Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

31 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Results

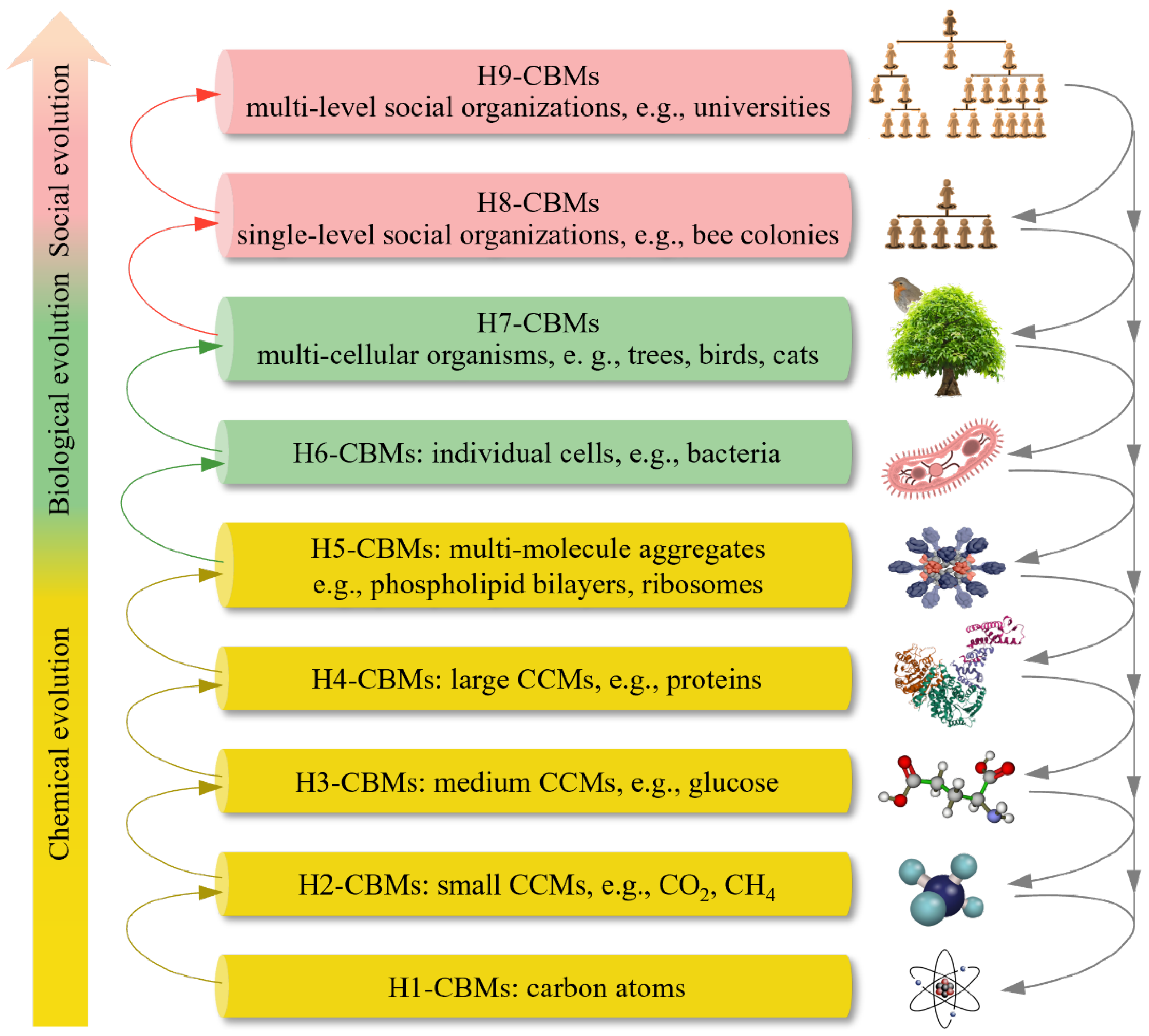

1.1. Hierarchies and Functions of CBMs

1.2. Three Axioms

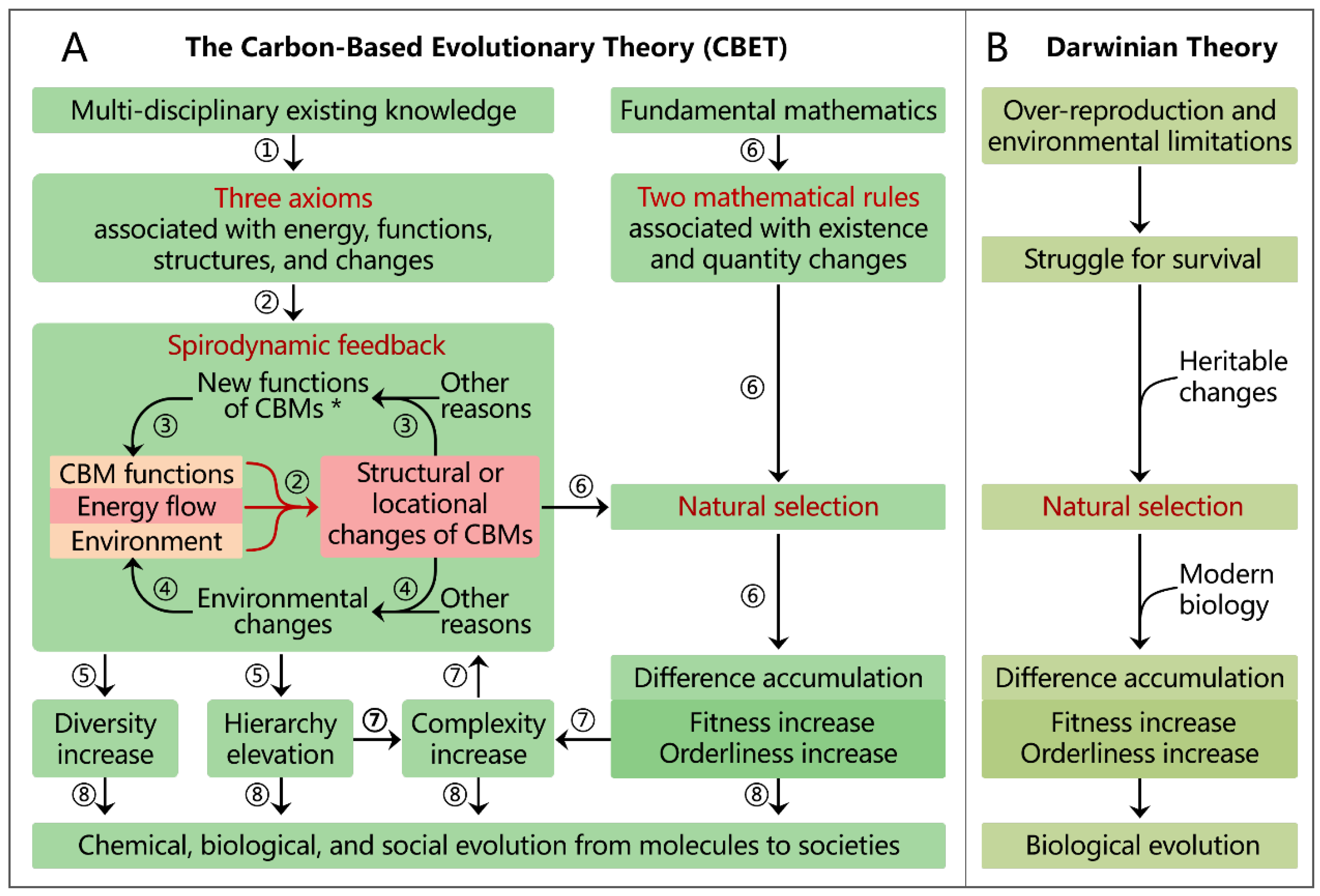

1.3. Reasoning Steps of CBET

1.4. Explanation of Life's Origin

1.5. Clarification of Misunderstandings

1.6. Validation of CBET

1.7. Mathematical Formalization and Modeling

2. Discussion

2.1. Significance in Natural Sciences

2.2. Significance in Social Sciences

2.3. Limitations of CBET

2.4. Outlook

3. Methods

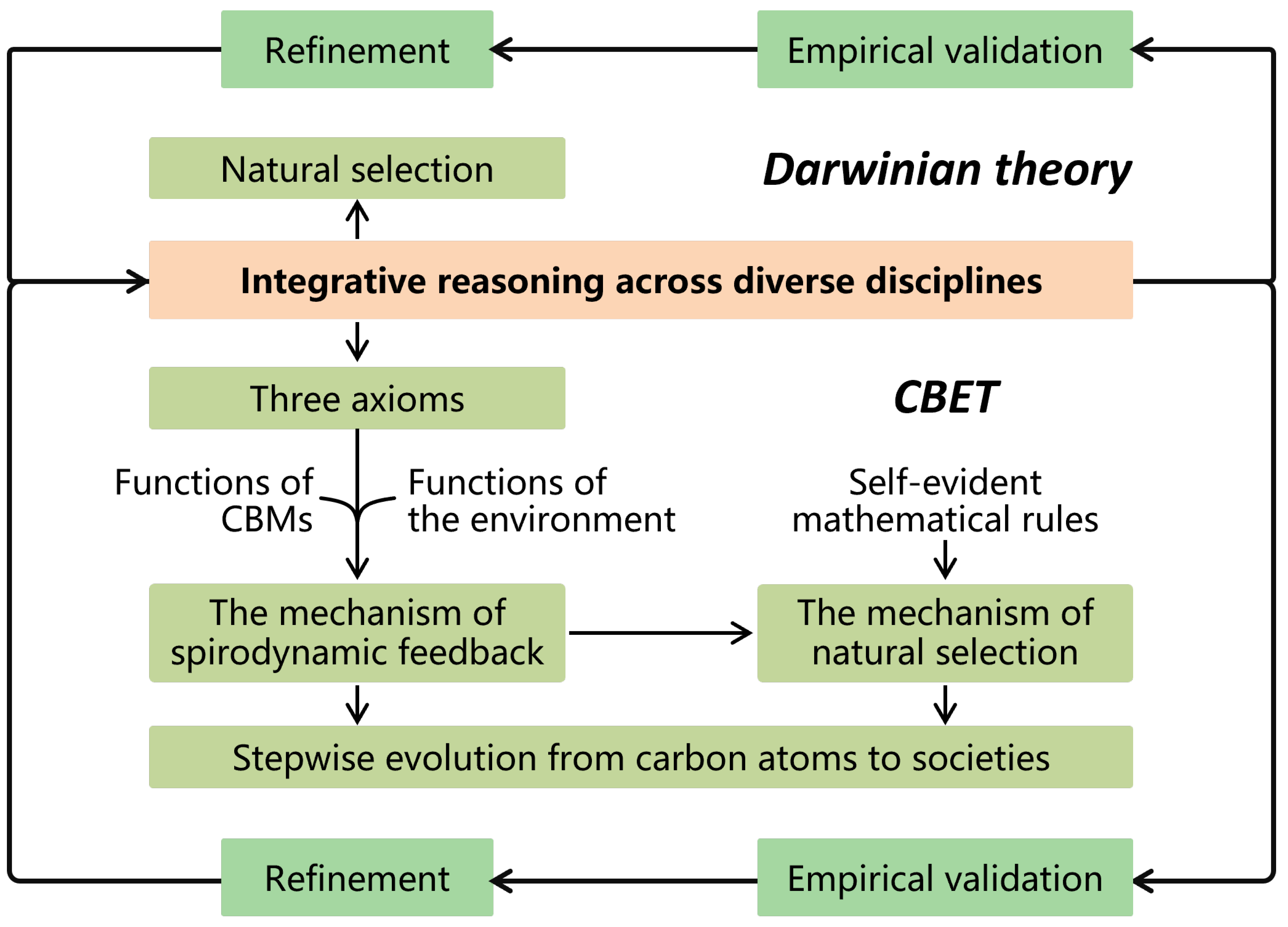

3.1. Reasoning, Validation, and Refinement of CBET

3.1.1. Methodology of CBET

3.1.2. Integrative Reasoning of CBET

- ✧

- Like the core concept of ‘organism’ in biological evolution, carbon-based material (CBM)’ is an explicit and precise core concept for the study of the entire CBM evolution.

- ✧

- Other concepts, such as ‘molecule’, ‘system’, ‘material’, ‘gene’, or ‘entropy’, are less suited to unify carbon atoms, organic molecules, organisms, and societies. They are therefore less suited to be the core concept for the study of the entire CBM evolution.

- ✧

- CBET integrates various key factors, such as hierarchy, energy, structures, functions, environmental factors, feedback, natural selection, competition, collaboration, water, genes, epigenetics, neutral mutations, Earth’s features, and carbon atomic structure.

- ✧

- The factors above are concrete and known to be crucial for CBM evolution and directly associated with CBM evolution. Thus, the selection of these key factors is important for CBET to provide a direct and explicit explanation for CBM evolution.

3.1.3. Empirical Validation of Spirodynamic Feedback

- They require energy flow, which may originate from the environment, the target material itself, or their interactions;

- They are influenced by environmental factors;

- They rely on the functions of the relevant material, which are in turn partially determined by its structure;

- They demonstrate that structural changes can generate new functions not present in the original forms. These emergent functions can initiate further structural changes, thereby establishing a spirodynamic feedback loop that, in some cases, leads to serial hierarchical elevation—as illustrated by Facts 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, 22, and 25;

- They show that structural changes can influence or alter the environment, which may also be modified by other factors. Such environmental changes can, in turn, contribute to subsequent rounds of structural changes or further engage in the spirodynamic feedback process—as evidenced by Facts 1, 3, 5, 18, 20, and 27.

- ✧

- Question 1: Do you think all structural changes in molecules, organisms, or social organizations are driven by or rely on energy flow?

- ✧

- Question 2: Do you think many structural changes in molecules, organisms, or social organizations are affected by the environment?

- ✧

- Question 3: Do you think some functions of molecules, organisms, or social organizations are important to maintain or change the structures of themselves?

- ✧

- Question 4: Do you think some functions of molecules, organisms, or social organizations are partially determined by their structures?

- ✧

- Question 1: Can you find any evidence able to falsify any viewpoints of the three axioms or the two mathematical rules given in this article?

- ✧

- Question 2: Can you find any evidence able to falsify the reasoning or viewpoints of CBET given in this article?

- ✧

- All three AI tools and five professors reported that they could not find robust evidence to falsify the viewpoints.

3.1.4. Empirical Validation of Natural Selection

- ✧

- ✧

- In chemical evolution, molecular populations undergo natural selection in those organic chemical reactions with multiple possible products, where the molecules that are easily formed and difficult to degrade (i.e., with a high formation-to-degradation ratio) tend to accumulate in greater quantities than those that are difficult to form and easily degraded.

- ✧

- In social evolution, companies or schools undergo competition and selection where those with the formation-to-dissolution ratio >1 demonstrate progressive accumulation, consistent with the natural selection dynamics.

- ✧

- The two mathematical rules of natural selection are explicit and self-evident. They were deduced by fundamental mathematics (See Equation 1 in the main text). They are universally applicable to all molecules, organisms, and social organizations.

- ✧

- When an asteroid impact causes extinction, the cumulative formation of the affected species throughout its evolutionary history becomes equal to its cumulative degradation at the extinction moment. This satisfies the Quantity-Existence rule.

- ✧

- For a company, Equation 1 does not represent the relationship between the company’s economic income and expenditure and its survival. Instead, it indicates the relationship between the number of establishments and closures of a specific type of company and the existing quantity of that type of company.

- ✧

- For a country, Equation 1 does not represent the relationship between its net economic income and its survival. Instead, it indicates the relationship between the number of new formations and dissolutions of a specific type of country (e.g., slave-holding countries) and the existing number of that type of country.

3.1.5. Refinement of CBET

- ✧

- The CBET was iteratively refined based on validation results, leading to improvements across multiple dimensions to strengthen the theory’s coherence, rigor, clarity, and explanatory power. These included redefining the hierarchies of CBMs, reformulating the core axioms and mechanisms, streamlining the reasoning steps, updating the mathematical formulations, and redesigning the explanatory figures.

- ✧

- The core components of CBET—including its nine hierarchies of CBMs, eight reasoning steps, three axioms, and two mechanisms—have been iteratively refined for clarity and accessibility, and all elusive concepts are excluded from the theory. An online test conducted by the authors showed that 33 out of 35 undergraduates from Foshan University successfully grasped the core components of CBET within a one-hour session.

- ✧

- Additionally, as shown in the main text, multiple sentences in the definitions of the three axioms and two mechanisms in CBET use the words like ‘some, many, partially, or can’, rather than ‘all’ or ‘must’, so that they allow exceptions.

3.2. Comparison of CBET to other theories

3.2.1. Compared to Theories in Chemistry

- ✧

- Similarity:

- ✧

- Distinction:

- •

- Oparin's theory is limited to chemical evolution and the description of the possibility rather than revealing the underlying mechanisms and mathematical rules.

- •

- CBET applies to chemical, biological, and social evolution, and reveals the underlying mechanisms and mathematical rules of natural selection as well as chemical, biological, and social evolution.

- ✧

- Similarity:

- ✧

- Distinction:

- •

- RWH posits that self-replicating RNA molecules were the crucial, foundational step for life’s origin, acting as both the primary information carrier and catalyst. In contrast, CBET argues that such self-replicating macromolecules are exceedingly rare in nature. Instead, CBET proposes that life originated from the collaborative interactions of diverse molecules, where no single type of molecule is granted primacy. To date, though some RNA molecules can catalyze their degradation, no RNA molecules that can catalyze their replication have been identified.

- •

- RWH is primarily a theory of early biological evolution, focusing on the transition from prebiotic chemistry to the first living systems. In contrast, CBET presents itself as a universal framework, aiming to unify the mechanisms behind not only chemical and biological evolution but also social evolution, tracing a continuous path from carbon atoms to human civilizations.

- •

- RWH is grounded in the functional capabilities of RNA itself—specifically, its ability to replicate and catalyze reactions. In contrast, CBET introduces two overarching mechanisms: "spirodynamic feedback," which drives the hierarchical elevation and diversification of CBMs, and "natural selection," which shapes these changes based on fitness defined as a formation-to-degradation ratio.

3.2.2. Compared to Theories in Physics

- ✧

- Similarity:

- ✧

- Distinction:

- •

- Prigogine assumed that the still crystal-like orderliness in thermodynamics results from the same mechanism with biological and social orderliness, while CBET recognizes that the orderliness in thermodynamics is different from biological orderliness and they result from different mechanisms.

- •

- Prigogine interpreted orderliness and complexity with only a few abstract and elusive concepts (e.g., entropy), while CBET explains the mechanisms behind the natural increases in the orderliness and complexity of molecules, organisms, and social organizations with diverse concrete and explicit concepts across multiple disciplines (e.g., energy, structures, functions, feedback, and natural selection).

- •

- Prigogine highlighted self-organization and neglected the role of natural selection, while CBET highlights natural selection and highlights both functions of the target materials and the environmental influence.

- •

- Prigogine did not highlight the unique functions of carbon atoms and other CBMs, while CBET highlights the unique functions of CBMs.

- ✧

- Similarity:

- ✧

- Distinction:

- •

- FEP uses abstract concepts (e.g., entropy, surprise) and thus does not explicitly explain the evolution of CBMs, while CBET provides explicit explanation of the mechanisms behind the evolution of CBMs using concrete concepts (e.g., energy, structures, functions, feedback, and natural selection).

- •

- FEP does not highlight the unique functions of carbon atoms and other CBMs, while CBET highlights the unique functions of CBMs.

- •

- FEP focuses on interpreting how a complex system achieves and maintains its complex functions, rather than addressing the origins of the complex system itself, while CBET addresses the origins of the complex system.

3.2.3. Compared to Darwinian Theory in Biology

- ✧

- Similarity:

- •

- Both Darwinian theory and CBET highlight the mechanism of natural selection. In this sense, CBET is an extension rather than a replacement of Darwinian theory.

- •

- Both Darwinian theory and CBET only provide a schematic rather than detailed account for the plausibility rather than inevitability of evolution mostly in a qualitative rather than quantitative manner.

- ✧

- Distinction:

- •

- Darwinian theory is confined to biological evolution and devoid of a coherent framework to integrate various evolutionary phenomena, while CBET applies to chemical, biological, and social evolution and integrates various evolutionary phenomena in a coherent framework.

- •

- Darwinian theory has not accounted for the origins of life and societies, while CBET provides a holistic explanation for the entire evolution of CBMs, which covers the origins of life and societies.

- •

- Darwinian theory cannot calculate the fitness of molecules, worker bees, and societies, while CBET can rationally calculate their fitness.

- •

- Darwinian theory does not highlight the unique functions of carbon atoms, while CBET highlights the unique functions of carbon atoms.

- •

- Darwinian theory reveals only the natural selection mechanism of evolution, while CBET reveals the natural selection mechanism that shapes the evolution and the spirodynamic feedback mechanism that drives the evolution. Thus, CBET is more powerful in accounting for evolutionary facts. Consequently, neutral mutations, epigenetic changes, and non-heritable traits, which cannot be integrated into Darwinian theory [2,4], can be well integrated into CBET. This makes CBET more consistent with modern biological findings.

- •

- CBET clarifies the mathematical rules of natural selection and refines ‘survival of the fittest' to ‘survival of the fit enough' to prevent literal misunderstanding. It denotes that a neutral or detrimental trait can exist provided that its carrier maintains net positive growth to persist. This provides a rigorous theoretical foundation for the widespread existence of neutral evolution and detrimental traits, aligning better with the reality revealed by genomics.

3.2.4. Compared to Relevant Social Theories

- ✧

- Similarity:

- ✧

- Distinction:

- •

- Spencer emphasized ‘survival of the fittest' in social competition and justified elimination, selfishness, and colonialism.

- •

- CBET accurately clarifies the mathematical rule of ‘survival of the fit enough', the natural balance between competition versus inclusiveness, and the natural balance between selfishness versus altruism, in natural selection.

- ✧

- Similarity:

- ✧

- Distinction:

- •

- MLS lists populations and species without close internal collaboration as hierarchies, while CBET defines that higher-hierarchy CBMs are formed through close collaboration of lower-hierarchy CBMs.

- •

- MLS focuses on altruistic behavior in biological evolution and explains them using the claim that natural selection exists at multiple levels. Furthermore, MLS has not revealed the mechanisms underlying natural selection and chemical, biological, and social evolution. In contrast, CBET develops a coherent theory interpreting the mechanisms behind natural selection and chemical, biological, and social evolution, and consequently explains the pervasive altruistic behavior and other important phenomena in CBM evolution.

- •

- MLS does not highlight the unique functions of carbon atoms and other CBMs. CBET highlights the unique functions of CBMs.

- ✧

- Similarity:

- ✧

- Distinction:

- •

- CST uses abstract models and focuses on the emergence of new functions, active adaptation to the environment, and modeling the current complex systems, while CBET interprets complexity with concrete and explicit concepts and focuses on revealing the mechanisms behind the evolution.

- •

- CST has not revealed the underlying mechanisms of chemical, biological, and social evolution with concrete and explicit concepts.

- •

- CST does not highlight the unique functions of carbon atoms and other CBMs, while CBET highlights the unique functions of CBMs.

3.2.5. Conclusions and Discussion

- ✧

- While some prior theories share partial similarities with CBET, none articulates the underlying mechanisms and mathematical rules of natural selection, as well as chemical, biological, and social evolution, using concrete, empirical concepts under a coherent theoretical framework. CBET distinguishes itself by integrating concrete concepts, mathematical rules, and interdisciplinary empirical evidence to illuminate the mechanisms driving the stepwise chemical, biological, and social evolution. This systematic approach bridges gaps left by prior theories, offering a novel and holistic perspective on the CBM world and on us.

- ✧

- Previous evolutionary theories were mainly based on a few factors, such as natural selection, entropy, free energy, self-organization, or dissipative structure, some of which are incomprehensible to many common readers. Additionally, few evolutionary theories have mentioned that functions of carbon atoms and other CBMs are crucial to evolution. In contrast, CBET integrates numerous concrete comprehensible factors, such as energy, structures, functions, information pathways, genetics, epigenetics, natural selection, carbon atoms, organic molecules, cells, organisms, and social organizations, into a unified framework.

- ✧

- Previous evolutionary theories often neglected or denied the role of natural selection [3,28,36,37,38,43] and explained CBM evolution using a single principle, such as Schrödinger's negative entropy notion of dissipating entropy into the environment [44], self-organization in Prigogine's dissipative structure theory [36], the constructal law [45], the maximum entropy production hypothesis [46], or the free energy principle [38]. In contrast, CBET uses three axioms along with two mechanisms (namely spirodynamic feedback and natural selection). This contrasts with previous studies, which

- ✧

- Some other evolutionary studies highlight the hierarchies of CBMs [41]. They have categorized molecules, cells, organs, and ecosystems into different hierarchies, and these studies have not deduced the spirodynamic feedback mechanism that drives stepwise evolution from carbon atoms to societies. In contrast, in CBET, organs are defined as components of individual organisms, whereas ecosystems are regarded as a kind of environment, and CBET has derived the spirodynamic feedback mechanism.

3.3. Mathematical Formulation of CBET

3.3.1. Equations of the Three Axioms

- ✧

- The Driving-Force Axiom (i.e., energy flow drives structural or locational changes in the target material under the modulation of the material and the environment)

- ✧

- The first core tenet of the Environment-Influence Axiom (i.e., environmental factors, which can act as the external cause, influence structural changes of the target material)

- ✧

- The third core tenet of the Structure-Function Axiom (i.e., material's functions, which can act as the internal cause, influence structural changes of the target material)

3.3.2. Equations of Spirodynamic Feedback

3.3.3. Equations of Natural Selection

3.4. Mathematical Modeling of CBET

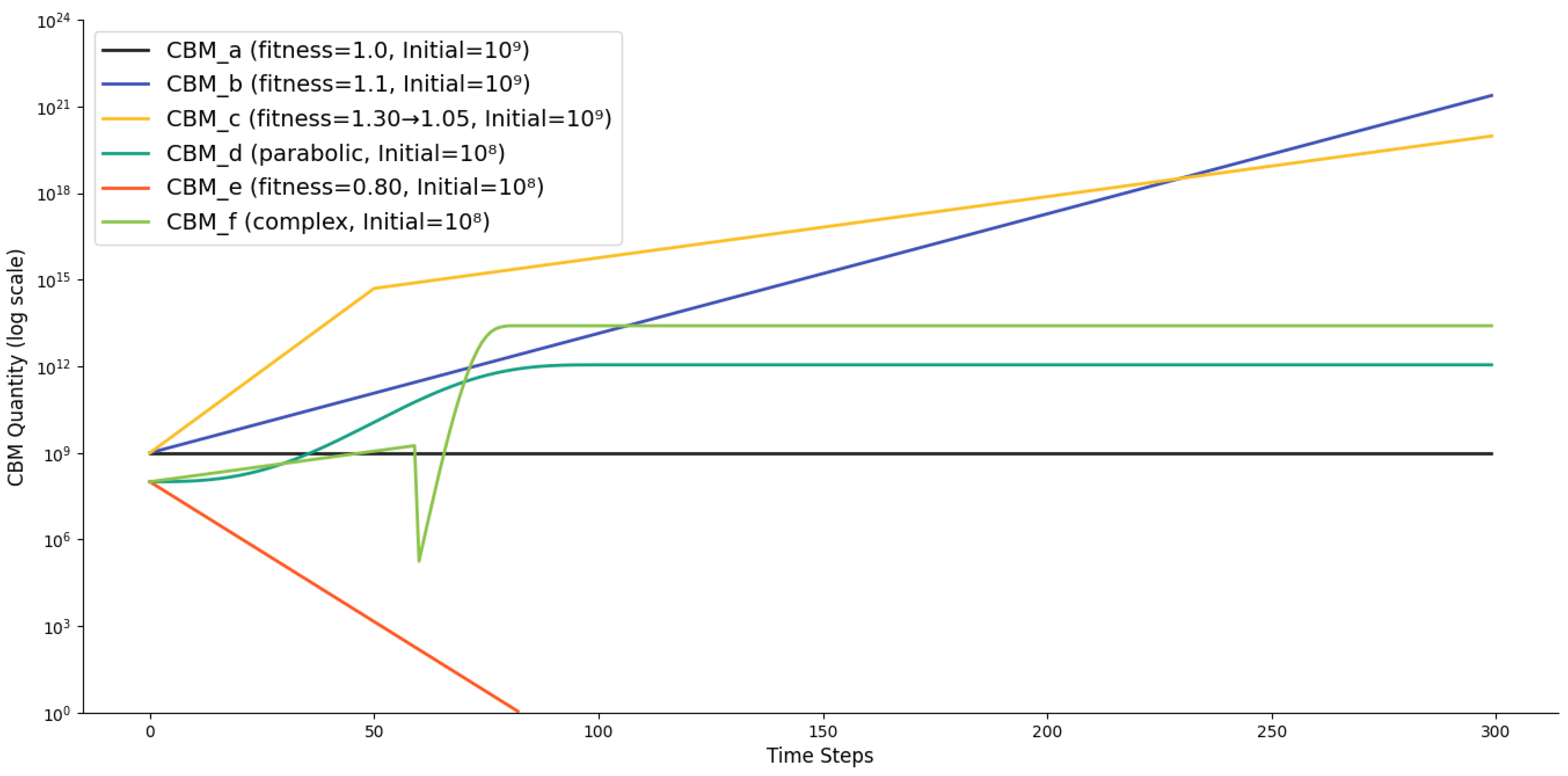

3.4.1. Modeling of the Effect of Natural Selection

3.4.1.1. Fitness Function Definitions

- CBM_a: Constant baseline fitness,

- CBM_b: Constant exponential growth,

- CBM_c: Stepwise decrease in fitness.

- CBM_d: Parabolic growth and stabilization.

- CBM_e: Constant fitness leading to population decline,

- CBM_f: Complex pattern simulating a catastrophic crash followed by recovery.

3.4.1.2. Core Evolution Equation and Simulation Setup

- is the quantity of CBM at time step .

- is the fitness value of CBM at time step .

- CBM_a, CBM_b, CBM_c:

- CBM_d, CBM_e, CBM_f:

3.4.1.3. Modeling Results

3.4.2. Modeling of the Possibility of Life’s Origin

3.4.2.1. Background

3.4.2.1.1. Roles of Spirodynamic Feedback

- ✧

- H2-CBMs → H3-CBMs. Chemically, some H2-CBMs can spontaneously absorb energy (e.g., heat) from certain energy flow sources (e.g., sunlight) on Earth. The absorbed energy and some functions of H2-CBMs—such as the reactivity of CO2 with H2O and the reactivity of CH4 with NH3—collectively transform H2-CBMs into diverse H3-CBMs through organic chemical reactions [47]. The prebiotic chemical synthesis of various H3-CBMs, such as amino acids, nucleotides, and monosaccharaides, has been validated in laboratories [4,5,6,20,21,23], and supported by the fact that myriad distinct H3-CBMs have been identified from meteorites [48].

- ✧

- H3-CBMs → small H4-CBMs. Likewise, chemically, many H3-CBMs can spontaneously absorb energy from certain energy flow sources on Earth. The absorbed energy and some functions of H3-CBMs—such as the one that some H3-CBMs have two or more active function groups—collectively transform H3-CBMs into diverse small H4-CBMs through organic chemical reactions. Studies have shown that high pressure, certain inorganic molecules like boric acids, and certain H3-CBMs—such as N-phosphoryl amino acids—can facilitate the abiotic synthesis of some small H4-CBMs, like short proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and myriad heteropolymers—namely those hybrid macromolecules incorporating residues of multiple types, such as macromolecules bearing both amino acids and nucleotide residues [2,5,6,23,49].

- ✧

- Small H3-CBMs → large H4-CBMs. Likewise, chemically, small peptides can form larger peptides in the same chemical way. Thus, through intermediate steps, amino acids can indirectly form medium or large proteins, although amino acids inefficiently form large proteins directly [49]. Likewise, chemically, other medium or large H4-CBMs, including various heteropolymers, can also be formed through various intermediate steps.

- ✧

- H4-CBMs → H5-CBMs (MMAs) and MMA clusters. In physics and chemistry, some H4-CBMs have the function of transforming into H5-CBMs (multiple molecule aggregates, MMAs), such as virus-like particles or water-in-oil emulsion, through physical and chemical reactions [50]. MMAs can further form MMA clusters through physical and chemical reactions. The energy provided by the wind, rain, lightning, and solar evaporation and some functions of H4-CBMs, such as the interaction among certain proteins through hydrogen bonds, can drive the formation of myriad MMAs and MMA clusters.

- ✧

- MMA clusters → Life structures. Chemically, many proteins generated through abiogenesis are enzymes and have certain catalysis activities. They, along with diverse H3-CBMs (e.g., glucose, nucleotides, amino acids), can thus form diverse MMAs and MMA clusters with certain metabolic functions, such as catalyzing the random formation of various H4-CBMs without fixed sequences, catalyzing the formation of certain H4-CBMs (e.g., RNA or DNA) according to certain sequences (which represent certain information), and catalyzing the degradation of certain H3-CBMs or H4- CBMs, etc. The formation of these metabolic MMAs and MMA clusters, in turn, could facilitate the formation of MMAs and MMA clusters through their catalysis activities or metabolic functions. Various metabolic MMAs, such as polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) systems for DNA synthesis according to certain sequences, have been widely applied in laboratories. Through stochastic processes, an exceedingly rare fraction of these clusters eventually achieved the complex function of reproduction, becoming the first life structures (H6-CBMs).

3.4.2.1.2. Roles of Natural Selection

- ✧

- Before life's origin, as given in Section 1.4, natural selection shaped the formation-degradation cycles of MMA clusters towards life's origin.

- ✧

- After life's origin, as given in Section 1.4, life structures are advantageous over non-replicating MMA clusters in natural selection, and life structures can be increasingly advantageous over non-reproductive MMA clusters in natural selection.

3.4.2.1.3. The Atmosphere-Origin Hypothesis

- ✧

- ✧

- The Atmosphere-Origin Hypothesis is grounded in the established understanding that the early Earth was too hot—with its surface in the form of liquid magma—to retain surface water. Consequently, the early (Hadean) atmosphere differed markedly from today’s, characterized by high temperatures, pressure, and water concentration [15,22]. Due to frequent volcanic activity on the early Earth, the early atmosphere contained high concentrations of volcanic ash, along with abundant reactive gases such as CO2, H2, and NH3, as well as variable winds and frequent heavy rains [6,15]. As a result, the early atmosphere, which is usually termed ‘magma-ocean atmosphere’ or ‘steam atmosphere’, resembled a floating ocean, with darkness prevailing near its base.

- ✧

- The early atmosphere—shared advantages with hydrothermal vents and volcanic lakes: abundant energy flow, water, and mineral catalysis (via suspended volcanic ash that enhances reaction yields)—was a more conducive environment for life’s origin than hydrothermal vents and volcanic lakes for the following five reasons, which could greatly enhance the plausibility of life’s origin on Earth.

- •

- Time. The early atmosphere sustained high pressure and abundant water for about 0.2 billion years before hydrothermal vents and volcanic lakes emerged.

- •

- Materials. The early atmosphere contained more abundant reactive gases such as CO2, H2, and NH3 than hydrothermal vents and volcanic lakes.

- •

- Energy flows. The early atmosphere held more diverse energy flows, such as solar radiation, lightning, and various forms of radiation, which led to vast planetary-scale spaces for the synthesis of H3-CBMs and H4-CBMs.

- •

- Spatial differences. The thermal and pressure gradients of the early atmosphere across heights and altitudes facilitated the formation, storage, and accumulation of organic molecules.

- •

- Formation of MMA clusters. The early atmosphere could naturally generate vast numbers of dynamic aerosol particles and droplets, driven by wind, dust, and evaporation-condensation cycles. These aerosol particles and droplets effectively constituted innumerable MMA clusters, providing endless trial-and-error opportunities for the emergence of life structures.

- •

- Global mixing. Efficient global mixing of MMAs and MMA clusters via wind facilitated the renewal of MMAs and MMA clusters in the early atmosphere.

3.4.2.2. Initial Setup and Time Segmentation

- Initial amount of H1-CBMs on Earth: Changes are not considered (due to the chemical instability of uncombined H1-CBMs under high temperatures on early Earth and their significantly smaller quantity compared to H2-CBMs).

- Initial amount of H2-CBMs on Earth: NH2⁰ = 10²⁴ mol

- Initial amount of H3-CBMs and higher-hierarchy CBMs on Earth: 0

-

Time Segments:

- ○

- 1st 10 million years: 0 – 10 Myr

- ○

- 2nd 10 million years: 10 – 20 Myr

- ○

- 3rd 10 million years: 20 – 30 Myr

3.4.2.3. Consumption of H2-CBMs

- According to the CBET framework, H2-CBMs were consumed to form H3-CBMs, which can further to form H4-CBMs, and the formation was driven by the synergetic action of energy flow, functions of H2-CBMs and H3-CBMs, and influence of the environment.

- The formation of H3-CBMs and H4-CBMs could be accelerated due to the catalysis function of some H3-CBMs and higher-hierarchy CBMs (an effect of the spirodynamic feedback mechanism), and thus the consumption of H2-CBMs could be accelerated during the first thirty million years (Myr).

- H2-CBMs can be generated through the degradation of H3-CBMs and higher-hierarchy CBMs, and thus the quantity of H2-CBMs could be relatively stable after the first thirty Myr.

- 0–10 Myr: 99.8% → Remaining 0.998

- 10–20 Myr: 99.0% → Remaining 0.990

- 20–30 Myr: 90.0% → Remaining 0.900

- H2-CBMs are assumed to remain relatively constant thereafter (steady state).

3.4.2.4. Growth Calculation of H3-CBMs

-

During the first 10 Myr

- ○

- Reduction of H2-CBMs: ΔNH2 = 10²⁴ × (1 - 0.998) = 2 × 10²¹

- ○

- Converted to H3-CBMs (each H3-CBM is assumed to contain 10 carbon atoms, and 5% of H3-CBMs further formed H4-CBMs):

-

During the second 10 Myr

- ○

- ΔNH2= 10²⁴ × (0.998 - 0.990) = 8 × 10²¹

- ○

- Converted to H3-CBMs:

-

During the third 10 Myr

- ○

- ΔNH2 = 10²⁴ × (0.990 - 0.900) = 9 × 10²²

- ○

- Converted to H3-CBMs:

- Cumulative H3-CBMs (at 30 Myr)

- H3-CBMs are assumed to remain relatively constant thereafter (steady state).

3.4.2.5. Growth Calculation of H4-CBMs

- Each small H4-CBM is assumed to contain 15 H3-CBM residues.

- 5% of H3-CBMs are consumed to form small H4-CBMs, with 97% retained (3% of small H4-CBMs are consumed to form middle or large H4-CBMs), and thus at the end of the third 10 Myr, the quantity of small H4-CBMs:

- Each middle H4-CBM is assumed to contain 160 H3-CBM residues.

- 3% of small H4-CBMs are consumed to form middle H4-CBMs, with 98% retained (2% of middle H4-CBMs are consumed to form large H4-CBMs), and thus at the end of the third 10 Myr, the quantity of middle H4-CBMs:

- Each large H4-CBM is assumed to contain 600 H3 residues.

- 2% of middle H4-CBMs are consumed to form large H4-CBMs, and thus at the end of the third 10 Myr, the quantity of large H4-CBMs

- Although the total numbers of small, middle, and large H4-CBMs after the end of the third 10 Myr are assumed to be constant, they were formed and degraded simultaneously at largely equal rates after that time.

3.4.2.6. Growth Calculation of MMA Clusters

- Participation probability: 10% (10 in 100)

- Each MMA cluster is assumed to contain 1,000 large H4-CBMs molecules (Other materials such as water are assumed to be abundant for the formation of MMA clusters)

- Total MMA clusters:

- MMA clusters are assumed to be renewed (e.g., addition, removal, or alteration of a macromolecule within a cluster) on average every second.

- Annual renewal cycles: 365 × 24 × 60 × 60 = 15,156,000

- Annual production:

3.4.2.7. Calculation of Life Origin Events

3.4.2.8. Conclusion

3.5. Questions and Answers

3.5.1. Is CBET Falsifiable

3.5.2. What Is the Most Revolutionary Aspect of CBET

3.5.3. Why Is CBET Not Derived from Novel Experiments

- ✧

- Experiments, which are suitable to address specific issues, are unsuitable to derive the broad-scoped theory of CBET, which addresses the changes of countless molecules, organisms, and social organizations.

- ✧

- Instead, CBET can be established through integrative reasoning from vast established knowledge and empirical validation via falsification against countless molecules, organisms, and social organizations. This process effectively validated CBET against a myriad of facts across diverse disciplines. Likewise, Darwinian theory was established through the same methodology rather than by a few experiments.

- ✧

- Since Darwin’s era, researchers have accumulated extensive knowledge on molecules, organisms, and social systems. Over more than three decades, the authors have synthesized this vast body of established knowledge to derive, validate, and refine CBET to explain the mechanisms underlying chemical, biological, and social evolution, and this synthetic work became promising when they adopted carbon-based materials as the core concept in 2018.

3.5.4. Why Is CBET Easy to Understand

- ✧

- As shown in Figure 2, while CBET is significantly more complex and harder to understand than Darwinian theory, it is more accessible than quantum mechanics and astronomy.

- ✧

-

CBET itself can be easy to understand for two reasons:

- •

- Carbon-based materials, ranging from carbon atoms to social organizations, are substances that humans can directly observe with naked eyes or instruments. They follow relatively simple and understandable laws, as they are neither obscure substances below the atomic level nor esoteric ones above the galactic level.

- •

- The evolutionary mechanisms unveiled by CBET are shared by molecules, organisms, and social organizations. Therefore, these mechanisms and their underlying mathematical rules apply to social organizations—which are familiar to the general public—making them easy to comprehend.

- ✧

-

CBET has been derived towards an explicit theory, according to the principle that scientific explanations should be as explicit as possible.

- •

- The authors have spent over three decades employing concrete and understandable terms (e.g., structure, function, change, energy, carbon atoms, and reproduction), rather than elusive concepts, to derive and describe CBET.

- •

- Again, CBET is like the first aerial photograph of a maze, which clearly shows the correct path from its entrance to its exit.

3.5.5. Does CBET Oversimplify the Behavior of Countries

- ✧

- CBET only describes certain not all aspects of countries.

- ✧

- CBET is inclusive in its statement. For example, its statement that structures partially determine functions allows the influence of the history, culture, and the environment on the functions of countries.

- ✧

- CBET is applicable to CBMs at diverse hierarchical levels because its key concepts of CBMs, energy, changes, structures, functions, and environments—apply universally to diverse hierarchies and can become increasingly complex as hierarchies are elevated.

- ✧

- A country can emerge through an evolutionary trajectory where carbon atoms → small carbon-containing molecules → medium carbon-containing molecules → large carbon-containing molecules → multiple molecular aggregates → cells → multicellular organisms → humans → tribes → tribal alliances → countries.

- ✧

- A country's behavior and evolution are shaped by both natural and social environments, relying on energy flow as well as its physical, chemical, biological, and social functions. Its social functions include political, cultural, legislative, religious, and military functions.

- ✧

- Reforming the structure of a country can generate new functions, enabling more or less adaptation to environmental changes.

- ✧

- The facts above collectively demonstrate that CBET neither oversimplifies country's behavior nor ignores political or cultural factors.

3.5.6. Can CBET Describe CBM Evolution Quantitatively

- ✧

- No, and such quantification is unnecessary and theoretically unjustified.

- ✧

- CBET is in part derived from principles across diverse disciplines by abstracting away their quantitative parameters to render them applicable to all molecules, organisms, and societies. Consequently, CBET provides a qualitative description of the relationships among environmental factors, energy flow, structures, and functions. These relationships vary profoundly among different hierarchies, materials, and environments, making the unified quantitative framework impractical and theoretically unjustified. For example, a quantitative description of the dynamic process of carbon combustion into carbon dioxide would most likely prove inapplicable to describe the development of social organizations.

3.5.7. Can CBET Explain the Inevitability of Life’s Origin

3.5.8. Can CBET Reveal the Details of CBM Evolution

3.5.9. Can CBET Predict Anything

- CBET predicts that many organisms (e.g., humans) and social organizations (e.g., companies) can sustain numerous detrimental traits, as CBET clarifies that these organisms or social organizations can exist on Earth as long as their cumulative formation exceeds their cumulative degradation.

- CBET predicts that sustainable social organizations typically exhibit a natural balance between competition and inclusiveness, as well as between selfishness and altruism, as these balances are inherent outcomes of the spirodynamic feedback and natural selection mechanisms underlying the evolution of social organizations.

- CBET predicts that self-replicating macromolecules—long sought in studies on the origin of life29—are likely rare in nature and were not a crucial prerequisite for life's emergence. This is because the complex function of self-replication, involving information encoding, reading, and multi-step synthesis, typically requires a structural complexity far beyond that of a single macromolecule, and the reproduction function of life emerged on Earth due to collaboration of various molecules rather than the self-replication function of certain molecules.

3.5.10. Is CBET a Theory of Philosophy

- ✧

- CBET is grounded in empirical evidence and scientific principles, not philosophical reasoning.

- ✧

- Its three axioms are derived from well-established knowledge in physics, chemistry, biology, and social sciences (e.g., principles from Newtonian mechanics, thermodynamics, heredity, and social change).

- ✧

- Its core mechanisms (spirodynamic feedback and natural selection) are reasoned from the three axioms, mathematical rules, and the observable functions of carbon-based materials (CBMs) and environments.

- ✧

- CBET is testable and falsifiable, which are hallmarks of scientific theories.

- ✧

- CBET's validity was explicitly tested against numerous facts spanning molecular, biological, and social phenomena.

- ✧

- The authors actively sought counterevidence through self-scrutiny, peer review, and AI-assisted analysis, adhering to scientific practice.

- ✧

- CBET does not rely on ‘a priori’ reasoning, metaphysical assumptions, or any specific school of philosophical thought.

- ✧

- Whereas philosophy also engages with broad concepts like 'hierarchy' and 'complexity', CBET distinguishes itself by explaining them through concrete, scientific concepts—such as energy flow and structural changes—within a coherent empirical framework.

- ✧

- Since CBET shares a broad scope with certain philosophical studies, it can act as a bridge between philosophy and science. This is particularly relevant in the mesocosmic world—the realm between atoms and the solar system, in contrast with the picocosmic world (below the atomic level) and the megacosmic world (beyond the solar system).

3.5.11. How Can AI Tools Support This Work

- ✧

- AI tools have significantly assisted in refining the expression of this article. For example, they suggested revising ‘total formation' to the more precise ‘cumulative formation' in the statement of the Quantity-Existence Rule.

- ✧

- AI tools have significantly assisted in the validation of CBET through their efficient seeking of counterevidence to challenge CBET.

- ✧

- The authors find themselves in a race against rapidly advancing AI tools in the development of this theory. It is highly plausible that AI could independently formulate a similar theory in the near future—even without referencing this article.

3.5.12. What Energy Flows Drive the Transitions of CBMs Across Hierarchies

3.6. Glossary

- ✧

- H1-CBMs: carbon atoms.

- ✧

- H2-CBMs: small carbon-containing molecules (e.g., CH4, CO2, HCN).

- ✧

- H3-CBMs: medium carbon-containing molecules (e.g., lysine, glucose).

- ✧

- H4-CBMs: large carbon-containing molecules (e.g., lipids, proteins, nucleic acids).

- ✧

- H5-CBMs: multi-molecule aggregates (e.g., phospholipid bilayers, cellulose microfibrils).

- ✧

- H6-CBMs: individual cells (e.g., bacteria, cells in animals).

- ✧

- H7-CBMs: multicellular organisms (e.g., pines, rabbits).

- ✧

- H8-CBMs: single-level social organizations (e.g., colonies, small companies).

- ✧

- H9-CBMs: multi-level social organizations (e.g., universities, armies, countries) - Higher-hierarchy CBMs and lower-hierarchy CBMs: they are defined by hierarchy comparison. For example, H6-CBMs are at a higher hierarchy relative to H5-CBMs but at a lower hierarchy relative to H7-CBMs. Higher-hierarchy are formed by lower-hierarchy CBMs and other materials through physical, chemical, biological, or social interactions.

- ✧

- Chemical Evolution The evolution from small to large carbon-containing molecules, and further to multi-molecule aggregates.

- ✧

- Biological Evolution The origin and evolution of life.

- ✧

- Social Evolution The origin and evolution of animal and human social organizations (e.g., colonies, tribes, countries).

- ✧

- The Quantity-Existence Rule: A material exists if its cumulative formation exceeds its cumulative degradation (‘survival of the fit enough’).

- ✧

- The Quantity-Change Rule: The quantity of a material increases if its formation-to-degradation ratio >1 and decreases if <1.

- ✧

- The Environment-Influence Axiom: The environment has the function to provide energy, constituent materials, and other conditions to influence structural changes of the target material, and the structural changes of the target material can in turn influence the environment.

- ✧

- The Structure-Function Axiom: For a material, its structure partially determines its functions, and its structural changes can generate new functions, and in turn, its functions (acting as the internal causes) are crucial for maintaining or altering its structure.

- ✧

- The Driving-Force Axiom: Qualitatively, energy flow drives structural or locational changes of the target material under the modulation of the functions of the material (as internal causes) and the environment (as external causes).

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species 1st edn (John Murray, 1859).

- Futuyma, D. J. & Kirkpatrick, M. Evolution 4th edn (Sinauer Associates, 2017).

- Chen, J. A new evolutionary theory deduced mathematically from entropy amplification. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2000, 45, 91–96. [CrossRef]

- Xie, P. The Aufhebung and Breakthrough of the Theories on the Origin and Evolution of Life (Science Press, 2014).

- Oparin, A. I. Chemistry and the origin of life. R. Inst. Chem. Rev. 2, 1–12 (1969).

- Fiore, M. Prebiotic Chemistry and Life's Origin (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2022).

- Nowak, M. A., Tarnita, C. E. & Wilson, E. O. The evolution of eusociality. Nature 466, 1057–1062 (2010).

- Birch, J. The Philosophy of Social Evolution (Oxford Univ. Press, 2017).

- Cowan, J. J. One of the first of the second stars. Nature 488, 288–289 (2012).

- Razeghi, M. The Mystery of Carbon: An Introduction to Carbon Materials (IOP Publishing, 2019).

- Heck, P.R.; Greer, J.; Kööp, L.; Trappitsch, R.; Gyngard, F.; Busemann, H.; Maden, C.; Ávila, J.N.; Davis, A.M.; Wieler, R. Lifetimes of interstellar dust from cosmic ray exposure ages of presolar silicon carbide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 1884–1889. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. H. et al. Exceptional preservation of an extinct ostrich from the Late Miocene Linxia Basin of China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 59, 229–248 (2021).

- Reichle, D. E. The Global Carbon Cycle and Climate Change 2nd edn (Elsevier, 2023).

- Seager, S. Exoplanet Habitability. Science 2013, 340, 577–581. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.E.; Altair, T.; Hermis, N.Y.; Jia, T.Z.; Roche, T.P.; Steller, L.H.; Weber, J.M. Chapter 4: A Geological and Chemical Context for the Origins of Life on Early Earth. Astrobiology 2024, 24, S76–76. [CrossRef]

- Olejarz, J.; Iwasa, Y.; Knoll, A.H.; Nowak, M.A. The Great Oxygenation Event as a consequence of ecological dynamics modulated by planetary change. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Benton, M.J. The Red Queen and the Court Jester: Species Diversity and the Role of Biotic and Abiotic Factors Through Time. Science 2009, 323, 728–732. [CrossRef]

- De Capitani, J., Mutschler, H. The long road to a synthetic self-replicating central dogma. Biochemistry 62(7), 1221–1232 (2023).

- Marchi, S.; Korenaga, J. The shaping of terrestrial planets by late accretions. Nature 2025, 641, 1111–1120. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Fu, S.; Ying, J.; Zhao, Y. Prebiotic chemistry: a review of nucleoside phosphorylation and polymerization. Open Biol. 2023, 13, 220234. [CrossRef]

- Nam, I., Lee, J. K., Nam, H. G. & Zare, R. N. Abiotic production of sugar phosphates and uridine ribonucleoside in aqueous microdroplets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 12396–12400 (2017).

- Dobson, C.M.; Ellison, G.B.; Tuck, A.F.; Vaida, V. Atmospheric aerosols as prebiotic chemical reactors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000, 97, 11864–11868. [CrossRef]

- Griffith, E.C.; Vaida, V. In situ observation of peptide bond formation at the water–air interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 15697–15701. [CrossRef]

- Trainer, M. Atmospheric Prebiotic Chemistry and Organic Hazes. Curr. Org. Chem. 2013, 17, 1710–1723. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-Q.; Ye, J.; Meng, J.; Li, C.; Costeur, L.; Mennecart, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Aiglstorfer, M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Sexual selection promotes giraffoid head-neck evolution and ecological adaptation. Science 2022, 376, 1067–+. [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, R. The Selfish Gene (Oxford Univ. Press, 1976).

- Low, D. Advantage of an epigenetic switch in response to alternate environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [CrossRef]

- Veigl, S.J.; Vasilyeva, Z.; Müller, R. Scientific-intellectual movements in the post-truth age: The case of the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. M., Chen, J. W. & Zivieri, R. Systematically challenging three prevailing notions about entropy and life. Qeios. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, D.M.; Rosenberg, S.M. What is mutation? A chapter in the series: How microbes “jeopardize” the modern synthesis. PLOS Genet. 2019, 15, e1007995. [CrossRef]

- Fine, J.L.; Moses, A.M. An RNA Condensate Model for the Origin of Life. J. Mol. Biol. 2025, 437, 169124. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, T. Reconsidering the logical structure of the theory of natural selection. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2014, 7, e972848–e972848. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.-C.; Chen, G.-W.; Yuan, X.-H.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, B.; Wang, M.-S.; Tang, H.; Hou, Y. Key for Hexagonal Diamond Formation: Theoretical and Experimental Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 2158–2167. [CrossRef]

- Stobart, C.C.; Moore, M.L. RNA Virus Reverse Genetics and Vaccine Design. Viruses 2014, 6, 2531–2550. [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, C.A., 3rd; Chuang, R.-Y.; Noskov, V.N.; Assad-Garcia, N.; Deerinck, T.J.; Ellisman, M.H.; Gill, J.; Kannan, K.; Karas, B.J.; Ma, L.; et al. Design and synthesis of a minimal bacterial genome. Science 2016, 351, aad6253–aad6253. [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I. Time, structure and fluctuation. Science 201, 777–785 (1978).

- Ramstead, M. J. D., Badcock, P. B. & Friston, K. J. Answering Schrödinger’s question: A free-energy formulation. Phys. Life Rev. 24, 1–16 (2018).

- Friston, K. The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 127–138. [CrossRef]

- Rudman, L.A.; Saud, L.H. Justifying Social Inequalities: The Role of Social Darwinism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 46, 1139–1155. [CrossRef]

- Stanford, P.K.; Sober, E.; Wilson, D.S. Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior. J. Philos. 2001, 98, 43. [CrossRef]

- Eldredge, N., Pievani, T., Serrelli, E. & Tëmkin, I. Evolutionary Theory: A Hierarchical Perspective (Univ. Chicago Press, 2016).

- Miller, J.H.; Page, S.E. Complex Adaptive Systems: An Introduction to Computational Models of Social Life; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2009; ISBN: .

- Sabater, B. Entropy Perspectives of Molecular and Evolutionary Biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4098. [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. What is Life (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012).

- Bejan, A. The principle underlying all evolution, biological, geophysical, social and technological. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2023, 381, 20220288. [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R.C. Maximum entropy production and plant optimization theories. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 1429–1435. [CrossRef]

- Borgnakke, C. & Sonntag, R. E. Fundamentals of Thermodynamics (Wiley, 2022).

- Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Gabelica, Z.; Gougeon, R.D.; Fekete, A.; Kanawati, B.; Harir, M.; Gebefuegi, I.; Eckel, G.; Hertkorn, N. High molecular diversity of extraterrestrial organic matter in Murchison meteorite revealed 40 years after its fall. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 2763–2768. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Bai, J.; Qiao, H. Prebiotic Peptide Synthesis: How Did Longest Peptide Appear?. J. Mol. Evol. 2025, 93, 193–211. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liu, A.; Li, X.; Miao, Z. Research progress on mRNA drug delivery strategies in the nervous system. Nanomedicine 2025, 1–16. [CrossRef]

| Darwinian theory | The Carbon-Based Evolutionary Theory | |

| Significance | Challenged creationism and inheritance of acquired traits | Challenged creationism and inheritance of acquired traits |

| Core concept | Organisms | Carbon-based materials (CBMs) |

| Driving force | Natural selection | Energy flow under the modulation of functions of CBMs and the environment |

| Mechanisms | Natural selection | Spirodynamic feedback and natural selection |

| Fitness calculation | The number of an individual's offspring in the next generation | The formation to degradation ratio of a CBM over a time interval |

| Life’s origin | Lacks an account for life’s origin | Schematically accounts for life’s origin |

| Inclusiveness | Lacks an explicit account for neutral or detrimental mutations | Neutral or detrimental mutations can persist if relevant CBMs are fit enough |

| Non-heritable changes | Focuses on heritable genetic changes | Considers heritable, non-heritable, and epigenetic changes |

| Order | Description of the fact |

| 1 | Charcoal combustion which consumes oxygen and forms carbon dioxide |

| 2 | Diamond synthesis from graphite under certain conditions [33] |

| 3 | Water adsorption of activated carbon |

| 4 | CO2, NH3, and other molecules form amino acids via chemical reactions [2,5] |

| 5 | Methane explosion in coal mines |

| 6 | Evaporation of ethanol from an open bottle |

| 7 | The dehydration condensation of amino acids into peptides in tubes |

| 8 | The binding of gentamicin to the 30S ribosomal subunit of some bacteria |

| 9 | The degradation of glucose into carbon dioxide and water in cells |

| 10 | Some recombinant proteins self-assembling into virus-like particles |

| 11 | DNA synthesis catalyzed by a protein |

| 12 | Starch degradation in the stomach |

| 13 | Inputting certain DNA molecules into certain cells can create new viruses [34] |

| 14 | Inputting certain DNA molecules into certain cells can create new cells [35] |

| 15 | The formation of bilayer vesicles by amphiphilic lipid molecules |

| 16 | The development of a fertilized egg into a tadpole |

| 17 | Escherichia coli absorbs glucose via its membrane carrier proteins |

| 18 | The reproduction of bacteria within chicken intestines |

| 19 | A group of ant individuals form a eusocial ant colony |

| 20 | Some trees undergo spring budding and autumn leaf shedding |

| 21 | A car collision causes human casualties |

| 22 | The formation of a basketball team by a group of young people |

| 23 | Leafcutter ants harvest foliage to cultivate symbiotic fungi in their nests |

| 24 | The destruction of a beehive by a forest fire |

| 25 | Several institutions merged into Paris-Saclay University in 2018 |

| 26 | University of the Arts Philadelphia was closed in 2024 |

| 27 | The ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine |

| Representative significance of the CBM | |

| CBM_a | The baseline scenario where the formation/degradation rates are perfectly balanced (fitness=1.0 for all time steps). CBM_a can be a species maintaining constant population size in a stable environment. |

| CBM_b | The continuous exponential growth by 10% every time step (fitness=1.10 for all time steps). CBM_b can be a bacterium beginning to grow in a broth with abundant materials and energy. |

| CBM_c | The fitness drops from 1.30 to 1.05, which can be a sign of a species adapting to environmental changes like climate shift slowing the rapid population growth of the species. |

| CBM_d | The smooth parabola shows accelerating growth followed by decelerating growth to stabilization in the population of the CBM, which can be a bacterium that has grown in a broth, with its population reaching a peak. |

| CBM_e | The curve demonstrates the inevitable fate of the CBM (fitness=0.80 for all time steps) with sustained negative growth in its population. CBM_e can be endangered species with consistently low reproductive success. |

| CBM_f | This CBM can represent those species (e.g., humans) whose fitness oscillates around 1.0 for a certain period. This phase is followed by a sharp decline in fitness to 0.05 due to a catastrophe, which causes the population to drop by approximately 95%. Subsequently, the fitness recovers rapidly—reaching a high of 3.0—before gradually returning to the earlier oscillating pattern. During this recovery stage, the population shows rapid exponential growth and eventually surpasses its original size. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).