3.2. Factors underlying OVC and selection of work-related rumination aspects (Sample 1)

We factor-analyzed the 24 items selected from the OVC, psychological detachment, distraction, cognitive irritation, and inability to recover-scales. We selected this set of items, because at least one of the OVC-items correlated above .70 with these scales.

We found that a three-factor solution fitted best. However, for the sake of transparency, we also report the coefficients of a two-factor solution in

Table A2 of the supplemental materials that fitted the data slightly worse. In

Table 4, we report the loadings, communalities, and proportion of variance of the focal items derived from the three-factor model. The three extracted factors explained 63% of variance. The focal items loaded unambiguously on one of the three factors and did not yield sizeable cross-loadings. The three factors can be interpreted as

- (1)

inability to unwind from work,

- (2)

psychological detachment, and

- (3)

distraction.

The first factor (inability to unwind) is sourced primarily from the six inability to recover items from the FABA, the three cognitive irritation items, and four of the six OVC items. The first OVC item yields a small loading on the first factor, too. The second factor (psychological detachment) is sourced from the four psychological detachment items of the REQ and the third OVC item tapping into ease of switching off after work. The third factor (distraction) is sourced exclusively from the five distraction items from the WRRQ.

The first OVC item that explicitly captures time pressure turns out to be an unreliable indicator of the inability to unwind-factor, apparently due to its focus on job stressors rather than problems switching off. The reverse-scored third OVC-item that captures ease of switching off turns out to be an indicator of the second factor capturing (ease of) psychological detachment. The sixth OVC-item loads unambiguously, but only moderately on the first factor capturing inability to unwind. We suggest that the rather poor reliability of this item stems from its focus on unfinished tasks as a cause of sleep impairment – which is a very specific symptom of inability to unwind from work. The second, the fourth, and the fifth OVC-items emerge as the most reliable indicators of the inability to unwind from work-factor. Accordingly, we present different versions of the OVC-composite in the correlation tables to report links of more pure or more contaminated variants of OVC and how they relate to outcome variables.

3.3. Implications of the exploratory factor analyses (Sample 1)

Item-level analyses of OVC suggest that at least some of the six OVC items are suboptimal from a psychometric perspective due to too low loadings and cross-loadings. Hence, we recommend removing the first and the sixth item tapping into workload and sleep impairment due to workload to make the scale more internally consistent (i.e., to improve reliability). The proposed 4-item version of the OVC scale avoids confounding distinct aspects in a unidimensional scale. The results reported above suggest that OVC items correlate highly with several aspects of work-related rumination. The core of the scale (3 or 4 out of 6 items) connotes content overlap with inability to unwind from work in off-job time. Our factor analyses provide evidence that overcommitment essentially captures inability to unwind from work as conceptualized and captured in the FABA subscale inability to recover. In the remainder of this paper, we will focus on the 4-item version of the OVC scale throughout all analyses. However, we report bivariate correlations for the 4-item version, the 5-item version and the 6-item version for the sake of transparency.

Besides the specific evidence on the OVC items, the results of the exploratory factor analyses have implications for the structure of work-related rumination. The results suggest that inability to recover as measured with the respective FABA-subscale, cognitive irritation, and OVC might be considered largely redundant constructs or alternative ways of measuring the same underlying construct. Hence, inability to recover, cognitive irritation, and OVC might be applied largely interchangeably to capture inability to unwind from work. Our results support the distinction between inability to unwind and psychological detachment as the potential antipode of inability to unwind. Hence, inability to unwind is distinct empirically from psychological detachment. On a related note, psychological detachment and distraction emerge as distinct constructs, as well. Psychological detachment and distraction, both refer to ease of unwinding from work in off-job time. However, the emphasis of these scales differs considerably. Whereas distraction items have a more proactive and agentic wording (i.e., making sure one can detach from work), psychological detachment items tend to be more experiential and are not explicitly and unambiguously agentic (i.e., detachment happens to employees no matter, why). Our finding challenges the practice of treating distraction as an alternative measure and an interchangeable scale of psychological detachment. Besides the slightly different content of the items from these two scales, the different response formats (agreement vs. frequency) may have contributed to finding distinct factors. We will revisit the link between psychological detachment and distraction in factor analyses with Sample 2.

3.5. Factorial Structure Underlying the Ten Work-Related Rumination Constructs (Sample 2)

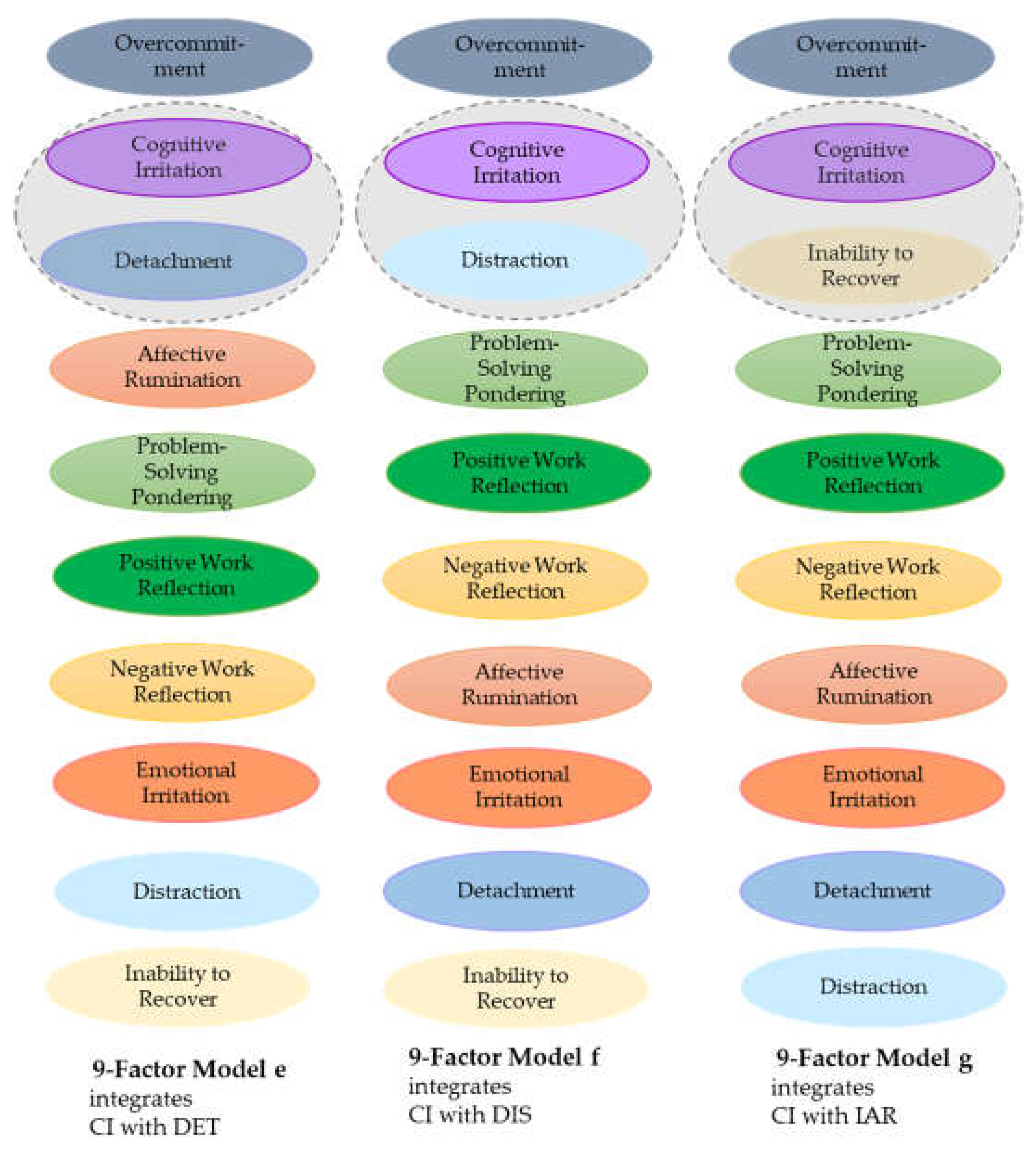

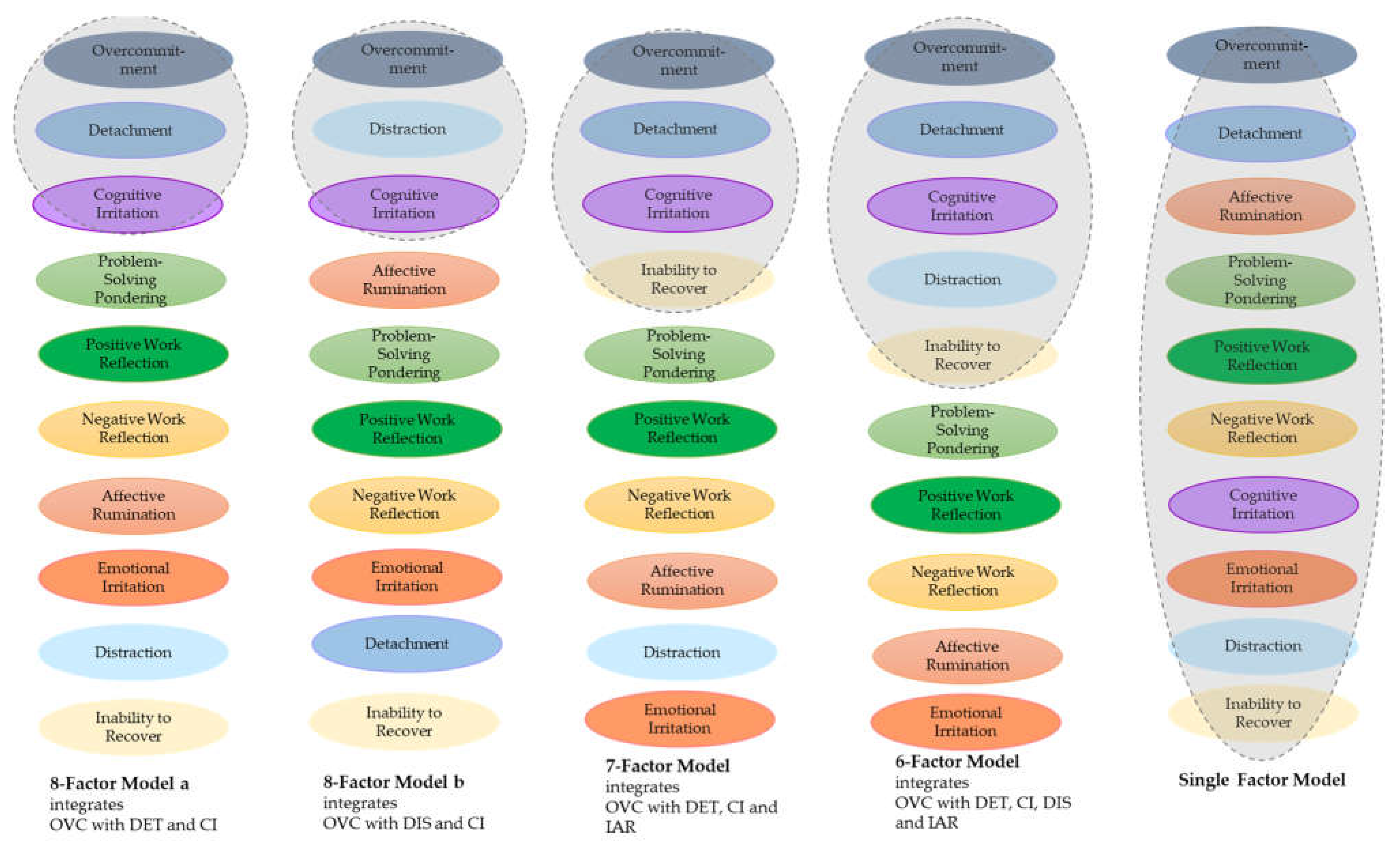

In

Table 5 we present the correlations among the focal variables in Sample 2. We applied confirmatory factor analysis to specify competing factorial structures. We specified a measurement model with all items loading on their respective factors. We tested a 10-factor model consisting of (1) overcommitment, (2) psychological detachment (REQ), (3) affective rumination (WRRQ), (4) problem-solving pondering (WRRQ), (5) positive work reflection, (6) negative work reflection, (7) cognitive irritation, (8) emotional irritation, (9) distraction (WRRQ), and (10) inability to recover (FABA). We freely estimated covariances among all factors across all confirmatory factor analyses. We compared this focal model with a set of competing models. More specifically, we tested a single-factor model with all items loading on a common factor. Furthermore, we specified models combining two or more work-related rumination factors in case these factors correlated very highly. For instance, cognitive irritation correlated above .80 with OVC, psychological detachment, distraction, and inability to recover. In

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 we illustrate the set of competing factorial structures examined.

We tested these models applying the lavaan-package version 0.6-11 [

79] for the R statistics environment. We applied the robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR) to handle non-normally distributed data. We refer to standardized coefficients (loadings, covariances) when reporting results. In

Table 5, we report the fit indices of the focal model and the plausible alternatives. We report robust estimates of Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). According to Schumacker and Lomax [

80] CFI- and TLI-values above .90, RMSEA-values below .08, and SRMR-values below .10 signal acceptable fit. We compared nested models by means of the χ²-difference test to identify the structure that fitted the data best.

In

Table 6 we report the fit indices and comparisons across models. As evident from

Table 6, the preferred 10-factor model achieved an acceptable fit to the data as reflected in CFI = .920, TLI = .911, RMSEA = .059, and SRMR = .058. The 10-factor model fit the data better than any of the competing models combining either OVC-items or cognitive irritation-items with the most highly correlated variables. More specifically, combining OVC and psychological detachment to a common factor (Model 9a) did not improve model fit. Combining cognitive irritation and overcommitment (Model 9b), detachment (Model 9e), distraction (Model 9f), and inability to recover (Model 9g) to load on a common factor did not improve model fit. However, the 10-factor model and Model 9b combining OVC and cognitive irritation fit the data equally well. Hence, distinguishing between OVC and cognitive irritation is barely warranted.

In

Table 7, we report the estimated correlations among the factors from the 10-factor model. These results help to qualify and extend the model comparisons reported above. From

Table 7 it is obvious that several of the ten work-related rumination constructs studied are very highly correlated. For instance, OVC correlates at Ψ = .96 with cognitive irritation, at Ψ = -.75 with psychological detachment, and at Ψ = .74 with inability to recover. Estimated correlations clearly exceed the threshold of |

r| < .70 for supporting discriminant validity [

64]. Albeit less pronounced, the same applies to correlations between OVC and distraction at Ψ = -.70. Hence, although OVC emerges as a factor technically distinct from the other constructs, the high degree of overlap may render the distinction between OVC and e.g., cognitive irritation practically less useful and relevant.

Besides the high correlation between OVC and psychological detachment just reported, psychological detachment correlates at Ψ = .92 with cognitive irritation and at Ψ = .74 with distraction. The correlation between psychological detachment and inability to recover at Ψ = -.68 is very high, too. Hence, psychological detachment and cognitive irritation appear to be barely distinguishable. The overlap with inability to recover is considerable, as well. Psychological detachment and distraction are empirically distinct and tap into slightly different aspects of “switching off” from work. However, from a practical point of view, using psychological detachment and distraction more or less interchangeably is probably reasonable.

Affective rumination correlates moderately with most aspects of work-related rumination. However, correlations to cognitive irritation and inability to recover are Ψ = .67 and Ψ = .64, respectively, pointing to a considerable portion of shared variance among constructs. Problem-solving pondering correlates moderately with most aspects of work-related rumination. The highest correlation emerges to cognitive irritation at Ψ = .61.

Positive work reflection is only weakly or not at all related to any of the other work-related rumination constructs with estimated correlations ranging from |Ψ| = .07 to |Ψ| = .24. Negative work reflection shows weak to moderate links to the other work-related rumination constructs with correlations ranging from |Ψ| = .07 to |Ψ| = .41.

Besides the almost perfect correlation between cognitive irritation, OVC, and psychological detachment, estimated correlations of cognitive irritation with distraction and inability to recover range from Ψ = .86 to Ψ = .88. These findings suggest that cognitive irritation captures almost no unique aspects beyond four of the ten work-related rumination constructs. By contrast, emotional irritation yields weak to moderate links to the other work-related rumination constructs as reflected in estimated correlations ranging from |Ψ| = .21 to |Ψ| = .48.

Inability to recover as conceptualized in the FABA converges particularly strongly with cognitive irritation and OVC as reflected in correlations of Ψ = .88 and Ψ = .74, respectively. The overlap with psychological detachment and affective rumination is considerable, too, as reflected in correlations of Ψ = -.68 and Ψ = .64.

In sum, our analysis of the structure underlying the ten work-related rumination constructs suggests that all ten aspects emerge as empirically distinct factors. Collapsing two or three or these constructs to common factors does not improve model fit. Although this finding suggests that distinguishing these ten aspects is warranted from a psychometric perspective, a closer look at the estimated correlations from a pragmatic perspective reveals that some aspects of work-related rumination are barely distinguishable. Some constructs like positive and negative work reflection have negligible overlap with other constructs. The “famous five” facets (detachment, affective rumination, problem-solving pondering, positive work reflection, and negative work reflection) emerge as unambiguously unique factors. However, the less intensively studied measures – namely cognitive irritation, distraction, and inability to recover – tend to share a large portion of variance with one another or with one or several of the famous five facets. Of note, as obvious from the extremely high correlations, OVC tends to tap into the same content as psychological detachment, cognitive irritation, distraction as conceptualized in the WRRQ, and inability to recover as conceptualized in the FABA. Our results suggest that several of the less extensively studied constructs, such as cognitive irritation, distraction, and inability to recover essentially measure the same aspects of work-related rumination as the psychological detachment scale does. Drawing on these findings, we explore to what extent distinguishing the ten work-related rumination constructs improves the prediction of key aspects of employee well-being and health outcomes.

3.6. Relative Predictive Power of the Ten Work-Related Rumination Constructs (Sample 2)

The redundancies across the work-related rumination constructs reported above suggests that a more parsimonious structure may suffice to capture the full range of work-related rumination. Above, we have argued that the famous five facets are unambiguously unique and that OVC and several less extensively studied constructs like cognitive irritation may be considered more or less alternative operationalizations of psychological detachment. However, these specific measures capture unique aspects of work-related rumination that may contribute to improve the prediction of key indicators of employee well-being and health. Therefore, we set out to compare the predictive validity of the ten work-related rumination constructs vis-à-vis one another. We performed relative weight analysis [

81,

82,

83] to quantify the unique predictive power of each construct regarding six indicators of employee well-being and health, namely (1) physical fatigue, (2) mental fatigue, (3) emotional fatigue, (4) burnout, (5) psychosomatic complaints, and (6) satisfaction with life. Unlike traditional multiple regression models, relative weight analysis explicitly takes into account that predictors may correlate highly among one another (i.e., multicollinearity) [

82] and provides the opportunity to partition variance explained across multiple predictors in a more accurate way [

84].

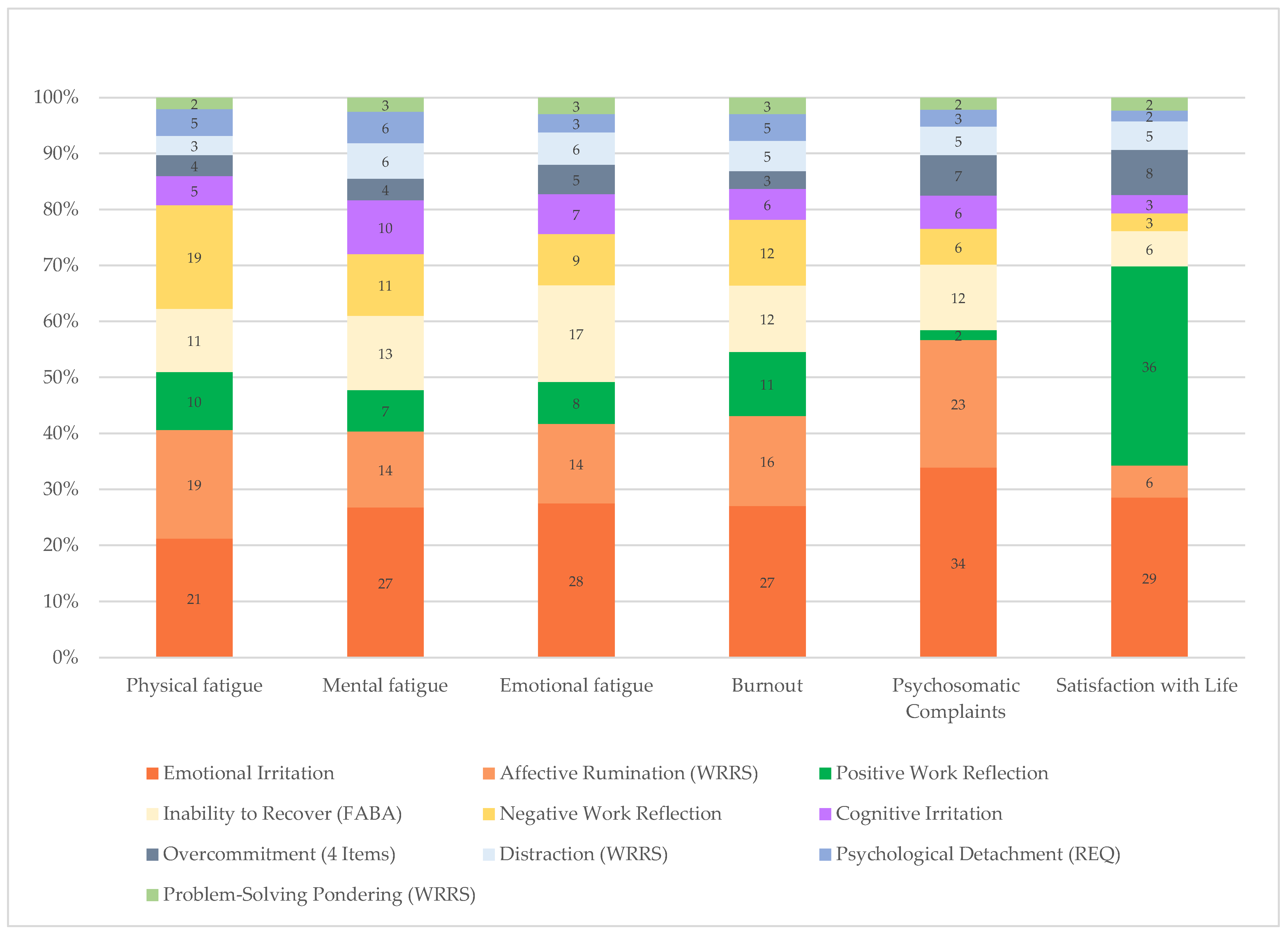

In Tables 8 to 13, we report the results separately for each outcome variable. As evident from

Table 8, combining the ten work-related rumination constructs as predictor results in explaining roughly 30 percent of variance in physical fatigue. A closer look at the relative weights (RW) and the rescaled relative weights (RS-RW%) suggests that each facet explains some variance in physical fatigue. However, only a few constructs explain large portions of the variance explainable by all constructs. Emotional irritation, affective rumination, and negative work reflection each explain approximately 6 percent of the variance in physical fatigue. Positive work reflection and inability to recover each explain about 3 percent of the variance in physical fatigue. In other words, five of the ten work-related rumination constructs explain more than 80 percent of the variance explainable by the whole set of predictors. The other five aspects of work-related rumination explain small portions of unique variance. For instance, psychological detachment uniquely explains only about 1,5 percent of variance in physical fatigue.

A similar pattern of results is evident in

Table 9 focusing on mental fatigue. In total, the ten work-related rumination constructs explain 36 percent of variance in mental fatigue. Again, emotional irritation, affective rumination, inability to recover, and negative work-reflection are among the strongest predictors. Emotional irritation alone explains approximately 10 percent of variance (a fourth of the variance explained by all predictors). Affective rumination, inability to recover each, negative work reflection, and cognitive irritation each explain approximately 5 percent of variance. The other predictors explain about 2 percent of unique variance in mental fatigue.

In

Table 10, we present the results of the relative weight analysis predicting emotional fatigue. In total the ten work-related rumination constructs explain 31 percent of variance in emotional fatigue. Emotional irritation, affective rumination, inability to recover, and negative work-reflection are the strongest predictors. Emotional irritation alone explains approximately 8 percent of variance (a fourth of the variance explained by all predictors). Inability to recover, affective rumination and negative work reflection explain 5, 4, and 3 percent of unique variance, respectively. Positive work reflection and cognitive irritation explain roughly 2 percent of variance in emotional fatigue. Overcommitment, psychological detachment, problem-solving pondering, and distraction explain 1 percent of variance only.

In

Table 11, we present results of the relative weight analysis predicting burnout. In total the ten work-related rumination constructs explain 45 percent of variance in burnout. Like the results for emotional fatigue emotional irritation, affective rumination, inability to recover, and negative work-reflection are among the strongest predictors. Emotional irritation alone explains approximately 12 percent of variance (a fourth of the variance explained by all predictors). Affective rumination uniquely explains 7 percent of variance in burnout. Inability to recover, negative work reflection, and positive work reflection each explain 5 percent of unique variance. Psychological detachment and distraction each explain 2 percent of unique variance in burnout. Overcommitment, problem-solving pondering, and distraction explain 1 percent of variance only.

In

Table 12, we present results of the relative weight analysis predicting psychosomatic complaints. In total the ten work-related rumination constructs explain 26 percent of variance in psychosomatic complaints. Emotional irritation, affective rumination, inability to recover are the strongest predictors. Emotional irritation alone explains approximately 9 percent of variance (a third of the variance explained by all predictors). Affective rumination uniquely explains 6 percent of variance in psychosomatic complaints. Inability to recover and overcommitment explain 3 and 2 percent of unique variance in psychosomatic complaints, respectively. Negative work reflection, cognitive irritation, and distraction explain less than 2 percent of unique variance in psychosomatic complaints. Psychological detachment, problem-solving pondering, and positive work reflection explain less than 1 percent of unique variance in psychosomatic complaints. Overcommitment, problem-solving pondering, and distraction explain 1 percent of variance only.

In

Table 13, we present results of the relative weight analysis predicting satisfaction with life. In total the ten work-related rumination constructs explain 18 percent of variance in satisfaction with life. Positive work reflection and emotional irritation emerge as the strongest predictors. Positive work reflection alone explains approximately 6 percent of variance (a third of the variance explained by all predictors). Emotional irritation explains 5 percent of unique variance in satisfaction with life. Overcommitment, affective rumination, and inability to recover explain approximately 1 percent of unique variance in satisfaction with life. Psychological detachment, problem-solving pondering, negative work reflection, cognitive irritation, and distraction explain less than 1 percent of unique variance in satisfaction with life.

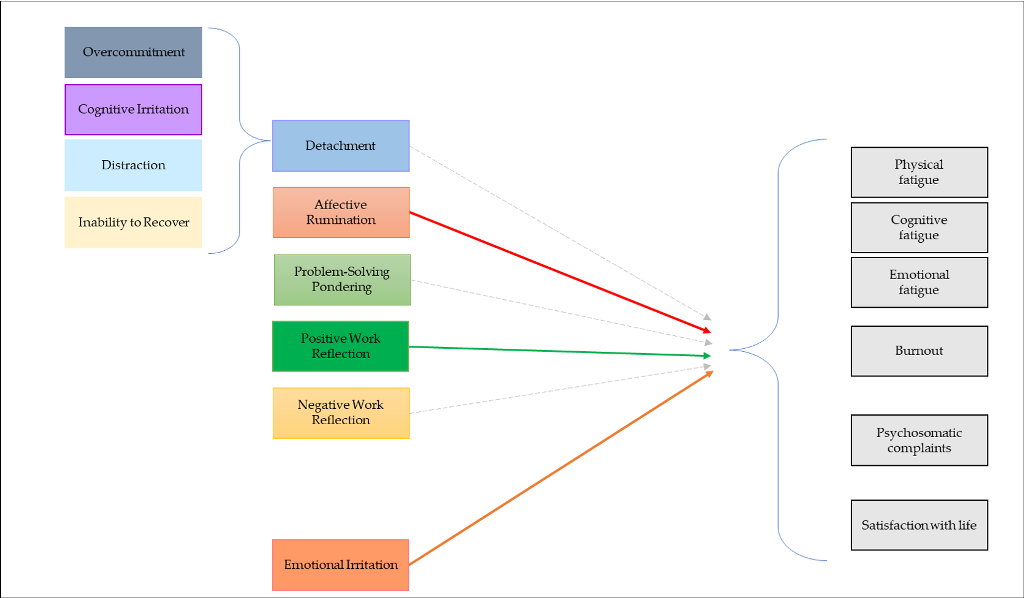

In

Figure 4 provide a graphical summary of the RWA across outcomes. The relative weight analyses for indicators of well-being as criteria provide a precise description of the relative relevance of each work-related rumination construct studied here and help prioritize and select constructs from a pragmatic perspective with predictive validity as the core criterion. Although the specific results across the six outcomes vary considerably, there are several findings that replicate consistently across outcomes. First, emotional irritation is consistently among the strongest unique predictors across outcomes explaining one fourth to one third of the variance explainable by the ten work-related rumination constructs. Albeit effects are less pronounced and less consistent, the same applies to affective rumination and inability to recover. Both constructs emerge as the second or third best predictor of the six outcomes. Negative work reflection and positive work reflection tend to contribute uniquely to the prediction of outcomes, supporting these constructs as valuable aspects within the famous five facets of work-related rumination. Of note, when it comes to predicting positively connoted aspects of employee well-being positive work reflection plays a vital role. OVC explains less than 2 percent of unique variance and hence does not add considerably to the prediction of the six outcomes considered when considering other constructs tapping into inability to unwind from work. A similar pattern emerges for psychological detachment and distraction. This finding is notable when keeping in mind that psychological detachment has been studied more extensively than any of the other constructs. We suggest that the common theme of inability to unwind from work (as captured in psychological detachment, cognitive irritation, distraction as conceptualized in the WRRQ, and inability to recover as conceptualized in the FABA) is relevant for predicting fatigue, burnout, psychosomatic complaints, and satisfaction with life. However, inability to recover as a specific operationalization of this underlying theme captures large portions of variance relevant to predicting key indicators of employee well-being and health. A closer look at the bivariate correlations of psychological detachment versus inability to recover with the outcome variables in

Table 4 is consistent with the findings from the relative weight analyses: Inability to recover yields considerably stronger links to all indicators of employee well-being and health.