1. Introduction

The proliferation of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) in civil airspace has catalyzed the development of Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM) frameworks designed to enable safe, efficient, and scalable operations beyond visual line of sight [

1,

2]. International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) guidance, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) UTM Concept of Operations version 2.0, NASA’s Technical Capability Level (TCL) demonstrations, and the European U-space framework collectively defined core service requirements including strategic conflict management, tactical deconfliction, conformance monitoring, and distributed information sharing [

1,

2,

3,

4].

These frameworks anticipated operational ecosystems consisting of multiple UAS Service Suppliers (USS) or Common Information Service (CIS) providers interconnected through standardized exchanges and supervised by air navigation service providers or competent authorities [

2,

4,

6]. However, existing guidance documents intentionally remained implementation-agnostic regarding detailed technical architectures, explicit module boundaries, federation protocols, and ecosystem-level monitoring arrangements [

1,

2,

7]. While this flexibility supported innovation, it created challenges for interoperability verification, systematic performance comparison, and the development of evidence-based standards [

5].

Contemporary research prototypes and early deployments exhibited heterogeneous architectural decompositions that embedded UTM functions in project-specific configurations [

8,

9]. While these implementations demonstrated technical feasibility, their diversity complicated comparative evaluation and limited transferability of validation evidence across contexts. Survey literature identified multi-provider interoperability, scalable conflict management under high density, and federated safety monitoring as persistent research challenges [

5]. Concurrently, emerging safety monitoring initiatives for UTM emphasized the necessity of consistent, real-time performance observation and security monitoring across federated provider ecosystems [

10].

1.1. Research Gap and Contributions

Despite progress in UTM service definition and demonstration, three critical gaps persisted:

- 1.

Architectural specification gap: Absence of published experimental frameworks with explicit module boundaries, standardized interfaces, and clear separation of concerns aligned with international frameworks.

- 2.

Federation mechanism gap: Lack of concrete, evaluable implementations for multi-provider coordination including intent exchange protocols, constraint dissemination patterns, and health monitoring aggregation.

- 3.

Quantitative evaluation gap: Limited empirical evidence characterizing performance trade-offs of federated versus centralized configurations across operationally relevant demand and communication regimes.

This research addressed these gaps through the following contributions:

Experimental framework design: We designed and implemented a modular UTM experimental framework with explicit five-layer decomposition (strategic planning, tactical monitoring, safety/ecosystem monitoring, identity/security, federation/energy interfaces) and standardized interface contracts aligned with ICAO, FAA, NASA, and U-space concepts [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Federation implementation: We implemented a federation model defining three interface families for multi-provider interoperability: intent exchange for strategic coordination, constraint dissemination for shared situational awareness, and health summary aggregation for ecosystem oversight [

2,

4,

6].

Simulation-based evaluation methodology: We developed a discrete-event simulation framework instantiating the experimental architecture with explicit event processing, parametric traffic generation (Poisson arrivals), and communication modeling (exponential delays), enabling controlled experimentation.

Empirical performance characterization: We conducted experiments across 18 configurations (, , federation , 3 replications per configuration) that revealed regime-dependent federation performance and quantified coordination overhead versus conflict prevention benefits.

Quantitative safety assessment framework: We developed and validated a composite safety scoring framework (Eq.

1) aggregating conflict rates, alert frequencies, and communication reliability into a unitless indicator supporting governance decision-making.

The experimental framework and simulation methodology were designed to support systematic comparison of UTM implementations, generation of evidence for standards refinement, and exploration of federation policy alternatives under controlled conditions.

2. Background and Definitions

2.1. UTM Frameworks and Service Requirements

UTM encompasses services, technologies, and procedures for managing UAS operations in airspace where traditional air traffic control is limited or absent [

1,

2]. ICAO characterized UTM as a framework providing guidance on essential components while remaining non-prescriptive regarding specific implementations to accommodate diverse regulatory and operational contexts [

1].

The FAA UTM ConOps v2.0 envisioned a federated ecosystem wherein UAS operators interact with USS providers that offer planning, authorization, and monitoring services through networked information exchanges coordinated by the Flight Information Management System (FIMS) [

2]. NASA’s UTM program demonstrated progressive technical capabilities through field tests validating information exchange specifications and operational procedures [

3]. In Europe, U-space designated a regulatory framework and service architecture supporting dense drone operations through digital services including electronic identification, geofencing, traffic information, and dynamic capacity management [

4,

6].

2.2. Core Functional Requirements

Our analysis of ICAO, FAA, NASA, and U-space documentation revealed convergent functional requirements:

Strategic conflict management: Pre-flight submission, evaluation, and deconfliction of operation intent descriptions specifying four-dimensional (spatial-temporal) volumes [

1,

2,

4].

Tactical deconfliction and conformance monitoring: Real-time position tracking, deviation detection against approved intents, and conflict alerting with resolution advisories [

2,

4,

8].

Constraint and information sharing: Publication and subscription mechanisms for airspace constraints (static and dynamic restrictions), meteorological data, and operational intent summaries enabling shared situational awareness [

2,

4,

6].

Identity and authentication: Remote identification of UAS and authenticated association of operational messages with registered entities [

11].

Monitoring and performance oversight: Collection of operational indicators, detection of anomalies, and support for safety and security governance [

7,

10].

2.3. Federation and Multi-Provider Coordination

High-density urban operations and cross-jurisdictional flights necessitated coordination among multiple service providers operating under common regulatory oversight [

2,

4]. Existing frameworks described federation conceptually through networked USS exchanges (FAA), CIS provider coordination (U-space), and harmonized information models [

6], but detailed technical specifications for federation protocols, conflict arbitration across providers, and aggregated monitoring remained areas of ongoing standardization [

5].

3. Related Work

3.1. High-Level Frameworks and Guidance

ICAO, FAA, NASA, and SESAR documentation established service taxonomies and information exchange concepts while explicitly deferring technical architecture prescriptions to national authorities and implementers [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Eurocontrol surveys documented heterogeneity in national U-space implementation approaches and operational maturity levels [

6]. Recent survey literature synthesized these initiatives and identified persistent challenges in interoperability standardization, governance model definition, and scalability validation [

5].

3.2. System Architectures and Prototypes

Concrete architectural proposals addressed specific UTM subdomains. Capitán et al. [

8] presented an architecture for U-space in-flight services emphasizing tactical conflict detection and resolution. Liu et al. [

9] proposed an ANSP-centric architecture integrating UTM with traditional air traffic management. These contributions demonstrated feasibility within their operational scopes but were tailored to particular contexts, limiting applicability as general reference models for comparative research [

5].

3.3. Airspace Structuring and Conflict Resolution

Performance-based airspace design methodologies provided frameworks for structuring low-altitude operations under capacity and safety constraints [

12,

13]. Optimization-based strategic deconfliction algorithms offered computational approaches to intent planning that could be integrated into strategic planning modules [

14]. Corridor-based and structured routing models provided alternatives for reducing conflict search complexity through spatiotemporal allocation [

15].

3.4. Safety Monitoring and Security

The IETF DRIP architecture specified secure remote identification mechanisms supporting authenticated message-entity associations [

11] but did not define ecosystem-level monitoring architectures. FAA-sponsored work on In-Time Aviation Safety Management Systems (IASMS) emphasized cross-provider observability, standardized performance indicators, and continuous monitoring capabilities for federated UTM environments [

10], complementing the monitoring layer design implemented in this research.

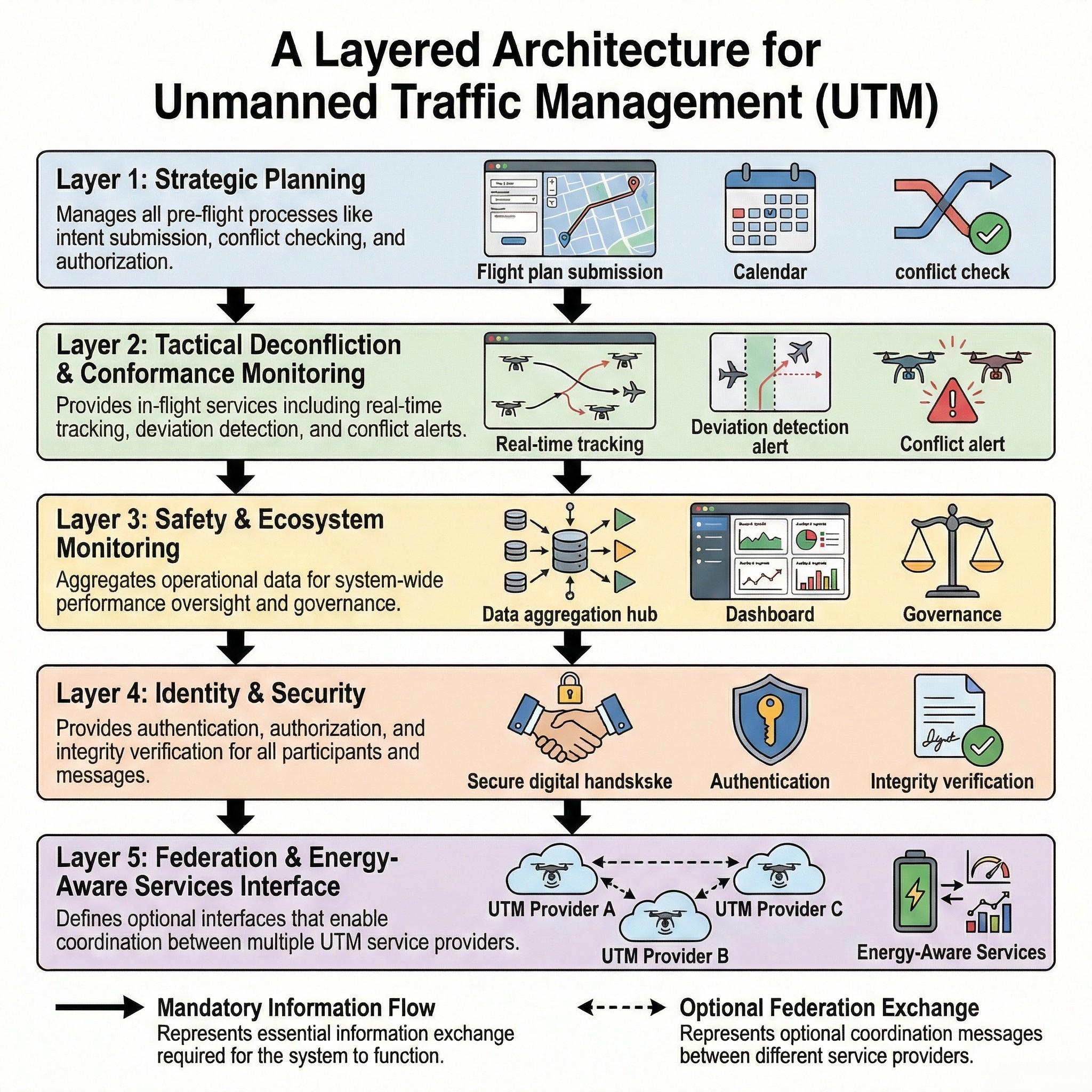

4. Experimental Framework Design

We designed a modular UTM experimental framework decomposing functionality into five layers with explicit interface boundaries and information flows (

Figure 1). The decomposition reflected separation of concerns aligned with the functional requirements identified in

Section 2 while supporting independent evolution of layer implementations.

4.1. Strategic Planning Layer

The strategic planning layer managed pre-flight processes including operation intent specification, constraint checking, strategic conflict detection and resolution, and authorization decision-making [

1,

2,

4].

4.1.1. Interface Contracts

We defined the following interface contracts:

submitIntent(spatiotemporalVolume, constraints, priority)→{approved, conditionalApproval, rejected, alternativeProposal}

queryConflicts(intentID, spatiotemporalVolume)→conflictSet

publishIntentSummary(intentID, publicVolume, validity) enabled ecosystem coordination.

4.1.2. Internal Processing

Our implementation employed heuristic deconfliction with trajectory adjustment and temporal shifting. The framework design specified interface semantics while permitting algorithm substitution, supporting comparative evaluation of resolution strategies in future work.

4.2. Tactical Deconfliction and Conformance Monitoring Layer

The tactical layer provided in-flight services including real-time conflict detection, conformance monitoring, and advisory generation [

2,

4,

8].

4.2.1. Interface Contracts

We implemented the following interfaces:

trackPosition(flightID, position, timestamp, uncertainty) ingested telemetry.

emitConformanceEvent(flightID, deviationType, severity, recommendedAction) notified operators and monitoring functions when trajectories deviated from approved intents beyond defined thresholds [

2].

emitConflictAlert(flightID1, flightID2, conflictGeometry, timeToClosestApproach, advisoryType) supported tactical separation assurance.

4.2.2. Conformance Monitoring

Conformance assessment compared observed positions against approved four-dimensional volumes accounting for position uncertainty and operational tolerances. Threshold exceedances triggered graded responses ranging from informational notifications to mandatory corrective actions depending on severity and proximity to other operations or constraints.

4.3. Safety and Ecosystem Monitoring Layer

The monitoring layer aggregated operational and system health indicators across providers and operational volumes to enable ecosystem-level performance oversight and governance-aligned interventions [

7,

10].

4.3.1. Observable Indicators

The monitoring layer collected:

Conflict metrics: Total conflicts, resolution success rate, unresolved conflict rate, mean time to resolution.

Communication metrics: Message latency distributions, loss rates, service availability by provider.

Conformance metrics: Deviation event frequencies, categorized by severity.

Alerting metrics: Alert counts by type, response latencies, escalation rates.

4.3.2. Composite Safety Scoring

We developed a unitless safety score

S aggregating multiple indicators to support trend analysis and threshold-based governance triggers:

where

is normalized conflict rate,

is normalized alert rate,

is communication success rate, and

is a latency penalty factor. Weights reflected relative safety criticality based on expert judgment and operational literature. The score ranged from 0 (critical degradation) to 1 (nominal operations).

4.3.3. Governance Feedback

Monitoring outputs informed mitigation actions including temporary capacity reductions, enhanced separation buffers, restrictions on new operation approvals, or escalation to authority intervention. Interface contracts specified feedback pathways while leaving policy parameter definition to governance frameworks.

4.4. Identity and Security Layer

The identity and security layer provided authentication, authorization, integrity verification, and privacy enforcement across ecosystem participants [

11].

4.4.1. Core Functions

The implementation included entity registration and credential issuance for UAS, operators, service providers, and authorities; message signing and verification supporting non-repudiation; access control enforcement governing information visibility based on operational need and privacy regulations; anomaly detection identifying potential spoofing, message replay, or unauthorized access attempts.

4.4.2. Security Event Reporting

Security-relevant events (authentication failures, integrity violations, anomalous message patterns) were reported to the monitoring layer via standardized event streams, enabling correlation with operational anomalies and coordinated response [

10].

4.5. Federation and Energy-Aware Services Interface

High-density multi-provider ecosystems required coordination mechanisms and capacity-aware planning support. This layer defined optional interfaces exposing federation coordination primitives and feasibility/capacity indicators without prescribing specific energy models or infrastructure representations [

12,

13].

4.5.1. Federation Coordination Primitives

Intent exchange interfaces enabled cross-provider visibility of operation summaries in shared volumes. Constraint dissemination interfaces distributed geofencing updates, dynamic restrictions, and capacity advisories. Health summary interfaces aggregated provider-level indicators for ecosystem monitoring.

4.5.2. Capacity and Feasibility Indicators

Strategic planning services queried predicted feasibility indicators for candidate trajectories, local congestion metrics, or infrastructure availability signals (e.g., vertiport capacity, charging station queues) to inform intent generation and negotiation. The interface abstraction permitted integration of diverse airspace design and capacity models [

12,

15] while maintaining architectural modularity.

5. Multi-Provider Federation Implementation

Federated UTM ecosystems with multiple USS or CIS providers required standardized information exchange while preserving provider autonomy and supporting regulatory oversight [

2,

4,

6]. We implemented a federation model defining three interface families: intent exchange, constraint dissemination, and safety/health aggregation.

5.1. Cross-Provider Intent Exchange

Each provider maintained operation intents for its client base but shared sufficient information to enable deconfliction in shared airspace [

2,

4].

5.1.1. Intent Summary Publication

Providers published intent summaries for operations overlapping shared coordination volumes. Summaries included spatiotemporal extents (four-dimensional bounding volumes), operational priority classifications, and validity periods. Full operational details remained provider-internal except where disclosure was operationally necessary or mandated by regulation.

5.1.2. Coordination Protocol

When strategic planning detected potential conflicts with published intent summaries from other providers, a coordination handshake was initiated:

- 1.

Requesting provider queried conflict details from publishing provider.

- 2.

Providers exchanged resolution proposals (trajectory modifications, temporal adjustments, priority-based yielding).

- 3.

Providers converged on mutually acceptable resolution or escalated to authority arbitration.

- 4.

Resolution outcome was published as updated intent summaries.

The implementation specified coordination message semantics and sequencing while permitting diverse negotiation strategies [

14].

5.2. Constraint Dissemination

Airspace constraints—including permanent and temporary flight restrictions, U-space volume activations, dynamic geofences, and infrastructure status—were disseminated through shared information services or authority-operated distribution points [

2,

4,

6].

Providers subscribed to constraint updates relevant to their operational areas and propagated constraints to client operators during intent evaluation. Optional capacity advisory messages (congestion indicators, demand forecasts) were published by providers or authorities to support demand-responsive planning.

5.3. Federated Safety and Health Monitoring

To enable ecosystem-level oversight, providers periodically published health summaries to a centralized or distributed monitoring function operated under the applicable governance framework [

7,

10].

5.3.1. Health Summary Content

Provider health summaries included:

Service availability metrics (uptime, planned maintenance windows).

Aggregated performance indicators (mean message latencies, loss rates, client counts, operation volumes).

Operational indicators (conflict counts by severity, resolution success rates, conformance deviation frequencies).

Security event summaries (authentication failure rates, anomaly detection alerts).

5.3.2. Ecosystem Monitoring and Intervention

The monitoring function correlated health summaries across providers to detect systemic degradations (correlated latency increases, regional conflict surges, coordinated security events). Detection triggered governance-defined responses, which included capacity restrictions, mandatory separation buffer increases, enhanced reporting requirements, or operational limitations until conditions normalized [

6,

7,

10].

6. Simulation Methodology

6.1. Discrete-Event Simulation Model

We developed a discrete-event simulator instantiating the experimental framework to enable quantitative evaluation under controlled conditions. The simulator implemented explicit event processing for flight arrivals, intent submissions, conflict detection, conformance checks, message exchanges, and monitoring indicator updates.

6.1.1. Traffic Generation

Flight arrivals followed a Poisson process with configurable rate parameter (flights per hour). Each arriving flight generated an operation intent specifying origin, destination, planned trajectory waypoints, temporal windows, and priority class. Trajectory generation used simplified point-to-point routing with randomized lateral and vertical profiles within the simulated airspace volume.

6.1.2. Communication Modeling

Inter-module and inter-provider communication delays were modeled as exponentially distributed random variables with mean (seconds). Message loss events occurred with configurable probability . This stochastic communication model represented network variability and enabled evaluation of system robustness under degraded connectivity conditions.

6.1.3. Strategic Planning Simulation

The strategic planner received intent submissions, queried existing approved intents and published constraint sets, performed four-dimensional conflict detection with configurable spatial buffers (100 meters horizontal, 50 meters vertical) and temporal lookahead, and executed conflict resolution through trajectory adjustment or temporal shifting. In federated configurations, cross-provider coordination added communication round-trips (

s overhead per coordination event) reflecting the protocol handshake described in

Section 5.

6.1.4. Tactical Monitoring Simulation

Tactical monitoring tracked simulated aircraft positions (updated at 1 Hz), compared observed trajectories against approved intent volumes accounting for position uncertainty, and generated conformance deviation events when thresholds were exceeded. Conflict alerts were issued when separation minima between tracked aircraft fell below safety buffers during in-flight operations.

6.1.5. Safety Scoring Implementation

The simulator computed the composite safety score (Eq.

1) at each monitoring cycle by aggregating conflict rates (conflicts per completed flight), alert rates (alerts per completed flight), communication success rates (delivered messages divided by sent messages), and latency factors (normalized by threshold values). The score provided a single composite indicator for scenario comparison.

6.2. Experimental Design

The evaluation spanned 18 configurations representing a factorial design across three factors:

Traffic demand: flights/hour, representing low, moderate, and high-density operations.

Communication delay: seconds, representing fiber-optic, cellular, and satellite communication regimes.

Federation mode: Enabled (multi-provider with coordination) versus Disabled (single-provider baseline).

Each configuration was replicated three times with independent random seeds to estimate variability. Simulation duration was fixed at a sufficient interval to observe steady-state behavior (minimum 100 completed flights per run).

6.3. Metrics and Data Collection

The simulator recorded:

Operational metrics: Total flights submitted, completed flights, cancelled flights, peak concurrent operations.

Conflict metrics: Total conflicts detected, conflicts resolved strategically, unresolved conflicts, conflict rate (conflicts per completed flight), resolution success rate.

Communication metrics: Messages sent/delivered/lost, mean latency, maximum latency, communication success rate.

Alerting metrics: Total alerts, alert subtypes (conformance deviation, tactical conflict), alert resolution latencies.

Safety score: Composite indicator per Eq.

1.

Raw event logs and aggregated statistics were exported in CSV format for reproducibility and independent analysis.

7. Experimental Results

7.1. Overall Performance Across Configurations

Table 1 presents aggregated metrics (means with standard deviations across three replications) for all experimental configurations. Communication success rates remained high (

) across all scenarios, indicating the simulated communication model maintained reliable message delivery even under high delay conditions (

s).

7.2. Federation Performance: Regime-Dependent Effects

Federation impact varied systematically with traffic demand and communication characteristics:

7.2.1. Low Demand Regime ( flights/hour)

At low demand with minimal delay (s), federation increased mean conflicts fourfold (0.33 to 1.33) despite maintaining high safety scores (). This result reflected federation coordination overhead (s per coordination event): at low traffic density, natural spatial-temporal separation was sufficient, and coordination handshakes introduced timing perturbations that occasionally created conflicts where none would exist in single-provider operation.

At moderate and high delays (s), this effect diminished as communication latency dominated coordination overhead, and the small number of overlapping operations limited coordination frequency.

7.2.2. Moderate Demand Regime ( flights/hour)

At moderate demand, federation effects became mixed. With minimal delay (s), federation increased conflicts (9.33 to 15.33) and reduced safety scores (0.916 to 0.775), consistent with overhead-induced perturbations. However, at moderate delay (s), federation provided marginal benefit (11.33 to 9.67 conflicts) and substantially improved safety scores (0.696 to 0.856). This crossover suggested a regime transition where coordination benefits began to outweigh overheads as operation density increased and intent conflicts became more probable.

At high delay (s), federation improved resolution success rates (0.847 to 0.967) and safety scores (0.690 to 0.872) despite similar absolute conflict counts, indicating enhanced conflict management quality under degraded communication.

7.2.3. High Demand Regime ( flights/hour)

At high demand with moderate delay (s), federation demonstrated clear benefit: mean conflicts decreased 34% (44.0 to 29.0), alerts decreased 66% (19.3 to 6.67), and safety scores improved 28% (0.637 to 0.818). This performance gain reflected coordinated strategic planning across providers that reduced intent overlaps before operations commenced. The benefits persisted at high delay (s) with improved resolution success (0.860 to 0.930) and reduced alert variability.

Interestingly, at minimal delay (s) and high demand, federation provided smaller marginal improvement, suggesting that rapid single-provider planning achieved comparable deconfliction effectiveness when communication was instantaneous.

7.3. Safety Score Dynamics

Safety scores (Eq.

1) ranged from 0.637 to 1.000 across configurations. Scores below 0.70 occurred exclusively at high demand (

), indicating that current safety margins were challenged under dense operations. Federation consistently improved scores in moderate-to-high demand regimes (

,

s), with improvements ranging from 16% to 28%.

The composite score successfully integrated multiple performance dimensions: configurations with high conflict rates but perfect communication (e.g., , s, non-federated: 44 conflicts, 0.999 comm. success) yielded scores near 0.64, while configurations with moderate conflicts and excellent alert management (e.g., , s, federated: 9.67 conflicts, 4.67 alerts) yielded scores near 0.86.

7.4. Communication Performance

Mean communication latencies closely tracked configured delay parameters () with small variance. Federation added measurable overhead (0.1s per coordination cycle), observable in the increased mean latencies for federated configurations (e.g., s baseline: 0.200s → federated: 0.299s). Communication success rates remained consistently high () even under high-delay conditions, indicating robust message delivery in the simulated network model.

7.5. Resolution Success and Alert Management

Strategic conflict resolution success rates remained at or near unity for most configurations, degrading only under combined high demand and high delay (e.g., , s: 0.860 non-federated, 0.930 federated). This degradation suggested capacity limits of the strategic planner under stressed conditions.

Alert frequencies correlated with demand but showed complex interactions with federation: federation reduced alerts substantially at high demand (19.3 to 6.67 at , s) by preventing conflicts strategically, but occasionally increased alerts at low demand due to coordination-induced timing shifts.

8. Discussion

8.1. Mechanistic Interpretation of Federation Effects

The regime-dependent federation performance observed in this study can be explained through a benefit-cost framework:

Federation benefit arose from coordinated strategic planning that identified and resolved intent conflicts across provider boundaries before operations commenced. This benefit scaled with traffic density and overlap probability: at high demand, numerous overlapping intents generated substantial conflict prevention value from coordination.

Federation cost comprised communication overhead (round-trip coordination messages, s per exchange) and potential timing perturbations introduced by inter-provider negotiation. This overhead was approximately constant per coordination event.

Net benefit = prevention value - overhead cost. At low density (few overlaps), overhead exceeded prevention value, yielding negative net benefit. At high density (many overlaps), prevention value dominated, yielding positive net benefit. The crossover occurred near –60 flights/hour in the tested scenarios.

This mechanistic understanding suggested that demand-adaptive federation policies enabling coordination only when density exceeds thresholds could optimize performance across operational regimes.

8.2. Safety Monitoring and Governance Implications

The composite safety score (Eq.

1) provided a single indicator aggregating multiple performance dimensions, facilitating threshold-based governance decisions. The observed score range (0.637–1.000) and clear sensitivity to demand and configuration parameters validated the score’s utility for operational monitoring.

Practical deployment would require calibration of score component weights through operational data and stakeholder input to reflect jurisdiction-specific safety priorities. The explicit formula enables transparent governance discussions regarding trade-offs between conflict minimization, alert management, and communication reliability.

8.3. Implications for UTM Standards and Deployment

The experimental framework and empirical results informed several standardization and deployment considerations:

- 1.

Module boundary standardization: The five-layer decomposition with explicit interfaces provided a concrete starting point for interface specification efforts within ASTM, EUROCAE, and other standards development organizations.

- 2.

Federation protocol requirements: The quantified coordination overhead (s per exchange) and regime-dependent performance suggested that federation protocol standards should accommodate demand-adaptive coordination strategies and specify maximum coordination latency budgets.

- 3.

Capacity planning: The observed safety score degradation at high demand (, scores < 0.82) indicated operational capacity limits under the tested conflict resolution algorithms and separation buffers. Operational planning should account for demand thresholds beyond which additional mitigation measures (enhanced separation, restricted entry) become necessary.

- 4.

Communication requirements: The robust performance under moderate delays (s) suggested that cellular-class communication infrastructure suffices for strategic coordination, while high delays (s) degraded but did not eliminate federation benefits, indicating tolerance for satellite communication in remote operations.

- 5.

Ecosystem monitoring: The demonstrated utility of the composite safety score and regime-dependent performance patterns supported the case for standardized ecosystem monitoring frameworks enabling real-time performance assessment and adaptive governance responses [

10].

8.4. Limitations and Future Work

This study exhibited several limitations that suggest directions for future research:

Simplified trajectory model: The point-to-point trajectory generation with randomized profiles simplified operational realism. Future work should incorporate mission-specific flight profiles, infrastructure constraints (vertiports, charging stations), and energy-aware routing [

12].

Idealized communication model: The exponential delay model represented network variability but did not capture correlated failures, congestion dynamics, or adversarial degradation. More sophisticated network simulations would enhance realism.

Conflict resolution algorithms: The heuristic resolution strategy provided baseline performance. Comparative evaluation of optimization-based [

14] and learning-based resolution algorithms within this framework would quantify algorithmic performance differences.

Scalability limits: The maximum tested demand ( flights/hour) represented high-density urban operations but did not explore extreme-density scenarios or large-scale geographic deployments. Distributed simulation techniques would enable larger-scale studies.

Security and adversarial scenarios: The current implementation assumed cooperative participants. Evaluation under adversarial conditions (spoofing, denial-of-service, malicious intent submission) would assess framework resilience and inform security requirement prioritization.

9. Conclusions

This research designed, implemented, and empirically evaluated a modular UTM experimental framework addressing critical gaps in multi-provider federation understanding and quantitative performance characterization. Through controlled simulation experiments across 18 configurations spanning low-to-high traffic demand and varied communication regimes, we established several key findings:

- 1.

Regime-dependent federation performance: Multi-provider coordination provided net operational benefit only above traffic density thresholds (crossover near –60 flights/hour). At high demand () with moderate delay (s), federation reduced conflicts by 34% and improved composite safety scores by 28%, while at low demand () coordination overhead dominated, increasing conflicts fourfold.

- 2.

Quantified coordination overhead: Cross-provider coordination imposed approximately 0.1 seconds overhead per exchange, measurable in communication latency increases and occasional timing perturbations at low traffic densities where natural separation would otherwise suffice.

- 3.

Communication tolerance: Moderate communication delays (s, representative of cellular networks) preserved federation benefits, while high delays (s, representative of satellite links) degraded but did not eliminate coordination value, particularly under high demand where strategic planning horizon exceeded communication latency.

- 4.

Composite safety scoring utility: The developed safety score (Eq.

1) successfully integrated conflict rates, alert frequencies, and communication reliability into a unitless indicator (range 0.637–1.000) with clear sensitivity to operational regimes, validating its applicability for governance monitoring.

- 5.

Operational capacity limits: Safety scores below 0.70 occurred exclusively at high demand, indicating that tested separation buffers and resolution algorithms approached capacity limits under dense operations, suggesting need for adaptive governance interventions (enhanced separation, demand restrictions) above critical thresholds.

The experimental framework, simulation implementation, and empirical results provided evidence-based inputs for UTM standards development, deployment planning, and federation policy design. The established regime-dependent performance envelope enables informed decisions regarding when and where multi-provider coordination provides operational value versus imposes unnecessary complexity.

Future research should extend this framework to incorporate more sophisticated trajectory models, energy-aware routing, adversarial scenarios, and larger-scale deployments to further refine operational guidance and validate findings across diverse operational contexts.

References

- International Civil Aviation Organization. “Unmanned Aircraft Systems Traffic Management (UTM) - A Common Framework with Core Principles for Global Harmonization,” Edition 4, 2023.

- Federal Aviation Administration. Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) Traffic Management (UTM) Concept of Operations, Version 2.0. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- NASA. “UAS Traffic Management (UTM) Project,” Technical Capability Level (TCL) 3 Demonstration. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- SESAR Joint Undertaking, European ATM Master Plan: Roadmap for the safe integration of drones into all classes of airspace. 2018.

- Hamissi, A.; et al. A Survey on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Traffic Management: Infrastructure, Approaches, Security, and Future Challenges. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 39752–39782. [Google Scholar]

- EUROCONTROL. U-space Implementation: State of Play and Future Directions, 2021.

- ICAO. “Manual on Collaborative Air Traffic Flow Management (ATFM),” Doc 9971, 2018.

- Capitán, J.; et al. Mission-oriented UAS Traffic Management Combining Situational Awareness and Flight Planning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 120752–120766. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Exploring the Integration of UAV Traffic Management System and ATFM System. Aerospace 2021, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Aviation Administration. “In-Time Aviation Safety Management System (IASMS) Project,” Technical Report, 2022.

- IETF DRIP Working Group. “Drone Remote Identification Protocol (DRIP) Architecture,” RFC 9153, 2022.

- Pongsakornsathien, N.; et al. A Performance-Based Airspace Model for Unmanned Aircraft Systems Traffic Management. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 76729–76748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; et al. Strategic Airspace Design for Safe and Efficient Urban Air Mobility Operations. Journal of Air Transportation 2023, 31, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Vural, S. Y.; et al. Optimization-Based Strategic Conflict Resolution for Urban Air Mobility. Transportation Research Part C 2023, 146. [Google Scholar]

- Rastgoftar, H.; et al. Corridor-Based UAS Traffic Management for Urban Air Mobility. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2024, 25, 412–425. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).