1. Introduction

This study aims to explain the interrelationships of all the fields, including the static electromagnetic fields, gravity, and the weak and strong interactions by employing the concept of a quantized spacetime with a zero-point energy. That is, the aim of this paper is to demonstrate that the zero-point energy can describe the 4 interactions of the particle physics.

These 4 interactions have various phenomena. Thus, for example in this paper, electromagnetic fields and the weak interaction which describe the β collapse will be explained. As the gravity, we succeed to obtain the quantized Einstein’s gravity equation, using the electromagnetic fields. Furthermore, for the strong interaction, the mass of a pi-meson will be derived, employing the electromagnetic fields. Note that the electromagnetic fields which are common in the 4 interactions are derived only by the zero-point energy.

Let us discuss the background of this study. To unify the basic forces of nature has been pursued by many researchers, starting with Faraday. After his success in unifying the time-dependent electric and magnetic fields, he conducted many experiments under the assumption that the gravitational and electromagnetic fields must be unified, but he could not obtain a satisfactory result [

1]. After discovering Hertz waves experimentally, Hertz also tried to unify Maxwell’s equations and Newtonian gravity to understand how gravity is transmitted [

2]. This work was not understood by his generation, but its differential-geometry concept influenced Einstein. Einstein also tried to solve this problem. The concept he employed was to introduce an additional dimension to formulate a five-dimensional general relativity theory, hoping to unify gravity and the electromagnetic field. This is equivalent to the internal and external spaces of Kaluza-Klein theory [

3], and it was hoped that the conservation laws governing general coordinate transformations in five dimensions might lead to gravity and the electromagnetic field. However, this theory is not complete.

The current standard model of elementary-particle physics has the same problem. That is, it does not contain the interaction due to gravity. Moreover, the standard model has other problems, which we summarize. Here let us discuss from reference [

4]:

- 1)

the gravitational interaction: As mentioned, the standard model does not include the interaction due to gravity. The problem is that gravity is different from other interactions, in that an infinity of the gravitational field cannot be eliminated [

5]. To solve this problem, super-string theories [

6] are being investigated, but they currently cannot predict any physical phenomena. Another theory being investigated is loop quantum gravity [

7]. This theory—like the present paper—introduces a quantized spacetime, but no concrete calculations have been performed.

- 2)

Relations between the basic interactions: The standard model claims that it describes the basic interactions, i.e., the electromagnetic force and the weak and strong interaction. However, the relations between them are not clear in this model. Even in Weinberg-Salam theory, the relationship between the weak interaction and the electromagnetic force is not clear. Moreover, the Weinberg angle in this theory cannot be predicted in the standard model.

- 3)

The charge is not constant: In the standard model, due to the existence of weak hypercharge, the charge is a continuous variable. However, at the elementary-particle level, the charge of each particle should be constant and quantized. As long as the Weinberg-Salam theory depends on weak hypercharge, the masses of the W and Z bosons must be obtained by another method.

- 4)

The problem of quantum corrections to the Higgs field: Only a little time has passed since the discovery of the Higgs boson. However, by employing the standard model, when quantum corrections involving the square of the mass are calculated, an ultraviolet infinity appears. Basically, in the standard model the combination of spontaneous symmetry-breaking and the Higgs field results in the masses of other particles. Because this is a QED model that deals with guages, it must explain why particles such as the W or Z gain mass. However, the standard model has a problem with the Higgs, and thus the basic story above is not complete. Many theories [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] have tried to solve this problem, but no measurements support them. Moreover, in the standard model, there are many undetermined parameters in the Higgs interaction or the Yukawa interaction.

- 5)

Dark Energy and Dark Matter: Recently it has been found that about 80% of the total energy of our universe consists of Dark Energy or Dark Matter. Many researchers believe that they will be explained at the level of elementary-particle physics, but nobody has been able to circumvent the fact that Einstein’s gravitational equation cannot be quantized.

Let us explain the contents of this paper.

This paper provides a basic theoretical concept to solve the abovementioned problems, and it claims that a sole source of energy—the zero-point energy—creates all the fields, including gravity, the electromagnetic field, and the weak and strong interactions when we introduce a quantized spacetime. Moreover, the relations between these fields are made clear at the level of quantum mechanics by this concept.

First, we introduce the concept of a quantized spacetime with a zero-point energy. In the process of quantizing gravity, we derive the relationships between the energies of a static electric field, gravitation, and a static magnetic field at the level of a quantized spacetime. Using these relations, we quantify Einstein’s gravitational equation. Next, we discuss the weak interaction. Specifically, using the zero-point energy, we calculate the radius and lifetime of the neutron. Moreover, we describe a β collapse from a different point of view than Fermi. In this process, another meaning of the neutrino appears. Furthermore, we calculate the masses of the W and Z bosons from a different point of view than Weinberg-Salam theory. Next, we calculate the pi-meson, which ties nucleons together in strong interactions.

In the Appendix, we derive spin and mass of a quark. Moreover, by employing the concept of a quantized spacetime, we interpret the meaning of a wave function and compared it with Einstein’s interpretation and Born’s interpretation. In this Appendix, moreover, the contraction of a wave packet will be discussed.

The significance of this paper is that it describes the above fields and their relationships with only the assumption of a quantized spacetime as the sole source of all the fields being the zero-point energy. Note that the common fields are the electromagnetic fields but they are obtained only by the zero-point energy. Moreover, the values this theory predicts agree with measurements. Furthermore, we obtain a quantized Einstein gravity equation. Moreover, by quantizing the Einstein’s gravity equation, we can solve the problem of singularity, which implies the infinity.

2. Theory

2-1. Gravity and Electromagnetic Field in the Quantum Level

The most important claim, and the significance of this paper, is that from the zero-point energy, all fields—including the electromagnetic field, gravity, and the week and strong interaction—are derived at the level of a quantum mechanics. As discussed later, the zero-point energy basically implies the time-independent static electromagnetic field energy, and thus all the fields concerning elementary particle physics are obtained from the electromagnetic fields. We present these derivations later.

Quantum field theory is common in elementary-particle physics. However, QED employs cut-offs to avoid the problems of troublesome infinities, which is inadequate for describing the real physical picture, because the internal infinities are purposely neglected. On the other hand, our claim is different: because QED deals with extremely local fields, i.e., points, this results in the problems of infinities and invalidates relativity theory. Moreover, QCD with color charges does not provide the valid mass of a quark, i.e., the mass is put in by hand. The mass of a quark in a nucleon must be three times that of an electron, as described in the Appendix.

Previously, loop quantum gravity theory employed the concept of quantized spacetime. However, the specific quantized space-length and time-span are unclear from that theory. In the present study, we instead focus on Dirac particles that obey the Dirac equation:

where

ω0, m, and

c denote a constant angular frequency, the mass of an electron, and the speed of light, respectively

This equation can be rewritten as

which implies that the zero-point energy creates the electron mass.

The zero-point energy is obtained from the Hamiltonian

H of a harmonic oscillator when

n=0:

Because

n = 0, a summation over variable

n is not considered herein. However, we can define an angular frequency Ω = nω

0 (

. Thus, the angular frequency ω

0 is constant, and thus the zero-point energy should be considered as a specific, universal constant energy. Moreover, it implies a vacuum energy gap, according to the Dirac equation. To conclude, the zero-point energy expresses the basic energy of the vacuum. Therefore, this study considers the electron mass as the sole and most basic parameter. That is, this equation produces the minimum quantized length

and time

t0 in terms of the spacetime:

Considering the Lorentz transformation, let us generalize the zero-point energy:,

In this equation, the mass and rest energy imply a static electric field, and the velocity v implies indirectly the gravitational and magnetic fields in a quantized spacetime. We discuss the details later.

The Hamiltonian of a harmonic oscillator can be written again as

In this equation, the first term implies a time-dependent electromagnetic field from the guage. (Many studies neglecting the zero-point energy have been investigated in quantum field theory. This theory has achieved partial success, but that success is derived by employing cut-offs and quantities being put in)

Considering this, the second term, which represents the zero-point energy of the vacuum, must imply time-independent static electromagnetic fields. Thus, the zero-point energy implies the electromagnetic field energy. We derive a more general constant quantized spacetime length and time:

The reason why spacetime must be quantized is that this solves the problem of the infinities that invalidates existing theories. Moreover, the quantization makes all the fields—including particles and forces—more clear, i.e, these fields are produced solely by the zero-point energy of the vacuum.

The zero-point energies are distinguished by the following two Dirac particles:

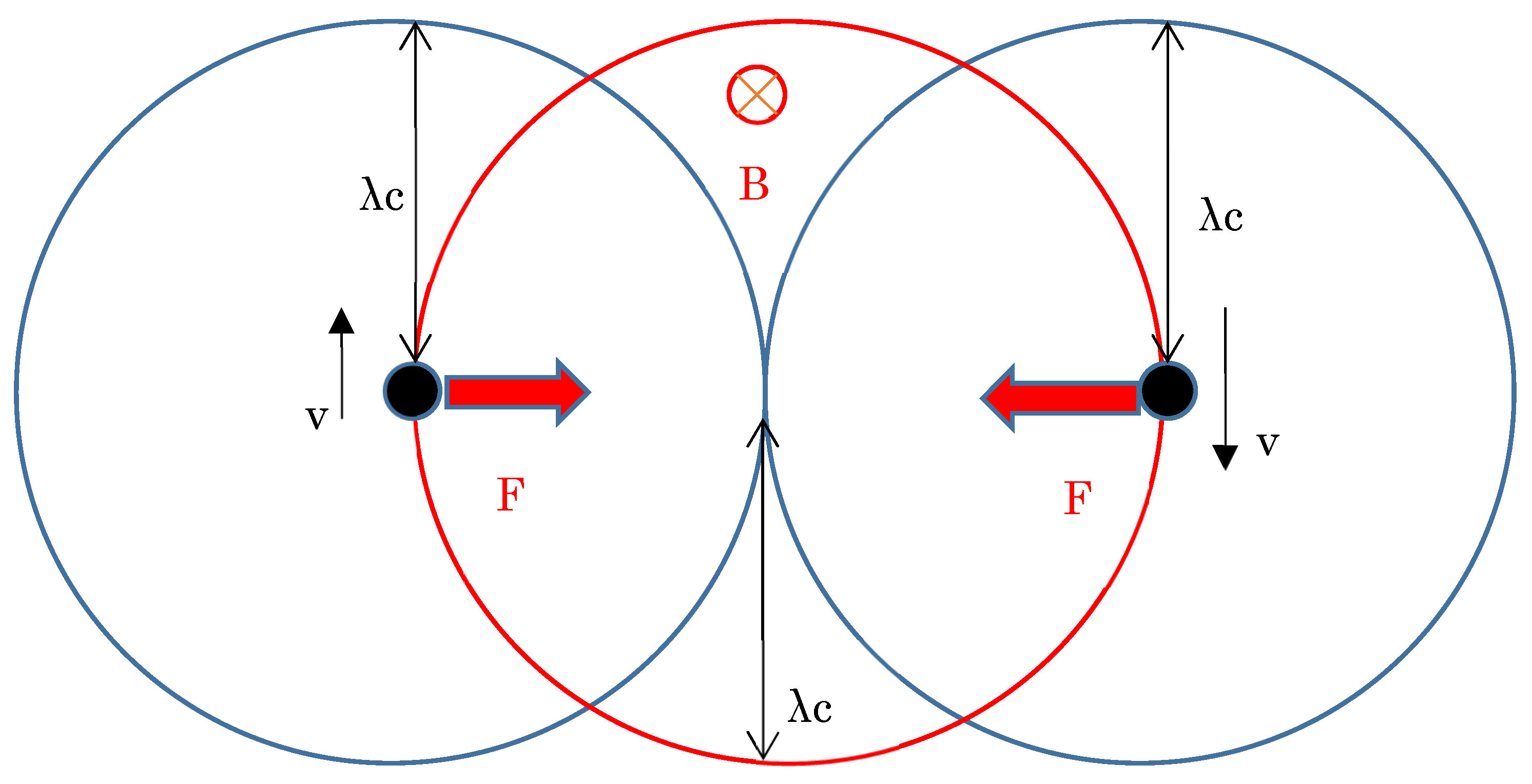

Figure 1 shows a schematic illustration of the force

F in a quantized spacetime. In this figure, two quantized spacetimes are rotating. Each quantized space has an embedded up or down spin electron. The force

F is the Lorentz-force from the static magnetic field, which is identified with the attractive gravity force

F from the gravitational field. Based on the concept in this figure, we calculate the relation among the energies of a static electric field, a static magnetic field, and a gravity field.

Let us calculate the electrostatic energy at the level of quantum mechanics.

The electric energy is given by

This is tied to the mass of the electron:

Note that there are two embedded electrons in

Figure 1.

or

where

E,

r,

ε0, e, and

uE denote the static electric field, distance, the permittivity, and the electric-field energy

In turn, the gravitational and static magnetic-field energies at the level of quantum mechanics can be calculated in terms of the velocity v in Equation (6). In the following calculations, we include the rotational movements of the two electrons embedded in the quantized spacetime.

First, the kinetic energy equals that of the gravity field.

where G denotes the gravitational constant.

From Equation (12-1), we obtain

where

v is the rotational velocity in

Figure 1:

From Equation (13), the angular frequency is

We then introduce the zero-point energy:

Thus, using the above-mentioned equations, the energy of the gravitational field becomes conclusively

Note that a general space is quantized in terms of λ

c

From the previous calculations, we obtain the relation between

uG and

uE:

Equation (20) implies a relation between

uG and

uE in a quantized spacetime. However, the static magnetic field energy

uB is given by the following in a quantized time-space:

Let us calculate the velocity

v, which is constant.

(Note that this equation embeds the Lorentz-contraction).

As we discussed later, the velocity of a neutrino can cause the quantum space-length λc to be changed to the order of size of a nucleon.

2-2. Quantization of the Einstein Gravity Equation

From the equation for quantized spacetime, we can combine the Einstein gravity equation with the derived equation, because both equations include the constant of gravitation

G. The Einstein equation is

where Rμν, Tμν, gμν and R denote the Riemann curvature tensor, the energy flux tensor, the metric tensor, and the Ricci tensor.

As a result of substituting the gravitational constant

G from Equation (23), we obtain

Herein, we assume the macroscopic tensor g

μν to be approximately the Minkowski tensor g

ij because, for a quantized spacetime, an analytical differential cannot be defined. That is, it implies merely a division by λ

c.. Moreover, the energy density is given by the zero-point energy:

Thus, T

μν is approximated by the Minkowski tensor:

Considering the above, Einstein’s gravitational equation is transformed as

As mentioned, the energy is given as the zero-point energy.

Assuming the Ricci tensor 1/2R to be substantially smaller than the first term, we obtain

Moreover, considering the initial equation (23), the root in Equation (33) is out.

Considering this, we obtain

The equation (35) implies that, even when no macroscopic matter exists, the Riemann curvature tensor is not zero due to the zero-point energy.

2-3. Weak Interaction

The zero-point energy indicates a static electromagnetic field, and this energy also describes the weak interaction. Considering a static electric field,

where

φ and

rN denote the electrostatic potential and the radius of a neutron.

This equation implies an interaction between an electron and a quark. As shown in

Figure 2, a neutron is composed of a proton and an electron. That is, an electron is distributed around the proton like a film. The important concept is that an electron generally behaves as a wave, not as a local point. This is a fact from basic quantum mechanics, while quantum field theory considers an extremely local point, which leads to the problems with infinities.

Thus,

where

σ denotes the surface density of a charge.

Therefore, we derive the approximate radius of the neutron as

As a result of calculations, we obtain

Note that the electric-field interaction is that between a quark and an electron. Moreover, it is assumed that the charge of each quark is 1/3e.

Moreover, the value of this result is a little large. However, as discussed later, because the theoretical radius of a neutron obtained from another approach , we conclude that the calculated value is valid.

Let us calculate the lifetime of a neutron.

When an electron exists within a neutron, its wavelength is changed from the order of 10-13 m, i.e., λc to the order of 10-15 m. As discussed later, this does not contradict the quantized space length, due to the existence of the neutrino. However, this electron has the property of restoring a quantized space length. Thus, the neutron has a finite lifetime.

First, we assume the following proportionality:

where

α is a constant having the unit and

t is time, or

In the above equation, we substitute the conditions:

where tα is considered the steady time. In this equation, for the time tα, the length is restored to λc..

Moreover, from Equation (41)

where for the radius

rN we substitute the value

m, which we discuss later and derive theoretically. Because the measured lifetime is about 12 minutes which is sufficiently long, we approximate that 1s is the initial time when a neutron form its radius of

rN.. Considering the number of the quark, the lifetime is thus

The measured value [

15] is 885.7 s, which agrees sufficiently well.

Let us consider a β collapse and the masses of the W and Z bosons.

A β collapse was described by Fermi. He calculated it with QED and a neutrino, and he concluded that non-conservation of the kinetic energy of the electron was avoided by adding the neutrino energy. However, we claim that

The mass of a neutrino is extremely small. Thus, even though it moves near the speed of light, its kinetic energy cannot contribute to the total energy. We claim instead that the existence of the neutrino has another reason in addition to the conservation of spin, as described later.

As described later, the kinetic energy of an electron is constant, which gives the rest energy of the W in terms of a broken symmetry of space.

The distribution of a β collapse does not indicate non-conservation of the kinetic energy of the electron but merely the probability density for an eigenfunction of the zero-point energy combined with an electron. Here, we employ Fourier transforms.

First, the total energy

ε approximately is

where

K denotes the kinetic energy of an electron.

The eigenfunction is obtained as the product of that of electron and the ground state of a photon,

i.e., the zero-point energy.

where

b is the constant wave number of an electron, and

Xn denotes ground state of a harmonic oscillator.

From any basic quantum-mechanics text,

Xn is given as

where the mass

M and the angular frequency ω will be given later.

Here, we Fourier transform this wave function using the following mathematical formulas:

When

α is determined from Equation (47) and

C is a constant, we obtain

To depict this distribution, we must determine the parameters M and ω.

To do this, we employ the zero-point energy of a quark, because the interaction is a static electric field between a quark and an electron, as discussed previously:

where the mass

mA of a quark in a nucleon is theoretically given as three times that of an electron. For details, see the Appendix.

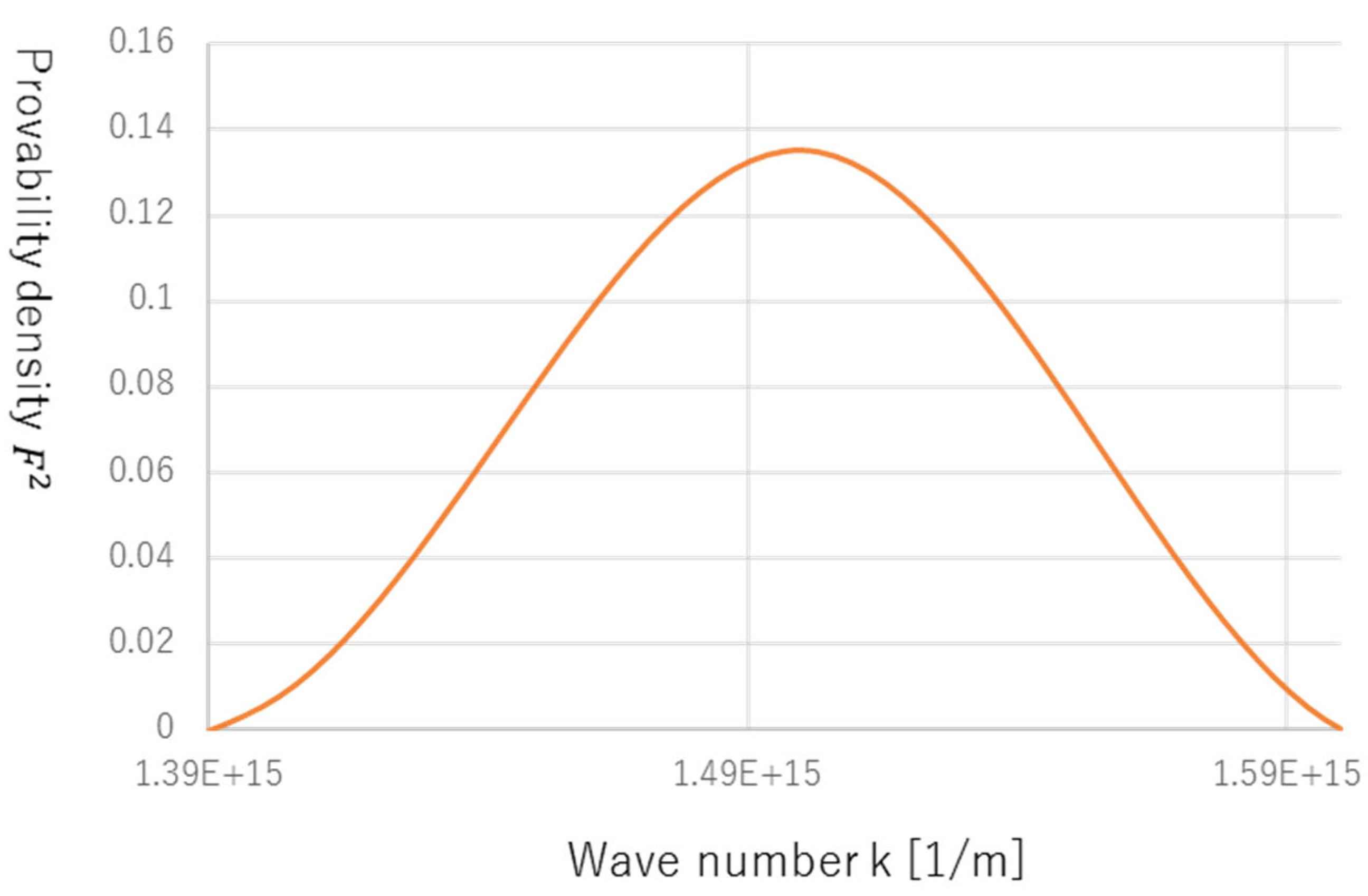

The result is shown in

Figure 3. That is, the probability density of a neutron is

F2 for wave number

k. This clearly shows that a

β collapse is described by a Gaussian distribution.

Moreover, the kinetic energy of an electron is

Considering the Feynman diagram [

15], we assume that the constant kinetic energy of an electron gives the rest energy of W:

When the mass of W in terms of measurements [

15] is applied to this equation, the constant wave number implies the radius of a neutron as follows:

The equation is allowed to consider the radius of a neutron. Using this value, we calculated the lifetime of a neutron, which agrees well with the measurements. This implies that, from the initial state where an electron is attached around a proton, the electron conserves the wavelength 1/b. Because the wave number b of an electron is positive (not negative or zero), the symmetry of space is broken. Considering this logic is gone back, it implies that the mass of W boson was predicted.

Let us consider the mass of Z.

Considering the Feynman diagram [

15], the mass difference between W and Z stems from the Coulombic attractive interaction

FE between an electron and a positron, which forms circular movements whose radius is

λc . This implies that the electron and the positron have rotation as well as linear movement.

As an important notation, in a nucleon, the perfect ferromagnetism is formed [

16]. That is,

B=

H. Thus, the permittivity

εq is varied:

Employing this value, the first term for the attractive Coulombic interaction is calculated as:

Considering the rest energy of W from the measurements, the rest energy of Z is given as:

The measurement is 91 GeV [

15], and, thus, the agreement is sufficient.

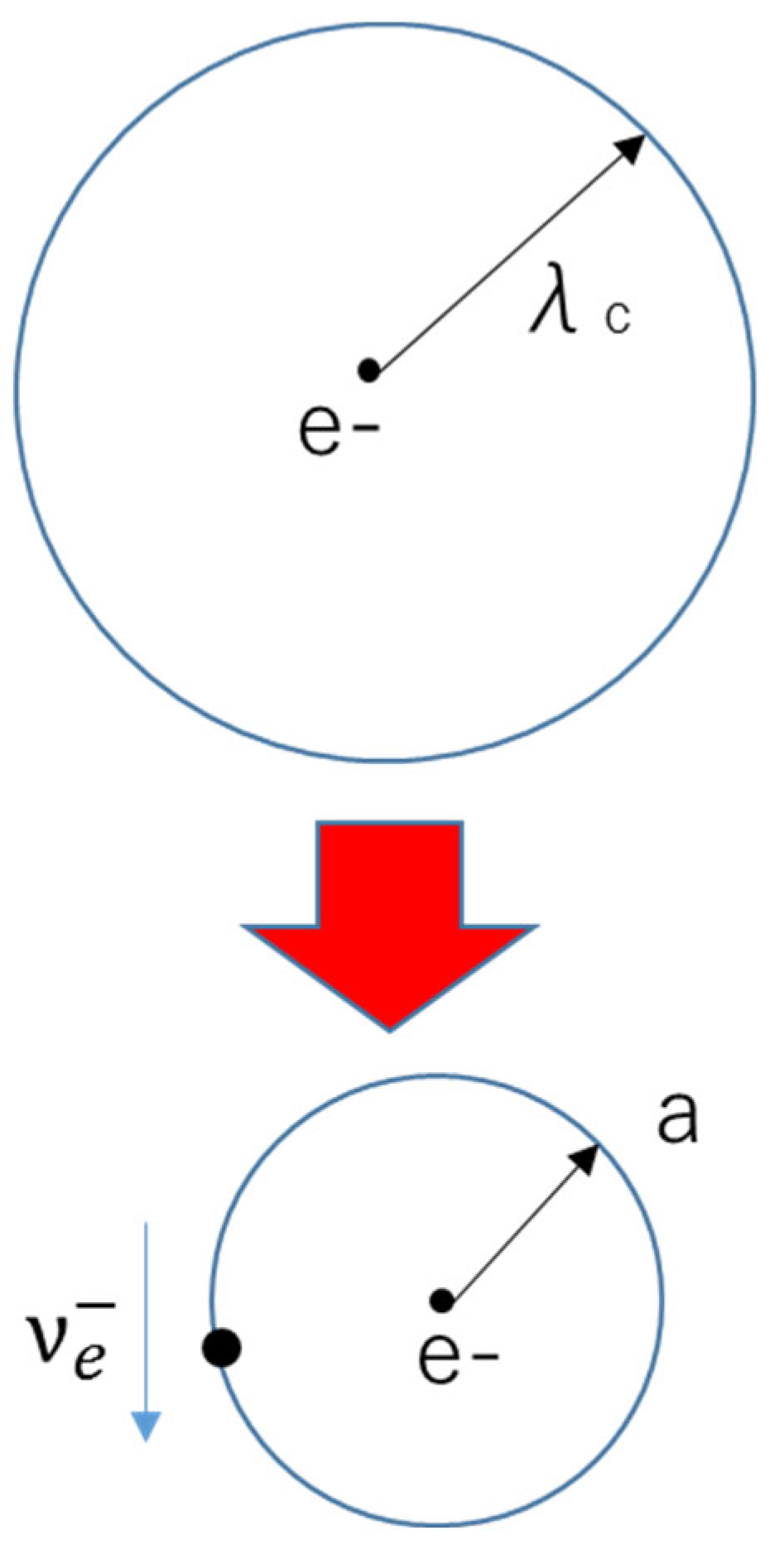

In turn, let us discuss the meaning of a neutrino.

The wave number

b of an electron implies the radius of a neutron, which has 10

-15 m order and is smaller than λ

c.. However, this does not contradict the concept of a quantized space length λ

c, owing to the existence of a neutrino. Thus far, the velocity

v in zero-point energy is kept constant at 0.68c. However, when an electron takes an accompanying neutrino, this velocity is changed, which leads to a larger Lorentz contraction, allowing for a quantized space (λ

c) change on the order of 10

-15m. Thus, electrons having a neutrino can exist in a nucleon:

where

vμ denotes the rotating velocity of a neutrino around an electron:

As indicated in the result, the speed of a neutrino is approximately 99.3% of the speed of light. Because of this, if an experimenter were to apply a rough measurement, such a high speed could not be distinguished from the speed of light. Thus, to measure the speed of a neutrino, we need to apply an extremely accurate method of measurement. In

Figure 4, a schematic of the above is shown.

2-3. Strong Interaction

In our previous paper [

16], we described quarks’ interaction as static magnetic field energy, which resulted in the mass of a proton and a linear potential. The salient point was that this interaction was also derived from the zero-point energy and the linear attractive potential was obtained purely analytically (not numerically). Here, we discuss the pi-meson, which acts between two nucleons as a strong attractive interaction. In fact, this force is also derived from the zero-point energy, and this force is, indeed, the Lorentz force.

Figure 5 shows the schematic of two nucleons in which three quarks have rotation. Each rotation of two nucleons has the same angular frequency and rotational direction. Now we consider the motions of 1a and 1b quarks.

These quarks maintain constant distance, i.e., the radius

rc, and rotational velocity remain same. Considering this fact, we can employ a model in

Figure 6. In this figure, quarks 1a and 1b move in the same direction with the same velocity. This model is analogized by two electric current leads, which exhibit an attractive force [

17]. This force is the Lorentz force. We thus claim that the strong interaction between two nucleons is the Lorentz-force, which is derived from the zero-point energy.

Let us calculate the mass of a pi-meson considering this model. .

First, as discussed previously, the internal magnetic permeability of a nucleon is determined by the fact that it has the property of the perfect ferromagnetism. That is,

B=

H. Therefore, the Lorentz-force is:

Here, the zero-point energy is considered as discussed previously:

where

mA is the mass of the quark in a nucleon, which is three times larger than that of an electron.

From [

16], three quarks, each having the charge 1/3e, have rotations with an angular frequency ω, which results in a current

I and magnetic field

H. Thus, the central magnetic field is:

where

T is the period of the rotations of the quarks.

From this current, the magnetic field is:

Thus, energy

u is gained, which is an attractive force:

When substituting the physics constants,

Thus, we obtain the mass of pi-meson

mm:

This value agrees with the mass predicted by Yukawa [

15].

3. Discussion

Existing elementary particle physics tends to add new concepts to solve problems. For example, when the problem of the exclusion principle in a nucleon arose, a new concept, the color charge, was added. However, while color charges have yet to be measured, a new theory was constructed using color charges to solve another problem. In this way, existing elementary particle physics went further in-depth and developed new confusions. Moreover, the Weinberg-Salam theory also added weak hypercharge as a new concept, and the authors introduced a continuous electrical charge. However, at the level of particle physics, a charge is quantized. While these views were adopted, the standard model had many undetermined parameters. To solve this problem, another new concept, known as the super-string, was added, a concept that has not predicted any measurable quantities in physics.

On the other hand, our attitude differs from the above. First, we have taken care to employ directly measurable physical phenomena instead of adding new concepts, and reconsider basic physics knowledge. In this way, the derived theory is simple and understandable and has a clear picture rooted in physics.

This study introduces a concept of quantized spacetimes with the zero-point energy and aims to explain all fields, including four forces and particles employing this concept. The basic assumption is only that a quantized spacetime is introduced. That is, other serious assumptions or conditions have not been introduced.

Under this concept of quantized spacetime with the zero-point energy, we could thus describe:

Uniformity of the electromagnetic and gravitational fields on the microscopic scale with a quantized Einstein gravity equation;

-

The weak field, with the radius and lifetime of a neutron, W and Z bosons, and β collapse. The key point is that the radius of a neutron has been derived by giving the measured mass of W; we use the radius of a neutron to predict the mass of W. Moreover, the mass of Z is calculated. These results agreed well with the measurements. We employed difference methods from the Weinberg-Salam theory. The reason is that:

- 1)

Weinberg-Salam theory employs weak hypercharge, and thus the charge is arbitrary and not quantized;

- 2)

The Weinberg angular was given such that the masses of W and Z agreed with the measurements [

15]. The value of the Weinberg angular had no meaning in terms of physics.

Moreover, we clarified the meaning of the existence of the neutrino in terms of a quantized spacetime. Considering the gravitational interaction between the electron and the neutrino, the mass of the electron in the

β collapse apparently varies. Thus, strictly speaking:

where α denotes the correction constant.

Thus, when the accurate mass of W and the wave number

b, i.e., the radius of a neutron, are substituted, the correction constant, α, will be calculated. According to our hand calculations, α=0.95, approximately. Note that, from the measurements of neutrino oscillation, it was clarified that there are masses of neutrinos. However, considering our derivation, it is natural that the mass of a neutrino exists because it has gravitational interaction with the electron in the

β collapse. We claim that it is more important to consider this interaction between the electron and the neutrino than to calculate the mass of the neutrino itself. However, if it can be considered that the gravitational interaction with a neutrino is identified as its measured mass, the mass can be determined with the following:

When the correction constant

α was substituted for the value 0.95, the mass, considering the gravitational interaction for a neutrino, is calculated as

This mass including the gravity is about 5% for that of an electron.

We did not consider the Higgs field. The reasons are:

- 1)

To be sure, the Higgs mass was measured. However, it was not made completely clear whether it works as predicted by the standard model [

4].

- 2)

As a more serious problem, the standard model treated cut-off Λ, which led to relatively low energy. However, when calculating quantum corrections concerning the square of the Higgs mass, there appeared a large quantum correction, proportional to ⋀2. That is, under the quantum corrections, the standard model could not guarantee the small mass of the Higgs [4]. Basically, the standard model has a model from the QED, and, as a result of introducing very local gages, it was necessary to obtain the reason the particles gained mass. To solve this problem, in the standard model, the spontaneous break of symmetries and Higgs fields were suggested. However, as discussed above, the mass of Higgs had a serious problem, which implied that the standard model was incomplete. For this reason, many new theories have been suggested, though none are supported by measurements as described in the introduction in this paper. Nonetheless, until the Higgs is accurately described, we will not consider this field.

With our previous paper [

16], a strong interaction was described between quarks. As a result, the mass of a proton, and the interaction between two nucleons, agreed well with the measurements using hand calculations. Moreover, the mass of a quark in a nucleon is clarified theoretically in the Appendix. Using this mass, the above calculations were achieved. On the other hand, the QCD has some problems:

- 1)

The concept of color charges has yet to be measured. Because the problem of the exclusion principle was solved by giving the spin of a quark theoretically instead of color charges, we claim that it was not necessary to add the concept of color charges. The color has not been expressly defined.

- 2)

In the QCD, the mass of a quark is given such that the hadrons’ masses are well-predicted.

- 3)

The QCD is a numerical calculation. This is a so-called ideal experiment, not pure theory.

To conclude, we can say that, using only the zero-point energy, we described the uniformity field including the gravity field, electromagnetic field, weak interaction, and strong interaction. However, in the present paper, we did not describe time-dependent electromagnetic fields. However, this was already well-described by quantum physics. Moreover, this paper describes only the first of three generations. As a future work, it will be necessary to consider them.

4. Summary

This paper describes how all fields in particle physics can be calculated using the concept of a quantized spacetime and the sole source of the zero-point energy.

The calculated values agreed well with the measurements. Moreover, we established new and concrete physical pictures in particle physics.

In the present work, we considered only the first of three generations. Thus, as the future works, the leptons and neutrinos of the other generations should be considered.

Acknowledgments

We thank Enago (

www.enago.jp) for English language review. We appreciate that the first version (doi: 10.20944/preprints201907.0326.v1) was published in

Preprints of MDPI.

Additional Information

This paper is not related to any competing interests such as funding, employment and personal financial interesting. Moreover, this paper is not related to non-financial competing interesting.

Introduction

As is known, the QCD model suggests color charges RGB. However, the gluon having these color charges has yet to be discovered. Quite simply, a color charge has yet to be explained. This concept does not assimilate with the real physical picture. In our previous paper [

18], we derived analytically the mass of a proton without numerical calculation and the QCD. That is, starting with the zero-point energy, the interaction of the static magnetic field through the rotations of three quarks gives the mass of a proton. As discussed previously, the mass of a pi-meson was also derived by the zero-point energy and the static magnetic field. Indeed, we claim that a strong interaction is generally derived from the zero-point energy, which is related to the mass of a quark. In this appendix, the mass and spin of a quark are considered.

Moreover, the interpretation of a wavefunction will be discussed, using the concept of a quantized spacetime in the main body. As is known, Einstein claimed that the interpretation of a wavefunction is incomplete because it does not describe a physical existence. Bohr and Born, etc. denied the Einstein’s claim but this appendix will describe that both claims are correct. Furthermore, contraction of a wave packet, which is significantly contradictory to the special relativity, will be discussed.

A1. The Mass of a Quark

The mass of a quark is derived by considering the Coulombic force:

where

pq is the momentum of a quark, which has rotations.

Given the following equation, the Coulombic force from a quark is equal to that from an electron:

where

p is the momentum of an electron.

Thus, a quark mass

mA is:

A2. The Spin of a Quark

Let us consider spins of a quark.

A spin magnetic momentum is:

where

q and

s denote the charge of a quark and the spin angular momentum.

Herein, the g-factor in Equation (a4) is assumed to be the value, 3.

Because

s in the above equation is

, the quark spin is 1/3s:

The above spin value importantly implies that, even when there are 3 up-quarks, the exclusion principle is not violated. Considering this, primitively, the concept of the color charges is not needed.

A3. Interpretation of a wave function and Contraction of a wave packet

First, the following equation is considered, accepting that the wave function is a probability

where

v is the volume.

Considering the configuration of the quantized spacetime, cylindrical coordinates are employed. That is,

In this integral, the basic and quantized spacetimes merely provide the product.

Note that the integral of angles is normally conducted. Moreover,

nz is the number of a basic and quantized spacetime. Thus,

The above implies that, while the wave function implies the probability, it also indicates the real existence of the quantized spacetimes. Equation (a9) implies both probability and an existence, which was claimed by Einstein. Thus, conclusively, as the interpretations of a wave function, Born’s and Einstein’s ones are essentially uniformed.

Next let us consider the basic momentum.

As known, the uncertainty relation [

19] is

where

When n=1, we derive the basic and quantized momentum as

That is,

because

where

me and

c denote the mass of an electron and speed of light, respectively.

Furthermore, let us consider the contraction of a wave packet.

where

In these equations, when the observation is conducted,

cannot be strictly zero. The reason is that, if

became zero, we would neglect the existence of our quantized spacetimes. Instead, when the observation is performed,

n=1. Considering this fact,

simultaneously become the constant. Thus,

The above implies that, when the observation is conducted, and . Conclusively, we claim that, when the observation is conducted, the contraction of a wave packet, which contradicts the theory of relativity, does not occur.

Then, when the observation is not conducted, is variable and thus n is also variable integer.

In the above equation, the following relation is assumed:

Then the derivation becomes

This equation is correspondent to one Einstein provided [

20].

Next, a superposition of wavefunctions is considered.

The following wave function is considered.

When the observation is conducted, we must then assume that

n=1 as described above.

However, Ψ1 is already normalized over arbitrary volume integral, as long as we consider the normalization of Φ1 over arbitrary volume integral.

Therefore, as described previously, the wave function Ψ1 essentially implies the uncertainty relation (a10) for the constant n=1, which implies and as the constants. (Note that the uncertainty relation and a wave function are essentially equal in view of the quantization.) That is, even though considering the superposition of the wave functions, the contraction of a wave packet does not occur.

References

- N. Forbes and B. Mahon, “Faraday, Maxwell, and the Electromagnetic Field” in Japanese edition, pp.112-113 by Iwanami Shoten, Publishers Tokyo, (2016).

- M. Eckert “Heinrich Hertz” in Japanese edition, pp.149-159, Japan UNI Agency Inc., Tokyo (2016).

- K. Shimizu, et al, “Study of elementary particle physics”, 1983, 67, 270–276.

- R. Hayashi, “Beyond the standard model” Maruzen Publishing Co., Ltd. pp.61, p.152 (2015).

- M. E. Peskin and D. V. Schroeder, “An introduction to quantum field theory” Westview Press, (1995).

- M.B. Green, et al, “Superstring Theory” Cambridge University Press (1988).

- R. Gambini and J. Pullin, “A first course in loop Quantum gravity”, Oxford University Press (2011).

- Arkani-Hamed, N.; et al. Phys. Lett. 1998, B429, 263.

- Randall, L.; Sundrum, R. L. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 8370. [Google Scholar]

- Appelquist, T.; et al. Phys. Rev. 2001, D64, 035002.

- Chen, H.C.; et al. Phys. Rev. 2002, D66, 036005.

- Manton, N.S. Nucl. Rev. 1979, B158, 141.

- Hosotani, Y. Phys. Lett. 1983, B126, 309.

- Fairlie, D.B. Phys. Lett. 1979; B82, 97.

- Y. Hara, “Elementary Particle Physics” Shokabou Tokyo, p.192. p.114, p.117, p.115, pp.45-55 (2003).

- S. Ishiguri, Preprints, 2019, 2019020021. [CrossRef]

- Results in Physics. 2013; 3, 74–79.

- S. Ishiguri, Preprints, 2019, 2019020021. [CrossRef]

- S. Ueda, “Morden Quantum Mechanics”, p.25, Baifukan Tokyo (2004).

- Y. Hara, “Elementary Particle Physics”, p.51, Shokabo Tokyo (2003).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).