Submitted:

29 January 2026

Posted:

30 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

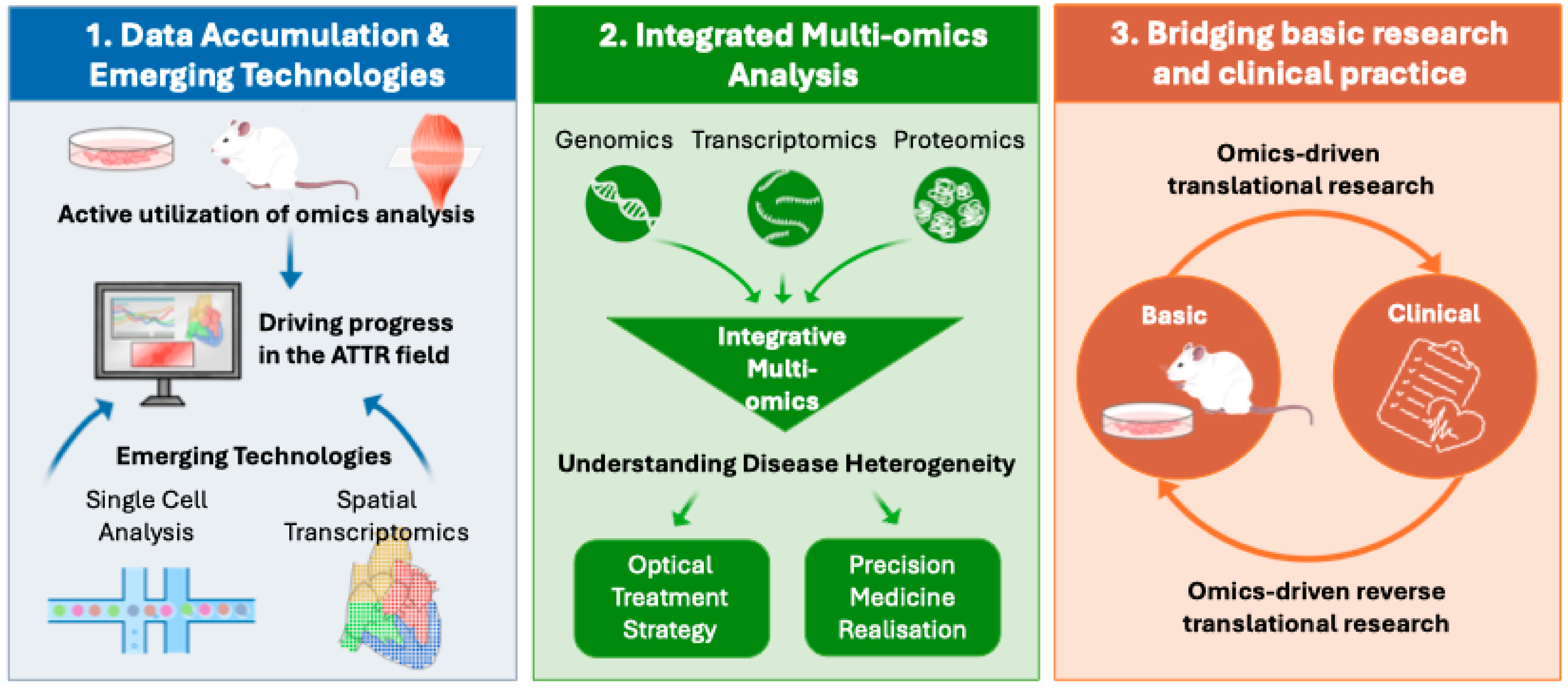

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Overview of Tansthyretin Amyloidosis

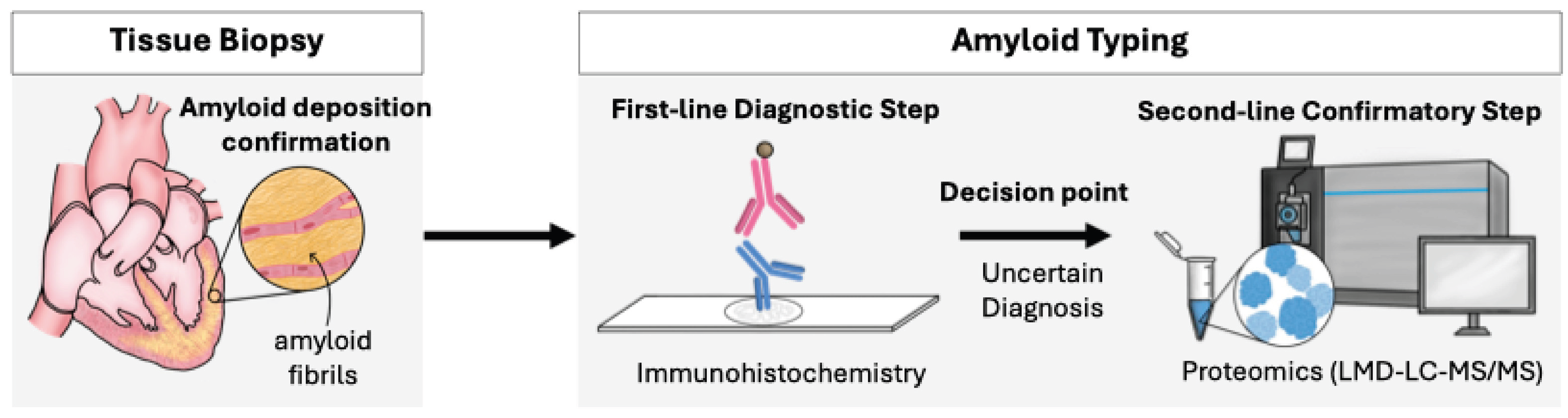

2. Application of Proteomics for Amyloid Typing in Clinical Practice

3. Research Applications of Omics in Patient Sample Analysis

3.1. Serum Biomarker Discovery

3.2. Tissue Sample Analysis

3.3. Genomic Analysis of Patients with Wild-Type Transthyretin Amyloidosis

4. Application of Omics in Preclinical Models

5. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruberg, F.L.; Grogan, M.; Hanna, M.; Kelly, J.W.; Maurer, M.S. Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019, 73, 2872–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, M.; Berk, J.L.; Drachman, B.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Hanna, M.; Lairez, O.; Witteles, R. Changing Treatment Landscape in Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circ Heart Fail 2025, 18, e012112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaoka, H.; Izumi, C.; Izumiya, Y.; Inomata, T.; Ueda, M.; Kubo, T.; Koyama, J.; Sano, M.; Sekijima, Y.; Tahara, N.; Tsukada, N.; Tsujita, K.; Tsutsui, H.; Tomita, T.; Amano, M.; Endo, J.; Okada, A.; Oda, S.; Takashio, S.; Baba, Y.; Misumi, Y.; Yazaki, M.; Anzai, T.; Ando, Y.; Isobe, M.; Kimura, T.; Fukuda, K. JCS 2020 Guideline on Diagnosis and Treatment of Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circ J 2020, 84, 1610–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, T.R.; Wiseman, R.L.; Kelly, J.W. The pathway by which the tetrameric protein transthyretin dissociates. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 15525–15533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Colón, W.; Kelly, J.W. The acid-mediated denaturation pathway of transthyretin yields a conformational intermediate that can self-assemble into amyloid. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 6470–6482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintas, A.; Vaz, D.C.; Cardoso, I.; Saraiva, M.J.; Brito, R.M. Tetramer dissociation and monomer partial unfolding precedes protofibril formation in amyloidogenic transthyretin variants. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 27207–27213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Lopez, E.; Maurer, M.S.; Garcia-Pavia, P. Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy: a paradigm for advancing precision medicine. Eur Heart J 2025, 46, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gertz, M.A.; Dispenzieri, A.; Sher, T. Pathophysiology and treatment of cardiac amyloidosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015, 12, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemer, J.M.; Grote-Levi, L.; Hänselmann, A.; Sassmann, M.L.; Nay, S.; Ratuszny, D.; Körner, S.; Seeliger, T.; Hümmert, M.W.; Dohrn, M.F.; Huss, A.; Tumani, H.; Gödecke, V.; Heuser, M.; Bauersachs, J.; Bavendiek, U.; Skripuletz, T.; Gingele, S. Polyneuropathy in hereditary and wildtype transthyretin amyloidosis, comparison of key clinical features and red flags. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 35028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchtar, E.; Dispenzieri, A.; Magen, H.; Grogan, M.; Mauermann, M.; McPhail, E.D.; Kurtin, P.J.; Leung, N.; Buadi, F.K.; Dingli, D.; Kumar, S.K.; Gertz, M.A. Systemic amyloidosis from A (AA) to T (ATTR): a review. J Intern Med 2021, 289, 268–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Ueda, M.; Jono, H.; Irie, H.; Sei, A.; Ide, J.; Ando, Y.; Mizuta, H. Wild-type transthyretin-derived amyloidosis in various ligaments and tendons. Hum Pathol 2011, 42, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruberg, F.L.; Maurer, M.S. Cardiac Amyloidosis Due to Transthyretin Protein: A Review. Jama 2024, 331, 778–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, M.; Sekijima, Y.; Yazaki, M.; Tojo, K.; Yoshinaga, T.; Doden, T.; Koyama, J.; Yanagisawa, S.; Ikeda, S. Carpal tunnel syndrome: a common initial symptom of systemic wild-type ATTR (ATTRwt) amyloidosis. Amyloid 2016, 23, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-López, E.; Gallego-Delgado, M.; Guzzo-Merello, G.; de Haro-Del Moral, F.J.; Cobo-Marcos, M.; Robles, C.; Bornstein, B.; Salas, C.; Lara-Pezzi, E.; Alonso-Pulpon, L.; Garcia-Pavia, P. Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis as a cause of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 2015, 36, 2585–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, A.; Narotsky, D.L.; Hamid, N.; Khalique, O.K.; Morgenstern, R.; DeLuca, A.; Rubin, J.; Chiuzan, C.; Nazif, T.; Vahl, T.; George, I.; Kodali, S.; Leon, M.B.; Hahn, R.; Bokhari, S.; Maurer, M.S. Unveiling transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis and its predictors among elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Eur Heart J 2017, 38, 2879–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbouEzzeddine, O.F.; Davies, D.R.; Scott, C.G.; Fayyaz, A.U.; Askew, J.W.; McKie, P.M.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Johnson, G.B.; Dunlay, S.M.; Borlaug, B.A.; Chareonthaitawee, P.; Roger, V.L.; Dispenzieri, A.; Grogan, M.; Redfield, M.M. Prevalence of Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol 2021, 6, 1267–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, L.; Labella, B.; Cotti Piccinelli, S.; Caria, F.; Risi, B.; Damioli, S.; Padovani, A.; Filosto, M. Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis: a comprehensive review with a focus on peripheral neuropathy. Front Neurol 2023, 14, 1242815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillmore, J.D.; Maurer, M.S.; Falk, R.H.; Merlini, G.; Damy, T.; Dispenzieri, A.; Wechalekar, A.D.; Berk, J.L.; Quarta, C.C.; Grogan, M.; Lachmann, H.J.; Bokhari, S.; Castano, A.; Dorbala, S.; Johnson, G.B.; Glaudemans, A.W.; Rezk, T.; Fontana, M.; Palladini, G.; Milani, P.; Guidalotti, P.L.; Flatman, K.; Lane, T.; Vonberg, F.W.; Whelan, C.J.; Moon, J.C.; Ruberg, F.L.; Miller, E.J.; Hutt, D.F.; Hazenberg, B.P.; Rapezzi, C.; Hawkins, P.N. Nonbiopsy Diagnosis of Cardiac Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Circulation 2016, 133, 2404–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergaro, G.; Ferrari Chen, Y.F.; Ioannou, A.; Panichella, G.; Castiglione, V.; Aimo, A.; Emdin, M.; Fontana, M. Current and emerging treatment options for transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. Heart 2026, 112, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, O.; Kamna, D.; Masri, A. New therapies to treat cardiac amyloidosis. Curr Opin Cardiol 2025, 40, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillmore, J.D.; Judge, D.P.; Cappelli, F.; Fontana, M.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Gibbs, S.; Grogan, M.; Hanna, M.; Hoffman, J.; Masri, A.; Maurer, M.S.; Nativi-Nicolau, J.; Obici, L.; Poulsen, S.H.; Rockhold, F.; Shah, K.B.; Soman, P.; Garg, J.; Chiswell, K.; Xu, H.; Cao, X.; Lystig, T.; Sinha, U.; Fox, J.C. Efficacy and Safety of Acoramidis in Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2024, 390, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, M.; Berk, J.L.; Gillmore, J.D.; Witteles, R.M.; Grogan, M.; Drachman, B.; Damy, T.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Taubel, J.; Solomon, S.D.; Sheikh, F.H.; Tahara, N.; González-Costello, J.; Tsujita, K.; Morbach, C.; Pozsonyi, Z.; Petrie, M.C.; Delgado, D.; Van der Meer, P.; Jabbour, A.; Bondue, A.; Kim, D.; Azevedo, O.; Hvitfeldt Poulsen, S.; Yilmaz, A.; Jankowska, E.A.; Algalarrondo, V.; Slugg, A.; Garg, P.P.; Boyle, K.L.; Yureneva, E.; Silliman, N.; Yang, L.; Chen, J.; Eraly, S.A.; Vest, J.; Maurer, M.S. Vutrisiran in Patients with Transthyretin Amyloidosis with Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2025, 392, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillmore, J.D.; Gane, E.; Taubel, J.; Kao, J.; Fontana, M.; Maitland, M.L.; Seitzer, J.; O'Connell, D.; Walsh, K.R.; Wood, K.; Phillips, J.; Xu, Y.; Amaral, A.; Boyd, A.P.; Cehelsky, J.E.; McKee, M.D.; Schiermeier, A.; Harari, O.; Murphy, A.; Kyratsous, C.A.; Zambrowicz, B.; Soltys, R.; Gutstein, D.E.; Leonard, J.; Sepp-Lorenzino, L.; Lebwohl, D. CRISPR-Cas9 In Vivo Gene Editing for Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, M.; Solomon, S.D.; Kachadourian, J.; Walsh, L.; Rocha, R.; Lebwohl, D.; Smith, D.; Täubel, J.; Gane, E.J.; Pilebro, B.; Adams, D.; Razvi, Y.; Olbertz, J.; Haagensen, A.; Zhu, P.; Xu, Y.; Leung, A.; Sonderfan, A.; Gutstein, D.E.; Gillmore, J.D. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing with Nexiguran Ziclumeran for ATTR Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2024, 391, 2231–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Pavia, P.; Aus dem Siepen, F.; Donal, E.; Lairez, O.; van der Meer, P.; Kristen, A.V.; Mercuri, M.F.; Michalon, A.; Frost, R.J.A.; Grimm, J.; Nitsch, R.M.; Hock, C.; Kahr, P.C.; Damy, T. Phase 1 Trial of Antibody NI006 for Depletion of Cardiac Transthyretin Amyloid. N Engl J Med 2023, 389, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanelli, L.; Sendoya, J.M.; Brody, S.; Galeano, P.; Do Carmo, S.; Cuello, A.C.; Castaño, E.M.; Gonzalés-Jimenez, A.; Verheul, J.; Medina-Vera, D.; de Fonseca, F.R.; Wernersson, R.; Morelli, L. New insights into the molecular biology of Alzheimer's-like cerebral amyloidosis achieved through multi-omics approaches. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0330859. [Google Scholar]

- Sancesario, G.M.; Bernardini, S. Alzheimer's disease in the omics era. Clin Biochem 2018, 59, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellenguez, C.; Küçükali, F.; Jansen, I.E.; Kleineidam, L.; Moreno-Grau, S.; Amin, N.; Naj, A.C.; Campos-Martin, R.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Andrade, V.; Holmans, P.A.; Boland, A.; Damotte, V.; van der Lee, S.J.; Costa, M.R.; Kuulasmaa, T.; Yang, Q.; de Rojas, I.; Bis, J.C.; Yaqub, A.; Prokic, I.; Chapuis, J.; Ahmad, S.; Giedraitis, V.; Aarsland, D.; Garcia-Gonzalez, P.; Abdelnour, C.; Alarcón-Martín, E.; Alcolea, D.; Alegret, M.; Alvarez, I.; Álvarez, V.; Armstrong, N.J.; Tsolaki, A.; Antúnez, C.; Appollonio, I.; Arcaro, M.; Archetti, S.; Pastor, A.A.; Arosio, B.; Athanasiu, L.; Bailly, H.; Banaj, N.; Baquero, M.; Barral, S.; Beiser, A.; Pastor, A.B.; Below, J.E.; Benchek, P.; Benussi, L.; Berr, C.; Besse, C.; Bessi, V.; Binetti, G.; Bizarro, A.; Blesa, R.; Boada, M.; Boerwinkle, E.; Borroni, B.; Boschi, S.; Bossù, P.; Bråthen, G.; Bressler, J.; Bresner, C.; Brodaty, H.; Brookes, K.J.; Brusco, L.I.; Buiza-Rueda, D.; Bûrger, K.; Burholt, V.; Bush, W.S.; Calero, M.; Cantwell, L.B.; Chene, G.; Chung, J. New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Nat Genet 2022, 54, 412–436. [Google Scholar]

- Dasari, S.; Theis, J.D.; Vrana, J.A.; Rech, K.L.; Dao, L.N.; Howard, M.T.; Dispenzieri, A.; Gertz, M.A.; Hasadsri, L.; Highsmith, W.E.; Kurtin, P.J.; McPhail, E.D. Amyloid Typing by Mass Spectrometry in Clinical Practice: a Comprehensive Review of 16,175 Samples. Mayo Clin Proc 2020, 95, 1852–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrana, J.A.; Gamez, J.D.; Madden, B.J.; Theis, J.D.; Bergen, H.R., 3rd; Dogan, A. Classification of amyloidosis by laser microdissection and mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis in clinical biopsy specimens. Blood 2009, 114, 4957–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrana, J.A.; Theis, J.D.; Dasari, S.; Mereuta, O.M.; Dispenzieri, A.; Zeldenrust, S.R.; Gertz, M.A.; Kurtin, P.J.; Grogg, K.L.; Dogan, A. Clinical diagnosis and typing of systemic amyloidosis in subcutaneous fat aspirates by mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Haematologica 2014, 99, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, S.; Vrana, J.A.; Theis, J.D.; Leung, N.; Sethi, A.; Nasr, S.H.; Fervenza, F.C.; Cornell, L.D.; Fidler, M.E.; Dogan, A. Laser microdissection and mass spectrometry-based proteomics aids the diagnosis and typing of renal amyloidosis. Kidney Int 2012, 82, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezk, T.; Gilbertson, J.A.; Mangione, P.P.; Rowczenio, D.; Rendell, N.B.; Canetti, D.; Lachmann, H.J.; Wechalekar, A.D.; Bass, P.; Hawkins, P.N.; Bellotti, V.; Taylor, G.W.; Gillmore, J.D. The complementary role of histology and proteomics for diagnosis and typing of systemic amyloidosis. J Pathol Clin Res 2019, 5, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriyama, H.; Kitakata, H.; Endo, J.; Ikura, H.; Sano, M.; Tasaki, M.; Sakai, S.; Ueda, M.; Fukuda, K. Step-by-step typing for the accurate diagnosis of concurrent light chain and transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. ESC Heart Fail 2022, 9, 1474–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.G.; Koch, C.M.; Connors, L.H. Serum Proteomic Variability Associated with Clinical Phenotype in Familial Transthyretin Amyloidosis (ATTRm). J Proteome Res 2017, 16, 4104–4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.G.; Koch, C.M.; Connors, L.H. Blood Proteomic Profiling in Inherited (ATTRm) and Acquired (ATTRwt) Forms of Transthyretin-Associated Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Proteome Res 2017, 16, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Gonzalez-Duarte, A.; O'Riordan, W.D.; Yang, C.C.; Ueda, M.; Kristen, A.V.; Tournev, I.; Schmidt, H.H.; Coelho, T.; Berk, J.L.; Lin, K.P.; Vita, G.; Attarian, S.; Planté-Bordeneuve, V.; Mezei, M.M.; Campistol, J.M.; Buades, J.; Brannagan, T.H., 3rd; Kim, B.J.; Oh, J.; Parman, Y.; Sekijima, Y.; Hawkins, P.N.; Solomon, S.D.; Polydefkis, M.; Dyck, P.J.; Gandhi, P.J.; Goyal, S.; Chen, J.; Strahs, A.L.; Nochur, S.V.; Sweetser, M.T.; Garg, P.P.; Vaishnaw, A.K.; Gollob, J.A.; Suhr, O.B. Patisiran, an RNAi Therapeutic, for Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ticau, S.; Sridharan, G.V.; Tsour, S.; Cantley, W.L.; Chan, A.; Gilbert, J.A.; Erbe, D.; Aldinc, E.; Reilly, M.M.; Adams, D.; Polydefkis, M.; Fitzgerald, K.; Vaishnaw, A.; Nioi, P. Neurofilament Light Chain as a Biomarker of Hereditary Transthyretin-Mediated Amyloidosis. Neurology 2021, 96, e412–e422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.S.; Razvi, Y.; O'Donnell, L.; Veleva, E.; Heslegrave, A.; Zetterberg, H.; Vucic, S.; Kiernan, M.C.; Rossor, A.M.; Gillmore, J.D.; Reilly, M.M. Serum neurofilament light chain in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis: validation in real-life practice. Amyloid 2024, 31, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, K.; Lin, C.Y.; Monteiro, C.; Coelho, T.; Moresco, J.J.; Pinto, A.F.M.; Powers, E.T.; Yates, J.R., 3rd; Diedrich, J.K.; Kelly, J.W. Plasma Proteome Profiling Reveals Inflammation Markers and Tafamidis Effects in V30M Transthyretin Polyneuropathy. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26((12)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, M.; Hellman, U.; Wixner, J.; Anan, I. Metabolomics analysis for diagnosis and biomarker discovery of transthyretin amyloidosis. Amyloid 2021, 28, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waś, J.; Gawor-Prokopczyk, M.; Sioma, A.; Szewczyk, R.; Pel, A.; Krzysztoń-Russjan, J.; Niedolistek, M.; Sokołowska, D.; Grzybowski, J.; Mazurkiewicz, Ł. Proteomic Analysis of Serum in Cardiac Transthyretin Amyloidosis: Diagnostic and Prognostic Implications for Biomarker Discovery. Biomedicines 2025, 13((7)). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akita, K.; Maurer, M.S.; Tower-Rader, A.; Fifer, M.A.; Shimada, Y.J. Comprehensive Proteomics Profiling Identifies Circulating Biomarkers to Distinguish Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy From Other Cardiomyopathies With Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. Circ Heart Fail 2025, 18, e012434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourelis, T.V.; Dasari, S.S.; Dispenzieri, A.; Maleszewski, J.J.; Redfield, M.M.; Fayyaz, A.U.; Grogan, M.; Ramirez-Alvarado, M.; Abou Ezzeddine, O.F.; McPhail, E.D. A Proteomic Atlas of Cardiac Amyloid Plaques. JACC CardioOncol 2020, 2, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, S.; Theis, J.D.; Vrana, J.A.; Fervenza, F.C.; Sethi, A.; Qian, Q.; Quint, P.; Leung, N.; Dogan, A.; Nasr, S.H. Laser microdissection and proteomic analysis of amyloidosis, cryoglobulinemic GN, fibrillary GN, and immunotactoid glomerulopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013, 8, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netzel, B.C.; Charlesworth, M.C.; Johnson, K.L.; French, A.J.; Dispenzieri, A.; Maleszewski, J.J.; McPhail, E.D.; Grogan, M.; Redfield, M.M.; Weivoda, M.; Muchtar, E.; Gertz, M.A.; Kumar, S.K.; Misra, P.; Vrana, J.; Theis, J.; Hayman, S.R.; Ramirez-Alvarado, M.; Dasari, S.; Kourelis, T. Whole tissue proteomic analyses of cardiac ATTR and AL unveil mechanisms of tissue damage. Amyloid 2025, 32, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carry, B.J.; Young, K.; Fielden, S.; Kelly, M.A.; Sturm, A.C.; Avila, J.D.; Martin, C.L.; Kirchner, H.L.; Fornwalt, B.K.; Haggerty, C.M. Genomic Screening for Pathogenic Transthyretin Variants Finds Evidence of Underdiagnosed Amyloid Cardiomyopathy From Health Records. JACC CardioOncol 2021, 3, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, N.; Nicholls, H.L.; Chahal, C.A.A.; Khanji, M.Y.; Rauseo, E.; Chadalavada, S.; Petersen, S.E.; Munroe, P.B.; Elliott, P.M.; Lopes, L.R. Prevalence, Cardiac Phenotype, and Outcomes of Transthyretin Variants in the UK Biobank Population. JAMA Cardiol 2024, 9, 964–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, O.M.; Clemmensen, T.S.; Hansen, A.T.; Gustafsson, F.; Poulsen, S.H. Familial occurrences of cardiac wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis: a case series. Eur Heart J Case Rep 2024, 8, ytae199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gázquez, I.; Pérez-Palacios, R.; Abengochea-Quílez, L.; Lahuerta Pueyo, C.; Roteta Unceta Barrenechea, A.; Andrés Gracia, A.; Aibar Arregui, M.A.; Menao Guillén, S. Targeted sequencing of selected functional genes in patients with wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis. BMC Res Notes 2023, 16, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittloff, K.T.; Iezzi, A.; Zhong, J.X.; Mohindra, P.; Desai, T.A.; Russell, B. Transthyretin amyloid fibrils alter primary fibroblast structure, function, and inflammatory gene expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2021, 321, H149–H160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Yang, Q.; Ullate-Agote, A.; Sampaio-Pinto, V.; Florit, L.; Dokter, I.; Mathioudaki, C.; Middelberg, L.; Montero-Calle, P.; Aguirre-Ruiz, P.; de Las Heras Rojo, J.; Lei, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wei, J.; van der Harst, P.; Prosper, F.; Mazo, M.M.; Iglesias-García, O.; Minnema, M.C.; Sluijter, J.P.G.; Oerlemans, M.; van Mil, A. Uncovering cell type-specific phenotypes using a novel human in vitro model of transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. Stem Cell Res Ther 2025, 16, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Villacorta-Martin, C.; Lindstrom-Vautrin, J.; Kenney, D.; Golden, C.S.; Edwards, C.V.; Sanchorawala, V.; Connors, L.H.; Giadone, R.M.; Murphy, G.J. Mapping cellular response to destabilized transthyretin reveals cell- and amyloidogenic protein-specific signatures. Amyloid 2023, 30, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reixach, N.; Deechongkit, S.; Jiang, X.; Kelly, J.W.; Buxbaum, J.N. Tissue damage in the amyloidoses: Transthyretin monomers and nonnative oligomers are the major cytotoxic species in tissue culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 2817–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.; Nah, S.K.; Reid, W.; Ebata, A.; Koch, C.M.; Monti, S.; Genereux, J.C.; Wiseman, R.L.; Wolozin, B.; Connors, L.H.; Berk, J.L.; Seldin, D.C.; Mostoslavsky, G.; Kotton, D.N.; Murphy, G.J. Induced pluripotent stem cell modeling of multisystemic, hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. Stem Cell Reports 2013, 1, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giadone, R.M.; Liberti, D.C.; Matte, T.M.; Rosarda, J.D.; Torres-Arancivia, C.; Ghosh, S.; Diedrich, J.K.; Pankow, S.; Skvir, N.; Jean, J.C.; Yates, J.R., 3rd; Wilson, A.A.; Connors, L.H.; Kotton, D.N.; Wiseman, R.L.; Murphy, G.J. Expression of Amyloidogenic Transthyretin Drives Hepatic Proteostasis Remodeling in an Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Model of Systemic Amyloid Disease. Stem Cell Reports 2020, 15, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.B.; Liu, Y.T.; Yeh, S.Y.; Tsai, J.W. Contributions of Animal Models to the Mechanisms and Therapies of Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Qiu, Z.; Fan, Y.; Xiong, Q.; Lei, Z.; Wei, J.; van der Harst, P.; Minnema, M.C.; Sluijter, J.P.G.; van Mil, A.; Oerlemans, M. In vitro and in vivo disease models of cardiac amyloidosis: progress, pitfalls, and potential. Cardiovasc Res 2025(121), 1997–2013. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Kanazashi, H.; Tokashiki, Y.; Fujikawa, R.; Okagaki, A.; Katoh, S.; Kojima, K.; Haruna, K.; Matsushita, N.; Ishikawa, T.O.; Chen, H.; Yamamura, K. TTR exon-humanized mouse optimal for verifying new therapies for FAP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2022, 599, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, S.; Sato, Y.; Chosa, K.; Ezawa, E.; Yamauchi, Y.; Oyama, M.; Kozuka-Hata, H.; Ito, R.; Sato, R.; Maeki, M.; Ishikawa, T.O.; Yamamura, K.; Takeshita, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kochi, Y.; Hashiya, F.; Liu, Y.; Abe, N.; Abe, H.; Sekijima, Y.; Yoshimi, K.; Mashimo, T. CRISPR-Cas3-based editing for targeted deletions in a mouse model of transthyretin amyloidosis. Nat Biotechnol 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, A.; Massa, P.; Patel, R.K.; Razvi, Y.; Porcari, A.; Rauf, M.U.; Jiang, A.; Cabras, G.; Filisetti, S.; Bolhuis, R.E.; Bandera, F.; Venneri, L.; Martinez-Naharro, A.; Law, S.; Kotecha, T.; Virsinskaite, R.; Knight, D.S.; Emdin, M.; Petrie, A.; Lachmann, H.; Wechelakar, A.; Petrie, M.; Hughes, A.; Freemantle, N.; Hawkins, P.N.; Whelan, C.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Gillmore, J.D.; Fontana, M. Conventional heart failure therapy in cardiac ATTR amyloidosis. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 2893–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.K.; Vasbinder, A.; Levy, W.C.; Goyal, P.; Griffin, J.M.; Leedy, D.J.; Maurer, M.S. Lack of Association Between Neurohormonal Blockade and Survival in Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Am Heart Assoc 2021, 10, e022859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TTR GWAS. Available online: https://ttrgwas.wordpress.com/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Clark, C.; Rabl, M.; Dayon, L.; Popp, J. The promise of multi-omics approaches to discover biological alterations with clinical relevance in Alzheimer's disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 1065904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Qiao, L.; Lin, L. Integrative proteomic and metabolomic elucidation of cardiomyopathy with in vivo and in vitro models and clinical samples. Mol Ther 2024, 32, 3288–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).