1. Introduction

Ampullary carcinoma (AC) is a rare gastrointestinal (GI) cancer, accounting for approximately 0.2% of all GI malignancies [

1]. Nevertheless, recent data indicate a rising incidence of AC [

1,

2]. This malignancy originates from the ampullary complex, an anatomical structure comprising the intraduodenal portions of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct, along with the ampulla of Vater [

3].

Diagnosis is usually made at an early stage, as biliary obstruction leads to early-onset symptoms, with jaundice being the most common presentation [

4,

5].

The majority of AC are adenocarcinomas and can be classified into 3 histological subtypes based on their epithelial origin: intestinal type, arising from intestinal epithelium; pancreaticobiliary type, originating from the biliary or pancreatic ductal epithelium; and mixed type, which contains features of both intestinal and pancreaticobiliary subtypes, with each component representing at least 25% of the tumor architecture [

2,

6]. Subtypes could differ in prognosis, with the intestinal type generally showing better outcomes [

1,

6]. However, data supporting histological subtype as an independent prognostic factor remain controversial [

7].

Due to the lack of robust prospective phase 3 clinical trials specific to AC, current treatment guidelines are largely extrapolated from evidence in colorectal, pancreatic, and biliary cancers, depending on the histological subtype [

8].

Surgery is the only potentially curative treatment. Despite the relatively early stage and resectability at diagnosis, more than 50% of patients experience relapse after surgery [

7,

9]. For resectable disease, nodal status and resection margins are recognized independent prognostic factors. Other potential prognostic indicators include perineural and lymphovascular invasion, tumor grade, and patient-related factors, including age and ECOG performance status [

10,

11]. The role of neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatments is not well defined due to a scarcity of evidence. For unresectable locally advanced or stage IV disease, systemic treatment is indicated, although the optimal treatment regimen remains unclear [

7,

8].

The aim of this study was to characterize the clinical and pathological features, treatment approaches, and outcomes of AC, and to explore potential prognostic factors in a cohort of patients diagnosed with ampullary carcinoma at our center between January 2015 and December 2023.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients with newly diagnosed AC at our institution between January 2015 and December 2023. Eligible patients had histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma and complete baseline clinical and pathological data. Patients with non-tubular histological patterns (e.g., medullary carcinoma, poorly cohesive cell carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma) or neuroendocrine tumors were excluded. All data were pseudonymized prior to analysis to maintain patient confidentiality. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Unidade Local de Saúde de São José, in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective observational nature of the study, no informed consent was required.

2.2. Variables and Data Collection

Data on demographics, clinical presentation, imaging findings, pathological characteristics (tumor size, lymph node status, histologic subtype and grade, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, and resection margins), and treatment modalities were extracted from electronic health records. Localized disease was defined as global TNM stage I–III, whereas metastatic disease was defined as TNM stage IV, according to the AJCC 8th edition classification. We further assessed prognostic factors associated with survival outcomes, including clinical, pathological, and treatment-related variables.

2.3. Objectives and Outcomes Definitions

The objectives were to evaluate recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with localized disease, OS and progression-free survival in the metastatic setting (PFSmet), and to identify clinical, pathological, and treatment-related prognostic factors.

OS was defined as the interval from diagnosis of AC to death from any cause in patients with localized disease, and from diagnosis of metastatic disease to death in patients with metastatic AC. RFS was defined as the interval from curative-intent surgery to the first documented recurrence or death, whichever occurred first. PFSmet was defined as the interval from diagnosis of metastatic AC to the first documented progression or death, whichever occurred first. For the calculation of OS, RFS, and PFSmet, the cut-off date was set at December 2023, and patients who had not experienced an event by this date were censored. Recurrence and progression were determined based on radiological or pathological evidence.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient and tumor characteristics. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared between groups using the log-rank test. Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were first used to evaluate the association of each variable with RFS and OS. Variables with p < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were then included in multivariate Cox regression models to identify independent prognostic factors. Hazard ratios (HRs) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 29.0.2.0.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 106 patients were included in the analysis. The clinical and demographic characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 69 years (interquartile range [IQR], 63-77 years), and the majority were male (n = 62, 58.5%). Most patients had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) ≤ 1 (n = 98, 92.5%). At diagnosis, 96.2% of patients (n = 102) presented with localized, resectable disease, most of which were classified as TNM stage III (n = 65, 61.3%). 4 patients (3.8%) had metastatic disease at diagnosis. The pancreaticobiliary subtype was the predominant histological type in the cohort (n = 48, 45.3%). The most frequently reported clinical presentation was obstructive jaundice (n = 91, 85.8%). Tumor marker increased levels (CA 19-9, CEA, or both) were observed in less than half of the patients (n = 50, 47.2%).

Surgery with curative intent was performed in 102 patients (96.2%), all with localized disease. 1 patient received neoadjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX. Positive resection margins were observed in 13 patients (12.7%), and positive lymph node involvement was present in 62 patients (60.8%). Lymphovascular and perineural invasion were identified in 55 (53.9%) and 44 (43.1%) patients, respectively. Grade 3 tumors were found in 25 patients (24.5%).

Marked differences were observed between the pancreaticobiliary and intestinal histologic subtypes. The pancreaticobiliary subtype displayed a more aggressive pathological profile, with higher frequencies of T3–T4 tumors (65.2% vs. 47.4%), node-positive disease (80.4% vs. 34.2%), lymphovascular invasion (69.6% vs. 42.1%), perineural invasion (63.0% vs. 26.3%), and R1 resection margins (17.4% vs. 10.5%). Grade 3 tumors were uncommon in the pancreaticobiliary subtype (4.3%), whereas the intestinal subtype exhibited a higher proportion of high-grade tumors (15.8%).

Adjuvant therapy was administered to 48 patients (47.1%), including 39 (38.2%) who received chemotherapy and 9 (8.8%) who underwent chemoradiotherapy. Gemcitabine and capecitabine were the most commonly used agents in chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy, respectively. A summary of the treatment regimens is provided in

Table 1.

Use of adjuvant therapy was more frequent in the pancreaticobiliary subtype (52.2% vs. 36.8%), and recurrence occurred more often in this group (30% vs. 21.1%), further supporting its overall more aggressive biological behavior.

Among patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis, 3 received palliative systemic treatment: FOLFIRINOX (n = 1), FOLFOX (n = 1), and gemcitabine (n = 1).

3.2. Outcomes

The median follow-up for the study cohort was 29.3 months (range, 1–113.6).

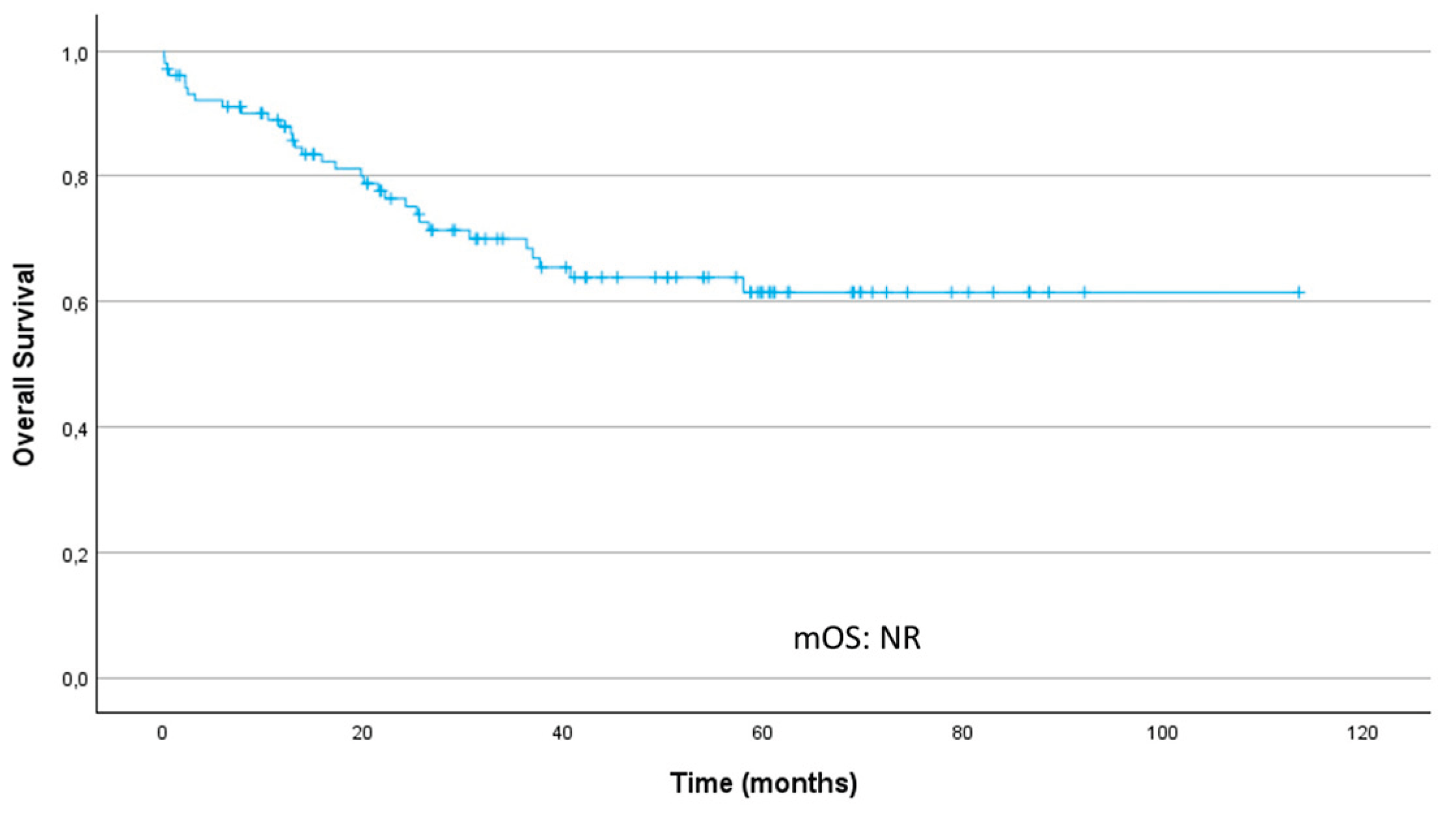

3.2.1. Overall Recurrence-Free Survival

In the localized setting, among patients who developed recurrence, the median time from surgery to recurrence was 25.7 months (IQR, 10.1–56.6). The median RFS (mRFS) for the overall population was not reached ([NR], 95% CI NR-NR). RFS rates at 24 and 36 months were 69.4% (95% CI 60.6–79.4) and 68.1% (95% CI 59.2–78.3), respectively.

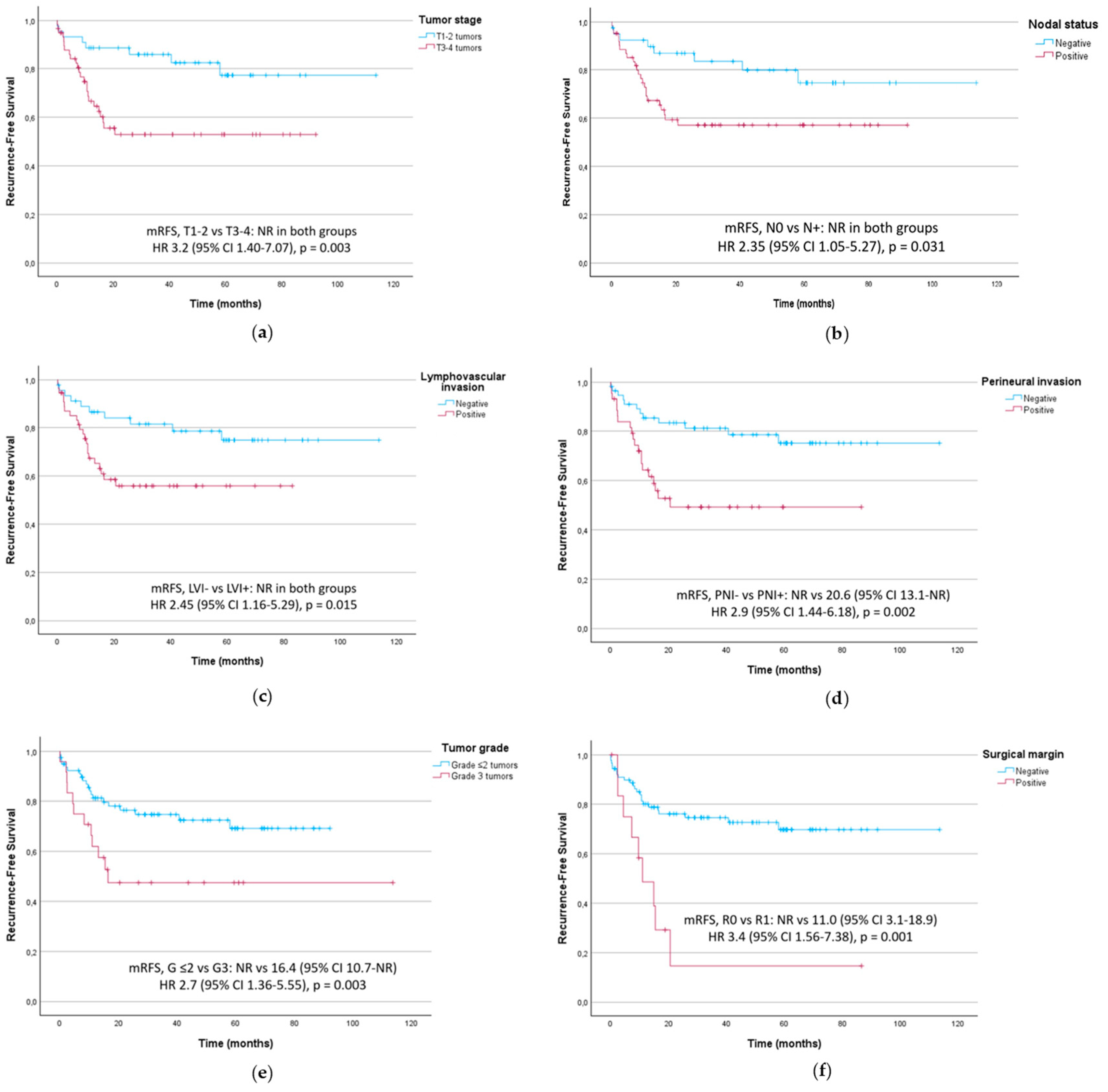

Figure 1 presents the overall RFS curve in localized disease.

Prognostic Factors for Recurrence-Free Survival

In univariate analysis, adverse prognostic factors for RFS included T3–T4 tumor stage (HR 3.2, 95% CI 1.40–7.07,

p = 0.003), node-positive disease (HR 2.35, 95% CI 1.05–5.27,

p = 0.031), lymphovascular invasion (HR 2.45, 95% CI 1.16–5.29,

p = 0.015), perineural invasion (HR 2.9, 95% CI 1.44–6.18,

p 0.002), histological grade 3 tumors (HR 2.7, 95% CI 1.36–5.55,

p = 0.003), and R1 resection margins (HR 4.06, 95% CI 1.85–8.92,

p <0.001), as shown in

Table 2.

Obstructive jaundice at diagnosis was associated with a trend toward longer RFS (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.30–2.40, p = 0.77). Perioperative tumor marker levels were not associated with RFS (CEA: HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.23–2.56, p = 0.853; CA 19-9: HR 1.46, 95% CI 0.72–2.92, p = 0.282).

In multivariate analysis, only R1 margin remained independently associated with shorter RFS (HR 2.5, 95% CI 1.02–5.94, p = 0.046).

All RFS analysis is shown in

Table 2.

Figure 2 presents RFS curves stratified by key prognostic factors in the univariate analysis.

Recurrence-Free Survival by Histological Subtype

The intestinal subtype showed a trend toward improved RFS compared with the pancreaticobiliary subtype, although the difference was not statistically significant (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.4 -1.7, p = 0.54).

We took the adverse prognostic factors from the global cohort and compared each factor between the intestinal and pancreaticobiliary histological subtypes. We found no significant differences for most prognostic factors, except for histological grade 3, which was associated with better RFS in the pancreaticobiliary subtype (HR 0.1, 95% CI 0.025-0.52,

p < 0.001). However, the small number of patients in each subgroup and the unequal distribution of grade 3 tumors (16% in the intestinal subtype vs. 4.3% in the pancreaticobiliary subtype) limit the robustness and statistical power of these findings. All results are shown in

Table 3.

Impact of Adjuvant Therapy on Recurrence-Free Survival

Receipt of adjuvant therapy was associated with a non-significant trend toward improved RFS in the overall population (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.40–1.50, p = 0.35). When analyzed by subtype, no significant associations were observed (intestinal: HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.29–3.16, p = 0.93; pancreaticobiliary: HR 1.11, 95% CI 0.39–3.22, p = 0.84). When adjusted for T stage, nodal status, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, tumor grade, and surgical margin, the HRs were 0.42 (95% CI 0.13–1.34, p = 0.14) for the pancreaticobiliary subtype and 0.52 (95% CI 0.06–4.50, p = 0.56) for the intestinal subtype. The small number of patients and wide confidence intervals limit the robustness and interpretability of these findings.

3.2.3. Overall Survival in Localized Disease

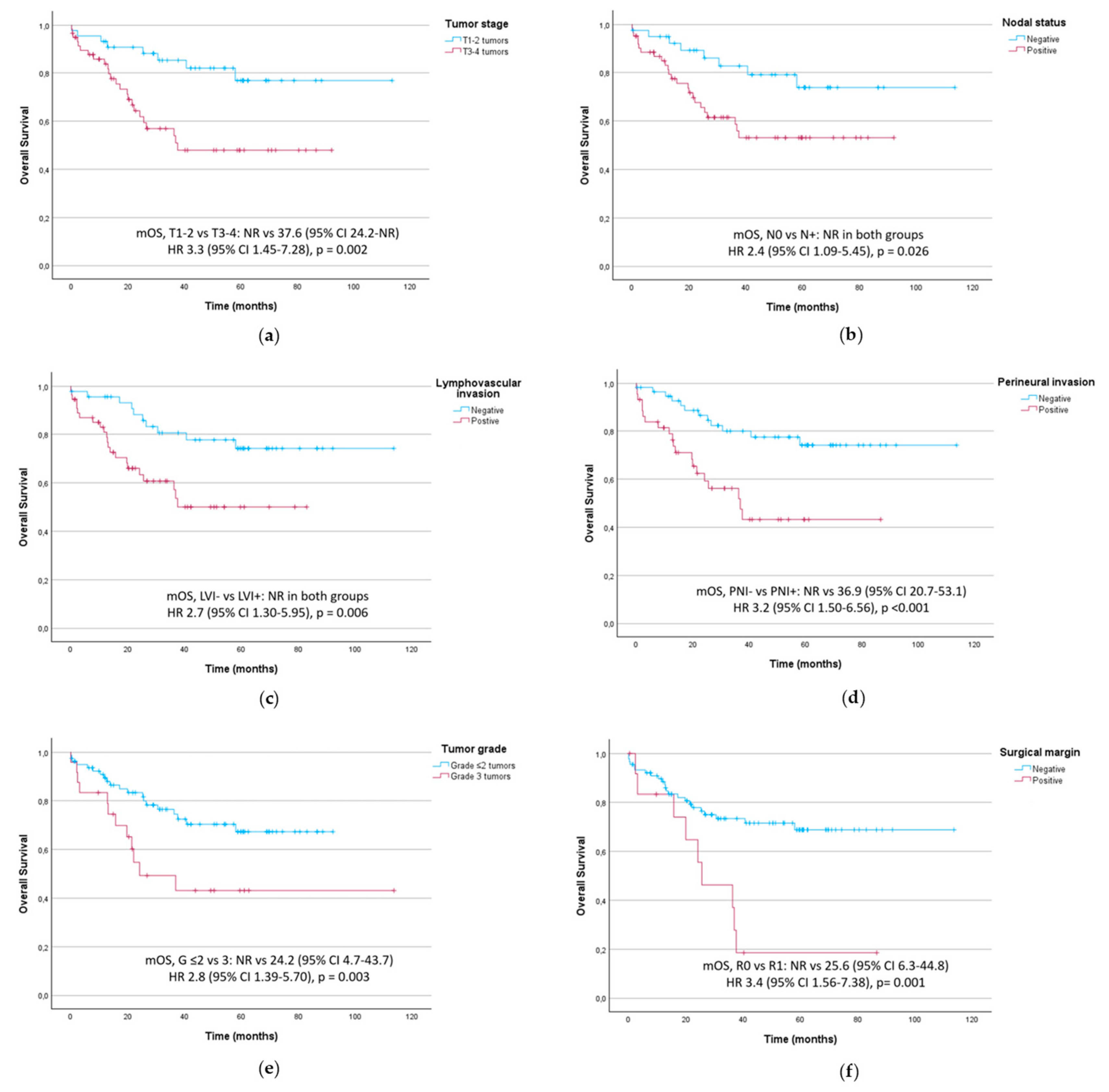

Prognostic Factors for Overall Survival

Worse OS was associated with T3–T4 tumors (HR 3.3, 95% CI 1.45-7.28,

p = 0.002), node-positive disease (HR 2.4, 95% CI 1.09-5.45,

p = 0.026), lymphovascular invasion (HR 2.7, 95% CI 1.30-5.95,

p = 0.006), perineural invasion (HR 3.2, 95% CI 1.50-6.56,

p < 0.001), grade 3 tumors (HR 2.8, 95% CI 1.39-5.70,

p = 0.003), and R1 margins (HR 3.4, 95% CI 1.56-7.38,

p = 0.001), as shown in

Table 4.

Figure 4 presents OS curves stratified by key prognostic factors in the univariate analysis.

An increase in perioperative tumor marker levels was not associated with OS (CEA: HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.22–2.43, p = 0.614; CA 19-9: HR 1.38, 95% CI 0.69–2.76, p = 0.362).

In multivariate analysis, no variables remained independently associated with OS (

Table 4).

Overall Survival by Histological Subtype

OS did not differ significantly between the intestinal and pancreaticobiliary subtypes (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.40–1.70,

p = 0.625). Subtype-specific analyses showed no significant differences for most prognostic factors, except that histological grade 3 was associated with better OS in the pancreaticobiliary subtype (HR 0.1, 95% CI 0.03-0.57,

p = 0.001). A trend toward worse OS was also observed for R1 resections in the pancreaticobiliary subtype. The small number of patients with R1 margins (10.5% in the intestinal subtype vs. 17.4% in the pancreaticobiliary subtype) and the unequal distribution of grade 3 tumors (15.8% in the intestinal subtype vs. 4.3% in the pancreaticobiliary subtype) limit the robustness and statistical power of these findings (

Table 4).

Impact of Adjuvant Therapy in Overall Survival

Adjuvant therapy was not significantly associated with OS in the overall population (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.35–1.45, p = 0.35). Analyses by histological subtype also showed no significant associations, either in univariate analysis (intestinal: HR 0.936, 95% CI 0.28–3.13, p = 0.91; pancreaticobiliary: HR 1.081, 95% CI 0.37–3.13, p = 0.89) or in analyses adjusted for T stage, nodal status, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, tumor grade, and surgical margin (intestinal: HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.05–4.87, p = 0.53; pancreaticobiliary: HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.14–1.41, p = 0.17). The small number of patients and wide confidence intervals limit the robustness and interpretability of these findings.

3.2.4. Survival Analysis in Metastatic Disease

In the metastatic setting, which included both patients with metastatic disease ab initio and those who developed metastases after curative-intent treatment, the mOS was 13.6 months (95% CI, 10.9–16.3). Among patients receiving first-line systemic therapy, mOS was 11.8 months (95% CI, 8.1–15.5), and the median duration of first-line treatment was 5.8 months (range, 1.0–15.5).

For first-line treatment, median PFSmet was 6.7 months (95% CI, 1.6-11.8). 5 patients received second-line treatment, whereas none received third-line systemic therapy.

4. Discussion

4.1. Prognostic Factors

In our cohort, T3–T4 stage, nodal involvement, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, high-grade histology (grade 3), and R1 margin were associated with both RFS and OS. However, multivariate analysis revealed that only R1 margin remained independently associated with poorer RFS, while none of the other factors were independently associated with OS. These findings are consistent with previously published data identifying these pathological features as markers of aggressive disease biology and poor prognosis, although not all reports have identified the same set of prognostic factors [

12]. For instance, Zhang X et al. (2022) identified T stage and lymphovascular invasion as the independent prognostic factors for recurrence and OS after curative resection [

9]. In another retrospective study, only lymph node status and surgical margin were independent predictors of poor prognosis, whereas T3–T4 tumors, margin positivity, lymph node involvement, lymphovascular and perineural invasion, and poor histologic grade were associated with OS in univariate analysis [

10]. A meta-analysis by Luchini et al. (2019), which included 2,379 patients, demonstrated that perineural invasion was strongly associated with both poorer survival and an increased risk of recurrence, further underscoring its prognostic significance [

13]. Similarly, Buyuktalanci et al. (2025) reported that lymphovascular invasion and margin positivity were independent prognostic markers, reinforcing the impact of these pathological features on patient outcomes [

14]. In contrast, Vilhordo et al. (2021) found that lymph node involvement was the only independent prognostic factor in their series [

11]. Taken together, these variations may reflect differences in sample size, patient selection, histopathologic assessment, and treatment strategies across institutions and study periods. Nonetheless, the overall convergence of evidence highlights the multifactorial nature of prognosis in AC and the importance of comprehensive pathologic evaluation and multidisciplinary management, particularly for patients with high-risk features who may benefit from more aggressive adjuvant approaches.

Regarding histological subtypes, our study did not identify a statistically significant difference in survival outcomes between the intestinal and pancreaticobiliary types of AC, which contrasts with several previously published retrospective studies, including multicenter cohorts, registry data, and meta-analyses, reporting poorer prognosis for the pancreaticobiliary subtype [

3,

12,

15,

16]. These studies often attribute this disparity to more aggressive tumor biology, higher rates of lymph node involvement, and more advanced stage at diagnosis in the pancreaticobiliary group [

3,

12,

15,

16]. Despite the absence of statistical significance in our findings, the established literature supports considering histological subtype as a potentially relevant factor in risk stratification and treatment planning, particularly when integrated with other prognostic indicators.

In our cohort, the presence of obstructive jaundice at diagnosis showed a trend toward improved prognosis, although this did not reach statistical significance. This might be explained better by earlier detection and a higher likelihood of curative resection among jaundiced patients, rather than a protective biological effect of jaundice itself [

5].

4.2. Adjuvant Treatment

Regarding adjuvant treatment, we found no statistically significant difference in outcomes between patients who received adjuvant therapy and those who did not. Evidence for adjuvant therapy in ampullary adenocarcinoma remains mixed. The European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer (ESPAC)-3 trial, a randomized phase III multicenter trial of patients with periampullary cancer (of whom 69% had AC) failed to demonstrate an OS benefit for routine adjuvant chemotherapy in the overall study population. However, multivariate analysis correcting for prognostic variables (age, poorly differentiated tumor grade, and lymph node) found a statistically significant survival benefit of chemotherapy [

17]. Aligned with these findings, a meta-analysis performed in 2017 by Acharya et al., including 1,671 patients who underwent curative surgery for periampullary adenocarcinoma, showed no significant survival benefit for adjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy compared with observation, and ampullary-specific outcomes were not separately reported [

18]. Several other retrospective studies also did not find a significant association between adjuvant treatment and improved OS or disease-free survival. For example, in a multicenter retrospective study of 357 patients with AC, adjuvant chemotherapy (fluorouracil or gemcitabine-based) with or without radiotherapy, was not associated with improved long-term OS after curative resection [

19]. Similarly, Kang et al., in a propensity score–matched analysis of 475 patients, reported no significant differences in OS or RFS between those receiving 5-FU plus leucovorin adjuvant chemotherapy and those managed with observation alone [

20].

By contrast, a meta-analysis by Nguyen-Phong Vo et al. (2021), including 3,538 patients from 27 studies, found that adjuvant therapy after curative resection significantly reduced mortality, with the greatest benefit seen for chemoradiotherapy. The effect was most pronounced in high-risk patients (tumors invading the surrounding structures of the ampulla, positive resection margins, poor histological differentiation, or lymph node metastasis) and in those with pancreaticobiliary subtype, whereas no clear benefit was observed for low-risk (tumors limited to the ampulla of Vater, negative surgical margins, moderate-to-well histological differentiation, no evidence of lymph node metastasis, or stage I cancer) or intestinal subtype tumors. Notably, adjuvant treatment was not significantly associated with improved disease-free survival [

21]. In a large national cohort study, Nassour et al. (2018) analyzed 4,190 patients with resected AC and found that both adjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy were associated with improved OS compared to observation, with the survival benefit particularly notable in patients with higher tumor and nodal stages [

22]. Similarly, a large German population-based study including 830 patients demonstrated that adjuvant chemotherapy significantly improves OS and disease-free survival in patients with advanced-stage disease, including T3–T4 tumors, lymph node metastases, and lymphovascular invasion [

23]. Nevertheless, the optimal adjuvant approach remains unclear, as no head-to-head trials have directly compared chemotherapy with chemoradiotherapy in AC.

The prospective ADAPTA trial (NCT06068023, [2023]) is a phase II study is currently evaluating tailored adjuvant chemotherapy in resected ampullary carcinoma, using CAPOX for intestinal and FOLFIRINOX for pancreaticobiliary or mixed subtypes, aiming to improve disease-free survival and provide prospective data to guide treatment strategies [

32].

Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for ampullary adenocarcinoma (Version 2.2025) recommend adjuvant chemotherapy largely based on extrapolation from colorectal, pancreatic, and biliary tract cancer data, in combination with expert consensus, reflecting the paucity of prospective evidence specific to ampullary cancers [

24]. No guidelines have yet been published by the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) or American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

4.3. Advanced Disease

In unresectable locally advanced or metastatic AC, as with adjuvant treatment, there is a lack of randomized phase III trials specifically addressing systemic therapy. The ABC-02 trial (2010), which included a small proportion of patients with AC, demonstrated improved OS with cisplatin plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in first-line advanced biliary tract cancer [33]. Similarly, the ABC-06 trial (2021), enrolling patients with advanced biliary tract cancers, including AC, reported a modest benefit of FOLFOX over active symptom control in the second-line setting [34]. Nevertheless, no studies have reported OS or progression-free survival (PFS) outcomes specifically for AC, and there remains no consensus on the optimal systemic chemotherapy regimen for this population. In practice, treatment recommendations are therefore extrapolated from phase III trials in colorectal, pancreatic, and biliary tract cancers, with guidance based on histologic subtype. For pancreaticobiliary or mixed subtypes, recommendations are based on pancreatic and biliary tract cancer trials, whereas for the intestinal subtype, they are derived from colorectal cancer trials [

24].

4.4. Future Perspectives

The role of molecular profiling is becoming increasingly important, particularly for identifying candidates for targeted therapies and immunotherapy. Although prospective trials specific to AC are lacking, these patients are often considered for tumor-agnostic therapies based on extrapolated evidence, as they were largely excluded from most basket studies. Notably, the KEYNOTE-158 trial, a nonrandomized, open-label, multicenter phase II study, evaluated pembrolizumab in previously treated advanced solid tumors with microsatellite instability–high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR), demonstrating durable responses across multiple tumor types, with greater efficacy in MSI-H/dMMR tumors, ultimately supporting its tumor-agnostic approval [

25,

26]. The DESTINY PanTumor 02 trial, a multicenter phase II basket study, evaluated trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with HER2 IHC 3+ solid tumors across multiple histologies, demonstrating robust and durable antitumor activity and providing pivotal evidence for its tumor-agnostic Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval [

27]. The NAVIGATE and STARTRK programs showed that tropomyosin kinase receptors inhibitors (larotrectinib and entrectinib, respectively) produce robust and durable responses in patients with neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase (NTRK) gene fusion tumors across diverse tumor types, supporting their tumor-agnostic approvals [

28,

29].

These data support current NCCN guidelines recommending comprehensive molecular testing in unresectable or metastatic AC [

24]. More recently, a retrospective study by Fabregat-Franco et al. (2025) showed that over half of ampullary carcinomas harbor potentially actionable molecular alterations, most frequently in ERBB2 and DNA repair pathways. This finding highlights the feasibility of precision-oncology approaches in this rare malignancy and underscores the need for prospective, biomarker-driven trials [

8].

Furthermore, the integration of multi-omic profiling, patient-derived models, and liquid biopsy approaches may enhance risk stratification, enable real-time monitoring of minimal residual disease, and support truly personalized therapeutic strategies. Ultimately, collaborative efforts and international registries will be essential to translate these advances into improved patient outcomes.

4.5. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations, including its retrospective design, relatively small sample size, and heterogeneity of treatments, all of which may limit statistical power and the generalizability of the findings.

5. Conclusions

Advanced T stage, nodal involvement, lymphovascular and perineural invasion, high-grade histology, and R1 resection margins were associated with outcomes in univariate analysis; however, only R1 margin remained an independent predictor in multivariate analysis. These findings highlight the importance of comprehensive pathological assessment and multidisciplinary treatment planning. Together with emerging molecular insights, they support the development of individualized therapeutic strategies in this rare malignancy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.F.; methodology, I.F., M.S., J.B.F.; software, I.F.; validation, I.F., J.B.F.; formal analysis, I.F.; investigation, I.F., N.G.; resources, I.F., N.G., M.S.; data curation, I.F., M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.F.; writing—review and editing, N.G., A.C., E.V., J.B.F., M.S.; visualization, I.F.; supervision, M.S., J.B.F.; project administration, I.F., J.B.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Unidade Local de Saúde de São José (Protocol 657, approved on 15 May 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Considering the retrospective observational nature of the study, no informed consent was required.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC |

Ampullary carcinoma |

| ASCO |

American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| CA 19-9 |

Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 |

| CAPOX |

Capecitabine + oxaliplatin |

| CEA |

Carcinoembryonic antigen |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| dMMR |

Mismatch repair deficiency |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| ECOG PS |

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status |

| ESMO |

European Society for Medical Oncology |

| FOLFIRINOX |

5-fluorouracil + leucovorin + irinotecan + oxaliplatin |

| FOLFOX |

5-fluorouracil + leucovorin + oxaliplatin |

| GEMOX |

Gemcitabine + oxaliplatin |

| GI |

Gastrointestinal |

| HR |

Hazard ratio |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| MSI-H |

Microsatellite instability–high |

| mOS |

Median overall survival |

| mPFS |

Median progression-free survival |

| NCCN |

National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| NR |

Not reached |

| NTRK |

Neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase |

| OS |

Overall survival |

| PFS |

Progression-free survival |

| PFSmet |

Progression-free survival in the metastatic setting |

| RFS |

Recurrence-free survival |

| TMB |

Tumor mutational burden |

References

- Rizzo, A; Dadduzio, V; Lombardi, L; Ricci, AD; Gadaleta-Caldarola, G. Ampullary carcinoma: An overview of a rare entity and discussion of current and future therapeutic challenges; Current Oncology. MDPI, 2021; Vol. 28, pp. 3393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, MA; Kratz, JD; Carlson, AS; Ascencio, YO; Kelley, BS; LoConte, NK. Molecular Targets and Therapies for Ampullary Cancer. In JNCCN Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network; Harborside Press, 2024; Vol. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H; Zhu, Y; Wu, YK. Ampulla of Vater carcinoma: advancement in the relationships between histological subtypes, molecular features, and clinical outcomes. In Frontiers in Oncology; Frontiers Media S.A., 2023; Vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, DH; Bekaii-Saab, T. Ampullary Cancer: An Overview; American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book, May 2014; Volume (34), pp. 112–5. [Google Scholar]

- Pea, A; Riva, G; Bernasconi, R; Sereni, E; Lawlor, RT; Scarpa, A; et al. Ampulla of Vater carcinoma: Molecular landscape and clinical implications. In World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology; Baishideng Publishing Group Co, 2018; Vol. 10, pp. 370–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, C; Wolk, S; Aust, DE; Meier, F; Saeger, HD; Ehehalt, F; et al. The pathohistological subtype strongly predicts survival in patients with ampullary carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2019, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsagkalidis, V; Langan, RC; Ecker, BL. Ampullary Adenocarcinoma: A Review of the Mutational Landscape and Implications for Treatment. In Cancers; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), 2023; Vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Fabregat-Franco, C; Castet, F; Castillo, G; Salcedo, M; Sierra, A; López-Valbuena, D; et al. Genomic profiling unlocks new treatment opportunities for ampullary carcinoma. ESMO Open 2025, 10(5), 104480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X; Sun, C; Li, Z; Wang, T; Zhao, L; Niu, P; et al. Brief Communication Long-term survival and pattern of recurrence in ampullary adenocarcinoma patients after curative Whipple’s resection: a retrospective cohort study in the National Cancer Center in China [Internet]. Am J Cancer Res 2022, Vol. 12. Available online: www.ajcr.us/.

- Demirci, NS; Cavdar, E; Ozdemir, NY; Yuksel, S; Iriagac, Y; Erdem, GU; et al. Clinicopathologic Analysis and Prognostic Factors for Survival in Patients with Operable Ampullary Carcinoma: A Multi-Institutional Retrospective Experience. Medicina (Lithuania) 2024, 60(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhordo, DW; Gregório, C; Valentini, DF; Edelweiss, MIA; Uchoa, DM; Osvaldt, AB. Prognostic Factors of Long-term Survival Following Radical Resection for Ampullary Carcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer 2021, 52(3), 872–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J; Zhang, Q; Li, P; Shan, Y; Zhao, D; Cai, J. Prognostic factors of carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater after surgery. Tumor Biology 2014, 35(2), 1143–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchini, C; Veronese, N; Nottegar, A; Riva, G; Pilati, C; Mafficini, A; et al. Perineural Invasion is a Strong Prognostic Moderator in Ampulla of Vater Carcinoma. Pancreas 2019, 48(1), 70–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyigit Buyuktalanci, D; Gun, E; Dilek, ON; Dilek, FH. Histopathological and prognostic variability of ampullary tumors: A comprehensive study on tumor location, histological subtypes, and survival outcomes. Ann Diagn Pathol 2025, 77, 152476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Placencia, RM; Montenegro, P; Guerrero, M; Serrano, M; Ortega, E; Bravo, M; et al. Survival after curative pancreaticoduodenectomy for ampullary adenocarcinoma in a South American population: A retrospective cohort study. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2022, 14(1), 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappo, G; Galvanin, J; Gentile, D; Capretti, G; Pulvirenti, A; Bozzarelli, S; et al. Long-term outcomes after pancreatoduodenectomy for ampullary cancer: The influence of the histological subtypes and comparison with the other periampullary neoplasms. Pancreatology 2021, 21(5), 950–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neoptolemos, JP; Moore, MJ; Cox, TF; Valle, JW; Palmer, DH; McDonald, AC; et al. Effect of Adjuvant Chemotherapy With Fluorouracil Plus Folinic Acid or Gemcitabine vs Observation on Survival in Patients With Resected Periampullary Adenocarcinoma. JAMA 2012, 308(2), 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A; Markar, SR; Sodergren, MH; Malietzis, G; Darzi, A; Athanasiou, T; et al. Meta-analysis of adjuvant therapy following curative surgery for periampullary adenocarcinoma. British Journal of Surgery 2017, 104(7), 814–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, BL; Vollmer, CM; Behrman, SW; Allegrini, V; Aversa, J; Ball, CG; et al. Role of Adjuvant Multimodality Therapy After Curative-Intent Resection of Ampullary Carcinoma. JAMA Surg 2019, 154(8), 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J; Lee, W; Shin, J; Park, Y; Kwon, JW; Jun, E; et al. Controversial benefit of 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin-based adjuvant chemotherapy for ampullary cancer: a propensity score-matched analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2022, 407(3), 1091–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, NP; Nguyen, HS; Loh, EW; Tam, KW. Efficacy and safety of adjuvant therapy after curative surgery for ampullary carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery 2021, 170(4), 1205–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassour, I; Hynan, LS; Christie, A; Minter, RM; Yopp, AC; Choti, MA; et al. Association of Adjuvant Therapy with Improved Survival in Ampullary Cancer: A National Cohort Study. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2018, 22(4), 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duhn, J; Strässer, J; von Fritsch, L; Braun, R; Honselmann, KC; Kist, M; et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy Is Associated with Improved Survival in Advanced Ampullary Adenocarcinoma—A Population-Based Analysis by the German Cancer Registry Group. J Clin Med. 2025, 14(11), 3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 20]. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Ampullary Adenocarcinoma, Version 2.2025. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/ampullary.pdf.

- Marabelle, A; Le, DT; Ascierto, PA; Di Giacomo, AM; De Jesus-Acosta, A; Delord, JP; et al. Efficacy of Pembrolizumab in Patients With Noncolorectal High Microsatellite Instability/Mismatch Repair–Deficient Cancer: Results From the Phase II KEYNOTE-158 Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2020, 38(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marabelle, A; Fakih, M; Lopez, J; Shah, M; Shapira-Frommer, R; Nakagawa, K; et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol 2020, 21(10), 1353–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meric-Bernstam, F; Makker, V; Oaknin, A; Oh, DY; Banerjee, S; González-Martín, A; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Patients With HER2-Expressing Solid Tumors: Primary Results From the DESTINY-PanTumor02 Phase II Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2024, 42(1), 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drilon, A; Laetsch, TW; Kummar, S; DuBois, SG; Lassen, UN; Demetri, GD; et al. Efficacy of Larotrectinib in TRK Fusion–Positive Cancers in Adults and Children. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 378(8), 731–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, D.B. Larotrectinib and Entrectinib: TRK Inhibitors for the Treatment of Pediatric and Adult Patients With NTRK Gene Fusion. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2020, 11(4). [Google Scholar]

- Valle, J; Wasan, H; Palmer, DH. ABC-02 Trial Investigators. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med 2010, 362(14), 1273-1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarca, A; Palmer, DH; Wasan, H. ABC-06 Trial Investigators. Second-line chemotherapy for advanced biliary tract cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22(5), 690-701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondazione Poliambulanza Istituto Ospedaliero. The ADAPTA Study: ADjuvant chemotherAPy after curative-intent resection of ampullary cancer. 2023. ClinicalTrials.gov NCT06068023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).