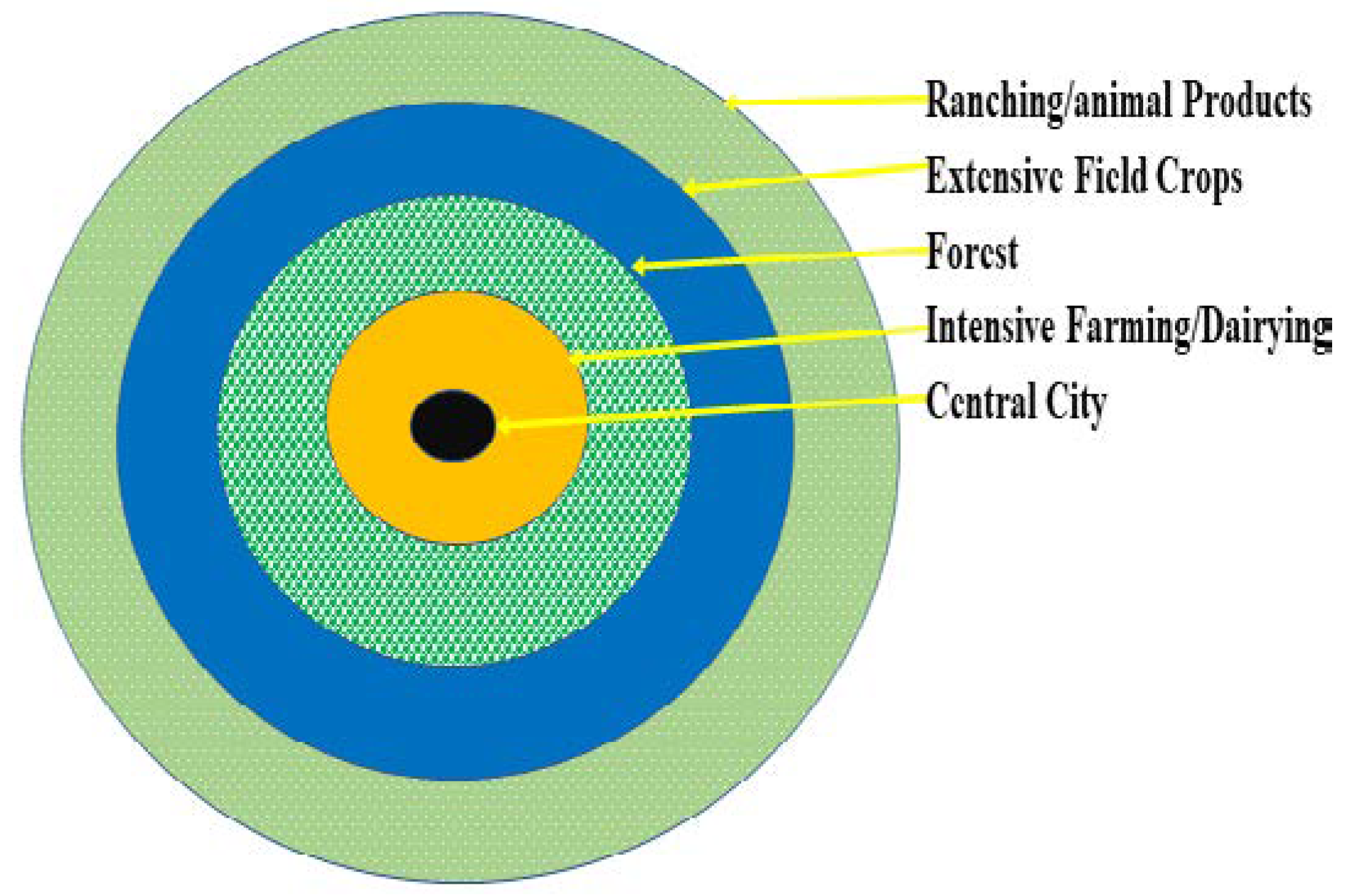

First settlements on the earth started in areas with fertile plains. Such settlements emerged as urban centers, where people from peri-urban areas and remote villages used to have farmers’ markets organized on a regular basis. However, those traditions were not enough to meet the requirements of a large urban population. After the harvest, many agricultural products quickly perished, and they needed to be transported to the consumption sites quickly. Since there were no good transportation networks, many products decayed during their long transit. To solve this problem, a German Economist and agriculture planner J. H. Von Thunen (1783-1850) in 1826, using the example of Chicago, argued that city should be located centrally within an “Isolated State” (

Figure 1).

Since the typical isolated state was surrounded by “unoccupied wilderness”, especially, in a place or food desert, farmers needed to grow agricultural crops and dairy products nearby urban areas because agricultural products perish while ferrying from the production site to the often distant urban centers. This was a situation when refrigerated trucks were not developed. Farmers largely grew their own food, such as dairy products, fruits, vegetable, eggs, and meat and consumed them fresh. However, the situation has changed in the last several decades with the development of trucks with refrigerated containers. The long-distance hauling facilities offered by such trucks have made it possible to transport perishable food products over long distances with less damage to the food. However, long distance food transportation process can cause several environmental problems.

First, transporting food increase emissions of various toxic gases. Additionally, the packing and unpacking of food have increased the use of plastic, tin, metal, and paper. Production of these materials contribute to 14 to 17 percent of global anthropogenic emissions (Maraseni and Qu 2016). The production, packaging, storage, and transportation of agricultural farm products contribute additional greenhouse gas emission (GHG), which at present accounts for 3 to 6 percent of the total emissions globally (Vermuelen et al. 2012).

Second, when food is transported long distances, a significant portion of food is still wasted. Globally, one third of all the food produced is wasted with almost 1.6 billion tons of food is spoiled on the way to the market or expired on storage and simply thrown away (Quinton, 2019). Every year, over 600 million people get sick eating contaminated food (WHO, 2022). Additionally, such long hauling also increases the cost of food. The supply chain can be disrupted for many reasons such as labor issues, road conditions, inclement weather, availability of fuel, political unrest, and pandemics such as Covid-19.

It is useful to capture atmospheric carbon using carbon sequestration in urban areas too, i.e., trapping carbon by plants to convert it into plant food, biomass, and fruits. Plants can sequester carbon and increase net primary productivity (NPP) per unit area eventually increasing the gross primary productivity (GPP) (De Lucia et al., 2007) of an urban area. Atmospheric carbon can be stored on plant bodies that contribute to plant growth. For instance, a 0.4 carbon use efficiency (CUE) indicates that 40 percent of the carbon acquired by plants is taken up for the growth and storage of biomass. CUE of a plant can be measured through biomass (Bradford and Crowther, 2013; Roxburgh et al., 2005) and the total growth of a plant over an urban area can be converted into GPP (Ballantyne et al., 2012). It provides a better understanding of the energy exchange among vegetation and atmosphere by estimating the CUE of a plant, and vegetation carbon dynamics (VCD). A phytotherapy process helps to trap many anthropogenic drivers originating from different sources in the urban environment. These analyses shed some light on the rate of carbon allocation and help to accurately quantify the ability of vegetation to convert carbon to new biomass in urban ecosystems. Furthermore, the CUE assessment would provide new insights into vegetation carbon allocation at regional and global scales. Accurate quantification of CUE for various vegetation types would enhance the performance of earth system-related models. Since urban farming is done on a smaller scale, it helps to precisely quantify CUE and assess VCD for an urban area. VCD is a measure of the rapid increase in the atmospheric concentration of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. Assessing VCD can help to measure of the productivity of various plants (Zwart and Brighenti, 2021).

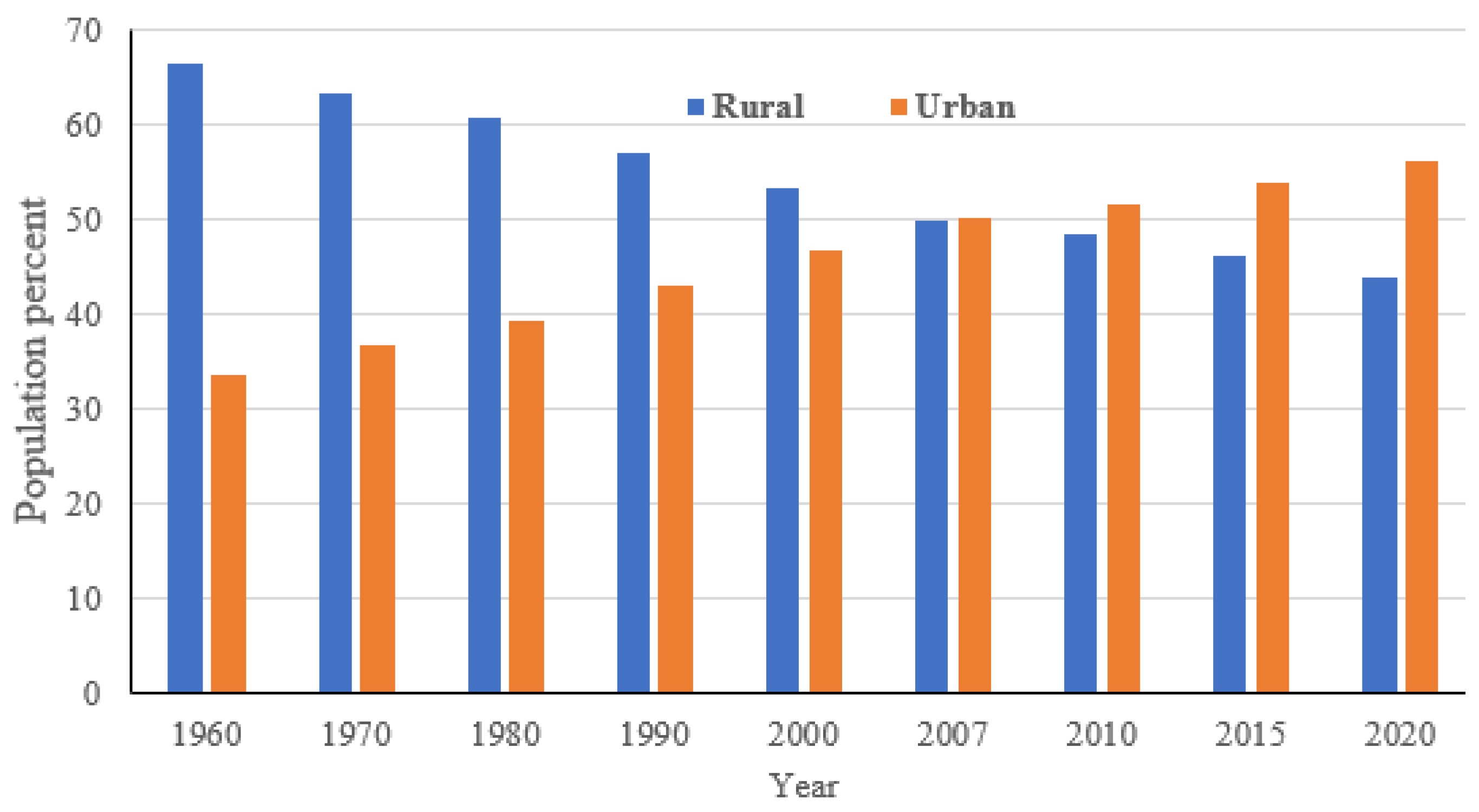

Of the 29 percent global terrestrial land surface, 71 per cent is habitable. Of the 71 percent, 33 percent is arable, and one percent is under urban land uses (FAO, 2011). A major portion of population is living in smaller urban areas. Since 2007, the percentage of the urban population has exceeded the rural population (

Figure 2) with 3.35 billion as urban against the 3.33 rural population. The growing urban residents have to concentrate their activities in even smaller areas (Our World in Data, 2021).

The rapid growth of urban population has increased food insecurity in cities, and it has overstretched the supply chain, especially, at the time of crisis such as the Covid-19 pandemic. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) predicts that compared to 2022, global food demand will increase by 70 percent by 2050. This will put pressure on the already scarce land and water resources. This also means that there is an urgent need for alternative approaches to address possible urban food shortages.

Urban agriculture has the potential to provide hundreds of millions of people with safe and easy access to food. Urban farming is a way to utilize limited land resource to produce food within urban and peri-urban areas, and supply it in response to the daily demand of consumers within a town /city. It applies intensive production methods using and reusing natural resources and organic urban wastes to yield a diversity of crops and livestock to meet urban food needs. Urban farming offers easy access to fresh and nutritious food. This process was officially recognized by the 15th FAO meeting in January 1999 and subsequently at the World Food Summit in 2002. Since then, its importance has been even more appreciated because like other service sectors and industries, urban farming provides additional employment and income opportunities for the urbanites. Urban agriculture can create a diverse ecology where fruit trees and vegetable and even fishing could coexist and build a wholly ecologically sustainable circular economy.

Since only small areas are available for farming in the cities, urban farming is often done on hardscape (pavements, sidewalks, rooftops, balconies). However, only shallow rooting plants can be planted on raised beds on hardscape. In such a hardscape, if animal manure and chemical fertilizers are used, they generate additional greenhouse gases. However, if organic compost is used, it helps sequester atmospheric carbon within the compost and plant bodies while using 70 less water. In a smaller area, vertical farming is possible using compost where every layer can sequester carbon.

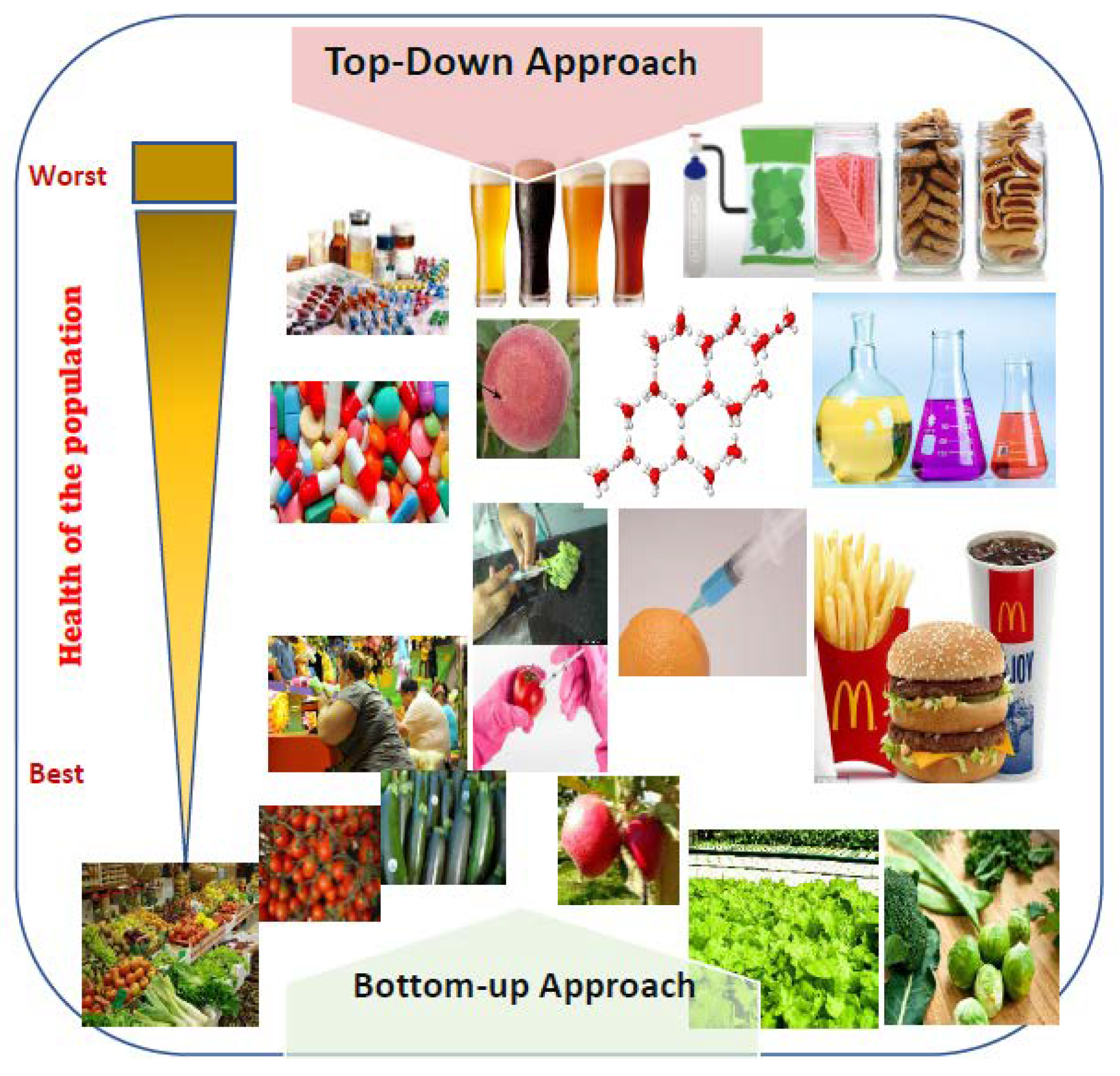

Other forms of urban farming on hardscapes include hydroponics, rooftop, and balcony, backyard, and front yard farming, community gardens, farming in the park, and parking lot farming. Except for hydroponics, compost made from the byproducts of various vegetables and other food products can be used in all types of farming that can not only efficiently sequester carbon but also becomes a healthy practice because all the products are produced locally and bottom-up as opposed to a top-down approach (

Figure 3). If the urban area has open green spaces, animal manure can be used on the ground. Planting on the open ground allows deep-rooted trees to sequester carbon to a deeper level. In such an environment using animal manure, and chemical fertilizers contribute less GHS because most of the carbon is sent back to deeper soil through the deep root system.

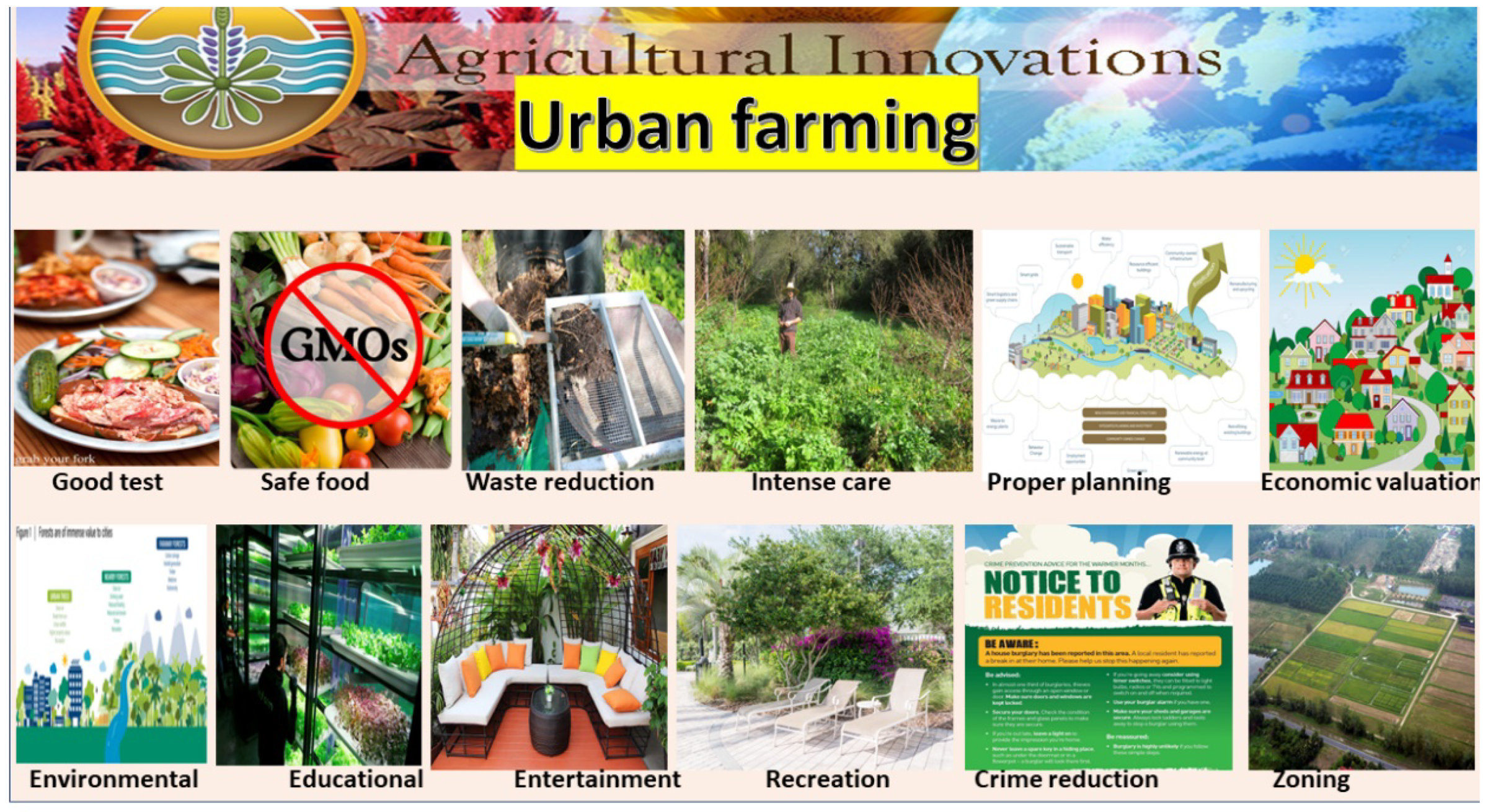

There are several benefits of urban farming. Some of the major benefits include, but are not limited, to: a) better taste of vegetable and fruit products; b) these are organic but not the genetically modified (GMO) varieties; c) helps use and reuse wastes; d) through carbon use efficiency (CPU) and vegetation carbon dynamics (VCD) the net primary productivity (NPP), and overall gross vegetation product (GPP); e) uniting communities, close monitoring of production system; f) educational exhibition; and g) crime reduction through the involvement of unemployed youths to some creative activities (

Figure 4).

4. Examples of Urban Farming US and Nepal

4.1. Urban Agriculture in the US

The metro Phoenix region in Arizona, USA is an urbanized region of almost 5 million people (2022). In most of the municipalities of the metro area, urban agriculture is promoted by the municipal governments for various reasons including food security, reduction in transportation needs, mitigation of the heat island effect, and self-reliance of households on food. For example, the City of Phoenix (2022) 2025 Food Action Plan states “Achievement of local food system goals results in reduced rates of hunger, obesity, and diet-related diseases through the elimination of food deserts, increasing urban agriculture and adopting zoning, land use guidelines, and other policies to improve the food system.” Similarly, the City of Tempe (2014) in Arizona in its General Plan 2040, includes a strategy to “Expand opportunity for urban agriculture – home gardens, community gardens, urban farms, farmers markets, as well as food availability and accessibility promotes urban agriculture”. Many other cities in metro Phoenix and elsewhere in Arizona have plans and programs to promote and encourage urban agriculture.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show examples of urban agriculture in metro Phoenix.

Agrotopia, a mixed use community in the burgeoning Town of Gilbert is an example of how urban agriculture could be women into the urban fabric and made it more appealing. Agrotopia provides the tour of its urban agriculture to promote the practice, and utilizes urban agriculture not only for local food production, but also to make the community more attractive for the urban residents. The juxtaposition of urban agriculture and restaurants which use the food produced there is an example of the symbiotic relationship between the urban environment and urban agriculture.

On an experimental basis, the University of Central Missouri (UCM) is growing tomatoes on a hydroponic system inside the greenhouse year-round without the need for supplemental heating and cooling systems (

Figure 7a,b). In a hydroponics system, nutrient water is circulated through the water container and plant. No soil is used, but the plants are supported by various substrates. The substrates provide some holes for air circulation. Under normal temperatures, tomato seeds start germination between 5 and 14 days. Before transplanting plants into the hydroponic system, it is necessary to put blocks into hydroponic baskets as tomatoes grow quickly.

The nutrient-rich water contains all the necessary macro and micro-nutrients required by the plants for optimum growth. The water flows from the nutrient tank through the plant system and back into the nutrient tank. The nutrient water is pumped into a trough. The water then slowly returns to the nutrient tank through a valve in the trough. Nutrient-rich water is pumped through a series of thin plastic spaghetti pipes into the buckets. The water supply should be uninterrupted.

Tomato performs better when the ambient temperature is between 21⁰ and 26⁰ C and the electrical conductivity is between 2 and 4 milli siemens.

1 The optimum water pH ranges from 6 to 6.5 works best for tomato plants. Calcium is required at the time of fruiting, and lower amounts of potassium nitrate and calcium nitrate are great hydroponic fertilizers. If the pH ranges are not ideal, this condition prevents nitrogen and calcium uptake by the root system even if they are present in the nutrient solution.

4.2. Urban Agricultural in Nepal

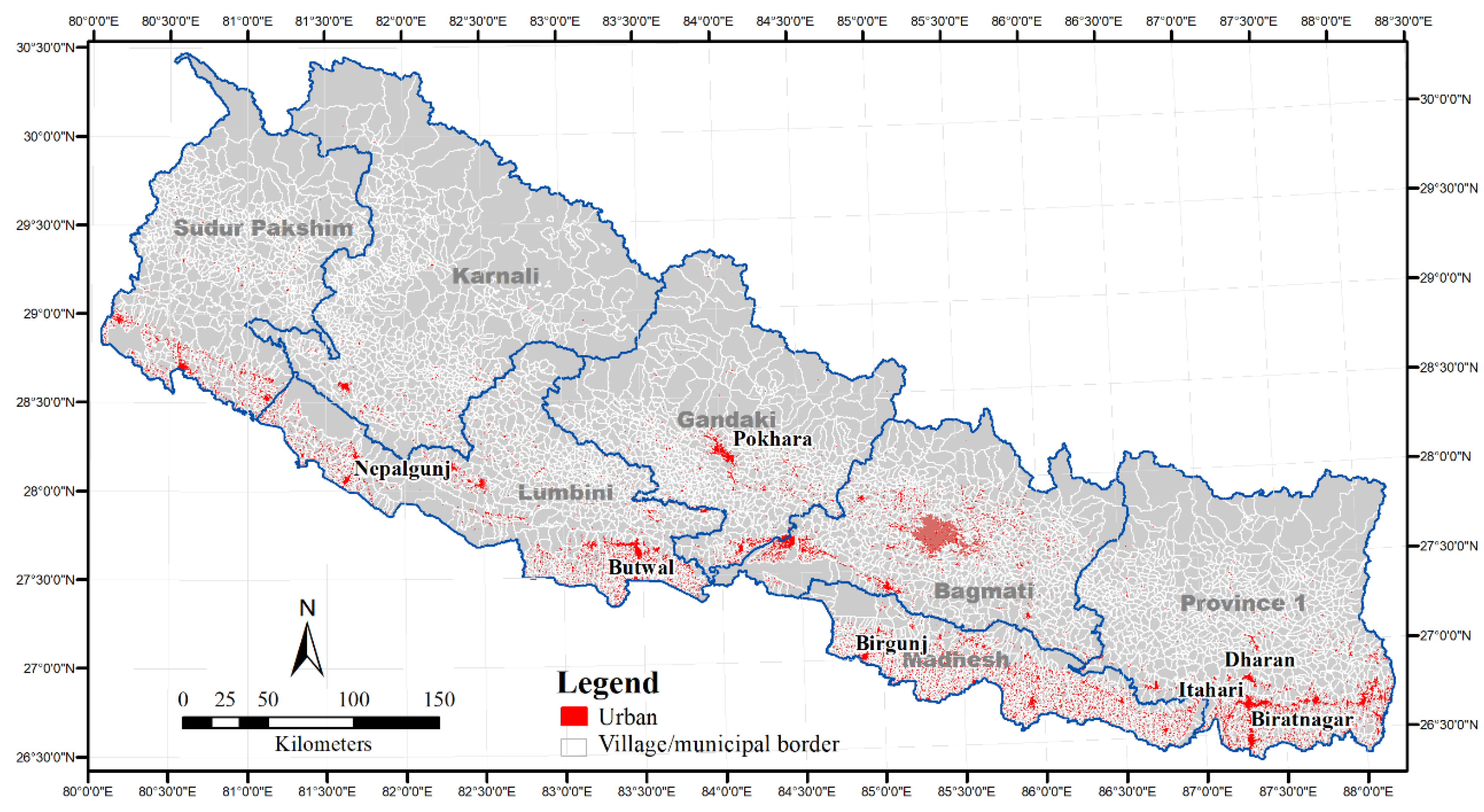

Most urban dwellers in Nepal are first-generation urbanites. Agriculture is deep-rooted in their blood. Even the highly urbanized places such as the town in the Kathmandu Valley, Pokhara, Birgunj, Biratnagar, Itahari, Dharan, and Butwal (

Figure 8) have emerged from recent agricultural places or have agricultural activities in the adjoining areas. Because of this historical nexus between urban development and farming, urban agriculture comes naturally to many of the residents in such cities.

In 2015, the UN Habitat in cooperation with the Kathmandu Municipality, European Union, and a local non-profit ENPHO published a 56-page long training manual to help the urban residents cultivate urban agriculture. The manual authored by Dr. Bharat Kumar Poudyal is called “Training Guidebook for Rooftop and Balcony Agriculture” (UN Habitat, 2015). The guidebook contains knowledge and information about the usefulness and benefits of balcony and rooftop agriculture, human needs for nutrition, the daily needs of the quantities of fruits and vegetable for an individual, best location for balcony and roof top farming, and most suitable types of plants and vegetables for urban farming. The manual also includes lessons for the suitable types of soils, compost, irrigation, trellises, good and bad insects, insect control, and the various techniques and technologies for urban agriculture.

A training workshop in Nepal conducted in cooperation with the United Nations Framework Climate Change Conventions (UNFCC) with 250 participating families found that rooftop farming can cover 50 percent of domestic vegetable consumption needs; and avoid 110 metric tons of carbon dioxide emission reductions per year (UNFCC, no date).

In Nepal, urban agriculture can help provide many benefits to the city residents including food security, food self-reliance, savings in food expenditures, and income supplement to the families. In addition, urban agriculture can help reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases and provide other environmental benefits including waste reduction and minimizing road congestion. This practice can also help to provide safeguards to counter unpredictability of food supply due to road damages, border blockades, and pandemics.

Except for a few well-established cities, most of Nepal new urban centers have just been reclassified by the government and still retain many rural characteristics. Many residents are still practicing agriculture in small tracts of land, while they have been classified as urban residents. Similarly, as urban areas grow the adjoining agricultural lands also begin to gradually join urban life. These areas are often called peri urban. Because of these differences in urban traits, the urban agriculture practice and potential will also be different in these areas. In denser and more matured urban areas, urban agriculture will mainly happen on roof-tops, balconies, and yards in the building lots. Whereas in the newly urbanizing and peri-urban areas, in addition to these locations, urban open spaces can also be used for urban farming.

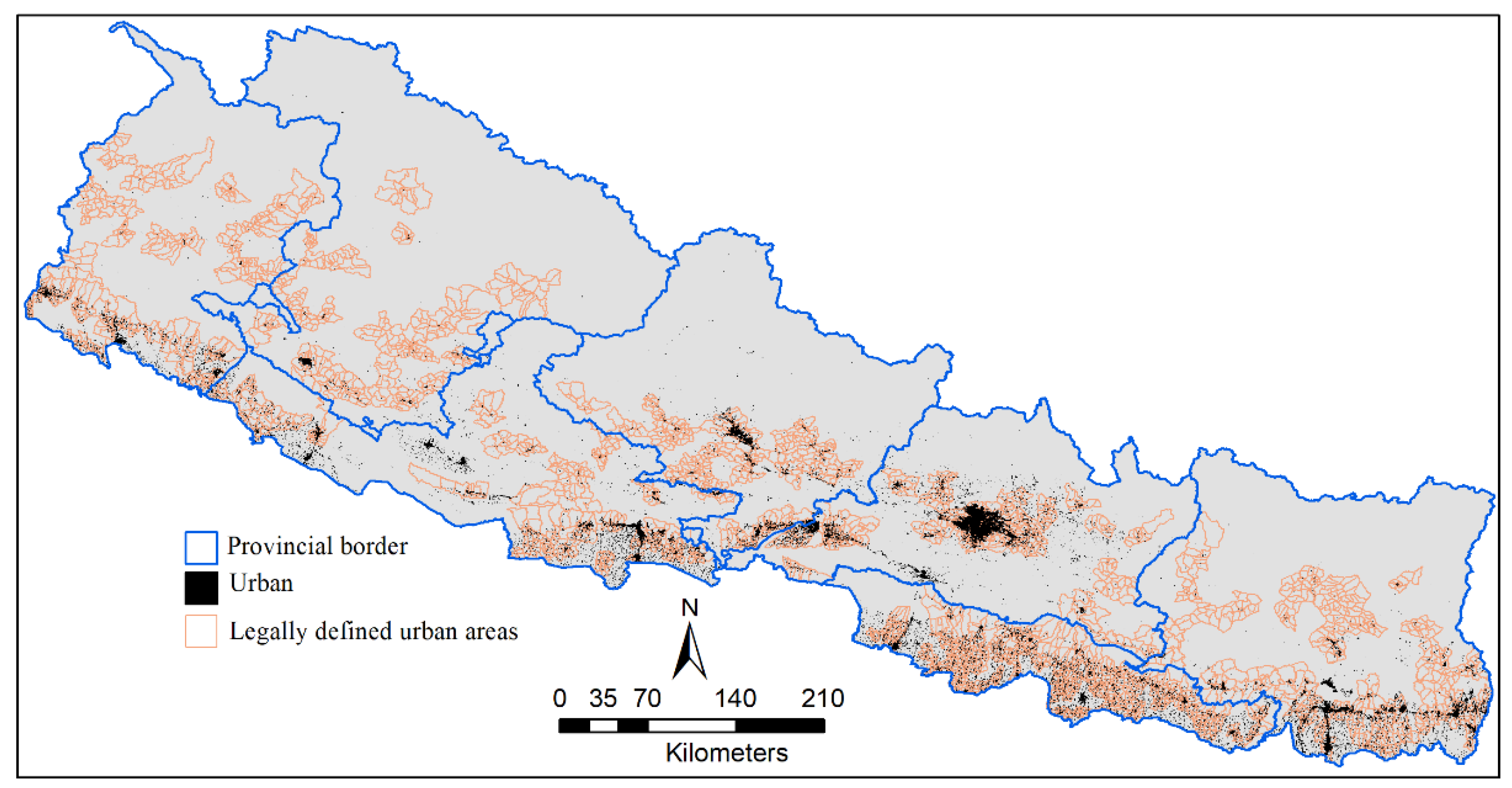

As shown in

Figure 9, unlike in the overly crowded Kathmandu Valley, and other large towns such as Nepalgunj, Pokhara, Birgunj, Dharan, Itahari, Biratnagar, and other areas, many areas are legally defined as urban after they met the population threshold.

These legally defined urban areas do not have the urban infrastructure, and they often continue to have rural characteristics. In

Figure 9, the black areas represent the true built-in urban area, and the pink area represents the administrative boundary of the urban areas. This suggests that there are many areas that can be called “

ruralopolises” where urban and rural areas are intermingling forming an urban-rural continuum. In these areas, community farming or open-area farming activities are possible. Open areas can be used for urban farming with deep-rooted trees on deep soils. Deep-rooted trees help sequester carbon and restore atmospheric carbon into the soil. Thus, the urban farming technique not only can contribute to atmospheric amelioration but also in human health and food security.

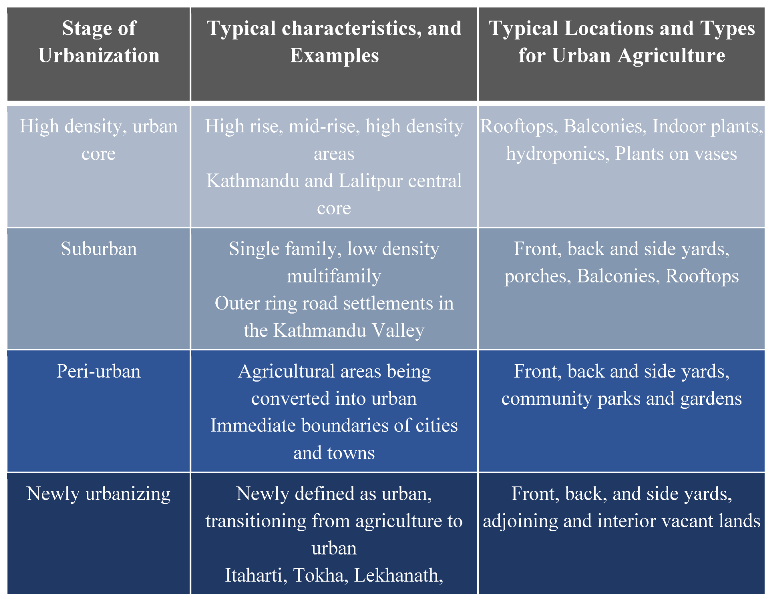

In Nepal, urban areas are developing in different stages, and urban farming is emerging in different forms (

Table 1). In the dense and well-developed urban centers, urban agriculture happens in smaller hardscapes on and around the buildings. In suburban areas, urban agriculture can be seen on the front, back and side yards of residential lots. In emerging urban areas, urban farming can be found on the several vacant lots and open spaces spread across the cities and towns.

5. Food and Human Health

Food is produced and processed that gets transported to markets near the population centers. This practice has often been the cause of several health problems such as diabetes, lung disease, cancer, and cardiac to name a few. Despite recent advances in high-quality drugs, better diagnosis, better hospitals, and advances in biomedical research, people are suffering from many more new diseases. Most of these causes are due to our sedentary lifestyles and the processed food that depends on insecticides and antibiotics.

Food can have a major impact on individual health and well-being, and on the physical environment. To meet the food need of the growing population, producers use chemical fertilizers, growth hormones, and antibiotics to protect animals and plants against diseases. To expand farmland, many forest areas are burnt down, emitting significant amounts of greenhouse gases. The modern agricultural practice has massively over-farmed lands, and the natural fertility of the soil can sometimes be completely wiped out. Farmers need to apply more chemical fertilizers to bring back soil fertility. For high levels of production, many farmlands are planted with commercial monocrops supported by fertilizers and pesticides. Many of these products require a lot of fossil fuels to farm and transport food.

Many of the vegetables and fruits come packed in plastic bags pumped with nitrogen to protect them from bacteria. This is a very inefficient, and unsustainable way to produce and supply food because producers must pack, and transport food, often with refrigeration to long distances. The whole system is completely dependent on fossil fuel from tilling the land to packing to transporting packed food and disposing of wastes.

At a global scale, half the world’s arable land and 30 percent of the world’s water have already been used. Producing food in urban areas for individual consumption and local supply could mitigate some of the problems described earlier. Urban areas are short of space, but growing food can start in aquaponics facilities in smaller areas. Aquaponics is a way to grow fish and utilize their waste as nutrients for plants. Fish produce ammonia as a byproduct which is a waste. If this ammonia is left in water, it builds up and becomes toxic. However, it is possible to pump out ammonia-rich water into a separate biofilter. In this ammonia-rich water, microorganisms can convert waste ammonia into a very useful fertilizer. Then, nitrate-rich fertilizer can be pumped out and fed to plants whose roots may be suspended in water and draw out all that nutrient. Eventually, the water becomes nitrate free for the fish. It becomes an efficient closed-loop ecosystem that is sustainable, and scalable, and it is not wasteful. Aquaponics can be fully integrated into the urban farming system. We can use fish and utilize their waste to convert it into fertilizer and that fertilizer can be transformed into nutrients for plants. Plants and fish can be symbiotically maintained in a healthy environment in a closed-loop ecosystem.

Coffee and tea wastes can be recycled to help crops grow. After preparing coffee and tea, people discard the ground coffee and tea as waste. Using a biodegradable pot, mushrooms can be grown on coffee and tea substrate. Once the mushroom is harvested, the leftover can be fed to worms because they eat take waste products. This closed-loop circuit can convert the inputs into three valuable outputs. First, fish use water to intake diffused oxygen, but discharge nitrate into the water making water polluted. Second, the polluted water becomes a nutrient for plants. Plants purify the wastewater and make this water reusable for fish while generating oxygen for humans. Third, fish byproducts after using flesh can be utilized to grow mushrooms. Mushroom release CO2 that can be given to plants. Any excess products can be fed into an anaerobic digester which produces all the energy to heat and power an integrated urban farm

Urban farming is a response to the increase in population, shortages of food, agricultural land (Clark and Tilman, 2017), and increasingly complex relationships between the surrounding environment with sociocultural activities—the bionomics (Davis, 2014). It is also an antidote to minimizing the losses of food grains from the time of harvest up to the end uses, and to mitigating various environmental problems (Payen et al., 2022). The shortage of food in local markets was highlighted with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic when the food supply chain broke down. The pandemic not only created shortages of materials required to produce food, but it also led to a decrease in food production by around three percent (Midmore and Jansen, 2003). All these factors seriously disrupted the global supply chains (KrASIA, 2022). In these types of situations, urban farming can provide a cushion between commercial agriculture and urban communities. Urban farming can help reduce food import and reduce food supply chains while growing a wide variety of food all year round using both soils and soilless media such as aeroponics or hydroponics. Since each agricultural crop is tended personally and manually, the food production per unit area of land also remains high (KrASIA, 2022). As the production is at the doorstep, fresh food can be served within a few hours of harvest. For example, in Singapore, urban tillers deliver food within eight hours of harvesting. Likewise, in Indonesia, farmers have developed an e-grocery platform, named Sayurbox, where customers can buy groceries directly from the farmers (KrASIA, 2022).

Using the 21st century technology, urban farming could act as an antidote to various obstacles such as transportation problems emanating from the shortages of fossil fuels (Mbow et al., 2019), to minimize 21 and 37 percent of anthropogenic gases emitted from agriculture (IPCC, 2019), and minimizing the levels of soil and water pollution resulting from excessive uses of fertilizers in commercial farming. Such approach could be critical in mitigating the impacts of climate while financially protecting farmers. Agricultural produce is consumed in the household or locally rather than taking it away for marketing. This will improve the efficiency of the whole food operation. Urban farming can enhance food security (Leh, 2011) at local, regional, and national levels while reducing food wastes, and making community prosperous through the enhancement and preservation of cultural traditions. It is also a process of involving family members in food production mechanism and supplying food to the needy populations (USDA, 2022).

Because of the targeted use, urban farming generally uses less water per unit of production than conventional farming, and it follows the notion of the circular economy. In a circular economy, almost all the activities are monetized, wastes are fully recycled and utilized, and food becomes completely organic. For example, all the stems of the salads, the peels of cucumber, potato, orange, and sweet potato, are fed to plants, and the byproducts have monetized values. Algae can be used to convert it into fertilizer. Using modern technology, emission from vehicles is tapped and mixed with algae at the drainage point of sewage pipes. As emission is fed to the sewage water, algae consume emitted gases tapped from vehicles and industries. This emission is utilized by algae and algae grows profusely, which can be used to make fertilizer. In the Kathmandu Valley, recently, algae have been converted into synthetic leather by students at the Institute of Engineering at Pulchowk, Lalitpur. Additionally, algae can be used as mulch to retain soil moisture, which helps improve crop production. For example, it has been reported that potato yield with algae mulching was 10 times more than from the traditional farming methods in open areas (Payen et al., 2022).

In a highly dense city like those in the Kathmandu Valley, shallow-rooted vegetables are grown on rooftops, balconies, façades, indoor, windows (Payen et.al., 2022; Mintorogo,2017), abandoned buildings, and interstitial spaces between legal lands. Taller buildings obstruct solar radiation that hinders the process of photosynthesis (Thomaier et al., 2015). These built-in infrastructures, offer very little room to produce vegetables and fruit, often crops are grown on vertical structures (Taufani, 2017). These spaces do not have the provisions required to grow deep-rooted plants. In vertical structures, often light becomes insufficient. To supplement this solar radiation, LED light is used. In such narrow spaces, using animal dung to grow crops emits methane gas, thus, using compost helps in sequestering greenhouse gases.

Light Imitating Diode (LED) produced light can be used to sustain light intensity in a controlled environment. This will help create more efficient growth and a much higher yield per growing area. Several crops with adventitious roots can be grown on biodegradable pots such as those made from coconut husk. For example, mushrooms, lettuce, kale, cauliflower, broccoli, pepper, and zucchini can be grown in such pots. In addition to these crops, other tubers and legumes can be cultivated on an urban rooftop in a horizontal manner. However, in peri-urban farms, they could be grown in a horizontal manner directly on the ground soil in the open spaces on building sites. It is estimated that gray area farming may contribute to 5 and 10 percent of global production while also ameliorating global climate change (Clinton et al., 2018; Abdulkadir et al., 2012).

If urban and peri-urban areas are efficiently utilized to produce agricultural crops, the food produced there can be enough to feed approximately 30 percent of the total urban population in different geographic regions of the world (Kriewald et al. 2019). Coffee and tea wastes along with the barks peeled from cucumber, potato, and stem and leaves from the salad can be used to grow such agricultural crops. Though such crops require water, the quantity of water used is 70 percent less than in the traditional farms for the same amount of harvest. Urban farming helps in cooling global climate by using less water, less space, and mitigating the heat radiated by built up hard surfaces (Payen et al., 2022). Ambient cooling happens in two ways. First, soil moisture cools the nearby environment, and second, evapotranspiration and oxygen generated from plans also contribute to the cooling of the environment. Thus, urban farming can contribute to accomplish twin goals, increase in local food production and environmental cooling. Most importantly, urban farming will help to reduce the mounting food waste.

6. The Mounting Food Waste

Even though the world has been facing food shortages, the global food system has become incredibly wasteful. A large amount of energy, water, and land is used to grow food in commercial farms. Produced food is transported to various places to make it available to needy people. Transportation of food over long distances becomes an inefficient operation. Global data suggests that 10 percent of food is lost during cultivation, seven percent is lost during the harvest, 12 percent is lost during the processing or point-of-sale, and another 11 percent is lost after it has been purchased or sold. That means a total of over a third of the food produced globally is wasted in the production and delivery process. Urban food production involves a short supply chain because most of the products will be consumed locally (Yoshida and Yagi, 2021). While doing so, circular economic activities become vibrant and diversified. A circular economy not only contributes to the creation of employment but also contributes to mitigating the negative effects of future food system disruptions. A Public Private Partnership (PPP) approach may be instrumental in this endeavor.

7. Public-Private Partnership (PPP)

Gerrard (2001) defines Public-private partnerships (PPPs) as those that “combine the deployment of private sector capital and, sometimes, public sector capital to improve public services or the management of public sector assets.” Public and private bodies can work together to pool resources and funds to leverage agricultural technology (Ferroni and Castle, 2011). In PPP, public institutions and private individuals collaborate to consolidate isolated approaches, resources, and services to cope with the challenges faced by farming communities (G-20 Summit in Toronto, 2010). The state offers logistic support, legal framework, working avenue, and field resources. Academic and research institutions can assist with physical infrastructure, and private organizations support technology and innovative research.

PPP helps in unlocking digital advisory services to enhance productivity with the improvement of soil health and enriching weather information using various sensors. Digital advising on agronomic services, financing, insurance services, and weather patterns help landowners to improve farm production. The private sector becomes critical in the development of innovative solutions that provide expertise in plant sciences, genomics, and bioinformatics. However, the private sector involves in programs only when there is a chance for commercial incentive. Small farmers will use services from the private sector only if there is a financial return. Thus, PPP eventually helps bridge between markets, services, and technologies. Advanced technology may include bio-fortification, a method of breeding techniques to improve seed variety to accomplish objectives of genetically engineering food variety that can provide richer minerals and vitamins, and micronutrients and can be cultivated cost-effectively and sustainably (Ferroni and Castle, 2011).

Under the PPP programs, farmers can get services in emerging technologies like artificial intelligence (AI), the internet of things (IOT), blockchain, and drones at competitive prices. Several research organizations in Nepal, such as Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC), Agricultural and Forestry University, National Commercial Crop Research Centre, National Horticulture Research Center, and agriculture research stations located across the country, having facilities for testing, and validating information with high credibility, can provide services to farmers. The existing body of agricultural research from universities and other institutions can be better leveraged to scale down or up of any work done by private agricultural technology. Such vibrant entrepreneurship culture among all the innovators, including students, faculty, entrepreneurs, and grassroots innovators, and especially youth, women, and farmers can work together and produce innovative ideas to boost agricultural production.

The endeavor of PPP fails if it is not operated transparently. However, open communication does not always come naturally as individuals would not feel comfortable unless benefits and intellectual property rights are assured, and transparency is maintained. Investment happens only when fundamental commercial rights are assured to entrepreneurs. PPPs may not be the right choice to solve every challenge in agriculture because entrepreneurs would act very carefully on a smaller scale. If private investors are assured of the security of their investment, only then they will agree to make investments in agriculture.

The importance of PPP has been realized during 2020-22 when the global food supply chain system was disrupted due to COVID-19 pandemic and the government alone was not able to address the shortcomings. Additionally, the 2022 war in Ukraine has massively pressured the agricultural sector in both developed and developing countries to provide more sustainable agricultural options while mitigating the environmental issues (Florian et al. 2022). Agriculturists have been developing various methods to utilizing different urban spaces, for example, rooftops, indoor farming, and hydroponics and compare their productivities with soil-based agriculture. A comparative analysis of the productivities calculated using equation (i) reveals that urban farming performs better per unit of investment and space for various crop products (

Table 2) (Payen et al., 2022).

where xi corresponds to the yield value (in kg m−2cycle−1) for observation i (i=1 to n) and n is the sample size.

In urban agricultural systems, crops are grown either in a “hydroponic system” or aquaponic system, or soil-based systems (FAOSTAT, 2022). Equation (i) is appropriate only if the crop is grown in a soil-based system that will include using compost or manure.

Equation (i) can be applied to all geographic areas because urban farming is done at a smaller scale and each plant receives intensive care.

8. Estimated Avoidance of Greenhouse Gases by Urban Agriculture in Nepal

Urban agriculture can help avoid emissions of greenhouse gases caused when traditionally produced agricultural products are transported to the urban markets. Obviously, the absorbed carbon dioxide will be changed into biomass production. Puigdeta et al. (2021) and World Bank (2019, 2020) estimated that it is possible to absorb 205 kg of CO2e per person from urban agriculture.

Since “90 percent of the plant biomass consists of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, photosynthetically reduced carbon products (photoassimilates) are transported from sources, sites of production, to sinks, sites of growth and storage” (van Bel et. al., 2003). Using the allometric equations, it is possible to estimate the carbon use efficiency (CUE) of plants. However, in doing so, there are some uncertainties because CUE may vary based on plants and the surrounding environment. Therefore, often variations are expected between 15 and 20 percent for above-ground biomass. For the below-ground biomass, however, the estimation varies between 20 and 50 percent of the above-ground biomass (Meyer, 2022) because herbaceous plant species sequester less carbon depending upon the types of compost used and deep-root plants sequester carbon based on the depth of soils and other conditions of the soil. Phytologists have concluded that the below-ground biomass of plants is approximately 25 percent of the above-ground biomass, however, this may vary with rhizome plants (Araki et al.,2020) such as canna lilies, bearded iris, ginger and bamboo, and tuberous plants such as asparagus, airplane plant, dahlia, daylilies, peonies, some irises, sweet potato, taro, and many others. The productivity of plants varies based on the CUE. Assuming high CUE at 85 percent and low CUE at 80, the above-ground biomass of plants is presented in

Table 3.

The following calculation provides an estimate of the number of greenhouse gases that can be avoided by the practice of urban agriculture in Nepal.

Total urban population in Nepal is approximately 19 million (66% of 29 m) (CBS, 2021)

As an average household consists of 4.32 individuals, total no. of urban households 19/4.32 = 4.4 million

Some 10% of households may be doubling up in the dwellings, thus, the estimated urban number of dwelling units = 3.96 m

Assuming 25% of the households live in multiunit complexes with limited balcony, rooftop, and ground spaces for farming, the total number of dwellings where urban farming is possible = 2.97 m (representing 12.8 m people)

(Reference: 205 kg CO2e per person avoidance due to urban agriculture in Madrid (Puigdeta et al, 2021))

In Nepal, let us assume 20.5 kg CO2e per person avoidance (per capita/yr. emissions. This is based on the per-capita annual emission of 4.5 Tons in Spain (2019) and for Nepal 0.47 T (approx. 10 percent of Spain) (2019)

If all urban residents practiced urban agriculture in Nepal, total annual Co2e avoidance = 262,400 T/yr.

Based on the carbon use efficiency, the above and belowground production from urban farming is estimated as below:

In average, a person consumes about 590 grams (0.000591 metric tons) of vegetables or fruits in a day. Nepali urban dwellers need 12.8 million ~ 13 million x 0.000591 = 7,683 metric tons a day. Annually, Nepali urban dwellers need 7,683 * 365 = 2,804,295 tons. Nepal needs to adapt urban farming intensively in order to meet the gap of 2,607,495 tons under low CUE and 2,594,375 tons under high CUE.

-

a.

Estimated Urban Food Production, and Contributions to Household Income

We can estimate the approximate acreage that can be used for urban agriculture in Nepal by making some simple assumptions as follows.

The total number of dwelling units (DU) 3.96 million (see section 6)

Typical size of dwelling units = 90-150 square meters (average 120 square meters); 30 m2 can be assigned to a dwelling unit (DU)

Area available for urban farming on flat roofs (assuming half of the buildings have flat roofs) and that in on average buildings are two stories, balconies (typically 5m2/DU), and front/back/side yards (typically 5 m2/DU) = 30+5+5 = 40 m2

Assuming half of the available area is used for urban farming, each DU can use 20 m2 for farming.

Referring to

Table 1 in Section 6.1, productivity per square meter of 3 kg of mixed typical vegetables (potato, beans, cabbage, fruits etc.), total production is 60 kg/growth cycle (3 times a year) = 778 kg/yr./household (an average household consists of 4.32 persons).

The production per household = 778 kg/yr. It will be monetarily equivalent to, approximately Rs 46,680/yr./household. Assuming an average price of the typical vegetables to be Rs 60/kg in 2022. The prices are based on the price list published in major newspapers in Kathmandu. In 2022 exchange rate, this is approximately equal to USD 360.

Annual food expenditure per household in Nepal is Rs 144,330 (45% of 322,730)/yr.

(USD 1,206 in 2017). (Kathmandu Post, 2017)

Assuming a similar expenditure in 2022, and assuming any growth in expenditure and the rise of dollar against Nepali Rupees can wash each other out, urban agriculture can provide 27% of a household’s food expenditure.

With the above assumptions, we can conservatively assume that urban agriculture can save a household 25% of their food expenditure.

9. Conclusions and Recommendations

Traditional agricultural and good supply systems have been facing two major problems. The food growing process is energy intense causing land, air, and water pollution. The supply chain from distant farmlands to urban areas is long and unpredictable causing waste and adding to pollution and the emission of greenhouse gases. Urban farming with a distributed production that is close to the point of consumption can greatly help in supplementing the food needed by urban households. It can also help in reducing pollution, promoting healthy food, and mitigating some issues related to the food supply chain. Further, it can also help reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases, help urban households save money on food, and sometimes make money by commercializing small household urban farming.

Urban farming can be helped by a public-private partnership (PPP), where public institutions can support individual households in technology, training, and marketing of their products. The agriculture extension programs of many universities in the United States are a great example of how public research can support urban farming.

It is recommended that the local authorities and institutions in Nepal support urban farmers with technology, marketing, training, and appropriate policies. The municipal governments can create helpful regulations in zoning and land use to promote urban farming while protecting public health and safety. They can also facilitate the creation of urban farmers’ markets for households who produce extra food and wish to sell them. The building codes should also foresee potential urban farming on terraces, on-site, balconies, and rooftops, and ensure that waterproofing and load bearing for the additional soil, water, and plants is included in the calculation required for the structure of buildings.

Urban farming is relevant for rapidly urbanizing Nepal. Nepal’s census records show that over 65 percent of the total population of Nepal lives in urban areas. However, many of such urban classified areas have rural settings making Nepal a “ruralopolis”. Though many recent rural areas are defined as urban, these newly created towns have plenty of agricultural lands within their territories. These farmlands can offer the best ecosystems for urban farming in or around urban and peri-urban areas to produce food to meet the needs of the family and to their traditional customers.

To make the best use of opportunities provided by urban farming, appropriate and enabling policies related to planning practice, and zoning ordinances, comprehensive plans need to be developed. This will be a good PPP practice. Similarly, urban agriculture studies and the promotion of “foodsheds” (like watersheds) for urban population groups can help to advance urban agriculture.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Any data used in the study can be requested from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Keshav Bhattarai is Professor Geography at Central Missouri University, in MO, USA, and has extensive experience in teaching, practice and research related to planning, geography, environment, forestry and Geographic Information System (GIS).

Ambika P. Adhikari is a Principal Planner at City of Tempe, AZ, USA, and Distinguished Adjunct Fellow at Institute for Integrated Development studies (IIDS), Nepal. He has extensive experience in urban planning, and international development in Nepal, USA, Canada, and several other countries.

| 1 |

One milli siemens is the electrical conductance equal to 1/1,000 of a siemens, which is equal to one ampere per volt. |

References

- Abdulkadir, A., Dossa, L. H., Lompo, D. J. P., Abdu, N., & van Keulen, H. (2012). Characterization of urban and peri-urban agroecosystems in three West African cities. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 10(4), 289–314. [CrossRef]

- Araki KS; Nagano AJ; Nakano RT; Kitazume T; Yamaguchi K; Hara-Nishimura I; Shigenobu S; & Kudoh H (2020). Characterization of rhizome transcriptome and identification of a rhizomatous ER body in the clonal plant Cardamine leucantha. Sci Rep. 2020 Aug 6;10(1):13291. PMCID: PMC7413523. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballantyne AÁ, Alden CÁ, Miller JÁ, Tans PÁ, White J W C. (2012). Increase in observed net carbon dioxide uptake by land and oceans during the past 50 years. Nature. 488(7409):70– 72. [CrossRef]

- Bradford MA, Crowther TW. (2013). Carbon use efficiency and storage in terrestrial ecosystems. New Phytologist. 199(1):7– 9.

- CBS (2022), Preliminary Report of National Census 2021, Nepal. https://censusnepal.cbs.gov.np/Home/Details?tpid=1&dcid=0f011f13-7ef6-42dd-9f03-c7d309d4fca3.

- City of Phoenix (2020). 2025 Food Action Plan. chrome-www.phoenix.gov/sustainabilitysite/Documents/FINAL%202025%20Phoenix%20Food%20Action%20Plan%20Jan%202020.pdf.

- City of Tempe (2014), General Plan 2040. www.tempe.gov/home/showpublisheddocument/86155/637395866769170000.

- Clark, M. and Tilman, D. (2017). Comparative analysis of environmental impacts of agricultural production systems, agricultural input efficiency, and food choice. Environmental Research Letters, 12(6), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Clinton, N., Stuhlmacher, M., Miles, A., Uludere Aragon, N., Wagner, M., Georgescu, M., et al. (2018). A global geospatial ecosystem services estimate of urban agriculture. Earth’s Future, 6(1), 40–60. [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. F.; D’Odorico, P.; and Rulli, M. C. (2014). Moderating diets to feed the future. Earth’s Future, 2(10), 559–565. [CrossRef]

- De Lucia EH, Drake JE, Thomas R B, Gonzalez-Meler M I Q U E L (2007). Forest carbon use efficiency: is respiration a constant fraction of gross primary production? Global Change Biology. 13(6):1157–1167. [CrossRef]

- Ferroni, Marco, and Castle, Paul (2011). Public-Private Partnerships and Sustainable Agricultural Development. Sustainability. 3, 1064-1073. ISSN 271-1050. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2022). FAOSTAT - Crops and livestock products. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/%23data/QCL.

- FAO (2011) The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture. Managing System at Risk.

- Gerrard, M. (2001), Public-Private Partnerships, in “Finance and Development”, a quarterly magazine of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2001/09/gerrard.htm.

- Henne, B. (1012), How far did your food travel to get to you? Michigan State University, MSU Extension. https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/how_far_did_your_food_travel_to_get_to_you.

- Hodgson, K., Campbell, M.C, and Bailkey, M (2011). Urban Agriculture: Growing Healthy, Sustainable Places. American Planning Association. Planning Advisory Service. Report Number 563.

- IPS (International Phytotechnology Society) (2014) 11th International Phytotechnologies Conference. International Phytotechnology Society. N. Kalogerakis, and T. Manois (eds). Book of Abstract. Heraklion, Crete, Greece, Sept. 30-Oct. 3, 2014.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2019). Summary for policymakers. In P. R. Shukla et al. (eds.), Climate change and land: An IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems (pp. 1–36). Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/chapter/summary-for-policymakers/.

- KrASIA (2022) The future of agri-food tech in Southeast Asia: Agriculture in the digital decade. Written by Deloitte Southeast Asia Innovation Team. 19 Apr 2022. https://kr-asia.com/the-future-of-agrifood-tech-in-southeast-asia-agriculture-in-the-digital-decade.

- Kriewald, S.; Pradhan, P., Costa, L.; García Cantú Ros, A.; and Kropp, J. P. (2019). Hungry cities: How local food self-sufficiency relates to climate change, diets, and urbanisation. Environmental Research. Letters, 14(9), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Leh, O.L.H., et al. (2011). Urban farming: Utilisation of infrastructure or utility reserved lands. in Business, Engineering, and Industrial Applications (ISBEIA), 2011 IEEE Symposium on. 2011. IEEE.

- Maraseni TN, Qu J (2016) An international comparison of agricultural nitrous oxide emissions. J Clean Prod 135(2016):1256–1266. www.elsevier.com/locate/jclepro. [CrossRef]

- Mbow, C et al. (2019). Food security. In P. R. Shukla et al. (Eds.), Climate change and land: An IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems (pp. 437–550). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/chapter/chapter-5/.

- Meyer, Victoria (2022) Ho we measure the carbon capture potential of forest. Terraformation. https://www.terraformation.com/blog/how-to-measure-carbon-capture-potential-forests Accessed December 23, 2022.

- Midmore, D.J., and H.G. Jansen (2003). Supplying vegetables to Asian cities: is there a case for peri urban production? Food Policy, 28(1): p. 13-27. [CrossRef]

- Mintorogo, D.S.; W.K. Widigdo; and A. Juniwati (2017). Remarkable 3-in-1 Pakis-Stem Green Roofs for Saving Thermal Flat Rooftop. Advanced Science Letters, 23(7): p. 6173-6178. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Maurice, Iglesias Amara Richa (2020). Urban agriculture in Kathmandu as a catalyst for the civic inclusion of migrants and the making of a greener city. Frontiers of architectural research. March 2020 p 169-190. Vol 9 Issue 1. [CrossRef]

- Paradiso, Roberta; Ceriello, Antonio; Pannico, Antonio; Sorrentino, Salvatore; Palladino, Mario; Giordano, Maria; Fortezza, Raimondo; & De Pascale, Stefania (2020) Design of a Module for Cultivation of Tuberous Plants in Microgravity: The ESA Project “Precursor of Food Production Unit” (PFPU). Front. Plant Sci. 15 May 2020. Sec. Plant Abiotic Stress. [CrossRef]

- Payen, S., Basset-Mens, C., and Perret, S. (2015). LCA of local and imported tomato: An energy and water trade-off. Journal of Cleaner Production. 87, 139–148. [CrossRef]

- Peuigdueta et al (2021), Urban agriculture may change food consumption towards low carbon diets. Global Food Security. Volume 28, March 2021, 100507. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211912421000171. [CrossRef]

- Quinton, Amy (2019) Why Is One-Third of Our Food Wasted Worldwide? Study Examines Causes of Food Waste and Potential Solutions. UC Davis. October 1, 2019. https://www.ucdavis.edu/food/news/why-is-one-third-our-food-wasted-worldwide Accessed December 22, 2022.

- Raja, S et al (2008). A Planners Guide to Community and Regional Food Planning. Planning Advisory Service Report no. 554. Chicago: American Planning Association. http://growingfoodconnections.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/1970/01/PlannersGuideToCommunityRegionalFoodPlanning_PAS554Excerpt.pdf.

- Richter, Hannah and Roser, Max (2018). Urbanization: Our World in Data. Urbanization - Our World in Data. Accessed December 21, 2022.

- Roxburgh SH, Berry SL, Buckley TN, Barnes B, and Roderick ML. (2005). What is NPP? Inconsistent accounting of respiratory fluxes in the definition of net primary production. Functional Ecology. 19(3):378-382.

- Shrestha, Shristi (2011) Urban farming for community well-being in Kathmandu. M Sc. Thesis. Wageningen University and research Centre. https://edepot.wur.nl/176382.

- Taufani, B. (2017). Urban Farming Construction Model on the Vertical Building Envelope to Support the Green Buildings Development in Sleman, Indonesia. Procedia Engineering, 171: p. 258-264. [CrossRef]

- The G-20 Toronto Summit Declaration. In Proceedings of the G20 Summit, Toronto, Canada, June 2010; pp. 1-27.

- The Kathmandu Post (2022), Nepalis household spending up 9pc, April 7, 2017. https://kathmandupost.com/money/2017/04/07/nepalis-household-spending-up-.

- The World Bank (2018). Projection of urban population in Nepal for 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?locations=NP.

- Thomas, F et al. (2022). How Much Food Can We Grow in Urban Areas? Food Production and Crop Yields of Urban Agriculture: A Meta-Analysis. Earth’s Future. Advancing Earth and Space Science. First published: 23 August 2022. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2022EF002748. [CrossRef]

- Throatier, S. et al. (2015). Farming in and on urban buildings: Present practice and specific novelties of zero-acreage farming (ZFarming). Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 30(1), 43–54. [CrossRef]

- UN Habitat and EU (2014) “Training Manual on Roof top Gardening”. https://www.unhabitat.org.np/recent_publish_detail/training-manual-on-rooftop-gardening.

- UNFCCC (No date), Promotion of Rooftop Farming as Part of Kathmandu’s Climate Change Strategy. https://unfccc.int/climate-action/un-global-climate-action-awards/winning-projects/activity-database/promotion-of-rooftop-farming-as-part-of-kathmandu-s-climate-change-strategy.

- USDA (2022). U.S. Department of Agriculture. USDA’s Office of Urban Agriculture and Innovative Production. https://www.usda.gov/topics/urban Accessed November 22, 2022.

- Van Bel, A. J. E.; Offler, C. E.; and Patrick J. W. (2003) Photosynthesis and Partitioning\ Sources and Sinks. Encyclopedia of Applied Plant Sciences, pages: 724-734. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B0122270509000892?via%3Dihub Accessed December 23, 2022.

- Vermuelen SJ, Campbell BM, Ingram JSL (2012) Climate change and food systems. Ann Rev. Environ Resource 37:195–222. [CrossRef]

- WHO (2022) Food Safety. World health Organization. 19 May 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safety Accessed December 22, 2022.

- Yoshida, S., and Yagi, H. (2021). Long-term development of urban agriculture: Resilience and sustainability of farmers facing the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Sustainability, 13(8), 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Zwart, Jacob, A. and Brighenti, Ludmila S. (2021) Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).